Scurvy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scurvy is a

File:Scorbutic tongue (cropped).jpg, A child presenting a "scorbutic tongue" due to

Vitamins are essential to the production and use of enzymes in ongoing processes throughout the human body.

Vitamins are essential to the production and use of enzymes in ongoing processes throughout the human body.

"Scott and Scurvy"

. Retrieved 2016-05-31. Scurvy occurred during the Great famine of Ireland in 1845 and also the American Civil War. In 2002, scurvy outbreaks were recorded in Afghanistan following the most intense phase of the war.

In 2009, a handwritten household book authored by a Cornishwoman in 1707 was discovered in a house in Hasfield,

In 2009, a handwritten household book authored by a Cornishwoman in 1707 was discovered in a house in Hasfield,

second edition (1757)

Lind explained the details of his clinical trial and concluded "the results of all my experiments was, that oranges and lemons were the most effectual remedies for this distemper at sea." However, the experiment and its results occupied only a few paragraphs in a work that was long and complex and had little impact. Lind himself never actively promoted lemon juice as a single 'cure'. He shared medical opinion at the time that scurvy had multiple causes – notably hard work, bad water, and the consumption of salt meat in a damp atmosphere which inhibited healthful perspiration and normal excretion – and therefore required multiple solutions. Lind was also sidetracked by the possibilities of producing a concentrated 'rob' of lemon juice by boiling it. This process destroyed the vitamin C and was therefore unsuccessful. During the 18th century, scurvy killed more British sailors than wartime enemy action. It was mainly by scurvy that during George Anson's voyage around the world he lost nearly two-thirds of his crew (1,300 out of 2,000) within the first 10 months of the voyage. The Royal Navy enlisted 184,899 sailors during the

The surgeon-in-chief of

The surgeon-in-chief of

deficiency disease

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients which adversely affects the body's tissues a ...

(state of malnutrition) resulting from a lack of vitamin C

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits, berries and vegetables. It is also a generic prescription medication and in some countries is sold as a non-prescription di ...

(ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, fatigue, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding from the skin may occur. As scurvy worsens, there can be poor wound

A wound is any disruption of or damage to living tissue, such as skin, mucous membranes, or organs. Wounds can either be the sudden result of direct trauma (mechanical, thermal, chemical), or can develop slowly over time due to underlying diseas ...

healing, personality changes, and finally death from infection or bleeding.

It takes at least a month of little to no vitamin C in the diet before symptoms occur. In modern times, scurvy occurs most commonly in people with mental disorder

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

s, unusual eating habits, alcoholism

Alcoholism is the continued drinking of alcohol despite it causing problems. Some definitions require evidence of dependence and withdrawal. Problematic use of alcohol has been mentioned in the earliest historical records. The World He ...

, and older people who live alone. Other risk factors include intestinal malabsorption and dialysis.

While many animals produce their vitamin C, humans and a few others do not. Vitamin C, an antioxidant

Antioxidants are Chemical compound, compounds that inhibit Redox, oxidation, a chemical reaction that can produce Radical (chemistry), free radicals. Autoxidation leads to degradation of organic compounds, including living matter. Antioxidants ...

, is required to make the building blocks for collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

, carnitine

Carnitine is a quaternary ammonium compound involved in metabolism in most mammals, plants, and some bacteria. In support of energy metabolism, carnitine transports long-chain fatty acids from the cytosol into mitochondria to be oxidized for f ...

, and catecholamine

A catecholamine (; abbreviated CA), most typically a 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine, is a monoamine neurotransmitter, an organic compound that has a catechol (benzene with two hydroxyl side groups next to each other) and a side-chain amine.

Cate ...

s, and assists the intestines in the absorption of iron from foods. Diagnosis is typically based on outward appearance, X-rays

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

, and improvement after treatment.

Treatment is with vitamin C supplements taken by mouth. Improvement often begins in a few days with complete recovery in a few weeks. Sources of vitamin C in the diet include citrus fruit

''Citrus'' is a genus of flowering plant, flowering trees and shrubs in the family Rutaceae. Plants in the genus produce citrus fruits, including important crops such as Orange (fruit), oranges, Mandarin orange, mandarins, lemons, grapefruits, ...

and several vegetables, including red peppers, broccoli, and tomatoes. Cooking often decreases the residual amount of vitamin C in foods.

Scurvy is rare compared to other nutritional deficiencies. It occurs more often in the developing world

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreeme ...

in association with malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients which adversely affects the body's tissues a ...

. Rates among refugees

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

are reported at 5 to 45 percent. Scurvy was described as early as the time of ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

, and historically it was a limiting factor in long-distance sea travel, often killing large numbers of people. During the Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period in European history that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid-15th) to the mid-19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the int ...

, it was assumed that 50 percent of the sailors would die of scurvy on a major trip. In long sea voyages, crews were isolated from land for extended periods and these voyages relied on large staples of a limited variety of foods and the lack of fruits, vegetables, and other foods containing vitamin C in diets of sailors resulted in scurvy.

Signs and symptoms

Early symptoms aremalaise

In medicine, malaise is a feeling of general discomfort, uneasiness or lack of wellbeing and often the first sign of an infection or other disease. It is considered a vague termdescribing the state of simply not feeling well. The word has exist ...

and lethargy

Lethargy is a state of tiredness, sleepiness, weariness, fatigue, sluggishness, or lack of energy. It can be accompanied by depression, decreased motivation, or apathy. Lethargy can be a normal response to inadequate sleep, overexertion, overw ...

. After one to three months, patients develop shortness of breath and bone pain

Bone pain (also known medically by several other names) is pain coming from a bone, and is caused by damaging stimuli. It occurs as a result of a wide range of diseases or physical conditions or both, and may severely impair the quality of life. ...

. Myalgia

Myalgia or muscle pain is a painful sensation evolving from muscle tissue. It is a symptom of many diseases. The most common cause of acute myalgia is the overuse of a muscle or group of muscles; another likely cause is viral infection, espec ...

s may occur because of reduced carnitine

Carnitine is a quaternary ammonium compound involved in metabolism in most mammals, plants, and some bacteria. In support of energy metabolism, carnitine transports long-chain fatty acids from the cytosol into mitochondria to be oxidized for f ...

