Rajaji on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari (10 December 1878 – 25 December 1972), popularly known as Rajaji or C.R., also known as Mootharignar Rajaji (Rajaji'', the Scholar Emeritus''), was an Indian statesman, writer, lawyer, and independence activist. Rajagopalachari was the last

The Indian National Congress first came to power in the

The Indian National Congress first came to power in the

Some months after the outbreak of the

Some months after the outbreak of the

When India and Pakistan attained independence, the province of Bengal was partitioned into two, with

When India and Pakistan attained independence, the province of Bengal was partitioned into two, with

From 10 until 24 November 1947, Rajagopalachari served as Acting

From 10 until 24 November 1947, Rajagopalachari served as Acting

In the 1952 Madras elections, the Indian National Congress was reduced to a minority in the state assembly with a coalition led by the

In the 1952 Madras elections, the Indian National Congress was reduced to a minority in the state assembly with a coalition led by the

On 26 January 1950, the Government of India adopted

On 26 January 1950, the Government of India adopted

In 1954, during US Vice-president

In 1954, during US Vice-president

Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

, as India became a republic in 1950. He was also the first Indian-born Governor-General, as all previous holders of the post were British nationals. He also served as leader of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

, Premier of the Madras Presidency, Governor of West Bengal, Minister for Home Affairs of the Indian Union and Chief Minister of Madras state. Rajagopalachari founded the Swatantra Party and was one of the first recipients of India's highest civilian award, the Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ''Jewel of India'') is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest orde ...

. He vehemently opposed the use of nuclear weapons and was a proponent of world peace and disarmament. During his lifetime, he also acquired the nickname 'Mango of Salem'.

Rajagopalachari was born in the Thorapalli

Thorapalli or Thorapalli Agraharam is a village in Hosur taluk, Krishnagiri district, Tamil Nadu. It is located on the banks of the Ponnaiyar river about 6 km south-east of Hosur close to the Hosur-Krishnagiri road (National Highway 44), abo ...

village of Hosur

Hosur is an industrial city located in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Hosur is one of the municipal corporations in Tamil Nadu. It is located on the bank of the river River Ponnaiyar, southeast of Bengaluru and west of Chennai, the state ...

taluk in the Krishnagiri district of Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a States and union territories of India, state in southern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of India ...

and was educated at Central College, Bangalore, and Presidency College, Madras. In the 1900s he started legal practice at the Salem court. On entering politics, he became a member and later Chairperson of the Salem

Salem may refer to: Places

Canada

Ontario

* Bruce County

** Salem, Arran–Elderslie, Ontario, in the municipality of Arran–Elderslie

** Salem, South Bruce, Ontario, in the municipality of South Bruce

* Salem, Dufferin County, Ontario, part ...

municipality. One of Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

's earliest political lieutenants, he joined the Indian National Congress and participated in the agitations against the Rowlatt Act, joining the Non-Cooperation movement

The Non-cooperation movement was a political campaign launched on 4 September 1920, by Mahatma Gandhi to have Indians revoke their cooperation from the British government, with the aim of persuading them to grant self-governance.

, the Vaikom Satyagraha, and the Civil Disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". Hen ...

movement. In 1930, Rajagopalachari risked imprisonment when he led the Vedaranyam Salt Satyagraha

The Vedaranyam March (also called the Vedaranyam Satyagraha) was a framework of the nonviolent civil disobedience movement in British India. Modeled on the lines of Dandi March, which was led by Mahatma Gandhi on the western coast of India the ...

in response to the Dandi March

The Salt March, also known as the Salt Satyagraha, Dandi March and the Dandi Satyagraha, was an act of nonviolent civil disobedience in colonial India led by Mahatma Gandhi. The twenty-four day march lasted from 12 March to 6 April 1930 as a di ...

. In 1937, Rajagopalachari was elected Prime minister of the Madras Presidency and served until 1940, when he resigned due to Britain's declaration of war on Germany. He later advocated co-operation over Britain's war effort and opposed the Quit India Movement

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by Mahatma Gandhi on 8th August 1942, during World War II, demanding an end to British rule in ...

. He favoured talks with both Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (, ; born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 – 11 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the ...

and the Muslim League and proposed what later came to be known as the '' C. R. formula''. In 1946, Rajagopalachari was appointed Minister of Industry, Supply, Education and Finance in the Interim Government of India

The Interim Government of India, also known as the Provisional Government of India, formed on 2 September 1946 from the newly elected Constituent Assembly of India, had the task of assisting the transition of British India to independence. It ...

, and then as the Governor of West Bengal from 1947 to 1948, Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

from 1948 to 1950, Union Home Minister

The Minister of Home Affairs (or simply, the Home Minister, short-form HM) is the head of the Ministry of Home Affairs of the Government of India. One of the senior-most officers in the Union Cabinet, the chief responsibility of the Home Minist ...

from 1951 to 1952 and as Chief Minister of Madras state from 1952 to 1954. In 1959, he resigned from the Indian National Congress and founded the Swatantra Party, which fought against the Congress in the 1962

Events January

* January 1 – Western Samoa becomes independent from New Zealand.

* January 3 – Pope John XXIII excommunicates Fidel Castro for preaching communism.

* January 8 – Harmelen train disaster: 93 die in the wors ...

, 1967

Events

January

* January 1 – Canada begins a year-long celebration of the 100th anniversary of Confederation, featuring the Expo 67 World's Fair.

* January 5

** Spain and Romania sign an agreement in Paris, establishing full consular and ...

and 1971 *

The year 1971 had three partial solar eclipses ( February 25, July 22 and August 20) and two total lunar eclipses (February 10, and August 6).

The world population increased by 2.1% this year, the highest increase in history.

Events

Ja ...

elections. Rajagopalachari was instrumental in setting up a united Anti-Congress front in Madras state under C. N. Annadurai, which swept the 1967 elections. He died on 25 December 1972 at the age of 94 and received a state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of Etiquette, protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive ...

.

Rajagopalachari was an accomplished writer who made lasting contributions to Indian English literature

Indian English literature (IEL), also referred to as Indian Writing in English (IWE), is the body of work by writers in India who write in the English language but whose native or co-native language could be one of the numerous languages of India. ...

and is also credited with the composition of the song ''Kurai Onrum Illai

Kurai Onrum Illai ( ta, குறை ஒன்றும் இல்லை, meaning ''No grievances have I'') is a Tamil devotional song written by C. Rajagopalachari. The song set in Carnatic music was written in gratitude to Hindu God (Venkates ...

'' set to Carnatic music

Carnatic music, known as or in the Dravidian languages, South Indian languages, is a system of music commonly associated with South India, including the modern Indian states of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, an ...

. He pioneered temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

*Temperance (group), Canadian danc ...

and temple entry movements in India and advocated Dalit

Dalit (from sa, दलित, dalita meaning "broken/scattered"), also previously known as untouchable, is the lowest stratum of the Caste system in India, castes in India. Dalits were excluded from the four-fold Varna (Hinduism), varna syste ...

upliftment. He has been criticized for introducing the compulsory study of Hindi and the Madras Scheme of Elementary Education in Madras State, dubbed by its critics as Hereditary Education Policy put forward to perpetuate caste hierarchy. Critics have often attributed his pre-eminence in politics to his standing as a favourite of both Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

and Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

. Rajagopalachari was described by Gandhi as the "keeper of my conscience".

Early life

Rajagopalachari was born to Chakravarti Venkatarya Iyengar and his wife Singaramma on 10 December 1878 in Thorapalli village on the outskirts ofHosur

Hosur is an industrial city located in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Hosur is one of the municipal corporations in Tamil Nadu. It is located on the bank of the river River Ponnaiyar, southeast of Bengaluru and west of Chennai, the state ...

