The Republican Party, also referred to as the GOP ("Grand Old Party"), is one of the

two

2 (two) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number following 1 and preceding 3. It is the smallest and only even prime number. Because it forms the basis of a duality, it has religious and spiritual significance in many cultur ...

major contemporary

political parties in the United States. The GOP was founded in 1854 by

anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

activists who opposed the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

, which allowed for the potential expansion of

chattel slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

into the western territories. Since

Ronald Reagan's

presidency in the 1980s,

conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

has been the dominant ideology of the GOP.

It has been the main political rival of the

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

since the mid-1850s.

The Republican Party's intellectual predecessor is considered to be

Northern members of the

Whig Party, with Republican presidents

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

,

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

,

Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James ...

, and

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

all being Whigs before switching to the party, from which they were elected. The collapse of the Whigs, which had previously been one of the two major parties in the country, strengthened the party's electoral success. Upon its founding, it supported

classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, econo ...

and

economic reform

Microeconomic reform (or often just economic reform) comprises policies directed to achieve improvements in economic efficiency, either by eliminating or reducing distortions in individual sectors of the economy or by reforming economy-wide polici ...

while

opposing the expansion of slavery.

The Republican Party initially consisted of Northern

Protestants, factory workers, professionals, businessmen, prosperous farmers, and from 1866,

former black slaves. It had almost no presence in the

Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

at its inception, but was very successful in the

Northern United States where, by 1858, it had enlisted former Whigs and former

Free Soil

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

Democrats to form majorities in nearly every state in

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the Can ...

. While both parties adopted

pro-business

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers are ...

policies in the 19th century, the early GOP was distinguished by its support for the

national banking system, the

gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

,

railroads

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prep ...

, and

high tariffs. It did not openly oppose slavery in the Southern states before the start of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

—stating that it only opposed the spread of slavery into the territories or into the Northern states—but was widely seen as sympathetic to the

abolitionist cause. Seeing a future threat to the practice with the election of Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican president, many states in the South declared secession and joined the

Confederacy. Under the leadership of Lincoln and a Republican Congress, it led the fight to destroy the Confederacy during the American Civil War, preserving the

Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

and

abolishing slavery. The aftermath saw the party largely dominate the national political scene

until 1932.

In 1912, former Republican president

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

formed the

Progressive ("Bull Moose") Party after

being rejected by the GOP and

ran unsuccessfully as a third-party presidential candidate, feeling that

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

had betrayed the values of the Republican Party and calling for

social reforms similar to those he had enacted during his presidency. After 1912, many Roosevelt supporters left the Republican Party, and the Party underwent an ideological shift to the right, beginning its 20th-century trend towards

conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

. The GOP lost its congressional majorities during the

Great Depression (1929–1940) when the Democrats'

New Deal programs proved popular.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

presided over a period of economic prosperity after the war. Following the Democrats'

voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

program in the 1960s, Southern states

became more reliably Republican in presidential politics. After the Supreme Court's 1973 decision in ''

Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and s ...

'', the Republican Party opposed

abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pre ...

in its party platform and grew its support among

evangelicals.

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

carried 49 states in 1972 with his

silent majority

The silent majority is an unspecified large group of people in a country or group who do not express their opinions publicly. The term was popularized by U.S. President Richard Nixon in a televised address on November 3, 1969, in which he said, " ...

, even as the

Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

dogged his campaign leading to his resignation. After

Gerald Ford pardoned Nixon, he lost reelection and the Republicans would not regain power and realign the political landscape once more until 1980 with the election of Reagan.

The party currently supports

deregulation,

lower taxes,

gun rights

The right to keep and bear arms (often referred to as the right to bear arms) is a right for people to possess weapons (arms) for the preservation of life, liberty, and property. The purpose of gun rights is for self-defense, including securi ...

,

restrictions on immigration,

restrictions on abortion, restrictions on

labor unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (su ...

, and increased

military spending

A military budget (or military expenditure), also known as a defense budget, is the amount of financial resources dedicated by a state to raising and maintaining an armed forces or other methods essential for defense purposes.

Financing milit ...

. It has taken varying positions on

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

and

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

throughout history.

In the modern day, its demographic base skews towards people who live in

rural areas

In general, a rural area or a countryside is a geographic area that is located outside towns and cities. Typical rural areas have a low population density and small settlements. Agricultural areas and areas with forestry typically are describ ...

,

white evangelical Christians, and men, particularly

white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

men.

The party has gained significant support among members of the

white working class and lost support among

affluent

Wealth is the abundance of valuable financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions. This includes the core meaning as held in the originating Old English word , which is from an I ...

and

college-educated whites since the 1980s.

As of 2022, the GOP controls 28

state governorships, 30

state legislatures, and 23 state

government trifecta

A government trifecta is a political situation in which the same political party controls the executive branch and both chambers of the legislative branch in countries that have a bicameral legislature and an executive that is not fused. The ter ...

s. Six of the nine sitting

U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

justices were appointed by Republican presidents. The Republican Party is a member of the

International Democrat Union

The International Democrat Union (IDU) is an international alliance of centre-right political parties. Headquartered in Munich, Germany, the IDU consists of 84 full and associate members from 65 countries. It is chaired by Stephen Harper, ...

, an

international alliance of

centre-right

Centre-right politics lean to the right of the political spectrum, but are closer to the centre. From the 1780s to the 1880s, there was a shift in the Western world of social class structure and the economy, moving away from the nobility and ...

political parties. Its most recent presidential nominee was

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

, who

was the 45th U.S. president from 2017 to 2021. There have been 19 Republican presidents, the most from any one political party.

History

19th century

The Republican Party was founded in the northern states in 1854 by forces opposed to the expansion of

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, ex-

Whigs and ex-

Free Soil

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

ers. The Republican Party quickly became the principal opposition to the dominant

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

and the briefly popular

Know Nothing Party. The party grew out of opposition to the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

, which repealed the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

and opened

Kansas Territory and

Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

to slavery and future admission as slave states. They denounced the expansion of slavery as a great evil, but did not call for ending it in the southern states. While opposition to the expansion of slavery was the most consequential founding principal of the party, like the Whig party it replaced, Republicans also called for economic and social

modernization.

The first public meeting of the general

anti-Nebraska movement The Anti-Nebraska movement was a political alignment in the United States formed in opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 and to its repeal of the Missouri Compromise provision forbidding slavery in U.S. territories north of latitude 36° ...

