The Isle of Wight on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a

The earliest clear evidence of

The earliest clear evidence of  A submerged escarpment 11m below sea level off

A submerged escarpment 11m below sea level off

There are indications that the island had wide trading links, with a port at

There are indications that the island had wide trading links, with a port at

The Norman Conquest of 1066 created the position of

The Norman Conquest of 1066 created the position of  For nearly 200 years the island was a semi-independent feudal fiefdom, with the de Redvers family ruling from Carisbrooke. The final private owner was the Countess

For nearly 200 years the island was a semi-independent feudal fiefdom, with the de Redvers family ruling from Carisbrooke. The final private owner was the Countess

During the

During the

The

The

The island has a single

The island has a single

The Isle of Wight is situated between the Solent and the

The Isle of Wight is situated between the Solent and the

File:Isle of Wight OS OpenData map.png,

* Newport is the centrally located county town, with a population of about 25,000 and the island's main shopping area. Located next to the

* Newport is the centrally located county town, with a population of about 25,000 and the island's main shopping area. Located next to the

The largest industry on the island is tourism, but it also has a strong agricultural heritage, including

The largest industry on the island is tourism, but it also has a strong agricultural heritage, including

Tourism is still the largest industry, and most island towns and villages offer hotels, hostels and camping sites. In 1999, it hosted 2.7 million visitors, with 1.5 million staying overnight, and 1.2 million day visits; only 150,000 of these were from abroad. Between 1993 and 2000, visits increased at an average rate of 3% per year.

At the turn of the 19th century the island had ten

Tourism is still the largest industry, and most island towns and villages offer hotels, hostels and camping sites. In 1999, it hosted 2.7 million visitors, with 1.5 million staying overnight, and 1.2 million day visits; only 150,000 of these were from abroad. Between 1993 and 2000, visits increased at an average rate of 3% per year.

At the turn of the 19th century the island had ten

The island is home to the

The island is home to the

The Isle of Wight has of roadway. It does not have a motorway, although there is a short stretch of dual carriageway towards the north of Newport near the hospital and prison.

A comprehensive bus network operated by Southern Vectis links most settlements, with Newport as its central hub.

Journeys away from the island involve a ferry journey. Car ferry and passenger catamaran services are run by

The Isle of Wight has of roadway. It does not have a motorway, although there is a short stretch of dual carriageway towards the north of Newport near the hospital and prison.

A comprehensive bus network operated by Southern Vectis links most settlements, with Newport as its central hub.

Journeys away from the island involve a ferry journey. Car ferry and passenger catamaran services are run by

Visit Isle of Wight Official Website

Isle of Wight Council website

Isleofwight.com

*

Images of the Isle of Wight

at the English Heritage Archive {{DEFAULTSORT:Wight, Isle of Isle of Wight, Islands of England Islands of the English Channel Local government districts of South East England, Isle of Wight Natural regions of England NUTS 2 statistical regions of the United Kingdom, Isle of Wight South East England Unitary authority districts of England, Isle of Wight Counties of England established in 1974, Isle of Wight

county

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( J├©rriais), (Guern├®siais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, M├┤r Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

, off the coast of Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

, from which it is separated by the Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit which projects into the Solent narrows the sea crossing between Hurst Castle and Colwell Bay to ...

. It is the largest

Large means of great size.

Large may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Arbitrarily large, a phrase in mathematics

* Large cardinal, a property of certain transfinite numbers

* Large category, a category with a proper class of objects and morphisms (or ...

and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of Wight has resorts that have been popular holiday destinations since Victorian times

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardi ...

. It is known for its mild climate, coastal scenery, and verdant landscape of fields, downland

Downland, chalkland, chalk downs or just downs are areas of open chalk hills, such as the North Downs. This term is used to describe the characteristic landscape in southern England where chalk is exposed at the surface. The name "downs" is deriv ...

and chine

A chine () is a steep-sided coastal gorge where a river flows to the sea through, typically, soft eroding cliffs of sandstone or clays. The word is still in use in central Southern EnglandŌĆönotably in East Devon, Dorset, Hampshire and the Isl ...

s. The island is historically

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

part of Hampshire, and is designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve

Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) is an intergovernmental scientific program, launched in 1971 by UNESCO, that aims to establish a scientific basis for the improvement of relationships between people and their environments.

MAB's work engag ...

.

The island has been home to the poets Algernon Charles Swinburne

Algernon Charles Swinburne (5 April 1837 ŌĆō 10 April 1909) was an English poet, playwright, novelist, and critic. He wrote several novels and collections of poetry such as ''Poems and Ballads'', and contributed to the famous Eleventh Edition ...

and Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 ŌĆō 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

. Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 ŌĆō 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

built her summer residence and final home, Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house himself, in t ...

at East Cowes

East Cowes is a town and civil parish in the north of the Isle of Wight, on the east bank of the River Medina, next to its west bank neighbour Cowes.

The two towns are connected by the Cowes Floating Bridge, a chain ferry operated by the Isle ...

, on the Isle. It has a maritime and industrial tradition of boat-building

Boat building is the design and construction of boats and their systems. This includes at a minimum a hull, with propulsion, mechanical, navigation, safety and other systems as a craft requires.

Construction materials and methods

Wood

W ...

, sail-making, the manufacture of flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

s, hovercraft

A hovercraft, also known as an air-cushion vehicle or ACV, is an amphibious Craft (vehicle), craft capable of travelling over land, water, mud, ice, and other surfaces.

Hovercraft use blowers to produce a large volume of air below the hull ...

, and Britain's space rockets

A launch vehicle or carrier rocket is a rocket designed to carry a payload (spacecraft or satellites) from the Earth's surface to outer space. Most launch vehicles operate from a launch pad, launch pads, supported by a missile launch contro ...

. The island hosts annual music festivals, including the Isle of Wight Festival

The Isle of Wight Festival is a British music festival which takes place annually in Newport on the Isle of Wight, England. It was originally a counterculture event held from 1968 to 1970.

The 1970 event was by far the largest of these early ...

, which in 1970 was the largest rock music event ever held. It has well-conserved wildlife and some of the richest cliffs and quarries of dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s in Europe.

The island has played an important part in the defence of the ports of Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, and has been near the front-line of conflicts through the ages, having faced the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felic├Łsima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

and weathered the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. Rural for most of its history, its Victorian fashionability and the growing affordability of holidays led to significant urban development during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The island became a separate administrative county

An administrative county was a first-level administrative division in England and Wales from 1888 to 1974, and in Ireland from 1899 until either 1973 (in Northern Ireland) or 2002 (in the Republic of Ireland). They are now abolished, although mos ...

in 1890, making it independent of Hampshire. It continued to share the Lord Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ...

of Hampshire until 1974, when it was made its own ceremonial county

The counties and areas for the purposes of the lieutenancies, also referred to as the lieutenancy areas of England and informally known as ceremonial counties, are areas of England to which lords-lieutenant are appointed. Legally, the areas i ...

