Sillaginidae on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Sillaginidae, commonly known as the smelt-whitings, whitings, sillaginids, sand borers and sand-smelts, are a

*Family SILLAGINIDAE

**Genus ''

*Family SILLAGINIDAE

**Genus ''

ImageSize = width:1000px height:auto barincrement:15px

PlotArea = left:10px bottom:50px top:10px right:10px

Period = from:-65.5 till:10

TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal

ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:5 start:-65.5

ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:1 start:-65.5

TimeAxis = orientation:hor

AlignBars = justify

Colors =

#legends

id:CAR value:claret

id:ANK value:rgb(0.4,0.3,0.196)

id:HER value:teal

id:HAD value:green

id:OMN value:blue

id:black value:black

id:white value:white

id:cenozoic value:rgb(0.54,0.54,0.258)

id:paleogene value:rgb(0.99,0.6,0.32)

id:paleocene value:rgb(0.99,0.65,0.37)

id:eocene value:rgb(0.99,0.71,0.42)

id:oligocene value:rgb(0.99,0.75,0.48)

id:neogene value:rgb(0.999999,0.9,0.1)

id:miocene value:rgb(0.999999,0.999999,0)

id:pliocene value:rgb(0.97,0.98,0.68)

id:quaternary value:rgb(0.98,0.98,0.5)

id:pleistocene value:rgb(0.999999,0.95,0.68)

id:holocene value:rgb(0.999,0.95,0.88)

BarData=

bar:eratop

bar:space

bar:periodtop

bar:space

bar:NAM1

bar:NAM2

bar:space

bar:period

bar:space

bar:era

PlotData=

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:M mark:(line,black) width:25

shift:(7,-4)

bar:periodtop

from: -65.5 till: -55.8 color:paleocene text:

The Sillaginidae are distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific region, ranging from the west coast of Africa to Japan and

The Sillaginidae are distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific region, ranging from the west coast of Africa to Japan and

The sillaginids are some of the most important commercial fishes in the Indo-Pacific region, with a few species making up the bulk of whiting catches. Their high numbers, coupled with their highly regarded

The sillaginids are some of the most important commercial fishes in the Indo-Pacific region, with a few species making up the bulk of whiting catches. Their high numbers, coupled with their highly regarded

A small number of sillaginids have large enough populations to allow an entire fishery to be based around them, with King George whiting, northern whiting, Japanese whiting, sand whiting and school whiting the major species. There have been no reliable estimates of catches for the entire family, as catch

A small number of sillaginids have large enough populations to allow an entire fishery to be based around them, with King George whiting, northern whiting, Japanese whiting, sand whiting and school whiting the major species. There have been no reliable estimates of catches for the entire family, as catch

Colour photographs of many Sillaginid species

{{Taxonbar, from=Q133321 Fish of the Pacific Ocean Commercial fish Marine fish families

family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

of benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from ancient Greek, βένθος (bénthos), meaning "t ...

coastal

The coast, also known as the coastline or seashore, is defined as the area where land meets the ocean, or as a line that forms the boundary between the land and the coastline. The Earth has around of coastline. Coasts are important zones in n ...

marine fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of li ...

in the order Perciformes

Perciformes (), also called the Percomorpha or Acanthopteri, is an order or superorder of ray-finned fish. If considered a single order, they are the most numerous order of vertebrates, containing about 41% of all bony fish. Perciformes means ...

. The smelt-whitings inhabit a wide region covering much of the Indo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is a vast biogeographic region of Earth.

In a narrow sense, sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific or Indo-Pacific Asia, it comprises the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and the ...

, from the west coast of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

east to Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

and south to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

. The family comprises only five genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

and 35 species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

, of which a number are dubious, with the last major revision of the family in 1992 unable to confirm the validity of a number of species. They are elongated, slightly compressed fish, often light brown to silver in colour, with a variety of markings and patterns on their upper bodies. The Sillaginidae are not related to a number of fishes commonly called ' whiting' in the Northern Hemisphere

The Northern Hemisphere is the half of Earth that is north of the Equator. For other planets in the Solar System, north is defined as being in the same celestial hemisphere relative to the invariable plane of the solar system as Earth's Nort ...

, including the fish originally called whiting, ''Merlangius merlangus

''Merlangius merlangus'', commonly known as Whiting or merling, is an important food fish in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean and the northern Mediterranean, western Baltic, and Black Sea. In Anglophonic countries outside the Whiting's natural ...

''.

The smelt-whitings are mostly inshore

A shore or a shoreline is the fringe of land at the edge of a large body of water, such as an ocean, sea, or lake. In physical oceanography, a shore is the wider fringe that is geologically modified by the action of the body of water past a ...

fishes that inhabit sandy, silty, and muddy substrates on both low- and high-energy environments ranging from protected tidal flat

Mudflats or mud flats, also known as tidal flats or, in Ireland, slob or slobs, are coastal wetlands that form in intertidal areas where sediments have been deposited by tides or rivers. A global analysis published in 2019 suggested that tidal fl ...

s and estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environment ...

to surf zone

As ocean surface waves approach shore, they get taller and break, forming the foamy, bubbly surface called ''surf''. The region of breaking waves defines the surf zone, or breaker zone. After breaking in the surf zone, the waves (now reduced i ...

s. A few species predominantly live offshore on deep sand shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

s and reef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral or similar relatively stable material, lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic processes— deposition of sand, wave erosion planing down rock out ...

s, although the larvae and juvenile phases of most species return to inshore grounds, where they spend the first few years of their lives. Smelt-whitings are benthic carnivores

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

that prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

predominantly on polychaete

Polychaeta () is a paraphyletic class (biology), class of generally marine invertebrate, marine annelid worms, common name, commonly called bristle worms or polychaetes (). Each body segment has a pair of fleshy protrusions called parapodia that ...

s, a variety of crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

s, mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

s, and to a lesser extent echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the sea ...

s and fish, feeding by detecting vibrations emitted by their prey.

