The

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

(206 BCE – 220 CE) of

early imperial China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the ''Book of Documents'' (early chapter ...

, divided between the eras of Western Han (206 BCE – 9 CE, when the capital was at

Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin Shi ...

), the

Xin dynasty

The Xin dynasty (; ), also known as Xin Mang () in Chinese historiography, was a short-lived Chinese imperial dynasty which lasted from 9 to 23 AD, established by the Han dynasty consort kin Wang Mang, who usurped the throne of the Emperor Ping o ...

of

Wang Mang

Wang Mang () (c. 45 – 6 October 23 CE), courtesy name Jujun (), was the founder and the only Emperor of China, emperor of the short-lived Chinese Xin dynasty. He was originally an official and consort kin of the Han dynasty and later ...

(r. 9–23 CE), and Eastern Han (25–220 CE,

when the capital was at

Luoyang

Luoyang is a city located in the confluence area of Luo River (Henan), Luo River and Yellow River in the west of Henan province. Governed as a prefecture-level city, it borders the provincial capital of Zhengzhou to the east, Pingdingshan to the ...

, and after 196 CE at

Xuchang

Xuchang (; postal: Hsuchang) is a prefecture-level city in central Henan province of China, province in Central China. It borders the provincial capital of Zhengzhou to the northwest, Kaifeng to the northeast, Zhoukou to the east, Luohe to the s ...

), witnessed some of the most significant advancements in premodern

Chinese science and technology.

There were great innovations in

metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

. In addition to

Zhou-era China's (c. 1046 – 256 BCE) previous inventions of the

blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

and

cupola furnace

A cupola or cupola furnace is a melting device used in foundries that can be used to melt cast iron, Ni-resist iron and some bronzes. The cupola can be made almost any practical size. The size of a cupola is expressed in diameters and can range f ...

to make

pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silic ...

and

cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

, respectively, the Han period saw the development of

steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

and

wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

by use of the

finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and removing carbon from the molten cast iron through oxidation. Finery ...

and

puddling process. With the drilling of deep

borehole

A borehole is a narrow shaft bored in the ground, either vertically or horizontally. A borehole may be constructed for many different purposes, including the extraction of water ( drilled water well and tube well), other liquids (such as petro ...

s into the earth, the Chinese used not only

derrick

A derrick is a lifting device composed at minimum of one guyed mast, as in a gin pole, which may be articulated over a load by adjusting its guys. Most derricks have at least two components, either a guyed mast or self-supporting tower, and a ...

s to lift

brine

Brine is a high-concentration solution of salt (NaCl) in water (H2O). In diverse contexts, ''brine'' may refer to the salt solutions ranging from about 3.5% (a typical concentration of seawater, on the lower end of that of solutions used for br ...

up to the surface to be boiled into

salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quantitie ...

, but also set up bamboo-crafted

pipeline transport

Pipeline transport is the long-distance transportation of a liquid or gas through a system of pipes—a pipeline—typically to a market area for consumption. The latest data from 2014 gives a total of slightly less than of pipeline in 120 countr ...

systems which brought

natural gas

Natural gas (also called fossil gas or simply gas) is a naturally occurring mixture of gaseous hydrocarbons consisting primarily of methane in addition to various smaller amounts of other higher alkanes. Low levels of trace gases like carbo ...

as fuel to the furnaces. Smelting techniques were enhanced with inventions such as the

waterwheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or buckets ...

-powered

bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtigh ...

; the resulting widespread distribution of iron tools facilitated the growth of agriculture. For

tilling the soil and planting straight rows of crops, the improved heavy-moldboard plough with three iron

plowshare

In agriculture, a plowshare ( US) or ploughshare ( UK; ) is a component of a plow (or plough). It is the cutting or leading edge of a moldboard which closely follows the coulter (one or more ground-breaking spikes) when plowing.

The plowshar ...

s and sturdy multiple-tube iron

seed drill

A seed drill is a device used in agriculture that sows seeds for crops by positioning them in the soil and burying them to a specific depth while being dragged by a tractor. This ensures that seeds will be distributed evenly.

The seed drill sow ...

were invented in the Han, which greatly enhanced production yields and thus sustained population growth. The method of supplying

irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

ditches with water was improved with the invention of the mechanical

chain pump

The chain pump is type of a water pump in which several circular discs are positioned on an endless chain. One part of the chain dips into the water, and the chain runs through a tube, slightly bigger than the diameter of the discs. As the chain is ...

powered by the rotation of a waterwheel or draft animals, which could transport irrigation water up elevated terrains. The waterwheel was also used for operating

trip hammer

A trip hammer, also known as a tilt hammer or helve hammer, is a massive powered hammer. Traditional uses of trip hammers include pounding, decorticating and polishing of grain in agriculture. In mining, trip hammers were used for crushing meta ...

s in pounding grain and in rotating the metal rings of the mechanical-driven astronomical

armillary sphere

An armillary sphere (variations are known as spherical astrolabe, armilla, or armil) is a model of objects in the sky (on the celestial sphere), consisting of a spherical framework of rings, centered on Earth or the Sun, that represent lines of ...

representing the

celestial sphere

In astronomy and navigation, the celestial sphere is an abstract sphere that has an arbitrarily large radius and is concentric to Earth. All objects in the sky can be conceived as being projected upon the inner surface of the celestial sphere, ...

around the Earth.

The quality of life was improved with many Han inventions. The Han Chinese had hempen-bound bamboo scrolls to write on, yet by the 2nd century CE had invented the

papermaking

Papermaking is the manufacture of paper and cardboard, which are used widely for printing, writing, and packaging, among many other purposes. Today almost all paper is made using industrial machinery, while handmade paper survives as a speciali ...

process which created a writing medium that was both cheap and easy to produce. The invention of the

wheelbarrow

A wheelbarrow is a small hand-propelled vehicle, usually with just one wheel, designed to be pushed and guided by a single person using two handles at the rear, or by a sail to push the ancient wheelbarrow by wind. The term "wheelbarrow" is mad ...

aided in the hauling of heavy loads. The maritime

''junk'' ship and stern-mounted steering

rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally aircraft, air or watercraft, water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to ...

enabled the Chinese to venture out of calmer waters of interior lakes and rivers and into the open sea. The invention of the

grid reference

A projected coordinate system, also known as a projected coordinate reference system, a planar coordinate system, or grid reference system, is a type of spatial reference system that represents locations on the Earth using cartesian coordin ...

for maps and

raised-relief map

A raised-relief map, terrain model or embossed map is a three-dimensional representation, usually of terrain, materialized as a physical artifact. When representing terrain, the vertical dimension is usually exaggerated by a factor between fiv ...

allowed for better navigation of their terrain.

In medicine, they used new

herbal remedies

Herbal medicine (also herbalism) is the study of pharmacognosy and the use of medicinal plants, which are a basis of traditional medicine. With worldwide research into pharmacology, some herbal medicines have been translated into modern remedie ...

to cure illnesses,

calisthenics

Calisthenics (American English) or callisthenics (British English) ( /ˌkælɪsˈθɛnɪks/) is a form of strength training consisting of a variety of movements that exercise large muscle groups (gross motor movements), such as standing, graspi ...

to keep physically fit, and regulated

diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

s to avoid diseases. Authorities in the capital were warned ahead of time of the direction of sudden

earthquakes

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

with the invention of the

seismometer

A seismometer is an instrument that responds to ground noises and shaking such as caused by earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and explosions. They are usually combined with a timing device and a recording device to form a seismograph. The outpu ...

that was tripped by a vibration-sensitive

pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward the ...

device. To mark the passing of the seasons and special occasions, the Han Chinese

used two variations of the

lunisolar calendar

A lunisolar calendar is a calendar in many cultures, combining lunar calendars and solar calendars. The date of Lunisolar calendars therefore indicates both the Moon phase and the time of the solar year, that is the position of the Sun in the Ea ...

