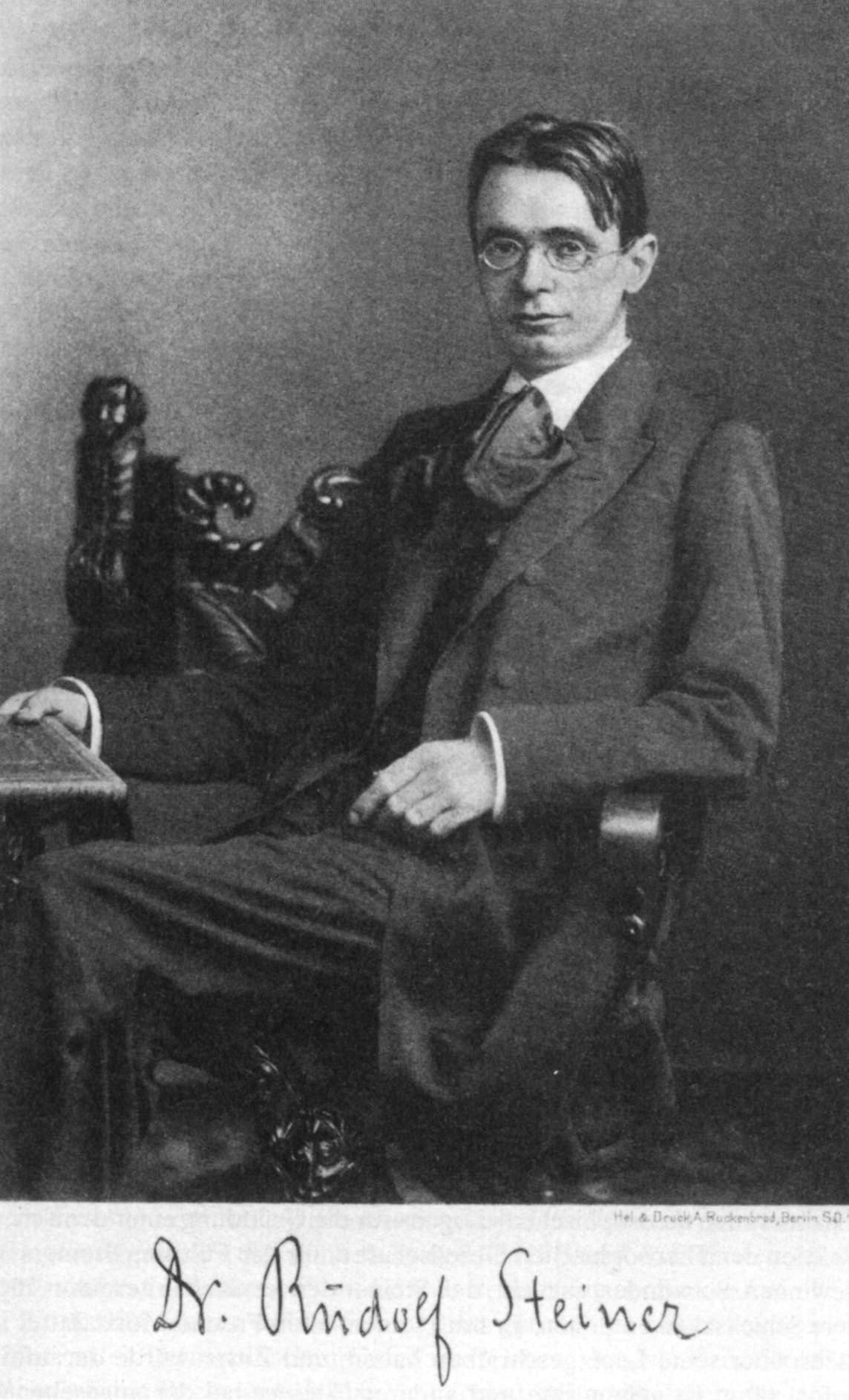

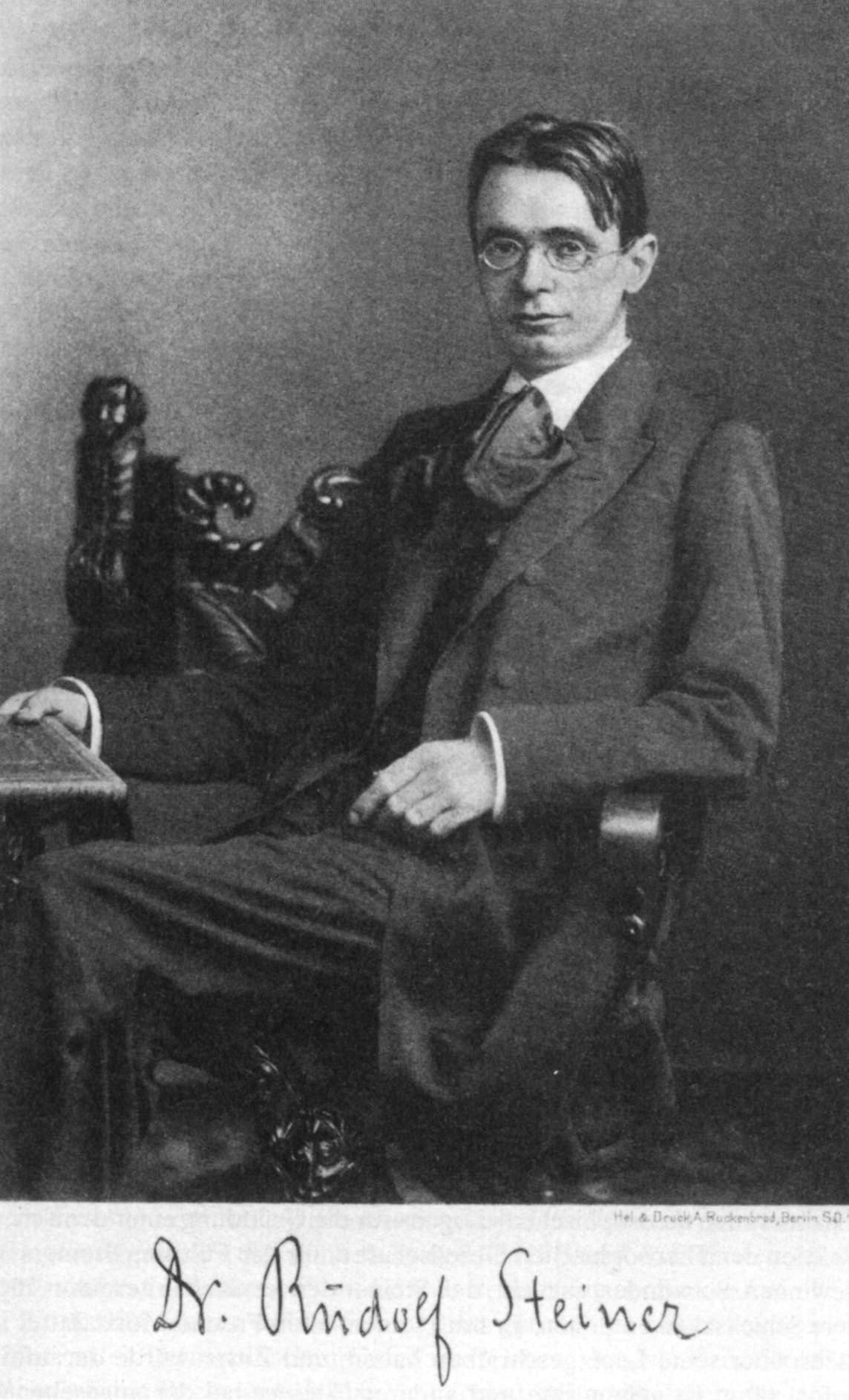

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (27 or 25 February 1861

– 30 March 1925) was an

Austrian occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism ...

ist,

social reformer

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary m ...

