RNA Enzyme on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are

Before the discovery of ribozymes,

Before the discovery of ribozymes,

Tom Cech's Short Talk: "Discovering Ribozymes"

{{Portal bar, Biology RNA Catalysts Biomolecules * Metabolism Chemical kinetics RNA splicing

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

molecules that have the ability to catalyze specific biochemical reactions, including RNA splicing

RNA splicing is a process in molecular biology where a newly-made precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) transcript is transformed into a mature messenger RNA (mRNA). It works by removing all the introns (non-coding regions of RNA) and ''splicing'' b ...

in gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. The ...

, similar to the action of protein enzymes

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecule ...

. The 1982 discovery of ribozymes demonstrated that RNA can be both genetic material (like DNA) and a biological catalyst

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

(like protein enzymes), and contributed to the RNA world hypothesis

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

, which suggests that RNA may have been important in the evolution of prebiotic self-replicating systems. The most common activities of natural or in vitro-evolved ribozymes are the cleavage or ligation of RNA and DNA and peptide bond formation. For example, the smallest ribozyme known (GUGGC-3') can aminoacylate a GCCU-3' sequence in the presence of PheAMP. Within the ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

, ribozymes function as part of the large subunit ribosomal RNA to link amino acids during protein synthesis

Protein biosynthesis (or protein synthesis) is a core biological process, occurring inside Cell (biology), cells, homeostasis, balancing the loss of cellular proteins (via Proteolysis, degradation or Protein targeting, export) through the product ...

. They also participate in a variety of RNA processing

Transcriptional modification or co-transcriptional modification is a set of biological processes common to most eukaryotic cells by which an RNA primary transcript is chemically altered following transcription from a gene to produce a mature, f ...

reactions, including RNA splicing

RNA splicing is a process in molecular biology where a newly-made precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) transcript is transformed into a mature messenger RNA (mRNA). It works by removing all the introns (non-coding regions of RNA) and ''splicing'' b ...

, viral replication

Viral replication is the formation of biological viruses during the infection process in the target host cells. Viruses must first get into the cell before viral replication can occur. Through the generation of abundant copies of its genome an ...

, and transfer RNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

biosynthesis. Examples of ribozymes include the hammerhead ribozyme

The hammerhead ribozyme is an RNA motif that catalyzes reversible cleavage and ligation reactions at a specific site within an RNA molecule. It is one of several catalytic RNAs (ribozymes) known to occur in nature. It serves as a model system for ...

, the VS ribozyme

The Varkud satellite (VS) ribozyme is an RNA enzyme that carries out the cleavage of a phosphodiester bond.

Introduction

Varkud satellite (VS) ribozyme is the largest known nucleolytic ribozyme and found to be embedded in VS RNA. VS RNA is a long ...

, Leadzyme

Leadzyme is a small ribozyme (catalytic RNA), which catalyzes the cleavage of a specific phosphodiester bond. It was discovered using an in-vitro evolution study where the researchers were selecting for RNAs that specifically cleaved themselves in ...

and the hairpin ribozyme

The hairpin ribozyme is a small section of RNA that can act as a ribozyme. Like the hammerhead ribozyme it is found in RNA satellites of plant viruses. It was first identified in the minus strand of the tobacco ringspot virus (TRSV) satellite R ...

.

Researchers who are investigating the origins of life

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothes ...

through the RNA world

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

hypothesis have been working on discovering a ribozyme which has the capacity to self-replicate, which would require it to have the ability to catalytically synthesize polymers of RNA. This should be able to happen in prebiotically plausible conditions with high rates of copying accuracy to prevent degradation of information but also allowing for the occurrence of occasional errors during the copying process to allow for Darwinian evolution

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that ...

to proceed.

Attempts have been made to develop ribozymes as therapeutic agents, as enzymes which target defined RNA sequences for cleavage, as biosensor

A biosensor is an analytical device, used for the detection of a chemical substance, that combines a biological component with a physicochemical detector.

