Religious Leader on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Clergy are formal leaders within established

Clergy are formal leaders within established

In Anglicanism, clergy consist of the orders of

In Anglicanism, clergy consist of the orders of

File:SirGeorgeFlemingBt2.jpg, Sir George Fleming, 2nd Baronet, British churchman.

File:CWLeffingwell.JPG,

, a dicastery of Roman curia. Canon Law indicates (canon 207) that " divine institution, there are among the Christian faithful in the Church sacred ministers who in law are also called clerics; the other members of the Christian faithful are called lay persons". This distinction of a separate ministry was formed in the early times of Christianity; one early source reflecting this distinction, with the three ranks or orders of

The

The

The nearest analogue among Sunni Muslims to the parish priest or pastor, or to the "pulpit

The nearest analogue among Sunni Muslims to the parish priest or pastor, or to the "pulpit

In modern

In modern

Since the early medieval era an additional communal role, the '' Hazzan'' (cantor) has existed as well. Cantors have sometimes been the only functionaries of a synagogue, empowered to undertake religio-civil functions like witnessing marriages. Cantors do provide leadership of actual services, primarily because of their training and expertise in the music and prayer rituals pertaining to them, rather than because of any spiritual or "sacramental" distinction between them and the laity. Cantors as much as rabbis have been recognized by civil authorities in the United States as clergy for legal purposes, mostly for awarding education degrees and their ability to perform weddings, and certify births and deaths.

Additionally, Jewish authorities license '' mohels'', people specially trained by experts in Jewish law and usually also by medical professionals to perform the ritual of circumcision. Traditional Orthodox Judaism does not license women as mohels, but other types of Judaism do. They are appropriately called ''mohelot'' (pl. of ''mohelet,'' f. of mohel). As the ''j., the Jewish News Weekly of Northern California'', states, "...there is no halachic prescription against female mohels, utnone exist in the Orthodox world, where the preference is that the task be undertaken by a Jewish man.". In many places, mohels are also licensed by civil authorities, as circumcision is technically a surgical procedure. Kohanim, who must avoid contact with dead human body parts (such as the removed foreskin) for ritual purity, cannot act as mohels, but some mohels are also either rabbis or cantors.

Another licensed cleric in Judaism is the '' shochet'', who are trained and licensed by religious authorities for kosher slaughter according to ritual law. A Kohen may be a shochet. Most shochetim are ordained rabbis.

Then there is the '' mashgiach/mashgicha''. ''Mashgichim'' are observant Jews who supervise the '' kashrut'' status of a kosher establishment. The ''mashgichim'' must know the Torah laws of ''kashrut'', and how they apply in the environment they are supervising. Obviously, this can vary. In many instances, the ''mashgiach''/''mashgicha'' is a rabbi. This helps, since rabbinical students learn the laws of kosher as part of their syllabus. However, not all ''mashgichim'' are rabbis, and not all rabbis are qualified to be ''mashgichim''.

Since the early medieval era an additional communal role, the '' Hazzan'' (cantor) has existed as well. Cantors have sometimes been the only functionaries of a synagogue, empowered to undertake religio-civil functions like witnessing marriages. Cantors do provide leadership of actual services, primarily because of their training and expertise in the music and prayer rituals pertaining to them, rather than because of any spiritual or "sacramental" distinction between them and the laity. Cantors as much as rabbis have been recognized by civil authorities in the United States as clergy for legal purposes, mostly for awarding education degrees and their ability to perform weddings, and certify births and deaths.

Additionally, Jewish authorities license '' mohels'', people specially trained by experts in Jewish law and usually also by medical professionals to perform the ritual of circumcision. Traditional Orthodox Judaism does not license women as mohels, but other types of Judaism do. They are appropriately called ''mohelot'' (pl. of ''mohelet,'' f. of mohel). As the ''j., the Jewish News Weekly of Northern California'', states, "...there is no halachic prescription against female mohels, utnone exist in the Orthodox world, where the preference is that the task be undertaken by a Jewish man.". In many places, mohels are also licensed by civil authorities, as circumcision is technically a surgical procedure. Kohanim, who must avoid contact with dead human body parts (such as the removed foreskin) for ritual purity, cannot act as mohels, but some mohels are also either rabbis or cantors.

Another licensed cleric in Judaism is the '' shochet'', who are trained and licensed by religious authorities for kosher slaughter according to ritual law. A Kohen may be a shochet. Most shochetim are ordained rabbis.

Then there is the '' mashgiach/mashgicha''. ''Mashgichim'' are observant Jews who supervise the '' kashrut'' status of a kosher establishment. The ''mashgichim'' must know the Torah laws of ''kashrut'', and how they apply in the environment they are supervising. Obviously, this can vary. In many instances, the ''mashgiach''/''mashgicha'' is a rabbi. This helps, since rabbinical students learn the laws of kosher as part of their syllabus. However, not all ''mashgichim'' are rabbis, and not all rabbis are qualified to be ''mashgichim''.

online

* Ruether, Rosemary Radford. "Should Women Want Women Priests or Women-Church?." ''Feminist Theology'' 20.1 (2011): 63–72. * Tucker, Ruth A. and Walter L. Liefeld. ''Daughters of the Church: Women and Ministry from New Testament Times to the Present'' (1987), historical survey of female Christian clergy

"Church Administration"

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

Wlsessays.net

Scholarly articles on Christian Clergy from the Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary Library

University of the West

Buddhist M.Div.

Naropa University

, Buddhist M.Div.

National Association of Christian Ministers

Priesthood of All Believers: Explained and Supported in Scripture {{Authority control Religious terminology Religious occupations Estates (social groups) Positions of authority

Clergy are formal leaders within established

Clergy are formal leaders within established religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural ...

s. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrine

Doctrine (from la, Wikt:doctrina, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification (law), codification of beliefs or a body of teacher, teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given ...

s and practices. Some of the terms used for individual clergy are clergyman, clergywoman, clergyperson, churchman, and cleric, while clerk in holy orders has a long history but is rarely used.

In Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

, the specific names and roles of the clergy vary by denomination and there is a wide range of formal and informal clergy positions, including deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

s, elders, priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

s, bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

s, preachers, pastors, presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning a ...

s, minister

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

s, and the pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

.

In Islam, a religious leader is often known formally or informally as an imam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, se ...

, caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, qadi

A qāḍī ( ar, قاضي, Qāḍī; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a ''sharīʿa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minor ...

, mufti, mullah, muezzin, or ayatollah

Ayatollah ( ; fa, آیتالله, āyatollāh) is an Title of honor, honorific title for high-ranking Twelver Shia clergy in Iran and Iraq that came into widespread usage in the 20th century.

Etymology

The title is originally derived from ...

.

