SS Metallurg Anosov on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The SS ''Metallurg Anosov'' (Russian: ''Металлург Аносов'') was a

/ref> At the time, only the commanding officer knew that the destination was

On 25 October, the Soviet government issued a statement of protest following the United States' blockade of Cuba as an illegal action under

On 25 October, the Soviet government issued a statement of protest following the United States' blockade of Cuba as an illegal action under

The first

The first

''Metallurg Anosov'' visited

''Metallurg Anosov'' visited

The stamp issued in 2013

/ref> This was the only Soviet ship mentioned in Cuban Missile Crisis and

merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are u ...

of Black Sea Shipping Company

Black Sea Shipping Company (russian: Черноморское морское пароходство, uk, Чорноморське морське пароплавство) is a Ukrainian shipping company based in Kyiv.

The company was established ...

(Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

). the ship was one of the project 567K ''Leninsky Komsomol class'', a multi-purpose tweendecker

Tweendeckers are general cargo ships with two or sometimes three decks. The upper deck is called the ''main deck'' or ''weather deck'', and the next lower deck is the ''tweendeck''. Cargo such as bales, bags, or drums can be stacked in the ''twe ...

freighter with steam turbine engines. The ship takes its name from scientist

A scientist is a person who conducts Scientific method, scientific research to advance knowledge in an Branches of science, area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, ...

and metallurgist

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

Pavel Anosov.

Specifications

Modifications

The SS ''Metallurg Anosov'' was one of the four ''Leninsky Komsomol''-class cargo ships specially equipped for troop and weapon transportation. The overall length of these transports was increased by , along with size increases to thecargo hold

120px, View of the hold of a container ship

A ship's hold or cargo hold is a space for carrying cargo in the ship's compartment.

Description

Cargo in holds may be either packaged in crates, bales, etc., or unpackaged (bulk cargo). Access to ho ...

widths, depths and bay doors. These modifications allowed the class to be used as a missile

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket i ...

carrier.

Engines

The main engines were made at theKirov Plant

The Kirov Plant, Kirov Factory or Leningrad Kirov Plant (LKZ) ( rus, Кировский завод, Kirovskiy zavod) is a major Russian mechanical engineering and agricultural machinery manufacturing plant in St. Petersburg, Russia. It was establ ...

(Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

), and were installed in the Kherson shipyard

The Kherson Shipyard ( uk, Херсонський суднобудівний завод (ХСЗ)) is a joint stock company located in Kherson, Ukraine at the mouth of the Dnieper River. The shipyard specializes in building merchant ships to include ...

. The engines produced 13000/14300 horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are the ...

at 1000 rpm, allowing the ship to achieve a ballasted speed of . The ship was equipped with a steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

turbo gear unit, the "TS-1" consisting of double-case turbine and gear fed by two fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bun ...

boilers, with a steam capacity of 25 tons per hour, at pressure of 42 atmospheres and temperature of 470 °C. The gearbox

Propulsion transmission is the mode of transmitting and controlling propulsion power of a machine. The term ''transmission'' properly refers to the whole drivetrain, including clutch, gearbox, prop shaft (for rear-wheel drive vehicles), differe ...

lowered the output rpm

Revolutions per minute (abbreviated rpm, RPM, rev/min, r/min, or with the notation min−1) is a unit of rotational speed or rotational frequency for rotating machines.

Standards

ISO 80000-3:2019 defines a unit of rotation as the dimensionl ...

to 100, and fed the power to the main propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

, a single four-bladed bronze propeller with a diameter of in an automated process.

Self-defence

In the event of mobilisation, the ship could mount severalanti-aircraft gun

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

s on the rotary turrets where the cargo cranes were mounted.

Record of service

After the completion of construction inKherson shipyard

The Kherson Shipyard ( uk, Херсонський суднобудівний завод (ХСЗ)) is a joint stock company located in Kherson, Ukraine at the mouth of the Dnieper River. The shipyard specializes in building merchant ships to include ...

, the ship passed sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s for three days in September 1962. The ship was commissioned by Black Sea Shipping Company

Black Sea Shipping Company (russian: Черноморское морское пароходство, uk, Чорноморське морське пароплавство) is a Ukrainian shipping company based in Kyiv.

The company was established ...

on 29 September 1962. At the time, the turbine-runner ''Metallurg Anosov'' was the fastest merchant vessel in the Soviet Union. The ship's dimensions: length overall 179 m, width – 22.6 m, moulded depth – 16 m, speed – .

