Sugar Canes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall,

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall,

Sugarcane is a tropical, perennial grass that forms lateral shoots at the base to produce multiple stems, typically high and about in diameter. The stems grow into cane stalk, which when mature, constitutes around 75% of the entire plant. A mature stalk is typically composed of 11–16% fiber, 12–16% soluble sugars, 2–3% nonsugar carbohydrates, and 63–73% water. A sugarcane crop is sensitive to climate, soil type, irrigation, fertilizers, insects, disease control, varieties, and the harvest period. The average yield of cane stalk is per year, but this figure can vary between 30 and 180 tonnes per hectare depending on knowledge and crop management approach used in sugarcane cultivation. Sugarcane is a

Sugarcane is a tropical, perennial grass that forms lateral shoots at the base to produce multiple stems, typically high and about in diameter. The stems grow into cane stalk, which when mature, constitutes around 75% of the entire plant. A mature stalk is typically composed of 11–16% fiber, 12–16% soluble sugars, 2–3% nonsugar carbohydrates, and 63–73% water. A sugarcane crop is sensitive to climate, soil type, irrigation, fertilizers, insects, disease control, varieties, and the harvest period. The average yield of cane stalk is per year, but this figure can vary between 30 and 180 tonnes per hectare depending on knowledge and crop management approach used in sugarcane cultivation. Sugarcane is a

From Island Southeast Asia, ''S. officinarum'' was spread eastward into

From Island Southeast Asia, ''S. officinarum'' was spread eastward into  The passage of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act led to the abolition of slavery through most of the

The passage of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act led to the abolition of slavery through most of the  Between 1863 and 1900, merchants and plantation owners in

Between 1863 and 1900, merchants and plantation owners in

Sugarcane cultivation requires a tropical or

Sugarcane cultivation requires a tropical or

Sugarcane processing produces cane sugar (sucrose) from sugarcane. Other products of the processing include bagasse, molasses, and filtercake.

Sugarcane processing produces cane sugar (sucrose) from sugarcane. Other products of the processing include bagasse, molasses, and filtercake.

The primary use of bagasse and bagasse residue is as a fuel source for the boilers in the generation of process steam in sugar plants. Dried filtercake is used as an animal feed supplement, fertilizer, and source of

The primary use of bagasse and bagasse residue is as a fuel source for the boilers in the generation of process steam in sugar plants. Dried filtercake is used as an animal feed supplement, fertilizer, and source of

Ethanol is generally available as a byproduct of sugar production. It can be used as a biofuel alternative to gasoline, and is widely used in cars in Brazil. It is an alternative to gasoline, and may become the primary product of sugarcane processing, rather than sugar.

Ethanol is generally available as a byproduct of sugar production. It can be used as a biofuel alternative to gasoline, and is widely used in cars in Brazil. It is an alternative to gasoline, and may become the primary product of sugarcane processing, rather than sugar.

In Brazil, gasoline is required to contain at least 22% bioethanol. This bioethanol is sourced from Brazil's large sugarcane crop.

The production of ethanol from sugarcane is more energy efficient than from corn or sugar beets or palm/vegetable oils, particularly if cane bagasse is used to produce heat and power for the process. Furthermore, if biofuels are used for crop production and transport, the fossil energy input needed for each ethanol energy unit can be very low. EIA estimates that with an integrated sugar cane to ethanol technology, the well-to-wheels CO2 emissions can be 90% lower than conventional gasoline. A textbook on renewable energy describes the energy transformation:

In Brazil, gasoline is required to contain at least 22% bioethanol. This bioethanol is sourced from Brazil's large sugarcane crop.

The production of ethanol from sugarcane is more energy efficient than from corn or sugar beets or palm/vegetable oils, particularly if cane bagasse is used to produce heat and power for the process. Furthermore, if biofuels are used for crop production and transport, the fossil energy input needed for each ethanol energy unit can be very low. EIA estimates that with an integrated sugar cane to ethanol technology, the well-to-wheels CO2 emissions can be 90% lower than conventional gasoline. A textbook on renewable energy describes the energy transformation:

Sugarcane is a major crop in many countries. It is one of the plants with the highest bioconversion efficiency. Sugarcane crop is able to efficiently fix solar energy, yielding some 55 tonnes of dry matter per hectare of land annually. After harvest, the crop produces sugar juice and bagasse, the fibrous dry matter. This dry matter is biomass with potential as fuel for energy production. Bagasse can also be used as an alternative source of pulp for paper production.

Sugarcane bagasse is a potentially abundant source of energy for large producers of sugarcane, such as Brazil, India, and China. According to one report, with use of latest technologies, bagasse produced annually in Brazil has the potential of meeting 20% of Brazil's energy consumption by 2020.

Sugarcane is a major crop in many countries. It is one of the plants with the highest bioconversion efficiency. Sugarcane crop is able to efficiently fix solar energy, yielding some 55 tonnes of dry matter per hectare of land annually. After harvest, the crop produces sugar juice and bagasse, the fibrous dry matter. This dry matter is biomass with potential as fuel for energy production. Bagasse can also be used as an alternative source of pulp for paper production.

Sugarcane bagasse is a potentially abundant source of energy for large producers of sugarcane, such as Brazil, India, and China. According to one report, with use of latest technologies, bagasse produced annually in Brazil has the potential of meeting 20% of Brazil's energy consumption by 2020.

File:Sugarcane bsri 34.jpg, Sugarcane fields in

from oecd

{{Authority control * Sugar Crops originating from Asia Energy crops Ethanol fuel Flora of tropical Asia Articles containing video clips Crops Tropical agriculture Plant common names

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall,

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial

A perennial plant or simply perennial is a plant that lives more than two years. The term ('' per-'' + '' -ennial'', "through the years") is often used to differentiate a plant from shorter-lived annuals and biennials. The term is also wide ...

grass (in the genus ''Saccharum

''Saccharum'' is a genus of tall perennial plants of the broomsedge tribe within the grass family.

The genus is widespread across tropical, subtropical, and warm temperate regions in Africa, Eurasia, Australia, the Americas, and assorted ocean ...

