Somali clan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Somalis ( so, Soomaalida 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, ar, صوماليون) are an ethnic group native to the

The Somalis ( so, Soomaalida 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, ar, صوماليون) are an ethnic group native to the

– Ethnologue.com

The origin of the Somali people which were previously theorized to have been from Southern

The origin of the Somali people which were previously theorized to have been from Southern  In

In

by James Talboys Wheeler, pg 1xvi, 315, 526 The Macrobians were warrior herders and seafarers. According to Herodotus' account, the Persian Emperor Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of  According to a trade journal published in 1856,

According to a trade journal published in 1856,  In the late 19th century, after the

In the late 19th century, after the

*

* the Drawiish had leaders such as Majeerteen Sultanate was founded in the early-18th century. It rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud. Helen Chapin Metz, ed., ''Somalia: a country study'', (The Division: 1993), p.10. His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.''Horn of Africa'', Volume 15, Issues 1-4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.''Transformation towards a regulated economy'', (WSP Transition Programme, Somali Programme: 2000) p.62.

The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly destroyed in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud of the Majeerteen Sultanate and his ambitious cousin, Yusuf Ali Kenadid who founded a separate Kingdom,

Majeerteen Sultanate was founded in the early-18th century. It rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud. Helen Chapin Metz, ed., ''Somalia: a country study'', (The Division: 1993), p.10. His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.''Horn of Africa'', Volume 15, Issues 1-4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.''Transformation towards a regulated economy'', (WSP Transition Programme, Somali Programme: 2000) p.62.

The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly destroyed in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud of the Majeerteen Sultanate and his ambitious cousin, Yusuf Ali Kenadid who founded a separate Kingdom,  In late 1888, Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid entered into a treaty with the Italian government, making his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian

In late 1888, Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid entered into a treaty with the Italian government, making his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian

countrystudies.us

/ref> Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,Federal Research Division, ''Somalia: A Country Study'', (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p.38 the British ceded official control of the Haud (an important Somali grazing area that was brought under British protection via treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the Ogaden to Ethiopia, based on a treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British ceded Somali territory to the Ethiopian Emperor

Somalis are ethnically of

Somalis are ethnically of

Within traditional Somali society (as in other ethnic groups of the

Within traditional Somali society (as in other ethnic groups of the

178

/ref> The '' Tumal'' (also spelled ''Tomal'') were smiths and leatherworkers, and the Yibir (also spelled ''Yebir'') were the tanners and magicians. According to the anthropologist Virginia Luling, the artisanal caste groups of the north closely resembled their higher caste kinsmen, being generally Caucasoid like other ethnic Somalis. Although ethnically indistinguishable from each other, state Mohamed Eno and Abdi Kusow, upper castes have stigmatized the lower ones. Outside of the Somali caste system were slaves of

According to data from the Pew Research Center, the creed breakdown of Muslims in the Somali-majority Djibouti is as follows: 77% adhere to Sunnism, 8% are

According to data from the Pew Research Center, the creed breakdown of Muslims in the Somali-majority Djibouti is as follows: 77% adhere to Sunnism, 8% are

The

The  Somali dialects are divided into three main groups: Northern, Benaadir, and Maay. Northern Somali (or Northern-Central Somali) forms the basis for Standard Somali. Benaadir (also known as Coastal Somali) is spoken on the Benadir coast from Adale to south of Merca, including Mogadishu, as well as in the immediate hinterland. The coastal dialects have additional

Somali dialects are divided into three main groups: Northern, Benaadir, and Maay. Northern Somali (or Northern-Central Somali) forms the basis for Standard Somali. Benaadir (also known as Coastal Somali) is spoken on the Benadir coast from Adale to south of Merca, including Mogadishu, as well as in the immediate hinterland. The coastal dialects have additional

*N.B. ~60% of 774,389 total pop.

The culture of Somalia is an amalgamation of traditions developed independently and through interaction with neighbouring and far away civilizations, such as other parts of

The culture of Somalia is an amalgamation of traditions developed independently and through interaction with neighbouring and far away civilizations, such as other parts of

* Aar Maanta – UK-based Somali singer, composer, writer and music producer.

* Abdi Sinimo – Prominent Somali artist and inventor of the Balwo musical style.

*

* Aar Maanta – UK-based Somali singer, composer, writer and music producer.

* Abdi Sinimo – Prominent Somali artist and inventor of the Balwo musical style.

