Soviet atomic bomb project on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Soviet atomic bomb project was the classified research and development program that was authorized by

After a strong lobbying of Russian scientists, the

After a strong lobbying of Russian scientists, the

The

The

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union created at least nine

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union created at least nine

The Soviets started experimenting with nuclear technology in 1943 with very little regard of

The Soviets started experimenting with nuclear technology in 1943 with very little regard of  Contamination of air and soil due to atmospheric testing is only part of a wider issue. Water contamination due to improper disposal of spent

Contamination of air and soil due to atmospheric testing is only part of a wider issue. Water contamination due to improper disposal of spent

Collection of Archival Documents on the Soviet Nuclear Program

Wilson Center Digital Archive * , * Video archive o

Soviet Nuclear Testing

a

sonicbomb.com

* * .

Soviet and Nuclear Weapons History

German Scientists in the Soviet Atomic Project

Russian Nuclear Weapons Museum

(''in English'')

(''in Russian'') – RDS-1, RDS-6, Tsar Bomba, and an ICBM warhead

Cold War: A Brief History

Annotated bibliography on the Russian nuclear weapons program from the Alsos Digital Library

– CIA Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Soviet Atomic Bomb Project Nuclear weapons program of the Soviet Union Cold War history of the Soviet Union 1943 establishments in the Soviet Union 1949 disestablishments in the Soviet Union Nuclear weapons programme of Russia sv:Kärnteknik i Sovjetunionen

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

to develop nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s during and after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Although the Soviet scientific community discussed the possibility of an atomic bomb throughout the 1930s, going as far as making a concrete proposal to develop such a weapon in 1940, the full-scale program was not initiated and prioritized until Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

.

Because of the conspicuous silence of the scientific publications on the subject of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

by German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

, and British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

scientists, Russian physicist Georgy Flyorov

Georgii Nikolayevich Flyorov (also spelled Flerov, rus, Гео́ргий Никола́евич Флёров, p=gʲɪˈorgʲɪj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ ˈflʲɵrəf; 2 March 1913 – 19 November 1990) was a Soviet physicist who is known for h ...

suspected that the Allied powers had secretly been developing a "superweapon

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natur ...

" since 1939. Flyorov wrote a letter to Stalin urging him to start this program in 1942. Initial efforts were slowed due to the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

and remained largely composed of the intelligence gathering from the Soviet spy rings working in the U.S. Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

.

After Stalin learned of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

, the program was pursued aggressively and accelerated through effective intelligence gathering about the German nuclear weapon project

The Uranverein ( en, "Uranium Club") or Uranprojekt ( en, "Uranium Project") was the name given to the project in Germany to research nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, during World War II. It went through seve ...

and the American Manhattan Project. The Soviet efforts also rounded up captured German scientists to join their program, and relied on knowledge passed by spies to Soviet intelligence agencies.

On 29 August 1949, the Soviet Union secretly conducted its first successful weapon test (''First Lightning'', based on the American "Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

" design) at the Semipalatinsk-21 in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

. Stalin alongside Soviet political officials and scientists were elated at the successful test. A nuclear armed Soviet Union sent its rival Western neighbors, and particularly the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

into a state of unprecedented trepidation. From 1949 onwards the Soviet Union manufactured and tested nuclear weapons on a large scale. Its nuclear capabilities served as an important role on its global status. A nuclear armed Soviet Union escalated the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

with the United States to the possibility of nuclear war and ushered in the doctrine of mutually assured destruction

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would cause the ...

.

Early efforts

Background origins and roots

As early as 1910 in Russia, independent research was being conducted onradioactive element

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess nuclear energy, making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ways: emitted from the nucleus as gamma radiation; transfe ...

s by several Russian scientists. Despite the hardship faced by the Russian academy of sciences

An academy of sciences is a type of learned society or academy (as special scientific institution) dedicated to sciences that may or may not be state funded. Some state funded academies are tuned into national or royal (in case of the Unit ...

during the national revolution in 1917, followed by the violent civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

in 1922, Russian scientists had made remarkable efforts toward the advancement of physics research in the Soviet Union by the 1930s. Before the first revolution in 1905, the mineralogist Vladimir Vernadsky

Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky (russian: link=no, Влади́мир Ива́нович Верна́дский) or Volodymyr Ivanovych Vernadsky ( uk, Володи́мир Іва́нович Верна́дський; – 6 January 1945) was ...

had made a number of public calls for a survey of Russia's uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

deposits but none were heeded. Such early efforts were independently and privately funded by various organizations until 1922 when the Radium Institute in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(now Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

) opened and industrialized the research.

From the 1920s until the late 1930s, Russian physicists had been conducting joint research with their European counterparts on the advancement of atomic physics

Atomic physics is the field of physics that studies atoms as an isolated system of electrons and an atomic nucleus. Atomic physics typically refers to the study of atomic structure and the interaction between atoms. It is primarily concerned wit ...

at the Cavendish Laboratory run by a New Zealand physicist, Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson, (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who came to be known as the father of nuclear physics.

''Encyclopædia Britannica'' considers him to be the greatest ...

, where Georgi Gamov and Pyotr Kapitsa

Pyotr Leonidovich Kapitsa or Peter Kapitza ( Russian: Пётр Леонидович Капица, Romanian: Petre Capița ( – 8 April 1984) was a leading Soviet physicist and Nobel laureate, best known for his work in low-temperature physics ...

had studied and researched.

Influential research towards the advancement of nuclear physics was guided by Abram Ioffe, who was the director at the Leningrad Physical-Technical Institute (LPTI), having sponsored various research programs at various technical schools in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. The discovery of the neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

by the British physicist James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

further provided promising expansion of the LPTI's program, with the operation of the first cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Janu ...

to energies of over 1 MeV

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV, also written electron-volt and electron volt) is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating from rest through an electric potential difference of one volt in vacu ...

, and the first "splitting" of the atomic nucleus by John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft, (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was a British physicist who shared with Ernest Walton the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951 for splitting the atomic nucleus, and was instrumental in the development of nuclea ...

and Ernest Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton (6 October 1903 – 25 June 1995) was an Irish physicist and Nobel laureate. He is best known for his work with John Cockcroft to construct one of the earliest types of particle accelerator, the Cockcroft–Walton ...

