Smallpox on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Smallpox was an

At least 90% of smallpox cases among unvaccinated persons were of the ordinary type. In this form of the disease, by the second day of the rash the macules had become raised ''

At least 90% of smallpox cases among unvaccinated persons were of the ordinary type. In this form of the disease, by the second day of the rash the macules had become raised ''

Referring to the character of the eruption and the rapidity of its development, modified smallpox occurred mostly in previously vaccinated people. It was rare in unvaccinated people, with one case study showing 1–2% of modified cases compared to around 25% in vaccinated people. In this form, the prodromal illness still occurred but may have been less severe than in the ordinary type. There was usually no fever during the evolution of the rash. The skin lesions tended to be fewer and evolved more quickly, were more superficial, and may not have shown the uniform characteristic of more typical smallpox. Modified smallpox was rarely, if ever, fatal. This form of variola major was more easily confused with

Referring to the character of the eruption and the rapidity of its development, modified smallpox occurred mostly in previously vaccinated people. It was rare in unvaccinated people, with one case study showing 1–2% of modified cases compared to around 25% in vaccinated people. In this form, the prodromal illness still occurred but may have been less severe than in the ordinary type. There was usually no fever during the evolution of the rash. The skin lesions tended to be fewer and evolved more quickly, were more superficial, and may not have shown the uniform characteristic of more typical smallpox. Modified smallpox was rarely, if ever, fatal. This form of variola major was more easily confused with

In malignant-type smallpox (also called flat smallpox) the lesions remained almost flush with the skin at the time when raised vesicles would have formed in the ordinary type. It is unknown why some people developed this type. Historically, it accounted for 5–10% of cases, and most (72%) were children. Malignant smallpox was accompanied by a severe

In malignant-type smallpox (also called flat smallpox) the lesions remained almost flush with the skin at the time when raised vesicles would have formed in the ordinary type. It is unknown why some people developed this type. Historically, it accounted for 5–10% of cases, and most (72%) were children. Malignant smallpox was accompanied by a severe

The early or

The early or

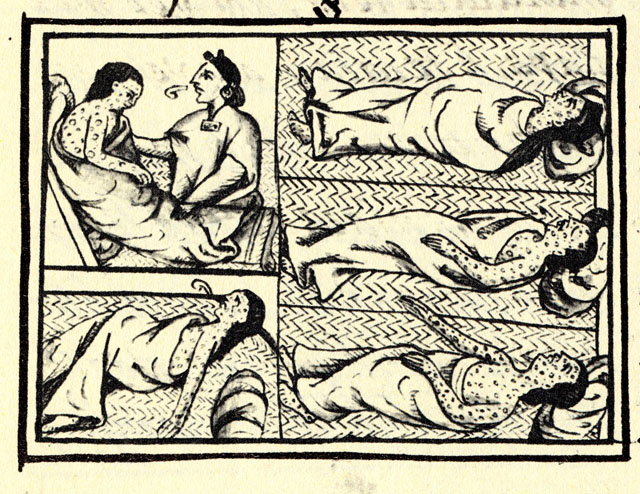

File:Smallpox CAM.png, Smallpox virus lesions on the

The earliest procedure used to prevent smallpox was

The earliest procedure used to prevent smallpox was  The current formulation of the smallpox vaccine is a live virus preparation of the infectious vaccinia virus. The vaccine is given using a bifurcated (two-pronged) needle that is dipped into the vaccine solution. The needle is used to prick the skin (usually the upper arm) several times in a few seconds. If successful, a red and itchy bump develops at the vaccine site in three or four days. In the first week, the bump becomes a large blister (called a "Jennerian vesicle") which fills with pus and begins to drain. During the second week, the blister begins to dry up, and a scab forms. The scab falls off in the third week, leaving a small scar.

The

The current formulation of the smallpox vaccine is a live virus preparation of the infectious vaccinia virus. The vaccine is given using a bifurcated (two-pronged) needle that is dipped into the vaccine solution. The needle is used to prick the skin (usually the upper arm) several times in a few seconds. If successful, a red and itchy bump develops at the vaccine site in three or four days. In the first week, the bump becomes a large blister (called a "Jennerian vesicle") which fills with pus and begins to drain. During the second week, the blister begins to dry up, and a scab forms. The scab falls off in the third week, leaving a small scar.

The  There are side effects and risks associated with the smallpox vaccine. In the past, about 1 out of 1,000 people vaccinated for the first time experienced serious, but non-life-threatening, reactions, including toxic or

There are side effects and risks associated with the smallpox vaccine. In the past, about 1 out of 1,000 people vaccinated for the first time experienced serious, but non-life-threatening, reactions, including toxic or

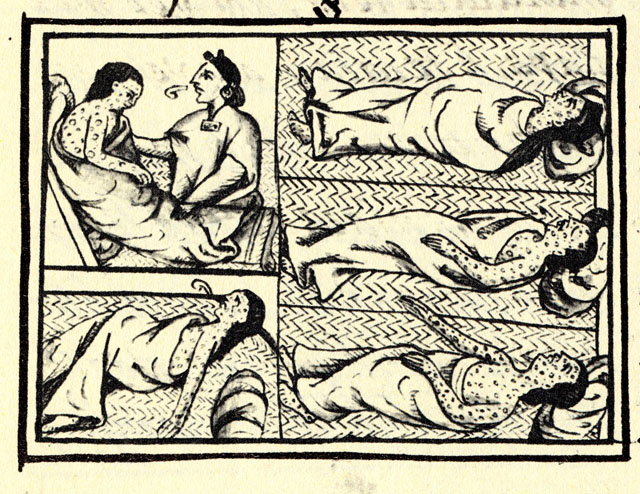

The earliest credible clinical evidence of smallpox is found in the descriptions of smallpox-like disease in medical writings from ancient India (as early as 1500 BCE),''Vaccine and Serum Evils'', by Herbert M. Shelton, p. 5 and China (1122 BCE), Originally published as as well as a study of the

The earliest credible clinical evidence of smallpox is found in the descriptions of smallpox-like disease in medical writings from ancient India (as early as 1500 BCE),''Vaccine and Serum Evils'', by Herbert M. Shelton, p. 5 and China (1122 BCE), Originally published as as well as a study of the  There were no credible descriptions of smallpox-like disease in the

There were no credible descriptions of smallpox-like disease in the  By the mid-18th century, smallpox was a major

By the mid-18th century, smallpox was a major

The first clear reference to smallpox inoculation was made by the Chinese author

The first clear reference to smallpox inoculation was made by the Chinese author  The English physician

The English physician  The first

The first  In the early 1950s, an estimated 50 million cases of smallpox occurred in the world each year. To eradicate smallpox, each outbreak had to be stopped from spreading, by isolation of cases and vaccination of everyone who lived close by. This process is known as "ring vaccination". The key to this strategy was the monitoring of cases in a community (known as surveillance) and containment.

