University Of Columbia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a

Discussions regarding the founding of a college in the

Discussions regarding the founding of a college in the

After the Revolution, the college turned to the State of New York in order to restore its vitality, promising to make whatever changes to the school's charter the state might demand. The legislature agreed to assist the college, and on May 1, 1784, it passed "an Act for granting certain privileges to the College heretofore called King's College". The Act created a board of regents to oversee the resuscitation of King's College, and, in an effort to demonstrate its support for the new Republic, the legislature stipulated that "the College within the City of New York heretofore called King's College be forever hereafter called and known by the name of Columbia College", a reference to Columbia, an alternative name for America which in turn comes from the name of

After the Revolution, the college turned to the State of New York in order to restore its vitality, promising to make whatever changes to the school's charter the state might demand. The legislature agreed to assist the college, and on May 1, 1784, it passed "an Act for granting certain privileges to the College heretofore called King's College". The Act created a board of regents to oversee the resuscitation of King's College, and, in an effort to demonstrate its support for the new Republic, the legislature stipulated that "the College within the City of New York heretofore called King's College be forever hereafter called and known by the name of Columbia College", a reference to Columbia, an alternative name for America which in turn comes from the name of  On May 21, 1787,

On May 21, 1787,

In November 1813, the college agreed to incorporate its medical school with The College of Physicians and Surgeons, a new school created by the Regents of New York, forming Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. The college's enrollment, structure, and academics stagnated for the majority of the 19th century, with many of the college presidents doing little to change the way that the college functioned. In 1857, the college moved from the King's College campus at Park Place to a primarily

In November 1813, the college agreed to incorporate its medical school with The College of Physicians and Surgeons, a new school created by the Regents of New York, forming Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. The college's enrollment, structure, and academics stagnated for the majority of the 19th century, with many of the college presidents doing little to change the way that the college functioned. In 1857, the college moved from the King's College campus at Park Place to a primarily

The majority of Columbia's graduate and undergraduate studies are conducted in

The majority of Columbia's graduate and undergraduate studies are conducted in  The Nicholas Murray Butler Library, known simply as

The Nicholas Murray Butler Library, known simply as  A statue by sculptor

A statue by sculptor

In April 2007, the university purchased more than two-thirds of a site for a new campus in

In April 2007, the university purchased more than two-thirds of a site for a new campus in

According to the

According to the

Columbia University received 60,551 applications for the class of 2025 (entering 2021) and a total of around 2,218 were admitted to the two schools for an overall acceptance rate of 3.66%. Columbia is a racially diverse school, with approximately 52% of all students identifying themselves as persons of color. Additionally, 50% of all undergraduates received grants from Columbia. The average grant size awarded to these students is $46,516. In 2015–2016, annual undergraduate tuition at Columbia was $50,526 with a total cost of attendance of $65,860 (including room and board).

Annual gifts, fund-raising, and an increase in spending from the university's endowment have allowed Columbia to extend generous financial aid packages to qualifying students. On April 11, 2007, Columbia University announced a $400 million donation from media billionaire alumnus

Columbia University received 60,551 applications for the class of 2025 (entering 2021) and a total of around 2,218 were admitted to the two schools for an overall acceptance rate of 3.66%. Columbia is a racially diverse school, with approximately 52% of all students identifying themselves as persons of color. Additionally, 50% of all undergraduates received grants from Columbia. The average grant size awarded to these students is $46,516. In 2015–2016, annual undergraduate tuition at Columbia was $50,526 with a total cost of attendance of $65,860 (including room and board).

Annual gifts, fund-raising, and an increase in spending from the university's endowment have allowed Columbia to extend generous financial aid packages to qualifying students. On April 11, 2007, Columbia University announced a $400 million donation from media billionaire alumnus

The University Senate was established by the trustees after a university-wide referendum in 1969. It succeeded to the powers of the University Council, which was created in 1890 as a body of faculty, deans, and other administrators to regulate inter-Faculty affairs and consider issues of university-wide concern. The University Senate is a unicameral body consisting of 107 members drawn from all constituencies of the university. These include the president of the university, the provost, the deans of Columbia College and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, all of whom serve ''ex officio'', and five additional representatives, appointed by the president, from the university's administration. The president serves as the Senate's presiding officer. The Senate is charged with reviewing the educational policies, physical development, budget, and external relations of the university. It oversees the welfare and academic freedom of the faculty and the welfare of students.

The

The University Senate was established by the trustees after a university-wide referendum in 1969. It succeeded to the powers of the University Council, which was created in 1890 as a body of faculty, deans, and other administrators to regulate inter-Faculty affairs and consider issues of university-wide concern. The University Senate is a unicameral body consisting of 107 members drawn from all constituencies of the university. These include the president of the university, the provost, the deans of Columbia College and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, all of whom serve ''ex officio'', and five additional representatives, appointed by the president, from the university's administration. The president serves as the Senate's presiding officer. The Senate is charged with reviewing the educational policies, physical development, budget, and external relations of the university. It oversees the welfare and academic freedom of the faculty and the welfare of students.

The  Columbia has four official undergraduate colleges: Columbia College, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree; the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (also known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering), the engineering and applied science school offering the Bachelor of Science degree; the School of General Studies, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree to non-traditional students undertaking full- or part-time study; and

Columbia has four official undergraduate colleges: Columbia College, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree; the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (also known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering), the engineering and applied science school offering the Bachelor of Science degree; the School of General Studies, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree to non-traditional students undertaking full- or part-time study; and

Columbia is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity". Columbia was the first North American site where the

Columbia is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity". Columbia was the first North American site where the

Several prestigious awards are administered by Columbia University, most notably the

Several prestigious awards are administered by Columbia University, most notably the

The ''

The ''

Columbia is a top supplier of young engineering entrepreneurs for New York City. Over the past 20 years, graduates of Columbia established over 100 technology companies.

The Columbia University Organization of Rising Entrepreneurs (CORE) was founded in 1999. The student-run group aims to foster entrepreneurship on campus. Each year CORE hosts dozens of events, including talks, #StartupColumbia, a conference and venture competition for $250,000, and Ignite@CU, a weekend for undergrads interested in design, engineering, and entrepreneurship. Notable speakers include Peter Thiel, Jack Dorsey, Alexis Ohanian, Drew Houston, and Mark Cuban. As of 2006, CORE had awarded graduate and undergraduate students over $100,000 in seed capital.

CampusNetwork, an on-campus social networking site called Campus Network that preceded Facebook, was created and popularized by Columbia engineering student Adam Goldberg in 2003.

Columbia is a top supplier of young engineering entrepreneurs for New York City. Over the past 20 years, graduates of Columbia established over 100 technology companies.