'', tribe Andropogoneae

The Andropogoneae, sometimes called the sorghum tribe, are a large tribe of grasses (family Poaceae) with roughly 1,200 species in 90 genera, mainly distributed in tropical and subtropical areas. They include such important crops as maize (corn), ...

) that is used for sugar production

Production may refer to:

Economics and business

* Production (economics)

* Production, the act of manufacturing goods

* Production, in the outline of industrial organization, the act of making products (goods and services)

* Production as a stati ...

. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalks that are rich in sucrose

Sucrose, a disaccharide, is a sugar composed of glucose and fructose subunits. It is produced naturally in plants and is the main constituent of white sugar. It has the molecular formula .

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted and refined ...

, which accumulates in the stalk internodes. Sugarcanes belong to the grass family, Poaceae

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns an ...

, an economically important flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

family that includes maize, wheat, rice, and sorghum

''Sorghum'' () is a genus of about 25 species of flowering plants in the grass family (Poaceae). Some of these species are grown as cereals for human consumption and some in pastures for animals. One species is grown for grain, while many othe ...

, and many forage

Forage is a plant material (mainly plant leaves and stems) eaten by grazing livestock. Historically, the term ''forage'' has meant only plants eaten by the animals directly as pasture, crop residue, or immature cereal crops, but it is also used m ...

crops. It is native to the warm temperate and tropical regions of India, Southeast Asia, and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

. The plant is also grown for biofuel production, especially in Brazil, as the canes can be used directly to produce ethyl alcohol (ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl ...

).

Grown in tropical and subtropical regions, sugarcane is the world's largest crop by production quantity, totaling 1.9 billion tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the short ton ( United State ...

s in 2020, with Brazil accounting for 40% of the world total. Sugarcane accounts for 79% of sugar produced globally (most of the rest is made from sugar beet

A sugar beet is a plant whose root contains a high concentration of sucrose and which is grown commercially for sugar production. In plant breeding, it is known as the Altissima cultivar group of the common beet (''Beta vulgaris''). Together wi ...

s). About 70% of the sugar produced comes from ''Saccharum officinarum

''Saccharum officinarum'' is a large, strong-growing species of grass in the genus ''Saccharum''. Its stout stalks are rich in sucrose, a simple sugar which accumulates in the stalk internodes. It originated in New Guinea, and is now cultivated ...

'' and its hybrids. All sugarcane species can interbreed

In biology, a hybrid is the offspring resulting from combining the qualities of two organisms of different breeds, varieties, species or genera through sexual reproduction. Hybrids are not always intermediates between their parents (such as in ...

, and the major commercial cultivar

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture, ...

s are complex hybrids.

Sucrose (table sugar) is extracted from sugarcane in specialized mill factories. It is consumed directly in confectionery, used to sweeten beverages, as a preservative in jams and conserves, as a decorative finish for cakes and pâtisserie

A () is a type of Italian, French or Belgian bakery that specializes in pastries and sweets, as well as a term for such food items. In some countries, it is a legally controlled title that may only be used by bakeries that employ a licensed ...

, as a raw material in the food industry, or fermented to produce ethanol. Products derived from fermentation of sugar include falernum

Falernum (pronounced ) is either an 11% ABV syrup liqueur or a nonalcoholic syrup from the Caribbean. It is best known for its use in tropical drinks. It contains flavors of ginger, lime, and almond, and frequently cloves or allspice. It may ...

, rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is usually aged in oak barrels. Rum is produced in nearly every sugar-producing region of the world, such as the Phili ...

, and cachaça

''Cachaça'' () is a distilled spirit made from fermented sugarcane juice. Also known as ''pinga'', ''caninha'', and other names, it is the most popular spirit among distilled alcoholic beverages in Brazil.Cavalcante, Messias Soares. Todos os no ...

. In some regions, people use sugarcane reeds to make pens, mats, screens, and thatch. The young, unexpanded flower head

A pseudanthium (Greek for "false flower"; ) is an inflorescence that resembles a flower. The word is sometimes used for other structures that are neither a true flower nor a true inflorescence. Examples of pseudanthia include flower heads, compos ...

of ''Saccharum edule

''Saccharum edule'' is a species of sugarcane, that is a grass in the genus ''Saccharum'' with a fibrous stalk that is rich in sugar. It is cultivated in tropical climates in southeastern Asia. It has many common names which include duruka, tebu ...

'' (''duruka'') is eaten raw, steamed, or toasted, and prepared in various ways in Southeast Asia, such as certain island communities of Indonesia as well as in Oceanic

Oceanic may refer to:

*Of or relating to the ocean

*Of or relating to Oceania

**Oceanic climate

**Oceanic languages

**Oceanic person or people, also called "Pacific Islander(s)"

Places

* Oceanic, British Columbia, a settlement on Smith Island, ...

countries like Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

.

Sugarcane was an ancient crop of the Austronesian and Papuan people

The indigenous peoples of West Papua in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, commonly called Papuans, are Melanesians. There is genetic evidence for two major historical lineages in New Guinea and neighboring islands: a first wave from the Malay Arc ...

. It was introduced to Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

, Island Melanesia

Island Melanesia is a subregion of Melanesia in Oceania.

It is located east of New Guinea island, from the Bismarck Archipelago to New Caledonia.Steadman, 2006. ''Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds''

See also Archaeology a ...

, and Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

in prehistoric times via Austronesian sailors. It was also introduced to southern China and India by Austronesian traders around 1200 to 1000 BC. The Persians and Greeks encountered the famous "reeds that produce honey without bees" in India between the sixth and fourth centuries BC. They adopted and then spread sugarcane agriculture. Merchants began to trade in sugar, which was considered a luxurious and expensive spice, from India. In the 18th century, sugarcane plantations began in the Caribbean, South American, Indian Ocean, and Pacific island nations. The need for sugar crop laborers became a major driver of large migrations, some people voluntarily accepting indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

and others forcibly imported as slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

.

