Sulfa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

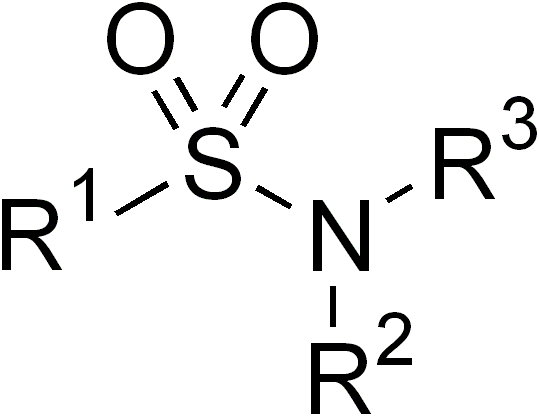

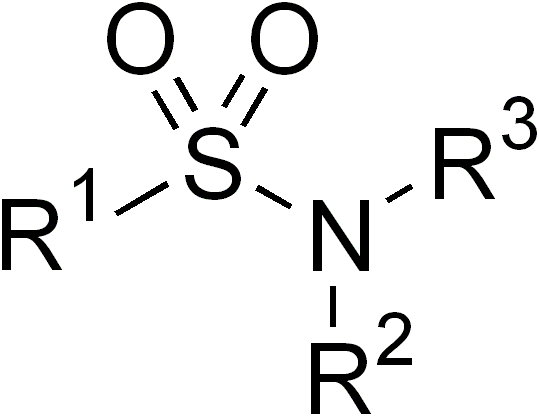

Sulfonamide is a

Sulfonamide is a

Sulfonamides are used to treat allergies and coughs, as well as having antifungal and antimalarial functions. The moiety is also present in other medications that are not antimicrobials, including

Sulfonamides are used to treat allergies and coughs, as well as having antifungal and antimalarial functions. The moiety is also present in other medications that are not antimicrobials, including

List of sulfonamides

Author

of ''

A History of the Fight Against Tuberculosis in Canada (Chemotherapy)

The History of WW II Medicine

"Five Medical Miracles of the Sulfa Drugs"

''Popular Science'', June 1942, pp. 73–78.

{{Diuretics Disulfiram-like drugs Hepatotoxins *

functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is a substituent or moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions regardless of the rest ...

(a part of a molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

) that is the basis of several groups of drugs

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via inhalat ...

, which are called sulphonamides, sulfa drugs or sulpha drugs. The original antibacterial sulfonamides are synthetic (nonantibiotic) antimicrobial

An antimicrobial is an agent that kills microorganisms or stops their growth. Antimicrobial medicines can be grouped according to the microorganisms they act primarily against. For example, antibiotics are used against bacteria, and antifungals ar ...

agents that contain the sulfonamide

In organic chemistry, the sulfonamide functional group (also spelled sulphonamide) is an organosulfur group with the structure . It consists of a sulfonyl group () connected to an amine group (). Relatively speaking this group is unreactive. ...

group. Some sulfonamides are also devoid of antibacterial activity, e.g., the anticonvulsant

Anticonvulsants (also known as antiepileptic drugs or recently as antiseizure drugs) are a diverse group of pharmacological agents used in the treatment of epileptic seizures. Anticonvulsants are also increasingly being used in the treatment of b ...

sultiame

Sultiame (or sulthiame) is a sulfonamide and inhibitor of the enzyme carbonic anhydrase. It is used as an anticonvulsant.

History

Sultiame was first synthesised in the laboratories of Bayer AG in the mid 1950s and eventually launched as Ospolot ...

. The sulfonylurea

Sulfonylureas (UK: sulphonylurea) are a class of organic compounds used in medicine and agriculture, for example as antidiabetic drugs widely used in the management of diabetes mellitus type 2. They act by increasing insulin release from the beta ...

s and thiazide diuretics

Thiazide () refers to both a class of sulfur-containing organic molecules and a class of diuretics based on the chemical structure of benzothiadiazine. The thiazide drug class was discovered and developed at Merck and Co. in the 1950s. The first ...

are newer drug groups based upon the antibacterial sulfonamides.