The initial problem the WHO team faced was inadequate reporting of smallpox cases, as many cases did not come to the attention of the authorities. The fact that humans are the only reservoir for smallpox infection and that carriers did not exist played a significant role in the eradication of smallpox. The WHO established a network of consultants who assisted countries in setting up surveillance and containment activities. Early on, donations of vaccine were provided primarily by the Soviet Union and the United States, but by 1973, more than 80 percent of all vaccine was produced in developing countries. The Soviet Union provided one and a half billion doses between 1958 and 1979, as well as the medical staff.

The last major European outbreak of smallpox was in 1972 in Yugoslavia, after a pilgrim from

In the early 1950s, an estimated 50 million cases of smallpox occurred in the world each year. To eradicate smallpox, each outbreak had to be stopped from spreading, by isolation of cases and vaccination of everyone who lived close by. This process is known as "ring vaccination". The key to this strategy was the monitoring of cases in a community (known as surveillance) and containment.

The initial problem the WHO team faced was inadequate reporting of smallpox cases, as many cases did not come to the attention of the authorities. The fact that humans are the only reservoir for smallpox infection and that carriers did not exist played a significant role in the eradication of smallpox. The WHO established a network of consultants who assisted countries in setting up surveillance and containment activities. Early on, donations of vaccine were provided primarily by the Soviet Union and the United States, but by 1973, more than 80 percent of all vaccine was produced in developing countries. The Soviet Union provided one and a half billion doses between 1958 and 1979, as well as the medical staff.

The last major European outbreak of smallpox was in 1972 in Yugoslavia, after a pilgrim from

The last case of smallpox in the world occurred in an outbreak in the United Kingdom in 1978. A medical photographer, Janet Parker, contracted the disease at the

The last case of smallpox in the world occurred in an outbreak in the United Kingdom in 1978. A medical photographer, Janet Parker, contracted the disease at the

Advisory Group of Independent Experts to review the smallpox research program (AGIES) WHO document WHO/HSE/GAR/BDP/2010.4 The latter view is frequently supported in the scientific community, particularly among veterans of the WHO Smallpox Eradication Program. On March 31, 2003, smallpox scabs were found inside an envelope in an 1888 book on

Famous historical figures who contracted smallpox include Lakota Chief

Famous historical figures who contracted smallpox include Lakota Chief

In the face of the devastation of smallpox, various smallpox gods and goddesses have been worshipped throughout parts of the

In the face of the devastation of smallpox, various smallpox gods and goddesses have been worshipped throughout parts of the

Smallpox Biosafety: A Website About Destruction of Smallpox Virus Stocks

Center for Biosecurity

Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Poxviridae

Episode 1 (of 4): Vaccines

of the

Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer

(2021) {{Authority control Chordopoxvirinae Eradicated diseases Virus-related cutaneous conditions Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate

infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus

''Orthopoxvirus'' is a genus of viruses in the family ''Poxviridae'' and subfamily ''Chordopoxvirinae''. Vertebrates, including mammals and humans, and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are 12 species in this genus. Diseases associated wi ...

. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

(WHO) certified the global eradication of the disease in 1980, making it the only human disease to be eradicated.

The initial symptoms of the disease included fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a body temperature, temperature above the human body temperature, normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, set point. There is not a single ...

and vomiting. This was followed by formation of ulcers

An ulcer is a discontinuity or break in a bodily membrane that impedes normal function of the affected organ. According to Robbins's pathology, "ulcer is the breach of the continuity of skin, epithelium or mucous membrane caused by sloughing o ...

in the mouth and a skin rash

A rash is a change of the human skin which affects its color, appearance, or texture.

A rash may be localized in one part of the body, or affect all the skin. Rashes may cause the skin to change color, itch, become warm, bumpy, chapped, dry, cr ...

. Over a number of days, the skin rash turned into the characteristic fluid-filled blister

A blister is a small pocket of body fluid (lymph, serum, plasma, blood, or pus) within the upper layers of the skin, usually caused by forceful rubbing (friction), burning, freezing, chemical exposure or infection. Most blisters are filled wi ...

s with a dent in the center. The bumps then scabbed over and fell off, leaving scars. The disease was spread between people or via contaminated objects. Prevention was achieved mainly through the smallpox vaccine

The smallpox vaccine is the first vaccine to be developed against a contagious disease. In 1796, British physician Edward Jenner demonstrated that an infection with the relatively mild cowpox virus conferred immunity against the deadly smallpox ...

. Once the disease had developed, certain antiviral medication

Antiviral drugs are a class of medication used for treating viral infections. Most antivirals target specific viruses, while a broad-spectrum antiviral is effective against a wide range of viruses. Unlike most antibiotics, antiviral drugs do ...

may have helped. The risk of death was about 30%, with higher rates among babies. Often, those who survived had extensive scarring

A scar (or scar tissue) is an area of fibrous tissue that replaces normal skin after an injury. Scars result from the biological process of wound repair in the skin, as well as in other organs, and tissues of the body. Thus, scarring is a na ...

of their skin, and some were left blind.

The earliest evidence of the disease dates to around 1500 BC in Egyptian mummies

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay furth ...

. The disease historically occurred in outbreaks

In epidemiology, an outbreak is a sudden increase in occurrences of a disease when cases are in excess of normal expectancy for the location or season. It may affect a small and localized group or impact upon thousands of people across an entire ...

. In 18th-century Europe, it is estimated that 400,000 people died from the disease per year, and that one-third of all cases of blindness were due to smallpox. Smallpox is estimated to have killed up to 300 million people in the 20th century and around 500 million people in the last 100 years of its existence. Earlier deaths included six European monarch

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority ...

s. As recently as 1967, 15 million cases occurred a year.