The Columbia University Organization of Rising Entrepreneurs (CORE) was founded in 1999. The student-run group aims to foster entrepreneurship on campus. Each year CORE hosts dozens of events, including talks, #StartupColumbia, a conference and venture competition for $250,000, and Ignite@CU, a weekend for undergrads interested in design, engineering, and entrepreneurship. Notable speakers include Peter Thiel, Jack Dorsey, Alexis Ohanian, Drew Houston, and Mark Cuban. As of 2006, CORE had awarded graduate and undergraduate students over $100,000 in seed capital.

CampusNetwork, an on-campus social networking site called Campus Network that preceded Facebook, was created and popularized by Columbia engineering student Adam Goldberg in 2003.

A member institution of the

A member institution of the  Former students include

Former students include

Established in 2003 by university president

Established in 2003 by university president

The Columbia University Orchestra was founded by composer

The Columbia University Orchestra was founded by composer

In one of the school's longest-lasting traditions, begun in 1975, at midnight before the

In one of the school's longest-lasting traditions, begun in 1975, at midnight before the

File:Alexander Hamilton portrait by John Trumbull 1806.jpg,

File:Zbigniew Brzezinski, 1977.jpg, Zbigniew Brzezinski

File:Sonia Sotomayor in SCOTUS robe.jpg, Sonia Sotomayor

File:Kimberlé Crenshaw (40901215153).jpg, Kimberlé Crenshaw

File:Lee Bollinger - Daniella Zalcman less noise.jpg, Lee Bollinger

File:FranzBoas.jpg, Franz Boas

File:Margaret Mead (1901-1978).jpg, Margaret Mead

File:Edward Sapir.jpg, Edward Sapir

File:John Dewey cph.3a51565.jpg, John Dewey

File:Charles Beard.jpg, Charles A. Beard

File:Max Horkheimer.jpg, Max Horkheimer

File:Herbert Marcuse in Newton, Massachusetts 1955 (cropped).jpg, Herbert Marcuse

File:Edward Said and Daniel Barenboim in Sevilla, 2002 (Said).jpg, Edward Said

File:Gayatri Spivak on Subversive Festival.jpg, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

File:Orhan Pamuk 2009 Shankbone.jpg, Orhan Pamuk

File:Edwin H. Armstrong portrait by Florian Bachrach, with autographed dedication to Charles R. Underhill, August 18, 1950 - New England Wireless & Steam Museum - East Greenwich, RI - DSC06641 (cropped).jpg, Edwin Howard Armstrong

File:Enrico Fermi 1943-49.jpg,

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are the most important sites at which knowledge production occurs, along with "intergenerational kno ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

, Columbia is the oldest institution of higher education in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and the fifth-oldest institution of higher learning in the United States. It is one of nine colonial colleges

The colonial colleges are nine institutions of higher education chartered in the Thirteen Colonies before the United States of America became a sovereign nation after the American Revolution. These nine have long been considered together, notably ...

founded prior to the Declaration of Independence. It is a member of the Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight schools ...

. Columbia is ranked among the top universities in the world.

Columbia was established by royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

under George II of Great Britain

, house = Hanover

, religion = Protestant

, father = George I of Great Britain

, mother = Sophia Dorothea of Celle

, birth_date = 30 October / 9 November 1683

, birth_place = Herrenhausen Palace,Cannon. or Leine ...

. It was renamed Columbia College in 1784 following the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, and in 1787 was placed under a private board of trustees headed by former students Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

and John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

. In 1896, the campus was moved to its current location in Morningside Heights

Morningside Heights is a neighborhood on the West Side of Upper Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Morningside Drive to the east, 125th Street to the north, 110th Street to the south, and Riverside Drive to the west. Morningside ...

and renamed Columbia University.

Columbia scientists and scholars have played a pivotal role in scientific breakthroughs including brain-computer interface; the laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word "laser" is an acronym for "light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation". The fir ...

and maser

A maser (, an acronym for microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) is a device that produces coherent electromagnetic waves through amplification by stimulated emission. The first maser was built by Charles H. Townes, Ja ...

; nuclear magnetic resonance; the first nuclear pile

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

; the first nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

reaction in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

; the first evidence for plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

and continental drift; and much of the initial research and planning for the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Columbia is organized into twenty schools, including four undergraduate schools and 16 graduate schools. The university's research efforts include the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory

The Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) is the scientific research center of the Columbia Climate School, and a unit of The Earth Institute at Columbia University. It focuses on climate and earth sciences and is located on a 189-acre (64 h ...

, the Goddard Institute for Space Studies

The Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) is a laboratory in the Earth Sciences Division of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center affiliated with the Columbia University Earth Institute.

The institute is located at Columbia University in Ne ...

, and accelerator laboratories with Big Tech

Big Tech, also known as the Tech Giants, refers to the most dominant companies in the information technology industry, mostly located in the United States. The term also refers to the four or five largest American tech companies, called the Big ...

firms such as Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technology c ...

and IBM. Columbia is a founding member of the Association of American Universities and was the first school in the United States to grant the MD degree

MD, Md, mD or md may refer to:

Places

* Moldova (ISO country code MD)

* Maryland (US postal abbreviation MD)

* Magdeburg (vehicle plate prefix MD), a city in Germany

* Mödling District (vehicle plate prefix MD), in Lower Austria, Austria

People ...

. The university also annually administers the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

. With over 15 million volumes, Columbia University Library

Columbia University Libraries is the library system of Columbia University and one of the largest academic library systems in North America. With 15.0 million volumes and over 160,000 journals and serials, as well as extensive electronic resources ...

is the third-largest private research library in the United States.

The university's endowment stands at $13.3 billion in 2022, among the largest of any academic institution. , its alumni, faculty, and staff have included: seven Founding Fathers of the United States; four U.S. presidents; 33 foreign heads of state; two secretaries-general of the United Nations; ten justices of the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

, one of whom currently serves; 101 Nobel laureates; 125 National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

members; 53 living billionaires; 22 Olympic medalists; 33 Academy Award winners; and 125 Pulitzer Prize recipients.

History

Colonial period

Province of New York

The Province of New York (1664–1776) was a British proprietary colony and later royal colony on the northeast coast of North America. As one of the Middle Colonies, New York achieved independence and worked with the others to found the Uni ...

began as early as 1704, at which time Colonel Lewis Morris wrote to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, the missionary arm of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, persuading the society that New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

was an ideal community in which to establish a college. However, it was not until the founding of the College of New Jersey (renamed Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nine ...

) across the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

that the City of New York seriously considered founding a college. In 1746, an act was passed by the general assembly of New York to raise funds for the foundation of a new college. In 1751, the assembly appointed a commission of ten New York residents, seven of whom were members of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, to direct the funds accrued by the state lottery

In the United States, lotteries are run by 48 jurisdictions: 45 states plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Lotteries are subject to the laws of and operated independently by each jurisdiction, and there is no ...

towards the foundation of a college.