Allergies

Allergies, also known as allergic diseases, refer a number of conditions caused by the hypersensitivity of the immune system to typically harmless substances in the environment. These diseases include hay fever, food allergies, atopic derma ...

to sulfonamides are common. The overall incidence of adverse drug reactions

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is a harmful, unintended result caused by taking medication. ADRs may occur following a single dose or prolonged administration of a drug or result from the combination of two or more drugs. The meaning of this term ...

to sulfa antibiotics is approximately 3%, close to penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' moulds, principally '' P. chrysogenum'' and '' P. rubens''. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum using ...

; hence medications containing sulfonamides are prescribed carefully.

Sulfonamide drugs were the first broadly effective antibacterials to be used systemically, and paved the way for the antibiotic revolution in medicine.

Function

In bacteria, antibacterial sulfonamides act ascompetitive inhibitor

Competitive inhibition is interruption of a chemical pathway owing to one chemical substance inhibiting the effect of another by competing with it for binding or bonding. Any metabolic or chemical messenger system can potentially be affected b ...

s of the enzyme dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS), an enzyme involved in folate synthesis

Folate, also known as vitamin B9 and folacin, is one of the B vitamins. Manufactured folic acid, which is converted into folate by the body, is used as a dietary supplement and in food fortification as it is more stable during processing and ...

. Sulfonamides are therefore bacteriostatic and inhibit growth and multiplication of bacteria, but do not kill them. Humans, in contrast to bacteria, acquire folate

Folate, also known as vitamin B9 and folacin, is one of the B vitamins. Manufactured folic acid, which is converted into folate by the body, is used as a dietary supplement and in food fortification as it is more stable during processing and ...

(vitamin B9) through the diet.