, in Dharmapuri taluk, Salem district, Madras Presidency

The Madras Presidency, or the Presidency of Fort St. George, also known as Madras Province, was an administrative subdivision (presidency) of British India. At its greatest extent, the presidency included most of southern India, including the ...

, British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

. His father was the '' munsiff'' of Thorapalli

Thorapalli or Thorapalli Agraharam is a village in Hosur taluk, Krishnagiri district, Tamil Nadu. It is located on the banks of the Ponnaiyar river about 6 km south-east of Hosur close to the Hosur-Krishnagiri road (National Highway 44), abo ...

Village.Bakshi Bakshi may refer to:

Indian title

Bakshi is a historical title used in India, deriving from Persian word for "paymaster", and originating as the title of an official responsible for distributing wages in Muslim armies.

* Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad ...

, p. 1 Rajaji was born in a Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

Tamil Brahmin family belonging to the Srivaishnava

Sri Vaishnavism, or the Sri Vaishnava Sampradaya, is a denomination within the Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism. The name refers to goddess Lakshmi (also known as Sri), as well as a prefix that means "sacred, revered", and the god Vishnu, who ...

sect. The couple already had two sons, Narasimhachari and Srinivasa. Varma et al., p. 50

A weak and sickly child, Rajagopalachari was a constant worry to his parents who feared that he might not live long. As a young child, he was admitted to a village school in Thorapalli

Thorapalli or Thorapalli Agraharam is a village in Hosur taluk, Krishnagiri district, Tamil Nadu. It is located on the banks of the Ponnaiyar river about 6 km south-east of Hosur close to the Hosur-Krishnagiri road (National Highway 44), abo ...

then at the age of five moved with his family to Hosur

Hosur is an industrial city located in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Hosur is one of the municipal corporations in Tamil Nadu. It is located on the bank of the river River Ponnaiyar, southeast of Bengaluru and west of Chennai, the state ...

where Rajagopalachari enrolled at Hosur R.V.Government Boys Higher Secondary School. He passed his matriculation examinations in 1891 and graduated in arts from Central College, Bangalore

Bangalore (), officially Bengaluru (), is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Karnataka. It has a population of more than and a metropolitan population of around , making it the third most populous city and fifth most ...

in 1894. Rajagopalachari also studied law at the Presidency College, Madras, from where he graduated in 1897.

Rajagopalachari married Alamelu Mangalamma in 1897 when she was ten years old and she gave birth to her son a day after her thirteenth birthday. The couple had five children, three sons: C. R. Narasimhan

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari Narasimhan (1909–1989) was an Indian politician, freedom-fighter and member of the Indian Parliament from 1952 to 1962. He was the son of Indian statesman Chakravarti Rajagopalachari.

Early life

Narasimhan was ...

, C. R. Krishnaswamy, and C. R. Ramaswami, and two daughters: Lakshmi Gandhi (''née'' Rajagopalachari) and Namagiri Ammal. Mangamma died in 1916 whereupon Rajagopalachari took sole responsibility for the care of his children. His son Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari Narasimhan was elected to the Lok Sabha from Krishnagiri

Krishnagiri () is a city in the state of Tamil Nadu, India, and it serves as the administrative headquarters of Krishnagiri District formed in 2004. It is located at the bottom of Krishnadevaraya Hills, and the town is fully surrounded by hill ...

in the 1952 and 1957 elections and served as a member of parliament for Krishnagiri from 1952 to 1962. He later wrote a biography of his father. Rajagopalachari's daughter Lakshmi married Devdas Gandhi, son of Mahatma Gandhi while his grandsons include biographer Rajmohan Gandhi

Rajmohan Gandhi (born 7 August 1935) is an Indian biographer, historian, and research professor at the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, US. His paternal grandfather is Mahatma Gandhi, ...

, philosopher Ramchandra Gandhi

Ramchandra Gandhi (9 June 1937 – 13 June 2007) was an Indian philosopher.

He was the son of Devdas Gandhi (Mahatma Gandhi's youngest son) and Lakshmi (daughter of Rajaji) and also brother of Rajmohan Gandhi, Gopalkrishna Gandhi and Tara Gan ...

and former governor of West Bengal

West Bengal (, Bengali: ''Poshchim Bongo'', , abbr. WB) is a state in the eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabitants within an area of . West Bengal is the fourt ...

Gopalkrishna Gandhi. Rajagopalachari's great-grandson, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari Kesavan, is a spokesperson of the Congress Party and Trustee of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee

Tamil Nadu Congress Committee (TNCC) is the wing of Indian National Congress serving in Tamil Nadu. The current president is K.S. Alagari.

Social policy of the TNCC is officially based upon the Gandhian principle of Sarvodaya (upliftment of all ...

.

Indian Independence Movement

Rajagopalachari's interest in public affairs and politics began when he commenced his legal practice inSalem

Salem may refer to: Places

Canada

Ontario

* Bruce County

** Salem, Arran–Elderslie, Ontario, in the municipality of Arran–Elderslie

** Salem, South Bruce, Ontario, in the municipality of South Bruce

* Salem, Dufferin County, Ontario, part ...

in 1900. At the age of 28, he joined the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

and participated as a delegate in the 1906 Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

session. Inspired by Indian independence activist Bal Gangadhar Tilak

Bal Gangadhar Tilak (; born Keshav Gangadhar Tilak (pronunciation: eʃəʋ ɡəŋɡaːd̪ʱəɾ ʈiɭək; 23 July 1856 – 1 August 1920), endeared as Lokmanya (IAST: ''Lokmānya''), was an Indian nationalist, teacher, and an independence a ...

, Varma et al., p. 52 he later became a member of the Salem municipality in 1911. In 1917, he was elected chairman of the municipality and served from 1917 to 1919 during which time he was responsible for the election of the first Dalit

Dalit (from sa, दलित, dalita meaning "broken/scattered"), also previously known as untouchable, is the lowest stratum of the Caste system in India, castes in India. Dalits were excluded from the four-fold Varna (Hinduism), varna syste ...

member of the Salem municipality. In 1917, he defended Indian independence activist P. Varadarajulu Naidu

Perumal Varadarajulu Naidu (4 June 1887 – 23 July 1957) was an Indian physician, politician, journalist and Indian independence activist. He was also the founder of The Indian Express, a major English-language daily, in 1932 in Madras. He was ...

against charges of sedition Ralhan, p. 34 and two years later participated in the agitations against the Rowlatt Act. Rajagopalachari was a close friend of the founder of Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company

The Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company (SSNC) was one of the first indigenous Indian shipping companies set up during the Indian independence movement. It was started in 1906 by V. O. Chidambaram Pillai to compete against the monopoly of the Brit ...

V. O. Chidambaram Pillai

''V.'' is the debut novel of Thomas Pynchon, published in 1963. It describes the exploits of a discharged U.S. Navy sailor named Benny Profane, his reconnection in New York with a group of pseudo-bohemian artists and hangers-on known as the Whol ...

as well as greatly admired by Indian independence activists Annie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

, Subramania Bharati

C. Subramania Bharathi Birth name: C. Subramaniyan, the person's given name: Subramaniyan, father's given name: Chinnaswami. (C. Subramaniyan by the prevalent patronymic initials as prefix naming system in Tamil Nadu and it is Subramaniyan C ...

and C. Vijayaraghavachariar

Chakravarti Vijayaraghavachariar (18 June 1852 – 19 April 1944) was an Indian politician. He rose to prominence following his appeal against the false charges alleging him to have instigated a Hindu – Muslim riot in Salem (now in Tamil Nadu ...

