Stanisław Horno-Popławski on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stanisław Horno-Popławski (1902-1997) was a Russian-Polish painter,

In 1949, he moved to Sopot then Gdańsk at the Academy of Fine Arts, where he even served in the position of the

In 1949, he moved to Sopot then Gdańsk at the Academy of Fine Arts, where he even served in the position of the

* Jan Popławski (russian: Иван Иванович Поплавский) (1859–1935), a doctor of medical sciences in internal and nervous diseases. In 1900, he was the head of the medical unit for the mentally ill at the " Saint Nicholas hospital" together with the chief physician Otton Czeczott.

During 5 months they hid

* Jan Popławski (russian: Иван Иванович Поплавский) (1859–1935), a doctor of medical sciences in internal and nervous diseases. In 1900, he was the head of the medical unit for the mentally ill at the " Saint Nicholas hospital" together with the chief physician Otton Czeczott.

During 5 months they hid

* Biała głowa ("White head") (1980)

* Monument to

* Biała głowa ("White head") (1980)

* Monument to

File:Palaimintųjų relikvijų koplyčia 6.jpg, Monument to bishop Władysław Bandurski in the

Horno-Popławski on the Polish site culture.pl

*

Bydgoszcz Art Centre

sculptor

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

and pedagogue

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken a ...

.

Life

Stanisław's mother was Maria-Natalie-Agripina Popłavskaya (russian: Мария-Натали-Агрипина Поплавская), née Czeczott (1869-1935). In March 1891, she married Bartłomiej Józef Popławski (1861-1931) a Russian-Polishrailway engineer

Railway engineering is a multi-faceted engineering discipline dealing with the design, construction and operation of all types of rail transport systems. It encompasses a wide range of engineering disciplines, including civil engineering, compu ...

(1861-1931) who later became president of the Warsaw Shipping and Trade Society. Bartłomiej had just been transferred the same year to Crimea (then part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

), due to poor health and was involved in the construction of the Feodosia-Dzhankoy railway line (1891-1895). A year later in Feodosia

uk, Феодосія, Теодосія crh, Kefe

, official_name = ()

, settlement_type=

, image_skyline = THEODOSIA 01.jpg

, imagesize = 250px

, image_caption = Genoese fortress of Caffa

, image_shield = Fe ...

, they had a daughter Maria Yadviga (1892-1930s). Stanisław was born on July 14, 1902, in Kutaisi, Georgia, then part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

.

In 1908, the family left Georgia for Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

where the young Stanisław began his art studies in the late 1910s. While visiting museums and galleries in the Russian capital, he was fascinated by painting. In 1921, Stanisław lived briefly in Vilnius, but soon they transferred from Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

to motherland Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

in 1922.

In Warsaw, he resumed his education from 1923 to 1931, at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts under the tutoring

Tutoring is private academic support, usually provided by an expert teacher; someone with deep knowledge or defined expertise in a particular subject or set of subjects.

A tutor, formally also called an academic tutor, is a person who provides ...

of Tadeusz Pruszkowski

Tadeusz Pruszkowski (15 April 1888 – 30 June 1942) was a Polish painter and art teacher, known primarily for his portraits.

Biography

He began his artistic studies in 1904 at the , under Konrad Krzyżanowski.

and Tadeusz Breyer

Tadeusz Breyer (15 October 1874 in Mielec – 15 May 1952 in Warsaw) - Polish sculptor and medallic artist. He studied at the School of Fine Arts in Kraków. Then, he left for the Academy in Florence. In 1904 he moved to Warsaw. From 1910 to ...

. After graduation, he traveled to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

.

In 1931, Horno-Popławski began his teaching career at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Stephen Báthory

Stephen Báthory ( hu, Báthory István; pl, Stefan Batory; ; 27 September 1533 – 12 December 1586) was Voivode of Transylvania (1571–1576), Prince of Transylvania (1576–1586), King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1576–1586) ...

University in Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

, today's part of the Vilnius University. He was a member of several associations:

* the Association of Polish Visual Artists with its periodical official publication "Forma", led by Władysław Strzemiński;

* the Vilnius Society of Plastic Artists

* the Warsaw Trade Union of Artists and Sculptors.

In 1935, her mother Maria died in Italy. She was buried in the family vault in the Powązki Cemetery

Powązki Cemetery (; pl, Cmentarz Powązkowski), also known as Stare Powązki ( en, Old Powązki), is a historic necropolis located in Wola district, in the western part of Warsaw, Poland. It is the most famous cemetery in the city and one of t ...

in Warsaw, together with her husband, who died four years earlier.

Stanisław took part to the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

from its beginning in September 1939 and got captured. He spent the rest of the conflict in the POW camp for Polish officers "Oflag II-C" located in Woldenberg (today Dobiegniew

Dobiegniew (german: Woldenberg) is a town in western Poland, in Lubusz Voivodeship, in Strzelce-Drezdenko County. As of December 2021, the town has 3,004 inhabitants.

History

The area formed part of Greater Poland in Piast-ruled Poland. The set ...

, Lubusz Voivodeship

Lubusz Voivodeship, or Lubuskie Province ( pl, województwo lubuskie ), is a voivodeship (province) in western Poland.

It was created on January 1, 1999, out of the former Gorzów Wielkopolski and Zielona Góra Voivodeships, pursuant to the Po ...

). During his detention, he realized several religious

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

statues placed in the camp chapel.