,

architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

,

esotericist, and claimed

clairvoyant.

Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century as a

literary critic and published works including ''

The Philosophy of Freedom''. At the beginning of the twentieth century he founded an esoteric spiritual movement,

anthroposophy, with roots in

German idealist philosophy and

theosophy. Many of his ideas are pseudoscientific. He was also prone to

pseudohistory.

In the first, more philosophically oriented phase of this movement, Steiner attempted to find a synthesis between

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

and

spirituality. His philosophical work of these years, which he termed "

spiritual science", sought to apply what he saw as the clarity of thinking characteristic of Western philosophy to spiritual questions,

[ differentiating this approach from what he considered to be vaguer approaches to mysticism. In a second phase, beginning around 1907, he began working collaboratively in a variety of artistic media, including drama, dance and architecture, culminating in the building of the Goetheanum, a cultural centre to house all the arts. In the third phase of his work, beginning after ]World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Steiner worked on various ostensibly applied projects, including Waldorf education

Waldorf education, also known as Steiner education, is based on the educational philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy. Its educational style is holistic, intended to develop pupils' intellectual, artistic, and practical ...

,anthroposophical medicine

Anthroposophy is a Spiritualism, spiritualist movement founded in the early 20th century by the Western esotericism, esotericist Rudolf Steiner that postulates the existence of an objective, intellectually comprehensible spirituality, spiritual w ...

.[Christoph Lindenberg, ''Rudolf Steiner'', Rowohlt 1992, , pp. 123–6]

Steiner advocated a form of ethical individualism, to which he later brought a more explicitly spiritual approach. He based his epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

on Johann Wolfgang Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as treatis ...

's world view, in which "thinking…is no more and no less an organ of perception than the eye or ear. Just as the eye perceives colours and the ear sounds, so thinking perceives ideas." A consistent thread that runs through his work is the goal of demonstrating that there are no limits to human knowledge.

Biography

Childhood and education

Steiner's father, Johann(es) Steiner (1829–1910), left a position as a gamekeeper in the service of Count Hoyos in Geras, northeast

Steiner's father, Johann(es) Steiner (1829–1910), left a position as a gamekeeper in the service of Count Hoyos in Geras, northeast Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt ...

to marry one of the Hoyos family's housemaids, Franziska Blie (1834 Horn – 1918, Horn), a marriage for which the Count had refused his permission. Johann became a telegraph operator on the Southern Austrian Railway, and at the time of Rudolf's birth was stationed in Murakirály ( Kraljevec) in the Muraköz region of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephe ...

, Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

(present-day Donji Kraljevec in the Međimurje region of northernmost Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

). In the first two years of Rudolf's life, the family moved twice, first to Mödling, near Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, and then, through the promotion of his father to stationmaster, to Pottschach, located in the foothills of the eastern Austrian Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, ...

in Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt ...

.Wiener Neustadt

Wiener Neustadt (; ; Central Bavarian: ''Weana Neistod'') is a city located south of Vienna, in the state of Lower Austria, in northeast Austria. It is a self-governed city and the seat of the district administration of Wiener Neustadt-Land D ...

.[Rudolf Steine]

Autobiography: Chapters in the Course of My Life: 1861–1907

Lantern Books, 2006

In 1879, the family moved to Inzersdorf to enable Steiner to attend the Vienna Institute of Technology, where he enrolled in courses in mathematics,

In 1879, the family moved to Inzersdorf to enable Steiner to attend the Vienna Institute of Technology, where he enrolled in courses in mathematics, physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

, chemistry, botany

Botany, also called plant science (or plant sciences), plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "bot ...

, zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

, and mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

and audited courses in literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to inclu ...

and philosophy, on an academic scholarship from 1879 to 1883, where he completed his studies and the requirements of the Ghega scholarship satisfactorily.[ suggested Steiner's name to Joseph Kürschner, chief editor of a new edition of Goethe's works, who asked Steiner to become the edition's natural science editor, a truly astonishing opportunity for a young student without any form of academic credentials or previous publications.][Steiner, ''Correspondence and Documents 1901–1925'', 1988, p. 9. ]

Early spiritual experiences

When he was nine years old, Steiner believed that he saw the spirit of an aunt who had died in a far-off town, asking him to help her at a time when neither he nor his family knew of the woman's death. Steiner later related that as a child, he felt "that one must carry the knowledge of the spiritual world within oneself after the fashion of geometry ...

When he was nine years old, Steiner believed that he saw the spirit of an aunt who had died in a far-off town, asking him to help her at a time when neither he nor his family knew of the woman's death. Steiner later related that as a child, he felt "that one must carry the knowledge of the spiritual world within oneself after the fashion of geometry ... or here

Or or OR may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* "O.R.", a 1974 episode of M*A*S*H

* Or (My Treasure), a 2004 movie from Israel (''Or'' means "light" in Hebrew)

Music

* ''Or'' (album), a 2002 album by Golden Boy with Mis ...

one is permitted to know something which the mind alone, through its own power, experiences. In this feeling I found the justification for the spiritual world that I experienced ... I confirmed for myself by means of geometry the feeling that I must speak of a world 'which is not seen'."[

Steiner believed that at the age of 15 he had gained a complete understanding of the concept of time, which he considered to be the precondition of spiritual ]clairvoyance

Clairvoyance (; ) is the magical ability to gain information about an object, person, location, or physical event through extrasensory perception. Any person who is claimed to have such ability is said to be a clairvoyant () ("one who sees cl ...

.Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Steiner met an herb gatherer, Felix Kogutzki, who spoke about the spiritual world "as one who had his own experience therein".

Writer and philosopher

In 1888, as a result of his work for the Kürschner edition of Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as t ...

's works, Steiner was invited to work as an editor at the Goethe archives in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), state of Thuringia, Germany. It is located in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt in the west and Jena in the east, approximately southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg an ...

. Steiner remained with the archive until 1896. As well as the introductions for and commentaries to four volumes of Goethe's scientific writings, Steiner wrote two books about Goethe's philosophy: ''The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception'' (1886), which Steiner regarded as the epistemological

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

foundation and justification for his later work, and ''Goethe's Conception of the World'' (1897). During this time he also collaborated in complete editions of the works of Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( , ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is best known for his 1818 work '' The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the phenomenal world as the pr ...

and the writer Jean Paul and wrote numerous articles for various journals.

In 1891, Steiner received a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Rostock, for his dissertation discussing

Fichte's concept of the ego,

In 1891, Steiner received a doctorate in philosophy at the University of Rostock, for his dissertation discussing

Fichte's concept of the ego,[ submitted to Heinrich von Stein, whose ''Seven Books of Platonism'' Steiner esteemed.][ Steiner's dissertation was later published in expanded form as ''Truth and Knowledge: Prelude to a Philosophy of Freedom'', with a dedication to ]Eduard von Hartmann

Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann, was a German philosopher, independent scholar and author of '' Philosophy of the Unconscious'' (1869). His notable ideas include the theory of the Unconscious and a pessimistic interpretation of the " best of ...