, which were established due to efforts in

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

and

mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

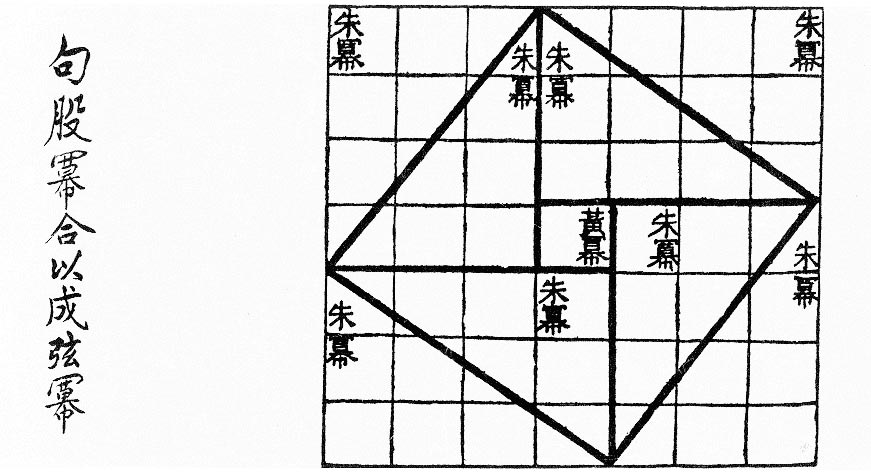

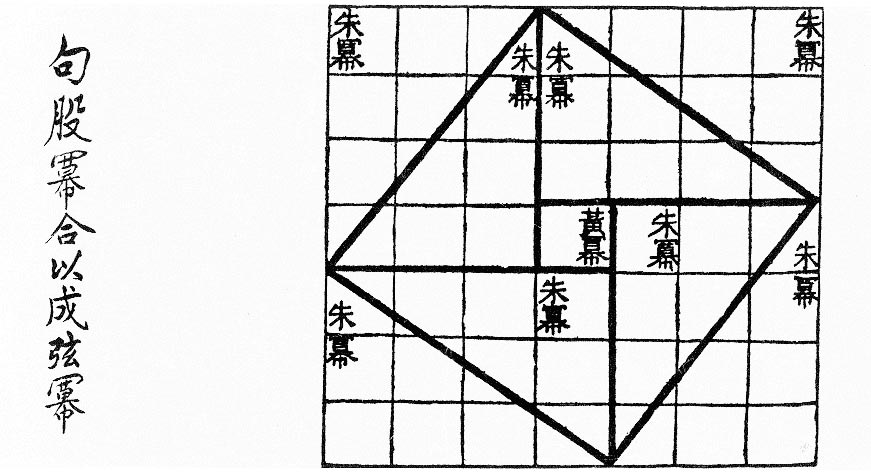

. Han-era Chinese advancements in mathematics include the discovery of

square root

In mathematics, a square root of a number is a number such that ; in other words, a number whose ''square'' (the result of multiplying the number by itself, or ⋅ ) is . For example, 4 and −4 are square roots of 16, because .

E ...

s,

cube root

In mathematics, a cube root of a number is a number such that . All nonzero real numbers, have exactly one real cube root and a pair of complex conjugate cube roots, and all nonzero complex numbers have three distinct complex cube roots. Fo ...

s, the

Pythagorean theorem

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras' theorem is a fundamental relation in Euclidean geometry between the three sides of a right triangle. It states that the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse (the side opposite t ...

,

Gaussian elimination

In mathematics, Gaussian elimination, also known as row reduction, is an algorithm for solving systems of linear equations. It consists of a sequence of operations performed on the corresponding matrix of coefficients. This method can also be used ...

, the

Horner scheme

In mathematics and computer science, Horner's method (or Horner's scheme) is an algorithm for polynomial evaluation. Although named after William George Horner, this method is much older, as it has been attributed to Joseph-Louis Lagrange by Hor ...

, improved calculations of ''

pi'', and

negative number

In mathematics, a negative number represents an opposite. In the real number system, a negative number is a number that is less than zero. Negative numbers are often used to represent the magnitude of a loss or deficiency. A debt that is owed m ...

s. Hundreds of new roads and canals were built to facilitate transport, commerce, tax collection, communication, and movement of military troops. The Han-era Chinese also employed several types of bridges to cross waterways and deep gorges, such as

beam bridge

Beam bridges are the simplest structural forms for bridge spans supported by an abutment or pier at each end. No moments are transferred throughout the support, hence their structural type is known as '' simply supported''.

The simplest beam ...

s,

arch bridge

An arch bridge is a bridge with abutments at each end shaped as a curved arch. Arch bridges work by transferring the weight of the bridge and its loads partially into a horizontal thrust restrained by the abutments at either side. A viaduct ...

s,

simple suspension bridge

A simple suspension bridge (also rope bridge, swing bridge (in New Zealand), suspended bridge, hanging bridge and catenary bridge) is a primitive type of bridge in which the deck of the bridge lies on two parallel load-bearing cables that ar ...

s, and

pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, uses float (nautical), floats or shallow-draft (hull), draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the supports limits the maxi ...

s. Han ruins of

defensive city walls made of

brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

or

rammed earth

Rammed earth is a technique for constructing foundations, floors, and walls using compacted natural raw materials such as earth, chalk, lime, or gravel. It is an ancient method that has been revived recently as a sustainable building method.

...

still stand today.

Modern perspectives

Jin Guantao, a professor of the Institute of Chinese Studies at the

Chinese University of Hong Kong

The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) is a public research university in Ma Liu Shui, Hong Kong, formally established in 1963 by a charter granted by the Legislative Council of Hong Kong. It is the territory's second-oldest university an ...

, Fan Hongye, a research fellow with the

Chinese Academy of Sciences

The Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS); ), known by Academia Sinica in English until the 1980s, is the national academy of the People's Republic of China for natural sciences. It has historical origins in the Academia Sinica during the Republ ...

' Institute of Science Policy and Managerial Science, and Liu Qingfeng, a professor of the Institute of Chinese Culture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, assert that the latter part of the Han dynasty was a unique period in the history of premodern Chinese science and technology.

[Jin, Fan, & Liu (1996), 178–179.] They compare it to the incredible pace of

scientific and technological growth during the

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

(960–1279). However, they also argue that without the influence of proto-scientific precepts in the ancient philosophy of

Mohism

Mohism or Moism (, ) was an ancient Chinese philosophy of ethics and logic, rational thought, and science developed by the academic scholars who studied under the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 BC – c. 391 BC), embodied in an epony ...

, Chinese science continued to lack a definitive structure:

From the middle and late Eastern Han to the early Wei and Jin dynasties, the net growth of ancient Chinese science and technology experienced a peak (second only to that of the Northern Song dynasty) ...Han studies of the Confucian classics, which for a long time had hindered the socialization of science, were declining. If Mohism, rich in scientific thought, had rapidly grown and strengthened, the situation might have been very favorable to the development of a scientific structure. However, this did not happen because the seeds of the primitive structure of science were never formed. During the late Eastern Han, disastrous upheavals again occurred in the process of social transformation, leading to the greatest social disorder in Chinese history. One can imagine the effect of this calamity on science.

Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, in ...

(1900–1995), a late Professor from the

University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

and author of the groundbreaking ''

Science and Civilisation in China

''Science and Civilisation in China'' (1954–present) is an ongoing series of books about the history of science and technology in China published by Cambridge University Press. It was initiated and edited by British historian Joseph Needham (1 ...

'' series, stated that the "Han time (especially the Later Han) was one of the relatively important periods as regards the history of science in China."

[Needham (1972), 111.] He noted the advancements during Han of

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

and

calendrical sciences, the "beginnings of systematic

botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

and

zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

", as well as the

philosophical skepticism

Philosophical skepticism ( UK spelling: scepticism; from Greek σκέψις ''skepsis'', "inquiry") is a family of philosophical views that question the possibility of knowledge. It differs from other forms of skepticism in that it even reject ...

and

rationalist thought embodied in Han works such as the ''

Lunheng

The ''Lunheng'', also known by numerous English translations, is a wide-ranging Chinese classic text by Wang Chong (27- ). First published in 80, it contains critical essays on natural science and Chinese mythology, philosophy, and literature ...

'' by the philosopher

Wang Chong

Wang Chong (; 27 – c. 97 AD), courtesy name Zhongren (仲任), was a Chinese astronomer, meteorologist, naturalist, philosopher, and writer active during the Han Dynasty. He developed a rational, secular, naturalistic and mechanistic account ...

(27–100 CE).

