Saladin (7527983360) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadhi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the

Shirkuh was in a power struggle over Egypt with Shawar and

Shirkuh was in a power struggle over Egypt with Shawar and

Leaving his brother

Leaving his brother

Saladin had by now agreed to truces with his Zengid rivals and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (the latter occurred in the summer of 1175), but faced a threat from the Isma'ili sect known as the

Saladin had by now agreed to truces with his Zengid rivals and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (the latter occurred in the summer of 1175), but faced a threat from the Isma'ili sect known as the

After leaving the an-Nusayriyah Mountains, Saladin returned to Damascus and had his Syrian soldiers return home. He left Turan Shah in command of Syria and left for Egypt with only his personal followers, reaching Cairo on 22 September. Having been absent for roughly two years, he had much to organize and supervise in Egypt, namely fortifying and reconstructing Cairo. The city walls were repaired and their extensions laid out, while the construction of the

After leaving the an-Nusayriyah Mountains, Saladin returned to Damascus and had his Syrian soldiers return home. He left Turan Shah in command of Syria and left for Egypt with only his personal followers, reaching Cairo on 22 September. Having been absent for roughly two years, he had much to organize and supervise in Egypt, namely fortifying and reconstructing Cairo. The city walls were repaired and their extensions laid out, while the construction of the

Saladin's intelligence services reported to him that the Crusaders were planning a raid into Syria. He ordered one of his generals, Farrukh-Shah, to guard the Damascus frontier with a thousand of his men to watch for an attack, then to retire, avoiding battle, and to light warning beacons on the hills, after which Saladin would march out. In April 1179, the Crusaders led by King Baldwin expected no resistance and waited to launch a surprise attack on Muslim herders grazing their herds and flocks east of the

Saladin's intelligence services reported to him that the Crusaders were planning a raid into Syria. He ordered one of his generals, Farrukh-Shah, to guard the Damascus frontier with a thousand of his men to watch for an attack, then to retire, avoiding battle, and to light warning beacons on the hills, after which Saladin would march out. In April 1179, the Crusaders led by King Baldwin expected no resistance and waited to launch a surprise attack on Muslim herders grazing their herds and flocks east of the

Saif al-Din had died earlier in June 1181 and his brother Izz al-Din inherited leadership of Mosul. On 4 December, the crown prince of the Zengids, as-Salih, died in Aleppo. Prior to his death, he had his chief officers swear an oath of loyalty to Izz al-Din, as he was the only Zengid ruler strong enough to oppose Saladin. Izz al-Din was welcomed in Aleppo, but possessing it and Mosul put too great of a strain on his abilities. He thus, handed Aleppo to his brother Imad al-Din Zangi, in exchange for

Saif al-Din had died earlier in June 1181 and his brother Izz al-Din inherited leadership of Mosul. On 4 December, the crown prince of the Zengids, as-Salih, died in Aleppo. Prior to his death, he had his chief officers swear an oath of loyalty to Izz al-Din, as he was the only Zengid ruler strong enough to oppose Saladin. Izz al-Din was welcomed in Aleppo, but possessing it and Mosul put too great of a strain on his abilities. He thus, handed Aleppo to his brother Imad al-Din Zangi, in exchange for

As Saladin approached Mosul, he faced the issue of taking over a large city and justifying the action. The Zengids of Mosul appealed to

As Saladin approached Mosul, he faced the issue of taking over a large city and justifying the action. The Zengids of Mosul appealed to

Saladin turned his attention from Mosul to Aleppo, sending his brother Taj al-Muluk Buri to capture Tell Khalid, 130 km northeast of the city. A siege was set, but the governor of Tell Khalid surrendered upon the arrival of Saladin himself on 17 May before a siege could take place. According to Imad ad-Din, after Tell Khalid, Saladin took a detour northwards to

Saladin turned his attention from Mosul to Aleppo, sending his brother Taj al-Muluk Buri to capture Tell Khalid, 130 km northeast of the city. A siege was set, but the governor of Tell Khalid surrendered upon the arrival of Saladin himself on 17 May before a siege could take place. According to Imad ad-Din, after Tell Khalid, Saladin took a detour northwards to

Crusader attacks provoked further responses by Saladin.

Crusader attacks provoked further responses by Saladin.

''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Upon the capture of Jerusalem, Saladin summoned the Jews and permitted them to resettle in the city. In particular, the residents of

, his account appears in T.A. Archer's ''The Crusade of Richard I'' (1889); Gillingham, John. ''The Life and Times of Richard I'' (1973) Baha ad-Din wrote: The armies of Saladin engaged in combat with the army of King Richard at the Battle of Arsuf on 7 September 1191, at which Saladin's forces suffered heavy losses and were forced to withdraw. After the battle of Arsuf, Richard occupied Jaffa, restoring the city's fortifications. Meanwhile, Saladin moved south, where he dismantled the fortifications of Ascalon to prevent this strategically important city, which lay at the junction between Egypt and Palestine, from falling into Crusader hands. In October 1191, Richard began restoring the inland castles on the coastal plain beyond Jaffa in preparation for an advance on Jerusalem. During this period, Richard and Saladin passed envoys back and forth, negotiating the possibility of a truce. Richard proposed that his sister

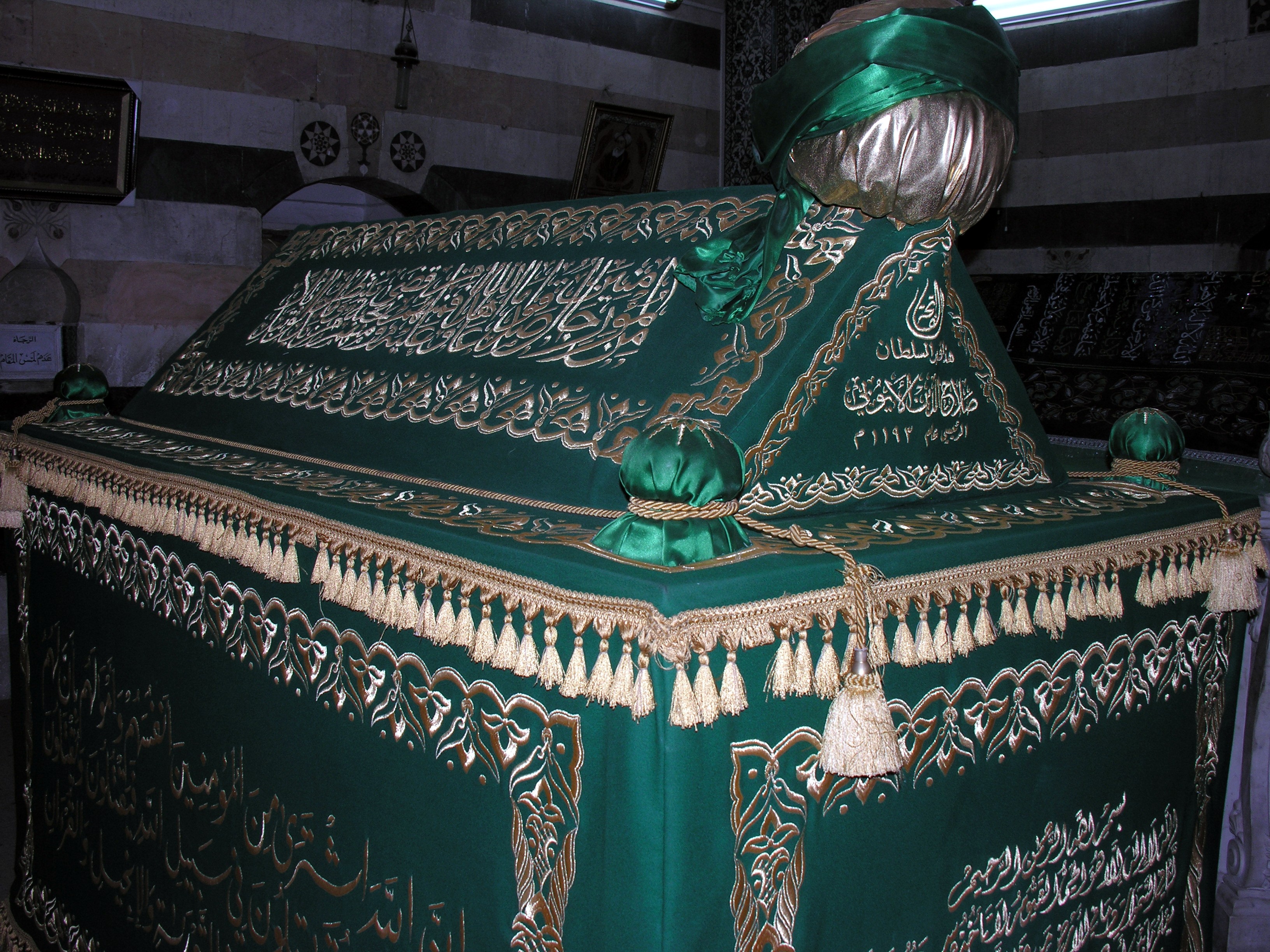

Saladin died of a fever on 4 March 1193 () at

Saladin died of a fever on 4 March 1193 () at

Saladin was widely renowned in medieval Europe as a model of kingship, and in particular of the courtly virtue of regal generosity. As early as 1202/03,

Saladin was widely renowned in medieval Europe as a model of kingship, and in particular of the courtly virtue of regal generosity. As early as 1202/03,

Saladin has become a prominent figure in

Saladin has become a prominent figure in

Stanley Lane-Poole, "The Life of Saladin and the Fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem", in "btm" format

Rosebault Ch.J. Saladin. Prince of Chivalri

A European account of Saladin's conquests of the Crusader states.