. The Isle no longer has administrative links to Hampshire, though the two counties share their police force

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and th ...

and fire and rescue service

A firefighter is a first responder and rescuer extensively trained in firefighting, primarily to extinguish conflagration, hazardous fires that threaten life, property, and the environment as well as to rescue people and in some cases or jurisd ...

, and the island's Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

churches belongs to the Diocese of Portsmouth (originally Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

). A combined local authority with Portsmouth and Southampton was considered, but was unlikely to proceed as of 2017.

The quickest public transport link to the mainland is the hovercraft

A hovercraft, also known as an air-cushion vehicle or ACV, is an amphibious Craft (vehicle), craft capable of travelling over land, water, mud, ice, and other surfaces.

Hovercraft use blowers to produce a large volume of air below the hull ...

(Hovertravel

Hovertravel is a ferry company operating from Southsea, Portsmouth to Ryde, Isle of Wight, UK. It is the only passenger hovercraft company currently operating in Britain since Hoverspeed stopped using its craft in favour of catamarans and sub ...

) from Ryde

Ryde is an English seaside town and civil parish on the north-east coast of the Isle of Wight. The built-up area had a population of 23,999 according to the 2011 Census and an estimate of 24,847 in 2019. Its growth as a seaside resort came af ...

to Southsea

Southsea is a seaside resort and a geographic area of Portsmouth, Portsea Island in England. Southsea is located 1.8 miles (2.8 km) to the south of Portsmouth's inner city-centre. Southsea is not a separate town as all of Portsea Island's s ...

. Three vehicle ferry and two catamaran services cross the Solent to Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, Lymington

Lymington is a port town on the west bank of the Lymington River on the Solent, in the New Forest district of Hampshire, England. It faces Yarmouth, Isle of Wight, to which there is a car ferry service operated by Wightlink. It is within the ...

and Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

via the island's largest ferry operator, Wightlink

Wightlink is a ferry company operating routes across The Solent between Hampshire and the Isle of Wight in the south of England. It operates car ferries between Lymington and Yarmouth, and Portsmouth and Fishbourne and a fast passenger-only ...

, and the island's second largest ferry company, Red Funnel

Red Funnel, the trading name of the Southampton Isle of Wight and South of England Royal Mail Steam Packet Company Limited,Domesday Book

Domesday Book () ŌĆō the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" ŌĆō is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

called the island ''Wit.'' The modern Welsh name is ''Ynys Wyth'' (''ynys'' meaning island). These are all variant forms of the same name, possibly Celtic in origin.

Inhabitants of the Isle of Wight were known as ''Wihtware''.

Toponym

* Place of the division * The island that lifts up out of the sea.History

Pre-Bronze Age

DuringPleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

s, sea levels were lower and the present day Solent was part of the valley of the Solent River. The river flowed eastward from Dorset, following the course of the modern Solent strait, before travelling south and southwest towards the major Channel River system. At these times extensive gravel terraces associated with the Solent River and the forerunners of the island's modern rivers were deposited. During warmer interglacial periods silts, beach gravels, clays and muds of marine and estuarine origin were deposited as a result of higher sea levels, similar to those experienced today.

The earliest clear evidence of

The earliest clear evidence of Lower Palaeolithic

The Lower Paleolithic (or Lower Palaeolithic) is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears in ...

archaic human occupation on what is now the Isle of Wight is found close to Priory Bay

Priory Bay is a small privately owned bay on the northeast coast of the Isle of Wight, England. It lies to the east of Nettlestone village and another mile along the coast from Seaview. It stretches from Horestone Point in the north to Nodes ...

. Here more than 300 acheulean handaxes have been recovered from the beach and cliff slopes, originating from a sequence of Pleistocene gravels dating approximately to MIS 11

MIS or mis may refer to:

Science and technology

* Management information system

* Marine isotope stage, stages of the Earth's climate

* Maximal independent set, in graph theory

* Metal-insulator-semiconductor, e.g., in MIS capacitor

* Minimally in ...

-MIS 9 Marine Isotope Stage 9 (MIS 9) is a Marine Isotope Stage in the geological record. It is the final period of the Lower Paleolithic, and lasts from 337,000 to 300,000 years ago according to Lisiecki and Raymo's LR04 Benthic Stack, which has been ado ...

(424,000ŌĆō374,000 years ago). Reworked and abraded artefacts found at the site may be considerably older however, closer to 500,000 years old. The identity of the hominids who produced these tools is unknown, but sites and fossils of the same age range in Europe are often attributed to ''Homo heidelbergensis

''Homo heidelbergensis'' (also ''H. sapiens heidelbergensis''), sometimes called Heidelbergs, is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human which existed during the Middle Pleistocene. It was subsumed as a subspecies of ''H. erectus'' in ...

'' or early populations of Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While th ...

s.

A Middle Palaeolithic

The Middle Paleolithic (or Middle Palaeolithic) is the second subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age as it is understood in Europe, Africa and Asia. The term Middle Stone Age is used as an equivalent or a synonym for the Middle Paleoli ...

Mousterian

The Mousterian (or Mode III) is an archaeological industry of stone tools, associated primarily with the Neanderthals in Europe, and to the earliest anatomically modern humans in North Africa and West Asia. The Mousterian largely defines the latt ...

flint assemblage, consisting of 50 handaxes and debitage, has been recovered from Great Pan Farm in the Medina Valley near Newport. Gravel sequences at the site have been dated to the MIS 3 interstadial, during the last glacial period (c. 50,000 years ago). These tools are associated with late Neanderthal occupation, and evidence of late Neanderthal presence is seen across Britain at this time.

No major evidence of Upper Palaeolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

activity exists on the Isle of Wight. This period is associated with the expansion and establishment of populations of modern human

Early modern human (EMH) or anatomically modern human (AMH) are terms used to distinguish ''Homo sapiens'' (the only extant Hominina species) that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans from extin ...

(''Homo sapiens'') hunter-gatherers

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

in Europe, beginning around 45,000 years ago. However, evidence of late Upper Palaeolithic activity has been found at nearby sites on the mainland, notably Hengistbury Head

Hengistbury Head (), formerly also called Christchurch Head, is a headland jutting into the English Channel between Bournemouth and Mudeford in the English county of Dorset. It is a site of international importance in terms of its archaeology ...

in Dorset, dating to just prior to onset of the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togethe ...

and the end of the last glacial period.