A the end of the war, once released from the POW camp, he worked for a year as a professor at the School of Fine Arts of Białystok. It is in the city that he found back his wife and his children he was separated from since 1939.

From 1946 to 1949, he was a teacher at the Faculty of Fine Arts of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń

Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń or NCU ( pl, Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu, UMK) is located in Toruń, Poland. It is named after Nicolaus Copernicus, who was born in Toruń in 1473.Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

in Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

.

In 1949, he moved to Sopot then Gdańsk at the Academy of Fine Arts, where he even served in the position of the

In 1949, he moved to Sopot then Gdańsk at the Academy of Fine Arts, where he even served in the position of the Dean

Dean may refer to:

People

* Dean (given name)

* Dean (surname), a surname of Anglo-Saxon English origin

* Dean (South Korean singer), a stage name for singer Kwon Hyuk

* Dean Delannoit, a Belgian singer most known by the mononym Dean

Titles

* ...

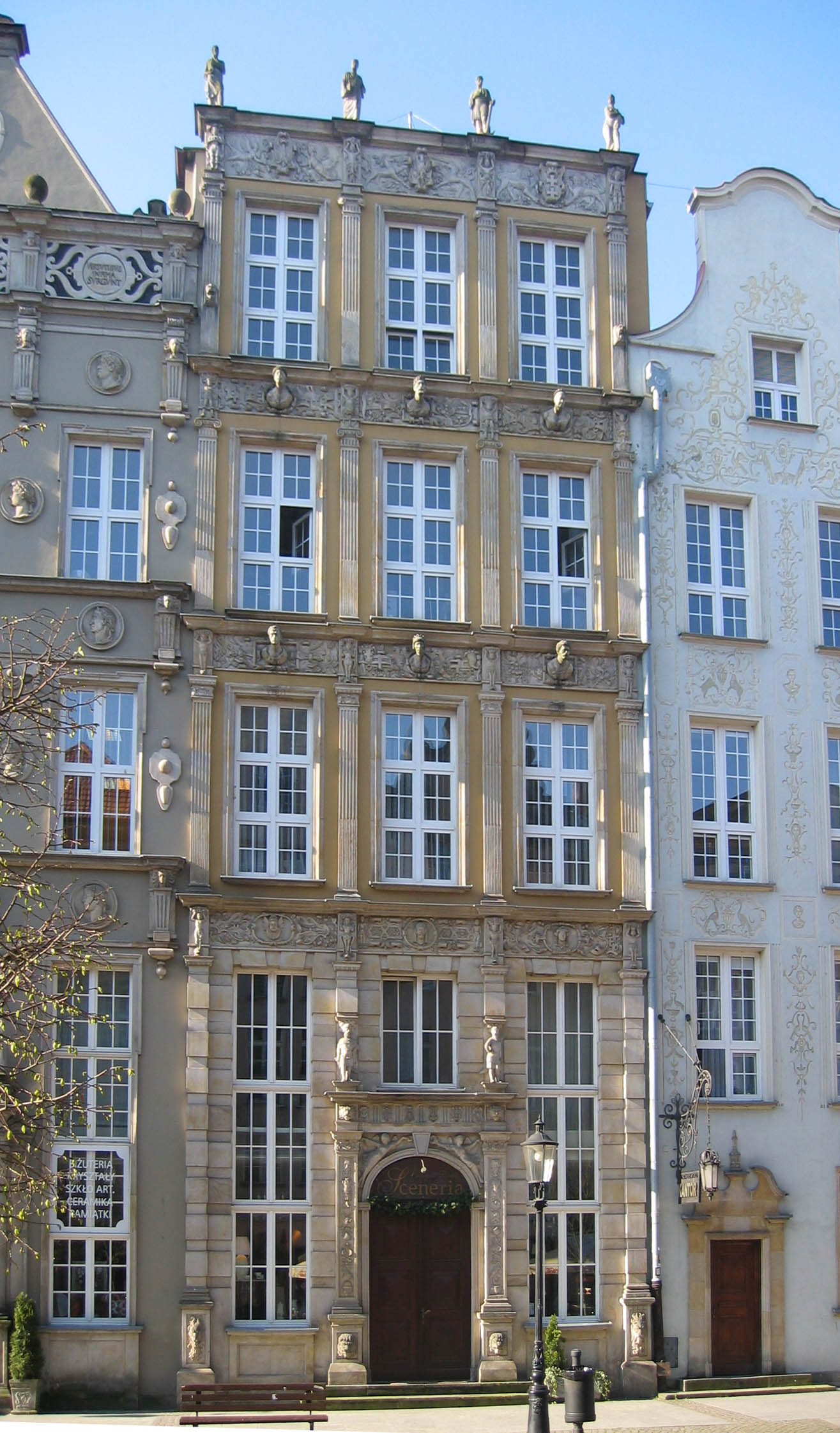

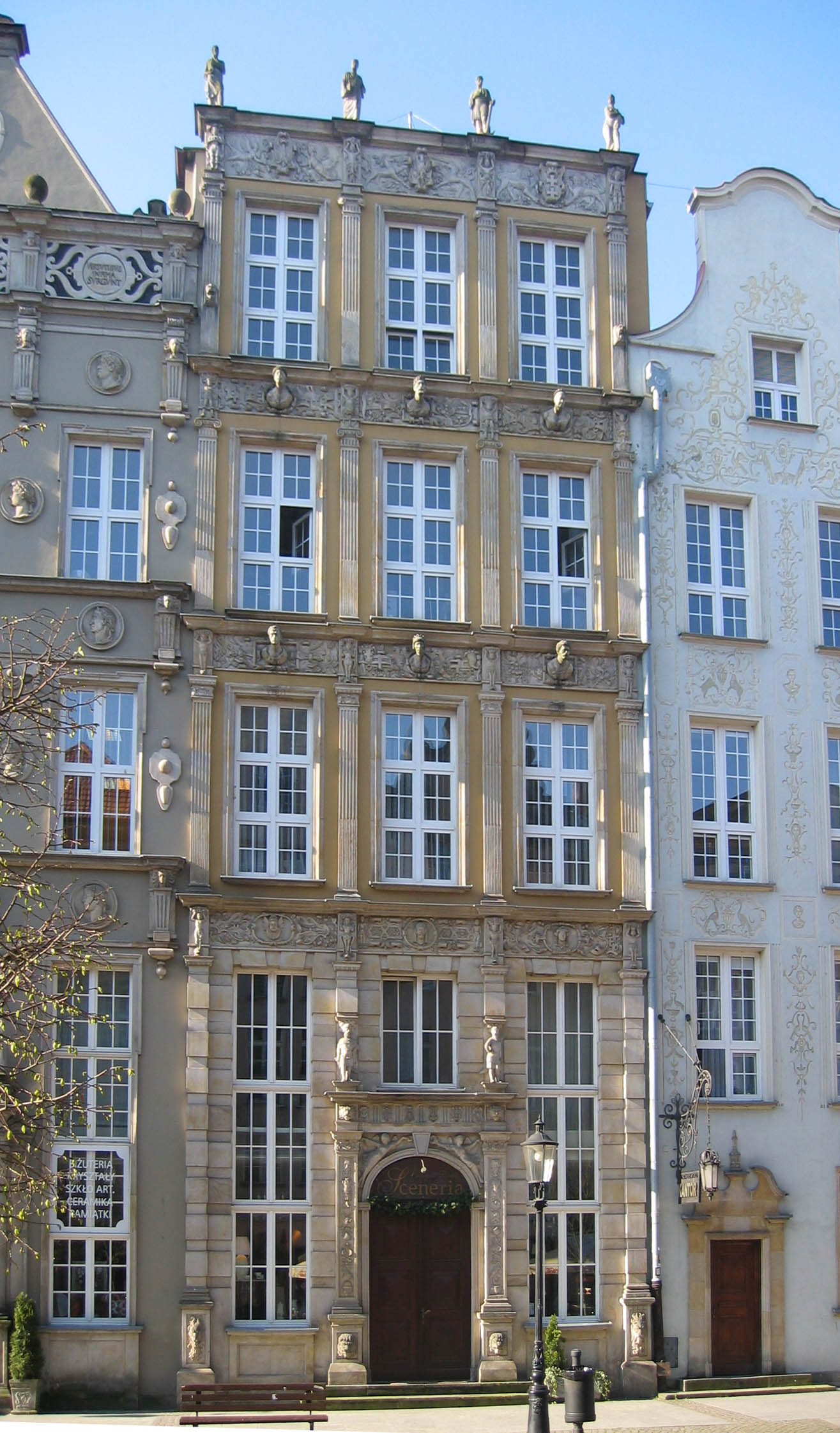

of the Faculty of Sculpture in 1949-1950 and in 1956–1960. Between 1951 and 1954, Stanisław was the main expert in the reconstruction project of the Old Town of Gdańsk, designing houses and sculptural decorations.

He worked more particularly on:

* the ''Ferber House'' at 28 Długa street;

* the house at 38 Długa street;

* the tenement details at 43 Długi Targ square.

The artist's face can be found on the keystone of the vaulted afacade at 1 Pończoszników street.

He took part in exhibitions of National Fine Arts in Warsaw and received a number of high awards in the field of sculpture. In 1952, he took part in the soviet sponsored exhibition "100 Years of Realism in Poland" (russian: 100 лет "реализма" в Польше) in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

.

As an outcome of a 1954 competition, he was granted the realization of a monument to Adam Mickiewicz placed in 1955 in the front yard of the "Palace of Culture and Science" in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

.

At the end of the 1950s, inspired by archaic Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Etruscan sculptures __NOTOC__

Etruscan may refer to:

Ancient civilization

*The Etruscan language, an extinct language in ancient Italy

*Something derived from or related to the Etruscan civilization

**Etruscan architecture

**Etruscan art

**Etruscan cities

**Etruscan ...

, Horno-Popławski undertook new formal searches using the expression of natural shapes of "fieldstones", which gave him a high position among the 20th century sculptors.

Stanisław's works, during the post-war years, were exhibited in Poland, in Europe (Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), ma ...

(1961), Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

(1971), Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

(1972), Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population ...

and Essen (1974)), as well as in Asia (New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament Ho ...

, Kolkata

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, comme ...

, Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

, Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

). He won recognition for his merits in favour of the Polish Culture (1962, 1965, 1995) and was even awarded a gold medal at the "Contemporary Art Biennale" in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

in 1969. He made two trips to his Georgian roots (1967, 1978), where two of his works are displayed ( Kutaisi State Historical Museum and Niko Pirosmani Museum in Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million p ...

).