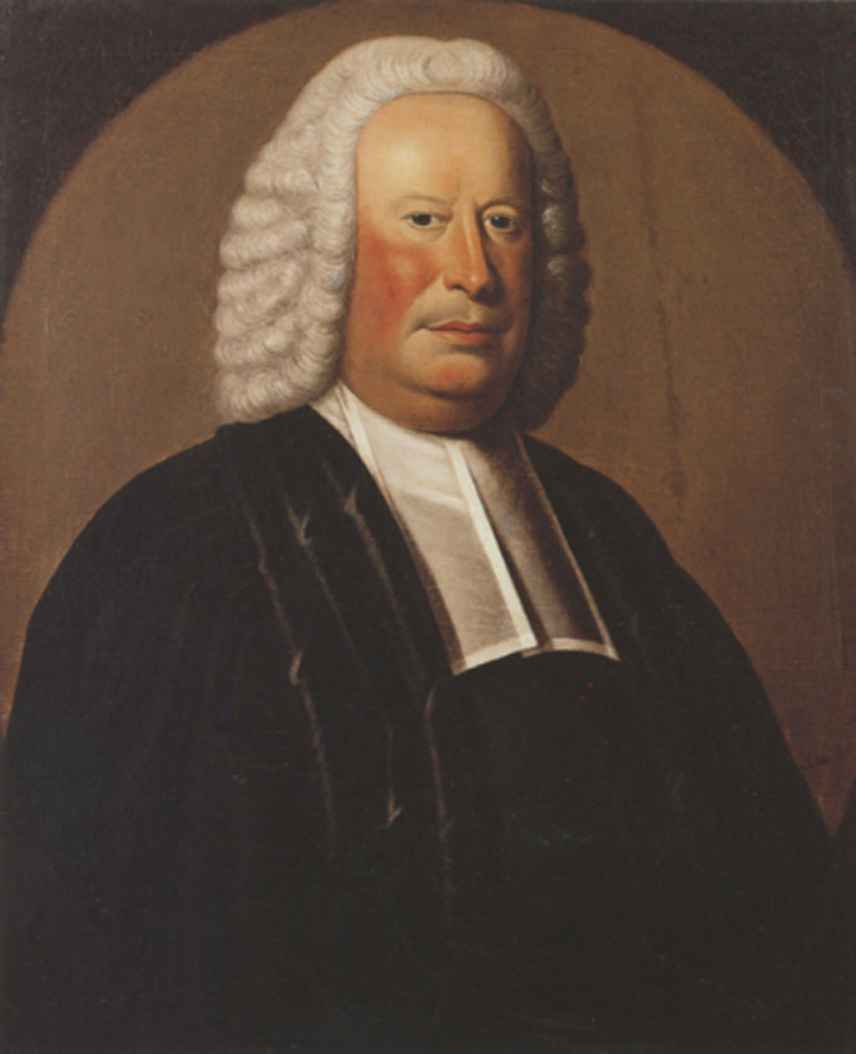

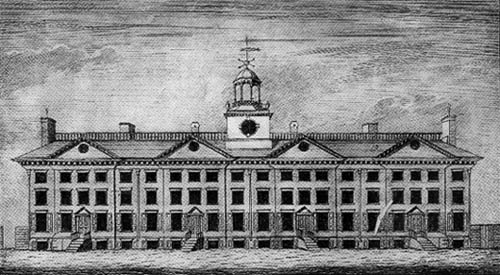

Classes were initially held in July 1754 and were presided over by the college's first president, Dr. Samuel Johnson. Dr. Johnson was the only instructor of the college's first class, which consisted of a mere eight students. Instruction was held in a new schoolhouse adjoining Trinity Church, located on what is now lower Broadway in Manhattan. The college was officially founded on October 31, 1754, as King's College by royal charter of George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089)

* ...

, making it the oldest institution of higher learning in the State of New York and the fifth oldest in the United States.

In 1763, Dr. Johnson was succeeded in the presidency by Myles Cooper

Myles Cooper (1735 – May 1, 1785) was a figure in colonial New York. An Anglican priest, he served as the President of King's College (predecessor of today's Columbia University) from 1763 to 1775, and was a public opponent of the American Revo ...

, a graduate of The Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault. It is distinguished by its pred ...

, and an ardent Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

. In the charged political climate of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, his chief opponent in discussions at the college was an undergraduate of the class of 1777, Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

. The Irish anatomist, Samuel Clossy

Samuel Clossy MB MD (''c.'' 1724 – 22 August 1786) was a pioneering Irish anatomist and the first college professor of a medical subject in North America.

Early life and education

Samuel Clossy was born around 1724 in Dublin, Ireland. His pa ...

, was appointed professor of natural philosophy in October 1765 and later the college's first professor of anatomy in 1767. The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

broke out in 1776, and was catastrophic for the operation of King's College, which suspended instruction for eight years beginning in 1776 with the arrival of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

. The suspension continued through the military occupation of New York City by British troops until their departure in 1783. The college's library was looted and its sole building requisitioned for use as a military hospital first by American and then British forces.

18th century

After the Revolution, the college turned to the State of New York in order to restore its vitality, promising to make whatever changes to the school's charter the state might demand. The legislature agreed to assist the college, and on May 1, 1784, it passed "an Act for granting certain privileges to the College heretofore called King's College". The Act created a board of regents to oversee the resuscitation of King's College, and, in an effort to demonstrate its support for the new Republic, the legislature stipulated that "the College within the City of New York heretofore called King's College be forever hereafter called and known by the name of Columbia College", a reference to Columbia, an alternative name for America which in turn comes from the name of

After the Revolution, the college turned to the State of New York in order to restore its vitality, promising to make whatever changes to the school's charter the state might demand. The legislature agreed to assist the college, and on May 1, 1784, it passed "an Act for granting certain privileges to the College heretofore called King's College". The Act created a board of regents to oversee the resuscitation of King's College, and, in an effort to demonstrate its support for the new Republic, the legislature stipulated that "the College within the City of New York heretofore called King's College be forever hereafter called and known by the name of Columbia College", a reference to Columbia, an alternative name for America which in turn comes from the name of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

. The Regents finally became aware of the college's defective constitution in February 1787 and appointed a revision committee, which was headed by John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

and Alexander Hamilton. In April of that same year, a new charter was adopted for the college granted the power to a separate board of 24 trustees.Moore, Nathanal Fischer (1846). ''A Historical Sketch of Columbia''. New York, New York: Columbia University Press.

On May 21, 1787,

On May 21, 1787, William Samuel Johnson

William Samuel Johnson (October 7, 1727 – November 14, 1819) was an American Founding Father and statesman. Before the Revolutionary War, he served as a militia lieutenant before being relieved following his rejection of his election to the Fir ...