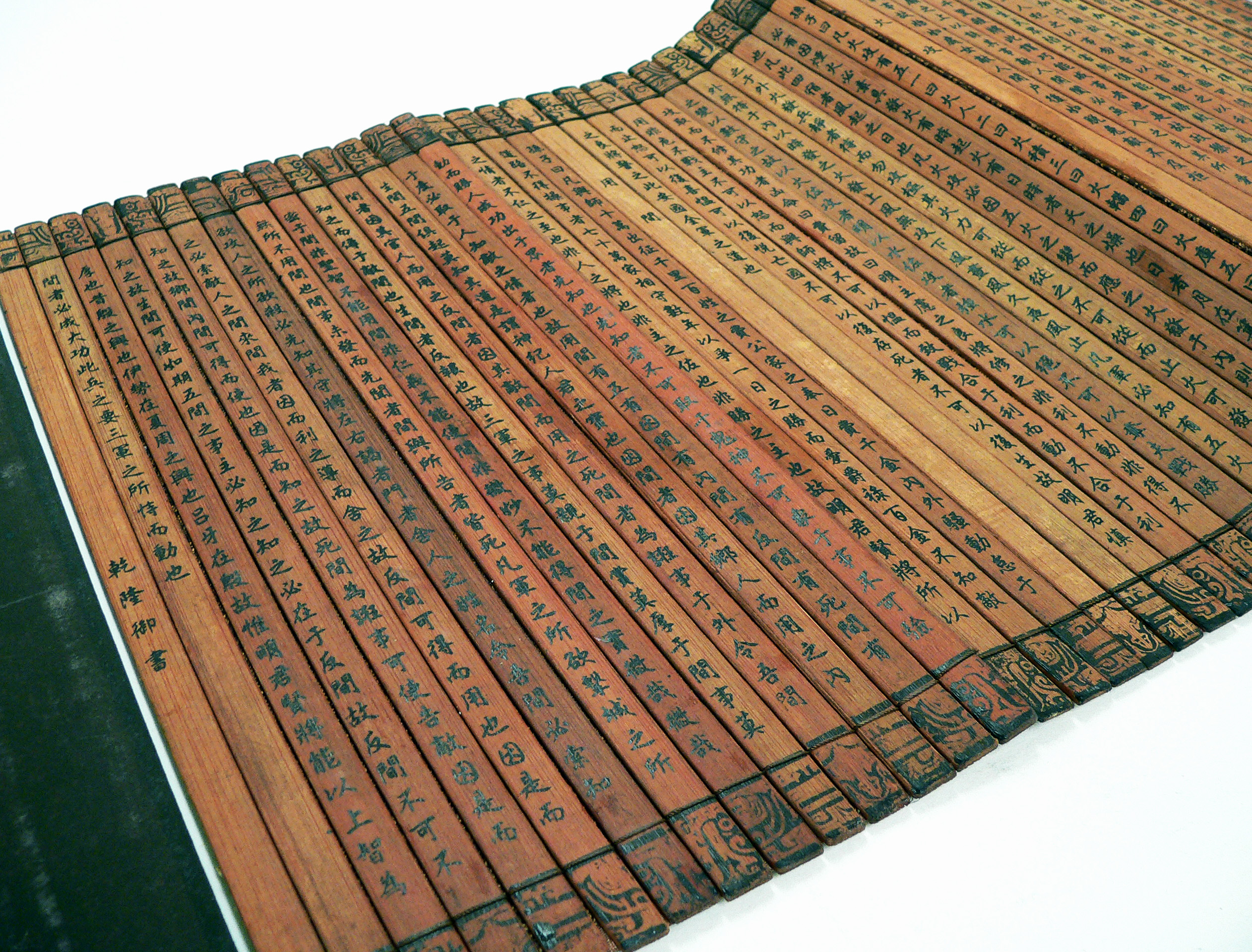

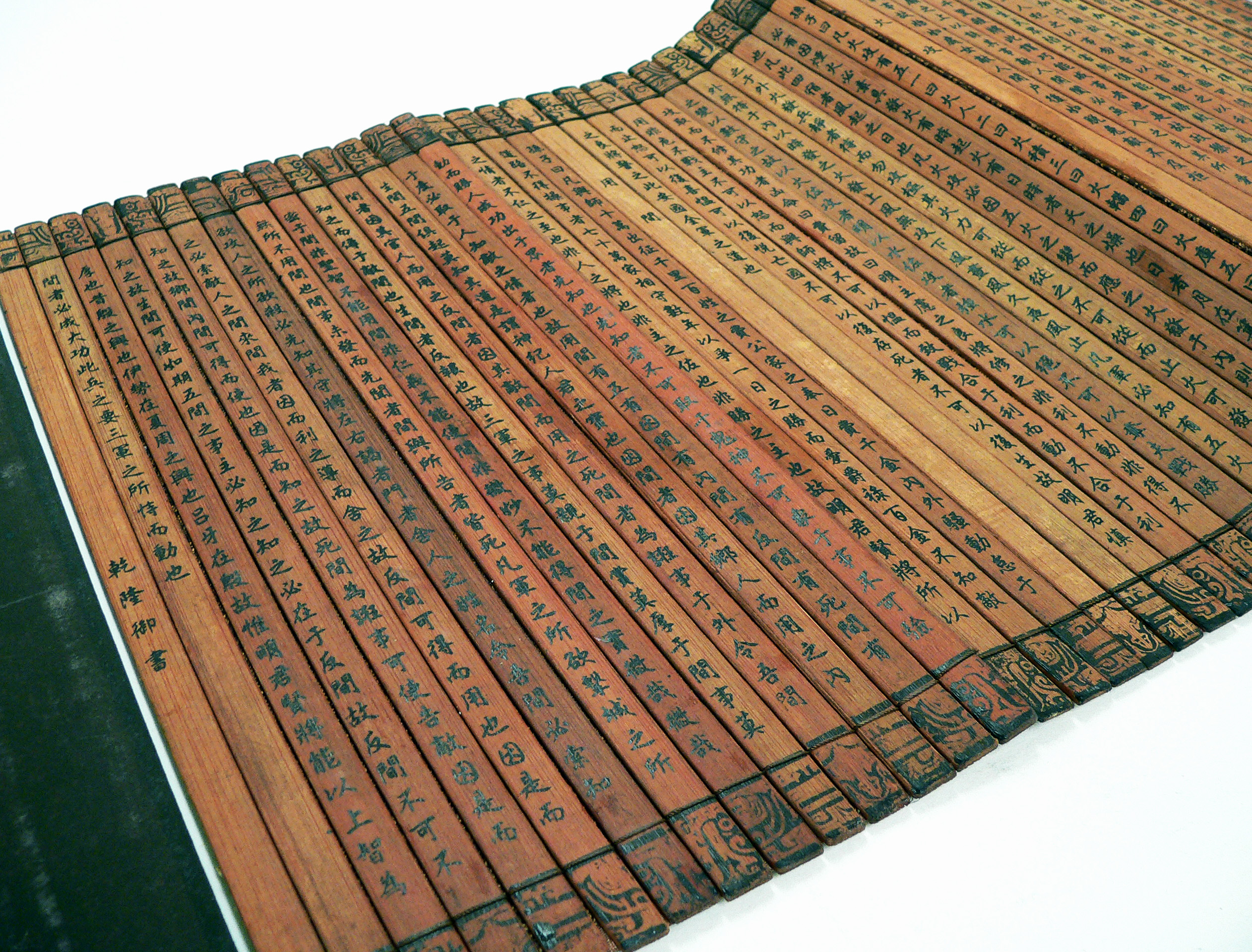

Writing materials

The most common writing mediums found in archaeological digs from ancient sites predating the Han period are

shells and bones as well as

bronzewares.

[Loewe (1968), 89.] In the beginning of the Han period, the chief writing mediums were bamboo () and

clay tablet

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian ) were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a stylu ...

s,

silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

cloth, strips of soft wood, and rolled scrolls made of strips of

bamboo

Bamboos are a diverse group of evergreen perennial flowering plants making up the subfamily Bambusoideae of the grass family Poaceae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. The origin of the word "bamboo" is uncertain, bu ...

sewn together with

hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of ''Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants o ...

en string passed through drilled holes (册) and secured with

clay stamps. The

written characters on these narrow flat strips of bamboo were arranged into vertical columns.

While

maps drawn in ink on flat silk cloths

have been found in the tomb of the Marquess of Dai (interred in 168 BCE at

Mawangdui

Mawangdui () is an archaeological site located in Changsha, China. The site consists of two saddle-shaped hills and contained the tombs of three people from the Changsha Kingdom during the western Han dynasty (206 BC – 9 AD): the Chancellor Li ...

,

Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi to ...

province), the earliest known

paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, rags, grasses or other vegetable sources in water, draining the water through fine mesh leaving the fibre evenly distributed ...

map found in China, dated 179–141 BCE and located at

Fangmatan

Fangmatan () is an archeological site located near Tianshui in China's Gansu province. The site was located within the Qin state, and includes several burials dating from the Warring States period through to the early Western Han.

Tomb 1

The date ...

(near

Tianshui

Tianshui is the second-largest cities in Gansu, city in Gansu list of Chinese provinces, Province, China. The city is located in the southeast of the province, along the upper reaches of the Wei River and at the boundary of the Loess Plateau and ...

,

Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibet ...

province), is incidentally the oldest known piece of paper.

[Buisseret (1998), 12.] Yet Chinese hempen paper of the Western Han and early Eastern Han eras was of a coarse quality and used primarily as

wrapping paper

Gift wrapping is the act of enclosing a gift in some sort of material. Wrapping paper is a kind of paper designed for gift wrapping. An alternative to gift wrapping is using a gift box or bag. A wrapped or boxed gift may be held closed with ribb ...

.

[Needham (1986e), 1–2, 40–41, 122–123, 228.] The

papermaking

Papermaking is the manufacture of paper and cardboard, which are used widely for printing, writing, and packaging, among many other purposes. Today almost all paper is made using industrial machinery, while handmade paper survives as a speciali ...

process was not formally introduced until the Eastern Han court eunuch

Cai Lun

Cai Lun (; courtesy name: Jingzhong (); – 121 CE), formerly romanized as Ts'ai Lun, was a Chinese eunuch court official of the Eastern Han dynasty. He is traditionally regarded as the inventor of paper and the modern papermaking process ...

(50–121 CE) created a process in 105 where

mulberry tree

''Morus'', a genus of flowering plants in the family Moraceae, consists of diverse species of deciduous trees commonly known as mulberries, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions. Generally, the genus has 64 identif ...

bark, hemp, old linens, and fish nets were boiled together to make a pulp that was pounded, stirred in water, and then dunked with a wooden sieve containing a

reed

Reed or Reeds may refer to:

Science, technology, biology, and medicine

* Reed bird (disambiguation)

* Reed pen, writing implement in use since ancient times

* Reed (plant), one of several tall, grass-like wetland plants of the order Poales

* ...

mat that was shaken, dried, and bleached into sheets of paper. The oldest known piece of paper with writing on it comes from the ruins of a Chinese

watchtower

A watchtower or watch tower is a type of fortification used in many parts of the world. It differs from a regular tower in that its primary use is military and from a turret in that it is usually a freestanding structure. Its main purpose is to ...

at Tsakhortei,

Alxa League

Alxa League or Ālāshàn League (; mn, , Mongolian Cyrillic. Алшаа аймаг) is one of 12 prefecture level divisions and 3 extant leagues of Inner Mongolia. The league borders Mongolia to the north, Bayan Nur to the northeast, Wuhai ...

,

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

, dated precisely to 110 CE when the Han garrison abandoned the area following a nomadic

Xiongnu

The Xiongnu (, ) were a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 20 ...

attack.

[Cotterell (2004), 11.] By the 3rd century, paper became one of China's chief writing mediums.

[Needham (1986e), 1–2.]

Ceramics

The Han

ceramics

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain ...

industry was upheld by private businesses as well as local government agencies.

[Wang (1982), 146–147.] Ceramics were used in domestic wares and utensils as well as construction materials for roof

tile

Tiles are usually thin, square or rectangular coverings manufactured from hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, baked clay, or even glass. They are generally fixed in place in an array to cover roofs, floors, walls, edges, or o ...

s and

brick

A brick is a type of block used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a block composed of dried clay, but is now also used informally to denote other chemically cured cons ...

s.

[Wang (1982), 147–149.]

Han dynasty grey

pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and por ...

—its color derived from the

clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

that was used—was superior to earlier Chinese grey pottery due to the Han people's use of larger

kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay int ...

chambers, longer firing tunnels, and improved chimney designs.

[Wang (1982), 142–143.] Kilns of the Han dynasty making grey pottery were able to reach firing temperatures above .

However, hard southern Chinese pottery made from a dense adhesive clay native only in the south (i.e.

Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020) ...

,

Guangxi

Guangxi (; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternately romanized as Kwanghsi; ; za, Gvangjsih, italics=yes), officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the People's Republic ...