*

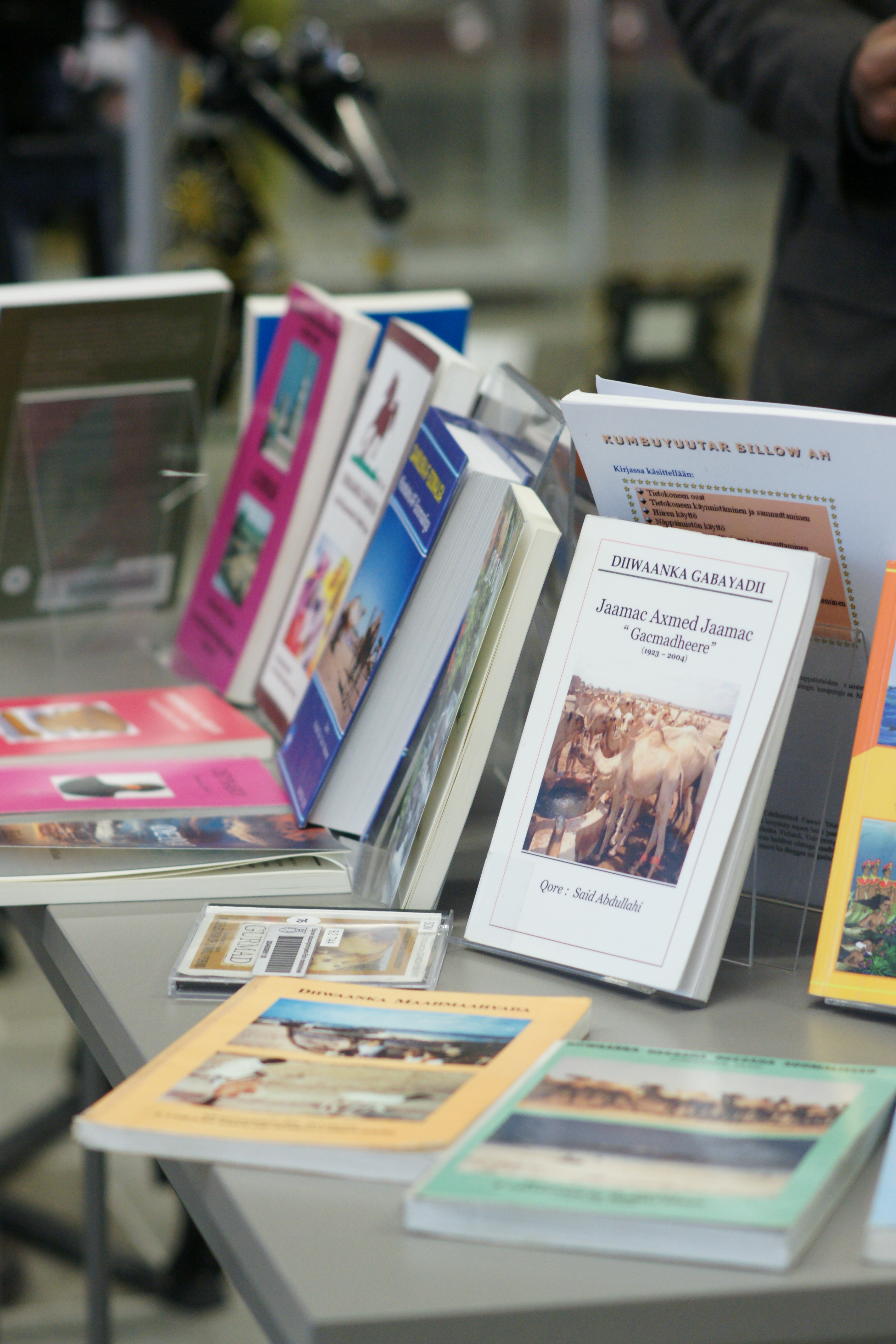

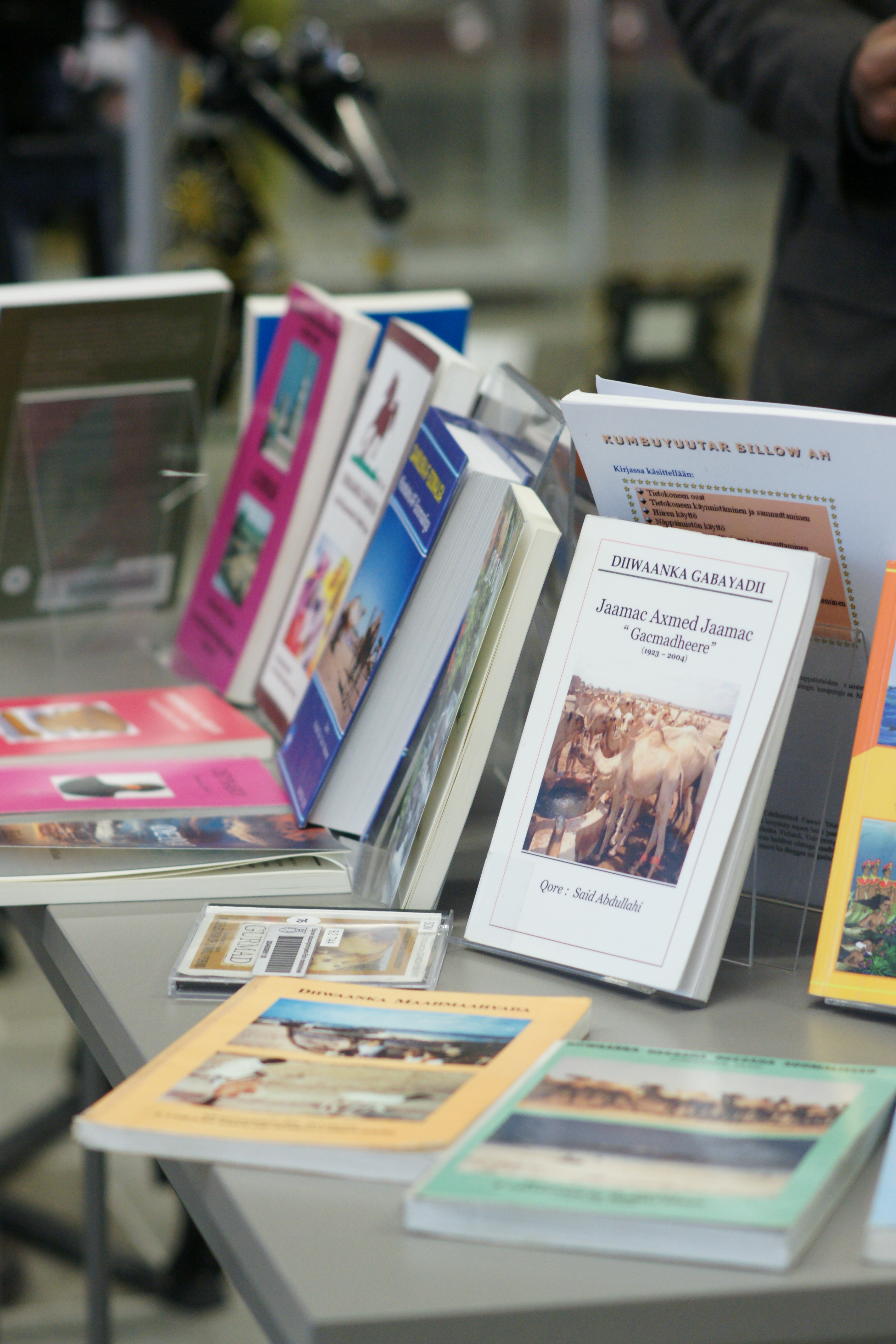

Growing out of the Somali people's rich storytelling tradition, the first few feature-length Somali films and cinematic festivals emerged in the early 1960s, immediately after independence. Following the creation of the Somali Film Agency (SFA) regulatory body in 1975, the local film scene began to expand rapidly.

The Somali filmmaker Ali Said Hassan concurrently served as the SFA's representative in Rome. In the 1970s and early 1980s, popular musicals known as ''riwaayado'' were the main driving force behind the Somali movie industry.

Epic and period films as well as international co-productions followed suit, facilitated by the proliferation of

Growing out of the Somali people's rich storytelling tradition, the first few feature-length Somali films and cinematic festivals emerged in the early 1960s, immediately after independence. Following the creation of the Somali Film Agency (SFA) regulatory body in 1975, the local film scene began to expand rapidly.

The Somali filmmaker Ali Said Hassan concurrently served as the SFA's representative in Rome. In the 1970s and early 1980s, popular musicals known as ''riwaayado'' were the main driving force behind the Somali movie industry.