The ''sensitive biological element'', e.g. tissue, microorganisms, organelles, cell recep ...

s, and for applications in functional genomics

Functional genomics is a field of molecular biology that attempts to describe gene (and protein) functions and interactions. Functional genomics make use of the vast data generated by genomic and transcriptomic projects (such as genome sequencing ...

and gene discovery.

Discovery

Before the discovery of ribozymes,

Before the discovery of ribozymes, enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s, which are defined as catalytic protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s, were the only known biological catalysts

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

. In 1967, Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese (; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal RNA, ...

, Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical struc ...

, and Leslie Orgel

Leslie Eleazer Orgel FRS (12 January 1927 – 27 October 2007) was a British chemist. He is known for his theories on the origin of life.

Biography

Leslie Orgel was born in London, England, on . He received his Bachelor of Arts degree in chemi ...

were the first to suggest that RNA could act as a catalyst. This idea was based upon the discovery that RNA can form complex secondary structure

Protein secondary structure is the three dimensional conformational isomerism, form of ''local segments'' of proteins. The two most common Protein structure#Secondary structure, secondary structural elements are alpha helix, alpha helices and beta ...

s. These ribozymes were found in the intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e. a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gene. ...

of an RNA transcript, which removed itself from the transcript, as well as in the RNA component of the RNase P complex, which is involved in the maturation of pre-tRNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

s. In 1989, Thomas R. Cech

Thomas Robert Cech (born December 8, 1947) is an American chemist who shared the 1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Sidney Altman, for their discovery of the catalytic properties of RNA. Cech discovered that RNA could itself cut strands of RNA, ...

and Sidney Altman

Sidney Altman (May 7, 1939 – April 5, 2022) was a Canadian-American molecular biologist, who was the Sterling Professor of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology and Chemistry at Yale University. In 1989, he shared the Nobel Prize in ...

shared the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

for their "discovery of catalytic properties of RNA." The term ''ribozyme'' was first introduced by Kelly Kruger ''et al.'' in 1982 in a paper published in ''Cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

''.

It had been a firmly established belief in biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

that catalysis was reserved for proteins. However, the idea of RNA catalysis is motivated in part by the old question regarding the origin of life: Which comes first, enzymes that do the work of the cell or nucleic acids that carry the information required to produce the enzymes? The concept of "ribonucleic acids as catalysts" circumvents this problem. RNA, in essence, can be both the chicken and the egg.

In the 1980s Thomas Cech, at the University of Colorado at Boulder

The University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder, CU, or Colorado) is a public research university in Boulder, Colorado. Founded in 1876, five months before Colorado became a state, it is the flagship university of the University of Colorado sys ...

, was studying the excision of introns

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e. a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gene. ...

in a ribosomal RNA gene in ''Tetrahymena

''Tetrahymena'', a Unicellular organism, unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrah ...

thermophila''. While trying to purify the enzyme responsible for the splicing reaction, he found that the intron could be spliced out in the absence of any added cell extract. As much as they tried, Cech and his colleagues could not identify any protein associated with the splicing reaction. After much work, Cech proposed that the intron sequence portion of the RNA could break and reform phosphodiester

In chemistry, a phosphodiester bond occurs when exactly two of the hydroxyl groups () in phosphoric acid react with hydroxyl groups on other molecules to form two ester bonds. The "bond" involves this linkage . Discussion of phosphodiesters is d ...

bonds. At about the same time, Sidney Altman, a professor at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, was studying the way tRNA molecules are processed in the cell when he and his colleagues isolated an enzyme called RNase-P, which is responsible for conversion of a precursor tRNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

into the active tRNA. Much to their surprise, they found that RNase-P contained RNA in addition to protein and that RNA was an essential component of the active enzyme. This was such a foreign idea that they had difficulty publishing their findings. The following year, Altman demonstrated that RNA can act as a catalyst by showing that the RNase-P RNA subunit could catalyze the cleavage of precursor tRNA into active tRNA in the absence of any protein component.