From 1979 to 1983, thanks to Marian Turwid's suggestion, the sculptor moved to a small house in the botanical garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens, an ...

of Bydgoszcz, looking for a city "whose character guarantees the possibility of quiet creative work, and whose atmosphere is devoid of nervous hustle and bustle, which absorbs and disturbs focused actions". On July 22 of this year, then the official holiday in the Polish People's Republic

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million ne ...

, Horno-Popławski opened in the city garden an open-air gallery of his compositions, which he donated. The collection included the following works: "Partisan", "Memories of Bagrati", "Morena", "Copernicus", "Tadeusz Breyer", "Tehura", "Gruzinka", "Waiting", "Szota Rustawelli", "Colchida", "Żal", "Pogodna", "Beethoven" and "Hair". Unfortunately, most of these works have been stolen.

After this spell in Bydgoszcz, Stanisław moved back to Sopot where he had his atelier

An atelier () is the private workshop or studio of a professional artist in the fine or decorative arts or an architect, where a principal master and a number of assistants, students, and apprentices can work together producing fine art or ...

set up near the Grand Hotel A grand hotel is a large and luxurious hotel, especially one housed in a building with traditional architectural style. It began to flourish in the 1800s in Europe and North America.

Grand Hotel may refer to:

Hotels Africa

* Grande Hotel Beir ...

.

Hi was married to P. Inga Stanisława, a sculptor as well. They had several children, among whom a daughter, P. Jolanta Ronczewska who married in 1960 Polish actor Ryszard Ronczewski

Ryszard Ronczewski (27 June 1930 – 17 October 2020) was a Polish actor.

He appeared in more than seventy films from 1954 to 2021 (the premiere of '' The Wedding'' occurred a few months after his death).

Ronczewski died from COVID-19 on 17 Octo ...

.

Stanisław Horno-Popławski died on June 6, 1997, in Sopot

Sopot is a seaside resort city in Pomerelia on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea in northern Poland, with a population of approximately 40,000. It is located in Pomeranian Voivodeship, and has the status of the county, being the smallest ci ...

.

Family

Popławski branch

* Bartłomiej Józef Popławski (russian: Варфоломей-Иосиф Иванович Поплавский ), Stanisław's father, was born in 1861 in Chita,: his grandfather, a Polish noble, had been exiled to a hard labor settlement inSiberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

for having participated in January Uprising. Graduated in 1887 as an engineer from the St. Petersburg State Transport University

Emperor Alexander I St. Petersburg State Transport University (PGUPS) (russian: Петербургский государственный университет путей сообщения Императора Александра I, abbreviat ...

, he worked for ten years on the construction of many railway lines in Russian Siberia (Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

, Chinese-Eastern Railway). He was then posted until 1914 as the manager of the "Society of Warsaw Access Railways" and "Director of the Warsaw Society of Shipping and Trade"; as such, he directed the construction of the narrow-gauge railway from "Warszawa Most" to Jabłonna II (1898). At the end of WWI

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, he returned to Warsaw with his family. He died there on July 4, 1931.

* Stanisław's grandfather, Ivan Varfolomeevich Popławski (1822-1893) (russian: Иван Варфоломеевич Поплавский), was the vice-governor of the Transbaikal

Transbaikal, Trans-Baikal, Transbaikalia ( rus, Забайка́лье, r=Zabaykalye, p=zəbɐjˈkalʲjɪ), or Dauria (, ''Dauriya'') is a mountainous region to the east of or "beyond" (trans-) Lake Baikal in Far Eastern Russia.

The steppe and ...

region, a member of the Irkutsk City Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

. He died on October 31, 1893, in St. Petersburg.

* Stanisław's grandmother, Yadviga Iosifovna Poplavskaya (russian: Ядвига Иосифовна Поплавская), née Ventskovskaya (russian: Венцковская) (1837-1924), was a Polish noblewoman, owner of a tea plantation in Gudauta

Gudauta ( ka, გუდაუთა, ; ab, Гәдоуҭа, ''Gwdowtha''; russian: Гудаута, ''Gudauta'') is a town in Abkhazia, Georgia, and a centre of the eponymous district. It is situated on the Black Sea, 37 km northwest of Sukhu ...

, Georgia, and of a match factory, "Sun" ("Солнце") in Chudovo

Chudovo (russian: Чудово) is the name of several inhabited localities in Russia.

;Urban localities

*Chudovo, Chudovsky District, Novgorod Oblast, a town of district significance in Chudovsky District of Novgorod Oblast

;Rural localities

* ...

, Novgorod province. Together with Ivan, they had 7 children.

Stanisław's uncles were:

* Jan Popławski (russian: Иван Иванович Поплавский) (1859–1935), a doctor of medical sciences in internal and nervous diseases. In 1900, he was the head of the medical unit for the mentally ill at the " Saint Nicholas hospital" together with the chief physician Otton Czeczott.

During 5 months they hid

* Jan Popławski (russian: Иван Иванович Поплавский) (1859–1935), a doctor of medical sciences in internal and nervous diseases. In 1900, he was the head of the medical unit for the mentally ill at the " Saint Nicholas hospital" together with the chief physician Otton Czeczott.

During 5 months they hid Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Naczelnik państwa, Chief of State (1918–1922) and Marshal of Poland, First Marshal of Second Polish Republic, Poland (from 1920). He was ...

(1867–1935) feigning mental illness, who has been sent for a medical examination after his arrest in Łódź

Łódź, also rendered in English as Lodz, is a city in central Poland and a former industrial centre. It is the capital of Łódź Voivodeship, and is located approximately south-west of Warsaw. The city's coat of arms is an example of cant ...