A submerged escarpment 11m below sea level off

A submerged escarpment 11m below sea level off Bouldnor Cliff

Bouldnor Cliff is a submerged prehistoric settlement site in the Solent. The site dates from the Mesolithic era and is in approximately of water just offshore of the village of Bouldnor

Bouldnor is a hamlet near Yarmouth on the west co ...

on the island's northwest coastline is home to an internationally significant mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: ╬╝╬ŁŽā╬┐Žé, ''mesos'' 'middle' + ╬╗╬»╬Ė╬┐Žé, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymous ...

archaeological site. The site has yielded evidence of seasonal occupation by Mesolithic hunter-gatherers dating to c. 6050 BC. Finds include flint tools, burnt flint, worked timbers, wooden platforms and pits. The worked wood shows evidence of the splitting of large planks from oak trunks, interpreted as being intended for use as dug-out canoes. DNA analysis of sediments at the site yielded wheat DNA, not found in Britain until the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

2,000 years after the occupation at Bouldnor Cliff. It has been suggested this is evidence of wide-reaching trade in Mesolithic Europe; however, the contemporaneity of the wheat with the Mesolithic occupation has been contested. When hunter-gatherers used the site it was located on a river bank surrounded by wetland and woodland. As sea levels rose throughout the Holocene the river valley slowly flooded, submerging the site.

Evidence of Mesolithic occupation on the island is generally found along the river valleys, particularly along the north of the Island, and in the former catchment of the western Yar. Further key sites are found at Newtown Creek, Werrar and Wootton-Quarr.

Neolithic occupation on the Isle of Wight is primarily attested to by flint tools and monuments. Unlike the previous Mesolithic hunter-gatherer population, Neolithic communities on the Isle of Wight were based on farming and linked to a migration of Neolithic populations from France and northwest Europe to Britain c. 6,000 years ago.

The Isle of Wight's most visible Neolithic site is the Longstone at Mottistone

Mottistone is a village on the Isle of Wight, located in the popular tourist area the Back of the Wight.http://www.backofthewight.net It is located 8 Miles southwest of Newport in the southwest of the island, and is home to the National Trus ...

, the remains of an early Neolithic long-barrow. Originally constructed with two standing stones at the entrance, only one remains standing today. A Neolithic mortuary enclosure has been identified on Tennyson Down

Tennyson Down is a hill at the west end of the Isle of Wight just south of Totland. Tennyson Down is a grassy, whale-backed ridge of chalk which rises to 482 ft/147m above sea level. Tennyson Down is named after the poet Lord Tennyson who li ...

near Freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does include ...

.

Bronze and Iron Age

Bronze Age Britain

Bronze Age Britain is an era of British history that spanned from until . Lasting for approximately 1,700 years, it was preceded by the era of Neolithic Britain and was in turn followed by the period of Iron Age Britain. Being categorised as t ...

had large reserves of tin in the areas of Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

and Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

and tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

is necessary to smelt

Smelt may refer to:

* Smelting, chemical process

* The common name of various fish:

** Smelt (fish), a family of small fish, Osmeridae

** Australian smelt in the family Retropinnidae and species ''Retropinna semoni''

** Big-scale sand smelt ''At ...

bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12ŌĆō12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

. At that time the sea level was much lower and carts of tin were brought across the Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit which projects into the Solent narrows the sea crossing between Hurst Castle and Colwell Bay to ...

at low tide for export, possibly on the Ferriby Boats

The Ferriby Boats are three Bronze-Age British sewn plank-built boats, parts of which were discovered at North Ferriby in the East Riding of the English county of Yorkshire. Only a small number of boats of a similar period have been found i ...

. Anthony Snodgrass suggests that a shortage of tin, as a part of the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

Collapse and trade disruptions in the Mediterranean around 1300 BC, forced metalworkers to seek an alternative to bronze. From the 7th century BC, during the Late Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

, the Isle of Wight, like the rest of Great Britain, was occupied by the Celtic Britons

The Britons ( *''Pritan─½'', la, Britanni), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were people of Celtic language and culture who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age and into the Middle Ages, at which point th ...

, in the form of the Durotriges

The Durotriges were one of the Celtic tribes living in Britain prior to the Roman invasion. The tribe lived in modern Dorset, south Wiltshire, south Somerset and Devon east of the River Axe and the discovery of an Iron Age hoard in 2009 at Shalfle ...

tribe; as attested by finds of their coins, for example, the South Wight Hoard, and the Shalfleet Hoard. The island was known as ''Ynys Weith'' in Brittonic Celtic. South eastern Britain experienced significant immigration that is reflected in the genetic makeup of the current residents. As the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

began, the value of tin likely dropped sharply, greatly changing the Isle of Wight's economy. Trade however continued, as evidenced by the local abundance of European Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

coins.

Roman period

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC ŌĆō 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

reported that the Belgae

The Belgae () were a large confederation of tribes living in northern Gaul, between the English Channel, the west bank of the Rhine, and the northern bank of the river Seine, from at least the third century BC. They were discussed in depth by Ju ...

took the Isle of Wight in about 85 BC, and recognised the culture of this general region as "Belgic", but made no reference to Vectis. The Roman historian Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

mentions that the island was captured by the commander Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 ŌĆō 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Empi ...

. The Romans built no towns on the island, but the remains of at least seven Roman villa

A Roman villa was typically a farmhouse or country house built in the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, sometimes reaching extravagant proportions.

Typology and distribution

Pliny the Elder (23ŌĆō79 AD) distinguished two kinds of villas n ...

s have been found, indicating the prosperity of local agriculture. First-century exports were principally hides, slaves, hunting dogs, grain, cattle, silver, gold, and iron.

Early Medieval period

There are indications that the island had wide trading links, with a port at

There are indications that the island had wide trading links, with a port at Bouldnor

Bouldnor is a hamlet near Yarmouth on the west coast of the Isle of Wight in southern England. It is the location of Bouldnor Battery, a gun battery emplacement.

Bouldnor is located on the A3054 road, and public transport is provided by buses ...

, evidence of Bronze Age tin trading, and finds of Late Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

coins. Starting in AD 449, the 5th and 6th centuries saw groups of Germanic-speaking peoples from Northern Europe crossing the English Channel and gradually set about conquering the region.

During the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

the island was settled by Jutes

The Jutes (), Iuti, or Iut├” ( da, Jyder, non, J├│tar, ang, ─Æotas) were one of the Germanic tribes who settled in Great Britain after the departure of the Romans. According to Bede, they were one of the three most powerful Germanic nations ...

as the pagan kingdom of the Wihtwara

The Wihtwara were one of the tribes of Anglo-Saxon Britain. Their territory was a tribal kingdom located on the Isle of Wight before it was conquered by the Kingdom of Wessex in the late seventh century. The tribe's name is preserved in the na ...

under King Arwald

King Arwald (died 686 AD) was the last King of the Isle of Wight and last pagan king in Anglo-Saxon England. Saint Arwald is the name collectively given to King Arwald's sons or brothers who, being baptised before their execution, were later ca ...