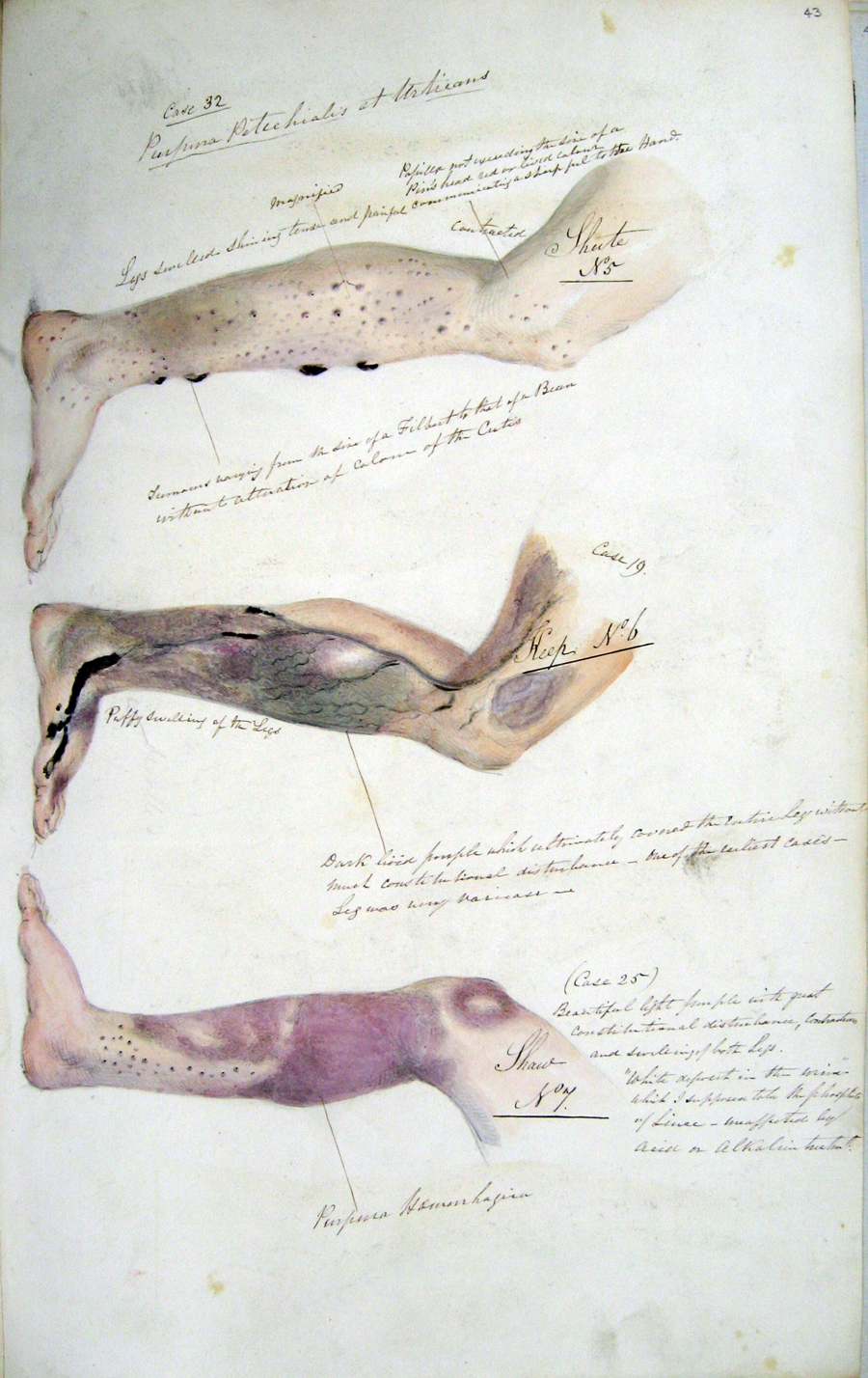

production. Other symptoms include skin changes with roughness, easy bruising, and petechia

A petechia (; : petechiae) is a small red or purple spot ( 1 cm in diameter) and purpura (3 to 10 mm in diameter). The term is typically used in the plural (petechiae), since a single petechia is seldom noticed or significant.

Causes Physical t ...

e, gum disease, loosening of teeth, poor wound healing, and emotional changes (which may appear before any physical changes). Dry mouth and dry eyes similar to Sjögren's syndrome may occur. In the late stages, jaundice

Jaundice, also known as icterus, is a yellowish or, less frequently, greenish pigmentation of the skin and sclera due to high bilirubin levels. Jaundice in adults is typically a sign indicating the presence of underlying diseases involving ...

, generalised edema

Edema (American English), also spelled oedema (British English), and also known as fluid retention, swelling, dropsy and hydropsy, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue (biology), tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. S ...

, oliguria

Oliguria or hypouresis is the low output of urine specifically more than 80 ml/day but less than 400ml/day. The decreased output of urine may be a sign of dehydration, kidney failure, hypovolemic shock, hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic Nonketotic Syndro ...

, neuropathy

Peripheral neuropathy, often shortened to neuropathy, refers to damage or disease affecting the nerves. Damage to nerves may impair sensation, movement, gland function, and/or organ function depending on which nerve fibers are affected. Neuropa ...

, fever, convulsions, and eventual death are frequently seen.

vitamin C

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits, berries and vegetables. It is also a generic prescription medication and in some countries is sold as a non-prescription di ...

deficiency

File:ASM-30-325-g001.jpg, A child with scurvy in flexion posture

File:ASM-30-325-g002.jpg, Photo of the chest cage with scorbutic rosaries

Cause

Scurvy, including subclinical scurvy, is caused by a deficiency of dietary vitamin C since humans are unable to synthesize vitamin C. Provided the diet contains sufficient vitamin C, the lack of working L-gulonolactone oxidase (GULO) enzyme has no significance. In modern Western societies, scurvy is rarely present in adults, although infants and elderly people are affected. Virtually all commercially available baby formulas contain added vitamin C, preventing infantile scurvy. Humanbreast milk

Breast milk (sometimes spelled as breastmilk) or mother's milk is milk produced by the mammary glands in the breasts of women. Breast milk is the primary source of nutrition for newborn infants, comprising fats, proteins, carbohydrates, and a var ...

contains sufficient vitamin C if the mother has an adequate intake. Commercial milk is pasteurized, a heating process that destroys the natural vitamin C content of the milk.

Scurvy is one of the accompanying diseases of malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients which adversely affects the body's tissues a ...

(other such micronutrient deficiencies are beriberi

Thiamine deficiency is a medical condition of low levels of thiamine (vitamin B1). A severe and chronic form is known as beriberi. The name beriberi was possibly borrowed in the 18th century from the Sinhalese phrase (bæri bæri, “I canno ...

and pellagra

Pellagra is a disease caused by a lack of the vitamin niacin (vitamin B3). Symptoms include inflamed skin, diarrhea, dementia, and sores in the mouth. Areas of the skin exposed to friction and radiation are typically affected first. Over tim ...

) and thus is still widespread in areas of the world dependent on external food aid. Although rare, there are also documented cases of scurvy due to poor dietary choices by people living in industrialized nations.

Pathogenesis

Vitamins are essential to the production and use of enzymes in ongoing processes throughout the human body.

Vitamins are essential to the production and use of enzymes in ongoing processes throughout the human body. Ascorbic acid

Ascorbic acid is an organic compound with formula , originally called hexuronic acid. It is a white solid, but impure samples can appear yellowish. It dissolves freely in water to give mildly acidic solutions. It is a mild reducing agent.