.

After Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

joined the Indian independence movement in 1919, Rajagopalachari became one of his followers. He participated in the Non-Cooperation movement and gave up his law practice. In 1921, he was elected to the Congress Working Committee and served as the General Secretary of the party before making his first major breakthrough as a leader during the 1922 Indian National Congress session at Gaya

Gaya may refer to:

Geography Czech Republic

*Gaya (German and Latin), Kyjov (Hodonín District), a town

Guinea

* Gaya or Gayah, a town

India

*Gaya, India, a city in Bihar

**Gaya Airport

*Bodh Gaya, a town in Bihar near Gaya

*Gaya district, Bi ...

when he strongly opposed collaboration with the colonial administration and participation in the diarchial legislatures established by the Government of India Act 1919. While Gandhi was in prison, Rajagopalachari led the group of "No-Changers", individuals against contesting elections for the Imperial Legislative Council

The Imperial Legislative Council (ILC) was the legislature of the British Raj from 1861 to 1947. It was established under the Charter Act of 1853 by providing for the addition of 6 additional members to the Governor General Council for legislativ ...

and other provincial legislative councils, in opposition to the "Pro-changers" who advocated council entry. When the motion was put to the vote, the "No-changers" won by 1,748 to 890 votes resulting in the resignation of important Congress leaders including Pandit Motilal Nehru

Motilal Nehru (6 May 1861 – 6 February 1931) was an Indian lawyer, activist and politician belonging to the Indian National Congress. He also served as the Congress President twice, 1919–1920 and 1928–1929. He was a patriarch of the Nehr ...

and C. R. Das, the President of the Indian National Congress. When the Indian National Congress split in 1923, Rajagopalachari was a member of the Civil Disobedience Enquiry Committee. He was also involved in the Vaikom Satyagraha movement against untouchability

Untouchability is a form of social institution that legitimises and enforces practices that are discriminatory, humiliating, exclusionary and exploitative against people belonging to certain social groups. Although comparable forms of discrimin ...

during 1924–25. In a public speech on May 27, 1924, he reassured the anxious upper caste Hindus in Vaikom, "Mahatmaji does not want the caste system abolished but holds that untouchability should be abolished...Mahatmaji does not want you to dine with the Thiyyas

The Ezhavas () are a community with origins in the region of India presently known as Kerala, where in the 2010s they constituted about 23% of the population and were reported to be the largest Hindu community. They are also known as ''Ilhava'' ...

or the Pulayas

The Pulayar (also Pulaya, Pulayas, Cherumar, Cheramar, and Cheraman) is a caste group mostly found in the southern part of India, forming one of the main social groups in modern-day Kerala, Karnataka and historically in Tamil Nadu.

Traditio ...

. What he wants is that we must be prepared to go near or touch other human beings as you go near a cow

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

or a horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million y ...

".

In the early 1930s, Rajagopalachari emerged as one of the major leaders of the Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a States and union territories of India, state in southern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of India ...

Congress. When Gandhi organised the Dandi march in 1930, Rajagopalachari broke the salt laws at Vedaranyam, near Nagapattinam

Nagapattinam (''nākappaṭṭinam'', previously spelt Nagapatnam or Negapatam) is a town in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Nagapattinam District. The town came to prominence during the period of Medieval ...

, along with Indian independence activist Sardar Vedaratnam. Rajagopalachari was sentenced to six-months of rigorous imprisonment and was sent to the Trichinopoly Central Prison. He was subsequently elected President of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee. Following the enactment of the Government of India Act in 1935, Rajagopalachari was instrumental in getting the Indian National Congress to participate in the 1937 general elections.

Madras Presidency 1937–39

The Indian National Congress first came to power in the

The Indian National Congress first came to power in the Madras Presidency

The Madras Presidency, or the Presidency of Fort St. George, also known as Madras Province, was an administrative subdivision (presidency) of British India. At its greatest extent, the presidency included most of southern India, including the ...

(also called Madras Province by the British), following the Madras elections of 1937. Except for a six-year period when Madras was under the Governor's direct rule, the Congress administered the Madras Presidency

The Madras Presidency, or the Presidency of Fort St. George, also known as Madras Province, was an administrative subdivision (presidency) of British India. At its greatest extent, the presidency included most of southern India, including the ...

until India became independent on 15 August 1947 as the Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

. Encyclopedia of Political Parties, p. 199 At the age of 59, Rajagopalachari won the Madras University seat and entered the Assembly as the first Premier of the Madras Presidency from the Congress party.

In 1938, when Dalit members of the Madras Legislative Council

Tamil Nadu Legislative Council was the upper house of the former bicameral legislature of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It began its existence as Madras Legislative Council, the first provincial legislature for Madras Presidency. It was initia ...

proposed a Temple Entry Bill, Congress Chief Minister Rajagopalachari asked them to withdraw it. Rajagopalachari issued the Temple Entry Authorization and Indemnity Act 1939, under which restrictions were removed on Dalits

Dalit (from sa, दलित, dalita meaning "broken/scattered"), also previously known as untouchable, is the lowest stratum of the castes in India. Dalits were excluded from the four-fold varna system of Hinduism and were seen as forming ...

and Shanars

Nadar (also referred to as ''Nadan'', ''Shanar'' and ''Shanan'') is a Tamil caste of India. Nadars are predominant in the districts of Kanyakumari, Thoothukudi, Tirunelveli and Virudhunagar.

The Nadar com ...

entering Hindu temples. Kothari, p. 116 In the same year, the Meenakshi temple at Madurai was also opened to the Dalits and Shanars. In March 1938, Rajagopalachari introduced the Agricultural Debt Relief Act, to ease the burden of debt on the province's peasant population.

He also introduced prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

,Bakshi Bakshi may refer to:

Indian title

Bakshi is a historical title used in India, deriving from Persian word for "paymaster", and originating as the title of an official responsible for distributing wages in Muslim armies.

* Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad ...

, p. 149 along with a sales tax to compensate for the loss of government revenue that resulted from the ban on alcohol. The Provincial Government shut down hundreds of government-run primary schools, citing lack of funds. His opponents said that this deprived many low-caste and Dalit students of their education. His opponents also attributed casteist motives to his government's implementation of Gandhi's Nai Talim scheme into the education system.

Rajagopalachari's tenure as Chief Minister of Madras

The chief minister of Tamil Nadu is the head of government, chief executive of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. In accordance with the Constitution of India, the Governors of states of India, governor is a state's ''de jure'' head, bu ...

is largely remembered for the compulsory introduction of Hindi in educational institutions, which made him highly unpopular. This measure sparked off widespread anti-Hindi protests, which led to violence in some places and the jailing of over 1,200 men, women and children who took part in the unrest. Two protesters, Thalamuthu Nadar and Natarasan, were killed during the protests. Dravidar Kazhagam founder Periyar E.V. Ramasamy opposed the decision of C. Rajagopalachari to make learning Hindi compulsory in schools in 1937. During the anti-Hindi agitations, Rajagopalachari was constantly identified as an enemy and destroyer of Tamil thai

Tamil Thai () refers to the allegorical and sometimes anthropomorphic personification of the Tamil language as a mother. This allegory of the Tamil language in the persona of a mother was established during the Tamil renaissance movement of the ...

. The opposition to Rajagopalachari grew because he continued to openly criticize the Anti-Hindi agitation of 1937–40 in the most elitist terms and casually ignored the death of a young protester in 1938 when he was asked about it.

