Tosca on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Tosca'' is an

According to the libretto, the action of ''Tosca'' occurs in Rome in June 1800. Sardou, in his play, dates it more precisely; ''La Tosca'' takes place in the afternoon, evening, and early morning of 17 and 18 June 1800.

Italy had long been divided into a number of small states, with the Pope in Rome ruling the

According to the libretto, the action of ''Tosca'' occurs in Rome in June 1800. Sardou, in his play, dates it more precisely; ''La Tosca'' takes place in the afternoon, evening, and early morning of 17 and 18 June 1800.

Italy had long been divided into a number of small states, with the Pope in Rome ruling the

The first draft libretto that Illica produced for Puccini resurfaced in 2000 after being lost for many years. It contains considerable differences from the final libretto, relatively minor in the first two acts but much more appreciable in the third, where the description of the Roman dawn that opens the third act is much longer, and Cavaradossi's tragic aria, the eventual "E lucevan le stelle", has different words. The 1896 libretto also offers a different ending, in which Tosca does not die but instead goes mad. In the final scene, she cradles her lover's head in her lap and hallucinates that she and her Mario are on a gondola, and that she is asking the gondolier for silence. Sardou refused to consider this change, insisting that as in the play, Tosca must throw herself from the parapet to her death.Nicassio, p. 227 Puccini agreed with Sardou, telling him that the mad scene would have the audiences anticipate the ending and start moving towards the cloakrooms. Puccini pressed his librettists hard, and Giacosa issued a series of melodramatic threats to abandon the work.Fisher, p. 23 The two librettists were finally able to give Puccini what they hoped was a final version of the libretto in 1898.Budden, p. 185

Little work was done on the score during 1897, which Puccini devoted mostly to performances of ''

The first draft libretto that Illica produced for Puccini resurfaced in 2000 after being lost for many years. It contains considerable differences from the final libretto, relatively minor in the first two acts but much more appreciable in the third, where the description of the Roman dawn that opens the third act is much longer, and Cavaradossi's tragic aria, the eventual "E lucevan le stelle", has different words. The 1896 libretto also offers a different ending, in which Tosca does not die but instead goes mad. In the final scene, she cradles her lover's head in her lap and hallucinates that she and her Mario are on a gondola, and that she is asking the gondolier for silence. Sardou refused to consider this change, insisting that as in the play, Tosca must throw herself from the parapet to her death.Nicassio, p. 227 Puccini agreed with Sardou, telling him that the mad scene would have the audiences anticipate the ending and start moving towards the cloakrooms. Puccini pressed his librettists hard, and Giacosa issued a series of melodramatic threats to abandon the work.Fisher, p. 23 The two librettists were finally able to give Puccini what they hoped was a final version of the libretto in 1898.Budden, p. 185

Little work was done on the score during 1897, which Puccini devoted mostly to performances of ''

By December 1899, ''Tosca'' was in rehearsal at the

By December 1899, ''Tosca'' was in rehearsal at the

/nowiki> complete triumph", and Ricordi's London representative quickly signed a contract to take ''Tosca'' to New York. The premiere at the  In 1992 a television version of the opera was filmed at the locations prescribed by Puccini, at the times of day at which each act takes place. Featuring

In 1992 a television version of the opera was filmed at the locations prescribed by Puccini, at the times of day at which each act takes place. Featuring

uccini/nowiki> finds in his palette all colours, all shades; in his hands, the instrumental texture becomes completely supple, the gradations of sonority are innumerable, the blend unfailingly grateful to the ear." However, one critic described act 2 as overly long and wordy; another echoed Illica and Giacosa in stating that the rush of action did not permit enough lyricism, to the great detriment of the music. A third called the opera "three hours of noise".Phillips-Matz, p. 119

The critics gave the work a generally kinder reception in London, where ''The Times'' called Puccini "a master in the art of poignant expression", and praised the "wonderful skill and sustained power" of the music.Greenfeld, pp. 125–126 In ''

opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

in three acts by Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini (Lucca, 22 December 1858Bruxelles, 29 November 1924) was an Italian composer known primarily for his operas. Regarded as the greatest and most successful proponent of Italian opera after Verdi, he was descended from a long li ...

to an Italian libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

by Luigi Illica

Luigi Illica (9 May 1857 – 16 December 1919) was an Italian librettist who wrote for Giacomo Puccini (usually with Giuseppe Giacosa), Pietro Mascagni, Alfredo Catalani, Umberto Giordano, Baron Alberto Franchetti and other important Italian co ...

and Giuseppe Giacosa

Giuseppe Giacosa (21 October 1847 – 1 September 1906) was an Italian poet, playwright and librettist.

Life

He was born in Colleretto Parella, now Colleretto Giacosa, near Turin. His father was a magistrate. Giuseppe went to the University of ...

. It premiered at the Teatro Costanzi

The Teatro dell'Opera di Roma (Rome Opera House) is an opera house in Rome, Italy. Originally opened in November 1880 as the 2,212 seat ''Costanzi Theatre'', it has undergone several changes of name as well modifications and improvements. The pre ...

in Rome on 14 January 1900. The work, based on Victorien Sardou

Victorien Sardou ( , ; 5 September 18318 November 1908) was a French dramatist. He is best remembered today for his development, along with Eugène Scribe, of the well-made play. He also wrote several plays that were made into popular 19th-centur ...

's 1887 French-language dramatic play, ''La Tosca

''La Tosca'' is a five- act drama by the 19th-century French playwright Victorien Sardou. It was first performed on 24 November 1887 at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin in Paris, with Sarah Bernhardt in the title role. Despite negative ...

'', is a melodrama

A modern melodrama is a dramatic work in which the plot, typically sensationalized and for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodramas typically concentrate on dialogue that is often bombastic or exces ...

tic piece set in Rome in June 1800, with the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

's control of Rome threatened by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's invasion of Italy. It contains depictions of torture, murder, and suicide, as well as some of Puccini's best-known lyrical arias.

Puccini saw Sardou's play when it was touring Italy in 1889 and, after some vacillation, obtained the rights to turn the work into an opera in 1895. Turning the wordy French play into a succinct Italian opera took four years, during which the composer repeatedly argued with his librettists and publisher. ''Tosca'' premiered at a time of unrest in Rome, and its first performance was delayed for a day for fear of disturbances. Despite indifferent reviews from the critics, the opera was an immediate success with the public.

Musically, ''Tosca'' is structured as a through-composed

In music theory of musical form, through-composed music is a continuous, non- sectional, and non- repetitive piece of music. The term is typically used to describe songs, but can also apply to instrumental music.

While most musical forms such as t ...

work, with aria

In music, an aria (Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompanime ...

s, recitative

Recitative (, also known by its Italian name "''recitativo''" ()) is a style of delivery (much used in operas, oratorios, and cantatas) in which a singer is allowed to adopt the rhythms and delivery of ordinary speech. Recitative does not repea ...

, choruses and other elements musically woven into a seamless whole. Puccini used Wagnerian

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

leitmotif

A leitmotif or leitmotiv () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is an anglici ...

s to identify characters, objects and ideas. While critics have often dismissed the opera as a facile melodrama with confusions of plot—musicologist Joseph Kerman

Joseph Wilfred Kerman (3 April 1924 – 17 March 2014) was an American musicologist and music critic. Among the leading musicologists of his generation, his 1985 book ''Contemplating Music: Challenges to Musicology'' (published in the UK as ''Mu ...

famously called it a "shabby little shocker"Kerman, p. 205—the power of its score and the inventiveness of its orchestration have been widely acknowledged. The dramatic force of ''Tosca'' and its characters continues to fascinate both performers and audiences, and the work remains one of the most frequently performed operas. Many recordings of the work have been issued, both of studio and live performances.

Background

The French playwrightVictorien Sardou

Victorien Sardou ( , ; 5 September 18318 November 1908) was a French dramatist. He is best remembered today for his development, along with Eugène Scribe, of the well-made play. He also wrote several plays that were made into popular 19th-centur ...

wrote more than 70 plays, almost all of them successful, and none of them performed today. In the early 1880s Sardou began a collaboration with actress Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (; born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 or 23 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including '' La Dame Aux Camel ...

, whom he provided with a series of historical melodramas. His third Bernhardt play, ''La Tosca'', which premiered in Paris on 24 November 1887, and in which she starred throughout Europe, was an outstanding success, with more than 3,000 performances in France alone.

Puccini had seen ''La Tosca'' at least twice, in Milan and Turin. On 7 May 1889 he wrote to his publisher, Giulio Ricordi

Giulio Ricordi (19 December 1840 in Milan – 6 June 1912 in Milan) was an Italian editing, editor and musician who joined the family firm, the Casa Ricordi music publishing house, in 1863, then run by his father, Tito, the son of the company' ...