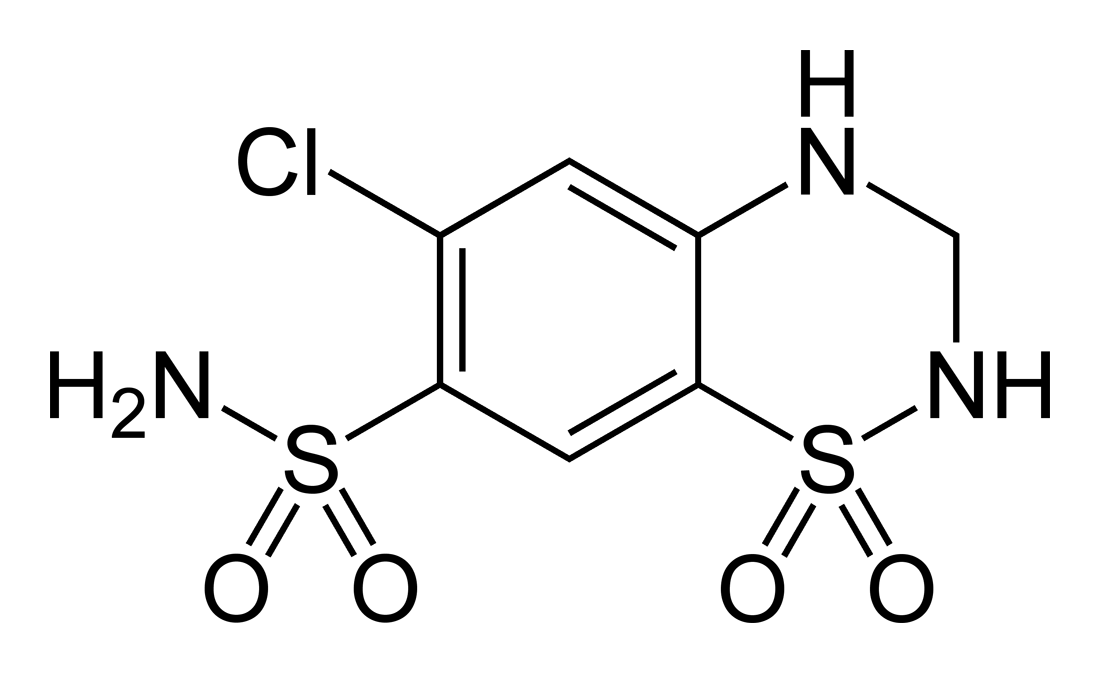

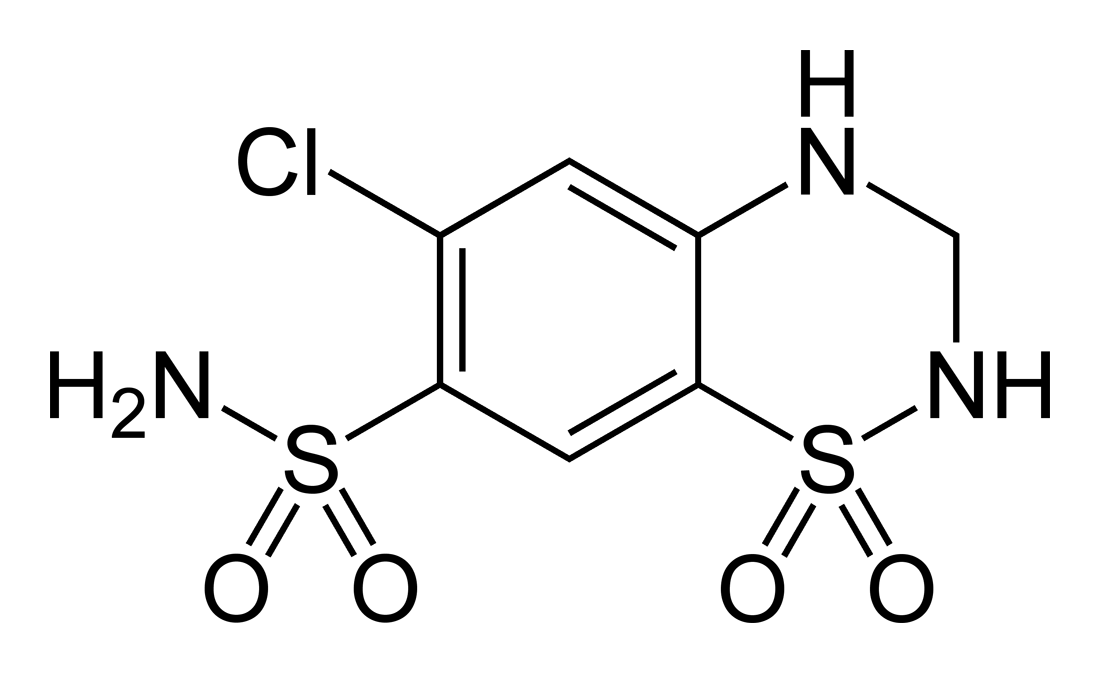

thiazide

Thiazide () refers to both a class of sulfur-containing organic molecules and a class of diuretics based on the chemical structure of benzothiadiazine. The thiazide drug class was discovered and developed at Merck and Co. in the 1950s. The first ...

diuretic

A diuretic () is any substance that promotes diuresis, the increased production of urine. This includes forced diuresis. A diuretic tablet is sometimes colloquially called a water tablet. There are several categories of diuretics. All diuretics in ...

s (including hydrochlorothiazide

Hydrochlorothiazide is a diuretic medication often used to treat high blood pressure and swelling due to fluid build-up. Other uses include treating diabetes insipidus and renal tubular acidosis and to decrease the risk of kidney stones in tho ...

, metolazone

Metolazone is a thiazide-like diuretic marketed under the brand names Zytanix, Metoz, Zaroxolyn, and Mykrox. It is primarily used to treat congestive heart failure and high blood pressure. Metolazone indirectly decreases the amount of water rea ...

, and indapamide

Indapamide is a thiazide-like diuretic drug used in the treatment of hypertension, as well as decompensated heart failure. Combination preparations with perindopril (an ACE inhibitor antihypertensive) are available. The thiazide-like diuretics ( ...

, among others), loop diuretics (including furosemide

Furosemide is a loop diuretic medication used to treat fluid build-up due to heart failure, liver scarring, or kidney disease. It may also be used for the treatment of high blood pressure. It can be taken by injection into a vein or by mouth ...

, bumetanide

Bumetanide, sold under the brand name Bumex among others, is a medication used to treat swelling and high blood pressure. This includes swelling as a result of heart failure, liver failure, or kidney problems. It may work for swelling when oth ...

, and torsemide

Torasemide, also known as torsemide, is a diuretic medication used to treat fluid overload due to heart failure, kidney disease, and liver disease and high blood pressure. It is a less preferred treatment for high blood pressure. It is taken by ...