. Russian physicists began pushing the government, lobbying in the interest of the development of science in the Soviet Union, which had received little interest due to the upheavals created during the Russian revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

and the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

. Earlier research was directed towards the medical and scientific exploration of radium

Radium is a chemical element with the symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, but it readily reacts with nitrogen (rather t ...

; a supply of it was available as it could be retrieved from borehole water from the Ukhta

Ukhta (russian: Ухта́; kv, Уква, ''Ukva'') is an important industrial town in the Komi Republic of Russia. Population:

It was previously known as ''Chibyu'' (until 1939).

History

Oil springs along the Ukhta River were already known in ...

oilfields.

In 1939, German chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

reported his discovery of fission, achieved by the splitting of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

with neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

s that produced the much lighter element barium. This eventually led to the realization among Russian scientists, and their American counterparts, that such reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure:

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

*Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

*Chain reaction (disambiguation).

Biology and me ...

could have military significance. The discovery excited the Russian physicists, and they began conducting their independent investigations on nuclear fission, mainly aiming towards power generation, as many were skeptical of possibility of creating an atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

anytime soon. Early efforts were led by Yakov Frenkel

__NOTOC__

Yakov Il'ich Frenkel (russian: Яков Ильич Френкель; 10 February 1894 – 23 January 1952) was a Soviet physicist renowned for his works in the field of condensed matter physics. He is also known as Jacov Frenkel, frequ ...

(a physicist specialised on condensed matter

Condensed matter physics is the field of physics that deals with the macroscopic and microscopic physical properties of matter, especially the solid and liquid phases which arise from electromagnetic forces between atoms. More generally, the su ...

), who did the first theoretical calculations on continuum mechanics

Continuum mechanics is a branch of mechanics that deals with the mechanical behavior of materials modeled as a continuous mass rather than as discrete particles. The French mathematician Augustin-Louis Cauchy was the first to formulate such m ...

directly relating the kinematics of binding energy

In physics and chemistry, binding energy is the smallest amount of energy required to remove a particle from a system of particles or to disassemble a system of particles into individual parts. In the former meaning the term is predominantly use ...

in fission process in 1940. Georgy Flyorov

Georgii Nikolayevich Flyorov (also spelled Flerov, rus, Гео́ргий Никола́евич Флёров, p=gʲɪˈorgʲɪj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ ˈflʲɵrəf; 2 March 1913 – 19 November 1990) was a Soviet physicist who is known for h ...

's and Lev Rusinov

Lev may refer to:

Common uses

*Bulgarian lev, the currency of Bulgaria

*an abbreviation for Leviticus, the third book of the Hebrew Bible and the Torah

People and fictional characters

*Lev (given name)

* Lev (surname)

Places

*Lev, Azerbaijan, ...

's collaborative work on thermal reactions concluded that 3-1 neutrons were emitted per fission only days after similar conclusions had been reached by the team of Frédéric Joliot-Curie

Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie (; ; 19 March 1900 – 14 August 1958) was a French physicist and husband of Irène Joliot-Curie, with whom he was jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1935 for their discovery of Induced radioactivity. T ...

.

World War II and accelerated feasibility

After a strong lobbying of Russian scientists, the

After a strong lobbying of Russian scientists, the Soviet government

The Government of the Soviet Union ( rus, Прави́тельство СССР, p=prɐˈvʲitʲɪlʲstvə ɛs ɛs ɛs ˈɛr, r=Pravítelstvo SSSR, lang=no), formally the All-Union Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, commonly ab ...

initially set up a commission that was to address the "uranium problem" and investigate the possibility of chain reaction and isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

. The Uranium Problem Commission was ineffective because the German invasion German invasion may refer to:

Pre-1900s

* German invasion of Hungary (1063)

World War I

* German invasion of Belgium (1914)

* German invasion of Luxembourg (1914)

World War II

* Invasion of Poland

* German invasion of Belgium (1940)

* G ...

of Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

eventually limited the focus on research, as Russia became engaged in a bloody conflict along the Eastern Front for the next four years. The Soviet atomic weapons program had no significance, and most work was unclassified as the papers were continuously published as public domain in academic journals.

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, the Soviet leader, had mostly disregarded the atomic knowledge possessed by the Russian scientists as had most of the scientists working in the metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

and mining industry

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic via ...

or serving in the Soviet Armed Forces

The Soviet Armed Forces, the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union and as the Red Army (, Вооружённые Силы Советского Союза), were the armed forces of the Russian SFSR (1917–1922), the Soviet Union (1922–1991), and th ...

technical branches during the World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

's eastern front in 1940–42.

In 1940–42, Georgy Flyorov

Georgii Nikolayevich Flyorov (also spelled Flerov, rus, Гео́ргий Никола́евич Флёров, p=gʲɪˈorgʲɪj nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ ˈflʲɵrəf; 2 March 1913 – 19 November 1990) was a Soviet physicist who is known for h ...

, a Russian physicist serving as an officer in the Soviet Air Force

The Soviet Air Forces ( rus, Военно-воздушные силы, r=Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, VVS; literally "Military Air Forces") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The Air Forces ...

, noted that despite progress in other areas of physics, the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, and American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

scientists had ceased publishing papers on nuclear science. Clearly, they each had active secret research programs. The dispersal of Soviet scientists had sent Abram Ioffe’s Radium Institute from Leningrad to Kazan; and the wartime research program put the "uranium bomb" programme third, after radar and anti-mine protection for ships. Kurchatov had moved from Kazan to Murmansk to work on mines for the Soviet Navy.

In April 1942, Flyorov directed two classified letters to Stalin, warning him of the consequences of the development of atomic weapons: "the results will be so overriding hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

it won't be necessary to determine who is to blame for the fact that this work has been neglected in our country." The second letter, by Flyorov and Konstantin Petrzhak

Konstantin Antonovich Petrzhak (alternatively Pietrzak; rus, Константи́н Анто́нович Пе́тржак, p=kənstɐnʲˈtʲin ɐnˈtonəvʲɪtɕ ˈpʲedʐək, ; 4 September 1907– 10 October 1998), , was a Russian physicist o ...

, highly emphasized the importance of a "uranium bomb": "it is essential to manufacture a uranium bomb without a delay."