. In 685 it was invaded by King C├”dwalla of Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

who tried to replace the inhabitants with his own followers. Though in 686 Arwald was defeated and the island became the last part of English lands to be converted to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, C├”dwalla was unsuccessful in driving the Jutes from the island. Wight was then added to Wessex and became part of England under King Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great (alt. ├ålfred 848/849 ŌĆō 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King ├åthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bot ...

, included within the shire

Shire is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries such as Australia and New Zealand. It is generally synonymous with county. It was first used in Wessex from the beginn ...

of Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

.

It suffered especially from Viking

Vikings ; non, v├Łkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

raids, and was often used as a winter base by Viking raiders when they were unable to reach Normandy. Later, both Earl Tostig

Tostig Godwinson ( 102925 September 1066) was an Anglo-Saxon Earl of Northumbria and brother of King Harold Godwinson. After being exiled by his brother, Tostig supported the Norwegian king Harald Hardrada's invasion of England, and was killed ...

and his brother Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( ŌĆō 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings, fighting the Norman invaders led by William the C ...

(who became King Harold II) held manors on the island.

Norman Conquest ŌĆō 19th century

The Norman Conquest of 1066 created the position of

The Norman Conquest of 1066 created the position of Lord of the Isle of Wight

The Lord of the Isle of Wight was a feudal title, at times hereditary and at others by royal appointment in the Kingdom of England, before the development of an extensive peerage system.

William the Conqueror granted the lordship of the Isle o ...

; the island was given by William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33ŌĆō 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

to his kinsman William FitzOsbern

William FitzOsbern, 1st Earl of Hereford, Lord of Breteuil ( 1011 ŌĆō 22 February 1071), was a relative and close counsellor of William the Conqueror and one of the great magnates of early Norman England. FitzOsbern was created Earl of Hereford ...

. Carisbrooke Priory and the fort of Carisbrooke Castle

Carisbrooke Castle is a historic motte-and-bailey castle located in the village of Carisbrooke (near Newport), Isle of Wight, England. Charles I was imprisoned at the castle in the months prior to his trial.

Early history

The site of Carisbro ...

were then founded. Allegiance was sworn to FitzOsbern rather than the king; the Lordship was subsequently granted to the de Redvers family by Henry I, after his succession in 1100.

For nearly 200 years the island was a semi-independent feudal fiefdom, with the de Redvers family ruling from Carisbrooke. The final private owner was the Countess

For nearly 200 years the island was a semi-independent feudal fiefdom, with the de Redvers family ruling from Carisbrooke. The final private owner was the Countess Isabella de Fortibus

Isabel de Forz (July 1237 ŌĆō 10 November 1293) (or Isabel de Redvers, Latinized to Isabella de Fortibus) was the eldest daughter of Baldwin de Redvers, 6th Earl of Devon (1217ŌĆō1245). On the death of her brother Baldwin de Redvers, 7th Earl ...

, who, on her deathbed in 1293, was persuaded to sell it to Edward I

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 ŌĆō 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassal o ...

. Thereafter the island was under control of the English Crown and its Lordship a royal appointment.

The island continued to be attacked from the continent: it was raided in 1374 by the fleet of Castile, and in 1377 by French raiders who burned several towns, including Newtown.

Under Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, who developed the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

and its Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

base, the island was fortified at Yarmouth

Yarmouth may refer to:

Places Canada

*Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia

**Yarmouth, Nova Scotia

**Municipality of the District of Yarmouth

**Yarmouth (provincial electoral district)

**Yarmouth (electoral district)

* Yarmouth Township, Ontario

*New ...

, Cowes, East Cowes, and Sandown

Sandown is a seaside resort and civil parishes in England, civil parish on the south-east coast of the Isle of Wight, United Kingdom with the resort of Shanklin to the south and the settlement of Lake, Isle of Wight, Lake in between. Together ...

.

The French invasion on 21 July 1545 (famous for the sinking of the ''Mary Rose

The ''Mary Rose'' (launched 1511) is a carrack-type warship of the English Tudor navy of King Henry VIII. She served for 33 years in several wars against France, Scotland, and Brittany. After being substantially rebuilt in 1536, she saw her l ...

'' on the 19th) was repulsed by local militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

.

During the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642ŌĆō1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, King Charles I fled to the Isle of Wight, believing he would receive sympathy from the governor Robert Hammond, but Hammond imprisoned the king in Carisbrooke Castle.

During the

During the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756ŌĆō1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754ŌĆ ...

, the island was used as a staging post for British troops departing on expeditions against the French coast, such as the Raid on Rochefort

The Raid on Rochefort (or Descent on Rochefort) was a British amphibious attempt to capture the French Atlantic port of Rochefort in September 1757 during the Seven Years' War. The raid pioneered a new tactic of "descents" on the French coast ...

. During 1759, with a planned French invasion imminent, a large force of soldiers was stationed there. The French called off their invasion following the Battle of Quiberon Bay

The Battle of Quiberon Bay (known as ''Bataille des Cardinaux'' in French) was a decisive naval engagement during the Seven Years' War. It was fought on 20 November 1759 between the Royal Navy and the French Navy in Quiberon Bay, off the coast ...

.

19th century ŌĆō present

In the mid 1840sPotato Blight

''Phytophthora infestans'' is an oomycete or water mold, a fungus-like microorganism that causes the serious potato and tomato disease known as late blight or potato blight. Early blight, caused by ''Alternaria solani'', is also often called "po ...

was found first in the UK on the Island having arrived from Belgium. It later was transmitted to Ireland.

In the 1860s, what remains in real terms the most expensive ever government spending project saw fortifications built on the island and in the Solent, as well as elsewhere along the south coast, including the Palmerston Forts

The Palmerston Forts are a group of forts and associated structures around the coasts of the United Kingdom and Ireland.

The forts were built during the Victorian period on the recommendations of the 1860 Royal Commission on the Defence of the ...

, The Needles Batteries

The Needles Batteries are two military batteries built above the Needles stacks to guard the West end of the Solent. The field of fire was from approximately West South West clockwise to Northeast and they were designed to defend against enem ...

and Fort Victoria, because of fears about possible French invasion.

The future Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 ŌĆō 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

spent childhood holidays on the island and became fond of it. When she became queen she made Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house himself, in t ...

her winter home, and so the island became a fashionable holiday resort, including for Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 ŌĆō 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

, Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron (''n├®e'' Pattle; 11 June 1815 ŌĆō 26 January 1879) was a British photographer who is considered one of the most important portraitists of the 19th century. She is known for her soft-focus close-ups of famous Victorian m ...