After the signing of the act of acceptance, the ship was moved to Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

. Hold number 4 was converted for troop transportation by the dock workers, allowing for up to 1,600 soldiers to be bunked aboard. The vessel also took on fuel, food, fresh water, and other marine supplies before moving to Nikolayev for the loading of its main cargo, a set of missiles.

Maiden voyage

The maiden voyage of ''Metallurg Anosov'' occurred during theCuban blockade

The United States embargo against Cuba prevents American businesses, and businesses organized under U.S. law or majority-owned by American citizens, from conducting trade with Cuban interests. It is the most enduring trade embargo in modern hist ...

, the most stressful period of the Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

.

The ship was initially loaded in Nikolayev port with missiles of an unknown type and also a special containers for rocket fuel were latched onto the main deck

The main deck of a ship is the uppermost complete deck extending from bow to stern. A steel ship's hull may be considered a structural beam with the main deck forming the upper flange of a box girder and the keel forming the lower strength memb ...

.

A large number of troops from the 51st Missile Division, 664th Missile Regiment, including the regiment headquarters, combat support, and service subdivisions were housed in hold number 4 on 3 October 1962.СССР в строительстве ВМС Кубы. 8. Советские суда участвовавшие в переброске войск в ходе операции «Анадырь»./ref> At the time, only the commanding officer knew that the destination was

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

. Before deploying, General Degtyarev, who was in charge of the Defence Ministry at the time, held a briefing. The general then handed a secret package, marked "To be opened four days after the passage of the Strait of Gibraltar" to the master of the ship Babienko. Later that day, at 02:00 on the 4th of October 1962, the ship unmoored and began its maiden voyage to the Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar ( ar, مضيق جبل طارق, Maḍīq Jabal Ṭāriq; es, Estrecho de Gibraltar, Archaic: Pillars of Hercules), also known as the Straits of Gibraltar, is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Medi ...

.

Turkish warships met the ship close to the Bosphorus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

. After quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been ...

formalities, the warships accompanied the SS ''Metallurg Anosov'' through the Bosphorus, the Marmara Sea and Dardanelles to access the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

.

During transit through the Bosphorus, a barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels ...

without any illumination or signal lights appeared beside the ''Metallurg Anosov'' at night. The ship took evasive action, avoiding a collision with the barge by . Russian officials theorized that the Turks would have used a collision as pretext to storm the vessel, exposing the secret shipment.

A man aboard a similar ship taking the same route, the ''Divnogorsk,'' recounted the voyage:

Combined with the difficulties of transporting a large number of people on a vessel not designed for such, several difficulties were encountered with the ship's cargo. Primarily, the refueling tracks, tanks, and containers produced toxic fumes, and the containers themselves were volatile at high temperatures. The fuel could become toxic to people in the surrounding area, and there was a risk of explosion during the hot weather. Over these fuel tanks and containers, seawater was poured almost 24 hours per day to avoid an explosion from overheating. Living conditions of the people who accompanied the cargo were difficult. They breathed toxic substances, were irradiated, and accordingly became sick.

The rocket fuel "heptyl" was carried in special containers which were not present in the holds of the most common commercial vessels.

Four days after passing through the Gibraltar Strait the captain opened the secret package in the presence of the pompolit and the commander, Colonel Sergei Verenik. The package contained only a single line: "Turbine-runner 'Metallurg Anosov' has to sail to the Cuban port Cabañas." After it was read, the orders were burned.

Soldiers and officers came out at night only to breathe the ocean air, and to be away from the fumes below. Lessons on Cuban culture were taught during the voyage.

