The Rashidun army () was the core of the

Rashidun Caliphate's armed forces during the

early Muslim conquests in the 7th century. The army is reported to have maintained a high level of discipline, strategic prowess and organization, granting them successive victories in their various campaigns.

In its time, the Rashidun army was a very powerful and effective force. The three most successful generals of the army were

Khalid ibn al-Walid, who

conquered Persian Mesopotamia and the

Roman Levant,

Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah, who also conquered parts of the Roman Levant, and

Amr ibn al-As, who

conquered Roman Egypt. The army was a key component in the Rashidun Caliphate's territorial expansion and served as a medium for the early spread of

Islam into the territories it conquered.

Historical overview

According to Tarikh at Tabari, the nucleus of the early caliphate forces were formed from the Green Division (al-Katibah al-Khadra), a unit that consisted of early converts from

Muhajirun and

Ansar that marched on to

conquer Mecca.

Ridda wars

Upon Muhammad's death, the Muslim community was unprepared for the loss of its leader and many experienced a profound shock. Umar was particularly affected, instead declaring that Muhammad had gone to consult with God and would soon return, threatening anyone who would say that Muhammad was dead.

Abu Bakr, having returned to Medina, calmed Umar by showing him Muhammad's body, convincing him of his death. He then addressed those who had gathered at the mosque, saying, "If anyone worships Muhammad, Muhammad is dead. If anyone worships God, God is alive, immortal", thus putting an end to any idolising impulse in the population. He then concluded with a verse from the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

: "Muhammad is no more than an apostle, and many apostles have passed away before him."

[

Troubles emerged soon after Abu Bakr's succession, with several Arab tribes launching revolts, threatening the unity and stability of the new community and state. These insurgencies and the caliphate's responses to them are collectively referred to as the Ridda wars ("Wars of Apostasy").

The opposition movements came in two forms. One type challenged the political power of the nascent caliphate as well as the religious authority of Islam with the acclamation of rival ideologies, headed by political leaders who claimed the mantle of prophethood in the manner that Muhammad had done. These rebellions include:

* that of the Banu Asad ibn Khuzaymah headed by Tulayha ibn Khuwaylid

* that of the Banu Hanifa headed by Musaylimah

* those from among the Banu Taghlib and the Bani Tamim headed by Sajah

* that of the Al-Ansi headed by Al-Aswad Al-Ansi

* Omani rebels led by Laqeet bin Malik

These leaders are all denounced in Islamic histories as "false prophets".

The second form of opposition movement was more strictly political in character. Some of the revolts of this type took the form of tax rebellions in Najd among tribes such as the Banu Fazara and Banu Tamim. Other dissenters, while initially allied with the Muslims, used Muhammad's death as an opportunity to attempt to restrict the growth of the new Islamic state. They include some of the Rabīʿa in Bahrayn, the Azd in ]Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

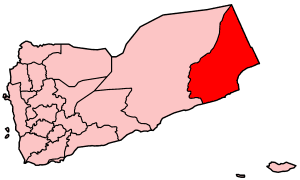

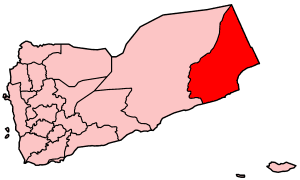

, as well as among the Kinda and Khawlan in Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

.

At their heart, the Ridda movements were challenges to the political and religious supremacy of the Islamic state. Through his success in suppressing the insurrections, Abu Bakr had in effect continued the political consolidation which had begun under Muhammad's leadership with relatively little interruption. By the wars' end, he had established Islamic hegemony over the entire Arabian Peninsula.

Military expansions

After the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah

The Treaty of Hudaybiyyah ( ar, صُلح ٱلْحُدَيْبِيَّة, Ṣulḥ Al-Ḥudaybiyyah) was an event that took place during the time of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was a pivotal treaty between Muhammad, representing the state o ...

in 628, Islamic tradition holds that Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

sent many letters to the princes, kings, and chiefs of the various tribes and kingdoms of the time, exhorting them to convert to Islam and bow to the order of God. These letters were carried by ambassadors to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

, Byzantium, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the Er ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

, Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

, and Hira (Iraq) on the same day.Khosrau II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king ( shah) of Iran, ruling ...

inviting him to convert:

There are differing accounts of the reaction of Khosrau II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king ( shah) of Iran, ruling ...

.

By span from the ascensions of Abu Bakar as caliph until his death, the Rashidun Caliphate expanded steadily; within the span of 24 years, a vast territory was conquered comprising Mesopotamia, the Levant, parts of Anatolia, and most of the Sasanian Empire.

Expansions during Abu Bakr's reign

Arab Muslims first attacked Sassanid territory in 633, when Khalid ibn al-Walid invaded Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

(then known as the Sassanid province of '' Asōristān''; roughly corresponding to modern-day Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

), which was the political and economic centre of the Sassanid state.

Expansions during Umar's reign

Abu Bakr was aware of Umar's power and ability to succeed him. His was perhaps one of the smoothest transitions of power from one authority to another in the Muslim lands.

Before his death, Abu Bakr called Uthman to write his will in which he declared Umar his successor. In his will he instructed Umar to continue the conquests on the Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

i and Syrian fronts.

Following the transfer of Khalid to the Byzantine front in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximation, approximate historical geography, historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology an ...

, the Muslims eventually lost their holdings to Sassanid counterattacks. The second Muslim invasion began in 636, under Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, when a key victory at the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah led to the permanent end of Sassanid control west of modern-day Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

. For the next six years, the Zagros Mountains, a natural barrier, marked the border between the Rashidun Caliphate and the Sassanid Empire. In 642, Umar ordered a full-scale invasion of Persia by the Rashidun army, which led to the complete conquest of the Sassanid Empire by 651. Directing from Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

, a few thousand kilometres away, Umar's quick conquest of Persia in a series of well-coordinated, multi-pronged attacks became his greatest triumph, contributing to his reputation as a great military and political strategist.

The military conquests were partially terminated between 638 and 639 during the years of great famine in Arabia and plague in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximation, approximate historical geography, historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology an ...

. During his reign the Levant, Egypt, Cyrenaica, Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

, Fezzan, eastern Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The r ...

, almost the whole of the Sassanid Persian Empire including Bactria, Persia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

and Makran were annexed to the Rashidun Caliphate. Prior to his death in 644, Umar had ceased all military expeditions apparently to consolidate his rule in recently conquered Roman Egypt and the newly conquered Sassanid Empire (642–644). At his death in November 644, his rule extended from present day Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Su ...

in the west to the Indus river in the east and the Oxus river in the north.

Historians estimate more than 4,050 cities were conquered during the reign of Umar.

Expansions during Uthman's reign

In 644, prior to the complete annexation of Persia by the Arab Muslims, Umar was assassinated by Abu Lu'lu'a Firuz

Abū Luʾluʾa Fīrūz ( ar, أبو لؤلؤة فيروز; from ), also known as Bābā Shujāʿ al-Dīn ( ar, بابا شجاع الدين, label=none), was a Sassanid Persian slave known for having assassinated Umar ibn al-Khattab (), the se ...

, a Persian craftsman who was captured in battle and brought to Arabia as a slave.