, and Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 ŌĆō 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

(who wrote much of ''David Copperfield

''David Copperfield'' Dickens invented over 14 variations of the title for this work, see is a novel in the bildungsroman genre by Charles Dickens, narrated by the eponymous David Copperfield, detailing his adventures in his journey from inf ...

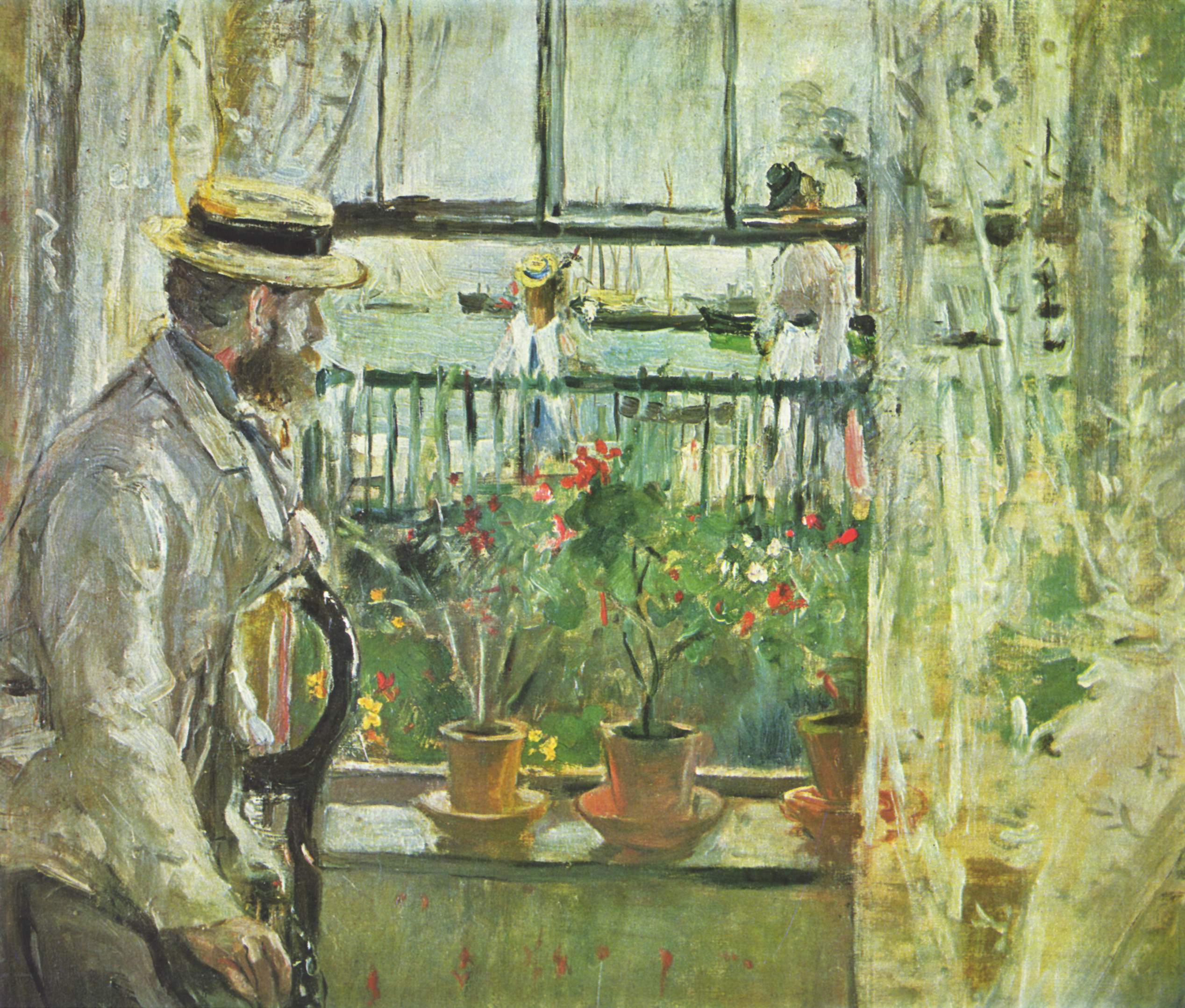

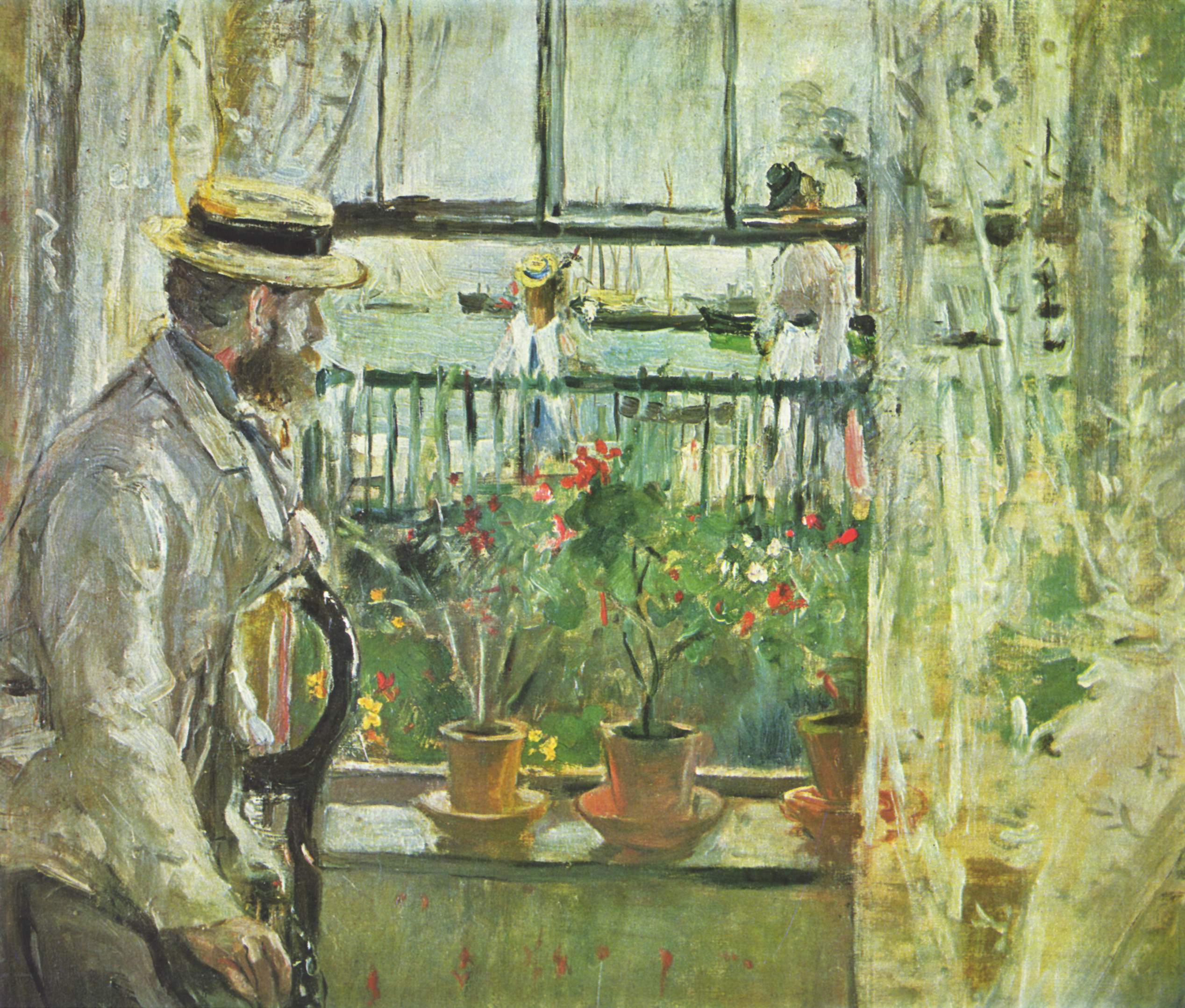

'' there), as well as the French painter Berthe Morisot

Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot (; January 14, 1841 ŌĆō March 2, 1895) was a French painter and a member of the circle of painters in Paris who became known as the Impressionists.

In 1864, Morisot exhibited for the first time in the highly es ...

and members of European royalty.

Until the queen's example, the island had been rural, with most people employed in farming, fishing or boat-building. The boom in tourism, spurred by growing wealth and leisure time, and by Victoria's presence, led to significant urban development of the island's coastal resorts. As one report summarizes, "The QueenŌĆÖs regular presence on the island helped put the Isle of Wight 'on the map' as a Victorian holiday and wellness destination ... and her former residence Osborne House is now one of the most visited attractions on the island" While on the island, the queen used a bathing machine

The bathing machine was a device, popular from the 18th century until the early 20th century, to allow people to change out of their usual clothes, change into swimwear, and wade in the ocean at beaches. Bathing machines were roofed and walled woo ...

that could be wheeled into the water on Osborne Beach; inside the small wooden hut she could undress and then bathe, without being visible to others. Her machine had a changing room and a WC with plumbing. The refurbished machine is now displayed at the beach.

On 14 January 1878, Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (, born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 ŌĆō August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born inventor, scientist and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He also co-founded the American Telephone and Te ...

demonstrated an early version of the telephone to the queen, placing calls to Cowes, Southampton and London. These were the first publicly-witnessed long distance telephone calls in the UK. The queen tried the device and considered the process to be "quite extraordinary" although the sound was "rather faint". She later asked to buy the equipment that was used, but Bell offered to make "a set of telephones" specifically for her.

The world's first radio station was set up by Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi (; 25 April 187420 July 1937) was an Italians, Italian inventor and electrical engineering, electrical engineer, known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegrap ...

in 1897, during her reign, at the Needles Battery

The Needles Batteries are two military batteries built above the Needles stacks to guard the West end of the Solent. The field of fire was from approximately West South West clockwise to Northeast and they were designed to defend against enem ...

, at the western tip of the island. A high mast was erected near the Royal Needles Hotel, as part of an experiment of communicating with ships at sea. That location is now the site of the Marconi Monument. In 1898 the first paid wireless telegram (called a "Marconigram") was sent from this station, and the island was for some time the home of the National Wireless Museum, near Ryde.

Queen Victoria died at Osborne House on 22 January 1901, at the age of 81.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countriesŌĆöincluding all of the great powersŌĆöforming two opposin ...