Upon reading the Flyorov letters, Stalin immediately pulled Russian physicists from their respective military services and authorized an atomic bomb project, under engineering physicist Anatoly Alexandrov and nuclear physicist

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

Igor V. Kurchatov. For this purpose, the Laboratory No. 2 near Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

was established under Kurchatov. Kurchatov was chosen in late 1942 as the technical director of the Soviet bomb program; he was awed by the magnitude of the task but was by no means convinced of its utility against the demands of the front. Abram Ioffe had refused the post as he was ''too old'', and recommended the young Kurchatov.

At the same time, Flyorov was moved to Dubna

Dubna ( rus, Дубна́, p=dʊbˈna) is a town in Moscow Oblast, Russia. It has a status of ''naukograd'' (i.e. town of science), being home to the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, an international nuclear physics research center and one o ...

, where he established the Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions, focusing on synthetic element

A synthetic element is one of 24 known chemical elements that do not occur naturally on Earth: they have been created by human manipulation of fundamental particles in a nuclear reactor, a particle accelerator, or the explosion of an atomic bomb; ...

s and thermal reactions. In late 1942, the State Defense Committee officially delegated the program to the Soviet Army

uk, Радянська армія

, image = File:Communist star with golden border and red rims.svg

, alt =

, caption = Emblem of the Soviet Army

, start_date ...

, with major wartime logistical efforts later being supervised by Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolsheviks ...

, the head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple animals may ...

of NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

.

In 1945, the Arzamas 16

Sarov (russian: Саро́в) is a closed town in Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It was known as Gorkiy-130 (Горький-130) and Arzamas-16 (), after a (somewhat) nearby town of Arzamas,SarovLabsCreation of Nuclear Center Arzamas-16/ref ...

site, near Moscow, was established under Yakov Zel'dovich and Yuli Khariton

Yulii Borisovich Khariton (Russian: Юлий Борисович Харитон, 27 February 1904 – 19 December 1996), also known as YuB, , was a Russian physicist who was a leading scientist in the former Soviet Union's program of nuclear wea ...

who performed calculations on nuclear combustion theory, alongside Isaak Pomeranchuk

Isaak Yakovlevich Pomeranchuk (russian: Исаа́к Я́ковлевич Померанчу́к (Polish spelling: Isaak Jakowliewicz Pomieranczuk); 20 May 1913, Warsaw, Russian Empire – 14 December 1966, Moscow, USSR) was a Soviet physicist ...

. Despite early and accelerated efforts, it was reported by historians that efforts on building a bomb using weapon-grade uranium seemed hopeless to Russian scientists. Igor Kurchatov had harboured doubts working towards the uranium bomb, but made progress on a bomb using weapon-grade plutonium after British data was provided by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

.

The situation dramatically changed when the Soviet Union learned of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

in 1945.

Immediately after the atomic bombing, the Soviet Politburo

The Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (, abbreviated: ), or Politburo ( rus, Политбюро, p=pəlʲɪtbʲʊˈro) was the highest policy-making authority within the Communist Party of the ...

took control of the atomic bomb project by establishing a special committee to oversee the development of nuclear weapons as soon as possible. On 9 April 1946, the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

created KB–11 ('Design Bureau-11') that worked towards mapping the first nuclear weapon design

Nuclear weapon designs are physical, chemical, and engineering arrangements that cause the physics package of a nuclear weapon to detonate. There are three existing basic design types:

* pure fission weapons, the simplest and least technically ...

, primarily based on the American approach and detonated with weapon-grade plutonium. From then on work on the program was carried out quickly, resulting in the first nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

near Moscow on 25 October 1946.

Organization and administration

The German assistance

From 1941 to 1946, the Soviet Union'sMinistry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

handled the logistics of the atomic bomb project, with Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between cou ...

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

controlling the direction of the program. However, Molotov proved to be a weak administrator, and the program stagnated. In contrast to American military administration

Military administration identifies both the techniques and systems used by military departments, agencies, and armed services involved in managing the armed forces. It describes the processes that take place within military organisations outsid ...

in their atomic bomb project, the Russians' program was directed by political dignitaries such as Molotov, Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolsheviks ...

, Georgii Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov ( – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who briefly succeeded Joseph Stalin as the leader of the Soviet Union. However, at the insistence of the rest of the Presidium, he relinquished control over the pa ...

, and Mikhail Pervukhin

Mikhail Georgievich Pervukhin (russian: Михаи́л Гео́ргиевич Перву́хин; 14 October 1904 – 22 July 1978) was a Soviet official during the Stalin Era and Khrushchev Era. He served as a First Deputy Chairman of the C ...

—there were no military members.

After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the program's leadership changed, when Stalin appointed Lavrentiy Beria on 22 August 1945. Beria is noted for leadership that helped the program to its final implementation.

The new Committee, under Beria, retained Georgii Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov ( – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who briefly succeeded Joseph Stalin as the leader of the Soviet Union. However, at the insistence of the rest of the Presidium, he relinquished control over the pa ...

and added Nikolai Voznesensky

Nikolai Alekseevich Voznesensky (russian: Никола́й Алексе́евич Вознесе́нский, – 1 October 1950) was a Soviet politician and economic planner who oversaw the running of Gosplan (State Planning Committee) dur ...

and Boris Vannikov

Boris Lvovich Vannikov (russian: Бори́с Льво́вич Ва́нников; 26 August 1897 – 22 February 1962) was a Soviet government official and three-star general.

Vannikov was People's Commissar for Defense Industry from Decembe ...

, People's Commissar for Armament. Under the administration of Beria, the NKVD co-opted atomic spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early ...

of the Soviet Atomic Spy Ring

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have espionage, illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the ea ...

into the Western Allied program, and infiltrated the German nuclear program

The Uranverein ( en, "Uranium Club") or Uranprojekt ( en, "Uranium Project") was the name given to the project in Germany to research nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, during World War II. It went through seve ...

whose scientists were later forced to work in Soviet nuclear efforts.

Espionage

Soviet atomic ring

The

The nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

* Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

and industrial

Industrial may refer to:

Industry

* Industrial archaeology, the study of the history of the industry

* Industrial engineering, engineering dealing with the optimization of complex industrial processes or systems

* Industrial city, a city dominate ...

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

s in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

by American sympathisers of communism who were controlled by their ''rezident A resident spy in the world of espionage is an agent operating within a foreign country for extended periods of time. A base of operations within a foreign country with which a resident spy may liaise is known as a "station" in English and a (, 're ...