,

Hunan

Hunan (, ; ) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, part of the South Central China region. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi to ...

,

Jiangxi

Jiangxi (; ; formerly romanized as Kiangsi or Chianghsi) is a landlocked province in the east of the People's Republic of China. Its major cities include Nanchang and Jiujiang. Spanning from the banks of the Yangtze river in the north int ...

,

Fujian

Fujian (; alternately romanized as Fukien or Hokkien) is a province on the southeastern coast of China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its capi ...

,

Zhejiang

Zhejiang ( or , ; , also romanized as Chekiang) is an eastern, coastal province of the People's Republic of China. Its capital and largest city is Hangzhou, and other notable cities include Ningbo and Wenzhou. Zhejiang is bordered by Jiang ...

, and southern

Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, Postal romanization, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an Eastern China, eastern coastal Provinces of the People's Republic of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China. It is o ...

) was fired at even higher temperatures than grey pottery during the Han.

of the

Shang

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and f ...

(c. 1600 – c. 1050 BCE) and

Zhou (c. 1050 – 256 BCE) dynasties were fired at high temperatures, but by the mid Western Han (206 BCE – 9 CE), a brown-glazed ceramic was made which was fired at the low temperature of , followed by a green-glazed ceramic which became popular in the Eastern Han (25–220 CE).

[Wang (1982), 143–145.]

Wang Zhongshu

Wang Zhongshu (; 15 October 1925 – 24 September 2015) was a Chinese archaeologist who helped to establish and develop the field of archaeology in China. One of the most prominent Asian archaeologists, he was awarded the Grand Prize of the Fuk ...

states that the light-green

stoneware

Stoneware is a rather broad term for pottery or other ceramics fired at a relatively high temperature. A modern technical definition is a Vitrification#Ceramics, vitreous or semi-vitreous ceramic made primarily from stoneware clay or non-refracto ...

known as

celadon

''Celadon'' () is a term for pottery denoting both wares glazed in the jade green celadon color, also known as greenware or "green ware" (the term specialists now tend to use), and a type of transparent glaze, often with small cracks, that was ...

was thought to exist only since the

Three Kingdoms

The Three Kingdoms () from 220 to 280 AD was the tripartite division of China among the dynastic states of Cao Wei, Shu Han, and Eastern Wu. The Three Kingdoms period was preceded by the Han dynasty#Eastern Han, Eastern Han dynasty and wa ...

period (220–265 CE) onwards, but argues that ceramic shards found at Eastern Han (25–220 CE) sites of Zhejiang province can be classified as

celadon

''Celadon'' () is a term for pottery denoting both wares glazed in the jade green celadon color, also known as greenware or "green ware" (the term specialists now tend to use), and a type of transparent glaze, often with small cracks, that was ...

.

[Wang (1982), 145.] However, Richard Dewar argues that true celadon was not created in China until the early

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

(960–1279) when Chinese kilns were able to reach a minimum furnace temperature of , with a preferred range of for celadon.

[Dewar (2002), 42.]

Metallurgy

Furnaces and smelting techniques

A

blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

converts raw

iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of whic ...

into

iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in f ...

, which can be remelted in a

cupola furnace

A cupola or cupola furnace is a melting device used in foundries that can be used to melt cast iron, Ni-resist iron and some bronzes. The cupola can be made almost any practical size. The size of a cupola is expressed in diameters and can range f ...

to produce

cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

. The earliest specimens of cast iron found in China date to the 5th century BCE during the late

Spring and Autumn period

The Spring and Autumn period was a period in Chinese history from approximately 770 to 476 BC (or according to some authorities until 403 BC) which corresponds roughly to the first half of the Eastern Zhou period. The period's name derives fr ...

, yet the oldest discovered blast furnaces date to the 3rd century BCE and the majority date to the period after

Emperor Wu of Han

Emperor Wu of Han (156 – 29 March 87BC), formally enshrined as Emperor Wu the Filial (), born Liu Che (劉徹) and courtesy name Tong (通), was the seventh emperor of the Han dynasty of ancient China, ruling from 141 to 87 BC. His reign la ...

(r. 141–87 BCE)

established a government monopoly over the iron industry in 117 BCE (most of the discovered iron works sites built before this date were merely

foundries

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

which recast iron that had been smelted elsewhere). Iron ore smelted in blast furnaces during the Han was rarely if ever cast directly into permanent molds; instead, the pig iron scraps were remelted in the cupola furnace to make cast iron.

[Wagner (2001), 75–76.] Cupola furnaces utilized a

cold blast

Cold blast, in ironmaking, refers to a metallurgical furnace where air is not preheated before being blown into the furnace. This represents the earliest stage in the development of ironmaking. Until the 1820s, the use of cold air was thought to b ...

traveling through

tuyere

A tuyere or tuyère (; ) is a tube, nozzle or pipe through which air is blown into a furnace or hearth.W. K. V. Gale, The iron and Steel industry: a dictionary of terms (David and Charles, Newton Abbot 1972), 216–217.

Air or oxygen is injec ...

pipes from the bottom and over the top where the charge of

charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

and pig iron was introduced.

The air traveling through the tuyere pipes thus became a

hot blast

Hot blast refers to the preheating of air blown into a blast furnace or other metallurgical process. As this considerably reduced the fuel consumed, hot blast was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution. ...

once it reached the bottom of the furnace.

Although Chinese civilization lacked the

bloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a ''bloom ...

, the Han Chinese were able to make

wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

when they injected too much

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

into the cupola furnace, causing

decarburization

Decarburization (or decarbonization) is the process of decreasing carbon content, which is the opposite of carburization.

The term is typically used in metallurgy, describing the decrease of the content of carbon in metals (usually steel). Deca ...

. The Han-era Chinese were also able to convert cast iron and pig iron into wrought iron and

steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

by using the

finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and removing carbon from the molten cast iron through oxidation. Finery ...

and

puddling process, the earliest specimens of such dating to the 2nd century BCE and found at Tieshengguo near

Mount Song

Mount Song (, "lofty mountain") is an isolated mountain range in north central China's Henan Province, along the southern bank of the Yellow River. It is known in literary and folk tradition as the central mountain of the Five Great Mountains of ...

of

Henan

Henan (; or ; ; alternatively Honan) is a landlocked province of China, in the central part of the country. Henan is often referred to as Zhongyuan or Zhongzhou (), which literally means "central plain" or "midland", although the name is al ...

province. The semisubterranean walls of these furnaces were lined with

refractory

In materials science, a refractory material or refractory is a material that is resistant to decomposition by heat, pressure, or chemical attack, and retains strength and form at high temperatures. Refractories are polycrystalline, polyphase, ...

bricks and had bottoms made of refractory clay. Besides charcoal made of wood,

Wang Zhongshu

Wang Zhongshu (; 15 October 1925 – 24 September 2015) was a Chinese archaeologist who helped to establish and develop the field of archaeology in China. One of the most prominent Asian archaeologists, he was awarded the Grand Prize of the Fuk ...

states that another furnace fuel used during the Han were "coal cakes", a mixture of

coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

powder, clay, and

quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical form ...

.

[Wang (1982), 126.]