Asco ...

is needed for a variety of biosynthetic pathways, by accelerating hydroxylation

In chemistry, hydroxylation refers to the installation of a hydroxyl group () into an organic compound. Hydroxylations generate alcohols and phenols, which are very common functional groups. Hydroxylation confers some degree of water-solubility ...

and amidation

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent any group, typically organyl groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a p ...

reactions.

The early symptoms of malaise

In medicine, malaise is a feeling of general discomfort, uneasiness or lack of wellbeing and often the first sign of an infection or other disease. It is considered a vague termdescribing the state of simply not feeling well. The word has exist ...

and lethargy

Lethargy is a state of tiredness, sleepiness, weariness, fatigue, sluggishness, or lack of energy. It can be accompanied by depression, decreased motivation, or apathy. Lethargy can be a normal response to inadequate sleep, overexertion, overw ...

may be due to either impaired fatty acid metabolism

Fatty acid metabolism consists of various metabolic processes involving or closely related to fatty acids, a family of molecules classified within the lipid macronutrient category. These processes can mainly be divided into (1) catabolic processe ...

from a lack of carnitine and/or from a lack of catecholamines which are needed for the cAMP-dependent pathway

In the field of molecular biology, the cAMP-dependent pathway, also known as the adenylyl cyclase pathway, is a G protein-coupled receptor-triggered signaling cascade used in cell communication.

Discovery

cAMP was discovered by Earl Sutherla ...

in both glycogen metabolism and fatty acid metabolism. Impairment of either fatty acid metabolism or glycogen metabolism leads to decreased ATP (energy) production. ATP is needed for cellular functions, including muscle contraction

Muscle contraction is the activation of Tension (physics), tension-generating sites within muscle cells. In physiology, muscle contraction does not necessarily mean muscle shortening because muscle tension can be produced without changes in musc ...

. ''(For low ATP within the muscle cell, see also Purine nucleotide cycle

The Purine Nucleotide Cycle is a metabolic pathway in protein metabolism requiring the amino acids aspartate and glutamate. The cycle is used to regulate the levels of adenine nucleotides, in which ammonia and fumarate are generated. AMP conv ...

.)''

In the synthesis of collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

, ascorbic acid is required as a cofactor for prolyl hydroxylase

Procollagen-proline dioxygenase, commonly known as prolyl hydroxylase, is a member of the class of enzymes known as alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylases. These enzymes catalyze the incorporation of oxygen into organic substrates through a me ...

and lysyl hydroxylase. These two enzymes are responsible for the hydroxylation of the proline

Proline (symbol Pro or P) is an organic acid classed as a proteinogenic amino acid (used in the biosynthesis of proteins), although it does not contain the amino group but is rather a secondary amine. The secondary amine nitrogen is in the p ...

and lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. Lysine contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form when the lysine is dissolved in water at physiological pH), an α-carboxylic acid group ( ...

amino acids in collagen. Hydroxyproline

(2''S'',4''R'')-4-Hydroxyproline, or L-hydroxyproline ( C5 H9 O3 N), is an amino acid, abbreviated as Hyp or O, ''e.g.'', in Protein Data Bank.

Structure and discovery

In 1902, Hermann Emil Fischer isolated hydroxyproline from hydrolyzed gela ...

and hydroxylysine are important for stabilizing collagen by cross-linking the propeptides in collagen.

Collagen is a primary structural protein in the human body, necessary for healthy blood vessels, muscle, skin, bone, cartilage, and other connective tissues. Defective connective tissue leads to fragile capillaries, resulting in abnormal bleeding, bruising, and internal hemorrhaging. Collagen is an important part of bone, so bone formation is also affected. Teeth loosen, bones break more easily, and once-healed breaks may recur. Defective collagen fibrillogenesis impairs wound healing. Untreated scurvy is invariably fatal.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is typically based on physical signs,X-rays

An X-ray (also known in many languages as Röntgen radiation) is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength shorter than those of ultraviolet rays and longer than those of gamma rays. Roughly, X-rays have a wavelength ran ...

, and improvement after treatment.

Differential diagnosis

Various childhood-onset disorders can mimic the clinical and X-ray picture of scurvy such as: *Rickets

Rickets, scientific nomenclature: rachitis (from Greek , meaning 'in or of the spine'), is a condition that results in weak or soft bones in children and may have either dietary deficiency or genetic causes. Symptoms include bowed legs, stun ...

* Osteochondrodysplasias especially osteogenesis imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta (; OI), colloquially known as brittle bone disease, is a group of genetic disorders that all result in bones that bone fracture, break easily. The range of symptoms—on the skeleton as well as on the body's other Or ...

* Blount's disease

* Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis (OM) is the infectious inflammation of bone marrow. Symptoms may include pain in a specific bone with overlying redness, fever, and weakness. The feet, spine, and hips are the most commonly involved bones in adults.

The cause is ...

Prevention

Scurvy can be prevented by a diet that includes uncooked vitamin C-rich foods such as amla,bell pepper

The bell pepper (also known as sweet pepper, paprika, pepper, capsicum or, in some parts of the US midwest, mango) is the fruit of plants in the Grossum Group of the species ''Capsicum annuum''. Cultivars of the plant produce fruits in diff ...

s (sweet peppers), blackcurrant

The blackcurrant (''Ribes nigrum''), also known as black currant or cassis, is a deciduous shrub in the family Grossulariaceae grown for its edible berries. It is native to temperate parts of central and northern Europe and northern Asia, w ...

s, broccoli

Broccoli (''Brassica oleracea'' var. ''italica'') is an edible green plant in the Brassicaceae, cabbage family (family Brassicaceae, genus ''Brassica'') whose large Pseudanthium, flowering head, plant stem, stalk and small associated leafy gre ...

, chili peppers

Chili peppers, also spelled chile or chilli ( ), are varieties of berry-fruit plants from the genus ''Capsicum'', which are members of the nightshade family Solanaceae, cultivated for their pungency. They are used as a spice to add pungency ( ...

, guava

Guava ( ), also known as the 'guava-pear', is a common tropical fruit cultivated in many tropical and subtropical regions. The common guava '' Psidium guajava'' (lemon guava, apple guava) is a small tree in the myrtle family (Myrtaceae), nativ ...

, kiwifruit

Kiwifruit (often shortened to kiwi), or Chinese gooseberry, is the edible berry (botany), berry of several species of woody vines in the genus ''Actinidia''. The most common cultivar group of kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis var. deliciosa, ...

, and parsley

Parsley, or garden parsley (''Petroselinum crispum''), is a species of flowering plant in the family Apiaceae that is native to Greece, Morocco and the former Yugoslavia. It has been introduced and naturalisation (biology), naturalized in Eur ...