. Two years later, in 1894, he published ''Die Philosophie der Freiheit'' ( The Philosophy of Freedom ''or'' The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, the latter being Steiner's preferred English title), an exploration of epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

and ethics that suggested a way for humans to become spiritually free beings. Steiner later spoke of this book as containing implicitly, in philosophical form, the entire content of what he later developed explicitly as anthroposophy.

In 1896, Steiner declined an offer from Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche to help organize the Nietzsche archive in Naumburg. Her brother,

In 1896, Steiner declined an offer from Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche to help organize the Nietzsche archive in Naumburg. Her brother, Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his c ...

, was by that time '' non compos mentis''. Förster-Nietzsche introduced Steiner into the presence of the catatonic

Catatonia is a complex neuropsychiatric behavioral syndrome that is characterized by abnormal movements, immobility, abnormal behaviors, and withdrawal. The onset of catatonia can be acute or subtle and symptoms can wax, wane, or change during ...

philosopher; Steiner, deeply moved, subsequently wrote the book ''Friedrich Nietzsche, Fighter for Freedom''. Steiner later related that:

My first acquaintance with Nietzsche's writings belongs to the year 1889. Previous to that I had never read a line of his. Upon the substance of my ideas as these find expression in ''The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity'', Nietzsche's thought had not the least influence....Nietzsche's ideas of the ' eternal recurrence' and of ' Übermensch' remained long in my mind. For in these was reflected that which a personality must feel concerning the evolution and essential being of humanity when this personality is kept back from grasping the spiritual world by the restricted thought in the philosophy of nature characterizing the end of the 19th century....What attracted me particularly was that one could read Nietzsche without coming upon anything which strove to make the reader a 'dependent' of Nietzsche's.

In 1897, Steiner left the Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), state of Thuringia, Germany. It is located in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt in the west and Jena in the east, approximately southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg an ...

archives and moved to Berlin. He became part owner of, chief editor of, and an active contributor to the literary journal ''Magazin für Literatur'', where he hoped to find a readership sympathetic to his philosophy. Many subscribers were alienated by Steiner's unpopular support of Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

in the Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

[Gary Lachman, ''Rudolf Steiner'', Tarcher/Penguin 2007.] and the journal lost more subscribers when Steiner published extracts from his correspondence with anarchist John Henry Mackay.

Theosophical Society

In 1899, Steiner published an article, "Goethe's Secret Revelation", discussing the esoteric nature of Goethe's fairy tale '' The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily''. This article led to an invitation by the Count and Countess Brockdorff to speak to a gathering of Theosophists on the subject of Nietzsche. Steiner continued speaking regularly to the members of the

In 1899, Steiner published an article, "Goethe's Secret Revelation", discussing the esoteric nature of Goethe's fairy tale '' The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily''. This article led to an invitation by the Count and Countess Brockdorff to speak to a gathering of Theosophists on the subject of Nietzsche. Steiner continued speaking regularly to the members of the Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society, founded in 1875, is a worldwide body with the aim to advance the ideas of Theosophy in continuation of previous Theosophists, especially the Greek and Alexandrian Neo-Platonic philosophers dating back to 3rd century C ...

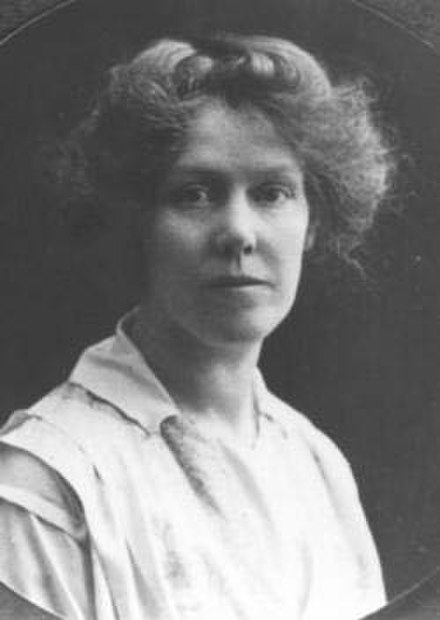

, becoming the head of its newly constituted German section in 1902 without ever formally joining the society.[ It was also in connection with this society that Steiner met and worked with Marie von Sivers, who became his second wife in 1914. By 1904, Steiner was appointed by Annie Besant to be leader of the Theosophical ''Esoteric Society'' for Germany and Austria. In 1904, Eliza, the wife of Helmuth von Moltke the Younger, became one of his favourite scholars. Through Eliza, Steiner met Helmuth, who served as the ]Chief of the German General Staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continu ...

from 1906 to 1914.

In contrast to mainstream Theosophy, Steiner sought to build a Western approach to spirituality based on the philosophical and mystical traditions of European culture. The German Section of the Theosophical Society grew rapidly under Steiner's leadership as he lectured throughout much of Europe on his spiritual science. During this period, Steiner maintained an original approach, replacing Madame Blavatsky's terminology with his own, and basing his spiritual research and teachings upon the Western esoteric and philosophical tradition. This and other differences, in particular Steiner's vocal rejection of Leadbeater Leadbeater is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Anne Leadbeater, Australian trauma recovery specialist

* Barrie Leadbeater (born 1943), English first-class cricketer and umpire

* Benjamin Leadbeater (1760–1837), British naturali ...

and Besant's claim that Jiddu Krishnamurti

Jiddu Krishnamurti (; 11 May 1895 – 17 February 1986) was a philosopher, speaker and writer. In his early life, he was groomed to be the new World Teacher, an advanced spiritual position in the theosophical tradition, but later rejected th ...

was the vehicle of a new ''Maitreya'', or world teacher, led to a formal split in 1912–13,[ when Steiner and the majority of members of the German section of the Theosophical Society broke off to form a new group, the Anthroposophical Society. Steiner took the name "Anthroposophy" from the title of a work of the Austrian philosopher ]Robert von Zimmermann

Robert von Zimmermann or Robert Zimmermann (November 2, 1824, Prague – September 1, 1898, Prague) was a Czech people, Czech-born Austrian philosopher.

The mathematician and philosopher, Bernard Bolzano, entrusted his unfinished work, ''Grössen ...

, published in Vienna in 1856. Despite his departure from the Theosophical Society, Steiner maintained his interest in Theosophy throughout his life.

Anthroposophical Society and its cultural activities

The Anthroposophical Society grew rapidly. Fueled by a need to find an artistic home for their yearly conferences, which included performances of plays written by Edouard Schuré and Steiner, the decision was made to build a theater and organizational center. In 1913, construction began on the first Goetheanum building, in Dornach, Switzerland. The building, designed by Steiner, was built to a significant part by volunteers. Steiner moved from Berlin

Berlin is Capital of Germany, the capital and largest city of Germany, both by area and List of cities in Germany by population, by population. Its more than 3.85 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European U ...