Use of steel, iron, and bronze

Donald B. Wagner writes that most domestic iron tools and implements produced during the Han were made of cheaper and more brittle cast iron, whereas

the military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

preferred to use wrought iron and steel weaponry due to their more durable qualities. During the Han dynasty, the typical

bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

sword found in the

Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in History of China#Ancient China, ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded ...

was gradually replaced with

an iron sword measuring roughly in length. The ancient

dagger-axe

The dagger-axe () is a type of pole weapon that was in use from the Erlitou culture until the Han dynasty in China. It consists of a dagger-shaped blade, mounted by its tang to a perpendicular wooden shaft. The earliest dagger-axe blades were ...

(''ge'') made of bronze was still used by Han soldiers, although it was gradually phased out by iron spears and iron

''ji'' halberds.

[Wang (1982), 123.] Even

arrowhead

An arrowhead or point is the usually sharpened and hardened tip of an arrow, which contributes a majority of the projectile mass and is responsible for impacting and penetrating a target, as well as to fulfill some special purposes such as sign ...

s, which were traditionally made of bronze, gradually only had a bronze tip and iron shaft, until the end of the Han when the entire arrowhead was made solely of iron.

Farmers,

carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, Shipbuilding, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. ...

s, bamboo craftsmen,

stonemason

Stonemasonry or stonecraft is the creation of buildings, structures, and sculpture using stone as the primary material. It is one of the oldest activities and professions in human history. Many of the long-lasting, ancient shelters, temples, mo ...

s, and

rammed earth

Rammed earth is a technique for constructing foundations, floors, and walls using compacted natural raw materials such as earth, chalk, lime, or gravel. It is an ancient method that has been revived recently as a sustainable building method.

...

builders had at their disposal iron tools such as the

plowshare

In agriculture, a plowshare ( US) or ploughshare ( UK; ) is a component of a plow (or plough). It is the cutting or leading edge of a moldboard which closely follows the coulter (one or more ground-breaking spikes) when plowing.

The plowshar ...

,

pickaxe

A pickaxe, pick-axe, or pick is a generally T-shaped hand tool used for Leverage (mechanics), prying. Its head is typically metal, attached perpendicularly to a longer handle, traditionally made of wood, occasionally metal, and increasingly ...

,

spade

A spade is a tool primarily for digging consisting of a long handle and blade, typically with the blade narrower and flatter than the common shovel. Early spades were made of riven wood or of animal bones (often shoulder blades). After the a ...

,

shovel

A shovel is a tool used for digging, lifting, and moving bulk materials, such as soil, coal, gravel, snow, sand, or ore.

Most shovels are hand tools consisting of a broad blade fixed to a medium-length handle. Shovel blades are usually made of ...

,

hoe,

sickle

A sickle, bagging hook, reaping-hook or grasshook is a single-handed agricultural tool designed with variously curved blades and typically used for harvesting, or reaping, grain crops or cutting succulent forage chiefly for feeding livestock, ei ...

,

axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

,

adze

An adze (; alternative spelling: adz) is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing ...

,

hammer

A hammer is a tool, most often a hand tool, consisting of a weighted "head" fixed to a long handle that is swung to deliver an impact to a small area of an object. This can be, for example, to drive nails into wood, to shape metal (as w ...

,

chisel

A chisel is a tool with a characteristically shaped cutting edge (such that wood chisels have lent part of their name to a particular grind) of blade on its end, for carving or cutting a hard material such as wood, stone, or metal by hand, stru ...

,

knife

A knife ( : knives; from Old Norse 'knife, dirk') is a tool or weapon with a cutting edge or blade, usually attached to a handle or hilt. One of the earliest tools used by humanity, knives appeared at least 2.5 million years ago, as evidenced ...

,

saw

A saw is a tool consisting of a tough blade, wire, or chain with a hard toothed edge. It is used to cut through material, very often wood, though sometimes metal or stone. The cut is made by placing the toothed edge against the material and mo ...

,

scratch awl

A scratch awl is a woodworking layout and point-making tool. It is used to scribe a line to be followed by a hand saw or chisel when making woodworking joints and other operations.

The scratch awl is basically a steel spike with its tip sharpen ...

, and

nails.

[Wang (1982), 122.] Common iron commodities found in Han dynasty homes included tripods,

stove

A stove or range is a device that burns fuel or uses electricity to generate heat inside or on top of the apparatus, to be used for general warming or cooking. It has evolved highly over time, with cast-iron and induction versions being develope ...

s,

cooking pots,

belt buckle

A belt buckle is a buckle, a clasp for fastening two ends, such as of straps or a belt, in which a device attached to one of the ends is fitted or coupled to the other. The word enters Middle English via Old French and the Latin ''buccula' ...

s,

tweezers

Tweezers are small hand tools used for grasping objects too small to be easily handled with the human fingers. Tweezers are thumb-driven forceps most likely derived from tongs used to grab or hold hot objects since the dawn of recorded history. ...

, fire

tongs

Tongs are a type of tool used to grip and lift objects instead of holding them directly with hands. There are many forms of tongs adapted to their specific use.

The first pair of tongs belongs to the Egyptians. Tongs likely started off as b ...

,

scissors

Scissors are hand-operated shearing tools. A pair of scissors consists of a pair of metal blades pivoted so that the sharpened edges slide against each other when the handles (bows) opposite to the pivot are closed. Scissors are used for cutti ...

, kitchen knives,

fish hook

A fish hook or fishhook, formerly also called angle (from Old English ''angol'' and Proto-Germanic ''*angulaz''), is a hook used to catch fish either by piercing and embedding onto the inside of the fish mouth (angling) or, more rarely, by impa ...

s, and

needles.

Mirrors

A mirror or looking glass is an object that Reflection (physics), reflects an image. Light that bounces off a mirror will show an image of whatever is in front of it, when focused through the lens of the eye or a camera. Mirrors reverse the ...

and

oil lamp

An oil lamp is a lamp used to produce light continuously for a period of time using an oil-based fuel source. The use of oil lamps began thousands of years ago and continues to this day, although their use is less common in modern times. Th ...

s were often made of either bronze or iron.

Coin money minted

during the Han was made of either

copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

or copper and

tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

smelted together to make the bronze alloy.

Agriculture

Tools and methods

Modern archaeologists have unearthed Han iron farming tools throughout China, from

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

in the north to

Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in Southwest China, the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is ...

in the south.

[Wang (1982), 53.] The spade, shovel, pick, and

plow

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

were used for

tillage

Tillage is the agricultural preparation of soil by mechanical agitation of various types, such as digging, stirring, and overturning. Examples of human-powered tilling methods using hand tools include shoveling, picking, mattock work, hoein ...

, the hoe for

weed

A weed is a plant considered undesirable in a particular situation, "a plant in the wrong place", or a plant growing where it is not wanted.Harlan, J. R., & deWet, J. M. (1965). Some thoughts about weeds. ''Economic botany'', ''19''(1), 16-24. ...

ing, the

rake for loosening the soil, and the

sickle

A sickle, bagging hook, reaping-hook or grasshook is a single-handed agricultural tool designed with variously curved blades and typically used for harvesting, or reaping, grain crops or cutting succulent forage chiefly for feeding livestock, ei ...

for harvesting crops.

Depending on their size, Han plows were driven by either one ox or two oxen.

[Wang (1982), 54.] Oxen were also used to pull the three-legged iron

seed drill

A seed drill is a device used in agriculture that sows seeds for crops by positioning them in the soil and burying them to a specific depth while being dragged by a tractor. This ensures that seeds will be distributed evenly.

The seed drill sow ...