The family is highly important to fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life; or more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a. fishing ground). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, both ...

throughout the Indo-Pacific, with species such as the northern whiting

The northern whiting (''Sillago sihama''), also known as the silver whiting and sand smelt, is a marine fish, the most widespread and abundant member of the smelt-whiting family Sillaginidae. The northern whiting was the first species of sillagin ...

, Japanese whiting

The Japanese whiting, ''Sillago japonica'', (also known as the Japanese sillago or Shiro-gisu) is a common species of coastal marine fish belonging to the smelt-whiting family, Sillaginidae. As suggested by its name, the Japanese whiting was fir ...

, and King George whiting

The King George whiting (''Sillaginodes punctatus''), also known as the spotted whiting or spotted sillago, is a coastal marine fish of the smelt-whitings family Sillaginidae. The King George whiting is endemic to Australia, inhabiting the s ...

forming the basis of major fisheries throughout their range. Many species are also of major importance to small subsistence

A subsistence economy is an economy directed to basic subsistence (the provision of food, clothing, shelter) rather than to the market. Henceforth, "subsistence" is understood as supporting oneself at a minimum level. Often, the subsistence econo ...

fisheries, while others are little more than occasional bycatch

Bycatch (or by-catch), in the fishing industry, is a fish or other marine species that is caught unintentionally while fishing for specific species or sizes of wildlife. Bycatch is either the wrong species, the wrong sex, or is undersized or juve ...

. Smelt-whitings are caught by a number of methods, including trawling

Trawling is a method of fishing that involves pulling a fishing net through the water behind one or more boats. The net used for trawling is called a trawl. This principle requires netting bags which are towed through water to catch different spec ...

, seine net

Seine fishing (or seine-haul fishing; ) is a method of fishing that employs a surrounding net, called a seine, that hangs vertically in the water with its bottom edge held down by weights and its top edge buoyed by floats. Seine nets can be de ...

s, and cast nets. In Australia and Japan in particular, members of the family are often highly sought by recreational fishermen who also seek the fish for their prized flesh.

Taxonomy

The first species of sillaginid to bescientifically described

A species description is a formal description of a newly discovered species, usually in the form of a scientific paper. Its purpose is to give a clear description of a new species of organism and explain how it differs from species that have be ...

was '' Sillago sihama'', by Peter Forsskål

Peter Forsskål, sometimes spelled Pehr Forsskål, Peter Forskaol, Petrus Forskål or Pehr Forsskåhl (11 January 1732 – 11 July 1763) was a Swedish-speaking Finnish explorer, orientalist, naturalist, and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus.

Earl ...

in 1775, who initially referred the species to a genus of hardyhead, ''Atherina

''Atherina'' is a genus of fish of silverside family Atherinidae, found in the temperate and tropic zones. Up to 15 cm long, they are widespread in the Mediterranean, Black Sea, Sea of Azov in lagoons and estuaries. It comes to the low stre ...

''. It was not until 1817 that the type genus ''Sillago'' was created by Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

based on his newly described species ''Sillago acuta'', which was later found to be a junior synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linna ...

of ''S. sihama'' and subsequently discarded. Cuvier continued to describe species of sillaginid with the publishing of his ichthyological work '' Histoire Naturelle des Poissons'' with Achille Valenciennes

Achille Valenciennes (9 August 1794 – 13 April 1865) was a French zoologist.

Valenciennes was born in Paris, and studied under Georges Cuvier. His study of parasitic worms in humans made an important contribution to the study of parasitology. ...

in 1829, also erecting the genus ''Sillaginodes

The King George whiting (''Sillaginodes punctatus''), also known as the spotted whiting or spotted sillago, is a coastal marine fish of the smelt-whitings family Sillaginidae. The King George whiting is endemic to Australia, inhabiting the so ...

'' in this work. The species ''Cheilodipterus panijus'' was named in 1822 by Francis Buchanan-Hamilton and was subsequently reexamined by Theodore Gill

Theodore Nicholas Gill (March 21, 1837 – September 25, 1914) was an American ichthyologist, mammalogist, malacologist and librarian.

Career

Born and educated in New York City under private tutors, Gill early showed interest in natural histor ...

in 1861, leading to the creation of the monotypic

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unispec ...

genus ''Sillaginopsis

The Gangetic whiting, ''Sillaginopsis panijus'' (also known as the flathead sillago), is a species of inshore marine and estuarine fish of the smelt-whiting family, Sillaginidae. It is the most distinctive Asian member of the family due to it ...

''. John Richardson was the first to propose that ''Sillago'', the only genus of sillaginid then recognised, be assigned to their own taxonomic family, "Sillaginidae" (used interchangeably with 'Sillaginoidae'), at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

The British Science Association (BSA) is a charity and learned society founded in 1831 to aid in the promotion and development of science. Until 2009 it was known as the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BA). The current Chie ...

. There were, however, many differing opinions on the relationships of the "sillaginoids", leading to the naturalists of the day continually revising the position of the five genera, placing in them in a number of families. The first review of the sillaginid fishes was Gill's 1861 work "Synopsis of the sillaginoids", in which the name "Sillaginidae" was popularized and expanded on to include ''Sillaginodes'' and ''Sillaginopsis'', however the debate on the placement of the family remained controversial.