), acetazolamide

Acetazolamide, sold under the trade name Diamox among others, is a medication used to treat glaucoma, epilepsy, altitude sickness, periodic paralysis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension (raised brain pressure of unclear cause), urine alkalin ...

, sulfonylureas (including glipizide

Glipizide, sold under the brand name Glucotrol among others, is an anti-diabetic medication of the sulfonylurea class used to treat type 2 diabetes. It is used together with a diabetic diet and exercise. It is not indicated for use by itself in ...

, glyburide

Glibenclamide, also known as glyburide, is an antidiabetic medication used to treat type 2 diabetes. It is recommended that it be taken together with diet and exercise. It may be used with other antidiabetic medication. It is not recommended f ...

, among others), and some COX-2 inhibitor

COX-2 inhibitors are a type of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that directly targets cyclooxygenase-2, COX-2, an enzyme responsible for inflammation and pain. Targeting selectivity for COX-2 reduces the risk of peptic ulceration and i ...

s (e.g., celecoxib

Celecoxib, sold under the brand name Celebrex among others, is a COX-2 inhibitor and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). It is used to treat the pain and inflammation in osteoarthritis, acute pain in adults, rheumatoid arthritis, ankyl ...

).

Sulfasalazine

Sulfasalazine, sold under the brand name Azulfidine among others, is a medication used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn's disease. It is considered by some to be a first-line treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. It is ...

, in addition to its use as an antibiotic, is also used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of inflammation, inflammatory conditions of the colon (anatomy), colon and small intestine, Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis being the principal types. Crohn's disease affects the small intestine a ...

.

History

Sulfonamide drugs were the first broadly effective antibacterials to be used systemically, and paved the way for the antibiotic revolution in medicine. The first sulfonamide, trade-namedProntosil

Prontosil is an antibacterial drug of the sulfonamide group. It has a relatively broad effect against gram-positive cocci but not against enterobacteria. One of the earliest antimicrobial drugs, it was widely used in the mid-20th century but is ...

, was a prodrug

A prodrug is a medication or compound that, after intake, is metabolized (i.e., converted within the body) into a pharmacologically active drug. Instead of administering a drug directly, a corresponding prodrug can be used to improve how the drug ...

. Experiments with Prontosil began in 1932 in the laboratories of Bayer

Bayer AG (, commonly pronounced ; ) is a German multinational corporation, multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company and one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world. Headquartered in Leverkusen, Bayer's areas of busi ...

AG, at that time a component of the huge German chemical trust IG Farben

Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG (), commonly known as IG Farben (German for 'IG Dyestuffs'), was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate (company), conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies—BASF, ...

. The Bayer team believed that coal-tar dyes which are able to bind preferentially to bacteria and parasites might be used to attack harmful organisms in the body. After years of fruitless trial-and-error work on hundreds of dyes, a team led by physician/researcher Gerhard Domagk

Gerhard Johannes Paul Domagk (; 30 October 1895 – 24 April 1964) was a German pathologist and bacteriologist. He is credited with the discovery of sulfonamidochrysoidine (KL730) as an antibiotic for which he received the 1939 Nobel Prize in Phy ...

(working under the general direction of IG Farben executive Heinrich Hörlein

Philipp Heinrich Hörlein (5 June 1882 – 23 May 1954), was a German entrepreneur, scientist, lecturer, and Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the f ...

) finally found one that worked: a red dye synthesized by Bayer chemist Josef Klarer that had remarkable effects on stopping some bacterial infections in mice. The first official communication about the breakthrough discovery was not published until 1935, more than two years after the drug was patented by Klarer and his research partner Fritz Mietzsch.

Prontosil

Prontosil is an antibacterial drug of the sulfonamide group. It has a relatively broad effect against gram-positive cocci but not against enterobacteria. One of the earliest antimicrobial drugs, it was widely used in the mid-20th century but is ...

, as Bayer named the new drug, was the first medicine ever discovered that could effectively treat a range of bacterial infections inside the body. It had a strong protective action against infections caused by streptococci, including blood infections, childbed fever, and erysipelas

Erysipelas () is a relatively common bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the skin ( upper dermis), extending to the superficial lymphatic vessels within the skin, characterized by a raised, well-defined, tender, bright red rash, t ...

