Steel Bridges In Canada on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Steel is an

Steel is an

There are many types of

There are many types of

When iron is

When iron is

Since the 17th century, the first step in European steel production has been the smelting of iron ore into

Since the 17th century, the first step in European steel production has been the smelting of iron ore into

The modern era in

The modern era in  These methods of steel production were rendered obsolete by the Linz-Donawitz process of

These methods of steel production were rendered obsolete by the Linz-Donawitz process of

The steel industry is often considered an indicator of economic progress, because of the critical role played by steel in infrastructural and overall economic development. In 1980, there were more than 500,000 U.S. steelworkers. By 2000, the number of steelworkers had fallen to 224,000.

The boom and bust, economic boom in China and India caused a massive increase in the demand for steel. Between 2000 and 2005, world steel demand increased by 6%. Since 2000, several Indian and Chinese steel firms have risen to prominence, such as Tata Steel (which bought Corus Group in 2007), Baosteel Group and Shagang Group. , though, ArcelorMittal is the world's List of steel producers, largest steel producer. In 2005, the British Geological Survey stated China was the top steel producer with about one-third of the world share; Japan, Russia, and the US followed respectively. The large production capacity of steel results also in a significant amount of carbon dioxide emissions inherent related to the main production route. In 2021, it was estimated that around 7% of the global greenhouse gas emissions resulted from the steel industry. Reduction of these emissions are expected to come from a shift in the main production route using cokes, more recycling of steel and the application of carbon capture and storage or carbon capture and utilization technology.

In 2008, steel began commodity market, trading as a commodity on the London Metal Exchange. At the end of 2008, the steel industry faced a sharp downturn that led to many cut-backs.

The steel industry is often considered an indicator of economic progress, because of the critical role played by steel in infrastructural and overall economic development. In 1980, there were more than 500,000 U.S. steelworkers. By 2000, the number of steelworkers had fallen to 224,000.

The boom and bust, economic boom in China and India caused a massive increase in the demand for steel. Between 2000 and 2005, world steel demand increased by 6%. Since 2000, several Indian and Chinese steel firms have risen to prominence, such as Tata Steel (which bought Corus Group in 2007), Baosteel Group and Shagang Group. , though, ArcelorMittal is the world's List of steel producers, largest steel producer. In 2005, the British Geological Survey stated China was the top steel producer with about one-third of the world share; Japan, Russia, and the US followed respectively. The large production capacity of steel results also in a significant amount of carbon dioxide emissions inherent related to the main production route. In 2021, it was estimated that around 7% of the global greenhouse gas emissions resulted from the steel industry. Reduction of these emissions are expected to come from a shift in the main production route using cokes, more recycling of steel and the application of carbon capture and storage or carbon capture and utilization technology.

In 2008, steel began commodity market, trading as a commodity on the London Metal Exchange. At the end of 2008, the steel industry faced a sharp downturn that led to many cut-backs.

Stainless steels contain a minimum of 11% chromium, often combined with nickel, to resist

Stainless steels contain a minimum of 11% chromium, often combined with nickel, to resist

Iron and steel are used widely in the construction of roads, railways, other infrastructure, appliances, and buildings. Most large modern structures, such as stadium#The modern stadium, stadiums and skyscrapers, bridges, and airports, are supported by a steel skeleton. Even those with a concrete structure employ steel for reinforcing. It sees widespread use in major appliances and automobile, cars. Despite the growth in usage of aluminium, steel is still the main material for car bodies. Steel is used in a variety of other construction materials, such as bolts, nail (engineering), nails and screws and other household products and cooking utensils.

Other common applications include shipbuilding, pipeline transport, pipelines, mining, offshore construction, aerospace, white goods (e.g. washing machines), heavy equipment such as bulldozers, office furniture, steel wool,

Iron and steel are used widely in the construction of roads, railways, other infrastructure, appliances, and buildings. Most large modern structures, such as stadium#The modern stadium, stadiums and skyscrapers, bridges, and airports, are supported by a steel skeleton. Even those with a concrete structure employ steel for reinforcing. It sees widespread use in major appliances and automobile, cars. Despite the growth in usage of aluminium, steel is still the main material for car bodies. Steel is used in a variety of other construction materials, such as bolts, nail (engineering), nails and screws and other household products and cooking utensils.

Other common applications include shipbuilding, pipeline transport, pipelines, mining, offshore construction, aerospace, white goods (e.g. washing machines), heavy equipment such as bulldozers, office furniture, steel wool,

Before the introduction of the

Before the introduction of the

* As reinforcing bars and mesh in reinforced concrete

* Railroad tracks

* Structural steel in modern buildings and bridges

* Wires

* Input to reforging applications

* As reinforcing bars and mesh in reinforced concrete

* Railroad tracks

* Structural steel in modern buildings and bridges

* Wires

* Input to reforging applications

* Cutlery

* Rulers

* Surgical instruments

* Watches

* Guns

* passenger car (rail), Rail passenger vehicles

* Tablet computer, Tablets

* Waste container, Trash Cans

* Body piercing jewellery

* Inexpensive Ring (jewellery), rings

* Components of spacecraft and space stations

* Cutlery

* Rulers

* Surgical instruments

* Watches

* Guns

* passenger car (rail), Rail passenger vehicles

* Tablet computer, Tablets

* Waste container, Trash Cans

* Body piercing jewellery

* Inexpensive Ring (jewellery), rings

* Components of spacecraft and space stations

Making Steel: Sparrows Point and the Rise and Ruin of American Industrial Might

'. University of Illinois Press, 2005. * Duncan Burn,

The Economic History of Steelmaking, 1867–1939: A Study in Competition

'. Cambridge University Press, 1961. * Harukiyu Hasegawa,

The Steel Industry in Japan: A Comparison with Britain

'. Routledge, 1996. * J.C. Carr and W. Taplin,

History of the British Steel Industry

'. Harvard University Press, 1962. * H. Lee Scamehorn,

Mill & Mine: The Cf&I in the Twentieth Century

'. University of Nebraska Press, 1992. * Warren, Kenneth,

Big Steel: The First Century of the United States Steel Corporation, 1901–2001

'. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001.

Official website

of the World Steel Association (worldsteel) *

steeluniversity.org

Online steel education resources, an initiative of World Steel Association

Metallurgy for the Non-Metallurgist

from the American Society for Metals

MATDAT Database of Properties of Unalloyed, Low-Alloy and High-Alloy Steels

– obtained from published results of material testing {{Authority control Steel, 2nd-millennium BC introductions Building materials Roofing materials

alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductility, ...

made up of iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in f ...

with added carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

to improve its strength

Strength may refer to:

Physical strength

*Physical strength, as in people or animals

* Hysterical strength, extreme strength occurring when people are in life-and-death situations

*Superhuman strength, great physical strength far above human c ...

and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engine ...