Richard and Saladin: Warriors of the Third Crusade

{{Authority control 1130s births 1193 deaths 12th-century Ayyubid sultans of Egypt 12th-century Ayyubid rulers 12th-century Muslims 12th-century Kurdish people Asharis Ayyubid emirs of Damascus Ayyubid sultans of Egypt Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques Viziers of the Fatimid Caliphate Kurdish Muslims Generals of the medieval Islamic world Mujaddid Muslims of the Second Crusade Muslims of the Third Crusade People from Tikrit Rulers of Yemen Kurdish Sunni Muslims Kurdish military personnel Infectious disease deaths in Syria

Ayyubid dynasty

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni ...

. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish languages

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern Kurdistan

**Eastern Kurdistan

**Northern Kurdistan

**Western Kurdistan

See also

* Kurd (dis ...

family, he was the first of both Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

. An important figure of the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity (Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

, he spearheaded the Muslim military effort against the Crusader states

The Crusader States, also known as Outremer, were four Catholic realms in the Middle East that lasted from 1098 to 1291. These feudal polities were created by the Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade through conquest and political in ...

in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

. At the height of his power, Ayyubid territorial control spanned Egypt, Syria, Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia is the name used for the Upland and lowland, uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, ...

, the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

, Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

, the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

, and Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), or ...

.

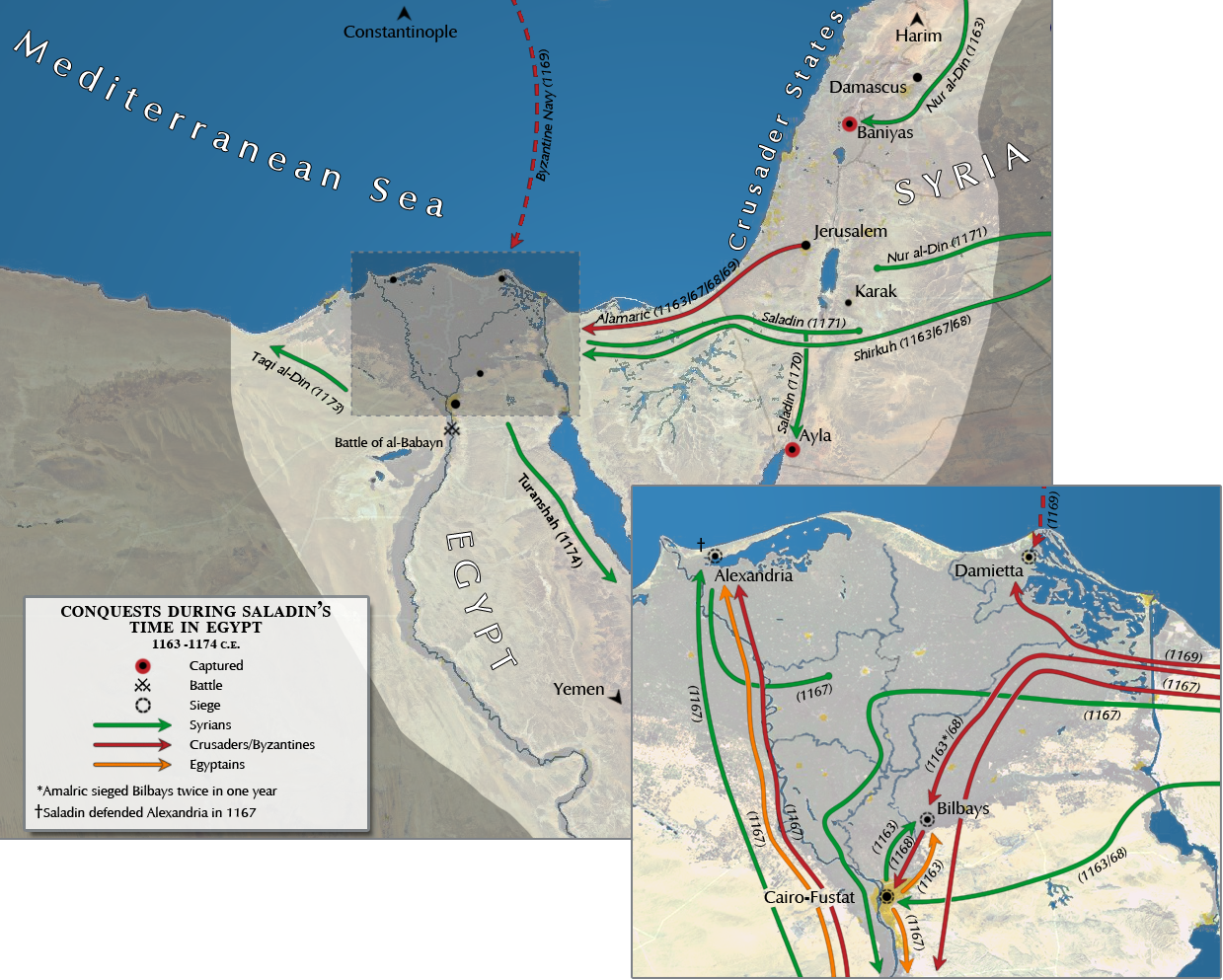

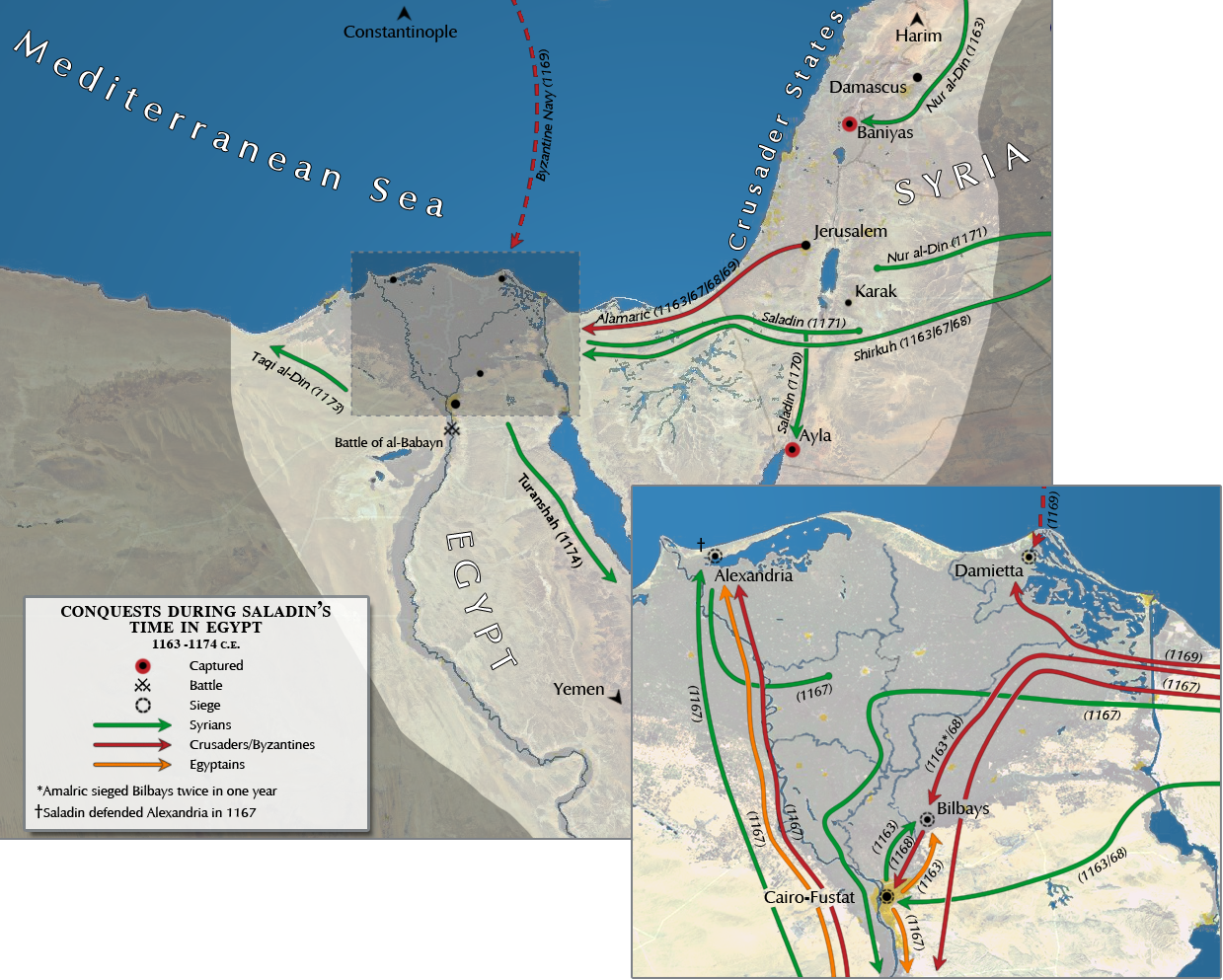

Alongside his uncle Shirkuh

Asad ad-Dīn Shīrkūh bin Shādhī (; ar, أسد الدين شيركوه بن شاذي), also known as Shirkuh, or Şêrko (meaning "lion of the mountains" in Kurdish) (died 22 February 1169) was a Kurdish military commander, and uncle of Salad ...