, at which the name Republican was proposed, was held on March 20, 1854, at the

Little White Schoolhouse in

Ripon, Wisconsin. The name was partly chosen to pay homage to

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was previously the natio ...

's

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the earl ...

. The first official party convention was held on July 6, 1854, in

Jackson, Michigan.

The party emerged from the great political realignment of the mid-1850s. Historian

William Gienapp argues that the great realignment of the 1850s began before the Whigs' collapse, and was caused not by politicians but by voters at the local level. The central forces were ethno-cultural, involving tensions between pietistic

Protestants versus liturgical

Catholics,

Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

and

Episcopalians

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

regarding Catholicism,

prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

and

nativism. The Know Nothing Party embodied the social forces at work, but its weak leadership was unable to solidify its organization, and the Republicans picked it apart. Nativism was so powerful that the Republicans could not avoid it, but they did minimize it and turn voter wrath against the threat that slave owners would buy up the good farm lands wherever slavery was allowed. The realignment was powerful because it forced voters to switch parties, as typified by the rise and fall of the Know Nothings, the rise of the Republican Party and the splits in the Democratic Party.

At the

1856 Republican National Convention

The 1856 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention that met from June 17 to June 19 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was the first national nominating convention of the Republican Party, which had been founded two ...

, the party adopted a national platform emphasizing opposition to the expansion of slavery into the territories. While Republican nominee

John C. Frémont lost the

1856 United States presidential election to Democrat

James Buchanan, Buchanan only managed to win four of the fourteen northern states, winning his home state of

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

narrowly.

Republicans fared better in Congressional and local elections, but

Know Nothing candidates took a significant number of seats, creating an awkward three party arrangement. Despite the loss of the presidency and the lack of a majority in Congress, Republicans were able to orchestrate a Republican Speaker of the House, which went to

Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

. Historian

James M. McPherson

James Munro McPherson (born October 11, 1936) is an American Civil War historian, and is the George Henry Davis '86 Professor Emeritus of United States History at Princeton University. He received the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for '' Battle Cry of ...

writes regarding Banks' speakership that "if any one moment marked the birth of the Republican party, this was it."

The Republicans were eager for

the elections of 1860.

Former

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

Representative

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

spent several years building support within the party, campaigning heavily for Frémont in 1856 and making a bid for the

Senate in

1858

Events

January–March

* January –

** Benito Juárez (1806–1872) becomes Liberal President of Mexico. At the same time, conservatives install Félix María Zuloaga (1813–1898) as president.

** William I of Prussia becomes regen ...

, losing to Democrat

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

but gaining national attention for the

Lincoln–Douglas debates it produced.

At the

1860 Republican National Convention, Lincoln consolidated support among opponents of

New York Senator

William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

, a fierce abolitionist who some Republicans feared would be too radical for crucial states such as Pennsylvania and

Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, as well as those who disapproved of his support for Irish immigrants.

Lincoln won on the third ballot and was ultimately elected president in the

general election in a rematch against Douglas. Lincoln had not been on the ballot in a single southern state, and even if the vote for Democrats had not been split between Douglas,

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

and

John Bell, the Republicans would've still won but without the

popular vote

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the total ...

.

This election result helped kickstart the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

which lasted from 1861 until 1865.

The

election of 1864 united

War Democrats

War Democrats in American politics of the 1860s were members of the Democratic Party who supported the Union and rejected the policies of the Copperheads (or Peace Democrats). The War Democrats demanded a more aggressive policy toward the C ...

with the GOP and saw Lincoln and

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

Democratic Senator

Andrew Johnson get nominated on the

National Union Party ticket;

Lincoln was re-elected. By June 1865, slavery was dead in the ex-Confederate states, but still existed in some border states. Under Republican congressional leadership, the

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, by the House of Representative ...

—which banned slavery in the United States—passed in 1865; it was ratified in December 1865.

Reconstruction, the gold standard and the Gilded Age

Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Recons ...

during Lincoln's presidency felt he was too moderate in his eradication of slavery and opposed his

ten percent plan

The ten percent plan, formally the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction (), was a United States presidential proclamation issued on December 8, 1863, by United States President Abraham Lincoln, during the American Civil War. By this point i ...

. Radical Republicans passed the

Wade–Davis Bill

The Wade–Davis Bill of 1864 () was a bill "to guarantee to certain States whose governments have been usurped or overthrown a republican form of government," proposed for the Reconstruction of the South. In opposition to President Abraham Linco ...

in 1864, which sought to enforce the taking of the

Ironclad Oath for all former

Confederates. Lincoln vetoed the bill, believing it would jeopardize the peaceful reintegration of the Confederate states into the United States.

Following the

assassination of Lincoln

On April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president of the United States, was assassinated by well-known stage actor John Wilkes Booth, while attending the play ''Our American Cousin'' at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C.

Shot in the hea ...

, Johnson ascended to the presidency and was deplored by Radical Republicans. Johnson was vitriolic in his criticisms of the Radical Republicans during a national tour ahead of the

1866 midterm elections.

In his view, Johnson saw Radical Republicanism as the same as

secessionism

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics lea ...

, both being two extremist sides of the political spectrum.

Anti-Johnson Republicans won a two-thirds majority in both chambers of Congress following the elections, which helped lead the way toward his

impeachment and near ouster from office in 1868.

That

same year, former

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

General

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

was elected as the next Republican president.

Grant was a Radical Republican which created some division within the party, some such as

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

Senator

Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

and Illinois Senator

Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull esta ...

opposed most of his

Reconstructionist policies. Others found contempt with the

large-scale corruption present in

Grant's administration, with the emerging

Stalwart faction defending Grant and the

spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

, whereas the

Half-Breeds pushed for reform of the

civil service. Republicans who opposed Grant branched off to form the

Liberal Republican Party, nominating

Horace Greeley in

1872

Events

January–March

* January 12 – Yohannes IV is crowned Emperor of Ethiopia in Axum, the first ruler crowned in that city in over 500 years.

* February 2 – The government of the United Kingdom buys a number of forts on ...

. The Democratic Party attempted to capitalize on this divide in the GOP by co-nominating Greeley under their party banner. Greeley's positions proved inconsistent with the Liberal Republican Party that nominated him, with Greeley supporting high

tariffs

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and po ...

despite the party's opposition. Grant was easily re-elected.