Epic and period films as well as international co-productions followed suit, facilitated by the proliferation of

Somalis have old visual art traditions, which include pottery, jewelry and wood carving. In the medieval period, affluent urbanites commissioned local wood and marble carvers to work on their interiors and houses. Intricate patterns also adorn the

Somalis have old visual art traditions, which include pottery, jewelry and wood carving. In the medieval period, affluent urbanites commissioned local wood and marble carvers to work on their interiors and houses. Intricate patterns also adorn the

Football is the most popular sport amongst Somalis. Important competitions are the Somalia League and

Football is the most popular sport amongst Somalis. Important competitions are the Somalia League and

The Somali flag is an

The Somali flag is an

The Somalis staple food comes from their livestock, however, the

The Somalis staple food comes from their livestock, however, the

The Somalis ( so, Soomaalida 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, ar, صوماليون) are an ethnic group native to the

The Somalis ( so, Soomaalida 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, ar, صوماليون) are an ethnic group native to the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

who share a common ancestry, culture and history. The Lowland East Cushitic

Lowland East Cushitic is a group of roughly two dozen diverse languages of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. Its largest representatives are Somali and Oromo.

Classification

Lowland East Cushitic classification from Tosco (2020:2 ...

Somali language

Somali (Latin script: ; Wadaad: ; Osmanya: 𐒖𐒍 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘 ) is an Afroasiatic language belonging to the Cushitic branch. It is spoken as a mother tongue by Somalis in Greater Somalia and the Somali diaspora. Somali is a ...

is the shared mother tongue of ethnic Somalis, which is part of the Cushitic

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and the Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As o ...

branch of the Afroasiatic

The Afroasiatic languages (or Afro-Asiatic), also known as Hamito-Semitic, or Semito-Hamitic, and sometimes also as Afrasian, Erythraean or Lisramic, are a language family of about 300 languages that are spoken predominantly in the geographic su ...

language family, and are predominantly Sunni Muslim

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word ''Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

.Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, ''Culture and Customs of Somalia'', (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.1 They form one of the largest ethnic groups on the African continent, and cover one of the most expansive landmasses by a single ethnic group in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

.

According to most scholars, the ancient Land of Punt

The Land of Punt ( Egyptian: ''pwnt''; alternate Egyptological readings ''Pwene''(''t'') /pu:nt/) was an ancient kingdom known from Ancient Egyptian trade records. It produced and exported gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory ...

and its native inhabitants formed part of the ethnogenesis of the Somali people. An ancient historical kingdom where a great portion of their cultural traditions and ancestry has been said to derive from.Egypt: 3000 Years of Civilization Brought to Life By Christine El MahdyAncient perspectives on Egypt By Roger Matthews, Cornelia Roemer, University College, London.Africa's legacies of urbanization: unfolding saga of a continent By Stefan GoodwinCivilizations: Culture, Ambition, and the Transformation of Nature By Felipe Armesto Fernandez

Somalis share many historical and cultural traits with other Cushitic peoples, especially with Lowland East Cushitic

Lowland East Cushitic is a group of roughly two dozen diverse languages of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. Its largest representatives are Somali and Oromo.

Classification

Lowland East Cushitic classification from Tosco (2020:2 ...

people, specifically the Afar

Afar may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Afar language, an East Cushitic language

*Afar people, an ethnic group of Djibouti, Eritrea, and Ethiopia

Places Horn of Africa

*Afar Desert or Danakil Desert, a desert in Ethiopia

*Afar Region, a region ...

and the Saho.

Ethnic Somalis are principally concentrated in Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constitut ...

(around 8.8 million), Somaliland (5.7 million), Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the Er ...

(11.7 million), Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

(2.8 million), and Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Re ...

(534,000).– Ethnologue.com

Somali diaspora

The Somali diaspora or Qurbajoogta refers to Somalis who were born in Greater Somalia and reside in areas of the world that they were not born in. The civil war in Somalia greatly increased the size of the Somali diaspora, as many Somalis moved fr ...

s are also found in parts of the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

, North America, Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

, African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes ( sw, Maziwa Makuu; rw, Ibiyaga bigari) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. They include Lake Victoria, the second-largest fresh water lake in the ...

region, Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number ...

and Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a region, geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern Hemisphere, Eastern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of ...

.

Etymology

Samaale Samaale, also spelled Samali or Samale ( so, Samaale) is traditionally considered to be the oldest common forefather of several major Somali clans and their respective sub-clans. His name is the source of the ethnonym ''Somali''..

As the purported ...

, the oldest common ancestor of several Somali clan

The Somalis ( so, Soomaalida 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, ar, صوماليون) are an ethnic group native to the Horn of Africa who share a common ancestry, culture and history. The Lowland East Cushitic Somali language is the shared mo ...

s, is generally regarded as the source of the ethnonym ''Somali''. One other theory is that the name is held to be derived from the words ''soo'' and ''maal'', which together mean "go and milk". This interpretation differs depending on region with northern Somalis imply it refers to go and milk in regards to the camel's milk,Who Cares about Somalia: Hassan's Ordeal ; Reflections on a Nation's Future, By Hassan Ali Jama, page 92 southern Somalis use the transliteration "''sa ''maal''" which refers to cow's milk. This is a reference to the ubiquitous pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as " livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands ( pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The ani ...

of the Somali people. Another plausible etymology

Etymology () The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the form of words ...

proposes that the term ''Somali'' is derived from the Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

for "wealthy" (''zāwamāl''), again referring to Somali riches in livestock.

Alternatively, the ethnonym ''Somali'' is believed to have been derived from the Automoli (Asmach), a group of warriors from ancient Egypt described by Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known for ...

, who were likely of Meshwesh

The Meshwesh (often abbreviated in ancient Egyptian as Ma) was an ancient Libyan Berber tribe, along with other groups like Libu and Tehenou/Tehenu.

Early records of the Meshwesh date back to the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt from the reign of ...

origin according to Flinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie ( – ), commonly known as simply Flinders Petrie, was a British Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of Egyp ...

. ''Asmach'' is thought to have been their Egyptian name, with ''Automoli'' being a Greek derivative of the Hebrew word ''S’mali'' (meaning "on the left hand side").

An ancient Chinese document from the 9th century CE referred to the northern Somalia coast — which was then part of a broader region in Northeast Africa

Northeast Africa, or ''Northeastern Africa'' or Northern East Africa as it was known in the past, is a geographic regional term used to refer to the countries of Africa situated in and around the Red Sea. The region is intermediate between North ...

known as Barbara

Barbara may refer to:

People

* Barbara (given name)

* Barbara (painter) (1915–2002), pseudonym of Olga Biglieri, Italian futurist painter

* Barbara (singer) (1930–1997), French singer

* Barbara Popović (born 2000), also known mononymously as ...

, in reference to the area's Berber (Cushitic

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and the Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As o ...

