Sir John Berry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

By 1680 Charles II had threatened to give up

By 1680 Charles II had threatened to give up

Berry was placed in command at

Berry was placed in command at

Sir John Berry (1635-1690/91)

from the Three Decks website {{DEFAULTSORT:Berry, John 1635 births 1690 deaths Military personnel from Devon Royal Navy admirals People of British North America Captains of Deal Castle Year of death unknown 17th-century Royal Navy personnel People from North Devon (district)

Rear admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Sir John Berry (14 February 1689 or 1690) was an English officer of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

.

Origins and early years

John Berry was born atKnowstone

Knowstone is a village and civil parish situated in the North Devon district of Devon, England, halfway between the Mid Devon town of Tiverton, Devon and the North Devon town of South Molton. The hamlet of East Knowstone lies due east of the vi ...

, in the English county of Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

. He was the second of seven sons of Daniel Berry, the vicar

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pref ...

of Knowstone ''cum'' Molland

Molland is a small village, civil parish, dual ecclesiastical parish with Knowstone, located in the foothills of Exmoor in Devon, England. It lies within the North Devon local government district. At the time of the 2001 Census, the village h ...

by his wife Elizabeth Moore, daughter of Sir John Moore of Moor Hayes

Moor Hays (''alias'' Moore Hays, Moorhays, Moorhayes, etc.) is a historic estate in the parish of Cullompton in Devon, England. It is stated incorrectly to be in the nearby parish of Burlescombe in Tristram Risdon's ''Survey of Devon''. The es ...

, Devon. Daniel Berry held the benefice

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

, which he had inherited from his own father, but had been deprived of his position during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

.

The Berry family was established during the reign of Edward I of England

Edward I (17/18 June 1239 – 7 July 1307), also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1272 to 1307. Concurrently, he ruled the duchies of Aquitaine and Gascony as a vassa ...

. The family name was derived from their manor of ''Nerbert'' or ''Narbor'' (modern Berrynarbor) near the Devon coast.

The Civil War saw the family's finances ruined, as Daniel Berry had been committed to the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

cause. After his father's death in 1652, John Berry and his elder brother joined the merchant service.

Naval career

Commands

* ''Swallow'' (7 October.1665 to 6 February 1665/66) * ''Guinea'' (16 August to 1 November 1666) * ''Coronation'' (1667) * ''Pearl'' (11 November 1668 to 12 January 1670) * ''Nonsuch'' (13 January 1670 to 10 July 1671) * ''Dover'' (1 September 1671 to 8 April 1672) * ''Resolution'';(11 April 1672 to 3 April 1674) First Battle of Schooneveld (28 May 1673) * ''Swallow'' (9 March 1674/5 to 28 April 1675) * ''Bristol'' (28 April 1675 to 7 January 1677/78) * ''Dreadnought'' (7 January 1677/78 to 21 August 1679) * ''Leopard'' (28 January 1679/80 to 20 April 1681) * ''Gloucester'' (8.April 1682 to 6.May 1682) * ''Henrietta'' (15 June 1682 to 18 April 1684) * ''Elizabeth'' (1688 to 1689) Battle of Bantry Bay (1 May 1689)Early career

By 1663 Berry had joined theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

as the boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, is the most senior rate of the deck department and is responsible for the components of a ship's hull. The boatswain supervi ...

of the ketch HMS ''Swallow'', which was operating in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

. When the captain of ''Swallow'' was promoted in 1665, Berry succeeded him, gaining his first command on 17 Sept. 1665. Upon his return to England in 1666. George Monck, the Duke of Albemarle gave him commissions for the ''Little Mary'' in February, and HMS ''Guinea'' on 16 August, a command he retained until 1 November. In the summer of 1666 he had overall responsibility for the smaller vessels attending the fleet.

Nevis (1667)

The Dutch and the French were threatening English possessions in the West Indies, and the island of Nevis seemed next to fall. In April 1667, Berry, in the ''Coronation'', a 56-gun hiredman-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed wi ...

, arrived at Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

from England. Merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are u ...

s were bought and adapted for service, and 10 vessels and a fireship were made ready. Berry was given overall command of the squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, ...

by the governor of Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

, Lord Willoughby

Baron Willoughby of Parham was a title in the Peerage of England with two creations. The first creation was for Sir William Willoughby who was raised to the peerage under letters patent in 1547, with the remainder to his heirs male of body. A ...

. The French and Dutch possibly collected 20 men-of-war and other vessels at Saint Kitts

Saint Kitts, officially the Saint Christopher Island, is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean. Saint Kitts and the neighbouring island of Nevis cons ...

.