In 1940, Congress ministers resigned in protest over the declaration of war on Germany without their consent, leaving the governor to take over the reins of the administration. On 21 February 1940, the unpopular new law on the use of Hindi was quickly repealed by the Governor of Madras. Despite its numerous shortcomings, Madras under Rajagopalachari was still considered by political historians as the best-administered province in British India.

Second World War

Some months after the outbreak of the

Some months after the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Rajagopalachari resigned as premier along with other members of his cabinet in protest at the declaration of war by the Viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

. Rajagopalachari was arrested in December 1940, in accordance with the Defence of India rules, and sentenced to one year in prison. However, subsequently, Rajagopalachari differed in opposition to the British war effort. He also opposed the Quit India Movement

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by Mahatma Gandhi on 8th August 1942, during World War II, demanding an end to British rule in ...

and instead advocated dialogue with the British. He reasoned that passivity and neutrality would be harmful to India's interests at a time when the country was threatened with invasion. He also advocated dialogue with the Muslim League, which was demanding the partition of India. He subsequently resigned from the party and the assembly following differences over resolutions passed by the Madras Congress legislative party and disagreements with the leader of the Madras provincial Congress K. Kamaraj

Kumaraswami Kamaraj (15 July 1903 – 2 October 1975, hinduonnet.com. 15–28 September 2001), popularly known as Kamarajar was an Indian independence activist and politician who served as the Chief Minister of Madras State (Tamil Nadu) ...

.

Following the end of the war in 1945, elections followed in the Madras Presidency in 1946. During the last years of the war, Kamaraj was requested by Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar, was an Indian lawyer, influential political leader, barrister and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of I ...

and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al-Hussaini Azad (; 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following Ind ...

to make Rajagopalachari the Premier of Madras Presidency. Kamaraj, President of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee, was forced to make Tanguturi Prakasam as Chief Ministerial candidate, by the elected members, to prevent Rajagopalachari from winning. However, Rajagopalachari did not contest the elections, and Prakasam was elected.

Rajagopalachari was instrumental in initiating negotiations between Gandhi and Jinnah. In 1944, he proposed a solution to the Indian Constitutional tangle. In the same year, he proposed an "absolute majority" threshold of 55 per cent when deciding whether a district should become part of India or Pakistan, triggering a huge controversy among nationalists.

From 1946 to 1947, Rajagopalachari served as the Minister for Industry, Supply, Education, and Finance in the Interim Government headed by Jawaharlal Nehru.

Governor of West Bengal 1947–1948

When India and Pakistan attained independence, the province of Bengal was partitioned into two, with

When India and Pakistan attained independence, the province of Bengal was partitioned into two, with West Bengal

West Bengal (, Bengali: ''Poshchim Bongo'', , abbr. WB) is a state in the eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabitants within an area of . West Bengal is the fourt ...

becoming part of India and East Bengal

ur,

, common_name = East Bengal

, status = Province of the Dominion of Pakistan

, p1 = Bengal Presidency

, flag_p1 = Flag of British Bengal.svg

, s1 = East ...

part of Pakistan. At that time, Rajagopalachari was appointed as the first Governor of West Bengal.Ghose Ghose is a surname, and may refer to:

* Ajoy Ghose, Indian mining engineer

* Anindya Ghose (born c. 1974), Indian-born American business academic

* Arundhati Ghose (1939–2016), Indian diplomat

* Aurobindo Ghose or Ghosh, known as Sri Aurobindo (1 ...

, p. 331

Disliked by the Bengali political class for his criticism of Subhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose ( ; 23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*) was an Indian nationalist whose defiance of British authority in India made him a hero among Indians, but his wartime alliances with Nazi Germany and Imperia ...

during the 1939 Tripuri Congress

This year also marks the start of the Second World War, the largest and deadliest conflict in human history.

Events

Below, the events of World War II have the "WWII" prefix.

January

* January 1

** Third Reich

*** Jews are forbidden to ...

session, Rajagopalachari's appointment as Governor of West Bengal was protested by Bose's brother Sarat Chandra Bose. During his tenure as governor, Rajagopalachari's priorities were to deal with refugees and to bring peace and stability in the aftermath of the Calcutta riots. He declared his commitment to neutrality and justice at a meeting of Muslim businessmen: "Whatever may be my defects or lapses, let me assure you that I shall never disfigure my life with any deliberate acts of injustice to any community whatsoever." Rajagopalachari was also strongly opposed to proposals to include areas from Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West Be ...

and Odisha

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of ...

as part of the province of West Bengal. One such proposal by the editor of a newspaper led to the reply:

"I see that you are not able to restrain the policy of agitation over inter-provincial boundaries. It is easy to yield to the current pressure of opinion and it is difficult to impose on enthusiastic people any policy of restraint. But I earnestly plead that we should do all we can to prevent ill-will from hardening into a chronic disorder. We have enough ill-will and prejudice to cope with. Must we hasten to create further fissiparous forces?"Despite the general attitude of the Bengali political class, Rajagopalachari was highly regarded and respected by Chief Minister

Prafulla Chandra Ghosh

Prafulla Chandra Ghosh (24 December 1891 – 18 December 1983) was the first Premier of West Bengal, India from 15 August 1947 to 14 August 1948. He also served as the Chief Minister of West Bengal in the "Progressive Democratic Alliance Fron ...

and his ministry.

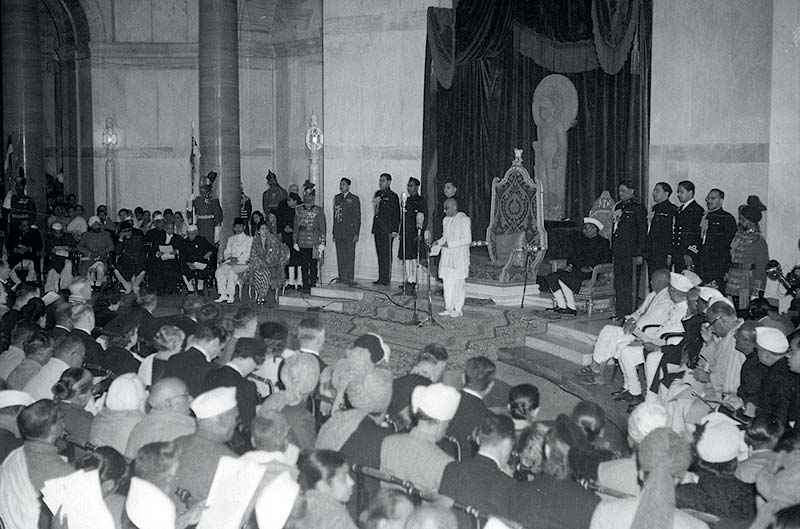

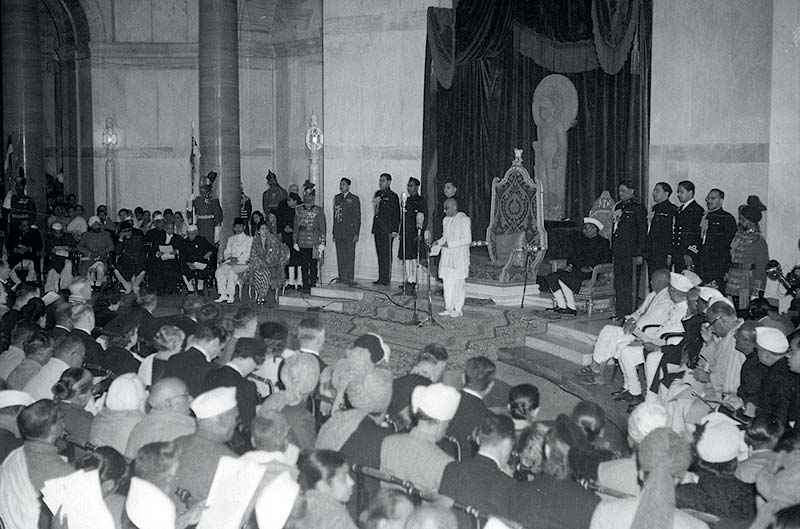

Governor-General of India 1948–1950

From 10 until 24 November 1947, Rajagopalachari served as Acting

From 10 until 24 November 1947, Rajagopalachari served as Acting Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

in the absence of the Governor-General Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