'' Russian officials in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

greatly aided the speed of the Soviet nuclear program from 1942–54. The willingness in sharing classified information to the Soviet Union by recruited American communist sympathizers increased when the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

faced possible defeat during the German invasion German invasion may refer to:

Pre-1900s

* German invasion of Hungary (1063)

World War I

* German invasion of Belgium (1914)

* German invasion of Luxembourg (1914)

World War II

* Invasion of Poland

* German invasion of Belgium (1940)

* G ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The Russian intelligence network in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

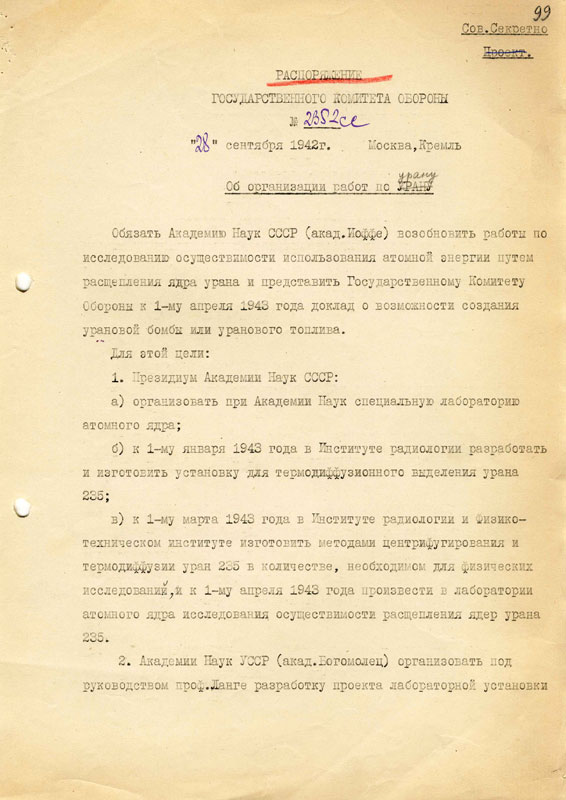

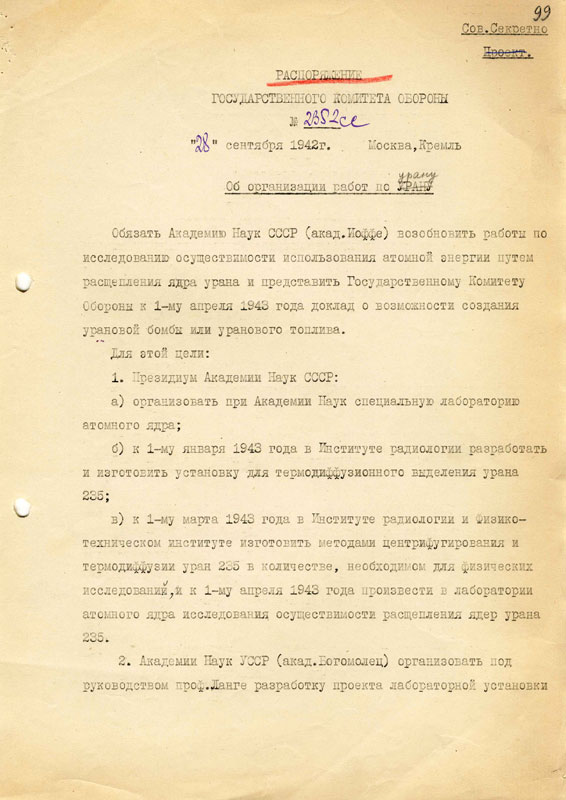

also played a vital role in setting up the spy rings in the United States when the Russian State Defense Committee approved resolution 2352 in September 1942.

For this purpose, the spy Harry Gold

Harry Gold (born Henrich Golodnitsky, December 11, 1910 – August 28, 1972) was a Swiss-born American laboratory chemist who was convicted as a courier for the Soviet Union passing atomic secrets from Klaus Fuchs, an agent of the Soviet Union, ...

, controlled by Semyon Semyonov, was used for a wide range of espionage that included industrial espionage in the American chemical industry

The chemical industry comprises the companies that produce industrial chemicals. Central to the modern world economy, it converts raw materials (oil, natural gas, air, water, metals, and minerals) into more than 70,000 different products. The ...

and obtaining sensitive atomic information that was handed over to him by the British physicist Klaus Fuchs. Knowledge and further technical information that were passed by the American Theodore Hall

Theodore Alvin Hall (October 20, 1925 – November 1, 1999) was an American physicist and an atomic spy for the Soviet Union, who, during his work on United States efforts to develop the first and second atomic bombs during World War II ...

, a theoretical physicist, and Klaus Fuchs had a significant impact on the direction of Russian development of nuclear weapons.

Leonid Kvasnikov

Leonid Romanovich Kvasnikov (Russian: Леонид Романович Квасников; 2 June 1905 – 15 October 1993) was a Soviet and Russian chemical engineer and a spy, serving first in NKVD and later served in KGB. Graduated with honor ...

, a Russian engineer turned KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

officer, was assigned for this special purpose and moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

to coordinate such activities. Anatoli Yatzkov, another NKVD official in New York, was also involved in obtaining sensitive information gathered by Sergei Kournakov from Saville Sax

Saville Sax (July 26, 1924 – September 25, 1980) was the Harvard College roommate of Theodore Hall who recruited Hall for the Soviets and acted as a courier to move the atomic secrets from Los Alamos to the Soviets.

Biography

Saville Sax was ...

.

The existence of Russian spies was exposed by the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

's secretive Venona project

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (later absorbed by the National Security Agency), which ran from February 1, 1943, until Octob ...

in 1943.

For example, Soviet work on methods of uranium isotope separation was altered when it was reported, to Kurchatov's surprise, that the Americans had opted for the Gaseous diffusion method. While research on other separation methods continued throughout the war years, the emphasis was placed on replicating U.S. success with gaseous diffusion. Another important breakthrough, attributed to intelligence, was the possibility of using plutonium instead of uranium in a fission weapon. Extraction of plutonium in the so-called "uranium pile" allowed bypassing of the difficult process of uranium separation altogether, something that Kurchatov had learned from intelligence from the Manhattan project.

