Ralph Vary Chamberlin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

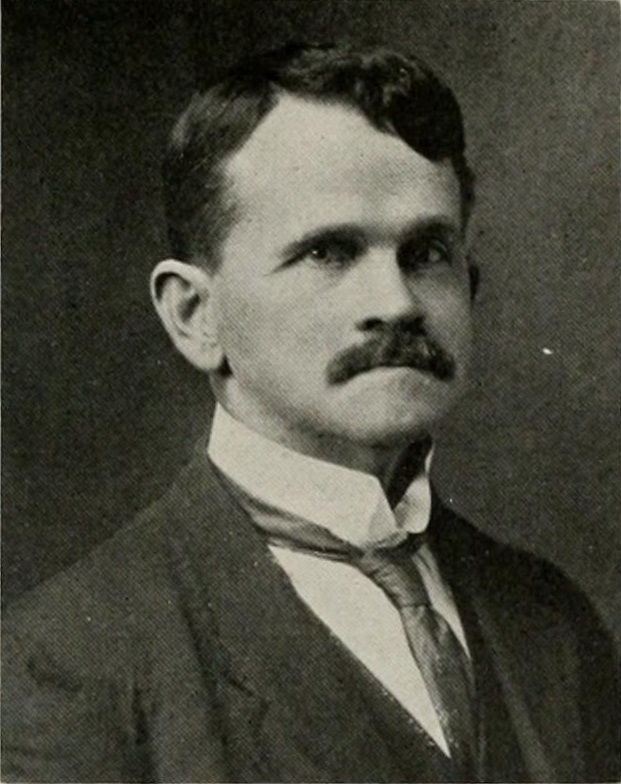

Ralph Vary Chamberlin (January 3, 1879October 31, 1967) was an American biologist, ethnographer, and historian from Salt Lake City, Utah. He was a faculty member of the University of Utah for over 25 years, where he helped establish the School of Medicine and served as its first dean, and later became head of the zoology department. He also taught at Brigham Young University and the

After returning from Cornell, Chamberlin was hired by the University of Utah, where he worked from 1904 to 1908, as an assistant professor (19041905) then full professor. He soon began improving biology courses, which at the time were only of high school grade, to collegiate standards, and introduced new courses in vertebrate histology and embryology. He was the first dean of University of Utah School of Medicine, serving from 1905 to 1907.

*

*

During the summer of 1906, his plans to teach a summer course in embryology at the

After returning from Cornell, Chamberlin was hired by the University of Utah, where he worked from 1904 to 1908, as an assistant professor (19041905) then full professor. He soon began improving biology courses, which at the time were only of high school grade, to collegiate standards, and introduced new courses in vertebrate histology and embryology. He was the first dean of University of Utah School of Medicine, serving from 1905 to 1907.

*

*

During the summer of 1906, his plans to teach a summer course in embryology at the

In 1908, Chamberlin was hired to lead the Biology Department at Brigham Young University (BYU), a university owned and operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), during a period which BYU president

In 1908, Chamberlin was hired to lead the Biology Department at Brigham Young University (BYU), a university owned and operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), during a period which BYU president

Chamberlin was a prolific taxonomist of invertebrate animals who named and described over 4,000 species, specializing in the study of

Chamberlin was a prolific taxonomist of invertebrate animals who named and described over 4,000 species, specializing in the study of  Although a prolific describer of species, his legacy to myriapod taxonomy has been mixed. Many of Chamberlin's descriptions of centipedes and millipedes were often brief and/or unillustrated, or illustrated in ways which hindered their use in identification by other researchers. He described some new species based solely on location, or on subtle leg differences now known to change during molting, and many of Chamberlin's names have subsequently been found to be, or are suspected to be, synonyms of species already described. Biologist Richard Hoffman, who worked with Chamberlin on the 1958 checklist, later described Chamberlin as "an exemplar of minimal taxonomy", and stated his taxonomic work on Central American myriapods "introduced far more problems than progress, a pattern which was to persist for many decades to come". Hoffman wrote Chamberlin was "an admitted ' alpha taxonomist' whose main interest was naming new species", although recognized Chamberlin's work with

Although a prolific describer of species, his legacy to myriapod taxonomy has been mixed. Many of Chamberlin's descriptions of centipedes and millipedes were often brief and/or unillustrated, or illustrated in ways which hindered their use in identification by other researchers. He described some new species based solely on location, or on subtle leg differences now known to change during molting, and many of Chamberlin's names have subsequently been found to be, or are suspected to be, synonyms of species already described. Biologist Richard Hoffman, who worked with Chamberlin on the 1958 checklist, later described Chamberlin as "an exemplar of minimal taxonomy", and stated his taxonomic work on Central American myriapods "introduced far more problems than progress, a pattern which was to persist for many decades to come". Hoffman wrote Chamberlin was "an admitted ' alpha taxonomist' whose main interest was naming new species", although recognized Chamberlin's work with