The

1876 general election saw a contentious conclusion as both parties claimed victory despite three southern states still not officially declaring a winner at the end of election day.

Voter suppression

Voter suppression is a strategy used to influence the outcome of an election by discouraging or preventing specific groups of people from voting. It is distinguished from political campaigning in that campaigning attempts to change likely voting ...

had occurred in the south to depress the black and white Republican vote, which gave Republican-controlled

returning officer

In various parliamentary systems, a returning officer is responsible for overseeing elections in one or more constituencies.

Australia

In Australia a returning officer is an employee of the Australian Electoral Commission or a state electoral ...

s enough of a reason to declare that fraud, intimidation and violence had soiled the states' results. They proceeded to throw out enough Democratic votes for Republican

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governo ...

to be declared the winner. Still, Democrats refused to accept the results and an

Electoral Commission

An election commission is a body charged with overseeing the implementation of electioneering process of any country. The formal names of election commissions vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and may be styled an electoral commission, a c ...

made up of members of Congress was established to decide who would be awarded the states' electors. After the Commission voted along party lines in Hayes' favor, Democrats threatened to delay the counting of electoral votes indefinitely so no president would be inaugurated on March 4. This resulted in the

Compromise of 1877 and Hayes finally became president.

Hayes doubled down on the

gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the l ...

, which had been signed into law by Grant with the

Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873, was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of go ...

, as a solution to the depressed American economy in the aftermath of the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

. He also believed

greenbacks posed a threat; greenbacks being money printed during the Civil War that was not backed by

specie

Specie may refer to:

* Coins or other metal money in mass circulation

* Bullion coins

* Hard money (policy)

* Commodity money

Commodity money is money whose value comes from a commodity of which it is made. Commodity money consists of objects ...

, which Hayes objected to as a proponent of

hard money. Hayes sought to restock the country's gold supply, which by January 1879 succeeded as gold was more frequently exchanged for greenbacks compared to greenbacks being exchanged for gold. Ahead of the

1880 general election, Republican

James G. Blaine ran for the party nomination supporting Hayes' gold standard push and supporting his civil reforms. Both falling short of the nomination, Blaine and opponent

John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

backed Republican

James A. Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

, who agreed with Hayes' move in favor of the gold standard, but opposed his civil reform efforts.

Garfield was elected but

assassinated early into his term, however his death helped create support for the

Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the federal govern ...

, which was passed in 1883; the bill was signed into law by Republican President

Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James ...

, who succeeded Garfield.

Blaine once again ran for the presidency, winning the nomination but losing to Democrat

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

in

1884

Events

January–March

* January 4 – The Fabian Society is founded in London.

* January 5 – Gilbert and Sullivan's '' Princess Ida'' premières at the Savoy Theatre, London.

* January 18 – Dr. William Price at ...

, the first Democrat to be elected president since Buchanan. Dissident Republicans, known as

Mugwumps

The Mugwumps were Republican political activists in the United States who were intensely opposed to political corruption. They were never formally organized. Typically they switched parties from the Republican Party by supporting Democratic ...

, had defected Blaine due to corruption which had plagued his political career. Cleveland stuck to the gold standard policy, which eased most Republicans, but he came into conflict with the party regarding budding

American imperialism

American imperialism refers to the expansion of American political, economic, cultural, and media influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright military conques ...

. Republican

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

was able to reclaim the presidency from Cleveland in

1888

In Germany, 1888 is known as the Year of the Three Emperors. Currently, it is the year that, when written in Roman numerals, has the most digits (13). The next year that also has 13 digits is the year 2388. The record will be surpassed as late ...

. During his presidency, Harrison signed the

Dependent and Disability Pension Act

The Dependent and Disability Pension Act was passed by the United States Congress (26 Stat. 182) and signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison on June 27, 1890. The act provided pensions for all veterans who had served at least ninety days in ...

, which established pensions for all veterans of the Union who had served for more than 90 days and were unable to perform manual labor.

A majority of Republicans supported the

annexation of Hawaii, under the

new governance of Republican

Sanford B. Dole

Sanford Ballard Dole (April 23, 1844 – June 9, 1926) was a lawyer and jurist from the Hawaiian Islands. He lived through the periods when Hawaii was a kingdom, protectorate, republic, and territory. A descendant of the American missionary ...

, and Harrison, following his loss in

1892

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins accommodating immigrants to the United States.

* February 1 - The historic Enterprise Bar and Grill was established in Rico, Colorado.

* February 27 – Rudolf Diesel applies fo ...

to Cleveland, attempted to pass a treaty annexing

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

before Cleveland was to be inaugurated again. Cleveland

opposed annexation, though Democrats were split geographically on the issue, with most northeastern Democrats proving to be the strongest voices of opposition.

In

1896

Events

January–March

* January 2 – The Jameson Raid comes to an end, as Jameson surrenders to the Boers.

* January 4 – Utah is admitted as the 45th U.S. state.

* January 5 – An Austrian newspaper reports that ...

, Republican

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

's platform supported the gold standard and high tariffs, having been the creator and namesake for the

McKinley Tariff

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress, framed by then Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost fift ...

of 1890. Though having been divided on the issue prior to the

1896 Republican National Convention

The 1896 Republican National Convention was held in a temporary structure south of the St. Louis City Hall in Saint Louis, Missouri, from June 16 to June 18, 1896.

Former Governor William McKinley of Ohio was nominated for president on the firs ...

, McKinley decided to heavily favor the gold standard over

free silver in his campaign messaging, but promised to continue

bimetallism to ward off continued skepticism over the gold standard, which had lingered since the

Panic of 1893. Democrat

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

proved to be a devoted adherent to the free silver movement, which cost Bryan the support of Democrat institutions such as

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

, the ''

New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

'' and a large majority of the Democratic Party's upper and middle-class support. McKinley defeated Bryan and returned the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

to Republican control until

1912.

20th century

Progressives vs Standpatters

The 1896 realignment cemented the Republicans as the party of big businesses while

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

added more small business support by his embrace of

trust busting

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

. He handpicked his successor

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

in

1908

Events

January

* January 1 – The British ''Nimrod'' Expedition led by Ernest Shackleton sets sail from New Zealand on the ''Nimrod'' for Antarctica.

* January 3 – A total solar eclipse is visible in the Pacific Ocean, and is the 4 ...