Uthman ibn Affan, the third caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

, was chosen by a committee in Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

, in northwestern Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

, in. The second caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab, was stabbed by Abu Lu'lu'a Firuz

Abū Luʾluʾa Fīrūz ( ar, أبو لؤلؤة فيروز; from ), also known as Bābā Shujāʿ al-Dīn ( ar, بابا شجاع الدين, label=none), was a Sassanid Persian slave known for having assassinated Umar ibn al-Khattab (), the se ...

, a Persian slave. On his deathbed, Umar tasked a committee of six with choosing the next caliph among themselves. These six men from the Quraysh, all early companions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

, were

* Ali ibn Abi Talib

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, عَلِيّ بْن أَبِي طَالِب; 600 – 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 – 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

* Abd al-Rahman ibn Awf

* Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas

* Uthman ibn Affan

* Zubayr ibn al-Awwam

* Talhah ibn Ubaydullah

Where they unanimously selected Uthman as the successor. During his rule, Uthman's military style was less centralised as he delegated much military authority to his trusted kinsmen—e.g., Abdullah ibn Aamir, Muawiyah I and Abdullāh ibn Sa'ad ibn Abī as-Sarâḥ—unlike Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphat ...

's more centralized policy. Consequently, this more independent policy allowed more expansion until Sindh, in modern Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, which had not been touched during the tenure of Umar.[''History of the Prophets and Kings'' (''Tarikh al-Tabari'') Vol. 04 ''The Ancient Kingdoms'': pg:183.]

Muawiyah I had been appointed the governor of Syria by Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphat ...

in 639 to stop Byzantine harassment from the sea during the Arab-Byzantine Wars. He succeeded his elder brother Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan, who died in a plague, along with Abu Ubaidah ibn al-Jarrah. Now under Uthman's rule in 649, Muawiyah was allowed to establish a navy, manned by Monophysitic Christians, Copts

Copts ( cop, ⲛⲓⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ ; ar, الْقِبْط ) are a Christian ethnoreligious group indigenous to North Africa who have primarily inhabited the area of modern Egypt and Sudan since antiquity. Most ethnic Copts are ...

, and Jacobite Syrian Christian sailors and Muslim troops, which defeated the Byzantine navy at the Battle of the Masts in 655, opening up the Mediterranean.

In Hijri year 31 (c. 651), Uthman sent Abdullah ibn Zubayr and Abdullah ibn Saad to reconquer the Maghreb, where he met the army of Gregory the Patrician, Exarch of Africa and relative of Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revolt ...

, which is recorded to have numbered between 120,000 or 200,000 soldiers.Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

. Spain had first been invaded some sixty years earlier during the caliphate of Uthman. Other prominent Muslim historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

s, like Ibn Kathir, have quoted the same narration. In the description of this campaign, two of Abdullah ibn Saad's generals, Abdullah ibn Nafiah ibn Husain, and Abdullah ibn Nafi' ibn Abdul Qais, were ordered to invade the coastal areas of Spain by sea, aided by a Berber force. They succeeded in conquering the coastal areas of Al-Andalus. It is not known where the Muslim force landed, what resistance they met, and what parts of Spain they actually conquered. However, it is clear that the Muslims did conquer some portions of Spain during the caliphate of Uthman, presumably establishing colonies on its coast. On this occasion, Uthman is reported to have addressed a letter to the invading force:

Although raids by Berbers and Muslims were conducted against the Visigothic Kingdom in Spain during the late 7th century, there is no evidence that Spain was invaded nor that parts of it were conquered or settled by Muslims prior to the 711 campaign by Tariq.

Abdullah ibn Saad also achieved success in the Caliphate's first decisive naval battle against the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

, the Battle of the Masts.

To the east, Ahnaf ibn Qais, chief of Banu Tamim and a veteran commander who conquered Shustar earlier, launched a series of further military expansions by further mauling Yazdegerd III near the Oxus River in

To the east, Ahnaf ibn Qais, chief of Banu Tamim and a veteran commander who conquered Shustar earlier, launched a series of further military expansions by further mauling Yazdegerd III near the Oxus River in Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the s ...

[''The Muslim Conquest of Persia'' by A.I. Akram. Ch:17 ,][Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War, By Kaveh Farrokh, Published by Osprey Publishing, 2007 ] and later crushing a military coalition of Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Name ...

loyalists and the Hephthalite Empire in the Siege of Herat.Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

, Abdullah ibn Aamir also led a number of successful campaigns, ranging from the suppression of revolts in Fars, Kerman, Sistan, and Khorasan, to the opening of new fronts for conquest in Transoxiana and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bord ...

.

In the next year, 652 AD, Futh Al-Buldan of Baladhuri writes that Balochistan was re-conquered during the campaign against the revolt in Kermān, under the command of Majasha ibn Mas'ud. It was the first time that western Balochistan had come directly under the laws of the Caliphate and it paid an agricultural tribute.

The military campaigns under Uthman's rule were generally successful. Regarding the fate of their adversaries, unlike the Sasanian Persians, the Byzantines, after losing Syria, retreated back to Anatolia. As a result, they also lost Egypt to the invading Rashidun army, although the civil wars among the Muslims halted the war of conquest for many years, and this gave time for the Byzantine Empire to recover.

Transition into Umayyad caliphate

After Uthman's assassination, Ali was recognized as caliph in Medina, though his support stemmed from the Ansar and the Iraqis, while the bulk of the Quraysh was wary of his rule. The first challenge to his authority came from the Qurayshite leaders al-Zubayr and Talha. Backed by one of Muhammad's wives, A'isha, they attempted to rally support against Ali among the troops of Basra, prompting the caliph to leave for Iraq's other garrison town, Kufa, where he could better confront his challengers. Ali defeated them at the Battle of the Camel, in which al-Zubayr and Talha were slain and A'isha consequently entered self-imposed seclusion. Ali's sovereignty was thereafter recognized in Basra and Egypt and he established Kufa as the Caliphate's new capital.

Although Ali was able to replace Uthman's governors in Egypt and Iraq with relative ease, Mu'awiya had developed a solid power-base and an effective military against the Byzantines from the Arab tribes of Syria. Mu'awiya did not claim the caliphate but was determined to retain control of Syria and opposed Ali in the name of avenging his kinsman Uthman, accusing the caliph of culpability in his death. Ali and Mu'awiya fought to a stalemate at the Battle of Siffin in early 657. Ali agreed to settle the matter with Mu'awiya by arbitration. The decision to arbitrate fundamentally weakened Ali's political position as he was forced to negotiate with Mu'awiya on equal terms, while it drove a significant number of his supporters, who became known as the Kharijites, to revolt. Ali's coalition steadily disintegrated and many Iraqi tribal nobles secretly defected to Mu'awiya, while the latter's ally Amr ibn al-As ousted Ali's governor from Egypt in July 658. Ali was assassinated by a Kharijite in January 661. His son Hasan succeeded him but abdicated in return for compensation upon Mu'awiya's arrival to Iraq with his Syrian army in the summer. At that point, Mu'awiya entered Kufa and received the allegiance of the Iraqis.