Inoculation

Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or other microorganism. It may refer to methods of artificially inducing immunity against various infectious diseases, or it may be used to describe the spreading of disease, as in "self-inoculati ...

for smallpox appears to have started in China around the 1500s. Europe adopted this practice from Asia in the first half of the 18th century. In 1796, Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner, (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) was a British physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines, and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms ''vaccine'' and ''vaccination'' are derived f ...

introduced the modern smallpox vaccine. In 1967, the WHO intensified efforts to eliminate the disease. Smallpox is one of two infectious diseases to have been eradicated, the other being rinderpest

Rinderpest (also cattle plague or steppe murrain) was an infectious viral disease of cattle, domestic buffalo, and many other species of even-toed ungulates, including gaurs, buffaloes, large antelope, deer, giraffes, wildebeests, and warthogs ...

in 2011. The term "smallpox" was first used in England in the 16th century to distinguish the disease from syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

, which was then known as the "great pox". Other historical names for the disease include pox, speckled monster, and red plague.

Classification

There are two forms of the smallpox. ''Variola major'' is the severe and most common form, with a more extensive rash and higher fever.Variola minor

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The Ali Maow Maalin#Maalin's case, last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World ...

is a less common presentation, causing less severe disease, typically discrete smallpox, with historical death rates of 1% or less. Subclinical (asymptomatic

In medicine, any disease is classified asymptomatic if a patient tests as carrier for a disease or infection but experiences no symptoms. Whenever a medical condition fails to show noticeable symptoms after a diagnosis it might be considered asy ...

) infections with variola virus were noted but were not common. In addition, a form called ''variola sine eruptione'' (smallpox without rash) was seen generally in vaccinated persons. This form was marked by a fever that occurred after the usual incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infectious disease, the i ...

and could be confirmed only by antibody

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

studies or, rarely, by viral culture

Viral culture is a laboratory technique in which samples of a virus are placed to different cell lines which the virus being tested for its ability to infect. If the cells show changes, known as cytopathic effects, then the culture is positive.

...

. In addition, there were two very rare and fulminating types of smallpox, the malignant (flat) and hemorrhagic forms, which were usually fatal.

Signs and symptoms

The initial symptoms were similar to other viral diseases that are still extant, such asinfluenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

and the common cold

The common cold or the cold is a viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract that primarily affects the respiratory mucosa of the nose, throat, sinuses, and larynx. Signs and symptoms may appear fewer than two days after exposu ...

: fever of at least , muscle pain

Myalgia (also called muscle pain and muscle ache in layman's terms) is the medical term for muscle pain. Myalgia is a symptom of many diseases. The most common cause of acute myalgia is the overuse of a muscle or group of muscles; another likel ...

, malaise

As a medical term, malaise is a feeling of general discomfort, uneasiness or lack of wellbeing and often the first sign of an infection or other disease. The word has existed in French since at least the 12th century.

The term is often used ...

, headache and fatigue. As the digestive tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans a ...

was commonly involved, nausea, vomiting, and backache often occurred. The early prodromal

In medicine, a prodrome is an early sign or symptom (or set of signs and symptoms) that often indicates the onset of a disease before more diagnostically specific signs and symptoms develop. It is derived from the Greek word ''prodromos'', meaning ...

stage usually lasted 2–4 days. By days 12–15, the first visible lesions – small reddish spots called ''enanthem

Enanthem or enanthema is a rash (small spots) on the mucous membranes. It is characteristic of patients with viral infections causing hand foot and mouth disease, measles, and sometimes chicken pox, or COVID-19. In addition, bacterial infections ...

'' – appeared on mucous membranes of the mouth, tongue, palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sepa ...

, and throat, and the temperature fell to near-normal. These lesions rapidly enlarged and ruptured, releasing large amounts of virus into the saliva.

Variola virus tended to attack skin cells, causing the characteristic pimples, or macule

A skin condition, also known as cutaneous condition, is any medical condition that affects the integumentary system—the organ system that encloses the body and includes skin, nails, and related muscle and glands. The major function of this sy ...

s, associated with the disease. A rash developed on the skin 24 to 48 hours after lesions on the mucous membranes appeared. Typically the macules first appeared on the forehead, then rapidly spread to the whole face, proximal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

portions of extremities, the trunk, and lastly to distal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

portions of extremities. The process took no more than 24 to 36 hours, after which no new lesions appeared. At this point, variola major disease could take several very different courses, which resulted in four types of smallpox disease based on the Rao classification: ordinary, modified, malignant (or flat), and hemorrhagic smallpox. Historically, ordinary smallpox had an overall fatality rate

In epidemiology, case fatality rate (CFR) – or sometimes more accurately case-fatality risk – is the proportion of people diagnosed with a certain disease, who end up dying of it. Unlike a disease's mortality rate, the CFR does not take int ...

of about 30%, and the malignant and hemorrhagic forms were usually fatal. The modified form was almost never fatal. In early hemorrhagic cases, hemorrhages occurred before any skin lesions developed. The incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infectious disease, the i ...

between contraction and the first obvious symptoms of the disease was 7–14 days.

Ordinary

At least 90% of smallpox cases among unvaccinated persons were of the ordinary type. In this form of the disease, by the second day of the rash the macules had become raised ''

At least 90% of smallpox cases among unvaccinated persons were of the ordinary type. In this form of the disease, by the second day of the rash the macules had become raised ''papule

A papule is a small, well-defined bump in the skin. It may have a rounded, pointed or flat top, and may have a dip. It can appear with a stalk, be thread-like or look warty. It can be soft or firm and its surface may be rough or smooth. Some h ...

s''. By the third or fourth day, the papules had filled with an opalescent fluid to become ''vesicles

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features o ...

''. This fluid became opaque

Opacity or opaque may refer to:

* Impediments to (especially, visible) light:

** Opacities, absorption coefficients

** Opacity (optics), property or degree of blocking the transmission of light

* Metaphors derived from literal optics:

** In lingu ...

and turbid within 24–48 hours, resulting in pustule

A skin condition, also known as cutaneous condition, is any medical condition that affects the integumentary system—the organ system that encloses the body and includes skin, nails, and related muscle and glands. The major function of this sy ...

s.

By the sixth or seventh day, all the skin lesions had become pustules. Between seven and ten days the pustules had matured and reached their maximum size. The pustules were sharply raised, typically round, tense, and firm to the touch. The pustules were deeply embedded in the dermis, giving them the feel of a small bead in the skin. Fluid slowly leaked from the pustules, and by the end of the second week, the pustules had deflated and began to dry up, forming crusts or scabs. By day 16–20 scabs had formed over all of the lesions, which had started to flake off, leaving depigmented scars.