, a military general of the Zengid dynasty

The Zengid dynasty was a Muslim dynasty of Oghuz Turkic origin, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia on behalf of the Seljuk Empire and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to ...

, Saladin was sent to Egypt under the Fatimid Caliphate

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Isma'ilism, Ismaili Shia Islam, Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the ea ...

in 1164, on the orders of Nur ad-Din. With their original purpose being to help restore Shawar

Shawar ibn Mujir al-Sa'di ( ar, شاور بن مجير السعدي, Shāwar ibn Mujīr al-Saʿdī; died 18 January 1169) was an Arab ''de facto'' ruler of Fatimid Egypt, as its vizier, from December 1162 until his assassination in 1169 by the ge ...

as the to the teenage Fatimid caliph al-Adid

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh ibn Yūsuf ( ar, أبو محمد عبد الله بن يوسف; 1151–1171), better known by his regnal name al-ʿĀḍid li-Dīn Allāh ( ar, العاضد لدين الله, , Strengthener of God's Faith), was the ...

, a power struggle ensued between Shirkuh and Shawar after the latter was reinstated. Saladin, meanwhile, climbed the ranks of the Fatimid government by virtue of his military successes against Crusader assaults as well as his personal closeness to al-Adid. After Shawar was assassinated and Shirkuh died in 1169, al-Adid appointed Saladin as . During his tenure, Saladin, a Sunni Muslim

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word ''Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagree ...

, began to undermine the Fatimid establishment; following al-Adid's death in 1171, he abolished the Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

-based Shia Islamic Fatimid Caliphate and realigned his power with the Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

-based Sunni Islamic Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

.

In the following years, he led forays against the Crusaders in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, commissioned the successful conquest of Yemen, and staved off pro-Fatimid rebellions in Egypt. Not long after Nur ad-Din's death in 1174, Saladin launched his conquest of Syria, peacefully entering Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

at the request of its governor. By mid-1175, Saladin had conquered Hama

, timezone = EET

, utc_offset = +2

, timezone_DST = EEST

, utc_offset_DST = +3

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, ar ...

and Homs

Homs ( , , , ; ar, حِمْص / ALA-LC: ; Levantine Arabic: / ''Ḥomṣ'' ), known in pre-Islamic Syria as Emesa ( ; grc, Ἔμεσα, Émesa), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level ...

, inviting the animosity of other Zengid lords, who were the official rulers of Syria's various regions; he subsequently defeated the Zengids at the Battle of the Horns of Hama

The Battle of the Horns of Hama or Hammah ( ar, معركة قرون حماة, ''Qurun Hama'';( Kurdish: شەڕی قۆچەکانی حەمە, şerê qijikên hamayê) 13 April AD 1175; 19 Ramadan 570) was an Ayyubid victory over the Zen ...

in 1175, and was thereafter proclaimed the " Sultan of Egypt and Syria" by the Abbasid caliph al-Mustadi

Abu Muhammad Hassan ibn Yusuf al-Mustanjid ( ar, أبو محمد حسن بن يوسف المستنجد; 1142 – 27 March 1180) usually known by his regnal title Al-Mustadi ( ar, المستضيء بأمر الله) was the Abbasid Caliph in Baghd ...

. Saladin launched further conquests in northern Syria and Jazira

Jazira or Al-Jazira ( 'island'), or variants, may refer to:

Business

*Jazeera Airways, an airlines company based in Kuwait

Locations

* Al-Jazira, a traditional region known today as Upper Mesopotamia or the smaller region of Cizre

* Al-Jazira (c ...

, escaping two attempts on his life by the Order of Assassins

The Order of Assassins or simply the Assassins ( fa, حَشّاشین, Ḥaššāšīn, ) were a Nizārī Ismāʿīlī order and sect of Shīʿa Islam that existed between 1090 and 1275 CE. During that time, they lived in the mountains of P ...

, before returning to Egypt in 1177 to address local issues there. By 1182, Saladin had completed the conquest of Muslim Syria after capturing Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

, but ultimately failed to take over the Zengid stronghold of Mosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second large ...

.

Under Saladin's command, the Ayyubid army defeated the Crusaders at the decisive Battle of Hattin

The Battle of Hattin took place on 4 July 1187, between the Crusader states of the Levant and the forces of the Ayyubid sultan Saladin. It is also known as the Battle of the Horns of Hattin, due to the shape of the nearby extinct volcano of t ...

in 1187, capturing Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and re-establishing Muslim military dominance in the Levant. Although the Crusaders' Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establishe ...

continued to exist until the late 13th century, the defeat in 1187 marked a turning point in the Christian military effort against Muslim powers in the region. Saladin died in Damascus in 1193, having given away much of his personal wealth to his subjects; he is buried in a mausoleum adjacent to the Umayyad Mosque

The Umayyad Mosque ( ar, الجامع الأموي, al-Jāmiʿ al-Umawī), also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus ( ar, الجامع الدمشق, al-Jāmiʿ al-Damishq), located in the old city of Damascus, the capital of Syria, is one of the ...

. Alongside his significance to Muslim culture

Islamic culture and Muslim culture refer to cultural practices which are common to historically Islamic people. The early forms of Muslim culture, from the Rashidun Caliphate to the early Umayyad period and the early Abbasid period, were predomi ...

, Saladin is revered prominently in Kurdish culture

Kurdish culture is a group of distinctive cultural traits practiced by Kurdish people. The Kurdish culture is a legacy from ancient peoples who shaped modern Kurds and their society.

Kurds are an ethnic group mainly in Turkey, Iraq, and Iran. Th ...

, Turkic culture

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging to the ...

, and Arab culture

Arab culture is the culture of the Arabs, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. The various religions the Arab ...

. He has frequently been described as the most famous Kurdish figure in history.

Early life

Saladin was born inTikrit

Tikrit ( ar, تِكْرِيت ''Tikrīt'' , Syriac language, Syriac: ܬܲܓܪܝܼܬܼ ''Tagrīṯ'') is a city in Iraq, located northwest of Baghdad and southeast of Mosul on the Tigris River. It is the administrative center of the Saladin Gover ...

in present-day Iraq. His personal name was "Yusuf"; "Salah ad-Din" is a ''laqab

Arabic language names have historically been based on a long naming system. Many people from the Arabic-speaking and also Muslim countries have not had given/ middle/family names but rather a chain of names. This system remains in use throughout ...

'', an honorific epithet, meaning "Righteousness of the Faith". His family was most likely of Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish languages

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern Kurdistan

**Eastern Kurdistan

**Northern Kurdistan

**Western Kurdistan

See also

* Kurd (dis ...

ancestry,The medieval historian Ibn Athir relates a passage from another commander: "...both you and Saladin are Kurds and you will not let power pass into the hands of the Turks." Minorsky (1957): . and had originated from the village of Ajdanakan near the city of Dvin in central Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''Ox ...

. The Rawadiya tribe he hailed from had been partially assimilated into the Arabic-speaking world by this time. In Saladin's era, no scholar had more influence than sheikh Abdul Qadir Gilani

ʿAbdul Qādir Gīlānī, ( ar, عبدالقادر الجيلاني, ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī; fa, ) known by admirers as Muḥyī l-Dīn Abū Muḥammad b. Abū Sāliḥ ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī al-Baḡdādī al-Ḥasanī al-Ḥusayn ...

, and Saladin was strongly influenced and aided by him and his pupils. In 1132, the defeated army of Zengi, Atabeg of Mosul

This is a list of the rulers of the Iraqi city of Mosul.

Umayyad governors

* Muhammad ibn Marwan (ca. 685–705)

* Yusuf ibn Yahya ibn al-Hakam (ca. 685–705)

* Sa'id ibn Abd al-Malik (ca. 685–705)

* Yahya ibn Yahya al-Ghassani (719–720)

* ...

, found their retreat blocked by the Tigris River

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the P ...

opposite the fortress of Tikrit, where Saladin's father, Najm ad-Din Ayyub

al-Malik al-Afdal Najm al-Dīn Ayyūb ibn Shādhi ibn Marwān ( ar, الملك ألأفضل نجم الدين أيوب بن شاذي بن مروان Kurdish: Necmeddin Eyûbî) (died August 9, 1173) was a Kurdish soldier and politician from Dvin, ...

served as the warden. Ayyub provided ferries for the army and gave them refuge in Tikrit. Mujahid al-Din Bihruz, a former Greek slave who had been appointed as the military governor of northern Mesopotamia for his service to the Seljuks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

, reprimanded Ayyub for giving Zengi refuge and in 1137 banished Ayyub from Tikrit after his brother Asad al-Din Shirkuh

Asad ad-Dīn Shīrkūh bin Shādhī (; ar, أسد الدين شيركوه بن شاذي), also known as Shirkuh, or Şêrko (meaning "lion of the mountains" in Kurdish languages, Kurdish) (died 22 February 1169) was a Kurds, Kurdish military com ...

killed a friend of Bihruz. According to Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad

Bahāʾ al-Dīn Abū al-Maḥāsin Yūsuf ibn Rāfiʿ ibn Tamīm ( ar, بهاء الدين ابن شداد; the honorific title "Bahā' ad-Dīn" means "splendor of the faith"; sometimes known as Bohadin or Boha-Eddyn) (6 March 1145 – 8 Novem ...