Chamberlin's work extended beyond biology and anthropology to include historical, philosophical, and theological writings. At BYU he published several articles in the student newspaper on topics such as

Chamberlin's work extended beyond biology and anthropology to include historical, philosophical, and theological writings. At BYU he published several articles in the student newspaper on topics such as

The taxa (e.g. genus or species) named after Chamberlin are listed below, followed by author(s) and year of naming, and taxonomic family. Taxa are listed as originally described: subsequent research may have reassigned taxa or rendered some as invalid

The taxa (e.g. genus or species) named after Chamberlin are listed below, followed by author(s) and year of naming, and taxonomic family. Taxa are listed as originally described: subsequent research may have reassigned taxa or rendered some as invalid

Chamberlin's publications on spiders

from the

World Spider Catalog

'

Chamberlin's publications on myriapods

from th

International Society of MyriapodologyWorks by Ralph Vary Chamberlin

at Biodiversity Heritage Library * *

Ralph Vary Chamberlin papers, 1890–1969

an

Ralph Chamberlin photograph collection

(

Ralph Vary Chamberlin papers, 1940–1967

A Register of the Collection at the Utah State Historical Society {{DEFAULTSORT:Chamberlin, Ralph Vary American ethnographers American arachnologists Arachnologists Ethnobiologists Myriapodologists 1879 births 1967 deaths Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Historians of Utah Brigham Young University faculty Harvard University staff University of Utah faculty University of Pennsylvania faculty Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences alumni University of Utah alumni Scientists from Salt Lake City 20th-century American zoologists Latter Day Saints from Utah

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universit ...

, and worked for over a decade at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, where he described species from around the world.

Chamberlin was a prolific taxonomist who named over 4,000 new animal species in over 400 scientific publications. He specialized in arachnid

Arachnida () is a class of joint-legged invertebrate animals ( arthropods), in the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and ...

s (spiders, scorpions, and relatives) and myriapods (centipedes, millipedes, and relatives), ranking among the most prolific arachnologists and myriapodologists in history. He described over 1,400 species of spiders, 1,000 species of millipedes, and the majority of North American centipedes, although the quantity of his output was not always matched with quality, leaving a mixed legacy to his successors. He also did pioneering ethnobiological studies with the Goshute and other indigenous people of the Great Basin, cataloging indigenous names and cultural uses of plants and animals. Chamberlin was celebrated by his colleagues at the University of Utah, however he was disliked among some arachnologists, including some of his former students. After retirement he continued to write, publishing on the history of education in his home state, especially that of the University of Utah.

Chamberlin was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). In the early twentieth century, Chamberlin was among a quartet of popular Mormon professors at Brigham Young University whose teaching of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

and biblical criticism resulted in a 1911 controversy among University and Church officials, eventually resulting in the resignation of him and two other professors despite widespread support from the student body, an event described as Mormonism's "first brush with modernism".

Biography

Early life and education

Ralph Vary Chamberlin was born on January 3, 1879, in Salt Lake City, Utah, to parents William Henry Chamberlin, a prominent builder and contractor, and Eliza Frances Chamberlin (née Brown). Chamberlin traced his paternal lineage to an English immigrant settling in theMassachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

in 1638, and his maternal lineage to an old Pennsylvania Dutch

The Pennsylvania Dutch ( Pennsylvania Dutch: ), also known as Pennsylvania Germans, are a cultural group formed by German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. They emigrated primarily from German-spe ...

family. Born to Mormon parents, the young Chamberlin attended Latter-day Saints' High School, and although very interested in nature, initially decided to study mathematics and art before choosing biology. His brother William, the eldest of 12 children, also shared Ralph's scientific interests and would later teach alongside him. Ralph attended the University of Utah, graduating with a B.S. degree in 1898, and subsequently spent four years teaching high school and some college-level courses in biology as well as geology, chemistry, physics, Latin, and German at Latter-day Saints' University

Ensign College (formerly LDS Business College) is a private college in Salt Lake City, Utah. The college is owned by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and operates under its Church Educational System. It also includes ...

. By 1900 he had authored nine scientific publications.

In the summer of 1902 Chamberlin studied at the Hopkins Marine Station of Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

, and from 1902 to 1904 studied at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to ...

under a Goldwin Smith Fellowship, and was a member of the Gamma Alpha fraternity and Sigma Xi honor society. He studied under entomologist John Henry Comstock

John Henry Comstock (February 24, 1849 – March 20, 1931) was an eminent researcher in entomology and arachnology and a leading educator. His work provided the basis for classification of butterflies, moths, and scale insects.