Ordinary smallpox generally produced a discrete rash, in which the pustules stood out on the skin separately. The distribution of the rash was most dense on the face, denser on the extremities than on the trunk, and denser on the distal parts of the extremities than on the proximal. The palms of the hands and soles of the feet were involved in most cases. Sometimes, the blisters merged into sheets, forming a confluent rash, which began to detach the outer layers of skin from the underlying flesh. Patients with confluent smallpox often remained ill even after scabs had formed over all the lesions. In one case series, the case-fatality rate in confluent smallpox was 62%.

Modified

Referring to the character of the eruption and the rapidity of its development, modified smallpox occurred mostly in previously vaccinated people. It was rare in unvaccinated people, with one case study showing 1–2% of modified cases compared to around 25% in vaccinated people. In this form, the prodromal illness still occurred but may have been less severe than in the ordinary type. There was usually no fever during the evolution of the rash. The skin lesions tended to be fewer and evolved more quickly, were more superficial, and may not have shown the uniform characteristic of more typical smallpox. Modified smallpox was rarely, if ever, fatal. This form of variola major was more easily confused with

Referring to the character of the eruption and the rapidity of its development, modified smallpox occurred mostly in previously vaccinated people. It was rare in unvaccinated people, with one case study showing 1–2% of modified cases compared to around 25% in vaccinated people. In this form, the prodromal illness still occurred but may have been less severe than in the ordinary type. There was usually no fever during the evolution of the rash. The skin lesions tended to be fewer and evolved more quickly, were more superficial, and may not have shown the uniform characteristic of more typical smallpox. Modified smallpox was rarely, if ever, fatal. This form of variola major was more easily confused with chickenpox

Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is a highly contagious disease caused by the initial infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV). The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which eventually scab ...

.

Malignant

In malignant-type smallpox (also called flat smallpox) the lesions remained almost flush with the skin at the time when raised vesicles would have formed in the ordinary type. It is unknown why some people developed this type. Historically, it accounted for 5–10% of cases, and most (72%) were children. Malignant smallpox was accompanied by a severe

In malignant-type smallpox (also called flat smallpox) the lesions remained almost flush with the skin at the time when raised vesicles would have formed in the ordinary type. It is unknown why some people developed this type. Historically, it accounted for 5–10% of cases, and most (72%) were children. Malignant smallpox was accompanied by a severe prodromal

In medicine, a prodrome is an early sign or symptom (or set of signs and symptoms) that often indicates the onset of a disease before more diagnostically specific signs and symptoms develop. It is derived from the Greek word ''prodromos'', meaning ...

phase that lasted 3–4 days, prolonged high fever, and severe symptoms of viremia

Viremia is a medical condition where viruses enter the bloodstream and hence have access to the rest of the body. It is similar to ''bacteremia'', a condition where bacteria enter the bloodstream. The name comes from combining the word "virus" wit ...

. The prodromal symptoms continued even after the onset of the rash. The rash on the mucous membranes (enanthem

Enanthem or enanthema is a rash (small spots) on the mucous membranes. It is characteristic of patients with viral infections causing hand foot and mouth disease, measles, and sometimes chicken pox, or COVID-19. In addition, bacterial infections ...

) was extensive. Skin lesions matured slowly, were typically confluent or semi-confluent, and by the seventh or eighth day, they were flat and appeared to be buried in the skin. Unlike ordinary-type smallpox, the vesicles contained little fluid, were soft and velvety to the touch, and may have contained hemorrhages. Malignant smallpox was nearly always fatal and death usually occurred between the 8th and 12th day of illness. Often, a day or two before death, the lesions turned ashen gray, which, along with abdominal distension, was a bad prognostic sign. This form is thought to be caused by deficient cell-mediated immunity

Cell-mediated immunity or cellular immunity is an immune response that does not involve antibodies. Rather, cell-mediated immunity is the activation of phagocytes, antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, and the release of various cytokines in ...

to smallpox. If the person recovered, the lesions gradually faded and did not form scars or scabs.

Hemorrhagic

Hemorrhagic

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vagi ...

smallpox is a severe form accompanied by extensive bleeding into the skin, mucous membranes, gastrointestinal tract, and viscera

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

. This form develops in approximately 2% of infections and occurs mostly in adults. Pustules do not typically form in hemorrhagic smallpox. Instead, bleeding occurs under the skin, making it look charred and black, hence this form of the disease is also referred to as variola nigra or "black pox". Hemorrhagic smallpox has very rarely been caused by variola minor virus. While bleeding may occur in mild cases and not affect outcomes, hemorrhagic smallpox is typically fatal. Vaccination does not appear to provide any immunity to either form of hemorrhagic smallpox and some cases even occurred among people that were revaccinated shortly before. It has two forms.

Early

The early or

The early or fulminant

Fulminant () is a medical descriptor for any event or process that occurs suddenly and escalates quickly, and is intense and severe to the point of lethality, i.e., it has an explosive character. The word comes from Latin ''fulmināre'', to strike ...

form of hemorrhagic smallpox (referred to as ''purpura variolosa'') begins with a prodromal phase characterized by a high fever, severe headache, and abdominal pain. The skin becomes dusky and erythematous, and this is rapidly followed by the development of petechia

A petechia () is a small red or purple spot (≤4 mm in diameter) that can appear on the skin, conjunctiva, retina, and Mucous membrane, mucous membranes which is caused by haemorrhage of capillaries. The word is derived from Italian , 'freckle,' ...

e and bleeding in the skin, conjunctiva

The conjunctiva is a thin mucous membrane that lines the inside of the eyelids and covers the sclera (the white of the eye). It is composed of non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium with goblet cells, stratified columnar epithelium ...

and mucous membranes. Death often occurs suddenly between the fifth and seventh days of illness, when only a few insignificant skin lesions are present. Some people survive a few days longer, during which time the skin detaches and fluid accumulates under it, rupturing at the slightest injury. People are usually conscious until death or shortly before. Autopsy reveals petechiae

A petechia () is a small red or purple spot (≤4 mm in diameter) that can appear on the skin, conjunctiva, retina, and mucous membranes which is caused by haemorrhage of capillaries. The word is derived from Italian , 'freckle,' of obscure origin ...

and bleeding in the spleen, kidney, serous membranes

The serous membrane (or serosa) is a smooth tissue membrane of mesothelium lining the contents and inner walls of body cavities, which secrete serous fluid to allow lubricated sliding movements between opposing surfaces. The serous membrane ...