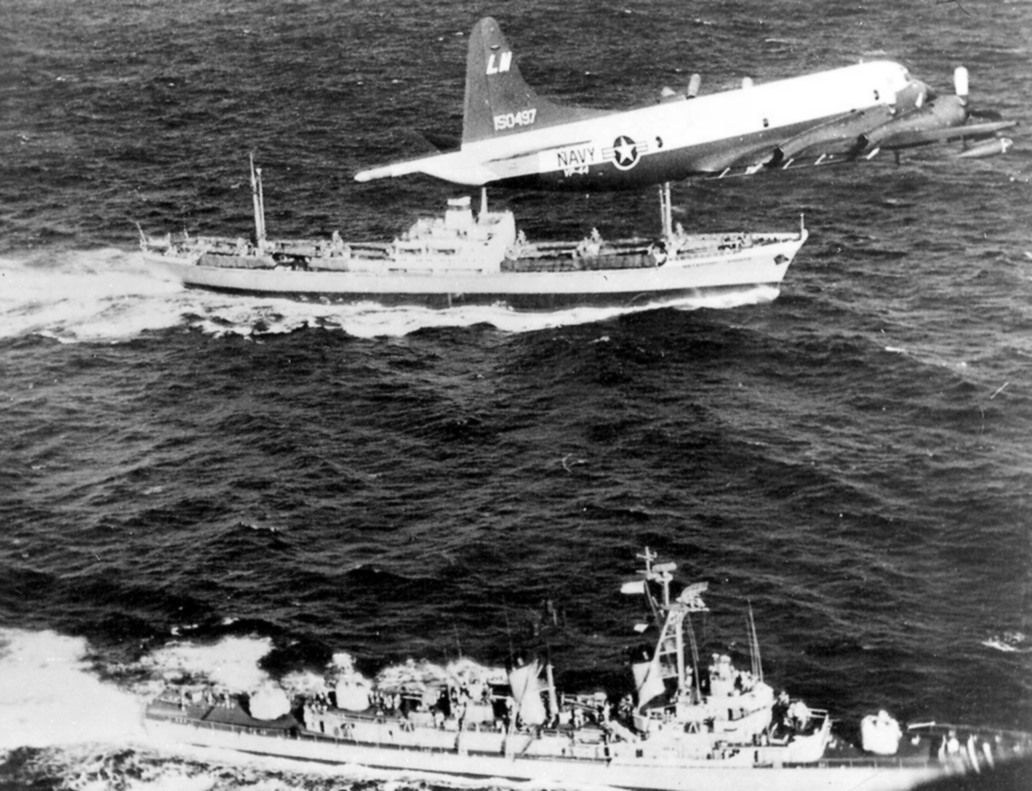

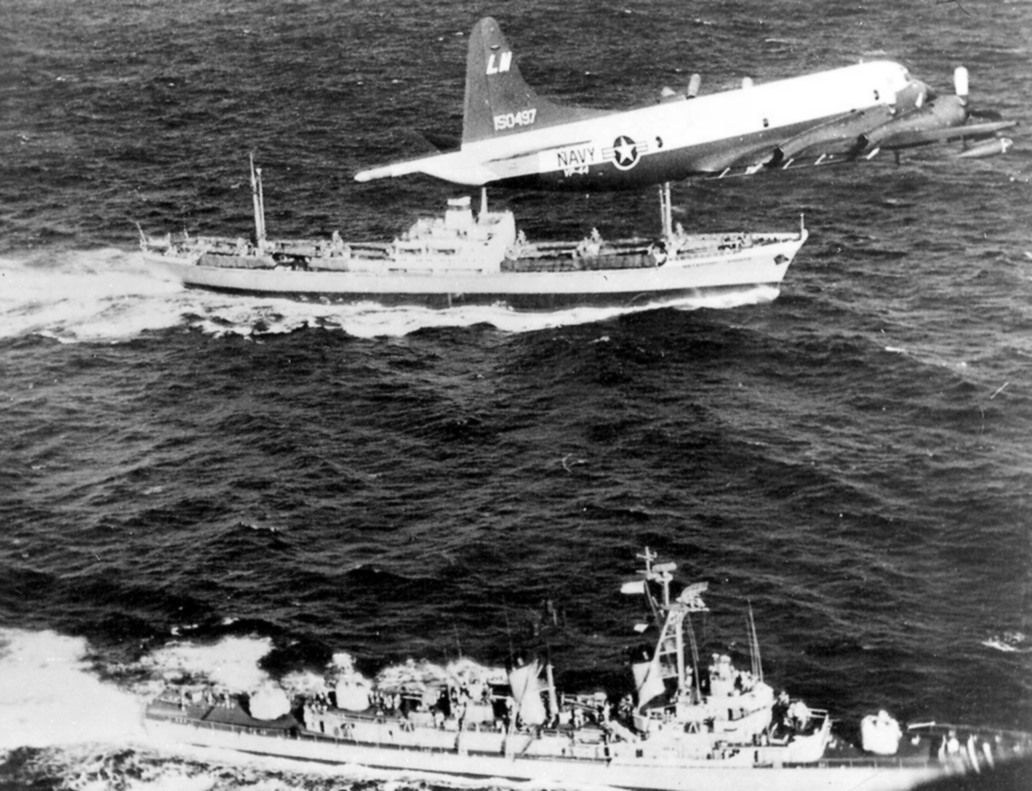

As the ship approached Cuba, it had several encounters with NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

forces. U.S. submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s were spotted floating in front of the ship, in an attempt to provoke a collision, or to send the ship off course. Additionally, several U.S. Navy airplanes repeatedly flew close over the ship, sometimes coming close to crashing into the ship's superstructure.