In the years after Gill's paper was published, over 30 'new' species of sillaginids were reported and scientifically described, many of which were synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

s of previously described species, with similarity between species, as well as minor geographical variation confounding taxonomist

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon) and these groups are given ...

s. In 1985, Roland McKay of the Queensland Museum

The Queensland Museum is the state museum of Queensland, dedicated to natural history, cultural heritage, science and human achievement. The museum currently operates from its headquarters and general museum in South Brisbane with specialist mu ...

published a comprehensive review of the family to resolve these relationships, although a number of species are still listed as doubtful, with McKay unable to locate the holotypes. Along with the review of previously described species, McKay described an additional seven species, a number of which he described as subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

. After this 1985 paper, additional specimen

Specimen may refer to:

Science and technology

* Sample (material), a limited quantity of something which is intended to be similar to and represent a larger amount

* Biological specimen or biospecimen, an organic specimen held by a biorepository ...

s came to light, proving that all the subspecies he had identified were individual species. In 1992, McKay published a synopsis of the Sillaginidae for the FAO

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)french: link=no, Organisation des Nations unies pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture; it, Organizzazione delle Nazioni Unite per l'Alimentazione e l'Agricoltura is an intern ...

, in which he elevated these subspecies to full species status.

The name "Sillaginidae" was derived from Cuvier's ''Sillago'', which itself takes its name from a locality in Australia, possibly Sillago reef off the coast of Queensland. The term "sillago" is derived from the Greek term ''syllego'', which means "to meet".

Classification

The following is a comprehensive list of the 35 knownextant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

species of sillaginids, with a number of the species still in doubt due to the loss of the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

specimen. This classification follows ''Fishbase

FishBase is a global species database of fish species (specifically finfish). It is the largest and most extensively accessed online database on adult finfish on the web.

'', which itself is based on McKay's last revision of the family.

Sillaginodes

The King George whiting (''Sillaginodes punctatus''), also known as the spotted whiting or spotted sillago, is a coastal marine fish of the smelt-whitings family Sillaginidae. The King George whiting is endemic to Australia, inhabiting the so ...

''

*** '' Sillaginodes punctatus'' Cuvier, 1829 (King George whiting)

**Genus ''Sillaginopodys

The club-foot whiting, ''Sillaginopodys chondropus'', (also known as the Horrelvoet sillago), the only member of the genus ''Sillaginopodys'', is a coastal marine fish of the smelt whiting family Sillaginidae that inhabits a wide range includin ...

''

*** '' Sillaginopodys chondropus'' Bleeker Bleeker is a Dutch occupational surname. Bleeker is an old spelling of ''(linnen)bleker'' ("linen bleacher").Sillaginops

The large-scale whiting (''Sillaginops macrolepis'') the only member of the genus ''Sillaginops'', is a poorly understood species of coastal marine fish of the smelt- whiting family Sillaginidae. First described in 1859, the large-scale whitin ...

''

*** '' Sillaginops macrolepis'' Bleeker Bleeker is a Dutch occupational surname. Bleeker is an old spelling of ''(linnen)bleker'' ("linen bleacher").Sillaginopsis

The Gangetic whiting, ''Sillaginopsis panijus'' (also known as the flathead sillago), is a species of inshore marine and estuarine fish of the smelt-whiting family, Sillaginidae. It is the most distinctive Asian member of the family due to it ...

''

*** '' Sillaginopsis panijus'' Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilt ...

, 1822 (Gangetic whiting)

**Genus ''Sillago

''Sillago'' is a genus of fish in the family Sillaginidae and the only non-monotypic genus in the family. Distinguishing the species can be difficult, with many similar in appearance and colour, forcing the use of swim bladder morphology as a d ...

''

*** ''Sillago aeolus

The oriental trumpeter whiting, ''Sillago aeolus'', is a widely distributed species of benthic inshore fish in the smelt-whiting family. The species ranges from east Africa to Japan, inhabiting much if the southern Asian and Indonesian coastline ...

'' D. S. Jordan & Evermann, 1902 (Oriental sillago)

*** '' Sillago analis'' Whitley, 1943 (Golden-lined sillago)

*** '' Sillago arabica'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

& McCarthy, 1989 (Arabian sillago)

*** '' Sillago argentifasciata'' C. Martin & H. R. Montalban, 1935 (Silver-banded sillago)

*** '' Sillago asiatica'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

, 1982 (Asian sillago)

*** '' Sillago attenuata'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

, 1985 (Slender sillago)

*** '' Sillago bassensis'' G. Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in nat ...

, 1829 (Western school sillago)

*** ''Sillago boutani

Boutan's whiting, ''Sillago boutani'', is a poorly understood species of coastal marine fish of the smelt-whiting family Sillaginidae that inhabits the waters of the Gulf of Tonkin and south eastern China. Like most sillaginids, the species in ...

'' Pellegrin, 1905 (Boutan's sillago)

*** ''Sillago burrus

The western trumpeter whiting, ''Sillago burrus'', is a species of marine fish of the smelt whiting family Sillaginidae that is commonly found along the northern coast of Australia and in southern Indonesia and New Guinea. As its name suggests ...

'' Richardson

Richardson may refer to:

People

* Richardson (surname), an English and Scottish surname

* Richardson Gang, a London crime gang in the 1960s

* Richardson Dilworth, Mayor of Philadelphia (1956-1962)

Places Australia

* Richardson, Australian Cap ...