In the Jewish tradition, a religious leader is often a rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

(teacher) or hazzan (cantor).

Etymology

The word ''cleric'' comes from theecclesiastical Latin

Latin, also called Church Latin or Liturgical Latin, is a form of Latin developed to discuss Christian thought in Late Antiquity and used in Christian liturgy, theology, and church administration down to the present day, especially in the Ca ...

''Clericus'', for those belonging to the priestly class. In turn, the source of the Latin word is from the Ecclesiastical Greek ''Klerikos'' (κληρικός), meaning appertaining to an inheritance, in reference to the fact that the Levitical priests of the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

had no inheritance except the Lord. "Clergy" is from two Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligi ...

words, ''clergié'' and ''clergie'', which refer to those with learning and derive from Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin

Classical Latin is the form of Literary Latin recognized as a Literary language, literary standard language, standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. It was used f ...

''clericatus'', from Late Latin

Late Latin ( la, Latinitas serior) is the scholarly name for the form of Literary Latin of late antiquity.Roberts (1996), p. 537. English dictionary definitions of Late Latin date this period from the , and continuing into the 7th century in the ...

''clericus'' (the same word from which "cleric" is derived). "Clerk", which used to mean one ordained to the ministry, also derives from ''clericus''. In the Middle Ages, reading and writing were almost exclusively the domain of the priestly class, and this is the reason for the close relationship of these words. Within Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

, especially in Eastern Christianity

Eastern Christianity comprises Christian traditions and church families that originally developed during classical and late antiquity in Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Northeast Africa, the Fertile Crescent a ...

and formerly in Western Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the term ''cleric'' refers to any individual who has been ordained, including deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

s, priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

s, and bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

s. In Latin Catholicism

, native_name_lang = la

, image = San Giovanni in Laterano - Rome.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt = Façade of the Archbasilica of St. John in Lateran

, caption = Archbasilica of Saint Joh ...

, the tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

was a prerequisite for receiving any of the minor orders or major orders before the tonsure, minor orders, and the subdiaconate

Subdeacon (or sub-deacon) is a minor order or ministry for men in various branches of Christianity. The subdeacon has a specific liturgical role and is placed between the acolyte (or reader) and the deacon in the order of precedence.

Subdeacons in ...

were abolished following the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

. Now, the clerical state is tied to reception of the diaconate. Minor Orders are still given in the Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous ('' sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

, and those who receive those orders are 'minor clerics.'

The use of the word ''cleric'' is also appropriate for Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canoni ...

minor clergy who are tonsured in order not to trivialize orders such as those of Reader in the Eastern Church, or for those who are tonsured yet have no minor or major orders. It is in this sense that the word entered the Arabic language, most commonly in Lebanon from the French, as ''kleriki'' (or, alternatively, ''cleriki'') meaning " seminarian." This is all in keeping with Eastern Orthodox concepts of clergy, which still include those who have not yet received, or do not plan to receive, the diaconate.

A priesthood is a body of priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

s, shaman

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a Spirit world (Spiritualism), spirit world through Altered state of consciousness, altered states of consciousness, such as tranc ...

s, or oracles who have special religious authority or function. The term priest is derived from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning a ...

(πρεσβύτερος, ''presbýteros'', elder or senior), but is often used in the sense of sacerdos in particular, i.e., for clergy performing ritual

A ritual is a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, actions, or objects, performed according to a set sequence. Rituals may be prescribed by the traditions of a community, including a religious community. Rituals are characterized, b ...

within the sphere of the sacred

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or godd ...

or numinous communicating with the gods on behalf of the community.