, who was on leave in England to attend the marriage of Princess Elizabeth to Mountbatten's nephew Prince Philip. Rajagopalachari led a very simple life in the viceregal palace, washing his own clothes and polishing his own shoes. Kesavan, p. 36 Impressed with his abilities, Mountbatten made Rajagopalachari his second choice to succeed him after Vallabhbhai Patel, when he was to leave India in June 1948. Rajagopalachari was eventually chosen as the governor-general when Nehru disagreed with Mountbatten's first choice, as did Patel himself. He was initially hesitant but accepted when Nehru wrote to him, "I hope you will not disappoint us. We want you to help us in many ways. The burden on some of us is more than we can carry." Rajagopalachari then served as Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

from June 1948 until 26 January 1950 and was not only the last Governor-General of India but the only Indian citizen ever to hold the office.

By the end of 1949, an assumption was made that Rajagopalachari, already Governor-General, would continue as president. Backed by Nehru, Rajagopalachari wanted to stand for the presidential election but later withdrew, Guha, p 47 due to the opposition of a section of the Indian National Congress mostly made up of North India

North India is a loosely defined region consisting of the northern part of India. The dominant geographical features of North India are the Indo-Gangetic Plain and the Himalayas, which demarcate the region from the Tibetan Plateau and Central ...

ns who were concerned about Rajagopalachari's non-participation during the Quit India Movement. Ralhan, p 31 Gandhi, p. 309. "Why was the party not keen on C. R., whose success as Governor-General had been unquestioned? That he came from outside the Hindi belt and was not fluent in the language were perhaps factors. 'The protagonists of Hindi favour Rajendra Prasad', Nehru told Patel. But the biggest reason was C. R.'s 1942 role."

Role in Constituent Assembly

He was elected to theConstituent Assembly of India

The Constituent Assembly of India was elected to frame the Constitution of India. It was elected by the 'Provincial Assembly'. Following India's independence from the British rule in 1947, its members served as the nation's first Parliament as ...

from Madras. He was a part of Advisory Committee and Sub-Committee on Minorities. He debated on issues relating to rights of religious denominations.

In Nehru's Cabinet

At Nehru's invitation, in 1950, Rajagopalachari joined the Union Cabinet asMinister without Portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet w ...

where he served as a buffer between Nehru and Home Minister Sardar Patel and on occasion offered to mediate between the two. Following Patel's death on 15 December 1950, Rajagopalachari was finally made Home Affairs Minister and went on to serve for nearly 10 months. As had his predecessor, he warned Nehru about the expansionist designs of China and expressed regret over the Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

problem. He also expressed concern over demands for new linguistically based states, arguing that they would generate differences amongst the people.

By the end of 1951, the differences between Nehru and Rajagopalachari came to the fore. While Nehru perceived the Hindu Mahasabha

The Hindu Mahasabha (officially Akhil Bhārat Hindū Mahāsabhā, ) is a Hindu nationalist political party in India.

Founded in 1915, the Mahasabha functioned mainly as a pressure group advocating the interests of orthodox Hindus before the B ...

to be the greatest threat to the nascent republic, Rajagopalachari held the opinion that the Communists posed the greatest danger. Zachariah, p. 185 He also adamantly opposed Nehru's decision to commute the death sentences passed on those involved in the Telangana uprising

The Telangana Rebellion popularly known as Telangana Sayuda Poratam (Telugu : తెలంగాణ సాయుధ పోరాటం) of 1946–51 was a communist-led insurrection of peasants against the princely state of Hyderabad in the r ...

and his strong pro-Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

leanings. Zachariah, p. 186 Tired of being persistently over-ruled by Nehru concerning critical decisions, Rajagopalachari submitted his resignation on the "grounds of ill-health" and returned to Madras.Ghose Ghose is a surname, and may refer to:

* Ajoy Ghose, Indian mining engineer

* Anindya Ghose (born c. 1974), Indian-born American business academic

* Arundhati Ghose (1939–2016), Indian diplomat

* Aurobindo Ghose or Ghosh, known as Sri Aurobindo (1 ...

, p. 332

Madras State 1952–1954

In the 1952 Madras elections, the Indian National Congress was reduced to a minority in the state assembly with a coalition led by the

In the 1952 Madras elections, the Indian National Congress was reduced to a minority in the state assembly with a coalition led by the Communist Party of India

Communist Party of India (CPI) is the oldest Marxist–Leninist communist party in India and one of the nine national parties in the country. The CPI was founded in modern-day Kanpur (formerly known as Cawnpore) on 26 December 1925.

H ...

winning most of the seats. The Congress did not want the Communists taking power or to impose Governor's rule in the state. It brought Rajagopalachari out of retirement to form the government as a consensus candidate. On 31 March 1952, Kamaraj presented a resolution, proposing the election of Rajagopalachari as the leader of the Madras Legislature Congress party. The resolution was approved by the party and Kamaraj revealed that Rajagopalachari had been reluctant to accept the responsibility as Chief Minister and the leader of the Madras Legislature Congress party as his health was fragile and added that by acceding to the request of the party, Rajagopalachari had put country before self. Rajagopalachari did not contest the by-election and on 10 April 1952, Madras Governor Sri Prakasa

Sri Prakasa (3 August 1890 – 23 June 1971) was an Indian politician, freedom-fighter and administrator. He served as India's first High Commissioner to Pakistan from 1947 to 1949, Governor of Assam from 1949 to 1950, Governor of Madras from ...

appointed him as Chief Minister by nomination as MLC without consulting either the Prime Minister Nehru or the ministers in the Madras state cabinet. Reddy, p. 24 Reddy, p. 25 It was the first time when the governor office was accused of acting inappropriately after independence. P. C. Alexander

Padinjarethalakal Cherian Alexander (20 March 1921 – 10 August 2011) was an Indian Administrative Service officer of 1948 batch who served as the Governor of Tamil Nadu from 1988 to 1990 and as the Governor of Maharashtra from 1993 to 2002. H ...

, a former governor of Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra wrote about the appointment of Rajagopalachari as "The most conspicuous case of constitutional impropriety by the Governor in the exercise of discretion to choose the Chief Minister..."

On 3 July 1952, Rajagopalachari was then able to prove that he had a majority in the assembly by luring MLAs

The Max Launch Abort System (MLAS) was a proposed alternative to the Maxime Faget-invented "tractor" launch escape system (LES) that was planned for use by NASA for its Orion (spacecraft), Orion spacecraft in the event an Ares I malfunction du ...

from opposition parties and independents to join the Indian National Congress. 19 members of the Tamil Nadu Toilers Party led by S. S. Ramasami Padayachi

S. S. Ramasami Padayatchiyar (16 September 1918 – 3 April 1992) was a politician from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. He was the founder of the Tamil political party Tamil Nadu Toilers' Party, which is considered to be a predecessor of Patta ...

, 5 members of the Madras State Muslim League

The Indian Union Muslim League (abbreviated as the I. U. M. L. or the League) is an Indian political party primarily based in the Indian state of Kerala. It is recognised as a State Party in Kerala by the Election Commission of India.