, Saladin was born on the same night that his family left Tikrit. In 1139, Ayyub and his family moved to Mosul, where Imad ad-Din Zengi acknowledged his debt and appointed Ayyub commander of his fortress in Baalbek

Baalbek (; ar, بَعْلَبَكّ, Baʿlabakk, Syriac-Aramaic: ܒܥܠܒܟ) is a city located east of the Litani River in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley, about northeast of Beirut. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate. In Greek and Roman ...

. After the death of Zengi in 1146, his son, Nur ad-Din, became the regent of Aleppo and the leader of the Zengids

The Zengid dynasty was a Muslim dynasty of Oghuz Turkic origin, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia on behalf of the Seljuk Empire and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to ...

.

Saladin, who now lived in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

, was reported to have a particular fondness for the city, but information on his early childhood is scarce. About education, Saladin wrote "children are brought up in the way in which their elders were brought up". According to his biographers, Anne-Marie Eddé and al-Wahrani, Saladin was able to answer questions on Euclid

Euclid (; grc-gre, Wikt:Εὐκλείδης, Εὐκλείδης; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the ''Euclid's Elements, Elements'' trea ...

, the Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canoni ...

, arithmetic, and law, but this was an academic ideal. It was his knowledge of the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing. ...

and the "sciences of religion" that linked him to his contemporaries; several sources claim that during his studies he was more interested in religious studies than joining the military. Another factor which may have affected his interest in religion was that, during the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ru ...

, Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

was taken by the Christians. In addition to Islam, Saladin had a knowledge of the genealogies, biographies, and histories of the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

, as well as the bloodlines of Arabian horse

The Arabian or Arab horse ( ar, الحصان العربي , DIN 31635, DMG ''ḥiṣān ʿarabī'') is a horse breed, breed of horse that originated on the Arabian Peninsula. With a distinctive head shape and high tail carriage, the Arabian is ...

s. More significantly, he knew the ''Hamasah

The Hamasah (; ) is a genre of Arabic poetry that "recounts chivalrous exploits in the context of military glories and victories".

The first work in this genre is Kitab al-Hamasah of Abu Tammam.

Hamasah works

List of popular Hamasah works:

* ''Ha ...

'' of Abu Tammam

Ḥabīb ibn Aws al-Ṭā’ī (; ca. 796/807 - 845), better known by his sobriquet Abū Tammām (), was an Arab poet and Muslim convert born to Christian parents. He is best known in literature by his 9th-century compilation of early poems kn ...

by heart. He spoke Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish languages

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern Kurdistan

**Eastern Kurdistan

**Northern Kurdistan

**Western Kurdistan

See also

* Kurd (dis ...

and Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

and knew Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

and Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

.

Early expeditions

Saladin's military career began under the tutelage of his paternal uncleAsad al-Din Shirkuh

Asad ad-Dīn Shīrkūh bin Shādhī (; ar, أسد الدين شيركوه بن شاذي), also known as Shirkuh, or Şêrko (meaning "lion of the mountains" in Kurdish languages, Kurdish) (died 22 February 1169) was a Kurds, Kurdish military com ...

, a prominent military commander under Nur ad-Din, the Zengid emir of Damascus and Aleppo and the most influential teacher of Saladin. In 1163, the vizier

A vizier (; ar, وزير, wazīr; fa, وزیر, vazīr), or wazir, is a high-ranking political advisor or minister in the near east. The Abbasid caliphs gave the title ''wazir'' to a minister formerly called ''katib'' (secretary), who was a ...

to the Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dy ...

caliph al-Adid

Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh ibn Yūsuf ( ar, أبو محمد عبد الله بن يوسف; 1151–1171), better known by his regnal name al-ʿĀḍid li-Dīn Allāh ( ar, العاضد لدين الله, , Strengthener of God's Faith), was the ...

, Shawar

Shawar ibn Mujir al-Sa'di ( ar, شاور بن مجير السعدي, Shāwar ibn Mujīr al-Saʿdī; died 18 January 1169) was an Arab ''de facto'' ruler of Fatimid Egypt, as its vizier, from December 1162 until his assassination in 1169 by the ge ...

, had been driven out of Egypt by his rival Dirgham

Abu'l-Ashbāl al-Ḍirghām ibn ʿĀmir ibn Sawwār al-Lukhamī () () was an Arab military commander in the service of the Fatimid Caliphate. An excellent warrior and model cavalier, he rose to higher command and scored some successes against the ...

, a member of the powerful Banu Ruzzaik tribe. He asked for military backing from Nur ad-Din, who complied and, in 1164, sent Shirkuh to aid Shawar in his expedition against Dirgham. Saladin, at age 26, went along with them. After Shawar was successfully reinstated as vizier, he demanded that Shirkuh withdraw his army from Egypt for a sum of 30,000 gold dinar

The gold dinar ( ar, ﺩﻳﻨﺎﺭ ذهبي) is an Islamic medieval gold coin first issued in AH 77 (696–697 CE) by Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan. The weight of the dinar is 1 mithqal ().

The word ''dinar'' comes from the La ...

s, but he refused, insisting it was Nur ad-Din's will that he remain. Saladin's role in this expedition was minor, and it is known that he was ordered by Shirkuh to collect stores from Bilbais

Belbeis ( ar, بلبيس ; Bohairic cop, Ⲫⲉⲗⲃⲉⲥ/Ⲫⲉⲗⲃⲏⲥ ' is an ancient fortress city on the eastern edge of the southern Nile delta in Egypt, the site of the Ancient city and former bishopric of Phelbes and a Lat ...

prior to its siege by a combined force of Crusaders and Shawar's troops.

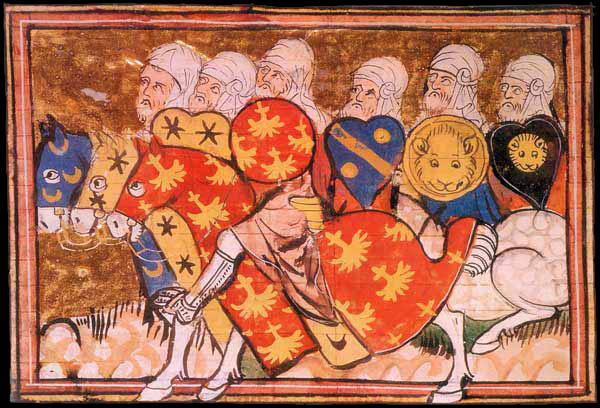

After the sacking of Bilbais, the Crusader-Egyptian force and Shirkuh's army were to engage in the Battle of al-Babein

The Battle of al-Babein took place on March 18, 1167, during the third Crusader invasion of Egypt. King Amalric I of Jerusalem, and a Zengid army under Shirkuh, both hoped to take the control of Egypt over from the Fatimid Caliphate. Saladin se ...

on the desert border of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

, just west of Giza

Giza (; sometimes spelled ''Gizah'' arz, الجيزة ' ) is the second-largest city in Egypt after Cairo and fourth-largest city in Africa after Kinshasa, Lagos and Cairo. It is the capital of Giza Governorate with a total population of 9.2 ...

. Saladin played a major role, commanding the right-wing of the Zengid army, while a force of Kurds commanded the left, and Shirkuh was stationed in the centre. Muslim sources at the time, however, put Saladin in the "baggage of the centre" with orders to lure the enemy into a trap by staging a feigned retreat

A feigned retreat is a military tactic, a type of feint, whereby a military force pretends to withdraw or to have been routed, in order to lure an enemy into a position of vulnerability.

A feigned retreat is one of the more difficult tactics fo ...

. The Crusader force enjoyed early success against Shirkuh's troops, but the terrain was too steep and sandy for their horses, and commander Hugh of Caesarea

Hugh Grenier (bef. 1139 – 1168/74) was the Lord of Caesarea from 1149/54 until his death. He was the younger son of Walter I Grenier and his wife, Julianne. His older brother, Eustace (II), was prevented by leprosy from inheriting the lordship ...

was captured while attacking Saladin's unit. After scattered fighting in little valleys to the south of the main position, the Zengid central force returned to the offensive; Saladin joined in from the rear.

The battle ended in a Zengid victory, and Saladin is credited with having helped Shirkuh in one of the "most remarkable victories in recorded history", according to Ibn al-Athir

Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ash-Shaybānī, better known as ʿAlī ʿIzz ad-Dīn Ibn al-Athīr al-Jazarī ( ar, علي عز الدین بن الاثیر الجزري) lived 1160–1233) was an Arab or Kurdish historian a ...

, although more of Shirkuh's men were killed and the battle is considered by most sources as not a total victory. Saladin and Shirkuh moved towards Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

where they were welcomed, given money and arms, and provided a base. Faced by a superior Crusader-Egyptian force attempting to besiege the city, Shirkuh split his army. He and the bulk of his force withdrew from Alexandria, while Saladin was left with the task of guarding the city.