Soviet intelligence management in the Manhattan Project

In 1945, the Soviet intelligence obtained rough blueprints of the first U.S. atomic device. Alexei Kojevnikov has estimated, based on newly released Soviet documents, that the primary way in which the espionage may have sped up the Soviet project was that it allowed Khariton to avoid dangerous tests to determine the size of the critical mass: "tickling the dragon's tail", as it was called in the U.S., consumed a good deal of time and claimed at least two lives; seeHarry Daghlian

Haroutune Krikor Daghlian Jr. (May 4, 1921 – September 15, 1945) was an American physicist with the Manhattan Project, which designed and produced the atomic bombs that were used in World War II. He accidentally irradiated himself on August ...

and Louis Slotin

Louis Alexander Slotin (1 December 1910 – 30 May 1946) was a Canadian physicist and chemist who took part in the Manhattan Project. Born and raised in the North End of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Slotin earned both his Bachelor of Science and M ...

.

The published Smyth Report

The Smyth Report (officially ''Atomic Energy for Military Purposes'') is the common name of an administrative history written by American physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth about the Manhattan Project, the Allied effort to develop atomic bombs du ...

of 1945 on the Manhattan Project was translated into Russian, and the translators noted that a sentence on the effect of "poisoning" of Plutonium-239 in the first (lithograph) edition had been deleted from the next (Princeton) edition by Groves. This change was noted by the Russian translators, and alerted the Soviet Union to the problem (which had meant that reactor-bred plutonium could not be used in a simple gun-type bomb like the proposed Thin Man).

One of the key pieces of information, which Soviet intelligence obtained from Fuchs, was a cross-section for D-T fusion. This data was available to top Soviet officials roughly three years before it was openly published in the ''Physical Review'' in 1949. However, this data was not forwarded to Vitaly Ginzburg

Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg, ForMemRS (russian: Вита́лий Ла́заревич Ги́нзбург, link=no; 4 October 1916 – 8 November 2009) was a Russian physicist who was honored with the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2003, together with ...

or Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for nu ...

until very late, practically months before publication. Initially both Ginzburg and Sakharov estimated such a cross-section to be similar to the D-D reaction. Once the actual cross-section become known to Ginzburg and Sakharov, the Sloika design become a priority, which resulted in a successful test in 1953.

In the 1990s, with the declassification of Soviet intelligence materials, which showed the extent and the type of the information obtained by the Soviets from US sources, a heated debate ensued in Russia and abroad as to the relative importance of espionage, as opposed to the Soviet scientists' own efforts, in the making of the Soviet bomb. The vast majority of scholars agree that whereas the Soviet atomic project was first and foremost a product of local expertise and scientific talent, it is clear that espionage efforts contributed to the project in various ways and most certainly shortened the time needed to develop the atomic bomb.

Comparing the timelines of H-bomb development, some researchers came to the conclusion that the Soviets had a gap in access to classified information regarding the H-bomb at least between late 1950 and some time in 1953. Earlier, e.g., in 1948, Fuchs gave the Soviets a detailed update of the classical super progress, including an idea to use lithium, but did not explain it was specifically lithium-6. By 1951 Teller accepted the fact that the "classical super" scheme wasn't feasible, following results obtained by various researchers (including Stanislaw Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapon ...

) and calculations performed by John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

in late 1950.

Yet the research for the Soviet analogue of "classical super" continued until December 1953, when the researchers were reallocated to a new project working on what later became a true H-bomb design, based on radiation implosion. This remains an open topic for research, whether the Soviet intelligence was able to obtain any specific data on Teller-Ulam design in 1953 or early 1954. Yet, Soviet officials directed the scientists to work on a new scheme, and the entire process took less than two years, commencing around January 1954 and producing a successful test in November 1955. It also took just several months before the idea of radiation implosion was conceived, and there is no documented evidence claiming priority. It is also possible that Soviets were able to obtain a document lost by John Wheeler on a train in 1953, which reportedly contained key information about thermonuclear weapon design.

Initial thermonuclear designs

Early ideas of the fusion bomb came from espionage and internal Soviet studies. Though the espionage did help Soviet studies, the early American H-bomb concepts had substantial flaws, so it may have confused, rather than assisted, the Soviet effort to achieve nuclear capability. The designers of early thermonuclear bombs envisioned using an atomic bomb as a trigger to provide the needed heat and compression to initiate the thermonuclear reaction in a layer of liquid deuterium between the fissile material and the surrounding chemical high explosive. The group would realize that a lack of sufficient heat and compression of the deuterium would result in an insignificant fusion of the deuterium fuel. Andrei Sakharov's study group at FIAN in 1948 came up with a second concept in which adding a shell of natural, unenriched uranium around the deuterium would increase the deuterium concentration at the uranium-deuterium boundary and the overall yield of the device, because the natural uranium would capture neutrons and itself fission as part of the thermonuclear reaction. This idea of a layered fission-fusion-fission bomb led Sakharov to call it the sloika, or layered cake. It was also known as the RDS-6S, or Second Idea Bomb. This second bomb idea was not a fully evolved thermonuclear bomb in the contemporary sense, but a crucial step between pure fission bombs and the thermonuclear "supers". Due to the three-year lag in making the key breakthrough of radiation compression from the United States the Soviet Union's development efforts followed a different course of action. In the United States they decided to skip the single-stage fusion bomb and make a two-stage fusion bomb as their main effort. Unlike the Soviet Union, the analog RDS-7 advanced fission bomb was not further developed, and instead, the single-stage 400-kiloton RDS-6S was the Soviet's bomb of choice. The RDS-6S Layer Cake design was detonated on 12 August 1953, in a test given the code name by the Allies of "Joe 4

Joe 4 was an American nickname for the first Soviet test of a thermonuclear weapon on August 12, 1953, that detonated with a force equivalent to 400 kilotons of TNT. The proper Soviet terminology for the warhead was RDS-6s, , .

RDS-6 utilized a ...

". The test produced a yield of 400 kilotons, about ten times more powerful than any previous Soviet test. Around this time the United States detonated its first super using radiation compression on 1 November 1952, code-named Mike. Though the Mike was about twenty times greater than the RDS-6S, it was not a design that was practical to use, unlike the RDS-6S.