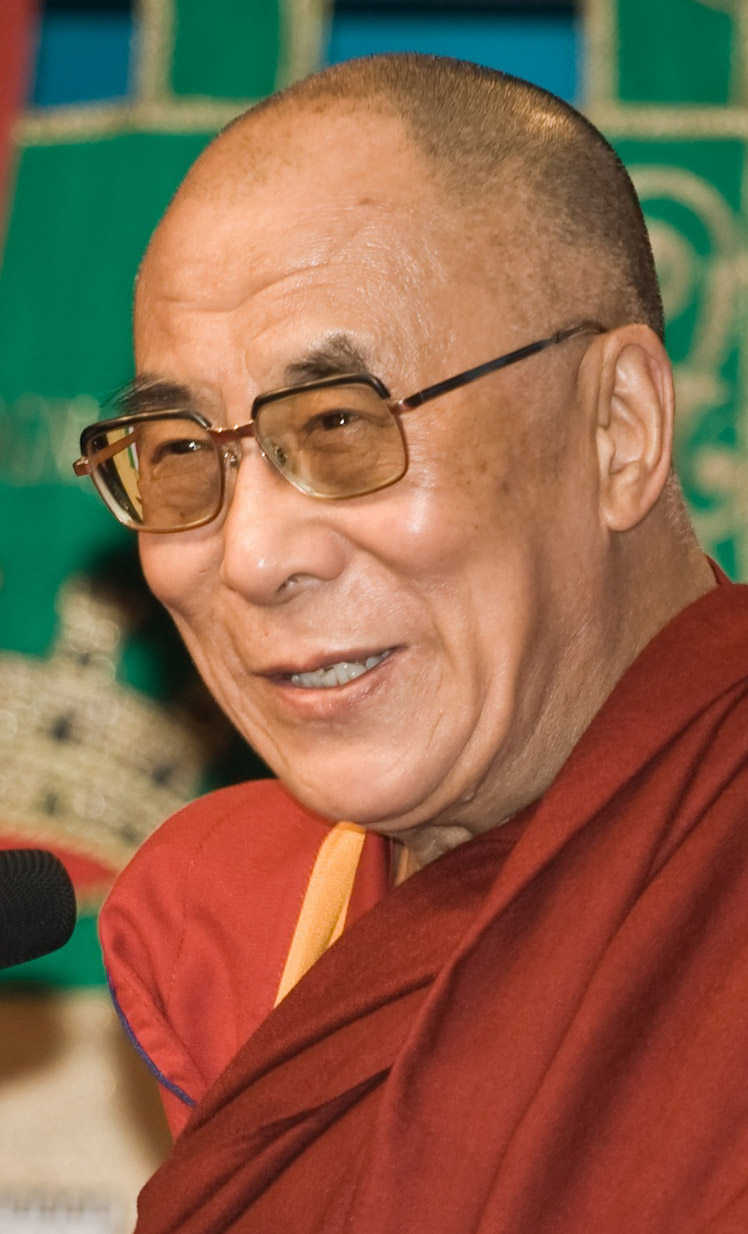

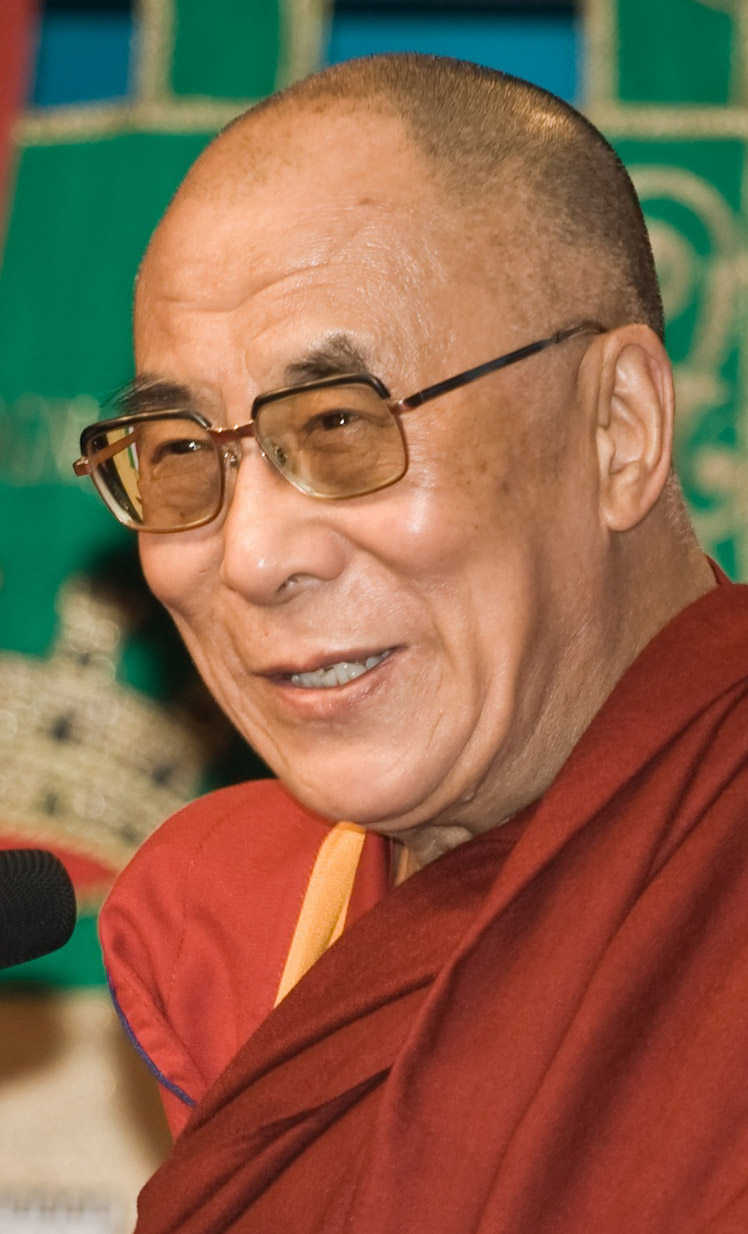

Buddhism

Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

clergy are often collectively referred to as the Sangha, and consist of various orders of male and female monks (originally called bhikshus and bhikshunis respectively). This diversity of monastic orders and styles was originally one community founded by Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in ...

during the 5th century BC living under a common set of rules (called the Vinaya). According to scriptural records, these celibate monks and nuns in the time of the Buddha lived an austere life of meditation, living as wandering beggars for nine months out of the year and remaining in retreat during the rainy season (although such a unified condition of Pre-sectarian Buddhism is questioned by some scholars). However, as Buddhism spread geographically over time – encountering different cultures, responding to new social, political, and physical environments – this single form of Buddhist monasticism diversified. The interaction between Buddhism and Tibetan Bon led to a uniquely Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism (also referred to as Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Lamaism, Lamaistic Buddhism, Himalayan Buddhism, and Northern Buddhism) is the form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and Bhutan, where it is the dominant religion. It is also in maj ...

, within which various sects, based upon certain teacher-student lineages arose. Similarly, the interaction between Indian Buddhist monks (particularly of the Southern Madhyamika School) and Chinese Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

and Taoist monks from c200-c900AD produced the distinctive Ch'an Buddhism. Ch'an, like the Tibetan style, further diversified into various sects based upon the transmission style of certain teachers (one of the most well known being the 'rapid enlightenment' style of Linji Yixuan), as well as in response to particular political developments such as the An Lushan Rebellion and the Buddhist persecutions of Emperor Wuzong. In these ways, manual labour was introduced to a practice where monks originally survived on alms; layers of garments were added where originally a single thin robe sufficed; etc. This adaptation of form and roles of Buddhist monastic practice continued after the transmission to Japan. For example, monks took on administrative functions for the Emperor in particular secular communities (registering births, marriages, deaths), thereby creating Buddhist 'priests'. Again, in response to various historic attempts to suppress Buddhism (most recently during the Meiji Era), the practice of celibacy was relaxed and Japanese monks allowed to marry. This form was then transmitted to Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republi ...

, during later Japanese occupation, where celibate and non-celibate monks today exist in the same sects. (Similar patterns can also be observed in Tibet during various historic periods multiple forms of monasticism have co-existed such as " ngagpa" lamas, and times at which celibacy was relaxed). As these varied styles of Buddhist monasticism are transmitted to Western cultures, still more new forms are being created.

In general, the Mahayana

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing bra ...

schools of Buddhism tend to be more culturally adaptive and innovative with forms, while Theravada

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

schools (the form generally practised in Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

, Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John C. Wells, Joh ...

, Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

) tend to take a much more conservative view of monastic life, and continue to observe precepts that forbid monks from touching women or working in certain secular roles. This broad difference in approach led to a major schism among Buddhist monastics in about the 4th century BCE, creating the Early Buddhist Schools

The early Buddhist schools are those schools into which the Buddhist monastic saṅgha split early in the history of Buddhism. The divisions were originally due to differences in Vinaya and later also due to doctrinal differences and geograp ...

.

While female monastic ('' bhikkhuni'') lineages existed in most Buddhist countries at one time, the Theravada

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

lineages of Southeast Asia died out during the 14th-15th Century AD. As there is some debate about whether the bhikkhuni lineage (in the more expansive Vinaya forms) was transmitted to Tibet, the status and future of female Buddhist clergy in this tradition is sometimes disputed by strict adherents to the Theravadan style. Some Mahayana sects, notably in the United States (such as San Francisco Zen Center) are working to reconstruct the female branches of what they consider a common, interwoven lineage.