, but they became enemies as the party split down the middle. Taft defeated Roosevelt for the

1912 nomination so Roosevelt stormed out of the convention and started a new party. Roosevelt ran on the ticket of his new

Progressive ("Bull Moose") Party. He called for

social reforms, many of which were later championed by

New Deal Democrats in the 1930s. He lost and when most of his supporters returned to the GOP they found they did not agree with the new

conservative economic thinking, leading to an ideological shift to the right in the Republican Party.

The Republicans returned to the White House throughout the 1920s, running on platforms of normalcy, business-oriented efficiency and high tariffs. The national party platform avoided mention of

prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcohol ...

, instead issuing a vague commitment to law and order.

Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

,

Calvin Coolidge and

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

were resoundingly elected in

1920,

1924

Events

January

* January 12 – Gopinath Saha shoots Ernest Day, whom he has mistaken for Sir Charles Tegart, the police commissioner of Calcutta, and is arrested soon after.

* January 20– 30 – Kuomintang in China holds ...

and

1928

Events January

* January – British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith reports the results of Griffith's experiment, indirectly proving the existence of DNA.

* January 1 – Eastern Bloc emigration and defection: Boris Bazhan ...

, respectively. The

Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a bribery scandal involving the administration of United States President Warren G. Harding from 1921 to 1923. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyomi ...

threatened to hurt the party, but Harding died and the opposition splintered in 1924. The pro-business policies of the decade seemed to produce an unprecedented prosperity until the

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

heralded the

Great Depression.

New Deal era

The

New Deal coalition forged by Democrat

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

controlled American politics for most of the next three decades, excluding the two-term presidency of Republican

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

. After Roosevelt took office in 1933, New Deal legislation sailed through Congress and the economy moved sharply upward from its nadir in early 1933. However, long-term unemployment remained a drag until 1940. In the 1934 midterm elections, 10 Republican senators went down to defeat, leaving the GOP with only 25 senators against 71 Democrats. The House of Representatives likewise had overwhelming Democratic majorities.

The Republican Party factionalized into a majority "Old Right" (based in the midwest) and a liberal wing based in the northeast that supported much of the New Deal. The Old Right sharply attacked the "Second New Deal" and said it represented

class warfare

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms ...

and

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

. Roosevelt was re-elected in a landslide in 1936; however, as his second term began, the economy declined, strikes soared, and he failed to take control of the Supreme Court and purge the southern conservatives from the Democratic Party. Republicans made a major comeback in the

1938 elections

The following elections occurred in the year 1938.

Africa

* 1938 South African general election

Asia

* 1938 Philippine general election

* 1938 Philippine legislative election

* 1938 Soviet Union regional elections

Europe

* 1938 Estonian parl ...

and had new rising stars such as

Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate Majority Leade ...

of

Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

on the right and

Thomas E. Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

of

New York on the left. Southern conservatives joined with most Republicans to form the

conservative coalition, which dominated domestic issues in Congress until 1964. Both parties split on foreign policy issues, with the anti-war isolationists dominant in the Republican Party and the interventionists who wanted to stop

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

dominant in the Democratic Party. Roosevelt won a third and fourth term in 1940 and 1944, respectively. Conservatives abolished most of the New Deal during the war, but they did not attempt to do away with Social Security or the agencies that regulated business.

Historian

George H. Nash

George H. Nash (born April 1, 1945) is an American historian and interpreter of American conservatism. He is a biographer of Herbert Hoover. He is best known for ''The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945'', which first appeare ...

argues:

Unlike the "moderate", internationalist, largely eastern bloc of Republicans who accepted (or at least acquiesced in) some of the "Roosevelt Revolution" and the essential premises of President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

's foreign policy, the Republican Right at heart was counterrevolutionary. Anti-collectivist, anti-Communist, anti-New Deal, passionately committed to limited government, free market economics, and congressional (as opposed to executive) prerogatives, the G.O.P. conservatives were obliged from the start to wage a constant two-front war: against liberal Democrats from without and "me-too" Republicans from within.

After 1945, the internationalist wing of the GOP cooperated with Truman's

Cold War foreign policy, funded the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

and supported NATO, despite the continued isolationism of the Old Right.

Second half of the Twentieth Century

The second half of the 20th century saw the election or succession of Republican presidents

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

,

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

,

Gerald Ford,

Ronald Reagan and

George H. W. Bush. Eisenhower had defeated conservative leader Senator Robert A. Taft for the 1952 nomination, but conservatives dominated the domestic policies of the Eisenhower administration. Voters liked Eisenhower much more than they liked the GOP and he proved unable to shift the party to a more moderate position. Since 1976, liberalism has virtually faded out of the Republican Party, apart from a few northeastern holdouts.

[Nicol C. Rae, ''The Decline and Fall of the Liberal Republicans: From 1952 to the Present'' (1989)] Historians cite the

1964 United States presidential election

The 1964 United States presidential election was the 45th quadrennial presidential election. It was held on Tuesday, November 3, 1964. Incumbent Democratic United States President Lyndon B. Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater, the Republican nomi ...

and its respective

1964 Republican National Convention

The 1964 Republican National Convention took place in the Cow Palace, Daly City, California, from July 13 to July 16, 1964. Before 1964, there had been only one national Republican convention on the West Coast, the 1956 Republican National Convent ...

as a significant shift, which saw the conservative wing, helmed by Senator

Barry Goldwater of

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

, battle the liberal New York Governor

Nelson Rockefeller and his eponymous

Rockefeller Republican

The Rockefeller Republicans were members of the Republican Party (GOP) in the 1930s–1970s who held moderate-to- liberal views on domestic issues, similar to those of Nelson Rockefeller, Governor of New York (1959–1973) and Vice President of ...

faction for the party presidential nomination. With Goldwater poised to win, Rockefeller, urged to mobilize his liberal faction, relented, "You’re looking at it, buddy. I’m all that’s left." Though Goldwater lost in a landslide, Reagan would make himself known as a prominent supporter of his throughout the campaign, delivering the "

A Time for Choosing

"A Time for Choosing", also known as "The Speech", was a speech presented during the 1964 U.S. presidential election campaign by future president Ronald Reagan on behalf of Republican candidate Barry Goldwater. 'A Time For Choosing' launched R ...

" speech for him. He'd go on to become

governor of California two years later, and in

1980, win the presidency.

The

presidency of Reagan

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following a landslide victory over ...

, lasting from 1981 to 1989, constituted what is known as the "

Reagan Revolution

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following a landslide victory over ...