. Other sources rich in vitamin C are fruits such as lemon

The lemon (''Citrus'' × ''limon'') is a species of small evergreen tree in the ''Citrus'' genus of the flowering plant family Rutaceae. A true lemon is a hybrid of the citron and the bitter orange. Its origins are uncertain, but some ...

s, limes, oranges, papaya

The papaya (, ), papaw, () or pawpaw () is the plant species ''Carica papaya'', one of the 21 accepted species in the genus '' Carica'' of the family Caricaceae, and also the name of its fruit. It was first domesticated in Mesoamerica, within ...

, and strawberries

The garden strawberry (or simply strawberry; ''Fragaria × ananassa'') is a widely grown hybrid plant cultivated worldwide for its fruit. The genus ''Fragaria'', the strawberries, is in the rose family, Rosaceae. The fruit is appreciated f ...

. It is also found in vegetables, such as brussels sprouts, cabbage

Cabbage, comprising several cultivars of '' Brassica oleracea'', is a leafy green, red (purple), or white (pale green) biennial plant grown as an annual vegetable crop for its dense-leaved heads. It is descended from the wild cabbage ( ''B.& ...

, potato

The potato () is a starchy tuberous vegetable native to the Americas that is consumed as a staple food in many parts of the world. Potatoes are underground stem tubers of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'', a perennial in the nightshade famil ...

es, and spinach

Spinach (''Spinacia oleracea'') is a leafy green flowering plant native to Central Asia, Central and Western Asia. It is of the order Caryophyllales, family Amaranthaceae, subfamily Chenopodioideae. Its leaves are a common vegetable consumed eit ...

. Some fruits and vegetables not high in vitamin C may be pickled in lemon juice

The lemon (''Citrus'' × ''limon'') is a species of small evergreen tree in the ''Citrus'' genus of the flowering plant family Rutaceae. A true lemon is a hybrid of the citron and the bitter orange. Its origins are uncertain, but some ...

, which is high in vitamin C. Nutritional supplements that provide ascorbic acid well above what is required to prevent scurvy may cause adverse health effects.

Fresh meat from animals, notably internal organs, contains enough vitamin C to prevent scurvy, and even partly treat it.

Scott's 1902 Antarctic expedition used fresh seal meat and increased allowance of bottled fruits, whereby complete recovery from incipient scurvy was reported to have taken less than two weeks.

Treatment

Scurvy will improve with doses of vitamin C as low as 10 mg per day though doses of around 100 mg per day are typically recommended. Most people make a full recovery within 2 weeks.History

Symptoms of scurvy have been recorded inAncient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

as early as 1550 BC. It was first reported amongst soldiers and sailors having inadequate access to fruits and vegetables which resulted in vitamin C deficiency. In Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

, the physician Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; ; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician and philosopher of the Classical Greece, classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is traditionally referr ...

(460–370 BC) described symptoms of scurvy, specifically a "swelling and obstruction of the spleen

The spleen (, from Ancient Greek '' σπλήν'', splḗn) is an organ (biology), organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter.

The spleen plays important roles in reg ...

." In 406 CE, the Chinese monk Faxian

Faxian (337–), formerly romanization of Chinese, romanized as Fa-hien and Fa-hsien, was a Han Chinese, Chinese Chinese Buddhism, Buddhist bhikkhu, monk and translator who traveled on foot from Eastern Jin dynasty, Jin China to medieval India t ...

wrote that ginger

Ginger (''Zingiber officinale'') is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or ginger, is widely used as a spice and a folk medicine. It is an herbaceous perennial that grows annual pseudostems (false stems made of the rolled bases of l ...

was carried on Chinese ships to prevent scurvy.

The knowledge that consuming certain foods is a cure for scurvy has been repeatedly forgotten and rediscovered into the early 20th century.Maciej Cegłowski, 2010-03-06"Scott and Scurvy"

. Retrieved 2016-05-31. Scurvy occurred during the Great famine of Ireland in 1845 and also the American Civil War. In 2002, scurvy outbreaks were recorded in Afghanistan following the most intense phase of the war.

Early modern era

In the 13th centuryCrusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding ...

developed scurvy. In the 1497 expedition of Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama ( , ; – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and nobleman who was the Portuguese discovery of the sea route to India, first European to reach India by sea.

Da Gama's first voyage (1497–1499) was the first to link ...

, the curative effects of citrus fruit were already observed and were confirmed by Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral (; born Pedro Álvares de Gouveia; ) was a Portuguese nobleman, military commander, navigator and explorer regarded as the European discoverer of Brazil. He was the first human in history to ever be on four continents, ...

and his crew in 1507.

The Portuguese planted fruit trees and vegetables on Saint Helena

Saint Helena (, ) is one of the three constituent parts of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha, a remote British overseas territory.

Saint Helena is a volcanic and tropical island, located in the South Atlantic Ocean, some 1,874 km ...

, a stopping point for homebound voyages from Asia, and left their sick who had scurvy and other ailments to be taken home by the next ship if they recovered. In 1500, one of the pilots of Cabral's fleet bound for India noted that in Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban centr ...

, its king offered the expedition fresh supplies such as lamb, chicken, and duck, along with lemons and oranges, due to which "some of our ill were cured of scurvy".

These travel accounts did not prevent further maritime tragedies caused by scurvy, partly because of the lack of communication between travelers and those responsible for their health, and because fruits and vegetables could not be kept for long on ships.

In 1536, the French explorer Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier (; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French maritime explorer from Brittany. Jacques Cartier was the first Europeans, European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of the Saint Lawrence River, wh ...

, while exploring the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (, ) is a large international river in the middle latitudes of North America connecting the Great Lakes to the North Atlantic Ocean. Its waters flow in a northeasterly direction from Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawren ...

, used the local St. Lawrence Iroquoians' knowledge to save his men dying of scurvy. He boiled the needles of the aneda tree (generally believed to have been eastern white cedar) to make a tea that was later shown to contain 50 mg of vitamin C per 100 grams. Such treatments were not available aboard ship, where the disease was most common. Later, possibly inspired by this incident, several European countries experimented with preparations of various conifers, such as spruce beer, as cures for scurvy.

In 1579, the Spanish friar and physician Agustin Farfán published a book ''Tractado breve de anathomía y chirugía, y de algunas enfermedades que más comúnmente suelen haver en esta Nueva España'' in which he recommended oranges and lemons for scurvy, a remedy that was already known in the Spanish navy.

In February 1601, Captain James Lancaster

Sir James Lancaster (c. 1554 – 6 June 1618) was an English privateer and trader of the Elizabethan era.

Life and work

Lancaster came from Basingstoke in Hampshire.

Lancaster was brought up in Portugal as a merchant and soldier, but retu ...