The first ...

and 6 members of Commonweal Party also provided their support to Rajagopalachari to prevent the Communists from gaining power. Nehru was furious and wrote to Rajagopalachari saying "the one thing we must avoid giving is the impression that we stick to office and we want to keep others out at all costs." Rajagopalachari, however, refused to contest a by-election and remained as a nominated member of the Legislative Council.

During Rajagopalachari's tenure as Chief Minister, a powerful movement for a separate Andhra State, comprising the Telugu

Telugu may refer to:

* Telugu language, a major Dravidian language of India

*Telugu people, an ethno-linguistic group of India

* Telugu script, used to write the Telugu language

** Telugu (Unicode block), a block of Telugu characters in Unicode

S ...

-speaking districts of the Madras State

Madras State was a state of India during the mid-20th century. At the time of its formation in 1950, it included the whole of present-day Tamil Nadu (except Kanyakumari district), Coastal Andhra, Rayalaseema, the Malabar region of North and c ...

, gained a foothold. On 19 October 1952, an Indian independence activist and social worker from Madras named Potti Sriramulu

Potti Sreeramulu (IAST: ''Poṭṭi Śreerāmulu''; 16 March 1901 – 15 December 1952), was an Indian freedom fighter and revolutionary. Sreeramulu is revered as ''Amarajeevi'' ("Immortal Being") in the Andhra region for his self-sacrifice for ...

embarked on a hunger strike reiterating the demands of the separatists and calling for the inclusion of Madras city within the proposed state. Rajagopalachari remained unmoved by Sriramulu's action and refused to intervene. After fasting for days, Sriramulu eventually died on 15 December 1952, triggering riots in Madras city and the Telugu-speaking districts of the state. Initially, both Rajagopalachari and Prime Minister Nehru were against the creation of linguistically demarcated states but as the law and order situation in the state deteriorated, both were forced to accept the demands. Andhra State was thus created on 1 October 1953 from the Telugu-speaking districts of Madras, with its capital at Kurnool

Kurnool is a city in the state of Andhra Pradesh, India. It formerly served as the capital of Andhra State (1953–1956). The city is often referred to as "The Gateway of Rayalaseema".Kurnool is also known as The City of Gem Stones. It also se ...

. However, the boundaries of the new state were determined by a commission which decided against the inclusion of Madras city. Though the commission's report suggested the option of having Madras as the temporary capital of Andhra State to allow smooth partitioning of the assets and the secretariat, Rajagopalachari refused to allow Andhra State to have Madras even for a day.

On 7 June 1952, Rajagopalachari ended the procurement policy and food rationing in the state, abolishing all price and quota controls. His decision was a rejection of a planned economy in favour of a free market economy. He also introduced measures to regulate the running of universities in the state.

In 1953, he introduced a new education scheme known as the "Modified Scheme of Elementary education 1953

The Modified Scheme of Elementary Education or New Scheme of Elementary Education or Madras Scheme of Elementary Education dubbed by its critics as Kula Kalvi Thittam (Hereditary Education Policy), was an abortive attempt at education reform intro ...

", which reduced schooling for elementary school students from five hours to three hours per day and suggested that boys to learn the family crafts from their father and girls housekeeping from their mothers. Rajaji had not even consulted his own cabinet or members of the legislative assembly before the scheme's implementation. He said: “Did Shankara or Ramanuja

Ramanuja (Middle Tamil: Rāmāṉujam; Classical Sanskrit: Rāmanuja; 1017 CE – 1137 CE; ; ), also known as Ramanujacharya, was an Indian Hindu philosopher, guru and a social reformer. He is noted to be one of the most important exponents o ...

announce their philosophy after consulting others?". The scheme came in for sharp criticism and evoked strong protests from the Dravidian parties. Two amendments were proposed against the scheme at the Madras State legislative assembly. One advocated for a study by an expert group, while another advocated for the scheme's abolition. Both sides launched publicity campaigns in June 1953. At the Adyar riverside, Rajaji made a speech to the washermen. He stated kuladharma, or each clan's or caste's social obligation. He delivered talks and made radio broadcasts to clarify his views. The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (; DMK) is a political party based in the state of Tamil Nadu where it is currently the ruling party having a comfortable majority without coalition support and the union territory of Puducherry where it is curre ...

dubbed the scheme ''Kula Kalvi Thittam'' or Hereditary Education Policy

The Modified Scheme of Elementary Education or New Scheme of Elementary Education or Madras Scheme of Elementary Education dubbed by its critics as Kula Kalvi Thittam (Hereditary Education Policy), was an abortive attempt at education reform intro ...

which was put forward with the intention of perpetuating the caste system. and attempted to organize massive demonstrations outside Rajagopalachari's house on 13 and 14 July 1953. The scheme was criticized from political leaders from all sides as casteist. Opponents and critics claimed that the system would reinforce deep-seated, caste-based inequality in society. They regarded the plan as an attempt to place children from the upper caste in an advantageous place than children from oppressed groups, who were simply supposed to learn their father's job. Rajagopalachari argued, It is a mistake to imagine that the school is within the walls. The whole village is a school. The village polytechnic is there, every branch of it, the dhobi, the wheelwright, the cobbler.The Scheme was stayed by the house and the Parulekar Committee was commissioned to review the scheme. The committee found the scheme to be sound and endorsed the Government's position. India's President Rajendra Prasad and Prime Minister

Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

also offered their support to the scheme.

Rajagopalachari closed down 6000 schools, citing financial constraints. Kamaraj opposed this policy and eventually opened 12,000 schools in his tenure.

Despite his government's efforts to postpone the Modified Scheme of Elementary Education 1953

The Modified Scheme of Elementary Education or New Scheme of Elementary Education or Madras Scheme of Elementary Education dubbed by its critics as Kula Kalvi Thittam (Hereditary Education Policy), was an abortive attempt at education reform intro ...

, public resistance grew, particularly in response to initiatives that sought to establish Hindi as the national language. The rising unpopularity of his government forced Rajagopalachari to resign on 26 March 1954, as the President of the Madras Congress Legislature Party (CLP) thereby precipitating new elections. Kamaraj's name was proposed by P. Varadarajalu Naidu for the post of CLP leader. M. Bakthavatsalam

Minjur Bhakthavatsalam (9 October 1897 – 13 February 1987) was an Indian independence activist and politician who served as the chief minister of Madras State from 2 October 1963 to 6 March 1967. He was the last Congress chief minister of Ta ...

, another senior Congress leader, fielded C. Subramaniam. On 30 March 1954, the election took place, Subramaniam could garner only 41 votes to Kamaraj's 93 and lost the elections. Rajagopalachari eventually resigned as Chief Minister on 13 April 1954, attributing the decision to poor health.

Split from Congress – parting of ways

Following his resignation as Chief Minister, Rajagopalachari took a temporary break from active politics and instead devoted his time to literary pursuits. He wrote a Tamil re-telling of the Sanskrit epic ''Ramayana

The ''Rāmāyana'' (; sa, रामायणम्, ) is a Sanskrit literature, Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epic composed over a period of nearly a millennium, with scholars' estimates for the earliest stage of the text ranging from the 8th ...

'' which appeared as a serial in the Tamil magazine '' Kalki'' from 23 May 1954 to 6 November 1955. The episodes were later collected and published as ''Chakravarthi Thirumagan'', a book which won Rajagopalachari the 1958 Sahitya Academy award

Events

January

* January 1 – The European Economic Community (EEC) comes into being.

* January 3 – The West Indies Federation is formed.