Early life and ...

and earned his doctorate in 1904. His dissertation was a taxonomic revision of the wolf spiders

Wolf spiders are members of the family Lycosidae (). They are robust and agile hunters with excellent eyesight. They live mostly in solitude, hunt alone, and do not spin webs. Some are opportunistic hunters, pouncing upon prey as they find it or c ...

of North America, in which he reviewed all known species north of Mexico, recognizing 67 out of around 150 nominal species as distinct and recognizable. Zoologist Thomas H. Montgomery regarded Chamberlin's monograph as one of "decided importance" in using the structure of pedipalps (male reproductive organs) to help define genera, and in its detailed descriptions of species.

Early career: University of Utah

After returning from Cornell, Chamberlin was hired by the University of Utah, where he worked from 1904 to 1908, as an assistant professor (19041905) then full professor. He soon began improving biology courses, which at the time were only of high school grade, to collegiate standards, and introduced new courses in vertebrate histology and embryology. He was the first dean of University of Utah School of Medicine, serving from 1905 to 1907.

*

*

During the summer of 1906, his plans to teach a summer course in embryology at the

After returning from Cornell, Chamberlin was hired by the University of Utah, where he worked from 1904 to 1908, as an assistant professor (19041905) then full professor. He soon began improving biology courses, which at the time were only of high school grade, to collegiate standards, and introduced new courses in vertebrate histology and embryology. He was the first dean of University of Utah School of Medicine, serving from 1905 to 1907.

*

*

During the summer of 1906, his plans to teach a summer course in embryology at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

were cancelled when he suffered a serious accident in a fall, breaking two leg bones and severing an artery in his leg. In 1907, University officials decided to merge the medical school into an existing department, which made Chamberlin's deanship obsolete. He resigned as dean in May, 1907, although remained a faculty member. The medical students strongly objected, crediting the school's gains over the past few years largely to his efforts.

In late 1907 and early 1908, Chamberlin became involved in a bitter lawsuit with fellow Utah professor Ira D. Cardiff that would cost them both their jobs. Cardiff, a botanist hired in spring of 1907, claimed Chamberlin offered him a professorship with a salary of $2,000 to $2,250 per year, but upon hiring was offered only $1,650 by the university regents. Cardiff filed suit for $350, which a court initially decided Chamberlin must pay, and Chamberlin's wages were garnished. The two became estranged and uncommunicative. There had been tension between them for some time—Chamberlin's supporters claimed Cardiff was involved in his dismissal as dean—and the '' Salt Lake Tribune'' noted "friction between the two men, of a different nature and not entirely due to financial matters, arose even before Professor Cardiff received his appointment". In March 1908 the university regents fired both Chamberlin and Cardiff, appointing a single new professor to head the departments of zoology and botany. In July, upon appeal, the suit was overturned and Cardiff ordered to pay costs. Chamberlin had by then secured a job at Brigham Young University.

Brigham Young University

In 1908, Chamberlin was hired to lead the Biology Department at Brigham Young University (BYU), a university owned and operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), during a period which BYU president

In 1908, Chamberlin was hired to lead the Biology Department at Brigham Young University (BYU), a university owned and operated by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), during a period which BYU president George H. Brimhall

George Henry Brimhall (December 9, 1852 – July 29, 1932) was president of Brigham Young University (BYU) from 1904 to 1921. After graduating from Brigham Young Academy (BYA), Brimhall served as principal of Spanish Fork schools and then as distr ...

sought to increase its academic standing. LDS College professor J. H. Paul, in a letter to Brimhall, had written Chamberlin was "one of the world's foremost naturalists, though, I think, he is only about 28 years of age. I have not met his equal ... We must not let him drift away". Chamberlin oversaw expanded biology course offerings and led insect-collecting trips with students. Chamberlin joined a pair of newly hired brothers on the faculty, Joseph and Henry Peterson, who taught psychology and education. Chamberlin and the two Petersons worked to increase the intellectual standing of the University. In 1909 Chamberlin's own brother William H. Chamberlin was hired to teach philosophy. The four academics, all active members of the Church, were known for teaching modern scientific and philosophic ideas and encouraging lively debate and discussion. The Chamberlins and Petersons held the belief that the theory of evolution was compatible with religious views, and promoted historical criticism

Historical criticism, also known as the historical-critical method or higher criticism, is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts in order to understand "the world behind the text". While often discussed in terms of ...

of the Bible, the view that the writings contained should be viewed from the context of the time: Ralph Chamberlin published essays in the ''White and Blue'', BYU's student newspaper, arguing that Hebrew legends and historical writings were not to be taken literally. In an essay titled "Some Early Hebrew Legends

Some may refer to:

*''some'', an English word used as a determiner and pronoun; see use of ''some''

*The term associated with the existential quantifier

*"Some", a song by Built to Spill from their 1994 album ''There's Nothing Wrong with Love''

*S ...