, the son of Dr. Samuel Johnson, was unanimously elected president of Columbia College. Prior to serving at the university, Johnson had participated in the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Navy ...

and been chosen as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. For a period in the 1790s, with New York City as the federal and state capital and the country under successive Federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

governments, a revived Columbia thrived under the auspices of Federalists such as Hamilton and Jay. Both President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

and Vice President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

attended the college's commencement on May 6, 1789, as a tribute of honor to the many alumni of the school who had been involved in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

.

19th century to present

In November 1813, the college agreed to incorporate its medical school with The College of Physicians and Surgeons, a new school created by the Regents of New York, forming Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. The college's enrollment, structure, and academics stagnated for the majority of the 19th century, with many of the college presidents doing little to change the way that the college functioned. In 1857, the college moved from the King's College campus at Park Place to a primarily

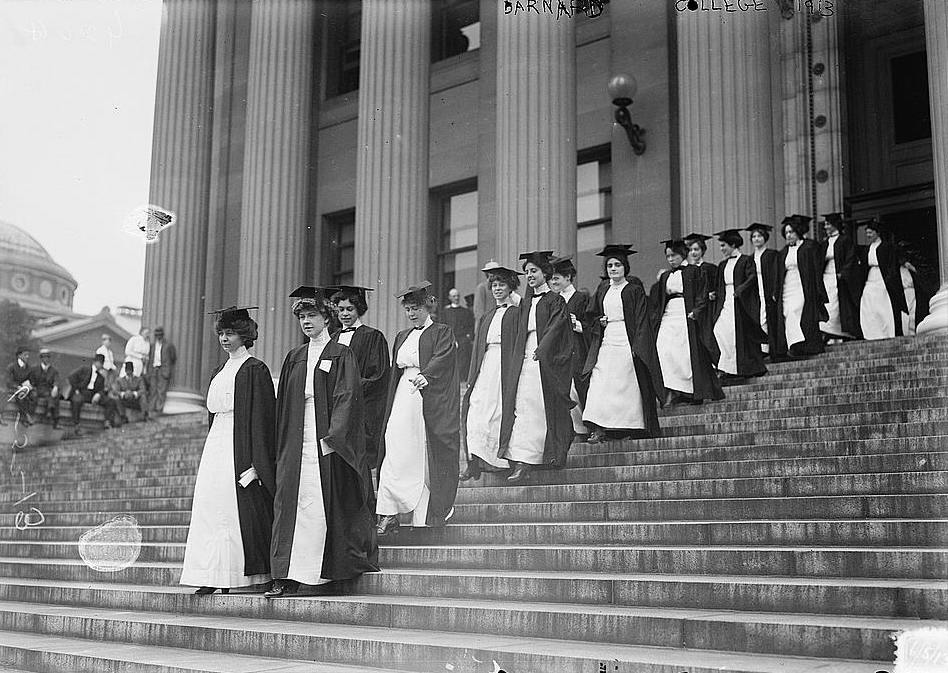

In November 1813, the college agreed to incorporate its medical school with The College of Physicians and Surgeons, a new school created by the Regents of New York, forming Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. The college's enrollment, structure, and academics stagnated for the majority of the 19th century, with many of the college presidents doing little to change the way that the college functioned. In 1857, the college moved from the King's College campus at Park Place to a primarily Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (also referred to as Victorian Gothic, neo-Gothic, or Gothick) is an architectural movement that began in the late 1740s in England. The movement gained momentum and expanded in the first half of the 19th century, as increasingly ...

campus on 49th Street and Madison Avenue

Madison Avenue is a north-south avenue in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, United States, that carries northbound one-way traffic. It runs from Madison Square (at 23rd Street) to meet the southbound Harlem River Drive at 142nd Stre ...

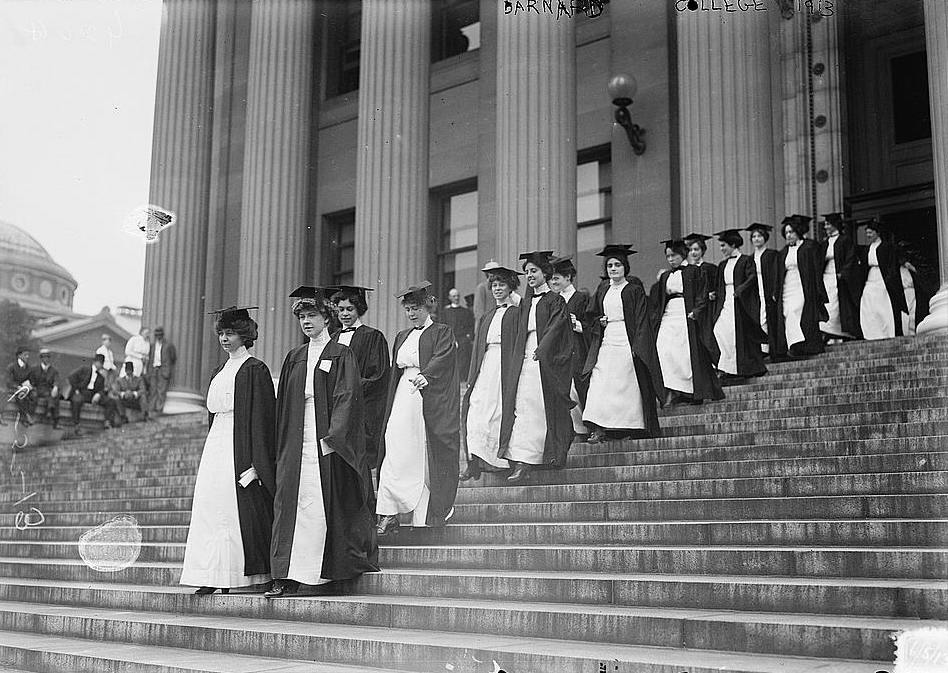

, where it remained for the next forty years. During the last half of the 19th century, under the leadership of President F.A.P. Barnard, the president that Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

is named after, the institution rapidly assumed the shape of a modern university. Barnard College was created in 1889 as a response to the university's refusal to accept women. By this time, the college's investments in New York real estate became a primary source of steady income for the school, mainly owing to the city's expanding population. In 1896, university president Seth Low

Seth Low (January 18, 1850 – September 17, 1916) was an American educator and political figure who served as the mayor of Brooklyn from 1881 to 1885, the president of Columbia University from 1890 to 1901, a diplomatic representative of t ...

moved the campus from 49th Street to its present location, a more spacious campus in the developing neighborhood of Morningside Heights

Morningside Heights is a neighborhood on the West Side of Upper Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Morningside Drive to the east, 125th Street to the north, 110th Street to the south, and Riverside Drive to the west. Morningside ...

