Renaissance architecture is the European architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 16th centuries in different regions, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

and

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

thought and material culture. Stylistically, Renaissance architecture followed

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High Middle Ages, High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It evolved f ...

and was succeeded by

Baroque architecture

Baroque architecture is a highly decorative and theatrical style which appeared in Italy in the late 16th century and gradually spread across Europe. It was originally introduced by the Catholic Church, particularly by the Jesuits, as a means to ...

and

neoclassical architecture

Neoclassical architecture, sometimes referred to as Classical Revival architecture, is an architectural style produced by the Neoclassicism, Neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century in Italy, France and Germany. It became one of t ...

.

Developed first in

Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, with

Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi (1377 – 15 April 1446), commonly known as Filippo Brunelleschi ( ; ) and also nicknamed Pippo by Leon Battista Alberti, was an Italian architect, designer, goldsmith and sculptor. He is considered to ...

as one of its innovators, the Renaissance style quickly spread to other Italian cities. The style was carried to other parts of Europe at different dates and with varying degrees of impact. It began in Florence in the early 15th century and reflected a revival of classical Greek and Roman principles such as symmetry, proportion, and geometry. This movement was supported by wealthy patrons, including the Medici family and the Catholic Church, who commissioned works to display both religious devotion and political power. Architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi, Leon Battista Alberti, and later Andrea Palladio revolutionized urban landscapes with domes, columns, and harmonious facades. While Renaissance architecture flourished most in Italy, its influence spread across Europe reaching France, Spain, and the Low Countries adapting to local traditions. Public buildings, churches, and palaces became symbols of civic pride and imperial strength, linking humanism with empire-building.

Renaissance style places emphasis on

symmetry

Symmetry () in everyday life refers to a sense of harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance. In mathematics, the term has a more precise definition and is usually used to refer to an object that is Invariant (mathematics), invariant und ...

,

proportion,

geometry

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

and the regularity of parts, as demonstrated in the architecture of

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

and in particular ancient

Roman architecture

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical ancient Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often con ...

, of which many examples remained. Orderly arrangements of

column

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression member ...

s,

pilaster

In architecture, a pilaster is both a load-bearing section of thickened wall or column integrated into a wall, and a purely decorative element in classical architecture which gives the appearance of a supporting column and articulates an ext ...

s and

lintel

A lintel or lintol is a type of beam (a horizontal structural element) that spans openings such as portals, doors, windows and fireplaces. It can be a decorative architectural element, or a combined ornamented/structural item. In the case ...

s, as well as the use of semicircular arches, hemispherical

dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

s,

niches and

aedicula

In religion in ancient Rome, ancient Roman religion, an ''aedicula'' (: ''aediculae'') is a small shrine, and in classical architecture refers to a Niche (architecture), niche covered by a pediment or entablature supported by a pair of columns an ...

e replaced the more complex proportional systems and irregular profiles of

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

buildings.

Historiography

The word "Renaissance" derives from the term ''rinascita'', which means rebirth, first appeared in

Giorgio Vasari

Giorgio Vasari (30 July 1511 – 27 June 1574) was an Italian Renaissance painter, architect, art historian, and biographer who is best known for his work ''Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects'', considered the ideol ...

's ''

'', 1550.

Although the term Renaissance was used first by the French historian

Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and writer. He is best known for his multivolume work ''Histoire de France'' (History of France). Michelet was influenced by Giambattista Vico; he admired Vico's emphas ...

, it was given its more lasting definition from the Swiss historian

Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (; ; 25 May 1818 – 8 August 1897) was a Swiss historian of art and culture and an influential figure in the historiography of both fields. His best known work is '' The Civilization of the Renaissance in ...

, whose book ''

The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy

''The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy'' () is an 1860 work on the Italian Renaissance by Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt. Together with his ''History of the Renaissance in Italy'' (''Die Geschichte der Renaissance in Italien''; 1867) it ...

'', 1860, was influential in the development of the modern interpretation of the

Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( ) was a period in History of Italy, Italian history between the 14th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Western Europe and marked t ...

. The folio of measured drawings ''Édifices de Rome moderne; ou, Recueil des palais, maisons, églises, couvents et autres monuments'' (The Buildings of Modern Rome), first published in 1840 by Paul Letarouilly, also played an important part in the revival of interest in this period.

Erwin Panofsky

Erwin Panofsky (March 30, 1892 – March 14, 1968) was a German-Jewish art historian whose work represents a high point in the modern academic study of iconography, including his hugely influential ''Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art ...

, ''Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art'', (New York: Harper and Row, 1960) The Renaissance style was recognized by contemporaries in the term ''"all'antica"'', or "in the ancient manner" (of the Romans).

Principal phases

Historians often divide the Renaissance in Italy into three phases. Whereas art historians might talk of an ''Early Renaissance'' period, in which they include developments in 14th-century painting and sculpture, this is usually not the case in architectural history. The bleak economic conditions of the late 14th century did not produce buildings that are considered to be part of the Renaissance. As a result, the word ''Renaissance'' among architectural historians usually applies to the period 1400 to , or later in the case of non-Italian Renaissances.

Historians often use the following designations:

*

Quattrocento

The cultural and artistic events of Italy during the period 1400 to 1499 are collectively referred to as the Quattrocento (, , ) from the Italian word for the number 400, in turn from , which is Italian for the year 1400. The Quattrocento encom ...

()

During the ''Quattrocento,'' sometimes known as the Early Renaissance, concepts of architectural order were explored and rules were formulated. The study of classical antiquity led in particular to the adoption of Classical detail and ornamentation. Space, as an element of architecture, was used differently than it was in the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. Space was organised by proportional logic, its form and rhythm subject to geometry, rather than being created by intuition as in Medieval buildings. The prime example of this is the

Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence

The Basilica di San Lorenzo (Basilica of St. Lawrence) is one of the largest churches of Florence, Italy, situated at the centre of the main market district of the city, and it is the burial place of all the principal members of the Medici fam ...

by

Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi (1377 – 15 April 1446), commonly known as Filippo Brunelleschi ( ; ) and also nicknamed Pippo by Leon Battista Alberti, was an Italian architect, designer, goldsmith and sculptor. He is considered to ...

(1377–1446).

*

High Renaissance

In art history, the High Renaissance was a short period of the most exceptional artistic production in the Italian states, particularly Rome, capital of the Papal States, and in Florence, during the Italian Renaissance. Most art historians stat ...

()

During the High Renaissance, concepts derived from classical antiquity were developed and used with greater confidence. The most representative architect is

Donato Bramante

Donato Bramante (1444 – 11 April 1514), born as Donato di Pascuccio d'Antonio and also known as Bramante Lazzari, was an Italian architect and painter. He introduced Renaissance architecture to Milan and the High Renaissance style to Rom ...

(1444–1514), who expanded the applicability of classical architecture to contemporary buildings. His Tempietto di

San Pietro in Montorio

San Pietro in Montorio (English: "Saint Peter on the Golden Mountain") is a church in Rome, Italy, which includes in its courtyard the ''Tempietto'', a small commemorative ''martyrium'' ('martyry') built by Donato Bramante.

History

The Church o ...

(1503) was directly inspired by circular

Roman temple

Ancient Roman temples were among the most important buildings in culture of ancient Rome, Roman culture, and some of the richest buildings in Architecture of ancient Rome, Roman architecture, though only a few survive in any sort of complete ...

s. He was, however, hardly a slave to the classical forms and it was his style that was to dominate Italian architecture in the 16th century.