[Paull, John (2019]

Rudolf Steiner: At Home in Berlin

Journal of Biodynamics Tasmania. 132: 26-29. to Dornach in 1913 and lived there to the end of his life.[Paull, John (2018]

The Home of Rudolf Steiner: Haus Hansi

Journal of Biodynamics Tasmania, 126:19-23.

Steiner's lecture activity expanded enormously with the end of the war. Most importantly, from 1919 on Steiner began to work with other members of the society to found numerous practical institutions and activities, including the first Waldorf school, founded that year in Stuttgart, Germany. On New Year's Eve, 1922–1923, the Goetheanum burned to the ground; contemporary police reports indicate arson as the probable cause.education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

, performing arts ( eurythmy, speech, drama and music), the literary arts and humanities, mathematics, astronomy, science, and visual arts. Later sections were added for the social sciences, youth and agriculture.[1923/1924 Restructuring and deepening. Refounding of the Anthroposophical Society]

, Goetheanum website

Political engagement and social agenda

Steiner became a well-known and controversial public figure during and after World War I. In response to the catastrophic situation in post-war Germany, he proposed extensive social reforms through the establishment of a Threefold Social Order in which the cultural, political and economic realms would be largely independent. Steiner argued that a fusion of the three realms had created the inflexibility that had led to catastrophes such as World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. In connection with this, he promoted a radical solution in the disputed area of Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

, claimed by both Poland and Germany. His suggestion that this area be granted at least provisional independence led to his being publicly accused of being a traitor to Germany.

Steiner opposed Wilson's proposal to create new European nations based around ethnic groups, which he saw as opening the door to rampant nationalism. Steiner proposed, as an alternative:

Attacks, illness, and death

The National Socialist German Workers Party gained strength in Germany after the First World War. In 1919, a political theorist of this movement, Dietrich Eckart, attacked Steiner and suggested that he was a Jew.[Uwe Werner, ''Anthroposophen in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus'', Munich (1999), p. 7.] In 1921, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

attacked Steiner on many fronts, including accusations that he was a tool of the Jews, while other nationalist extremists in Germany called for a "war against Steiner". That same year, Steiner warned against the disastrous effects it would have for Central Europe if the National Socialists came to power.[ The 1923 ]Beer Hall Putsch

The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Munich Putsch,Dan Moorhouse, ed schoolshistory.org.uk, accessed 2008-05-31.Known in German as the or was a failed coup d'état by Nazi Party ( or NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler, Erich Ludendorff and oth ...

in Munich led Steiner to give up his residence in Berlin, saying that if those responsible for the attempted coup (Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

's Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

party) came to power in Germany, it would no longer be possible for him to enter the country.

From 1923 on, Steiner showed signs of increasing frailness and illness. He nonetheless continued to lecture widely, and even to travel; especially towards the end of this time, he was often giving two, three or even four lectures daily for courses taking place concurrently. Many of these lectures focused on practical areas of life such as education.[Lindenberg, Christoph, ''Rudolf Steiner: Eine Biographie'' Vol. II, Chapter 52. ]

Increasingly ill, he held his last lecture in late September, 1924. He continued work on his autobiography during the last months of his life; he died at Dornach on 30 March 1925.

Increasingly ill, he held his last lecture in late September, 1924. He continued work on his autobiography during the last months of his life; he died at Dornach on 30 March 1925.

Spiritual research

Steiner first began speaking publicly about spiritual experiences and phenomena in his 1899 lectures to the Theosophical Society. By 1901 he had begun to write about spiritual topics, initially in the form of discussions of historical figures such as the mystics of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. By 1904 he was expressing his own understanding of these themes in his essays and books, while continuing to refer to a wide variety of historical sources.

Steiner aimed to apply his training in mathematics, science, and philosophy to produce rigorous, verifiable presentations of those experiences. He believed that through freely chosen ethical

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of morality, right and wrong action (philosophy), behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, alo ...

disciplines and meditative training, anyone could develop the ability to experience the spiritual world, including the higher nature of oneself and others.creative

Creative may refer to:

*Creativity, phenomenon whereby something new and valuable is created

* "Creative" (song), a 2008 song by Leon Jackson

* Creative class, a proposed socioeconomic class

* Creative destruction, an economic term

* Creative dir ...

and free

Free may refer to:

Concept

* Freedom, having the ability to do something, without having to obey anyone/anything

* Freethought, a position that beliefs should be formed only on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism

* Emancipate, to procur ...

individual – free in the sense of being capable of actions motivated solely by love.Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends ...

, Schelling, and Goethe's phenomenological approach to science.humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at th ...

, in a novel way, to describe a systematic ("scientific") approach to spirituality. Steiner used the term ''Geisteswissenschaft'', generally translated into English as "spiritual science," to describe a discipline treating the spirit as something actual and real, starting from the premise that it is possible for human beings to penetrate behind what is sense-perceptible. He proposed that psychology, history, and the humanities generally were based on the direct grasp of an ideal reality, and required close attention to the particular period and culture which provided the distinctive character of religious qualities in the course of the evolution of consciousness. In contrast to William James' pragmatic approach to religious and psychic experience, which emphasized its idiosyncratic character, Steiner focused on ways such experience can be rendered more intelligible and integrated into human life.

Steiner proposed that an understanding of reincarnation and karma was necessary to understand psychology and that the form of external nature would be more comprehensible as a result of insight into the course of karma in the evolution of humanity. Beginning in 1910, he described aspects of karma relating to health, natural phenomena and free will, taking the position that a person is not bound by his or her karma, but can transcend this through actively taking hold of one's own nature and destiny. In an extensive series of lectures from February to September 1924, Steiner presented further research on successive reincarnations of various individuals and described the techniques he used for karma research.

Breadth of activity

After the First World War, Steiner became active in a wide variety of cultural contexts. He founded a number of schools, the first of which was known as the Waldorf school, which later evolved into a worldwide school network. He also founded a system of organic agriculture, now known as biodynamic agriculture, which was one of the first forms of modern organic farming. His work in medicine is based in pseudoscience and occult ideas. Even though his medical ideas led to the development of a broad range of complementary medications and supportive artistic and biographic therapies, they are considered ineffective by the medical community.modern architecture

Modern architecture, or modernist architecture, was an architectural movement or architectural style based upon new and innovative technologies of construction, particularly the use of glass, steel, and reinforced concrete; the idea that for ...

, and other anthroposophical architects have contributed thousands of buildings to the modern scene.

Steiner's literary estate is broad. Steiner's writings, published in about forty volumes, include books, essays, four plays ('mystery dramas'), mantric verse, and an autobiography. His collected lectures, making up another approximately 300 volumes, discuss a wide range of themes. Steiner's drawings, chiefly illustrations done on blackboards during his lectures, are collected in a separate series of 28 volumes. Many publications have covered his architectural legacy and sculptural work.[

]

Education

As a young man, Steiner was a private tutor and a lecturer on history for the Berlin ''Arbeiterbildungsschule'',

As a young man, Steiner was a private tutor and a lecturer on history for the Berlin ''Arbeiterbildungsschule'',Herbartian

Johann Friedrich Herbart (; 4 May 1776 – 14 August 1841) was a German philosopher, psychologist and founder of pedagogy as an academic discipline.

