Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian

Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

revolutionary,

political theorist

A political theorist is someone who engages in constructing or evaluating political theory, including political philosophy. Theorists may be academics or independent scholars. Here the most notable political theorists are categorized by their ...

and politician. Ideologically a Marxist, his developments to the ideology are called

Trotskyism

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

.

Born to a wealthy Jewish family in Yanovka (now

Bereslavka, Ukraine

Bereslavka ( uk, Береславка, formerly known as Yanovka or Yanivka) is a village in Kropyvnytskyi Raion, Kirovohrad Oblast, Ukraine. The village has a population of 139 (2001). Bereslavka was part of the Vasilyevka village council and bel ...

), Trotsky embraced Marxism after moving to

Mykolaiv

Mykolaiv ( uk, Миколаїв, ) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Southern Ukraine, the Administrative centre, administrative center of the Mykolaiv Oblast. Mykolaiv city, which provides U ...

in 1896. In 1898, he was arrested for revolutionary activities and subsequently exiled to

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

. He escaped from Siberia in 1902 and moved to London, where he befriended

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

. In 1903, he sided with

Julius Martov

Julius Martov or L. Martov (Ма́ртов; born Yuliy Osipovich Tsederbaum; 24 November 1873 – 4 April 1923) was a politician and revolutionary who became the leader of the Mensheviks in early 20th-century Russia. He was arguably the closes ...

's

Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

against Lenin's

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

during the

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

's initial organisational split. Trotsky helped organize the failed

Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

, after which he was again arrested and exiled to Siberia. He once again escaped, and spent the following 10 years working in Britain,

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Switzerland, France, Spain, and the United States. After the 1917

February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

brought an end to the

Tsarist monarchy, Trotsky returned from New York via Canada to Russia and became a leader in the Bolshevik faction. As chairman of the

Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

, he played a key role in the

October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

of November 1917 that overthrew the new

Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

.

Once in government, Trotsky initially held the post of

Commissar for Foreign Affairs and became directly involved in the 1917–1918

Brest-Litovsk negotiations with Germany as Russia pulled out of the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

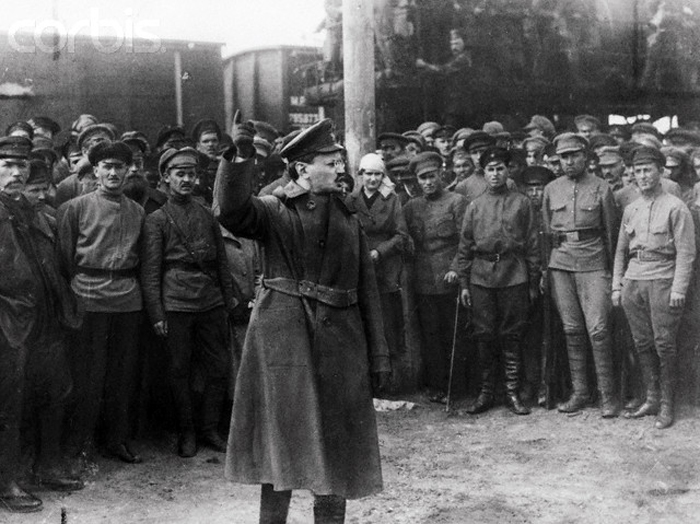

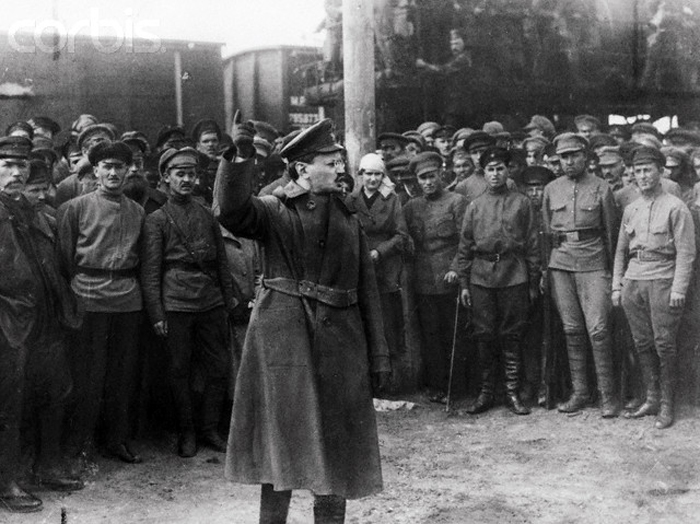

. From March 1918 to January 1925, Trotsky headed the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

as

People's Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs

The Minister of Defence of the Soviet Union refers to the head of the Ministry of Defence who was responsible for defence of the socialist Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from 1917 to 1922 and the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1992.

Pe ...

and played a vital role in the Bolshevik victory in the

Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

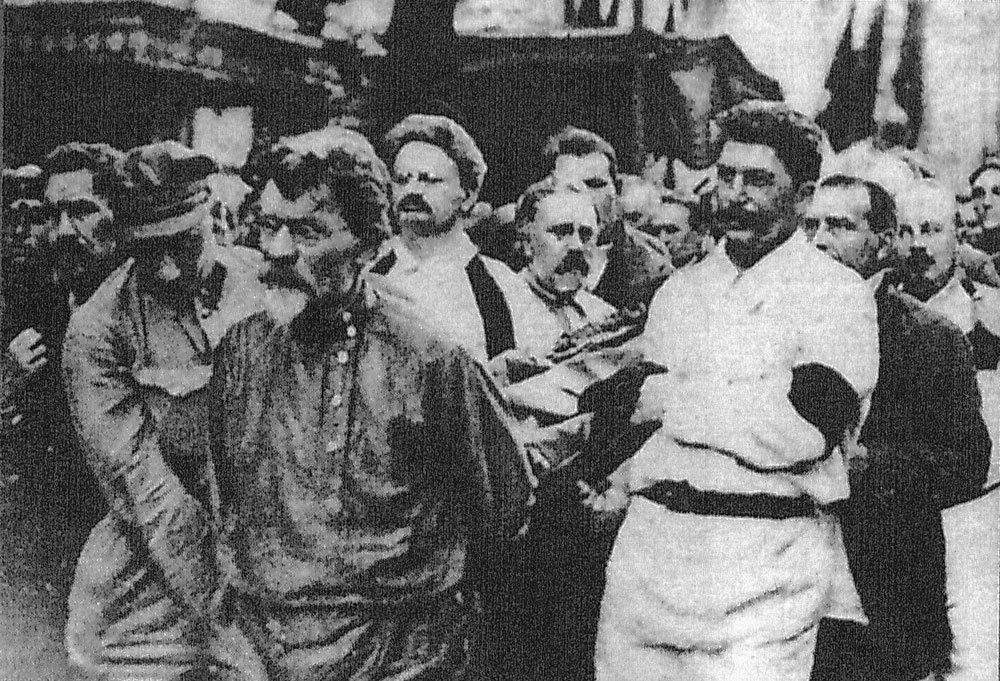

of 1917–1922. He became one of the seven members of the first

Bolshevik Politburo in 1919.