, begging him to get Sardou's permission for the work to be made into an opera: "I see in this ''Tosca'' the opera I need, with no overblown proportions, no elaborate spectacle, nor will it call for the usual excessive amount of music."

Ricordi sent his agent in Paris, Emanuele Muzio

Donnino Emanuele Muzio (or ''Mussio'') (24 August 1821 in Zibello – 27 November 1890 in Paris) was an Italian composer, conductor and vocal teacher. He was a lifelong friend and the only student of Giuseppe Verdi.

Biography

In April 1844, V ...

, to negotiate with Sardou, who preferred that his play be adapted by a French composer. He complained about the reception ''La Tosca'' had received in Italy, particularly in Milan, and warned that other composers were interested in the piece. Nonetheless, Ricordi reached terms with Sardou and assigned the librettist Luigi Illica

Luigi Illica (9 May 1857 – 16 December 1919) was an Italian librettist who wrote for Giacomo Puccini (usually with Giuseppe Giacosa), Pietro Mascagni, Alfredo Catalani, Umberto Giordano, Baron Alberto Franchetti and other important Italian co ...

to write a scenario for an adaptation.Phillips-Matz, p. 109

In 1891, Illica advised Puccini against the project, most likely because he felt the play could not be successfully adapted to a musical form. When Sardou expressed his unease at entrusting his most successful work to a relatively new composer whose music he did not like, Puccini took offence. He withdrew from the agreement, which Ricordi then assigned to the composer Alberto Franchetti

Alberto Franchetti (18 September 1860 – 4 August 1942) was an Italian composer, best known for the 1902 opera ''Germania''.

Biography

Alberto Franchetti was born in Turin, a Jewish nobleman of independent means. He studied first in Venice, the ...

. Illica wrote a libretto for Franchetti, who was never at ease with the assignment.

When Puccini once again became interested in ''Tosca'', Ricordi was able to get Franchetti to surrender the rights so he could recommission Puccini. One story relates that Ricordi convinced Franchetti that the work was too violent to be successfully staged. A Franchetti family tradition holds that Franchetti gave the work back as a grand gesture, saying, "He has more talent than I do." American scholar Deborah Burton contends that Franchetti gave it up simply because he saw little merit in it and could not feel the music in the play. Whatever the reason, Franchetti surrendered the rights in May 1895, and in August Puccini signed a contract to resume control of the project.Phillips-Matz, p. 18

Roles

Synopsis

Historical context

According to the libretto, the action of ''Tosca'' occurs in Rome in June 1800. Sardou, in his play, dates it more precisely; ''La Tosca'' takes place in the afternoon, evening, and early morning of 17 and 18 June 1800.

Italy had long been divided into a number of small states, with the Pope in Rome ruling the

According to the libretto, the action of ''Tosca'' occurs in Rome in June 1800. Sardou, in his play, dates it more precisely; ''La Tosca'' takes place in the afternoon, evening, and early morning of 17 and 18 June 1800.

Italy had long been divided into a number of small states, with the Pope in Rome ruling the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

in Central Italy

Central Italy ( it, Italia centrale or just ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first-level NUTS region, and a European Parliament constituency.

Regions

Central It ...

. Following the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, a French army under Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

invaded Italy in 1796, entering Rome almost unopposed on 11 February 1798 and establishing a republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

there. Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI ( it, Pio VI; born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, 25 December 171729 August 1799) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1775 to his death in August 1799.

Pius VI condemned the French Revoluti ...

was taken prisoner, and was sent into exile on February 20, 1798. (Pius VI would die in exile in 1799, and his successor, Pius VII

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a m ...

, who was elected in Venice on 14 March 1800, would not enter Rome until 3 July. There is thus neither a Pope nor papal government in Rome during the days depicted in the opera.) The new republic was ruled by seven consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

; in the opera this is the office formerly held by Angelotti, whose character may be based on the real-life consul Liborio Angelucci. In September 1799 the French, who had protected the republic, withdrew from Rome. As they left, troops of the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples ( la, Regnum Neapolitanum; it, Regno di Napoli; nap, Regno 'e Napule), also known as the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was ...

occupied the city.Nicassio, pp. 48–49

In May 1800 Napoleon, by then the undisputed leader of France, brought his troops across the Alps to Italy once again. On 14 June his army met the Austrian forces at the Battle of Marengo

The Battle of Marengo was fought on 14 June 1800 between French forces under the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte and Austrian forces near the city of Alessandria, in Piedmont, Italy. Near the end of the day, the French overcame General Mich ...

(near Alessandria). Austrian troops were initially successful; by mid-morning they were in control of the field of battle. Their commander, Michael von Melas

Michael Friedrich Benedikt Baron von Melas (12 May 1729 – 31 May 1806) was a Transylvanian-born field marshal for the Austrian Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.

He was born in Radeln, Transylvania (nowadays Roadeș, part of Bunești commune ...

, sent this news south towards Rome. However, fresh French troops arrived in late afternoon, and Napoleon attacked the tired Austrians. As Melas retreated in disarray with the remains of his army, he sent a second courier south with the revised message. The Neapolitans abandoned Rome, and the city spent the next fourteen years under French domination.Nicassio, pp. 204–205

Act 1

''Inside the church ofSant'Andrea della Valle

Sant'Andrea della Valle is a minor basilica in the rione of Sant'Eustachio of the city of Rome, Italy. The basilica is the general seat for the religious order of the Theatines. It is located at Piazza Vidoni, at the intersection of Corso Vittori ...

''

Cesare Angelotti, former consul of the Roman Republic and now an escaped political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

, runs into the church and hides in the Attavanti private chapel – his sister, the Marchesa Attavanti, has left a key to the chapel hidden at the feet of the statue of the Madonna

Madonna Louise Ciccone (; ; born August 16, 1958) is an American singer-songwriter and actress. Widely dubbed the " Queen of Pop", Madonna has been noted for her continual reinvention and versatility in music production, songwriting, a ...

. The elderly Sacristan

A sacristan is an officer charged with care of the sacristy, the church, and their contents.

In ancient times, many duties of the sacrist were performed by the doorkeepers ( ostiarii), and later by the treasurers and mansionarii. The Decretals ...

enters and begins cleaning. The Sacristan kneels in prayer as the Angelus

The Angelus (; Latin for "angel") is a Catholic devotion commemorating the Incarnation of Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ o ...

sounds.

The painter Mario Cavaradossi arrives to continue work on his picture of Mary Magdalene

Mary Magdalene (sometimes called Mary of Magdala, or simply the Magdalene or the Madeleine) was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to crucifixion of Jesus, his cru ...

. The Sacristan identifies a likeness between the portrait and a blonde-haired woman who has been visiting the church recently (unknown to him, it is Angelotti's sister the Marchesa). Cavaradossi describes the "hidden harmony" ("Recondita armonia

"Recondita armonia" is the first romanza in the opera ''Tosca'' (1900) by Giacomo Puccini. It is sung by the painter Mario Cavaradossi when comparing his love, Tosca, to a portrait of Mary Magdalene that he is painting.Te Deum

The "Te Deum" (, ; from its incipit, , ) is a Latin Christian hymn traditionally ascribed to AD 387 authorship, but with antecedents that place it much earlier. It is central to the Ambrosian hymnal, which spread throughout the Latin Ch ...

; exclaiming 'Tosca, you make me forget even God!', Scarpia joins the chorus in the prayer.

Act 2

''Scarpia's apartment in thePalazzo Farnese

Palazzo Farnese () or Farnese Palace is one of the most important High Renaissance List of palaces in Italy#Rome, palaces in Rome. Owned by the Italian Republic, it was given to the French government in 1936 for a period of 99 years, and cur ...

, that evening''

Scarpia, at supper, sends a note to Tosca asking her to come to his apartment, anticipating that two of his goals will soon be fulfilled at once. His agent, Spoletta, arrives to report that Angelotti remains at large, but Cavaradossi has been arrested for questioning. He is brought in, and an interrogation ensues. As the painter steadfastly denies knowing anything about Angelotti's escape, Tosca's voice is heard singing a celebratory cantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir.

The meaning of ...

elsewhere in the Palace.

She enters the apartment in time to see Cavaradossi being escorted to an antechamber. All he has time to say is that she mustn't tell them anything. Scarpia then claims she can save her lover from indescribable pain if she reveals Angelotti's hiding place. She resists, but the sound of screams coming through the door eventually breaks her down, and she tells Scarpia to search the well in the garden of Cavaradossi's villa.

Scarpia orders his torturers to cease, and the bloodied painter is dragged back in. He is devastated to discover that Tosca has betrayed his friend. Sciarrone, another agent, then enters with news: there was an upset on the battlefield at Marengo, and the French are marching on Rome. Cavaradossi, unable to contain himself, gloats to Scarpia that his rule of terror will soon be at an end. This is enough for the police to consider him guilty, and they haul him away to be executed.