, 1842 (Western trumpeter sillago)

*** '' Sillago caudicula'' Kaga, Imamura, Nakaya, 2010

*** '' Sillago ciliata'' G. Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in nat ...

, 1829 (Sand sillago)

*** '' Sillago erythraea'' G. Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in nat ...

, 1829

*** '' Sillago flindersi'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

, 1985 (Flinders' sillago)

*** '' Sillago indica'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

, Dutt & Sujatha, 1985 (Indian sillago)

*** '' Sillago ingenuua'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

, 1985 (Bay sillago)

*** '' Sillago intermedius'' Wongratana, 1977 (Intermediate sillago)

*** '' Sillago japonica'' Temminck

Coenraad Jacob Temminck (; 31 March 1778 – 30 January 1858) was a Dutch aristocrat, zoologist and museum director.

Biography

Coenraad Jacob Temminck was born on 31 March 1778 in Amsterdam in the Dutch Republic. From his father, Jacob Temmin ...

& Schlegel

Schlegel is a German occupational surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Anthony Schlegel (born 1981), former American football linebacker

* August Wilhelm Schlegel (1767–1845), German poet, older brother of Friedrich

* Brad Schlege ...

, 1843 (Japanese sillago)

*** '' Sillago lutea'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

, 1985 (Mud sillago)

*** '' Sillago maculata'' Quoy & Gaimard

Joseph Paul Gaimard (31 January 1793 – 10 December 1858) was a French naval surgeon and naturalist.

Biography

Gaimard was born at Saint-Zacharie on January 31, 1793. He studied medicine at the naval medical school in Toulon, subsequent ...

, 1824 (Trumpeter sillago)

*** '' Sillago megacephalus'' S. Y. Lin, 1933 (Large-headed sillago)

*** '' Sillago microps'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

, 1985 (Small-eyed sillago)

*** '' Sillago nierstraszi'' Hardenberg

Hardenberg (; nds-nl, Haddenbarreg or '' 'n Arnbarg'') is a city and municipality in the province of Overijssel, Eastern Netherlands. The municipality of Hardenberg has a population of about 60,000, with about 19,000 living in the city. It recei ...

, 1941 (Rough sillago)

*** '' Sillago parvisquamis'' T. N. Gill, 1861 (Small-scale sillago)

*** '' Sillago robusta'' Stead, 1908 (Stout sillago)

*** '' Sillago schomburgkii'' W. K. H. Peters, 1864 (Yellowfin sillago)

*** '' Sillago sihama'' Forsskål, 1775 (Silver sillago)

*** ''Sillago sinica

The Chinese sillago (''Sillago sinica'') is a species of recently described inshore marine fish in the smelt whiting family Sillaginidae. The species is known only to inhabit the coastal waters of China, primarily in estuarine tidal flats near W ...

'' T. X. Gao, D. P. Ji, Y. S. Xiao, T. Q. Xue, Yanagimoto & Setoguma, 2011 (Chinese sillago)

*** '' Sillago soringa'' Dutt & Sujatha, 1982 (Soringa sillago)

*** '' Sillago suezensis'' Golani, R. Fricke & Tikochinski, 2013 Golani, D., Fricke, R. & Tikochinski, Y. (2013): ''Sillago suezensis'', a new whiting from the northern Red Sea, and status of ''Sillago erythraea'' Cuvier (Teleostei: Sillaginidae). ''Journal of Natural History, 48 (7-8) 014 413-428.''

*** '' Sillago vincenti'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

, 1980 (Vincent's sillago)

*** '' Sillago vittata'' McKay

McKay, MacKay or Mackay is a Scottish / Irish surname. The last phoneme in the name is traditionally pronounced to rhyme with 'eye', but in some parts of the world this has come to rhyme with 'hey'. In Scotland, it corresponds to Clan Mackay. Not ...

, 1985 (Banded sillago)

Evolution

A number of sillaginids have been identified from thefossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved in ...

, with the lower Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

marking the first appearance of the family. The family is thought to have evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

in the Tethys Sea

The Tethys Ocean ( el, Τηθύς ''Tēthús''), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean that covered most of the Earth during much of the Mesozoic Era and early Cenozoic Era, located between the ancient continents ...

of central Australia, before colonizing southern Australia during the upper Eocene after a seaway broke through south of Tasmania. During the Oligocene, the family spread to the north and south, occupying a much more extensive range than their current Indo-Pacific distribution. Fossils suggest the sillaginids ranged as far north as Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, and as far south as New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, found in shallow water sedimentary

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic matter, organic particles at Earth#Surface, Earth's surface, followed by cementation (geology), cementation. Sedimentati ...

deposits along with other species of extant genera.

At least eight fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

sillaginid species have been found, all of which are believed to be of the genus ''Sillago'' based on the only remains found, otolith

An otolith ( grc-gre, ὠτο-, ' ear + , ', a stone), also called statoconium or otoconium or statolith, is a calcium carbonate structure in the saccule or utricle of the inner ear, specifically in the vestibular system of vertebrates. The sa ...

s. Only one species of extant sillaginid, ''Sillago maculata'', has been found in the fossil record, and this was in very recent Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

s.

*''Sillago campbellensis'' (Schwarzhans, 1985) Australia, Miocene

*''Sillago hassovicus'' (Koken, 1891) Poland, Middle Miocene

*''Sillago maculata'' (Quoy and Gaimard, 1824) New Zealand, Middle Pleistocene

*''Sillago mckayi'' (Schwarzhans, 1985) Australia, Oligocene

*''Sillago pliocaenica'' (Stinton, 1952) Australia, Pliocene

*''Sillago recta'' (Schwarzhans, 1980) New Zealand, Upper Miocene

*''Sillago schwarzhansi'' (Steurbaut, 1984) France, Lower Miocene

*''Sillago ventriosus'' (Steurbaut, 1984) France, Upper Oligocene

Timeline of genera

Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), E ...

from: -55.8 till: -33.9 color:eocene text:Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

from: -33.9 till: -23.03 color:oligocene text:Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but the ...

from: -23.03 till: -5.332 color:miocene text:Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

from: -5.332 till: -2.588 color:pliocene text: Plio.

from: -2.588 till: -0.0117 color:pleistocene text:Pleist.