the island was frequently bombed. With its proximity to German-occupied France, the island hosted observation stations and transmitters, as well as the RAF radar station at Ventnor. It was the starting-point for one of the earlier Operation Pluto

Operation Pluto (Pipeline Under the Ocean or Pipeline Underwater Transportation of Oil, also written Operation PLUTO) was an operation by British engineers, oil companies and the British Armed Forces to construct submarine oil pipelines un ...

pipelines to feed fuel to Europe after the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

.

The Needles Battery

The Needles Batteries are two military batteries built above the Needles stacks to guard the West end of the Solent. The field of fire was from approximately West South West clockwise to Northeast and they were designed to defend against enemy ...

was used to develop and test the Black Arrow

Black Arrow, officially capitalised BLACK ARROW, was a British satellite carrier rocket. Developed during the 1960s, it was used for four launches between 1969 and 1971, all launched from the Woomera Prohibited Area in Australia. Its final flig ...

and Black Knight

The black knight is a literary stock character who masks his identity and that of his liege by not displaying heraldry. Black knights are usually portrayed as villainous figures who use this anonymity for misdeeds. They are often contrasted with t ...

space rockets, which were subsequently launched from Woomera, Australia.

Isle of Wight Festival

The Isle of Wight Festival is a British music festival which takes place annually in Newport on the Isle of Wight, England. It was originally a counterculture event held from 1968 to 1970.

The 1970 event was by far the largest of these early ...

was a very large rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

festival that took place near Afton Down

Afton Down is a chalk down near the village of Freshwater on the Isle of Wight. Afton Down faces Compton Bay directly to the west, while Freshwater is approximately one mile north.

It was the site of the Isle of Wight Festival 1970, where the ...

, West Wight in August 1970, following two smaller concerts in 1968 and 1969. The 1970 show was one of the last public performances by Jimi Hendrix

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942September 18, 1970) was an American guitarist, singer and songwriter. Although his mainstream career spanned only four years, he is widely regarded as one of the most ...

and attracted somewhere between 600,000 and 700,000 attendees. The festival was revived in 2002 in a different format, and is now an annual event.

On 26 October 2020 an oil tanker the Nave Andromeda, suspected to have been hijacked by Nigerian stowaways, was stormed south east of the island by the Special Boat Service

The Special Boat Service (SBS) is the special forces unit of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy. The SBS can trace its origins back to the Second World War when the Army Special Boat Section was formed in 1940. After the Second World War, the Roya ...

. Seven people believed to be Nigerians seeking UK asylum were handed over to Hampshire Police.

Governance

The island has a single

The island has a single Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

. The Isle of Wight constituency covers the entire island, with 138,300 permanent residents in 2011

File:2011 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: a protester partaking in Occupy Wall Street heralds the beginning of the Occupy movement; protests against Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, who was killed that October; a young man celebrate ...