Etymology

The term "sugarcane" combines theSanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

word, शर्करा (''śárkarā'', later سُكَّر ''sukkar'' from Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

, and ''sucre'' from Middle French

Middle French (french: moyen français) is a historical division of the French language that covers the period from the 14th to the 16th century. It is a period of transition during which:

* the French language became clearly distinguished from t ...

and Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

) with "cane", a crop grown on plantations in the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

''gana'', Hindi for ''cane''. This term was first used by Spanish settlers in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

in the early 16th century.

Description

Sugarcane is a tropical, perennial grass that forms lateral shoots at the base to produce multiple stems, typically high and about in diameter. The stems grow into cane stalk, which when mature, constitutes around 75% of the entire plant. A mature stalk is typically composed of 11–16% fiber, 12–16% soluble sugars, 2–3% nonsugar carbohydrates, and 63–73% water. A sugarcane crop is sensitive to climate, soil type, irrigation, fertilizers, insects, disease control, varieties, and the harvest period. The average yield of cane stalk is per year, but this figure can vary between 30 and 180 tonnes per hectare depending on knowledge and crop management approach used in sugarcane cultivation. Sugarcane is a

Sugarcane is a tropical, perennial grass that forms lateral shoots at the base to produce multiple stems, typically high and about in diameter. The stems grow into cane stalk, which when mature, constitutes around 75% of the entire plant. A mature stalk is typically composed of 11–16% fiber, 12–16% soluble sugars, 2–3% nonsugar carbohydrates, and 63–73% water. A sugarcane crop is sensitive to climate, soil type, irrigation, fertilizers, insects, disease control, varieties, and the harvest period. The average yield of cane stalk is per year, but this figure can vary between 30 and 180 tonnes per hectare depending on knowledge and crop management approach used in sugarcane cultivation. Sugarcane is a cash crop

A cash crop or profit crop is an Agriculture, agricultural crop which is grown to sell for profit. It is typically purchased by parties separate from a farm. The term is used to differentiate marketed crops from staple crop (or "subsistence crop") ...

, but it is also used as livestock fodder. Sugarcane genome is one of the most complex plant genomes known, mostly due to interspecific hybridization and polyploidization.

History

The two centers of domestication for sugarcane are one for ''Saccharum officinarum

''Saccharum officinarum'' is a large, strong-growing species of grass in the genus ''Saccharum''. Its stout stalks are rich in sucrose, a simple sugar which accumulates in the stalk internodes. It originated in New Guinea, and is now cultivated ...

'' by Papuans

The indigenous peoples of West Papua in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, commonly called Papuans, are Melanesians. There is genetic evidence for two major historical lineages in New Guinea and neighboring islands: a first wave from the Malay Arch ...

in New Guinea and another for ''Saccharum sinense

''Saccharum sinense'' or ''Saccharum'' × ''sinense'', synonym ''Saccharum'' × ''barberi'', sugarcane, is strong-growing species of grass (Poaceae) in the genus ''Saccharum''. It is originally cultivated in Guangzhou, China where it is still c ...

'' by Austronesians in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

and southern China. Papuans and Austronesians originally primarily used sugarcane as food for domesticated pigs. The spread of both ''S. officinarum'' and ''S. sinense'' is closely linked to the migrations of the Austronesian peoples

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austro ...

. ''Saccharum barberi

''Saccharum sinense'' or ''Saccharum'' × ''sinense'', synonym ''Saccharum'' × ''barberi'', sugarcane, is strong-growing species of grass (Poaceae) in the genus ''Saccharum''. It is originally cultivated in Guangzhou, China where it is still c ...

'' was only cultivated in India after the introduction of ''S. officinarum''.

''S. officinarum'' was first domesticated in New Guinea and the islands east of the Wallace Line

The Wallace Line or Wallace's Line is a faunal boundary line drawn in 1859 by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace and named by English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley that separates the biogeographical realms of Asia and Wallacea, a tran ...

by Papuans, where it is the modern center of diversity. Beginning around 6,000 BP, several strains were selectively bred

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant mal ...

from the native ''Saccharum robustum

''Saccharum robustum'', the robust cane, is a species of plant found in New Guinea.

Ecology

''Eumetopina flavipes'', the island sugarcane planthopper, a species of planthopper present throughout South East Asia and is a vector for the Ramu stun ...

''. From New Guinea, it spread westwards to maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor. Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Sout ...

after contact with Austronesians, where it hybridized with ''Saccharum spontaneum

''Saccharum spontaneum'' (wild sugarcane, Kans grass) is a grass native to the Indian Subcontinent. It is a perennial grass, growing up to three meters in height, with spreading rhizomatous roots.

In the Terai-Duar savanna and grasslands, a l ...

''.

The second domestication center is mainland southern China and Taiwan, where ''S. sinense'' was a primary cultigen

A cultigen () or cultivated plant is a plant that has been deliberately altered or selected by humans; it is the result of artificial selection. These plants, for the most part, have commercial value in horticulture, agriculture or forestry. Beca ...

of the Austronesian peoples. Words for sugarcane are reconstructed as '' *təbuS'' or ''*CebuS'' in Proto-Austronesian

Proto-Austronesian (commonly abbreviated as PAN or PAn) is a proto-language. It is the reconstructed ancestor of the Austronesian languages, one of the world's major language families. Proto-Austronesian is assumed to have begun to diversify 3 ...

, which became ''*tebuh'' in Proto-Malayo-Polynesian

Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (PMP) is the reconstructed ancestor of the Malayo-Polynesian languages, which is by far the largest branch (by current speakers) of the Austronesian language family. Proto-Malayo-Polynesian is ancestral to all Austronesi ...

. It was one of the original major crops of the Austronesian peoples from at least 5,500 BP. Introduction of the sweeter ''S. officinarum'' may have gradually replaced it throughout its cultivated range in maritime Southeast Asia.

Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

and Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

by Austronesian voyagers as a canoe plant

One of the major human migration events was the maritime settlement of the islands of the Indo-Pacific by the Austronesian peoples, believed to have started from at least 5,500 to 4,000 BP (3500 to 2000 BCE). These migrations were accompanied ...

by around 3,500 BP. It was also spread westward and northward by around 3,000 BP to China and India by Austronesian traders, where it further hybridized with ''S. sinense'' and ''S. barberi''. From there, it spread further into western Eurasia and the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

.