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

from: -0.0117 till: 0 color:holocene text: H.

bar:eratop

from: -65.5 till: -23.03 color:paleogene text:Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; British English, also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period, geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million yea ...

from: -23.03 till: -2.588 color:neogene text:Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

from: -2.588 till: 0 color:quaternary text: Q.

PlotData=

align:left fontsize:M mark:(line,white) width:5 anchor:till align:left

color:oligocene bar:NAM1 from: -33.9 till: 0 text: Sillago

''Sillago'' is a genus of fish in the family Sillaginidae and the only non-monotypic genus in the family. Distinguishing the species can be difficult, with many similar in appearance and colour, forcing the use of swim bladder morphology as a d ...

color:pliocene bar:NAM2 from: -5.332 till: 0 text: Sillaginoides

PlotData=

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:M mark:(line,black) width:25

bar:period

from: -65.5 till: -55.8 color:paleocene text:Paleocene

The Paleocene, ( ) or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), E ...

from: -55.8 till: -33.9 color:eocene text:Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

from: -33.9 till: -23.03 color:oligocene text:Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but the ...

from: -23.03 till: -5.332 color:miocene text:Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

from: -5.332 till: -2.588 color:pliocene text: Plio.

from: -2.588 till: -0.0117 color:pleistocene text:Pleist.

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

from: -0.0117 till: 0 color:holocene text: H.

bar:era

from: -65.5 till: -23.03 color:paleogene text:Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; British English, also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period, geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million yea ...

from: -23.03 till: -2.588 color:neogene text:Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

from: -2.588 till: 0 color:quaternary text: Q.

Phylogeny

The relationships of the Sillaginidae are poorly known, with very similar morphological characteristics and a lack of genetic studies restricting the ability to performcladistic

Cladistics (; ) is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups (" clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is typically shared derived char ...

analyses on the family. Being the fossil sillaginids are based on the comparison of fossil otoliths, with no other type of remains found thus far, this also prevents the reconstruction of the evolution of the family through fossil species. While the position of the Sillaginidae in the order Perciformes is firmly established due to a number of synapomorphies

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to have ...

shared with other members of the order, no sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

has been established for the family. The current taxonomic

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

status of the family is thought to represent a basic picture of the group's phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

, with McKay further dividing the genus ''Sillago'' into three subgenera

In biology, a subgenus (plural: subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between t ...

based on shared morphological characters of the swimbladder. The genera ''Sillaginodes'' and ''Sillaginopsis'' have the most plesiomorphic

In phylogenetics, a plesiomorphy ("near form") and symplesiomorphy are synonyms for an ancestral character shared by all members of a clade, which does not distinguish the clade from other clades.

Plesiomorphy, symplesiomorphy, apomorphy, and ...

characteristics; being monotypic, and distinct from ''Sillago''. ''Sillago'' is further divided into three subgenera based primarily on swim bladder morphology; ''Sillago'', ''Parasillago'' and ''Sillaginopodys'', which also represent evolutionary relationships. Whilst genetic studies have not been done on the family, they have been used to establish the relationship of what were thought to be various subspecies of school whiting, ''S. bassensis'' and ''S. flindersi''.Dixon, P.I., Crozier, R.H., Black, M. & Church, A. (1987): Stock identification and discrimination of commercially important whitings in Australian waters using genetic criteria (FIRTA 83/16). ''Centre for Marine Science, University of New South Wales. 69 p. Appendices 1-10.'' Furthermore, morphological data suggests a number of Australian species diverged very recently during the last glacial maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

, which caused land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and Colonisation (biology), colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regre ...

s to isolate population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction using a ...

s of fish. The two aforementioned species of school whiting, ''S. maculata'' and ''S. burrus'', and ''S. ciliata'' and ''S. analis'' are all thought to be products of such a process, although only the school whiting have anything other than similar morphology as evidence of this process.

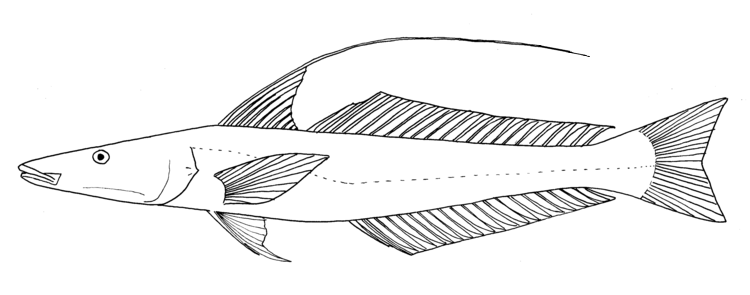

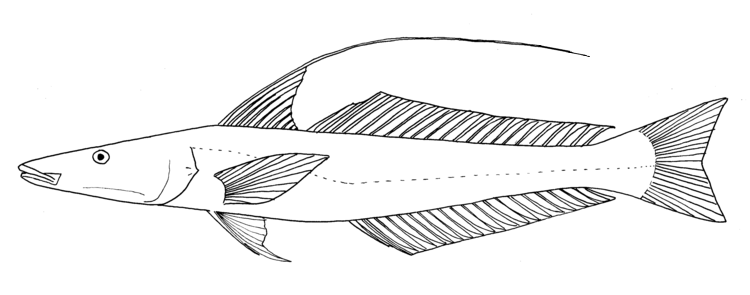

Morphology

The Sillaginidae are medium-sized fishes which grow to an average of around 20 cm and around 100 g, although the largest member of the family, the King George whiting is known to reach 72 cm and 4.8 kg inweight

In science and engineering, the weight of an object is the force acting on the object due to gravity.