Later Mu'awiya was formally recognized as caliph in Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

by his Syrian tribal allies, thus starting the long string of Umayyad dynastic rulers

Units

The first requirement to join the Rashidun caliphate army was to be Muslim. Earlier caliphs such as Abu Bakar and Umar were even stricter in terms of army recruitment as they did not allow any ex-rebels in Ridda Wars. According to Claude Cahen, this strict policy was maintained at least until the Siege of Babylon fortress in Egypt. However, other sources noted the eastern theater of conquest in Persia are more lenient for recruitment as the caliphate employed former rebels such as Tulayha and Amr ibn Ma'adi Yakrib. Tulayha even played a significant role during a raid against the Persian army during Sa'd's campaign, which was codenamed ''Yaum Armath''(يوم أرماث or "''The Day of Disorder''") by early Muslim historians. The policy of not employing ex-rebels and apostates (''Ahl ar Riddah'' according to Tabari) were retracted by 'Umar during his second half reign.

Infantry

The standing infantry lines formed the majority of the Rashidun army. They would make repeated charges and withdrawals known as ''karr wa farr'', using spears and swords combined with arrow volleys to weaken the enemies and wear them out. However, the main energy had to still be conserved for a counterattack, supported by a cavalry charge, that would make flanking or encircling movements.

Defensively, the Muslim spearman with their two and a half meter long spears would close ranks, forming a protective wall (''Tabi'a'') for archers to continue their fire. This close formation stood its ground remarkably well in the first four days of defence in the Battle of Yarmouk.

Jandora noted the merit of individual skills, bravery, and discipline of Rashidun infantry as the main reason they won battle of Yarmouk. Jandora pointed out their quality to remain steadfast even against the onslaught of Byzantine cavalry charge, or even when facing the elephant corps of Sassanid.

The standing infantry lines formed the majority of the Rashidun army. They would make repeated charges and withdrawals known as ''karr wa farr'', using spears and swords combined with arrow volleys to weaken the enemies and wear them out. However, the main energy had to still be conserved for a counterattack, supported by a cavalry charge, that would make flanking or encircling movements.

Defensively, the Muslim spearman with their two and a half meter long spears would close ranks, forming a protective wall (''Tabi'a'') for archers to continue their fire. This close formation stood its ground remarkably well in the first four days of defence in the Battle of Yarmouk.

Jandora noted the merit of individual skills, bravery, and discipline of Rashidun infantry as the main reason they won battle of Yarmouk. Jandora pointed out their quality to remain steadfast even against the onslaught of Byzantine cavalry charge, or even when facing the elephant corps of Sassanid.

Infantry horses and camels

Aside from Donner's report that each caliphate's soldiers possessed camels, Dr Lee Eysturlid noted the Diwan al Jund around 640 AD has recorded that each caliphate's soldiers already possessed horses. The camels mainly supplied from Al-Rabadha and Diriyah.

Armour

Reconstructing the military equipment of early Muslim armies is problematic relative to contemporary neighbouring armies such as Byzantium's as the visual representation of the early caliphate armaments was very limited physical material and difficult to date. However, Nicolle theorized the Muslim army used hardened leather scale or lamellar armour produced in Yemen, Iraq and along the Persian Gulf coast. Mail armour was preferred and became more common later during the conquest of neighbouring empires, often being captured as part of the booty. It was known as ''Dir,'' and was opened part-way down the chest. To avoid rusting it was polished and stored in a mixture of dust and oil.

Mail shirts were recorded already used by the Arabs before the advent of Islam. During the Battle of Uhud, Jami'at Tirmidhi recorded Zubayr ibn al-Awwam testimony that prophet Muhammad wearing two layers of mail coat. However, there is still not yet archaeological founding of Arabic armor in such time. David Nicolle are certain the prevalence of leather armour among Arabs since pre-Islamic era, due to the fact that the leather were one of important commodity which make the Meccan traders rich were leather, which correlated with the war between the Byzantine and Sassanian Empires during 6th century as there are increased demand for such military goods that Nicolle called ''“military leatherwork"''.

Helmets

Muslim headgear included gilded helmets—both pointed and rounded—similar to that of the silver helmets of the Sassanid Empire. The rounded helmet, referred to as "Baidah" ("Egg"), was a standard early Byzantine type composed of two pieces. The pointed helmet was a segmented Central Asian type known as "Tarikah". Mail armour was commonly used to protect the face and neck, either as an aventail from the helmet or as a mail coif the way it had been used by Romano-Byzantine armies since the 5th century. The face was often half covered with the tail of a turban that also served as protection against the strong desert winds.

Another type of helmet used by the Rashidun army were the Mighfars.

Swords

Sayf was a broad sword with a peculiar hooked pomel used by the Rashidun army. Early Arab chroniclers mentioned two types of swords:

* ''Saif Anith'', which was made of iron

* ''Saif Fulath'' or ''Muzakka'', which was made of steel material.

These broad swords came to Arabia through

Sayf was a broad sword with a peculiar hooked pomel used by the Rashidun army. Early Arab chroniclers mentioned two types of swords:

* ''Saif Anith'', which was made of iron

* ''Saif Fulath'' or ''Muzakka'', which was made of steel material.

These broad swords came to Arabia through Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

port during the pre-Islamic ʿĀd and Jurhum era. These Indian-made swords were forged from '' wootz'' steel. Aside from Yemen, high-quality ''Indian swords'' also introduced to pre-Islamic Arab through port of Ubulla, Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

. The Arabs in Medina during the time of Muhammad were able to manufacture Sayf swords independently. There are records that some nobles made their sword with silver materials, such as prophet Muhammad sword and Zubayr ibn al-Awwam sword used which reported by from Anas ibn Malik and Hisham are made of silver or contain inscription of silver material. However, there is no archeological trace that such sword found yet.

Curved saber or Shamshir also existed during the early years of the caliphate. This type of saber allegedly belonged to the prophet Muhammad and is now in the Topkapi Museum. David Nicolle theorized that this type of saber is probably of central Asian, Avar or Magyar origin. Nicolle theorized it reached the early Muslim Arabs through the contact with Byzantium before the 6th century.

Shields

Large wooden or wickerwork shields were in use, but most shields were made of leather. For this purpose, the hides of camels and cows were used and it would be anointed, a practice since ancient Hebrew times. During the invasion of the Levant, Byzantine soldiers extensively used elephant-hide shields, which were probably captured and used by the Rashidun army.

Spears

Long spears which were used by infantry were locally made with the reeds of the Persian Gulf coast. The reeds were similar to that of bamboo. These Arab blacksmiths manufactured infantry spears called ''al-Ramh''. There are two types of this spear:

* Arab blacksmiths used sharpened animal horns for the tip of the blade

* Usual iron which was sharpened and hammered first until it forms the blade.

During the Battle of Badr, the Prophet commanded his companions to use spears for middle-range combat. The raw material for making spears was available in Arabia.

Maces

The early caliphate army also used blunt weapon such as Mace

Mace may refer to:

Spices

* Mace (spice), a spice derived from the aril of nutmeg

* '' Achillea ageratum'', known as English mace, a flowering plant once used as a herb

Weapons

* Mace (bludgeon), a weapon with a heavy head on a solid shaft used ...

, which named ''al-Dabbus''. A round-headed, Persian style mace

Javelins

Wahshi ibn Harb, was a renowned javelineer who fought for pagan Quraish during the battle of Uhud and killed Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib with a javelin. After his conversion to Islam, he fought for the caliphate during the Battle of Yamama and personally killed apostate leader Musaylimah with a javelin throw.