. Under the leadership of Low's successor, Nicholas Murray Butler, who served for over four decades, Columbia rapidly became the nation's major institution for research, setting the "multiversity" model that later universities would adopt. Prior to becoming the president of Columbia University, Butler founded Teachers College, as a school to prepare home economists and manual art teachers for the children of the poor, with philanthropist Grace Hoadley Dodge. Teachers College is currently affiliated as the university's Graduate School of Education.

Research into the atom by faculty members John R. Dunning

John Ray Dunning (September 24, 1907 – August 25, 1975) was an American physicist who played key roles in the Manhattan Project that developed the first atomic bombs. He specialized in neutron physics, and did pioneering work in gaseous diffusio ...

, I. I. Rabi

Isidor Isaac Rabi (; born Israel Isaac Rabi, July 29, 1898 – January 11, 1988) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944 for his discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance, which is used in magnetic resonance ima ...

, Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

and Polykarp Kusch

Polykarp Kusch (January 26, 1911 – March 20, 1993) was a German-born American physicist. In 1955, the Nobel Committee gave a divided Nobel Prize for Physics, with one half going to Kusch for his accurate determination that the magnetic momen ...

placed Columbia's physics department in the international spotlight in the 1940s after the first nuclear pile was built to start what became the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. In 1928, Seth Low

Seth Low (January 18, 1850 – September 17, 1916) was an American educator and political figure who served as the mayor of Brooklyn from 1881 to 1885, the president of Columbia University from 1890 to 1901, a diplomatic representative of t ...

Junior College was established by Columbia University in order to mitigate the number of Jewish applicants to Columbia College. The college was closed in 1936 due to the adverse effects of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and its students were subsequently taught at Morningside Heights, although they did not belong to any college but to the university at large.

There was an evening school called University Extension, which taught night classes, for a fee, to anyone willing to attend. In 1947, the program was reorganized as an undergraduate college and designated the School of General Studies in response to the return of GIs

A geographic information system (GIS) is a type of database containing Geographic data and information, geographic data (that is, descriptions of phenomena for which location is relevant), combined with Geographic information system software, sof ...

after World War II. In 1995, the School of General Studies was again reorganized as a full-fledged liberal arts college for non-traditional students (those who have had an academic break of one year or more, or are pursuing dual-degrees) and was fully integrated into Columbia's traditional undergraduate curriculum. Within the same year, the Division of Special Programs—later the School of Continuing Education, and now the School of Professional Studies—was established to reprise the former role of University Extension. While the School of Professional Studies only offered non-degree programs for lifelong learners and high school students in its earliest stages, it now offers degree programs in a diverse range of professional and inter-disciplinary fields.

In the aftermath of World War II, the discipline of international relations became a major scholarly focus of the university, and in response, the School of International and Public Affairs was founded in 1946, drawing upon the resources of the faculties of political science, economics, and history. The Columbia University Bicentennial was celebrated in 1954.

During the 1960s Columbia experienced large-scale student activism, which reached a climax in the spring of 1968 when hundreds of students occupied buildings on campus. The incident forced the resignation of Columbia's president, Grayson Kirk

Grayson Louis Kirk (October 12, 1903 – November 21, 1997) was an American political scientist who served as president of Columbia University during the Columbia University protests of 1968. He was also an advisor to the State Department an ...

, and the establishment of the University Senate.

Though several schools within the university had admitted women for years, Columbia College first admitted women in the fall of 1983, after a decade of failed negotiations with Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

, the all-female institution affiliated with the university, to merge the two schools. Barnard College still remains affiliated with Columbia, and all Barnard graduates are issued diplomas signed by the presidents of Columbia University

The president of Columbia University is the chief officer of Columbia University in New York City. The position was first created in 1754 by the original royal charter for the university, issued by George II of Great Britain, George II, and the p ...

and Barnard College.

During the late 20th century, the university underwent significant academic, structural, and administrative changes as it developed into a major research university. For much of the 19th century, the university consisted of decentralized and separate faculties specializing in Political Science, Philosophy, and Pure Science. In 1979, these faculties were merged into the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. In 1991, the faculties of Columbia College, the School of General Studies, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the School of the Arts, and the School of Professional Studies were merged into the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, leading to the academic integration and centralized governance of these schools. In 2010, the School of International and Public Affairs, which was previously a part of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, became an independent faculty.

Campus

Morningside Heights

The majority of Columbia's graduate and undergraduate studies are conducted in

The majority of Columbia's graduate and undergraduate studies are conducted in Morningside Heights

Morningside Heights is a neighborhood on the West Side of Upper Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Morningside Drive to the east, 125th Street to the north, 110th Street to the south, and Riverside Drive to the west. Morningside ...

on Seth Low

Seth Low (January 18, 1850 – September 17, 1916) was an American educator and political figure who served as the mayor of Brooklyn from 1881 to 1885, the president of Columbia University from 1890 to 1901, a diplomatic representative of t ...

's late-19th century vision of a university campus where all disciplines could be taught at one location. The campus was designed along Beaux-Arts planning principles by the architects McKim, Mead & White

McKim, Mead & White was an American architectural firm that came to define architectural practice, urbanism, and the ideals of the American Renaissance in fin de siècle New York. The firm's founding partners Charles Follen McKim (1847–1909), Wil ...

. Columbia's main campus occupies more than six city block

A city block, residential block, urban block, or simply block is a central element of urban planning and urban design.

A city block is the smallest group of buildings that is surrounded by streets, not counting any type of thoroughfare within t ...

s, or , in Morningside Heights

Morningside Heights is a neighborhood on the West Side of Upper Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Morningside Drive to the east, 125th Street to the north, 110th Street to the south, and Riverside Drive to the west. Morningside ...

, New York City, a neighborhood that contains a number of academic institutions. The university owns over 7,800 apartments in Morningside Heights, housing faculty, graduate students, and staff. Almost two dozen undergraduate dormitories (purpose-built or converted) are located on campus or in Morningside Heights. Columbia University has an extensive tunnel system, more than a century old, with the oldest portions predating the present campus. Some of these remain accessible to the public, while others have been cordoned off.

The Nicholas Murray Butler Library, known simply as

The Nicholas Murray Butler Library, known simply as Butler Library

Butler Library is located on the Morningside Heights campus of Columbia University at 535 West 114th Street, in Manhattan, New York City. It is the university's largest single library with over 2 million volumes, as well as one of the largest bui ...

, is the largest single library in the Columbia University Library System

Columbia University Libraries is the library system of Columbia University and one of the largest academic library systems in North America. With 15.0 million volumes and over 160,000 journals and serials, as well as extensive electronic resources ...