* January 4

** Edmund Hillary's Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition completes the third ...

in Tamil language

Tamil (; ' , ) is a Dravidian language natively spoken by the Tamil people of South Asia. Tamil is an official language of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, the sovereign nations of Sri Lanka and Singapore, and the Indian territory of Pudu ...

. Varma et al., p. 68

Rajagopalachari tendered his official resignation from the Indian National Congress and along with a number of other dissidents organised the Congress Reform Committee

{{Use Indian English, date=July 2020

The Congress Reform Committee (CRC) was formed by a group of dissidents that left the Indian National Congress in the Madras State. The CRC was led by C. Rajagopalachari, who had been defeated by Kamaraj in the ...

(CRC) in January 1957. K. S. Venkatakrishna Reddiar

K. S. Venkatakrishna Reddiar (1909 – 14 January 1966) was an Indian politician and activist of the cooperative movement. He served as President of the short-lived Congress Reform Committee from 1957 to 1959.

Early life

Born in South Arcot, ...

was elected president and the party fielded candidates in 55 constituencies in the 1957 state assembly elections, to emerge as the second largest party in Madras state with 13 seats in the legislative assembly. The Congress Reform Committee also contested 12 Lok Sabha

The Lok Sabha, constitutionally the House of the People, is the lower house of India's bicameral Parliament, with the upper house being the Rajya Sabha. Members of the Lok Sabha are elected by an adult universal suffrage and a first-past ...

seats during the 1957 Indian elections. The committee became a fully-fledged political party and was renamed the Indian National Democratic Congress

{{Use Indian English, date=July 2020

The Congress Reform Committee (CRC) was formed by a group of dissidents that left the Indian National Congress in the Madras State. The CRC was led by C. Rajagopalachari, who had been defeated by Kamaraj in the ...

at a state conference held in Madurai

Madurai ( , also , ) is a major city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is the cultural capital of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Madurai District. As of the 2011 census, it was the third largest Urban agglomeration in ...

on September 28–29, 1957.

On 4 June 1959, shortly after the Nagpur session of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

, Rajagopalachari, along with Murari Vaidya Murari () is an epithet of the Hindu deity Krishna, referring to his act of slaying the asura, Mura.

Murari may also refer to:

People

* Murari (author) (approx. 9th century AD), Sanskrit dramatic poet and author of ''Anargharāghava''

* Sarvesh Mu ...

of the newly established Forum of Free Enterprise (FFE)Erdman Erdman is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew L. Erdman (born 1965), American author, journalist, and scholar

* Charles Erdman Petersdorff (1800–1886), legal writer

* Charles R. Erdman Sr. (1866–1960), American Presbyte ...

, p. 66 and Minoo Masani

Minocher Rustom "Minoo" Masani (20 November 1905 – 27 May 1998) was an Indian politician, a leading figure of the erstwhile Swatantra Party. He was a three-time Member of Parliament, representing Gujarat's Rajkot constituency in the second, ...

, a classical liberal and critic of socialist Nehru, announced the formation of the new Swatantra Party at a meeting in Madras.Erdman Erdman is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew L. Erdman (born 1965), American author, journalist, and scholar

* Charles Erdman Petersdorff (1800–1886), legal writer

* Charles R. Erdman Sr. (1866–1960), American Presbyte ...

, p. 65 Conceived by disgruntled heads of former princely states such as the Raja of Ramgarh

Ramgarh Raj was the major ''Zamindari'' estate in the era of the British Raj in the former Indian province of Bihar.

Territories which comprised the Ramgarh Raj presently constitute districts of Ramgarh, Hazaribagh,

Chatra, Giridih, Koderma, ...

, the Maharaja of Kalahandi

Mahārāja (; also spelled Maharajah, Maharaj) is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king" or " high king".

A few ruled states informally called empires, including ruler raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, an ...

and the Maharajadhiraja of Darbhanga, the party was conservative in character.Erdman Erdman is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew L. Erdman (born 1965), American author, journalist, and scholar

* Charles Erdman Petersdorff (1800–1886), legal writer

* Charles R. Erdman Sr. (1866–1960), American Presbyte ...

, p. 74Erdman Erdman is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew L. Erdman (born 1965), American author, journalist, and scholar

* Charles Erdman Petersdorff (1800–1886), legal writer

* Charles R. Erdman Sr. (1866–1960), American Presbyte ...

, p. 72 Later, N. G. Ranga

Gogineni Ranga Nayukulu (7 November 1900 – 9 June 1995), also known as N. G. Ranga, was an Indian freedom fighter, classical liberal, parliamentarian and farmers' leader. He was the founding president of the Swatantra Party, and an exponen ...

, K. M. Munshi

Kanhaiyalal Maneklal Munshi (; 30 December 1887 – 8 February 1971), popularly known by his pen name Ghanshyam Vyas, was an Indian independence movement activist, politician, writer and educationist from Gujarat state. A lawyer by profession, ...

, Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

K. M. Cariappa

'

Field Marshal Kodandera Madappa Cariappa (28 January 1899 – 15 May 1993) was the first Indian Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the Indian Army. He led Indian forces on the Western Front during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947. He was appoin ...

and the Maharaja of Patiala

The Maharaja of Patiala was a maharaja in India and the ruler of the princely state of Patiala, a state in British India. The first Maharaja of Patiala was Baba Ala Singh (1695–1765).

Yadavindra Singh became the maharaja on 23 March 1938. H ...

joined the effort. Rajagopalachari, Masani and Ranga also tried but failed to involve Jayaprakash Narayan in the initiative.Erdman Erdman is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew L. Erdman (born 1965), American author, journalist, and scholar

* Charles Erdman Petersdorff (1800–1886), legal writer

* Charles R. Erdman Sr. (1866–1960), American Presbyte ...

, p. 78

In his short essay "Our Democracy", Rajagopalachari explained the necessity for a right-wing alternative to the Congress by saying:

since... the Congress Party has swung to the Left, what is wanted is not an ultra or outer-Left iz. the CPI or the Praja Socialist Party, PSP">Praja_Socialist_Party.html" ;"title="iz. the CPI or the Praja Socialist Party">iz. the CPI or the Praja Socialist Party, PSP but a strong and articulate RightRajagopalachari also insisted that the opposition must:

operate not privately and behind the closed doors of the party meeting, but openly and periodically through the electorate.He outlined the goals of the Swatantra Party through twenty one "fundamental principles" in the foundation document.

Erdman Erdman is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew L. Erdman (born 1965), American author, journalist, and scholar

* Charles Erdman Petersdorff (1800–1886), legal writer

* Charles R. Erdman Sr. (1866–1960), American Presbyte ...

, p. 188 The party stood for equality and opposed government control over the private sector.Erdman Erdman is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew L. Erdman (born 1965), American author, journalist, and scholar

* Charles Erdman Petersdorff (1800–1886), legal writer

* Charles R. Erdman Sr. (1866–1960), American Presbyte ...

, p. 189Erdman Erdman is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrew L. Erdman (born 1965), American author, journalist, and scholar

* Charles Erdman Petersdorff (1800–1886), legal writer

* Charles R. Erdman Sr. (1866–1960), American Presbyte ...

, p. 190 Rajagopalachari sharply criticised the bureaucracy and coined the term " licence-permit Raj" to describe Nehru's elaborate system of permissions and licences required for an individual to set up a private enterprise. Rajagopalachari's personality became a rallying point for the party.