Berry blockaded the allied fleet as they were preparing to themselves attack the English, and on 20 May 1667 the French and the Dutch were defeated in an engagement that lasted for many hours. He successfully forced them to retreat, the French departing for Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

, and the Dutch for Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

. The English victory at the Battle of Nevis

The Battle of Nevis on 20 May 1667 was a confused naval clash in the Caribbean off the island of Nevis during the closing stages of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. It was fought between an English squadron and an Allied Franco-Dutch fleet intent on ...

enabled the Royal Navy to regain Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

and Montserrat

Montserrat ( ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, with r ...

.

Newfoundland

In 1675, Berry was captain of the annualNewfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

convoy. The permanent settlers there had been ordered to remove themselves to other colonies in America or be forcibly removed to England. As captain of the annual convoy, Berry was the representative of royal authority in the island and it was his duty to inform the settlers of this decision. Berry reported that the colonists were being unjustly treated. His attempts to present their case in a favourable light and his views ultimately resulted in the settlers becoming permanently established on the island, and British policy being reversed.

Virginia (1677)

Berry took HMS ''Bristol'' to theMediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

in 1675–1676, taking her to Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

in January 1677 to deal with Bacon's Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion was an armed rebellion held by Colony of Virginia, Virginia settlers that took place from 1676 to 1677. It was led by Nathaniel Bacon (Virginia colonist), Nathaniel Bacon against List of colonial governors of Virginia, Colon ...

. The rebels had already been dealt with, and Berry instead became involved in the aftermath of the rebellion, dealing with disputes that had arisen between the leaders in Virginia.