Scarpia, now alone with Tosca, proposes a bargain: if she gives herself to him, Cavaradossi will be freed. She is revolted, and repeatedly rejects his advances, but she hears the drums outside announcing an execution. As Scarpia awaits her decision, she prays, asking why God has abandoned her in her hour of need: "Vissi d'arte

"Vissi d'arte" is a soprano aria from act 2 of the opera '' Tosca'' by Giacomo Puccini. It is sung by Floria Tosca as she thinks of her fate, how the life of her beloved, Mario Cavaradossi, is at the mercy of Baron Scarpia and why God has seeming ...

" ("I lived for art"). She tries to offer money, but Scarpia is not interested in that kind of bribe: he wants Tosca herself.

Spoletta returns with the news that Angelotti has killed himself upon discovery, and that everything is in place for Cavaradossi's execution. Scarpia hesitates to give the order, looking to Tosca, and despairingly she agrees to submit to him. He tells Spoletta to arrange a mock execution, both men repeating that it will be "as we did with Count Palmieri", and Spoletta exits.

Tosca insists that Scarpia must provide safe-conduct out of Rome for herself and Cavaradossi. He easily agrees to this and heads to his desk. While he's drafting the document, she quietly takes a knife from the supper table. Scarpia triumphantly strides toward Tosca. When he begins to embrace her, she stabs him, crying "this is Tosca's kiss!" Once she's certain he's dead, she ruefully says "now I forgive him." She removes the safe-conduct from his pocket, lights candles in a gesture of piety, and places a crucifix on the body before leaving.

Act 3

''The upper parts of theCastel Sant'Angelo

The Mausoleum of Hadrian, usually known as Castel Sant'Angelo (; English: ''Castle of the Holy Angel''), is a towering cylindrical building in Parco Adriano, Rome, Italy. It was initially commissioned by the Roman Emperor Hadrian as a mausol ...

, early the following morning''

A shepherd boy is heard offstage singing (in Romanesco dialect

Romanesco () is one of the central Italian dialects spoken in the Metropolitan City of Rome Capital, especially in the core city. It is linguistically close to Tuscan and Standard Italian, with some notable differences from these two. Rich in ...

) "Io de' sospiri" ("I give you sighs") as church bells sound for matins

Matins (also Mattins) is a canonical hour in Christian liturgy, originally sung during the darkness of early morning.

The earliest use of the term was in reference to the canonical hour, also called the vigil, which was originally celebrated by ...

. The guards lead Cavaradossi in and a jailer informs him that he has one hour to live. He declines to see a priest, but asks permission to write a letter to Tosca. He begins to write, but is soon overwhelmed by memories: "E lucevan le stelle

"" ("And the stars were shining") is a romantic aria from the third act of Giacomo Puccini's opera ''Tosca'' from 1900, composed to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. It is sung in act 3 by Mario Cavaradossi (tenor), a pain ...

" ("And the stars shone").

Tosca enters and shows him the safe-conduct pass she has obtained, adding that she has killed Scarpia and that the imminent execution is a sham. Cavaradossi must feign death, after which they can flee together before Scarpia's body is discovered. Cavaradossi is awestruck by his gentle lover's courage: "O dolci mani" ("Oh sweet hands"). The pair ecstatically imagine the life they will share, far from Rome. Tosca then anxiously coaches Cavaradossi on how to play dead when the firing squad shoots at him with blanks. He promises he will fall "like Tosca in the theatre".

Cavaradossi is led away, and Tosca watches with increasing impatience as the firing squad prepares. The men fire, and Tosca praises the realism of his fall, "Ecco un artista!" ("What an actor!"). Once the soldiers have left, she hurries towards Cavaradossi, urging him, "Mario, su presto!" ("Mario, up quickly!"), only to find that Scarpia betrayed her: the bullets were real. Heartbroken, she clasps her lover's lifeless body and weeps.

The voices of Spoletta, Sciarrone, and the soldiers are heard, shouting that Scarpia is dead and Tosca has killed him. As the men rush in, Tosca rises, evades their clutches, and runs to the parapet. Crying "O Scarpia, avanti a Dio!" ("O Scarpia, we meet before God!"), she flings herself over the edge to her death.

Adaptation and writing

Sardou's five-act play ''La Tosca'' contains a large amount of dialogue and exposition. While the broad details of the play are present in the opera's plot, the original work contains many more characters and much detail not present in the opera. In the play the lovers are portrayed as though they were French: the character Floria Tosca is closely modelled on Bernhardt's personality, while her lover Cavaradossi, of Roman descent, is born in Paris. Illica andGiuseppe Giacosa

Giuseppe Giacosa (21 October 1847 – 1 September 1906) was an Italian poet, playwright and librettist.

Life

He was born in Colleretto Parella, now Colleretto Giacosa, near Turin. His father was a magistrate. Giuseppe went to the University of ...

, the playwright who joined the project to polish the verses, needed not only to cut back the play drastically, but to make the characters' motivations and actions suitable for Italian opera. Giacosa and Puccini repeatedly clashed over the condensation, with Giacosa feeling that Puccini did not really want to complete the project.

The first draft libretto that Illica produced for Puccini resurfaced in 2000 after being lost for many years. It contains considerable differences from the final libretto, relatively minor in the first two acts but much more appreciable in the third, where the description of the Roman dawn that opens the third act is much longer, and Cavaradossi's tragic aria, the eventual "E lucevan le stelle", has different words. The 1896 libretto also offers a different ending, in which Tosca does not die but instead goes mad. In the final scene, she cradles her lover's head in her lap and hallucinates that she and her Mario are on a gondola, and that she is asking the gondolier for silence. Sardou refused to consider this change, insisting that as in the play, Tosca must throw herself from the parapet to her death.Nicassio, p. 227 Puccini agreed with Sardou, telling him that the mad scene would have the audiences anticipate the ending and start moving towards the cloakrooms. Puccini pressed his librettists hard, and Giacosa issued a series of melodramatic threats to abandon the work.Fisher, p. 23 The two librettists were finally able to give Puccini what they hoped was a final version of the libretto in 1898.Budden, p. 185

Little work was done on the score during 1897, which Puccini devoted mostly to performances of ''

The first draft libretto that Illica produced for Puccini resurfaced in 2000 after being lost for many years. It contains considerable differences from the final libretto, relatively minor in the first two acts but much more appreciable in the third, where the description of the Roman dawn that opens the third act is much longer, and Cavaradossi's tragic aria, the eventual "E lucevan le stelle", has different words. The 1896 libretto also offers a different ending, in which Tosca does not die but instead goes mad. In the final scene, she cradles her lover's head in her lap and hallucinates that she and her Mario are on a gondola, and that she is asking the gondolier for silence. Sardou refused to consider this change, insisting that as in the play, Tosca must throw herself from the parapet to her death.Nicassio, p. 227 Puccini agreed with Sardou, telling him that the mad scene would have the audiences anticipate the ending and start moving towards the cloakrooms. Puccini pressed his librettists hard, and Giacosa issued a series of melodramatic threats to abandon the work.Fisher, p. 23 The two librettists were finally able to give Puccini what they hoped was a final version of the libretto in 1898.Budden, p. 185

Little work was done on the score during 1897, which Puccini devoted mostly to performances of ''La bohème

''La bohème'' (; ) is an opera in four acts,Puccini called the divisions ''quadri'', ''tableaux'' or "images", rather than ''atti'' (acts). composed by Giacomo Puccini between 1893 and 1895 to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe G ...

''. The opening page of the autograph ''Tosca'' score, containing the motif that would be associated with Scarpia, is dated January 1898. At Puccini's request, Giacosa irritably provided new lyrics for the act 1 love duet. In August, Puccini removed several numbers from the opera, according to his biographer, Mary Jane Phillips-Matz

Mary Jane Phillips-Matz (January 30, 1926 – January 19, 2013) was an American biographer and writer on opera. She is mainly known for her biography of Giuseppe Verdi, a result of 30 years' research and published in 1992 by Oxford University Press ...

, "cuting

Ing, ING or ing may refer to:

Art and media

* '' ...ing'', a 2003 Korean film

* i.n.g, a Taiwanese girl group

* The Ing, a race of dark creatures in the 2004 video game '' Metroid Prime 2: Echoes''

* "Ing", the first song on The Roches' 1992 ...

''Tosca'' to the bone, leaving three strong characters trapped in an airless, violent, tightly wound melodrama that had little room for lyricism".Phillips-Matz, p. 115 At the end of the year, Puccini wrote that he was "busting his balls" on the opera.

Puccini asked clerical friends for words for the congregation to mutter at the start of the act 1 Te Deum

The "Te Deum" (, ; from its incipit, , ) is a Latin Christian hymn traditionally ascribed to AD 387 authorship, but with antecedents that place it much earlier. It is central to the Ambrosian hymnal, which spread throughout the Latin Ch ...