. Using their official positions, Jan, together with other physicians ( Władysław Mazurkiewicz, Aleksander Sulkiewicz

Iskander Mirza Huzman Beg Sulkiewicz (8 December 1867 – 18 September 1916), known as Aleksander Sulkiewicz, was a Polish people, Polish politician of Lipka Tatars, Lipka Tatar ethnicity who campaigned for Polish independence and co-founded the Po ...

and others) helped Piłsudski to escape to Galicia. After this action, Popławski had to leave his post: he then took up a private practice as a physician. Jan enlarged successfully the art collection started by his father. His gathering was focused on Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

painting and the Italian Quattrocento

The cultural and artistic events of Italy during the period 1400 to 1499 are collectively referred to as the Quattrocento (, , ) from the Italian word for the number 400, in turn from , which is Italian for the year 1400. The Quattrocento encom ...

. In 1924, at the personal invitation of Józef Piłsudski, Jan left Leningrad at the age of 65 for Warsaw to attend his seriously ill brother Bartholomew-Joseph, and stayed there. Popławski's collection is today the pride of the National Museum in Warsaw

The National Museum in Warsaw ( pl, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie), popularly abbreviated as MNW, is a national museum in Warsaw, one of the largest museums in Poland and the largest in the capital. It comprises a rich collection of ancient art ( Eg ...

, including, among others, works from Rubens, Van Dyck

Sir Anthony van Dyck (, many variant spellings; 22 March 1599 – 9 December 1641) was a Brabantian Flemish Baroque artist who became the leading court painter in England after success in the Southern Netherlands and Italy.

The seventh ...

, Rembrandt, Tintoretto

Tintoretto ( , , ; born Jacopo Robusti; late September or early October 1518Bernari and de Vecchi 1970, p. 83.31 May 1594) was an Italian painter identified with the Venetian school. His contemporaries both admired and criticized the speed wit ...

, Jordaens or Jan Steen

Jan Havickszoon Steen (c. 1626 – buried 3 February 1679) was a Dutch Golden Age painter, one of the leading genre painters of the 17th century. His works are known for their psychological insight, sense of humour and abundance of colour.

Lif ...

. Widowed in 1933, Jan moved to a rented apartment at 16 Chłodna street in Warsaw, where his private medical practice received a large high-ranking clientele, in particular Józef Piłsudski. He died in his flat in 1935.

* Iosif Ivanovich Popławski (1865–1943), a lawyer, legal representative of the Board of the Joint Stock Company of the Chinese Eastern Railway

The Chinese Eastern Railway or CER (, russian: Китайско-Восточная железная дорога, or , ''Kitaysko-Vostochnaya Zheleznaya Doroga'' or ''KVZhD''), is the historical name for a railway system in Northeast China (als ...

and director of the family match factory "Солнце" in Chudovo. He died in 1943 in USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

Czeczott branch

* Stanisław's mother, Maria-Natalie-Agripina Popłavskaya (russian: Мария-Натали-Агрипина Поплавская), was the daughter of Otton Czeczott (russian: Оттон Чечотт), a famous Russian-Polish psychiatrist, professor atSaint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

's Psychoneurological Institute. Maria was an artist and a sculptor. In her youth, she took painting lessons from Ivan Aivazovsky

Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky (russian: link=no, Иван Константинович Айвазовский; 29 July 18172 May 1900) was a Russian Romantic painter who is considered one of the greatest masters of marine art. Baptized ...

one of the greatest master painters of marine art

Marine art or maritime art is a form of figurative art (that is, painting, drawing, printmaking and sculpture) that portrays or draws its main inspiration from the sea. Maritime painting is a genre that depicts ships and the sea—a genre parti ...

.

* Stanisław's grandfather was the psychiatrist Otton Dionizy Antoni Czeczott (russian: Оттон Антонович Чечотт (1842-1924). Coming from a noble family of Mogilev

Mogilev (russian: Могилёв, Mogilyov, ; yi, מאָלעוו, Molev, ) or Mahilyow ( be, Магілёў, Mahilioŭ, ) is a city in eastern Belarus, on the Dnieper River, about from the border with Russia's Smolensk Oblast and from the bor ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

(today's Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

), he graduated from the "Imperial Medical-Surgical Academy" of Saint-Petersburg in 1866. From 1881 to 1901, he was a senior and then chief doctor of the " Saint Nicholas hospital". He left his position after Józef Piłsudski's escaping from his institution. In 1922, adopting Polish citizenship, he emigrated with his family to Poland. He died on October 8, 1924, and was buried in the Powązki Cemetery

Powązki Cemetery (; pl, Cmentarz Powązkowski), also known as Stare Powązki ( en, Old Powązki), is a historic necropolis located in Wola district, in the western part of Warsaw, Poland. It is the most famous cemetery in the city and one of t ...

in Warsaw.

Stanisław's uncles were:

* Henryk Czeczott (russian: Генрих Оттонович Чечотт) (1875–1928), an engineer graduated from the Saint Petersburg Mining University

Saint Petersburg Mining University (russian: Санкт-Петербургский горный университет), is Russia's oldest technical university, and one of the oldest technical colleges in Europe. It was founded on October 21, ...

in 1900. In 1914, he was sent to the US to study the senior course of the enrichment department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

under the lead of Robert Hallowell Richards

Robert Hallowell Richards (August 26, 1844 – March 27, 1945) was an American mining engineer, metallurgist, and educator, born at Gardiner, Maine.