, while commanding the first English East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

fleet ''en route'' to Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

, landed on the northern coast of Madagascar specifically to obtain lemons and oranges for his crew to stop scurvy. Captain Lancaster conducted an experiment using four ships under his command. One ship's crew received routine doses of lemon juice while the other three did not receive such treatment. As a result, members of the non-treated ships started to contract scurvy, with many dying as a result.

Researchers have estimated that during the Age of Exploration

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

(between 1500 and 1800), scurvy killed at least two million sailor

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship. While the term ''sailor'' ...

s. Jonathan Lamb wrote: "In 1499, Vasco da Gama lost 116 of his crew of 170; In 1520, Magellan lost 208 out of 230; ... all mainly to scurvy."

In 1593, Admiral Sir Richard Hawkins

Admiral Sir Richard Hawkins (or Hawkyns) (c. 1562 – 17 April 1622) was a 17th-century English seaman, explorer and privateer. He was the son of Admiral Sir John Hawkins.

Biography

He was from his earlier days familiar with ships and the ...

advocated drinking orange and lemon juice to prevent scurvy.

A 1609 book by Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola recorded several different remedies for scurvy known at this time in the Moluccas, including a kind of wine mixed with cloves and ginger, and "certain herbs". The Dutch sailors in the area were said to cure the same disease by drinking lime juice.

In 1614, John Woodall, Surgeon General of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

, published ''The Surgion's Mate'' as a handbook for apprentice surgeons aboard the company's ships. He repeated the experience of mariners that the cure for scurvy was fresh food or, if not available, oranges, lemons, limes, and tamarinds. He was, however, unable to explain the reason why, and his assertion had no impact on the prevailing opinion of the influential physicians of the age, that scurvy was a digestive complaint.

Besides afflicting ocean travelers, until the late Middle Ages scurvy was common in Europe in late winter, when few green vegetables, fruits, and root vegetables were available. This gradually improved with the introduction of potatoes from the Americas; by 1800, scurvy was virtually unheard of in Scotland, where it had previously been endemic.

18th century

In 2009, a handwritten household book authored by a Cornishwoman in 1707 was discovered in a house in Hasfield,

In 2009, a handwritten household book authored by a Cornishwoman in 1707 was discovered in a house in Hasfield, Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( , ; abbreviated Glos.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Herefordshire to the north-west, Worcestershire to the north, Warwickshire to the north-east, Oxfordshire ...

, containing a " for the Scurvy" amongst other largely medicinal and herbal recipes. The recipe consisted of extracts from various plants mixed with a plentiful supply of orange juice, white wine, or beer.

In 1734, Leiden

Leiden ( ; ; in English language, English and Archaism, archaic Dutch language, Dutch also Leyden) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Provinces of the Nethe ...

-based physician Johann Bachstrom

Jan Fryderyk or Johann Friedrich Bachstrom (24 December 1688, near Rawitsch, now Rawicz, Poland - June 1742, Nieswiez, now Nyasvizh, Belarus) was a writer, scientist and Lutheran theologian who spent the last decade of his life in Leiden. His surn ...

published a book on scurvy in which he stated, "scurvy is solely owing to a total abstinence from fresh vegetable food, and greens; which is alone the primary cause of the disease", and urged the use of fresh fruit and vegetables as a cure.

It was not until 1747 that James Lind

James Lind (4 October 1716 – 13 July 1794) was a Scottish physician. He was a pioneer of naval hygiene in the Royal Navy. By conducting one of the first ever clinical trials, he developed the theory that citrus fruits cured scurvy.

Lind ...

formally demonstrated that scurvy could be treated by supplementing the diet with citrus fruit, in one of the first controlled clinical experiments reported in the history of medicine. As a naval surgeon on HMS ''Salisbury'', Lind had compared several suggested scurvy cures: hard cider, vitriol

Vitriol is the general chemical name encompassing a class of chemical compounds comprising sulfates of certain metalsoriginally, iron or copper. Those mineral substances were distinguished by their color, such as green vitriol for hydrated iron(I ...

, vinegar

Vinegar () is an aqueous solution of diluted acetic acid and trace compounds that may include flavorings. Vinegar typically contains from 5% to 18% acetic acid by volume. Usually, the acetic acid is produced by a double fermentation, converting ...

, seawater

Seawater, or sea water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has approximat ...

, oranges, lemons, and a mixture of balsam of Peru

Balsam is the resinous exudate (or sap) which forms on certain kinds of trees and shrubs. Balsam (from Latin ''balsamum'' "gum of the balsam tree," ultimately from a Semitic source such as ) owes its name to the biblical Balm of Gilead.

Chem ...

, garlic

Garlic (''Allium sativum'') is a species of bulbous flowering plants in the genus '' Allium''. Its close relatives include the onion, shallot, leek, chives, Welsh onion, and Chinese onion. Garlic is native to central and south Asia, str ...

, myrrh

Myrrh (; from an unidentified ancient Semitic language, see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a few small, thorny tree species of the '' Commiphora'' genus, belonging to the Burseraceae family. Myrrh resin has been used ...

, mustard seed

Mustard seeds are the small round seeds of various mustard plants. The seeds are usually about in diameter and may be colored from yellowish white to black. They are an important spice in many regional foods and may come from one of three diff ...

and radish

The radish (''Raphanus sativus'') is a flowering plant in the mustard family, Brassicaceae. Its large taproot is commonly used as a root vegetable, although the entire plant is edible and its leaves are sometimes used as a leaf vegetable. Origina ...

root. In ''A Treatise on the Scurvy'' (1753) (Also archivesecond edition (1757)

Lind explained the details of his clinical trial and concluded "the results of all my experiments was, that oranges and lemons were the most effectual remedies for this distemper at sea." However, the experiment and its results occupied only a few paragraphs in a work that was long and complex and had little impact. Lind himself never actively promoted lemon juice as a single 'cure'. He shared medical opinion at the time that scurvy had multiple causes – notably hard work, bad water, and the consumption of salt meat in a damp atmosphere which inhibited healthful perspiration and normal excretion – and therefore required multiple solutions. Lind was also sidetracked by the possibilities of producing a concentrated 'rob' of lemon juice by boiling it. This process destroyed the vitamin C and was therefore unsuccessful. During the 18th century, scurvy killed more British sailors than wartime enemy action. It was mainly by scurvy that during George Anson's voyage around the world he lost nearly two-thirds of his crew (1,300 out of 2,000) within the first 10 months of the voyage. The Royal Navy enlisted 184,899 sailors during the

Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

; 133,708 of these were "missing" or died from disease, and scurvy was the leading cause.