(invented in Han China by the 2nd century BCE), which enabled farmers to plant seeds in precise rows instead of

casting them out by hand. While artwork of the

Wei (220–266 CE) and

Jin (266–420) periods show use of the

harrow for breaking up chunks of soil after plowing, it perhaps first appeared in China during the Eastern Han (25–220 CE).

[Wang (1982), 55.] Irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

works for agriculture included the use of

water well

A well is an excavation or structure created in the ground by digging, driving, or drilling to access liquid resources, usually water. The oldest and most common kind of well is a water well, to access groundwater in underground aquifers. Th ...

s, artificial ponds and embankments,

dam

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use ...

s,

canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flow un ...

s, and

sluice

Sluice ( ) is a word for a channel controlled at its head by a movable gate which is called a sluice gate. A sluice gate is traditionally a wood or metal barrier sliding in grooves that are set in the sides of the waterway and can be considered ...

gates.

Alternating fields

During

Emperor Wu's (r. 141–87 BCE) reign, the Grain Intendant Zhao Guo (趙過) invented the alternating fields system (''daitianfa'' 代田法).

[Nishijima (1986), 561.] For every

''mou'' of land—i.e. a thin but elongated strip of land measuring wide and long, or an area of roughly

—three low-lying

furrows

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

(''quan'' 甽) that were each wide were sowed in straight lines with crop seed.

While weeding in the summer, the loose soil of the

ridges

A ridge or a mountain ridge is a geographical feature consisting of a chain of mountains or hills that form a continuous elevated crest for an extended distance. The sides of the ridge slope away from the narrow top on either side. The line ...

(''long'' 壟) on either side of the furrows would gradually fall into the furrows, covering the sprouting crops and protecting them from wind and drought.

Since the position of the furrows and ridges were reversed by the next year, this process was called the alternating fields system.

This system allowed crops to grow in straight lines from sowing to harvest, conserved moisture in the soil, and provided a stable annual yield for harvested crops.

[Nishijima (1986), 562.] Zhao Guo first experimented with this system right outside the capital

Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin Shi ...

, and once it proved successful, he sent out instructions for it to every

commandery

In the Middle Ages, a commandery (rarely commandry) was the smallest administrative division of the European landed properties of a military order. It was also the name of the house where the knights of the commandery lived.Anthony Luttrell and G ...

administrator, who were then responsible for disseminating these to the heads of every

county

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

,

district

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions o ...

, and

hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

in their commanderies.

Sadao Nishijima speculates that the Imperial Counselor

Sang Hongyang

Sang Hongyang (Chinese: ; c. 152–80 BC) was a Chinese politician. He was a prominent official of the Han Dynasty, who served Emperor Wu of Han and his successor Emperor Zhao. He is famous for his economic policies during the reign of Emperor ...

(d. 80 BCE) perhaps had a role in promoting this new system.

Rich families who owned oxen and large heavy moldboard iron plows greatly benefited from this new system.

However, poorer farmers who did not own oxen resorted to using teams of men to move a single plow, which was exhausting work.

[Nishijima (1986), 563–564.] The author Cui Shi (催寔) (d. 170 CE) wrote in his ''Simin yueling'' (四民月令) that by the Eastern Han Era (25–220 CE) an improved plow was invented which needed only one man to control it, two oxen to pull it, had three plowshares, a seed box for the drills, a tool which turned down the soil, and could sow roughly of land in a single day.

Pit fields

During the reign of

Emperor Cheng of Han

Emperor Cheng of Han (51 BC – 17 April 7 BC) was an emperor of the Chinese Han dynasty ruling from 33 until 7 BC. He succeeded his father Emperor Yuan of Han. Under Emperor Cheng, the Han dynasty continued its growing disintegration as the emp ...

(r. 33–37 BCE), Fan Shengzhi wrote a manual (i.e. the ''

Fan Shengzhi shu

''Fan Shengzhi shu'' ("Fan Shengzhi's book" or "Fan Shengzhi's manual") was a Chinese agricultural text from the Han dynasty, written by Fan Shengzhi in the first century BC. The book was lost in the 11th- or 12th-century Song dynasty, possibly dur ...

'') which described the pit field system (''aotian'' 凹田).

[Nishijima (1986), 564–565.][Hinsch (2002), 67–68.] In this system, every ''mou'' of farmland was divided into 3,840 grids which each had a small pit that was dug deep and wide and had good quality

manure

Manure is organic matter that is used as organic fertilizer in agriculture. Most manure consists of animal feces; other sources include compost and green manure. Manures contribute to the fertility of soil by adding organic matter and nutri ...

mixed into the soil.

Twenty seeds were sowed into each pit, which allegedly produced 0.6 L (20

oz) of harvested grain per pit, or roughly 2,000 L (67,630 oz) per ''mou''.

This system did not require oxen-driven plows or the most fertile land, since it could be employed even on sloping terrains where supplying water was difficult for other methods of farming. Although this farming method was favored by the poor, it did require intensive labor, thus only large families could maintain such a system.

Rice paddies

Han farmers in the

Yangzi River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

region of southern China often maintained

paddy field

A paddy field is a flooded field (agriculture), field of arable land used for growing Aquatic plant, semiaquatic crops, most notably rice and taro. It originates from the Neolithic rice-farming cultures of the Yangtze River basin in sout ...

s for growing

rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' (Asian rice) or less commonly ''Oryza glaberrima

''Oryza glaberrima'', commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species. It was first domesticated and grown i ...

. Every year, they would burn the weeds in the paddy field, drench it in water, sow rice by hand, and around harvest time cut the surviving weeds and drown them a second time.

[Nishijima (1986), 568–569.] In this system, the field lays

fallow

Fallow is a farming technique in which arable land is left without sowing for one or more vegetative cycles. The goal of fallowing is to allow the land to recover and store organic matter while retaining moisture and disrupting pest life cycles ...

for much of the year and thus did not remain very fertile.

However, Han rice farmers to the north around the

Huai River

The Huai River (), Postal Map Romanization, formerly romanization of Chinese, romanized as the Hwai, is a major river in China. It is located about midway between the Yellow River and Yangtze, the two longest rivers and largest drainage basins ...

practiced the more advanced system of

transplantation.

[Nishijima (1986), 570–572.] In this system, individual plants were given intensive care (perhaps in the same location as the paddy field), their offshoots separated so that more water could be conserved, and the field could be heavily fertilized since winter crops were grown while the rice seedlings were situated nearby in a plant nursery.

Mechanical and hydraulic engineering

Literary sources and archaeological evidence

Evidence of Han-era mechanical engineering comes largely from the choice observational writings of sometimes disinterested Confucian scholars. Professional artisan-engineers (''jiang'' 匠) did not leave behind detailed records of their work. Han scholars, who often had little or no expertise in mechanical engineering, sometimes provided insufficient information on the various technologies they described.

Nevertheless, some Han literary sources provide crucial information. As written by Yang Xiong in 15 BCE, the

belt drive

A belt is a loop of flexible material used to link two or more rotating shafts mechanically, most often parallel. Belts may be used as a source of motion, to transmit power efficiently or to track relative movement. Belts are looped over pulley ...

was first used for a

quilling

Quilling is an art form that involves the use of strips of paper that are rolled, shaped, and glued together to create decorative designs. The paper is rolled, looped, curled, twisted, and otherwise manipulated to create shapes that make up d ...

device which wound silk fibers onto the

bobbin

A bobbin or spool is a spindle or cylinder, with or without flanges, on which yarn, thread, wire, tape or film is wound. Bobbins are typically found in industrial textile machinery, as well as in sewing machines, fishing reels, tape measure ...

s of weaver shuttles.