*

Mannerism

Mannerism is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Italy, when the Baroque style largely replaced it ...

()

During the

Mannerist

Mannerism is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Italy, when the Baroque style largely replaced it ...

period, architects experimented with using

architectural form In architecture, form refers to a combination of external appearance, internal structure, and the Unity (aesthetics), unity of the design as a whole, an order created by the architect using #Space and mass, space and mass.

External appearance

Th ...

s to emphasize solid and spatial relationships. The Renaissance ideal of harmony gave way to freer and more imaginative rhythms. The best known architect associated with the Mannerist style was

Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6March 147518February 1564), known mononymously as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspir ...

(1475–1564), who frequently used the

giant order

In classical architecture, a giant order, also known as colossal order, is an order whose columns or pilasters span two (or more) storeys. At the same time, smaller orders may feature in arcades or window and door framings within the storeys that ...

in his architecture, a large pilaster that stretches from the bottom to the top of a façade. He used this in his design for the

Piazza del Campidoglio

Piazza del Campidoglio ("Capitoline Square") is a public square (piazza) on the top of the ancient Capitoline Hill, between the Roman Forum and the Campus Martius in Rome, Italy. The square includes three main buildings, the Palazzo Senatorio (Se ...

in Rome. Prior to the 20th century, the term ''Mannerism'' had negative connotations, but it is now used to describe the historical period in more general non-judgemental terms.

* From Renaissance to Baroque

As the new style of architecture spread out from Italy, most other European countries developed a sort of Proto-Renaissance style, before the construction of fully formulated Renaissance buildings. Each country in turn then grafted its own architectural traditions to the new style, so that Renaissance buildings across Europe are diversified by region. Within Italy the evolution of Renaissance architecture into Mannerism, with widely diverging tendencies in the work of

Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6March 147518February 1564), known mononymously as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspir ...

,

Giulio Romano

Giulio Pippi ( – 1 November 1546), known as Giulio Romano and Jules Romain ( , ; ), was an Italian Renaissance painter and architect. He was a pupil of Raphael, and his stylistic deviations from High Renaissance classicism help define the ...

and

Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( , ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be on ...

, led to the Baroque style in which the same architectural vocabulary was used for very different rhetoric. Outside Italy, Baroque architecture was more widespread and fully developed than the Renaissance style, with significant buildings as far afield as Mexico and the

Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

.

History

Development in Italy

Italy of the 15th century, and the city of Florence in particular, was home to the Renaissance. It is in Florence that the new architectural style had its beginning, not slowly evolving in the way that

Gothic grew out of

Romanesque, but consciously brought to being by particular architects who sought to revive the order of a past "

Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during wh ...

". The scholarly approach to the architecture of the ancient coincided with the general revival of learning. A number of factors were influential in bringing this about.

Architectural

Italian architects had always preferred forms that were clearly defined and structural members that expressed their purpose.

Many Tuscan Romanesque buildings demonstrate these characteristics, as seen in the

Florence Baptistery

The Florence Baptistery, also known as the Baptistery of Saint John (), is a religious building in Florence, Italy. Dedicated to the patron saint of the city, John the Baptist, it has been a focus of religious, civic, and artistic life since its ...

and

Pisa Cathedral

Pisa Cathedral (), officially the Primatial Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of Mary (), is a medieval Catholic cathedral dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, in the Piazza dei Miracoli in Pisa, Italy, the oldest of the three s ...

.

Italy had never fully adopted the Gothic style of architecture. Apart from

Milan Cathedral

Milan Cathedral ( ; ), or Metropolitan Cathedral-Basilica of the Nativity of Saint Mary (), is the cathedral church of Milan, Lombardy, Italy. Dedicated to the Nativity of Mary, Nativity of St. Mary (), it is the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdi ...

, (influenced by French

Rayonnant

Rayonnant was a very refined style of Gothic Architecture which appeared in France in the 13th century. It was the defining style of the High Gothic period, and is often described as the high point of French Gothic architecture."Encylclopaedia B ...

Gothic), few Italian churches show the emphasis on vertical, the clustered shafts, ornate tracery and complex ribbed vaulting that characterise Gothic in other parts of Europe.

The presence, particularly in Rome, of ancient architectural remains showing the ordered

Classical style

Classical architecture typically refers to architecture consciously derived from the principles of Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity, or more specifically, from ''De architectura'' (c. 10 AD) by the Roman architect Vitruvius. Va ...

provided an inspiration to artists at a time when philosophy was also turning towards the Classical.

Political

In the 15th century,

Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

and

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

extended their power through much of the area that surrounded them, making the movement of artists possible. This enabled Florence to have significant artistic influence in

Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, and through Milan,

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

.

In 1377, the return of the Pope from the

Avignon Papacy

The Avignon Papacy (; ) was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon (at the time within the Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire, now part of France) rather than in Rome (now the capital of ...

and the re-establishment of the

Papal court

The papal household or pontifical household (usually not capitalized in the media and other nonofficial use, ), called until 1968 the Papal Court (''Aula Pontificia''), consists of dignitaries who assist the pope in carrying out particular ceremon ...

in Rome, brought wealth and importance to that city, as well as a renewal in the importance of the Pope in Italy, which was further strengthened by the

Council of Constance

The Council of Constance (; ) was an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church that was held from 1414 to 1418 in the Bishopric of Constance (Konstanz) in present-day Germany. This was the first time that an ecumenical council was convened in ...

in 1417. Successive Popes, especially

Julius II

Pope Julius II (; ; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death, in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope, the Battle Pope or the Fearsome ...

, 1503–13, sought to extend the Papacy's

temporal power throughout Italy.

[Andrew Martindale, ''Man and the Renaissance'', 1966, Paul Hamlyn, ISBN unknown]

Commercial

In the early Renaissance,

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

controlled sea trade over goods from the East. The large towns of

Northern Italy

Northern Italy (, , ) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. The Italian National Institute of Statistics defines the region as encompassing the four Northwest Italy, northwestern Regions of Italy, regions of Piedmo ...

were prosperous through trade with the rest of Europe,

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

providing a seaport for the goods of France and Spain;

Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

and

Turin

Turin ( , ; ; , then ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital from 1861 to 1865. The city is main ...

being centres of overland trade, and maintaining substantial metalworking industries. Trade brought wool from

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

to Florence, ideally located on the river for the production of fine cloth, the industry on which its wealth was founded. By dominating

Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

, Florence gained a seaport, and became the most powerful state in Tuscany. In this commercial climate, one family in particular turned their attention from trade to the lucrative business of money-lending. The

Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

became the chief bankers to the princes of Europe, becoming virtually princes themselves as they did so, by reason of both wealth and influence. Along the trade routes, and thus offered some protection by commercial interest, moved not only goods but also artists, scientists and philosophers.