, being one of the most populated constituencies

An electoral district, also known as an election district, legislative district, voting district, constituency, riding, ward, division, or (election) precinct is a subdivision of a larger state (a country, administrative region, or other polity ...

in the United Kingdom (more than 50% above the English average). In 2011 following passage of the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act, the Sixth Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies

The 2013 Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies, also known as the sixth Review, or just boundary changes, was an ultimately unfruitful cycle of the process by which constituencies of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom are reviewe ...

was to have changed this, but this was deferred to no earlier than October 2022 by the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013

The Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013 (c. 6) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

With the Sixth Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies in some doubt following the collapse of the House of Lords Reform Bill 2 ...

. Thus the single constituency remained for the 2015

File:2015 Events Collage new.png, From top left, clockwise: Civil service in remembrance of November 2015 Paris attacks; Germanwings Flight 9525 was purposely crashed into the French Alps; the rubble of residences in Kathmandu following the Apri ...

, 2017

File:2017 Events Collage V2.png, From top left, clockwise: The War Against ISIS at the Battle of Mosul (2016-2017); aftermath of the Manchester Arena bombing; The Solar eclipse of August 21, 2017 ("Great American Eclipse"); North Korea tests a ser ...

and 2019

File:2019 collage v1.png, From top left, clockwise: Hong Kong protests turn to widespread riots and civil disobedience; House of Representatives votes to adopt articles of impeachment against Donald Trump; CRISPR gene editing first used to experim ...

general elections. However, two separate East and West constituencies are proposed for the island under the 2022 review now under way.

The Isle of Wight is a ceremonial

A ceremony (, ) is a unified ritualistic event with a purpose, usually consisting of a number of artistic components, performed on a special occasion.

The word may be of Etruscan language, Etruscan origin, via the Latin ''Glossary of ancient Rom ...

and non-metropolitan county. Since the abolition of its two borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle Ag ...

councils and restructuring of the Isle of Wight County Council

Isle of Wight County Council was the county council of the non-metropolitan English county of the Isle of Wight from 1890 to 1995.

History

County councils were first introduced in England and Wales with full powers from 22 September 1889 as a re ...

into the new Isle of Wight Council

The Isle of Wight Council is a unitary authority covering the Isle of Wight, an island in the south of England. It is currently made up of 39 seats. Since the 2021 election, there has been an 'Alliance' coalition administration of Independents, ...

in 1995, it has been administered by a single unitary authority

A unitary authority is a local authority responsible for all local government functions within its area or performing additional functions that elsewhere are usually performed by a higher level of sub-national government or the national governmen ...

.

Elections in the constituency have traditionally been a battle between the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

and the Liberal Democrats. Andrew Turner of the Conservative Party gained the seat from Peter Brand of the Lib Dems at the 2001 general election. Since 2009, Turner was embroiled in controversy over his expenses, health, and relationships with colleagues, with local Conservatives having tried but failed to remove him in the runup to the 2015 general election. He stood down prior to the 2017 snap general election, and the new Conservative Party candidate Bob Seely

Robert William Henry Seely (born 1 June 1966) is a British Conservative Party politician who has served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for the Isle of Wight since June 2017. He was re-elected at the general election in December 2019 with an ...

was elected with a majority of 21,069 votes.

At the Isle of Wight Council

The Isle of Wight Council is a unitary authority covering the Isle of Wight, an island in the south of England. It is currently made up of 39 seats. Since the 2021 election, there has been an 'Alliance' coalition administration of Independents, ...

election of 2013, the Conservatives lost the majority which they had held since 2005 to the Island Independents

The Island Independents were a political group who stood as mutually-supporting independent candidates on the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom for the 2013 Isle of Wight Council election. The group won 15 of the 40 seats, emerging as the join ...

, with Island Independent councillors holding 16 of the 40 seats, and a further five councillors sitting as independents outside the group. The Conservatives regained control, winning 10 more seats and taking their total to 25 at the 2017 local election, before losing 7 seats in 2021

File:2021 collage V2.png, From top left, clockwise: the James Webb Space Telescope was launched in 2021; Protesters in Yangon, Myanmar following the 2021 Myanmar coup d'├®tat, coup d'├®tat; A civil demonstration against the OctoberŌĆōNovember 2021 ...

. A coalition entitled the Alliance Coalition was formed between independent, Green Party and Our Island councillors, with independent councillor Lora Peacey-Wilcox leading the council since May 2021.

There have been small regionalist movements: the Vectis National Party

The Vectis National Party was a minor political party operating on the Isle of Wight in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s. Formed in 1967,Adam Grydeh├Ėj and Philip Hayward"Autonomy Initiatives and Quintessential Englishness on the Isle of Wigh ...

and the Isle of Wight Party; but they have attracted little support at elections.

Geography

The Isle of Wight is situated between the Solent and the

The Isle of Wight is situated between the Solent and the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( J├©rriais), (Guern├®siais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, M├┤r Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

, is roughly rhomboid

Traditionally, in two-dimensional geometry, a rhomboid is a parallelogram in which adjacent sides are of unequal lengths and angles are non-right angled.

A parallelogram with sides of equal length (equilateral) is a rhombus but not a rhomboid.

...

in shape, and covers an area of . Slightly more than half, mainly in the west, is designated as the Isle of Wight Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The island has of farmland, of developed areas, and of coastline. Its landscapes are diverse, leading to its oft-quoted description as "England in miniature". In June 2019 the whole island was designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve

Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB) is an intergovernmental scientific program, launched in 1971 by UNESCO, that aims to establish a scientific basis for the improvement of relationships between people and their environments.

MAB's work engag ...

, recognising the sustainable relationships between its residents and the local environment.

West Wight is predominantly rural, with dramatic coastlines dominated by the chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk ...

downland

Downland, chalkland, chalk downs or just downs are areas of open chalk hills, such as the North Downs. This term is used to describe the characteristic landscape in southern England where chalk is exposed at the surface. The name "downs" is deriv ...

ridge, running across the whole island and ending in the Needles

The Needles is a row of three stacks of chalk that rise about out of the sea off the western extremity of the Isle of Wight in the English Channel, United Kingdom, close to Alum Bay and Scratchell's Bay, and part of Totland, the westernmo ...

stacks. The southwestern quarter is commonly referred to as the Back of the Wight

Back of the Wight is an area on the Isle of Wight in England. The area has a distinct historical and social background, and is geographically isolated by the chalk hills, immediately to the North, as well as poor public transport infrastructure. ...

, and has a unique character. The highest point on the island is St Boniface Down

St Boniface Down is a chalk down near Ventnor, on the Isle of Wight, England. Its summit, , is the highest point on the island, with views stretching from Beachy Head to the east, Portsmouth to the north and the Isle of Portland to the west. I ...

in the south east, which at is a marilyn. The most notable habitats on the rest of the island are probably the soft cliffs and sea ledges, which are scenic features, important for wildlife, and internationally protected.