Following the successful launching of the RDS-6S

Joe 4 was an American nickname for the first Soviet test of a thermonuclear weapon on August 12, 1953, that detonated with a force equivalent to 400 kilotons of TNT. The proper Soviet terminology for the warhead was RDS-6s, , .

RDS-6 utilized a ...

, Sakharov proposed an upgraded version called RDS-6SD. This bomb was proved to be faulty, and it was neither built nor tested. The Soviet team had been working on the RDS-6T concept, but it also proved to be a dead end.

In 1954, Sakharov worked on a third concept, a two-stage thermonuclear bomb. The third idea used the radiation wave of a fission bomb, not simply heat and compression, to ignite the fusion reaction, and paralleled the discovery made by Ulam and Teller. Unlike the RDS-6S boosted bomb, which placed the fusion fuel inside the primary A-bomb trigger, the thermonuclear super placed the fusion fuel in a secondary structure a small distance from the A-bomb trigger, where it was compressed and ignited by the A-bomb's x-ray radiation. The KB-11

The All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Experimental Physics (VNIIEF) (russian: Всероссийский научно-исследовательский институт экспериментальной физики) is a research inst ...

Scientific-Technical Council approved plans to proceed with the design on 24 December 1954. Technical specifications for the new bomb were completed on 3 February 1955, and it was designated the RDS-37

RDS-37 was the Soviet Union's first two-stage hydrogen bomb, first tested on 22 November 1955. The weapon had a nominal yield of approximately 3 megatons. It was scaled down to 1.6 megatons for the live test.

Leading to the RDS-37

The RDS-3 ...

.

The RDS-37 was successfully tested on 22 November 1955 with a yield of 1.6 megaton. The yield was almost a hundred times greater than the first Soviet atomic bomb six years before, showing that the Soviet Union could compete with the United States. and would even exceed them in time.

Logistical problems

The single largest problem during the early Soviet program was the procurement of rawuranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

ore, as the Soviet Union had limited domestic sources at the beginning of their nuclear program. The era of domestic uranium mining can be dated exactly, to November 27, 1942, the date of a directive issued by the all-powerful wartime State Defense Committee. The first Soviet uranium mine was established in Taboshar

tg, Истиқлол

, image_skyline =

, imagesize =

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, image_seal =

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Tajikistan

, pushpin_label_position =bottom

, pushpin_mapsize =

, pushp ...

, present-day Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

, and was producing at an annual rate of a few tons of uranium concentrate

Triuranium octoxide (U3O8) is a compound of uranium. It is present as an olive green to black, odorless solid. It is one of the more popular forms of yellowcake and is shipped between mills and refineries in this form.

U3O8 has potential long-ter ...

by May 1943. Taboshar was the first of many officially secret Soviet closed cities

A closed city or closed town is a settlement where travel or residency restrictions are applied so that specific authorization is required to visit or remain overnight. Such places may be sensitive military establishments or secret research ins ...

related to uranium mining and production.

Demand from the experimental bomb project was far higher. The Americans, with the help of Belgian businessman Edgar Sengier

Edgar Edouard Bernard Sengier (9 October 1879 – 26 July 1963) was a Belgian mining engineer and director of the Union Minière du Haut Katanga mining company that operated in Belgian Congo during World War II.

Sengier is credited with ...

in 1940, had already blocked access to known sources in Congo, South Africa, and Canada. In December 1944 Stalin took the uranium project away from Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

and gave to it to Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolsheviks ...

. The first Soviet uranium processing plant was established as the Leninabad Mining and Chemical Combine Leninabad may refer to:

Azerbaijan

* Kərimbəyli, Babek

* Sanqalan

* Təklə, Gobustan

* Yeni yol, Shamkir

Tajikistan

*Khujand

Khujand ( tg, Хуҷанд, Khujand; Uzbek: Хўжанд, romanized: Хo'jand; fa, خجند, Khojand), some ...

in Chkalovsk (present-day Buston, Ghafurov District

, image_skyline = File:Chkalovsk, Tajikistan - panoramio (5).jpg

, imagesize =

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, image_seal =

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Tajikistan

, pushpin_label_position =bottom

, pushpin_maps ...

), Tajikistan, and new production sites identified in relative proximity. This posed a need for labor, a need that Beria would fill with forced labor: tens of thousands of Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

prisoners were brought to work in the mines, the processing plants, and related construction.

Domestic production was still insufficient when the Soviet F-1 reactor, which began operation in December 1946, was fueled using uranium confiscated from the remains of the German atomic bomb project

The Uranverein ( en, "Uranium Club") or Uranprojekt ( en, "Uranium Project") was the name given to the project in Germany to research nuclear technology, including nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors, during World War II. It went through s ...

. This uranium had been mined in the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

, and the ore in Belgium fell into the hands of the Germans after their invasion and occupation of Belgium in 1940. In 1945, the Uranium enrichment through electromagnetic method under Lev Artsimovich

Lev Andreyevich Artsimovich (Russian: Лев Андреевич Арцимович, February 25, 1909 – March 1, 1973), also transliterated Arzimowitsch, was a Soviet physicist who is regarded as the one of the founder of Tokamak— a device t ...

also failed due to USSR's inability to build the parallel American Oak Ridge site and the limited power grid system could not produce the electricity for their program.

Further sources of uranium in the early years of the program were mines in East Germany (via the deceptively-named SAG Wismut), Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania (the Băița mine

The Băița mine is a large open pit mine in the northwest of Romania in Bihor County, close to Ștei, southeast of Oradea and northwest of the capital, Bucharest. Băița represents the largest uranium reserve in Romania having estimated reser ...

near Ștei

Ștei ( hu, Vaskohsziklás) is a town in Bihor County,

Crișana, Romania. Between 1958 and 1996, it was named ''Dr. Petru Groza'', after the Romanian socialist leader who died in 1958.

History

The town was founded in 1952, near a village of ...

) and Poland. Boris Pregel Boris Pregel (russian: Борис Юльевич Прегель; 24 January 1893 – 7 December 1976) was a Russian Empire-born Jewish engineer and dealer in uranium and radium. He was born in Odessa, in the Russian Empire, and studied engineering ...

sold 0.23 tonnes of uranium oxide to the Soviet Union during the war, with the authorisation of the U.S. Government.

Eventually, large domestic sources were discovered in the Soviet Union (including those now in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

).