Since Cech's and Altman's discovery, other investigators have discovered other examples of self-cleaving RNA or catalytic RNA molecules. Many ribozymes have either a hairpin – or hammerhead – shaped active center and a unique secondary structure that allows them to cleave other RNA molecules at specific sequences. It is now possible to make ribozymes that will specifically cleave any RNA molecule. These RNA catalysts may have pharmaceutical applications. For example, a ribozyme has been designed to cleave the RNA of HIV. If such a ribozyme were made by a cell, all incoming virus particles would have their RNA genome cleaved by the ribozyme, which would prevent infection.

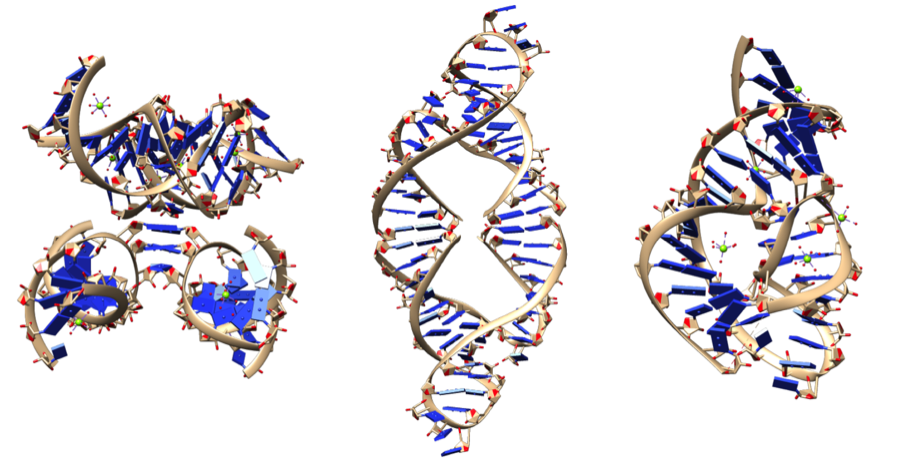

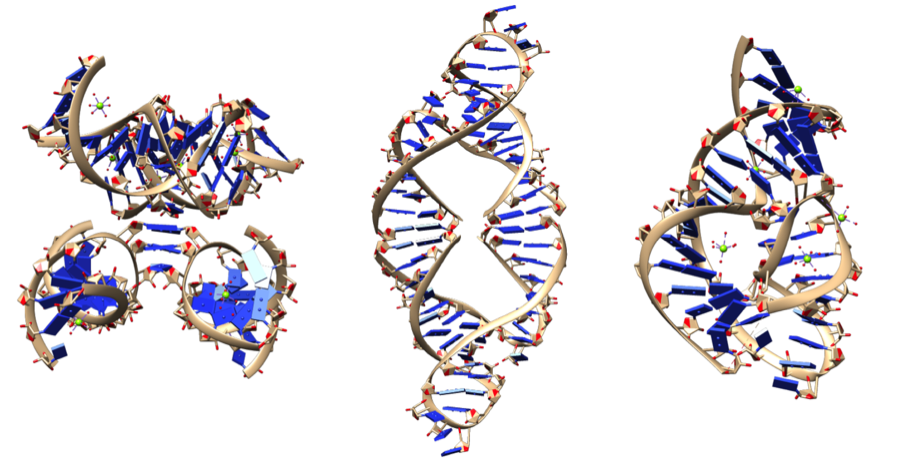

Structure and mechanism

Despite having only four choices for each monomer unit (nucleotides), compared to 20 amino acid side chains found in proteins, ribozymes have diverse structures and mechanisms. In many cases they are able to mimic the mechanism used by their protein counterparts. For example, in self cleaving ribozyme RNAs, an in-line SN2 reaction is carried out using the 2’ hydroxyl group as a nucleophile attacking the bridging phosphate and causing 5’ oxygen of the N+1 base to act as a leaving group . In comparison, RNase A, a protein that catalyzes the same reaction, uses a coordinating histidine and lysine to act as a base to attack the phosphate backbone. Like many protein enzymes metal binding is also critical to the function of many ribozymes. Often these interactions use both the phosphate backbone and the base of the nucleotide, causing drastic conformational changes. There are two mechanism classes for the cleavage of phosphodiester backbone in the presence of metal. In the first mechanism, the internal 2’- OH group attacks phosphorus center in a SN2 mechanism. Metal ions promote this reaction by first coordinating the phosphate oxygen and later stabling the oxyanion. The second mechanism also follows a SN2 displacement, but the nucleophile comes from water or exogenous hydroxyl groups rather than RNA itself. The smallest ribozyme is UUU, which can promote the cleavage between G and A of the GAAA tetranucleotide via the first mechanism in the presence of Mn2+. The reason why this trinucleotide rather than the complementary tetramer catalyze this reaction may be because the UUU-AAA pairing is the weakest and most flexible trinucleotide among the 64 conformations, which provides the binding site for Mn2+. Phosphoryl transfer can also be catalyzed without metal ions. For example, pancreatic ribonuclease A and hepatitis delta virus(HDV) ribozymes can catalyze the cleavage of RNA backbone through acid-base catalysis without metal ions. Hairpin ribozyme can also catalyze the self-cleavage of RNA without metal ions but the mechanism is still unclear. Ribozyme can also catalyze the formation of peptide bond between adjacent amino acid by lowering the activation entropy.

Activities

Although ribozymes are quite rare in most cells, their roles are sometimes essential to life. For example, the functional part of theribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

, the biological machine

A molecular machine, nanite, or nanomachine is a molecular component that produces quasi-mechanical movements (output) in response to specific stimuli (input). In cellular biology, macromolecular machines frequently perform tasks essential for l ...

that translates