, and a lesser effect on infections caused by other cocci. However, it had no effect at all in the test tube, exerting its antibacterial action only in live animals. Later, it was discovered by Daniel Bovet

Daniel Bovet (23 March 1907 – 8 April 1992) was a Swiss-born Italian pharmacologist who won the 1957 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of drugs that block the actions of specific neurotransmitters. He is best known for his ...

, Federico Nitti, and Jacques

Ancient and noble French family names, Jacques, Jacq, or James are believed to originate from the Middle Ages in the historic northwest Brittany region in France, and have since spread around the world over the centuries. To date, there are over ...

and Thérèse Tréfouël

Thérèse Tréfouël (née Boyer, 19 June 1892 — 9 November 1978) was a French chemist. Along with her husband, Jacques Tréfouël, she is best known for her research on sulfamides, a novel class of antibiotic drugs.

Education and personal l ...

, a French research team led by Ernest Fourneau

Ernest Fourneau (4 October 1872 – 5 August 1949) was a French pharmacist graduated in Pharmacy 1898 for the Paris university specialist in medicinal chemical and pharmacology who played a major role in the discovery of synthetic local anesthetic ...

at the Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (french: Institut Pasteur) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines f ...

, that the drug was metabolized into two parts inside the body, releasing from the inactive dye portion a smaller, colorless, active compound called sulfanilamide

Sulfanilamide (also spelled sulphanilamide) is a sulfonamide antibacterial drug. Chemically, it is an organic compound consisting of an aniline derivatized with a sulfonamide group. Powdered sulfanilamide was used by the Allies in World War II ...

. The discovery helped establish the concept of "bioactivation" and dashed the German corporation's dreams of enormous profit; the active molecule sulfanilamide (or sulfa) had first been synthesized in 1906 and was widely used in the dye-making industry; its patent had since expired and the drug was available to anyone.

The result was a sulfa craze. For several years in the late 1930s, hundreds of manufacturers produced myriad forms of sulfa. This and the lack of testing requirements led to the elixir sulfanilamide

Elixir sulfanilamide was an improperly prepared sulfonamide antibiotic that caused mass poisoning in the United States in 1937. It is believed to have killed more than 100 people. The public outcry caused by this incident and other similar disast ...

disaster in the fall of 1937, during which at least 100 people were poisoned with diethylene glycol

Diethylene glycol (DEG) is an organic compound with the formula (HOCH2CH2)2O. It is a colorless, practically odorless, and hygroscopic liquid with a sweetish taste. It is a four carbon dimer of ethylene glycol. It is miscible in water, alcohol, ...

. This led to the passage of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

The United States Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (abbreviated as FFDCA, FDCA, or FD&C) is a set of laws passed by the United States Congress in 1938 giving authority to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to oversee the safety of f ...

in 1938 in the United States. As the first and only effective broad-spectrum antibiotic available in the years before penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' moulds, principally '' P. chrysogenum'' and '' P. rubens''. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum using ...

, heavy use of sulfa drugs continued into the early years of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. They are credited with saving the lives of tens of thousands of patients, including Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr. (August 17, 1914 – August 17, 1988) was an American lawyer, politician, and businessman. He served as a United States congressman from New York from 1949 to 1955 and in 1963 was appointed United States Under Secre ...

(son of US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

) and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. Sulfa had a central role in preventing wound infections during the war. American soldiers were issued a first-aid kit

A first aid kit or medical kit is a collection of supplies and equipment used to give immediate medical treatment, primarily to treat injuries and other mild or moderate medical conditions. There is a wide variation in the contents of first aid ...

containing sulfa pills and powder and were told to sprinkle it on any open wound.

The sulfanilamide compound is more active in the protonated

In chemistry, protonation (or hydronation) is the adding of a proton (or hydron, or hydrogen cation), (H+) to an atom, molecule, or ion, forming a conjugate acid. (The complementary process, when a proton is removed from a Brønsted–Lowry acid, ...

form. The drug has very low solubility and sometimes can crystallize in the kidneys, due to its first pKa of around 10. This is a very painful experience, so patients are told to take the medication with copious amounts of water. Newer analogous compounds prevent this complication because they have a lower pKa, around 5–6, making them more likely to remain in a soluble form.

Many thousands of molecules containing the sulfanilamide structure have been created since its discovery (by one account, over 5,400 permutations by 1945), yielding improved formulations with greater effectiveness and less toxicity. Sulfa drugs are still widely used for conditions such as acne and urinary tract infections, and are receiving renewed interest for the treatment of infections caused by bacteria resistant to other antibiotics.