, and is one of the largest buildings on the campus. Proposed as "South Hall" by the university's former president Nicholas Murray Butler as expansion plans for Low Memorial Library

The Low Memorial Library (nicknamed Low) is a building at the center of Columbia University's Morningside Heights campus in Manhattan, New York City, United States. The building, located near 116th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam Aven ...

stalled, the new library was funded by Edward Harkness, benefactor of Yale's residential college system, and designed by his favorite architect, James Gamble Rogers

James Gamble Rogers (March 3, 1867 – October 1, 1947) was an American architect. A proponent of what came to be known as Collegiate Gothic architecture, he is best known for his academic commissions at Yale University, Columbia Univer ...

. It was completed in 1934 and renamed for Butler in 1946. The library design is neo-classical in style. Its facade features a row of columns in the Ionic order

The Ionic order is one of the three canonic orders of classical architecture, the other two being the Doric and the Corinthian. There are two lesser orders: the Tuscan (a plainer Doric), and the rich variant of Corinthian called the composite or ...

above which are inscribed the names of great writers, philosophers, and thinkers, most of whom are read by students engaged in the Core Curriculum of Columbia College. , Columbia's library system includes over 15.0 million volumes, making it the eighth largest library system and fifth largest collegiate library system in the United States.

Several buildings on the Morningside Heights campus are listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

. Low Memorial Library

The Low Memorial Library (nicknamed Low) is a building at the center of Columbia University's Morningside Heights campus in Manhattan, New York City, United States. The building, located near 116th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam Aven ...

, a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

and the centerpiece of the campus, is listed for its architectural significance. Philosophy Hall

Philosophy Hall is a building on the campus of Columbia University in New York City. It houses the English, Philosophy, and French departments, along with the university's writing center, part of its registrar's office, and the student lounge of it ...

is listed as the site of the invention of FM radio

FM broadcasting is a method of radio broadcasting using frequency modulation (FM). Invented in 1933 by American engineer Edwin Armstrong, wide-band FM is used worldwide to provide high fidelity sound over broadcast radio. FM broadcasting is cap ...

. Also listed is Pupin Hall

Pupin Physics Laboratories , also known as Pupin Hall, is home to the Columbia University Physics Department, physics and astronomy departments of Columbia University in New York City. The building is located on the south side of 120th Street (Man ...

, another National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

, which houses the physics and astronomy departments. Here the first experiments on the fission of uranium were conducted by Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

. The uranium atom was split there ten days after the world's first atom-splitting in Copenhagen, Denmark. Other buildings listed include Casa Italiana

Casa Italiana is a building at Columbia University located at 1161 Tenth Avenue (Manhattan), Amsterdam Avenue between 116th Street (Manhattan), West 116th and 118th Street (Manhattan), 118th Streets in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manha ...

, the Delta Psi, Alpha Chapter building

The Delta Psi, Alpha Chapter fraternity house is located at 434 Riverside Drive in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. It was purpose built in 1898 and continues to serve the Columbia Chapter of the Fraternity of De ...

of St. Anthony Hall

St. Anthony Hall or the Fraternity of Delta Psi is an American fraternity and literary society. Its first chapter was founded at Columbia University on , the Calendar of saints, feast day of Anthony the Great, Saint Anthony the Great. The frater ...

, Earl Hall

Earl Hall is a building on the campus of Columbia University. Built in 1900–1902 and designed by McKim, Mead & White, the building serves as a center for student religious life. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The ...

, and the buildings of the affiliated Union Theological Seminary.

A statue by sculptor

A statue by sculptor Daniel Chester French

Daniel Chester French (April 20, 1850 – October 7, 1931) was an American sculptor of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, best known for his 1874 sculpture ''The Minute Man'' in Concord, Massachusetts, and his 1920 monume ...

called '' Alma Mater'' is centered on the front steps of Low Memorial Library

The Low Memorial Library (nicknamed Low) is a building at the center of Columbia University's Morningside Heights campus in Manhattan, New York City, United States. The building, located near 116th Street between Broadway and Amsterdam Aven ...

. McKim, Mead & White invited French to build the sculpture in order to harmonize with the larger composition of the court and library in the center of the campus. Draped in an academic gown, the female figure of Alma Mater wears a crown of laurels and sits on a throne. The scroll-like arms of the throne end in lamps, representing sapientia and doctrina. A book signifying knowledge, balances on her lap, and an owl, the attribute of wisdom, is hidden in the folds of her gown. Her right hand holds a scepter composed of four sprays of wheat, terminating with a crown of King's College which refers to Columbia's origin as a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

institution in 1754. A local actress named Mary Lawton was said to have posed for parts of the sculpture. The statue was dedicated on September 23, 1903, as a gift of Mr. & Mrs. Robert Goelet, and was originally covered in golden leaf. During the Columbia University protests of 1968 a bomb damaged the sculpture, but it has since been repaired. The small hidden owl on the sculpture is also the subject of many Columbia legends, the main legend being that the first student in the freshmen class to find the hidden owl on the statue will be valedictorian, and that any subsequent Columbia male who finds it will marry a Barnard student, given that Barnard is a women's college.

"The Steps", alternatively known as "Low Steps" or the "Urban Beach", are a popular meeting area for Columbia students. The term refers to the long series of granite steps leading from the lower part of campus (South Field) to its upper terrace. With a design inspired by the City Beautiful movement, the steps of Low Library provides Columbia University and Barnard College students, faculty, and staff with a comfortable outdoor platform and space for informal gatherings, events, and ceremonies. McKim's classical facade epitomizes late 19th-century new-classical designs, with its columns and portico marking the entrance to an important structure.

Other campuses

In April 2007, the university purchased more than two-thirds of a site for a new campus in

In April 2007, the university purchased more than two-thirds of a site for a new campus in Manhattanville

Manhattanville (also known as West Harlem or West Central Harlem) is a neighborhood in the New York City borough of Manhattan bordered on the north by 135th Street; on the south by 122nd and 125th Streets; on the west by Hudson River; and on t ...

, an industrial neighborhood to the north of the Morningside Heights campus. Stretching from 125th Street to 133rd Street

133rd Street is a street in Manhattan and the Bronx, New York City. In Harlem, Manhattan, it begins at Riverside Drive on its western side and crosses Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue, and ends at Convent Avenue, before resuming on the eastern side ...

, Columbia Manhattanville houses buildings for Columbia's Business School, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia School of the Arts, and the Jerome L. Greene Center for Mind, Brain, and Behavior, where research will occur on neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. The $7 billion expansion plan included demolishing all buildings, except three that are historically significant (the Studebaker Building, Prentis Hall

Prentis Hall is a historic building located on the Manhattanville campus of Columbia University at 632 West 125th Street. It houses the university's department of music and the Computer Music Center, as well as facilities for the School of the ...