Herbart is now remembered amongst the post-Kantian philosophers mostly as making the greatest ...

pedagogy prominent in Europe during the late nineteenth century,Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the Un ...

by Professor Millicent Mackenzie. He subsequently presented a teacher training course at Torquay in 1924 at an Anthroposophy Summer School organised by Eleanor Merry

Eleanor Merry (17 December 1873 in Eton, Berkshire, UK – 16 June 1956 in Frinton-on-Sea, Essex, UK), was an English poet, artist, musician and anthroposophist with a strong Celtic impulse and interest in esoteric wisdom. She studied in Vie ...

.[Paull, John (2018]

Torquay: In the Footsteps of Rudolf Steiner

Journal of Biodynamics Tasmania. 125 (Mar): 26–31. The Oxford Conference and the Torquay teacher training led to the founding of the first Waldorf schools in Britain. During Steiner's lifetime, schools based on his educational principles were also founded in Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

, Essen

Essen (; Latin: ''Assindia'') is the central and, after Dortmund, second-largest city of the Ruhr, the largest urban area in Germany. Its population of makes it the fourth-largest city of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf and ...

, The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a list of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's ad ...

and London; there are now more than 1000 Waldorf schools worldwide.

Biodynamic agriculture

In 1924, a group of farmers concerned about the future of agriculture requested Steiner's help. Steiner responded with a lecture series on an ecological and sustainable approach to agriculture that increased soil fertility without the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides.Australasia

Australasia is a region that comprises Australia, New Zealand and some neighbouring islands in the Pacific Ocean. The term is used in a number of different contexts, including geopolitically, physiogeographically, philologically, and ecolo ...

.[Paull, John (2011]

"Biodynamic Agriculture: The Journey from Koberwitz to the World, 1924–1938"

''Journal of Organic Systems'', 2011, 6(1):27–41.

A central aspect of biodynamics is that the farm as a whole is seen as an organism, and therefore should be a largely self-sustaining system, producing its own manure

Manure is organic matter that is used as organic fertilizer in agriculture. Most manure consists of animal feces; other sources include compost and green manure. Manures contribute to the fertility of soil by adding organic matter and nut ...

and animal feed. Plant or animal disease is seen as a symptom of problems in the whole organism. Steiner also suggested timing such agricultural activities as sowing, weeding, and harvesting to utilize the influences on plant growth of the moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

and planets

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a young ...

; and the application of natural materials prepared in specific ways to the soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former ...

, compost

Compost is a mixture of ingredients used as plant fertilizer and to improve soil's physical, chemical and biological properties. It is commonly prepared by decomposing plant, food waste, recycling organic materials and manure. The resulting ...

, and crops, with the intention of engaging non-physical beings and elemental forces. He encouraged his listeners to verify such suggestions empirically, as he had not yet done.alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world ...

or magic akin to geomancy.[ (Translation: "Blood and Beans: The paradigm shift in the Ministry of Renate Künast replaces science with occultism")]

Anthroposophical medicine

From the late 1910s, Steiner was working with doctors to create a new approach to medicine. In 1921, pharmacists and physicians gathered under Steiner's guidance to create a pharmaceutical company called '' Weleda'' which now distributes naturopathic medical and beauty products worldwide. At around the same time, Dr. Ita Wegman founded a first anthroposophic medical clinic (now the Ita Wegman Clinic) in Arlesheim

Arlesheim is a town and a municipality in the district of Arlesheim in the canton of Basel-Country in Switzerland. Its cathedral chapter seat, bishop's residence and cathedral (1681 / 1761) are listed as a heritage site of national significanc ...

. Anthroposophic medicine is practiced in some 80 countries. It is a form of alternative medicine

Alternative medicine is any practice that aims to achieve the healing effects of medicine despite lacking biological plausibility, testability, repeatability, or evidence from clinical trials. Complementary medicine (CM), complementary and ...

based on pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claim ...

and occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism ...

notions.[ ''Cited in'' ]

Social reform

For a period after World War I, Steiner was active as a lecturer on social reform. A petition expressing his basic social ideas was widely circulated and signed by many cultural figures of the day, including Hermann Hesse

Hermann Karl Hesse (; 2 July 1877 – 9 August 1962) was a German-Swiss poet, novelist, and painter. His best-known works include ''Demian'', '' Steppenwolf'', '' Siddhartha'', and '' The Glass Bead Game'', each of which explores an individual' ...

.

In Steiner's chief book on social reform, ''Toward Social Renewal'', he suggested that the cultural, political and economic spheres of society need to work together as consciously cooperating yet independent entities, each with a particular task: political institutions should be democratic, establish political equality and protect human rights

Human rights are moral principles or normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for certain standards of hu ...

; cultural institutions should nurture the free and unhindered development of science, art, education and religion; and economic institutions should enable producers, distributors, and consumers to cooperate voluntarily to provide efficiently for society's needs.[Robert McDermott, ''The Essential Steiner'', Harper San Francisco 1984 ] He saw this division of responsibility as a vital task which would take up consciously the historical trend toward the mutual independence of these three realms. Steiner also gave suggestions for many specific social reforms.

Steiner proposed that societal well-being fundamentally depends upon a relationship of mutuality between the individuals and the community as a whole:

He expressed another aspect of this in the following motto:

Architecture and visual arts

Steiner designed 17 buildings, including the First and Second Goetheanums. These two buildings, built in Dornach, Switzerland, were intended to house significant theater spaces as well as a "school for spiritual science". Three of Steiner's buildings have been listed amongst the most significant works of modern architecture.

His primary sculptural work is ''The Representative of Humanity'' (1922), a nine-meter high wood sculpture executed as a joint project with the sculptor Edith Maryon. This was intended to be placed in the first Goetheanum. It shows a central human figure, the "Representative of Humanity," holding a balance between opposing tendencies of expansion and contraction personified as the beings of Lucifer and Ahriman. It was intended to show, in conscious contrast to Michelangelo's ''

Steiner designed 17 buildings, including the First and Second Goetheanums. These two buildings, built in Dornach, Switzerland, were intended to house significant theater spaces as well as a "school for spiritual science". Three of Steiner's buildings have been listed amongst the most significant works of modern architecture.

His primary sculptural work is ''The Representative of Humanity'' (1922), a nine-meter high wood sculpture executed as a joint project with the sculptor Edith Maryon. This was intended to be placed in the first Goetheanum. It shows a central human figure, the "Representative of Humanity," holding a balance between opposing tendencies of expansion and contraction personified as the beings of Lucifer and Ahriman. It was intended to show, in conscious contrast to Michelangelo's ''Last Judgment

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

'', Christ as mute and impersonal such that the beings that approach him must judge themselves. The sculpture is now on permanent display at the Goetheanum.

Steiner's blackboard drawings were unique at the time and almost certainly not originally intended as art works. Joseph Beuys' work, itself heavily influenced by Steiner, has led to the modern understanding of Steiner's drawings as artistic objects.

Performing arts

Steiner wrote four mystery plays

Mystery plays and miracle plays (they are distinguished as two different forms although the terms are often used interchangeably) are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the represen ...

between 1909 and 1913: ''The Portal of Initiation'', ''The Souls' Probation'', ''The Guardian of the Threshold'' and ''The Soul's Awakening'', modeled on the esoteric dramas of Edouard Schuré, Maurice Maeterlinck, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

. Steiner's plays continue to be performed by anthroposophical groups in various countries, most notably (in the original German) in Dornach, Switzerland and (in English translation) in Spring Valley, New York and in Stroud and Stourbridge in the U.K.