Religious

The return of the

Pope Gregory XI

Pope Gregory XI (; born Pierre Roger de Beaufort; c. 1329 – 27 March 1378) was head of the Catholic Church from 30 December 1370 to his death, in March 1378. He was the seventh and last Avignon pope and the most recent French pope. In 1377, ...

from

Avignon

Avignon (, , ; or , ; ) is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the Communes of France, commune had a ...

in September 1377 and the resultant new emphasis on

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

as the center of

Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

spirituality, brought about a surge in the building of churches in Rome such as had not taken place for nearly a thousand years. This commenced in the mid 15th century and gained momentum in the 16th century, reaching its peak in the

Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

period. The construction of the

Sistine Chapel

The Sistine Chapel ( ; ; ) is a chapel in the Apostolic Palace, the pope's official residence in Vatican City. Originally known as the ''Cappella Magna'' ('Great Chapel'), it takes its name from Pope Sixtus IV, who had it built between 1473 and ...

with its uniquely important decorations and the entire rebuilding of

St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican (), or simply St. Peter's Basilica (; ), is a church of the Italian High Renaissance located in Vatican City, an independent microstate enclaved within the city of Rome, Italy. It was initiall ...

, one of Christendom's most significant churches, were part of this process.

[Ilan Rachum, ''The Renaissance, an Illustrated Encyclopedia'', 1979, Octopus, ]

In the wealthy

Republic of Florence

The Republic of Florence (; Old Italian: ), known officially as the Florentine Republic, was a medieval and early modern state that was centered on the Italian city of Florence in Tuscany, Italy. The republic originated in 1115, when the Flor ...

, the impetus for church-building was more civic than spiritual. The unfinished state of the enormous

Florence Cathedral

Florence Cathedral (), formally the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower ( ), is the cathedral of the Catholic Archdiocese of Florence in Florence, Italy. Commenced in 1296 in the Gothic style to a design of Arnolfo di Cambio and completed b ...

dedicated to the

Blessed Virgin Mary

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

did no honour to the city under her patronage. However, as the technology and finance were found to complete it, the rising dome did credit not only to the Virgin Mary, its architect and the Church but also to the

Signoria

A ''signoria'' () was the governing authority in many of the Italian city-states during the Medieval and Renaissance periods.

The word ''signoria'' comes from ''signore'' (), or "lord", an abstract noun meaning (roughly) "government", "governi ...

, the Guilds and the sectors of the city from which the manpower to construct it was drawn. The dome inspired further religious works in Florence.

Philosophic

The development of printed books, the rediscovery of ancient writings, the expanding of political and trade contacts and the exploration of the world all increased knowledge and the desire for education.

The reading of philosophies that were not based on Christian theology led to the development of

humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

through which it was clear that while God had established and maintained order in the Universe, it was the role of Man to establish and maintain order in Society.

Civil

Through humanism, civic pride and the promotion of civil peace and order were seen as the marks of citizenship. This led to the building of structures such as Brunelleschi's

Hospital of the Innocents with its elegant colonnade forming a link between the charitable building and the public square, and the

Laurentian Library

The Laurentian Library (Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana or BML) is a historic library in Florence, Italy, containing more than 11,000 manuscripts and 4,500 early printed books. Built in a cloister of the Medicean Basilica di San Lorenzo di Firenze u ...

where the collection of books established by the Medici family could be consulted by scholars.

[ Helen Gardner, ''Art Through the Ages'', 5th edition, Harcourt, Brace and World.]

Some major ecclesiastical building works were also commissioned, not by the church, but by guilds representing the wealth and power of the city. Brunelleschi's dome at Florence Cathedral, more than any other building, belonged to the populace because the construction of each of the eight segments was achieved by a different quarter of the city.

Patronage

As in the

Platonic Academy

The Academy (), variously known as Plato's Academy, or the Platonic Academy, was founded in Classical Athens, Athens by Plato ''wikt:circa, circa'' 387 BC. The academy is regarded as the first institution of higher education in the west, where ...

of

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, it was seen by those of Humanist understanding that those people who had the benefit of wealth and education ought to promote the pursuit of learning and the creation of that which was beautiful. To this end, wealthy families—the

Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

of Florence, the

Gonzaga of Mantua, the

Farnese in Rome, the

Sforzas

The House of Sforza () was a ruling family of Renaissance Italy, based in Milan. Sforza rule began with the family's acquisition of the Duchy of Milan following the extinction of the Visconti family in the mid-15th century and ended with the de ...

in Milan—gathered around them people of learning and ability, promoting the skills and creating employment for the most talented artists and architects of their day.

Rise of architectural theory

During the Renaissance, architecture became not only a question of practice, but also a matter for theoretical discussion.

Printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The ...

played a large role in the dissemination of ideas.

* The first treatise on architecture was ("On the Subject of Building") by

Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, Catholic priest, priest, linguistics, linguist, philosopher, and cryptography, cryptographer; he epitomised the natu ...

in 1450. It was to some degree dependent on

Vitruvius

Vitruvius ( ; ; –70 BC – after ) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work titled . As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissan ...

's ''

De architectura

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture written by the Ancient Rome, Roman architect and military engineer Vitruvius, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesa ...

'', a manuscript of which was discovered in 1414 in a library in Switzerland. ''De re aedificatoria'' in 1485 became the first printed book on architecture.

*

Sebastiano Serlio

Sebastiano Serlio (6 September 1475 – c. 1554) was an Italian Mannerist architect, who was part of the Italian team building the Palace of Fontainebleau. Serlio helped canonize the classical orders of architecture in his influential treatise ...

(1475 – c. 1554) produced the next important text, the first volume of which appeared in Venice in 1537; it was entitled ''Regole generali d'architettura'' ("General Rules of Architecture"). It is known as Serlio's "Fourth Book" since it was the fourth in Serlio's original plan of a treatise in seven books. In all, five books were published.

* In 1570,

Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( , ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be on ...

(1508–1580) published ''

I quattro libri dell'architettura'' ("The Four Books of Architecture") in

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. This book was widely printed and responsible to a great degree for spreading the ideas of the Renaissance through Europe. All these books were intended to be read and studied not only by architects, but also by patrons.

Spread of the Renaissance in Italy

In the 15th century the courts of certain other Italian states became centres for spreading of Renaissance philosophy, art and architecture.

In

Mantua

Mantua ( ; ; Lombard language, Lombard and ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Italian region of Lombardy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, eponymous province.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the "Italian Capital of Culture". In 2 ...

at the court of the

Gonzaga, Alberti designed two churches, the

Basilica of Sant'Andrea and

San Sebastiano.

Urbino

Urbino ( , ; Romagnol: ''Urbìn'') is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Italy, Italian region of Marche, southwest of Pesaro, a World Heritage Site notable for a remarkable historical legacy of independent Renaissance culture, especially und ...

was an

important centre with the

Ducal Palace being constructed for

Federico da Montefeltro

Federico da Montefeltro, also known as Federico III da Montefeltro Order of the Garter, KG (7 June 1422 – 10 September 1482), was one of the most successful mercenary captains (''condottiero, condottieri'') of the Italian Renaissance, and Duk ...

in the mid 15th century. The Duke employed

Luciano Laurana

Luciano Laurana (Lutiano Dellaurana, ) (c. 1420 – 1479) was a Dalmatian Italian architect and engineer from the historic Vrana settlement near the town of Zadar in Dalmatia, (today in Croatia, then part of the Republic of Venice) After educatio ...

from

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

, renowned for his expertise at fortification. The design incorporates much of the earlier medieval building and includes an unusual turreted three-storeyed façade. Laurana was assisted by Francesco di Giorgio Martini. Later parts of the building are clearly Florentine in style, particularly the inner courtyard, but it is not known who the designer was.

Ferrara

Ferrara (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy, capital of the province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main ...