Although sailors and naval surgeons were increasingly convinced that citrus fruits could cure scurvy throughout this period, the classically trained physicians who determined medical policy dismissed this evidence as merely anecdotal, as it did not conform to their theories of disease. Literature championing the cause of citrus juice had no practical impact. The medical theory was based on the assumption that scurvy was a disease of internal putrefaction

Putrefaction is the fifth stage of death, following pallor mortis, livor mortis, algor mortis, and rigor mortis. This process references the breaking down of a body of an animal Post-mortem interval, post-mortem. In broad terms, it can be view ...

brought on by faulty digestion caused by the hardships of life at sea and the naval diet. Although successive theorists gave this basic idea different emphases, the remedies they advocated (and which the navy accepted) amounted to little more than the consumption of 'fizzy drinks' to activate the digestive system, the most extreme of which was the regular consumption of 'elixir of vitriol' – sulphuric acid taken with spirits and barley water, and laced with spices.

In 1764, a new and similarly inaccurate theory on scurvy appeared. Advocated by Dr David MacBride and Sir John Pringle, Surgeon General of the Army and later President of the Royal Society, this idea was that scurvy was the result of a lack of 'fixed air' in the tissues which could be prevented by drinking infusions of malt and wort

Wort () is the liquid extracted from the mashing process during the brewing of beer or whisky. Wort contains the sugars, the most important being maltose and maltotriose, that will be Ethanol fermentation, fermented by the brewing yeast to prod ...

whose fermentation within the body would stimulate digestion and restore the missing gases. These ideas received wide and influential backing, when James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

set off to circumnavigate the world (1768–1771) in , malt and wort were top of the list of the remedies he was ordered to investigate. The others were beer, Sauerkraut

Sauerkraut (; , ) is finely cut raw cabbage that has been fermented by various lactic acid bacteria. It has a long shelf life and a distinctive sour flavor, both of which result from the lactic acid formed when the bacteria ferment the sugar ...

(a good source of vitamin C), and Lind's 'rob'. The list did not include lemons.

Cook did not lose a single man to scurvy, and his report came down in favor of malt and wort. The reason for the health of his crews on this and other voyages was Cook's regime of shipboard cleanliness, enforced by strict discipline, and frequent replenishment of fresh food and greenstuffs. Another beneficial rule implemented by Cook was his prohibition of the consumption of salt fat skimmed from the ship's copper boiling pans, then a common practice elsewhere in the Navy. In contact with air, the copper formed compounds that prevented the absorption of vitamins by the intestines.

The first major long-distance expedition that experienced virtually no scurvy was that of the Spanish naval officer Alessandro Malaspina, 1789–1794. Malaspina's medical officer, Pedro González, was convinced that fresh oranges and lemons were essential for preventing scurvy. Only one outbreak occurred, during a 56-day trip across the open sea. Five sailors came down with symptoms, one seriously. After three days at Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

, all five were healthy again. Spain's large empire and many ports of call made it easier to acquire fresh fruit.

Although towards the end of the century, MacBride's theories were being challenged, the medical authorities in Britain remained committed to the notion that scurvy was a disease of internal 'putrefaction' and the Sick and Hurt Board, run by administrators, felt obliged to follow its advice. Within the Royal Navy, however, opinion – strengthened by first-hand experience with lemon juice at the siege of Gibraltar and during Admiral Rodney's expedition to the Caribbean – had become increasingly convinced of its efficacy. This was reinforced by the writings of experts like Gilbert Blane and Thomas Trotter and by the reports of up-and-coming naval commanders.

With the coming of war in 1793, the need to eliminate scurvy became more urgent. The first initiative came not from the medical establishment but from the admirals. Ordered to lead an expedition against Mauritius, Rear Admiral Gardner was uninterested in the wort, malt, and elixir of vitriol that were still being issued to ships of the Royal Navy, and demanded that he be supplied with lemons, to counteract scurvy on the voyage. Members of the Sick and Hurt Board, recently augmented by two practical naval surgeons, supported the request, and the Admiralty ordered that it be done. There was, however, a last-minute change of plan, and the expedition against Mauritius was canceled. On 2 May 1794, only and two sloops under Commodore Peter Rainier sailed for the east with an outward bound convoy, but the warships were fully supplied with lemon juice and the sugar with which it had to be mixed.

In March 1795, it was reported that the ''Suffolk'' had arrived in India after a four-month voyage without a trace of scurvy and with a crew that was healthier than when it set out. The effect was immediate. Fleet commanders clamored also to be supplied with lemon juice, and by June the Admiralty acknowledged the groundswell of demand in the navy and agreed to a proposal from the Sick and Hurt Board that lemon juice and sugar should in future be issued as a daily ration to the crews of all warships.

It took a few years before the method of distribution to all ships in the fleet had been perfected and the supply of the huge quantities of lemon juice required to be secured, but by 1800, the system was in place and functioning. This led to a remarkable health improvement among the sailors and consequently played a critical role in gaining an advantage in naval battles against enemies who had yet to introduce the measures.

Scurvy was not only a disease of seafarers. The early colonists of Australia suffered greatly because of the lack of fresh fruit and vegetables in the winter. There the disease was called Spring fever or Spring disease and was described as an often fatal condition associated with skin lesions, bleeding gums, and lethargy. It was eventually identified as scurvy and the remedies already in use at sea were implemented.

19th century

The surgeon-in-chief of

The surgeon-in-chief of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's army at the Siege of Alexandria (1801), Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, wrote in his memoirs that the consumption of horse meat

Horse meat forms a significant part of the culinary traditions of many countries, particularly in Europe and Asia. The eight countries that consume the most horse meat consume about 4.3million horses a year. For the majority of humanity's early ...

helped the French to curb an epidemic of scurvy. The meat was cooked but was freshly obtained from young horses bought from Arabs, and was nevertheless effective. This helped to start the 19th-century tradition of horse meat consumption in France.

Lauchlin Rose patented a method used to preserve citrus juice without alcohol in 1867, creating a concentrated drink known as Rose's lime juice. The Merchant Shipping Act 1867

A merchant is a person who trades in goods produced by other people, especially one who trades with foreign countries. Merchants have been known for as long as humans have engaged in trade and commerce. Merchants and merchant networks operated i ...

required all ships of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

and Merchant Navy to provide a daily " lime or lemon juice" ration of one pound to sailors to prevent scurvy. The product became nearly ubiquitous, hence the term " limey", first for British sailors, then for English immigrants within the former British colonies (particularly America, New Zealand, and South Africa), and finally, in old American slang, all British people.

The plant '' Cochlearia officinalis'', also known as "common scurvygrass", acquired its common name from the observation that it cured scurvy, and it was taken on board ships in dried bundles or distilled extracts. Its bitter taste was usually disguised with herbs and spices; however, this did not prevent scurvygrass drinks and sandwiches from becoming a popular fad in the UK until the middle of the nineteenth century, when citrus fruits became more readily available.

