Theravada Buddhist Spiritual Teachers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

. ''Nyanaponika _

Nyanaponika_Thera_or_Nyanaponika_Mahathera_(July_21,_1901_–_19_October_1994)_was_a_German-born_Theravada_Buddhist_monk_and_scholar_who,_after__ordaining_in__Sri_Lanka,_later_became_the_co-founder_of_the_Buddhist_Publication_Society_and_auth_...

,_The_Heart_of_Buddhist_meditation,_Buddhist_publication_Society,_2005,_p._40.

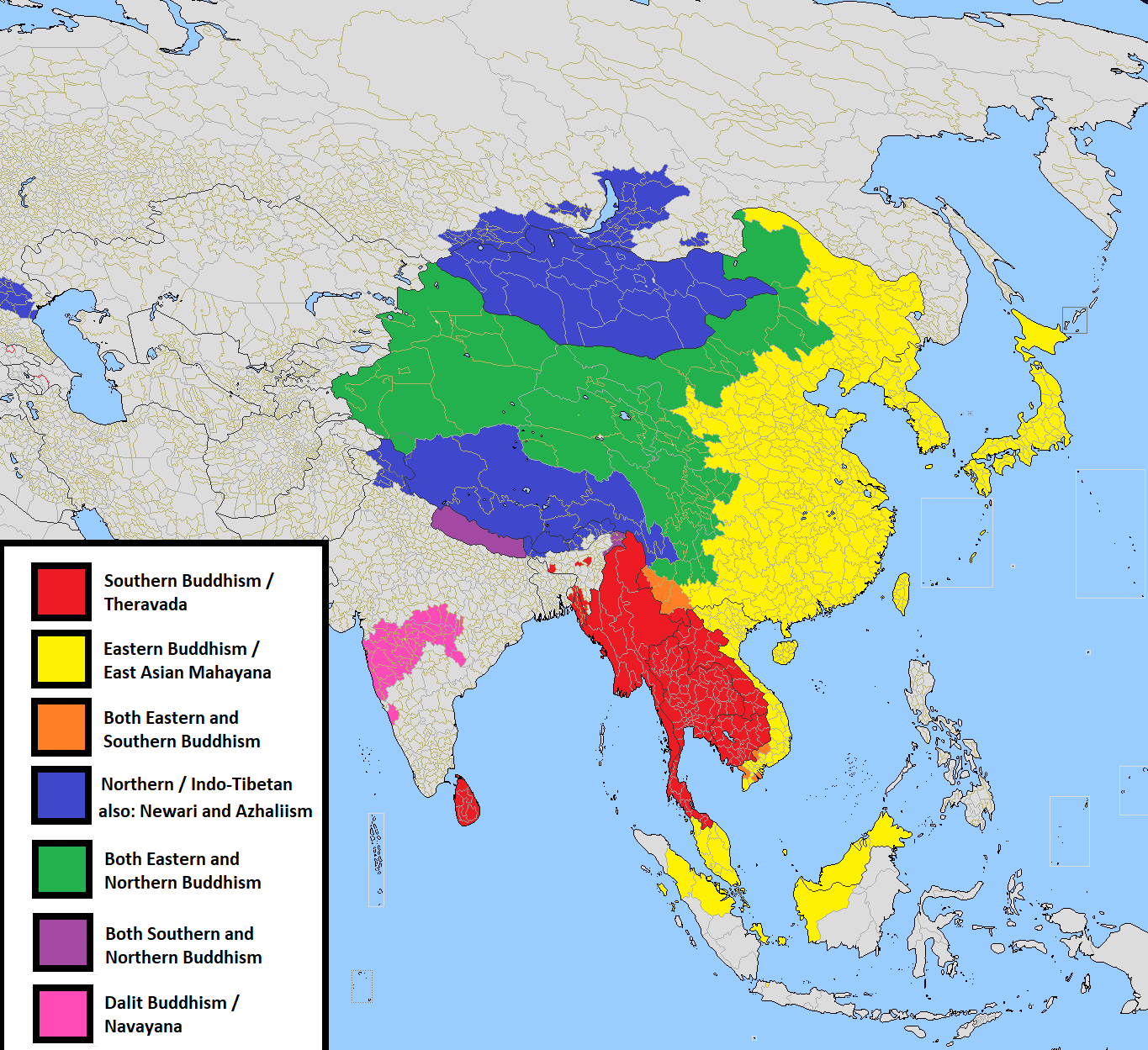

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of

The Theravāda school descends from the Vibhajjavāda, a division within the Sthāvira nikāya, one of the two major orders that arose after the first schism in the Indian Buddhist community.Cousins, Lance (2001). '

The Theravāda school descends from the Vibhajjavāda, a division within the Sthāvira nikāya, one of the two major orders that arose after the first schism in the Indian Buddhist community.Cousins, Lance (2001). '

On the Vibhajjavādins"

'', Buddhist Studies Review 18 (2), 131–182. Theravāda sources trace their tradition to the Third Buddhist council when elder

Over time, two other sects split off from the Mahāvihāra tradition, the Abhayagiri and

Over time, two other sects split off from the Mahāvihāra tradition, the Abhayagiri and

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Theravāda Buddhists came into direct contact with western ideologies, religions and modern science. The various responses to this encounter have been called "

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Theravāda Buddhists came into direct contact with western ideologies, religions and modern science. The various responses to this encounter have been called " The 20th century also saw the growth of "forest traditions" which focused on forest living and strict monastic discipline. The main forest movements of this era are the Sri Lankan Forest Tradition and the

The 20th century also saw the growth of "forest traditions" which focused on forest living and strict monastic discipline. The main forest movements of this era are the Sri Lankan Forest Tradition and the  The modern era also saw the spread of Theravāda Buddhism around the world and the revival of the religion in places where it remains a minority faith. Some of the major events of the spread of modern Theravāda include:

*The 20th-century Nepalese Theravāda movement which introduced Theravāda Buddhism to

The modern era also saw the spread of Theravāda Buddhism around the world and the revival of the religion in places where it remains a minority faith. Some of the major events of the spread of modern Theravāda include:

*The 20th-century Nepalese Theravāda movement which introduced Theravāda Buddhism to

There are numerous Theravāda works which are important for the tradition even though they are not part of the Tipiṭaka. Perhaps the most important texts apart from the Tipiṭaka are the works of the influential scholar

There are numerous Theravāda works which are important for the tradition even though they are not part of the Tipiṭaka. Perhaps the most important texts apart from the Tipiṭaka are the works of the influential scholar

Theravāda scholastics developed a systematic exposition of the Buddhist doctrine called the Abhidhamma. In the Pāli Nikayas, the Buddha teaches through an analytical method in which experience is explained using various conceptual groupings of physical and mental processes, which are called "dhammas". Examples of lists of dhammas taught by the Buddha include the twelve sense 'spheres' or ayatanas, the

Theravāda scholastics developed a systematic exposition of the Buddhist doctrine called the Abhidhamma. In the Pāli Nikayas, the Buddha teaches through an analytical method in which experience is explained using various conceptual groupings of physical and mental processes, which are called "dhammas". Examples of lists of dhammas taught by the Buddha include the twelve sense 'spheres' or ayatanas, the

The Dhamma Theory Philosophical Cornerstone of the Abhidhamma

'', Buddhist Publication Society Kandy, Sri Lanka. "Dhamma" has been translated as "factors" (Collett Cox), "psychic characteristics" (Bronkhorst), "psycho-physical events" (Noa Ronkin) and "phenomena" (