". It was seen as a fundamental shift from the

stagflation

In economics, stagflation or recession-inflation is a situation in which the inflation rate is high or increasing, the economic growth rate slows, and unemployment remains steadily high. It presents a dilemma for economic policy, since actio ...

of the 1970s preceding it, with the introduction of

Reaganomics

Reaganomics (; a portmanteau of ''Reagan'' and ''economics'' attributed to Paul Harvey), or Reaganism, refers to the neoliberal economic policies promoted by U.S. President Ronald Reagan during the 1980s. These policies are commonly associat ...

intended to cut taxes, prioritize government

deregulation and shift funding from the domestic sphere into the military to check the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

by utilizing

deterrence theory

Deterrence theory refers to the scholarship and practice of how threats or limited force by one party can convince another party to refrain from initiating some other course of action. The topic gained increased prominence as a military strategy ...

. During a visit to then-

West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

in June 1987, he addressed Soviet leader

Mikhail Gorbachev during a speech at the

Berlin Wall, demanding that he "tear down this wall". The remark was ignored at the time but after the

fall of the wall in 1989 retroactively recast as a soaring achievement over the years.

After he left office in 1989, Reagan became an iconic conservative Republican. Republican presidential candidates would frequently claim to share his views and aim to establish themselves and their policies as the more appropriate heir to his legacy.

Vice President Bush scored a landslide in the

1988 general election. However his term would see a divide form within the Republican Party. Bush's vision of

economic liberalization

Economic liberalization (or economic liberalisation) is the lessening of government regulations and restrictions in an economy in exchange for greater participation by private entities. In politics, the doctrine is associated with classical liber ...

and international cooperation with foreign nations saw the negotiation and signing of the

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the conceptual beginnings of the

World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization that regulates and facilitates international trade. With effective cooperation

in the United Nations System, governments use the organization to establish, revise, and ...

.

Independent politician

An independent or non-partisan politician is a politician not affiliated with any political party or bureaucratic association. There are numerous reasons why someone may stand for office as an independent.

Some politicians have political views th ...

and businessman

Ross Perot decried NAFTA and prophesied it would lead to

outsourcing American jobs to

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, while Democrat

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

found agreement in Bush's policies. Bush lost reelection in

1992 with 37 percent of the

popular vote

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the total ...

, with Clinton garnering a plurality of 43 percent and Perot in third with 19 percent. While debatable if Perot's candidacy cost Bush reelection,

Charlie Cook of ''

The Cook Political Report

''The Cook Political Report with Amy Walter'' is an American online newsletter that analyzes elections and campaigns for the U.S. Presidency, the United States Senate, the United States House of Representatives, and U.S. governors' offices. Sel ...

'' attests Perot's messaging held more weight with Republican and conservative voters at-large. Perot formed the

Reform Party and those who had been or would become prominent Republicans saw brief membership, such as former

White House Communications Director

The White House communications director or White House director of communications, also known officially as Assistant to the President for Communications, is part of the senior staff of the president of the United States. The officeholder is resp ...

Pat Buchanan and later President

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of P ...

.

Gingrich Revolution

In the

Republican Revolution of

1994

File:1994 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The 1994 Winter Olympics are held in Lillehammer, Norway; The Kaiser Permanente building after the 1994 Northridge earthquake; A model of the MS Estonia, which sank in the Baltic Sea; Nelson ...