Tangier

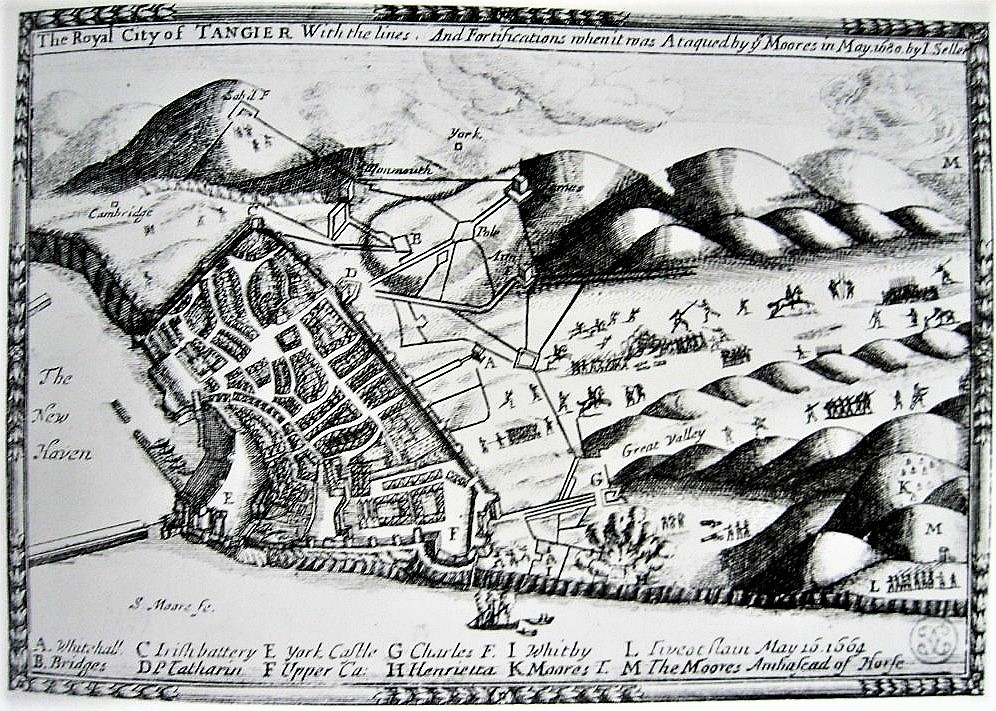

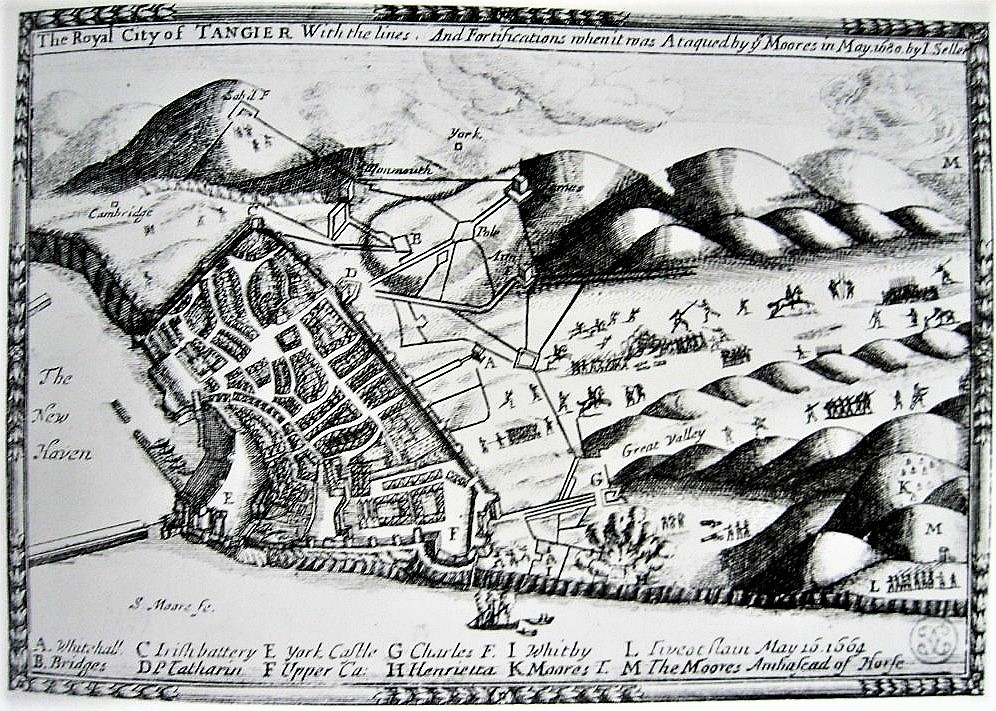

By 1680 Charles II had threatened to give up

By 1680 Charles II had threatened to give up Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the cap ...

, which costly for parliament to maintain and difficult to defend, as in order to protect the town and harbour from attack, the perimeter had to be increased. A number of outwork

An outwork is a minor fortification built or established outside the principal fortification limits, detached or semidetached. Outworks such as ravelins, lunettes (demilunes), flèches and caponiers to shield bastions and fortification curtains ...

s were built, but a siege in 1680 showed that they could be successfully overcome. In 1683, Charles gave Admiral Lord Dartmouth secret orders to abandon Tangier. Dartmouth was to level the fortifications, destroy the harbour, and evacuate the troops. That August, Dartmouth sailed from Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

. The forts and walls were mined, and on 5 February 1684, Tangier was evacuated, leaving the town in ruins.

In 1683, after Berry was appointed to command the HMS ''Henrietta'', a 50-gun third rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third r ...

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

, he became the vice-admiral of the fleet sent to the Mediterranean to evacuate the garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

and destroy the harbour and defensive works.

Sinking of HMS ''Gloucester'' (1682)

In April 1682, HMS ''Gloucester'' was due to be deployed, along with five other ships, toTangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the cap ...

via Ireland, when Berry was appointed to command the ship, and was assigned to transport the Duke of York (the future King James II of England) and his party from Sheerness

Sheerness () is a town and civil parish beside the mouth of the River Medway on the north-west corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 11,938, it is the second largest town on the island after the nearby town ...

to Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by '' Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

. James intended to settle his affairs as Lord High Commissioner to the Parliament of Scotland

The Lord High Commissioner to the Parliament of Scotland was the monarch of Scotland's's personal representative to the Parliament of Scotland. From the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of England in 1603, a Lord High Commissio ...

, and collect his pregnant wife Mary of Modena

Mary of Modena ( it, Maria Beatrice Eleonora Anna Margherita Isabella d'Este; ) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland as the second wife of James II and VII. A devout Roman Catholic, Mary married the widower James, who was then the young ...

(along with his daughter Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

from his previous marriage), before returning from Edinburgh to London and taking up residence at his brother Charles’s court.

''Gloucester'', together with the ''Ruby'', '' Happy Return'', ''Lark

Larks are passerine birds of the family Alaudidae. Larks have a cosmopolitan distribution with the largest number of species occurring in Africa. Only a single species, the horned lark, occurs in North America, and only Horsfield's bush lark occu ...

'', '' Dartmouth'' and ''Pearl'', and the royal yacht

A royal yacht is a ship used by a monarch or a royal family. If the monarch is an emperor the proper term is imperial yacht. Most of them are financed by the government of the country of which the monarch is head. The royal yacht is most often c ...

s ''Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

'', ''Katherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and Catherina, other variations are feminine Given name, names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria ...

'', ''Charlotte

Charlotte ( ) is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont (United States), Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, Meckl ...