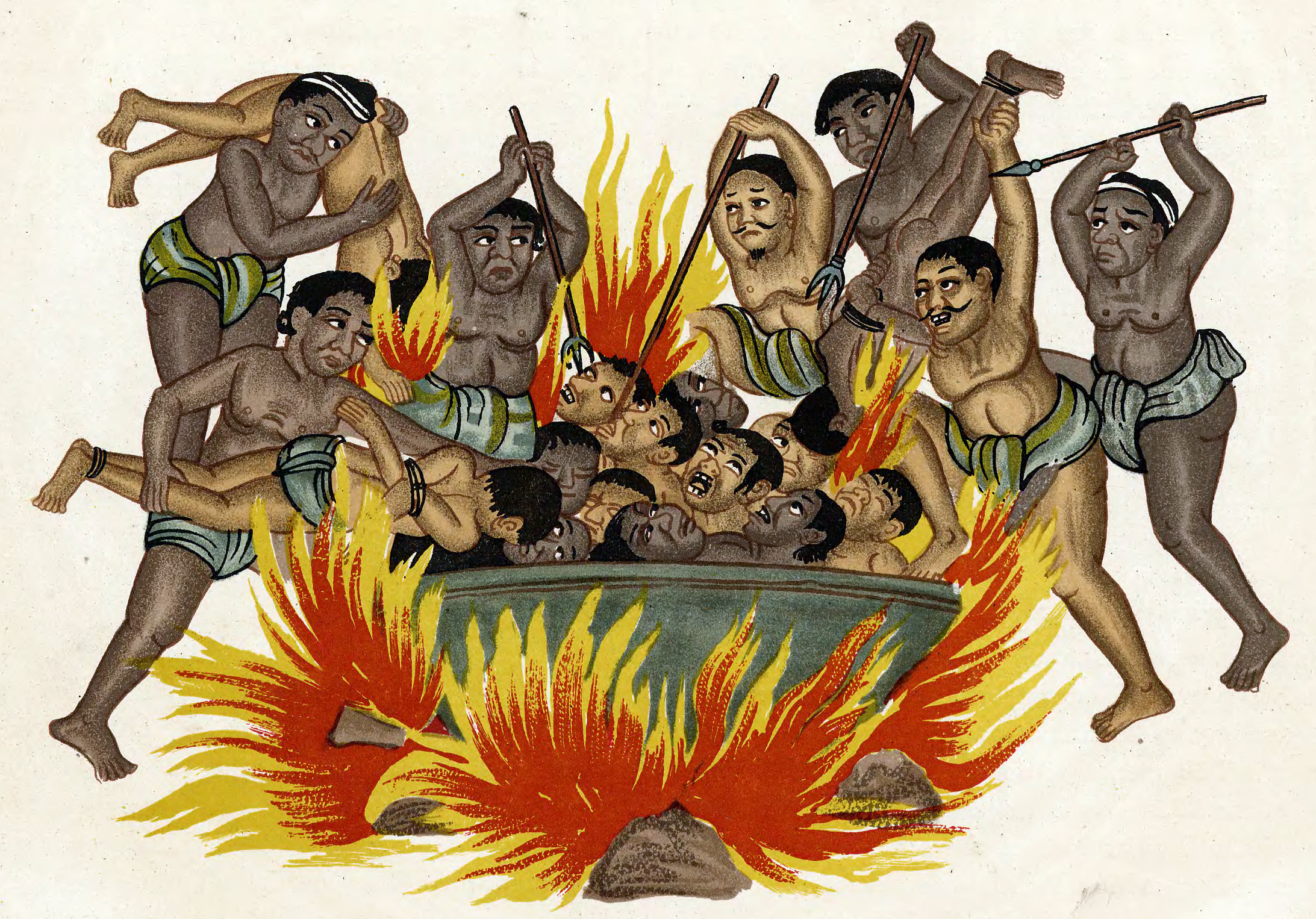

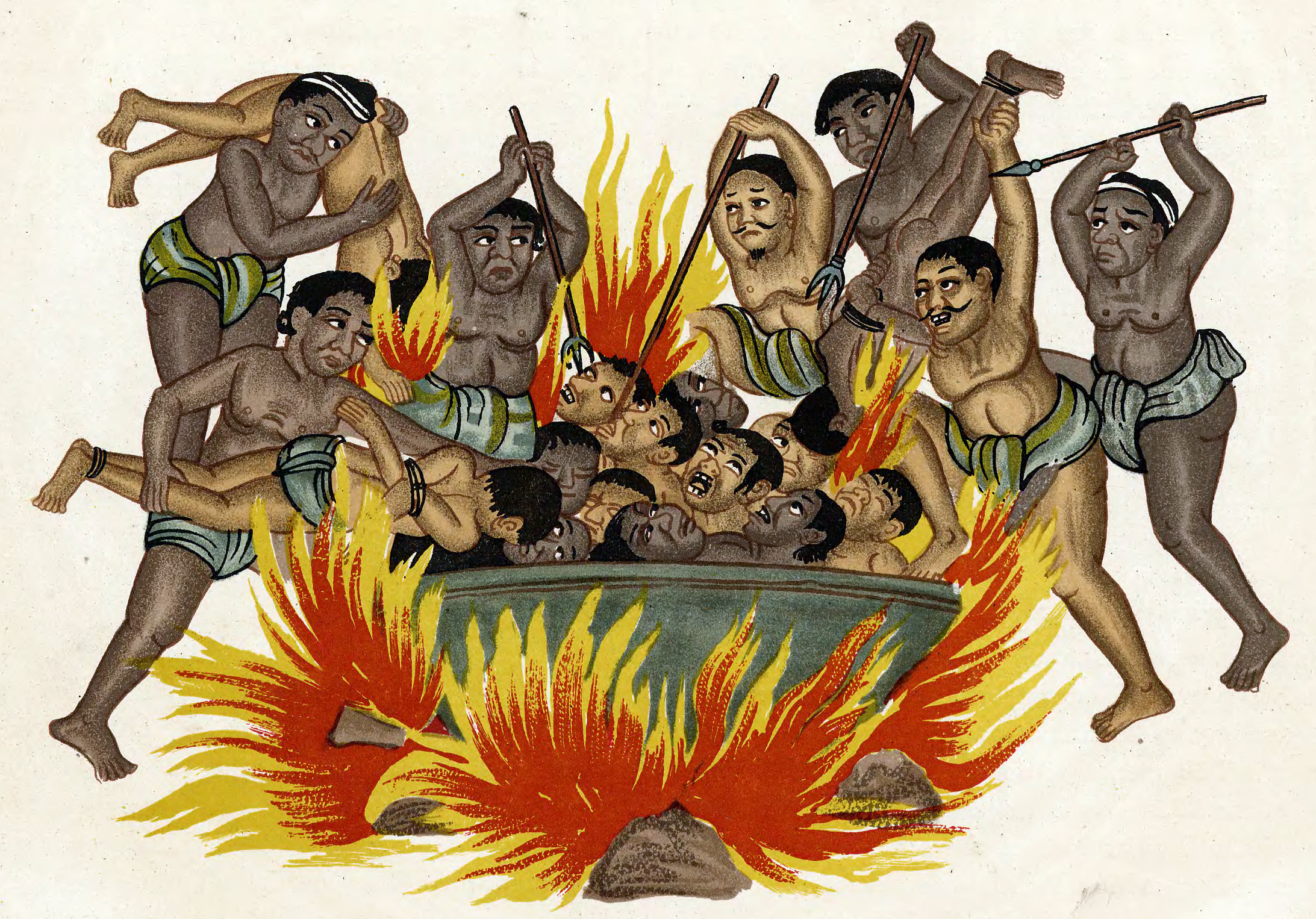

The Pāli Tipiṭaka outlines a hierarchical cosmological system with various planes existence (''bhava'') into which sentient beings may be reborn depending on their past actions. Good actions lead one to the higher realms, bad actions lead to the lower realms. However, even for the gods (''devas'') in the higher realms like

The Pāli Tipiṭaka outlines a hierarchical cosmological system with various planes existence (''bhava'') into which sentient beings may be reborn depending on their past actions. Good actions lead one to the higher realms, bad actions lead to the lower realms. However, even for the gods (''devas'') in the higher realms like

The Four Planes of Existence in Theravada Buddhism.

'' The Wheel Publication No. 462. Buddhist Publication Society.Gethin, Rupert. ''Cosmology and Meditation: From the Aggañña-Sutta to the Mahāyāna'', in "History of Religions" Vol. 36, No. 3 (Feb. 1997), pp. 183-217. The University of Chicago. *''Arūpa-bhava'', the formless or incorporeal plane. These are associated with the four formless meditations, that is: infinite space, infinite consciousness, infinite nothingness and neither perception nor non-perception. Beings in these realms live extremely long lives (thousands of kappas). *''Kāma-bhava'', the plane of desires. This includes numerous realms of existence such as: various

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, ''Into the Stream A Study Guide on the First Stage of Awakening''

# '' Once-Returners'': Those who have destroyed the first three fetters and have weakened the fetters of desire and ill-will; # '' Non-Returners'': Those who have destroyed the five lower fetters, which bind beings to the world of the senses; # '' Regarding the question of how a sentient being becomes a Buddha, the Theravāda school also includes a presentation of this path. Indeed, according to

Regarding the question of how a sentient being becomes a Buddha, the Theravāda school also includes a presentation of this path. Indeed, according to

Mahāyāna Sūtras and Opening of the Bodhisattva Path

'', Paper presented at the XVIII the IABS Congress, Toronto 2017, Updated 2019. Dhammapala's ''

The orthodox standpoints of Theravāda in comparison to other

The orthodox standpoints of Theravāda in comparison to other

Rebirth and the in-between state in early Buddhism.

'' Some Theravāda scholars (such as

Meditation (Pāli: ''Bhāvanā,'' literally "causing to become" or cultivation) means the positive cultivation of one's mind.

Meditation (Pāli: ''Bhāvanā,'' literally "causing to become" or cultivation) means the positive cultivation of one's mind.

Thai_Forest_Tradition_

The_Kammaṭṭhāna_Forest_Tradition_of_Thailand_(from__pi,_kammaṭṭhāna__meaning_Kammaṭṭhāna,_"place_of_work"),_commonly_known_in_the_West_as_the_Thai_Forest_Tradition,_is_a_Parampara,_lineage_of_Theravada_Buddhist_monasticism.

The_...

,_the_esoteric_''Tantric_Theravada.html" ;"title="Vipassana movement">Burmese Vipassana tradition, the Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

's oldest existing school. The school's adherents, termed Theravādins, have preserved their version of Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

's teaching or '' Buddha Dhamma'' in the Pāli Canon

The Pāli Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

During th ...

for over two millennia.

The Pāli Canon is the most complete Buddhist canon surviving in a classical Indian language, Pāli

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or ''Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhism ...

, which serves as the school's sacred language

A sacred language, holy language or liturgical language is any language that is cultivated and used primarily in church service or for other religious reasons by people who speak another, primary language in their daily lives.

Concept

A sacre ...

and ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

''.Crosby, Kate (2013), ''Theravada Buddhism: Continuity, Diversity, and Identity'', p. 2. In contrast to ''Mahāyāna

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhism, Buddhist traditions, Buddhist texts#Mahāyāna texts, texts, Buddhist philosophy, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BC ...

'' and ''Vajrayāna

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

'', Theravāda tends to be conservative in matters of doctrine (''pariyatti

''Pariyatti'' is a Pāli term referring to the study of Buddhism as contained within the ''suttas'' of the Pāli canon. It is related and contrasted with ''patipatti'' which means to put the theory into practice and ''pativedha'' which means pene ...

'') and monastic discipline (''vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon ('' Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinaya traditions remai ...

''). One element of this conservatism is the fact that Theravāda rejects the authenticity of the Mahayana sutras

The Mahāyāna sūtras are a broad genre of Buddhist scriptures (''sūtra'') that are accepted as canonical and as ''buddhavacana'' ("Buddha word") in Mahāyāna Buddhism. They are largely preserved in the Chinese Buddhist canon, the Tibetan B ...

(which appeared c. 1st century BCE onwards).

Modern Theravāda derives from the Mahāvihāra order, a Sri Lankan branch of the Vibhajjavāda tradition, which is, in turn, a sect of the Indian Sthavira Nikaya. This tradition began to establish itself in Sri Lanka from the 3rd century BCE onwards. It was in Sri Lanka that the Pāli Canon

The Pāli Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

During th ...

was written down and the school's commentary

Commentary or commentaries may refer to:

Publications

* ''Commentary'' (magazine), a U.S. public affairs journal, founded in 1945 and formerly published by the American Jewish Committee

* Caesar's Commentaries (disambiguation), a number of works ...

literature developed. From Sri Lanka, the Theravāda Mahāvihāra tradition subsequently spread to the rest of Southeast Asia. It is the official religion of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

and Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailand t ...