" Chamberlin concluded: "Only the childish and immature mind can lose by learning that much in the Old Testament is poetical and that some of the stories are not true historically." Chamberlin believed that evolution explained not only the origin of organisms but of human theological beliefs as well.

In late 1910, complaints from stake presidents inspired an investigation into the teachings of the professors. Chamberlin's 1911 essay "Evolution and Theological Belief

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

" was considered particularly objectionable by school officials. In early 1911 Ralph Chamberlin and the Peterson brothers were offered a choice to either stop teaching evolution or lose their jobs. The three professors were popular among students and faculty, who denied that the teaching of evolution was destroying their faith. A student petition in support of the professors signed by over 80% of the student body was sent to the administration, and then to local newspapers. Rather than change their teachings, the three accused professors resigned in 1911, while William Chamberlin remained for another five years.

In 1910, Chamberlin was elected a fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Pennsylvania and Harvard

After leaving Brigham Young, Chamberlin was employed as a lecturer and George Leib Harrison Foundation research fellow at theUniversity of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universit ...

from 1911 to 1913. From March 1913 to December 31, 1925, he was the Curator of Arachnids, Myriapods, and Worms at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

, where many of his scientific contributions were made. Here his publications included surveys of all known millipedes of Central America and the West Indies; and descriptions of animals collected by the Canadian Arctic Expedition (1913–1916); by Stanford and Yale expeditions to South America; and by various expeditions of the USS ''Albatross''. He was elected a member of the American Society of Naturalists The American Society of Naturalists was founded in 1883 and is one of the oldest professional societies dedicated to the biological sciences in North America. The purpose of the Society is "to advance and diffuse knowledge of organic evolution and o ...

and the American Society of Zoologists The Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology is organized to integrate the many fields of specialization which occur in the broad field of biology..

The society was formed in 1902 as the American Society of Zoologists, through the merger of ...

in 1914, and in 1919 served as second vice-president of the Entomological Society of America. He served as a technical expert for the U.S. Horticultural Board and U.S. Biological Survey

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is an agency within the United States Department of the Interior dedicated to the management of fish, wildlife, and natural habitats. The mission of the agency is "working with oth ...

from 1923 until the mid 1930s.

Return to Utah

Chamberlin returned to the University of Utah in 1925, where he was made head of the departments of zoology and botany. When he arrived, the faculty consisted of one zoologist, one botanist, and an instructor. He soon began expanding the size and diversity of the biology program, and by the time of his retirement the faculty consisted of 16 professors, seven instructors, and three special lecturers. He was the university's most celebrated scientist according to Sterling M. McMurrin, and his course on evolution was among the most popular on campus. He established the journal ''Biological Series of the University of Utah'' and supervised the graduate work of several students who would go on to distinguished careers, including Willis J. Gertsch,Wilton Ivie

Vaine Wilton Ivie (March 28, 1907 – August 8, 1969) was an American arachnologist, who described hundreds of new species and many new genera of spiders, both under his own name and in collaboration with Ralph Vary Chamberlin. He was employed b ...

, William H. Behle

William Harroun Behle (May 13, 1909 – February 26, 2009) was an American ornithologist from Utah. He published around 140 papers on the biogeography and taxonomy of birds, focusing largely on birds of the Great Basin. Behle was born in Salt Lake ...

and Stephen D. Durrant

Stephen David Durrant (1902–1975) was an American mammalogist from Salt Lake City, Utah and past president of the American Society of Mammalogists known for his work with pocket gophers of the genus '' Thomomys'' and other rodents of the Great ...

; the latter three would later join Chamberlin as faculty members. From 1930–1939, Chamberlin was secretary-treasurer of the Salt Lake City Mosquito Abatement Board and conducted mosquito surveys of the region, identifying marshes controlled by local hunting clubs as the main source of salt marsh mosquitoes plaguing the city. From 1938-1939 he took a year-long sabbatical, during which he studied in European universities and museums, presided over a section of the International Congresses of Entomology in Berlin, and later studied biology and archaeology in Mexico and South America. In 1942 he received an honorary Doctor of Science from the University of Utah. He retired in 1948, and in 1957, an honor ceremony was held by the Utah Phi Sigma Society in which a portrait of Chamberlin painted by Alvin L. Gittins

Alvin L. Gittins (17 January 1922 – 7 March 1981) was an English-born artist who was a professor at the University of Utah. He has been described as "one of he United Statesgreatest portrait artists ever".

Life and career

Gittins was born ...

was donated to the University and a book of commemorative letters produced. In 1960 the University of Utah Alumni Association awarded Chamberlin its Founders Day Award for Distinguished Alumni, the university's highest honor.