, skeletal muscles, pericardium

The pericardium, also called pericardial sac, is a double-walled sac containing the heart and the roots of the great vessels. It has two layers, an outer layer made of strong connective tissue (fibrous pericardium), and an inner layer made of ...

, liver, gonads and bladder. Historically, this condition was frequently misdiagnosed, with the correct diagnosis made only at autopsy. This form is more likely to occur in pregnant women than in the general population (approximately 16% of cases in unvaccinated pregnant women were early hemorrhagic smallpox, versus roughly 1% in nonpregnant women and adult males). The case fatality rate of early hemorrhagic smallpox approaches 100%.

Late

There is also a later form of hemorrhagic smallpox (referred to late hemorrhagic smallpox, or ''variolosa pustula hemorrhagica''). The prodrome is severe and similar to that observed in early hemorrhagic smallpox, and the fever persists throughout the course of the disease. Bleeding appears in the early eruptive period (but later than that seen in ''purpura variolosa''), and the rash is often flat and does not progress beyond the vesicular stage. Hemorrhages in the mucous membranes appear to occur less often than in the early hemorrhagic form. Sometimes the rash forms pustules which bleed at the base and then undergo the same process as in ordinary smallpox. This form of the disease is characterized by a decrease in all of the elements of thecoagulation

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

cascade and an increase in circulating antithrombin

Antithrombin (AT) is a small glycoprotein that inactivates several enzymes of the coagulation system. It is a 432-amino-acid protein produced by the liver. It contains three disulfide bonds and a total of four possible glycosylation sites. α-An ...

. This form of smallpox occurs anywhere from 3% to 25% of fatal cases, depending on the virulence of the smallpox strain. Most people with the late-stage form die within eight to 10 days of illness. Among the few who recover, the hemorrhagic lesions gradually disappear after a long period of convalescence. The case fatality rate for late hemorrhagic smallpox is around 90–95%. Pregnant women are slightly more likely to experience this form of the disease, though not as much as early hemorrhagic smallpox.

Cause

Smallpox was caused by infection with variola virus, which belongs to the family ''Poxviridae

''Poxviridae'' is a family of double-stranded DNA viruses. Vertebrates and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are currently 83 species in this family, divided among 22 genera, which are divided into two subfamilies. Diseases associated wit ...

'', subfamily ''Chordopoxvirinae

''Chordopoxvirinae'' is a subfamily of viruses in the family ''Poxviridae''. Humans, vertebrates, and arthropods serve as natural hosts. Currently, 52 species are placed in this subfamily, divided among 18 genera. Diseases associated with this s ...

'', and genus ''Orthopoxvirus

''Orthopoxvirus'' is a genus of viruses in the family ''Poxviridae'' and subfamily ''Chordopoxvirinae''. Vertebrates, including mammals and humans, and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are 12 species in this genus. Diseases associated wi ...

''.

Evolution

The date of the appearance of smallpox is not settled. It most probably evolved from a terrestrial African rodent virus between 68,000 and 16,000 years ago. The wide range of dates is due to the different records used to calibrate themolecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleoti ...

. One clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

was the variola major strains (the more clinically severe form of smallpox) which spread from Asia between 400 and 1,600 years ago. A second clade included both alastrim (a phenotypically mild smallpox) described from the American continents and isolates from West Africa which diverged from an ancestral strain between 1,400 and 6,300 years before present. This clade further diverged into two subclades at least 800 years ago.

A second estimate has placed the separation of variola virus from Taterapox (an Orthopoxvirus

''Orthopoxvirus'' is a genus of viruses in the family ''Poxviridae'' and subfamily ''Chordopoxvirinae''. Vertebrates, including mammals and humans, and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are 12 species in this genus. Diseases associated wi ...

of some African rodents including gerbil

The Mongolian gerbil or Mongolian jird (''Meriones unguiculatus'') is a small rodent belonging to the subfamily Gerbillinae. Their body size is typically , with a tail, and body weight , with adult males larger than females. The animal is use ...

s) at 3,000 to 4,000 years ago. This is consistent with archaeological and historical evidence regarding the appearance of smallpox as a human disease which suggests a relatively recent origin. If the mutation rate is assumed to be similar to that of the herpesvirus

''Herpesviridae'' is a large family of DNA viruses that cause infections and certain diseases in animals, including humans. The members of this family are also known as herpesviruses. The family name is derived from the Greek word ''ἕρπειν ...

es, the divergence date of variola virus from Taterapox has been estimated to be 50,000 years ago. While this is consistent with the other published estimates, it suggests that the archaeological and historical evidence is very incomplete. Better estimates of mutation rates in these viruses are needed.

Examination of a strain that dates from c. 1650 found that this strain was basal to the other presently sequenced strains. The mutation rate of this virus is well modeled by a molecular clock. Diversification of strains only occurred in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Virology

Variola virus is large brick-shaped and is approximately 302 to 350nanometer

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the molecular scale.

The nanometre (international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: nm) or nanometer (American and British English spelling differences#-re ...

s by 244 to 270 nm, with a single linear double stranded DNA genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

186 kilobase pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s (kbp) in size and containing a hairpin loop

Stem-loop intramolecular base pairing is a pattern that can occur in single-stranded RNA. The structure is also known as a hairpin or hairpin loop. It occurs when two regions of the same strand, usually complementary in nucleotide sequence wh ...

at each end.

Four orthopoxviruses cause infection in humans: variola, vaccinia

''Vaccinia virus'' (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

, cowpox

Cowpox is an infectious disease caused by the ''cowpox virus'' (CPXV). It presents with large blisters in the skin, a fever and swollen glands, historically typically following contact with an infected cow, though in the last several decades more ...

, and monkeypox

Monkeypox (also called mpox by the WHO) is an infectious viral disease that can occur in humans and some other animals. Symptoms include fever, swollen lymph nodes, and a rash that forms blisters and then crusts over. The time from exposure to ...

. Variola virus infects only humans in nature, although primates and other animals have been infected in an experimental setting. Vaccinia, cowpox, and monkeypox viruses can infect both humans and other animals in nature.

The life cycle of poxviruses is complicated by having multiple infectious forms, with differing mechanisms of cell entry. Poxviruses are unique among human DNA viruses in that they replicate in the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

of the cell rather than in the nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

. To replicate, poxviruses produce a variety of specialized proteins not produced by other DNA viruses

A DNA virus is a virus that has a genome made of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) that is replicated by a DNA polymerase. They can be divided between those that have two strands of DNA in their genome, called double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, and ...