, and the dominant religion in Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist ...

and Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

and is practiced by minorities in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

, North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

and Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

. The diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

of all of these groups, as well as converts around the world, also embrace and practice Theravāda Buddhism.

During the modern era, new developments have included Buddhist modernism

Buddhist modernism (also referred to as modern Buddhism, modernist Buddhism, and Neo-Buddhism are new movements based on modern era reinterpretations of Buddhism. David McMahan states that modernism in Buddhism is similar to those found in other ...

, the Vipassana movement

The Vipassanā movement, also called (in the United States) the Insight Meditation Movement and American vipassana movement, refers to a branch of modern Burmese Theravāda Buddhism that promotes "bare insight" (''sukha-vipassana'') to attain s ...

which reinvigorated Theravāda meditation practice, the growth of the Thai Forest Tradition

The Kammaṭṭhāna Forest Tradition of Thailand (from pi, kammaṭṭhāna meaning Kammaṭṭhāna, "place of work"), commonly known in the West as the Thai Forest Tradition, is a Parampara, lineage of Theravada Buddhist monasticism.

The ...

which reemphasized forest monasticism and the spread of Theravāda westward to places such as India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

, along with Buddhist immigrants and converts in the European Union and the United States.

History

Pre-Modern

The Theravāda school descends from the Vibhajjavāda, a division within the Sthāvira nikāya, one of the two major orders that arose after the first schism in the Indian Buddhist community.Cousins, Lance (2001). '

The Theravāda school descends from the Vibhajjavāda, a division within the Sthāvira nikāya, one of the two major orders that arose after the first schism in the Indian Buddhist community.Cousins, Lance (2001). 'On the Vibhajjavādins"

'', Buddhist Studies Review 18 (2), 131–182. Theravāda sources trace their tradition to the Third Buddhist council when elder

Moggaliputta-Tissa

Moggaliputtatissa (ca. 327–247 BCE), was a Buddhist monk and scholar who was born in Pataliputra, Magadha (now Patna, India) and lived in the 3rd century BCE. He is associated with the Third Buddhist council, the emperor Ashoka and the B ...

is said to have compiled the '' Kathavatthu'', an important work which lays out the Vibhajjavāda doctrinal position.Berkwitz, Stephen C. (2012). ''South Asian Buddhism: A Survey'', Routledge, pp. 44-45.

Aided by the patronage of Mauryan kings like Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

, this school spread throughout India and reached Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

through the efforts of missionary monks like Mahinda. In Sri Lanka, it became known as the Tambapaṇṇiya (and later as Mahāvihāravāsins) which was based at the Great Vihara (Mahavihara) in Anuradhapura

Anuradhapura ( si, අනුරාධපුරය, translit=Anurādhapuraya; ta, அனுராதபுரம், translit=Aṉurātapuram) is a major city located in north central plain of Sri Lanka. It is the capital city of North Central ...

(the ancient Sri Lankan capital). According to Theravāda sources, another one of the Ashokan missions was also sent to ''Suvaṇṇabhūmi'' ("The Golden Land"), which may refer to Southeast Asia.

By the first century BCE, Theravāda Buddhism was well established in the main settlements of the Kingdom of Anuradhapura

The Anuradhapura Kingdom ( Sinhala: , translit: Anurādhapura Rājadhāniya, Tamil: ), named for its capital city, was the first established kingdom in ancient Sri Lanka related to the Sinhalese people. Founded by King Pandukabhaya in 437 B ...

. The Pali Canon, which contains the main scriptures of the Theravāda, was committed to writing in the first century BCE. Throughout the history of ancient and medieval Sri Lanka, Theravāda was the main religion of the Sinhalese people

Sinhalese people ( si, සිංහල ජනතාව, Sinhala Janathāva) are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group native to the island of Sri Lanka. They were historically known as Hela people ( si, හෙළ). They constitute about 75% of t ...

and its temples and monasteries were patronized by the Sri Lankan kings, who saw themselves as the protectors of the religion.

Over time, two other sects split off from the Mahāvihāra tradition, the Abhayagiri and

Over time, two other sects split off from the Mahāvihāra tradition, the Abhayagiri and Jetavana

Jetavana (Jethawanaramaya or Weluwanaramaya ''buddhist literature'') was one of the most famous of the Buddhist monasteries or viharas in India (present-day Uttar Pradesh). It was the second vihara donated to Gautama Buddha after the Venuvan ...

.Warder, A.K. ''Indian Buddhism''. 2000. p. 280. While the Abhayagiri sect became known for the syncretic

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thu ...

study of Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

and Vajrayana

Vajrayāna ( sa, वज्रयान, "thunderbolt vehicle", "diamond vehicle", or "indestructible vehicle"), along with Mantrayāna, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, are names referring t ...

texts, as well as the Theravāda canon, the Mahāvihāra tradition, did not accept these new scriptures. Instead, Mahāvihāra scholars like Buddhaghosa

Buddhaghosa was a 5th-century Indian Theravada Buddhist commentator, translator and philosopher. He worked in the Great Monastery (''Mahāvihāra'') at Anurādhapura, Sri Lanka and saw himself as being part of the Vibhajjavāda school and in t ...

focused on the exegesis of the Pali scriptures and on the Abhidhamma. These Theravāda sub-sects often came into conflict with each other over royal patronage. The reign of Parākramabāhu I (1153–1186) saw an extensive reform of the Sri Lankan sangha after years of warfare on the island. Parākramabāhu created a single unified sangha which came to be dominated by the Mahāvihāra sect.

Epigraphical evidence has established that Theravāda Buddhism became a dominant religion in the Southeast Asian kingdoms of Sri Ksetra

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Sri Ksetra

, common_name = Kingdom of Sri Ksetra

, era = Classical Antiquity

, status = City-state

, event_start = Founding of Kingdom

, year_start = c. 3rd to 9th century CE

, date_start =

, ...

and Dvaravati

The Dvaravati ( th, ทวารวดี ; ) was an ancient Mon kingdom from the 7th century to the 11th century that was located in the region now known as central Thailand. It was described by the Chinese pilgrim in the middle of the 7th ce ...

from about the 5th century CE onwards. The oldest surviving Buddhist texts in the Pāli language are gold plates found at Sri Ksetra dated circa the 5th to 6th century. Before the Theravāda tradition became the dominant religion in Southeast Asia, Mahāyāna, Vajrayana and Hinduism were also prominent.

Starting at around the 11th century, Sinhalese Theravāda monks and Southeast Asian elites led a widespread conversion of most of mainland Southeast Asia to the Theravādin Mahavihara

Mahavihara () is the Sanskrit and Pali term for a great vihara (centre of learning or Buddhist monastery) and is used to describe a monastic complex of viharas.

Mahaviharas of India

A range of monasteries grew up in ancient Magadha (modern Bihar ...

school. The patronage of monarchs such as the Burmese king Anawrahta

Anawrahta Minsaw ( my, အနော်ရထာ မင်းစော, ; 11 May 1014 – 11 April 1077) was the founder of the Pagan Empire. Considered the father of the Burmese nation, Anawrahta turned a small principality in the dry zone ...

(Pali: Aniruddha, 1044–1077) and the Thai king Ram Khamhaeng

Ram Khamhaeng ( th, รามคำแหง, ) or Pho Khun Ram Khamhaeng Maharat ( th, พ่อขุนรามคำแหงมหาราช, ), also spelled Ramkhamhaeng, was the third king of the Phra Ruang Dynasty, ruling the Sukhot ...

(floruit

''Floruit'' (; abbreviated fl. or occasionally flor.; from Latin for "they flourished") denotes a date or period during which a person was known to have been alive or active. In English, the unabbreviated word may also be used as a noun indicatin ...

. late 13th century) was instrumental in the rise of Theravāda Buddhism as the predominant religion of Burma and Thailand.Yoneo Ishii (1986). ''Sangha, State, and Society: Thai Buddhism in History'', p. 60. University of Hawaii Press.

Burmese and Thai kings saw themselves as Dhamma Kings and as protectors of the Theravāda faith. They promoted the building of new temples, patronized scholarship, monastic ordinations and missionary works as well as attempted to eliminate certain non-Buddhist practices like animal sacrifices.Harvey (1925), pp. 172–173. During the 15th and 16th centuries, Theravāda also became established as the state religion in Cambodia and Laos. In Cambodia, numerous Hindu and Mahayana temples, most famously Angkor Wat

Angkor Wat (; km, អង្គរវត្ត, "City/Capital of Temples") is a temple complex in Cambodia and is the largest religious monument in the world, on a site measuring . Originally constructed as a Hinduism, Hindu temple dedicated ...

and Angkor Thom

Angkor Thom ( km, អង្គរធំ ; meaning "Great City"), alternatively Nokor Thom ( km, នគរធំ ) located in present-day Cambodia, was the last and most enduring capital city of the Khmer empire, Khmer Empire. It was established in ...

, were transformed into Theravādin monasteries.

Modern history

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Theravāda Buddhists came into direct contact with western ideologies, religions and modern science. The various responses to this encounter have been called "

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Theravāda Buddhists came into direct contact with western ideologies, religions and modern science. The various responses to this encounter have been called "Buddhist modernism

Buddhist modernism (also referred to as modern Buddhism, modernist Buddhism, and Neo-Buddhism are new movements based on modern era reinterpretations of Buddhism. David McMahan states that modernism in Buddhism is similar to those found in other ...

". In the British colonies of Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

(modern Sri Lanka) and Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

(Myanmar), Buddhist institutions lost their traditional role as the prime providers of education (a role that was often filled by Christian schools). In response to this, Buddhist organizations were founded which sought to preserve Buddhist scholarship and provide a Buddhist education. Anagarika Dhammapala

Anagārika Dharmapāla (Pali: ''Anagārika'', ; Sinhala: Anagārika, lit., si, අනගාරික ධර්මපාල; 17 September 1864 – 29 April 1933) was a Sri Lankan Buddhist revivalist and a writer.

Anagarika Dharmapāla is not ...

, Migettuwatte Gunananda Thera

Ven. Migettuwatte Gunananda Thera or Mohottiwatte Gunananda Thera ( si, පූජ්ය මිගෙට්ටුවත්තේ ගුණානන්ද හිමි) (9 February 1823, Balapitiya – 21 September 1890, Colombo) was a Sri ...