- and oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

-resistant typically need an additional 11% chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hardne ...

. Because of its high tensile strength

Ultimate tensile strength (UTS), often shortened to tensile strength (TS), ultimate strength, or F_\text within equations, is the maximum stress that a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before breaking. In brittle materials t ...

and low cost, steel is used in building

A building, or edifice, is an enclosed structure with a roof and walls standing more or less permanently in one place, such as a house or factory (although there's also portable buildings). Buildings come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and fun ...

s, infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and priv ...

, tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, only human beings, whose use of stone tools dates ba ...

s, ship

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished ...

s, train

In rail transport, a train (from Old French , from Latin , "to pull, to draw") is a series of connected vehicles that run along a railway track and Passenger train, transport people or Rail freight transport, freight. Trains are typically pul ...

s, cars, machine

A machine is a physical system using Power (physics), power to apply Force, forces and control Motion, movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to na ...

s, electrical appliances, weapons

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

, and rockets

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely ...

. Iron is the base metal

A base metal is a common and inexpensive metal, as opposed to a precious metal such as gold or silver. In numismatics, coins often derived their value from the precious metal content; however, base metals have also been used in coins in the past ...

of steel. Depending on the temperature, it can take two crystalline forms (allotropic forms): body-centred cubic and face-centred cubic. The interaction of the allotropes of iron

At atmospheric pressure, three allotropic forms of iron exist, depending on temperature: alpha iron (α-Fe), gamma iron (γ-Fe), and delta iron (δ-Fe). At very high pressure, a fourth form exists, called epsilon iron (ε-Fe). Some controvers ...

with the alloying elements, primarily carbon, gives steel and cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

their range of unique properties.

In pure iron, the crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in a crystal, crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of the constituent particles to form symmetric pat ...

has relatively little resistance to the iron atoms slipping past one another, and so pure iron is quite ductile

Ductility is a mechanical property commonly described as a material's amenability to drawing (e.g. into wire). In materials science, ductility is defined by the degree to which a material can sustain plastic deformation under tensile stres ...

, or soft and easily formed. In steel, small amounts of carbon, other elements, and inclusions within the iron act as hardening agents that prevent the movement of dislocation

In materials science, a dislocation or Taylor's dislocation is a linear crystallographic defect or irregularity within a crystal structure that contains an abrupt change in the arrangement of atoms. The movement of dislocations allow atoms to sl ...

s. The carbon in typical steel alloys may contribute up to 2.14% of its weight. Varying the amount of carbon and many other alloying elements, as well as controlling their chemical and physical makeup in the final steel (either as solute elements, or as precipitated phases), impedes the movement of the dislocations that make pure iron ductile, and thus controls and enhances its qualities. These qualities include the hardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to localized plastic deformation induced by either mechanical indentation or abrasion. In general, different materials differ in their hardness; for example hard ...

, quenching behaviour, need for annealing, tempering behaviour, yield strength

In materials science and engineering, the yield point is the point on a stress-strain curve that indicates the limit of elastic behavior and the beginning of plastic behavior. Below the yield point, a material will deform elastically and wi ...

, and tensile strength

Ultimate tensile strength (UTS), often shortened to tensile strength (TS), ultimate strength, or F_\text within equations, is the maximum stress that a material can withstand while being stretched or pulled before breaking. In brittle materials t ...

of the resulting steel. The increase in steel's strength compared to pure iron is possible only by reducing iron's ductility.

Steel was produced in bloomery

A bloomery is a type of metallurgical furnace once used widely for smelting iron from its oxides. The bloomery was the earliest form of smelter capable of smelting iron. Bloomeries produce a porous mass of iron and slag called a ''bloom ...

furnaces for thousands of years, but its large-scale, industrial use began only after more efficient production methods were devised in the 17th century, with the introduction of the blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

and production of crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fires ...

. This was followed by the open-hearth furnace

An open-hearth furnace or open hearth furnace is any of several kinds of industrial Industrial furnace, furnace in which excess carbon and other impurities are burnt out of pig iron to Steelmaking, produce steel. Because steel is difficult to ma ...

and then the Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is steelmaking, removal of impurities from the iron by ox ...

in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in the mid-19th century. With the invention of the Bessemer process, a new era of mass-produced

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and ba ...

steel began. Mild steel replaced wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

. The German states saw major steel prowess over Europe in the 19th century.

Further refinements in the process, such as basic oxygen steelmaking

Basic oxygen steelmaking (BOS, BOP, BOF, or OSM), also known as Linz-Donawitz steelmaking or the oxygen converter processBrock and Elzinga, p. 50. is a method of primary steelmaking in which carbon-rich molten pig iron is made into steel. Blowin ...

(BOS), largely replaced earlier methods by further lowering the cost of production and increasing the quality of the final product. Today, steel is one of the most commonly manufactured materials in the world, with more than 1.6 billion tons produced annually. Modern steel is generally identified by various grades defined by assorted standards organisations. The modern steel industry is one of the largest manufacturing industries in the world, but is one of the most energy and greenhouse gas emission

Greenhouse gas emissions from human activities strengthen the greenhouse effect, contributing to climate change. Most is carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels: coal, oil, and natural gas. The largest emitters include coal in China and ...

intense industries, contributing 8% of global emissions. However, steel is also very reusable: it is one of the world's most-recycled materials, with a recycling rate of over 60% globally.

Definitions and related materials

The noun ''steel'' originates from theProto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic (abbreviated PGmc; also called Common Germanic) is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Proto-Germanic eventually developed from pre-Proto-Germanic into three Germanic branc ...

adjective ''stahliją'' or ''stakhlijan'' 'made of steel', which is related to ''stahlaz'' or ''stahliją'' 'standing firm'.

The carbon content of steel is between 0.002% and 2.14% by weight for plain carbon steel (iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in f ...

-carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductility, ...

s). Too little carbon content leaves (pure) iron quite soft, ductile, and weak. Carbon contents higher than those of steel make a brittle alloy commonly called pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silic ...

. Alloy steel

Alloy steel is steel that is alloyed with a variety of elements in total amounts between 1.0% and 50% by weight to improve its mechanical properties. Alloy steels are broken down into two groups: low alloy steels and high alloy steels. The differe ...

is steel to which other alloying elements have been intentionally added to modify the characteristics of steel. Common alloying elements include: manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy use ...

, nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow to ...

, chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hardne ...