In Egypt

Vizier of Egypt

Shirkuh was in a power struggle over Egypt with Shawar and

Shirkuh was in a power struggle over Egypt with Shawar and Amalric I of Jerusalem

Amalric or Amaury I ( la, Amalricus; french: Amaury; 113611 July 1174) was King of Jerusalem from 1163, and Count of Jaffa and Ascalon before his accession. He was the second son of Melisende and Fulk of Jerusalem, and succeeded his older broth ...

in which Shawar requested Amalric's assistance. In 1169, Shawar was reportedly assassinated by Saladin, and Shirkuh died later that year. Following his death, a number of candidates were considered for the role of vizier to al-Adid, most of whom were ethnic Kurds. Their ethnic solidarity came to shape the Ayyubid family's actions in their political career. Saladin and his close associates were wary of Turkish influence. On one occasion Isa al-Hakkari, a Kurdish lieutenant of Saladin, urged a candidate for the viziership, Emir Qutb al-Din al-Hadhbani, to step aside by arguing that "both you and Saladin are Kurds and you will not let the power pass into the hands of the Turks". Nur ad-Din chose a successor for Shirkuh, but al-Adid appointed Saladin to replace Shawar as vizier.

The reasoning behind the Shia caliph al-Adid's selection of Saladin, a Sunni, varies. Ibn al-Athir claims that the caliph chose him after being told by his advisers that "there is no one weaker or younger" than Saladin, and "not one of the emirs ommandersobeyed him or served him". However, according to this version, after some bargaining, he was eventually accepted by the majority of the emirs. Al-Adid's advisers were also suspected of promoting Saladin in an attempt to split the Syria-based Zengids. Al-Wahrani wrote that Saladin was selected because of the reputation of his family in their "generosity and military prowess". Imad ad-Din wrote that after the brief mourning period for Shirkuh, during which "opinions differed", the Zengid emirs decided upon Saladin and forced the caliph to "invest him as vizier". Although positions were complicated by rival Muslim leaders, the bulk of the Syrian commanders supported Saladin because of his role in the Egyptian expedition, in which he gained a record of military qualifications.

Inaugurated as vizier on 26 March, Saladin repented "wine-drinking and turned from frivolity to assume the dress of religion", according to Arabic sources of the time. Having gained more power and independence than ever before in his career, he still faced the issue of ultimate loyalty between al-Adid and Nur ad-Din. Later in the year, a group of Egyptian soldiers and emirs attempted to assassinate Saladin, but having already known of their intentions thanks to his intelligence chief Ali ibn Safyan, he had the chief conspirator, Naji, Mu'tamin al-Khilafa—the civilian controller of the Fatimid Palace—arrested and killed. The day after, 50,000 Black African soldiers from the regiments of the Fatimid army opposed to Saladin's rule, along with Egyptian emirs and commoners, staged a revolt. By 23 August, Saladin had decisively quelled the uprising, and never again had to face a military challenge from Cairo.

Towards the end of 1169, Saladin, with reinforcements from Nur ad-Din, defeated a massive Crusader-Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

force near Damietta

Damietta ( arz, دمياط ' ; cop, ⲧⲁⲙⲓⲁϯ, Tamiati) is a port city and the capital of the Damietta Governorate in Egypt, a former bishopric and present multiple Catholic titular see. It is located at the Damietta branch, an easter ...

. Afterwards, in the spring of 1170, Nur ad-Din sent Saladin's father to Egypt in compliance with Saladin's request, as well as encouragement from the Baghdad-based Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

caliph, al-Mustanjid

Abū'l-Muẓaffar Yusuf ibn Muhammad al-Muqtafi ( ar, أبو المظفّر يوسف بن محمد المقتفي; 1124 – 20 December 1170) better known by his regnal name Al-Mustanjid bi'llah ( ar, المستنجد بالله) was the Abbasid ...

, who aimed to pressure Saladin in deposing his rival caliph, al-Ad. Saladin himself had been strengthening his hold on Egypt and widening his support base there. He began granting his family members high-ranking positions in the region; he ordered the construction of a college for the Maliki

The ( ar, مَالِكِي) school is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas in the 8th century. The Maliki school of jurisprudence relies on the Quran and hadiths as primary ...

branch of Sunni Islam in the city, as well as one for the Shafi'i

The Shafii ( ar, شَافِعِي, translit=Shāfiʿī, also spelled Shafei) school, also known as Madhhab al-Shāfiʿī, is one of the four major traditional schools of religious law (madhhab) in the Sunnī branch of Islam. It was founded by ...

denomination to which he belonged in al-Fustat

Fusṭāṭ ( ar, الفُسطاط ''al-Fusṭāṭ''), also Al-Fusṭāṭ and Fosṭāṭ, was the first capital of Egypt under Muslim rule, and the historical centre of modern Cairo. It was built adjacent to what is now known as Old Cairo by t ...

.

After establishing himself in Egypt, Saladin launched a campaign against the Crusaders, besieging Darum

Deir al-Balah or Deir al Balah ( ar, دير البلح, , Monastery of the Date Palm) is a Palestinian people, Palestinian city in the central Gaza Strip and the administrative capital of the Deir el-Balah Governorate. It is located over south o ...

in 1170. Amalric withdrew his Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

garrison from Gaza to assist him in defending Darum, but Saladin evaded their force and captured Gaza in 1187. In 1191 Saladin destroyed the fortifications in Gaza built by King Baldwin III for the Knights Templar. It is unclear exactly when, but during that same year, he attacked and captured the Crusader castle of Eilat

Eilat ( , ; he, אֵילַת ; ar, إِيلَات, Īlāt) is Israel's southernmost city, with a population of , a busy port and popular resort at the northern tip of the Red Sea, on what is known in Israel as the Gulf of Eilat and in Jordan ...

, built on an island off the head of the Gulf of Aqaba

The Gulf of Aqaba ( ar, خَلِيجُ ٱلْعَقَبَةِ, Khalīj al-ʿAqabah) or Gulf of Eilat ( he, מפרץ אילת, Mifrátz Eilát) is a large gulf at the northern tip of the Red Sea, east of the Sinai Peninsula and west of the Arabian ...

. It did not pose a threat to the passage of the Muslim navy but could harass smaller parties of Muslim ships, and Saladin decided to clear it from his path.

Sultan of Egypt

According to Imad ad-Din, Nur ad-Din wrote to Saladin in June 1171, telling him to reestablish the Abbasid caliphate in Egypt, which Saladin coordinated two months later after additional encouragement byNajm ad-Din al-Khabushani Najm () or Najam (also Negm, in Egyptian Arabic, Egyptian dialect / pronunciation) is an Arabic word meaning ''MORNING STAR''. It is used as a given name in Middle East, Central Asia and South Asia. Najm is the male version of the name and Najma ( ...

, the Shafi'i '' faqih'', who vehemently opposed Shia rule in the country. Several Egyptian emirs were thus killed, but al-Adid was told that they were killed for rebelling against him. He then fell ill or was poisoned according to one account. While ill, he asked Saladin to pay him a visit to request that he take care of his young children, but Saladin refused, fearing treachery against the Abbasids, and is said to have regretted his action after realizing what al-Adid had wanted. He died on 13 September, and five days later, the Abbasid ''khutba

''Khutbah'' ( ar, خطبة ''khuṭbah'', tr, hutbe) serves as the primary formal occasion for public preaching in the Islamic tradition.

Such sermons occur regularly, as prescribed by the teachings of all legal schools. The Islamic traditi ...

'' was pronounced in Cairo and al-Fustat, proclaiming al-Mustadi

Abu Muhammad Hassan ibn Yusuf al-Mustanjid ( ar, أبو محمد حسن بن يوسف المستنجد; 1142 – 27 March 1180) usually known by his regnal title Al-Mustadi ( ar, المستضيء بأمر الله) was the Abbasid Caliph in Baghd ...

as caliph.

On 25 September, Saladin left Cairo to take part in a joint attack on Kerak

Al-Karak ( ar, الكرك), is a city in Jordan known for its medieval castle, the Kerak Castle. The castle is one of the three largest castles in the region, the other two being in Syria. Al-Karak is the capital city of the Karak Governorate.

...

and Montréal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple-p ...

, the desert castles of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, with Nur ad-Din who would attack from Syria. Prior to arriving at Montreal, Saladin however withdrew back to Cairo as he received the reports that in his absence the Crusader leaders had increased their support to the traitors inside Egypt to attack Saladin from within and lessen his power, especially the Fatimid who started plotting to restore their past glory. Because of this, Nur ad-Din went on alone.''Dastan Iman Faroshon Ki'' by Inayatullah Iltumish, 2011, pp. 128–34.

During the summer of 1173, a Nubia

Nubia () (Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sudan), or ...

n army along with a contingent of Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian Diaspora, Armenian communities across the ...

former Fatimid troops were reported on the Egyptian border, preparing for a siege against Aswan

Aswan (, also ; ar, أسوان, ʾAswān ; cop, Ⲥⲟⲩⲁⲛ ) is a city in Southern Egypt, and is the capital of the Aswan Governorate.