The island has three principal rivers. The River Medina

The River Medina is the main river of the Isle of Wight, England, rising at St Catherine's Down near Chale, and flowing northwards through the county town Newport, towards the Solent at Cowes. The river is a navigable tidal estuary from Newpor ...

flows north into the Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit which projects into the Solent narrows the sea crossing between Hurst Castle and Colwell Bay to ...

, the Eastern Yar

The River Yar on the Isle of Wight, England, rises in a chalk coomb in St. Catherine's Down near Niton, close to the southern tip of the island. It flows across the Lower Cretaceous rocks of the eastern side of the island, through the gap ...

flows roughly northeast to Bembridge

Bembridge is a village and civil parish located on the easternmost point of the Isle of Wight. It had a population of 3,848 according to the 2001 census of the United Kingdom, leading to the implausible claim by some residents that Bembridge ...

Harbour, and the Western Yar

The River Yar on the Isle of Wight, England, rises near the beach at Freshwater Bay, on the south coast, and flows only a few miles north to Yarmouth where it meets the Solent. Most of the river is a tidal estuary. Its headwaters have been tru ...

flows the short distance from Freshwater Bay

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does include ...

to a relatively large estuary at Yarmouth

Yarmouth may refer to:

Places Canada

*Yarmouth County, Nova Scotia

**Yarmouth, Nova Scotia

**Municipality of the District of Yarmouth

**Yarmouth (provincial electoral district)

**Yarmouth (electoral district)

* Yarmouth Township, Ontario

*New ...

. Without human intervention the sea might well have split the island into three: at the west end where a bank of pebbles separates Freshwater Bay from the marsh

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found at ...

y backwaters of the Western Yar east of Freshwater, and at the east end where a thin strip of land separates Sandown Bay

Sandown Bay is a broad open bay which stretches for much of the length of the Isle of Wight's southeastern coast. It extends from Culver Down, near Yaverland in the northeast of the Island, to just south of Shanklin, near the village of Lucc ...

from the marshy Eastern Yar basin.

The Undercliff

The Undercliff is the name of several areas of landslide, landslip on the south coast of England. They include ones on the Isle of Wight; on the Dorset-Devon border near Lyme Regis; on cliffs near Branscombe in East Devon; and at White Nothe, Dors ...

between St Catherine's Point and Bonchurch

Bonchurch is a small village to the east of Ventnor, now largely connected to the latter by suburban development, on the southern part of the Isle of Wight, England. One of the oldest settlements on the Isle of Wight, it is situated on Undercliff ...

is the largest area of landslip morphology in western Europe.

The north coast is unusual in having four high tides each day, with a double high tide every twelve and a half hours. This arises because the western Solent is narrower than the eastern; the initial tide of water flowing from the west starts to ebb before the stronger flow around the south of the island returns through the eastern Solent to create a second high water.

Geology

The Isle of Wight is made up of a variety of rock types dating from earlyCretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of th ...

(around 127 million years ago) to the middle of the Palaeogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Pal├”ogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning o ...

(around 30 million years ago). The geological structure is dominated by a large monocline

A monocline (or, rarely, a monoform) is a step-like fold in rock strata consisting of a zone of steeper dip within an otherwise horizontal or gently-dipping sequence.

Formation

Monoclines may be formed in several different ways (see diagram)

* ...

which causes a marked change in age of strata from the northern younger Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the CretaceousŌĆōPaleogene extinction event, at the start ...

beds to the older Cretaceous beds of the south. This gives rise to a dip of almost 90 degrees in the chalk beds, seen best at the Needles

The Needles is a row of three stacks of chalk that rise about out of the sea off the western extremity of the Isle of Wight in the English Channel, United Kingdom, close to Alum Bay and Scratchell's Bay, and part of Totland, the westernmo ...

.

The northern half of the island is mainly composed of clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

s, with the southern half formed of the chalk

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk ...

of the central eastŌĆōwest downs, as well as Upper and Lower Greensand

Greensand or green sand is a sand or sandstone which has a greenish color. This term is specifically applied to shallow marine sediment that contains noticeable quantities of rounded greenish grains. These grains are called ''glauconies'' and c ...

s and Wealden strata. These strata continue west from the island across the Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit which projects into the Solent narrows the sea crossing between Hurst Castle and Colwell Bay to ...

into Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

, forming the basin of Poole Harbour

Poole Harbour is a large natural harbour in Dorset, southern England, with the town of Poole on its shores. The harbour is a drowned valley (ria) formed at the end of the last ice age and is the estuary of several rivers, the largest being th ...

(Tertiary) and the Isle of Purbeck

The Isle of Purbeck is a peninsula in Dorset, England. It is bordered by water on three sides: the English Channel to the south and east, where steep cliffs fall to the sea; and by the marshy lands of the River Frome and Poole Harbour to the n ...

(Cretaceous) respectively. The chalky ridges of Wight and Purbeck were a single formation before they were breached by waters from the River Frome during the last ice age, forming the Solent and turning Wight into an island. The Needles

The Needles is a row of three stacks of chalk that rise about out of the sea off the western extremity of the Isle of Wight in the English Channel, United Kingdom, close to Alum Bay and Scratchell's Bay, and part of Totland, the westernmo ...

, along with Old Harry Rocks

Old Harry Rocks are three chalk formations, including a stack and a stump, located at Handfast Point, on the Isle of Purbeck in Dorset, southern England. They mark the most eastern point of the Jurassic Coast, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

L ...

on Purbeck, represent the edges of this breach.

All the rocks found on the island are sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic matter, organic particles at Earth#Surface, Earth's surface, followed by cementation (geology), cementation. Sedimentati ...

, such as limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

s, mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from '' shale'' by its lack of fissility (parallel layering).Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology. ...

s and sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

s. They are rich in fossils; many can be seen exposed on beaches as the cliffs erode. Lignitic coal is present in small quantities within seams, and can be seen on the cliffs and shore at Whitecliff Bay

Whitecliff Bay is a sandy bay near Foreland which is the easternmost point of the Isle of Wight, England, about two miles south-west of Bembridge and just to the north of Culver Down. The bay has a shoreline of around and has a popular sandy ...

. Fossilised mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

s have been found there, and also on the northern coast along with fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

ised crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to inclu ...

s, turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked tu ...

s and mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

bones; the youngest date back to around 30 million years ago.

The island is one of the most important areas in Europe for dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s. The eroding cliffs often reveal previously hidden remains, particularly along the Back of the Wight

Back of the Wight is an area on the Isle of Wight in England. The area has a distinct historical and social background, and is geographically isolated by the chalk hills, immediately to the North, as well as poor public transport infrastructure. ...

. Dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

bones and fossilised footprints can be seen in and on the rocks exposed around the island's beaches, especially at Yaverland