Archer

Ibn al-Qayyim concludes that Caliph Umar put special emphasis regarding his soldiers to practice extensively archery as the caliph wanted to implement the archery tradition according to the teaching of prophet Muhammad to the military of Rashidun. Rashidun archers were noted for their sharpshooting skill to aim at the eyes of the enemy, such as in the Battle of al Anbar, where the Rashidun archers shooting the eyes of Sassanid catapult engineer corps, blinding hundreds of engineers and left the siege engine unused during the battle.

Rashidun archers were typically precise and power shooters, akin to Byzantine archers in the Battle of Callinicum. This powerful style allowed Rashidun archers to easily overcome Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Name ...

archers who preferred the rapid, showering Panjagan archery technique, as the former packed more punch and range than the latter during the Muslim conquest of Persia. Another particular case highlighted by Baladhuri regarding account from a grandson of the survivor of Sassanid Army who witnessed the Battle of Qadisiyya how the Sassanid arrows failed to pierce Rashidun armors or shields, while in return the arrows of Muslim archers able to penetrate mail coats and double cuirass

A cuirass (; french: cuirasse, la, coriaceus) is a piece of armour that covers the torso, formed of one or more pieces of metal or other rigid material. The word probably originates from the original material, leather, from the French '' cui ...

of Sassanid warriors. The archers of Rashidun army also recorded for their accuracy, as they can aim the eyes of Sassanid horses with their arrows during Siege of Ctesiphon.

Bows

According to an ancient arabic manuscript of archery, Bows used by people of Arabs were locally made in various parts of Arabia; the most typical were the Hijazi bows. There are three types of Hijazi bows:

* ''Qadib'' variant is basically made from single stave of wood

* ''Masnu'ah'' variant are composite bows designed from a stave or two staves divided lengthwise with four composite materials of wood, horn, glue, and sinew

* ''Mu'aqabbah'' variant are bows designed with horn of goats placed in the belly of the bow and sinew placed on the back of the bow.

Arabs were able to master the art of Bowery and use it so effectively to even matched the qualities of Byzantines and Persians made. The most famous place for manufacturing bows was Za s r in al-Sham. which became the name renowned Zed bows (al-Kanä t in al-Zas riyyah). The Muslims continued to improve the manufacturing of bows and were able at one point to manufacture sophisticated machines (''al Ma'arrah'', a large crossbow). According to Latham in his work, ''Saracen archery'', Muslim archers of early era has two types of arrows. The first were shorter darts called ''Nabl'' and ''Nushshab'', which were shot using either a crossbow or a bow equipped with arrow guide, while the second type were longer arrows which were shot with standard handbows.

Cavalry

Rashidun cavalry were highly regarded by the military rulers of early Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i Münevvere) and also commonly simplified as Madīnah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

, the theocracy and the Caliphates' successor states who gave the cavalry troopers got at least two portions of spoils and booty from the defeated enemies, while regular infantry only received only a single portion.

The core of the caliphate's mounted division was an elite unit which early Muslim historians named Tulai'a Mutaharrika (طليعة متحركة), or the '' mobile guard''. Initially, the nucleus of the mobile guard was formed from veterans of the cavalry corps under Khalid during the conquest of Iraq. They consisted half of the forces brought by Khalid from Iraq to Syria 4.000 soldiers out of 8.000 soldiers. This shock cavalry division played important roles to the victories in Battle of Chains, Battle of Walaja, Battle of Ajnadayn, Battle of Firaz, Battle of Maraj-al-Debaj

Battle of Marj-ud-Debaj ( ar, معركة مرج الديباج) was fought between the Byzantine army, survivors from the conquest of Damascus, and the Rashidun Caliphate army in September 634. It was a successful raid after three days of armi ...

, Siege of Damascus, Battle of Yarmouk, Battle of Hazir and the Battle of Iron Bridge against the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

and the Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Name ...

. Later, the splinter of this cavalry division under Al-Qa'qa ibn Amr at-Tamimi also involved in the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah, Battle of Jalula, and the Second siege of Emesa.

Modern historians and genealogists concluded that the stocks of early caliphate cavalry army that conquered from the western Maghreb of Africa, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

to the east of Central Asia are drawn from the stock of fierce Bedouin pastoral nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

s who take pride of their well-guarded mares genealogy, and called themselves the "People of the lance".

Horse

Caliphate Arabian noble cavalry mostly rode the legendary purebred Arabian horse, by fact the quality breeding of horses were held so dearly by the early caliphates who integrated traditions of Islam with their military practice.

Caliphate Arabian noble cavalry mostly rode the legendary purebred Arabian horse, by fact the quality breeding of horses were held so dearly by the early caliphates who integrated traditions of Islam with their military practice.Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphat ...

. The caliph instructed Salman Ibn Rabi'ah al-Bahili

Salman may refer to:

People

* Salman (name), people with the name

Places in Iran

* Salman, Khuzestan, a village in Khuzestan Province

* Salman, alternate name of Deh-e Salman, Lorestan, a village in Lorestan Province

* Salman, Razavi Khorasan, a ...

to establish systematic military program to maintain the quality of caliphate mounts. Salman enlisted most of the steeds within realm of caliphate to undergo such steps:

# Recording number and quality of horses available

# Differences between the Arabian purebreed and the hybrid breeds was to be carefully noted.

# Arabic structural Medical examination and Hippiatrica on each horses in regular basis including isolation and quarantine of sick horses

# Regular training between horses and their masters to achieve the disciplined communication between them

# Collective response training of the horses done in general routine

# Individual response training of the horses on advanced level

# Endurance and temperament training to perform in crowded and noisy place.

At the end of the program, both riders and horses obligated to enlisted in formal competition sponsored by Diwan al-Jund which consisted into two category:

# Racing competition to measure the speed and stamina of each hybrids

# Acrobat competition to measure the ability of the horses for difficult maneuvers during war.

Additionally, the already established cavalry divisions were obliged to undertook simulated combat operation raids during the winter and summer seasons, known as Tadrib al-Shawati wa al-Sawd'if, which were intended to maintain the quality of each cavalry forces, while also maintain the pressures towards the Byzantines, Persians, and other caliphate enemies while there is no major military campaign.

This profound tradition of breeding exaltation even became a basis for scholars of later era such as by Shafi'i jurist, Al-Mawardi, to establish the ruling of regular military share that the owner of noble purebreed Arabian (''al‑khayl al‑ʿitāq'') should be rewarded a share of booty three times of regular infantry soldiers, while owners of inferior mixed breeds received only twice infantry soldiers' share.

= Training

=

The technical training method of each horsemen in this cavalry was recorded in ''al-Fann al-Harbi In- Sadr al-Islam'' and Tarikh Tabari:

# Riding horses with saddles

# Riding horses without saddles

# Swordfighting without horses

# Horse charging with stabbing weapons

# Fighting with swords from the back of a moving horse

# Archery

# Mounted archery while the horse running

# Close combat while changing their seat position on the back of moving horse, facing backwards

Equipment

Arabian caliphate cavalry wearing heavy armors as according to Eduard Alofs, contrary to the popular beliefs, the Arabian, both the Rashidun cavalry or the cavalry of Ghassanid and the Lakhmid kingdom were not lightly armored scout horsemen. In fact, classic chroniclers such as Tabari, Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman ge ...

, and the Manual of Strategikon implied that the Arabian cavalry during the 5th century onwards were well armored heavy mounted troopers, Arabians usually covered their armors with dull-colored coats to prevent the sunburn on their metallic armor caused by hot climate of desert climate. Such Arabian knights were named ''Mujaffafa'' by early historians, which according to Martin Hinds were technically "Arabian Cataphracts" as they are fully armored both riders and horses".