After the death of Lenin in January 1924 and the

rise

Rise or RISE may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* '' Rise: The Vieneo Province'', an internet-based virtual world

* Rise FM, a fictional radio station in the video game ''Grand Theft Auto 3''

* Rise Kujikawa, a video ...

of

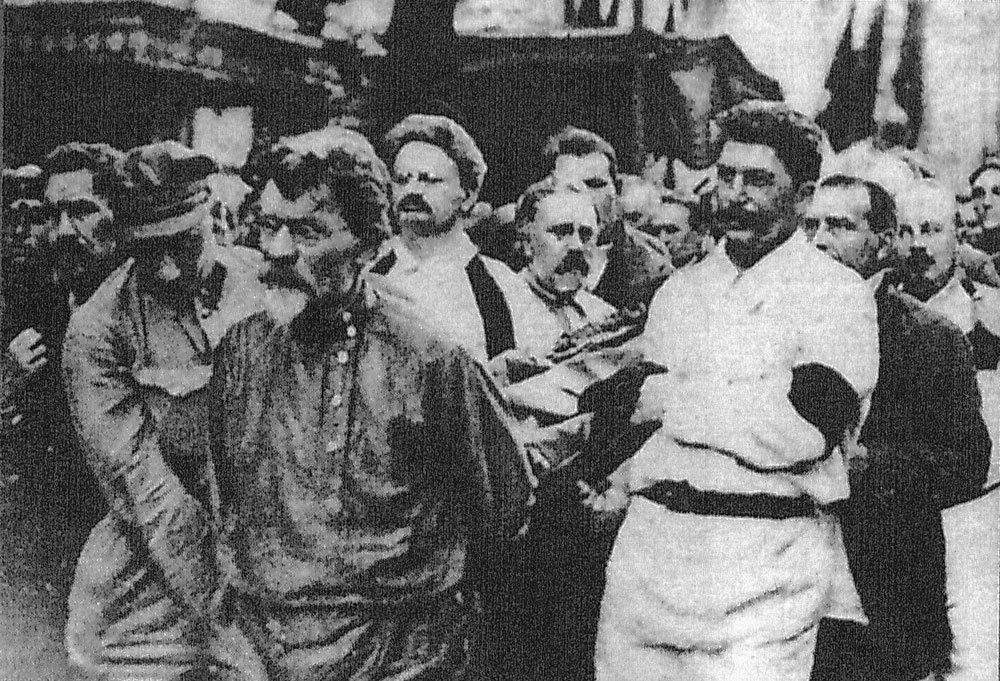

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, Trotsky gradually lost his government positions; the

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contraction ...

eventually expelled him from the Soviet Union in February 1929. He spent the rest of his life in exile, writing prolifically and engaging in open critique of

Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

. In 1938 Trotsky and his supporters founded the

Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) is a revolutionary socialist international organization consisting of followers of Leon Trotsky, also known as Trotskyists, whose declared goal is the overthrowing of global capitalism and the establishment of wor ...

in opposition to Stalin's

Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

. After surviving multiple attempts on his life, Trotsky was assassinated in August 1940 in

Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

by

Ramón Mercader

Jaime Ramón Mercader del Río (7 February 1913 – 18 October 1978),Photograph oMercader's Gravestone/ref> more commonly known as Ramón Mercader, was a Spanish communist and NKVD agent, who assassinated Russian Bolshevik revolutionary Leon Tr ...

, an agent of the Soviet

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

. Written out of Soviet history books under Stalin, Trotsky was one of the few rivals of Stalin to not be rehabilitated by either

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

or

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

. Trotsky's rehabilitation came in 2001 by the

Russian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

.

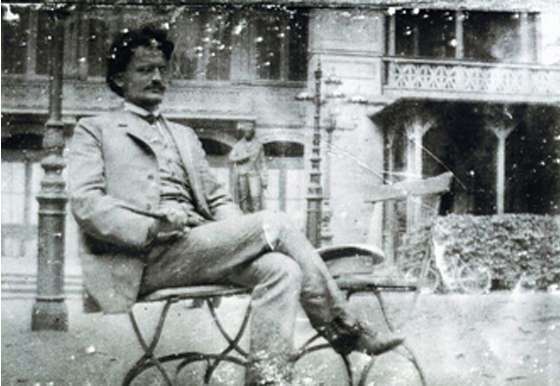

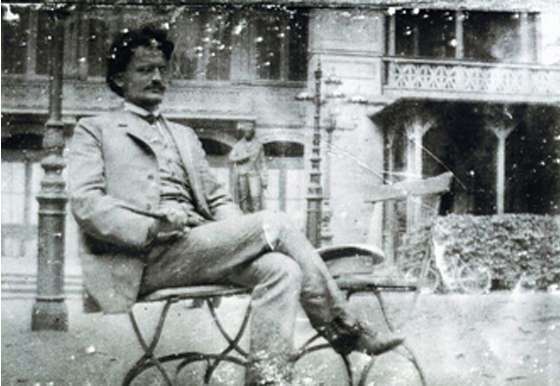

Childhood and family (1879–1895)

Leon Trotsky was born Lev Davidovich Bronstein to David Leontyevich Bronstein (1847–1922) and Anna Lvovna (née Zhivotovskaya, 1850–1910) on 7 November 1879, the fifth child of a wealthy Jewish landowner family in Yanovka,

Kherson governorate

The Kherson Governorate (1802–1922; russian: Херсонская губерния, translit.: ''Khersonskaya guberniya''; uk, Херсонська губернія, translit=Khersonska huberniia), was an administrative territorial unit (als ...

,

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

(now

Bereslavka, Ukraine). His father, David Leontyevich, had lived in

Poltava

Poltava (, ; uk, Полтава ) is a city located on the Vorskla River in central Ukraine. It is the capital city of the Poltava Oblast (province) and of the surrounding Poltava Raion (district) of the oblast. Poltava is administratively ...

, and later moved to Bereslavka, as it had a large Jewish community. Trotsky's younger sister,

Olga

Olga may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Olga (name), a given name, including a list of people and fictional characters named Olga or Olha

* Michael Algar (born 1962), English singer also known as "Olga"

Places

Russia

* Olga, Russia, ...

, who also grew up to be a

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and a Soviet politician, married the prominent Bolshevik

Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. (''né'' Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Bolshevik revolutionary and a prominent Soviet politician.

Born in Moscow to parents who were both involved in revolutionary politics, Kamenev attended Imperial Moscow Uni ...

.

Some authors, notably

Robert Service, have claimed that Trotsky's childhood first name was the

Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

''Leiba''. The American

Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

David North said that this was an assumption based on Trotsky's Jewish birth, but, contrary to Service's claims, there is no documentary evidence to support his using a Yiddish name, when that language was not spoken by his family. Both North and political historian

Walter Laqueur

Walter Ze'ev Laqueur (26 May 1921 – 30 September 2018) was a German-born American historian, journalist and political commentator. He was an influential scholar on the subjects of terrorism and political violence.

Biography

Walter Laqueur was ...

wrote that Trotsky's childhood name was ''Lyova'', a standard Russian diminutive of the name ''Lev.'' North has compared the speculation on Trotsky's given name to the undue emphasis given to his having a Jewish surname.

The language spoken at home was not Yiddish but a mixture of Russian and

Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

(known as

Surzhyk

Surzhyk (, ) refers to a range of mixed sociolects of Ukrainian and Russian languages used in certain regions of Ukraine and the neighboring regions of Russia and Moldova. There is no unifying set of characteristics; the term is, according to so ...