, the most important of which is a viral-associated DNA-dependent RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

.

Both enveloped and unenveloped virions

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

are infectious. The viral envelope is made of modified Golgi membranes containing viral-specific polypeptides, including hemagglutinin

In molecular biology, hemagglutinins (or ''haemagglutinin'' in British English) (from the Greek , 'blood' + Latin , 'glue') are receptor-binding membrane fusion glycoproteins produced by viruses in the ''Paramyxoviridae'' family. Hemagglutinins ar ...

. Infection with either variola major virus or variola minor virus confers immunity against the other.

Variola major

The more common, infectious form of the disease was caused by the variola major virus strain.Variola minor

Variola minor virus, also called alastrim, was a less common form of the virus, and much less deadly. Although variola minor had the same incubation period and pathogenetic stages as smallpox, it is believed to have had a mortality rate of less than 1%, as compared to smallpox's 30%. Like variola major, variola minor was spread through inhalation of the virus in the air, which could occur through face-to-face contact or through fomites. Infection with variola minor virus conferred immunity against the more dangerous variola major virus. Because variola minor was a less debilitating disease than smallpox, people were more frequently ambulant and thus able to infect others more rapidly. As such, variola minor swept through the United States, Great Britain, and South Africa in the early 20th century, becoming the dominant form of the disease in those areas and thus rapidly decreasing mortality rates. Along with variola major, the minor form has now been totally eradicated from the globe. The last case of indigenous variola minor was reported in a Somali cook, Ali Maow Maalin, in October 1977, and smallpox was officially declared eradicated worldwide in May 1980. Variola minor was also called white pox, kaffir pox, Cuban itch, West Indian pox, milk pox, and pseudovariola.Genome composition

Thegenome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

of variola major virus is about 186,000 base pairs in length. It is made from linear double stranded DNA and contains the coding sequence

The coding region of a gene, also known as the coding sequence (CDS), is the portion of a gene's DNA or RNA that codes for protein. Studying the length, composition, regulation, splicing, structures, and functions of coding regions compared to no ...

for about 200 gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s. The genes are usually not overlapping and typically occur in blocks that point towards the closer terminal region of the genome. The coding sequence of the central region of the genome is highly consistent across orthopoxvirus

''Orthopoxvirus'' is a genus of viruses in the family ''Poxviridae'' and subfamily ''Chordopoxvirinae''. Vertebrates, including mammals and humans, and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are 12 species in this genus. Diseases associated wi ...

es, and the arrangement of genes is consistent across chordopoxviruses

The center of the variola virus genome contains the majority of the essential viral genes, including the genes for structural protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s, DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

, transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

, and mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

synthesis. The ends of the genome vary more across strains and species of orthopoxvirus

''Orthopoxvirus'' is a genus of viruses in the family ''Poxviridae'' and subfamily ''Chordopoxvirinae''. Vertebrates, including mammals and humans, and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are 12 species in this genus. Diseases associated wi ...

es. These regions contain proteins that modulate the hosts' immune systems, and are primarily responsible for the variability in virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ca ...

across the orthopoxvirus

''Orthopoxvirus'' is a genus of viruses in the family ''Poxviridae'' and subfamily ''Chordopoxvirinae''. Vertebrates, including mammals and humans, and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are 12 species in this genus. Diseases associated wi ...

family. These terminal regions in poxviruses are inverted terminal repetitions (ITR) sequences. These sequences are identical but oppositely oriented on either end of the genome, leading to the genome being a continuous loop of DNA Components of the ITR sequences include an incompletely base paired A/T rich hairpin loop

Stem-loop intramolecular base pairing is a pattern that can occur in single-stranded RNA. The structure is also known as a hairpin or hairpin loop. It occurs when two regions of the same strand, usually complementary in nucleotide sequence wh ...

, a region of roughly 100 base pairs necessary for resolving concatomeric DNA (a stretch of DNA containing multiple copies of the same sequence), a few open reading frame

In molecular biology, open reading frames (ORFs) are defined as spans of DNA sequence between the start and stop codons. Usually, this is considered within a studied region of a prokaryotic DNA sequence, where only one of the six possible readin ...

s, and short tandemly repeating sequences of varying number and length. The ITRs of poxviridae

''Poxviridae'' is a family of double-stranded DNA viruses. Vertebrates and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are currently 83 species in this family, divided among 22 genera, which are divided into two subfamilies. Diseases associated wit ...

vary in length across strains and species. The coding sequence for most of the viral proteins in variola major virus have at least 90% similarity with the genome of vaccinia

''Vaccinia virus'' (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

, a related virus used for vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

against smallpox.

Gene expression

Gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. The ...

of variola virus occurs entirely within the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

of the host cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

, and follows a distinct progression during infection. After entry of an infectious virion

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

into a host cell, synthesis of viral mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

can be detected within 20 minutes. About half of the viral genome is transcribed prior to the replication of viral DNA. The first set of expressed genes are transcribed by pre-existing viral machinery packaged within the infecting virion. These genes encode the factors necessary for viral DNA synthesis and for transcription of the next set of expressed genes. Unlike most DNA viruses, DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

in variola virus and other poxviruses takes place within the cytoplasm of the infected cell. The exact timing of DNA replication after infection of a host cell varies across the poxviridae

''Poxviridae'' is a family of double-stranded DNA viruses. Vertebrates and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are currently 83 species in this family, divided among 22 genera, which are divided into two subfamilies. Diseases associated wit ...

. Recombination of the genome occurs within actively infected cells. Following the onset of viral DNA replication, an intermediate set of genes codes for transcription factor

In molecular biology, a transcription factor (TF) (or sequence-specific DNA-binding factor) is a protein that controls the rate of transcription of genetic information from DNA to messenger RNA, by binding to a specific DNA sequence. The fu ...

s of late gene expression. The products

Product may refer to:

Business

* Product (business), an item that serves as a solution to a specific consumer problem.

* Product (project management), a deliverable or set of deliverables that contribute to a business solution

Mathematics

* Produ ...

of the later genes include transcription factors necessary for transcribing the early genes for new virions, as well as viral RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

and other essential enzymes for new viral particles. These proteins are then packaged into new infectious virions capable of infecting other cells.