, Hikkaduwe Sri Sumangala Thera

Hikkaduwe Sri Sumangala Thera ( si, හික්කඩුවේ ශ්රි සුමංගල නාහිමි; 20 January 1827 – 29 April 1911) was a Sri Lankan Buddhist monk, who was one of the pioneers of Sri Lankan Buddhist revivalis ...

and Henry Steel Olcott

Colonel Henry Steel Olcott (2 August 1832 – 17 February 1907) was an American military officer, journalist, lawyer, Freemason and the co-founder and first president of the Theosophical Society.

Olcott was the first well-known American of Euro ...

(one of the first American western converts to Buddhism) were some of the main figures of the Sri Lankan Buddhist revival. Two new monastic orders were formed in the 19th century, the Amarapura Nikāya

The Amarapura Nikaya ( si, අමරපුර මහ නිකාය) was a Sri Lankan monastic fraternity ('' gaṇa'' or ''nikāya'') founded in 1800. It is named after the city of Amarapura, Burma, the capital of the Konbaung Dynasty of Bur ...

and the Rāmañña Nikāya

Rāmañña Nikāya ( pi, label=none, script=sinh, රාමඤ්ඤ නිකාය, also spelled Ramanya Nikaya) was one of the three major Buddhist orders in Sri Lanka. It was founded in 1864 when Ambagahawatte Saranankara, returned to Sri ...

.

In Burma, an influential modernist figure was king Mindon Min

Mindon Min ( my, မင်းတုန်းမင်း, ; 1808 – 1878), born Maung Lwin, was the penultimate King of Burma (Myanmar) from 1853 to 1878. He was one of the most popular and revered kings of Burma. Under his half brother King Pa ...

(1808–1878), known for his patronage of the Fifth Buddhist council

The Fifth Buddhist Council ( my, ပဉ္စမသင်္ဂါယနာ; pi, Pañcamasaṃgāyanā) took place in Mandalay, Burma (Myanmar) in 1871 CE under the auspices of King Mindon of Burma (Myanmar). The chief objective of this meeting ...

(1871) and the Tripiṭaka tablets at Kuthodaw Pagoda

Stone tablets inscribed with the ''Tripiṭaka'' (and other Buddhist texts) stand upright in the grounds of the Kuthodaw Pagoda ( means 'royal merit') at the foot of Mandalay Hill in Mandalay, Myanmar (Burma). The work was commissioned by King ...

(still the world's largest book) with the intention of preserving the Buddha Dhamma. Burma also saw the growth of the "Vipassana movement

The Vipassanā movement, also called (in the United States) the Insight Meditation Movement and American vipassana movement, refers to a branch of modern Burmese Theravāda Buddhism that promotes "bare insight" (''sukha-vipassana'') to attain s ...

", which focused on reviving Buddhist meditation and doctrinal learning. Ledi Sayadaw

Ledi Sayadaw U Ñaṇadhaja ( my, လယ်တီဆရာတော် ဦးဉာဏဓဇ, ; 1 December 1846 – 27 June 1923) was an influential Theravada Buddhist monk. He was recognized from a young age as being developed in both the theory ( ...

(1846–1923) was one of the key figures in this movement. After independence, Myanmar held the Sixth Buddhist council

The Sixth Buddhist Council ( pi, छट्ठ सॅगायना (); my, ဆဋ္ဌမသင်္ဂါယနာ; si, ඡට්ඨ සංගායනා) was a general council of Theravada Buddhism, held in a specially built cave and p ...

(Vesak

Vesak (Pali: ''Vesākha''; sa, Vaiśākha), also known as Buddha Jayanti, Buddha Purnima and Buddha Day, is a holiday traditionally observed by Buddhism, Buddhists in South Asia and Southeast Asia as well as Tibet and Mongolia. The festival ...

1954 to Vesak 1956) to create a new redaction of the Pāli Canon

The Pāli Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

During th ...

, which was then published by the government in 40 volumes. The Vipassana movement continued to grow after independence, becoming an international movement with centers around the world. Influential meditation teachers of the post-independence era include U Narada, Mahasi Sayadaw

Mahāsī Sayādaw U Sobhana ( my, မဟာစည်ဆရာတော် ဦးသောဘန, ; 29 July 1904 – 14 August 1982) was a Burmese Theravada Buddhist monk and meditation master who had a significant impact on the teaching of vipa ...

, Sayadaw U Pandita

Sayadaw U Paṇḍita ( my, ဆရာတော် ဦးပဏ္ဍိတ, ; also ''Ovādācariya Sayādo Ū Paṇḍitābhivaṁsa''; 28 July 1921 – 16 April 2016) was one of the foremost masters of Vipassanā. He trained in the Theravada ...