In 1868, with the first class to leave the institution, he graduated from the Massachusetts ...

. He set up a gold mine in the Altai Mountains and managed it until the nationalization in 1918. On his initiative, Russia's first department of mineral processing was established at the Mining Institute, which after October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

, was transformed into the "Institute of Mechanical Processing of Mineral Resources" (russian: Механобр) under his direction. In 1922, he moved to Poland, where he became a professor at the Krakow Mining Academy. In 1928, during a scientific trip to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, he died on June 6, 1928, in Freiberg

Freiberg is a university and former mining town in Saxony, Germany. It is a so-called ''Große Kreisstadt'' (large county town) and the administrative centre of Mittelsachsen district.

Its historic town centre has been placed under heritage c ...

from blood poisoning. His body was transported back to Poland and buried at the Evangelical Cemetery in Warsaw.

* Albert Czeczott (russian: Альберт Оттонович Чечотт) (1873–1955), graduated in 1897, from the "Saint Petersburg Institute of Railway Engineers", where in 1914, he became a professor. After the October Revolution and the following Civil War, he emigrated in 1922, to live in Poland. From 1927 onwards, he taught at the Warsaw Polytechnic Institute and in 1928 he worked also at the Polish Ministry of Railways. In 1933, he supervised the construction of a measuring laboratory in Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

for the study of locomotives. From 1934 to 1937, he worked in Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

at the construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway

The Trans-Iranian Railway ( fa, راهآهن سراسری ایران) was a major railway building project started in Pahlavi Iran in 1927 and completed in 1938, under the direction of the then-Iranian monarch Reza Shah. It was entirely built ...

. During the German occupation

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

, he was engaged in theoretical work at home. Soon after the liberation of Warsaw by Soviet troops, on February 6, 1945, he resumed his work at the Ministry. In 1951, he moved to the newly created Railway Institute, where he organized a laboratory on flue gas

Flue gas is the gas exiting to the atmosphere via a flue, which is a pipe or channel for conveying exhaust gases from a fireplace, oven, furnace, boiler or steam generator. Quite often, the flue gas refers to the combustion exhaust gas produc ...

and steam traction. He died on November 3, 1955, in Warsaw.

Recognition

Initially, Horno-Popławski's works were following realistic convention. In the last years of his life, he progressively drifted away from the classical line towards compositions realized from slightly worked rough stones. He was going to his studio every day, it was like his factory work. In this way, he did not have to wait for a sudden surge of creative energy. His works are now scattered in may Polish cities. Popławski's works keep to draw attention. In April 2005, an exhibition was held in the "Exhibition Hall" of Moscow titled "Stanislav Horno-Popławski. The road of art - the art of the road." The display included more than 50 sculptures of the artist loaned from Polish museums, among which the National Museums ofWarsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

, Szczecin or Gdańsk. The exhibit covered works from the 1950s to the 1970s, up to the last ones created in the 1980s-1990s, in particular pieces from his cycle "The Dream of a Stone" ( pl, Sen Kamienia).

This cycle is rated as "oneiric, intuitively archetypal, symbolic" representing "metacultural female heads, which he developed until the last days of his life.", as expressed by dr. Dorota Grubba-Thiede, from the Academy of Fine Art Gdańsk, during a lecture performed for the Art Centre of Bydgoszcz ( pl, Bydgoskie Centrum Sztuki) on June 6, 2020.

Dr. Dorota Grubba-Thiede had the honor to meet the artist in Sopot in 1997. From this conversation stemmed an album- monograph edited by prof. Jerzy Malinowski with the cooperation of the sculptor's family, entitled ''Stanisław Horno-Popławski (1902-1997) - The Way of Art - The Art of the Way'', published in 2002 by the State Art Gallery of Sopot.

On July 22, 1952, by decision of the President of the Republic of Poland

The president of Poland ( pl, Prezydent RP), officially the president of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Prezydent Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), is the head of state of Poland. Their rights and obligations are determined in the Constitution of Polan ...

, the artist was awarded was awarded the Golden Cross of Merit ( pl, Złoty Krzyż Zasługi) for his works in the field of culture and art.

In 1953 he was awarded the State Award Badge, 2nd echelon.

In 1996, Horno-Popławski was promoted ''doctor honoris causa'' of the University in Toruń, UMK of Toruń.

On April 25, 1997, Horno-Popławski was awarded the title of ''doctor honoris causa'' from the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk.

In 2004, the Sopot exhibition „Stanisław Horno-Popławski. Droga sztuki- sztuka drogi” traveled to Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

and Odessa.

Commemorative plaques to his memory have been unveiled in 2005 ( Gdańsk) and 2011 (Sopot

Sopot is a seaside resort city in Pomerelia on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea in northern Poland, with a population of approximately 40,000. It is located in Pomeranian Voivodeship, and has the status of the county, being the smallest ci ...

).

In 2017, the newly open Bydgoszcz Art Centre ( pl, Bydgoskie Centrum Sztuki) has taken as patron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

name "Horno-Popławski". The gallery at 47 Jagiellońska street has organized an exhibition on the artist in February–March 2020.

Notable works

His works can be seen in many museums in Poland and around the world (e.g.Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

, Bydgoszcz, Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

, Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million p ...