; when nothing they provided satisfied him, he supplied the words himself. For the Te Deum music, he investigated the melodies to which the hymn was set in Roman churches, and sought to reproduce the cardinal's procession authentically, even to the uniforms of the Swiss Guards. He adapted the music to the exact pitch of the great bell of St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

, and was equally diligent when writing the music that opens act 3, in which Rome awakens to the sounds of church bells. He journeyed to Rome and went to the Castel Sant'Angelo to measure the sound of matins

Matins (also Mattins) is a canonical hour in Christian liturgy, originally sung during the darkness of early morning.

The earliest use of the term was in reference to the canonical hour, also called the vigil, which was originally celebrated by ...

bells there, as they would be heard from its ramparts. Puccini had bells for the Roman dawn cast to order by four different foundries. This apparently did not have its desired effect, as Illica wrote to Ricordi

Ricordi may refer to:

People

*Giovanni Ricordi (1785–1853), Italian violinist and publishing company founder

* Giulio Ricordi (1840–1912), Italian publisher and musician

Music

*Casa Ricordi, an Italian music publishing company established i ...

on the day after the premiere, "the great fuss and the large amount of money for the bells have constituted an additional folly, because it passes completely unnoticed". Nevertheless, the bells provide a source of trouble and expense to opera companies performing ''Tosca'' to this day.

In act 2, when Tosca sings offstage the cantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir.

The meaning of ...

that celebrates the supposed defeat of Napoleon, Puccini was tempted to follow the text of Sardou's play and use the music of Giovanni Paisiello

Giovanni Paisiello (or Paesiello; 9 May 1740 – 5 June 1816) was an Italian composer of the Classical era, and was the most popular opera composer of the late 1700s. His operatic style influenced Mozart and Rossini.

Life

Paisiello was born in T ...

, before finally writing his own imitation of Paisello's style.Osborne, p. 139 It was not until 29 September 1899 that Puccini was able to mark the final page of the score as completed. Despite the notation, there was additional work to be done, such as the shepherd boy's song at the start of act 3. Puccini, who always sought to put local colour in his works, wanted that song to be in Roman dialect

Romanesco () is one of the central Italian dialects spoken in the Metropolitan City of Rome Capital, especially in the core city. It is linguistically close to Tuscan and Standard Italian, with some notable differences from these two. Rich in ...

. The composer asked a friend to have a "good romanesco poet" write some words; eventually the poet and folklorist wrote the verse which, after slight modification, was placed in the opera.Budden, p. 194

In October 1899, Ricordi realized that some of the music for Cavaradossi's act 3 aria, "O dolci mani" was borrowed from music Puccini had cut from his early opera, ''Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and ''gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, rev ...

'' and demanded changes. Puccini defended his music as expressive of what Cavaradossi must be feeling at that point, and offered to come to Milan to play and sing act 3 for the publisher. Ricordi was overwhelmed by the completed act 3 prelude, which he received in early November, and softened his views, though he was still not completely happy with the music for "O dolci mani". In any event time was too short before the scheduled January 1900 premiere to make any further changes.

Reception and performance history

Premiere

By December 1899, ''Tosca'' was in rehearsal at the

By December 1899, ''Tosca'' was in rehearsal at the Teatro Costanzi

The Teatro dell'Opera di Roma (Rome Opera House) is an opera house in Rome, Italy. Originally opened in November 1880 as the 2,212 seat ''Costanzi Theatre'', it has undergone several changes of name as well modifications and improvements. The pre ...

.Budden, p. 197 Because of the Roman setting, Ricordi arranged a Roman premiere for the opera, even though this meant that Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (; ; March 25, 1867January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orch ...

could not conduct it as Puccini had planned—Toscanini was fully engaged at La Scala

La Scala (, , ; abbreviation in Italian of the official name ) is a famous opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the ' (New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala). The premiere performan ...

in Milan. Leopoldo Mugnone was appointed to conduct. The accomplished (but temperamental) soprano Hariclea Darclée

Hariclea Darclée (née Haricli; later Hartulari; 10 June 1860 – 12 January 1939) was a celebrated Romanian operatic soprano who had a three-decade-long career.

Darclée's repertoire ranged from coloratura soprano roles to heavier Verdi role ...