, molybdenum

Molybdenum is a chemical element with the symbol Mo and atomic number 42 which is located in period 5 and group 6. The name is from Neo-Latin ''molybdaenum'', which is based on Ancient Greek ', meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lea ...

, boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the ''boron group'' it has th ...

, titanium

Titanium is a chemical element with the symbol Ti and atomic number 22. Found in nature only as an oxide, it can be reduced to produce a lustrous transition metal with a silver color, low density, and high strength, resistant to corrosion in ...

, vanadium

Vanadium is a chemical element with the symbol V and atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery-grey, malleable transition metal. The elemental metal is rarely found in nature, but once isolated artificially, the formation of an oxide layer ( pas ...

, tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isolat ...

, cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, pr ...

, and niobium

Niobium is a chemical element with chemical symbol Nb (formerly columbium, Cb) and atomic number 41. It is a light grey, crystalline, and ductile transition metal. Pure niobium has a Mohs hardness rating similar to pure titanium, and it has sim ...

. Additional elements, most frequently considered undesirable, are also important in steel: phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

, sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

, silicon

Silicon is a chemical element with the symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. It is a member of group 14 in the periodic tab ...

, and traces of oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

, and copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

.

Plain carbon-iron alloys with a higher than 2.1% carbon content are known as cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content more than 2%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloy constituents affect its color when fractured: white cast iron has carbide impuriti ...

. With modern steelmaking

Steelmaking is the process of producing steel from iron ore and carbon/or scrap. In steelmaking, impurities such as nitrogen, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur and excess carbon (the most important impurity) are removed from the sourced iron, and all ...

techniques such as powder metal forming, it is possible to make very high-carbon (and other alloy material) steels, but such are not common. Cast iron is not malleable even when hot, but it can be formed by casting

Casting is a manufacturing process in which a liquid material is usually poured into a mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape, and then allowed to solidify. The solidified part is also known as a ''casting'', which is ejected ...

as it has a lower melting point

The melting point (or, rarely, liquefaction point) of a substance is the temperature at which it changes state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase exist in equilibrium. The melting point of a substance depends ...

than steel and good castability Castability is the ease of forming a quality casting. A very castable part design is easily developed, incurs minimal tooling costs, requires minimal energy, and has few rejections.Ravi, p. 2 Castability can refer to a part design or a material pro ...

properties. Certain compositions of cast iron, while retaining the economies of melting and casting, can be heat treated after casting to make malleable iron

Malleable iron is cast as white iron, the structure being a metastable carbide in a pearlitic matrix. Through an annealing heat treatment, the brittle structure as first cast is transformed into the malleable form. Carbon agglomerates into small ...

or ductile iron

Ductile iron, also known as ductile cast iron, nodular cast iron, spheroidal graphite iron, spheroidal graphite cast iron and SG iron, is a type of graphite-rich cast iron discovered in 1943 by Keith Millis. While most varieties of cast iron are ...

objects. Steel is distinguishable from wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.08%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4%). It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag Inclusion (mineral), inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which give it a ...

(now largely obsolete), which may contain a small amount of carbon but large amounts of slag

Slag is a by-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and used metals. Broadly, it can be classified as ferrous (by-products of processing iron and steel), ferroalloy (by-product of ferroalloy production) or non-ferrous/base metals (by-prod ...

.

Material properties

Origins and production

Iron is commonly found in the Earth's crust in the form of anore

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically containing metals, that can be mined, treated and sold at a profit.Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ore". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 Apr ...

, usually an iron oxide, such as magnetite

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With the ...

or hematite

Hematite (), also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide compound with the formula, Fe2O3 and is widely found in rocks and soils. Hematite crystals belong to the rhombohedral lattice system which is designated the alpha polymorph of . ...

. Iron is extracted from iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the fo ...

by removing the oxygen through its combination with a preferred chemical partner such as carbon which is then lost to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. This process, known as smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a ch ...

, was first applied to metals with lower melting

Melting, or fusion, is a physical process that results in the phase transition of a substance from a solid to a liquid. This occurs when the internal energy of the solid increases, typically by the application of heat or pressure, which inc ...

points, such as tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

, which melts at about , and copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

, which melts at about , and the combination, bronze, which has a melting point lower than . In comparison, cast iron melts at about . Small quantities of iron were smelted in ancient times, in the solid-state, by heating the ore in a charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, cal ...

fire and then welding

Welding is a fabrication (metal), fabrication process that joins materials, usually metals or thermoplastics, by using high heat to melt the parts together and allowing them to cool, causing Fusion welding, fusion. Welding is distinct from lower ...

the clumps together with a hammer and in the process squeezing out the impurities. With care, the carbon content could be controlled by moving it around in the fire. Unlike copper and tin, liquid or solid iron dissolves carbon quite readily.

All of these temperatures could be reached with ancient methods used since the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

. Since the oxidation rate of iron increases rapidly beyond , it is important that smelting take place in a low-oxygen environment. Smelting, using carbon to reduce iron oxides, results in an alloy (pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silic ...

) that retains too much carbon to be called steel. The excess carbon and other impurities are removed in a subsequent step.

Other materials are often added to the iron/carbon mixture to produce steel with the desired properties. Nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow to ...

and manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy use ...

in steel add to its tensile strength and make the austenite

Austenite, also known as gamma-phase iron (γ-Fe), is a metallic, non-magnetic allotrope of iron or a solid solution of iron with an alloying element. In plain-carbon steel, austenite exists above the critical eutectoid temperature of 1000 K ...

form of the iron-carbon solution more stable, chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hardne ...

increases hardness and melting temperature, and vanadium

Vanadium is a chemical element with the symbol V and atomic number 23. It is a hard, silvery-grey, malleable transition metal. The elemental metal is rarely found in nature, but once isolated artificially, the formation of an oxide layer ( pas ...

also increases hardness while making it less prone to metal fatigue

In materials science, fatigue is the initiation and propagation of cracks in a material due to cyclic loading. Once a fatigue crack has initiated, it grows a small amount with each loading cycle, typically producing striations on some parts o ...

.

To inhibit corrosion, at least 11% chromium can be added to steel so that a hard oxide

An oxide () is a chemical compound that contains at least one oxygen atom and one other element in its chemical formula. "Oxide" itself is the dianion of oxygen, an O2– (molecular) ion. with oxygen in the oxidation state of −2. Most of the E ...

forms on the metal surface; this is known as stainless steel

Stainless steel is an alloy of iron that is resistant to rusting and corrosion. It contains at least 11% chromium and may contain elements such as carbon, other nonmetals and metals to obtain other desired properties. Stainless steel's corros ...