). Furthermore, many other works are in the hands of private collectors in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

or Japan.

* Portrait of Antosię from Kalin (1928)

One of the first piece of art realized by Horno-Popławski. It was last seen in an exhibition at the Branicki Palace of Białystok after WWII

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

* Hadasa, Tehura (1930s, 1960s)

* Biała głowa ("White head") (1980)

* Monument to

* Biała głowa ("White head") (1980)

* Monument to bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is c ...

Władysław Bandurski in the cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the '' cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominatio ...

crypt of Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

(1938)

* Altar statues at the Church of Jesus the Redeemer, Vilnius in Antakalnis

Antakalnis (''literally'' lt, 'the place on hills', adapted in pl, Antokol) is an eldership in the Vilnius city municipality, Lithuania. Antakalnis is one of the oldest, and largest historical suburbs of Vilnius City. It is in the eastern se ...

, near Vilnius (1933-1934)

* Sculpture ensemble ''Praczki'' (" Washerwomen") in Białystok (1938)

The work was created in Toruń

)''

, image_skyline =

, image_caption =

, image_flag = POL Toruń flag.svg

, image_shield = POL Toruń COA.svg

, nickname = City of Angels, Gingerbread city, Copernicus Town

, pushpin_map = Kuyavian-Pom ...

in 1938, commissioned by the then Białystok Voivodeship: it is the only profane work of Stanisław Horno-Popławski in the city.

In 1945, it was placed over one of the ponds of the "Planty Park".

In 1978, the monument was restored, cleaned and patched with cement. In 1992, the sculpture was placed in the "Voivodeship Heritage list of Monuments". In 2000, the head of one of the statue was broken and quickly repaired. In March 2003, the monument was devastated again: one of the three figures was halved. In July 2003, the sculpture was restored anew. A scale reproduction of "Praczki" is present in one of Gdańsk museums.

* Statues at St. Roch's Church in Białystok (late 1940s)

Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

at the main altar, Mother of God with Child at the side altar and Christ the Good Shepherd outside the church.

* Monument to Adam Mickiewicz

Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (; 24 December 179826 November 1855) was a Polish poet, dramatist, essayist, publicist, translator and political activist. He is regarded as national poet in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. A principal figure in Polish Ro ...

in front of the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw (1955)

* "Kutno" (1967)

* "Maria Konopnicka na ławce" (1968)

* Monument to Henryk Sienkiewicz in Bydgoszcz (1968)

The original monument dates back to 1927, the first elevated to Sienkiewicz in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. It was funded via a Committee composed of teachers and cultural activists of Bydgoszcz, led by Witold Bełza. The initial statue was made out of bronze by the artist Konstanty Laszczka

Konstanty Laszczka (born 3 September 1865 in Makowiec Duży; died 23 March 1956 in Kraków) was a Polish sculptor, painter, graphic artist, as well as professor and rector of the Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków. Laszczka became the ...

. The official unveiling happened on July 31, 1927, by the President of Poland, Ignacy Mościcki. The statue was destroyed by the Nazis in the first days of the occupation, in September 1939.

The new monument, made of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies under ...

by Horno-Popławski is located on the very site of its predecessor, in today's Jan Kochanowski Park. The unveiling ceremony took place on May 18, 1968.

* Monument to Maria Konopnicka

Maria Konopnicka (; ; 23 May 1842 – 8 October 1910) was a Polish poet, novelist, children's writer, translator, journalist, critic, and activist for women's rights and for Polish independence. She used pseudonyms, including ''Jan Sawa''. She ...

in Kalisz

(The oldest city of Poland)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = ''Top:'' Town Hall, Former "Calisia" Piano Factory''Middle:'' Courthouse, "Gołębnik" tenement''Bottom:'' Aerial view of the Kalisz Old Town

, image_flag = POL Kalisz flag.svg ...

(1969)

* Monument to Karol Szymanowski in Słupsk

Słupsk (; , ; formerly german: Stolp, ; also known by several alternative names) is a city with powiat rights located on the Słupia River in the Pomeranian Voivodeship in northern Poland, in the historical region of Pomerania or more specific ...

(1972)

* Monument to Jan Kiliński

Jan Kiliński (1760 in Trzemeszno - 28 January 1819 in Warsaw) was a Polish soldier and one of the commanders of the Kościuszko Uprising. A shoemaker by trade, he commanded the Warsaw Uprising of 1794 against the Russian garrison stationed in W ...

in Słupsk (1973)

The statue of Jan Kiliński was funded by the "Słupsk Craft

A craft or trade is a pastime or an occupation that requires particular skills and knowledge of skilled work. In a historical sense, particularly the Middle Ages and earlier, the term is usually applied to people occupied in small scale pro ...

smanship association". The monument is made of stone and represents one of the leaders of the Kościuszko Uprising on a pedestal, by the riverside boulevard over the Słupia River, in the vicinity of the local seat of the Craft Guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

.

* Monument to Julian Marchlewski

Julian Baltazar Józef Marchlewski (17 May 1866 – 22 March 1925) was a Polish communist politician, revolutionary activist and publicist who served as chairman of the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee. He was also known under the al ...

in Włocławek

Włocławek (Polish pronunciation: ; german: Leslau) is a city located in central Poland along the Vistula (Wisła) River and is bordered by the Gostynin-Włocławek Landscape Park. As of December 2021, the population of the city is 106,928. Loc ...