On 22 October, ''Metallurg Anosov'' arrived at the port of Cabañas. The first rank captain and two colonels met the ship at the pier. There the ship received a new order: to proceed to Mariel Bay Mariel may refer to:

* Mariel (given name)

* Mariel, Cuba, a municipality and city

* Mariel boatlift, a 1980 exodus of Cubans to the United States

* ''Mariel of Redwall'', a book in the Redwall series by Brian Jacques

* Mari-El, an autonomous repub ...

and receive a new order from the Soviet ambassador to Cuba, Alexander Alexeyev. One general and several colonels of General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, enlisted and civilian staff who serve the commander of a division or other large military un ...

met the ship at the specified bay.

On 25 October, the Soviet government issued a statement of protest following the United States' blockade of Cuba as an illegal action under

On 25 October, the Soviet government issued a statement of protest following the United States' blockade of Cuba as an illegal action under maritime law

Admiralty law or maritime law is a body of law that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. Admiralty law consists of both domestic law on maritime activities, and private international law governing the relationships between priva ...

. Captains of Soviet vessels received an order to not obey commands from US ships forbidding them from entering Cuban waters.

On 29 October 1962 the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

decided to take the missiles and other offensive weapons out of Cuba. Nine vessels, including the ''Metallurg Anosov'', were allocated to the task.

The ship was quickly unloaded, and as soon as the last cargo was ashore, the captain of the ship Babienko, received an order for the ship to return to Soviet Union. However, right before ship's departure a general came aboard for inspection. He immediately halted ship's departure. It would later be revealed that the First Vice Chairman of the Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or natio ...

of the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

Mikoyan

Russian Aircraft Corporation "MiG" (russian: Российская самолётостроительная корпорация „МиГ“, Rossiyskaya samolyotostroitel'naya korporatsiya "MiG"), commonly known as Mikoyan and MiG, was a Russi ...

had flown to Cuba on 2 November 1962, prompting the move.

Removing missiles from Cuba

The ''Metallurg Anosov'' was one of the nine Soviet freighters involved in returning Soviet missiles and their launchers to the USSR from Cuba. The loading of the missiles and their launchers was carried out in Mariel Bay, from 2 November through 7 November 1962. During the loading, NATO aircraft flew over the port and took photos. The ''Metallurg Anosov'' sailed from Mariel on 7 November 1962. USS ''Barry'' was ordered to investigate a Soviet merchant ship, and proceeded to her station on 9 November, sighting the merchant ship that evening. The ''Barry'' closed to within of the ''Metallurg Anosov''sstarboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

quarter, illuminated the ship's quarter and bow, and identified her. Trailing astern, the ''Barry'' followed the merchant ship, heading east away from the blockade zone, until morning. After dawn, the destroyer closed on the merchant, in order to "obtain photographs of deck cargo", until late morning when she changed course for the aircraft carrier USS ''Essex'' for refueling and to transfer the photographs.

USS ''Barry'' and a Patrol Squadron of VP-44

VP-44 was a Patrol Squadron of the U.S. Navy. It was established as VP-204 on 15 October 1942, redesignated as Patrol Bombing Squadron VPB-204 on 1 October 1944, redesignated as VP-204 on 15 May 1946, redesignated as VP-MS-4 on 15 November 1946, r ...

escorted this ship on the 10 of November, 1962. The VP-44

VP-44 was a Patrol Squadron of the U.S. Navy. It was established as VP-204 on 15 October 1942, redesignated as Patrol Bombing Squadron VPB-204 on 1 October 1944, redesignated as VP-204 on 15 May 1946, redesignated as VP-MS-4 on 15 November 1946, r ...

patrol squadron achieved international recognition of sorts when an aircraft photographed the deck while flying close surveillance over the ''Metallurg Anasov''. The ''Metallurg Anasov'' was the only Russian vessel refusing to uncover all of the missiles lashed to the deck. The squadron verified that eight large oblong objects, which appeared to be missiles, were located on its deck and the ship was allowed to proceed. The Utica '' Observer-Dispatch'' newspaper reported on 11 November 1962:

The ''Metallurg Anosov'' arrived at its destination port in the Black Sea after 20 November and was likely unloaded before 1 December 1962.