The early caliphate armies generally neglected the use of stirrups despite long knowing of stirrups. al-Jahiz commented that the Arabs spurned double iron stirrups as it is viewed as a weakness, while also provided hindrance for skillful riders to maneuver during battles and can be a disadvantage if the rider falls but his legs are stuck in the stirrups.

Caliphate horsemen used the following weapons in battle:

* Mounted archery with flying gallop was practiced by the early caliphate regular Arab cavalry from Rashidun era onwards. Alof theorized "Mubarizun" elite division also used archery in close-combat duels for maximum arrow penetration against opponent armor.

* Caliphate horsemen also used thrown javelins as their weapon. Zubayr ibn al-Awwam, a seasoned Muhajir and early convert, who almost always brought horses during battle, is recorded to have killed his opponents at least in two occasions during his life. He killed Quraish nobleman Ubaydah ibn Sa'id from Umayyad clan during the Battle of Badr, who was wearing a full set of armor and Aventail that protected his entire body and face. Zubayr hurled his javelin aiming at the unprotected eye of Ubaydah and killed him immediately. The second occasion is during the Battle of Khaybar, Zubayr fought in a duel against a Jewish nobleman Yassir

Yasser (also spelled Yaser, Yasir, or Yassir; ar, ياسر, ''Yāsir'') is an Arabic male name.

Notable people with this given name

* Yasir ibn Amir (died 615 C.E.) is known in the Islamic traditions as the second person in history to be martyr ...

which Zubayr killed with a powerful javelin strike. Firsthand witnesses reported that Zubayr brandishing himself across the battlefield during the Battle of Hunayn

:''This is a sub-article to Muhammad after the conquest of Mecca.''

The Battle of Hunayn ( ar, غَزْوَة حُنَيْن, Ghazwat Hunayn) was between the Muslims of Muhammad and the Bedouins of the Qays, including its clans of Haw ...

while hung two javelins in his back.

* Early caliphate cavalry held their lance overhead posture with both hands.

Mubarizun

A select few apparatus of mounted soldiers who particularly skilled in duel using swords and various weapons were formed a commando unit called known as Mubarizun

The Mubarizun ( ar, مبارزون, "duelists", or "champions") formed a special unit of the Rashidun army during the Muslim conquests of the 7th century. The Mubarizun were a recognized part of the Muslim army with the purpose of engaging enem ...

s.

Their main task was charging with their horses until they find the enemy generals or field officers, in order to kidnap or slay them in close combat, so the enemy will lose their commanding figure amidst of battle.

Historical reconstructors like Marcus Junkelmann has practiced in historical reenactment that mounted close combat specialists like Mubarizuns could fight effectively on top of their mounts even without stirrup

A stirrup is a light frame or ring that holds the foot of a rider, attached to the saddle by a strap, often called a ''stirrup leather''. Stirrups are usually paired and are used to aid in mounting and as a support while using a riding animal ...

s. This is used by Alofs as an argument to debuff the majority historian beliefs that horsemen cannot fight effectively in close combat if they rode their horse without stirrups.

Aside from fighting with swords, lance, or mace, Mubarizuns also possessed a unique ability to use archery in close combat, where Alofs theorized that in mid range about five meters from the adversary, the duelists will exchange his lance with his bow and shoot the enemy from close range to achieve maximum penetration, while the duelist held the lance strapped between right leg and saddle.

Mahranite cavalry

Caliphate cavalry recruited from Al-Mahra tribe were known for their military prowess and skilled horsemen that often won battles with minimal or no casualties at all, which Amr ibn al As in his own words praised them as "''peoples who kill without being killed''". Amr was amazed by these proud warriors for their ruthless fighting skill and efficiency During Muslim conquest where they spearheaded Muslim army during the Battle of Heliopolis, the

Caliphate cavalry recruited from Al-Mahra tribe were known for their military prowess and skilled horsemen that often won battles with minimal or no casualties at all, which Amr ibn al As in his own words praised them as "''peoples who kill without being killed''". Amr was amazed by these proud warriors for their ruthless fighting skill and efficiency During Muslim conquest where they spearheaded Muslim army during the Battle of Heliopolis, the Battle of Nikiou

The Battle of Nikiou was a battle between Arab Muslim troops under General Amr ibn al-A'as and the Byzantine Empire in Egypt in May of 646.

Overview

Following their victory at the Battle of Heliopolis in July 640, and the subsequent capitulation ...

, and Siege Alexandria. Their commanders, Abd al-sallam ibn Habira al-Mahri were entrusted by 'Amr ibn al-'As to lead the entire Muslim army during the Arab conquest of north Africa. Abd al-sallam defeated the Byzantine imperial army in Libya, and throughout these campaigns Al-Mahra were awarded much land in Africa as recognition of their bravery. When Amr established the town of Fustat, he further rewarded Al-Mahri members additional land in Fustat which then became known as ''Khittat Mahra'' or the Mahra quarter. This land was used by the Al-Mahra tribes as a garrison.

During the turmoil of Second Fitna, more than 600 Mahranites were sent to North Africa to fight Byzantines and the Berber revolts.

Kharijite rebels

The 8th century chronicler, Al-Jahiz noted the ferociousness of Kharijites horsemen, who spent parts of their early career in Kufa as Rashidun garrison troop during the Muslim conquest of Persia before their rebellion against the caliphate. Al-Jahiz pointed out Kharijites steeds' speed could not intercepted by most rival cavalrymen in medieval era, save for the Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

Mamluks. Notable seditionist warriors included Abd Allah ibn Wahb al-Rasibi from Bajila tribe, who participated in the early conquests of Persia under Sa'd ibn abi Waqqas.

Al-Jahiz also added that the Kharijites were feared for their cavalry charge with their lances which could break any defensive line, and almost never lose when pitted against an equal number of opponents. Dr. Adam Ali M.A.PhD. postulated that Al-Jahiz assessment of the quality Kharijites quality are synonymous with the regular Arab cavalry as general in term of speed and charging maneuver. Their common ground with the caliphate military was even highlighted further by Professor Jeffrey Kenney, who traced back through older traditions that the embryo of Kharijites was even existed back in the times of prophet Muhammad, in the form of figure named Dhu'l Khuwaisira at-Tamim, one of Banu Tamim chieftain who appeared after the Battle of Hunayn

:''This is a sub-article to Muhammad after the conquest of Mecca.''

The Battle of Hunayn ( ar, غَزْوَة حُنَيْن, Ghazwat Hunayn) was between the Muslims of Muhammad and the Bedouins of the Qays, including its clans of Haw ...

who protested the war spoils distribution. In fact, ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Ḥabīb, a jurist and historian in the 9th century described the Berber Kharijites as a mirror match which resembles the Arabic caliphate martial tradition, except the loyalty to authority.

Ibn Nujaym al-Hanafi, Hanafi scholar said about Kharijites: ''"... kharijites are a folk possessing strength and zealotry, who revolt against the government due to a self-styled interpretation. They believe that government is upon falsehood, disbelief or disobedience that necessitates it being fought against, and they declare lawful the blood and wealth of the Muslims...”''.

Siege engineers

The Rashidun caliphate employed siege engines during their military campaigns.