Some standard textbooks define weight as a Euclidean vector, vector quantity, the gravitational force acting on the object. Others define weigh ...

. The body shape and fin placement of the family is quite similar to most of the members of the order Perciformes. Their bodies are elongate, slightly compressed, with a head that tapers toward a terminal mouth

In animal anatomy, the mouth, also known as the oral cavity, or in Latin cavum oris, is the opening through which many animals take in food and issue vocal sounds. It is also the cavity lying at the upper end of the alimentary canal, bounded on ...

. The mouth has a band of brush-like teeth with canine teeth

In mammalian oral anatomy, the canine teeth, also called cuspids, dog teeth, or (in the context of the upper jaw) fangs, eye teeth, vampire teeth, or vampire fangs, are the relatively long, pointed teeth. They can appear more flattened howeve ...

present only in the upper jaw

The jaw is any opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term ''jaws'' is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serv ...

of ''Sillaginopsis''. The cranial sensory system of the family is well developed above and laterally, with the lower jaw having a pair of small pores behind which is a median pit containing a pore on each side. On each side of the elongate head the operculum has a short sharp spine. They have two true dorsal fin

A dorsal fin is a fin located on the back of most marine and freshwater vertebrates within various taxa of the animal kingdom. Many species of animals possessing dorsal fins are not particularly closely related to each other, though through conv ...

s; the anterior

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

one supported by 10 to 13 spines while the long rear one is held up by a single leading spine followed by 16 to 27 soft rays. The anal fin

Fins are distinctive anatomical features composed of bony spines or rays protruding from the body of a fish. They are covered with skin and joined together either in a webbed fashion, as seen in most bony fish, or similar to a flipper, as se ...

is similar to the second dorsal fin, having two small slender spines followed by 14 to 26 soft rays. Their bodies are covered in ctenoid

A fish scale is a small rigid plate that grows out of the skin of a fish. The skin of most jawed fishes is covered with these protective scales, which can also provide effective camouflage through the use of reflection and colouration, as ...

scales

Scale or scales may refer to:

Mathematics

* Scale (descriptive set theory), an object defined on a set of points

* Scale (ratio), the ratio of a linear dimension of a model to the corresponding dimension of the original

* Scale factor, a number w ...

, with the exception of the cheek

The cheeks ( la, buccae) constitute the area of the face below the eyes and between the nose and the left or right ear. "Buccal" means relating to the cheek. In humans, the region is innervated by the buccal nerve. The area between the inside ...

which may have cycloid or ctenoid scales. There is a wide variation in the amount of lateral line scales, ranging from 50 to 141. The swimbladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their current water depth w ...

in the Sillaginidae is either absent, poorly developed, or highly complex with anterior and lateral extensions that project well into the caudal region. A unique duct-like process is present from the ventral surface of the swimbladder to just before the urogenital opening

The urogenital opening is where bodily waste and reproductive fluids are expelled to the environment outside of the body cavity. In some organisms, including birds and many fish, discharge from the urological, digestive, and reproductive system ...

in most species. The presence and morphology of each species' swim bladder is often their major diagnostic feature, with McKay's three proposed subgenera based on swimbladder morphology alone. The sillaginids have only a small range of body colour

Color (American English) or colour (British English) is the visual perceptual property deriving from the spectrum of light interacting with the photoreceptor cells of the eyes. Color categories and physical specifications of color are associ ...

ings and frequently the only colour characteristics to identify between species are the arrangements of spots and bars on their upper bodies. Most of the family are a pale brown – creamy white colour, while a few species are silver all over. The undersides of the fish are usually lighter than the upper side, and the fins range from yellow to transparent

Transparency, transparence or transparent most often refer to:

* Transparency (optics), the physical property of allowing the transmission of light through a material

They may also refer to:

Literal uses

* Transparency (photography), a still, ...

, often marked by bars and spots.

Distribution and habitat

The Sillaginidae are distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific region, ranging from the west coast of Africa to Japan and

The Sillaginidae are distributed throughout the Indo-Pacific region, ranging from the west coast of Africa to Japan and Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

in the east, as well occupying as a number of small islands including New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. While they have a fairly wide distribution, the highest species densities occur along the coasts of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, Taiwan, South East Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

, the Indonesian Archipelago

The islands of Indonesia, also known as the Indonesian Archipelago ( id, Kepulauan Indonesia) or Nusantara, may refer either to the islands comprising the country of Indonesia or to the geographical groups which include its islands.

History ...

and northern Australia

The unofficial geographic term Northern Australia includes those parts of Queensland and Western Australia north of latitude 26° and all of the Northern Territory. Those local government areas of Western Australia and Queensland that lie p ...

. One species of sillaginid, ''Sillago sihama'', has been declared an invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species ad ...

to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

, passing through the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

from the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

since 1977 as part of the Lessepsian migration

The Lessepsian migration (also called Erythrean invasion) is the migration of marine species across the Suez Canal, usually from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea, and more rarely in the opposite direction. When the canal was completed in 18 ...

, becoming widespread.