The diversity of Buddhist traditions makes it difficult to generalize about Buddhist clergy. In the United States, Pure Land

A pure land is the celestial realm of a buddha or bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism. The term "pure land" is particular to East Asian Buddhism () and related traditions; in Sanskrit the equivalent concept is called a buddha-field (Sanskrit ). T ...

priests of the Japanese diaspora serve a role very similar to Protestant ministers of the Christian tradition. Meanwhile, reclusive Theravada forest monks in Thailand live a life devoted to meditation and the practice of austerities in small communities in rural Thailand- a very different life from even their city-dwelling counterparts, who may be involved primarily in teaching, the study of scripture, and the administration of the nationally organized (and government sponsored) Sangha. In the Zen traditions of China, Korea and Japan, manual labor is an important part of religious discipline; meanwhile, in the Theravada tradition, prohibitions against monks working as laborers and farmers continue to be generally observed.

Currently in North America, there are both celibate and non-celibate clergy in a variety of Buddhist traditions from around the world. In some cases they are forest dwelling monks of the Theravada tradition and in other cases they are married clergy of a Japanese Zen lineage and may work a secular job in addition to their role in the Buddhist community. There is also a growing realization that traditional training in ritual and meditation as well as philosophy may not be sufficient to meet the needs and expectations of American lay people. Some communities have begun exploring the need for training in counseling skills as well. Along these lines, at least two fully accredited Master of Divinity programs are currently available: one at Naropa University in Boulder, CO and one at the University of the West in Rosemead, CA.

Titles for Buddhist clergy include:

* Bhikkhu/ Bhikṣu and Bhikkhuṇī/ Bhikṣuṇī

* Sāmaṇera/ Śrāmaṇera and Sāmaṇerī/ Śrāmaṇerī or Śrāmaṇerikā

In Theravada:

* Acharya

* Ajahn

* Anagarika

* Ayya

* Bhante

* Dasa sil mata

* Luang Por

* Maechi or Mae chee

* Phra

* Sayadaw

* Sikkhamānā

* Thilashin

In Mahayana:

* Rōshi

* Zen master

In Vajrayana:

* Ayya

* Geshe

* Guru

Guru ( sa, गुरु, IAST: ''guru;'' Pali'': garu'') is a Sanskrit term for a "mentor, guide, expert, or master" of certain knowledge or field. In pan-Indian traditions, a guru is more than a teacher: traditionally, the guru is a reverentia ...

* Karmapa

* Lama

** Dalai Lama

** Panchen Lama

* Rinpoche/ Rimpoche

* Tertön

* Tulku

A ''tulku'' (, also ''tülku'', ''trulku'') is a reincarnate custodian of a specific lineage of teachings in Tibetan Buddhism who is given empowerments and trained from a young age by students of his or her predecessor.

High-profile examples o ...

Christianity

In general, Christian clergy areordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform var ...

; that is, they are set apart for specific ministry in religious rites. Others who have definite roles in worship but who are not ordained (e.g. laypeople acting as acolytes

An acolyte is an assistant or follower assisting the celebrant in a religious service or procession. In many Christian denominations, an acolyte is anyone performing ceremonial duties such as lighting altar candles. In others, the term is used f ...

) are generally not considered clergy, even though they may require some sort of official approval to exercise these ministries.

Types of clerics are distinguished from offices, even when the latter are commonly or exclusively occupied by clerics. A Roman Catholic cardinal, for instance, is almost without exception a cleric, but a cardinal is not a type of cleric. An archbishop is not a distinct type of cleric, but is simply a bishop who occupies a particular position with special authority. Conversely, a youth minister at a parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

may or may not be a cleric. Different churches have different systems of clergy, though churches with similar polity

A polity is an identifiable political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources. A polity can be any other group of p ...

have similar systems.

Anglicanism

In Anglicanism, clergy consist of the orders of

In Anglicanism, clergy consist of the orders of deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

s, priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

s (presbyters) and bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

s in ascending order of seniority. '' Canon'', ''archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denominations, above that of m ...

'', '' archbishop'' and the like are specific positions within these orders. Bishops are typically overseers, presiding over a diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

composed of many parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

es, with an archbishop presiding over a province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outsi ...

in most , which is a group of dioceses. A parish (generally a single church) is looked after by one or more priests, although one priest may be responsible for several parishes. New clergy are first ordained as deacons. Those seeking to become priests are usually ordained to the priesthood around a year later. Since the 1960s some Anglican churches have reinstituted the permanent diaconate, in addition to the transitional diaconate, as a ministry focused on bridges the church and the world, especially ministry to those on the margins of society.

For a short period of history before the ordination of women as deacons, priests and bishops began within Anglicanism, women could be deaconesses. Although they were usually considered having a ministry distinct from deacons they often had similar ministerial responsibilities.

In Anglicanism all clergy are permitted to marry. In most national churches women may become deacons or priests, but while fifteen out of 38 national churches allow for the consecration of women as bishops, only five have ordained any. Celebration of the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

is reserved for priests and bishops.

National Anglican churches are presided over by one or more primates or metropolitans (archbishops or presiding bishops). The senior archbishop of the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and oth ...

is the Archbishop of Canterbury, who acts as leader of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

and 'first among equals' of the primates of all Anglican churches.

Being a deacon, priest or bishop is considered a function of the person and not a job. When priests retire they are still priests even if they no longer have any active ministry. However, they only hold the basic rank after retirement. Thus a retired archbishop can only be considered a bishop (though it is possible to refer to "Bishop John Smith, the former Archbishop of York"), a canon or archdeacon is a priest on retirement and does not hold any additional honorifics.

For the forms of address for Anglican clergy, see Forms of address in the United Kingdom.

Charles Wesley Leffingwell

Charles Wesley Leffingwell (December 5, 1840 – October 10, 1928) was an American author, educator, and Episcopal priest.

Biography

Charles Wesley Leffingwell was born in Ellington, Connecticut. He was a descendant of Thomas Leffin ...

, Episcopal priest

Baptist

TheBaptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christianity, Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe ...

tradition only recognizes two ordained positions in the church as being the elders (pastors) and deacons as outlined in the third chapter of I Timothy in the Bible.

Catholic Church

Ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform var ...

clergy in the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

are either deacons, priests, or bishops belonging to the diaconate, the presbyterate, or the episcopate, respectively. Among bishops, some are metropolitans, archbishops, or patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and in ce ...

s. The pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

is the bishop of Rome

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop i ...

, the supreme and universal hierarch of the Church, and his authorization is now required for the ordination of all Roman Catholic bishops. With rare exceptions, cardinals are bishops, although it was not always so; formerly, some cardinals were people who had received clerical tonsure, but not Holy Orders. Secular clergy are ministers, such as deacons and priests, who do not belong to a religious institute and live in the world at large, rather than a religious institute ( ''saeculum''). The Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

supports the activity of its clergy by the Congregation for the Clergy, a dicastery of Roman curia. Canon Law indicates (canon 207) that " divine institution, there are among the Christian faithful in the Church sacred ministers who in law are also called clerics; the other members of the Christian faithful are called lay persons". This distinction of a separate ministry was formed in the early times of Christianity; one early source reflecting this distinction, with the three ranks or orders of

bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

, priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

and deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

, is the writings of Saint Ignatius of Antioch.