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

RNA into proteins, is fundamentally a ribozyme, composed of RNA tertiary structural motifs that are often coordinated to metal ions such as Mg2+ as cofactors. In a model system, there is no requirement for divalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with other atoms when it forms chemical compounds or molecules.

Description

The combining capacity, or affinity of an ...

cations

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

in a five-nucleotide RNA catalyzing ''trans''- phenylalanation of a four-nucleotide substrate with 3 base pairs complementary with the catalyst, where the catalyst/substrate were devised by truncation of the C3 ribozyme.

The best-studied ribozymes are probably those that cut themselves or other RNAs, as in the original discovery by Cech and Altman. However, ribozymes can be designed to catalyze a range of reactions (see below), many of which may occur in life but have not been discovered in cells.

RNA may catalyze folding

Fold, folding or foldable may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Fold'' (album), the debut release by Australian rock band Epicure

*Fold (poker), in the game of poker, to discard one's hand and forfeit interest in the current pot

*Above ...

of the pathological protein conformation

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers specifically polypeptides formed from sequences of amino acids, the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monomer may ...

of a prion

Prions are misfolded proteins that have the ability to transmit their misfolded shape onto normal variants of the same protein. They characterize several fatal and transmissible neurodegenerative diseases in humans and many other animals. It ...

in a manner similar to that of a chaperonin

HSP60, also known as chaperonins (Cpn), is a family of heat shock proteins originally sorted by their 60kDa molecular mass. They prevent misfolding of proteins during stressful situations such as high heat, by assisting protein folding. HSP60 bel ...

.

Ribozymes and the origin of life

RNA can also act as a hereditary molecule, which encouragedWalter Gilbert

Walter Gilbert (born March 21, 1932) is an American biochemist, physicist, molecular biology pioneer, and Nobel laureate.

Education and early life

Walter Gilbert was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on March 21, 1932, the son of Emma (Cohen), a ...

to propose that in the distant past, the cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

used RNA as both the genetic material and the structural and catalytic molecule rather than dividing these functions between DNA and protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

as they are today; this hypothesis is known as the "RNA world hypothesis

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

" of the origin of life

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothes ...

. Since nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

s and RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

and thus ribozymes can arise by inorganic chemicals, they are candidates for the first enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s, and in fact, the first "replicators", i.e. information-containing macro-molecules that replicate themselves. An example of a self-replicating ribozyme that ligates two substrates to generate an exact copy of itself was described in 2002.