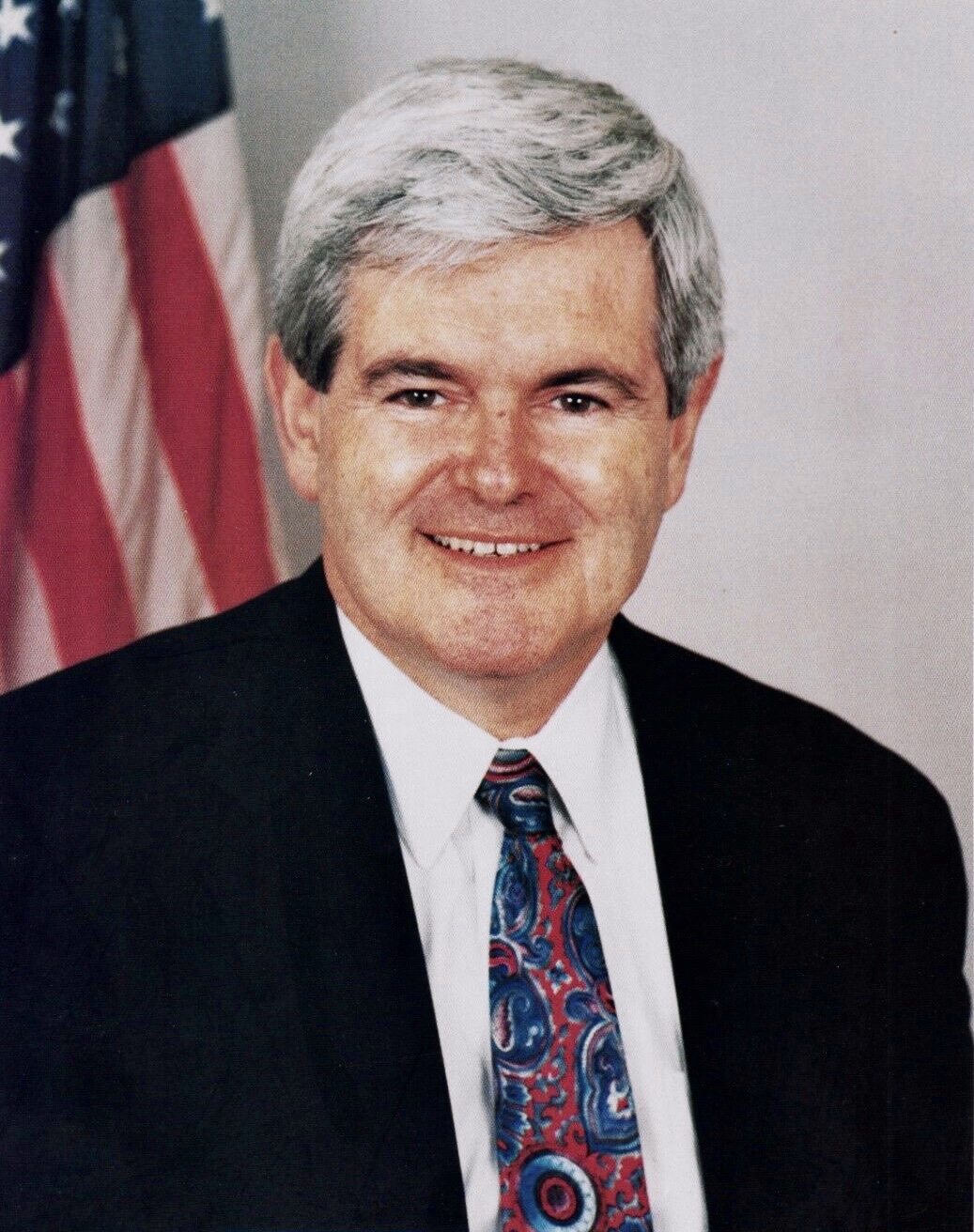

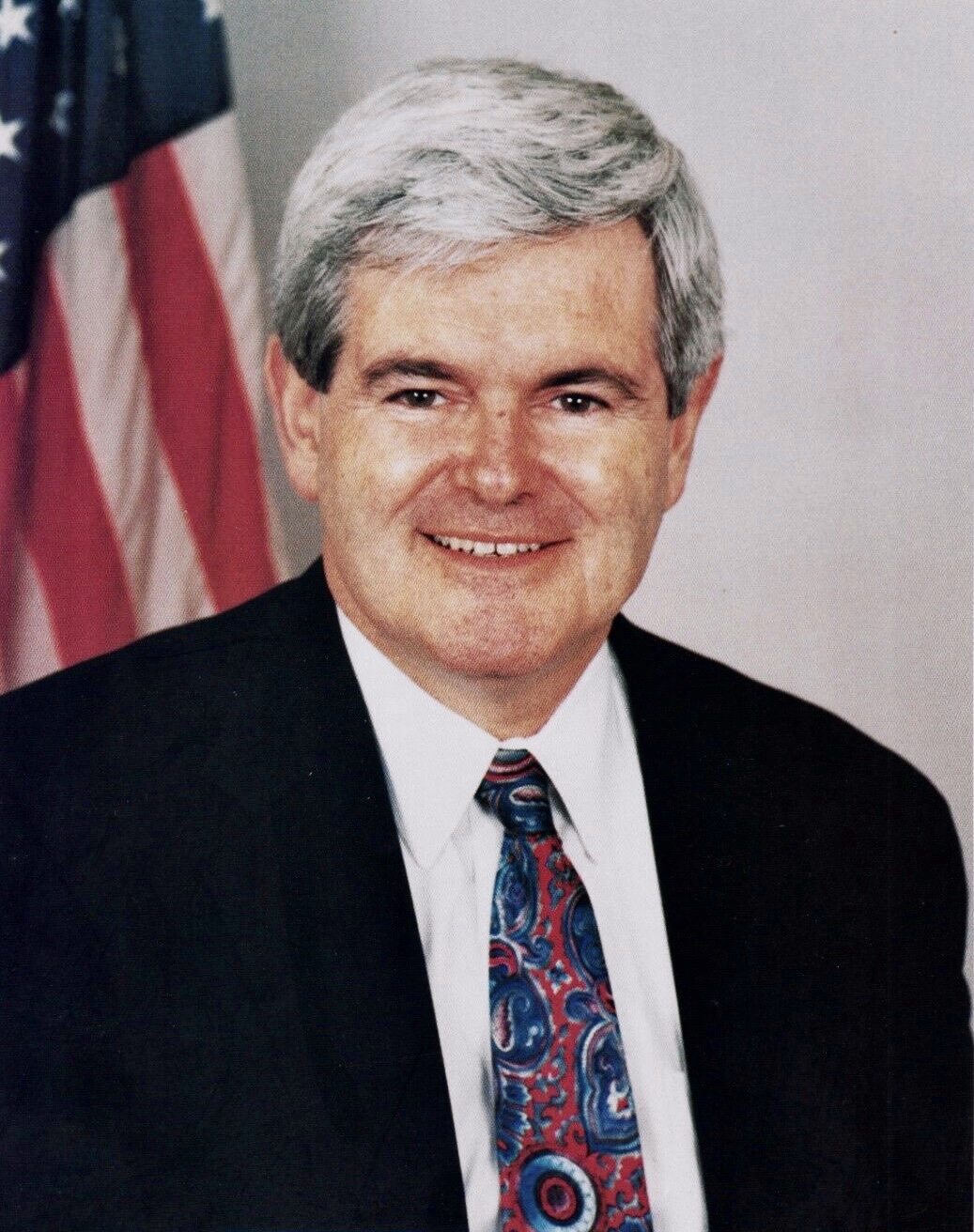

, the party—led by House Minority Whip

Newt Gingrich, who campaigned on the "

Contract with America

The Contract with America was a legislative agenda advocated for by the Republican Party during the 1994 congressional election campaign. Written by Newt Gingrich and Dick Armey, and in part using text from former President Ronald Reagan's 19 ...

"—won majorities in both chambers of Congress, gained 12 governorships and regained control of 20 state legislatures. (However, most voters had not heard of the Contract and the Republican victory was attributed to

redistricting, traditional mid-term anti-incumbent voting, and Republicans becoming the majority party in Dixie for the first time since Reconstruction.)

[ It was the first time the Republican Party had achieved a majority in the House since ]1952

Events January–February

* January 26 – Black Saturday in Egypt: Rioters burn Cairo's central business district, targeting British and upper-class Egyptian businesses.

* February 6

** Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, becomes m ...

.Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hungerf ...

, and within the first 100 days of the Republican majority every proposition featured in the Contract with America was passed, with the exception of term limits for members of Congress. (Unfortunately they did not pass in the Senate.)1928

Events January

* January – British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith reports the results of Griffith's experiment, indirectly proving the existence of DNA.