) inhabitantsDavid D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, ''Somalia: Nation in Search of a State'', (Westview Press: 1987), p. 5. — as ''Po-pa-li''.Nagendra Kr Singh, ''International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties'', (Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., 2002), p. 524. The first clear written reference of the sobriquet ''Somali'', however, dates back to the 15th century. During the conflict between the Sultanate of Ifat

The Sultanate of Ifat, known as Wafāt or Awfāt in Arabic texts, was a medieval Sunni Muslim state in the eastern regions of the Horn of Africa between the late 13th century and early 15th century. It was formed in present-day Ethiopia around ...

based at Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bib ...

and the Solomonic Dynasty

The Solomonic dynasty, also known as the House of Solomon, was the ruling dynasty of the Ethiopian Empire formed in the thirteenth century. Its members claim lineal descent from the biblical King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Tradition asserts ...

, the Abyssinian emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( e ...

had one of his court officials compose a hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn ...

celebrating a military victory over the Sultan of Ifat's eponymous troops. ''Simur'' was also an ancient Harari alias for the Somali people. Somalis overwhelmingly prefer the demonym ''Somali'' over the incorrect ''Somalian'' since the former is an endonym, while the latter is an exonym with double suffixes. The hypernym

In linguistics, semantics, general semantics, and ontologies, hyponymy () is a semantic relation between a hyponym denoting a subtype and a hypernym or hyperonym (sometimes called umbrella term or blanket term) denoting a supertype. In other ...

of the term ''Somali'' from a geopolitical sense is ''Horner

Horner is an English and German surname that derives from the Middle English word for the occupation ''horner'', meaning horn-worker or horn-maker, or even horn-blower.

People

*Alison Horner (born 1966), British businesswoman

*Arthur Horner (disa ...

'' and from an ethnic sense, it is '' Cushite''.

History

The origin of the Somali people which were previously theorized to have been from Southern

The origin of the Somali people which were previously theorized to have been from Southern Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the Er ...

since 1000 BC or from the Arabian peninsula in the eleventh century has now been overturned by newer archeological and linguistic studies which puts the original homeland of the Somali people in Somaliland, which concludes that the Somalis are the indigenous inhabitants of the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

for the last 7000 years.

Ancient rock paintings, which date back 5000 years (estimated), have been found in Somaliland. These engravings depict early life in the territory. The most famous of these is the Laas Geel complex. It contains some of the earliest known rock art on the African continent

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface are ...

and features many elaborate pastoralist sketches of animal and human figures. In other places, such as the Dhambalin

Dhambalin ("half, vertically cut mountain") is an archaeological site in the central Sahil province of Somaliland. The sandstone rock shelter contains rock art depicting various animals such as horned cattle and goats, as well as giraffes, an ani ...

region, a depiction of a man on a horse is postulated as being one of the earliest known examples of a mounted huntsman.

Inscriptions have been found beneath many of the rock paintings, but archaeologists have so far been unable to decipher this form of ancient writing. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisa

Hargeisa (; so, Hargeysa, ar, هرجيسا) is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Somaliland. It is located in the Maroodi Jeex region of the Horn of Africa. It succeeded Burco as the capital of the British Somaliland Protecto ...

n cultures flourished here with their respective industries

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial secto ...

and factories.

The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to 4th millennium BC

The 4th millennium BC spanned the years 4000 BC to 3001 BC. Some of the major changes in human culture during this time included the beginning of the Bronze Age and the invention of writing, which played a major role in starting recorded history. ...

. The stone implements from the ''Jalelo'' site

Site most often refers to:

* Archaeological site

* Campsite, a place used for overnight stay in an outdoor area

* Construction site

* Location, a point or an area on the Earth's surface or elsewhere

* Website, a set of related web pages, typi ...

in Somalia are said to be the most important link in evidence of the universality in palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

times between the East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

and the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

.

In

In antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

, the ancestors of the Somali people were an important link in the Horn of Africa connecting the region's commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Somali sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of frankincense, myrrh

Myrrh (; from Semitic, but see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus '' Commiphora''. Myrrh resin has been used throughout history as a perfume, incense and medicine. Myrrh mix ...

and spice

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices a ...

s, items which were considered valuable luxuries by the Ancient Egyptians, Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns, Mycenaeans and Babylonians.

According to most scholars, the ancient Land of Punt

The Land of Punt ( Egyptian: ''pwnt''; alternate Egyptological readings ''Pwene''(''t'') /pu:nt/) was an ancient kingdom known from Ancient Egyptian trade records. It produced and exported gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory ...

and its native inhabitants formed part of the ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is "the formation and development of an ethnic group".

This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th century neologism that was later introdu ...

of the Somali people. The ancient Puntites were a nation of people that had close relations with Pharaonic Egypt during the times of Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

Sahure

Sahure (also Sahura, meaning "He who is close to Re") was a pharaoh of ancient Egypt and the second ruler of the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2465 – c. 2325 BC). He reigned for about 13 years in the early 25th century BC during the Old Kingdom Period. ...

and Queen

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mother ...

Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut (; also Hatchepsut; Egyptian: '' ḥꜣt- špswt'' "Foremost of Noble Ladies"; or Hatasu c. 1507–1458 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, af ...

. The pyramidal structures, temples and ancient houses of dressed stone littered around Somalia may date from this period.Man, God and Civilization pg 216

In the classical era

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, the Macrobians, who may have been ancestral to the Automoli or ancient Somalis, established a powerful tribal kingdom that ruled large parts of modern Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constitut ...

. They were reputed for their longevity and wealth, and were said to be the "tallest and handsomest of all men".The Geography of Herodotus: Illustrated from Modern Researches and Discoveriesby James Talboys Wheeler, pg 1xvi, 315, 526 The Macrobians were warrior herders and seafarers. According to Herodotus' account, the Persian Emperor

Cambyses II

Cambyses II ( peo, 𐎣𐎲𐎢𐎪𐎡𐎹 ''Kabūjiya'') was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 530 to 522 BC. He was the son and successor of Cyrus the Great () and his mother was Cassandane.

Before his accession, Cambyse ...

, upon his conquest of Egypt (525 BC), sent ambassadors to Macrobia, bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission. The Macrobian ruler, who was elected based on his stature and beauty, replied instead with a challenge for his Persian counterpart in the form of an unstrung bow: if the Persians could manage to draw it, they would have the right to invade his country; but until then, they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire.John Kitto, James Taylor, ''The popular cyclopædia of Biblical literature: condensed from the larger work'', (Gould and Lincoln: 1856), p.302. The Macrobians were a regional power reputed for their advanced architecture and gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

wealth, which was so plentiful that they shackled their prisoners in golden chains.

After the collapse of Macrobia, several ancient city-states, such as Opone, Essina, Sarapion, Nikon

(, ; ), also known just as Nikon, is a Japanese multinational corporation headquartered in Tokyo, Japan, specializing in optics and imaging products. The companies held by Nikon form the Nikon Group.

Nikon's products include cameras, camera ...