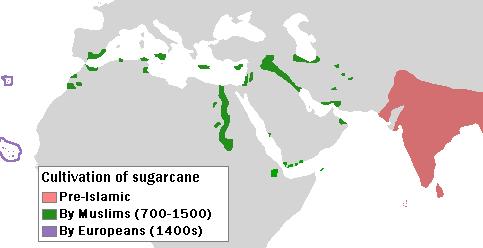

The earliest known production of crystalline sugar began in northern India. The earliest evidence of sugar production comes from ancient Sanskrit and Pali texts. Around the eighth century, Muslim and Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

traders introduced sugar from medieval India

Medieval India refers to a long period of Post-classical history of the Indian subcontinent between the "ancient period" and "modern period". It is usually regarded as running approximately from the breakup of the Gupta Empire in the 6th cent ...

to the other parts of the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

in the Mediterranean, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, North Africa, and Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

. By the 10th century, sources state that every village in Mesopotamia grew sugarcane.Watson, Andrew (1983). ''Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world''. Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by Henry VIII of England, King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press

A university press is an academic publishing hou ...

. pp. 26–27. It was among the early crops brought to the Americas by the Spanish, mainly Andalusians, from their fields in the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

, and the Portuguese from their fields in the Madeira Islands

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

. An article on sugarcane cultivation in Spain is included in Ibn al-'Awwam

Ibn al-'Awwam ( ar, ابن العوام), also called Abu Zakariya Ibn al-Awwam ( ar, أبو زكريا بن العوام), was a Muslim Arab agriculturist who flourished at Seville (modern-day southern Spain) in the later 12th century. He wrote a ...

's 12th-century ''Book on Agriculture''.

For thousands of years, cane was a heavy and unwieldy crop that had to be cut by hand and immediately ground to release the juice inside, lest it spoil within a day or two. Even before harvest time, rows had to be dug, stalks planted and plentiful wood chopped as fuel for boiling the liquid and reducing it to crystals and molasses. From the earliest traces of cane domestication on the Pacific island of New Guinea 10,000 years ago to its island-hopping advance to ancient India in 350 B.C., sugar was locally consumed and very labor-intensive. It remained little more than an exotic spice, medicinal glaze or sweetener for elite palates.

In colonial times, sugar formed one side of the triangle trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset t ...

of New World raw materials, along with European manufactured goods, and African slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

first brought sugarcane to the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

during his second voyage to the Americas, initially to the island of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

(modern day Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

and the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

). The first sugar harvest happened in Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La Española; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

in 1501; and many sugar mills had been constructed in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

and Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

by the 1520s. The Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

took sugar to Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

. By 1540, there were 800 cane sugar mill

A sugar cane mill is a factory that processes sugar cane to produce raw sugar, raw or white sugar.

The term is also used to refer to the equipment that crushes the sticks of sugar cane to extract the juice.

Processing

There are a number of st ...

s in Santa Catarina Island

Santa Catarina Island ( pt, Ilha de Santa Catarina) is an island in the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina, located off the southern coast.

It is home to the state capital, Florianópolis.

Location

Santa Catarina Island is approximately 54 km ...

and there were another 2,000 on the north coast of Brazil, Demarara

Demerara ( nl, Demerary, ) is a historical region in the Guianas, on the north coast of South America, now part of the country of Guyana. It was a colony of the Dutch West India Company between 1745 and 1792 and a colony of the Dutch state fro ...

, and Suriname

Suriname (; srn, Sranankondre or ), officially the Republic of Suriname ( nl, Republiek Suriname , srn, Ripolik fu Sranan), is a country on the northeastern Atlantic coast of South America. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north ...

.

Sugar, often in the form of molasses, was shipped from the Caribbean to Europe or New England, where it was used to make rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is usually aged in oak barrels. Rum is produced in nearly every sugar-producing region of the world, such as the Phili ...

. The profits from the sale of sugar were then used to purchase manufactured goods, which were then shipped to West Africa, where they were bartered for slaves. The slaves were then brought back to the Caribbean to be sold to sugar planters. The profits from the sale of the slaves were then used to buy more sugar, which was shipped to Europe. Toil in the sugar plantations became a main basis for a vast network of forced population movement, supplying people to work under brutal coercion.

France found its sugarcane islands so valuable that it effectively traded its portion of Canada, famously dismissed by Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

as "a few acres of snow

"A few acres of snow" (in the original French, "", , with "") is one of several quotations from Voltaire, an 18th-century writer. They are representative of his sneering evaluation of Canada as lacking economic value and strategic importance to ...

", to Britain for their return of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

, Martinique, and St. Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerin ...

at the end of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

. The Dutch similarly kept Suriname

Suriname (; srn, Sranankondre or ), officially the Republic of Suriname ( nl, Republiek Suriname , srn, Ripolik fu Sranan), is a country on the northeastern Atlantic coast of South America. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north ...

, a sugar colony in South America, instead of seeking the return of the New Netherlands

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva P ...

(New York).

Boiling house

A boilery or boiling house is a place of boiling, much as a bakery

A bakery is an establishment that produces and sells flour-based food baked in an oven such as bread, cookies, cakes, donuts, pastries, and pies. Some retail bakeries are a ...

s in the 17th through 19th centuries converted sugarcane juice

Sugarcane juice is the liquid extracted from pressed sugarcane. It is consumed as a beverage in many places, especially where sugarcane is commercially grown, such as Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, North Africa, and Latin America.

Sug ...

into raw sugar. These houses were attached to sugar plantations in the Western colonies. Slaves often ran the boiling process under very poor conditions. Rectangular boxes of brick or stone served as furnaces, with an opening at the bottom to stoke the fire and remove ashes. At the top of each furnace were up to seven copper kettles or boilers, each one smaller and hotter than the previous one. The cane juice began in the largest kettle. The juice was then heated and lime added to remove impurities. The juice was skimmed and then channeled to successively smaller kettles. The last kettle, the "teache", was where the cane juice became syrup. The next step was a cooling trough, where the sugar crystals hardened around a sticky core of molasses. This raw sugar was then shoveled from the cooling trough into hogshead

A hogshead (abbreviated "hhd", plural "hhds") is a large cask of liquid (or, less often, of a food commodity). More specifically, it refers to a specified volume, measured in either imperial or US customary measures, primarily applied to alcoho ...

s (wooden barrels), and from there into the curing house.