. Tungsten slows the formation of cementite

Cementite (or iron carbide) is a compound of iron and carbon, more precisely an intermediate transition metal carbide with the formula Fe3C. By weight, it is 6.67% carbon and 93.3% iron. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It is a hard, bri ...

, keeping carbon in the iron matrix and allowing martensite

Martensite is a very hard form of steel crystalline structure. It is named after German metallurgist Adolf Martens. By analogy the term can also refer to any crystal structure that is formed by diffusionless transformation.

Properties

M ...

to preferentially form at slower quench rates, resulting in high-speed steel

High-speed steel (HSS or HS) is a subset of tool steels, commonly used as cutting tool material.

It is often used in power-saw blades and drill bits. It is superior to the older high-carbon steel tools used extensively through the 1940s in tha ...

. The addition of lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

and sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

decrease grain size, thereby making the steel easier to turn, but also more brittle and prone to corrosion. Such alloys are nevertheless frequently used for components such as nuts, bolts, and washers in applications where toughness and corrosion resistance are not paramount. For the most part, however, p-block

A block of the periodic table is a set of elements unified by the atomic orbitals their valence electrons or vacancies lie in. The term appears to have been first used by Charles Janet. Each block is named after its characteristic orbital: s-blo ...

elements such as sulfur, nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

, phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

, and lead are considered contaminants that make steel more brittle and are therefore removed from the steel melt during processing.

Properties

Thedensity

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematical ...

of steel varies based on the alloying constituents but usually ranges between , or .

Even in a narrow range of concentrations of mixtures of carbon and iron that make steel, several different metallurgical structures, with very different properties can form. Understanding such properties is essential to making quality steel. At room temperature

Colloquially, "room temperature" is a range of air temperatures that most people prefer for indoor settings. It feels comfortable to a person when they are wearing typical indoor clothing. Human comfort can extend beyond this range depending on ...

, the most stable form of pure iron is the body-centred cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties of ...

(BCC) structure called alpha iron or α-iron. It is a fairly soft metal that can dissolve only a small concentration of carbon, no more than 0.005% at and 0.021 wt% at . The inclusion of carbon in alpha iron is called ferrite. At 910 °C, pure iron transforms into a face-centred cubic

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties of ...

(FCC) structure, called gamma iron or γ-iron. The inclusion of carbon in gamma iron is called austenite. The more open FCC structure of austenite can dissolve considerably more carbon, as much as 2.1%, (38 times that of ferrite) carbon at , which reflects the upper carbon content of steel, beyond which is cast iron. When carbon moves out of solution with iron, it forms a very hard, but brittle material called cementite (Fe3C).

When steels with exactly 0.8% carbon (known as a eutectoid steel), are cooled, the austenitic

Austenite, also known as gamma-phase iron (γ-Fe), is a metallic, non-magnetic allotrope of iron or a solid solution of iron with an alloying element. In plain-carbon steel, austenite exists above the critical eutectoid temperature of 1000 ...

phase (FCC) of the mixture attempts to revert to the ferrite phase (BCC). The carbon no longer fits within the FCC austenite structure, resulting in an excess of carbon. One way for carbon to leave the austenite is for it to precipitate

In an aqueous solution, precipitation is the process of transforming a dissolved substance into an insoluble solid from a super-saturated solution. The solid formed is called the precipitate. In case of an inorganic chemical reaction leading ...

out of solution as cementite

Cementite (or iron carbide) is a compound of iron and carbon, more precisely an intermediate transition metal carbide with the formula Fe3C. By weight, it is 6.67% carbon and 93.3% iron. It has an orthorhombic crystal structure. It is a hard, bri ...

, leaving behind a surrounding phase of BCC iron called ferrite with a small percentage of carbon in solution. The two, ferrite and cementite, precipitate simultaneously producing a layered structure called pearlite

Pearlite is a two-phased, lamellar (or layered) structure composed of alternating layers of ferrite (87.5 wt%) and cementite (12.5 wt%) that occurs in some steels and cast irons. During slow cooling of an iron-carbon alloy, pearlite forms ...

, named for its resemblance to mother of pearl

Nacre ( , ), also known as mother of pearl, is an organicinorganic composite material produced by some molluscs as an inner shell layer; it is also the material of which pearls are composed. It is strong, resilient, and iridescent.

Nacre is ...

. In a hypereutectoid composition (greater than 0.8% carbon), the carbon will first precipitate out as large inclusions of cementite at the austenite grain boundaries

In materials science, a grain boundary is the interface between two grains, or crystallites, in a polycrystalline material. Grain boundaries are two-dimensional defects in the crystal structure, and tend to decrease the electrical and thermal ...

until the percentage of carbon in the grains

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit (caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legumes ...

has decreased to the eutectoid composition (0.8% carbon), at which point the pearlite structure forms. For steels that have less than 0.8% carbon (hypoeutectoid), ferrite will first form within the grains until the remaining composition rises to 0.8% of carbon, at which point the pearlite structure will form. No large inclusions of cementite will form at the boundaries in hypoeuctoid steel. The above assumes that the cooling process is very slow, allowing enough time for the carbon to migrate.

As the rate of cooling is increased the carbon will have less time to migrate to form carbide at the grain boundaries but will have increasingly large amounts of pearlite of a finer and finer structure within the grains; hence the carbide is more widely dispersed and acts to prevent slip of defects within those grains, resulting in hardening of the steel. At the very high cooling rates produced by quenching, the carbon has no time to migrate but is locked within the face-centred austenite and forms martensite

Martensite is a very hard form of steel crystalline structure. It is named after German metallurgist Adolf Martens. By analogy the term can also refer to any crystal structure that is formed by diffusionless transformation.

Properties

M ...

. Martensite is a highly strained and stressed, supersaturated form of carbon and iron and is exceedingly hard but brittle. Depending on the carbon content, the martensitic phase takes different forms. Below 0.2% carbon, it takes on a ferrite BCC crystal form, but at higher carbon content it takes a body-centred tetragonal

In crystallography, the tetragonal crystal system is one of the 7 crystal systems. Tetragonal crystal lattices result from stretching a cubic lattice along one of its lattice vectors, so that the cube becomes a rectangular prism with a squa ...

(BCT) structure. There is no thermal activation energy

In chemistry and physics, activation energy is the minimum amount of energy that must be provided for compounds to result in a chemical reaction. The activation energy (''E''a) of a reaction is measured in joules per mole (J/mol), kilojoules pe ...

for the transformation from austenite to martensite. There is no compositional change so the atoms generally retain their same neighbors..