Research

Two live samples of variola major virus remain, one in the United States at theCDC

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the National public health institutes, national public health agency of the United States. It is a Federal agencies of the United States, United States federal agency, under the United S ...

in Atlanta, and one at the Vector Institute in Koltsovo, Russia. Research with the remaining virus samples is tightly controlled, and each research proposal must be approved by the WHO

Who or WHO may refer to:

* Who (pronoun), an interrogative or relative pronoun

* Who?, one of the Five Ws in journalism

* World Health Organization

Arts and entertainment Fictional characters

* Who, a creature in the Dr. Seuss book ''Horton Hear ...

and the World Health Assembly

The World Health Assembly (WHA) is the forum through which the World Health Organization (WHO) is governed by its 194 member states. It is the world's highest health policy setting body and is composed of health ministers from member states.

T ...

(WHA). Most research on poxviruses is performed using the closely related ''Vaccinia virus

''Vaccinia virus'' (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

'' as a model organism. Vaccinia virus, which is used to vaccinate for smallpox, is also under research as a viral vector

Viral vectors are tools commonly used by molecular biologists to deliver genetic material into cells. This process can be performed inside a living organism (''in vivo'') or in cell culture (''in vitro''). Viruses have evolved specialized molecul ...

for vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

s for unrelated diseases.

The genome of variola major virus was first sequenced

In genetics and biochemistry, sequencing means to determine the primary structure (sometimes incorrectly called the primary sequence) of an unbranched biopolymer. Sequencing results in a symbolic linear depiction known as a sequence which suc ...

in its entirety in the 1990s. The complete coding sequence is publicly available online.The current reference sequence for variola major virus was sequenced from a strain that circulated in India in 1967. In addition, there are sequences for samples of other strains that were collected during the WHO eradication campaign. A genome browser In bioinformatics, a genome browser is a graphical interface for display of information from a biological database for genomic data. Genome browsers enable researchers to visualize and browse entire genomes with annotated data including gene predic ...

for a complete database of annotated sequences of variola virus and other poxviruses is publicly available through the Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center

The Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (VBRC) is an online resource providing access to a database of curated viral genomes and a variety of tools for bioinformatic genome analysis. This resource was one of eight BRCs (Bioinformatics Resource C ...

.

Genetic engineering

TheWHO

Who or WHO may refer to:

* Who (pronoun), an interrogative or relative pronoun

* Who?, one of the Five Ws in journalism

* World Health Organization

Arts and entertainment Fictional characters

* Who, a creature in the Dr. Seuss book ''Horton Hear ...

currently bans genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including t ...

of the variola virus. However, in 2004, a committee advisory to the WHO voted in favor of allowing editing of the genome of the two remaining samples of variola major virus to add a marker gene In biology, a marker gene may have several meanings. In nuclear biology and molecular biology, a marker gene is a gene used to determine if a nucleic acid sequence has been successfully inserted into an organism's DNA. In particular, there are tw ...

. This gene, called GFP GFP may refer to:

Organisations

* Gaelic Football Provence, a French Gaelic Athletic Association club

* Geheime Feldpolizei, the German secret military police during the Second World War

* French Group for the Study of Polymers and their Applicat ...

, or green fluorescent protein, would cause live samples of the virus to glow green under fluorescent light. The insertion of this gene, which would not influence the virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ca ...

of the virus, would be the only allowed modification of the genome. The committee stated the proposed modification would aid in research of treatments by making it easier to assess whether a potential treatment was effective in killing viral samples. The recommendation could only take effect if approved by the WHA. When the WHA discussed the proposal in 2005, it refrained from taking a formal vote on the proposal, stating that it would review individual research proposals one at a time. Addition of the GFP gene to the ''Vaccinia

''Vaccinia virus'' (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

'' genome is routinely performed during research on the closely related ''Vaccinia virus

''Vaccinia virus'' (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

''.

Controversies

The public availability of the variola virus complete sequence has raised concerns about the possibility of illicit synthesis of infectious virus. ''Vaccinia

''Vaccinia virus'' (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

'', a cousin of the variola virus, was artificially synthesized in 2002 by NIH

The National Institutes of Health, commonly referred to as NIH (with each letter pronounced individually), is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in the late ...

scientists. They used a previously established method that involved using a recombinant viral genome to create a self-replicating bacterial plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; how ...

that produced viral particles.

In 2016, another group synthesized the horsepox

''Orthopoxvirus'' is a genus of viruses in the family ''Poxviridae'' and subfamily ''Chordopoxvirinae''. Vertebrates, including mammals and humans, and arthropods serve as natural hosts. There are 12 species in this genus. Diseases associated wi ...

virus using publicly available sequence data for horsepox. The researchers argued that their work would be beneficial to creating a safer and more effective vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

for smallpox, although an effective vaccine is already available. The horsepox virus had previously seemed to have gone extinct, raising concern about potential revival of variola major and causing other scientists to question their motives. Critics found it especially concerning that the group was able to recreate viable virus in a short time frame with relatively little cost or effort. Although the WHO bans individual laboratories from synthesizing more than 20% of the genome at a time, and purchases of smallpox genome fragments are monitored and regulated, a group with malicious intentions could compile, from multiple sources, the full synthetic genome necessary to produce viable virus.

Transmission

Transmission occurred through inhalation ofairborne

Airborne or Airborn may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''Airborne'' (1962 film), a 1962 American film directed by James Landis

* ''Airborne'' (1993 film), a comedy–drama film

* ''Airborne'' (1998 film), an action film sta ...

variola virus, usually droplets expressed from the oral, nasal, or pharyngeal mucosa

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It is ...

of an infected person. It was transmitted from one person to another primarily through prolonged face-to-face contact with an infected person, usually, within a distance of , but could also be spread through direct contact with infected bodily fluids or contaminated objects (fomite

A fomite () or fomes () is any inanimate object that, when contaminated with or exposed to infectious agents (such as pathogenic bacteria, viruses or fungi), can transfer disease to a new host.

Transfer of pathogens by fomites

A fomite is any ina ...

s) such as bedding or clothing. Rarely, smallpox was spread by virus carried in the air in enclosed settings such as buildings, buses, and trains. The virus can cross the placenta

The placenta is a temporary embryonic and later fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas and waste exchange between the physically separate mater ...

, but the incidence of congenital

A birth defect, also known as a congenital disorder, is an abnormal condition that is present at birth regardless of its cause. Birth defects may result in disabilities that may be physical, intellectual, or developmental. The disabilities can ...

smallpox was relatively low. Smallpox was not notably infectious in the prodromal

In medicine, a prodrome is an early sign or symptom (or set of signs and symptoms) that often indicates the onset of a disease before more diagnostically specific signs and symptoms develop. It is derived from the Greek word ''prodromos'', meaning ...

period and viral shedding was usually delayed until the appearance of the rash, which was often accompanied by lesion

A lesion is any damage or abnormal change in the tissue of an organism, usually caused by disease or trauma. ''Lesion'' is derived from the Latin "injury". Lesions may occur in plants as well as animals.