Chamberlin was noted by colleagues at Utah for being a lifelong champion of the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article hist ...

and instilling in his students ideas that natural processes must be used to explain human existence. Angus and Grace Woodbury wrote that one of his greatest cultural contributions was his ability "to lead the naive student with fixed religious convictions gently around that wide gulf that separated him from the trained scientific mind without pushing him over the precipice of despair and illusion." His influence continued as his students became teachers, gradually increasing societal understanding of evolution and naturalistic perspectives. His colleague and former student Stephen Durrant stated "by word, and especially by precept, he taught us diligence, inquisitiveness, love of truth, and especially scientific honesty". Durrant compared Chamberlin to noted biologists such as Spencer Fullerton Baird

Spencer Fullerton Baird (; February 3, 1823 – August 19, 1887) was an American naturalist, ornithologist, ichthyologist, Herpetology, herpetologist, and museum curator. Baird was the first curator to be named at the Smithsonian Institution. He ...

and C. Hart Merriam in the scope of his contributions science.

Personal life and death

On July 9, 1899, Chamberlin married Daisy Ferguson of Salt Lake City, with whom he had four children: Beth, Ralph, Della, and Ruth. His first marriage ended in divorce in 1910. On June 28, 1922, he married Edith Simons, also of Salt Lake, and with whom he had six children: Eliot, Frances, Helen, Shirley, Edith, and Martha Sue. His son Eliot became a mathematician and 40-year professor at the University of Utah. Chamberlin's second wife died in 1965, and Chamberlin himself died in Salt Lake City after a short illness on October 31, 1967, at the age of 88. He was survived by his 10 children, 28 grandchildren, and 36 great-grandchildren.Research

Chamberlin's work includes more than 400 publications spanning over 60 years. The majority of his research concerned the taxonomy of arthropods and other invertebrates, but his work also included titles in folklore, economics, anthropology, language, botany, anatomy, histology, philosophy, education, and history. He was a member of theAmerican Society of Naturalists The American Society of Naturalists was founded in 1883 and is one of the oldest professional societies dedicated to the biological sciences in North America. The purpose of the Society is "to advance and diffuse knowledge of organic evolution and o ...

, Torrey Botanical Club, New York Academy of Sciences, Boston Society of Natural History, Biological Society of Washington, and the Utah Academy of Sciences.

Taxonomy

Chamberlin was a prolific taxonomist of invertebrate animals who named and described over 4,000 species, specializing in the study of

Chamberlin was a prolific taxonomist of invertebrate animals who named and described over 4,000 species, specializing in the study of arachnid

Arachnida () is a class of joint-legged invertebrate animals ( arthropods), in the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and ...

s ( spiders, scorpions, and their relatives), and myriapods ( millipedes, centipedes, and relatives), but also publishing on mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is es ...

s, marine worms, and insects. By 1941 he had described at least 2,000 species, and by 1957 had described a total of 4,225 new species, 742 new genera, 28 new families, and 12 orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* Heterarchy, a system of organization wherein the elements have the potential to be ranked a number of ...

. Chamberlin's taxonomic publications continued to appear until at least 1966.

Chamberlin ranks among the most prolific arachnologists in history. In a 2013 survey of the most prolific spider systematists, Chamberlin ranked fifth in total number of described species (1,475) and eighth in number of species that were still valid (984), i.e. not taxonomic synonyms of previously described species. At the University of Utah Chamberlin co-authored several works with his students Wilton Ivie

Vaine Wilton Ivie (March 28, 1907 – August 8, 1969) was an American arachnologist, who described hundreds of new species and many new genera of spiders, both under his own name and in collaboration with Ralph Vary Chamberlin. He was employed b ...

and Willis J. Gertsch, who would both go on to become notable spider scientists: the "famous duo" of Chamberlin and Ivie described hundreds of species together. Chamberlin described or co-described more than a third of the 621 spiders known to occur in his native Utah. Chamberlin was also a leading expert in North American tarantulas, describing over 60 species. Chamberlin worked with other groups of arachnids as well, including scorpions, harvestmen

The Opiliones (formerly Phalangida) are an Order (biology), order of arachnids Common name, colloquially known as harvestmen, harvesters, harvest spiders, or daddy longlegs. , over 6,650 species of harvestmen have been discovered worldwide, alth ...

, and schizomid

Schizomida (common name shorttailed whipscorpion) is an order of arachnids, generally less than in length.

The order is not yet widely studied. About 300 species of schizomids have been described worldwide, most belonging to the Hubbardiidae fa ...

s, and described several pseudoscorpions with his nephew Joseph C. Chamberlin, himself a prominent arachnologist.

Among fellow arachnologists, Chamberlin was regarded as influential but not particularly well-liked: in many of his papers co-authored with Ivie, it was Ivie himself who did most of the collecting, and describing, while Chamberlin remained first author, and a 1947 quarrel over recognition led to Ivie abandoning arachnology for many years. When arachnologist Arthur M. Chickering sent Chamberlin a collection of specimens from Panama, Chamberlin never returned them and in fact published on them, which made Chickering reluctant to collaborate with colleagues. Chamberlin is said to have eventually been banned from the Museum of Comparative Zoology by Ernst Mayr in his later years, and after Chamberlin's death his former student Gertsch said "his natural meanness finally got him".