Martensite has a lower density (it expands during the cooling) than does austenite, so that the transformation between them results in a change of volume. In this case, expansion occurs. Internal stresses from this expansion generally take the form of compression

Compression may refer to:

Physical science

*Compression (physics), size reduction due to forces

*Compression member, a structural element such as a column

*Compressibility, susceptibility to compression

* Gas compression

*Compression ratio, of a ...

on the crystals of martensite and tension

Tension may refer to:

Science

* Psychological stress

* Tension (physics), a force related to the stretching of an object (the opposite of compression)

* Tension (geology), a stress which stretches rocks in two opposite directions

* Voltage or el ...

on the remaining ferrite, with a fair amount of shear

Shear may refer to:

Textile production

*Animal shearing, the collection of wool from various species

**Sheep shearing

*The removal of nap during wool cloth production

Science and technology Engineering

*Shear strength (soil), the shear strength ...

on both constituents. If quenching is done improperly, the internal stresses can cause a part to shatter as it cools. At the very least, they cause internal work hardening

In materials science, work hardening, also known as strain hardening, is the strengthening of a metal or polymer by plastic deformation. Work hardening may be desirable, undesirable, or inconsequential, depending on the context.

This strengt ...

and other microscopic imperfections. It is common for quench cracks to form when steel is water quenched, although they may not always be visible.

Heat treatment

There are many types of

There are many types of heat treating

Heat treating (or heat treatment) is a group of industrial, thermal and metalworking processes used to alter the physical, and sometimes chemical, properties of a material. The most common application is metallurgical. Heat treatments are also ...

processes available to steel. The most common are annealing, quenching

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece in water, oil, polymer, air, or other fluids to obtain certain material properties. A type of heat treating, quenching prevents undesired low-temperature processes, such as pha ...

, and tempering.

Annealing is the process of heating the steel to a sufficiently high temperature to relieve local internal stresses. It does not create a general softening of the product but only locally relieves strains and stresses locked up within the material. Annealing goes through three phases: recovery

Recovery or Recover may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Books

* ''Recovery'' (novel), a Star Wars e-book

* Recovery Version, a translation of the Bible with footnotes published by Living Stream Ministry

Film and television

* ''Recovery'' (fil ...

, recrystallization, and grain growth

In materials science, grain growth is the increase in size of grains (crystallites) in a material at high temperature. This occurs when recovery and recrystallisation are complete and further reduction in the internal energy can only be achieved ...

. The temperature required to anneal a particular steel depends on the type of annealing to be achieved and the alloying constituents.

Quenching involves heating the steel to create the austenite phase then quenching it in water or oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

. This rapid cooling results in a hard but brittle martensitic structure. The steel is then tempered, which is just a specialized type of annealing, to reduce brittleness. In this application the annealing (tempering) process transforms some of the martensite into cementite, or spheroidite

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, coba ...

and hence it reduces the internal stresses and defects. The result is a more ductile and fracture-resistant steel.

Production

When iron is

When iron is smelted

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a c ...

from its ore, it contains more carbon than is desirable. To become steel, it must be reprocessed to reduce the carbon to the correct amount, at which point other elements can be added. In the past, steel facilities would cast

Cast may refer to:

Music

* Cast (band), an English alternative rock band

* Cast (Mexican band), a progressive Mexican rock band

* The Cast, a Scottish musical duo: Mairi Campbell and Dave Francis

* ''Cast'', a 2012 album by Trespassers William

* ...

the raw steel product into ingot

An ingot is a piece of relatively pure material, usually metal, that is cast into a shape suitable for further processing. In steelmaking, it is the first step among semi-finished casting products. Ingots usually require a second procedure of sha ...

s which would be stored until use in further refinement processes that resulted in the finished product. In modern facilities, the initial product is close to the final composition and is continuously cast into long slabs, cut and shaped into bars and extrusions and heat treated to produce a final product. Today, approximately 96% of steel is continuously cast, while only 4% is produced as ingots.

The ingots are then heated in a soaking pit and hot rolled

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simil ...

into slabs, billets

A billet is a living-quarters to which a soldier is assigned to sleep. Historically, a billet was a private dwelling that was required to accept the soldier.

Soldiers are generally billeted in barracks or garrisons when not on combat duty, al ...

, or blooms. Slabs are hot or cold rolled

In metalworking, rolling is a metal forming process in which metal stock is passed through one or more pairs of rolls to reduce the thickness, to make the thickness uniform, and/or to impart a desired mechanical property. The concept is simil ...

into sheet metal

Sheet metal is metal formed into thin, flat pieces, usually by an industrial process. Sheet metal is one of the fundamental forms used in metalworking, and it can be cut and bent into a variety of shapes.

Thicknesses can vary significantly; ex ...

or plates. Billets are hot or cold rolled into bars, rods, and wire. Blooms are hot or cold rolled into structural steel

Structural steel is a category of steel used for making construction materials in a variety of shapes. Many structural steel shapes take the form of an elongated beam having a profile of a specific cross section. Structural steel shapes, sizes, ...

, such as I-beam

An I-beam, also known as H-beam (for universal column, UC), w-beam (for "wide flange"), universal beam (UB), rolled steel joist (RSJ), or double-T (especially in Polish language, Polish, Bulgarian language, Bulgarian, Spanish language, Spanish ...

s and rails

Rail or rails may refer to:

Rail transport

*Rail transport and related matters

*Rail (rail transport) or railway lines, the running surface of a railway

Arts and media Film

* ''Rails'' (film), a 1929 Italian film by Mario Camerini

* ''Rail'' ( ...

. In modern steel mills these processes often occur in one assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process (often called a ''progressive assembly'') in which parts (usually interchangeable parts) are added as the semi-finished assembly moves from workstation to workstation where the parts are added in seq ...

, with ore coming in and finished steel products coming out. Sometimes after a steel's final rolling, it is heat treated for strength; however, this is relatively rare.

History

Ancient

Steel was known in antiquity and was produced in bloomeries andcrucible

A crucible is a ceramic or metal container in which metals or other substances may be melted or subjected to very high temperatures. While crucibles were historically usually made from clay, they can be made from any material that withstands te ...

s.

The earliest known production of steel is seen in pieces of ironware excavated from an archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (either prehistoric or historic or contemporary), and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline of archaeology an ...

in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

(Kaman-Kalehöyük

Kaman-Kalehöyük is a multi-period archaeological site in Kırşehir Province, Turkey, around 100 km south east of Ankara, 6 km east of the town center of Kaman. It is a tell or mound site that was occupied during the Bronze Age, Iron ...

) and are nearly 4,000 years old, dating from 1800 BC. Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

identifies steel weapons such as the ''falcata

The falcata is a type of sword typical of pre-Roman Iberia. The falcata was used to great effect for warfare in the ancient Iberian peninsula, and is firmly associated with the southern Iberian tribes, among other ancient peoples of Hispania. ...