From December 1963 to August 1964

After December 1962, the ''Metallurg Anosov'' performed voyages to Cuba and Angola under the command of Captain Babienko.First circumnavigation

The first

The first circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first recorded circ ...

of the world for the ''Metallurg Anosov'' occurred from 4 August to 16 December 1963.

Ports of call, main straits and canals during the circumnavigation:

* Tuapse

Tuapse (russian: Туапсе́; ady, Тӏуапсэ ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town in Krasnodar Krai, Russia, situated on the northeast shore of the Black Sea, south of Gelendzhik and north of Sochi. Population:

Tuapse i ...

– sailed from port on 4 of August, 1963

* Bosphorus Strait

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern T ...

transit

* Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

transit

* Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

– bunkering

* Kokura, Japan

* Nagoya

is the largest city in the Chūbu region, the fourth-most populous city and third most populous urban area in Japan, with a population of 2.3million in 2020. Located on the Pacific coast in central Honshu, it is the capital and the most pop ...

, Japan

* Kobe

Kobe ( , ; officially , ) is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture Japan. With a population around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Tokyo and Yokohama. It is located in Kansai region, whic ...

, Japan

* Nakhodka

Nakhodka ( rus, Нахо́дка, p=nɐˈxotkə) is a port city in Primorsky Krai, Russia, located on the Trudny Peninsula jutting into the Nakhodka Bay of the Sea of Japan, about east of Vladivostok, the administrative center of the krai. Po ...

, USSR

* Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

transit

* Santiago de Cuba – discharge military cargo and likely loaded with sugar

* Montreal, Quebec, Canada – sugar discharge

* Baie-Comeau, Quebec, Canada – loading with grain

* Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

– bunkering

* Bosphorus Strait

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern T ...

transit

* Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

– arrived 16 of December, 1963Australian voyage

Ships of Black Sea Shipping Company rarely made call inAustralia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

n. This time the ''Metallurg Anosov'' made port in Australia, hence on this voyage the crew called it the "Australian voyage". The captain during this voyage was Nikolay Babienko.

The ''Metallurg Anosov'' sailed from the Black Sea through the Bosphorus, Dardanelles, Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

entered the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

and then to the final destination in the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

.

Call to Nakhodka

The ship arrived atNakhodka

Nakhodka ( rus, Нахо́дка, p=nɐˈxotkə) is a port city in Primorsky Krai, Russia, located on the Trudny Peninsula jutting into the Nakhodka Bay of the Sea of Japan, about east of Vladivostok, the administrative center of the krai. Po ...

port in Russia early in 1964 to take in bunker and supply. Call in Japan

In March 1964 the ship sailed from Japan, crossed theequator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

at longitude 154° 00' E on 14 March 1964, before proceeding to their destination port of Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, Australia.

Call in Sydney

The ''Metallurg Anosov'' proceeded to the berth for mooring inSydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

on 4 April 1964. The cargo for loading was grain. The ship briefly appears in 12th episode of NFSA "Life in Australia" series, "Life in Sydney".

Voyage from August 1964 to January 1965

The ship sailed from the Black Sea to Japan through theSuez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

in August 1964. From Japan, the ''Metallurg Anosov'' passed to Cuba through the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal ( es, Canal de Panamá, link=no) is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Pacific Ocean and divides North and South America. The canal cuts across the Isthmus of Panama and is a conduit ...

. From Cuba, the ship went back to Japan through the Panama Camal to unload a cargo of sugar in Japan. Then the vessel ran to Singapore to load rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds. Thailand, Malaysia, and ...

. After Singapore, the ship returned to the Black Sea and discharged cargo in Illichivsk

Chornomorsk ( uk, Чорномо́рськ, ), formerly Illichivsk (, Romanization of Ukrainian, translit. ''Illichivs'k''), is a city in Odesa Raion, Odesa Oblast (Oblast, province) of south-western Ukraine, dependent on the Port of Chornomorsk ...

port in January 1965.