Catapults

Catapults, called ''Manjaniq'', were evident in the history of the early caliphates. There is a long history of the Muslim armies from the battle of Khaybar. The prophet breached a Jewish fortress with catapults. Later on, Urwah ibn Masʽud and Ghaylan ibn Salamah also reportedly travelled to Jurash, near Abha in southwestern of Asir region in order to learn how to construct various Manjaniq catapults and Dabbabah siege ram as the city of Jurash were known for its siege workshops industry. Christides highlighted the high learning curves of the Arabs during the early caliphates that they could catch up with more established civilizations such as Byzantine in making complex war machines such as the ''Manjaniq'' catapult.

In the era of the caliphate, Catapults were used extensively in siege operations whenever the Muslim armies were expected to remain entrenched in one area for a long duration. Examples include Abu Ubaydah and Khalid's besieged Damascus, and furious artillery bombardments by Amr ibn al-As during the second siege of Alexandria which immediately caused the Christian garrison to surrender. Another record of such siege engines operations came from Abdallah ibn Sa'd's attack on the capital of Makuria, where the catapult engine of Abdallah caused the main cathedral structure of Makuria to crumble, compelling King Qalidurut to agree to ratify a ceasefire agreement with the former. The forces of Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas were also reported to able to quickly construct at least twenty siege engines during the Second siege of Babylon, despite their relatively short stints in the area after the battle of Qadisiyyah. According to an obscure record from Sebeos

Sebeos () was a 7th-century Armenian bishop and historian.

Little is known about the author, though a signature on the resolution of the Ecclesiastical Council of Dvin in 645 reads 'Bishop Sebeos of Bagratunis.' His writings are valuable as one o ...

, Mu'awiyah's fleet which was led by Bisr ibn abi Artha'ah is also reported to carry unspecified artillery engines that can throw "''balls of Greek fire''" within his ships during the siege of Constantinople.

Siege towers

Siege towers with scaling ladders are named ''al-Dabbdbah'' or ''al-dabr''. These wooden towers moved on wheels and were several stories tall. They were driven up to the foot of the besieged fortification and then the walls were pierced with a battering ram. Archers guarded the ram and the soldiers who moved it.

Other engines

Regular Muslim infantries also qualified on the battlefield construction and engineering such as when they were able to perfect the art of building pontoon bridges which allowed them to gain the upper hand during the Battle of the Bridge. Their expertise on this field also helped during the last phase of the Siege of Damascus, when the Muslim army built water rafts and dinghies to cross the trench.

Irregular conscripts

During the Islamic conquest of Sassanid Persia (633-656), some 12,000 elite Persian soldiers converted to Islam and served later on during the invasion of the empire.. During the Muslim conquest of Roman Syria (633-638), some 4,000 Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

Byzantine soldiers under their commander Joachim (later Abdullah Joachim) converted to Islam and served as regular troops in the conquest of both Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The r ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

. During the conquest of Egypt (641-644), Coptic converts to Islam were recruited. During the conquest of North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

, Berber converts to Islam were recruited as regular troops, who later made the bulk of the Rashidun army and later the Umayyad army in Africa.

Al-Abna'

Al-Abnāʾ was the descendants of Sasanian officers and soldiers of Persian and Daylam origins who intermarried with local Yemeni Arabs after they taken over Yemen from the Aksumite in the Aksumite–Persian wars. The Abnas had been garrisoned in Sanaa and their surrounding Their leaders converted to Islam and were active in the early Muslim conquests. They were gradually absorbed into the local population. They are considered siege-warfare experts. However, al-Jahiz outlined al-Abna lacked medieval era standard mobility.

Notable figures hailed from al-Abna was Fayruz al-Daylami, hero of caliphate who defended Yemen for a decade during Apostate wars, and Wahb ibn Munabbih, a prolific Rāwī of Hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

who later became a judge during the rule of caliph Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz.

Greeks

Some Greeks joined the caliphate army after they defected from Byzantine army. One example is Joachim, garrison commander of Aleppo, who defected along with his 4,000 garrison troops and fought loyally under the caliphate later.

Persian Asawir

As the conquest of Persia progressed, some Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Name ...

gentry converted into Islam and joined the Rashidun; these " Asawira"

Al-Jahiz outlined the quality of these Persians, which he identified as ''Khurasaniyyah'' as powerful heavy cavalry with cosiderable frontal charge power, although they lacked in speed.

They continued service under the caliphate until Abd al-Rahman ibn Muhammad ibn al-Ash'ath's rebellion. This heavily armored cavalry crushed by regular Arab cavalry led by Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf which possess more skill and discipline in Battle of Dayr al-Jamajim, As Hawting highlighted the different performance between caliphate cavalry and those of Abd al-Rahman al-Ash'ath's army including those of Persian Asawir, that "between the discipline and organisation of the Umayyads and their largely Syrian support and the lack of these qualities among their opponents in spite of, or perhaps rather because of, the more righteous and religious flavour of the opposition" is a recurring pattern in the civil wars of the period.

Jats

As the territory of caliphate has reached Sindh, there were reports that the local Jats had converted to Islam and even entered the military service. A notable local named Ziyad al-Hindi recorded has been entered the service under caliph Ali.

Arabic Christian levy

Chronicler Faraj recorded in his ''Fann 'Idarat al-Ma'arakah fi al-Islam'' that for certain situations, caliph Umar allowed a distinct unit which had not yet embraced Islam to be enlisted for military service. Prior to the Battle of Buwaib, Umar allowed al-Muthanna ibn Haritha to recruit Arab members of banu Taghlib and banu Nimr who had not yet embraced Islam for his service.

Field medics

Since the time of prophet, field medic roles were usually filled by wives or female relatives of the soldiers while during the period of Umar he extensively improved this role by changing it to make sure that every force being sent there had a team of medics, judges, and translators.

Camels

The Rashidun caliphate employed camels in various military roles since they respected the beasts' legendary endurance and were more numerous than horses in the Middle East, especially in dry areas. Extensive use of camels occurred during the initial campaigns of Muhammad, which continued onwards the existence of Rashidun caliphate and it successor states. The abundant availability of camel herds within caliphate enabled even infantries also mounted with camels during the caliphate military campaigns.

Al-Baghawi recorded an example that found from long narration of tradition, that a wealthy Arab soldier like Dhiraar ibn al-Azwar possessed 1,000 camels even before converting to Islam.

Furthermore, the development of Diwan al-Jund by caliph Umar ensured each caliphate soldiers possessed camels, despite their difficult tempers and expensive price. Both the camel riders and infantry of the Caliphate armies are known to have ridden camels during long-march campaigns.

Historians have generally agreed that the early caliphate's rapid conquests were facilitated by their large-scale utilization of dromedaries.

Rashidun army camels also bore offspring while marching to the battle. Tabari, a firsthand witness of Rashidun vanguard commander

The Rashidun caliphate employed camels in various military roles since they respected the beasts' legendary endurance and were more numerous than horses in the Middle East, especially in dry areas. Extensive use of camels occurred during the initial campaigns of Muhammad, which continued onwards the existence of Rashidun caliphate and it successor states. The abundant availability of camel herds within caliphate enabled even infantries also mounted with camels during the caliphate military campaigns.

Al-Baghawi recorded an example that found from long narration of tradition, that a wealthy Arab soldier like Dhiraar ibn al-Azwar possessed 1,000 camels even before converting to Islam.