Holy Orders is one of the Seven Sacraments, enumerated at the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described ...

, that the Magisterium considers to be of divine institution. In the Catholic Church, only men are permitted to be clerics.

In the Latin Church

, native_name_lang = la

, image = San Giovanni in Laterano - Rome.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt = Façade of the Archbasilica of St. John in Lateran

, caption = Archbasilica of Saint Jo ...

before 1972, tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

admitted someone to the clerical state, after which he could receive the four minor orders (ostiary, lectorate, order of exorcists, order of acolytes) and then the major orders of subdiaconate

Subdeacon (or sub-deacon) is a minor order or ministry for men in various branches of Christianity. The subdeacon has a specific liturgical role and is placed between the acolyte (or reader) and the deacon in the order of precedence.

Subdeacons in ...

, diaconate, presbyterate, and finally the episcopate, which according to Roman Catholic doctrine is "the fullness of Holy Orders". Since 1972 the minor orders and the subdiaconate have been replaced by lay ministries and clerical tonsure no longer takes place, except in some Traditionalist Catholic groups, and the clerical state is acquired, even in those groups, by Holy Orders. In the Latin Church the initial level of the three ranks of Holy Orders is that of the diaconate. In addition to these three orders of clerics, some Eastern Catholic

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous (''sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

, or "Uniate", Churches have what are called "minor clerics".

Members of institutes of consecrated life and societies of apostolic life are clerics only if they have received Holy Orders. Thus, unordained monks, friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the o ...

s, nuns, and religious brothers and sisters are not part of the clergy.

The Code of Canon Law and the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches prescribe that every cleric must be enrolled or " incardinated" in a diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

or its equivalent (an apostolic vicariate, territorial abbey, personal prelature, etc.) or in a religious institute

A religious institute is a type of institute of consecrated life in the Catholic Church whose members take religious vows and lead a life in community with fellow members. Religious institutes are one of the two types of institutes of consecra ...

, society of apostolic life or secular institute. The need for this requirement arose because of the trouble caused from the earliest years of the Church by unattached or vagrant clergy subject to no ecclesiastical authority and often causing scandal wherever they went.

Current canon law prescribes that to be ordained a priest, an education is required of two years of philosophy and four of theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

, including study of dogmatic and moral theology, the Holy Scriptures, and canon law have to be studied within a seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy ...

or an ecclesiastical faculty at a university.

Clerical celibacy is a requirement for almost all clergy in the predominant Latin Church, with the exception of deacons who do not intend to become priests. Exceptions are sometimes admitted for ordination to transitional diaconate and priesthood on a case-by-case basis for married clergymen of other churches or communities who become Catholics, but consecration of already married men as bishops is excluded in both the Latin and Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous ('' sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

(see personal ordinariate). Clerical marriage is not allowed and therefore, if those for whom in some particular Church

In metaphysics, particulars or individuals are usually contrasted with universals. Universals concern features that can be exemplified by various different particulars. Particulars are often seen as concrete, spatiotemporal entities as opposed to ...

celibacy is optional (such as permanent deacons in the Latin Church) wish to marry, they must do so before ordination. Eastern Catholic Churches while allowing married men to be ordained, do not allow clerical marriage after ordination: their parish priest

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

s are often married, but must marry before being ordained to the priesthood. Eastern Catholic Churches

The Eastern Catholic Churches or Oriental Catholic Churches, also called the Eastern-Rite Catholic Churches, Eastern Rite Catholicism, or simply the Eastern Churches, are 23 Eastern Christian autonomous ('' sui iuris'') particular churches of ...

require celibacy only for bishops.

Eastern Orthodoxy

The

The Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops vi ...

has three ranks of holy orders: bishop, priest, and deacon. These are the same offices identified in the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

and found in the Early Church, as testified by the writings of the Holy Fathers. Each of these ranks is ordained through the Sacred Mystery (sacrament) of the laying on of hands

The laying on of hands is a religious practice. In Judaism ''semikhah'' ( he, סמיכה, "leaning f the hands) accompanies the conferring of a blessing or authority.

In Christian churches, this practice is used as both a symbolic and formal met ...

(called '' cheirotonia'') by bishops. Priests and deacons are ordained by their own diocesan bishop, while bishops are consecrated through the laying on of hands of at least three other bishops.

Within each of these three ranks there are found a number of titles. Bishops may have the title of archbishop, metropolitan

Metropolitan may refer to:

* Metropolitan area, a region consisting of a densely populated urban core and its less-populated surrounding territories

* Metropolitan borough, a form of local government district in England

* Metropolitan county, a typ ...

, and patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and in ce ...

, all of which are considered honorific

An honorific is a title that conveys esteem, courtesy, or respect for position or rank when used in addressing or referring to a person. Sometimes, the term "honorific" is used in a more specific sense to refer to an honorary academic title. It ...

s. Among the Orthodox, all bishops are considered equal, though an individual may have a place of higher or lower honor, and each has his place within the order of precedence

An order of precedence is a sequential hierarchy of nominal importance and can be applied to individuals, groups, or organizations. Most often it is used in the context of people by many organizations and governments, for very formal and state o ...

. Priests (also called presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning a ...

s) may (or may not) have the title of archpriest, protopresbyter (also called "protopriest", or "protopope"), hieromonk

A hieromonk ( el, Ἱερομόναχος, Ieromonachos; ka, მღვდელმონაზონი, tr; Slavonic: ''Ieromonakh'', ro, Ieromonah), also called a priestmonk, is a monk who is also a priest in the Eastern Orthodox Church and ...

(a monk who has been ordained to the priesthood) archimandrite

The title archimandrite ( gr, ἀρχιμανδρίτης, archimandritēs), used in Eastern Christianity, originally referred to a superior abbot ('' hegumenos'', gr, ἡγούμενος, present participle of the verb meaning "to lead") wh ...

(a senior hieromonk) and hegumen (abbot). Deacons may have the title of hierodeacon (a monk who has been ordained to the deaconate), archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denominations, above that of m ...

or protodeacon.

The lower clergy are not ordained through ''cheirotonia'' (laying on of hands) but through a blessing known as ''cheirothesia'' (setting-aside). These clerical ranks are subdeacon, reader and altar server (also known as taper-bearer). Some churches have a separate service for the blessing of a cantor.

Ordination of a bishop, priest, deacon or subdeacon must be conferred during the Divine Liturgy

Divine Liturgy ( grc-gre, Θεία Λειτουργία, Theia Leitourgia) or Holy Liturgy is the Eucharistic service of the Byzantine Rite, developed from the Antiochene Rite of Christian liturgy which is that of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of C ...