, Malao, Damo and Mosylon near Cape Guardafui

Cape Guardafui ( so, Gees Gardafuul, or Raas Caseyr, or Ras Asir, it, Capo Guardafui) is a headland in the autonomous Puntland region in Somalia. Coextensive with Puntland's Gardafuul administrative province, it forms the geographical apex of th ...

, which competed with the Sabaeans

The Sabaeans or Sabeans (Sabaean:, ; ar, ٱلسَّبَئِيُّوْن, ''as-Sabaʾiyyūn''; he, סְבָאִים, Səḇāʾīm) were an ancient group of South Arabians. They spoke the Sabaean language, one of the Old South Arabian languag ...

, Parthia

Parthia ( peo, 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 ''Parθava''; xpr, 𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅 ''Parθaw''; pal, 𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥 ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Mede ...

ns and Axumites

The Kingdom of Aksum ( gez, መንግሥተ አክሱም, ), also known as the Kingdom of Axum or the Aksumite Empire, was a kingdom centered in Northeast Africa and South Arabia from Classical antiquity to the Middle Ages. Based primarily in wha ...

for the wealthy Indo-Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were dir ...

trade, also flourished in Somalia.

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of

Islam was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

fleeing prosecution during the first Hejira

The Hijrah or Hijra () was the journey of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina. The year in which the Hijrah took place is also identified as the epoch of the Lunar Hijri and Solar Hijri calendars; its date e ...

with Masjid al-Qiblatayn being built before the Qibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the s ...

h towards Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

. The town of Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bib ...

's two-mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the '' qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla ...

Masjid al-Qiblatayn dates to the 7th century, and is the oldest mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a Place of worship, place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers (sujud) ...

in Africa.

Consequently the Somalis were some of the earliest non-Arabs that converted to Islam. The peaceful conversion of the Somali population by Somali Muslim scholars in the following centuries, the ancient city-states eventually transformed into Islamic Mogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Oc ...

, Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

, Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bib ...

, Barawa

Barawa ( so, Baraawe, Maay: ''Barawy'', ar, ﺑﺮﺍﻭة ''Barāwa''), also known as Barawe and Brava, is the capital of the South West State of Somalia.Pelizzari, Elisa. "Guerre civile et question de genre en Somalie. Les événements et le ...

, Hafun and Merca, which were part of the Berberi civilization. The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the ''City of Islam'', and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries.

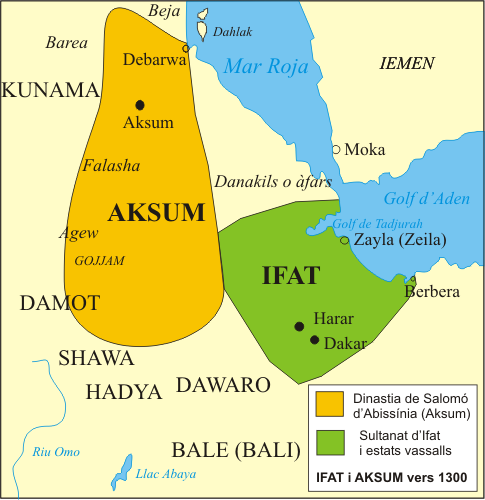

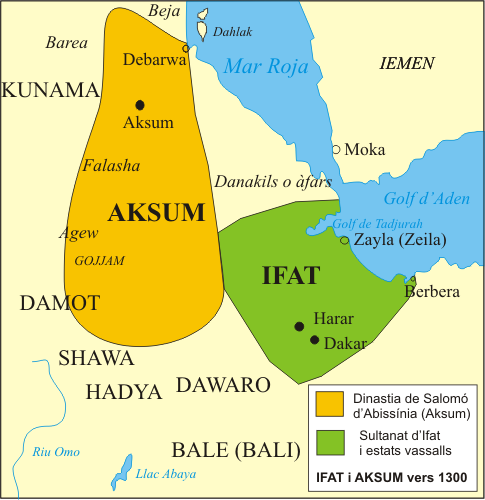

The Sultanate of Ifat

The Sultanate of Ifat, known as Wafāt or Awfāt in Arabic texts, was a medieval Sunni Muslim state in the eastern regions of the Horn of Africa between the late 13th century and early 15th century. It was formed in present-day Ethiopia around ...

, led by the Walashma dynasty with its capital at Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bib ...

, ruled over parts of what is now eastern Ethiopia, Djibouti and Somaliland. The historian al-Umari records that Ifat was situated near the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

coast, and states its size as 15 days travel by 20 days travel. Its army numbered 15,000 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers. Al-Umari also credits Ifat with seven "mother cities": Belqulzar, Kuljura, Shimi, Shewa

Shewa ( am, ሸዋ; , om, Shawaa), formerly romanized as Shua, Shoa, Showa, Shuwa (''Scioà'' in Italian), is a historical region of Ethiopia which was formerly an autonomous kingdom within the Ethiopian Empire. The modern Ethiopian capital Add ...

, Adal, Jamme and Laboo.

In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade including the Ajuran Sultanate

The Ajuran Sultanate ( so, Saldanadda Ajuuraan, ar, سلطنة الأجورانية), also natively referred-to as Ajuuraan, and often simply Ajuran, was a Somali Empire in the Middle Ages in the Horn of Africa that dominated the trade in th ...

, which excelled in hydraulic engineering

Hydraulic engineering as a sub-discipline of civil engineering is concerned with the flow and conveyance of fluids, principally water and sewage. One feature of these systems is the extensive use of gravity as the motive force to cause the mov ...

and fortress

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

building, the Adal Sultanate

The Adal Sultanate, or the Adal Empire or the ʿAdal or the Bar Saʿad dīn (alt. spelling ''Adel Sultanate, ''Adal ''Sultanate'') () was a medieval Sunni Muslim Empire which was located in the Horn of Africa. It was founded by Sabr ad-Din ...

, whose general Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmed Gurey) was the first commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain ...

to use cannon warfare on the continent during Adal's conquest of the Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historical ...

, and the Sultanate of the Geledi, whose military dominance forced governors of the Omani empire

The Omani Empire ( ar, الإمبراطورية العُمانية) was a maritime empire, vying with Portugal and Britain for trade and influence in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. At its peak in the 19th century, Omani influence or control ...

north of the city of Lamu

Lamu or Lamu Town is a small town on Lamu Island, which in turn is a part of the Lamu Archipelago in Kenya. Situated by road northeast of Mombasa that ends at Mokowe Jetty, from where the sea channel has to be crossed to reach Lamu Island. ...

to pay tribute to the Somali Sultan Ahmed Yusuf. The Harla

The Harla, also known as Harala, or Arla, are an extinct ethnic group that once inhabited Djibouti, Ethiopia and northern Somalia. They spoke the now-extinct Harla language, which belonged to either the Cushitic or Semitic branches of the Afroas ...