Preparation

Sulfonamides are prepared by the reaction of asulfonyl chloride

In inorganic chemistry, sulfonyl halide groups occur when a sulfonyl () functional group is singly bonded to a halogen atom. They have the general formula , where X is a halogen. The stability of sulfonyl halides decreases in the order fluorides ...

with ammonia or an amine. Certain sulfonamides (sulfadiazine or sulfamethoxazole) are sometimes mixed with the drug trimethoprim

Trimethoprim (TMP) is an antibiotic used mainly in the treatment of bladder infections. Other uses include for middle ear infections and travelers' diarrhea. With sulfamethoxazole or dapsone it may be used for ''Pneumocystis'' pneumonia in peop ...

, which acts against dihydrofolate reductase

Dihydrofolate reductase, or DHFR, is an enzyme that reduces dihydrofolic acid to tetrahydrofolic acid, using NADPH as an electron donor, which can be converted to the kinds of tetrahydrofolate cofactors used in 1-carbon transfer chemistry. In ...

. As of 2013, the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. A ...

is the largest exporter worldwide of sulfonamides, accounting for approximately 32% of total exports.

Varieties

Side effects

Sulfonamides have the potential to cause a variety ofadverse effect

An adverse effect is an undesired harmful effect resulting from a medication or other intervention, such as surgery. An adverse effect may be termed a "side effect", when judged to be secondary to a main or therapeutic effect. The term complica ...

s, including urinary tract disorders, haemopoietic disorders, porphyria

Porphyria is a group of liver disorders in which substances called porphyrins build up in the body, negatively affecting the skin or nervous system. The types that affect the nervous system are also known as acute porphyria, as symptoms are ra ...

and hypersensitivity reactions. When used in large doses, they may cause a strong allergic reaction. The most serious of these are classified as severe cutaneous adverse reactions

Severity or Severely may refer to:

* ''Severity'' (video game), a canceled video game

* "Severely" (song), by South Korean band F.T. Island

See also

*

*

{{disambig ...

(i.e. SCARs) and include the Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a type of severe skin reaction. Together with toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens–Johnson/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN), it forms a spectrum of disease, with SJS being less severe. Erythema ...

, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a type of severe skin reaction. Together with Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) it forms a spectrum of disease, with TEN being more severe. Early symptoms include fever and flu-like symptoms. A few days later th ...

(also known as Lyell syndrome), the DRESS syndrome

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also termed drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), is a rare reaction to certain medications. It involves primarily a widespread skin rash, fever, swollen lymph nodes, and c ...

, and a not quite as serious SCARs reaction, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) (also known as pustular drug eruption and toxic pustuloderma) is a rare skin reaction that in 90% of cases is related to medication administration.

AGEP is characterized by sudden skin eruptions th ...

. Any one of these SCARs may be triggered by certain sulfonamides.

Approximately 3% of the general population have adverse reactions when treated with sulfonamide antimicrobials. Of note is the observation that patients with HIV have a much higher prevalence, at about 60%.

Hypersensitivity reactions are less common in nonantibiotic sulfonamides, and, though controversial, the available evidence suggests those with hypersensitivity to sulfonamide antibiotics do not have an increased risk of hypersensitivity reaction to the nonantibiotic agents. A key component to the allergic response to sulfonamide antibiotics is the arylamine group at N4, found in sulfamethoxazole, sulfasalazine, sulfadiazine, and the anti-retrovirals amprenavir and fosamprenavir. Other sulfonamide drugs do not contain this arylamine group; available evidence suggests that patients who are allergic to arylamine sulfonamides do not cross-react to sulfonamides that lack the arylamine group, and may therefore safely take non-arylamine sulfonamides. It has therefore been argued that the terms "sulfonamide allergy" or "sulfa allergy" are misleading and should be replaced by a reference to a specific drug (e.g., "cotrimoxazole

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, sold under the brand name Bactrim among others, is a fixed-dose combination antibiotic medication used to treat a variety of bacterial infections. It consists of one part trimethoprim to five parts sulfamethoxaz ...

allergy").

Two regions of the sulfonamide antibiotic chemical structure are implicated in the hypersensitivity reactions associated with the class.