(Eucharist)—though in some churches it is permitted to ordain up through deacon during the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts—and no more than a single individual can be ordained to the same rank in any one service. Numerous members of the lower clergy may be ordained at the same service, and their blessing usually takes place during the Little Hours prior to Liturgy, or may take place as a separate service. The blessing of readers and taper-bearers is usually combined into a single service. Subdeacons are ordained during the Little Hours, but the ceremonies surrounding his blessing continue through the Divine Liturgy, specifically during the Great Entrance.

Bishops are usually drawn from the ranks of the archimandrites, and are required to be celibate; however, a non-monastic priest may be ordained to the episcopate if he no longer lives with his wife (following Canon XII of the Quinisext Council of Trullo) In contemporary usage such a non-monastic priest is usually tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

d to the monastic state, and then elevated to archimandrite, at some point prior to his consecration to the episcopacy. Although not a formal or canonical prerequisite, at present bishops are often required to have earned a university degree, typically but not necessarily in theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

.

Usual titles are ''Your Holiness'' for a patriarch (with ''Your All-Holiness'' reserved for the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch ( el, Οἰκουμενικός Πατριάρχης, translit=Oikoumenikós Patriárchēs) is the archbishop of Constantinople ( Istanbul), New Rome and ''primus inter pares'' (first among equals) among the heads of th ...

), ''Your Beatitude'' for an archbishop/metropolitan overseeing an autocephalous Church, ''Your Eminence'' for an archbishop/metropolitan generally, ''Master'' or ''Your Grace'' for a bishop and ''Father'' for priests, deacons and monks, although there are variations between the various Orthodox Churches. For instance, in Churches associated with the Greek tradition, while the Ecumenical Patriarch is addressed as "Your All-Holiness," all other Patriarchs (and archbishops/metropolitans who oversee autocephalous Churches) are addressed as "Your Beatitude."

Orthodox priests, deacons, and subdeacons must be either married or celibate (preferably monastic) prior to ordination, but may not marry after ordination. ''Re''marriage of clergy following divorce or widowhood is forbidden. Married clergy are considered as best-suited to staff parishes, as a priest with a family is thought better qualified to counsel his flock. It has been common practice in the Russian tradition for unmarried, non-monastic clergy to occupy academic posts.

Methodism

In the Methodist Churches, candidates for ordination are "licensed" to the ministry for a period of time (typically one to three years) prior to being ordained. This period typically is spent performing the duties of ministry under the guidance, supervision, and evaluation of a more senior, ordained minister. In some denominations, however, licensure is a permanent, rather than a transitional state for ministers assigned to certain specialized ministries, such as music ministry or youth ministry.Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The ...

(LDS Church) has no dedicated clergy, and is governed instead by a system of lay priesthood leaders. Locally, unpaid and part-time priesthood holders lead the church; the worldwide church is supervised by full-time general authorities, some of whom receive modest living allowances. No formal theological training is required for any position. All leaders in the church are called by revelation and the laying on of hands

The laying on of hands is a religious practice. In Judaism ''semikhah'' ( he, סמיכה, "leaning f the hands) accompanies the conferring of a blessing or authority.

In Christian churches, this practice is used as both a symbolic and formal met ...

by one who holds authority. Jesus Christ stands at the head of the church and leads the church through revelation given to the President of the Church, the First Presidency, and Twelve Apostles

In Christian theology and ecclesiology, the apostles, particularly the Twelve Apostles (also known as the Twelve Disciples or simply the Twelve), were the primary disciples of Jesus according to the New Testament. During the life and minis ...

, all of whom are recognized as prophets, seers, and revelators and have lifetime tenure. Below these men in the hierarchy are quorums of seventy, which are assigned geographically over the areas of the church. Locally, the church is divided into stakes; each stake has a president, who is assisted by two counselors and a high council. The stake is made up of several individual congregations, which are called " wards" or "branches." Wards are led by a bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

and his counselors and branches by a president and his counselors. Local leaders serve in their positions until released by their supervising authorities.

Generally, all worthy males age 12 and above receive the priesthood. Youth age 12 to 18 are ordained to the Aaronic priesthood as deacons, teachers, or priests, which authorizes them to perform certain ordinances and sacraments. Adult males are ordained to the Melchizedek priesthood, as elders, seventies, high priests, or patriarchs in that priesthood, which is concerned with spiritual leadership of the church. Although the term "clergy" is not typically used in the LDS Church, it would most appropriately apply to local bishops and stake presidents. Merely holding an office in the priesthood does not imply authority over other church members or agency to act on behalf of the entire church.

Lutheranism

There is only one order of clergy in the Lutheran church, namely the office of pastor. This is stated in the Augsburg Confession, article 14. Howeverer, for practical and historical reasons, many Lutheran churches have different roles of pastors. Some pastors are functioning as deacons, others as parish priests and yet some as bishops and even archbishops. Lutherans have no principal aversion against having a pope as the leading bishop. But the Roman Catholic view of the papacy is considered antichristian. The Book of Concord, a compendium of doctrine for the Lutheran Churches allows ordination to be called a sacrament.Reformed

The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) ordains two types ofpresbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning a ...

s or elders, teaching (pastor) and ruling (leaders of the congregation which form a council with the pastors). Teaching elders are seminary trained and ordained as a presbyter and set aside on behalf of the whole denomination to the ministry of Word and Sacrament. Ordinarily, teaching elders are installed by a presbytery as pastor of a congregation. Ruling elders, after receiving training, may be commissioned by a presbytery to serve as a pastor of a congregation, as well as preach and administer sacraments.

In Congregationalist Churches, local churches are free to hire (and often ordain) their own clergy, although the parent denominations typically maintain lists of suitable candidates seeking appointment to local church ministries and encourage local churches to consider these individuals when filling available positions.

Islam

Islam, likeJudaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

, has no clergy in the sacerdotal sense; there is no institution resembling the Christian priesthood. Islamic religious leaders do not "serve as intermediaries between mankind and God", have "process of ordination", nor "sacramental functions". They have been said to resemble more rabbis, serving as "exemplars, teachers, judges, and community leaders," providing religious rules to the pious on "even the most minor and private" matters.

The title '' mullah'' (a Persian variation of the Arabic ''maula'', "master"), commonly translated "cleric" in the West and thought to be analogous to "priest" or "rabbi", is a title of address for any educated or respected figure, not even necessarily (though frequently) religious. The title '' sheikh'' ("elder") is used similarly.