The passage of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act led to the abolition of slavery through most of the

The passage of the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act led to the abolition of slavery through most of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, and many of the emancipated slaves no longer worked on sugarcane plantations when they had a choice. West Indian planters, therefore, needed new workers, and they found cheap labour in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and India. The people were subject to indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

, a long-established form of contract, which bound them to unfree labour for a fixed term. The conditions where the indentured servants worked were frequently abysmal, owing to a lack of care among the planters. The first ships carrying indentured labourers from India left in 1836. The migrations to serve sugarcane plantations led to a significant number of ethnic Indians, Southeast Asians, and Chinese people settling in various parts of the world. In some islands and countries, the South Asian migrants now constitute between 10 and 50% of the population. Sugarcane plantations and Asian ethnic groups continue to thrive in countries such as Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

, Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies, which resides on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first European to encounter Guiana was S ...

, Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

, Martinique, French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic ...

, Guadeloupe, Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pe ...

, St. Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerin ...

, St. Vincent

Saint Vincent may refer to:

People Saints

* Vincent of Saragossa (died 304), a.k.a. Vincent the Deacon, deacon and martyr

* Saint Vincenca, 3rd century Roman martyress, whose relics are in Blato, Croatia

* Vincent, Orontius, and Victor (died 305) ...

, St. Kitts, St. Croix

Saint Croix; nl, Sint-Kruis; french: link=no, Sainte-Croix; Danish and no, Sankt Croix, Taino: ''Ay Ay'' ( ) is an island in the Caribbean Sea, and a county and constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), an unincor ...

, Suriname

Suriname (; srn, Sranankondre or ), officially the Republic of Suriname ( nl, Republiek Suriname , srn, Ripolik fu Sranan), is a country on the northeastern Atlantic coast of South America. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north ...

, Nevis

Nevis is a small island in the Caribbean Sea that forms part of the inner arc of the Leeward Islands chain of the West Indies. Nevis and the neighbouring island of Saint Kitts constitute one country: the Federation of Saint Kitts and Ne ...

, and Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

.

Between 1863 and 1900, merchants and plantation owners in

Between 1863 and 1900, merchants and plantation owners in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

and New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

(now part of the Commonwealth of Australia) brought between 55,000 and 62,500 people from the South Pacific Islands

Collectively called the Pacific Islands, the islands in the Pacific Ocean are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of se ...

to work on sugarcane plantations. An estimated one-third of these workers were coerced or kidnapped into slavery (known as blackbirding

Blackbirding involves the coercion of people through deception or kidnapping to work as slaves or poorly paid labourers in countries distant from their native land. The term has been most commonly applied to the large-scale taking of people in ...

). Many others were paid very low wages. Between 1904 and 1908, most of the 10,000 remaining workers were deported in an effort to keep Australia racially homogeneous and protect white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

workers from cheap foreign labour.

Cuban sugar derived from sugarcane was exported to the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, where it received price supports and was ensured a guaranteed market. The 1991 dissolution of the Soviet state forced the closure of most of Cuba's sugar industry.

Sugarcane remains an important part of the economy of Guyana

Guyana ( or ), officially the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern mainland of South America. Guyana is an indigenous word which means "Land of Many Waters". The capital city is Georgetown. Guyana is bordered by the ...

, Belize

Belize (; bzj, Bileez) is a Caribbean and Central American country on the northeastern coast of Central America. It is bordered by Mexico to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and Guatemala to the west and south. It also shares a wate ...

, Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

, and Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, along with the

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

, Guadeloupe, Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

, and other islands.

About 70% of the sugar produced globally comes from ''S. officinarum'' and hybrids using this species.

Cultivation

Sugarcane cultivation requires a tropical or

Sugarcane cultivation requires a tropical or subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical zone, geographical and Köppen climate classification, climate zones to the Northern Hemisphere, north and Southern Hemisphere, south of the tropics. Geographically part of the Geographical z ...

climate, with a minimum of of annual moisture. It is one of the most efficient photosynthesizers in the plant kingdom

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclude ...

. It is a C4 plant, able to convert up to 1% of incident solar energy into biomass. In primary growing regions across the tropics and subtropics

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical and climate zones to the north and south of the tropics. Geographically part of the temperate zones of both hemispheres, they cover the middle latitudes from to approximately 35° north and ...

, sugarcane crops can produce over 15 kg/m2 of cane. Once a major crop of the southeastern region of the United States, sugarcane cultivation declined there during the late 20th century, and is primarily confined to small plantations in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, and southeast Texas

Southeast Texas is a cultural and geographic region in the U.S. state of Texas, bordering Southwest Louisiana and its greater Acadiana region to the east. Being a part of East Texas, the region is geographically centered on the Greater Houston ...

in the 21st century. Sugarcane cultivation ceased in Hawaii when the last operating sugar plantation in the state shut down in 2016.

Sugarcane is cultivated in the tropics and subtropics in areas with a plentiful supply of water for a continuous period of more than 6–7 months each year, either from natural rainfall or through irrigation. The crop does not tolerate severe frosts. Therefore, most of the world's sugarcane is grown between 22°N and 22°S, and some up to 33°N and 33°S. When sugarcane crops are found outside this range, such as the Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ...

region of South Africa, it is normally due to anomalous climatic conditions in the region, such as warm ocean currents that sweep down the coast. In terms of altitude, sugarcane crops are found up to close to the equator in countries such as Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

, Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

, and Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

.