[Temple (1986), 54–55.] The invention of the belt drive was a crucial first step in the development of

later technologies during the Song dynasty, such as the

chain drive

Chain drive is a way of transmitting mechanical power from one place to another. It is often used to convey power to the wheels of a vehicle, particularly bicycles and motorcycles. It is also used in a wide variety of machines besides vehicles. ...

and

spinning wheel

A spinning wheel is a device for spinning thread or yarn from fibres. It was fundamental to the cotton textile industry prior to the Industrial Revolution. It laid the foundations for later machinery such as the spinning jenny and spinning f ...

.

The inventions of the artisan and mechanical engineer Ding Huan (丁緩) are mentioned in the ''Miscellaneous Notes on the Western Capital''. The official and poet

Sima Xiangru

Sima Xiangru ( , ; c. 179117BC) was a Chinese musician, poet, and politician who lived during the Western Han dynasty. Sima is a significant figure in the history of Classical Chinese poetry, and is generally regarded as the greatest of all com ...

(179–117 BCE) once hinted in his writings that the Chinese used a

censer

A censer, incense burner, perfume burner or pastille burner is a vessel made for burning incense or perfume in some solid form. They vary greatly in size, form, and material of construction, and have been in use since ancient times throughout t ...

in the form of a

gimbal

A gimbal is a pivoted support that permits rotation of an object about an axis. A set of three gimbals, one mounted on the other with orthogonal pivot axes, may be used to allow an object mounted on the innermost gimbal to remain independent of ...

, a pivot support made of concentric rings which allow the central gimbal to

rotate on an axis while remaining vertically positioned.

[Needham (1986c), 233–234.] However, the first explicit mention of the gimbal used as an incense burner occurred around 180 CE when the artisan Ding Huan created his 'Perfume Burner for use among Cushions' which allowed burning incense placed within the central gimbal to remain constantly level even when moved. Ding had other inventions as well. For the purpose of indoor

air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C or AC, is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior environment (sometimes referred to as 'comfort cooling') and in some cases also strictly controlling ...

, he set up a large manually operated

rotary fan which had rotating wheels that were in diameter. He also invented a lamp which he called the 'nine-storied hill-censer', since it was shaped as a hillside.

[Temple (1986), 87; Needham (1986b), 123.] When the cylindrical lamp was lit, the

convection

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the convec ...

of rising hot air currents caused vanes placed on the top to spin, which in turn rotated painted paper figures of birds and other animals around the lamp.

When

Emperor Gaozu of Han

Emperor Gaozu of Han (256 – 1 June 195 BC), born Liu Bang () with courtesy name Ji (季), was the founder and first emperor of the Han dynasty, reigning in 202–195 BC. His temple name was "Taizu" while his posthumous name was Emper ...

(r. 202–195 BCE) came upon the treasury of

Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang (, ; 259–210 BC) was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first emperor of a unified China. Rather than maintain the title of "king" ( ''wáng'') borne by the previous Shang and Zhou rulers, he ruled as the First Emperor ( ...

(r. 221–210) at

Xianyang

Xianyang () is a prefecture-level city in central Shaanxi province, situated on the Wei River a few kilometers upstream (west) from the provincial capital of Xi'an. Once the capital of the Qin dynasty, it is now integrated into the Xi'an metrop ...

following the downfall of the

Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first Dynasties in Chinese history, dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin (state), ...

(221–206), he found an entire miniature musical orchestra of

puppet

A puppet is an object, often resembling a human, animal or Legendary creature, mythical figure, that is animated or manipulated by a person called a puppeteer. The puppeteer uses movements of their hands, arms, or control devices such as rods ...

s tall who played

mouth organs

A mouth organ is any free reed aerophone with one or more air chambers fitted with a free reed.

Though it spans many traditions, it is played universally the same way by the musician placing their lips over a chamber or holes in the instrument, an ...

if one pulled on ropes and blew into tubes to control them.

[Needham (1986c), 158.] Zhang Heng wrote in the 2nd century CE that people could be entertained by theatrical plays of artificial fish and dragons.

Later, the inventor

Ma Jun (

fl. 220–265) invented a theater of moving mechanical puppets powered by the rotation of a hidden waterwheel.

From literary sources it is known that the collapsible umbrella was invented during Wang Mang's reign, although the simple parasol existed beforehand. This employed sliding levers and bendable joints that could be protracted and retracted.

Modern archaeology has led to the discovery of Han artwork portraying inventions which were otherwise absent in Han literary sources. This includes the

crank handle. Han pottery tomb models of farmyards and

gristmill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and Wheat middlings, middlings. The term can refer to either the Mill (grinding), grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist i ...

s possess the first known depictions of crank handles, which were used to operate

the fans of winnowing machines.

[Needham (1986c), 116–119, 153–154 & Plate CLVI; Temple (1986), 46; Wang (1982), 57.] The machine was used to separate

chaff

Chaff (; ) is the dry, scaly protective casing of the seeds of cereal grains or similar fine, dry, scaly plant material (such as scaly parts of flowers or finely chopped straw). Chaff is indigestible by humans, but livestock can eat it. In agri ...

from grain, but the Chinese of later dynasties also employed the crank handle for silk-reeling, hemp-spinning, flour-sifting, and drawing water from a well using the

windlass

The windlass is an apparatus for moving heavy weights. Typically, a windlass consists of a horizontal cylinder (barrel), which is rotated by the turn of a crank or belt. A winch is affixed to one or both ends, and a cable or rope is wound arou ...

.

To measure distance traveled, the Han-era Chinese also created the

odometer

An odometer or odograph is an instrument used for measuring the distance traveled by a vehicle, such as a bicycle or car. The device may be electronic, mechanical, or a combination of the two (electromechanical). The noun derives from ancient Gr ...

cart. This invention is depicted in Han artwork by the 2nd century CE, yet detailed written descriptions were not offered until the 3rd century. The wheels of this device rotated a set of gears which in turn forced mechanical figures to bang gongs and drums that alerted the travelers of the distance traveled (measured in ''

li''). From existing specimens found at archaeological sites, it is known that Han-era craftsmen made use of the sliding metal

caliper

A caliper (British spelling also calliper, or in plurale tantum sense a pair of calipers) is a device used to measure the dimensions of an object.

Many types of calipers permit reading out a measurement on a ruled scale, a dial, or a digital dis ...

to make minute measurements. Although Han-era calipers bear incised inscriptions of the exact day of the year they were manufactured, they are not mentioned in any Han literary sources.

Uses of the waterwheel and water clock

By the Han dynasty, the Chinese developed various uses for the

waterwheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or buckets ...

. An improvement of the simple

lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or ''fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is div ...

-and-

fulcrum

A fulcrum is the support about which a lever pivots.

Fulcrum may also refer to:

Companies and organizations

* Fulcrum (Anglican think tank), a Church of England think tank

* Fulcrum Press, a British publisher of poetry

* Fulcrum Wheels, a bicy ...

tilt hammer device operated by one's foot, the hydraulic-powered

trip hammer

A trip hammer, also known as a tilt hammer or helve hammer, is a massive powered hammer. Traditional uses of trip hammers include pounding, decorticating and polishing of grain in agriculture. In mining, trip hammers were used for crushing meta ...

used for pounding,

decorticating, and polishing grain was first mentioned in the

Han dictionary ''

Jijiupian