Most of the religious titles associated with Islam are scholastic or academic in nature: they recognize the holder's exemplary knowledge of the theory and practice of ''ad-dín'' (religion), and do not confer any particular spiritual or sacerdotal authority. The most general such title is ''`alim'' (pl. '' `ulamah''), or "scholar". This word describes someone engaged in advanced study of the traditional Islamic sciences ''(`ulum)'' at an Islamic university or '' madrasah jami`ah''. A scholar's opinions may be valuable to others because of his/her knowledge in religious matters; but such opinions should not generally be considered binding, infallible, or absolute, as the individual Muslim is directly responsible to God for his or her own religious beliefs and practice.

There is no sacerdotal office corresponding to the Christian priest or Jewish ''kohen'', as there is no sacrificial rite of atonement comparable to the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

or the Korban. Ritual slaughter Ritual slaughter is the practice of slaughtering livestock for meat in the context of a ritual. Ritual slaughter involves a prescribed practice of slaughtering an animal for food production purposes.

Ritual slaughter as a mandatory practice of sla ...

or '' dhabihah'', including the ''qurban'' at '' `Idu l-Ad'ha,'' may be performed by any adult Muslim who is physically able and properly trained. Professional butchers may be employed, but they are not necessary; in the case of the ''qurban'', it is especially preferable to slaughter one's own animal if possible.

Sunni

The nearest analogue among Sunni Muslims to the parish priest or pastor, or to the "pulpit

The nearest analogue among Sunni Muslims to the parish priest or pastor, or to the "pulpit rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

" of a synagogue, is called the ''imam khatib.'' This compound title is merely a common combination of two elementary offices: leader ''(imam)'' of the congregational prayer, which in most mosques is performed at the times of all daily prayers; and preacher ''(khatib)'' of the sermon or ''khutba'' of the obligatory congregational prayer at midday every Friday. Although either duty can be performed by anyone who is regarded as qualified by the congregation, at most well-established mosques ''imam khatib'' is a permanent part-time or full-time position. He may be elected by the local community, or appointed by an outside authority – e.g., the national government, or the waqf

A waqf ( ar, وَقْف; ), also known as hubous () or ''mortmain'' property is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitabl ...

that sustains the mosque. There is no ordination as such; the only requirement for appointment as an ''imam khatib'' is recognition as someone of sufficient learning and virtue to perform both duties on a regular basis, and to instruct the congregation in the basics of Islam.

The title '' hafiz'' (lit. "preserver") is awarded to one who has memorized the entire Qur'an, often by attending a special course for the purpose; the ''imam khatib'' of a mosque is frequently (though not always) a ''hafiz.''

There are several specialist offices pertaining to the study and administration of Islamic law or '' shari`ah.'' A scholar with a specialty in ''fiqh'' or jurisprudence is known as a '' faqih''. A ''qadi

A qāḍī ( ar, قاضي, Qāḍī; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a ''sharīʿa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minor ...

'' is a judge in an Islamic court. A '' mufti'' is a scholar who has completed an advanced course of study which qualifies him to issue judicial opinions or '' fatawah''.

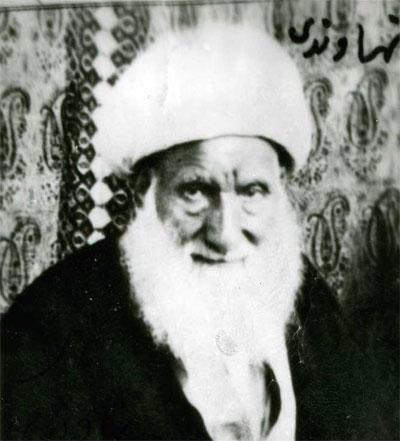

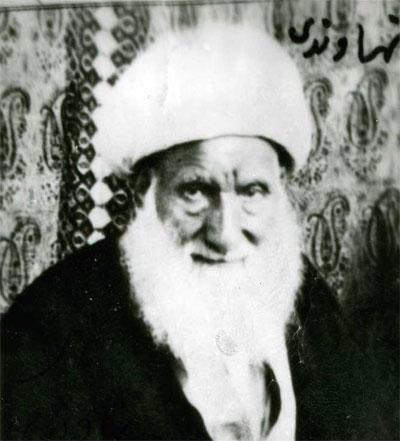

Shia

In modern

In modern Shia Islam

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet

Prophets in Islam ( ar, الأنبياء في الإسلام, translit=al-ʾAnbiyāʾ fī al-ʾIslām) are individuals in Islam who are ...

, scholars play a more prominent role in the daily lives of Muslims than in Sunni Islam; and there is a hierarchy of higher titles of scholastic authority, such as ''Ayatollah

Ayatollah ( ; fa, آیتالله, āyatollāh) is an Title of honor, honorific title for high-ranking Twelver Shia clergy in Iran and Iraq that came into widespread usage in the 20th century.

Etymology

The title is originally derived from ...

''. Since around the mid-19th century, a more complex title has been used in Twelver Shi`ism, namely ''marjaʿ at-taqlid''. '' Marjaʿ'' (pl. ''marajiʿ'') means "source", and ''taqlid'' refers to religious emulation or imitation. Lay Shi`ah must identify a specific ''marjaʿ'' whom they emulate, according to his legal opinions ''(fatawah)'' or other writings. On several occasions, the ''Marjaʿiyyat'' (community of all ''marajiʿ'') has been limited to a single individual, in which case his rulings have been applicable to all those living in the Twelver Shi'ah world. Of broader importance has been the role of the ''mujtahid'', a cleric of superior knowledge who has the authority to perform '' ijtihad'' (independent judgment). Mujtahids are few in number, but it is from their ranks that the ''marajiʿ at-taqlid'' are drawn.

Sufism

The spiritual guidance function known in many Christian denominations as "pastoral care" is fulfilled for many Muslims by a ''murshid'' ("guide"), a master of the spiritual sciences and disciplines known as ''tasawuf'' or Sufism. Sufi guides are commonly styled ''Shaikh'' in both speaking and writing; in North Africa they are sometimes called ''marabout

A marabout ( ar, مُرابِط, murābiṭ, lit=one who is attached/garrisoned) is a Muslim religious leader and teacher who historically had the function of a chaplain serving as a part of an Islamic army, notably in North Africa and the Saha ...

s''. They are traditionally appointed by their predecessors, in an unbroken teaching lineage reaching back to Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

. (The lineal succession of guides bears a superficial similarity to Christian ordination and apostolic succession, or to Buddhist dharma transmission; but a Sufi guide is regarded primarily as a specialized teacher and Islam denies the existence of an earthly hierarchy among believers.)

Muslims who wish to learn Sufism dedicate themselves to a ''murshids guidance by taking an oath called a '' bai'ah''. The aspirant is then known as a ''murid'' ("disciple" or "follower"). A ''murid'' who takes on special disciplines under the guide's instruction, ranging from an intensive spiritual retreat to voluntary poverty and homelessness, is sometimes known as a dervish.