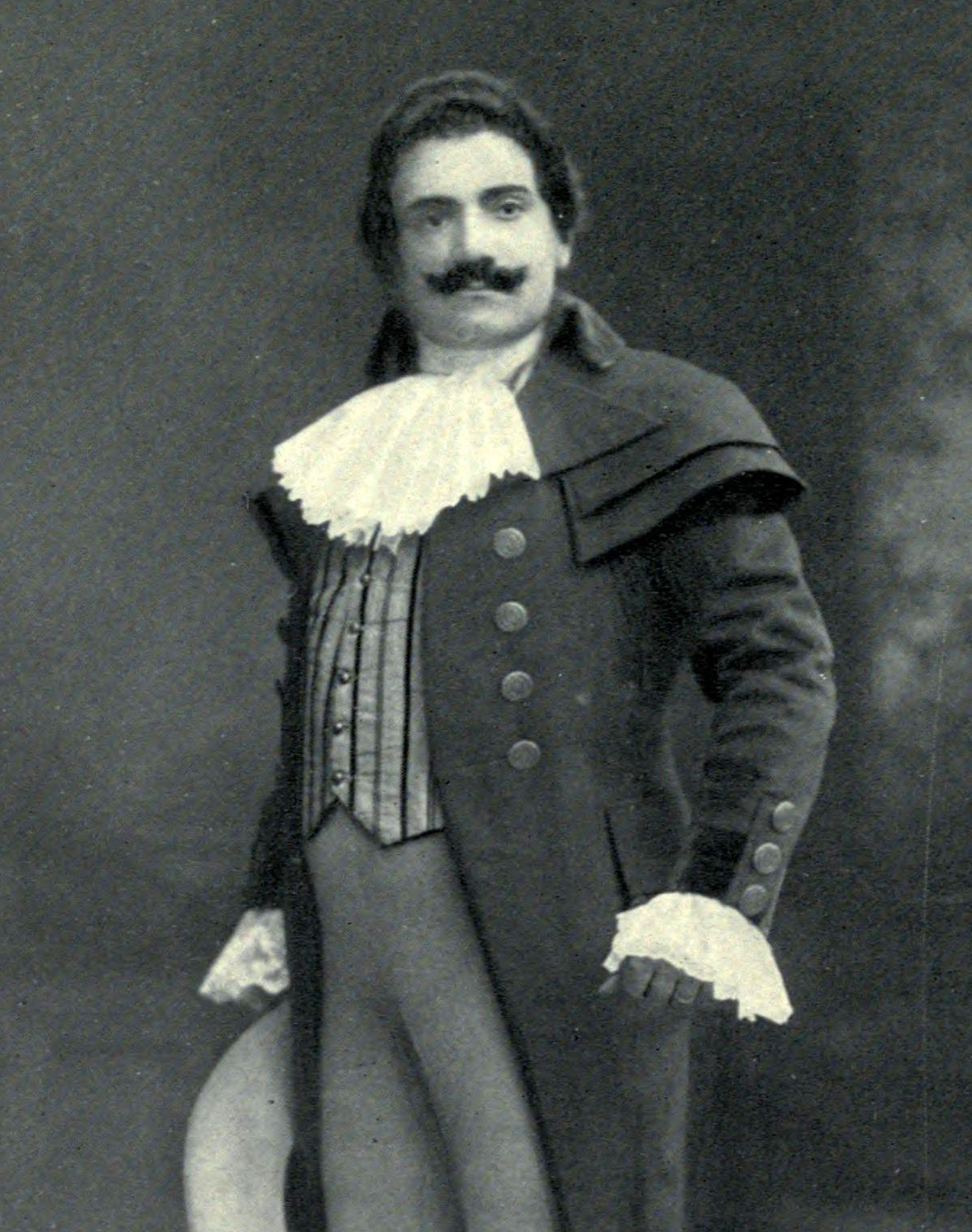

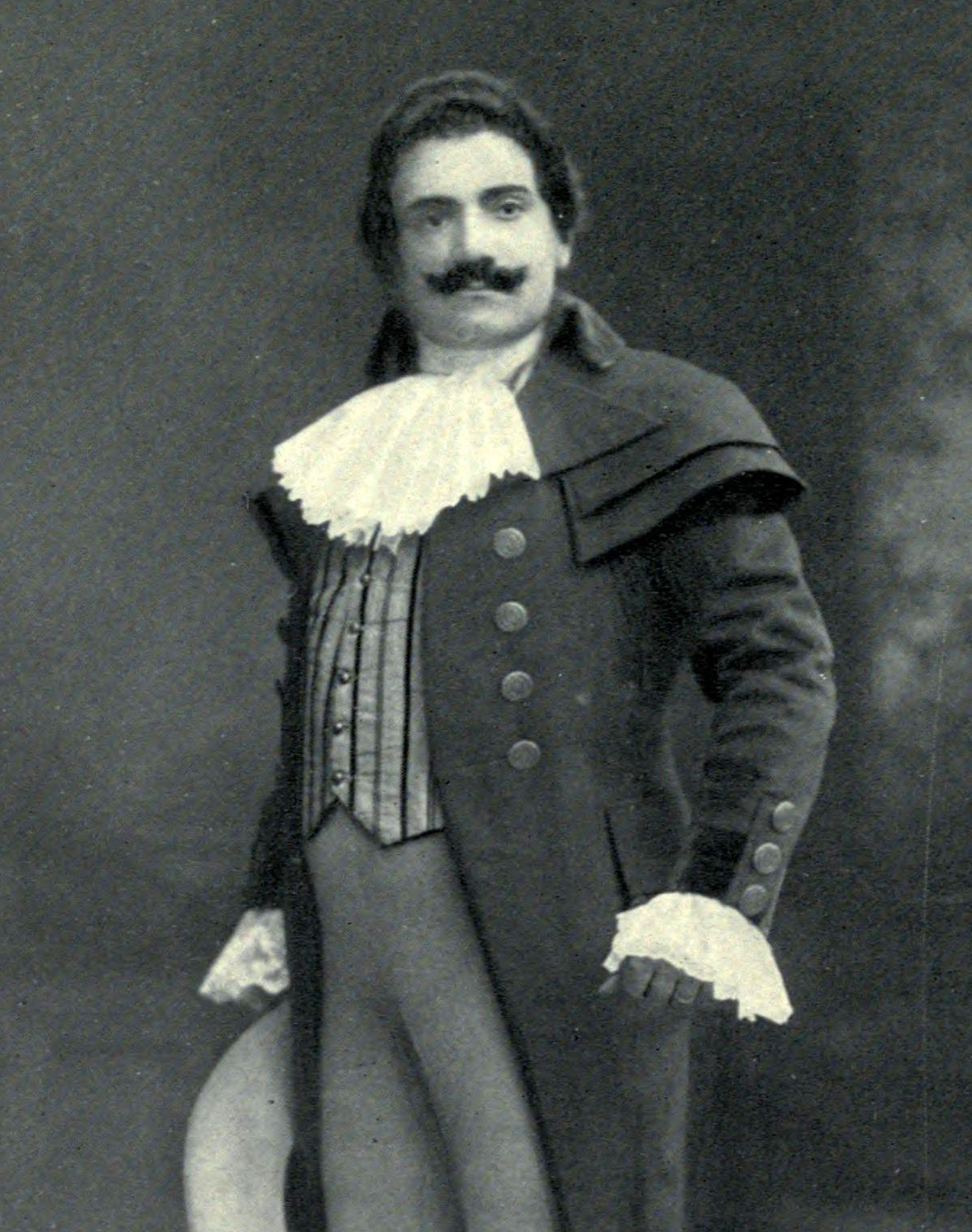

was selected for the title role; Eugenio Giraldoni, whose father had originated many Verdi

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian composer best known for his operas. He was born near Busseto to a provincial family of moderate means, receiving a musical education with the h ...

roles, became the first Scarpia. The young Enrico Caruso

Enrico Caruso (, , ; 25 February 1873 – 2 August 1921) was an Italian operatic first lyrical tenor then dramatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) ...

had hoped to create the role of Cavaradossi, but was passed over in favour of the more experienced Emilio De Marchi. The performance was to be directed by Nino Vignuzzi, with stage designs by Adolfo Hohenstein.

At the time of the premiere, Italy had experienced political and social unrest for several years. The start of the Holy Year

A jubilee is a special year of remission of sins and universal pardon. In ''Leviticus'', a Jubilee (biblical), jubilee year ( he, יובל ''yūḇāl'') is mentioned to occur every 50th year; during which slaves and prisoners would be freed, deb ...

in December 1899 attracted the religious to the city, but also brought threats from anarchists and other anticlericals. Police received warnings of an anarchist bombing of the theatre, and instructed Mugnone (who had survived a theatre bombing in Barcelona), that in an emergency he was to strike up the royal march

The (; "Royal March") is the national anthem of Spain. It is one of only four national anthems in the world – along with those of Bosnia and Herzegovina, San Marino and Kosovo – that have no official lyrics. Although it had lyrics in the p ...

.Budden, p. 198 The unrest caused the premiere to be postponed by one day, to 14 January.Ashbrook, p. 77

By 1900, the premiere of a Puccini opera was a national event. Many Roman dignitaries attended, as did Queen Margherita

Margherita of Savoy (''Margherita Maria Teresa Giovanna''; 20 November 1851 – 4 January 1926) was Queen of Italy by marriage to Umberto I.

Life

Early life

Margherita was born to Prince Ferdinand of Savoy, Duke of Genoa and Princess Elisabeth ...

, though she arrived late, after the first act.Phillips-Matz, p. 118 The Prime Minister of Italy

The Prime Minister of Italy, officially the President of the Council of Ministers ( it, link=no, Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri), is the head of government of the Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is ...

, Luigi Pelloux

Luigi Gerolamo Pelloux ( La Roche-sur-Foron, 1 March 1839 – Bordighera, 26 October 1924) was an Italian general and politician, born of parents who retained their Italian nationality when Savoy was annexed to France. He was the Prime Minister o ...

was present, with several members of his cabinet. A number of Puccini's operatic rivals were there, including Franchetti, Pietro Mascagni

Pietro Mascagni (7 December 1863 – 2 August 1945) was an Italian composer primarily known for his operas. His 1890 masterpiece ''Cavalleria rusticana'' caused one of the greatest sensations in opera history and single-handedly ushered in the ' ...

, Francesco Cilea

Francesco Cilea (; 23 July 1866 – 20 November 1950) was an Italian composer. Today he is particularly known for his operas ''L'arlesiana'' and ''Adriana Lecouvreur''.

Biography

Born in Palmi near Reggio di Calabria, Cilea gave early indicatio ...

and Ildebrando Pizzetti

Ildebrando Pizzetti (20 September 1880 – 13 February 1968) was an Italian composer of classical music, Musicology, musicologist, and Music criticism, music critic.

Biography

Pizzetti was born in Parma in 1880. He was part of the "Generation ...

. Shortly after the curtain was raised there was a disturbance in the back of the theatre, caused by latecomers attempting to enter the auditorium, and a shout of "Bring down the curtain!", at which Mugnone stopped the orchestra. A few moments later the opera began again, and proceeded without further disruption.

The performance, while not quite the triumph that Puccini had hoped for, was generally successful, with numerous encores. Much of the critical and press reaction was lukewarm, often blaming Illica's libretto. In response, Illica condemned Puccini for treating his librettists "like stagehands" and reducing the text to a shadow of its original form. Nevertheless, any public doubts about ''Tosca'' soon vanished; the premiere was followed by twenty performances, all given to packed houses.Budden, p. 199

Subsequent productions

The Milan premiere at La Scala took place under Toscanini on 17 March 1900. Darclée and Giraldoni reprised their roles; the prominent tenor Giuseppe Borgatti replaced De Marchi as Cavaradossi. The opera was a great success at La Scala, and played to full houses.Phillips-Matz, p. 120 Puccini travelled to London for the British premiere at theRoyal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Op ...

, Covent Garden, on 12 July, with Milka Ternina

Milka Ternina (born Katarina Milka Trnina, pronounced ; 19 December 1863 – 18 May 1941) was a Croatian dramatic soprano who enjoyed a high reputation in major American and European opera houses. Praised by audiences and music critics alike for ...

and Fernando De Lucia

Fernando De Lucia (11 October 1860 or 1 September 1861 – 21 February 1925) was an Italian opera tenor and singing teacher who enjoyed an international career.

De Lucia was admired in his lifetime as a striking exponent of verismo parts — ...

as the doomed lovers and Antonio Scotti as Scarpia. Puccini wrote that ''Tosca'' was "Metropolitan Opera

The Metropolitan Opera (commonly known as the Met) is an American opera company based in New York City, resident at the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, currently situated on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The company is operat ...

was on 4 February 1901, with De Lucia's replacement by Giuseppe Cremonini the only change from the London cast.Budden, p. 225 For its French premiere at the Opéra-Comique

The Opéra-Comique is a Paris opera company which was founded around 1714 by some of the popular theatres of the Parisian fairs. In 1762 the company was merged with – and for a time took the name of – its chief rival, the Comédie-Italienne ...

on 13 October 1903, the 72-year-old Sardou took charge of all the action on the stage. Puccini was delighted with the public's reception of the work in Paris, despite adverse comments from critics. The opera was subsequently premiered at venues throughout Europe, the Americas, Australia and the Far East;Greenfeld, pp. 138–139 by the outbreak of war in 1914 it had been performed in more than 50 cities worldwide.