In collaboration with Marie von Sivers, Steiner also founded a new approach to acting, storytelling, and the recitation of poetry. His last public lecture course, given in 1924, was on speech and drama. The Russian actor, director, and acting coach Michael Chekhov based significant aspects of his method of acting on Steiner's work.

Together with Marie von Sivers, Rudolf Steiner also developed the art of eurythmy, sometimes referred to as "visible speech and song". According to the principles of eurythmy, there are archetypal movements or gestures that correspond to every aspect of speech – the sounds (or phonemes

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-wes ...

), the rhythms, and the grammatical function – to every "soul quality" – joy, despair, tenderness, etc. – and to every aspect of music – tones, intervals, rhythms, and harmonies.

Esoteric schools

Steiner was founder and leader of the following:

* His independent ''Esoteric School'' of the Theosophical Society, founded in 1904. This school continued after the break with Theosophy but was disbanded at the start of World War I.

* A lodge called ''Mystica Aeterna'' within the Masonic Order of Memphis and Mizraim, which Steiner led from 1906 until around 1914. Steiner added to the Masonic rite a number of Rosicrucian references.

* The School of Spiritual Science of the Anthroposophical Society, founded in 1923 as a further development of his earlier Esoteric School. This was originally constituted with a general section and seven specialized sections for education, literature, performing arts, natural sciences, medicine, visual arts, and astronomy.

Philosophical ideas

Goethean science

Goethean science is not science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

, but pseudoscience.color theory

In the visual arts, color theory is the body of practical guidance for color mixing and the visual effects of a specific color combination. Color terminology based on the color wheel and its geometry separates colors into primary color, se ...

;

#obtuse criticism of the theory of relativity;

#weird ideas about motions of the planets;

#supporting vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

;

#doubting germ theory;phenomenological

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

in nature, rather than theory or model-based. He developed this conception further in several books, ''The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception'' (1886) and ''Goethe's Conception of the World'' (1897), particularly emphasizing the transformation in Goethe's approach from the physical sciences, where experiment played the primary role, to plant biology, where both accurate perception and imagination were required to find the biological archetypes (''Urpflanze''). He postulated that Goethe had sought, but been unable to fully find, the further transformation in scientific thinking necessary to properly interpret and understand the animal kingdom.[Johannes Hemleben, ''Rudolf Steiner: A documentary biography'', Henry Goulden Ltd, 1975, , pp. 37–49 and pp. 96–100 (German edition: Rowohlt Verlag, 1990, )] Steiner emphasized the role of evolutionary thinking in Goethe's discovery of the intermaxillary bone

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal h ...

in human beings; Goethe expected human anatomy to be an evolutionary transformation of animal anatomy.[ Steiner defended Goethe's qualitative description of color as arising synthetically from the polarity of light and darkness, in contrast to Newton's particle-based and analytic conception.

]

Knowledge and freedom

Steiner approached the philosophical questions of knowledge

Knowledge can be defined as awareness of facts or as practical skills, and may also refer to familiarity with objects or situations. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional knowledge, is often defined as true belief that is disti ...

and freedom in two stages. In his dissertation, published in expanded form in 1892 as ''Truth and Knowledge'', Steiner suggests that there is an inconsistency between Kant's philosophy, which posits that all knowledge is a representation of an essential verity inaccessible to human consciousness, and modern science, which assumes that all influences can be found in the sensory and mental world to which we have access. Steiner considered Kant's philosophy of an inaccessible beyond ("Jenseits-Philosophy") a stumbling block in achieving a satisfying philosophical viewpoint.

Steiner postulates that the world is essentially an indivisible unity, but that our consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience and awareness of internal and external existence. However, the lack of definitions has led to millennia of analyses, explanations and debates by philosophers, theologians, linguisticians, and scien ...

divides it into the sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the central nervous system rec ...

-perceptible appearance, on the one hand, and the formal nature accessible to our thinking, on the other. He sees in thinking itself an element that can be strengthened and deepened sufficiently to penetrate all that our senses do not reveal to us. Steiner thus considered what appears to human experience as a division between the spiritual and natural worlds to be a conditioned result of the structure of our consciousness, which separates perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system, ...

and thinking. These two faculties give us not two worlds, but two complementary views of the same world; neither has primacy and the two together are necessary and sufficient to arrive at a complete understanding of the world. In thinking about perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous system, ...

(the path of natural science) and perceiving the process of thinking (the path of spiritual training), it is possible to discover a hidden inner unity between the two poles of our experience.[

Steiner affirms ]Darwin

Darwin may refer to:

Common meanings

* Charles Darwin (1809–1882), English naturalist and writer, best known as the originator of the theory of biological evolution by natural selection

* Darwin, Northern Territory, a territorial capital city i ...

's and Haeckel's evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary perspectives but extended this beyond its materialistic consequences; he sees human consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience and awareness of internal and external existence. However, the lack of definitions has led to millennia of analyses, explanations and debates by philosophers, theologians, linguisticians, and scien ...

, indeed, all human culture, as a product of natural evolution that transcends itself. For Steiner, nature becomes self-conscious in the human being. Steiner's description of the nature of human consciousness thus closely parallels that of Solovyov Solovyov, Solovyev, Solovjev, or Soloviev (Russian: Соловьёв) is a Russian masculine surname, its feminine forms are Solovyova, Solovyeva or Solovieva. It derives from the first name or nickname Solovei (соловей), which also means ni ...

.

Spiritual science

In his earliest works, Steiner already spoke of the "natural and spiritual worlds" as a unity.

In his earliest works, Steiner already spoke of the "natural and spiritual worlds" as a unity.soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '':wikt:soul, soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The ea ...

and spirit;

* the path of spiritual development;

* spiritual influences on world-evolution and history; and

* reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is ...

and karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptively ...

.

Steiner emphasized that there is an objective natural and spiritual world that can be known, and that perceptions of the spiritual world and incorporeal beings are, under conditions of training comparable to that required for the natural sciences, including self-discipline, replicable by multiple observers. It is on this basis that spiritual science is possible, with radically different epistemological foundations than those of natural science. He believed that natural science was correct in its methods but one-sided for exclusively focusing on sensory phenomena, while mysticism was vague in its methods, though seeking to explore the inner and spiritual life. Anthroposophy was meant to apply the systematic methods of the former to the content of the latter

For Steiner, the cosmos is permeated and continually transformed by the creative activity of non-physical processes and spiritual beings. For the human being to become conscious of the objective reality of these processes and beings, it is necessary to creatively enact and reenact, within, their creative activity. Thus objective spiritual knowledge always entails creative inner activity.logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premis ...

al understanding, so that those who do not have access to the spiritual experiences underlying anthroposophical research can make independent evaluations of the latter's results.[Peter Schneider, ''Einführung in die Waldorfpädagogik'', ] Spiritual training is to support what Steiner considered the overall purpose of human evolution, the development of the mutually interdependent qualities of love and freedom.[Robert A. McDermott, "Rudolf Steiner and Anthroposophy", in Faivre and Needleman, ''Modern Esoteric Spirituality'', , p. 288ff]

Steiner and Christianity

Steiner appreciated the ritual of the mass he experienced while serving as an altar boy from school age until he was ten years old, and this experience remained memorable for him as a genuinely spiritual one, contrasting with his irreligious family life.[

]

Christ and human evolution

Steiner describes Christ as the unique pivot and meaning of earth's evolutionary processes and human history, redeeming the Fall from Paradise

In religion, paradise is a place of exceptional happiness and delight. Paradisiacal notions are often laden with pastoral imagery, and may be cosmogonical or eschatological or both, often compared to the miseries of human civilization: in paradis ...