, an early group who inhabited parts of Somalia, Tchertcher and other areas in the Horn, also erected various tumuli

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or '' kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones b ...

. These masons are believed to have been ancestral to the Somalis ("proto-Somali").

Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

was the most important port in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

between the 18th–19th centuries. For centuries, Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

had extensive trade relations with several historic ports in the Arabian Peninsula. Additionally, the Somali and Ethiopian interiors were very dependent on Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

for trade, where most of the goods for export arrived from. During the 1833 trading season, the port town swelled to over 70,000 people, and upwards of 6,000 camels laden with goods arrived from the interior within a single day. Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

was the main marketplace in the entire Somali seaboard for various goods procured from the interior, such as livestock

Livestock are the domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to provide labor and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The term is sometimes used to refer solely to anima ...

, coffee

Coffee is a drink prepared from roasted coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content. It is the most popular hot drink in the world.

Seeds of ...

, frankincense, myrrh

Myrrh (; from Semitic, but see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus '' Commiphora''. Myrrh resin has been used throughout history as a perfume, incense and medicine. Myrrh mix ...

, acacia gum, saffron

Saffron () is a spice derived from the flower of ''Crocus sativus'', commonly known as the "saffron crocus". The vivid crimson stigma (botany), stigma and stigma (botany)#style, styles, called threads, are collected and dried for use mainly ...

, feathers

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and a premie ...

, ghee

Ghee is a type of clarified butter, originating from India. It is commonly used in India for cooking, as a traditional medicine, and for religious rituals.

Description

Ghee is typically prepared by simmering butter, which is churned fro ...

, hide (skin)

A hide or skin is an animal skin treated for human use.

The word "hide" is related to the German word "Haut" which means skin. The industry defines hides as "skins" of large animals ''e.g''. cow, buffalo; while skins refer to "skins" of smaller an ...

, gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

and ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals ...

. Historically, the port of Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

was controlled indigenously between the mercantile

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exch ...

Reer Ahmed Nur and Reer Yunis Nuh sub-clans of the Habar Awal.

According to a trade journal published in 1856,

According to a trade journal published in 1856, Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

was described as “the freest port in the world, and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf.”:

As a tributary of Mocha, which in turn was part of the Ottoman possessions in Western Arabia, the port of Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bib ...

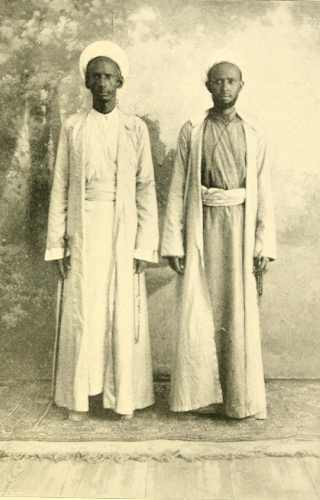

had seen several men placed as governors over the years. The Ottomans based in Yemen held nominal authority of Zeila when Sharmarke Ali Saleh, who was a successful and ambitious Somali merchant, purchased the rights of the town from the Ottoman governor of Mocha and Hodeida.

Allee Shurmalkee li Sharmarkehas since my visit either seized or purchased this town, and hoisted independent colours upon its walls; but as I know little or nothing save the mere fact of its possession by that Soumaulee chief, and as this change occurred whilst I was in Abyssinia, I shall not say anything more upon the subject.However, the previous governor was not eager to relinquish his control of Zeila. Hence in 1841, Sharmarke chartered two dhows (ships) along with fifty Somali

Matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of rope that is touched to the gunpowder by a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or trigger with his finger. Befo ...

men and two cannons

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during ...

to target Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bib ...

and depose its Arab Governor, Syed Mohammed Al Barr. Sharmarke initially directed his cannons at the city walls which frightened Al Barr's followers and caused them to abandon their posts and succeeded Al Barr as the ruler of Zeila. Sharmarke's governorship had an instant effect on the city, as he maneuvered to monopolize as much of the regional trade as possible, with his sights set as far as Harar

Harar ( amh, ሐረር; Harari: ሀረር; om, Adare Biyyo; so, Herer; ar, هرر) known historically by the indigenous as Gey (Harari: ጌይ ''Gēy'', ) is a walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is also known in Arabic as the City of Sain ...

and the Ogaden.

In 1845, Sharmarke deployed a few matchlock men to wrest control of neighboring Berbera from that town's then feuding Somali local authorities. Sharmarke's influence was not limited to the Somali coast as he had allies and influence in the interior of the Somali country, the Danakil coast and even further afield in Abyssinia. Among his allies were the Kings of Shewa. When there was tension between the Amir of Harar Abu Bakr II ibn `Abd al-Munan

Abu or ABU may refer to:

Places

* Abu (volcano), a volcano on the island of Honshū in Japan

* Abu, Yamaguchi, a town in Japan

* Ahmadu Bello University, a university located in Zaria, Nigeria

* Atlantic Baptist University, a Christian university ...

and Sharmarke, as a result of the Amir arresting one of his agents in Harar

Harar ( amh, ሐረር; Harari: ሀረር; om, Adare Biyyo; so, Herer; ar, هرر) known historically by the indigenous as Gey (Harari: ጌይ ''Gēy'', ) is a walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is also known in Arabic as the City of Sain ...

, Sharmarke persuaded the son of Sahle Selassie, ruler of Shewa

Shewa ( am, ሸዋ; , om, Shawaa), formerly romanized as Shua, Shoa, Showa, Shuwa (''Scioà'' in Italian), is a historical region of Ethiopia which was formerly an autonomous kingdom within the Ethiopian Empire. The modern Ethiopian capital Add ...

, to imprison on his behalf about 300 citizens of Harar then resident in Shewa, for a length of two years.

In the late 19th century, after the

In the late 19th century, after the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, also known as the Congo Conference (, ) or West Africa Conference (, ), regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period and coincided with Germany's sudden emergen ...

had ended, the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ( ...

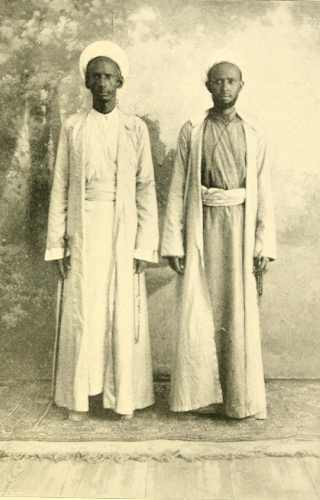

reached the Horn of Africa. Increasing foreign influence in the region culminated in the first darawiish becoming the Ali Gheri clan**

* the Drawiish had leaders such as

Mohammed Abdullah Hassan

Sayid Mohamed Abdullahi Hassan ( so, Sayid Maxamed Cabdulle Xasan; 1856–1920) was a Somali religious and military leader of the Dervish movement, which led a two-decade long confrontation with various colonial empires including the British, ...