).

When Trotsky was eight, his father sent him to

Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

to be educated. He was enrolled in a Lutheran German-language school (''Realschule zum Heiligen Paulus'' or school of the Lutheran St. Pauls Cathedral, a school of

Black Sea Germans

The Black Sea Germans (german: Schwarzmeerdeutsche; russian: черноморские немцы; uk, чорноморські німці) are ethnic Germans who left their homelands (starting in the late-18th century, but mainly in the e ...

which also admitted students of other faiths and backgrounds), which became Russified during his years in Odessa as a result of the Imperial government's policy of

Russification

Russification (russian: русификация, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

.

Trotsky and his wife Natalia later registered their children as Lutheran, since Austrian law at the time required children to be given religious education "in the faith of their parents". As

Isaac Deutscher

Isaac; grc, Ἰσαάκ, Isaák; ar, إسحٰق/إسحاق, Isḥāq; am, ይስሐቅ is one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. He was th ...

notes in his biography of Trotsky, Odessa was then a bustling cosmopolitan port city, very unlike the typical Russian city of the time. This environment contributed to the development of the young man's international outlook.

Although Trotsky spoke French, English, and German to a good standard, he said in his autobiography ''

My Life My Life may refer to:

Autobiographies

* ''Mein Leben'' (Wagner) (''My Life''), by Richard Wagner, 1870

* ''My Life'' (Clinton autobiography), by Bill Clinton, 2004

* ''My Life'' (Meir autobiography), by Golda Meir, 1973

* ''My Life'' (Mosley a ...

'' that he was never perfectly fluent in any language but Russian.

Raymond Molinier Raymond Molinier (1904–1994) was a leader of the Trotskyist movement in France and a pioneer of the Fourth International.

Molinier was born in Paris. In 1929, founded the journal ''La Vérité'', and in March 1936 he and Pierre Frank co-fou ...

wrote that Trotsky spoke French fluently.

Early political activities and life (1896–1917)

Revolutionary activity and imprisonment (1896–1898)

Trotsky became involved in revolutionary activities in 1896 after moving to the harbor town of Nikolayev (now

Mykolaiv

Mykolaiv ( uk, Миколаїв, ) is a List of cities in Ukraine, city and List of hromadas of Ukraine, municipality in Southern Ukraine, the Administrative centre, administrative center of the Mykolaiv Oblast. Mykolaiv city, which provides U ...

) on the Ukrainian coast of the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

. At first a ''

narodnik

The Narodniks (russian: народники, ) were a politically conscious movement of the Russian intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, ...

'' (revolutionary

agrarian socialist

Agrarian socialism is a political ideology that promotes “the equal distribution of landed resources among collectivized peasant villages” This socialist system places agriculture at the center of the economy instead of the industrialization ...

populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

), he initially opposed

Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

but was won over to Marxism later that year by his future first wife,

Aleksandra Sokolovskaya

Aleksandra Lvovna Sokolovskaya (; 1872 – 29 April 1938) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and Leon Trotsky's first wife. She perished in the Great Purges no earlier than 1938.

Sokolovskaya's father, Lev Sokolovsky, was a Narodnik, who enco ...

. Instead of pursuing a mathematics degree, Trotsky helped organize the South Russian Workers' Union in Nikolayev in early 1897. Using the name "Lvov",

[chapter XVII of his autobiography]

''My Life''

, Marxist Internet Archive he wrote and printed leaflets and proclamations, distributed revolutionary pamphlets, and popularized socialist ideas among industrial workers and revolutionary students.

In January 1898, more than 200 members of the union, including Trotsky, were arrested. He was held for the next two years in prison awaiting trial, first in Nikolayev, then

Kherson

Kherson (, ) is a port city of Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers appr ...

, then Odessa, and finally in Moscow. In the Moscow prison, he came into contact with other revolutionaries, heard about Lenin and read Lenin's book, ''

The Development of Capitalism in Russia

''The Development of Capitalism in Russia'' () was an early economic work by Lenin written whilst he was in exile in Siberia. It was published in 1899 under the pseudonym of "Vladimir Ilyin".Paul Le Blanc (2008) ''Revolution, Democracy, Socialism ...

''. Two months into his imprisonment, on 1–3 March 1898, the first Congress of the newly formed

Russian Social Democratic Labor Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

(RSDLP) was held. From then on Trotsky identified as a member of the party.

First marriage and Siberian exile (1899–1902)

While in the prison in Moscow, in the summer of 1899, Trotsky married Aleksandra Sokolovskaya (1872–1938), a fellow Marxist. The wedding ceremony was performed by a Jewish chaplain.

In 1900, he was sentenced to four years in exile in

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

. Because of their marriage, Trotsky and his wife were allowed to be exiled to the same location in Siberia. They were exiled to

Ust-Kut

Ust-Kut (russian: Усть-Кут) is a town and the administrative center of Ust-Kutsky District in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia, located from Irkutsk, the administrative center of the oblast. Located on a western loop of the Lena River, the town s ...

and the Verkholensk in the

Baikal Lake

Lake Baikal (, russian: Oзеро Байкал, Ozero Baykal ); mn, Байгал нуур, Baigal nuur) is a rift lake in Russia. It is situated in southern Siberia, between the federal subjects of Irkutsk Oblast to the northwest and the Rep ...

region of Siberia. They had two daughters,

Zinaida (1901–1933) and Nina (1902–1928), both born in Siberia.

In Siberia, Trotsky studied philosophy. He became aware of the differences within the party, which had been decimated by arrests in 1898 and 1899. Some social democrats known as "economists" argued that the party should focus on helping industrial workers improve their lot in life and were not so worried about changing the government. They believed that societal reforms would grow out of the worker's struggle for higher pay and better working conditions. Others argued that overthrowing the monarchy was more important and that a well-organized and disciplined revolutionary party was essential. The latter position was expressed by the London-based newspaper ''

Iskra

''Iskra'' ( rus, Искра, , ''the Spark'') was a political newspaper of Russian socialist emigrants established as the official organ of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).

History

Due to political repression under Tsar Nicho ...

'' (''The Spark''), which was founded in 1900. Trotsky quickly sided with the ''Iskra'' position and began writing for the paper.

In the summer of 1902, at the urging of his wife, Aleksandra, Trotsky escaped from Siberia hidden in a load of hay on a wagon. Aleksandra later escaped from Siberia with their daughters. Both daughters married, and Zinaida had children, but the daughters died before their parents. Nina Nevelson died from

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

in 1928, cared for in her last months by her older sister. Zinaida Volkova followed her father into exile in

Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, taking her son by her second marriage but leaving behind a daughter in Russia. Suffering also from tuberculosis and

depression, Zinaida committed suicide in 1933. Aleksandra disappeared in 1935 during the

Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

s in the Soviet Union under Stalin and was murdered by Stalinist forces three years later.