Sillaginids are primarily inshore marine fishes inhabiting stretches of coastal waters, although a few species move offshore in their adult stages to deep sand banks or reefs to a maximum known depth of 180 m. All species primarily occupy sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural class of s ...

y, silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel when ...

y or mud

A MUD (; originally multi-user dungeon, with later variants multi-user dimension and multi-user domain) is a Multiplayer video game, multiplayer Time-keeping systems in games#Real-time, real-time virtual world, usually Text-based game, text-bas ...

dy substrates, often using seagrass

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants which grow in marine environments. There are about 60 species of fully marine seagrasses which belong to four families (Posidoniaceae, Zosteraceae, Hydrocharitaceae and Cymodoceaceae), all in the orde ...

or reef as cover. They commonly inhabit tidal flats, beach

A beach is a landform alongside a body of water which consists of loose particles. The particles composing a beach are typically made from rock, such as sand, gravel, shingle, pebbles, etc., or biological sources, such as mollusc shel ...

zones, broken bottoms and large areas of uniform substrate. Although the family is marine, many species inhabit estuarine

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environment ...

environments, with some such as '' Sillaginopsis panijus'' also found in the upper reaches of the estuary. Each species often occupies a specific niche

Niche may refer to:

Science

*Developmental niche, a concept for understanding the cultural context of child development

*Ecological niche, a term describing the relational position of an organism's species

*Niche differentiation, in ecology, the ...

to avoid competition

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indivi ...

with co-occurring sillaginids, often inhabiting a specific substrate type, depth, or making use of surf zones and estuaries. The juveniles often show distinct changes in habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

preference as they mature, often moving to deeper waters. No members of the family are known to undergo migratory movements, and have been shown to be relatively weak swimmers, relying on currents to disperse juveniles.

Biology

Diet and feeding

The smelt-whitings are benthiccarnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

s, with all of the species whose diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

s have been studied showing similar prey preferences. Smelt-whitings have well developed chemosensory

A chemoreceptor, also known as chemosensor, is a specialized sensory receptor which transduces a chemical substance ( endogenous or induced) to generate a biological signal. This signal may be in the form of an action potential, if the chemorecep ...

systems compared to many other teleost fishes, with high taste bud

Taste buds contain the taste receptor cells, which are also known as gustatory cells. The taste receptors are located around the small structures known as lingual papillae, papillae found on the upper surface of the tongue, soft palate, upper e ...

densities on the outside tip of the snout. The turbulence and turbidity of the environment appear to determine how well developed the sensory systems are in an individual. Studies from the waters of Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

, Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and Australia have shown that polychaetes

Polychaeta () is a paraphyletic class of generally marine annelid worms, commonly called bristle worms or polychaetes (). Each body segment has a pair of fleshy protrusions called parapodia that bear many bristles, called chaetae, which are mad ...

, a variety of crustaceans, molluscs and to a lesser extent echinoderms and fish are the predominant prey items of the family. Commonly taken crustaceans include decapods

The Decapoda or decapods (literally "ten-footed") are an order of crustaceans within the class Malacostraca, including many familiar groups, such as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp and prawns. Most decapods are scavengers. The order is estim ...

, copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat (ecology), habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthos, benthic (living on the ocean floor) ...

s and isopod

Isopoda is an order of crustaceans that includes woodlice and their relatives. Isopods live in the sea, in fresh water, or on land. All have rigid, segmented exoskeletons, two pairs of antennae, seven pairs of jointed limbs on the thorax, an ...

s, while the predominant molluscs taken are various species of bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

s, especially the unprotected siphon filters that protrude from the shells. In all species studied, some form of diet shift occurs as the fishes mature, often associated with a movement to deeper waters and thus to new potential prey. The juveniles often prey on planktonic

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in water (or air) that are unable to propel themselves against a current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankters. In the ocean, they provide a crucia ...

prey, with small copepods, isopods and other small crustaceans often taken. Whilst many species have a change in niche to reduce intraspecific competition

Intraspecific competition is an interaction in population ecology, whereby members of the same species compete for limited resources. This leads to a reduction in fitness for both individuals, but the more fit individual survives and is able to r ...

, there are often many species of sillaginid inhabiting a geographical area. Where this occurs, there is often definite diet differences between species, often associated with a niche specialization. The sillaginid's distinctive body shape and mouth placement is an adaptation to bottom feeding, which is the predominant method of feeding for all whiting species. All larger whiting feed by using their protrusile jaws and tube-like mouths to suck up various types of prey from in, on or above the ocean substrate, as well as using their nose as a 'plough

A plough or plow ( US; both ) is a farm tool for loosening or turning the soil before sowing seed or planting. Ploughs were traditionally drawn by oxen and horses, but in modern farms are drawn by tractors. A plough may have a wooden, iron or ...

' to dig through the substrate.

There is a large body of evidence that shows whiting do not rely on visual

The visual system comprises the sensory organ (the eye) and parts of the central nervous system (the retina containing photoreceptor cells, the optic nerve, the optic tract and the visual cortex) which gives organisms the sense of sight (the ...

cues when feeding, instead using a system based on the vibrations emitted by their prey.