Aswan is a busy market and tourist centre located just north of the Aswan Dam on the east bank of the ...

. The emir of the city had requested Saladin's assistance and was given reinforcements under Turan-Shah

Shams ad-Din Turanshah ibn Ayyub al-Malik al-Mu'azzam Shams ad-Dawla Fakhr ad-Din known simply as Turanshah ( ar, توران شاه بن أيوب) (died 27 June 1180) was the Ayyubid emir (prince) of Yemen (1174–1176), Damascus (1176–1179), Ba ...

, Saladin's brother. Consequently, the Nubians departed; but returned in 1173 and were again driven off. This time, Egyptian forces advanced from Aswan and captured the Nubian town of Ibrim

Qasr Ibrim ( ar, قصر ابريم; Meroitic: ''Pedeme''; Old Nubian: ''Silimi''; Coptic: ⲡⲣⲓⲙ ''Prim''; Latin: ''Primis'') is an archaeological site in Lower Nubia, located in the modern country of Egypt. The site has a long history of ...

. Saladin sent a gift to Nur ad-Din, who had been his friend and teacher, 60,000 dinars, "wonderful manufactured goods", some jewels, and an elephant. While transporting these goods to Damascus, Saladin took the opportunity to ravage the Crusader countryside. He did not press an attack against the desert castles but attempted to drive out the Muslim Bedouins who lived in Crusader territory with the aim of depriving the Franks of guides.

On 31 July 1173, Saladin's father Ayyub was wounded in a horse-riding accident, ultimately causing his death on 9 August. In 1174, Saladin sent Turan-Shah to conquer Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

to allocate it and its port Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 people. ...

to the territories of the Ayyubid Dynasty

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni ...

.

Conquest of Syria

Conquest of Damascus

In the early summer of 1174, Nur ad-Din was mustering an army, sending summons to Mosul,Diyar Bakr

Diyar Bakr ( ar, دِيَارُ بَكرٍ, Diyār Bakr, abode of Bakr) is the medieval Arabic name of the northernmost of the three provinces of the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia), the other two being Diyar Mudar and Diyar Rabi'a. According to the m ...

, and the Jazira

Jazira or Al-Jazira ( 'island'), or variants, may refer to:

Business

*Jazeera Airways, an airlines company based in Kuwait

Locations

* Al-Jazira, a traditional region known today as Upper Mesopotamia or the smaller region of Cizre

* Al-Jazira (c ...

in an apparent preparation of an attack against Saladin's Egypt. The Ayyubids held a council upon the revelation of these preparations to discuss the possible threat and Saladin collected his own troops outside Cairo. On 15 May, Nur ad-Din died after falling ill the previous week and his power was handed to his eleven-year-old son as-Salih Ismail al-Malik

As-Salih Ismaʿil al-Malik (1163–1181) was an emir of Damascus and emir of Aleppo in 1174, the son of Nur ad-Din.

Biography

He was only eleven years old when his father died in 1174. As-Salih came under the protection of the eunuch Gümüs ...

. His death left Saladin with political independence and in a letter to as-Salih, he promised to "act as a sword" against his enemies and referred to the death of his father as an "earthquake shock".

In the wake of Nur ad-Din's death, Saladin faced a difficult decision; he could move his army against the Crusaders from Egypt or wait until invited by as-Salih in Syria to come to his aid and launch a war from there. He could also take it upon himself to annex Syria before it could possibly fall into the hands of a rival, but he feared that attacking a land that formerly belonged to his master—forbidden in the Islamic principles in which he believed—could portray him as hypocritical, thus making him unsuitable for leading the war against the Crusaders. Saladin saw that in order to acquire Syria, he needed either an invitation from as-Salih or to warn him that potential anarchy could give rise to danger from the Crusaders.

When as-Salih was removed to Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

in August, Gumushtigin, the emir of the city and a captain of Nur ad-Din's veterans assumed guardianship over him. The emir prepared to unseat all his rivals in Syria and the Jazira, beginning with Damascus. In this emergency, the emir of Damascus appealed to Saif al-Din of Mosul (a cousin of Gumushtigin) for assistance against Aleppo, but he refused, forcing the Syrians to request the aid of Saladin, who complied. Saladin rode across the desert with 700 picked horsemen, passing through al-Kerak then reaching Bosra

Bosra ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ, Buṣrā), also spelled Bostra, Busrana, Bozrah, Bozra and officially called Busra al-Sham ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ ٱلشَّام, Buṣrā al-Shām), is a town in southern Syria, administratively belonging to the Dara ...

. According to his own account, was joined by "emirs, soldiers, and Bedouins—the emotions of their hearts to be seen on their faces." On 23 November, he arrived in Damascus amid general acclamation and rested at his father's old home there, until the gates of the Citadel of Damascus

The Citadel of Damascus ( ar, قلعة دمشق, Qalʿat Dimašq) is a large medieval fortified palace and citadel in Damascus, Syria. It is part of the Ancient City of Damascus, which was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979.

The loc ...

, whose commander Raihan initially refused to surrender, were opened to Saladin four days later, after a brief siege by his brother Tughtakin ibn Ayyub

Al-Malik al-Aziz Sayf al-Islam Tughtakin Ahmad ibn Ayyub ( ar, الملك العزيز سيف الإسلام طغتكين أحمد ابن أيوب; also known simply as Sayf al-Islam) was the second Ayyubid emir (prince) of Yemen and Arabia between ...

. He installed himself in the castle and received the homage and salutations of the inhabitants.

Further conquests in Syria

Leaving his brother

Leaving his brother Tughtakin ibn Ayyub

Al-Malik al-Aziz Sayf al-Islam Tughtakin Ahmad ibn Ayyub ( ar, الملك العزيز سيف الإسلام طغتكين أحمد ابن أيوب; also known simply as Sayf al-Islam) was the second Ayyubid emir (prince) of Yemen and Arabia between ...

as Governor of Damascus, Saladin proceeded to reduce other cities that had belonged to Nur al-Din, but were now practically independent. His army conquered Hama

, timezone = EET

, utc_offset = +2

, timezone_DST = EEST

, utc_offset_DST = +3

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, ar ...

with relative ease, but avoided attacking Homs

Homs ( , , , ; ar, حِمْص / ALA-LC: ; Levantine Arabic: / ''Ḥomṣ'' ), known in pre-Islamic Syria as Emesa ( ; grc, Ἔμεσα, Émesa), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level ...

because of the strength of its citadel. Saladin moved north towards Aleppo, besieging it on 30 December after Gumushtigin refused to abdicate his throne. As-Salih, fearing capture by Saladin, came out of his palace and appealed to the inhabitants not to surrender him and the city to the invading force. One of Saladin's chroniclers claimed "the people came under his spell".

Gumushtigin requested Rashid ad-Din Sinan

Rashid al-Din Sinan ( ar, رشيد الدين سنان ''Rashīd ad-Dīn Sinān''; 1131/1135 – 1193) also known as the Old Man of the Mountain ( ar, شيخ الجبل ''Shaykh al-Jabal'', la, Vetulus de Montanis), was a ''da'i'' (missionary) a ...

, chief ''da'i'' of the Assassins

An assassin is a person who commits targeted murder.

Assassin may also refer to:

Origin of term

* Someone belonging to the medieval Persian Ismaili order of Assassins

Animals and insects

* Assassin bugs, a genus in the family ''Reduviida ...

of Syria, who were already at odds with Saladin since he replaced the Fatimids of Egypt, to assassinate Saladin in his camp. On 11 May 1175, a group of thirteen Assassins easily gained admission into Saladin's camp, but were detected immediately before they carried out their attack by Nasih al-Din Khumartekin of Abu Qubays. One was killed by one of Saladin's generals and the others were slain while trying to escape. To deter Saladin's progress, Raymond of Tripoli gathered his forces by Nahr al-Kabir

The Nahr al-Kabir, also known in Syria as al-Nahr al-Kabir al-Janoubi ( ar, النهر الكبير الجنوبي, lit=the southern great river, by contrast with the Nahr al-Kabir al-Shamali) or in Lebanon simply as the Kebir, is a river in Syria ...

, where they were well placed for an attack on Muslim territory. Saladin later moved toward Homs

Homs ( , , , ; ar, حِمْص / ALA-LC: ; Levantine Arabic: / ''Ḥomṣ'' ), known in pre-Islamic Syria as Emesa ( ; grc, Ἔμεσα, Émesa), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level ...

instead, but retreated after being told a relief force was being sent to the city by Saif al-Din.

Meanwhile, Saladin's rivals in Syria and Jazira waged a propaganda war against him, claiming he had "forgotten his own condition ervant of Nur ad-Din and showed no gratitude for his old master by besieging his son, rising "in rebellion against his Lord". Saladin aimed to counter this propaganda by ending the siege, claiming that he was defending Islam from the Crusaders; his army returned to Hama to engage a Crusader force there. The Crusaders withdrew beforehand and Saladin proclaimed it "a victory opening the gates of men's hearts". Soon after, Saladin entered Homs and captured its citadel in March 1175, after stubborn resistance from its defenders.