The discovery of catalytic activity of RNA solved the "chicken and egg" paradox of the origin of life, solving the problem of origin of peptide and nucleic acid central dogma. According to this scenario, at the origin of life

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothes ...

all enzymatic activity and genetic information encoding was done by one molecule, the RNA.

Ribozymes have been produced in the laboratory

A laboratory (; ; colloquially lab) is a facility that provides controlled conditions in which scientific or technological research, experiments, and measurement may be performed. Laboratory services are provided in a variety of settings: physicia ...

that are capable of catalyzing the synthesis of other RNA molecules from activated monomer

In chemistry, a monomer ( ; ''mono-'', "one" + '' -mer'', "part") is a molecule that can react together with other monomer molecules to form a larger polymer chain or three-dimensional network in a process called polymerization.

Classification

Mo ...

s under very specific conditions, these molecules being known as RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

ribozymes. The first RNA polymerase ribozyme was reported in 1996, and was capable of synthesizing RNA polymers up to 6 nucleotides in length. Mutagenesis

Mutagenesis () is a process by which the genetic information of an organism is changed by the production of a mutation. It may occur spontaneously in nature, or as a result of exposure to mutagens. It can also be achieved experimentally using la ...

and selection has been performed on an RNA ligase ribozyme from a large pool of random RNA sequences, resulting in isolation of the improved "Round-18" polymerase ribozyme in 2001 which could catalyze RNA polymers now up to 14 nucleotides in length. Upon application of further selection on the Round-18 ribozyme, the B6.61 ribozyme was generated and was able to add up to 20 nucleotides

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules w ...

to a primer template in 24 hours, until it decomposes by cleavage of its phosphodiester bonds.

The rate at which ribozymes can polymerize an RNA sequence multiples substantially when it takes place within a micelle.

The next ribozyme discovered was the "tC19Z" ribozyme, which can add up to 95 nucleotides

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules w ...

with a fidelity of 0.0083 mutations/nucleotide. Next, the "tC9Y" ribozyme was discovered by researchers and was further able to synthesize RNA strands up to 206 nucleotides long in the eutectic phase conditions at below-zero temperature, conditions previously shown to promote ribozyme polymerase activity.

The RNA polymerase ribozyme (RPR) called tC9-4M was able to polymerize RNA chains longer than itself (i.e. longer than 177 nt) in magnesium ion concentrations close to physiological levels, whereas earlier RPRs required prebiotically implausible concentrations of up to 200mM. The only factor required for it to achieve this was the presence of a very simple amino acid polymer, lysine decapeptide.

The most complex RPR synthesized by that point was called 24-3, which was newly capable of polymerizing the sequences of a substantial variety of nucleotide sequences and navigating through complex secondary structures of RNA substrates inaccessible to previous ribozymes. In fact, this experiment was the first to use a ribozyme to synthesize a tRNA molecule. Starting with the 24-3 ribozyme, Tjhung et al. applied another fourteen rounds of selection to obtain an RNA polymerase ribozyme by ''in vitro'' evolution termed '38-6' that has an unprecedented level of activity in copying complex RNA molecules. However, this ribozyme is unable to copy itself and its RNA products have a high mutation rate

In genetics, the mutation rate is the frequency of new mutations in a single gene or organism over time. Mutation rates are not constant and are not limited to a single type of mutation; there are many different types of mutations. Mutation rates ...

. In a subsequent study, the researchers began with the 38-6 ribozyme and applied another 14 rounds of selection to generate the '52-2' ribozyme, which compared to 38-6, was again many times more active and could begin generating detectable and functional levels of the class I ligase, although it was still limited in its fidelity and functionality in comparison to copying of the same template by proteins such as the T7 RNA polymerase.