Furthermore, the development of Diwan al-Jund by caliph Umar ensured each caliphate soldiers possessed camels, despite their difficult tempers and expensive price. Both the camel riders and infantry of the Caliphate armies are known to have ridden camels during long-march campaigns.

Historians have generally agreed that the early caliphate's rapid conquests were facilitated by their large-scale utilization of dromedaries.

Rashidun army camels also bore offspring while marching to the battle. Tabari, a firsthand witness of Rashidun vanguard commander Aqra' ibn Habis

Jebel Aqra ( ar, جبل الأقرع, translit=Jabal al-ʾAqraʿ, ; tr, Kel Dağı) is a limestone mountain located on the Syrian–Turkish border near the mouth of the Orontes River on the Mediterranean Sea. Rising from a narrow coastal plain, ...

, recorded that before the Battle of Anbar, the camels belonging to his soldiers were about to gave birth. However, since the Aqra' would not halt the operation, he instructed his soldiers to carry the newborn camels on the rumps of adult camels.

War-camel breeding

According to classical Muslim sources, caliph Umar acquired some fertile land in Arabia which were deemed fit for large-scale camel breeding to be established as ''Hima'', government-reserved land property used as pasture to raise camels that were being prepared to be sent to the front line for Jihad conquests.

Early sources recorded that the ''Hima'' of Rabadha and Diriyah produced 4,000 war camels annually during the reign of Umar, while during the reign of Uthman, both ''Hima'' lands further expanded until al-Rabadha Hima alone could produce 4,000 war camels.

At the time of Uthman death, there were said to be around 1,000 war camels already prepared in al-Rabadhah.

Modern Islamic studies researchers theorized institution of ''Hima'' by caliph Umar, was inspired by the earliest ''Hima'' established in Medina during the time of the prophet Muhammad. Muhammad himself instructed that some of private property at the outskirts of Medina was transformed into ''Hima''. Another reason the caliph Umar moved ''Hima'' from Medina was the increasing military demand for camels for which the lands near Medina no longer sufficed.

According to classical Muslim sources, caliph Umar acquired some fertile land in Arabia which were deemed fit for large-scale camel breeding to be established as ''Hima'', government-reserved land property used as pasture to raise camels that were being prepared to be sent to the front line for Jihad conquests.

Early sources recorded that the ''Hima'' of Rabadha and Diriyah produced 4,000 war camels annually during the reign of Umar, while during the reign of Uthman, both ''Hima'' lands further expanded until al-Rabadha Hima alone could produce 4,000 war camels.

At the time of Uthman death, there were said to be around 1,000 war camels already prepared in al-Rabadhah.

Modern Islamic studies researchers theorized institution of ''Hima'' by caliph Umar, was inspired by the earliest ''Hima'' established in Medina during the time of the prophet Muhammad. Muhammad himself instructed that some of private property at the outskirts of Medina was transformed into ''Hima''. Another reason the caliph Umar moved ''Hima'' from Medina was the increasing military demand for camels for which the lands near Medina no longer sufficed.

Use in combat

David Nicolle also mentioned the use of distinct camel cavalry during the battle of Qadisiyyah. It is known that horses can be scared by the stench of camels.

Camel defensive lines

According to John Walter Jandora in his Yarmouk reconstruction study, for the open-battle scenario, the abundance of camels brought by the army during their campaigns were used to form a line of camels positioned on the rear of Muslim battle lines, between the infantry lines and the camp perimeter which were positioned behind them, where reserve troops (''al-Saqah''), supplies and camp followers were located. Jandora argued it is used as a fail-safe, in case of breaches by enemy cavalry charges, which act as a deterrent that even stopped the powerful charge of the Byzantine Cataphract due to the beasts' large frames and foul tempers.

Mahranite camelier corps

Amr ibn al-As led a ruthless cavalry corps from tribes of Al-Mahra who were famous for their "invincible battle skills on top of their mounts", during the conquests of Egypt and north Africa. Al-Mahra tribes were experts in camelry and famed for their high-class Mehri camel breed which were renowned for their speed, agility and toughness.

Camel corpse bridge in al-Anbar

During the Battle of al-Anbar

Battle of Al-Anbar ( ar, معركة الأنبار) was between the Muslim Arab army under the command of Khalid ibn al-Walid and the Sasanian Empire. The battle took place at Anbar which is located approximately 80 miles from the ancient city of ...

, Khalid instructed his soldiers to slaughter many sickly camels and throw them into the trench dug by the Persian defenders in front of the wall of Anbar fortress. The heap of dead camels served as a bridge for Khalid cavalry to cross the trench and breach the fortress.

Use for transport and logistics

Similar to the infantry, the archer corps of the Rashidun caliphate were mounted during their movements during their marches. The stamina and strength of camels along with their abundant availability across the caliphate realm by the army enabled their famous fast mass mobilization. Even the horsemen preferred riding camels during a march as they wanted to save their steed's energy for battles and raids.

Use as emergency rations

Desperate caravaners are known to have consumed camels' urine and to have slaughtered them when their resources were exhausted.

Khalid's legendary camels' desert crossing

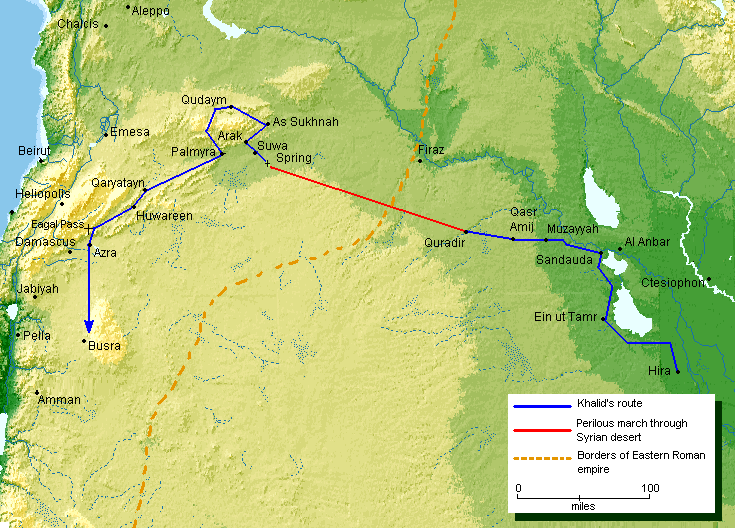

Around 634, after the clash at the Battle of Firaz against intercepting Byzantine forces, caliph Abu Bakr immediately instructed Khalid to reinforce the contingents of Abu Ubaydah, Amr ibn al-As, and Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan which started to invade Syria. Khalid immediately started his nearly impossible journey with his elite forces after leaving Muthanna ibn Haritha as his deputy in Iraq and instructed his soldiers to make each camel drink as much as possible before they started the six-day nonstop march without resupply. In the end, Khalid managed to reach Suwa spring and immediately defeated the Byzantine garrison in Arak, Syria,

Around 634, after the clash at the Battle of Firaz against intercepting Byzantine forces, caliph Abu Bakr immediately instructed Khalid to reinforce the contingents of Abu Ubaydah, Amr ibn al-As, and Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan which started to invade Syria. Khalid immediately started his nearly impossible journey with his elite forces after leaving Muthanna ibn Haritha as his deputy in Iraq and instructed his soldiers to make each camel drink as much as possible before they started the six-day nonstop march without resupply. In the end, Khalid managed to reach Suwa spring and immediately defeated the Byzantine garrison in Arak, Syria,[le Strange, 1890, p]

395

/ref> who were surprised by Khalid's force's sudden emergence from the desert.