Service from 1965 to 1967

For its next voyages, of ''Metallurg Anosov'' went between the Black Sea and Cuba. The ship also visitedAlexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

and Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

between 1965 and 1967.

During its voyages to Algeria, the ship carried military cargo.

Around Africa from 1967 to 1969

During theSix-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

in June 1967 Israel occupied the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is a l ...

, and as such the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

was closed for shipping between 1967 and 1975.

Therefore, the ''Metallurg Anosov'' was forced to go around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

from 1967 to 1975, visiting South African ports for bunkering for voyages from the Black Sea to Asian ports in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. During its trip, the ship crossed the equator at longitude 009° 30' W on 24 of July 1967 and the crew received Equator Line Crossing Certificates.

Circumnavigation including equatorial crossing (1969-1970)

According to another certificate of equatorial crossing, the ''Metallurg Anosov'' again circumnavigated the globe when she sailed from Odessa to Cuba. After leaving port in Cuba in late 1969 or early January 1970, the ship passed through the Panama Canal and steamed to Japan. The equator was crossed in theAtlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

in March 1970. The ship then passed around Africa and received bunker and other ship's supply in a South African __NOTOC__

South African may relate to:

* The nation of South Africa

* South African Airways

* South African English

* South African people

* Languages of South Africa

* Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the Afric ...

port.

Around Africa from 1971–1975

The ship was in a Black Sea Soviet port in February 1971, for a change of crew. The ''Metallurg Anosov'' skirted the epicenter of acyclone

In meteorology, a cyclone () is a large air mass that rotates around a strong center of low atmospheric pressure, counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from above (opposite to an anti ...

with a strength of 8 points on the Beaufort scale

The Beaufort scale is an empirical measure that relates wind speed to observed conditions at sea or on land. Its full name is the Beaufort wind force scale.

History

The scale was devised in 1805 by the Irish hydrographer Francis Beaufort ...

, when she came back from Cuba in 1971.

The ship visited Qatar once, sometime between 15 April 1971 and February 1973.

The ship visited Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

in the second part of January 1973.

The ship was in Cuba at the end of March and in May 1973. After Cuba the ship was loaded in the United States and proceeded to Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

for discharge. After Beirut the ship went back to the USSR.

During the next voyage from the USSR, the ship arrived at Cuba in the second part of September, and sailed from Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

on 7 October 1973 to Canada. During voyage, ship was repeatedly buzzed by American planes. The ship was loaded with grain in Canada, before sailing to Odessa in the second part of November 1973, and finally on to Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk ( rus, Новоросси́йск, p=nəvərɐˈsʲijsk; ady, ЦIэмэз, translit=Chəməz, p=t͡sʼɜmɜz) is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is one of the largest ports on the Black Sea. It is one of the few cities hono ...

port.

The ship was docked in Cuba at the end of March and in April 1975.

The ship docked in Haiphong port, Vietnam, in the second half of June, and in the first half of August 1975.

In October 1975 the ship visited Japan.

From 1976 to 1986

''Metallurg Anosov'' visited

''Metallurg Anosov'' visited Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

once, in 1976. The ship brought in military cargo to Luanda

Luanda () is the capital and largest city in Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major industrial, cultural and urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atlantic coast, Luanda is Angola's administrative centre, its chief seaport ...

.