, under the

Este, was expanded in the late 15th century, with several new palaces being built such as the

Palazzo dei Diamanti

Palazzo dei Diamanti is a Renaissance palace located on Corso Ercole I d'Este 21 in Ferrara, region of Emilia Romagna, Italy. The main floor of the Palace houses the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Ferrara (National Painting Gallery of Ferrara).

History

T ...

and

Palazzo Schifanoia

Palazzo Schifanoia is a Renaissance palace in Ferrara, Emilia-Romagna (Italy) built for the House of Este, Este family. The name "Schifanoia" is thought to originate from "schifare la noia" meaning literally to "escape from boredom" which descri ...

for

Borso d'Este

image:Borso d'Este.jpg, Borso d'Este, attributed to Vicino da Ferrara, Pinacoteca of the Castello Sforzesco, Sforza Castle in Milan, Italy.

Borso d'Este (1413 – 20 August 1471) was the first duke of Ferrara and duke of Modena, Modena, which he ...

.

In

Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, under the

Visconti

Visconti is a surname which may refer to:

Italian noble families

* Visconti of Milan, ruled Milan from 1277 to 1447

** Visconti di Modrone, collateral branch of the Visconti of Milan

* Visconti of Pisa and Sardinia, ruled Gallura in Sardinia from ...

, the

Certosa di Pavia

The Certosa di Pavia is a monastery complex in Lombardy, Northern Italy, situated near a small village of the same name in the Province of Pavia, north of Pavia. Built from 1396 to 1495, it was once located at the end of the Visconti Park a l ...

was completed, and then later under the

Sforza

The House of Sforza () was a ruling family of Renaissance Italy, based in Milan. Sforza rule began with the family's acquisition of the Duchy of Milan following the extinction of the Visconti of Milan, Visconti family in the mid-15th century and ...

, the

Castello Sforzesco

The Sforza Castle ( ; ) is a medieval fortification located in Milan, northern Italy. It was built in the 15th century by Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, on the remnants of a 14th-century fortification. Later renovated and enlarged, in the 1 ...

was built.

developed a particularly distinctive character because of local conditions.

San Zaccaria

The Church of San Zaccaria is a 15th-century former monastic church in central Venice. It is a large edifice located in the Campo San Zaccaria, just off the waterfront to the southeast of Piazza San Marco and St Mark's Basilica. It is dedicated ...

received its Renaissance façade at the hands of

Antonio Gambello and

Mauro Codussi

Mauro Codussi (1440–1504) was an Italian architect of the early-Renaissance, active mostly in Venice. The name is also rendered as ''Coducci''. He was one of the first to bring the classical style of the early renaissance to Venice to replace th ...

, begun in the 1480s.

Giovanni Maria Falconetto

Giovanni Maria Falconetto (c. 1468–1535) was an Italian architect and painter. He designed among the first high Renaissance buildings in Padua, the '' Loggia Cornaro'', a garden ''loggia'' for Alvise Cornaro built as a Roman doric arcade. Alo ...

, the Veronese architect-sculptor, introduced Renaissance architecture to Padua with the

Loggia and Odeo Cornaro in the garden of

Alvise Cornaro

Alvise Cornaro, often Italianised Luigi (1484, 1467 or 1464 gives a birth date of 1467 – 8 May 1566), was a Venice, Venetian nobleman and patron of arts, also remembered for his four books of ''Discorsi'' (published 1583–1595) about the ...

.

In southern Italy, Renaissance masters were called to Naples by

Alfonso V of Aragon

Alfonso the Magnanimous (Alfons el Magnànim in Catalan language, Catalan) (139627 June 1458) was King of Aragon and King of Sicily (as Alfons V) and the ruler of the Crown of Aragon from 1416 and King of Naples (as Alfons I) from 1442 until his ...

after his conquest of the

Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

. The most notable examples of Renaissance architecture in that city are the

Cappella Caracciolo, attributed to Bramante, and the

Palazzo Orsini di Gravina, built by

Gabriele d'Angelo between 1513 and 1549.

Characteristics

The

Classical order

An order in architecture is a certain assemblage of parts subject to uniform established proportions, regulated by the office that each part has to perform.

Coming down to the present from Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman civiliz ...

s were analysed and reconstructed to serve new purposes. While the obvious distinguishing features of Classical Roman architecture were adopted by Renaissance architects, the forms and purposes of buildings had changed over time, as had the structure of cities. Among the earliest buildings of the reborn Classicism were the type of churches that the Romans had never constructed. Neither were there models for the type of large city dwellings required by wealthy merchants of the 15th century. Conversely, there was no call for enormous sporting fixtures and

public bath houses such as the Romans had built.

Plan

The plans of Renaissance buildings have a square, symmetrical appearance in which proportions are usually based on a module. Within a church, the module is often the width of an aisle. The need to integrate the design of the plan with the façade was introduced as an issue in the work of

Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi (1377 – 15 April 1446), commonly known as Filippo Brunelleschi ( ; ) and also nicknamed Pippo by Leon Battista Alberti, was an Italian architect, designer, goldsmith and sculptor. He is considered to ...

, but he was never able to carry this aspect of his work into fruition. The first building to demonstrate this was

Basilica of Sant'Andrea, Mantua

The Basilica of Sant'Andrea is a Roman Catholic co-cathedral and minor basilica in Mantua, Lombardy (Italy). It is one of the major works of 15th-century Renaissance architecture in Northern Italy. Commissioned by Ludovico III Gonzaga, the churc ...

by

Leone Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher, and cryptographer; he epitomised the nature of those identified now as polymaths. H ...

. The development of the plan in secular architecture was to take place in the 16th century and culminated with the work of

Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( , ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be one ...

.

Façade

Façade

A façade or facade (; ) is generally the front part or exterior of a building. It is a loanword from the French language, French (), which means "frontage" or "face".

In architecture, the façade of a building is often the most important asp ...

s are symmetrical around their vertical axis. Church façades are generally surmounted by a

pediment

Pediments are a form of gable in classical architecture, usually of a triangular shape. Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the cornice (an elaborated lintel), or entablature if supported by columns.Summerson, 130 In an ...

and organised by a system of

pilaster

In architecture, a pilaster is both a load-bearing section of thickened wall or column integrated into a wall, and a purely decorative element in classical architecture which gives the appearance of a supporting column and articulates an ext ...

s, arches and

entablature

An entablature (; nativization of Italian , from "in" and "table") is the superstructure of moldings and bands which lies horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Entablatures are major elements of classical architecture, and ...

s. The columns and windows show a progression towards the centre. One of the first true Renaissance façades was

Pienza Cathedral (1459–1462), which has been attributed to the Florentine architect Bernardo Gambarelli (known as

Rossellino Rossellino is an Italian surname, or nickname referring to red hair. Notable people with the surname, or in the case of the Gamberelli brothers, nickname, include:

*Bernardo Rossellino

Bernardo di Matteo del Borra Gamberelli (1409–1464), bett ...

) with

Leone Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher, and cryptographer; he epitomised the nature of those identified now as polymaths. H ...

perhaps having some responsibility in its design as well.

Domestic buildings are often surmounted by a

cornice

In architecture, a cornice (from the Italian ''cornice'' meaning "ledge") is generally any horizontal decorative Moulding (decorative), moulding that crowns a building or furniture element—for example, the cornice over a door or window, ar ...