Sugarcane can be grown on many soils ranging from highly fertile, well-drained mollisol

Mollisol is a soil type which has deep, high organic matter, nutrient-enriched surface soil (a horizon), typically between 60 and 80 cm in depth. This fertile surface horizon, called a mollic epipedon, is the defining diagnostic feature of M ...

s, through heavy cracking vertisol

A vertisol, or vertosol, is a soil type in which there is a high content of expansive clay minerals, many of them known as montmorillonite, that form deep cracks in drier seasons or years. In a phenomenon known as argillipedoturbation, alternat ...

s, infertile acid oxisol

Oxisols are a soil order in USDA soil taxonomy, best known for their occurrence in tropical rain forest within 25 degrees north and south of the Equator. In the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB), they belong mainly to the ferralsols ...

s and ultisol

Ultisols, commonly known as red clay soils, are one of twelve soil orders in the United States Department of Agriculture soil taxonomy. The word "Ultisol" is derived from "ultimate", because Ultisols were seen as the ultimate product of continu ...

s, peaty histosol

In both the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB) and the USDA soil taxonomy, a Histosol is a soil consisting primarily of organic materials. They are defined as having or more of organic soil material in the upper . Organic soil materia ...

s, to rocky andisol

In USDA soil taxonomy

USDA soil taxonomy (ST) developed by the United States Department of Agriculture and the National Cooperative Soil Survey provides an elaborate classification of soil types according to several parameters (most commonly the ...

s. Both plentiful sunshine and water supplies increase cane production. This has made desert countries with good irrigation facilities such as Egypt some of the highest-yielding sugarcane-cultivating regions. Sugarcane consumes 9% of the world's potash

Potash () includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water-soluble form.

fertilizer production.

Although some sugarcanes produce seeds, modern stem cutting has become the most common reproduction method. Each cutting must contain at least one bud, and the cuttings are sometimes hand-planted. In more technologically advanced countries, such as the United States and Australia, billet planting

A billet is a living-quarters to which a soldier is assigned to sleep. Historically, a billet was a private dwelling that was required to accept the soldier.

Soldiers are generally billeted in barracks or garrisons when not on combat duty, al ...

is common. Billets (stalks or stalk sections) harvested by a mechanical harvester are planted by a machine that opens and recloses the ground. Once planted, a stand can be harvested several times; after each harvest, the cane sends up new stalks, called ratoons. Successive harvests give decreasing yields, eventually justifying replanting. Two to 10 harvests are usually made depending on the type of culture. In a country with a mechanical agriculture looking for a high production of large fields, as in North America, sugarcanes are replanted after two or three harvests to avoid a lowering yields. In countries with a more traditional type of agriculture with smaller fields and hand harvesting, as in the French island la Réunion

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figure ...

, sugarcane is often harvested up to 10 years before replanting.

Sugarcane is harvested by hand and mechanically. Hand harvesting accounts for more than half of production, and is dominant in the developing world. In hand harvesting, the field is first set on fire. The fire burns up dry leaves, and chases away or kills venomous snakes, without harming the stalks and roots. Harvesters then cut the cane just above ground-level using cane knives or machete

Older machete from Latin America

Gerber machete/saw combo

Agustín Cruz Tinoco of San Agustín de las Juntas, Oaxaca">San_Agustín_de_las_Juntas.html" ;"title="Agustín Cruz Tinoco of San Agustín de las Juntas">Agustín Cruz Tinoco of San ...

s. A skilled harvester can cut of sugarcane per hour.

Mechanical harvesting uses a combine, or sugarcane harvester

A sugarcane harvester is a large piece of agricultural machinery used to harvest and partially process sugarcane.

The machine, originally developed in the 1920s, remains similar in function and design to the combine harvester. Essentially a stora ...

. The Austoft 7000 series, the original modern harvester design, has now been copied by other companies, including Cameco / John Deere

Deere & Company, doing business as John Deere (), is an American corporation that manufactures agricultural machinery, heavy equipment, forestry machinery, diesel engines, drivetrains (axles, transmissions, gearboxes) used in heavy equipment, ...

. The machine cuts the cane at the base of the stalk, strips the leaves, chops the cane into consistent lengths and deposits it into a transporter following alongside. The harvester then blows the trash back onto the field. Such machines can harvest each hour, but harvested cane must be rapidly processed. Once cut, sugarcane begins to lose its sugar content, and damage to the cane during mechanical harvesting accelerates this decline. This decline is offset because a modern chopper harvester can complete the harvest faster and more efficiently than hand cutting and loading. Austoft also developed a series of hydraulic high-lift infield transporters to work alongside its harvesters to allow even more rapid transfer of cane to, for example, the nearest railway siding. This mechanical harvesting does not require the field to be set on fire; the residue left in the field by the machine consists of cane tops and dead leaves, which serve as mulch for the next planting.

Pests

Thecane beetle

''Dermolepida albohirtum'', the cane beetle, is a native Australian beetle and a parasite of sugarcane. Adult beetles eat the leaves of sugarcane, but greater damage is done by their larvae hatching underground and eating the roots, which eithe ...

(also known as cane grub) can substantially reduce crop yield by eating roots; it can be controlled with imidacloprid

Imidacloprid is a systemic insecticide belonging to a class of chemicals called the neonicotinoids which act on the central nervous system of insects. The chemical works by interfering with the transmission of stimuli in the insect nervous system. ...

(Confidor) or chlorpyrifos

Chlorpyrifos (CPS), also known as Chlorpyrifos ethyl, is an organophosphate pesticide that has been used on crops, animals, and buildings, and in other settings, to kill several pests, including insects and worms. It acts on the nervous systems ...

(Lorsban). Other important pests are the larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

e of some butterfly/moth species, including the turnip moth

''Agrotis segetum'', sometimes known as the turnip moth, is a moth of the family Noctuidae. The species was first described by Michael Denis and Ignaz Schiffermüller in 1775. It is a common European species and it is found in Africa and across ...

, the sugarcane borer

''Diatraea saccharalis'', the sugarcane borer, is a species of moth of the family Crambidae. It was described by Johan Christian Fabricius in 1794. It is native to the Caribbean, Central America, and the warmer parts of South America south to n ...