'' in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, while Noric steel

Noric steel was a steel from Noricum, a Celtic kingdom located in modern Austria and Slovenia.

The proverbial hardness of Noric steel is expressed by Ovid: ''"...durior ..ferro quod noricus excoquit ignis..."'' which roughly translates to "...har ...

was used by the Roman military

The military of ancient Rome, according to Titus Livius, one of the more illustrious historians of Rome over the centuries, was a key element in the rise of Rome over "above seven hundred years" from a small settlement in Latium to the capital o ...

.

The reputation of ''Seric iron'' of India (wootz steel) grew considerably in the rest of the world. Metal production sites in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

employed wind furnaces driven by the monsoon winds, capable of producing high-carbon steel. Large-scale Wootz steel

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon ...

production in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

using crucibles occurred by the sixth century BC, the pioneering precursor to modern steel production and metallurgy.

The Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

of the Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in History of China#Ancient China, ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded ...

(403–221 BC) had quench-hardened steel, while Chinese of the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–207 BC) and a warr ...

(202 BC—AD 220) created steel by melting together wrought iron with cast iron, thus producing a carbon-intermediate steel by the 1st century AD.Gernet, Jacques (1982). ''A History of Chinese Civilization''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 69. .

There is evidence that carbon steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobalt ...

was made in Western Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

by the ancestors of the Haya people

The Haya (or Bahaya) are a Bantu ethnic group based in Kagera Region, northwestern Tanzania, on the western side of Lake Victoria. With over one million people, it is estimated the Haya make up approximately 2% of the population of Tanzania. Hi ...

as early as 2,000 years ago by a complex process of "pre-heating" allowing temperatures inside a furnace to reach 1300 to 1400 °C.

Wootz and Damascus

Evidence of the earliest production of high carbon steel inIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

are found in Kodumanal in Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a States and union territories of India, state in southern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of India ...

, the Golconda

Fort (Telugu: గోల్కొండ, romanized: ''Gōlkōnḍa'') is a historic fortress and ruined city located in Hyderabad, Telangana, India. It was originally called Mankal. The fort was originally built by Kakatiya ruler Pratāparu ...

area in Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh (, abbr. AP) is a state in the south-eastern coastal region of India. It is the seventh-largest state by area covering an area of and tenth-most populous state with 49,386,799 inhabitants. It is bordered by Telangana to the ...

and Karnataka

Karnataka (; ISO: , , also known as Karunāḍu) is a state in the southwestern region of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act. Originally known as Mysore State , it was renamed ''Karnat ...

, and in the Samanalawewa

The Samanala Dam ( Sinhala: සමනලවැව වේල්ල) is a dam primarily used for hydroelectric power generation in Sri Lanka. Commissioned in 1992, the Samanalawewa Project (''Samanala Reservoir Project'') is the third-largest hydro ...

, Dehigaha Alakanda, areas of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

. This came to be known as Wootz steel

Wootz steel, also known as Seric steel, is a crucible steel characterized by a pattern of bands and high carbon content. These bands are formed by sheets of microscopic carbides within a tempered martensite or pearlite matrix in higher carbon ...

, produced in South India by about the sixth century BC and exported globally. The steel technology existed prior to 326 BC in the region as they are mentioned in literature of Sangam Tamil, Arabic, and Latin as the finest steel in the world exported to the Romans, Egyptian, Chinese and Arab worlds at that time – what they called ''Seric Iron''. A 200 BC Tamil trade guild in Tissamaharama, in the South East of Sri Lanka, brought with them some of the oldest iron and steel artifacts and production processes to the island from the classical period. The Chinese and locals in Anuradhapura

Anuradhapura ( si, අනුරාධපුරය, translit=Anurādhapuraya; ta, அனுராதபுரம், translit=Aṉurātapuram) is a major city located in north central plain of Sri Lanka. It is the capital city of North Central ...

, Sri Lanka had also adopted the production methods of creating Wootz steel from the Chera Dynasty Tamils of South India by the 5th century AD. In Sri Lanka, this early steel-making method employed a unique wind furnace, driven by the monsoon winds, capable of producing high-carbon steel.Coghlan, Herbert Henery. (1977). ''Notes on prehistoric and early iron in the Old World''. Oxprint. pp. 99–100 Since the technology was acquired from the Tamilians

The Tamil people, also known as Tamilar ( ta, தமிழர், Tamiḻar, translit-std=ISO, in the singular or ta, தமிழர்கள், Tamiḻarkaḷ, translit-std=ISO, label=none, in the plural), or simply Tamils (), are a Drav ...

from South India, the origin of steel technology in India can be conservatively estimated at 400–500 BC.

The manufacture of what came to be called Wootz, or Damascus steel

Damascus steel was the forged steel of the blades of swords smithed in the Near East from ingots of Wootz steel either imported from Southern India or made in production centres in Sri Lanka, or Khorasan, Iran. These swords are characterized by ...

, famous for its durability and ability to hold an edge, may have been taken by the Arabs from Persia, who took it from India. It was originally created from several different materials including various trace element

__NOTOC__

A trace element, also called minor element, is a chemical element whose concentration (or other measure of amount) is very low (a "trace amount"). They are classified into two groups: essential and non-essential. Essential trace elements ...

s, apparently ultimately from the writings of Zosimos of Panopolis

Zosimos of Panopolis ( el, Ζώσιμος ὁ Πανοπολίτης; also known by the Latin name Zosimus Alchemista, i.e. "Zosimus the Alchemist") was a Greco-Egyptian alchemist and Gnostic mystic who lived at the end of the 3rd and beginning ...

. In 327 BC, Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

was rewarded by the defeated King Porus

Porus or Poros ( grc, Πῶρος ; 326–321 BC) was an ancient Indian king whose territory spanned the region between the Jhelum River (Hydaspes) and Chenab River (Acesines), in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent. He is only ment ...

, not with gold or silver but with 30 pounds of steel. A recent study has speculated that carbon nanotubes

A scanning tunneling microscopy image of a single-walled carbon nanotube

Rotating single-walled zigzag carbon nanotube

A carbon nanotube (CNT) is a tube made of carbon with diameters typically measured in nanometers.

''Single-wall carbon nan ...

were included in its structure, which might explain some of its legendary qualities, though, given the technology of that time, such qualities were produced by chance rather than by design. Natural wind was used where the soil containing iron was heated by the use of wood. The ancient Sinhalese

Sinhalese people ( si, සිංහල ජනතාව, Sinhala Janathāva) are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group native to the island of Sri Lanka. They were historically known as Hela people ( si, හෙළ). They constitute about 75% of ...

managed to extract a ton of steel for every 2 tons of soil, a remarkable feat at the time. One such furnace was found in Samanalawewa and archaeologists were able to produce steel as the ancients did.