.[Carlo Willmann, ''Waldorfpädagogik: Theologische und religionspädagogische Befunde'', Kölner Veröffentlichungen zur Religionsgeschichte, Volume 27, , especially Chapters 1.3, 1.4] He understood the Christ as a being that unifies and inspires all religions, not belonging to a particular religious faith. To be "Christian" is, for Steiner, a search for balance between polarizing extremes[

Central principles of his understanding include:

*The being of Christ is central to ''all'' religions, though called by different names by each.

*Every religion is valid and true for the time and cultural context in which it was born.

*Historical forms of Christianity need to be transformed in our times in order to meet the ongoing evolution of humanity.

In Steiner's esoteric cosmology, the spiritual development of humanity is interwoven in and inseparable from the cosmological development of the universe. Continuing the evolution that led to humanity being born out of the natural world, the Christ being brings an impulse enabling human consciousness of the forces that act creatively, but unconsciously, in nature.

]

Divergence from conventional Christian thought

Steiner's views of Christianity diverge from conventional Christian thought in key places, and include gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

elements.[ However, unlike many gnostics, Steiner affirms the unique and actual physical Incarnation of Christ in Jesus at the beginning of the Christian era.

One of the central points of divergence with conventional Christian thought is found in Steiner's views on reincarnation and karma.

Steiner also posited two different Jesus children involved in the Incarnation of the Christ: one child descended from Solomon, as described in the ]Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew), or simply Matthew. It is most commonly abbreviated as "Matt." is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel's Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people and ...

; the other child from Nathan, as described in the Gospel of Luke

The Gospel of Luke), or simply Luke (which is also its most common form of abbreviation). tells of the origins, birth, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ. Together with the Acts of the Apostles, it makes up a two ...

.David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

to Jesus.

Steiner's view of the second coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messi ...

of Christ is also unusual. He suggested that this would not be a physical reappearance, but rather, meant that the Christ being would become manifest in non-physical form, in the " etheric realm" – i.e. visible to spiritual vision and apparent in community life – for increasing numbers of people, beginning around the year 1933. He emphasized that the future would require humanity to recognize this Spirit of Love in all its genuine forms, regardless of how this is named. He also warned that the traditional name, "Christ", might be used, yet the true essence of this Being of Love ignored.[

]

The Christian Community

In the 1920s, Steiner was approached by Friedrich Rittelmeyer, a Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

pastor with a congregation in Berlin, who asked if it was possible to create a more modern form of Christianity. Soon others joined Rittelmeyer – mostly Protestant pastors and theology students, but including several Roman Catholic priests. Steiner offered counsel on renewing the spiritual potency of the sacraments while emphasizing freedom of thought and a personal relationship to religious life. He envisioned a new synthesis of Catholic and Protestant approaches to religious life, terming this "modern, Johannine Christianity".

Reception

Steiner's work has influenced a broad range of notable personalities. These include:

* philosophers

Steiner's work has influenced a broad range of notable personalities. These include:

* philosophers Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (; 14 January 1875 – 4 September 1965) was an Alsatian-German/French polymath. He was a theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician. A Lutheran minister, Schwei ...

, Owen Barfield and Richard Tarnas

Richard Theodore Tarnas is a cultural historian and astrologer known for his books '' The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas That Have Shaped Our World View'' and '' Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View''. Tarnas i ...

;Saul Bellow

Saul Bellow (born Solomon Bellows; 10 July 1915 – 5 April 2005) was a Canadian-born American writer. For his literary work, Bellow was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, the Nobel Prize for Literature, and the National Medal of Arts. He is the only w ...

, Andrej Belyj, Michael Ende, Selma Lagerlöf, Edouard Schuré, David Spangler, and William Irwin Thompson;Maria Schüppel Maria Schüppel (1923 – 27 June 2011) was a German composer, educator, pianist and pioneering music therapist who composed works for lyre and voice, and experimented with electronic music.

Schüppel was born in Chemnitz

Chemnitz (; from 195 ...

* economist Leonard Read;

* ecologist Rachel Carson;[Layla Alexander Garrett on Tarkovsky](_blank)

, Nostalgia.com

* composers Jonathan Harvey and Viktor Ullmann; and

* conductor Bruno Walter.

Olav Hammer, though sharply critical of esoteric movements generally, terms Steiner "arguably the most historically and philosophically sophisticated spokesperson of the Esoteric Tradition."[ See also p. 98, where Hammer states that – unusually for founders of esoteric movements – Steiner's self-descriptions of the origins of his thought and work correspond to the view of external historians.]

Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (; 14 January 1875 – 4 September 1965) was an Alsatian-German/French polymath. He was a theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician. A Lutheran minister, Schwei ...

wrote that he and Steiner had in common that they had "taken on the life mission of working for the emergence of a true culture enlivened by the ideal of humanity and to encourage people to become truly thinking beings". However, Schweitzer was not an adept of mysticism or occultism, but of Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

rationalism.education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. ...

, and agriculture ( Biodynamic agriculture).[Paull, John (2011]

Rudolf Steiner - Alchemy of the Everyday - Kosmos - A photographic review of the exhibition

/ref> The exhibition opened in 2011 at the Kunstmuseum in Stuttgart, Germany,[Paull, John (2011]

"A Postcard from Stuttgart: Rudolf Steiner's 150th anniversary exhibition 'Kosmos'"

Journal of Bio-Dynamics Tasmania, 103 (September), pp. 8–11.

Scientism

Olav Hammer has criticized as scientism Steiner's claim to use scientific methodology to investigate spiritual phenomena that were based upon his claims of clairvoyant experience.[ Steiner regarded the observations of spiritual research as more dependable (and above all, consistent) than observations of physical reality. However, he did consider spiritual research to be fallible,][Helmut Zander, ''Anthroposophie in Deutschland'', Göttingen, 2007, .] and held the view that anyone capable of thinking logically was in a position to correct errors by spiritual researchers.

Race and ethnicity

Steiner's work includes both universalist, humanist elements and racial assumptions.["Es hängt dabei von den Interessen der Leser ab, ob die Anthroposophie rassistisch interpretiert wird oder nicht." Helmut Zander, "Sozialdarwinistische Rassentheorien aus dem okkulten Untergrund des Kaiserreichs", in Puschner et al., Handbuch zur "Völkischen Bewegung" 1871–1918: 1996.] Steiner considered that by dint of its shared language and culture, each people has a unique essence, which he called its soul or spirit.[ He saw race as a physical manifestation of humanity's spiritual evolution, and at times discussed race in terms of complex hierarchies that were largely derived from 19th century biology, anthropology, philosophy and theosophy. However, he consistently and explicitly subordinated race, ethnicity, gender, and indeed all hereditary factors, to individual factors in development.][ For Steiner, human individuality is centered in a person's unique biography, and he believed that an individual's experiences and development are not bound by a single lifetime or the qualities of the physical body.][Lorenzo Ravagli, ''Zanders Erzählungen'', Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag 2009, , pp. 184f]

Steiner occasionally characterized specific races, nations and ethnicities in ways that have been deemed racist by critics. This includes descriptions by him of certain races and ethnic groups as flowering, others as backward, or destined to degenerate or disappear.[ He presented explicitly hierarchical views of the spiritual evolution of different races, including—at times, and inconsistently—portraying the white race, ]European culture

The culture of Europe is rooted in its art, architecture, film, different types of music, economics, literature, and philosophy. European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage".