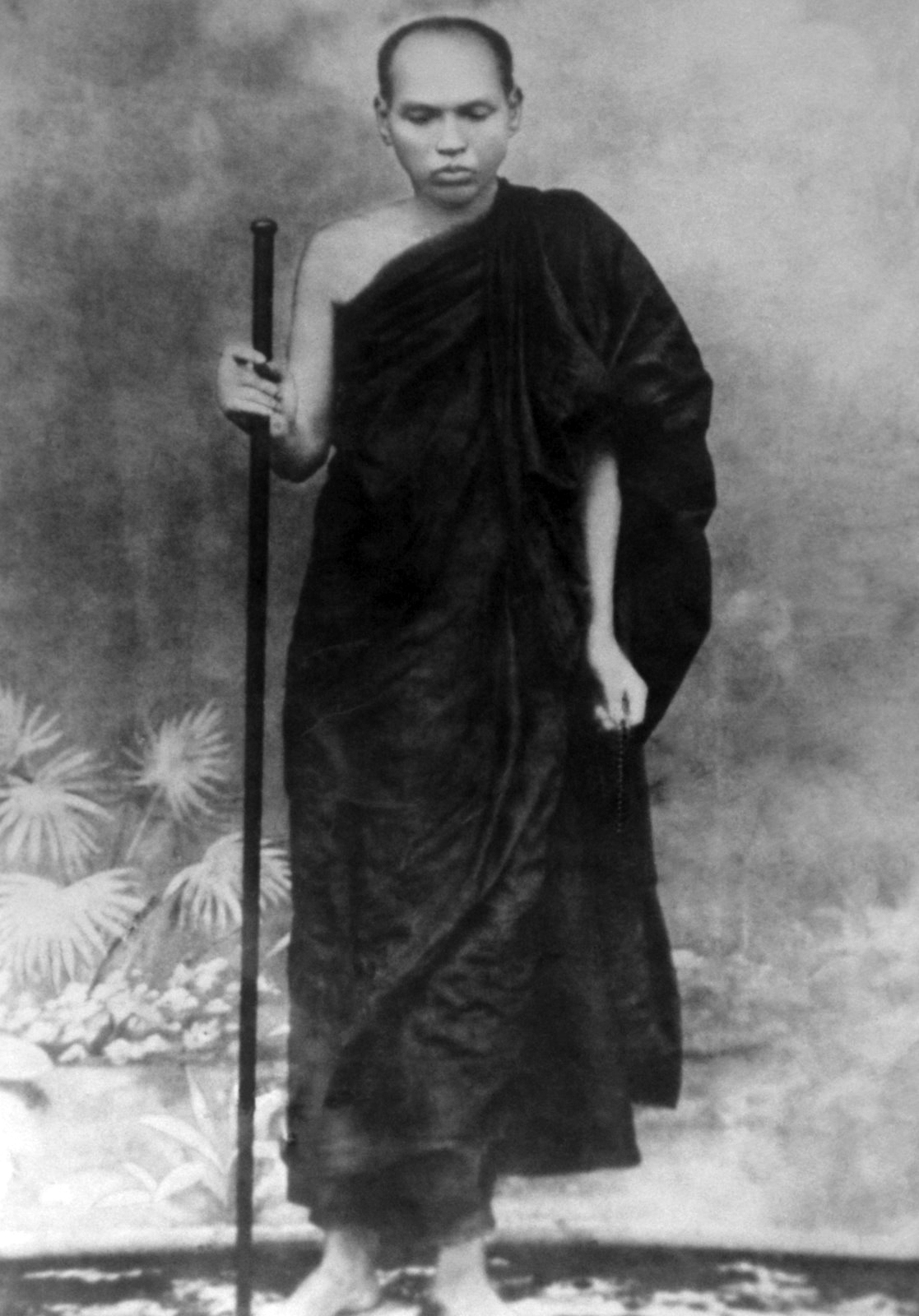

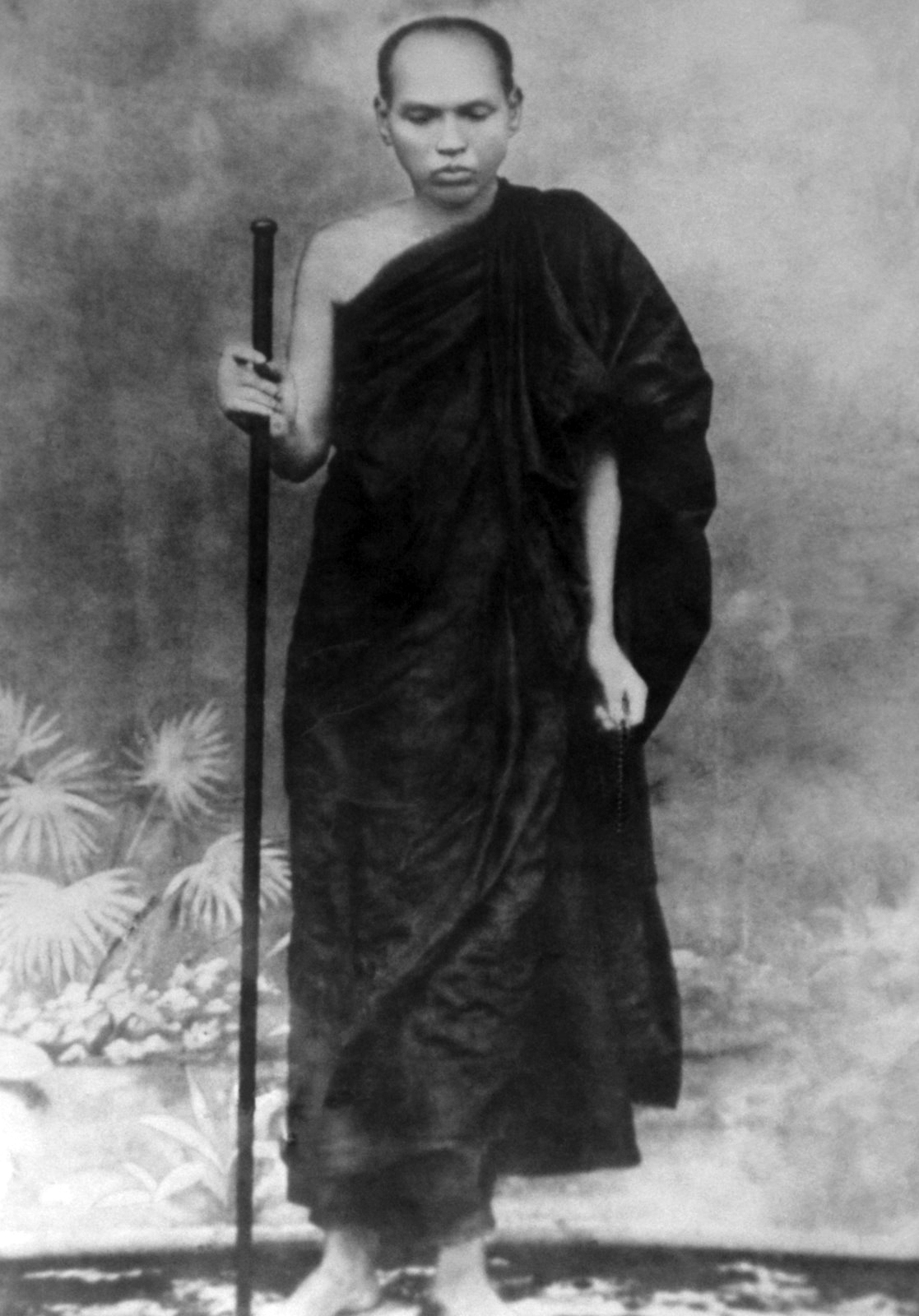

, Nyanaponika Thera

Nyanaponika Thera or Nyanaponika Mahathera (July 21, 1901 – 19 October 1994) was a German-born Theravada Buddhist monk and scholar who, after ordaining in Sri Lanka, later became the co-founder of the Buddhist Publication Society and author ...

, Webu Sayadaw

Webu Sayadaw ( my, ဝေဘူ ဆရာတော်, ; 17 February 1896 – 26 June 1977) was a Theravada Buddhist monk, and vipassanā master, best known for giving all importance to diligent practice, rather than scholastic achievement ...

, U Ba Khin

Sayagyi U Ba Khin ( my, ဘခင်, ; 6 March 1899 – 19 January 1971) was the first Accountant General of the Union of Burma. He was the founder of the International Meditation Centre in Yangon, Myanmar and is principally known as a leading ...

and his student S.N. Goenka.

Meanwhile, in Thailand (the only Theravāda nation to retain its independence throughout the colonial era), the religion became much more centralized, bureaucratized

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an Administration (government), administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments s ...

and controlled by the state after a series of reforms promoted by Thai kings of the Chakri dynasty

The Chakri dynasty ( th, ราชวงศ์ จักรี, , , ) is the current reigning dynasty of the Kingdom of Thailand, the head of the house is the king, who is head of state. The family has ruled Thailand since the founding of the ...

. King Mongkut

Mongkut ( th, มงกุฏ; 18 October 18041 October 1868) was the fourth monarch of Siam (Thailand) under the House of Chakri, titled Rama IV. He ruled from 1851 to 1868. His full title in Thai was ''Phra Bat Somdet Phra Menthora Ramathibod ...

(r. 1851–1868) and his successor Chulalongkorn

Chulalongkorn ( th, จุฬาลงกรณ์, 20 September 1853 – 23 October 1910) was the fifth monarch of Siam under the House of Chakri, titled Rama V. He was known to the Siamese of his time as ''Phra Phuttha Chao Luang'' (พร� ...

(1868–1910) were especially involved in centralizing sangha reforms. Under these kings, the sangha was organized into a hierarchical bureaucracy led by the Sangha Council of Elders (Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or ''Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhism ...

: ''Mahāthera Samāgama''), the highest body of the Thai sangha.Yoneo Ishii (1986). ''Sangha, State, and Society: Thai Buddhism in History'', p. 69. University of Hawaii Press. Mongkut also led the creation of a new monastic order, the Dhammayuttika

Dhammayuttika Nikāya (Pali language, Pali; th, ธรรมยุติกนิกาย; ; km, ធម្មយុត្តិកនិកាយ, ), or Dhammayut Order ( th, คณะธรรมยุต) is an Buddhist monasticism, order of ...

Nikaya, which kept a stricter monastic discipline than the rest of the Thai sangha (this included not using money, not storing up food and not taking milk in the evening).Patit Paban Mishra (2010). ''The History of Thailand,'' p. 77. Greenwood History of Modern Nations Series. The Dhammayuttika movement was characterized by an emphasis on the original Pali Canon and a rejection of Thai folk beliefs which were seen as irrational.Yoneo Ishii (1986). ''Sangha, State, and Society: Thai Buddhism in History'', p. 156. University of Hawaii Press. Under the leadership of Prince Wachirayan Warorot, a new education and examination system was introduced for Thai monks.Yoneo Ishii (1986). ''Sangha, State, and Society: Thai Buddhism in History'', p. 76. University of Hawaii Press.

The 20th century also saw the growth of "forest traditions" which focused on forest living and strict monastic discipline. The main forest movements of this era are the Sri Lankan Forest Tradition and the

The 20th century also saw the growth of "forest traditions" which focused on forest living and strict monastic discipline. The main forest movements of this era are the Sri Lankan Forest Tradition and the Thai Forest Tradition

The Kammaṭṭhāna Forest Tradition of Thailand (from pi, kammaṭṭhāna meaning Kammaṭṭhāna, "place of work"), commonly known in the West as the Thai Forest Tradition, is a Parampara, lineage of Theravada Buddhist monasticism.

The ...

, founded by Ajahn Mun

(หลวงปู่มั่น)Ajahn Mun ( th, อาจารย์มั่น)

, dharma_names = Bhuridatto

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Ban Khambong, Khong Chiam, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand

, death_date =

, death_place = Wat Pa Sutth ...

(1870–1949) and his students.

Theravāda Buddhism in Cambodia and Laos went through similar experiences in the modern era. Both had to endure French colonialism, destructive civil wars and oppressive communist governments. Under French Rule, French indologists of the École française d'Extrême-Orient

The French School of the Far East (french: École française d'Extrême-Orient, ), abbreviated EFEO, is an associated college of PSL University dedicated to the study of Asian societies. It was founded in 1900 with headquarters in Hanoi in wh ...

became involved in the reform of Buddhism, setting up institutions for the training of Cambodian and Lao monks, such as the Ecole de Pali which was founded in Phnom Penh in 1914''.'' While the Khmer Rouge effectively destroyed Cambodia's Buddhist institutions, after the end of the communist regime the Cambodian Sangha was re-established by monks who had returned from exile.Harris, Ian (August 2001), ''"Sangha Groupings in Cambodia",'' Buddhist Studies Review, UK Association for Buddhist Studies, 18 (I): 73–106. In contrast, communist rule in Laos was less destructive since the Pathet Lao

The Pathet Lao ( lo, ປະເທດລາວ, translit=Pa thēt Lāo, translation=Lao Nation), officially the Lao People's Liberation Army, was a communist political movement and organization in Laos, formed in the mid-20th century. The gro ...

sought to make use of the sangha for political ends by imposing direct state control. During the late 1980s and 1990s, the official attitudes toward Buddhism began to liberalise in Laos and there was a resurgence of traditional Buddhist activities such as merit-making and doctrinal study.

The modern era also saw the spread of Theravāda Buddhism around the world and the revival of the religion in places where it remains a minority faith. Some of the major events of the spread of modern Theravāda include:

*The 20th-century Nepalese Theravāda movement which introduced Theravāda Buddhism to

The modern era also saw the spread of Theravāda Buddhism around the world and the revival of the religion in places where it remains a minority faith. Some of the major events of the spread of modern Theravāda include:

*The 20th-century Nepalese Theravāda movement which introduced Theravāda Buddhism to Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

and was led by prominent figures such as Dharmaditya Dharmacharya

Dharmaditya Dharmacharya ( ne, धर्मादित्य धर्माचार्य) (born Jagat Man Vaidya) (1902–1963) was a Nepalese author, Buddhist scholar and language activist. He worked to develop Nepal Bhasa and revive Therava ...

, Mahapragya, Pragyananda and Dhammalok Mahasthavir

Dhammalok Mahasthavir ( ne, धम्मालोक महास्थविर) (born Das Ratna Tuladhar) (16 January 1890 – 17 October 1966) was a Nepalese Buddhist monk who worked to revive Theravada Buddhism in Nepal in the 1930s and 1 ...

.

*The establishment of some of the first Theravāda Viharas in the Western world, such as the London Buddhist Vihara

The London Buddhist Vihara ( Sinhala:ලන්ඩන් බෞද්ධ විහාරය ''Landan Bauddha Viharaya'') is one of the main Theravada Buddhist temples in the United Kingdom. The Vihara was the first Sri Lankan Buddhist monastery to ...

(1926), Das Buddhistische Haus

Das Buddhistische Haus (English language, English: Berlin Buddhist Vihara, literally ''the Buddhist house'') is a Theravada Buddhism, Buddhist temple complex (Vihara) in Frohnau, Berlin, Germany. It is considered to be the oldest and largest Thera ...

in Berlin (1957) and the Washington Buddhist Vihara in Washington, DC (1965).

*The founding of the Bengal Buddhist Association (1892) and the Dharmankur Vihar (1900) in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

by the Bengali monk Kripasaran

Venerable Kripasaran Mahathera (Bengali:- কৃপাশরণ মহাস্থবির, Kṛpāśôrôṇô Môhāsthôbirô) was a 19th and 20th century Bengali Buddhist monk and Indian yogi, best known for reviving Buddhism in British Indi ...