Crucible steel

Crucible steel is steel made by melting pig iron (cast iron), iron, and sometimes steel, often along with sand, glass, ashes, and other fluxes, in a crucible. In ancient times steel and iron were impossible to melt using charcoal or coal fires ...

, formed by slowly heating and cooling pure iron and carbon (typically in the form of charcoal) in a crucible, was produced in Merv

Merv ( tk, Merw, ', مرو; fa, مرو, ''Marv''), also known as the Merve Oasis, formerly known as Alexandria ( grc-gre, Ἀλεξάνδρεια), Antiochia in Margiana ( grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐν τῇ Μαργιανῇ) and ...

by the 9th to 10th century AD. In the 11th century, there is evidence of the production of steel in Song China

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

using two techniques: a "berganesque" method that produced inferior, inhomogeneous steel, and a precursor to the modern Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is steelmaking, removal of impurities from the iron by ox ...

that used partial decarbonization

Climate change mitigation is action to limit climate change by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases or removing those gases from the atmosphere. The recent rise in global average temperature is mostly caused by emissions from fossil fuels b ...

via repeated forging under a cold blast

Cold blast, in ironmaking, refers to a metallurgical furnace where air is not preheated before being blown into the furnace. This represents the earliest stage in the development of ironmaking. Until the 1820s, the use of cold air was thought to b ...

.

Modern

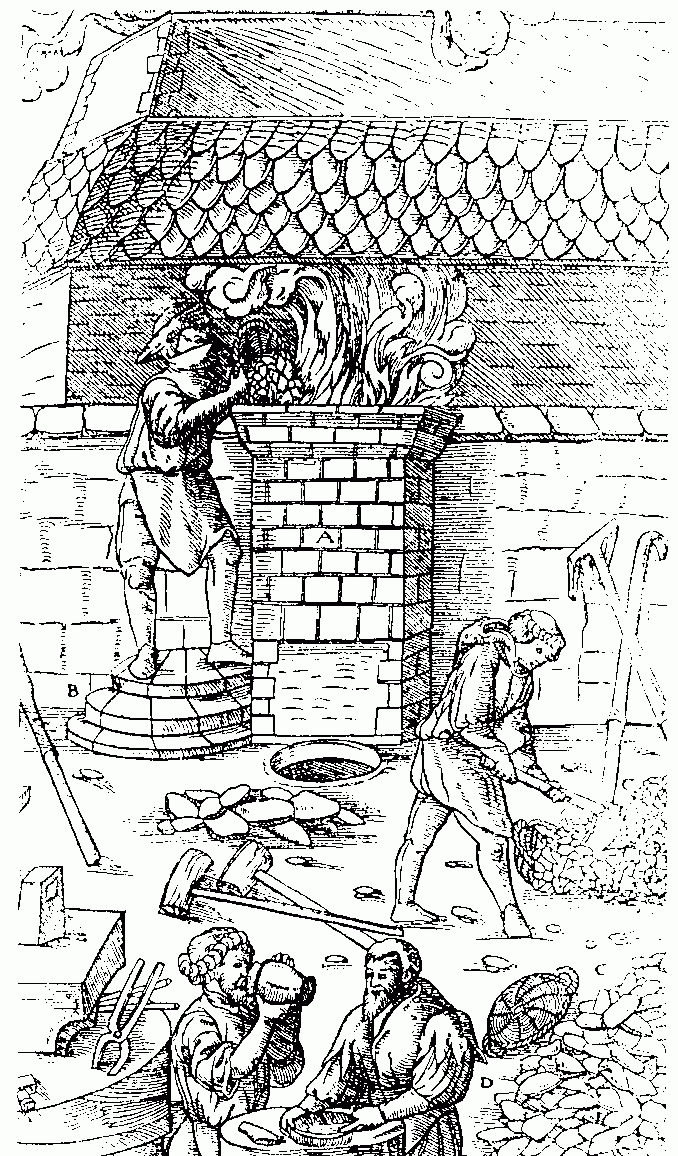

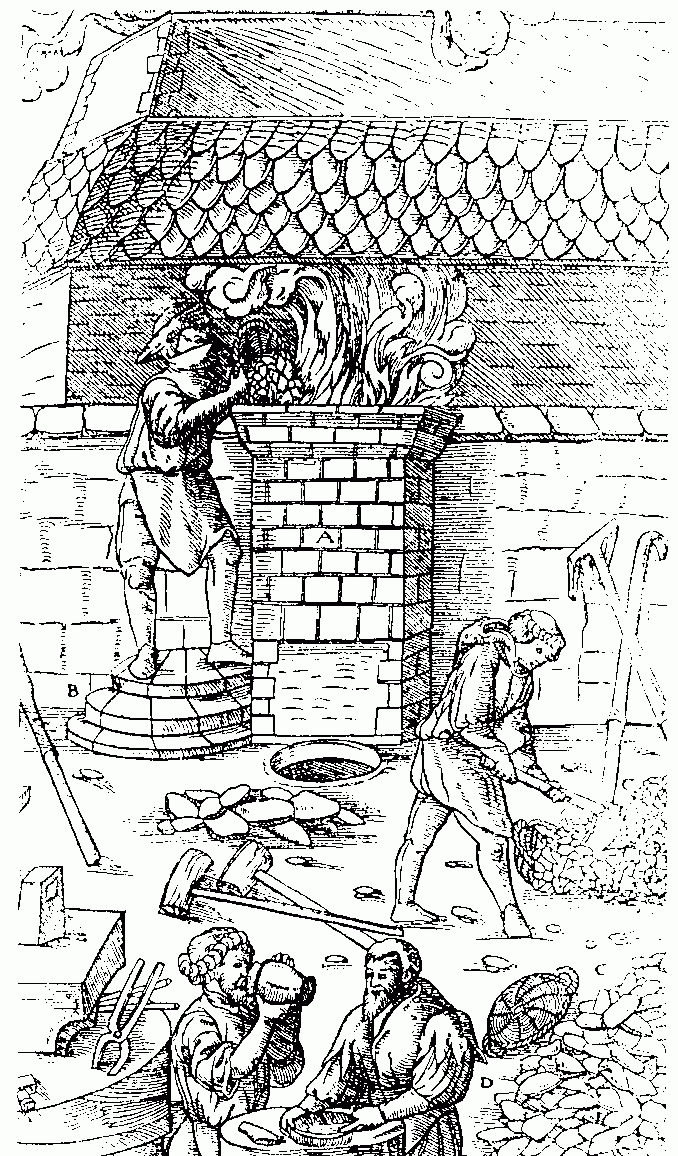

Since the 17th century, the first step in European steel production has been the smelting of iron ore into

Since the 17th century, the first step in European steel production has been the smelting of iron ore into pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate product of the iron industry in the production of steel which is obtained by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with silic ...

in a blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being "forced" or supplied above atmospheric ...