During the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

, it was common for scholars to attain recognized mastery of both the "exterior sciences" ''(`ulum az-zahir)'' of the madrasahs as well as the "interior sciences" ''(`ulum al-batin)'' of Sufism. Al-Ghazali and Rumi are two notable examples.

Ahmadiyya

The highest office an Ahmadi can hold is that of ''Khalifatu l-Masih''. Such a person may appoint amirs who manage regional areas. The consultative body for Ahmadiyya is called the ''Majlis-i-Shura'', which ranks second in importance to the ''Khalifatu l-Masih''. However, the Ahmadiyya community is declared as non-Muslims by many mainstream Muslims and they reject the messianic claims of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad.Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonian ...

does not have clergy as such, although according to the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the s ...

there is a tribe of priests known as the Kohanim who were leaders of the religion up to the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 AD when most Sadducees were wiped out; each member of the tribe, a Kohen had priestly duties, many of which centered around the sacrificial duties, atonement and blessings of the Israelite nation. Today, Jewish Kohanim know their status by family tradition, and still offer the priestly blessing during certain services in the synagogue and perform the '' Pidyon haben'' (redemption of the first-born son) ceremony.

Since the time of the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, the religious leaders of Judaism have often been rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

s, who are technically scholars in Jewish law empowered to act as judges in a rabbinical court. All types of Judaism except Orthodox Judaism allow women as well as men to be ordained as rabbis and cantors. The leadership of a Jewish congregation is, in fact, in the hands of the laity: the president of a synagogue is its actual leader and any adult male Jew (or adult Jew in non-traditional congregations) can lead prayer services. The rabbi is not an occupation found in the Torah; the first time this word is mentioned is in the Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Tora ...

. The modern form of the rabbi developed in the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

ic era. Rabbis are given authority to make interpretations of Jewish law and custom. Traditionally, a man obtains one of three levels of Semicha

Semikhah ( he, סמיכה) is the traditional Jewish name for rabbinic ordination.

The original ''semikhah'' was the formal "transmission of authority" from Moses through the generations. This form of ''semikhah'' ceased between 360 and 425 ...

(rabbinic ordination) after the completion of an arduous learning program in Torah, Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Mishnah and Talmud, Midrash

''Midrash'' (;"midrash"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

, Jewish ethics and lore, the codes of Jewish law and responsa, ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

and philosophy.

Since the early medieval era an additional communal role, the '' Hazzan'' (cantor) has existed as well. Cantors have sometimes been the only functionaries of a synagogue, empowered to undertake religio-civil functions like witnessing marriages. Cantors do provide leadership of actual services, primarily because of their training and expertise in the music and prayer rituals pertaining to them, rather than because of any spiritual or "sacramental" distinction between them and the laity. Cantors as much as rabbis have been recognized by civil authorities in the United States as clergy for legal purposes, mostly for awarding education degrees and their ability to perform weddings, and certify births and deaths.

Additionally, Jewish authorities license '' mohels'', people specially trained by experts in Jewish law and usually also by medical professionals to perform the ritual of circumcision. Traditional Orthodox Judaism does not license women as mohels, but other types of Judaism do. They are appropriately called ''mohelot'' (pl. of ''mohelet,'' f. of mohel). As the ''j., the Jewish News Weekly of Northern California'', states, "...there is no halachic prescription against female mohels, utnone exist in the Orthodox world, where the preference is that the task be undertaken by a Jewish man.". In many places, mohels are also licensed by civil authorities, as circumcision is technically a surgical procedure. Kohanim, who must avoid contact with dead human body parts (such as the removed foreskin) for ritual purity, cannot act as mohels, but some mohels are also either rabbis or cantors.

Another licensed cleric in Judaism is the '' shochet'', who are trained and licensed by religious authorities for kosher slaughter according to ritual law. A Kohen may be a shochet. Most shochetim are ordained rabbis.

Then there is the '' mashgiach/mashgicha''. ''Mashgichim'' are observant Jews who supervise the '' kashrut'' status of a kosher establishment. The ''mashgichim'' must know the Torah laws of ''kashrut'', and how they apply in the environment they are supervising. Obviously, this can vary. In many instances, the ''mashgiach''/''mashgicha'' is a rabbi. This helps, since rabbinical students learn the laws of kosher as part of their syllabus. However, not all ''mashgichim'' are rabbis, and not all rabbis are qualified to be ''mashgichim''.

Since the early medieval era an additional communal role, the '' Hazzan'' (cantor) has existed as well. Cantors have sometimes been the only functionaries of a synagogue, empowered to undertake religio-civil functions like witnessing marriages. Cantors do provide leadership of actual services, primarily because of their training and expertise in the music and prayer rituals pertaining to them, rather than because of any spiritual or "sacramental" distinction between them and the laity. Cantors as much as rabbis have been recognized by civil authorities in the United States as clergy for legal purposes, mostly for awarding education degrees and their ability to perform weddings, and certify births and deaths.

Additionally, Jewish authorities license '' mohels'', people specially trained by experts in Jewish law and usually also by medical professionals to perform the ritual of circumcision. Traditional Orthodox Judaism does not license women as mohels, but other types of Judaism do. They are appropriately called ''mohelot'' (pl. of ''mohelet,'' f. of mohel). As the ''j., the Jewish News Weekly of Northern California'', states, "...there is no halachic prescription against female mohels, utnone exist in the Orthodox world, where the preference is that the task be undertaken by a Jewish man.". In many places, mohels are also licensed by civil authorities, as circumcision is technically a surgical procedure. Kohanim, who must avoid contact with dead human body parts (such as the removed foreskin) for ritual purity, cannot act as mohels, but some mohels are also either rabbis or cantors.

Another licensed cleric in Judaism is the '' shochet'', who are trained and licensed by religious authorities for kosher slaughter according to ritual law. A Kohen may be a shochet. Most shochetim are ordained rabbis.

Then there is the '' mashgiach/mashgicha''. ''Mashgichim'' are observant Jews who supervise the '' kashrut'' status of a kosher establishment. The ''mashgichim'' must know the Torah laws of ''kashrut'', and how they apply in the environment they are supervising. Obviously, this can vary. In many instances, the ''mashgiach''/''mashgicha'' is a rabbi. This helps, since rabbinical students learn the laws of kosher as part of their syllabus. However, not all ''mashgichim'' are rabbis, and not all rabbis are qualified to be ''mashgichim''.

Orthodox Judaism

In contemporary Orthodox Judaism, women are usually forbidden from becoming rabbis or cantors. Most Orthodox rabbinical seminaries or yeshivas also require dedication of many years to education, but few require a formal degree from a civil education institution that often define Christian clergy. Training is often focused on Jewish law, and some Orthodox Yeshivas forbid secular education. InHasidic Judaism