'' and ''Kitchen

A kitchen is a room or part of a room used for cooking and food preparation in a dwelling or in a commercial establishment. A modern middle-class residential kitchen is typically equipped with a stove, a sink with hot and cold running water, a ...

'', convened on 3 May. The fleet left the Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

coast the following day, watched by Charles and members of the royal court. Bad weather forced the ''Gloucester'' to moor up during the first night. As a signal for the fleet to drop anchor, she fired a gun, but three ships, misinterpreting the signal, sailed out to sea, and never re-joined the fleet. On the second evening, a dispute arose between James, several officers, and the ship's pilot, about the correct course to take. James settled the matter when he decided upon a middle course. On the night of 5/6 May 1682, ''Gloucester'' struck the Leman and Ower sandbank at low tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables can ...

, about off Great Yarmouth

Great Yarmouth (), often called Yarmouth, is a seaside town and unparished area in, and the main administrative centre of, the Borough of Great Yarmouth in Norfolk, England; it straddles the River Yare and is located east of Norwich. A pop ...

. Less than an hour later, she sank.

Partly through Berry's efforts and determination to stay with his ship until the end, the ship's boats were lowered down, enabling the Duke of York and some of his courtiers and advisors to reach the safety of the other ships. Boats managed to rescue more people, and many were saved, but between 130 to 250 sailors and passengers lost their lives. Berry wrote a detailed account of the disaster soon afterwards.

Other posts

Berry was from 1684 on service as a Navy commissioner. He was governor of Deal Castle from June 1674, and became a commissioner forVirginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

in 1677.

Glorious Revolution

In 1688, after the defection of Lord Dartmouth, Berry commanded the fleet deployed against William of Orange when he moved against theStuart king

Stuart Patrick King (22 April 1906 – 28 February 1943) was an Australian sportsman who played first-class cricket for Victoria and Australian rules football for Victorian Football League club St Kilda.

Family

The son of David James King ( ...

, James II.

Marriage

Berry married Rebecca Ventris of Granhams,Great Shelford

Great Shelford is a village located approximately to the south of Cambridge, in the county of Cambridgeshire, in eastern England. In 1850 Great Shelford parish contained bisected by the river Cam. The population in 1841 was 803 people. By 2001 ...

, Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and North ...

, as identified from the arms of Ventris shown on her monument in a church in Stepney

Stepney is a district in the East End of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. The district is no longer officially defined, and is usually used to refer to a relatively small area. However, for much of its history the place name appl ...

. She may have been a sister of Sir Peyton Ventris

Sir Peyton Ventris (November 1645 – 6 April 1691) was an English judge and politician, the first surviving son of Edward Ventris (died 1649) of the manor of Granhams (now Granhams Close), Great Shelford, Cambridgeshire, although he was born ...

, the eldest surviving son of the barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

Edward Ventris. The marriage was without progeny.

Final years

Sheerness Dockyard

Sheerness Dockyard also known as the Sheerness Station was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the Sheerness peninsula, at the mouth of the River Medway in Kent. It was opened in the 1660s and closed in 1960.

Location

In the Age of Sail, the R ...

over the winter of 1688–1689, but ill health had forced him to retire by 1689.

Berry died at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

on 14 February 1690, and was buried at St Dunstan's, Stepney

St Dunstan's, Stepney, is an Anglican Church which stands on a site that has been used for Christian worship for over a thousand years. It is located in Stepney High Street, in Stepney, London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

History

In about AD 952, D ...

. He commissioned his own mural monument for the church, at a cost of £150. The inscription, in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, is translated as:

"Lest thou should not know, O reader, the famed Sir John Berry of Devon, with dignity of a knight, not just ruler of the sea (as well know too the Barbaries) having gained from King and Country well-deserved great glory on account of matters happily conducted, satiated with the glory of fame, after many victories brought home, as with others, was not able to defeat theThe monument survives, but no longer the pristine white of Prince's description but covered with a yellowish-brown patina. No trace survives of the arms described by Prince. HisFates The Fates are a common motif in European polytheism, most frequently represented as a trio of goddesses. The Fates shape the destiny of each human, often expressed in textile metaphors such as spinning fibers into yarn, or weaving threads on a .... He died 14 February 1689, was baptised 7 January 1635"''

will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

, dated 2 February 1688, mentions his wife Rebecca, who married 10 months after Berry's death.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * *External links

Sir John Berry (1635-1690/91)

from the Three Decks website {{DEFAULTSORT:Berry, John 1635 births 1690 deaths Military personnel from Devon Royal Navy admirals People of British North America Captains of Deal Castle Year of death unknown 17th-century Royal Navy personnel People from North Devon (district)