The uranium for the Soviet nuclear weapons program came from mine production in the following countries,Chronik der Wismut, Wismut GmbH 1999

Important nuclear tests

RDS-1

RDS-1

The RDS-1 (russian: РДС-1), also known as Izdeliye 501 (device 501) and First Lightning (), was the nuclear bomb used in the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test. The United States assigned it the code-name Joe-1, in reference to Joseph ...

, the first Soviet atomic test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

was internally code-named ''First Lightning'' (''Первая молния'', or Pervaya Molniya) August 29, 1949, and was code-named by the Americans

Americans are the Citizenship of the United States, citizens and United States nationality law, nationals of the United States, United States of America.; ; Although direct citizens and nationals make up the majority of Americans, many Multi ...

as ''Joe 1''. The design was very similar to the first US "Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

" plutonium bomb, using a TNT

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reagen ...

/hexogen

RDX (abbreviation of "Research Department eXplosive") or hexogen, among other names, is an organic compound with the formula (O2N2CH2)3. It is a white solid without smell or taste, widely used as an explosive. Chemically, it is classified as a ...

implosion lens design.

RDS-2

On September 24, 1951, the 38.3 kiloton deviceRDS-2 The RDS-2 (Russian: РДС-2) was the second atomic bomb developed by the Soviet Union as an improved version of the RDS-1. It included new explosive lenses along with a new core design to decrease the probability of pre-detonation or 'fizzle'. T ...

was tested based on a tritium " boosted" uranium implosion device with a levitated core. This test was code named ''Joe 2'' by the CIA.

RDS-3

RDS-3 RDS-3 was the third atomic bomb developed by the Soviet Union in 1951, after the famous RDS-1 and RDS-2. It was called ''Marya'' in the military. The bomb had a composite design with a plutonium core inside a uranium shell, providing an explosive p ...

was the third Soviet atomic bomb. On October 18, 1951, the 41.2 kiloton device was detonated - a boosted weapon using a composite construction of levitated plutonium core

The pit, named after the hard core found in fruits such as peaches and apricots, is the core of an implosion nuclear weapon – the fissile material and any neutron reflector or tamper bonded to it. Some weapons tested during the 1950s used ...

and a uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exis ...

shell. Code named ''Joe 3'' in the USA, this was the first Soviet air-dropped bomb test. Released at an altitude of 10 km, it detonated 400 meters above the ground.

RDS-4

RDS-4

RDS-4 (also known as ''Tatyana'') was a Soviet nuclear bomb that was first tested at Semipalatinsk Test Site, on August 23, 1953. The device weighed approximately . The device was approximately one-third the size of the RDS-3. The bomb was dropped ...

represented a branch of research on small tactical weapons. It was a boosted fission device using plutonium in a "levitated" core design. The first test was an air drop on August 23, 1953, yielding 28 kilotons. In 1954, the bomb was also used during Snowball

A snowball is a spherical object made from snow, usually created by scooping snow with the hands, and pressing the snow together to compact it into a ball. Snowballs are often used in games such as snowball fights.

A snowball may also be a large ...

exercise in Totskoye

Totskoye (russian: То́цкое) is a rural locality (a '' selo'') and the administrative center of Totsky District of Orenburg Oblast, Russia. Population:

During World War I, it was the site of a prisoner-of-war camp that became notorious ...

, dropped by Tu-4 bomber on the simulated battlefield, in the presence of 40,000 infantry, tanks, and jet fighters. The RDS-4 comprised the warhead of the R-5M, the first medium-range ballistic missile in the world, which was tested with a live warhead for the first and only time on February 5, 1956

RDS-5

RDS-5 The RDS-5 (russian: РДС-5) was a plutonium based Soviet atomic bomb, probably using a hollow core. Two versions were made. The first version used 2 kg Pu-239 and was expected to yield 9.2 kilotons. The second version used only 0.8 kg Pu-239

Te ...

was a small plutonium based device, probably using a hollow core. Two different versions were made and tested.

RDS-6

RDS-6

Joe 4 was an American nickname for the first Soviet test of a thermonuclear weapon on August 12, 1953, that detonated with a force equivalent to 400 kilotons of TNT. The proper Soviet terminology for the warhead was RDS-6s, , .

RDS-6 utilized a ...

, the first Soviet test of a hydrogen bomb, took place on August 12, 1953, and was nicknamed ''Joe 4'' by the Americans. It used a layer-cake design of fission and fusion fuels (uranium 235 and lithium-6 deuteride) and produced a yield of 400 kilotons. This yield was about ten times more powerful than any previous Soviet test. When developing higher level bombs, the Soviets proceeded with the RDS-6 as their main effort instead of the analog RDS-7 advanced fission bomb. This led to the third idea bomb which is the RDS-37

RDS-37 was the Soviet Union's first two-stage hydrogen bomb, first tested on 22 November 1955. The weapon had a nominal yield of approximately 3 megatons. It was scaled down to 1.6 megatons for the live test.

Leading to the RDS-37

The RDS-3 ...

.

RDS-9

A much lower-power version of the RDS-4 with a 3-10 kiloton yield, the RDS-9 was developed for the T-5 nuclear torpedo. A 3.5 kiloton underwater test was performed with the torpedo on September 21, 1955.RDS-37

The first Soviet test of a "true" hydrogen bomb in the megaton range was conducted on November 22, 1955. It was dubbed ''RDS-37

RDS-37 was the Soviet Union's first two-stage hydrogen bomb, first tested on 22 November 1955. The weapon had a nominal yield of approximately 3 megatons. It was scaled down to 1.6 megatons for the live test.

Leading to the RDS-37

The RDS-3 ...

'' by the Soviets. It was of the multi-staged, radiation implosion

Radiation implosion is the compression of a target by the use of high levels of electromagnetic radiation. The major use for this technology is in fusion bombs and inertial confinement fusion research.

History

Radiation implosion was first deve ...

thermonuclear design called ''Sakharov's "Third Idea"'' in the USSR and the Teller–Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a low ...

in the USA.

Joe 1, Joe 4, and RDS-37 were all tested at the Semipalatinsk Test Site

The Semipalatinsk Test Site (Russian language, Russian: Семипалатинск-21; Semipalatinsk-21), also known as "The Polygon", was the primary testing venue for the Soviet Union's nuclear weapons. It is located on the steppe in northeast ...

in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

.