, and the Nash Building), eliminating the existing light industry and storage warehouses, and relocating tenants in 132 apartments. Replacing these buildings created of space for the university. Community activist groups in West Harlem fought the expansion for reasons ranging from property protection and fair exchange for land, to residents' rights. Subsequent public hearings drew neighborhood opposition. , the State of New York's Empire State Development Corporation approved use of eminent domain, which, through declaration of Manhattanville's "blighted" status, gives governmental bodies the right to appropriate private property for public use. On May 20, 2009, the New York State Public Authorities Control Board

The New York State Public Authorities Control Board is composed of five members, appointed by the Governor, some upon the recommendation of members of the Legislature. The five members of PACB are appointed by the Governor to serve one-year terms, ...

approved the Manhanttanville expansion plan.

NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital is affiliated with the medical schools of both Columbia University and Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

. According to ''U.S. News & World Report''s "2020–21 Best Hospitals Honor Roll and Medical Specialties Rankings", it is ranked fourth overall and second among university hospitals. Columbia's medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

has a strategic partnership with New York State Psychiatric Institute, and is affiliated with 19 other hospitals in the U.S. and four hospitals overseas. Health-related schools are located at the Columbia University Medical Center

NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center (NYP/CUIMC), also known as the Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC), is an academic medical center and the largest campus of NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. It includes C ...

, a campus located in the neighborhood of Washington Heights, fifty blocks uptown. Other teaching hospitals affiliated with Columbia through the NewYork-Presbyterian network include the Payne Whitney Clinic in Manhattan, and the Payne Whitney Westchester, a psychiatric institute located in White Plains, New York. On the northern tip of Manhattan island (in the neighborhood of Inwood), Columbia owns the Baker Field, which includes the Lawrence A. Wien Stadium

Robert K. Kraft Field at Lawrence A. Wien Stadium, officially known as Robert K. Kraft Field at Lawrence A. Wien Stadium at Baker Athletics Complex, is a stadium in the Inwood neighborhood at the northern tip of the island of Manhattan, New Y ...

as well as facilities for field sports, outdoor track, and tennis. There is a third campus on the west bank of the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

, the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory

The Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) is the scientific research center of the Columbia Climate School, and a unit of The Earth Institute at Columbia University. It focuses on climate and earth sciences and is located on a 189-acre (64 h ...

and Earth Institute in Palisades, New York. A fourth is the Nevis Laboratories in Irvington, New York for the study of particle and motion physics. A satellite site in Paris, France holds classes at Reid Hall

Reid Hall is a complex of academic facilities owned and operated by Columbia University that is located in the Montparnasse quartier of Paris, France. It houses the Columbia University Institute for Scholars at Reid Hall in addition to various ...

.

Sustainability

In 2006, the university established the Office of Environmental Stewardship to initiate, coordinate and implement programs to reduce the university's environmental footprint. The U.S. Green Building Council selected the university's Manhattanville plan for theLeadership in Energy and Environmental Design

Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) is a

green building certification program used worldwide. Developed by the non-profit U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC), it includes a set of rating systems for the design, construction ...

(LEED) Neighborhood Design pilot program. The plan commits to incorporating smart growth, new urbanism and "green" building design principles. Columbia is one of the 2030 Challenge Partners, a group of nine universities in the city of New York that have pledged to reduce their greenhouse emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities strengthen the greenhouse effect, contributing to climate change. Most is carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels: coal, oil, and natural gas. The largest emitters include coal in China and la ...

by 30% within the next ten years. Columbia University adopts LEED standards for all new construction and major renovations. The university requires a minimum of Silver, but through its design and review process seeks to achieve higher levels. This is especially challenging for lab and research buildings with their intensive energy use; however, the university also uses lab design guidelines that seek to maximize energy efficiency while protecting the safety of researchers.

Every Thursday and Sunday of the month, Columbia hosts a greenmarket

A farmers' market (or farmers market according to the AP stylebook, also farmer's market in the Cambridge Dictionary) is a physical retail marketplace intended to sell foods directly by farmers to consumers. Farmers' markets may be indoors or o ...

where local farmers can sell their produce to residents of the city. In addition, from April to November Hodgson's farm, a local New York gardening center, joins the market bringing a large selection of plants and blooming flowers. The market is one of the many operated at different points throughout the city by the non-profit group GrowNYC. Dining services at Columbia spends 36 percent of its food budget on local products, in addition to serving sustainably harvested seafood and fair trade coffee on campus. Columbia has been rated "B+" by the 2011 College Sustainability Report Card for its environmental and sustainability initiatives.A. W. Kuchler August William Kuchler (born ''August Wilhelm Küchler''; 1907–1999) was a German-born American geographer and naturalist who is noted for developing a plant association system in widespread use in the United States. Some of this database has beco ...

U.S. potential natural vegetation

In ecology, potential natural vegetation (PNV), also known as Kuchler potential vegetation, is the vegetation that would be expected given environmental constraints (climate, geomorphology, geology) without human intervention or a hazard event ...

types, Columbia University would have a dominant vegetation type of Appalachian Oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

(''104'') with a dominant vegetation form of Eastern Hardwood

Hardwood is wood from dicot trees. These are usually found in broad-leaved temperate and tropical forests. In temperate and boreal latitudes they are mostly deciduous, but in tropics and subtropics mostly evergreen. Hardwood (which comes from ...

Forest (''25'').

Transportation

Columbia Transportation

Columbia Transportation is a fare-free bus network providing service to Columbia University campuses. It is operated by Academy Bus Lines and Luxury Transportation to serve employees and students. The buses are open to all Columbia faculty, stud ...

is the bus service of the university, operated by Academy Bus Lines

Academy Bus Lines is a bus company in New Jersey providing local bus services in northern New Jersey, line-run services to/from New York City from points in southern and central New Jersey, and contract and charter service in the eastern United ...

. The buses are open to all Columbia faculty, students, Dodge Fitness Center members, and anyone else who holds a Columbia ID card. In addition, all TSC TSC may refer to:

Organizations

* Technology Service Corporation, a US engineering company

* Terrorist Screening Center, a division of the National Security Branch of the US Federal Bureau of Investigation

* The Shopping Channel, a Canadian televi ...

students can ride the buses.

Academics

Undergraduate admissions and financial aid

John Kluge

John Werner Kluge (; September 21, 1914September 7, 2010) was a German-American entrepreneur who became a television industry mogul in the United States. At one time he was the richest person in the U.S.

Early life and education

Kluge was bo ...

to be used exclusively for undergraduate financial aid. The donation is among the largest single gifts to higher education. , undergraduates from families with incomes as high as $60,000 a year will have the projected cost of attending the university, including room, board, and academic fees, fully paid for by the university. That same year, the university ended loans for incoming and then-current students who were on financial aid, replacing loans that were traditionally part of aid packages with grants from the university. However, this does not apply to international students, transfer students, visiting students, or students in the School of General Studies. In the fall of 2010, admission to Columbia's undergraduate colleges Columbia College and the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (also known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering) began accepting the Common Application

The Common Application (more commonly known as the Common App) is an undergraduate college admission application that applicants may use to apply to over 1,000 member colleges and universities in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, as we ...