. There is a regular repetition of openings on each floor, and the centrally placed door is marked by a feature such as a balcony, or rusticated surround. An early and much copied prototype was the façade for the

Palazzo Rucellai

Palazzo Rucellai is a palatial fifteenth-century townhouse on the Via della Vigna Nuova in Florence, Italy. The Rucellai Palace is believed by most scholars to have been designed for Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai by Leon Battista Alberti between 1446 ...

(1446 and 1451) in Florence with its three registers of

pilasters

In architecture, a pilaster is both a load-bearing section of thickened wall or column integrated into a wall, and a purely decorative element in classical architecture which gives the appearance of a supporting column and articulates an ext ...

.

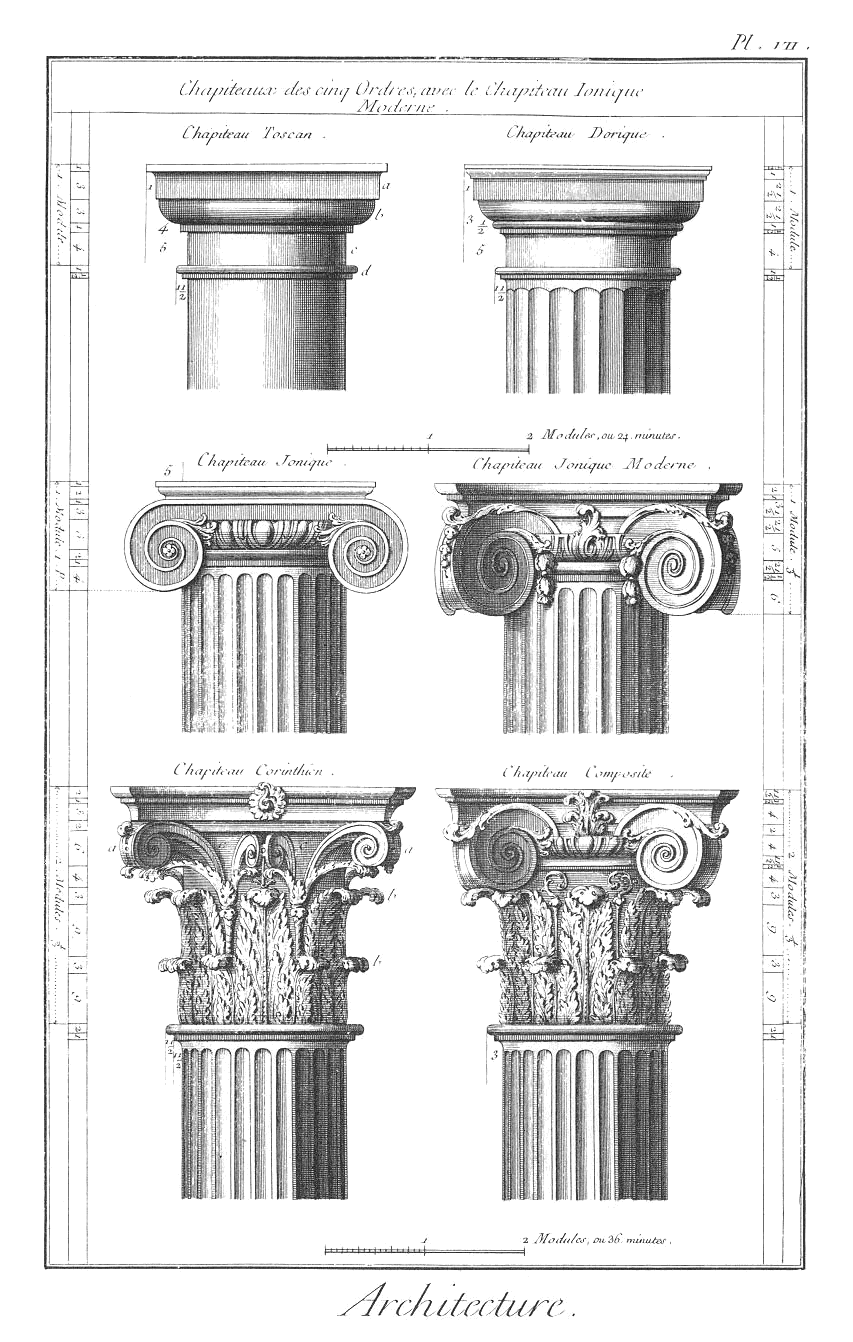

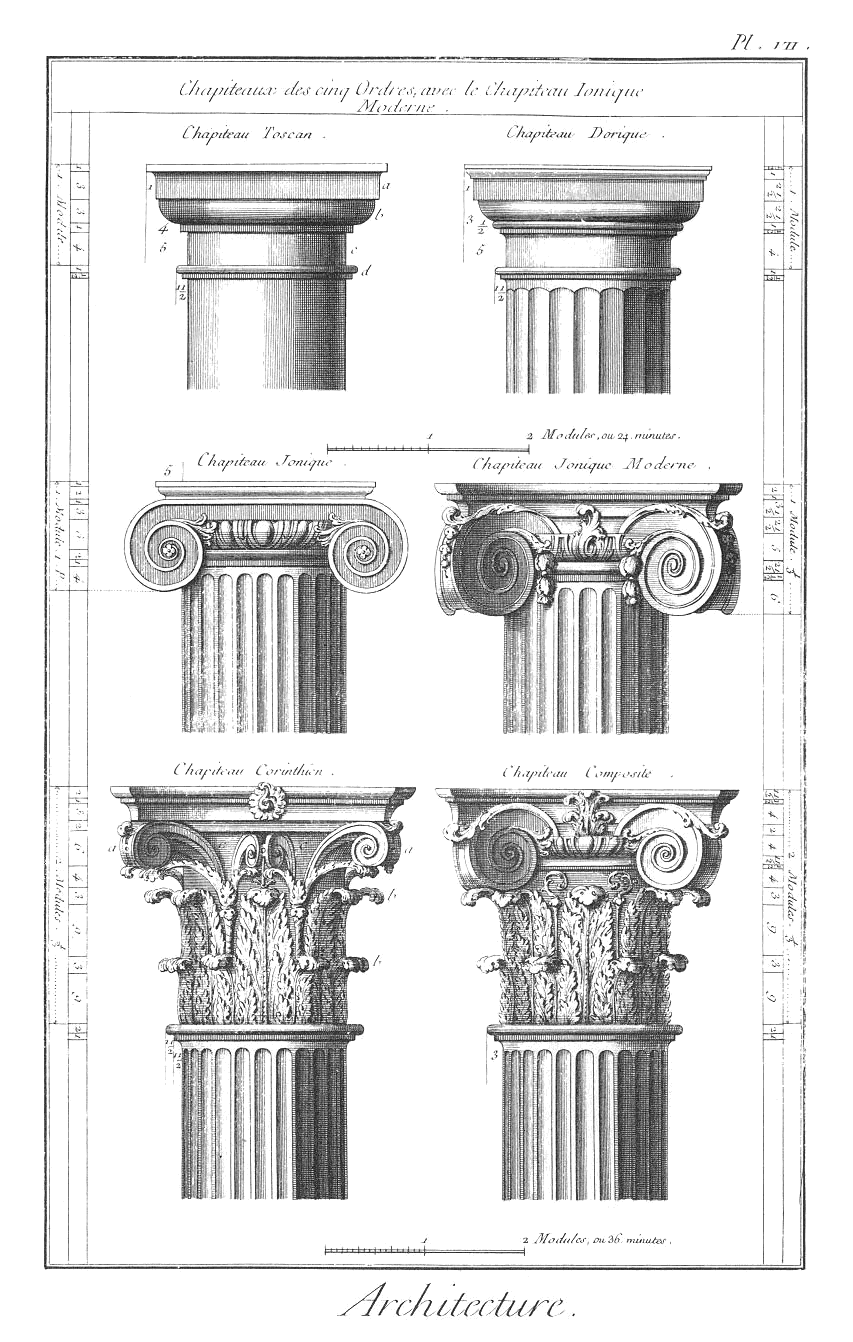

Columns and pilasters

Roman and Greek orders of columns are used:

Tuscan,

Doric,

Ionic,

Corinthian and

Composite

Composite or compositing may refer to:

Materials

* Composite material, a material that is made from several different substances

** Metal matrix composite, composed of metal and other parts

** Cermet, a composite of ceramic and metallic material ...

. The orders can either be structural, supporting an arcade or architrave, or purely decorative, set against a wall in the form of pilasters. During the Renaissance, architects aimed to use columns,

pilaster

In architecture, a pilaster is both a load-bearing section of thickened wall or column integrated into a wall, and a purely decorative element in classical architecture which gives the appearance of a supporting column and articulates an ext ...

s, and

entablatures

An entablature (; nativization of Italian , from "in" and "table") is the superstructure of moldings and bands which lies horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Entablatures are major elements of classical architecture, and ...

as an integrated system. One of the first buildings to use pilasters as an integrated system was in the

Old Sacristy (1421–1440) by Brunelleschi.

Arches

Arches are semi-circular or (in the Mannerist style) segmental. Arches are often used in arcades, supported on piers or columns with capitals. There may be a section of entablature between the capital and the springing of the arch. Alberti was one of the first to use the arch on a monumental scale at the

Basilica of Sant'Andrea, Mantua

The Basilica of Sant'Andrea is a Roman Catholic co-cathedral and minor basilica in Mantua, Lombardy (Italy). It is one of the major works of 15th-century Renaissance architecture in Northern Italy. Commissioned by Ludovico III Gonzaga, the churc ...

.

Vaults

Vaults do not have ribs. They are semi-circular or segmental and on a square plan, unlike the Gothic vault which is frequently rectangular. The

barrel vault

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

is returned to architectural vocabulary as at St. Andrea in Mantua.

Domes

The dome is used frequently, both as a very large structural feature that is visible from the exterior, and also as a means of roofing smaller spaces where they are only visible internally. After the success of the dome in Brunelleschi's design for

Florence Cathedral

Florence Cathedral (), formally the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower ( ), is the cathedral of the Catholic Archdiocese of Florence in Florence, Italy. Commenced in 1296 in the Gothic style to a design of Arnolfo di Cambio and completed b ...

and its use in Bramante's plan for

St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican (), or simply St. Peter's Basilica (; ), is a church of the Italian High Renaissance located in Vatican City, an independent microstate enclaved within the city of Rome, Italy. It was initiall ...

(1506) in Rome, the dome became an indispensable element in church architecture and later even for secular architecture, such as Palladio's

Villa Rotonda

Villa La Rotonda is a Renaissance villa just outside Vicenza in Northern Italy designed by Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, and begun in 1567, though not completed until the 1590s. The villa's official name is Villa Almerico Capra V ...

.

Ceilings

Roofs are fitted with flat or

coffered

A coffer (or coffering) in architecture is a series of sunken panels in the shape of a square, rectangle, or octagon in a ceiling, soffit or vault.

A series of these sunken panels was often used as decoration for a ceiling or a vault, also ...

ceilings. They are not left open as in Medieval architecture. They are frequently painted or decorated.

Doors

Door

A door is a hinged or otherwise movable barrier that allows ingress (entry) into and egress (exit) from an enclosure. The created opening in the wall is a ''doorway'' or ''portal''. A door's essential and primary purpose is to provide securit ...

s usually have square lintels. They may be set with in an arch or surmounted by a triangular or segmental pediment. Openings that do not have doors are usually arched and frequently have a large or decorative keystone.

Windows

Windows may be paired and set within a

semi-circular arch

In architecture, a semicircular arch is an arch with an intrados (inner surface) shaped like a semicircle. This type of arch was adopted and very widely used by the Romans, thus becoming permanently associated with Roman architecture.

Termi ...

. They may have square lintels and triangular or segmental

pediment

Pediments are a form of gable in classical architecture, usually of a triangular shape. Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the cornice (an elaborated lintel), or entablature if supported by columns.Summerson, 130 In an ...

s, which are often used alternately. Emblematic in this respect is the

Palazzo Farnese

Palazzo Farnese () or Farnese Palace is one of the most important High Renaissance palaces in Rome. Owned by the Italian Republic, it was given to the French government in 1936 for a period of 99 years, and currently serves as the French e ...

in Rome, begun in 1517.

In the Mannerist period the

Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

arch was employed, using a motif of a high semi-circular topped opening flanked with two lower square-topped openings. Windows are used to bring light into the building and in domestic architecture, to give views. Stained glass, although sometimes present, is not a feature.

Walls

External walls are generally constructed of brick, rendered, or faced with stone in highly finished

ashlar

Ashlar () is a cut and dressed rock (geology), stone, worked using a chisel to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular in shape. The term can also refer to a structure built from such stones.

Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, a ...

masonry, laid in straight courses. The corners of buildings are often emphasized by rusticated

quoins

Quoins ( or ) are masonry blocks at the corner of a wall. Some are structural, providing strength for a wall made with inferior stone or rubble, while others merely add aesthetic detail to a corner. According to one 19th-century encyclopedia, ...

. Basements and ground floors were often

rusticated, as at the

Palazzo Medici Riccardi

The Palazzo Medici, also called the Palazzo Medici Riccardi after the later family that acquired and expanded it, is a 15th-century Renaissance palace in Florence, Italy. It was built for the Medici family, who dominated the politics of the Repu ...

(1444–1460) in Florence. Internal walls are smoothly plastered and surfaced with

lime wash. For more formal spaces, internal surfaces are decorated with

fresco

Fresco ( or frescoes) is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting become ...

es.

Details

Courses, mouldings and all decorative details are carved with great precision. Studying and mastering the details of the ancient Romans was one of the important aspects of Renaissance theory. The different orders each required different sets of details. Some architects were stricter in their use of classical details than others, but there was also a good deal of innovation in solving problems, especially at corners. Mouldings stand out around doors and windows rather than being recessed, as in Gothic architecture. Sculptured figures may be set in niches or placed on plinths. They are not integral to the building as in Medieval architecture.

Banister Fletcher

Sir Banister Flight Fletcher (15 February 1866 – 17 August 1953) was an English architect and architectural historian, as was his father, also named Banister Fletcher. They wrote the standard textbook ''A History of Architecture'' ...

, ''History of Architecture on the Comparative Method''(first published 1896, current edition 2001, Elsevier Science & Technology ).

Early Renaissance

The leading architects of the Early Renaissance or Quattrocento were

Filippo Brunelleschi

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi (1377 – 15 April 1446), commonly known as Filippo Brunelleschi ( ; ) and also nicknamed Pippo by Leon Battista Alberti, was an Italian architect, designer, goldsmith and sculptor. He is considered to ...