In 1961, Rajagopalachari criticized Operation Vijay, the Indian military action in which Portuguese rule in Goa">Annexation of Goa">Operation Vijay, the Indian military action in which Portuguese rule in Goa was forcibly ended and the territory was incorporated into India, writing that India had "totally lost the moral power to raise her voice against militarism" and had undermined the power and prestige of the United Nations Security Council. According to Rajagopalachari, while Portuguese rule in Goa had been an "offense to Indian nationalism", it was not a greater offense than the Chinese occupation of territories claimed by India or the social evil of untouchability

Untouchability is a form of social institution that legitimises and enforces practices that are discriminatory, humiliating, exclusionary and exploitative against people belonging to certain social groups. Although comparable forms of discrimin ...

, and the "great adventure" of seizing Goa undermined India's devotion to Gandhian principles of non-violence.

Rajagopalachari's efforts to build an anti-Congress front led to a patch up with his former adversary C. N. Annadurai of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (; DMK) is a political party based in the state of Tamil Nadu where it is currently the ruling party having a comfortable majority without coalition support and the union territory of Puducherry where it is curre ...

. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Annadurai grew close to Rajagopalachari and sought an alliance with the Swatantra Party for the 1962 Madras legislative assembly elections. Although there were occasional electoral pacts between the Swatantra Party and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (; DMK) is a political party based in the state of Tamil Nadu where it is currently the ruling party having a comfortable majority without coalition support and the union territory of Puducherry where it is curre ...

(DMK), Rajagopalachari remained non-committal on a formal tie-up with the DMK due to its existing alliance with Communists whom he dreaded. The Swatantra Party contested 94 seats in the Madras state assembly elections and won six as well as won 18 parliamentary seats in the 1962 Lok Sabha elections.

1965 Anti-Hindi agitations in Madras

On 26 January 1950, the Government of India adopted

On 26 January 1950, the Government of India adopted Hindi

Hindi (Devanāgarī: or , ), or more precisely Modern Standard Hindi (Devanagari: ), is an Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in the Hindi Belt region encompassing parts of northern, central, eastern, and western India. Hindi has been de ...

as the official language of the country, but because of objections in non-Hindi-speaking areas, it introduced a provision tentatively making English the second official language on a par with Hindi for a stipulated fifteen-year period to facilitate a switch to Hindi in non-Hindi speaking states. From 26 January 1965 onwards, Hindi was to become the sole official language of the Indian Union and people in non-Hindi speaking regions were compelled to learn Hindi. This led to vehement opposition and just before Republic Day, severe anti-Hindi protests broke out in Madras State. Rajagopalachari had earlier been sharply critical of the recommendations made by the Official Languages Commission in 1957.Ghose Ghose is a surname, and may refer to:

* Ajoy Ghose, Indian mining engineer

* Anindya Ghose (born c. 1974), Indian-born American business academic

* Arundhati Ghose (1939–2016), Indian diplomat

* Aurobindo Ghose or Ghosh, known as Sri Aurobindo (1 ...

, p. 218 On 28 January 1956, Rajagopalachari signed a resolution along with Annadurai and Periyar endorsing the continuation of English as the official language. At an All-India Language Conference held on 8 March 1958, he declared: "Hindi is as much foreign to non-Hindi speaking people as English sto the protagonists of Hindi". When the Anti-Hindi agitations broke out in 1965, Rajagopalachari completely reversed his 1938 support for the introduction of Hindi and took a strongly anti-Hindi stand in support of the protests, coining the slogan ‘English Ever, Hindi Never’. On 17 January 1965, he convened the Madras state Anti-Hindi conference in Tiruchirapalli. angrily declaring that Part XVII of the Constitution of India

Part XVII is a compilation of laws pertaining to the constitution of India as a country and the union of states that it is made of. This part of the constitution consists of Articles on Official Language.

Chapter I - Official Language of the ...

which declared that Hindi was the official language should "be heaved and thrown into the Arabian Sea."

1967 elections

The fourth elections to the Madras Legislative assembly were held in February 1967. At the age of 88, Rajagopalachari worked to forge a united opposition to the Indian National Congress through a tripartite alliance between theDravida Munnetra Kazhagam

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (; DMK) is a political party based in the state of Tamil Nadu where it is currently the ruling party having a comfortable majority without coalition support and the union territory of Puducherry where it is curre ...

, the Swatantra Party and the Forward Bloc

The All India Forward Bloc ( AIFB) is a left-wing nationalist political party in India. It emerged as a faction within the Indian National Congress in 1939, led by Subhas Chandra Bose. The party re-established as an independent political party a ...

. The Congress party was defeated in Madras for the first time in 30 years and the coalition led by Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam came to power. C. N. Annadurai served as Chief Minister from 6 March 1967 until his death on 3 February 1969. Rajagopalachari delivered a moving eulogy to Annadurai at his funeral.

The Swatantra Party also did well in elections in other states and to the Lok Sabha

The Lok Sabha, constitutionally the House of the People, is the lower house of India's bicameral Parliament, with the upper house being the Rajya Sabha. Members of the Lok Sabha are elected by an adult universal suffrage and a first-past ...

, the directly elected lower house

A lower house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house. Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has co ...

of the Parliament of India

The Parliament of India (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, IAST: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Republic of India. It is a bicameralism, bicameral legislature composed of the president of India and two houses: the R ...

. It won 45 Lok Sabha seats in the 1967 general elections and emerged as the single largest opposition party. The principal opposition party in the states of Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern si ...

and Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the ninth ...

, it also formed a coalition government

A coalition government is a form of government in which political parties cooperate to form a government. The usual reason for such an arrangement is that no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election, an atypical outcome in ...

in Odisha

Odisha (English: , ), formerly Orissa ( the official name until 2011), is an Indian state located in Eastern India. It is the 8th largest state by area, and the 11th largest by population. The state has the third largest population of ...

and had a significant presence in Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh (, abbr. AP) is a state in the south-eastern coastal region of India. It is the seventh-largest state by area covering an area of and tenth-most populous state with 49,386,799 inhabitants. It is bordered by Telangana to the ...

, Tamil Nadu and Bihar

Bihar (; ) is a state in eastern India. It is the 2nd largest state by population in 2019, 12th largest by area of , and 14th largest by GDP in 2021. Bihar borders Uttar Pradesh to its west, Nepal to the north, the northern part of West Be ...

.

Later years and death

In 1971, Annadurai's successorM. Karunanidhi

Muthuvel Karunanidhi (3 June 1924 – 7 August 2018) was an Indian writer and politician who served as Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu for almost two decades over five terms between 1969 and 2011. He was popularly referred to as Kalaignar (Art ...

relaxed prohibition laws in Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a States and union territories of India, state in southern India. It is the List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of India ...

due to the poor financial situation of the state. Rajagopalachari pleaded with him not to repeal prohibition but to no avail and as a result, the Swatantra Party withdrew its support for the state government Ralhan, p. 32 and instead allied with the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

, a breakaway faction of the Indian National Congress led by Kamaraj.

In January 1971, a three-party anti-Congress coalition was established by the Congress (O), Jan Sangh

The Bharatiya Jana Sangh ( BJS or JS, short name: Jan Sangh, full name: Akhil Bharatiya Jana Sangh; ) (ISO 15919: '' Akhila Bhāratīya Jana Saṅgha '' ) was an Indian right wing political party that existed from 1951 to 1977 and was the pol ...

and the Samyukta Socialist Party

Samyukta Socialist Party (; SSP), was a political party in India from 1964 to 1972. SSP was formed through a split in the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) in 1964. In 1972, SSP was reunited with PSP, forming the Socialist Party.

The General Secret ...

then on 8 January, the national executive of the Swatantra Party took the unanimous decision to join the coalition. The dissident parties formed an alliance called the National Democratic Front and fought against the Indian National Congress led by Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (; Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and a central figure of the Indian National Congress. She was elected as third prime minister of India in 1966 ...

in the 1971 Indian general election