West Indian limes began to take over from lemons, when Spain's alliance with France against Britain in the Napoleonic Wars made the supply of Mediterranean lemons problematic, and because they were more easily obtained from Britain's Caribbean colonies and were believed to be more effective because they were more acidic. It was the acid, not the (then-unknown) Vitamin C that was believed to cure scurvy. The West Indian limes were significantly lower in Vitamin C than the previous lemons and further were not served fresh but rather as lime juice, which had been exposed to light and air, and piped through copper tubing, all of which significantly reduced the Vitamin C. Indeed, a 1918 animal experiment using representative samples of the Navy and Merchant Marine's lime juice showed that it had virtually no antiscorbutic power at all.

The belief that scurvy was fundamentally a nutritional deficiency, best treated by consumption of fresh food, particularly fresh citrus or fresh meat, was not universal in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and thus sailors and explorers continued to have scurvy into the 20th century. For example, the Belgian Antarctic Expedition

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899 was the first expedition to winter in the Antarctic region. Led by Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery aboard the RV ''Belgica'', it was the first Belgian Antarctic expedition and is considered the fir ...

of 1897–1899 became seriously affected by scurvy when its leader, Adrien de Gerlache

Baron Adrien Victor Joseph de Gerlache de Gomery (; 2 August 1866 – 4 December 1934) was a Belgian officer in the Belgian Royal Navy who led the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–99.

Early years

Born in Hasselt in eastern Belgium as t ...

, initially discouraged his men from eating penguin and seal meat.

In the Royal Navy's Arctic

The Arctic (; . ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the North Pole, lying within the Arctic Circle. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway ( ...

expeditions in the mid-19th century, it was widely believed that scurvy was prevented by good hygiene on board ship, regular exercise, and maintaining crew morale, rather than by a diet of fresh food. Navy expeditions continued to be plagued by scurvy even while fresh (not jerked or tinned) meat was well known as a practical antiscorbutic among civilian whalers and explorers in the Arctic. In the latter half of the 19th century, there was greater recognition of the value of eating fresh meat as a means of avoiding or treating scurvy, but the lack of available game to hunt at high latitudes in winter meant it was not always a viable remedy. Criticism also focused on the fact that some of the men most affected by scurvy on Naval polar expeditions had been heavy drinkers, with suggestions that this predisposed them to the condition. Even cooking fresh meat did not destroy its antiscorbutic properties, especially as many cooking methods failed to bring all the meat to high temperature.

The confusion is attributed to several factors:

* while ''fresh'' citrus (particularly lemons) cured scurvy, lime ''juice'' that had been exposed to light, air, and copper tubing did not – thus undermining the theory that citrus cured scurvy;

* fresh meat (especially organ meat and raw meat, consumed in arctic exploration) also cured scurvy, undermining the theory that fresh vegetable matter was essential to preventing and curing scurvy;

* increased marine speed via steam shipping, improved nutrition on land, reduced the incidence of scurvy – and thus the ineffectiveness of copper-piped lime juice compared to fresh lemons was not immediately revealed.

In the resulting confusion, a new hypothesis was proposed, following the new germ theory of disease – that scurvy was caused by ptomaine, a waste product of bacteria, particularly in tainted tinned meat.

Infantile scurvy emerged in the late 19th century because children were fed pasteurized cow's milk, particularly in the urban upper class. While pasteurization killed bacteria, it also destroyed vitamin C. This was eventually resolved by supplementing with onion

An onion (''Allium cepa'' , from Latin ), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable that is the most widely cultivated species of the genus '' Allium''. The shallot is a botanical variety of the onion which was classifie ...

juice or cooked potatoes. Native Americans helped save some newcomers from scurvy by directing them to eat wild onions.

20th century

By the early 20th century, whenRobert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott (6 June 1868 – ) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the Discovery Expedition, ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–04 and the Terra Nova Expedition ...

made his first expedition to the Antarctic

The Antarctic (, ; commonly ) is the polar regions of Earth, polar region of Earth that surrounds the South Pole, lying within the Antarctic Circle. It is antipodes, diametrically opposite of the Arctic region around the North Pole.

The Antar ...

(1901–1904), the prevailing theory was that scurvy was caused by " ptomaine poisoning", particularly in tinned meat. However, Scott discovered that a diet of fresh meat from Antarctic seals cured scurvy before any fatalities occurred. But while he saw fresh meat as a cure for scurvy, he remained confused about its underlying causes.

In 1907, an animal model that would eventually help to isolate and identify the "antiscorbutic factor" was discovered. Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich, two Norwegian physicians studying shipboard beriberi

Thiamine deficiency is a medical condition of low levels of thiamine (vitamin B1). A severe and chronic form is known as beriberi. The name beriberi was possibly borrowed in the 18th century from the Sinhalese phrase (bæri bæri, “I canno ...

contracted by ship's crews in the Norwegian Fishing Fleet, wanted a small test mammal to substitute for the pigeon

Columbidae is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with small heads, relatively short necks and slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. ...

s then used in beriberi research. They fed guinea pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy ( ), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus ''Cavia'', family Caviidae. Animal fancy, Breeders tend to use the name "cavy" for the ani ...

s their test diet of grains and flour, which had earlier produced beriberi in their pigeons, and were surprised when classic scurvy resulted instead. This was a serendipitous choice of animal. Until that time, scurvy had not been observed in any organism apart from humans and had been considered an exclusively human disease. Certain birds, mammals, and fish are susceptible to scurvy, but pigeons are unaffected since they can synthesize ascorbic acid internally. Holst and Frølich found they could cure scurvy in guinea pigs with the addition of various fresh foods and extracts. This discovery of an animal experimental model for scurvy, which was made even before the essential idea of "vitamins" in foods had been put forward, has been called the single most important piece of vitamin C research.

In 1915, New Zealand troops in the Gallipoli Campaign had a lack of vitamin C in their diet which caused many of the soldiers to contract scurvy.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson (November 3, 1879 – August 26, 1962) was an Arctic explorer and ethnologist. He was born in Manitoba, Canada.

Early life and education

Stefansson, born William Stephenson, was born at Arnes, Manitoba, Canada, in 1879. ...

, an Arctic explorer who had lived among the Inuit

Inuit (singular: Inuk) are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and Subarctic regions of North America and Russia, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwe ...

, proved that the all-meat diet they consumed did not lead to vitamin deficiencies. He participated in a study in New York's Bellevue Hospital in February 1928, where he and a companion ate only meat for a year while under close medical observation, yet remained in good health.

In 1927, Hungarian biochemist

Biochemists are scientists who are trained in biochemistry. They study chemical processes and chemical transformations in living organisms. Biochemists study DNA, proteins and Cell (biology), cell parts. The word "biochemist" is a portmanteau of ...