Saladin's successes alarmed Saif al-Din. As head of the Zengid

The Zengid dynasty was a Muslim dynasty of Oghuz Turkic origin, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia on behalf of the Seljuk Empire and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to ...

s, including Gumushtigin, he regarded Syria and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

as his family estate and was angered when Saladin attempted to usurp his dynasty's holdings. Saif al-Din mustered a large army and dispatched it to Aleppo, whose defenders anxiously had awaited them. The combined forces of Mosul and Aleppo marched against Saladin in Hama. Heavily outnumbered, Saladin initially attempted to make terms with the Zengids by abandoning all conquests north of the Damascus province, but they refused, insisting he returns to Egypt. Seeing that confrontation was unavoidable, Saladin prepared for battle, taking up a superior position at the Horns of Hama, hills by the gorge of the Orontes River

The Orontes (; from Ancient Greek , ) or Asi ( ar, العاصي, , ; tr, Asi) is a river with a length of in Western Asia that begins in Lebanon, flowing northwards through Syria before entering the Mediterranean Sea near Samandağ in Turkey.

...

. On 13 April 1175, the Zengid troops marched to attack his forces, but soon found themselves surrounded by Saladin's Ayyubid veterans, who crushed them. The battle ended in a decisive victory for Saladin, who pursued the Zengid fugitives to the gates of Aleppo, forcing as-Salih's advisers to recognize Saladin's control of the provinces of Damascus, Homs, and Hama, as well as a number of towns outside Aleppo such as Ma'arat al-Numan

Maarat al-Numan ( ar, مَعَرَّةُ النُّعْمَانِ, Maʿarrat an-Nuʿmān), also known as al-Ma'arra, is a city in northwestern Syria, south of Idlib and north of Hama, with a population of about 58,008 before the Civil War (2004 ...

.

After his victory against the Zengids, Saladin proclaimed himself king and suppressed the name of as-Salih in Friday prayers and Islamic coinage. From then on, he ordered prayers in all the mosques of Syria and Egypt as the sovereign king and he issued at the Cairo mint gold coins bearing his official title—''al-Malik an-Nasir Yusuf Ayyub, ala ghaya'' "the King Strong to Aid, Joseph son of Job; exalted be the standard." The Abbasid caliph in Baghdad graciously welcomed Saladin's assumption of power and declared him "Sultan of Egypt and Syria". The Battle of Hama did not end the contest for power between the Ayyubids and the Zengids, with the final confrontation occurring in the spring of 1176. Saladin had gathered massive reinforcements from Egypt while Saif al-Din was levying troops among the minor states of Diyarbakir and al-Jazira. When Saladin crossed the Orontes, leaving Hama, the sun was eclipsed. He viewed this as an omen, but he continued his march north. He reached the Sultan's Mound, roughly from Aleppo, where his forces encountered Saif al-Din's army. A hand-to-hand fight ensued and the Zengids managed to plough Saladin's left-wing, driving it before him when Saladin himself charged at the head of the Zengid guard. The Zengid forces panicked and most of Saif al-Din's officers ended up being killed or captured—Saif al-Din narrowly escaped. The Zengid army's camp, horses, baggage, tents, and stores were seized by the Ayyubids. The Zengid prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

, however, were given gifts and freed. All of the booty from the Ayyubid victory was accorded to the army, Saladin not keeping anything himself.

He continued towards Aleppo, which still closed its gates to him, halting before the city. On the way, his army took Buza'a and then captured Manbij

Manbij ( ar, مَنْبِج, Manbiǧ, ku, مەنبج, Minbic, tr, Münbiç, Menbic, or Menbiç) is a city in the northeast of Aleppo Governorate in northern Syria, 30 kilometers (19 mi) west of the Euphrates. In the 2004 census by the Cent ...

. From there, they headed west to besiege the fortress of A'zaz

Azaz ( ar, أَعْزَاز, ʾAʿzāz) is a city in northwest Syria, roughly north-northwest of Aleppo. According to the Syria Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), Azaz had a population of 31,623 in the 2004 census.

on 15 May. Several days later, while Saladin was resting in one of his captain's tents, an Assassin rushed forward at him and struck at his head with a knife. The cap of his head armour was not penetrated and he managed to grip the Assassin's hand—the dagger only slashing his gambeson

A gambeson (also aketon, padded jack, pourpoint, or arming doublet) is a padded defensive jacket, worn as armour separately, or combined with mail or plate armour. Gambesons were produced with a sewing technique called quilting. They were usual ...

—and the assailant was soon killed. Saladin was unnerved at the attempt on his life, which he accused Gumushtugin and the Assassins of plotting, and so increased his efforts in the siege.

A'zaz capitulated on 21 June, and Saladin then hurried his forces to Aleppo to punish Gumushtigin. His assaults were again resisted, but he managed to secure not only a truce, but a mutual alliance with Aleppo, in which Gumushtigin and as-Salih were allowed to continue their hold on the city, and in return, they recognized Saladin as the sovereign over all of the dominions he conquered. The ''emirs'' of Mardin

Mardin ( ku, Mêrdîn; ar, ماردين; syr, ܡܪܕܝܢ, Merdīn; hy, Մարդին) is a city in southeastern Turkey. The capital of Mardin Province, it is known for the Artuqid architecture of its old city, and for its strategic location on ...

and Keyfa, the Muslim allies of Aleppo, also recognised Saladin as the King of Syria. When the treaty was concluded, the younger sister of as-Salih came to Saladin and requested the return of the Fortress of A'zaz; he complied and escorted her back to the gates of Aleppo with numerous presents.

Campaign against the Assassins

Saladin had by now agreed to truces with his Zengid rivals and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (the latter occurred in the summer of 1175), but faced a threat from the Isma'ili sect known as the

Saladin had by now agreed to truces with his Zengid rivals and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (the latter occurred in the summer of 1175), but faced a threat from the Isma'ili sect known as the Assassins

An assassin is a person who commits targeted murder.

Assassin may also refer to:

Origin of term

* Someone belonging to the medieval Persian Ismaili order of Assassins

Animals and insects

* Assassin bugs, a genus in the family ''Reduviida ...

, led by Rashid ad-Din Sinan

Rashid al-Din Sinan ( ar, رشيد الدين سنان ''Rashīd ad-Dīn Sinān''; 1131/1135 – 1193) also known as the Old Man of the Mountain ( ar, شيخ الجبل ''Shaykh al-Jabal'', la, Vetulus de Montanis), was a ''da'i'' (missionary) a ...

. Based in the an-Nusayriyah Mountains

The Coastal Mountain Range ( ar, سلسلة الجبال الساحلية ''Silsilat al-Jibāl as-Sāḥilīyah'') also called Al-Anṣariyyah is a mountain range in northwestern Syria running north–south, parallel to the coastal plain.Federal ...

, they commanded nine fortresses

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

, all built on high elevations. As soon as he dispatched the bulk of his troops to Egypt, Saladin led his army into the an-Nusayriyah range in August 1176. He retreated the same month, after laying waste to the countryside, but failing to conquer any of the forts. Most Muslim historians claim that Saladin's uncle, the governor of Hama, mediated a peace agreement between him and Sinan.

Saladin had his guards supplied with link lights and had chalk and cinders strewed around his tent outside Masyaf

Masyaf ( ar, مصياف ') is a city in northwestern Syria. It is the center of the Masyaf District in the Hama Governorate. As of 2004, Masyaf had a religiously diverse population of approximately 22,000 Ismailis, Alawites and Christians. The ci ...

—which he was besieging—to detect any footsteps by the Assassins. According to this version, one night Saladin's guards noticed a spark glowing down the hill of Masyaf and then vanishing among the Ayyubid tents. Presently, Saladin awoke to find a figure leaving the tent. He saw that the lamps were displaced and beside his bed laid hot scones of the shape peculiar to the Assassins with a note at the top pinned by a poisoned dagger. The note threatened that he would be killed if he did not withdraw from his assault. Saladin gave a loud cry, exclaiming that Sinan himself was the figure that had left the tent.

Another version claims that Saladin hastily withdrew his troops from Masyaf because they were urgently needed to fend off a Crusader force in the vicinity of Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

. In reality, Saladin sought to form an alliance with Sinan and his Assassins, consequently depriving the Crusaders of a potent ally against him. Viewing the expulsion of the Crusaders as a mutual benefit and priority, Saladin and Sinan maintained cooperative relations afterwards, the latter dispatching contingents of his forces to bolster Saladin's army in a number of decisive subsequent battlefronts.

Return to Cairo and forays in Palestine

After leaving the an-Nusayriyah Mountains, Saladin returned to Damascus and had his Syrian soldiers return home. He left Turan Shah in command of Syria and left for Egypt with only his personal followers, reaching Cairo on 22 September. Having been absent for roughly two years, he had much to organize and supervise in Egypt, namely fortifying and reconstructing Cairo. The city walls were repaired and their extensions laid out, while the construction of the

After leaving the an-Nusayriyah Mountains, Saladin returned to Damascus and had his Syrian soldiers return home. He left Turan Shah in command of Syria and left for Egypt with only his personal followers, reaching Cairo on 22 September. Having been absent for roughly two years, he had much to organize and supervise in Egypt, namely fortifying and reconstructing Cairo. The city walls were repaired and their extensions laid out, while the construction of the Cairo Citadel

The Citadel of Cairo or Citadel of Saladin ( ar, قلعة صلاح الدين, Qalaʿat Salāḥ ad-Dīn) is a medieval Islamic-era fortification in Cairo, Egypt, built by Salah ad-Din (Saladin) and further developed by subsequent Egyptian ruler ...

was commenced. The deep Bir Yusuf ("Joseph's Well") was built on Saladin's orders. The chief public work he commissioned outside of Cairo was the large bridge at Giza

Giza (; sometimes spelled ''Gizah'' arz, الجيزة ' ) is the second-largest city in Egypt after Cairo and fourth-largest city in Africa after Kinshasa, Lagos and Cairo. It is the capital of Giza Governorate with a total population of 9.2 ...