First emigration and second marriage (1902–1903)

Until this point in his life, Trotsky had used his birth name: Lev (Leon) Bronstein. He changed his surname to "Trotsky", the name he would use for the rest of his life. It is said he adopted the name of a jailer of the Odessa prison in which he had earlier been held. This became his primary revolutionary pseudonym. After his escape from Siberia, Trotsky moved to London, joining

Georgi Plekhanov

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov (; rus, Гео́ргий Валенти́нович Плеха́нов, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj vəlʲɪnˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ plʲɪˈxanəf, a=Ru-Georgi Plekhanov-JermyRei.ogg; – 30 May 1918) was a Russian revoluti ...

,

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

,

Julius Martov

Julius Martov or L. Martov (Ма́ртов; born Yuliy Osipovich Tsederbaum; 24 November 1873 – 4 April 1923) was a politician and revolutionary who became the leader of the Mensheviks in early 20th-century Russia. He was arguably the closes ...

and other editors of ''Iskra''. Under the pen name ''Pero'' ("feather" or "pen"), Trotsky soon became one of the paper's leading writers.

Unknown to Trotsky, the six editors of ''Iskra'' were evenly split between the "old guard" led by Plekhanov and the "new guard" led by Lenin and Martov. Plekhanov's supporters were older (in their 40s and 50s), and had spent the previous 20 years together in exile in Europe. Members of the new guard were in their early 30s and had only recently emigrated from Russia. Lenin, who was trying to establish a permanent majority against Plekhanov within ''Iskra,'' expected Trotsky, then 23, to side with the new guard. In March 1903 Lenin wrote:

Because of Plekhanov's opposition, Trotsky did not become a full member of the board. But from then on, he participated in its meetings in an advisory capacity, which earned him Plekhanov's enmity.

In late 1902, Trotsky met

Natalia Sedova

Natalia Ivanovna Sedova (russian: Ната́лья Ива́новна Седо́ва; 5 April 1882 Romny, Russian Empire – 23 January 1962, Corbeil-Essonnes, Paris, France) is best known as the second wife of Leon Trotsky, the Russian revolutio ...

(1882–1962), who soon became his companion. They married in 1903, and she was with him until his death. They had two children together,

Lev Sedov

Lev Lvovich Sedov (russian: Лев Львович Седов, also known as Leon Sedov; 24 February 1906 – 16 February 1938) was the first son of the Russian communist leader Leon Trotsky and his second wife Natalia Sedova. He was born when his f ...

(1906–1938) and

Sergei Sedov

Sergei L. Sedov (1937) was a Soviet engineer and scientist killed in the Great Purge for being the son of Leon Trotsky.

Personal life

The son of Leon Trotsky by his second wife, and younger brother of Lev Sedov, Sergei L. Sedov was born in . H ...

(1908–1937), both of whom would predecease their parents. Regarding his sons' surnames, Trotsky later explained that after the 1917 revolution:

Trotsky never used the name "Sedov" either privately or publicly. Natalia Sedova sometimes signed her name "Sedova-Trotskaya".

Split with Lenin (1903–1904)

In the meantime, after a period of secret police repression and internal confusion that followed the

First Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1898, ''Iskra'' succeeded in convening the party's

Second Congress in London in August 1903. Trotsky and other ''Iskra'' editors attended. The first congress went as planned, with ''Iskra'' supporters handily defeating the few "economist" delegates. Then the congress discussed the position of the

Jewish Bund

The General Jewish Labour Bund in Lithuania, Poland and Russia ( yi, אַלגעמײנער ייִדישער אַרבעטער־בונד אין ליטע, פּױלן און רוסלאַנד , translit=Algemeyner Yidisher Arbeter-bund in Lite, Poy ...

, which had co-founded the

RSDLP

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

in 1898 but wanted to remain autonomous within the party.

[Trotsky, Leon. ''My life: an attempt at an autobiography''. Courier Corporation, 2007.]

Shortly after that, the pro-Iskra delegates unexpectedly split into two factions. The split was initially over an organisational issue. Lenin and his supporters, the Bolsheviks, argued for a smaller but highly organized party where only party members would be seen as members, while Martov and his supporters, the

Menshevik

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

s, argued for a bigger and less disciplined party where people who assisted the party would also be seen as members. In a surprise development, Trotsky and most of the Iskra editors supported Martov and the Mensheviks, while Plekhanov supported Lenin and the

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. During 1903 and 1904, many members changed sides in the factions. Plekhanov soon parted ways with the Bolsheviks. Trotsky left the Mensheviks in September 1904 over their insistence on an alliance with Russian liberals and their opposition to a reconciliation with Lenin and the Bolsheviks.

From 1904 until 1917, Trotsky described himself as a "non-factional social democrat". He worked between 1904 and 1917, trying to reconcile different groups within the party, which resulted in many clashes with Lenin and other prominent party members. Trotsky later maintained that he had been wrong in opposing Lenin on the issue of the party. During these years, Trotsky began developing his theory of

permanent revolution

Permanent revolution is the strategy of a revolutionary class pursuing its own interests independently and without compromise or alliance with opposing sections of society. As a term within Marxist theory, it was first coined by Karl Marx and ...

and developed a close working relationship with

Alexander Parvus

Alexander Lvovich Parvus, born Israel Lazarevich Gelfand (8 September 1867 – 12 December 1924) and sometimes called Helphand in the literature on the Russian Revolution, was a Marxist theoretician, publicist, and controversial activist in the ...

in 1904–07.

During their split, Lenin referred to Trotsky as "Little Judas" (''Iudushka'', based on the character from

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin

Mikhail Yevgrafovich Saltykov-Shchedrin ( rus, Михаи́л Евгра́фович Салтыко́в-Щедри́н, p=mʲɪxɐˈil jɪvˈɡrafəvʲɪtɕ səltɨˈkof ɕːɪˈdrʲin; – ), born Mikhail Yevgrafovich Saltykov and known during ...

's novel ''

The Golovlyov Family

''The Golovlyov Family'' (russian: Господа Головлёвы, translit=Gospoda Golovlyovy; also translated as ''The Golovlevs'' or ''A Family of Noblemen: The Gentlemen Golovliov'') is a novel by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, written in the ...

''), a "scoundrel" and a "swine".

1905 revolution and trial (1905–1906)

The unrest and agitation against the Russian government came to a head in

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

on 3 January 1905 (

Julian Calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandr ...

), when a strike broke out at the

Putilov Works

The Kirov Plant, Kirov Factory or Leningrad Kirov Plant (LKZ) ( rus, Кировский завод, Kirovskiy zavod) is a major Russian mechanical engineering and agricultural machinery manufacturing plant in St. Petersburg, Russia. It was establ ...

in the city. This single strike grew into a general strike, and by 7 January 1905, there were 140,000 strikers in Saint Petersburg.

On Sunday, 9 January 1905, Father

Georgi Gapon

Georgy Apollonovich Gapon. ( –) was a Russian Orthodox priest and a popular working-class leader before the 1905 Russian Revolution. After he was discovered to be a police informant, Gapon was murdered by members of the Socialist Revolutionary ...

knowingly led a procession of radicals mixed within larger groups of ordinary working citizens through the streets to the

Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Emperor of all the Russias, Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The p ...

to supposedly beseech the Tsar for food and relief from the government. According to Gapon himself, he led the people into a Palace Guard already on the defensive due to the crowd instigating violence against them. They will eventually fire on the demonstration, resulting in the deaths of an unknown number of violent radicals, peaceful demonstrators and police caught within the melee. Although Sunday, 9 January 1905, became known as

Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence agai ...