Albert Szent-Györgyi

Albert Imre Szent-Györgyi de Rapoltu Mare, Nagyrápolt (; September 16, 1893 – October 22, 1986) was a Hungarian biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937. He is credited with first isolating vitamin C and disc ...

isolated a compound he called " hexuronic acid". Szent-Györgyi suspected hexuronic acid, which he had isolated from adrenal glands, to be the antiscorbutic agent, but he could not prove it without an animal-deficiency model. In 1932, the connection between hexuronic acid and scurvy was finally proven by American researcher Charles Glen King

Charles Glen King (October 22, 1896 – January 23, 1988) was an American biochemist who was a pioneer in the field of nutrition research and who isolated vitamin C at the same time as Albert Szent-Györgyi. A biography of King states that m ...

of the University of Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) is a Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. The university is composed of seventeen undergraduate and graduate schools and colle ...

. King's laboratory was given some hexuronic acid by Szent-Györgyi and soon established that it was the sought-after anti-scorbutic agent. Because of this, hexuronic acid was subsequently renamed ''ascorbic acid.''

21st century

Rates of scurvy in the developed world are low due to the greater access to vitamin C-rich foods. Those most commonly affected aremalnourished

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients which adversely affects the body's tissues a ...

people in the developing world

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreeme ...

and homeless

Homelessness, also known as houselessness or being unhoused or unsheltered, is the condition of lacking stable, safe, and functional housing. It includes living on the streets, moving between temporary accommodation with family or friends, liv ...

people. There have been outbreaks of the condition in refugee camps. Case reports in the developing world of those with poorly healing wounds have occurred.

In 2020, the overall incidence of scurvy in the US was about one in 4,000 people, up significantly from even a few years before. About two-thirds of all scurvy is found in autistic

Autism, also known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by differences or difficulties in social communication and interaction, a preference for predictability and routine, sensory processing di ...

people. Children and young people with autism are at risk of developing scurvy because some of them only eat a small number of foods (e.g., only rice and pasta). For some of them, the restricted diet takes the form of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID).

Human trials

Notable human dietary studies of experimentally induced scurvy were conducted onconscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

s during World War II in Britain and the United States on Iowa state prisoner volunteers in the late 1960s. These studies both found that all obvious symptoms of scurvy previously induced by an experimental scorbutic diet with extremely low vitamin C content could be completely reversed by additional vitamin C supplementation of only 10 mg per day. In these experiments, no clinical difference was noted between men given 70 mg vitamin C per day (which produced blood levels of vitamin C of about 0.55 mg/dl, about of tissue saturation levels), and those given 10 mg per day (which produced lower blood levels). Men in the prison study developed the first signs of scurvy about four weeks after starting the vitamin C-free diet, whereas in the British study, six to eight months were required, possibly because the subjects were pre-loaded with a 70 mg/day supplement for six weeks before the scorbutic diet was fed.

Men in both studies, on a diet devoid or nearly devoid of vitamin C, had blood levels of vitamin C too low to be accurately measured when they developed signs of scurvy, and in the Iowa study, at this time were estimated (by labeled vitamin C dilution) to have a body pool of less than 300 mg, with daily turnover of only 2.5 mg/day.

In other animals

Most animals and plants can synthesize vitamin C through a sequence ofenzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

-driven steps, which convert monosaccharides

Monosaccharides (from Greek ''monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

Chemically, monosaccharides are polyhydr ...

to vitamin C. However, some mammals have lost the ability to synthesize vitamin C, notably simian

The simians, anthropoids, or higher primates are an infraorder (Simiiformes ) of primates containing all animals traditionally called monkeys and apes. More precisely, they consist of the parvorders New World monkey, Platyrrhini (New World mon ...

s and tarsier

Tarsiers ( ) are haplorhine primates of the family Tarsiidae, which is the lone extant family within the infraorder Tarsiiformes. Although the group was prehistorically more globally widespread, all of the existing species are restricted to M ...

s. These make up one of two major primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

suborders, haplorrhini, and this group includes human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

s. The strepsirrhini

Strepsirrhini or Strepsirhini (; ) is a Order (biology), suborder of primates that includes the Lemuriformes, lemuriform primates, which consist of the lemurs of Fauna of Madagascar, Madagascar, galagos ("bushbabies") and pottos from Fauna of A ...

(non-tarsier prosimians) can make their vitamin C, and these include lemur

Lemurs ( ; from Latin ) are Strepsirrhini, wet-nosed primates of the Superfamily (biology), superfamily Lemuroidea ( ), divided into 8 Family (biology), families and consisting of 15 genera and around 100 existing species. They are Endemism, ...

s, loris

Loris is the common name for the strepsirrhine mammals of the subfamily Lorinae (sometimes spelled Lorisinae) in the family Lorisidae. ''Loris'' is one genus in this subfamily and includes the slender lorises, ''Nycticebus'' is the genus cont ...

es, potto

The pottos are three species of strepsirrhine primate in the genus ''Perodicticus'' of the family Lorisidae. In some English-speaking parts of Africa, they are called "softly-softlys".

Etymology

The common name "potto" may be from Wolof (a ...

s, and galago

Galagos , also known as bush babies or ''nagapies'' (meaning "night monkeys" in Afrikaans), are small nocturnal primates native to continental, sub-Sahara Africa, and make up the family Galagidae (also sometimes called Galagonidae). They are ...

s. Ascorbic acid is also not synthesized by at least two species of caviidae, the capybara

The capybara or greater capybara (''Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris'') is the largest living rodent, native to South America. It is a member of the genus '' Hydrochoerus''. The only other extant member is the lesser capybara (''Hydrochoerus isthmi ...

and the guinea pig

The guinea pig or domestic guinea pig (''Cavia porcellus''), also known as the cavy or domestic cavy ( ), is a species of rodent belonging to the genus ''Cavia'', family Caviidae. Animal fancy, Breeders tend to use the name "cavy" for the ani ...

. Certain birds and fish do not synthesize their vitamin C. All species that do not synthesize ascorbate require it in the diet. Deficiency causes scurvy in humans, and somewhat similar symptoms in other animals.

Animals that can contract scurvy all lack the L-gulonolactone oxidase (GULO) enzyme, which is required in the last step of vitamin C synthesis. The genomes of these species contain GULO as pseudogene

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of DNA that resemble functional genes. Pseudogenes can be formed from both protein-coding genes and non-coding genes. In the case of protein-coding genes, most pseudogenes arise as superfluous copies of fun ...

s, which serve as insight into the evolutionary past of the species.

Name

In babies, scurvy is sometimes referred to as ''Barlow's disease'', named after Thomas Barlow, a Britishphysician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

who described it in 1883. However, ''Barlow's disease'' may also refer to mitral valve prolapse

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a valvular heart disease characterized by the displacement of an abnormally thickened mitral valve leaflet into the atria of the heart, left atrium during Systole (medicine), systole. It is the primary form of myxom ...

(Barlow's syndrome), first described by John Brereton Barlow in 1966.

References

Further reading

* * * * *External links

{{Authority control Animal diseases Vitamin deficiencies Vitamin C Nutritional anemias Collagen disease Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate Wikipedia neurology articles ready to translate