Chamberlin's other major area of study was myriapods. He was publishing on centipedes as early as 1901, and between then and around 1960 was the preeminent, if not exclusive, researcher of North American centipedes, responsible for naming the vast majority of North American species, and many from around the world. In addition, he named more than 1,000 species of millipedes, ranking among the three most prolific millipede taxonomists in history. His 1958 "Checklist of the millipeds of North America", a compilation eight years in the making of all records and species north of Mexico, represented nearly a 600% increase in species recorded from the previous such list published over 50 years earlier, although the work itself described no new species. Chamberlin contributed articles on millipedes, pauropods and symphylans to the 1961 edition of the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The ( Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various ...

''.

stone centipede

''Lithobius'' is a large genus of centipedes in the family Lithobiidae, commonly called stone centipedes, common centipedes or brown centipedes.

Anatomy

Most ''Lithobius'' species are typical representatives of the family Lithobiidae. They are a ...

s as pioneering, and of a quality unmatched in Chamberlin's later work.

Chamberlin studied not only arthropods but soft-bodied invertebrates as well. He described over 100 new species and 22 new genera of polychaete worms in a two-volume work considered one of the "great monuments" in annelid taxonomy by the former director of the Hopkins Marine Station, and published on Utah's mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is es ...

an fauna. He was section editor on sipunculids

The Sipuncula or Sipunculida (common names sipunculid worms or peanut worms) is a class containing about 162 species of unsegmented marine annelid worms. The name ''Sipuncula'' is from the genus name ''Sipunculus'', and comes from the Latin '' ...

as well as myriapods for the academic journal database Biological Abstracts. William Behle has noted he also made indirect contributions to ornithology, including leading several multi-day specimen collecting trips and guiding the graduate research of Stephen Durrant, who worked on Utah game birds, and Behle himself, who studied nesting birds of the Great Salt Lake

The Great Salt Lake is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth-largest terminal lake in the world. It lies in the northern part of the U.S. state of Utah and has a substantial impact upon the local climate, parti ...

.

After Chamberlin's death, his collection of some 250,000 spider specimens was donated to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, bolstering the museum's status as the world's largest arachnid repository. (reprinted as ) Similarly, his collection of millipedes was deposited in the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., helping to make that museum the world's largest single collection of millipede type specimens—the individual specimens used to describe species.

Great Basin cultural studies

Early in his career, Chamberlin studied the language and habits of indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. He worked with the Goshute band of the Western Shoshone to document their uses of over 300 plants in food, beverages, medicine, and construction materials—their ethnobotany—as well as the names and meanings of plants in theGoshute language

Gosiute is a dialect of the endangered Shoshoni language historically spoken by the Goshute people of the American Great Basin in modern Nevada and Utah. Modern Gosiute speaking communities include the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute Reservat ...

. His resulting publication, "The Ethno-botany of the Gosiute Indians of Utah", is considered the first major ethnobotanical study of a single group of Great Basin peoples. He also published surveys of Goshute animal and anatomical terms, place and personal names, and a compilation of plant names of the Ute people. One of Chamberlin's later colleagues at the University of Utah was Julian Steward, known as the founder of cultural ecology. Steward himself described Chamberlin's work as "splendid", and anthropologist Virginia Kerns writes that Chamberlin's experience with indigenous Great Basin cultures facilitated Steward's own cultural studies: "in terms of ecological knowledge, teward's younger informantsprobably could not match the elders who had instructed Chamberlin. That made his research on Goshute ethnobotany all the more valuable to Steward." Chamberlin gave Goshute-derived names to some of the organisms he described, such as the spider ''Pimoa

''Pimoa'' is a genus of spiders in the family Pimoidae. Its sister genus is '' Nanoa''.

Etymology

''Pimoa'' is derived from the language of the Gosiute people in Utah with the meaning "big legs". The other genera in the family match its ending ...

'', meaning "big legs", and the worm ''Sonatsa

''Sonatsa'' is a genus of marine, mud-dwelling polychaete worms containing the sole species ''Sonatsa meridionalis''. ''S. meridionalis'' was described in 1919 by Ralph Vary Chamberlin from a single specimen collected by the research ship USS ...

'', meaning "many hooks", in the Goshute language.