, Gapon's own biography points to a conspiracy. This will later be confirmed by Russian police records listing the number of known militant radicals found among the dead.

Following the events of Bloody Sunday, Trotsky secretly returned to Russia in February 1905, by way of

Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

. At first he wrote leaflets for an underground printing press in Kyiv, but soon moved to the capital, Saint Petersburg. There he worked with both Bolsheviks, such as

Central Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of Communist party, communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party org ...

member

Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (russian: Леони́д Бори́сович Кра́син; 15 July 1870 – 24 November 1926) was a Russian Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary politician and a Soviet diplomat. In 1 ...

, and the local Menshevik committee, which he pushed in a more radical direction. The latter, however, were betrayed by a secret police agent in May, and Trotsky had to flee to rural

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

. There he worked on fleshing out his theory of permanent revolution.

On 19 September 1905, the typesetters at the

Ivan Sytin

Ivan Dmitrievich Sytin (russian: Ива́н Дми́триевич Сы́тин; 5 February 185123 November 1934) was a Russian publisher. The son of a Soligalich peasant, he built the largest publishing house in pre-revolutionary Russian Empire, ...

's printing house in Moscow went out on strike for shorter hours and higher pay. By the evening of 24 September, the workers at 50 other printing shops in Moscow were also on strike. On 2 October 1905, the typesetters in printing shops in Saint Petersburg decided to strike in support of the Moscow strikers. On 7 October 1905, the railway workers of the

Moscow–Kazan Railway

The Moscow-Kazan railway was opened in 1893.

In 1890 the ''Moscow-Kazan Railway Association'' was established after negotiations with the government. In 1891 Nikolai von Meck, the son of Karl Otto Georg von Meck was appointed with the patronage ...

went out on strike. Amid the resulting confusion, Trotsky returned from Finland to Saint Petersburg on 15 October 1905. On that day, Trotsky spoke before the Saint Petersburg Soviet Council of Workers Deputies, which was meeting at the Technological Institute in the city. Also attending were some 200,000 people crowded outside to hear the speeches—about half of all workers in Saint Petersburg.

After his return, Trotsky and

Parvus took over the newspaper ''Russian Gazette,'' increasing its circulation to 500,000. Trotsky also co-founded, together with Parvus and Julius Martov and other Mensheviks, "Nachalo" ("The Beginning"), which also proved to be a very successful newspaper in the revolutionary atmosphere of Saint Petersburg in 1905.

Just before Trotsky's return, the Mensheviks had independently come up with the same idea that Trotsky had: an elected non-party revolutionary organization representing the capital's workers, the first

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

("Council") of Workers. By the time of Trotsky's arrival, the

Saint Petersburg Soviet

The Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Delegates (later the Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Deputies) was a workers' council, or soviet, in Saint Petersburg in 1905.

Origins

The Soviet had its origins in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, when Nicholas II ...

was already functioning, headed by

Khrustalyev-Nosar (Georgy Nosar, alias Pyotr Khrustalyov). Khrustalyev-Nosar had been a compromise figure when elected as the head of the Saint Petersburg Soviet. He was a lawyer that stood above the political factions contained in the Soviet.

However, since his election, he proved to be very popular with the workers in spite of the Bolsheviks' original opposition to him. Khrustalev-Nosar became famous in his position as spokesman for the Saint Petersburg Soviet. Indeed, to the outside world, Khrustalev-Nosar was the embodiment of the Saint Petersburg Soviet. Trotsky joined the Soviet under the name "Yanovsky" (after the village he was born in, Yanovka) and was elected vice-chairman. He did much of the actual work at the Soviet and, after Khrustalev-Nosar's arrest on 26 November 1905, was elected its chairman. On 2 December, the Soviet issued a proclamation which included the following statement about the Tsarist government and its foreign debts:

The following day, the Soviet was surrounded by troops loyal to the government and the deputies were arrested. Trotsky and other Soviet leaders were tried in 1906 on charges of supporting an armed rebellion. On 4 October 1906 he was convicted and sentenced to internal exile to Siberia.

Second emigration (1907–1914)

While en route to exile in

Obdorsk

Salekhard (russian: Салеха́рд; Khanty: , ''Pułñawat''; yrk, Саляʼ харад, ''Saljaꜧ harad'') is a town in Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Russia, serving as the okrug's administrative centre. It crosses the Arctic Circle, th ...

, Siberia, in January 1907, Trotsky escaped at

Berezov and once again made his way to London. He attended the

5th Congress of the RSDLP. In October, he moved to

Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Austria-Hungary. For the next seven years, he often took part in the activities of the

Austrian Social Democratic Party

The Social Democratic Party of Austria (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs , SPÖ), founded and known as the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria (german: link=no, Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei Österreichs, SDAPÖ) unti ...

and, occasionally, of the

German Social Democratic Party

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been the ...

.

In Vienna, Trotsky became close to

Adolph Joffe

Adolph Abramovich Joffe (russian: Адо́льф Абра́мович Ио́ффе, alternative transliterations Adol'f Ioffe or, rarely, Yoffe) (10 October 1883 in Simferopol – 16 November 1927 in Moscow) was a Russian revolutionary, a Bo ...

, his friend for the next 20 years, who introduced him to

psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek: + . is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques"What is psychoanalysis? Of course, one is supposed to answer that it is many things — a theory, a research method, a therapy, a body of knowledge. In what might b ...

.

In October 1908 he was asked to join the editorial staff of ''

Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the co ...

'' ("Truth"), a bi-weekly, Russian-language social democratic paper for Russian workers, which he co-edited with Adolph Joffe and

Matvey Skobelev

Matvey Ivanovich Skobelev (russian: Матве́й Ива́нович Ско́белев; November 9, 1885, Baku – July 29, 1938, Moscow) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and politician.

Biography

Trotsky's Disciple in Vienna (1908–1912)

S ...

. It was smuggled into Russia. The paper appeared very irregularly; only five issues were published in its first year.

Avoiding factional politics, the paper proved popular with Russian industrial workers. Both the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks split multiple times after the failure of the 1905–1907 revolution. Money was very scarce for the publication of ''Pravda''. Trotsky approached the

Russian Central Committee to seek financial backing for the newspaper throughout 1909.

A majority of Bolsheviks controlled the Central Committee in 1910. Lenin agreed to the financing of "Pravda", but required a Bolshevik to be appointed as co-editor of the paper. When various Bolshevik and Menshevik factions tried to re-unite at the January 1910 RSDLP Central Committee meeting in Paris over Lenin's objections, Trotsky's ''Pravda'' was made a party-financed 'central organ'. Lev Kamenev, Trotsky's brother-in-law, was added to the editorial board from the Bolsheviks, but the unification attempts failed in August 1910. Kamenev resigned from the board amid mutual recriminations. Trotsky continued publishing ''Pravda'' for another two years until it finally folded in April 1912.

The Bolsheviks started a new workers-oriented newspaper in Saint Petersburg on 22 April 1912 and also called it ''Pravda''. Trotsky was so upset by what he saw as a usurpation of his newspaper's name that in April 1913, he wrote a letter to

Nikolay Chkheidze

Nikoloz Chkheidze ( ka, ნიკოლოზ (კარლო) ჩხეიძე; russian: Никола́й (Карло) Семёнович Чхеи́дзе, translit=Nikolay (Karlo) Semyonovich Chkheidze) commonly known as Karlo Chkheidze ( � ...