Mahasthavir, which were key events in the Bengali Theravāda revival.

*The founding of the Maha Bodhi Society

The Maha Bodhi Society is a South Asian Buddhist society presently based in Kolkata, India. Founded by the Sri Lankan Buddhist leader Anagarika Dharmapala and the British journalist and poet Sir Edwin Arnold, its first office was in Bodh Gaya. The ...

in 1891 by Anagarika Dharmapala

Anagārika Dharmapāla (Pali: ''Anagārika'', ; Sinhala: Anagārika, lit., si, අනගාරික ධර්මපාල; 17 September 1864 – 29 April 1933) was a Sri Lankan Buddhist revivalist and a writer.

Anagarika Dharmapāla is not ...

which focused on the conservation and restoration of important Indian Buddhist sites, such as Bodh Gaya

Bodh Gaya is a religious site and place of pilgrimage associated with the Mahabodhi Temple Complex in Gaya district in the Indian state of Bihar. It is famous as it is the place where Gautama Buddha is said to have attained Enlightenment ( pi, ...

and Sarnath

Sarnath (Hindustani pronunciation: aːɾnaːtʰ also referred to as Sarangnath, Isipatana, Rishipattana, Migadaya, or Mrigadava) is a place located northeast of Varanasi, near the confluence of the Ganges and the Varuna rivers in Uttar Pr ...

.Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.) ''The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism'', p. 41.

*The introduction of Theravāda to other Southeast Asian nations like Singapore, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

and Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

. Especially with Ven. K. Sri Dhammananda

K. Sri Dhammananda (born Martin Gamage, 18 March 1919 – 31 August 2006) was a Sri Lankan Buddhist monk and scholar.

Early life

Born in the village of Kirinde in Matara, Sri Lanka, Dhammananda spent most of his life and career in Malaysia. He ...

missionary efforts among English-speaking Chinese communities.

*The return of Western Theravādin monks trained in the Thai Forest Tradition to western countries and the subsequent founding of monasteries led by western monastics, such as Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery

Abhayagiri is a Theravadin Buddhist monastery of the Thai Forest Tradition in Redwood Valley, California. Its chief priorities are the teaching of Buddhist ethics, together with traditional concentration and insight meditation (also known as ...

, Chithurst Buddhist Monastery

''Cittaviveka'' (Pali: ' discerning mind'), commonly known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery, is an English Theravada Buddhist Monastery in the Thai Forest Tradition. It is situated in West Sussex, England in the hamlet of Chithurst between ...

, Metta Forest Monastery

Metta may refer to:

Buddhism

* Maitrī (aka ''mettā''), a Buddhist concept of love and kindness

* Metta Institute, a Buddhist training institute

* Mettā Forest Monastery, Valley Center, California, USA; a Buddhist monastery

Other uses

* Metta ...

, Amaravati Buddhist Monastery

Amaravati is a Theravada Buddhist monastery at the eastern end of the Chiltern Hills in South East England. Established in 1984 by Ajahn Sumedho as an extension of Chithurst Buddhist Monastery, the monastery has its roots in the Thai Forest Tr ...

, Birken Forest Buddhist Monastery

Birken Forest Buddhist Monastery, or Sītavana (Pali: "Cool Forest"), is a Theravada Buddhist monastery in the Thai Forest Tradition near Kamloops, British Columbia. It serves as a training centre for monastics and also a retreat facility for l ...

, Bodhinyana Monastery

Bodhinyana is a Theravada Buddhist monastery in the Thai Forest Tradition located in Serpentine, about 60 minutes' drive south-east of Perth, Australia.

History

The monastery was built in the 1980s and gained interest from Perth media over tim ...

and Santacittarama.

*The spread of the Vipassana movement

The Vipassanā movement, also called (in the United States) the Insight Meditation Movement and American vipassana movement, refers to a branch of modern Burmese Theravāda Buddhism that promotes "bare insight" (''sukha-vipassana'') to attain s ...

around the world by the efforts of people like S.N. Goenka

Satya Narayana Goenka (ISO 15919: ''Satyanārāyaṇ Goyankā''; ; 29 January 1924 – 29 September 2013) was an Indian teacher of Vipassanā meditation. Born in Burma to an Indian business family, he moved to India in 1969 and started tea ...

, Anagarika Munindra

Anagarika Shri Munindra (1915 – October 14, 2003), also called Munindraji by his disciples, was an Indian Vipassanā meditation teacher, who taught many notable meditation teachers including Dipa Ma, Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzberg, and Sur ...

, Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield

Jack Kornfield (born 1945) is an American writer and teacher in the Vipassana movement in American Theravada Buddhism. He trained as a Buddhist monk in Thailand, Burma and India, first as a student of the Thai forest master Ajahn Chah and Maha ...

, Sharon Salzberg

Sharon Salzberg (born August 5, 1952) is a ''New York Times'' bestselling author and teacher of Buddhist meditation practices in the West. In 1974, she co-founded the Insight Meditation Society at Barre, Massachusetts, with Jack Kornfield and Jos ...

, Dipa Ma

Nani Bala Barua (March 25, 1911 - September 1, 1989), better known as Dipa Ma, was an Indian meditation teacher of Theravada Buddhism and was of Barua descent. She was a prominent Buddhist master in Asia and also taught in the United States where ...

, and Ruth Denison Ruth Denison (September 29, 1922 – February 26, 2015) was the first Buddhist teacher in the United States to lead an all-women's retreat for Buddhist meditation and instruction. Her center, Dhamma Dena Desert Vipassana Center is located in the Mo ...

.

*The Vietnamese Theravāda movement, led by figures such as Ven. Hộ-Tông (Vansarakkhita).

Texts

Pāli Tipiṭaka

According to Kate Crosby, for Theravāda, the PāliTipiṭaka

The Pāli Canon is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravada Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language. It is the most complete extant early Buddhist canon. It derives mainly from the Tamrashatiya school.

During t ...

, also known as the Pāli Canon is "the highest authority on what constitutes the Dhamma (the truth or teaching of the Buddha) and the organization of the Sangha (the community of monks and nuns)."

The language of the Tipiṭaka, Pāli

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or ''Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhism ...

, is a middle-Indic language which is the main religious and scholarly language in Theravāda. This language may have evolved out of various Indian dialects, and is related to, but not the same as, the ancient language of Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

.

An early form of the Tipiṭaka may have been transmitted to Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

during the reign of Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

, which saw a period of Buddhist missionary activity. After being orally transmitted (as was the custom for religious texts in those days) for some centuries, the texts were finally committed to writing in the 1st century BCE. Theravāda is one of the first Buddhist schools to commit its Tipiṭaka to writing. The recension Recension is the practice of editing or revising a text based on critical analysis. When referring to manuscripts, this may be a revision by another author. The term is derived from Latin ''recensio'' ("review, analysis").

In textual criticism (as ...

of the Tipiṭaka which survives today is that of the Sri Lankan Mahavihara sect.

The oldest manuscripts of the Tipiṭaka from Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia date to the 15th Century, and they are incomplete.Skilling, Peter. "Reflections on the Pali Literature of Siam". From Birch Bark to Digital Data: Recent Advances in Buddhist Manuscript Research: Papers Presented at the Conference Indic Buddhist Manuscripts: The State of the Field. Stanford, 15–19 June 2009, edited by Paul Harrison and Jens-Uwe Hartmann, 1st ed., Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, Wien, 2014, pp. 347–366. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1vw0q4q.25. Accessed 7 May 2020. Complete manuscripts of the four Nikayas are only available from the 17th Century onwards.Anālayo. "The Historical Value of the Pāli Discourses". Indo-Iranian Journal, vol. 55, no. 3, 2012, pp. 223–253. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24665100. Accessed 7 May 2020. However, fragments of the Tipiṭaka have been found in inscriptions from Southeast Asia, the earliest of which have been dated to the 3rd or 4th century.Wynne, Alexander. ''Did the Buddha exist?'' JOCBS. 2019(16): 98–148. According to Alexander Wynne, "they agree almost exactly with extant Pāli manuscripts. This means that the Pāli Tipiṭaka has been transmitted with a high degree of accuracy for well over 1,500 years."

There are numerous editions of the Tipiṭaka, some of the major modern editions include the Pali Text Society

The Pali Text Society is a text publication society founded in 1881 by Thomas William Rhys Davids "to foster and promote the study of Pāli texts".

Pāli is the language in which the texts of the Theravada school of Buddhism are preserved. The Pā ...

edition (published in Roman script), the Burmese Sixth Council edition (in Burmese script

Burmese may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Myanmar, a country in Southeast Asia

* Burmese people

* Burmese language

* Burmese alphabet

* Burmese cuisine

* Burmese culture

Animals

* Burmese cat

* Burmese chicken

* Burmese (horse), a ...

, 1954–56) and the Thai Tipiṭaka edited and published in Thai script

The Thai script ( th, อักษรไทย, ) is the abugida used to write Thai, Southern Thai and many other languages spoken in Thailand. The Thai alphabet itself (as used to write Thai) has 44 consonant symbols ( th, พยัญชนะ ...

after the council held during the reign of Rama VII

Prajadhipok ( th, ประชาธิปก, RTGS: ''Prachathipok'', 8 November 1893 – 30 May 1941), also Rama VII, was the seventh monarch of Siam of the Chakri dynasty. His reign was a turbulent time for Siam due to political and ...

(1925–35). There is also a Khmer edition, published in Phnom Penh

Phnom Penh (; km, ភ្នំពេញ, ) is the capital and most populous city of Cambodia. It has been the national capital since the French protectorate of Cambodia and has grown to become the nation's primate city and its economic, indus ...

(1931–69).

The Pāli Tipitaka consists of three parts: the Vinaya Pitaka

The Vinaya (Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon (''Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (Buddhism), Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinay ...

, Sutta Pitaka and Abhidhamma Pitaka. Of these, the Abhidhamma Pitaka is believed to be a later addition to the collection, its composition dating from around the 3rd century BCE onwards. The Pāli Abhidhamma was not recognized outside the Theravāda school. There are also some texts which were late additions that are included in the fifth Nikaya, the ''Khuddaka Nikāya

The Khuddaka Nikāya () is the last of the five nikayas, or collections, in the Sutta Pitaka, which is one of the "three baskets" that compose the Pali Tipitaka, the scriptures of Theravada Buddhism. This nikaya consists of fifteen (Thailand) ...