* January 1 – Eastern Bloc emigration and defection: Boris Bazhan ...

despite the presidential ticket of Bob Dole- Jack Kemp losing handily to President Clinton in the general election. However, Gingrich's national profile proved a detriment to the Republican Congress, which enjoyed majority approval among voters in spite of Gingrich's relative unpopularity.impeachment of Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton, the 42nd president of the United States, was impeached by the United States House of Representatives of the 105th United States Congress on December 19, 1998, for "high crimes and misdemeanors". The House adopted two articles ...

in 1998, Gingrich decided to make Clinton's misconduct the party message heading into the midterms, believing it would add to their majority. The strategy proved mistaken and the Republicans lost five seats, though whether it was due to poor messaging or Clinton's popularity providing a coattail effect

The coattail effect or down-ballot effect is the tendency for a popular political party leader to attract votes for other candidates of the same party in an election. For example, in the United States, the party of a victorious presidential cand ...

is debated. Gingrich was ousted from party power due to the performance, ultimately deciding to resign from Congress altogether. For a short time afterward it appeared Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

Representative Bob Livingston

Robert Linlithgow Livingston Jr. (born April 30, 1943) is an American lobbyist and politician who served as a U.S. Representative from Louisiana from 1977 to 1999. A Republican, he was chosen as Newt Gingrich's successor as Speaker of the U.S. ...

would become his successor. Livingston, however, stepped down from consideration and resigned from Congress after damaging reports of affairs threatened the Republican House's legislative agenda if he were to serve as Speaker. Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

Representative Dennis Hastert was promoted to Speaker in Livingston's place, and served in that position until 2007.

21st century

A Republican ticket of George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Republican Party, Bush family, and son of the 41st president George H. W. Bush, he ...

and Dick Cheney won the 2000

File:2000 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Protests against Bush v. Gore after the 2000 United States presidential election; Heads of state meet for the Millennium Summit; The International Space Station in its infant form as seen from S ...

and 2004 presidential elections. Bush campaigned as a " compassionate conservative" in 2000, wanting to better appeal to immigrants and minority voters. The goal was to prioritize drug rehabilitation programs and aide for prisoner reentry into society, a move intended to capitalize on President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

's tougher crime initiatives such as the 1994 crime bill passed under his administration. The platform failed to gain much traction among members of the party during his presidency.

With the inauguration of Bush as president, the Republican Party remained fairly cohesive for much of the 2000s as both strong economic libertarians and social conservatives opposed the Democrats, whom they saw as the party of bloated, secular, and liberal government.[Wooldridge, Adrian and John Micklethwait. ''The Right Nation'' (2004).] This period saw the rise of "pro-government conservatives"—a core part of the Bush's base—a considerable group of the Republicans who advocated for increased government spending and greater regulations covering both the economy and people's personal lives as well as for an activist, interventionist foreign policy. Survey groups such as the Pew Research Center found that social conservatives and free market advocates remained the other two main groups within the party's coalition of support, with all three being roughly equal in number. However, libertarians

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's enc ...

and libertarian-leaning conservatives increasingly found fault with what they saw as Republicans' restricting of vital civil liberties while corporate welfare

Corporate welfare is a phrase used to describe a government's bestowal of money grants, tax breaks, or other special favorable treatment for corporations.

The definition of corporate welfare is sometimes restricted to direct government subsidie ...

and the national debt hiked considerably under Bush's tenure. In contrast, some social conservatives expressed dissatisfaction with the party's support for economic policies that conflicted with their moral values.["How Huckabee Scares the GOP"](_blank)

. By E. J. Dionne

Eugene Joseph Dionne Jr. (; born April 23, 1952) is an American journalist, political commentator, and long-time op-ed columnist for ''The Washington Post''. He is also a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution, a profes ...

. Real Clear Politics

RealClearPolitics (RCP) is an American political news website and polling data aggregator formed in 2000 by former options trader John McIntyre and former advertising agency account executive Tom Bevan. The site features selected political new ...

. Published December 21, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

The Republican Party lost its Senate majority in 2001 when the Senate became split evenly; nevertheless, the Republicans maintained control of the Senate due to the tie-breaking vote of Vice President Cheney. Democrats gained control of the Senate on June 6, 2001, when Republican Senator Jim Jeffords of Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

switched his party affiliation to Democrat. The Republicans regained the Senate majority in the 2002 elections. Republican majorities in the House and Senate were held until the Democrats regained control of both chambers in the mid-term elections of 2006.

In 2008

File:2008 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Lehman Brothers went bankrupt following the Subprime mortgage crisis; Cyclone Nargis killed more than 138,000 in Myanmar; A scene from the opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing; ...