Tsar Bomba (RDS-220)

TheTsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei Sa ...

(Царь-бомба) was the largest, most powerful thermonuclear weapon ever detonated. It was a three-stage hydrogen bomb with a yield of about 50 megatons

TNT equivalent is a convention for expressing energy, typically used to describe the energy released in an explosion. The is a unit of energy defined by that convention to be , which is the approximate energy released in the detonation of a m ...

. This is equivalent to ten times the amount of all the explosives used in World War II combined. It was detonated on October 30, 1961, in the Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; rus, Но́вая Земля́, p=ˈnovəjə zʲɪmˈlʲa, ) is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, ...

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

, and was capable of approximately 100 megatons

TNT equivalent is a convention for expressing energy, typically used to describe the energy released in an explosion. The is a unit of energy defined by that convention to be , which is the approximate energy released in the detonation of a m ...

, but was purposely reduced shortly before the launch. Although weapon

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

ized, it was not entered into service; it was simply a demonstrative testing of the capabilities of the Soviet Union's military technology at that time. The heat of the explosion was estimated to potentially inflict third degree burn

A burn is an injury to skin, or other tissues, caused by heat, cold, electricity, chemicals, friction, or ultraviolet radiation (like sunburn). Most burns are due to heat from hot liquids (called scalding), solids, or fire. Burns occur mai ...

s at 100 km distance of clear air.

Chagan

Chagan was a shot in theNuclear Explosions for the National Economy

Nuclear Explosions for the National Economy (russian: Ядерные взрывы для народного хозяйства, Yadernyye vzryvy dlya narodnogo khozyaystva; sometimes referred to as ''Program #7'') was a Soviet program to investiga ...

(also known as Project 7), the Soviet equivalent of the US ''Operation Plowshare

Project Plowshare was the overall United States program for the development of techniques to use nuclear explosives for peaceful construction purposes. The program was organized in June 1957 as part of the worldwide Atoms for Peace efforts. As ...

'' to investigate peaceful uses of nuclear weapons. It was a subsurface detonation. It was fired on January 15, 1965. The site was a dry bed of the river Chagan at the edge of the Semipalatinsk Test Site

The Semipalatinsk Test Site (Russian language, Russian: Семипалатинск-21; Semipalatinsk-21), also known as "The Polygon", was the primary testing venue for the Soviet Union's nuclear weapons. It is located on the steppe in northeast ...

, and was chosen such that the lip of the crater would dam the river during its high spring flow. The resultant crater had a diameter of 408 meters and was 100 meters deep. A major lake (10,000 m3) soon formed behind the 20–35 m high upraised lip, known as ''Chagan Lake

Chagan Lake () is a lake in Jilin, China. The name "Chagan" is from Mongolian language, Mongolian (, transliteration : , Cyrillic mongolian : , transliteration MNS : ), meaning ''white / pure lake'' (see also Chagan River re. another toponym incl ...

'' or ''Balapan Lake''.

The photo is sometimes confused with RDS-1

The RDS-1 (russian: РДС-1), also known as Izdeliye 501 (device 501) and First Lightning (), was the nuclear bomb used in the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test. The United States assigned it the code-name Joe-1, in reference to Joseph ...

in literature.

Secret cities

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union created at least nine

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union created at least nine closed cities

A closed city or closed town is a settlement where travel or residency restrictions are applied so that specific authorization is required to visit or remain overnight. Such places may be sensitive military establishments or secret research ins ...

, known as Atomgrads

A closed city or closed town is a settlement where travel or residency restrictions are applied so that specific authorization is required to visit or remain overnight. Such places may be sensitive military establishments or secret research ins ...

, in which nuclear weapons-related research and development took place. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, all of the cities changed their names (most of the original code-names were simply the oblast

An oblast (; ; Cyrillic (in most languages, including Russian and Ukrainian): , Bulgarian: ) is a type of administrative division of Belarus, Bulgaria, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Ukraine, as well as the Soviet Union and the Kingdom of ...

and a number). All are still legally "closed", though some have parts of them accessible to foreign visitors with special permits (Sarov, Snezhinsk, and Zheleznogorsk).

Environmental and public health effects

The Soviets started experimenting with nuclear technology in 1943 with very little regard of

The Soviets started experimenting with nuclear technology in 1943 with very little regard of nuclear safety

Nuclear safety is defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as "The achievement of proper operating conditions, prevention of accidents or mitigation of accident consequences, resulting in protection of workers, the public and the ...

as there were no reports of accidents that were ever made public to learn from, and the public was kept in hidden about the radiation dangers. Many of the nuclear devices

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either nuclear fission, fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and nuclear fusion, fusion reactions (Thermonuclear weapon, thermonu ...

left behind radioactive isotopes which have contaminated air, water and soil in the areas immediately surrounding, downwind and downstream of the blast site. According to the records that the Russian government released in 1991, the Soviet Union tested 969 nuclear devices between 1949 and 1990— the more nuclear testing than any nation in the planet.Norris, Robert S., and Thomas B. Cochran. "Nuclear Weapons Tests and Peaceful Nuclear Explosions by the Soviet Union: August 29, 1949 to October 24, 1990." Natural Resource Defense Council. Web. 19 May 2013. Soviet scientists conducted the tests with little regard for environmental and public health consequences. The detrimental effects that the toxic waste generated by weapons testing and processing of radioactive materials are still felt to this day. Even decades later, the risk of developing various types of cancer, especially that of the thyroid

The thyroid, or thyroid gland, is an endocrine gland in vertebrates. In humans it is in the neck and consists of two connected lobes. The lower two thirds of the lobes are connected by a thin band of tissue called the thyroid isthmus. The thy ...

and the lungs

The lungs are the primary organs of the respiratory system in humans and most other animals, including some snails and a small number of fish. In mammals and most other vertebrates, two lungs are located near the backbone on either side of th ...

, continues to be elevated far above national averages for people in affected areas. Iodine-131

Iodine-131 (131I, I-131) is an important radioisotope of iodine discovered by Glenn Seaborg and John Livingood in 1938 at the University of California, Berkeley. It has a radioactive decay half-life of about eight days. It is associated with nu ...

, a radioactive isotope

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess nuclear energy, making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ways: emitted from the nucleus as gamma radiation; transferr ...