, which was intended to form an outwork of defence against a potential Moorish

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or se ...

invasion.

Saladin remained in Cairo supervising its improvements, building colleges such as the Madrasa of the Sword Makers and ordering the internal administration of the country. In November 1177, he set out upon a raid into Palestine; the Crusaders had recently forayed into the territory of Damascus, so Saladin saw the truce as no longer worth preserving. The Christians sent a large portion of their army to besiege the fortress of Harim north of Aleppo, so southern Palestine bore few defenders. Saladin found the situation ripe and marched to Ascalon, which he referred to as the "Bride of Syria". William of Tyre

William of Tyre ( la, Willelmus Tyrensis; 113029 September 1186) was a medieval prelate and chronicler. As archbishop of Tyre, he is sometimes known as William II to distinguish him from his predecessor, William I, the Englishman, a former ...

recorded that the Ayyubid army consisted of soldiers, of which 8,000 were elite forces and were black soldiers from Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

. This army proceeded to raid the countryside, sack Ramla

Ramla or Ramle ( he, רַמְלָה, ''Ramlā''; ar, الرملة, ''ar-Ramleh'') is a city in the Central District of Israel. Today, Ramle is one of Israel's mixed cities, with both a significant Jewish and Arab populations.

The city was f ...

and Lod, and disperse themselves as far as the Gates of Jerusalem.

Battles and truce with Baldwin

The Ayyubids allowed Baldwin IV of Jerusalem to enter Ascalon with his Gaza-basedKnights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

without taking any precautions against a sudden attack. Although the Crusader force consisted of only 375 knights, Saladin hesitated to ambush them because of the presence of highly skilled generals. On 25 November, while the greater part of the Ayyubid army was absent, Saladin and his men were surprised near Ramla in the battle of Montgisard

The Battle of Montgisard was fought between the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Ayyubids on 25 November 1177 at Montgisard, in the Levant between Ramla and Yibna. The 16-year-old Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, seriously afflicted by leprosy, led an out ...

(possibly at Gezer

Gezer, or Tel Gezer ( he, גֶּזֶר), in ar, تل الجزر – Tell Jezar or Tell el-Jezari is an archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (eithe ...

, also known as Tell Jezar). Before they could form up, the Templar force hacked the Ayyubid army down. Initially, Saladin attempted to organize his men into battle order, but as his bodyguards were being killed, he saw that defeat was inevitable and so with a small remnant of his troops mounted a swift camel, riding all the way to the territories of Egypt.

Not discouraged by his defeat at Montgisard, Saladin was prepared to fight the Crusaders once again. In the spring of 1178, he was encamped under the walls of Homs, and a few skirmishes occurred between his generals and the Crusader army. His forces in Hama won a victory over their enemy and brought the spoils, together with many prisoners of war, to Saladin who ordered the captives to be beheaded for "plundering and laying waste the lands of the Faithful". He spent the rest of the year in Syria without a confrontation with his enemies.

Saladin's intelligence services reported to him that the Crusaders were planning a raid into Syria. He ordered one of his generals, Farrukh-Shah, to guard the Damascus frontier with a thousand of his men to watch for an attack, then to retire, avoiding battle, and to light warning beacons on the hills, after which Saladin would march out. In April 1179, the Crusaders led by King Baldwin expected no resistance and waited to launch a surprise attack on Muslim herders grazing their herds and flocks east of the

Saladin's intelligence services reported to him that the Crusaders were planning a raid into Syria. He ordered one of his generals, Farrukh-Shah, to guard the Damascus frontier with a thousand of his men to watch for an attack, then to retire, avoiding battle, and to light warning beacons on the hills, after which Saladin would march out. In April 1179, the Crusaders led by King Baldwin expected no resistance and waited to launch a surprise attack on Muslim herders grazing their herds and flocks east of the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights ( ar, هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or ; he, רמת הגולן, ), or simply the Golan, is a region in the Levant spanning about . The region defined as the Golan Heights differs between di ...

. Baldwin advanced too rashly in pursuit of Farrukh-Shah's force, which was concentrated southeast of Quneitra

, ''Qunayṭrawi'' or ''Qunayṭirawi''

, population_density_metro_sq_mi =

, population_urban =

, population_density_urban_km2 =

, population_density_urban_sq_mi =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_bla ...

and was subsequently defeated by the Ayyubids. With this victory, Saladin decided to call in more troops from Egypt; he requested al-Adil

Al-Adil I ( ar, العادل, in full al-Malik al-Adil Sayf ad-Din Abu-Bakr Ahmed ibn Najm ad-Din Ayyub, ar, الملك العادل سيف الدين أبو بكر بن أيوب, "Ahmed, son of Najm ad-Din Ayyub, father of Bakr, the Just K ...

to dispatch 1,500 horsemen.

In the summer of 1179, King Baldwin had set up an outpost on the road to Damascus and aimed to fortify a passage over the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

, known as Jacob's Ford

Daughters of Jacob Bridge ( he, גשר בנות יעקב, ''Gesher Bnot Ya'akov''; ar, جسر بنات يعقوب, ''Jisr Benat Ya'kub''). is a bridge that spans the last natural ford of the Jordan at the southern end of the Hula Basin between ...

, that commanded the approach to the Banias

Banias or Banyas ( ar, بانياس الحولة; he, בניאס, label=Modern Hebrew; Judeo-Aramaic, Medieval Hebrew: פמייס, etc.; grc, Πανεάς) is a site in the Golan Heights near a natural spring, once associated with the Greek ...

plain (the plain was divided by the Muslims and the Christians). Saladin had offered 100,000 gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

pieces to Baldwin to abandon the project, which was particularly offensive to the Muslims, but to no avail. He then resolved to destroy the fortress, called Chastellet and defended by the Templars, moving his headquarters to Banias. As the Crusaders hurried down to attack the Muslim forces, they fell into disorder, with the infantry falling behind. Despite early success, they pursued the Muslims far enough to become scattered, and Saladin took advantage by rallying his troops and charging at the Crusaders. The engagement ended in a decisive Ayyubid victory, and many high-ranking knights were captured. Saladin then moved to besiege the fortress, which fell on 30 August 1179.

In the spring of 1180, while Saladin was in the area of Safad

Safed (known in Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), is a city in the Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevat ...

, anxious to commence a vigorous campaign against the Kingdom of Jerusalem, King Baldwin sent messengers to him with proposals of peace. Because droughts and bad harvests hampered his commissariat

A commissariat is a department or organization commanded by a commissary or by a corps of commissaries.

In many countries, commissary is a police rank. In those countries, a commissariat is a police station commanded by a commissary.

In some ar ...

, Saladin agreed to a truce. Raymond of Tripoli denounced the truce but was compelled to accept after an Ayyubid raid on his territory in May and upon the appearance of Saladin's naval fleet off the port of Tartus

)

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, imagesize =

, image_caption = Tartus corniche Port of Tartus • Tartus beach and boulevard Cathedral of Our Lady of Tortosa • Al-Assad Stadium&n ...

.

Domestic affairs

In June 1180, Saladin hosted a reception for Nur al-Din Muhammad, theArtuqid

The Artuqid dynasty (alternatively Artukid, Ortoqid, or Ortokid; , pl. ; ; ) was a Turkoman dynasty originated from tribe that ruled in eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Iraq in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. The Artuq ...

''emir'' of Keyfa, at Geuk Su, in which he presented him and his brother Abu Bakr with gifts, valued at over 100,000 dinars according to Imad al-Din. This was intended to cement an alliance with the Artuqids and to impress other ''emirs'' in Mesopotamia and Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. Previously, Saladin offered to mediate relations between Nur al-Din and Kilij Arslan II

Kilij Arslan II ( 1ca, قِلِج اَرسلان دوم) or ʿIzz ad-Dīn Kilij Arslān ibn Masʿūd ( fa, عز الدین قلج ارسلان بن مسعود) (Modern Turkish ''Kılıç Arslan'', meaning "Sword Lion") was a Seljuk Sultan of Rûm ...

—the Seljuk sultan of Rûm—after the two came into conflict. The latter demanded that Nur al-Din return the lands given to him as a dowry for marrying his daughter when he received reports that she was being abused and used to gain Seljuk territory. Nur al-Din asked Saladin to mediate the issue, but Arslan refused.

After Nur al-Din and Saladin met at Geuk Su, the top Seljuk emir, Ikhtiyar al-Din al-Hasan, confirmed Arslan's submission, after which an agreement was drawn up. Saladin was later enraged when he received a message from Arslan accusing Nur al-Din of more abuses against his daughter. He threatened to attack the city of Malatya