According to Hugh Kennedy, historians across the ages assessed this daring journey with various expressions of amazement. Classical Muslim historians praised the marching force's perseverance as a miracle and work of god, while most western modern historians regard this as solely the genius of Khalid. It is Khalid, whose, in Hugh Kennedy's opinion, imaginative thinking effected this legendary feat. The historian Moshe Gil calls the march "a feat which has no parallel" and a testament to "Khalid's qualities as an outstanding commander"., while Laura Veccia Vaglieri and Patricia Crone dismissed the adventure of Khalid as never having happened as they thought it logically impossible. Nevertheless, military historian Richard G. Davis explained that Khalid imaginatively employed camel supply trains to make this journey possible. Those well hydrated camels that accompanied his journey were proven before in the Battle of Ullais for such a risky journey. Khalid resorted to slaughtering many camels for provisions for his desperate army.

Strategy and tactics

Field formation

When the army was on the march, it always halted on Fridays. When on march, the day's march was never allowed to be so long as to exhaust the troops. The stages were selected with reference to the availability of water and other provisions. The advance was led by an advance guard consisting of a regiment or more. Then came the main body of the army, and this was followed by the women and children and the baggage loaded on camels. At the end of the column moved the rear guard. On long marches the horses were led; but if there was any danger of enemy interference on the march, the horses were mounted, and the cavalry thus formed would act either as the advance guard or the rear guard or move wide on a flank, depending on the direction from which the greatest danger loomed.

When on march the army was divided into:

*''Muqaddima'' (مقدمة) - "the vanguard"

*''Qalb'' (قلب) - "the center"

*''Al-khalf'' (الخلف) - "the rear"

*''Al-mu'akhira'' (المؤخرة) - "the rear guard".

Divisions in battle

The army was organized on the decimal system.

On the battlefield the army was divided into sections. These sections were:

*''Qalb'' (قلب) - the center

*''Maymana'' (ميمنه) - the right wing

*''Maysara'' (ميسرة) - the left wing

Each section was under a commander and was at a distance of about 150 meters from the others. Every tribal unit had its leader called an ''arif''. In such units, there were commanders for each 10, 100 and 1,000 men, the latter-most corresponding to regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

s. The grouping of regiments to form larger forces was flexible, varying with the situation. ''Arifs'' were grouped and each group was under a commander called ''amir al-ashar'' and ''amir al-ashars'' were under the command of a section commander, who were under the command of the commander in chief, ''amir al-jaysh''.

Other components of the army were:

*''Rijal'' (رجال) - infantry

*''Fursan'' (فرسان) - cavalry

*''Rumat'' (رماة) - archers

*''Tali'ah'' (طليعة) - patrols, who monitored enemy movements

# Rukban'' (ركبان) - camel corps

# Nuhhab al-mu'an'' (نهّاب المؤن) - foraging parties, Rukban (ركبان)

Cavalry

The general strategy of early Muslim cavalry was to utilize their speed to outpace their adversaries. Muslim generals such as Khalid ibn Walid and Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas are known to have employed this advantage against both the Sassanid army and the Byzantine army as the main drawback of the armies of Sassanid Persian Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

was their lack of mobility.[A. I. Akram (1970). The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Waleed, His Life and Campaigns. National Publishing House, Rawalpindi. ] But only part of the Rashidun army was cavalry.

Another remarkable strategy developed by Al-Muthanna and later followed by other Muslim generals was not moving far from the desert so long as there were opposing forces within striking distance of its rear. The idea was to fight the battles close to the desert, with safe escape routes open in case of defeat. The desert was not only a haven of security for them, where the Sassanid army and Byzantine armies would not venture, but also a region of free, fast movement in which their camel-mounted troops could easily and rapidly move to any destination that they chose.

Cavalry usage during siege warfare

The tactics used by Iyad in his Mesopotamian campaign were similar to those employed by the Muslims in Palestine, though in Iyad's case the contemporary accounts reveal his specific ''modus operandi'', particularly in Raqqa. The operation to capture that city entailed positioning cavalry forces near its entrances, preventing its defenders and residents from leaving or rural refugees from entering. Concurrently, the remainder of Iyad's forces cleared the surrounding countryside of supplies and took captives. These dual tactics were employed in several other cities in al-Jazira. They proved effective in gaining surrenders from targeted cities running low on supplies and whose satellite villages were trapped by hostile troops.

Ubadah ibn al-Samit, another Rashidun commander, is also recorded to have developed his own distinct strategy which involved the use of cavalry during siege warfare. During a siege, Ubadah would dig a large hole, deep enough to hide a considerable number of horsemen near an enemy garrison, and hid his cavalry there during the night. When the sun rose and the enemy city opened their gates for the civilians in the morning, Ubadah and his hidden cavalry then emerged from the hole and stormed the gates as the unsuspecting enemy could not close the gate before Ubadah's horsemen entered. This strategy was used by Ubadah during the Siege of Laodicea and Siege of Alexandria

Battle of Alexandria, Raid on Alexandria, or Siege of Alexandria may refer to one of these military operations fought in or near the city of Alexandria, Egypt:

* Siege of Alexandria (169 BC), during the Syrian Wars

* Siege of Alexandria (47 BC), d ...

.

Intelligence and espionage

It was one of the most highly developed departments of the army which proved helpful in most of the campaigns. The espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tang ...

(جاسوسية) and intelligence services were first organised by Muslim general Khalid ibn Walid during his campaign to Iraq. Later, when he was transferred to the Syrian front, he organized the espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tang ...

department there as well. As the term of military rulings during Rashidun caliphate were intertwined with Sharia ruling, the concept of espionage also became subject in jurisprudential term, as in the modern era, Islamic official committee of Saudi Arabia Scholars also used the practice of az-Zubayr as one of their source of fatawa, such as an act of government to spying any endangering act from enemy of the state, such as criminal behavior, alleged terrorism, and other illegal conduct, were allowed in Islam jurisprudence.

Border raids and expansions

During the tenure of Khalid ibn al-Walid in the Muslim conquest of Iraq, he formed ''Ummal'', military units that act as his deputy personnel to govern, watch, and collect Kharaj

Kharāj ( ar, خراج) is a type of individual Islamic tax on agricultural land and its produce, developed under Islamic law.

With the first Muslim conquests in the 7th century, the ''kharaj'' initially denoted a lump-sum duty levied upon the ...

and Jizya in the occupied areas, or as raiding parties in uncaptured cities or settlements.Qasr ibn Hubayrah

Qasr Ibn Hubayra ( ar, قصر ابن هبيرة) was a city of medieval Iraq, north of Hillah and Babylon.

History

The name ''Qasr Ibn Hubayrah'' means "the castle or palace of Ibn Hubayra", referring to the city's founder, Yazid ibn Umar ibn H ...

and north of Hillah.

Military organizations within the state department

Military governorship

The caliphs of Rashidun founded an administrative body which was based on military governorship, known as Jund. Jund were garrisoned in a capital which became the military headquarters named Amsar. Border military posts' fortifications of Jund were also established and named Ribat.