.Tylecote, R.F. (1992) ''A history of metallurgy'' 2nd ed., Institute of Materials, London. pp. 95–99 and 102–105. . Originally employing charcoal, modern methods use coke, which has proven more economical.

Processes starting from bar iron

In these processes pig iron was refined (fined) in afinery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and removing carbon from the molten cast iron through oxidation. Finery ...

to produce bar iron, which was then used in steel-making.

The production of steel by the cementation process was described in a treatise published in Prague in 1574 and was in use in Nuremberg from 1601. A similar process for case hardening armor and files was described in a book published in Naples in 1589. The process was introduced to England in about 1614 and used to produce such steel by Sir Basil Brooke (metallurgist), Basil Brooke at Coalbrookdale during the 1610s.

The raw material for this process were bars of iron. During the 17th century, it was realized that the best steel came from oregrounds iron of a region north of Stockholm, Sweden. This was still the usual raw material source in the 19th century, almost as long as the process was used.

Crucible steel is steel that has been melted in a crucible

A crucible is a ceramic or metal container in which metals or other substances may be melted or subjected to very high temperatures. While crucibles were historically usually made from clay, they can be made from any material that withstands te ...

rather than having been forging, forged, with the result that it is more homogeneous. Most previous furnaces could not reach high enough temperatures to melt the steel. The early modern crucible steel industry resulted from the invention of Benjamin Huntsman in the 1740s. Blister steel (made as above) was melted in a crucible or in a furnace, and cast (usually) into ingots.

Processes starting from pig iron

The modern era in

The modern era in steelmaking

Steelmaking is the process of producing steel from iron ore and carbon/or scrap. In steelmaking, impurities such as nitrogen, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur and excess carbon (the most important impurity) are removed from the sourced iron, and all ...

began with the introduction of Henry Bessemer's Bessemer process, process in 1855, the raw material for which was pig iron. His method let him produce steel in large quantities cheaply, thus mild steel came to be used for most purposes for which wrought iron was formerly used. The Gilchrist-Thomas process (or ''basic Bessemer process'') was an improvement to the Bessemer process, made by lining the converter with a basic (chemistry), basic material to remove phosphorus.

Another 19th-century steelmaking process was the Siemens-Martin process, which complemented the Bessemer process. It consisted of co-melting bar iron (or steel scrap) with pig iron.

These methods of steel production were rendered obsolete by the Linz-Donawitz process of

These methods of steel production were rendered obsolete by the Linz-Donawitz process of basic oxygen steelmaking

Basic oxygen steelmaking (BOS, BOP, BOF, or OSM), also known as Linz-Donawitz steelmaking or the oxygen converter processBrock and Elzinga, p. 50. is a method of primary steelmaking in which carbon-rich molten pig iron is made into steel. Blowin ...

(BOS), developed in 1952, and other oxygen steel making methods. Basic oxygen steelmaking is superior to previous steelmaking methods because the oxygen pumped into the furnace limited impurities, primarily nitrogen, that previously had entered from the air used, and because, with respect to the open hearth process, the same quantity of steel from a BOS process is manufactured in one-twelfth the time. Today, electric arc furnaces (EAF) are a common method of reprocessing scrap, scrap metal to create new steel. They can also be used for converting pig iron to steel, but they use a lot of electrical energy (about 440 kWh per metric ton), and are thus generally only economical when there is a plentiful supply of cheap electricity.

Industry

Recycling

Steel is one of the world's most-recycled materials, with a recycling rate of over 60% globally; in the United States alone, over were recycled in the year 2008, for an overall recycling rate of 83%. As more steel is produced than is scrapped, the amount of recycled raw materials is about 40% of the total of steel produced - in 2016, of crude steel was produced globally, with recycled.Contemporary

Carbon

Modern steels are made with varying combinations of alloy metals to fulfill many purposes. Carbon steel, composed simply of iron and carbon, accounts for 90% of steel production. Low alloy steel is alloyed with other elements, usuallymolybdenum

Molybdenum is a chemical element with the symbol Mo and atomic number 42 which is located in period 5 and group 6. The name is from Neo-Latin ''molybdaenum'', which is based on Ancient Greek ', meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lea ...

, manganese, chromium, or nickel, in amounts of up to 10% by weight to improve the hardenability of thick sections. HSLA steel, High strength low alloy steel has small additions (usually < 2% by weight) of other elements, typically 1.5% manganese, to provide additional strength for a modest price increase.

Recent Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) regulations have given rise to a new variety of steel known as Advanced High Strength Steel (AHSS). This material is both strong and ductile so that vehicle structures can maintain their current safety levels while using less material. There are several commercially available grades of AHSS, such as dual-phase steel, which is heat treated to contain both a ferritic and martensitic microstructure to produce a formable, high strength steel. Transformation Induced Plasticity (TRIP) steel involves special alloying and heat treatments to stabilize amounts of austenite

Austenite, also known as gamma-phase iron (γ-Fe), is a metallic, non-magnetic allotrope of iron or a solid solution of iron with an alloying element. In plain-carbon steel, austenite exists above the critical eutectoid temperature of 1000 K ...

at room temperature in normally austenite-free low-alloy ferritic steels. By applying strain, the austenite undergoes a phase transition to martensite without the addition of heat. Twinning Induced Plasticity (TWIP) steel uses a specific type of strain to increase the effectiveness of work hardening on the alloy.

Carbon Steels are often hot-dip galvanizing, galvanized, through hot-dip or electroplating in zinc for protection against rust.

Alloy

Stainless steels contain a minimum of 11% chromium, often combined with nickel, to resist

Stainless steels contain a minimum of 11% chromium, often combined with nickel, to resist corrosion

Corrosion is a natural process that converts a refined metal into a more chemically stable oxide. It is the gradual deterioration of materials (usually a metal) by chemical or electrochemical reaction with their environment. Corrosion engine ...

. Some stainless steels, such as the Allotropes of iron, ferritic stainless steels are magnetic, while others, such as the austenite, austenitic, are nonmagnetic. Corrosion-resistant steels are abbreviated as CRES.

Alloy steels are plain-carbon steels in which small amounts of alloying elements like chromium and vanadium have been added. Some more modern steels include tool steels, which are alloyed with large amounts of tungsten and cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, pr ...