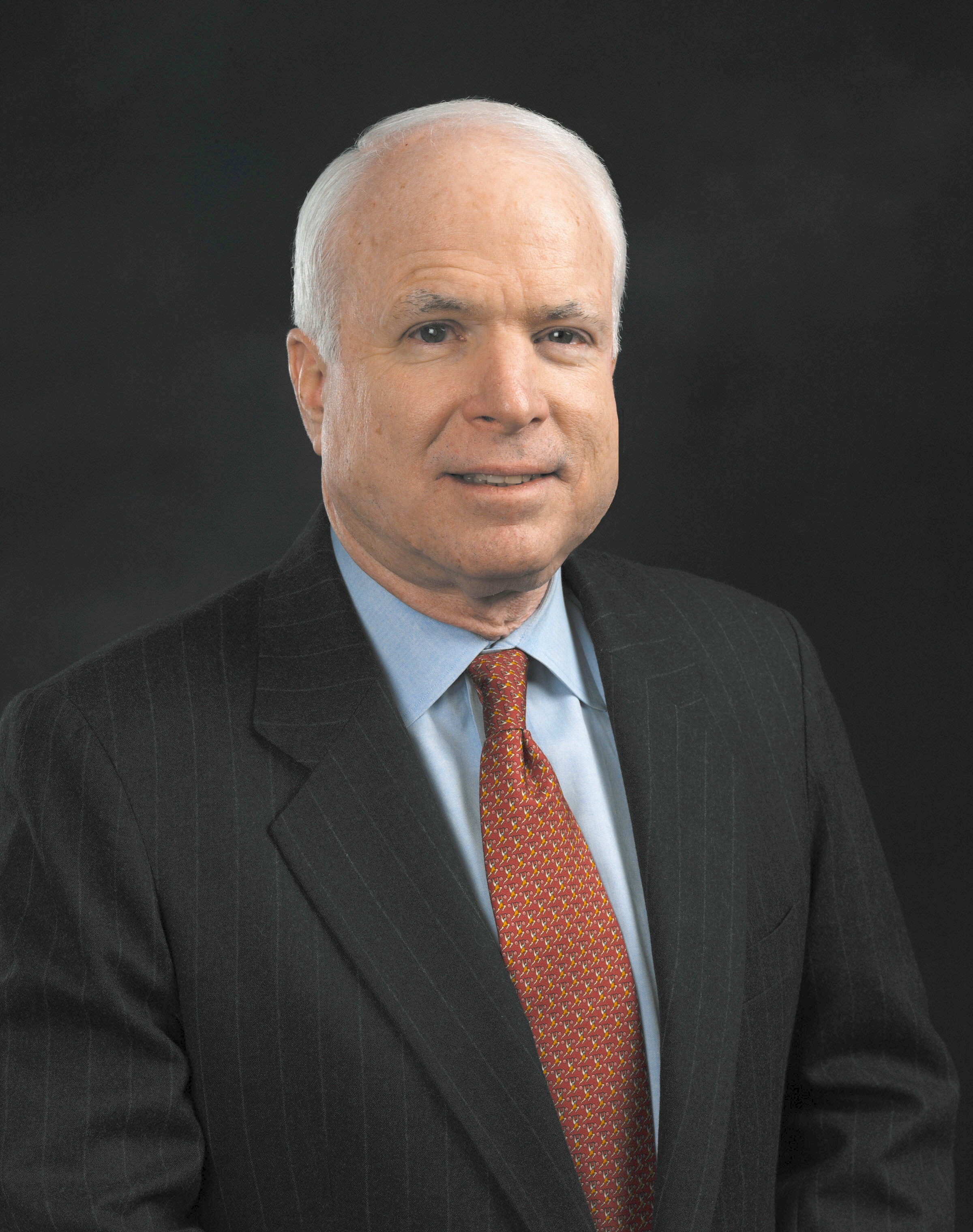

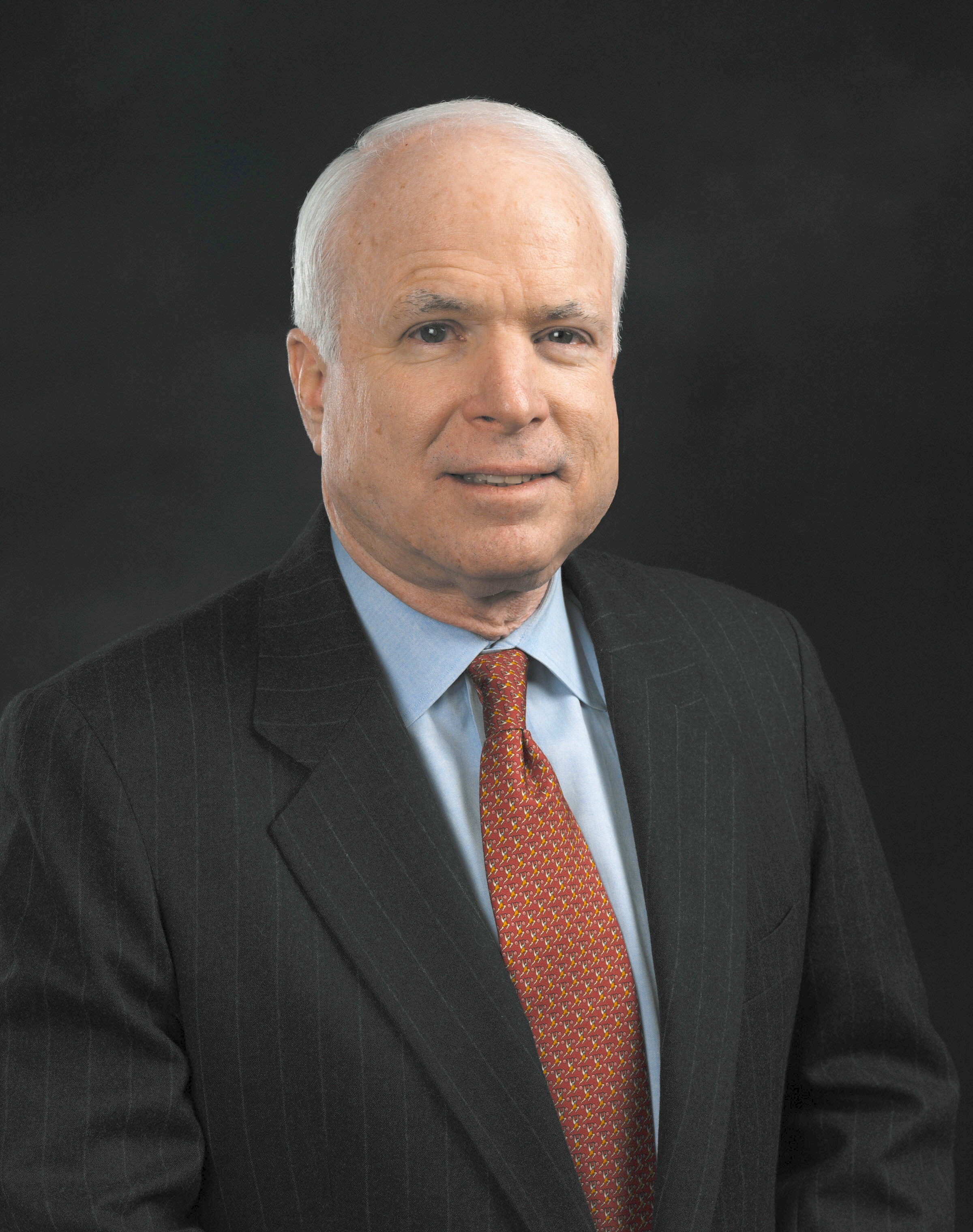

, Republican Senator John McCain of Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

and Governor Sarah Palin of Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

were defeated by Democratic Senators Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

and Joe Biden of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rockf ...

and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

, respectively.

The Republicans experienced electoral success in the wave election of 2010, which coincided with the ascendancy of the Tea Party movement

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2009. Members of the movement called for lower taxes and for a reduction of the national debt and federal budget defi ...

, an anti-Obama protest movement of fiscal conservatives

Fiscal conservatism is a political and economic philosophy regarding fiscal policy and fiscal responsibility with an ideological basis in capitalism, individualism, limited government, and ''laissez-faire'' economics.M. O. Dickerson et al., '' ...

.taxes

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regional, local, o ...

, and for a reduction of the national debt of the United States

The national debt of the United States is the total national debt owed by the federal government of the United States to Treasury security holders. The national debt at any point in time is the face value of the then-outstanding Treasury ...

and federal budget deficit through decreased government spending.[Gallup: Tea Party's top concerns are debt, size of government](_blank)

''The Hill'', July 5, 2010[Somashekhar, Sandhya (September 12, 2010)]

''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...