1964)

Julian Marchlewski was born in Włocławek in 1866. The unveiling of Horno-Popławski's monument occurred on May 1, 1964, with the participation of Zofia, Marchlewski's daughter. Built of granite, the five-meter-high monument was in the socialist realist style. On the pedestal was an inscription "To Julian Marchlewski, the Great Internationale Patriot, Society of Włocławek and Bydgoszcz. May 1, 1964".

On January 26, 1990, as part of the decommunization

Decommunization is the process of dismantling the legacies of communist state establishments, culture, and psychology in the post-communist countries. It is sometimes referred to as political cleansing. Although the term has been occasionally ...

, the statue was dismantled and moved to the nearby Bojańczyk brewery. On June 9, 1999, the figure without its pedestal was transferred to the Zamoyski Palace

Zamoyski Palace (Polish: ''Pałac Zamoyskich'') - a historical building, located by Nowy Świat Street in Warsaw, Poland.

From 1667 the owner of the plot was Jan Wielopolski. Between 1744 and 1745 the inheritors of Wielopolski's possessions reco ...

in Kozłówka and joined the Art Gallery of Socialism. The inscription plaque is still in the storage of the Włocławek Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń lands ( pl, Muzeum Ziemi Kujawskiej i Dobrzyńskiej we Włocławku).

* Design of the monument to the Unknown Greater Poland Insurgent in Bydgoszcz (1986)

Unveiled on December 29, 1986, on the 68th anniversary of the Greater Poland Uprising, it is set up at the very place where originally stood the tomb containing the ashes of an unknown insurgent who died in June 1919. It was razed during WWII

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

The current monument, based on a design by Horno-Popławski, has been realized and cast by Aleksander Dętkoś, one of his student from Bydgoszcz.

Gallery

Vilnius Cathedral

The Cathedral Basilica of St Stanislaus and St Ladislaus of Vilnius ( lt, Vilniaus Šv. Stanislovo ir Šv. Vladislovo arkikatedra bazilika; pl, Bazylika archikatedralna św. Stanisława Biskupa i św. Władysława, historical: ''Kościół Kated ...

crypt (1938)

File:Kosciol Sw Rocha Bialystok Christ main altar.jpg, Christ, main altar, St. Roch's Church, Białystok (late 1940s)

File:Białystok kościół św. Rocha 05.jpg, Mother of God with Child, side altar, St. Roch's Church, Białystok (late 1940s)

File:Białystok, zespół kościoła św. Rocha, 1927-1946 42.jpg, Christ the Good Shepherd, St. Roch's Church, Białystok (late 1940s)

File:Bdg pomnikSienkiewicza 07-2013.jpg, Monument to Henryk Sienkiewicz, Bydgoszcz (1968)

File:Konopnicka Kalisz Horno-Popławski.jpg, Monument to Maria Konopnicka, Kalisz (1969)

File:Szymanowski slupsk.JPG, Monument to Karol Szymanowski, Słupsk (1972)

File:Pomnik Jana Kilińskiego w Słupsku.jpg, Monument to Jan Kiliński, Słupsk (1972)

File:Julian MaechlewskizWloclawka.jpg, Monument to Julian Marchlewski, Zamoyski Palace in Kozłówka (1964)

File:Horno poplawski sculpt.jpg, Sculpture in the Botanic Garden of Bydgoszcz (early 1980s)

File:Park Oliwski – rzeźba Tors.JPG, Torso, Park Oliwski

See also

*Palace of Culture and Science

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence, or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word is derived from the Latin name palātium, for Palatine Hill in Rome which ...

* Gdańsk

* Botanic Garden of Casimir the Great University, Bydgoszcz

The Botanic Garden of Casimir the Great University is located in the center of Bydgoszcz, close to the main campus of the Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz ( pl, Uniwersytet Kazimierza Wielkiego w Bydgoszczy-UKW). The facility fulfils ...

* Vilnius University

Vilnius University ( lt, Vilniaus universitetas) is a public research university, oldest in the Baltic states and in Northern Europe outside the United Kingdom (or 6th overall following foundations of Oxford, Cambridge, St. Andrews, Glasgow and ...

* Oflag II-C

Oflag II-C Woldenburg was a German World War II prisoner-of-war camp located about from the town of Woldenberg, Brandenburg (now Dobiegniew, western Poland). The camp housed Polish officers and orderlies and had an area of with 25 brick huts fo ...

* List of Polish people

This is a partial list of notable Polish or Polish-speaking or -writing people. People of partial Polish heritage have their respective ancestries credited.

Science

Physics

* Czesław Białobrzeski

* Andrzej Buras

* Georges Charpa ...

References

External links

*Horno-Popławski on the Polish site culture.pl

*

Bydgoszcz Art Centre

Bibliography

* * Horno. Stanisław Horno-Popławski. Rzeźba. Katalog wystawy. — Warszawa: Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych «Zachęta», 1970. * * Ewa Toniak, Olbrzymki. Kobiety i socrealizm, wyd. Korporacja Ha!art, Kraków 2008 * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Horno-Poplawski, Stanislaw 1902 births 1997 deaths 20th-century male artists People from Sopot Polish educational theorists Polish sculptors Polish male sculptors Academic staff of Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń People from Kutaisi Academic staff of the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk Artists from Białystok Recipients of the Gold Cross of Merit (Poland) Recipients of the State Award Badge (Poland) Prisoners of Oflag II-C Vilnius University alumni