* The first is the N1 heterocyclic ring, which causes a type I hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity (also called hypersensitivity reaction or intolerance) refers to undesirable reactions produced by the normal immune system, including allergies and autoimmunity. They are usually referred to as an over-reaction of the immune s ...

reaction.

* The second is the N4 amino nitrogen that, in a stereospecific process, forms reactive metabolites that cause either direct cytotoxicity or immunologic response.

The nonantibiotic sulfonamides lack both of these structures.

The most common manifestations of a hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity (also called hypersensitivity reaction or intolerance) refers to undesirable reactions produced by the normal immune system, including allergies and autoimmunity. They are usually referred to as an over-reaction of the immune s ...

reaction to sulfa drugs are rash

A rash is a change of the human skin which affects its color, appearance, or texture.

A rash may be localized in one part of the body, or affect all the skin. Rashes may cause the skin to change color, itch, become warm, bumpy, chapped, dry, cr ...

and hives

Hives, also known as urticaria, is a kind of skin rash with red, raised, itchy bumps. Hives may burn or sting. The patches of rash may appear on different body parts, with variable duration from minutes to days, and does not leave any long-lasti ...

. However, there are several life-threatening manifestations of hypersensitivity to sulfa drugs, including Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a type of severe skin reaction. Together with toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens–Johnson/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN), it forms a spectrum of disease, with SJS being less severe. Erythema ...

, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a type of severe skin reaction. Together with Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) it forms a spectrum of disease, with TEN being more severe. Early symptoms include fever and flu-like symptoms. A few days later th ...

, agranulocytosis

Agranulocytosis, also known as agranulosis or granulopenia, is an acute condition involving a severe and dangerous lowered white blood cell count (leukopenia, most commonly of neutrophils) and thus causing a neutropenia in the circulating blood. ...

, hemolytic anemia

Hemolytic anemia or haemolytic anaemia is a form of anemia due to hemolysis, the abnormal breakdown of red blood cells (RBCs), either in the blood vessels (intravascular hemolysis) or elsewhere in the human body (extravascular). This most commonly ...

, thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia is a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of platelets, also known as thrombocytes, in the blood. It is the most common coagulation disorder among intensive care patients and is seen in a fifth of medical patients an ...

, fulminant hepatic necrosis, and acute pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a sudden inflammation of the pancreas. Causes in order of frequency include: 1) a gallstone impacted in the common bile duct beyond the point where the pancreatic duct joins it; 2) heavy alcohol use; 3) systemic disease; ...

, among others.

See also

*Dihydropteroate synthase

Dihydropteroate synthase is an enzyme classified under . It produces dihydropteroate in bacteria, but it is not expressed in most eukaryotes including humans. This makes it a useful target for sulfonamide antibiotics, which compete with the PAB ...

* Elixir sulfanilamide

Elixir sulfanilamide was an improperly prepared sulfonamide antibiotic that caused mass poisoning in the United States in 1937. It is believed to have killed more than 100 people. The public outcry caused by this incident and other similar disast ...

* Hellmuth Kleinsorge

Hellmuth Kleinsorge (* 12 April 1920 in Beuel; † 7 July 2001) was a German medical doctor.

Life

Hellmuth Kleinsorge studied medicine in Jena. In 1953, after his dissertation and habilitation, he became director of the "Medizinische Poliklinik ...

(1920-2001) German medical doctor

* PABA

* Timeline of antibiotics

This is the timeline of modern antimicrobial (anti-infective) therapy.

The years show when a given drug was released onto the pharmaceutical

market. This is not a timeline of the development of the antibiotics themselves.

* 1911 – Arsphenami ...

References

External links

List of sulfonamides

Author

of ''

The Demon Under the Microscope

''The Demon Under the Microscope: From Battlefield Hospitals to Nazi Labs, One Doctor's Heroic Search for the World's First Miracle Drug'' is a 2006 nonfiction book about the discovery of Prontosil, the first commercially available antibacterial an ...

'', a history of the discovery of the sulfa drugs

A History of the Fight Against Tuberculosis in Canada (Chemotherapy)

Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, according ...

, 1939

The History of WW II Medicine

"Five Medical Miracles of the Sulfa Drugs"

''Popular Science'', June 1942, pp. 73–78.

{{Diuretics Disulfiram-like drugs Hepatotoxins *