Types

There is no designated classifi ...

s in the mouth and pharynx. The virus can be transmitted throughout the course of the illness, but this happened most frequently during the first week of the rash when most of the skin lesions were intact. Infectivity waned in 7 to 10 days when scabs formed over the lesions, but the infected person was contagious until the last smallpox scab fell off.

Smallpox was highly contagious, but generally spread more slowly and less widely than some other viral diseases, perhaps because transmission required close contact and occurred after the onset of the rash. The overall rate of infection was also affected by the short duration of the infectious stage. In temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

areas, the number of smallpox infections was highest during the winter and spring. In tropical areas, seasonal variation was less evident and the disease was present throughout the year. Age distribution of smallpox infections depended on acquired immunity

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate pathogens or prevent their growth. The acquired immune system ...

. Vaccination

Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating ...

immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity desc ...

declined over time and was probably lost within thirty years. Smallpox was not known to be transmitted by insects or animals and there was no asymptomatic carrier

An asymptomatic carrier is a person or other organism that has become infected with a pathogen, but shows no signs or symptoms.

Although unaffected by the pathogen, carriers can transmit it to others or develop symptoms in later stages of the d ...

state.

Mechanism

Once inhaled, the variola virus invaded the mucus membranes of the mouth, throat, and respiratory tract. From there, it migrated to regionallymph nodes

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that includ ...

and began to multiply. In the initial growth phase, the virus seemed to move from cell to cell, but by around the 12th day, widespread lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

of infected cells occurred and the virus could be found in the bloodstream in large numbers, a condition known as viremia

Viremia is a medical condition where viruses enter the bloodstream and hence have access to the rest of the body. It is similar to ''bacteremia'', a condition where bacteria enter the bloodstream. The name comes from combining the word "virus" wit ...

. This resulted in the second wave of multiplication in the spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

, bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid tissue found within the spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It is composed of hematopoietic ce ...

, and lymph nodes.

Diagnosis

The clinical definition of ordinary smallpox is an illness with acute onset of fever equal to or greater than followed by a rash characterized by firm, deep-seated vesicles or pustules in the same stage of development without other apparent cause. When a clinical case was observed, smallpox was confirmed using laboratory tests.Microscopically

Microscopy is the technical field of using microscopes to view objects and areas of objects that cannot be seen with the naked eye (objects that are not within the resolution range of the normal eye). There are three well-known branches of micr ...

, poxviruses produce characteristic cytoplasmic

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. Th ...

inclusion bodies

Inclusion bodies are aggregates of specific types of protein found in neurons, a number of tissue cells including red blood cells, bacteria, viruses, and plants. Inclusion bodies of aggregations of multiple proteins are also found in muscle cells ...

, the most important of which are known as Guarnieri bodies Orthopoxvirus inclusion bodies are aggregates of stainable protein produced by poxvirus virions in the cell nuclei and/or cytoplasm of epithelial cells in humans. They are important as sites of viral replication.

Morphology

Morphologically there ...

, and are the sites of viral replication

Viral replication is the formation of biological viruses during the infection process in the target host cells. Viruses must first get into the cell before viral replication can occur. Through the generation of abundant copies of its genome an ...

. Guarnieri bodies are readily identified in skin biopsies stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and appear as pink blobs. They are found in virtually all poxvirus infections but the absence of Guarnieri bodies could not be used to rule out smallpox. The diagnosis of an orthopoxvirus infection can also be made rapidly by electron microscopic examination of pustular fluid or scabs. All orthopoxviruses exhibit identical brick-shaped virions

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

by electron microscopy. If particles with the characteristic morphology of herpesvirus

''Herpesviridae'' is a large family of DNA viruses that cause infections and certain diseases in animals, including humans. The members of this family are also known as herpesviruses. The family name is derived from the Greek word ''ἕρπειν ...

es are seen this will eliminate smallpox and other orthopoxvirus infections.

Definitive laboratory identification of variola virus involved growing the virus on chorioallantoic membrane

The Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM), also known as the chorioallantois, is a highly vascularized membrane found in the eggs of certain amniotes like birds and reptiles. It is formed by the fusion of the mesodermal layers of two extra-embryonic memb ...

(part of a chicken embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

) and examining the resulting pock lesions under defined temperature conditions. Strains were characterized by polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) t ...

(PCR) and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. Serologic

Serology is the scientific study of serum and other body fluids. In practice, the term usually refers to the diagnostic identification of antibodies in the serum. Such antibodies are typically formed in response to an infection (against a given mi ...

tests and enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay uses a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence ...

s (ELISA), which measured variola virus-specific immunoglobulin and antigen were also developed to assist in the diagnosis of infection.

Chickenpox

Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is a highly contagious disease caused by the initial infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV). The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which eventually scab ...

was commonly confused with smallpox in the immediate post-eradication era. Chickenpox and smallpox could be distinguished by several methods. Unlike smallpox, chickenpox does not usually affect the palms and soles. Additionally, chickenpox pustules are of varying size due to variations in the timing of pustule eruption: smallpox pustules are all very nearly the same size since the viral effect progresses more uniformly. A variety of laboratory methods were available for detecting chickenpox in the evaluation of suspected smallpox cases.

chorioallantoic membrane

The Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM), also known as the chorioallantois, is a highly vascularized membrane found in the eggs of certain amniotes like birds and reptiles. It is formed by the fusion of the mesodermal layers of two extra-embryonic memb ...

of a developing chick.

File:Smallpox versus chickenpox english plain.svg, In contrast to the rash in smallpox, the rash in chickenpox

Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is a highly contagious disease caused by the initial infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV). The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which eventually scab ...

occurs mostly on the torso, spreading less to the limbs.

File:Female smallpox patient -- late-stage confluent maculopapular scarring.jpg, An Italian female smallpox patient whose skin displayed the characteristics of late-stage confluent maculopapular scarring, 1965.

Prevention

The earliest procedure used to prevent smallpox was

The earliest procedure used to prevent smallpox was inoculation

Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or other microorganism. It may refer to methods of artificially inducing immunity against various infectious diseases, or it may be used to describe the spreading of disease, as in "self-inoculati ...