Other works

Chamberlin's work extended beyond biology and anthropology to include historical, philosophical, and theological writings. At BYU he published several articles in the student newspaper on topics such as

Chamberlin's work extended beyond biology and anthropology to include historical, philosophical, and theological writings. At BYU he published several articles in the student newspaper on topics such as historical criticism

Historical criticism, also known as the historical-critical method or higher criticism, is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts in order to understand "the world behind the text". While often discussed in terms of ...

of the Bible and the relationship of evolutionary theory with religious beliefs. In 1925, he wrote a biography of his brother William H. Chamberlin, a philosopher and theologian who had died several years earlier. Utah philosopher Sterling McMurrin, stated the biography "had a considerable impact" on his own life, and noted "the fact that the book adequately and persuasively presents W. H. Chamberlin's philosophic thought shows the philosophical competence of Ralph Chamberlin" In 1932, Chamberlin wrote "Life in Other Worlds: a Study in the History of Opinion", one of the earliest surveys from ancient to modern times of the concept of cosmic pluralism, the idea that the universe contains multiple inhabited worlds. After retiring in 1948, Chamberlin devoted significant attention to the history of the University of Utah. In 1949 he edited a biographical tribute to John R. Park

John Rockey Park (May 7, 1833 – September 29, 1900) was a prominent educator in the Territory and State of Utah in the late 19th century, and in many ways was the intellectual father of the University of Utah.

Educating "intelligent, industri ...

, an influential Utah educator of the 19th century. Assembled from comments and reflections from Park's own students, ''Memories of John Rockey Park'' was praised by University of Utah English professor B. Roland Lewis, who claimed it "warrants being read by every citizen of tah

TAH, Tah or tah may refer to:

* Taiwan Adventist Hospital, Taipei

* Total artificial heart

* Tahitian language ISO 639 code

* Whitegrass Airport, Tanna, Vanuatu, IATA code

* Jonathan Tah, German footballer

* Trans-African Highway network, Transc ...

" Later in his career, Chamberlin produced an authoritative book, ''The University of Utah, a History of its First Hundred Years,'' which BYU historian Eugene E. Campbell

Eugene Edward "Gene" Campbell (April 26, 1915 – April 10, 1986) was an American professor of history at Brigham Young University.

Biography

Campbell was born and raised in Tooele, Utah, in a working-class Latter-day Saint family, Edward Campb ...

called "an excellent history of this important western institution." ''The University of Utah'' also contains an extensive account of the University of Deseret, the LDS Church-founded university that preceded the University of Utah.

Religious views

Chamberlin was a Mormon, an active member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). He believed that there should be no animosity between religion and science. Stake President George W. McCune described a 1922 meeting in which Chamberlin testified "to the effect that all his labors and researches in the laboratories of science, while very interesting, and to a great extent satisfying to the intellect, did not satisfy the soul of man, and that he yearned for something more," adding Chamberlin "bore testimony that he knew that ours is the true Church of Jesus Christ." University of Oregon doctoral student Tim S. Reid called Chamberlin clearly devout, however, Sterling McMurrin stated "spiders are different from metaphysics, and I think Ralph was not such a devout Mormon."Selected works

Scientific

* * * * (WithWilton Ivie

Vaine Wilton Ivie (March 28, 1907 – August 8, 1969) was an American arachnologist, who described hundreds of new species and many new genera of spiders, both under his own name and in collaboration with Ralph Vary Chamberlin. He was employed b ...

)

* (With Richard L. Hoffman)

Historical & biographical

* * * * * (WithWilliam C. Darrah

__NOTOC__

William Culp Darrah (19091989) was an American professor of biology at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania. He also had an interest in, and published several works on, 19th-century photography.

Born in Reading, Pennsylvania, his was a s ...

and Charles Kelly)

Eponymous taxa

The taxa (e.g. genus or species) named after Chamberlin are listed below, followed by author(s) and year of naming, and taxonomic family. Taxa are listed as originally described: subsequent research may have reassigned taxa or rendered some as invalid

The taxa (e.g. genus or species) named after Chamberlin are listed below, followed by author(s) and year of naming, and taxonomic family. Taxa are listed as originally described: subsequent research may have reassigned taxa or rendered some as invalid synonyms

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

of previously named taxa.

* '' Paeromopus chamberlini'' Brolemann

Henry Wilfred Brolemann (10 July 1860 – 31 July 1933) was a French myriapodologist and former president of the Société entomologique de France known for major works on centipede

Centipedes (from New Latin , "hundred", and Latin , " f ...

, 1922

* ''Tibellus chamberlini

''Tibellus chamberlini'' is a species of running crab spider in the family Philodromidae

Philodromidae, also known as philodromid crab spiders and running crab spiders, is a family of araneomorph spiders first described by Tord Tamerlan Teodor ...

'' Gertsch

Willis John Gertsch (October 4, 1906 – December 12, 1998) was an American arachnologist. He described over 1,000 species of spiders, scorpions, and other arachnids, including the Brown recluse spider and the Tooth cave spider.

Gertsch was born ...