Predators

Smelt-whitings are a major link in thefood chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), det ...

of most systems, and frequently fall prey to a variety of aquatic and aerial predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill th ...

s. Their main aquatic predators are a wide variety of larger fish, including both teleost

Teleostei (; Greek ''teleios'' "complete" + ''osteon'' "bone"), members of which are known as teleosts ), is, by far, the largest infraclass in the class Actinopterygii, the ray-finned fishes, containing 96% of all extant species of fish. Tel ...

s and a variety of shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachimo ...

s and rays. Marine mammal

Marine mammals are aquatic mammals that rely on the ocean and other marine ecosystems for their existence. They include animals such as seals, whales, manatees, sea otters and polar bears. They are an informal group, unified only by their reli ...

s including seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

and dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

s have been reported to have taken sillaginids as a main food source. Seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s are also another major predator of the family, with diving species such as Cormorant

Phalacrocoracidae is a family of approximately 40 species of aquatic birds commonly known as cormorants and shags. Several different classifications of the family have been proposed, but in 2021 the IOC adopted a consensus taxonomy of seven ge ...

s taking older fish in deeper waters while juvenile fish in shallow water fall prey to wading bird

245px, A flock of Dunlins and Red knots">Red_knot.html" ;"title="Dunlins and Red knot">Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflat ...

s. Sillaginids are often called 'sandborers' due to their habit of burying themselves in the substrate to avoid predators, much in the same way as they forage, by ploughing their nose into the substrate. This defense is even used against human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

fishermen, who frequently wade barefoot to feel for buried fish. The Sillaginidae are also host to a variety of well studied internal and external parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s, which are represented prominently by the groups Digenea

Digenea (Gr. ''Dis'' – double, ''Genos'' – race) is a class of trematodes in the Platyhelminthes phylum, consisting of parasitic flatworms (known as ''flukes'') with a syncytial tegument and, usually, two suckers, one ventral and one oral. ...

, Monogenea

Monogeneans are a group of ectoparasitic flatworms commonly found on the skin, gills, or fins of fish. They have a direct lifecycle and do not require an intermediate host. Adults are hermaphrodites, meaning they have both male and female reprod ...

and Myxosporea

Myxosporea is a class of microscopic parasites, belonging to the Myxozoa clade within Cnidaria. They have a complex life cycle which comprises vegetative forms in two hosts, an aquatic invertebrate (generally an annelid but sometimes a bryozoan) ...

, Copepoda

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

and Nematoda

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a broa ...

.

Reproduction

The Sillaginidae are anoviparous

Oviparous animals are animals that lay their eggs, with little or no other embryonic development within the mother. This is the reproductive method of most fish, amphibians, most reptiles, and all pterosaurs, dinosaurs (including birds), and ...

, non guarding family, whose species tend to show similar reproductive patterns to one another. Each species reaches sexual maturity

Sexual maturity is the capability of an organism to reproduce. In humans it might be considered synonymous with adulthood, but here puberty is the name for the process of biological sexual maturation, while adulthood is based on cultural definitio ...

at a slightly different age, with each sex often showing a disparity in time of maturation. Each species also spawns over a different season and the spawning season often differs within a species, usually as a function of latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

; a feature not unique to sillaginids. The proximity to shore of spawning is also different between species, as each species usually does not migrate inshore to spawn, even if the juveniles require shallow water for protection, instead relying on currents. The fecundity of sillaginids is variable, with a normal range between 50 000 – 100 000. The eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

are small (0.6 to 0.8 mm), spherical

A sphere () is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance from a given point in three-dimensional space.. That given point is the ce ...

and pelagic

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

, hatching around 20 days after fertilisation

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Proce ...

. The larva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

The ...

e are quite similar, requiring a trained developmental biologist

Developmental biology is the study of the process by which animals and plants grow and develop. Developmental biology also encompasses the biology of regeneration, asexual reproduction, metamorphosis, and the growth and differentiation of stem c ...

to identify between species. The larvae and juveniles are at the mercy of the ocean current

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of sea water generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours, s ...

s, being too weaker swimmers to actively seek out coastlines. Currents are thought to have been responsible for the distribution of mainland

Mainland is defined as "relating to or forming the main part of a country or continent, not including the islands around it egardless of status under territorial jurisdiction by an entity" The term is often politically, economically and/or dem ...

species to offshore island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

s as well as the current widespread distribution of ''Sillago sihama''. In all studied species, juveniles inhabit shallow waters in protected embayment

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a gulf, sea, sound, or bight. A cove is a small, circular bay with a narr ...

s, estuaries, tidal creek

A tidal creek or tidal channel is a narrow inlet or estuary that is affected by the ebb and flow of ocean tides. Thus, it has variable salinity and electrical conductivity over the tidal cycle, and flushes salts from inland soils. Tidal creeks a ...

s and lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') a ...

s as well as exposed surf zones, usually over tidal flats and seagrass beds. As the fish mature, they generally move to deeper waters, showing a change in diet.

Relationship to humans

The sillaginids are some of the most important commercial fishes in the Indo-Pacific region, with a few species making up the bulk of whiting catches. Their high numbers, coupled with their highly regarded

The sillaginids are some of the most important commercial fishes in the Indo-Pacific region, with a few species making up the bulk of whiting catches. Their high numbers, coupled with their highly regarded flesh

Flesh is any aggregation of soft tissues of an organism. Various multicellular organisms have soft tissues that may be called "flesh". In mammals, including humans, ''flesh'' encompasses muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as mu ...

are the reason for this, and their inshore nature also has made them popular targets for recreational fishermen in a number of countries. With overfishing

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish (i.e. fishing) from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally (i.e. the overexploitation of the fishery's existing fish stock), resulting in th ...

rife in some areas, sustainable aquaculture

Aquaculture (less commonly spelled aquiculture), also known as aquafarming, is the controlled cultivation ("farming") of aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, mollusks, algae and other organisms of value such as aquatic plants (e.g. lot ...

has allowed the commercial farming of a number of sillaginid species, as well as the use of farmed fish to restock depleted estuaries. At least one species, the Gangetic whiting, has occasionally been used in brackish water

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estua ...

aquaria.

Commercial fisheries

A small number of sillaginids have large enough populations to allow an entire fishery to be based around them, with King George whiting, northern whiting, Japanese whiting, sand whiting and school whiting the major species. There have been no reliable estimates of catches for the entire family, as catch