Among the prominent early Toscas was Emmy Destinn

Emmy Destinn ( (); 26 February 1878 – 28 January 1930) was a Czech operatic soprano with a strong and soaring lyric-dramatic voice. She had a career both in Europe and at the New York Metropolitan Opera.

Biography

Destinn was born Emíl ...

, who sang the role regularly in a long-standing partnership with the tenor Enrico Caruso

Enrico Caruso (, , ; 25 February 1873 – 2 August 1921) was an Italian operatic first lyrical tenor then dramatic tenor. He sang to great acclaim at the major opera houses of Europe and the Americas, appearing in a wide variety of roles (74) ...

. Maria Jeritza

Maria Jeritza (born Marie Jedličková; 6 October 1887 – 10 July 1982) was a dramatic soprano, long associated with the Vienna State Opera (1912–1934 and 1950-1953) and the Metropolitan Opera (1921–1932 and 1951). Her rapid rise to fame, ...

, over many years at the Met and in Vienna, brought her own distinctive style to the role, and was said to be Puccini's favorite Tosca. Jeritza was the first to deliver "Vissi d'arte" from a prone position, having fallen to the stage while eluding the grasp of Scarpia. This was a great success, and Jeritza sang the aria while on the floor thereafter. Of her successors, opera enthusiasts tend to consider Maria Callas

Maria Callas . (born Sophie Cecilia Kalos; December 2, 1923 – September 16, 1977) was an American-born Greek soprano who was one of the most renowned and influential opera singers of the 20th century. Many critics praised her ''bel cant ...

as the supreme interpreter of the role, largely on the basis of her performances at the Royal Opera House in 1964, with Tito Gobbi

Tito Gobbi (24 October 19135 March 1984) was an Italian operatic baritone with an international reputation.

He made his operatic debut in Gubbio in 1935 as Count Rodolfo in Bellini's ''La sonnambula'' and quickly appeared in Italy's major opera ...

as Scarpia.Neef, pp. 462–467 This production, by Franco Zeffirelli

Gian Franco Corsi Zeffirelli (12 February 1923 – 15 June 2019), was an Italian stage and film director, producer, production designer and politician. He was one of the most significant opera and theatre directors of the post-World War II era, ...

, remained in continuous use at Covent Garden for more than 40 years until replaced in 2006 by a new staging, which premiered with Angela Gheorghiu

Angela Gheorghiu (; ; born 7 September 1965) is a Romanian soprano, especially known for her performances in the operas of Puccini and Verdi, widely recognised by critics and opera lovers as one of the greatest sopranos of all time.

Embarking h ...

. Callas had first sung Tosca at age 18 in a performance given in Greek, in the Greek National Opera

The Greek National Opera ( el, Εθνική Λυρική Σκηνή, ''Ethniki Lyriki Skini'') is the country's state lyric opera company, located in the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center at the south suburb of Athens, Kallithea. It is a ...

in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

on 27 August 1942. Tosca was also her last on-stage operatic role, in a special charity performance at the Royal Opera House on 7 May 1965.

Among non-traditional productions, Luca Ronconi

Luca Ronconi (8 March 1933 – 21 February 2015) was an Italian actor, theater director, and opera director.

Biography

Ronconi was born in Sousse, Tunisia. After growing up in Tunisia, where his mother was a school teacher, Ronconi graduated ...

, in 1996 at La Scala, used distorted and fractured scenery to represent the twists of fate reflected in the plot. Jonathan Miller

Sir Jonathan Wolfe Miller CBE (21 July 1934 – 27 November 2019) was an English theatre and opera director, actor, author, television presenter, humourist and physician. After training in medicine and specialising in neurology in the late 19 ...

, in a 1986 production for the 49th ''Maggio Musicale Fiorentino

The Maggio Musicale Fiorentino (English: Florence Musical May) is an annual Italian arts festival in Florence, including a notable opera festival, under the auspices of the Opera di Firenze. The festival occurs between late April into June annual ...

'', transferred the action to Nazi-occupied Rome in 1944, with Scarpia as head of the fascist police. In production on the Lake Stage at the Bregenz Festival

Bregenzer Festspiele (; Bregenz Festival) is a performing arts festival which is held every July and August in Bregenz in Vorarlberg (Austria).

It features a large floating stage which is situated on Lake Constance.

History

The Festival becam ...

in 2007 the act 1 set, designed by Johannes Leiacker, was dominated by a huge Orwellian

"Orwellian" is an adjective describing a situation, idea, or societal condition that George Orwell identified as being destructive to the welfare of a free and open society. It denotes an attitude and a brutal policy of draconian control by pro ...

"Big Brother" eye. The iris opens and closes to reveal surreal

Surreal may refer to:

*Anything related to or characteristic of Surrealism, a movement in philosophy and art

* "Surreal" (song), a 2000 song by Ayumi Hamasaki

* ''Surreal'' (album), an album by Man Raze

*Surreal humour, a common aspect of humor

...

scenes beyond the action. This production updates the story to a modern Mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of d ...

scenario, with special effects "worthy of a Bond

Bond or bonds may refer to:

Common meanings

* Bond (finance), a type of debt security

* Bail bond, a commercial third-party guarantor of surety bonds in the United States

* Chemical bond, the attraction of atoms, ions or molecules to form chemica ...

film".

In 1992 a television version of the opera was filmed at the locations prescribed by Puccini, at the times of day at which each act takes place. Featuring

In 1992 a television version of the opera was filmed at the locations prescribed by Puccini, at the times of day at which each act takes place. Featuring Catherine Malfitano

Catherine Malfitano (born April 18, 1948) is an American operatic soprano and opera director. Malfitano was born in New York City, the daughter of a ballet dancer mother, Maria Maslova, and a violinist father, Joseph Malfitano. She attended the ...

, Plácido Domingo

José Plácido Domingo Embil (born 21 January 1941) is a Spanish opera singer, conductor, and arts administrator. He has recorded over a hundred complete operas and is well known for his versatility, regularly performing in Italian, French, ...

and Ruggero Raimondi

Ruggero Raimondi (born 3 October 1941) is an Italian bass-baritone opera singer who has also appeared in motion pictures.

Life and career

Early training and career

Ruggero Raimondi was born in Bologna, Italy, during World War II. His voice matu ...

, the performance was broadcast live throughout Europe.

Luciano Pavarotti

Luciano Pavarotti (, , ; 12 October 19356 September 2007) was an Italian operatic tenor who during the late part of his career crossed over into popular music, eventually becoming one of the most acclaimed tenors of all time. He made numerou ...

, who sang Cavaradossi from the late 1970s, appeared in a special performance in Rome, with Plácido Domingo as conductor, on 14 January 2000, to celebrate the opera's centenary. Pavarotti's last stage performance was as Cavaradossi at the Met, on 13 March 2004.

Early Cavaradossis played the part as if the painter believed that he was reprieved, and would survive the "mock" execution. Beniamino Gigli

Beniamino Gigli ( , ; 20 March 1890 – 30 November 1957) was an Italian opera singer (lyric tenor). He is widely regarded as one of the greatest tenors of his generation.

Early life

Gigli was born in Recanati, in the Marche, the son of a shoem ...

, who performed the role many times in his forty-year operatic career, was one of the first to assume that the painter knows, or strongly suspects, that he will be shot. Gigli wrote in his autobiography: "he is certain that these are their last moments together on earth, and that he is about to die".Nicassio, pp. 241–242 Domingo, the dominant Cavaradossi of the 1970s and 1980s, concurred, stating in a 1985 interview that he had long played the part that way. Gobbi, who in his later years often directed the opera, commented, "Unlike Floria, Cavaradossi knows that Scarpia never yields, though he pretends to believe in order to delay the pain for Tosca."

Critical reception

The enduring popularity of ''Tosca'' has not been matched by consistent critical enthusiasm. After the premiere, Ippolito Valetta of ''Nuova antologia'' wrote, "The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' is an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom and currently the oldest such journal still being published in the country.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainze ...