An RPR called t5(+1) adds triplet nucleotides at a time instead of just one nucleotide at a time. This heterodimeric RPR can navigate secondary structures inaccessible to 24-3, including hairpins. In the initial pool of RNA variants derived only from a previously synthesized RPR known as the Z RPR, two sequences separately emerged and evolved to be mutualistically dependent on each other. The Type 1 RNA evolved to be catalytically inactive, but complexing with the Type 5 RNA boosted its polymerization ability and enabled intermolecular interactions with the RNA template substrate obviating the need to tether the template directly to the RNA sequence of the RPR, which was a limitation of earlier studies. Not only did t5(+1) not need tethering to the template, but a primer was not needed either as t5(+1) had the ability to polymerize a template in both 3' → 5' and 5' 3 → 3' directions.

A highly evolved RNA polymerase ribozyme was able to function as a reverse transcriptase

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genomes, ...

, that is, it can synthesize a DNA copy using an RNA template. Such an activity is considered to have been crucial for the transition from RNA to DNA genomes during the early history of life on earth. Reverse transcription capability could have arisen as a secondary function of an early RNA dependent RNA polymerase ribozyme.

An RNA sequence that folds into a ribozyme capable of invading duplexed RNA, rearranging into an open holopolymerase complex and then searching for a specific RNA promoter sequence, and upon recognition rearrange again into a processive form that polymerizes a complementary strand of the sequence. This ribozyme is capable of extending duplexed RNA by up to 107 nucleotides, and does so without needing to tether the sequence being polymerized.

Artificial ribozymes

Since the discovery of ribozymes that exist in living organisms, there has been interest in the study of new synthetic ribozymes made in the laboratory. For example, artificially-produced self-cleaving RNAs that have good enzymatic activity have been produced. Tang and Breaker isolated self-cleaving RNAs by in vitro selection of RNAs originating from random-sequence RNAs. Some of the synthetic ribozymes that were produced had novel structures, while some were similar to the naturally occurring hammerhead ribozyme. In 2015, researchers atNorthwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

and the University of Illinois

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U of I, Illinois, University of Illinois, or UIUC) is a public land-grant research university in Illinois in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana. It is the flagship institution of the University ...

at Chicago have engineered a tethered ribosome that works nearly as well as the authentic cellular component that produces all the proteins and enzymes within the cell. Called Ribosome-T, or Ribo-T, the artificial ribosome was created by Michael Jewett and Alexander Mankin. The techniques used to create artificial ribozymes involve directed evolution. This approach takes advantage of RNA's dual nature as both a catalyst and an informational polymer, making it easy for an investigator to produce vast populations of RNA catalysts using polymerase

A polymerase is an enzyme ( EC 2.7.7.6/7/19/48/49) that synthesizes long chains of polymers or nucleic acids. DNA polymerase and RNA polymerase are used to assemble DNA and RNA molecules, respectively, by copying a DNA template strand using base- ...

enzymes. The ribozymes are mutated by reverse transcribing them with reverse transcriptase

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genomes, ...

into various cDNA

In genetics, complementary DNA (cDNA) is DNA synthesized from a single-stranded RNA (e.g., messenger RNA (mRNA) or microRNA (miRNA)) template in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme reverse transcriptase. cDNA is often used to express a speci ...

and amplified with error-prone PCR

In molecular biology, mutagenesis is an important laboratory technique whereby DNA mutations are deliberately genetic engineering, engineered to produce Library (biology), libraries of mutant genes, proteins, strains of bacteria, or other geneti ...

. The selection parameters in these experiments often differ. One approach for selecting a ligase ribozyme

The RNA Ligase ribozyme was the first of several types of synthetic ribozymes produced by in vitro evolution and selection techniques. They are an important class of ribozymes because they catalyze the assembly of RNA fragments into phosphodiest ...

involves using biotin

Biotin (or vitamin B7) is one of the B vitamins. It is involved in a wide range of metabolic processes, both in humans and in other organisms, primarily related to the utilization of fats, carbohydrates, and amino acids. The name ''biotin'', bor ...

tags, which are covalently

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

linked to the substrate. If a molecule possesses the desired ligase

In biochemistry, a ligase is an enzyme that can catalyze the joining (ligation) of two large molecules by forming a new chemical bond. This is typically via hydrolysis of a small pendant chemical group on one of the larger molecules or the enzym ...

activity, a streptavidin

Streptavidin is a 66.0 (tetramer) kDa protein purified from the bacterium '' Streptomyces avidinii''. Streptavidin homo-tetramers have an extraordinarily high affinity for biotin (also known as vitamin B7 or vitamin H). With a dissociation co ...

matrix can be used to recover the active molecules.