, a Menshevik leader, bitterly denouncing Lenin and the Bolsheviks. Though he quickly got over the disagreement, the message was intercepted by the

Russian police

The Police of Russia () is the national law-enforcement agency in Russia, operating under the Ministry of Internal Affairs from . It was established by decree from Peter the Great and in 2011, replacing the Militsiya, the former police service. ...

, and a copy was put into their archives. Shortly after Lenin's death in 1924, the letter was found and publicized by Trotsky's opponents within the Communist Party to portray him as Lenin's enemy.

The 1910s were a period of heightened tension within the RSDLP, leading to numerous frictions between Trotsky, the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks. The most serious disagreement that Trotsky and the Mensheviks had with Lenin at the time was over the issue of "expropriations", i.e., armed robbery of banks and other companies by Bolshevik groups to procure money for the Party. These actions had been banned by the 5th Congress, but were continued by the Bolsheviks.

In January 1912, the majority of the Bolshevik faction, led by Lenin, as well as a few defecting Mensheviks, held a conference in

Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

and decided to break away from the

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

, and formed a new party, the

Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks)

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first)Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

. In response, Trotsky organized a "unification" conference of social democratic factions in Vienna in August 1912 (a.k.a. "The August Bloc") and tried to re-unite the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks into one party. The attempt was generally unsuccessful.

In Vienna, Trotsky continuously published articles in radical Russian and Ukrainian newspapers, such as ''Kievskaya Mysl,'' under a variety of pseudonyms, often using "Antid Oto". In September 1912, ''Kievskaya Mysl'' sent him to the Balkans as its war correspondent, where he covered the two

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defe ...

for the next year. While there, Trotsky chronicled the ethnic cleansing carried out by the Serbian army against the Albanian civilian population. He became a close friend of

Christian Rakovsky

Christian Georgievich Rakovsky (russian: Христиа́н Гео́ргиевич Рако́вский; bg, Кръстьо Георги́ев Рако́вски; – September 11, 1941) was a Bulgarian-born socialist revolutionary, a Bolshevi ...

, later a leading Soviet politician and Trotsky's ally in the Soviet Communist Party. On 3 August 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, in which

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

fought against the Russian Empire, Trotsky was forced to flee Vienna for neutral Switzerland to avoid arrest as a Russian

émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followi ...

.

World War I (1914–1917)

The outbreak of World War I caused a sudden realignment within the RSDLP and other European social democratic parties over the issues of war, revolution, pacifism and internationalism, redividing the party into defeatists and defencists. Within the RSDLP, Lenin, Trotsky and Martov advocated various internationalist anti-war positions that saw defeat for your own country's ruling class imperialists as the "lesser evil" in the war, while they opposed all imperialists in the imperialist war. These anti-war believers were known as "defeatists". Those who supported one side over the other in the war were known as "defencists". Plekhanov and many other defencist social democrats (both Bolsheviks and Mensheviks) supported the Russian government to some extent and wanted them to win the war, while Trotsky's ex-colleague Parvus, now a defencist, sided against Russia so strongly that he wanted Germany to win the war. In Switzerland, Trotsky briefly worked within the

Swiss Socialist Party

The Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei der Schweiz; SP; rm, Partida Socialdemocrata da la Svizra) or Swiss Socialist Party (french: Parti socialiste suisse, it, Partito Socialista Svizzero; PS), is a polit ...

, prompting it to adopt an internationalist resolution. He wrote a book opposing the war, ''The War and the International,'' and the pro-war position taken by the European social democratic parties, primarily the German party.

As a war correspondent for the ''Kievskaya Mysl'', Trotsky moved to France on 19 November 1914. In January 1915 in Paris, he began editing (at first with Martov, who soon resigned as the paper moved to the left) ''

Nashe Slovo

''Nashe Slovo'' ( rus, Наше Слово, Our Word) was a daily Russian language socialist newspaper published in France during the First World War. Although it only appeared for a little over a year and a half, it had an impact across Europe.

...

'' ("Our Word"), an internationalist socialist newspaper. He adopted the slogan of "peace without indemnities or annexations, peace without conquerors or conquered." Lenin advocated Russia's defeat in the war and demanded a complete break with the

Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second International continued th ...

.

Trotsky attended the

Zimmerwald Conference

The Zimmerwald Conference was held in Zimmerwald, Switzerland, from September 5 to 8, 1915. It was the first of three international socialist conferences convened by anti-militarist socialist parties from countries that were originally neutral d ...

of anti-war socialists in September 1915 and advocated a middle course between those who, like Martov, would stay within the Second International at any cost and those who, like Lenin, would break with the Second International and form a

Third International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by a ...

. The conference adopted the middle line proposed by Trotsky. At first opposed, in the end Lenin voted for Trotsky's resolution to avoid a split among anti-war socialists.

In September 1916, Trotsky was deported from France to Spain for his anti-war activities. Spanish authorities did not want him and deported him to the United States on 25 December 1916. He arrived in New York City on 13 January 1917. He stayed for nearly three months at 1522 Vyse Avenue in

The Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New Y ...

. In New York he wrote articles for the local

Russian language

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic languages, East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the First language, native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European langua ...

socialist newspaper, ''

Novy Mir

''Novy Mir'' (russian: links=no, Новый мир, , ''New World'') is a Russian-language monthly literary magazine.

History

''Novy Mir'' has been published in Moscow since January 1925. It was supposed to be modelled on the popular pre-Soviet ...

,'' and the Yiddish-language daily,

''Der Forverts'' (''The Jewish Daily Forward''), in translation. He also made speeches to Russian émigrés.

Trotsky was living in New York City when the

February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

of 1917 overthrew

Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Polan ...

. He left New York on 27 March 1917, but his ship, the ''

SS Kristianiafjord

SS ''Kristianiafjord'' was the first ship in the fleet of the Norwegian America Line, built by Cammell Laird in Birkenhead, UK. The name refers to the fjord leading into the Norwegian capital Oslo, at the time called Kristiania. Launched from it ...

,'' was intercepted by

British naval officials in Canada at

Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

. He was detained for a month at

Amherst Internment Camp

Amherst Internment Camp was an internment camp that existed from 1914 to 1919 in Amherst, Nova Scotia. It was the largest internment camp camp in Canada during World War I; a maximum of 853 prisoners were housed at one time at the old Malleable I ...

in

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. While imprisoned in the camp, Trotsky established an increasing friendship with the workers and sailors amongst his fellow inmates, describing his month at the camp as "one continual mass meeting".

[''Leon Trotsky: My Life – In a Concentration Camp''](_blank)

, ns1758.ca; accessed 31 January 2018.

Trotsky's speeches and agitation incurred the wrath of German officer inmates who complained to the British camp commander, Colonel Morris, about Trotsky's "anti-patriotic" attitude.

Morris then forbade Trotsky to make any more public speeches, leading to 530 prisoners protesting and signing a petition against Morris' order.