(''Diatraea saccharalis''), the African sugarcane borer (''Eldana saccharina''), the Mexican rice borer (''Eoreuma

''Eoreuma'' is a genus of moths of the family Crambidae

The Crambidae are the grass moth family of lepidopterans. They are variable in appearance, the nominal subfamily Crambinae (grass moths) taking up closely folded postures on grass stems w ...

loftini''), the African armyworm

The African armyworm (''Spodoptera exempta''), also called ''okalombo'', ''kommandowurm'', or nutgrass armyworm, is a species of moth of the family Noctuidae. The larvae often exhibit marching behavior when traveling to feeding sites, leading t ...

(''Spodoptera exempta''), leaf-cutting ants, termite

Termites are small insects that live in colonies and have distinct castes (eusocial) and feed on wood or other dead plant matter. Termites comprise the infraorder Isoptera, or alternatively the epifamily Termitoidae, within the order Blattode ...

s, spittlebug

The Aphrophoridae or spittlebugs are a family of insects belonging to the order Hemiptera. There are at least 160 genera and 990 described species in Aphrophoridae.

European genera

* ''Aphrophora'' Germar 1821

* ''Lepyronia'' Amyot & Serville ...

s (especially ''Mahanarva fimbriolata'' and ''Deois flavopicta''), and the beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

''Migdolus fryanus''. The planthopper

A planthopper is any insect in the infraorder Fulgoromorpha, in the suborder Auchenorrhyncha, a group exceeding 12,500 described species worldwide. The name comes from their remarkable resemblance to leaves and other plants of their environment ...

insect ''Eumetopina flavipes

''Eumetopina flavipes'', the island sugarcane planthopper, is a species of planthopper present throughout South East Asia. ''E. flavipes'' is a vector for Ramu stunt disease, a plant disease which affects sugarcane. Ramu stunt disease is widespre ...

'' acts as a virus vector, which causes the sugarcane disease ramu stunt

''Eumetopina flavipes'', the island sugarcane planthopper, is a species of planthopper present throughout South East Asia. ''E. flavipes'' is a vector for Ramu stunt disease, a plant disease which affects sugarcane. Ramu stunt disease is widespre ...

.

Pathogens

Numerous pathogens infect sugarcane, such as sugarcane grassy shoot disease caused by 'Candidatus Phytoplasma sacchari

''Candidatus'' Phytoplasma sacchari is a species of phytoplasma pathogen associated with sugarcane grassy shoot disease (SCGS). This SCGS phytoplasma belongs to the Rice Yellow Dwarf

Rice is the seed of the grass species ''Oryza sativa'' ...

', whiptail disease or sugarcane smut

Sugarcane smut is a fungal disease of sugarcane caused by the fungus ''Sporisorium scitamineum''. The disease is known as culmicolous, which describes the outgrowth of fungus of the stalk on the cane. It attacks several sugarcane species and has ...

, ''pokkah boeng'' caused by ''Fusarium moniliforme

''Fusarium verticillioides'' is the most commonly reported fungal species infecting maize (''Zea mays''). ''Fusarium verticillioides'' is the accepted name of the species, which was also known as ''Fusarium moniliforme''. The species has also bee ...

'', Xanthomonas axonopodis

''Xanthomonas'' (from greek: ''xanthos'' – “yellow”; ''monas'' – “entity”) is a genus of bacteria, many of which cause plant diseases. There are at least 27 plant associated ''Xanthomonas spp.'', that all together infect at least 400 ...

bacteria causes Gumming Disease, and red rot

Red rot is a degradation process found in vegetable-tanned leather.

Red rot is caused by prolonged storage or exposure to high relative humidity, environmental pollution, and high temperature. In particular, red rot occurs at pH values of 4.2 ...

disease caused by ''Colletotrichum falcatum

''Glomerella tucumanensis'' is a species of fungus

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These or ...

''. Viral diseases affecting sugarcane include sugarcane mosaic virus

''Sugarcane mosaic virus'' (SCMV) is a plant pathogenic virus of the family ''Potyviridae''. The virus was first noticed in Puerto Rico in 1916 and spread rapidly throughout the southern United States in the early 1920s. SCMV is of great concern ...

, maize streak virus

''Maize streak virus'' (MSV) is a virus primarily known for causing maize streak disease (MSD) in its major host, and which also infects over 80 wild and domesticated grasses. It is an insect-transmitted maize pathogen in the genus ''Mastrevirus ...

, and sugarcane yellow leaf virus.

Nitrogen fixation

Some sugarcane varieties are capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen in association with the bacterium ''Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus

''Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus'' is a bacterium with a rod-like shape, has circular ends, and can be classified as a Gram-negative bacterium. The bacterium is known for stimulating plant growth and being tolerant to acetic acid. With one to ...

''. Unlike legume

A legume () is a plant in the family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seed of such a plant. When used as a dry grain, the seed is also called a pulse. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consumption, for livestock f ...

s and other nitrogen-fixing plants that form root nodule

Root nodules are found on the roots of plants, primarily legumes, that form a symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Under nitrogen-limiting conditions, capable plants form a symbiotic relationship with a host-specific strain of bacteria known a ...

s in the soil in association with bacteria, ''G. diazotrophicus'' lives within the intercellular spaces of the sugarcane's stem. Coating seeds with the bacteria is a newly developed technology that can enable every crop species to fix nitrogen for its own use.

Conditions for sugarcane workers

At least 20,000 people are estimated to have died of chronic kidney disease in Central America in the past two decades – most of them sugarcane workers along the Pacific coast. This may be due to working long hours in the heat without adequate fluid intake. Not only are they dying because of exhaustion but some of the workers are being exposed to several hazards such as, high temperatures, harmful pesticides, and poisonous or venomous animals. This all occurs during the process of cutting the sugarcane manually, also causing physical ailments by doing the same movements for hours every work day.Processing

Traditionally, sugarcane processing requires two stages. Mills extract raw sugar from freshly harvested cane and "mill-white" sugar is sometimes produced immediately after the first stage at sugar-extraction mills, intended for local consumption. Sugar crystals appear naturally white in color during the crystallization process. Sulfur dioxide is added to inhibit the formation of color-inducing molecules and to stabilize the sugar juices during evaporation. Refineries, often located nearer to consumers in North America, Europe, and Japan, then produce refined white sugar, which is 99% sucrose. These two stages are slowly merging. Increasing affluence in the sugarcane-producing tropics increases demand for refined sugar products, driving a trend toward combined milling and refining.Milling

Bagasse

Bagasse ( ) is the dry pulpy fibrous material that remains after crushing sugarcane or sorghum stalks to extract their juice. It is used as a biofuel for the production of heat, energy, and electricity, and in the manufacture of pulp and building ...