Lincoln and Joyce used ''in vitro'' evolution to develop ribozyme ligases capable of self-replication in about an hour, via the joining of pre-synthesized highly complementary oligonucleotides.

Although not true catalysts, the creation of artificial self-cleaving riboswitches, termed aptazymes, has also been an active area of research. Riboswitches

In molecular biology, a riboswitch is a regulatory segment of a messenger RNA molecule that binds a small molecule, resulting in a change in Translation (biology), production of the proteins encoded by the mRNA. Thus, an mRNA that contains a ribo ...

are regulatory RNA motifs that change their structure in response to a small molecule ligand to regulate translation. While there are many known natural riboswitches that bind a wide array of metabolites and other small organic molecules, only one ribozyme based on a riboswitch has been described, ''glmS''. Early work in characterizing self-cleaving riboswitches was focused on using theophylline

Theophylline, also known as 1,3-dimethylxanthine, is a phosphodiesterase inhibiting drug used in therapy for respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma under a variety of brand names. As a member of the ...

as the ligand. In these studies an RNA hairpin is formed which blocks the ribosome binding site A ribosome binding site, or ribosomal binding site (RBS), is a sequence of nucleotides upstream of the start codon of an mRNA transcript that is responsible for the recruitment of a ribosome during the initiation of translation. Mostly, RBS refers t ...

, thus inhibiting translation. In the presence of the ligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule (functional group) that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's electr ...

, in these cases theophylline, the regulatory RNA region is cleaved off, allowing the ribosome to bind and translate the target gene. Much of this RNA engineering work was based on rational design and previously determined RNA structures rather than directed evolution as in the above examples. More recent work has broadened the ligands used in ribozyme riboswitches to include thymine pyrophosphate (2). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Flow cytometry (FC) is a technique used to detect and measure physical and chemical characteristics of a population of cells or particles.

In this process, a sample containing cells or particles is suspended in a fluid and injected into the flo ...

has also been used to engineering aptazymes.

Applications

Ribozymes have been proposed and developed for the treatment of disease through gene therapy (3). One major challenge of using RNA based enzymes as a therapeutic is the short half-life of the catalytic RNA molecules in the body. To combat this, the 2’ position on the ribose is modified to improve RNA stability. One area of ribozyme gene therapy has been the inhibition of RNA-based viruses. A type of synthetic ribozyme directed againstHIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of ''Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the immune ...

RNA called gene shears has been developed and has entered clinical testing for HIV infection.

Similarly, ribozymes have been designed to target the hepatitis C virus RNA, SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Adenovirus and influenza A and B virus RNA. The ribozyme is able to cleave the conserved regions of the virus's genome which has been shown to reduce the virus in mammalian cell culture. Despite these efforts by researchers, these projects have remained in the preclinical stage.

Known ribozymes

Well validated naturally occurring ribozyme classes: *GIR1 branching ribozyme The Lariat capping ribozyme (formerly called GIR1 branching ribozyme) is a ~180 nt ribozyme with an apparent resemblance to a group I ribozyme.

It is found within a complex type of group I introns also termed twin-ribozyme introns.

Rather than spl ...

* ''glmS'' ribozyme

* Group I Group 1 may refer to:

* Alkali metal, a chemical element classification for Alkali metal

* Group 1 (racing), a historic (until 1981) classification for Touring car racing, applied to standard touring cars. Comparable to modern FIA Group N

* Group On ...

self-splicing intron

* Group II self-splicing intron - Spliceosome

A spliceosome is a large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex found primarily within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The spliceosome is assembled from small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) and numerous proteins. Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecules bind to specifi ...

is likely derived from Group II self-splicing ribozymes.