,

Michelozzo

Michelozzo di Bartolomeo Michelozzi (; – 7 October 1472), known mononymously as Michelozzo, was an Italian architect and sculptor. Considered one of the great pioneers of architecture during the Renaissance, Michelozzo was a favored Medici ...

and

Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, Catholic priest, priest, linguistics, linguist, philosopher, and cryptography, cryptographer; he epitomised the natu ...

.

Brunelleschi

The person generally credited with bringing about the Renaissance view of architecture is Filippo Brunelleschi, (1377–1446). The underlying feature of the work of Brunelleschi was "order".

In the early 15th century, Brunelleschi began to look at the world to see what the rules were that governed one's way of seeing. He observed that the way one sees regular structures such as the

Florence Baptistery

The Florence Baptistery, also known as the Baptistery of Saint John (), is a religious building in Florence, Italy. Dedicated to the patron saint of the city, John the Baptist, it has been a focus of religious, civic, and artistic life since its ...

and the tiled pavement surrounding it follows a mathematical order –

linear perspective

Linear or point-projection perspective () is one of two types of graphical projection perspective in the graphic arts; the other is parallel projection. Linear perspective is an approximate representation, generally on a flat surface, of ...

.

The buildings remaining among the ruins of ancient Rome appeared to respect a simple mathematical order in the way that Gothic buildings did not. One incontrovertible rule governed all

Ancient Roman architecture

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical ancient Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often consi ...

– a semi-circular arch is exactly twice as wide as it is high. A fixed proportion with implications of such magnitude occurred nowhere in

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High Middle Ages, High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It evolved f ...

. A Gothic pointed arch could be extended upwards or flattened to any proportion that suited the location. Arches of differing angles frequently occurred within the same structure. No set rules of proportion applied.

From the observation of the architecture of Rome came a desire for symmetry and careful proportion in which the form and composition of the building as a whole and all its subsidiary details have fixed relationships, each section in proportion to the next, and the architectural features serving to define exactly what those rules of proportion are.

[Robert Erich Wolf and Ronald Millen, ''Renaissance and Mannerist Art'', 1968, Harry N. Abrams.] Brunelleschi gained the support of a number of wealthy Florentine patrons, including the Silk Guild and

Cosimo de' Medici

Cosimo di Giovanni de' Medici (27 September 1389 – 1 August 1464) was an Italian banker and politician who established the House of Medici, Medici family as effective rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance. His power derive ...

.

Florence Cathedral

Brunelleschi's first major architectural commission was for the enormous brick dome which covers the central space of Florence's cathedral, designed by

Arnolfo di Cambio

Arnolfo di Cambio ( – 1300/1310) was an Italian architect and sculptor of the Duecento, who began as a lead assistant to Nicola Pisano. He is documented as being ''capomaestro'' or Head of Works for Florence Cathedral in 1300, and designed th ...

in the 14th century but left unroofed. While often described as the first building of the Renaissance, Brunelleschi's daring design utilises the pointed Gothic arch and Gothic ribs that were apparently planned by Arnolfo. It seems certain, however, that while stylistically Gothic, in keeping with the building it surmounts, the dome is in fact structurally influenced by the great dome of Ancient Rome, which Brunelleschi could hardly have ignored in seeking a solution. This is the dome of the

Pantheon, a circular temple, now a church.

Inside the Pantheon's single-shell concrete dome is coffering which greatly decreases the weight. The vertical partitions of the coffering effectively serve as ribs, although this feature does not dominate visually. At the apex of the Pantheon's dome is an opening, 8 meters across. Brunelleschi was aware that a dome of enormous proportion could in fact be engineered without a keystone. The dome in Florence is supported by the eight large ribs and sixteen more internal ones holding a brick shell, with the bricks arranged in a herringbone manner. Although the techniques employed are different, in practice, both domes comprise a thick network of ribs supporting very much lighter and thinner infilling. And both have a large opening at the top.

San Lorenzo

The new architectural philosophy of the Renaissance is best demonstrated in the churches of San Lorenzo, and

Santo Spirito, Florence

The Basilica di Santo Spirito ("Basilica of the Holy Spirit") is a church in Florence, Italy. Usually referred to simply as Santo Spirito, it is located in the Oltrarno quarter, facing the square with the same name. The interior of the building ...

. Designed by Brunelleschi in about 1425 and 1428 respectively, both have the shape of the

Latin cross. Each has a modular plan, each portion being a multiple of the square bay of the aisle. This same formula controlled also the vertical dimensions. In the case of Santo Spirito, which is entirely regular in plan, transepts and chancel are identical, while the nave is an extended version of these. In 1434 Brunelleschi designed the first Renaissance centrally planned building,

Santa Maria degli Angeli, Florence

Santa Maria degli Angeli (St. Mary of the Angels) is the former church of a now-defunct monastery of that name in Florence, Italy. It belonged to the Camaldolese order, which was a reformed branch of the Benedictines. The order is based on the her ...

. It is composed of a central

octagon

In geometry, an octagon () is an eight-sided polygon or 8-gon.

A '' regular octagon'' has Schläfli symbol and can also be constructed as a quasiregular truncated square, t, which alternates two types of edges. A truncated octagon, t is a ...

surrounded by a circuit of eight smaller chapels. From this date onwards numerous churches were built in variations of these designs.

Michelozzo

Michelozzo Michelozzi (1396–1472), was another architect under patronage of the

Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

family, his most famous work being the

Palazzo Medici Riccardi

The Palazzo Medici, also called the Palazzo Medici Riccardi after the later family that acquired and expanded it, is a 15th-century Renaissance palace in Florence, Italy. It was built for the Medici family, who dominated the politics of the Repu ...

, which he was commissioned to design for

Cosimo de' Medici

Cosimo di Giovanni de' Medici (27 September 1389 – 1 August 1464) was an Italian banker and politician who established the House of Medici, Medici family as effective rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance. His power derive ...

in 1444. A decade later he built the

Villa Medici, Fiesole. Among his other works for Cosimo are the library at the Convent of

San Marco, Florence

San Marco is a Catholic Church, Catholic religious complex in Florence, Italy. It comprises a church (building), church and a convent. The convent, which is now the Museo Nazionale di San Marco, has three claims to fame. During the 15th century ...

. He went into exile in Venice for a time with his patron. He was one of the first architects to work in the Renaissance style outside Italy, building a palace at

Dubrovnik

Dubrovnik, historically known as Ragusa, is a city in southern Dalmatia, Croatia, by the Adriatic Sea. It is one of the most prominent tourist destinations in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean, a Port, seaport and the centre of the Dubrovni ...

.

The Palazzo Medici Riccardi is Classical in the details of its pedimented windows and recessed doors, but, unlike the works of Brunelleschi and Alberti, there are no

classical orders

An order in architecture is a certain assemblage of parts subject to uniform established proportions, regulated by the office that each part has to perform.

Coming down to the present from Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman civiliz ...

of columns in evidence. Instead, Michelozzo has respected the Florentine liking for rusticated stone. He has seemingly created three orders out of the three defined rusticated levels, the whole being surmounted by an enormous Roman-style cornice which juts out over the street by 2.5 meters.

Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, Catholic priest, priest, linguistics, linguist, philosopher, and cryptography, cryptographer; he epitomised the natu ...

, born in Genoa (1402–1472), was an important

Humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

theoretician and designer whose book on architecture ''De re Aedificatoria'' was to have lasting effect. An aspect of

Renaissance humanism was an emphasis of the anatomy of nature, in particular the human form, a science first studied by the Ancient Greeks. Humanism made man the measure of things. Alberti perceived the architect as a person with great social responsibilities.