, 1933 ( Philodromidae)

* '' Hivaoa chamberlini'' Berland, 1942 (Tetragnathidae

Long-jawed orb weavers or long jawed spiders (Tetragnathidae) are a family of araneomorph spiders first described by Anton Menge in 1866. They have elongated bodies, legs, and chelicerae, and build small orb webs with an open hub with few, wid ...

)

* '' Euglena chamberlini'' D. T. Jones, 1944 ( Euglenaceae)

* '' Chondrodesmus chamberlini'' Hoffman, 1950 ( Polydesmida, Chelodesmidae

Chelodesmidae, is a millipede family of order Polydesmida. The family includes 219 genera. Two new genera were described in 2012.

Genera

A

*'' Achromoporus''

*'' Afolabina''

*'' Alassodesmus''

*'' Allarithmus''

*'' Alocodesmus''

*''Alys ...

)

* '' Chamberlinia'' Machado, 1951 ( Geophilomorpha, Oryidae)

* ''Haploditha chamberlinorum

''Haploditha'' is a genus of pseudoscorpions in the family Tridenchthoniidae. There is at least one described species in ''Haploditha'', ''H. chamberlinorum''.

References

Further reading

*

*

*

*

*

External links

*

Tride ...

'' Caporiacco, 1951 (Tridenchthoniidae

Chthoniidae is a family of pseudoscorpions within the superfamily Chthonioidea. The family contains more than 600 species in about 30 genera. Fossil species are known from Baltic, Dominican, and Burmese amber.Biology Catalog Chthoniidae now ...

)

* '' Rhinocricus chamberlini'' Schubart, 1951

* ''Chamberlineptus

''Chamberlineptus morechalensis'', the sole species of the genus ''Chamberlineptus'' is a spirostreptid millipede from Venezuela. Individuals are around long and in diameter. ''C. morechalensis'' was described in 1954 by Nell B. Causey, descr ...

'' Causey, 1954 (Spirostreptidae

Spirostreptidae is a family of millipedes in the order Spirostreptida. It contains around 100 genera distributed in North and South America, the eastern Mediterranean, continental Africa, Madagascar, and Seychelles. It contains the following gene ...

)

*''Varyomus

''Varyomus'' is a genus of millipedes

Millipedes are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derived from this feat ...

'' Hoffman, 1954 (Polydesmida, Euryuridae)

* '' Chamberlinius'' Wang, 1956

* ''Haplodrassus chamberlini

''Haplodrassus'' is a genus of ground spiders that was first described by R. V. Chamberlin in 1922. They range from . ''H. signifer'' is the most widespread species, found across North America except for Alaska and northern Canada.

Species

it ...

'' Platnick & Shadab, 1975 ( Gnaphosidae)

* '' Myrmecodesmus chamberlini'' Shear, 1977 (Pyrgodesmidae

Pyrgodesmidae is a family of flat-backed millipedes in the order Polydesmida. The family contains over 200 species distributed in tropics around the world. Some species are found only in ant colonies

An ant colony is a population of a si ...

)

* '' Aphonopelma chamberlini'' Smith, 1995 ( Theraphosidae)

* '' Mallos chamberlini'' Bond & Opell, 1997 ( Dictynidae)

* '' Pyrgulopsis chamberlini'' Hershler, 1998 ( Hydrobiidae)

See also

* Creation–evolution controversy *Ann Chamberlin

Ann Chamberlin is an American writer of historical novels. Her website states that the "purpose of storytelling . . . is to support positions in exact opposition to the views prevailing in a culture's powerhouses, whatever those views happen to b ...

, granddaughter

* Ecology of the Great Basin

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overlaps wi ...

* Great Basin Desert

* Mormon views on evolution

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) takes no official position on whether or not biological evolution has occurred, nor on the validity of the modern evolutionary synthesis as a scientific theory. In the twentieth centur ...

Notes

References

Cited works

* * * *Further reading

* * *External links

Chamberlin's publications on spiders

from the

World Spider Catalog

'

Chamberlin's publications on myriapods

from th

International Society of Myriapodology

at Biodiversity Heritage Library * *

Ralph Vary Chamberlin papers, 1890–1969

an

Ralph Chamberlin photograph collection

(

J. Willard Marriott Library

The J. Willard Marriott Library is the main academic library of the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, Utah. The university library has had multiple homes since the first University of Utah librarian was appointed in 1850. The current building ...

, University of Utah)

Ralph Vary Chamberlin papers, 1940–1967

A Register of the Collection at the Utah State Historical Society {{DEFAULTSORT:Chamberlin, Ralph Vary American ethnographers American arachnologists Arachnologists Ethnobiologists Myriapodologists 1879 births 1967 deaths Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Historians of Utah Brigham Young University faculty Harvard University staff University of Utah faculty University of Pennsylvania faculty Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences alumni University of Utah alumni Scientists from Salt Lake City 20th-century American zoologists Latter Day Saints from Utah