, the residual dry fiber of the cane after cane juice has been extracted, is used for several purposes:

*fuel for the boilers and kilns

*production of paper, paperboard products, and reconstituted panelboard

*agricultural mulch

*as a raw material for production of chemicals

The primary use of bagasse and bagasse residue is as a fuel source for the boilers in the generation of process steam in sugar plants. Dried filtercake is used as an animal feed supplement, fertilizer, and source of

The primary use of bagasse and bagasse residue is as a fuel source for the boilers in the generation of process steam in sugar plants. Dried filtercake is used as an animal feed supplement, fertilizer, and source of sugarcane wax

Sugarcane wax is a wax extracted from sugarcane.

Production

The production of sugarcane wax is difficult and economically intensive. Sugarcane is used almost exclusively to produce sugar. More importantly, there is just about 0.1% of sugarcane ...

.

Molasses is produced in two forms: blackstrap, which has a characteristic strong flavor, and a purer molasses

Molasses () is a viscous substance resulting from refining sugarcane or sugar beets into sugar. Molasses varies in the amount of sugar, method of extraction and age of the plant. Sugarcane molasses is primarily used to sweeten and flavour foods ...

syrup. Blackstrap molasses is sold as a food and dietary supplement. It is also a common ingredient in animal feed, and is used to produce ethanol, rum, and citric acid

Citric acid is an organic compound with the chemical formula HOC(CO2H)(CH2CO2H)2. It is a colorless weak organic acid. It occurs naturally in citrus fruits. In biochemistry, it is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle, which occurs in t ...

. Purer molasses syrups are sold as molasses, and may also be blended with maple syrup

Maple syrup is a syrup made from the sap of maple trees. In cold climates, these trees store starch in their trunks and roots before winter; the starch is then converted to sugar that rises in the sap in late winter and early spring. Maple tree ...

, invert sugars, or corn syrup

Corn syrup is a food syrup which is made from the starch of corn (called maize in many countries) and contains varying amounts of sugars: glucose, maltose and higher oligosaccharides, depending on the grade. Corn syrup is used in foods to softe ...

. Both forms of molasses are used in baking.

Refining

Sugar refining

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

further purifies the raw sugar. It is first mixed with heavy syrup and then centrifuged in a process called "affination". Its purpose is to wash away the sugar crystals' outer coating, which is less pure than the crystal interior. The remaining sugar is then dissolved to make a syrup, about 60% solids by weight.

The sugar solution is clarified by the addition of phosphoric acid

Phosphoric acid (orthophosphoric acid, monophosphoric acid or phosphoric(V) acid) is a colorless, odorless phosphorus-containing solid, and inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is commonly encountered as an 85% aqueous solution, w ...

and calcium hydroxide

Calcium hydroxide (traditionally called slaked lime) is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula Ca( OH)2. It is a colorless crystal or white powder and is produced when quicklime (calcium oxide) is mixed or slaked with water. It has m ...

, which combine to precipitate calcium phosphate

The term calcium phosphate refers to a family of materials and minerals containing calcium ions (Ca2+) together with inorganic phosphate anions. Some so-called calcium phosphates contain oxide and hydroxide as well. Calcium phosphates are white ...

. The calcium phosphate particles entrap some impurities and absorb others, and then float to the top of the tank, where they can be skimmed off. An alternative to this "phosphatation" technique is "carbonatation

Carbonatation is a chemical reaction in which calcium hydroxide reacts with carbon dioxide and forms insoluble calcium carbonate:

:Ca(OH)2CO2->CaCO3H_2O

The process of forming a carbonate is sometimes referred to as "carbonation", although th ...

", which is similar, but uses carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

and calcium hydroxide to produce a calcium carbonate precipitate.

After filtering any remaining solids, the clarified syrup is decolorized by filtration through activated carbon

Activated carbon, also called activated charcoal, is a form of carbon commonly used to filter contaminants from water and air, among many other uses. It is processed (activated) to have small, low-volume pores that increase the surface area avail ...

. Bone char

Bone char ( lat, carbo animalis) is a porous, black, granular material produced by charring animal bones. Its composition varies depending on how it is made; however, it consists mainly of tricalcium phosphate (or hydroxyapatite) 57–80%, calci ...

or coal-based activated carbon is traditionally used in this role. Some remaining color-forming impurities are adsorb

Adsorption is the adhesion of atoms, ions or molecules from a gas, liquid or dissolved solid to a surface. This process creates a film of the ''adsorbate'' on the surface of the ''adsorbent''. This process differs from absorption, in which a fl ...

ed by the carbon. The purified syrup is then concentrated to supersaturation and repeatedly crystallized in a vacuum, to produce white refined sugar

White sugar, also called table sugar, granulated sugar, or regular sugar, is a commonly used type of sugar, made either of beet sugar or cane sugar, which has undergone a refining process.

Description

The refining process completely removes t ...

. As in a sugar mill, the sugar crystals are separated from the molasses by centrifuging. Additional sugar is recovered by blending the remaining syrup with the washings from affination and again crystallizing to produce brown sugar

Brown sugar is unrefined or partially refined soft sugar.

Brown Sugar may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Brown Sugar'' (1922 film), a 1922 British silent film directed by Fred Paul

* ''Brown Sugar'' (1931 film), a 1931 ...

. When no more sugar can be economically recovered, the final molasses still contains 20–30% sucrose and 15–25% glucose and fructose.

To produce granulated sugar

White sugar, also called table sugar, granulated sugar, or regular sugar, is a commonly used type of sugar, made either of beet sugar or cane sugar, which has undergone a refining process.