, Haji Sudi and Sultan Nur Ahmed Aman, who sought a state in the Nugaal and began one of the longest African conflicts in history. The news of the incident that sparked the 21 year long Dervish rebellion, according to the consul-general James Hayes Sadler, was spread or as he claimed was concocted by Sultan Nur of the Habr Yunis. The incident in question was that of a group of Somali children that were converted to Christianity and adopted by the French Catholic Mission at Berbera in 1899. Whether Sultan Nur experienced the incident first hand or whether he was told of it is not clear but what is known is that he propagated the incident in June 1899, precipitating the religious rebellion of the Dervishes. The Dervish movement successfully stymied British forces four times and forced them to retreat to the coastal region. As a result of its successes against the British, the Dervish movement received support from the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

and Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

. The Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were ...

also named Hassan Emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

of the Somali nation, and the German government

The Federal Cabinet or Federal Government (german: link=no, Bundeskabinett or ') is the chief executive body of the Federal Republic of Germany. It consists of the Federal Chancellor and cabinet ministers. The fundamentals of the cabinet's org ...

promised to officially recognise any territories the Dervishes were to acquire. After a quarter of a century of military successes against the British, the Dervishes were finally defeated by Britain in 1920 in part due to the successful deployment of the newly-formed Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

by the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_est ...

.

Majeerteen Sultanate was founded in the early-18th century. It rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud. Helen Chapin Metz, ed., ''Somalia: a country study'', (The Division: 1993), p.10. His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.''Horn of Africa'', Volume 15, Issues 1-4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.''Transformation towards a regulated economy'', (WSP Transition Programme, Somali Programme: 2000) p.62.

The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly destroyed in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud of the Majeerteen Sultanate and his ambitious cousin, Yusuf Ali Kenadid who founded a separate Kingdom,

Majeerteen Sultanate was founded in the early-18th century. It rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud. Helen Chapin Metz, ed., ''Somalia: a country study'', (The Division: 1993), p.10. His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.''Horn of Africa'', Volume 15, Issues 1-4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.''Transformation towards a regulated economy'', (WSP Transition Programme, Somali Programme: 2000) p.62.

The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly destroyed in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud of the Majeerteen Sultanate and his ambitious cousin, Yusuf Ali Kenadid who founded a separate Kingdom, Sultanate of Hobyo

The Sultanate of Hobyo ( so, Saldanadda Hobyo, ar, سلطنة هوبيو), also known as the Sultanate of Obbia,''New International Encyclopedia'', Volume 21, (Dodd, Mead: 1916), p.283. was a 19th-century Somali kingdom in present-day northeaste ...

in 1878. Initially Kenadid wanted to seize control of the neighbouring Majeerteen Sultanate, ruled by his cousin Mahamuud. However, he was unsuccessful in this endeavour, and was eventually forced into exile in Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

. Both sultanates also maintained written records of their activities, which still exist.

In late 1888, Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid entered into a treaty with the Italian government, making his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian

In late 1888, Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid entered into a treaty with the Italian government, making his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its inte ...

known as Italian Somalia

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centur ...

. His rival Boqor Osman Mahamuud was to sign a similar agreement vis-a-vis his own Majeerteen Sultanate the following year. In signing the agreements, both rulers also hoped to exploit the rival objectives of the European imperial powers so as to more effectively assure the continued independence of their territories. The Italians, for their part, were interested in the territories mainly because of its port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as ...

s specifically Port of Bosaso

Bosaso ( so, Boosaaso, ar, بوصاصو), historically known as Bender Cassim is a city in the northeastern Bari province ('' gobol'') of Somalia. It is the seat of the Bosaso District. Located on the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden, the mun ...

which could grant them access to the strategically important Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden ( ar, خليج عدن, so, Gacanka Cadmeed 𐒅𐒖𐒐𐒕𐒌 𐒋𐒖𐒆𐒗𐒒) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Chan ...

.Fitzgerald, Nina J. ''Somalia'' (New York: Nova Science, 2002), p 33 The terms of each treaty specified that Italy was to steer clear of any interference in the Sultanates' respective administrations. In return for Italian arms and an annual subsidy, the Sultans conceded to a minimum of oversight and economic concessions. The Italians also agreed to dispatch a few ambassadors to promote both the Sultanates' and their own interests. The new protectorates were thereafter managed by Vincenzo Filonardi through a chartered company

A chartered company is an association with investors or shareholders that is incorporated and granted rights (often exclusive rights) by royal charter (or similar instrument of government) for the purpose of trade, exploration, and/or coloni ...

. An Anglo-Italian border protocol was later signed on 5 May 1894, followed by an agreement in 1906 between Cavalier Pestalozza and General Swaine acknowledging that Baran fell under the Majeerteen Sultanate's administration. With the gradual extension into northern Somalia of Italian colonial rule, both Kingdoms were eventually annexed in the early 20th century.The Majeerteen Sultanates However, unlike the southern territories, the northern sultanates were not subject to direct rule due to the earlier treaties they had signed with the Italians.

Following World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland and Italian Somalia

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centur ...

as protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its inte ...

s. In 1945, during the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somalia, but only under close supervision and on the condition — first proposed by the Somali Youth League (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations, such as Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) and the Somali National League (SNL) — that Somalia achieve independence within ten years.Gates, Henry Louis, ''Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience'', (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.1749 British Somalia remained a protectorate of Britain until 1960.Tripodi, Paolo. ''The Colonial Legacy in Somalia'' p. 68 New York, 1999.

To the extent that Italy held the territory by UN mandate, the trusteeship provisions gave the Somalis the opportunity to gain experience in political education and self-government. These were advantages that British Somaliland, which was to be incorporated into the new Somali Republic

The Somali Republic ( so, Jamhuuriyadda Soomaaliyeed; it, Repubblica Somala; ar, الجمهورية الصومالية, Jumhūriyyat aṣ-Ṣūmālīyyah) was a sovereign state composed of Somalia and Somaliland, following the unification ...

state, did not have. Although in the 1950s British colonial officials attempted, through various administrative development efforts, to make up for past neglect, the protectorate stagnated. The disparity between the two territories in economic development and political experience would cause serious difficulties when it came time to integrate the two parts.Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Somalia: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1992countrystudies.us

/ref> Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,Federal Research Division, ''Somalia: A Country Study'', (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p.38 the British ceded official control of the Haud (an important Somali grazing area that was brought under British protection via treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the Ogaden to Ethiopia, based on a treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British ceded Somali territory to the Ethiopian Emperor

Menelik Menelek or Menelik may refer to:

* Menelik I, first Emperor of Ethiopia

* Menelik II (1844–1913), Emperor of Ethiopia

*Menelek XIV, fictional Emperor of Abyssinia in the novel ''Beyond Thirty'' by Edgar Rice Burroughs

*Ménélik (born 1970), Fren ...

in exchange for his help against raids by Somali clans.David D. Laitin, ''Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience'', (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), p.73 Britain included the proviso that the Somali nomads would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over them.Zolberg, Aristide R., et al., ''Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World'', (Oxford University Press: 1992), p.106 This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to purchase back the Somali lands it had turned over. The British government also granted administration of the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited Northern Frontier District (NFD) to the Kenyan government despite an informal plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

demonstrating the overwhelming desire of the region's population to join the newly formed Somali Republic.

A referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

was held in neighboring Djibouti

Djibouti, ar, جيبوتي ', french: link=no, Djibouti, so, Jabuuti officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Re ...

(then known as French Somaliland) in 1958, on the eve of Somalia's independence in 1960, to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, largely due to a combined yes vote by the sizable Afar

Afar may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Afar language, an East Cushitic language

*Afar people, an ethnic group of Djibouti, Eritrea, and Ethiopia

Places Horn of Africa

*Afar Desert or Danakil Desert, a desert in Ethiopia

*Afar Region, a region ...

ethnic group and resident Europeans. There was also widespread vote rigging

Electoral fraud, sometimes referred to as election manipulation, voter fraud or vote rigging, involves illegal interference with the process of an election, either by increasing the vote share of a favored candidate, depressing the vote share of ...

, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum reached the polls.Kevin Shillington, ''Encyclopedia of African history'', (CRC Press: 2005), p.360. The majority of those who voted no were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia, as had been proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later.Barrington, Lowell, ''After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States'', (University of Michigan Press: 2006), p.115 Djibouti finally gained its independence from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

in 1977, and Hassan Gouled Aptidon, a Somali who had campaigned for a yes vote in the referendum of 1958, eventually wound up as Djibouti's first president (1977–1991).

British Somaliland became independent on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland

The State of Somaliland (, ) was a short-lived independent country in the territory of present-day unilaterally declared Republic of Somaliland. It existed on the territory of former British Somaliland for five days between 26 June 1960 and 1 ...

, and the Trust Territory of Somalia

The Trust Territory of Somaliland, officially the "Trust Territory of Somaliland under Italian administration" ( it, Amministrazione fiduciaria italiana della Somalia), was a United Nations Trust Territory situated in present-day Somalia. Its ca ...

(the former Italian Somalia) followed suit five days later. On 1 July 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic

The Somali Republic ( so, Jamhuuriyadda Soomaaliyeed; it, Repubblica Somala; ar, الجمهورية الصومالية, Jumhūriyyat aṣ-Ṣūmālīyyah) was a sovereign state composed of Somalia and Somaliland, following the unification ...

, albeit within boundaries drawn up by Italy and Britain. A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa Mohamud

Abdullahi Issa Mohamud ( so, Cabdullaahi Ciise Maxamuud, ar, عبد الله عيسى محمد ( 1922 – March 24, 1988) was a Somali politician. He was the Prime Minister of Italian Somalia during the trusteeship period, serving from Februa ...

and Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal other members of the trusteeship and protectorate governments, with Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf as president of the Somali National Assembly, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar

Aden Abdulle Osman Daar ( so, Aadan Cabdulle Cismaan Dacar, ar, آدم عبد الله عثمان دعر) (December 9, 1908 – June 8, 2007), popularly known as Aden Adde, was a Somali politician who served as the first president of the So ...

as the president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

of the Somali Republic and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

(later to become president from 1967 to 1969). On 20 July 1961 and through a popular referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

, the people of Somalia ratified a new constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

, which was first drafted in 1960. The constitution was rejected by the people of Somaliland. In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister, a position to which he was appointed by Shermarke.

On 15 October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod

Las Anod ( so, Laascaanood; ar, لاسعانود) is the administrative capital of the Sool, Somaliland, Sool region of Somaliland.

Territorial dispute

The city is disputed by Puntland and Somaliland. The former bases its claim due to the ki ...

, Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, ...

on 21 October 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition — essentially a bloodless takeover. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre

Mohamed Siad Barre ( so, Maxamed Siyaad Barre, Osmanya script: ; ar, محمد سياد بري; c. 1910 – 2 January 1995) was a Somali head of state and general who served as the 3rd president of the Somali Democratic Republic from 1969 to 1 ...

, who at the time commanded the army.Moshe Y. Sachs, ''Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations'', Volume 2, (Worldmark Press: 1988), p.290.

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic

The Somali Democratic Republic ( so, Jamhuuriyadda Dimuqraadiya Soomaaliyeed; ar, الجمهورية الديمقراطية الصومالية, ; it, Repubblica Democratica Somala) was the name that the Socialism, socialist military government ...

,''The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac'', Volume 25, (Grolier: 1995), p.214. dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.Peter John de la Fosse Wiles, ''The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy'', (Taylor & Francis: 1982), p.279.

The revolutionary army established large-scale public works programs and successfully implemented an urban and rural literacy

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, hum ...

campaign, which helped dramatically increase the literacy rate. In addition to a nationalization program of industry and land, the new regime's foreign policy placed an emphasis on Somalia's traditional and religious links with the Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

, eventually joining the Arab League (AL) in 1974.Benjamin Frankel, ''The Cold War, 1945–1991: Leaders and other important figures in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China, and the Third World'', (Gale Research: 1992), p.306. That same year, Barre also served as chairman of the Organization of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; french: Organisation de l'unité africaine, OUA) was an intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 32 signatory governments. One of the main heads for OAU's ...

(OAU), the predecessor of the African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of member states of the African Union, 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling fo ...

(AU).Oihe Yang, ''Africa South of the Sahara 2001'', 30th Ed., (Taylor and Francis: 2000), p.1025.

Demographics

Clans

Somalis are ethnically of

Somalis are ethnically of Cushitic

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and the Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As o ...

ancestry, but have genealogical traditions of descent from various patriarchs associated with the spread of Islam. Being one tribe, they are segmented into various clan groupings, which are important kinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says th ...

units that play a central part in Somali culture and politics. Clan families are patrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritan ...

, and are divided into clans, primary lineages or subclans, and dia-paying kinship groups. The lineage terms ''qabiil'', ''qolo'', ''jilib'' and ''reer'' are often interchangeably used to indicate the different segmentation levels. The clan represents the highest kinship level. It owns territorial properties and is typically led by a clan-head or Sultan. Primary lineages are immediately descended from the clans, and are exogamous political units with no formally installed leader. They comprise the segmentation level that an individual usually indicates he or she belongs to, with their founding patriarch reckoned to between six and ten generations.

The five major clan families are the traditionally nomadic pastoralist Dir, Isaaq