Definition ...

or Germanic culture as representing the high point of human evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

as of the early 20th century, although he did describe them as destined to be superseded by future cultures.[

Throughout his life Steiner consistently emphasized the core spiritual unity of all the world's peoples and sharply criticized racial prejudice. He articulated beliefs that the individual nature of any person stands higher than any racial, ethnic, national or religious affiliation.]ethnicity

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

are transient and superficial, and not essential aspects of the individual,[ was partly rooted in his conviction that each individual reincarnates in a variety of different peoples and races over successive lives, and that each of us thus bears within him or herself the heritage of many races and peoples.][ Toward the end of his life, Steiner predicted that race will rapidly lose any remaining significance for future generations.][ In Steiner's view, culture is universal, and explicitly not ethnically based, and he vehemently criticized imperialism.

In the context of his ethical individualism, Steiner considered "race, folk, ethnicity and gender" to be general, describable categories into which individuals may choose to fit, but from which free human beings can and will liberate themselves.][

]

Judaism

During the years when Steiner was best known as a literary critic, he published a series of articles attacking various manifestations of antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and criticizing some of the most prominent anti-Semites of the time as "barbaric" and "enemies of culture".["Hammer und Hakenkreuz – Anthroposophie im Visier der völkischen Bewegung"]

''Südwestrundfunk'', 26 November 2004 Steiner suggested that Jewish cultural and social life had lost all contemporary relevance and promoted full assimilation

Assimilation may refer to:

Culture

*Cultural assimilation, the process whereby a minority group gradually adapts to the customs and attitudes of the prevailing culture and customs

**Language shift, also known as language assimilation, the progre ...

of the Jewish people into the nations in which they lived. Steiner was a critic of his contemporary Theodor Herzl's goal of a Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in J ...

state, and indeed of any ethnically determined state, as he considered ethnicity to be an outmoded basis for social life and civic identity.

Towards the end of Steiner's life and after his death, there were massive defamatory press attacks mounted on him by early Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

leaders (including Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

) and other right-wing nationalists. These criticized Steiner's thought and anthroposophy as being incompatible with Nazi racial ideology, and charged him with being influenced by his close connections with Jews and even (falsely) that he himself was Jewish.[

But the truth was that while Anthroposophists complained of bad press, they were to a surprising extent let be by the Nazi regime, "including outspokenly supportive pieces in the ''Völkischer Beobachter''".]Sicherheitsdienst

' (, ''Security Service''), full title ' (Security Service of the '' Reichsführer-SS''), or SD, was the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Established in 1931, the SD was the first Nazi intelligence organization ...

purists argued largely in vain against Anthroposophy.

Writings (selection)

: ''See also Works in German''

The standard edition of Steiner's Collected Works constitutes about 422 volumes. This includes 44 volumes of his writings (books, essay, plays, and correspondence), over 6000 lectures, and some 80 volumes (some still in production) documenting his artistic work (architecture, drawings, paintings, graphic design, furniture design, choreography, etc.).

''Goethean Science''

(1883–1897)

''Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe's World-Conception''

(1886)

''Truth and Knowledge''

doctoral thesis, (1892)

''Intuitive Thinking as a Spiritual Path''

also published as the ''Philosophy of Spiritual Activity'' and the '' Philosophy of Freedom'' (1894)

''Mysticism at the Dawn of Modern Age''

()

''Christianity as Mystical Fact''

(1902)

''Theosophy: An Introduction to the Spiritual Processes in Human Life and in the Cosmos''

(1904)

''How to Know Higher Worlds: A Modern Path of Initiation''

(1904–5)

''Cosmic Memory: Prehistory of Earth and Man''

(1904) (Also published as ''The Submerged Continents of Atlantis and Lemuria'')

(1907)

(1908) (English edition trans. by Max Gysi)

(1909) (English edition trans. by Max Gysi)

''An Outline of Esoteric Science''

(1910)

(1913)

(1919)

(1925)

* ''Reincarnation and Immortality'', Rudolf Steiner Publications. (1970)

Rudolf Steiner Publications, 1977, (Originally, ''The Story of my Life'')

* Rudolf Steiner,

' Garber Communications; 2nd revised edition (July 1985)

See also

* Esotericism

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas a ...

* Guardian of the Threshold

The Guardian of the Threshold is a menacing figure that is described by a number of esoteric teachers. The term "Guardian of the Threshold", often called "dweller on the threshold", indicates a spectral image which is supposed to manifest itself a ...

* Rudolf Steiner and colour mysticism

* Martinus

References

Notes

Citations

Further reading

* Almon, Joan (ed.) ''Meeting Rudolf Steiner'', firsthand experiences compiled from the ''Journal for Anthroposophy'' since 1960,

* Anderson, Adrian: ''Rudolf Steiner Handbook'', Port Campbell Press, 2014,

* Childs, Gilbert, ''Rudolf Steiner: His Life and Work'',

* Davy, Adams and Merry, ''A Man before Others: Rudolf Steiner Remembered''. Rudolf Steiner Press, 1993.

* Easton, Stewart, ''Rudolf Steiner: Herald of a New Epoch'',

* Hemleben, Johannes and Twyman, Leo, ''Rudolf Steiner: An Illustrated Biography''. Rudolf Steiner Press, 2001.

* Kries, Mateo and Vegesack, Alexander von, ''Rudolf Steiner: Alchemy of the Everyday'', Weil am Rhein: Vitra Design Museum, 2010.

* Lachman, Gary, ''Rudolf Steiner: An Introduction to His Life and Work'', 2007,

* Lindenberg, Christoph, ''Rudolf Steiner: Eine Biographie'' (2 vols.). Stuttgart, 1997,

* Lissau, Rudi, ''Rudolf Steiner: Life, Work, Inner Path and Social Initiatives''. Hawthorne Press, 2000.

* McDermott, Robert, ''The Essential Steiner''. Harper Press, 1984

* Prokofieff, Sergei O., ''Rudolf Steiner and the Founding of the New Mysteries''. Temple Lodge Publishing, 1994.

* Seddon, Richard, ''Rudolf Steiner''. North Atlantic Books, 2004.

* Shepherd, A. P., ''Rudolf Steiner: Scientist of the Invisible''. Inner Traditions, 1990.

* Schiller, Paul, ''Rudolf Steiner and Initiation''. SteinerBooks, 1990.

* Selg, Peter, ''Rudolf Steiner as a Spiritual Teacher. From Recollections of Those Who Knew Him'', SteinerBooks Publishing, 2010.

* Sokolina, Anna, ed. ''Architecture and Anthroposophy''. 2 editions. 268p. 348 ills. (In Russian with the Summary in English.) Moscow: KMK, 2001 ; 2010