Back in Russia, after initial hesitation and facing pressure from the workers' and peasants' Soviets, the Russian foreign minister

Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, p=mʲɪlʲʊˈkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Con ...

was compelled to demand the release of Trotsky as a Russian citizen, and the British government freed him on 29 April 1917.

He reached Russia on 17 May 1917. After his return, Trotsky substantially agreed with the Bolshevik position, but did not join them right away. Russian social democrats were split into at least six groups, and the Bolsheviks were waiting for the next party Congress to determine which factions to merge with. Trotsky temporarily joined the

Mezhraiontsy

The Mezhraiontsy ( rus, межрайонцы, p=mʲɪʐrɐˈjɵnt͡sɨ), usually translated as the "Interdistrictites,"''Mezhraionka'' and ''Mezhraiontsy'' are derived from the Russian ''"mezh-"'' (meaning "inter-" or "between'") + ''"raion"'' (me ...

, a regional social democratic organization in Saint Petersburg, and became one of its leaders. At the First

Congress of Soviets

The Congress of Soviets was the supreme governing body of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and several other Soviet republics from 1917 to 1936 and a somewhat similar Congress of People's Deputies from 1989 to 1991. After the crea ...

in June, he was elected a member of the first

All-Russian Central Executive Committee

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee ( rus, Всероссийский Центральный Исполнительный Комитет, Vserossiysky Centralny Ispolnitelny Komitet, VTsIK) was the highest legislative, administrative and r ...

("VTsIK") from the Mezhraiontsy faction.

After an unsuccessful pro-Bolshevik uprising in Saint Petersburg, Trotsky was arrested on 7 August 1917. He was released 40 days later in the aftermath of the failed counter-revolutionary

uprising by Lavr Kornilov. After the Bolsheviks gained a majority in the

Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

, Trotsky was elected chairman on .

He sided with Lenin against

Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, . Transliterated ''Grigorii Evseevich Zinov'ev'' according to the Library of Congress system. (born Hirsch Apfelbaum, – 25 August 1936), known also under the name Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky (russian: Ов ...

and Lev Kamenev when the Bolshevik Central Committee discussed staging an armed uprising, and he led the efforts to overthrow the

Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

headed by

Aleksandr Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months from late July to early Novembe ...

.

The following summary of Trotsky's role in 1917 was written by Stalin in ''Pravda'', 6 November 1918.

[In One And The Same Issue](_blank)

New International, Vol. 2 No. 6, October 1935, p. 208 Although this passage was quoted in Stalin's book ''The October Revolution'' (1934),

it was expunged from Stalin's ''Works'' (1949).

After the success of the uprising on 7–8 November 1917, Trotsky led the efforts to repel a

counter-attack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "Military exercise, war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific object ...

by

Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

under General

Pyotr Krasnov

Pyotr Nikolayevich Krasnov ( rus, Пётр Николаевич Краснов; 22 September (old style: 10 September) 1869 – 17 January 1947), sometimes referred to in English as Peter Krasnov, was a Don Cossack historian and officer, promot ...

and other troops still loyal to the overthrown Provisional Government at

Gatchina

The town of Gatchina ( rus, Га́тчина, , ˈɡatːɕɪnə, links=y) serves as the administrative center of the Gatchinsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It lies south-south-west of St. Petersburg, along the E95 highway which ...

. Allied with Lenin, he defeated attempts by other Bolshevik Central Committee members (Zinoviev, Kamenev, Rykov, etc.) to share power with other socialist parties. By the end of 1917, Trotsky was unquestionably the second man in the Bolshevik Party after Lenin. He overshadowed the ambitious Zinoviev, who had been Lenin's top lieutenant over the previous decade, but whose star appeared to be fading. This reversal of position contributed to continuing competition and enmity between the two men, which lasted until 1926 and did much to destroy them both.

On 23 November 1917, Trotsky revealed the

secret treaty arrangements which had been made between the Tsarist Regime, Britain and France, causing them considerable embarrassment.

Russian Revolution and aftermath

Commissar for Foreign Affairs and Brest-Litovsk (1917–1918)

After the Bolsheviks came to power, Trotsky became the

People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs

The Ministry of External Relations (MER) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) (russian: Министерство иностранных дел СССР) was founded on 6 July 1923. It had three names during its existence: People's Co ...

and published the

secret treaties

A secret treaty is a treaty (international agreement) in which the contracting state parties have agreed to conceal the treaty's existence or substance from other states and the public.Helmut Tichy and Philip Bittner, "Article 80" in Olivier D� ...

previously signed by the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

that detailed plans for post-war reallocation of colonies and redrawing state borders.

In preparation for peace talks with the representatives of the German government and the representatives of the other Central Powers leading up to the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

, Leon Trotsky appointed his old friend Joffe to represent the Bolsheviks. When the Soviet delegation learned that Germans and Austro-Hungarians planned to annex slices of Polish territory and to set up a rump Polish state with what remained, while the Baltic provinces were to become client states ruled by German princes, the talks were recessed for 12 days. The Soviets' only hopes were that, given time, their allies would agree to join the negotiations or that the western European proletariat would revolt, so their best strategy was to prolong the negotiations. As Foreign Minister Leon Trotsky wrote, "To delay negotiations, there must be someone to do the delaying". Therefore, Trotsky replaced Joffe as the leader of the Soviet delegation during the peace negotiations in

Brest-Litovsk

Brest ( be, Брэст / Берасьце, Bieraście, ; russian: Брест, ; uk, Берестя, Berestia; lt, Brasta; pl, Brześć; yi, בריסק, Brisk), formerly Brest-Litovsk (russian: Брест-Литовск, lit=Lithuanian Br ...

from 22 December 1917 to 10 February 1918. At that time the Soviet government was split on the issue.

Left Communists

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices espoused by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions which they rega ...

, led by

Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (russian: Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин) ( – 15 March 1938) was a Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet politician, Marxist philosopher and economist and prolific author on revolutionary theory. ...

, continued to believe that there could be no peace between a Soviet republic and a capitalist country, and that only a revolutionary war leading to a pan-European Soviet republic would bring a durable peace.

They cited the successes of the newly formed (15 January 1918) voluntary

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

against Polish forces of Gen.

Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki

Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki (Iosif Romanovich while in the Russian military; sometimes also Dowbór-Muśnicki; ; 25 October 1867 – 26 October 1937) was a Russian military officer and Polish general, serving with the Imperial Russian and then Poli ...

in Belarus,

White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

forces in the

Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

region, and newly independent Ukrainian forces as proof that the Red Army could repel German forces, especially if propaganda and

asymmetrical warfare

Asymmetric warfare (or asymmetric engagement) is the term given to describe a type of war between belligerents whose relative military power, strategy or tactics differ significantly. This is typically a war between a standing, professional arm ...

were used.

They were willing to hold talks with the Germans as a means of exposing German imperial ambitions (territorial gains,

reparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

, etc.) in the hope of accelerating the hoped−for Soviet revolution in the West. Still, they were dead set against signing any peace treaty. In the case of a German ultimatum, they advocated proclaiming a revolutionary war against Germany to inspire Russian and European workers to fight for socialism. This opinion was shared by

Left Socialist Revolutionaries

The Party of Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (russian: Партия левых социалистов-революционеров-интернационалистов) was a revolutionary socialist political party formed during the Russian Revol ...