'' ('Minor Collection'), such as the '' Paṭisambhidāmagga'' (possibly c. 3rd to 1st century BCE) and the ''Buddhavaṃsa

The ''Buddhavaṃsa'' (also known as the ''Chronicle of Buddhas'') is a hagiographical Buddhist text which describes the life of Gautama Buddha and of the twenty-four Buddhas who preceded him and prophesied his attainment of Buddhahood. It is ...

'' (c. 1st and 2nd century BCE).

The main parts of the Sutta Pitaka and some portions of the Vinaya

The Vinaya (Pali & Sanskrit: विनय) is the division of the Buddhist canon ('' Tripitaka'') containing the rules and procedures that govern the Buddhist Sangha (community of like-minded ''sramanas''). Three parallel Vinaya traditions remai ...

show considerable overlap in content with the Agamas

Religion

*Āgama (Buddhism), a collection of Early Buddhist texts

*Āgama (Hinduism), scriptures of several Hindu sects

*Jain literature (Jain Āgamas), various canonical scriptures in Jainism

Other uses

* ''Agama'' (lizard), a genus of lizards ...

, the parallel collections used by non-Theravāda schools in India which are preserved in Chinese and partially in Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

, Prakrit

The Prakrits (; sa, prākṛta; psu, 𑀧𑀸𑀉𑀤, ; pka, ) are a group of vernacular Middle Indo-Aryan languages that were used in the Indian subcontinent from around the 3rd century BCE to the 8th century CE. The term Prakrit is usu ...

, and Tibetan

Tibetan may mean:

* of, from, or related to Tibet

* Tibetan people, an ethnic group

* Tibetan language:

** Classical Tibetan, the classical language used also as a contemporary written standard

** Standard Tibetan, the most widely used spoken dial ...

, as well as the various non-Theravāda Vinayas. On this basis, these Early Buddhist texts

Early Buddhist texts (EBTs), early Buddhist literature or early Buddhist discourses are parallel texts shared by the early Buddhist schools. The most widely studied EBT material are the first four Pali Nikayas, as well as the corresponding Chines ...

(i.e. the Nikayas and parts of the Vinaya) are generally believed to be some of the oldest and most authoritative sources on the doctrines of pre-sectarian Buddhism

Pre-sectarian Buddhism, also called early Buddhism, the earliest Buddhism, original Buddhism, and primitive Buddhism, is Buddhism as theorized to have existed before the various Early Buddhist schools developed, around 250 BCE (followed by later ...

by modern scholars.

Much of the material in the earlier portions is not specifically "Theravādan", but the collection of teachings that this school's adherents preserved from the early, non-sectarian body of teachings. According to Peter Harvey

Peter Michael St Clair Harvey (16 September 19442 March 2013) was an Australian journalist and broadcaster. Harvey was a long-serving correspondent and contributor with the Nine Network from 1975 to 2013.

Career

Harvey studied his journalism ...

, while the Theravādans may have added texts to their Tipiṭaka (such as the Abhidhamma texts and so on), they generally did not tamper with the earlier material.

The historically later parts of the canon, mainly the Abhidhamma and some parts of the Vinaya, contain some distinctive elements and teachings which are unique to the Theravāda school and often differ from the Abhidharmas or Vinayas of other early Buddhist schools

The early Buddhist schools are those schools into which the Buddhist monastic saṅgha split early in the history of Buddhism. The divisions were originally due to differences in Vinaya and later also due to doctrinal differences and geographic ...

. For example, while the Theravāda Vinaya contains a total of 227 monastic rules for bhikkhu

A ''bhikkhu'' (Pali: भिक्खु, Sanskrit: भिक्षु, ''bhikṣu'') is an ordained male in Buddhist monasticism. Male and female monastics ("nun", ''bhikkhunī'', Sanskrit ''bhikṣuṇī'') are members of the Sangha (Buddhist ...

s, the Dharmaguptaka

The Dharmaguptaka (Sanskrit: धर्मगुप्तक; ) are one of the eighteen or twenty early Buddhist schools, depending on the source. They are said to have originated from another sect, the Mahīśāsakas. The Dharmaguptakas had a p ...

Vinaya (used in East Asian Buddhism

East Asian Buddhism or East Asian Mahayana is a collective term for the schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed across East Asia which follow the Chinese Buddhist canon. These include the various forms of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vi ...

) has a total of 253 rules for bhikkhus (though the overall structure is the same). These differences arose from the systematization and historical development of doctrines and monasticism in the centuries after the death of the Buddha.

The Abhidhamma-pitaka contains "a restatement of the doctrine of the Buddha in strictly formalized language." Its texts present a new method, the Abhidhamma method, which attempts to build a single consistent philosophical system (in contrast with the suttas, which present numerous teachings given by the Buddha to particular individuals according to their needs). Because the Abhidhamma focuses on analyzing the internal lived experience of beings and the intentional structure of consciousness, it has often been compared to a kind of phenomenological psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries betwe ...

by numerous modern scholars such as Nyanaponika

Nyanaponika Thera or Nyanaponika Mahathera (July 21, 1901 – 19 October 1994) was a German-born Theravada Buddhist monk and scholar who, after ordaining in Sri Lanka, later became the co-founder of the Buddhist Publication Society and auth ...

, Bhikkhu Bodhi

Bhikkhu Bodhi (born December 10, 1944), born Jeffrey Block, is an American Theravada Buddhist monk, ordained in Sri Lanka and currently teaching in the New York and New Jersey area. He was appointed the second president of the Buddhist Publica ...

and Alexander Piatigorsky

Alexander Moiseyevich Piatigorsky (russian: Алекса́ндр Моисе́евич Пятиго́рский; 30 January 192925 October 2009) was a Soviet dissident, Russian philosopher, scholar of Indian philosophy and culture, historian, phi ...

.

The Theravāda school has traditionally held the doctrinal position that the canonical Abhidhamma Pitaka was actually taught by the Buddha himself. Modern scholarship in contrast, has generally held that the Abhidhamma texts date from the 3rd century BCE onwards. However some scholars, such as Frauwallner, also hold that the early Abhidhamma texts developed out of exegetical

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

and catechetical

Catechesis (; from Greek language, Greek: , "instruction by word of mouth", generally "instruction") is basic Christian religious education of children and adults, often from a catechism book. It started as education of Conversion to Christian ...

work which made use of doctrinal lists which can be seen in the suttas, called ''matikas.''

Non-canonical literature

There are numerous Theravāda works which are important for the tradition even though they are not part of the Tipiṭaka. Perhaps the most important texts apart from the Tipiṭaka are the works of the influential scholar

There are numerous Theravāda works which are important for the tradition even though they are not part of the Tipiṭaka. Perhaps the most important texts apart from the Tipiṭaka are the works of the influential scholar Buddhaghosa

Buddhaghosa was a 5th-century Indian Theravada Buddhist commentator, translator and philosopher. He worked in the Great Monastery (''Mahāvihāra'') at Anurādhapura, Sri Lanka and saw himself as being part of the Vibhajjavāda school and in t ...

(4th–5th century CE), known for his Pāli commentaries (which were based on older Sri Lankan commentaries of the Mahavihara tradition). He is also the author of a very important compendium of Theravāda doctrine, the ''Visuddhimagga

The ''Visuddhimagga'' (Pali; English: ''The Path of Purification''), is the 'great treatise' on Buddhist practice and Theravāda Abhidhamma written by Buddhaghosa approximately in the 5th century in Sri Lanka. It is a manual condensing and syst ...

''.Crosby, 2013, p. 86. Other figures like Dhammapala and Buddhadatta Buddhadatta Thera was a 5th-century Theravada Buddhist writer from the town of Uragapura in the Chola kingdom of South India.Potter, Karl H; Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Buddhist philosophy from 350 to 600 A.D. pg 216 He wrote many of his w ...

also wrote Theravāda commentaries and other works in Pali during the time of Buddhaghosa. While these texts do not have the same scriptural authority in Theravāda as the Tipiṭaka, they remain influential works for the exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (logic), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern usage, ...

of the Tipiṭaka.

An important genre of Theravādin literature is shorter handbooks and summaries, which serve as introductions and study guides for the larger commentaries. Two of the more influential summaries are Sariputta Thera's ''Pālimuttakavinayavinicchayasaṅgaha,'' a summary of Buddhaghosa's Vinaya commentary and Anuruddha's '' Abhidhammaṭṭhasaṅgaha'' (a "Manual of Abhidhamma").Crosby, 2013, 86.

Throughout the history of Theravāda, Theravāda monks also produced other works of Pāli literature such as historical chronicles (like the '' Dipavamsa'' and the '' Mahavamsa''), hagiographies

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies might ...

, poetry, Pāli grammars, and " sub-commentaries" (that is, commentaries on the commentaries).

While Pāli texts are symbolically and ritually important for many Theravādins, most people are likely to access Buddhist teachings through vernacular literature, oral teachings, sermons, art and performance as well as films and Internet media. According to Kate Crosby, "there is a far greater volume of Theravāda literature in vernacular languages than in Pāli."

An important genre of Theravādin literature, in both Pāli and vernacular languages, are the Jataka tales

The Jātakas (meaning "Birth Story", "related to a birth") are a voluminous body of literature native to India which mainly concern the previous births of Gautama Buddha in both human and animal form. According to Peter Skilling, this genre is ...

, stories of the Buddha's past lives. They are very popular among all classes and are rendered in a wide variety of media formats, from cartoons to high literature. The Vessantara Jātaka

The ''Vessantara Jātaka'' is one of the most popular jātakas of Theravada Buddhism. The ''Vessantara Jātaka'' tells the story of one of Gautama Buddha's past lives, about a very compassionate and generous prince, Vessantara, who gives away ev ...

is one of the most popular of these.

Most Theravāda Buddhists generally consider Mahāyāna Buddhist scriptures to be apocrypha

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

l, meaning that they are not authentic words of the Buddha.