* Hairpin ribozyme

The hairpin ribozyme is a small section of RNA that can act as a ribozyme. Like the hammerhead ribozyme it is found in RNA satellites of plant viruses. It was first identified in the minus strand of the tobacco ringspot virus (TRSV) satellite R ...

* Hammerhead ribozyme

The hammerhead ribozyme is an RNA motif that catalyzes reversible cleavage and ligation reactions at a specific site within an RNA molecule. It is one of several catalytic RNAs (ribozymes) known to occur in nature. It serves as a model system for ...

* HDV ribozyme

The hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme is a non-coding RNA found in the hepatitis delta virus that is necessary for viral replication and is the only known human virus that utilizes ribozyme activity to infect its host. The ribozyme acts to p ...

* rRNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosoma ...

- Found in all living cells and links amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

to form protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s.

* RNase P

Ribonuclease P (, ''RNase P'') is a type of ribonuclease which cleaves RNA. RNase P is unique from other RNases in that it is a ribozyme – a ribonucleic acid that acts as a catalyst in the same way that a protein-based enzyme would. Its fu ...

* Twister ribozyme

The twister ribozyme is a catalytic RNA structure capable of self- cleavage. The nucleolytic activity of this ribozyme has been demonstrated both ''in vivo'' and ''in vitro'' and has one of the fastest catalytic rates of naturally occurring ribo ...

* Twister sister ribozyme

* VS ribozyme

The Varkud satellite (VS) ribozyme is an RNA enzyme that carries out the cleavage of a phosphodiester bond.

Introduction

Varkud satellite (VS) ribozyme is the largest known nucleolytic ribozyme and found to be embedded in VS RNA. VS RNA is a long ...

* Pistol ribozyme

* Hatchet ribozyme

Background: The hatchet ribozyme is an RNA structure that catalyzes its own cleavage at a specific site. In other words, it is a self-cleaving ribozyme. Hatchet ribozymes were discovered by a bioinformatics strategy as RNAs Associated with Genes ...

* Viroids

Viroids are small single-stranded, circular RNAs that are infectious pathogens. Unlike viruses, they have no protein coating. All known viroids are inhabitants of angiosperms (flowering plants), and most cause diseases, whose respective economi ...

See also

*Deoxyribozyme

Deoxyribozymes, also called DNA enzymes, DNAzymes, or catalytic DNA, are DNA oligonucleotides that are capable of performing a specific chemical reaction, often but not always catalytic. This is similar to the action of other biological enzymes, ...

*Spiegelman Monster Spiegelman's Monster is the name given to an RNA chain of only 218 nucleotides that is able to be reproduced by the RNA replication enzyme RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, also called RNA replicase. It is named after its creator, Sol Spiegelman, of th ...

*Catalysis

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recyc ...

*Enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

*RNA world hypothesis

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

*Peptide nucleic acid

Peptide nucleic acid (PNA) is an artificially synthesized polymer similar to DNA or RNA.

Synthetic peptide nucleic acid oligomers have been used in recent years in molecular biology procedures, diagnostic assays, and antisense therapies. Due to ...

*Nucleic acid analogues

Nucleic acid analogues are compounds which are analogous (structurally similar) to naturally occurring RNA and DNA, used in medicine and in molecular biology research.

Nucleic acids are chains of nucleotides, which are composed of three parts: ...

*PAH world hypothesis

The PAH world hypothesis is a speculative hypothesis that proposes that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), known to be abundant in the universe, including in comets, and assumed to be abundant in the primordial soup of the early Earth, played ...

* SELEX

*OLE RNA

OLE RNA (Ornate Large Extremophilic RNA) is a conserved RNA structure present in certain bacteria. The RNA averages roughly 610 nucleotides in length. The only known RNAs that are longer than OLE RNA are ribozymes such as the group II intron an ...

Notes and references

Further reading

* * * * * * * * *External links

Tom Cech's Short Talk: "Discovering Ribozymes"

{{Portal bar, Biology RNA Catalysts Biomolecules * Metabolism Chemical kinetics RNA splicing