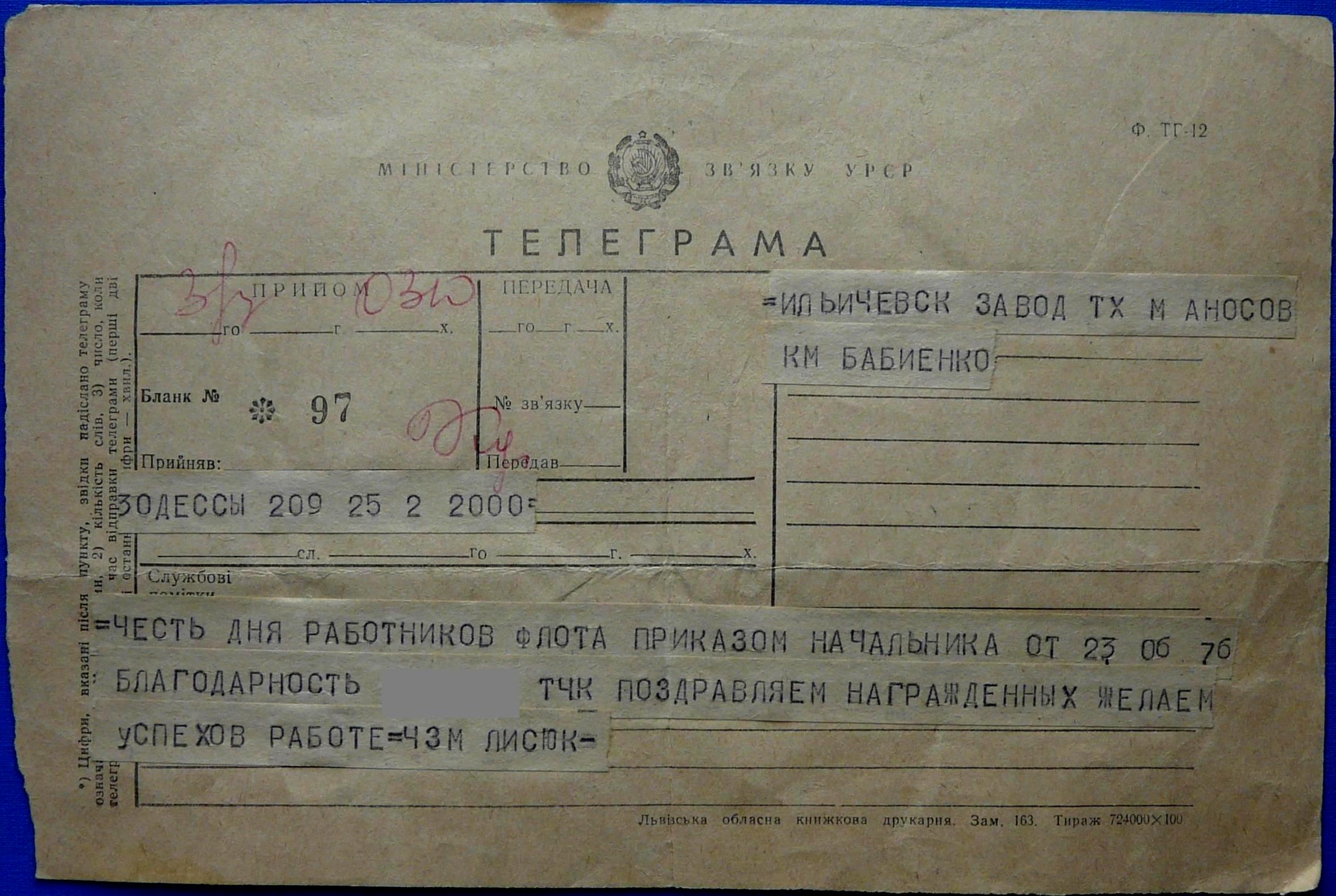

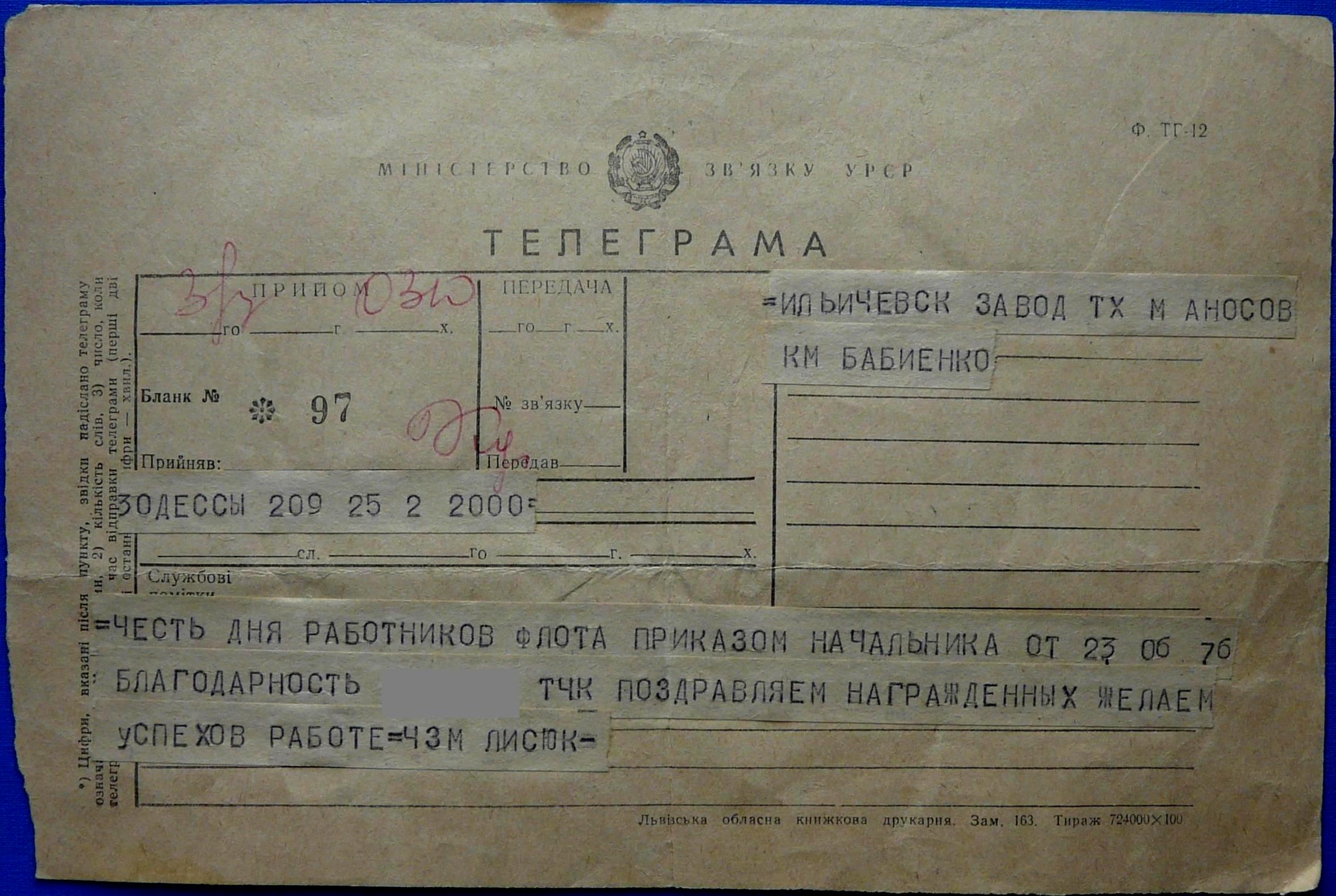

The ship was under repair in Ilyichevsk Shipyard in the summer of 1976.

''Metallurg Anosov'' arrived in Odessa from Rijeka

Rijeka ( , , ; also known as Fiume hu, Fiume, it, Fiume ; local Chakavian: ''Reka''; german: Sankt Veit am Flaum; sl, Reka) is the principal seaport and the third-largest city in Croatia (after Zagreb and Split). It is located in Primor ...

on 19 of February, 1977.

The ship was on Cuba in the first part of May 1979, again to deliver missiles and other military cargo.

Final journey and scrapping

''Metallurg Anosov'' was sold for scrap on 21 March 1986 and renamed ''Anosov''. The ship's home port and flag were changed to George Town, Cayman Islands. The ship arrived in China in May 1986. ''Anosov'' proceeded to Qinhuangdao and scrapped on 22 May 1986.Stamps

The ''SS Metallurg Anosov'' was featured on apostage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the fa ...

issued in 2008, and another issued in 2013./ref> This was the only Soviet ship mentioned in Cuban Missile Crisis and

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

stamps, as it was involved in both the Cuban Missile Crisis and other Cold War operations.

See also

*Operation Anadyr

Operation Anadyr (russian: Анадырь) was the code name used by the Soviet Union for its Cold War secret operation in 1962 of deploying ballistic missiles, medium-range bombers, and a division of mechanized infantry to Cuba to create an ar ...

* Cuban blockade

The United States embargo against Cuba prevents American businesses, and businesses organized under U.S. law or majority-owned by American citizens, from conducting trade with Cuban interests. It is the most enduring trade embargo in modern hist ...

* Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

* Leninsky Komsomol class cargo ships

The ''Leninsky Komsomol class'' (also transliterated as ''Leninskiy Komsomol'' or ''Leninskij Komsomol'' (Russian: ''Ленинский Комсомол класс'') was a class of 25 ocean-going dry cargo ships; tweendeckers with turbine main e ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Metallurg Anosov 1962 ships Cuba–Soviet Union relations Cuban Missile Crisis Leninsky Komsomol-class cargo ships Soviet Union–United States relations Ships built at Kherson Shipyard Ships built in the Soviet Union