. The policy change made Columbia one of the last major academic institutions and the last Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight schools ...

university to switch to the Common Application.

Scholarships are also given to undergraduate students by the admissions committee. Designations include John W. Kluge Scholars, John Jay Scholars, C. Prescott Davis Scholars, Global Scholars, Egleston Scholars, and Science Research Fellows. Named scholars are selected by the admission committee from first-year applicants. According to Columbia, the first four designated scholars "distinguish themselves for their remarkable academic and personal achievements, dynamism, intellectual curiosity, the originality and independence of their thinking, and the diversity that stems from their different cultures and their varied educational experiences".

In 1919, Columbia established a student application process characterized by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' as "the first modern college application". The application required a photograph of the applicant, the maiden name of the applicant's mother, and the applicant's religious background.

Organization

Columbia University is an independent, privately supported, nonsectarian institution of higher education. Its official corporate name is " The Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York". The university's first charter was granted in 1754 by King George II; however, its modern charter was first enacted in 1787 and last amended in 1810 by the New York State Legislature. The university is governed by 24 trustees, customarily including the president, who serves ''ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by right ...

''. The trustees themselves are responsible for choosing their successors. Six of the 24 are nominated from a pool of candidates recommended by the Columbia Alumni Association. Another six are nominated by the board in consultation with the executive committee of the University Senate. The remaining 12, including the president, are nominated by the trustees themselves through their internal processes. The term of office for trustees is six years. Generally, they serve for no more than two consecutive terms. The trustees appoint the president and other senior administrative officers of the university, and review and confirm faculty appointments as required. They determine the university's financial and investment policies, authorize the budget, supervise the endowment, direct the management of the university's real estate and other assets, and otherwise oversee the administration and management of the university.

The University Senate was established by the trustees after a university-wide referendum in 1969. It succeeded to the powers of the University Council, which was created in 1890 as a body of faculty, deans, and other administrators to regulate inter-Faculty affairs and consider issues of university-wide concern. The University Senate is a unicameral body consisting of 107 members drawn from all constituencies of the university. These include the president of the university, the provost, the deans of Columbia College and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, all of whom serve ''ex officio'', and five additional representatives, appointed by the president, from the university's administration. The president serves as the Senate's presiding officer. The Senate is charged with reviewing the educational policies, physical development, budget, and external relations of the university. It oversees the welfare and academic freedom of the faculty and the welfare of students.

The

The University Senate was established by the trustees after a university-wide referendum in 1969. It succeeded to the powers of the University Council, which was created in 1890 as a body of faculty, deans, and other administrators to regulate inter-Faculty affairs and consider issues of university-wide concern. The University Senate is a unicameral body consisting of 107 members drawn from all constituencies of the university. These include the president of the university, the provost, the deans of Columbia College and the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, all of whom serve ''ex officio'', and five additional representatives, appointed by the president, from the university's administration. The president serves as the Senate's presiding officer. The Senate is charged with reviewing the educational policies, physical development, budget, and external relations of the university. It oversees the welfare and academic freedom of the faculty and the welfare of students.

The president of Columbia University

The president of Columbia University is the chief officer of Columbia University in New York City. The position was first created in 1754 by the original royal charter for the university, issued by George II, and the power to appoint the presiden ...

, who is selected by the trustees in consultation with the executive committee of the University Senate and who serves at the trustees' pleasure, is the chief executive officer of the university. Assisting the president in administering the university are the provost, the senior executive vice president, the executive vice president for health and biomedical sciences, several other vice presidents, the general counsel, the secretary of the university, and the deans of the faculties, all of whom are appointed by the trustees on the nomination of the president and serve at their pleasure. Lee C. Bollinger

Lee Carroll Bollinger (born April 30, 1946) is an American lawyer and educator who is serving as the 19th and current president of Columbia University, where he is also the Seth Low Professor of the University and a faculty member of Columbia Law ...

became the 19th president of Columbia University on June 1, 2002. As president of the University of Michigan

The president of the University of Michigan is a constitutional officer who serves as the principal executive officer of the University of Michigan. The president is chosen by the Board of Regents of the University of Michigan, as provided for ...

, he played a leading role in the twin Supreme Court cases Grutter v. Bollinger

''Grutter v. Bollinger'', 539 U.S. 306 (2003), was a landmark case of the Supreme Court of the United States concerning affirmative action in student admissions. The Court held that a student admissions process that favors "underrepresented minor ...

and Gratz v. Bollinger

''Gratz v. Bollinger'', 539 U.S. 244 (2003), was a United States Supreme Court of the United States, Supreme Court List of United States Supreme Court cases, case regarding the University of Michigan undergraduate affirmative action University and ...

, which upheld the use of student diversity as a compelling justification for affirmative action in higher education.

Columbia has four official undergraduate colleges: Columbia College, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree; the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (also known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering), the engineering and applied science school offering the Bachelor of Science degree; the School of General Studies, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree to non-traditional students undertaking full- or part-time study; and

Columbia has four official undergraduate colleges: Columbia College, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree; the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science (also known as SEAS or Columbia Engineering), the engineering and applied science school offering the Bachelor of Science degree; the School of General Studies, the liberal arts college offering the Bachelor of Arts degree to non-traditional students undertaking full- or part-time study; and Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

. Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

is a women's liberal arts college and an academic affiliate in which students receive a Bachelor of Arts degree from Columbia University. Their degrees are signed by the presidents of Columbia University and Barnard College. Barnard students are also eligible to cross-register classes that are available through the Barnard Catalogue and alumnae can join the Columbia Alumni Association.

Joint degree programs are available through Union Theological Seminary, the Jewish Theological Seminary of America

The Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS) is a Conservative Jewish education organization in New York City, New York. It is one of the academic and spiritual centers of Conservative Judaism and a major center for academic scholarship in Jewish studie ...

, as well as through the Juilliard School

The Juilliard School ( ) is a private performing arts conservatory in New York City. Established in 1905, the school trains about 850 undergraduate and graduate students in dance, drama, and music. It is widely regarded as one of the most el ...

. Teachers College and Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

are official faculties of the university; both colleges' presidents are deans under the university governance structure. The Columbia University Senate includes faculty and student representatives from Teachers College and Barnard College who serve two-year terms; all senators are accorded full voting privileges regarding matters impacting the entire university. Teachers College is an affiliated, financially independent graduate school with their own Board of Trustees. Pursuant to an affiliation agreement, Columbia is given the authority to confer "degrees and diplomas" to the graduates of Teachers College. The degrees are signed by presidents of Teachers College and Columbia University in a manner analogous to the university's other graduate schools. Columbia's General Studies school also has joint undergraduate programs available through University College London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = ...

, Sciences Po

, motto_lang = fr

, mottoeng = Roots of the Future