'', Puccini's score was admired for its sincerity and "strength of utterance." After the 1903 Paris opening, the composer Paul Dukas

Paul Abraham Dukas ( or ; 1 October 1865 – 17 May 1935) was a French composer, critic, scholar and teacher. A studious man of retiring personality, he was intensely self-critical, having abandoned and destroyed many of his compositions. His b ...

thought the work lacked cohesion and style, while Gabriel Fauré

Gabriel Urbain Fauré (; 12 May 1845 – 4 November 1924) was a French composer, organist, pianist and teacher. He was one of the foremost French composers of his generation, and his musical style influenced many 20th-century composers ...

was offended by "disconcerting vulgarities". In the 1950s, the young musicologist Joseph Kerman

Joseph Wilfred Kerman (3 April 1924 – 17 March 2014) was an American musicologist and music critic. Among the leading musicologists of his generation, his 1985 book ''Contemplating Music: Challenges to Musicology'' (published in the UK as ''Mu ...

described ''Tosca'' as a "shabby little shocker."; in response the conductor Thomas Beecham

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet, Order of the Companions of Honour, CH (29 April 18798 March 1961) was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, London Philharmonic and the Roya ...

remarked that anything Kerman says about Puccini "can safely be ignored". Writing half a century after the premiere, the veteran critic Ernest Newman

Ernest Newman (30 November 1868 – 7 July 1959) was an English music critic and musicologist. ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' describes him as "the most celebrated British music critic in the first half of the 20th century." His ...

, while acknowledging the "enormously difficult business of boiling ardou'splay down for operatic purposes", thought that the subtleties of Sardou's original plot are handled "very lamely", so that "much of what happens, and why, is unintelligible to the spectator". Overall, however, Newman delivered a more positive judgement: " uccini'soperas are to some extent a mere bundle of tricks, but no one else has performed the same tricks nearly as well". Opera scholar Julian Budden

Julian Medforth Budden (9 April 1924 in Hoylake, Wirral – 28 February 2007 in Florence, Italy) was a British opera scholar, radio producer and broadcaster. He is particularly known for his three volumes on the operas of Giuseppe Verdi (publishe ...

remarks on Puccini's "inept handling of the political element", but still hails the work as "a triumph of pure theatre". Music critic Charles Osborne ascribes ''Toscas immense popularity with audiences to the taut effectiveness of its melodramatic plot, the opportunities given to its three leading characters to shine vocally and dramatically, and the presence of two great arias in "Vissi d'arte" and "E lucevan le stelle".Osborne, p. 143 The work remains popular today: according to Operabase

Operabase is an online database of opera performances, opera houses and companies, and performers themselves as well as their agents. Found at operabase.com, it was created in 1996 by English software engineer and opera lover Mike Gibb.Edward Sc ...

, it ranks as fifth in the world with 540 performances given in the five seasons 2009–10 to 2013–14.

Music

General style

By the end of the 19th century the classic form of opera structure, in whicharia

In music, an aria (Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompanime ...

s, duet

A duet is a musical composition for two performers in which the performers have equal importance to the piece, often a composition involving two singers or two pianists. It differs from a harmony, as the performers take turns performing a solo ...

s and other set-piece vocal numbers are interspersed with passages of recitative

Recitative (, also known by its Italian name "''recitativo''" ()) is a style of delivery (much used in operas, oratorios, and cantatas) in which a singer is allowed to adopt the rhythms and delivery of ordinary speech. Recitative does not repea ...

or dialogue, had been largely abandoned, even in Italy. Operas were "through-composed

In music theory of musical form, through-composed music is a continuous, non- sectional, and non- repetitive piece of music. The term is typically used to describe songs, but can also apply to instrumental music.

While most musical forms such as t ...

", with a continuous stream of music which in some cases eliminated all identifiable set-pieces. In what critic Edward Greenfield

Edward Harry Greenfield OBE (3 July 1928 – 1 July 2015) was an English music critic and broadcaster.

Early life

Edward Greenfield was born in Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex. His father, Percy Greenfield, was a manager in a labour exchange, while his ...

calls the "Grand Tune" concept, Puccini retains a limited number of set-pieces, distinguished from their musical surroundings by their memorable melodies. Even in the passages linking these "Grand Tunes", Puccini maintains a strong degree of lyricism and only rarely resorts to recitative.

Budden describes ''Tosca'' as the most Wagnerian

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

of Puccini's scores, in its use of musical leitmotif

A leitmotif or leitmotiv () is a "short, recurring musical phrase" associated with a particular person, place, or idea. It is closely related to the musical concepts of ''idée fixe'' or ''motto-theme''. The spelling ''leitmotif'' is an anglici ...

s. Unlike Wagner, Puccini does not develop or modify his motifs, nor weave them into the music symphonically, but uses them to refer to characters, objects and ideas, and as reminders within the narrative.Fisher, pp. 27–28 The most potent of these motifs is the sequence of three very loud and strident chords which open the opera and which represent the evil character of Scarpia—or perhaps, Charles Osborne proposes, the violent atmosphere that pervades the entire opera.Osborne, pp. 137–138 Budden has suggested that Scarpia's tyranny, lechery and lust form "the dynamic engine that ignites the drama". Other motifs identify Tosca herself, the love of Tosca and Cavaradossi, the fugitive Angelotti, the semi-comical character of the sacristan in act 1 and the theme of torture in act 2.Fisher, pp. 33–35

Act 1

The opera begins without any prelude; the opening chords of the Scarpia motif lead immediately to the agitated appearance of Angelotti and the enunciation of the "fugitive" motif. The sacristan's entry, accompanied by his sprightlybuffo

''Opera buffa'' (; "comic opera", plural: ''opere buffe'') is a genre of opera. It was first used as an informal description of Italian comic operas variously classified by their authors as ''commedia in musica'', ''commedia per musica'', ''dramm ...

theme, lifts the mood, as does the generally light-hearted colloquy with Cavaradossi which follows after the latter's entrance. This leads to the first of the "Grand Tunes", Cavaradossi's "Recondita armonia

"Recondita armonia" is the first romanza in the opera ''Tosca'' (1900) by Giacomo Puccini. It is sung by the painter Mario Cavaradossi when comparing his love, Tosca, to a portrait of Mary Magdalene that he is painting.B flat, accompanied by the sacristan's grumbling

The third act's tranquil beginning provides a brief respite from the drama. An introductory 16-bar theme for the

The third act's tranquil beginning provides a brief respite from the drama. An introductory 16-bar theme for the

carpia/nowiki>); formerly she stated, "Ma il sozzo sbirro lo pagherà" ("But the filthy cop will pay for it."). Other changes are in the music; when Tosca demands the price for Cavaradossi's freedom ("Il prezzo!"), her music is changed to eliminate an octave leap, allowing her more opportunity to express her contempt and loathing of Scarpia in a passage which is now near the middle of the soprano vocal range. A remnant of a "Latin Hymn" sung by Tosca and Cavaradossi in act 3 survived into the first published score and libretto, but is not in later versions. According to Ashbrook, the most surprising change is where, after Tosca discovers the truth about the "mock" execution and exclaims "Finire così? Finire così?" ("To end like this? To end like this?"), she was to sing a five-bar fragment to the melody of "E lucevan le stelle". Ashbrook applauds Puccini for deleting the section from a point in the work where delay is almost unendurable as events rush to their conclusion, but points out that the orchestra's recalling "E lucevan le stelle" in the final notes would seem less incongruous if it was meant to underscore Tosca's and Cavaradossi's love for each other, rather than being simply a melody which Tosca never hears.Ashbrook, p. 93

"How we made: Franco Zeffirelli and John Tooley on ''Tosca'' (1964)"

''

Libretto

counter-melody

In music, a counter-melody (often countermelody) is a sequence of notes, perceived as a melody, written to be played simultaneously with a more prominent lead melody. In other words, it is a secondary melody played in counterpoint with the prima ...

. The domination, in that aria, of themes which will be repeated in the love duet make it clear that though the painting may incorporate the Marchesa's features, Tosca is the ultimate inspiration of his work. Cavaradossi's dialogue with Angelotti is interrupted by Tosca's arrival, signalled by her motif which incorporates, in Newman's words, "the feline, caressing cadence so characteristic of her." Though Tosca enters violently and suspiciously, the music paints her devotion and serenity. According to Budden, there is no contradiction: Tosca's jealousy is largely a matter of habit, which her lover does not take too seriously.

After Tosca's "Non la sospiri" and the subsequent argument inspired by her jealousy, the sensuous character of the love duet "Qual'occhio" provides what opera writer Burton Fisher describes as "an almost erotic lyricism that has been called pornophony".Fisher, p. 20 The brief scene in which the sacristan returns with the choristers to celebrate Napoleon's supposed defeat provides almost the last carefree moments in the opera; after the entrance of Scarpia to his menacing theme, the mood becomes sombre, then steadily darker. As the police chief interrogates the sacristan, the "fugitive" motif recurs three more times, each time more emphatically, signalling Scarpia's success in his investigation. In Scarpia's exchanges with Tosca the sound of tolling bells, interwoven with the orchestra, creates an almost religious atmosphere, for which Puccini draws on music from his then unpublished Mass of 1880. The final scene in the act is a juxtaposition of the sacred and the profane, as Scarpia's lustful reverie is sung alongside the swelling Te Deum chorus. He joins with the chorus in the final statement "Te aeternum Patrem omnis terra veneratur" ("Everlasting Father, all the earth worships thee"), before the act ends with a thunderous restatement of the Scarpia motif.