Doctrine

Core teachings

The core of Theravāda Buddhist doctrine is contained in the Pāli Canon, the only complete collection ofEarly Buddhist Texts

Early Buddhist texts (EBTs), early Buddhist literature or early Buddhist discourses are parallel texts shared by the early Buddhist schools. The most widely studied EBT material are the first four Pali Nikayas, as well as the corresponding Chines ...

surviving in a classical Indic language. These basic Buddhist ideas are shared by the other Early Buddhist schools as well as by Mahayana traditions. They include central concepts such as:

*A doctrine of Karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptivel ...

(action), which is based on intention ('' cetana'') and a related doctrine of rebirth

Rebirth may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Film

* ''Rebirth'' (2011 film), a 2011 Japanese drama film

* ''Rebirth'' (2016 film), a 2016 American thriller film

* ''Rebirth'', a documentary film produced by Project Rebirth

* ''The Re ...

which holds that after death, sentient beings which are not fully awakened will transmigrate to another body, possibly in another realm of existence. The type of realm one will be reborn in is determined by the being's past karma. This cyclical universe filled with birth and death is named samsara.

*A rejection of other doctrines and practices found in Brahmanical Hinduism

The historical Vedic religion (also known as Vedicism, Vedism or ancient Hinduism and subsequently Brahmanism (also spelled as Brahminism)), constituted the religious ideas and practices among some Indo-Aryan peoples of northwest Indian Subco ...

, including the idea that the Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the ...

are a divine authority. Any form of sacrifices to the gods (including animal sacrifices

Animal sacrifice is the ritual killing and offering of one or more animals, usually as part of a religious ritual or to appease or maintain favour with a deity. Animal sacrifices were common throughout Europe and the Ancient Near East until the spr ...

) and ritual purification

Ritual purification is the ritual prescribed by a religion by which a person is considered to be free of ''uncleanliness'', especially prior to the worship of a deity, and ritual purity is a state of ritual cleanliness. Ritual purification may ...

by bathing are considered useless and spiritually corrupted. The Pāli texts also reject the idea that castes

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultura ...

are divinely ordained.

*A set of major teachings called the ''bodhipakkhiyādhammā

In Buddhism, the ''bodhipakkhiyā dhammā'' (Pali; variant spellings include ''bodhipakkhikā dhammā'' and ''bodhapakkhiyā dhammā''; Skt.: ''bodhipaka dharma'') are qualities (''dhammā'') conducive or related to (''pakkhiya'') awakening/unde ...

'' (factors conducive to awakening).

*Descriptions of various meditative practices or states, namely the four ''jhanas'' (meditative absorptions) and the formless dimensions (''arupāyatana'').

* Ethical training (''sila'') including the ten courses of wholesome action and the five precepts

The Five precepts ( sa, pañcaśīla, italic=yes; pi, pañcasīla, italic=yes) or five rules of training ( sa, pañcaśikṣapada, italic=yes; pi, pañcasikkhapada, italic=yes) is the most important system of morality for Buddhist lay peo ...

.

*Nirvana

( , , ; sa, निर्वाण} ''nirvāṇa'' ; Pali: ''nibbāna''; Prakrit: ''ṇivvāṇa''; literally, "blown out", as in an oil lampRichard Gombrich, ''Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benāres to Modern Colombo.' ...

(Pali: ''nibbana''), the highest good and final goal in Theravāda Buddhism. It is the complete and final end of suffering, a state of perfection. It is also the end of all rebirth, but it is ''not'' an annihilation ('' uccheda'').

*The corruptions or influxes ('' āsavas''), such as the corruption of sensual pleasures (''kāmāsava''), existence-corruption (''bhavāsava''), and ignorance-corruption (''avijjāsava'').

*The doctrine of impermanence (''anicca

Impermanence, also known as the philosophical problem of change, is a philosophical concept addressed in a variety of religions and philosophies. In Eastern philosophy it is notable for its role in the Buddhist three marks of existence. It is ...

''), which holds that all physical and mental phenomena are transient, unstable and inconstant.

*The doctrine of not-self ('' anatta''), which holds that all the constituents of a person, namely, the five aggregates

(Sanskrit) or (Pāḷi) means "heaps, aggregates, collections, groupings". In Buddhism, it refers to the five aggregates of clinging (), the five material and mental factors that take part in the rise of craving and clinging. They are also ...

( physical form, feelings

Feelings are subjective self-contained phenomenal experiences. According to the ''APA Dictionary of Psychology'', a feeling is "a self-contained phenomenal experience"; and feelings are "subjective, evaluative, and independent of the sensations ...

, perceptions

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system ...

, intentions

Intentions are mental states in which the agent commits themselves to a course of action. Having the plan to visit the zoo tomorrow is an example of an intention. The action plan is the ''content'' of the intention while the commitment is the ''a ...

and consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience and awareness of internal and external existence. However, the lack of definitions has led to millennia of analyses, explanations and debates by philosophers, theologians, linguisticians, and scien ...

), are empty of a self (''atta Atta or ATTA may refer to:

* Atta Halilintar, Indonesian YouTuber, singer and entrepreneur

* ''Atta'' (ant), a genus of ants in the family Formicidae

* ''Atta'' (novel), a 1953 novel by Francis Rufus Bellamy

* Atta flour, whole wheat flour made f ...

''), since they are impermanent and not always under our control. Therefore, there is no unchanging substance, permanent self, soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun ''soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest attes ...

, or essence.

*The Five hindrances

In the Buddhist tradition, the five hindrances ( Sinhala: ''පඤ්ච නීවරණ pañca nīvaraṇa''; Pali: ') are identified as mental factors that hinder progress in meditation and in our daily lives. In the Theravada tradition, thes ...

(''pañca nīvaraṇāni''), which are obstacles to meditation: (1) sense desire, (2) hostility, (3) sloth and torpor, (4) restlessness and worry and (5) doubt.

*The Four Divine Abodes (''brahmavihārā''), also known as the four immeasurables (''appamaññā'')

* The Four Noble Truths, which state, in brief: (1) There is ''dukkha'' (suffering, unease); (2) There is a cause of dukkha, mainly craving ('' tanha''); (3) The removal of craving leads to the end (''nirodha

In Buddhism, nirodha, "cessation," "extinction," or "suppression," refers to the cessation or renouncing of craving and desire. It is the third of the Four Noble Truths, stating that suffering ( dukkha) ceases when craving and desire are renoun ...

'') of suffering, and (4) there is a path (''magga'') to follow to bring this about.

*The framework of Dependent Arising

A dependant is a person who relies on another as a primary source of income. A common-law spouse who is financially supported by their partner may also be included in this definition. In some jurisdictions, supporting a dependant may enabl ...

(''paṭiccasamuppāda''), which explains how suffering arises (beginning with ignorance

Ignorance is a lack of knowledge and understanding. The word "ignorant" is an adjective that describes a person in the state of being unaware, or even cognitive dissonance and other cognitive relation, and can describe individuals who are unaware o ...

and ending in birth, old age and death) and how suffering can be brought to an end.

*The Middle Way

The Middle Way ( pi, ; sa, ) as well as "teaching the Dharma by the middle" (''majjhena dhammaṃ deseti'') are common Buddhist terms used to refer to two major aspects of the Dharma, that is, the teaching of the Buddha.; my, အလယ်� ...

, which is seen as having two major facets. First, it is a middle path between extreme asceticism and sensual indulgence. It is also seen as a middle view between the idea that at death beings are annihilated and the idea that there is an eternal self (Pali: ''atta'').

* The Noble Eightfold Path, one of the main outlines of the Buddhist path to awakening. The eight factors are: Right View, Right Intention, Right Speech, Right Conduct, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Samadhi

''Samadhi'' (Pali and sa, समाधि), in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditative consciousness. In Buddhism, it is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Ashtanga Yoga ...

.

*The practice of taking refuge in the "Triple Gems": the Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a śramaṇa, wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was ...

, the Dhamma

Dharma (; sa, धर्म, dharma, ; pi, dhamma, italic=yes) is a key concept with multiple meanings in Indian religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and others. Although there is no direct single-word translation for ''d ...

and the Saṅgha

Sangha is a Sanskrit word used in many Indian languages, including Pali meaning "association", "assembly", "company" or "community"; Sangha is often used as a surname across these languages. It was historically used in a political context t ...

.

*The Seven Aids to Awakening (''satta bojjhaṅgā''): mindfulness (''sati

Sati or SATI may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Sati'' (film), a 1989 Bengali film by Aparna Sen and starring Shabana Azmi

* ''Sati'' (novel), a 1990 novel by Christopher Pike

*Sati (singer) (born 1976), Lithuanian singer

*Sati, a character in ''Th ...

''), investigation (''dhamma vicaya

In Buddhism, ''dhamma vicaya'' (Pali; sa, dharma-) has been variously translated as the "analysis of qualities," "discrimination of ''dhammas''," "discrimination of states," "investigation of doctrine,"

and "searching the Truth." The meaning is ...

''), energy ('' viriya''), bliss (''pīti

''Pīti'' in Pali (Sanskrit: ''Prīti'') is a mental factor (Pali:''cetasika'', Sanskrit: ''caitasika'') associated with the development of '' jhāna'' (Sanskrit: ''dhyāna'') in Buddhist meditation. According to Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, ''piti'' i ...

'')'','' relaxation (''passaddhi

''Passaddhi'' is a Pali noun (Sanskrit: prasrabhi, Tibetan: ཤིན་ཏུ་སྦྱང་བ་,Tibetan Wylie: shin tu sbyang ba) that has been translated as "calmness", "tranquillity", "repose" and "serenity." The associated verb is ''pa ...

''), samādhi

''Samadhi'' (Pali and sa, समाधि), in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditation, meditative consciousness. In Buddhism, it is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Ash ...

, and equanimity ('' upekkha'').

*The six sense bases (''saḷāyatana'') and a corresponding theory of Sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the cen ...

impression ( ''phassa'') and consciousness ( ''viññana'').

*Various frameworks for the practice of mindfulness

Mindfulness is the practice of purposely bringing one's attention to the present-moment experience without evaluation, a skill one develops through meditation or other training. Mindfulness derives from ''sati'', a significant element of Hind ...