He designed a number of buildings, but unlike Brunelleschi, he did not see himself as a builder in a practical sense and so left the supervision of the work to others. Miraculously, one of his greatest designs, that of the

Basilica of Sant'Andrea, Mantua

The Basilica of Sant'Andrea is a Roman Catholic co-cathedral and minor basilica in Mantua, Lombardy (Italy). It is one of the major works of 15th-century Renaissance architecture in Northern Italy. Commissioned by Ludovico III Gonzaga, the churc ...

, was brought to completion with its character essentially intact. Not so the

Church of San Francesco in

Rimini

Rimini ( , ; or ; ) is a city in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy.

Sprawling along the Adriatic Sea, Rimini is situated at a strategically-important north-south passage along the coast at the southern tip of the Po Valley. It is ...

, a rebuilding of a Gothic structure, which, like Sant'Andrea, was to have a façade reminiscent of a Roman triumphal arch. This was left sadly incomplete.

Sant'Andrea is an extremely dynamic building both without and within. Its triumphal façade is marked by extreme contrasts. The projection of the order of pilasters that define the architectural elements, but are essentially non-functional, is very shallow. This contrasts with the gaping deeply recessed arch which makes a huge portico before the main door. The size of this arch is in direct contrast to the two low square-topped openings that frame it. The light and shade play dramatically over the surface of the building because of the shallowness of its mouldings and the depth of its porch. In the interior Alberti has dispensed with the traditional nave and aisles. Instead there is a slow and majestic progression of alternating tall arches and low square doorways, repeating the "triumphal arch" motif of the façade.

Two of Alberti's best known buildings are in Florence, the

Palazzo Rucellai

Palazzo Rucellai is a palatial fifteenth-century townhouse on the Via della Vigna Nuova in Florence, Italy. The Rucellai Palace is believed by most scholars to have been designed for Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai by Leon Battista Alberti between 1446 ...

and at Santa Maria Novella. For the palace, Alberti applied the classical orders of columns to the façade on the three levels, 1446–1451. At Santa Maria Novella he was commissioned to finish the decoration of the façade. He completed the design in 1456 but the work was not finished until 1470.

The lower section of the building had Gothic niches and typical polychrome marble decoration. There was a large Oculus (architecture), ocular window in the end of the nave which had to be taken into account. Alberti simply respected what was already in place, and the Florentine tradition for polychrome that was well established at the Baptistery of Florence, Baptistery of San Giovanni, the most revered building in the city. The decoration, being mainly polychrome marble, is mostly very flat in nature, but a sort of order is established by the regular compartments and the circular motifs which repeat the shape of the round window.

For the first time, Alberti linked the lower roofs of the aisles to nave using two large scrolls. These were to become a standard Renaissance device for solving the problem of different roof heights and bridge the space between horizontal and vertical surfaces.

[Nikolaus Pevsner, ''An Outline of European Architecture'', Pelican, 1964, ISBN unknown]

High Renaissance

In the late 15th century and early 16th century, architects such as Bramante, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and others showed a mastery of the revived style and ability to apply it to buildings such as churches and city palazzo which were quite different from the structures of ancient times. The style became more decorated and ornamental, statuary, domes and cupolas becoming very evident. The architectural period is known as the "High Renaissance" and coincides with the age of Leonardo da Vinci, Leonardo,

Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6March 147518February 1564), known mononymously as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspir ...

and Raphael.

Bramante

Donato Bramante

Donato Bramante (1444 – 11 April 1514), born as Donato di Pascuccio d'Antonio and also known as Bramante Lazzari, was an Italian architect and painter. He introduced Renaissance architecture to Milan and the High Renaissance style to Rom ...

, (1444–1514), was born in

Urbino

Urbino ( , ; Romagnol: ''Urbìn'') is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Italy, Italian region of Marche, southwest of Pesaro, a World Heritage Site notable for a remarkable historical legacy of independent Renaissance culture, especially und ...

and turned from painting to architecture, finding his first important patronage under Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, for whom he produced a number of buildings over 20 years. After the fall of

Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

to the French in 1499, Bramante travelled to Rome where he achieved great success under papal patronage.

Bramante's finest architectural achievement in Milan is his addition of crossing and choir to the abbey church of Santa Maria delle Grazie (Milan). This is a brick structure, the form of which owes much to the Northern Italian tradition of square domed Baptistery, baptisteries. The new building is almost centrally planned, except that, because of the site, the chancel extends further than the transept arms. The hemispherical dome, of approximately 20 metres across, rises up hidden inside an octagonal drum (architecture), drum pierced at the upper level with arched classical openings. The whole exterior has delineated details decorated with the local terracotta ornamentation. From 1488 to 1492 he worked for Ascanio Sforza on Pavia Cathedral, on which he imposed a central plan scheme and built some apses and the crypt, inspired by the thermal baths of the Roman age.

In Rome Bramante created what has been described as "a perfect architectural gem",

the San Pietro in Montorio#The Tempietto, Tempietto in the Cloister of

San Pietro in Montorio

San Pietro in Montorio (English: "Saint Peter on the Golden Mountain") is a church in Rome, Italy, which includes in its courtyard the ''Tempietto'', a small commemorative ''martyrium'' ('martyry') built by Donato Bramante.

History

The Church o ...

. This small circular temple marks the spot where St Peter was martyred and is thus the most sacred site in Rome. The building adapts the style apparent in the remains of the Temple of Vesta, the most sacred site of Ancient Rome. It is enclosed by and in spatial contrast with the cloister which surrounds it. As approached from the cloister, as in the :File:Tempietto, links.jpg, picture above, it is seen framed by an arch and columns, the shape of which are echoed in its free-standing form.

Bramante went on to work on the Apostolic Palace, where he designed the Cortile del Belvedere. In 1506 his design for Pope Julius II's rebuilding of

St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican (), or simply St. Peter's Basilica (; ), is a church of the Italian High Renaissance located in Vatican City, an independent microstate enclaved within the city of Rome, Italy. It was initiall ...

was selected, and the foundation stone laid. After Bramante's death and many changes of plan,

Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6March 147518February 1564), known mononymously as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspir ...

, as chief architect, reverted to something closer to Bramante's original proposal.

Sangallo

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger (1485–1546) was one of a family of Military engineering, military engineers. His uncle, Giuliano da Sangallo was one of those who submitted a plan for the rebuilding of St Peter's and was briefly a co-director of the project, with Raphael.

Antonio da Sangallo also submitted a plan for St Peter's and became the chief architect after the death of Raphael, to be succeeded himself by Michelangelo.

His fame does not rest upon his association with St Peter's but in his building of the Farnese Palace, "the grandest palace of this period", started in 1530.

The impression of grandness lies in part in its sheer size, (56 m long by 29.5 meters high) and in its lofty location overlooking a broad piazza. Unusually for such a large and luxurious house of the time, it was built principally of stuccoed brick, rather than of stone. Against the smooth pink-washed walls the stone quoins of the corners, the massive rusticated portal and the repetition of finely detailed windows produce an elegant effect. The upper of the three equally sized floors was added by Michelangelo. The travertine for its architectural details came not from a quarry, but from the Colosseum.

Raphael

Raphael (1483–1520), born in

Urbino