Act 2

In the second act of ''Tosca'', according to Newman, Puccini rises to his greatest height as a master of the musical macabre. The act begins quietly, with Scarpia musing on the forthcoming downfall of Angelotti and Cavaradossi, while in the background agavotte

The gavotte (also gavot, gavote, or gavotta) is a French dance, taking its name from a folk dance of the Gavot, the people of the Pays de Gap region of Dauphiné in the southeast of France, where the dance originated, according to one source. Ac ...

is played in a distant quarter of the Farnese Palace. For this music Puccini adapted a fifteen-year-old student exercise by his late brother, Michele, stating that in this way his brother could live again through him.Burton et al., pp. 130–131 In the dialogue with Spoletta, the "torture" motif—an "ideogram of suffering", according to Budden—is heard for the first time as a foretaste of what is to come. As Cavaradossi is brought in for interrogation, Tosca's voice is heard with the offstage chorus singing a cantata, " tssuave strains contrast ngdramatically with the increasing tension and ever-darkening colour of the stage action". The cantata is most likely the ''Cantata a Giove'', in the literature referred to as a lost work of Puccini's from 1897.

Osborne describes the scenes that follow—Cavaradossi's interrogation, his torture, Scarpia's sadistic tormenting of Tosca—as Puccini's musical equivalent of ''grand guignol

''Le Théâtre du Grand-Guignol'' (: "The Theatre of the Great Puppet")—known as the Grand Guignol–was a theatre in the Pigalle district of Paris (7, cité Chaptal). From its opening in 1897 until its closing in 1962, it specialised in natura ...

'' to which Cavaradossi's brief "Vittoria! Vittoria!" on the news of Napoleon's victory gives only partial relief.Osborne, pp. 140–143 Scarpia's aria "Già, mi dicon venal" ("Yes, they say I am venal") is closely followed by Tosca's "Vissi d'arte

"Vissi d'arte" is a soprano aria from act 2 of the opera '' Tosca'' by Giacomo Puccini. It is sung by Floria Tosca as she thinks of her fate, how the life of her beloved, Mario Cavaradossi, is at the mercy of Baron Scarpia and why God has seeming ...

". A lyrical andante

Andante may refer to:

Arts

* Andante (tempo), a moderately slow musical tempo

* Andante (manga), ''Andante'' (manga), a shōjo manga by Miho Obana

* Andante (song), "Andante" (song), a song by Hitomi Yaida

* "Andante, Andante", a 1980 song by A ...

based on Tosca's act 1 motif, this is perhaps the opera's best-known aria, yet was regarded by Puccini as a mistake; he considered eliminating it since it held up the action. Fisher calls it "a Job

Work or labor (or labour in British English) is intentional activity people perform to support the needs and wants of themselves, others, or a wider community. In the context of economics, work can be viewed as the human activity that contr ...

-like prayer questioning God for punishing a woman who has lived unselfishly and righteously". In the act's finale, Newman likens the orchestral turmoil which follows Tosca's stabbing of Scarpia to the sudden outburst after the slow movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony

The Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, is a choral symphony, the final complete symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven, composed between 1822 and 1824. It was first performed in Vienna on 7 May 1824. The symphony is regarded by many critics and musi ...

. After Tosca's contemptuous "E avanti a lui tremava tutta Roma!" ("All Rome trembled before him"), sung on a middle C

C or Do is the first note and semitone of the C major scale, the third note of the A minor scale (the relative minor of C major), and the fourth note (G, A, B, C) of the Guidonian hand, commonly pitched around 261.63 Hz. The actual frequen ...

monotone (sometimes spoken), the music gradually fades, ending what Newman calls "the most impressively macabre scene in all opera." The final notes in the act are those of the Scarpia motif, softly, in a minor key.

Act 3

The third act's tranquil beginning provides a brief respite from the drama. An introductory 16-bar theme for the

The third act's tranquil beginning provides a brief respite from the drama. An introductory 16-bar theme for the horns Horns or The Horns may refer to:

* Plural of Horn (instrument), a group of musical instruments all with a horn-shaped bells

* The Horns (Colorado), a summit on Cheyenne Mountain

* ''Horns'' (novel), a dark fantasy novel written in 2010 by Joe Hill ...

will later be sung by Cavaradossi and Tosca in their final duet. The orchestral prelude which follows portrays the Roman dawn; the pastoral aura is accentuated by the shepherd boy's song, and the sounds of sheep bells and church bells, the authenticity of the latter validated by Puccini's early morning visits to Rome. Themes reminiscent of Scarpia, Tosca and Cavaradossi emerge in the music, which changes tone as the drama resumes with Cavaradossi's entrance, to an orchestral statement of what becomes the melody of his aria "E lucevan le stelle

"" ("And the stars were shining") is a romantic aria from the third act of Giacomo Puccini's opera ''Tosca'' from 1900, composed to an Italian libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa. It is sung in act 3 by Mario Cavaradossi (tenor), a pain ...

".

This is a farewell to love and life, "an anguished lament and grief built around the words 'muoio disperato' (I die in despair)". Puccini insisted on the inclusion of these words, and later stated that admirers of the aria had treble cause to be grateful to him: for composing the music, for having the lyrics written, and "for declining expert advice to throw the result in the waste-paper basket". The lovers' final duet "Amaro sol per te", which concludes with the act's opening horn music, did not equate with Ricordi

Ricordi may refer to:

People

*Giovanni Ricordi (1785–1853), Italian violinist and publishing company founder

* Giulio Ricordi (1840–1912), Italian publisher and musician

Music

*Casa Ricordi, an Italian music publishing company established i ...

's idea of a transcendental love duet which would be a fitting climax to the opera. Puccini justified his musical treatment by citing Tosca's preoccupation with teaching Cavaradossi to feign death.

In the execution scene which follows, a theme emerges, the incessant repetition of which reminded Newman of the Transformation Music which separates the two parts of act 1 in Wagner's ''Parsifal

''Parsifal'' ( WWV 111) is an opera or a music drama in three acts by the German composer Richard Wagner and his last composition. Wagner's own libretto for the work is loosely based on the 13th-century Middle High German epic poem ''Parzival'' ...

''. In the final bars, as Tosca evades Spoletta and leaps to her death, the theme of "E lucevan le stelle" is played ''tutta forze'' (as loudly as possible). This choice of ending has been strongly criticised by analysts, mainly because of its specific association with Cavaradossi rather than Tosca. Kerman

Kerman ( fa, كرمان, Kermân ; also romanization of Persian, romanized as Kermun and Karmana), known in ancient times as the satrapy of Carmania, is the capital city of Kerman Province, Iran. At the 2011 census, its population was 821,394, in ...

mocked the final music, "Tosca leaps, and the orchestra screams the first thing that comes into its head."Nicassio, pp. 253–254 Budden, however, argues that it is entirely logical to end this dark opera on its blackest theme.Budden, p. 222 According to historian and former opera singer Susan Vandiver Nicassio: "The conflict between the verbal and the musical clues gives the end of the opera a twist of controversy that, barring some unexpected discovery among Puccini's papers, can never truly be resolved."

Instrumentation

''Tosca'' is scored for threeflutes

The flute is a family of classical music instrument in the woodwind group. Like all woodwinds, flutes are aerophones, meaning they make sound by vibrating a column of air. However, unlike woodwind instruments with reeds, a flute is a reedless ...

(the second and third doubling piccolo

The piccolo ( ; Italian for 'small') is a half-size flute and a member of the woodwind family of musical instruments. Sometimes referred to as a "baby flute" the modern piccolo has similar fingerings as the standard transverse flute, but the so ...

); two oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

A ...

s; one English horn; two clarinet

The clarinet is a musical instrument in the woodwind family. The instrument has a nearly cylindrical bore and a flared bell, and uses a single reed to produce sound.

Clarinets comprise a family of instruments of differing sizes and pitches ...

s in B-flat; one bass clarinet

The bass clarinet is a musical instrument of the clarinet family. Like the more common soprano B clarinet, it is usually pitched in B (meaning it is a transposing instrument on which a written C sounds as B), but it plays notes an octave bel ...

in B-flat; two bassoon

The bassoon is a woodwind instrument in the double reed family, which plays in the tenor and bass ranges. It is composed of six pieces, and is usually made of wood. It is known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, versatility, and virtuo ...

s; one contrabassoon

The contrabassoon, also known as the double bassoon, is a larger version of the bassoon, sounding an octave lower. Its technique is similar to its smaller cousin, with a few notable differences.

Differences from the bassoon

The reed is consi ...

; four French horn