, who were then the Bolsheviks' junior partners in a coalition government.

Lenin, who had earlier hoped for a speedy Soviet revolution in Germany and other parts of Europe, quickly decided that the imperial government of Germany was still firmly in control and that, without a strong Russian military, an armed conflict with Germany would lead to a collapse of the Soviet government in Russia. He agreed with the Left Communists that ultimately a pan-European Soviet revolution would solve all problems, but until then the Bolsheviks had to stay in power. Lenin did not mind prolonging the negotiating process for maximum propaganda effect, but, from January 1918 on, advocated signing a separate peace treaty if faced with a German ultimatum. Trotsky's position was between these two Bolshevik factions. Like Lenin, he admitted that the old Russian military, inherited from the monarchy and the Provisional Government and in advanced stages of decomposition, was unable to fight:

But he agreed with the Left Communists that a separate peace treaty with an imperialist power would be a terrible morale and material blow to the Soviet government, negate all its military and political successes of 1917 and 1918, resurrect the notion that the Bolsheviks secretly allied with the German government, and cause an upsurge of internal resistance. He argued that any German ultimatum should be refused, and that this might well lead to an uprising in Germany, or at least inspire German soldiers to disobey their officers since any German offensive would be a naked grab for territories. Trotsky wrote in 1925:

Germany resumed

military operations

A military operation is the coordinated military actions of a state, or a non-state actor, in response to a developing situation. These actions are designed as a military plan to resolve the situation in the state or actor's favor. Operations may ...

on 18 February. Within a day, it became clear that the German army was capable of conducting offensive operations and that Red Army detachments, which were relatively small, poorly organized and poorly led, were no match for it. On the evening of 18 February 1918, Trotsky and his supporters in the committee abstained, and Lenin's proposal was accepted 7–4. The Soviet government sent a

radiogram to the German side, taking the final Brest-Litovsk peace terms.

Germany did not respond for three days and continued its offensive, encountering little resistance. The response arrived on 21 February, but the proposed terms were so harsh that even Lenin briefly thought that the Soviet government had no choice but to fight. But in the end, the committee again voted 7–4 on 23 February 1918; the

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace, separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russian SFSR, Russia and the Central Powers (German Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Kingdom of ...

was signed on 3 March and ratified on 15 March 1918. Since Trotsky was so closely associated with the policy previously followed by the Soviet delegation at Brest-Litovsk, he resigned from his position as Commissar for Foreign Affairs to remove a potential obstacle to the new policy.

Head of the Red Army (spring 1918)

The entire Bolshevik leadership of the Red Army, including People's Commissar (defence minister)

Nikolai Podvoisky

Nikolai Ilyich Podvoisky (russian: Николай Ильич Подвойский; February 16 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S_February_4.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>O.S_February_4">Old_Style_and_New_S ...

and commander-in-chief

Nikolai Krylenko

Nikolai Vasilyevich Krylenko ( rus, Никола́й Васи́льевич Крыле́нко, p=krɨˈlʲenkə; May 2, 1885 – July 29, 1938) was an Old Bolshevik and Soviet politician. Krylenko served in a variety of posts in the Sovie ...

, protested vigorously and eventually resigned. They believed that the Red Army should consist only of dedicated revolutionaries, rely on propaganda and force, and have elected officers. They viewed former imperial officers and generals as potential traitors who should be kept out of the new military, much less put in charge of it. Their views continued to be popular with many Bolsheviks throughout most of the

Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, and their supporters, including Podvoisky, who became one of Trotsky's deputies, were a constant thorn in Trotsky's side. The discontent with Trotsky's policies of strict discipline, conscription and reliance on carefully supervised non-Communist military experts eventually led to the

Military Opposition The Military Opposition was a group of delegates to the VIII Congress of the RCP (b), held from March 18 to March 23, 1919, who advocated the preservation of partisan methods of commanding the army and waging war, against building a regular army, a ...

, which was active within the Communist Party in late 1918–1919.

On 13 March 1918, Trotsky's resignation as Commissar for Foreign Affairs was officially accepted, and he was appointed People's Commissar of Army and Navy Affairs—in place of Podvoisky—and chairman of the Supreme Military Council. The post of commander-in-chief was abolished, and Trotsky gained full control of the Red Army, responsible only to the Communist Party leadership, whose Left Socialist Revolutionary allies had left the government over

Brest-Litovsk

Brest ( be, Брэст / Берасьце, Bieraście, ; russian: Брест, ; uk, Берестя, Berestia; lt, Brasta; pl, Brześć; yi, בריסק, Brisk), formerly Brest-Litovsk (russian: Брест-Литовск, lit=Lithuanian Br ...

.

[Left Socialist-Revolutionaries (Left SRs)](_blank)

; Glossary of organizations on Marxists.org

Marxists Internet Archive (also known as MIA or Marxists.org) is a non-profit online encyclopedia that hosts a multilingual library (created in 1990) of the works of communist, anarchist, and socialist writers, such as Karl Marx, Friedrich Enge ...

Civil War (1918–1920)

1918

The military situation soon tested Trotsky's managerial and organization-building skills. In May–June 1918, the

Czechoslovak Legions

, image = Coat of arms of the Czechoslovak Legion.svg

, image_size = 200px

, alt =

, caption = Czechoslovak Legion coat of arms

, start_date ...

''en route'' from European Russia to

Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

rose against the Soviet government. This left the Bolsheviks with the loss of most of the country's territory, an increasingly well-organized resistance by Russian anti-Communist forces (usually referred to as the

White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

after their best-known component) and widespread defection by the military experts whom Trotsky relied on.

Trotsky and the government responded with a full-fledged

mobilisation

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and t ...

, which increased the size of the Red Army from fewer than 300,000 in May 1918 to one million in October, and an introduction of

political commissars into the army. The latter had the task of ensuring the loyalty of military experts (mostly former officers in the imperial army) and co-signing their orders. Trotsky regarded the organisation of the Red Army as built on the ideas of the October Revolution. As he later wrote in his autobiography:

In response to

Fanya Kaplan

Fanny Efimovna Kaplan (russian: Фа́нни Ефи́мовна Капла́н, links=no; real name Feiga Haimovna Roytblat, ; February 10, 1890 – September 3, 1918) was a Ukrainian Jewish woman, Socialist-Revolutionary, and early Soviet dissi ...

's failed assassination of Lenin on 30 August 1918, and to the successful assassination of the Petrograd

Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə), abbreviated ...

chief

Moisei Uritsky

Moisei Solomonovich Uritsky ( ua, Мойсей Соломонович Урицький; russian: Моисей Соломонович Урицкий; – 30 August 1918) was a Bolshevik revolutionary leader in Russia. After the October Revol ...

on 17 August 1918, the Bolsheviks instructed

Felix Dzerzhinsky

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky ( pl, Feliks Dzierżyński ; russian: Фе́ликс Эдму́ндович Дзержи́нский; – 20 July 1926), nicknamed "Iron Felix", was a Bolshevik revolutionary and official, born into Poland, Polish n ...

to commence a

Red Terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

, announced in the 1 September 1918 issue of the ''Krasnaya Gazeta'' (''Red Gazette''). Regarding the Red Terror Trotsky wrote: