RB-36 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Convair B-36 "Peacemaker" is a

globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 17 January 2012. The B-36 was arguably obsolete from the outset, being piston-powered, coupled with the widespread introduction of first-generation jet fighters in potential enemy air forces. However, its jet rival, the

globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 5 September 2009. Changes in the USAAF requirements did add back any weight saved in redesigns, and cost more time. A new antenna system needed to be designed to accommodate an ordered radio and radar system. The Pratt and Whitney engines were redesigned, adding another .

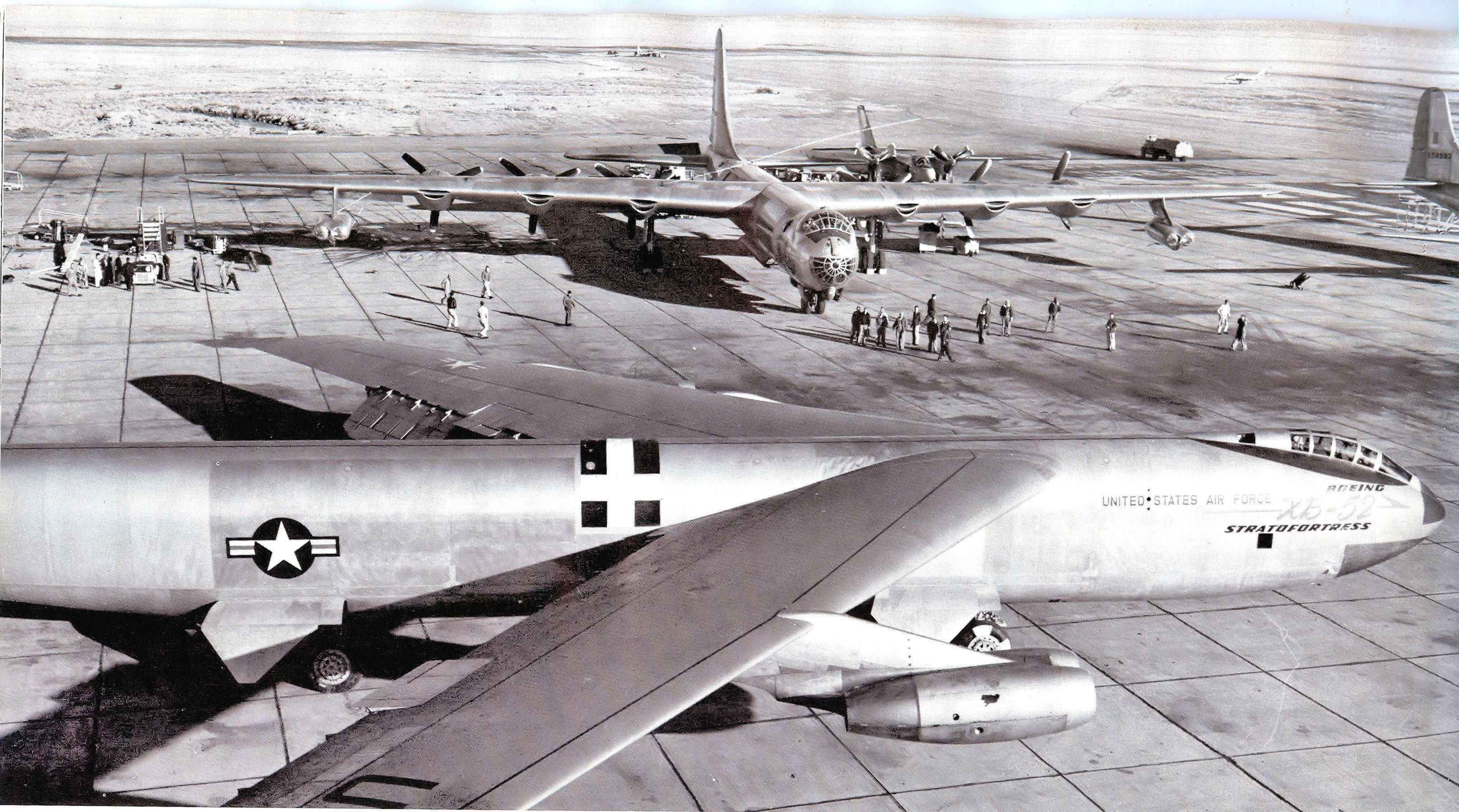

The B-36 took shape as an aircraft of immense proportions. It was two-thirds longer than the previous "superbomber", the B-29. The wingspan and tail height of the B-36 exceeded those of the 1960s Soviet Union's

The B-36 took shape as an aircraft of immense proportions. It was two-thirds longer than the previous "superbomber", the B-29. The wingspan and tail height of the B-36 exceeded those of the 1960s Soviet Union's

"Remember the B-36."

''Popular Science'', September 1961. The wing area permitted cruising altitudes well above the operating ceiling of any 1940s-era operational piston and jet-turbine fighters. Most versions of the B-36 could cruise at over . B-36 mission logs commonly recorded mock attacks against U.S. cities while flying at . In 1954, the

The XB-36 featured a single-wheel main

The XB-36 featured a single-wheel main

"Summary of Air Force accident report."

Goleta Air and Space Museum, air-and-space.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010. The Convair B-36 was the only aircraft designed to carry the

The Convair B-36 was the only aircraft designed to carry the  The first 21 B-36As were delivered in 1948. They were interim airframes, intended for crew training and later conversion. No defensive armament was fitted, since none was ready. Once later models were available, all B-36As were converted to RB-36E reconnaissance models. The first B-36 variant meant for normal operation was the B-36B, delivered beginning in November 1948. This aircraft met all the 1941 requirements, but had serious problems with engine reliability and maintenance (changing the 336 spark plugs was a task dreaded by ground crews) and with the availability of armaments and spare parts. Later models featured more powerful variants of the R-4360 engine, improved radar, and redesigned crew compartments.

The four jet engines increased fuel consumption and reduced range. Gun turrets were already recognized as obsolete, and newer bombers had been limited to just a tail turret, or no gunners at all for several years but the development of several

The first 21 B-36As were delivered in 1948. They were interim airframes, intended for crew training and later conversion. No defensive armament was fitted, since none was ready. Once later models were available, all B-36As were converted to RB-36E reconnaissance models. The first B-36 variant meant for normal operation was the B-36B, delivered beginning in November 1948. This aircraft met all the 1941 requirements, but had serious problems with engine reliability and maintenance (changing the 336 spark plugs was a task dreaded by ground crews) and with the availability of armaments and spare parts. Later models featured more powerful variants of the R-4360 engine, improved radar, and redesigned crew compartments.

The four jet engines increased fuel consumption and reduced range. Gun turrets were already recognized as obsolete, and newer bombers had been limited to just a tail turret, or no gunners at all for several years but the development of several

The B-36, including its GRB-36, RB-36, and XC-99 variants, was in USAF service as part of the SAC from 1948 to 1959. The RB-36 variants of the B-36 were used for reconnaissance during the Cold War with the Soviet Union and the B-36 bomber variants conducted training and test operations and stood ground and airborne alert, but the latter variants were never used offensively as bombers against hostile forces; they never fired a shot in combat.

The B-36, including its GRB-36, RB-36, and XC-99 variants, was in USAF service as part of the SAC from 1948 to 1959. The RB-36 variants of the B-36 were used for reconnaissance during the Cold War with the Soviet Union and the B-36 bomber variants conducted training and test operations and stood ground and airborne alert, but the latter variants were never used offensively as bombers against hostile forces; they never fired a shot in combat.

The Wasp Major engines had a prodigious appetite for

The Wasp Major engines had a prodigious appetite for

As engine fires occurred with the B-36's radial engines, some crews humorously changed the aircraft's slogan from "six turning, four burning" into "two turning, two burning, two smoking, two choking and two more unaccounted for".Daciek, Michael R

As engine fires occurred with the B-36's radial engines, some crews humorously changed the aircraft's slogan from "six turning, four burning" into "two turning, two burning, two smoking, two choking and two more unaccounted for".Daciek, Michael R

"Speaking at random about flying and writing: B-36 Peacemaker/Ten Engine Bomber"

YourHub.com, 13 December 2006. Retrieved: 6 April 2009. This problem was exacerbated by the propellers' pusher configuration, which increased

Training missions were typically in two parts, a 40-hour flight—followed by time on the ground for refueling and maintenance—and then a 24-hour second flight. With a sufficiently light load, the B-36 could fly at least 10,000 mi (16,000 km) nonstop, and the highest cruising speed of any version, the B-36J-III, was at 230 mph (380 km/h). Engaging the jet engines could raise the cruising speed to over 400 mph (650 km/h). Hence, a 40-hour mission, with the jets used only for takeoff and climbing, flew about 9,200 mi (15,000 km).

Due to its massive size, the B-36 was never considered sprightly or agile; Lieutenant General James Edmundson likened it to "sitting on your front porch and flying your house around". Crew compartments were nonetheless cramped, especially when occupied for 24 hours by a crew of 15 in full flight kit.

War missions would have been one-way, taking off from forward bases in

Training missions were typically in two parts, a 40-hour flight—followed by time on the ground for refueling and maintenance—and then a 24-hour second flight. With a sufficiently light load, the B-36 could fly at least 10,000 mi (16,000 km) nonstop, and the highest cruising speed of any version, the B-36J-III, was at 230 mph (380 km/h). Engaging the jet engines could raise the cruising speed to over 400 mph (650 km/h). Hence, a 40-hour mission, with the jets used only for takeoff and climbing, flew about 9,200 mi (15,000 km).

Due to its massive size, the B-36 was never considered sprightly or agile; Lieutenant General James Edmundson likened it to "sitting on your front porch and flying your house around". Crew compartments were nonetheless cramped, especially when occupied for 24 hours by a crew of 15 in full flight kit.

War missions would have been one-way, taking off from forward bases in

The B-36 was employed in a variety of aeronautical experiments throughout its service life. Its immense size, range, and payload capacity lent itself to use in research and development programs. These included nuclear propulsion studies, and "parasite" programs in which the B-36 carried smaller interceptors or reconnaissance aircraft.

In May 1946, the Air Force began the Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft project, which was followed in May 1951 by the

The B-36 was employed in a variety of aeronautical experiments throughout its service life. Its immense size, range, and payload capacity lent itself to use in research and development programs. These included nuclear propulsion studies, and "parasite" programs in which the B-36 carried smaller interceptors or reconnaissance aircraft.

In May 1946, the Air Force began the Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft project, which was followed in May 1951 by the

"Parasite Fighter Programs: Project Tom-Tom."

Goleta Air and Space Museum, air-and-space.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

One of the SAC's initial missions was to plan strategic aerial reconnaissance on a global scale. The first efforts were in photo-reconnaissance and mapping. Along with the photo-reconnaissance mission, a small

One of the SAC's initial missions was to plan strategic aerial reconnaissance on a global scale. The first efforts were in photo-reconnaissance and mapping. Along with the photo-reconnaissance mission, a small  The standard RB-36D carried up to 23 cameras, primarily K-17C, K-22A, K-38, and K-40 cameras. A special 240-inch focal length camera (known as the Boston Camera after the university where it was designed) was tested on 44-92088, the aircraft being redesignated ERB-36D. The long focal length was achieved by using a two-mirror reflection system. The camera was capable of resolving a golf ball at an altitude and side range of . That is a slant range over . The camera and the contact print of this test can be seen at the

The standard RB-36D carried up to 23 cameras, primarily K-17C, K-22A, K-38, and K-40 cameras. A special 240-inch focal length camera (known as the Boston Camera after the university where it was designed) was tested on 44-92088, the aircraft being redesignated ERB-36D. The long focal length was achieved by using a two-mirror reflection system. The camera was capable of resolving a golf ball at an altitude and side range of . That is a slant range over . The camera and the contact print of this test can be seen at the

With the appearance of the Soviet

With the appearance of the Soviet

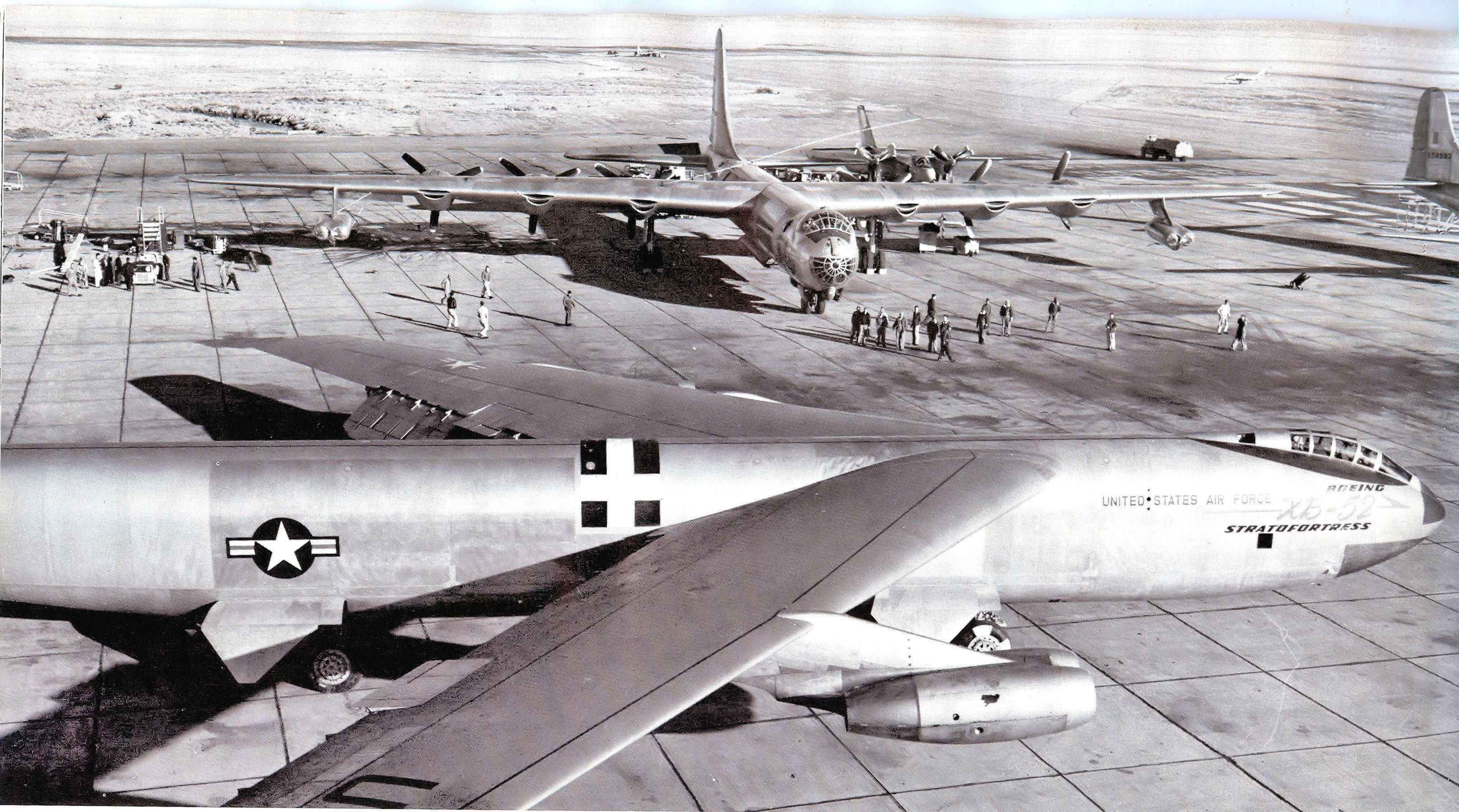

In 1951, the USAF asked Convair to build a prototype of an all-jet variant of the B-36. Convair complied by replacing the wings on a B-36F with swept wings, from which were suspended eight Pratt & Whitney XJ57-P-3 jet engines. The result was the B-36G, later renamed the

In 1951, the USAF asked Convair to build a prototype of an all-jet variant of the B-36. Convair complied by replacing the wings on a B-36F with swept wings, from which were suspended eight Pratt & Whitney XJ57-P-3 jet engines. The result was the B-36G, later renamed the

National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: 15 May 2010. Just as the C-97 was the transport variant of the B-50, the B-36 was the basis for the

"XC-99 begins piece-by-piece trip to Air Force Museum."

''433rd Airlift Wing Public Affairs'', 22 April 2004. A commercial airliner derived from the XC-99, the

only four complete B-36 type aircraft survive from the original 384 produced.

;RB-36H

* AF Ser. No. 51-13730 is at

only four complete B-36 type aircraft survive from the original 384 produced.

;RB-36H

* AF Ser. No. 51-13730 is at

"Convair B-36 Crash Reports and Wreck Sites."

Goleta Air and Space Museum, air-and-space.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010. A total of 32 B-36s were written off in accidents between 1949 and 1957 of 385 built. When a crash occurred, the On 18 March 1953, RB-36H-25, 51-13721, flew off course in bad weather and crashed near

On 18 March 1953, RB-36H-25, 51-13721, flew off course in bad weather and crashed near

"Lost Nuke".

Myth Merchant Films, Spruce Grove, Alberta, 2004.

''Air and Space/Smithsonian'', April 1996. Retrieved: 3 February 2007. * Grant, R.G. and John R. Dailey. ''Flight: 100 Years of Aviation''. Harlow, Essex, UK: DK Adult, 2007. . * Jacobsen, Meyers K. ''Convair B-36: A Comprehensive History of America's "Big Stick"''. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military History, 1997. . * Jacobsen, Meyers K. ''Convair B-36: A Photo Chronicle''. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Military History, 1999. . * Jacobsen, Meyers K. "Peacemaker." ''Airpower'', Vol. 4, No. 6, November 1974. * Jacobsen, Meyers K. and Ray Wagner. ''B-36 in Action (Aircraft in Action Number 42)''. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1980. . * Jenkins, Dennis R. ''B-36 Photo Scrapbook''. St. Paul, Minnesota: Specialty Press Publishers and Wholesalers, 2003. . * Jenkins, Dennis R. ''Convair B-36 Peacemaker''. St. Paul, Minnesota: Specialty Press Publishers and Wholesalers, 1999. . * Jenkins, Dennis R. ''Magnesium Overcast: The Story of the Convair B-36''. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2002., . * Johnsen, Frederick A. ''Thundering Peacemaker, the B-36 Story in Words and Pictures''. Tacoma, Washington: Bomber Books, 1978. . * Knaack, Marcelle Size. ''Encyclopedia of U.S. Air Force aircraft and missile systems '' Volume II: Post-World War II Bombers, 1945–1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1988.

Online - via media.defense.gov

* Leach, Norman S. ''Broken Arrow: America's First Lost Nuclear Weapon''. Calgary, Alberta: Red Deer Press, 2008. . * Miller, Jay and Roger Cripliver. "B-36: The Ponderous Peacemaker." ''Aviation Quarterly'', Vol. 4, No. 4, 1978. * Miller, Jay. "Tip Tow & Tom-Tom". ''

"Flying the Aluminum and Magnesium Overcast".

''The collected articles and photographs of Ted A. Morris'', 2000. Retrieved: 4 September 2006. * Orman, Edward W. "One Thousand on Top: A Gunner's View of Flight from the Scanning Blister of a B-36." ''Airpower'', Vol. 17, No. 2, March 1987. * Puryear, Edgar. ''Stars in Flight''. Novato, California: Presidio Press, 1981. * Pyeatt, Don. ''B-36: Saving the Last Peacemaker (Third Edition)''. Fort Worth, Texas: ProWeb Publishing, 2006. . * Shiel, Walter P

"The B-36 Peacemaker: 'There Aren't Programs Like This Anymore'".

''cessnawarbirds.com''. Retrieved: 19 July 2009. * Taylor, John W.R. "Convair B-36." ''Combat Aircraft of the World from 1909 to the present''. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969. . * Thomas, Tony. ''A Wonderful Life: The Films and Career of James Stewart''. Secaucus, New Jersey: Citadel Press, 1988. . * Wagner, Ray. ''American Combat Planes''. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1968. . * Wilson, Stewart. ''Combat Aircraft since 1945.'' London: Aerospace Publications, 2000. . * Winchester, Jim. "Convair B-36". ''Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile)''. Rochester, Kent, UK: The Grange plc., 2006. . * Wolk, Herman S. ''Fulcrum of Power: Essays on the United States Air Force and National Security''. Darby, Pennsylvania: Diane Publishing, 2003. . * Yenne, Bill. "Convair B-36 Peacemaker." ''International Air Power Review'', Vol. 13, Summer 2004. London: AirTime Publishing Inc., 2004. .

USAF Museum: XB-36

USAF Museum: B-36A

Video of The B-36 from Strategic Air Command. 5:32

"I Flew with the Atomic Bombers"

''

AeroWeb: B-36 versions and survivors

"I Flew Thirty-One Hours in a B-36"

''Popular Mechanics'', September 1950

''Size 36'', 1950-produced "first public film" on the B-36, in detail

{{Use dmy dates, date=August 2019

strategic bomber

A strategic bomber is a medium- to long-range Penetrator (aircraft), penetration bomber aircraft designed to drop large amounts of air-to-ground weaponry onto a distant target for the purposes of debilitating the enemy's capacity to wage war. Unl ...

that was built by Convair

Convair, previously Consolidated Vultee, was an American aircraft manufacturing company that later expanded into rockets and spacecraft. The company was formed in 1943 by the merger of Consolidated Aircraft and Vultee Aircraft. In 1953, i ...

and operated by the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Si ...

(USAF) from 1949 to 1959. The B-36 is the largest mass-produced piston-engined aircraft ever built. It had the longest wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the other wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777–200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingspan o ...

of any combat aircraft ever built, at . The B-36 was the first bomber capable of delivering any of the nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s in the U.S. arsenal from inside its four bomb bays without aircraft modifications. With a range of and a maximum payload of , the B-36 was capable of intercontinental flight without refuelling.

Entering service in 1948, the B-36 was the primary nuclear weapons delivery

Nuclear weapons delivery is the technology and systems used to place a nuclear weapon at the position of detonation, on or near its target. Several methods have been developed to carry out this task.

''Strategic'' nuclear weapons are used primari ...

vehicle of Strategic Air Command

Strategic Air Command (SAC) was both a United States Department of Defense Specified Command and a United States Air Force (USAF) Major Command responsible for command and control of the strategic bomber and intercontinental ballistic missile ...

(SAC) until it was replaced by the jet-powered Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the United States Air ...

beginning in 1955. All but four aircraft have been scrapped.

Development

The genesis of the B-36 can be traced to early 1941, prior to the entry of the United States intoWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. At the time, the threat existed that Britain might fall to the German "Blitz", making a strategic bombing effort by the United States Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical r ...

(USAAC) against Germany impossible with the aircraft of the time..

The United States would need a new class of bomber that would reach Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and return to bases in North America,Taylor 1969, p. 465. necessitating a combat range of at least , the length of a Gander, Newfoundland

Gander is a town located in the northeastern part of the island of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, approximately south of Gander Bay, south of Twillingate and east of Grand Falls-Windsor. Located on the nor ...

–Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

round trip. The USAAC therefore sought a bomber of truly intercontinental range,Johnson 1978, p. 1. similar to the German Reichsluftfahrtministerium

The Ministry of Aviation (german: Reichsluftfahrtministerium, abbreviated RLM) was a government department during the period of Nazi Germany (1933–45). It is also the original name of the Detlev-Rohwedder-Haus building on the Wilhelmstrass ...

's (RLM) ultralong-range ''Amerikabomber

The ''Amerikabomber'' () project was an initiative of the German Ministry of Aviation (''Reichsluftfahrtministerium'') to obtain a long-range strategic bomber for the ''Luftwaffe'' that would be capable of striking the United States (specifical ...

'' program, the subject of a 33-page proposal submitted to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

on 12 May 1942.

The USAAC sent out the initial request on 11 April 1941, asking for a top speed, a cruising speed, a service ceiling of —beyond the range of ground-based anti-aircraft fire—and a maximum range of at . These requirements proved too demanding for any short-term design, far exceeding the technology of the day, so on 19 August 1941, they were reduced to a maximum range of , an effective combat radius

Radius of action, combat radius, or combat range in military terms, refers to the maximum distance a ship, aircraft, or vehicle can travel away from its base along a given course with normal load and return without refueling, allowing for all safet ...

of with a bombload, a cruising speed between , and a service ceiling of —above the maximum effective altitude of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

's anti-aircraft guns, save for the rarely-deployed 12.8 cm FlaK 40 heavy flak

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based ...

cannon.

World War II and after

As the Pacific war progressed, the USAAF increasingly needed a bomber capable of reaching Japan from its bases inHawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, and the development of the B-36 resumed in earnest. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and ...

, in discussions with high-ranking officers of the USAAF, decided to waive normal army procurement procedures, and on 23 July 1943 – some 15 months after the Germans' ''Amerikabomber'' proposal's submission made it to their RLM authority, and coincidentally, the same day that, in Germany, the RLM had ordered the Heinkel

Heinkel Flugzeugwerke () was a German aircraft manufacturing company founded by and named after Ernst Heinkel. It is noted for producing bomber aircraft for the Luftwaffe in World War II and for important contributions to high-speed flight, with ...

firm to design a six-engined version of their own, BMW 801

The BMW 801 was a powerful German air-cooled 14-cylinder- radial aircraft engine built by BMW and used in a number of German Luftwaffe aircraft of World War II. Production versions of the twin-row engine generated between 1,560 and 2,000 P ...

E powered ''Amerikabomber'' design proposal – the USAAF submitted a "letter of intent" to Convair, ordering an initial production run of 100 B-36s before the completion and testing of the two prototypes. The first delivery was due in August 1945, and the last in October 1946, but Consolidated (by this time renamed Convair after its 1943 merger with Vultee Aircraft

The Vultee Aircraft Corporation became an independent company in 1939 in Los Angeles County, California. It had limited success before merging with the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation in 1943, to form the Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporatio ...

) delayed delivery. The aircraft was unveiled on 20 August 1945 (three months after V-E Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easte ...

), and flew for the first time on 8 August 1946.

After the establishment of an independent United States Air Force in 1947, the beginning in earnest of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

with the 1948 Berlin Airlift

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, ro ...

, and the 1949 atmospheric test of the first Soviet atomic bomb, American military planners sought bombers capable of delivering the very large and heavy first-generation atomic bombs.

The B-36 was the only American aircraft with the range and payload

Payload is the object or the entity which is being carried by an aircraft or launch vehicle. Sometimes payload also refers to the carrying capacity of an aircraft or launch vehicle, usually measured in terms of weight. Depending on the nature of ...

to carry such bombs from airfields on American soil to targets in the USSR. The modification to allow the use of larger atomic weapons on the B-36 was called the "Grand Slam Installation"."B-36 Peacemaker."globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 17 January 2012. The B-36 was arguably obsolete from the outset, being piston-powered, coupled with the widespread introduction of first-generation jet fighters in potential enemy air forces. However, its jet rival, the

Boeing B-47 Stratojet

The Boeing B-47 Stratojet (Boeing company designation Model 450) is a retired American long- range, six-engined, turbojet-powered strategic bomber designed to fly at high subsonic speed and at high altitude to avoid enemy interceptor aircraft ...

, which did not become fully operational until 1953, lacked the range to attack the Soviet homeland from North America without aerial refueling and could not carry the huge first-generation Mark 16 hydrogen bomb.

The other American piston bombers of the day, the B-29

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

and B-50, were also too limited in range to be part of America's developing nuclear arsenal. Intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapo ...

s did not become sufficiently reliable until the early 1960s. Until the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress

The Boeing B-52 Stratofortress is an American long-range, subsonic, jet-powered strategic bomber. The B-52 was designed and built by Boeing, which has continued to provide support and upgrades. It has been operated by the United States Air ...

became operational in 1955, the B-36, as the only truly intercontinental bomber, continued to be the primary nuclear weapons delivery vehicle of the SAC.

Convair touted the B-36 as the "aluminum overcast", a so-called "long rifle

The long rifle, also known as the longrifle, Kentucky rifle, Pennsylvania rifle, or American longrifle, a muzzle-loading firearm used for hunting and warfare, was one of the first commonly-used rifles. The American rifle was characterized by a ...

" giving SAC truly global reach. During General Curtis LeMay

Curtis Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990) was an American Air Force general who implemented a controversial strategic bombing campaign in the Pacific theater of World War II. He later served as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air ...

's tenure as head of SAC (1949–57), the B-36, through intense crew training and development, formed the heart of the Strategic Air Command. Its maximum payload was more than four times that of the B-29, and exceeded that of the B-52.

The B-36 was slow and could not refuel in midair, but could fly missions to targets away and stay aloft as long as 40 hours. Moreover, the B-36 was believed to have "an ace up its sleeve": a phenomenal cruising altitude for a piston-driven aircraft, made possible by its huge wing area and six 28-cylinder engines, putting it out of range of most of the interceptors of the day, as well as ground-based anti-aircraft gun

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based ...

s.

Experimentals and prototypes

Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation

Convair, previously Consolidated Vultee, was an American aircraft manufacturing company that later expanded into rockets and spacecraft. The company was formed in 1943 by the merger of Consolidated Aircraft and Vultee Aircraft. In 1953, i ...

(later Convair) and Boeing Aircraft Company

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and p ...

took part in the competition, with Consolidated winning a tender on 16 October 1941. Consolidated asked for a $15 million contract with $800,000 for research and development, mockup, and tooling. Two experimental bombers were proposed, the first to be delivered in 30 months, and the second within another six months. Originally designated Model B-35, the name was changed to B-36 to avoid confusion with the Northrop YB-35

The Northrop YB-35, Northrop designation N-9 or NS-9, were experimental heavy bomber aircraft developed by the Northrop Corporation for the United States Army Air Forces during and shortly after World War II. The airplane used the radical and p ...

piston-engined flying-wing bomber, against which the B-36 was meant to compete for a production contract.

Throughout its development, the B-36 encountered delays. When the United States entered World War II, Consolidated was ordered to slow B-36 development and greatly increase Consolidated B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models des ...

production. The first mockup was inspected on 20 July 1942, following six months of refinements. A month after the inspection, the project was moved from San Diego, California, to Fort Worth, Texas, which set back development several months. Consolidated changed the tail from a twin-tail to a single, thereby saving , but this change delayed delivery by 120 days.

The tricycle landing gear

Tricycle gear is a type of aircraft undercarriage, or ''landing gear'', arranged in a tricycle fashion. The tricycle arrangement has a single nose wheel in the front, and two or more main wheels slightly aft of the center of gravity. Tricycle ...

system's initial main gear design, with huge single wheels found to cause significant ground pressure problems, limited the B-36 to operating from just three air bases in the United States: Carswell Field (former Carswell AFB, now NAS JRB Fort Worth

Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth (abbreviated NAS JRB Fort Worth) includes Carswell Field, a military airbase located west of the central business district of Fort Worth, in Tarrant County, Texas, United States. This military ai ...

/Carswell Field), adjacent to the Consolidated factory in Fort Worth, Texas; Eglin Field Eglin may refer to:

* Eglin (surname)

* Eglin Air Force Base, a United States Air Force base located southwest of Valparaiso, Florida

* Federal Prison Camp, Eglin, a Federal Bureau of Prisons minimum security prison on the grounds of Eglin Air Forc ...

(now Eglin AFB

Eglin Air Force Base is a United States Air Force (USAF) base in the western Florida Panhandle, located about southwest of Valparaiso in Okaloosa County.

The host unit at Eglin is the 96th Test Wing (formerly the 96th Air Base Wing). The 9 ...

), Florida; and Fairfield-Suisun Field (now Travis AFB

Travis Air Force Base is a United States Air Force base under the operational control of the Air Mobility Command (AMC), located three miles (5 km) east of the central business district of the city of Fairfield, in Solano County, California ...

) in California.

As a result, the Air Force mandated that Consolidated design a four-wheeled bogie

A bogie ( ) (in some senses called a truck in North American English) is a chassis or framework that carries a wheelset, attached to a vehicle—a modular subassembly of wheels and axles. Bogies take various forms in various modes of transp ...

-type wheel system for each main gear unit instead, which distributed the pressure more evenly and reduced weight by ."Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD): B-36 Peacemaker"globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 5 September 2009. Changes in the USAAF requirements did add back any weight saved in redesigns, and cost more time. A new antenna system needed to be designed to accommodate an ordered radio and radar system. The Pratt and Whitney engines were redesigned, adding another .

Design

Antonov An-22

The Antonov An-22 "Antei" (, ''An-22 Antej''; English ''Antaeus'') (NATO reporting name "Cock") is a heavy military transport aircraft designed by the Antonov Design Bureau in the Soviet Union. Powered by four turboprop engines each driving a pa ...

''Antheus'' military transport, the largest ever propeller-driven aircraft put into production. Only with the advent of the Boeing 747

The Boeing 747 is a large, long-range wide-body airliner designed and manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes in the United States between 1968 and 2022.

After introducing the 707 in October 1958, Pan Am wanted a jet times its size, ...

and the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy

The Lockheed C-5 Galaxy is a large military transport aircraft designed and built by Lockheed, and now maintained and upgraded by its successor, Lockheed Martin. It provides the United States Air Force (USAF) with a heavy intercontinental-rang ...

, both designed two decades later, did American aircraft capable of lifting a heavier payload become commonplace.

The wings of the B-36 were large even when compared with present-day aircraft, exceeding, for example, those of the C-5 Galaxy, and enabled the B-36 to carry enough fuel to fly the intended long missions without refueling. The maximum thickness of the wing, measured perpendicular to the chord, was , containing a crawlspace that allowed access to the engines.Griswold, Wesley P"Remember the B-36."

''Popular Science'', September 1961. The wing area permitted cruising altitudes well above the operating ceiling of any 1940s-era operational piston and jet-turbine fighters. Most versions of the B-36 could cruise at over . B-36 mission logs commonly recorded mock attacks against U.S. cities while flying at . In 1954, the

turrets

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* M ...

and other nonessential equipment were removed (not entirely unlike the earlier Silverplate

Silverplate was the code reference for the United States Army Air Forces' participation in the Manhattan Project during World War II. Originally the name for the aircraft modification project which enabled a B-29 Superfortress bomber to drop a ...

program for the atomic bomb-carrying "specialist" B-29s) that resulted in a "featherweight" configuration believed to have resulted in a top speed of , and cruise at and dash at over , perhaps even higher.

The large wing area and the option of starting the four jet engines supplementing the piston engines in later versions gave the B-36 a wide margin between stall speed

In fluid dynamics, a stall is a reduction in the lift coefficient generated by a foil as angle of attack increases.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition'', p. 486. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. This occurs when t ...

(''V''S) and maximum speed (''V''max) at these altitudes. This made the B-36 more maneuverable at high altitude than the USAF

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Aerial warfare, air military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part ...

jet interceptors of the day, which either could not fly above , or if they did, were likely to stall out when trying to maneuver or fire their guns. However, the U.S. Navy argued that their McDonnell F2H Banshee

The McDonnell F2H Banshee (company designation McDonnell Model 24) is an American single-seat carrier-based jet fighter aircraft deployed by the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps from 1948 to 1961. A development of the FH Phanto ...

fighter could intercept the B-36, thanks to its ability to operate at more than . The USAF declined the invitation from the U.S. Navy for a fly-off between the Banshee and the B-36. Later, the new Secretary of Defense, Louis A. Johnson

Louis Arthur Johnson (January 10, 1891April 24, 1966) was an American politician and Attorney general, attorney who served as the second United States Secretary of Defense from 1949 to 1950. He was the United States Assistant Secretary of War, A ...

, who considered the U.S. Navy and naval aviation essentially obsolete in favor of the USAF and SAC, forbade putting the Navy's claim to the test.

The propulsion system of the B-36 was unique, with six 28-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major

The Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major is an American 28-cylinder four-row radial piston aircraft engine designed and built during World War II. First run in 1944, at , it is the largest-displacement aviation piston engine to be mass-produced in ...

radial engine

The radial engine is a reciprocating type internal combustion engine configuration in which the cylinders "radiate" outward from a central crankcase like the spokes of a wheel. It resembles a stylized star when viewed from the front, and is ...

s mounted in an unusual pusher configuration

In an aircraft with a pusher configuration (as opposed to a tractor configuration), the propeller(s) are mounted behind their respective engine(s). Since a pusher propeller is mounted behind the engine, the drive shaft is in compression in n ...

, rather than the conventional four-engine, tractor propeller

In aviation, the term tractor configuration refers to an aircraft constructed in the standard configuration with its engine mounted with the propeller in front of it so that the aircraft is "pulled" through the air. Oppositely, the pusher co ...

layout of other heavy bomber

Heavy bombers are bomber aircraft capable of delivering the largest payload of air-to-ground weaponry (usually bombs) and longest range ( takeoff to landing) of their era. Archetypal heavy bombers have therefore usually been among the larg ...

s. The prototype R-4360s delivered a total of . While early B-36s required long takeoff runs, this situation was improved with later versions, delivering a significantly increased power output of total. Each engine drove a three-bladed propeller, in diameter, mounted in the pusher configuration, thought to be the second-largest diameter propeller design ever used to power a piston-engined aircraft (after that of the Linke-Hofmann R.II). This unusual configuration prevented propeller turbulence from interfering with airflow over the wing, but could also lead to engine overheating due to insufficient airflow around the engines, resulting in inflight engine fires.

The large, slow-turning propellers interacted with the high-pressure airflow behind the wings to produce an easily recognizable very-low-frequency pulse at ground level that betrayed approaching flights.

Addition of jet propulsion

Beginning with the B-36D, Convair added a pair ofGeneral Electric J47

The General Electric J47 turbojet (GE company designation TG-190) was developed by General Electric from its earlier J35. It first flew in May 1948. The J47 was the first axial-flow turbojet approved for commercial use in the United States. It ...

-19 jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine discharging a fast-moving jet (fluid), jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition can include Rocket engine, rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and ...

s suspended near the end of each wing; these were also retrofitted to all extant B-36Bs. Consequently, the B-36 was configured to have 10 engines, six radial propeller engines and four jet engines, leading to the B-36 slogan of "six turnin' and four burnin' ". The B-36 had more engines than any other mass-produced aircraft. The jet pods greatly improved takeoff performance and dash speed over the target. In normal cruising flight, the jet engines were shut down to conserve fuel. When the jet engines were shut down, louvers closed off the front of the pods to reduce drag and to prevent ingestion of sand and dirt. The jet engine louvers were opened and closed by the flight crew in the cockpit, whether the B-36 was on the ground or in the air. The two pods with four turbojets and the six piston engines combined gave the B-36 a total of for short periods of time.

Crew

The B-36 had a crew of 15. As in the B-29 and B-50, the pressurized flight deck and crew compartment were linked to the rear compartment by a pressurized tunnel through the bomb bay. In the B-36, movement through the tunnel was on a wheeled trolley, pulling on a rope. The rear compartment featured six bunks and a dining galley and led to the tail turret.Landing gear

The XB-36 featured a single-wheel main

The XB-36 featured a single-wheel main landing gear

Landing gear is the undercarriage of an aircraft or spacecraft that is used for takeoff or landing. For aircraft it is generally needed for both. It was also formerly called ''alighting gear'' by some manufacturers, such as the Glenn L. Mart ...

whose tires were the largest ever manufactured up to that time, tall, wide, and weighing , with enough rubber for 60 automobile tires. These tires placed so much pressure on runways that the XB-36 was restricted to the Fort Worth airfield adjacent to the plant of manufacture, and to a mere two USAF bases beyond that. At the suggestion of General Henry H. Arnold, the single-wheel gear was soon replaced by a four-wheel bogie

A bogie ( ) (in some senses called a truck in North American English) is a chassis or framework that carries a wheelset, attached to a vehicle—a modular subassembly of wheels and axles. Bogies take various forms in various modes of transp ...

. At one point, a tank-like tracked landing gear was also tried on the XB-36, but it proved heavy and noisy. The tracked landing gear was quickly abandoned.

Weaponry

The fourbomb bay

The bomb bay or weapons bay on some military aircraft is a compartment to carry bombs, usually in the aircraft's fuselage, with "bomb bay doors" which open at the bottom. The bomb bay doors are opened and the bombs are dropped when over t ...

s could carry up to of bombs, more than 10 times the load carried by the World War II workhorse, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Thea ...

, and substantially more than the entire B-17's gross weight. The B-36 was not designed with nuclear weaponry in mind, because the mere existence of such weapons was top secret during the period when the B-36 was conceived and designed (1941–46). Nevertheless, the B-36 stepped into its nuclear delivery role immediately upon becoming operational. In all respects except speed, the B-36 could match what was arguably its approximate Soviet counterpart, the turboprop

A turboprop is a turbine engine that drives an aircraft propeller.

A turboprop consists of an intake, reduction gearbox, compressor, combustor, turbine, and a propelling nozzle. Air enters the intake and is compressed by the compressor. ...

-powered Tu-95

The Tupolev Tu-95 (russian: Туполев Ту-95; NATO reporting name: "Bear") is a large, four-engine turboprop-powered strategic bomber and missile platform. First flown in 1952, the Tu-95 entered service with the Long-Range Aviation of t ...

, which began production in January 1956 and was still in active service . Until the B-52 became operational, the B-36 was the only means of delivering the first generation Mark 17 hydrogen bomb, long, in diameter, and weighing , the heaviest and bulkiest American aerial nuclear bomb ever. Carrying this massive weapon required merging two adjacent bomb bays.

The defensive armament consisted of six remote-controlled retractable gun turrets, and fixed tail and nose turrets. Each turret was fitted with two 20 mm cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

, for a total of 16. Recoil

Recoil (often called knockback, kickback or simply kick) is the rearward thrust generated when a gun is being discharged. In technical terms, the recoil is a result of conservation of momentum, as according to Newton's third law the force r ...

vibration from gunnery practice often caused the aircraft's electrical wiring to jar loose or the vacuum tube

A vacuum tube, electron tube, valve (British usage), or tube (North America), is a device that controls electric current flow in a high vacuum between electrodes to which an electric potential difference has been applied.

The type known as ...

electronics to malfunction, leading to failure of the aircraft controls and navigation equipment; this contributed to the crash of B-36B 44-92035 on 22 November 1950.Lockett, Brian"Summary of Air Force accident report."

Goleta Air and Space Museum, air-and-space.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

The Convair B-36 was the only aircraft designed to carry the

The Convair B-36 was the only aircraft designed to carry the T-12 Cloudmaker

The T-12 (also known as Cloudmaker) earthquake bomb was developed by the United States from 1944 to 1948 and deployed until the withdrawal of the Convair B-36 Peacemaker bomber aircraft in 1958. It was one of a small class of bombs designed to ...

, a gravity bomb

An unguided bomb, also known as a free-fall bomb, gravity bomb, dumb bomb, or iron bomb, is a conventional or nuclear aircraft-delivered bomb that does not contain a guidance system and hence simply follows a ballistic trajectory. This describe ...

weighing and designed to produce an earthquake bomb

The earthquake bomb, or seismic bomb, was a concept that was invented by the British aeronautical engineer Barnes Wallis early in World War II and subsequently developed and used during the war against strategic targets in Europe. A seismic bomb ...

effect. Part of the testing process involved dropping two of the bombs on a single flight mission, one from and the second from , for a total bomb load of .

The first prototype XB-36 flew on 8 August 1946. The speed and range of the prototype failed to meet the standards set out by the USAAC in 1941. This was expected, as the Pratt & Whitney R-4360 engines required were not yet available, and the qualified workers and materials needed to install them were lacking.

A second aircraft, the YB-36, flew on 4 December 1947. It had a redesigned, high-visibility, yet still "greenhouse-like" bubble canopy

A bubble canopy is an aircraft canopy constructed without bracing, for the purpose of providing a wider unobstructed field of view to the pilot, often providing 360° all-round visibility.

The designs of bubble canopies can drastically vary; s ...

, heavily framed due to its substantial size, which was later adopted for production, and the engines used on the YB-36 were more powerful and more efficient. Altogether, the YB-36 was much closer to the production aircraft.

The first 21 B-36As were delivered in 1948. They were interim airframes, intended for crew training and later conversion. No defensive armament was fitted, since none was ready. Once later models were available, all B-36As were converted to RB-36E reconnaissance models. The first B-36 variant meant for normal operation was the B-36B, delivered beginning in November 1948. This aircraft met all the 1941 requirements, but had serious problems with engine reliability and maintenance (changing the 336 spark plugs was a task dreaded by ground crews) and with the availability of armaments and spare parts. Later models featured more powerful variants of the R-4360 engine, improved radar, and redesigned crew compartments.

The four jet engines increased fuel consumption and reduced range. Gun turrets were already recognized as obsolete, and newer bombers had been limited to just a tail turret, or no gunners at all for several years but the development of several

The first 21 B-36As were delivered in 1948. They were interim airframes, intended for crew training and later conversion. No defensive armament was fitted, since none was ready. Once later models were available, all B-36As were converted to RB-36E reconnaissance models. The first B-36 variant meant for normal operation was the B-36B, delivered beginning in November 1948. This aircraft met all the 1941 requirements, but had serious problems with engine reliability and maintenance (changing the 336 spark plugs was a task dreaded by ground crews) and with the availability of armaments and spare parts. Later models featured more powerful variants of the R-4360 engine, improved radar, and redesigned crew compartments.

The four jet engines increased fuel consumption and reduced range. Gun turrets were already recognized as obsolete, and newer bombers had been limited to just a tail turret, or no gunners at all for several years but the development of several air-to-air missile

The newest and the oldest member of Rafael's Python family of AAM for comparisons, Python-5 (displayed lower-front) and Shafrir-1 (upper-back)

An air-to-air missile (AAM) is a missile fired from an aircraft for the purpose of destroying a ...

s, including the Soviet K-5 which began test firings in 1951, eliminated the last justifications for keeping them.

In February 1954, the USAF awarded Convair a contract for a new "Featherweight" design program, which significantly reduced weight and crew size. The three configurations were:

* Featherweight I removed defensive hardware, including the six gun turrets.

* Featherweight II removed the rear compartment crew comfort features, and all hardware accommodating the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin

The McDonnell XF-85 Goblin is an American prototype fighter aircraft conceived during World War II by McDonnell Aircraft. It was intended to deploy from the bomb bay of the giant Convair B-36 bomber as a parasite fighter. The XF-85's intended ...

parasite fighter

A parasite aircraft is a component of a composite aircraft which is carried aloft and air launched by a larger carrier aircraft or mother ship to support the primary mission of the carrier. The carrier craft may or may not be able to later rec ...

.

* Featherweight III incorporated both configurations I and II.

The six turrets eliminated by Featherweight I reduced the aircraft's crew from 15 to 9. Featherweight III had a longer range and an operating ceiling of at least , especially valuable for reconnaissance missions. The B-36J-III configuration (the last 14 made) had a single radar-aimed tail turret, extra fuel tanks in the outer wings, and landing gear allowing the maximum gross weight to rise to .

Production of the B-36 ceased in 1954.

Operating and financial problems

Due to problems that occurred with the B-36 in its early stages of testing, development, and later in service, some critics referred to the aircraft as a "billion-dollar blunder". In particular, theUnited States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

saw it as a costly bungle, diverting congressional funding and interest from naval aviation

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

Naval aviation is typically projected to a position nearer the target by way of an aircraft carrier. Carrier-based ...

and aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

s in general, and carrier–based nuclear bombers in particular. In 1947, the Navy attacked congressional funding for the B-36, alleging it failed to meet Pentagon requirements. The Navy held to the pre-eminence of the aircraft carrier in the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

during World War II, presuming carrier-based aircraft would be decisive in future wars. To this end, the Navy designed , a "supercarrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a n ...

" capable of launching huge fleets of tactical aircraft or nuclear bombers. It then pushed to have funding transferred from the B-36 to USS ''United States''. The Air Force successfully defended the B-36 project, and ''United States'' was officially cancelled by Secretary of Defense

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in so ...

Louis A. Johnson

Louis Arthur Johnson (January 10, 1891April 24, 1966) was an American politician and Attorney general, attorney who served as the second United States Secretary of Defense from 1949 to 1950. He was the United States Assistant Secretary of War, A ...

in a cost-cutting move over the objections of both Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

John L. Sullivan

John Lawrence Sullivan (October 15, 1858 – February 2, 1918), known simply as John L. among his admirers, and dubbed the "Boston Strong Boy" by the press, was an American boxer recognized as the first heavyweight champion of gloved boxing, ...

and the Navy's senior uniformed leadership and to which Sullivan resigned in protest. Sullivan was replaced as Secretary of the Navy by Francis P. Matthews

Francis Patrick Matthews (March 15, 1887 – October 18, 1952) was an American who served as the 8th Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus from 1939 to 1945, the 50th United States Secretary of the Navy from 1949 to 1951, and United St ...

, who had limited familiarity with national defense issues, but was a close friend of Johnson. Several high-level Navy officials questioned the government's decision in cancelling the ''United States'' to fund the B-36, alleging a conflict of interest because Johnson had once served on Convair's board of directors. The uproar following the cancellation of ''United States'' in 1949 was nicknamed the "Revolt of the Admirals

The "Revolt of the Admirals" was a policy and funding dispute within the United States government during the Cold War in 1949, involving a number of retired and active-duty United States Navy admirals. These included serving officers Admiral L ...

", during which time Matthews dismissed and forced into retirement the serving Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral Louis E. Denfeld

Louis Emil Denfeld (April 13, 1891 – March 28, 1972) was an admiral in the United States Navy who served as Chief of Naval Operations from December 15, 1947 to November 1, 1949. He also held several significant surface commands during Wor ...

, following the CNO's testimony before the House Armed Services Committee

The U.S. House Committee on Armed Services, commonly known as the House Armed Services Committee or HASC, is a standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is responsible for funding and oversight of the Department of De ...

.Barlow 1994, p. 42.

The congressional and media furor over the firing of Admiral Denfeld, as well as the significant use of aircraft carriers in the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

, resulted in the Truman administration subsequently ousting both Johnson and Matthews in their respective secretary roles, and in the design and procurement of the subsequent of supercarriers, which were of comparable size to ''United States'', but with a design geared towards greater multirole use with composite air wings of fighter, attack, reconnaissance, electronic warfare

Electronic warfare (EW) is any action involving the use of the electromagnetic spectrum (EM spectrum) or directed energy to control the spectrum, attack an enemy, or impede enemy assaults. The purpose of electronic warfare is to deny the opponent ...

, early warning

An early warning system is a warning system that can be implemented as a chain of information communication systems and comprises sensors, event detection and decision subsystems for early identification of hazards. They work together to for ...

and antisubmarine-warfare aircraft. At the same time, heavy manned bombers for the SAC were also deemed crucial to national defense and, as a result, the two systems were never again in competition for the same budgetary resources.

Operational history

The B-36, including its GRB-36, RB-36, and XC-99 variants, was in USAF service as part of the SAC from 1948 to 1959. The RB-36 variants of the B-36 were used for reconnaissance during the Cold War with the Soviet Union and the B-36 bomber variants conducted training and test operations and stood ground and airborne alert, but the latter variants were never used offensively as bombers against hostile forces; they never fired a shot in combat.

The B-36, including its GRB-36, RB-36, and XC-99 variants, was in USAF service as part of the SAC from 1948 to 1959. The RB-36 variants of the B-36 were used for reconnaissance during the Cold War with the Soviet Union and the B-36 bomber variants conducted training and test operations and stood ground and airborne alert, but the latter variants were never used offensively as bombers against hostile forces; they never fired a shot in combat.

Maintenance

The Wasp Major engines had a prodigious appetite for

The Wasp Major engines had a prodigious appetite for lubricating oil

A lubricant (sometimes shortened to lube) is a substance that helps to reduce friction between surfaces in mutual contact, which ultimately reduces the heat generated when the surfaces move. It may also have the function of transmitting forces, t ...

; each engine required a dedicated 100-gal (380-l) tank. Normal maintenance consisted of tedious measures, such as changing the 56 spark plug

A spark plug (sometimes, in British English, a sparking plug, and, colloquially, a plug) is a device for delivering electric current from an ignition system to the combustion chamber of a spark-ignition engine to ignite the compressed fuel/ai ...

s on each of the six engines; the plugs were often fouled by the lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cut, ...

in the 145 145 may refer to:

*145 (number), a natural number

*AD 145, a year in the 2nd century AD

*145 BC, a year in the 2nd century BC

*145 (dinghy), a two-person intermediate sailing dinghy

*145 (South) Brigade

*145 (New Jersey bus) 145 may refer to:

* 1 ...

octane

Octane is a hydrocarbon and an alkane with the chemical formula , and the condensed structural formula . Octane has many structural isomers that differ by the amount and location of branching in the carbon chain. One of these isomers, 2,2,4-t ...

anti knock fuel required by the R-4360 engines. Thus, each service required changing 336 spark plugs. Another frequent maintenance job was replacing the dozens of bomb bay light bulbs, which routinely shattered during test firing of the turret guns.

The B-36 was too large to fit in most hangar

A hangar is a building or structure designed to hold aircraft or spacecraft. Hangars are built of metal, wood, or concrete. The word ''hangar'' comes from Middle French ''hanghart'' ("enclosure near a house"), of Germanic origin, from Frankish ...

s. Since even an aircraft with the range of the B-36 needed to be stationed as close to enemy targets as possible, this meant the plane was largely based in the extreme weather locations of the northern continental United States, Alaska, and the Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

. Since the maintenance had to be performed outdoors, the crews were largely exposed to the elements, with temperatures of in winters and in summers, depending on the airbase location. Special shelters were built so the maintenance crews could be given a modicum of protection. Ground crew

In all forms of aviation, ground crew (also known as ground operations in civilian aviation) are personnel that service aircraft while on the ground, during routine turn-around; as opposed to aircrew, who operate all aspects of an aircraft whilst ...

s were at risk of slipping and falling from icy wings, or being blown off the wings by propeller wash running in reverse pitch. The wing root

The wing root is the part of the wing on a fixed-wing aircraft or winged-spaceship that is closest to the fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds crew, passengers, o ...

s were thick enough, at , to enable a flight engineer

A flight engineer (FE), also sometimes called an air engineer, is the member of an aircraft's flight crew who monitors and operates its complex aircraft systems. In the early era of aviation, the position was sometimes referred to as the "air m ...

to access the engines and landing gear during flight by crawling through the wings. This was possible only at altitudes not requiring pressurization.

In 1950, Convair (then still Consolidated-Vultee

Convair, previously Consolidated Vultee, was an American aircraft manufacturing company that later expanded into rockets and spacecraft. The company was formed in 1943 by the merger of Consolidated Aircraft and Vultee Aircraft. In 1953, ...

) developed streamlined pods, looking like oversize drop tanks, that were mounted on each side of the B-36's fuselage to carry spare engines between bases. Each pod could airlift two engines. When the pods were empty, they were removed and carried in the bomb bays. No record was made of the special engine pods ever being used.

Engine fires

As engine fires occurred with the B-36's radial engines, some crews humorously changed the aircraft's slogan from "six turning, four burning" into "two turning, two burning, two smoking, two choking and two more unaccounted for".Daciek, Michael R

As engine fires occurred with the B-36's radial engines, some crews humorously changed the aircraft's slogan from "six turning, four burning" into "two turning, two burning, two smoking, two choking and two more unaccounted for".Daciek, Michael R"Speaking at random about flying and writing: B-36 Peacemaker/Ten Engine Bomber"

YourHub.com, 13 December 2006. Retrieved: 6 April 2009. This problem was exacerbated by the propellers' pusher configuration, which increased

carburetor icing

Carburetor icing, or carb icing, is an icing condition which can affect any carburetor under certain atmospheric conditions. The problem is most notable in certain realms of aviation.

Carburetor icing is caused by the temperature drop in the ca ...

. The design of the R-4360 engine tacitly assumed that it would be mounted in the conventional tractor configuration—propeller/air intake/28 cylinders/carburetor—with air flowing in that order. In this configuration, the carburetor is bathed in warmed air flowing past the engine, so it is unlikely to ice up. However, the R-4360 engines in the B-36 were mounted backwards, in the pusher configuration—air intake/carburetor/28 cylinders/propeller. The carburetor was now in front of the engine, so it could not benefit from engine heat. This placement also made more traditional short-term carburetor heat

Carburetor, carburettor, carburator, carburettor heat (usually abbreviated to 'carb heat') is a system used in automobile and piston-powered light aircraft engines to prevent or clear carburetor icing. It consists of a moveable flap which draws h ...

systems unsuitable. Hence, when intake air was cold and humid, ice gradually obstructed the carburetor air intake, which in turn gradually increased the richness of the air/fuel mixture until the unburned fuel in the exhaust

Exhaust, exhaustive, or exhaustion may refer to:

Law

*Exhaustion of intellectual property rights, limits to intellectual property rights in patent and copyright law

** Exhaustion doctrine, in patent law

** Exhaustion doctrine under U.S. law, in ...

caught fire. Three engine fires of this nature led to the first loss of an American nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

when a B-36 crashed

"Crashed" is the third U.S. rock Single (music), single, (the fifth overall), from the band Daughtry (band), Daughtry's debut album. It was released only to U.S. rock stations on September 5, 2007. Upon its release the song got adds at those stat ...

in February 1950.

Crew experience

Training missions were typically in two parts, a 40-hour flight—followed by time on the ground for refueling and maintenance—and then a 24-hour second flight. With a sufficiently light load, the B-36 could fly at least 10,000 mi (16,000 km) nonstop, and the highest cruising speed of any version, the B-36J-III, was at 230 mph (380 km/h). Engaging the jet engines could raise the cruising speed to over 400 mph (650 km/h). Hence, a 40-hour mission, with the jets used only for takeoff and climbing, flew about 9,200 mi (15,000 km).

Due to its massive size, the B-36 was never considered sprightly or agile; Lieutenant General James Edmundson likened it to "sitting on your front porch and flying your house around". Crew compartments were nonetheless cramped, especially when occupied for 24 hours by a crew of 15 in full flight kit.

War missions would have been one-way, taking off from forward bases in

Training missions were typically in two parts, a 40-hour flight—followed by time on the ground for refueling and maintenance—and then a 24-hour second flight. With a sufficiently light load, the B-36 could fly at least 10,000 mi (16,000 km) nonstop, and the highest cruising speed of any version, the B-36J-III, was at 230 mph (380 km/h). Engaging the jet engines could raise the cruising speed to over 400 mph (650 km/h). Hence, a 40-hour mission, with the jets used only for takeoff and climbing, flew about 9,200 mi (15,000 km).

Due to its massive size, the B-36 was never considered sprightly or agile; Lieutenant General James Edmundson likened it to "sitting on your front porch and flying your house around". Crew compartments were nonetheless cramped, especially when occupied for 24 hours by a crew of 15 in full flight kit.

War missions would have been one-way, taking off from forward bases in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

or Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

, overflying the USSR, and landing in Europe, Morocco, or the Middle East. Veteran crews recall feeling confident in their ability to fly the planned missions, but not to survive weapon delivery, as the aircraft may not have been fast enough to escape the blast. These concerns were borne out by the 1954 Operation Castle

Operation Castle was a United States series of high-yield (high-energy) nuclear tests by Joint Task Force 7 (JTF-7) at Bikini Atoll beginning in March 1954. It followed ''Operation Upshot–Knothole'' and preceded ''Operation Teapot''.

Condu ...

tests, in which B-36s were flown at the combat distance from the detonations of bombs in the 15-megaton range. At distances believed typical of wartime delivery, aircraft suffered extensive flash and blast damage.

Experiments

Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion

The Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) program and the preceding Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft (NEPA) project worked to develop a nuclear propulsion system for aircraft. The United States Army Air Forces initiated Project NEPA on ...

(ANP) program. The ANP program used modified B-36s to study shielding requirements for an airborne reactor to determine whether a nuclear-powered aircraft

A nuclear-powered aircraft is a concept for an aircraft intended to be powered by nuclear energy. The intention was to produce a jet engine that would heat compressed air with heat from fission, instead of heat from burning fuel. During the Col ...

was feasible. Convair modified two B-36s under the MX-1589 project. The Nuclear Test Aircraft was a B-36H-20-CF (serial number 51-5712) that had been damaged in a tornado at Carswell AFB on 1 September 1952. This aircraft, designated the XB-36H (and later NB-36H

The Convair NB-36H was an experimental aircraft that carried a nuclear reactor. It was nicknamed "The Crusader". It was created for the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion program, or the ANP, to show the feasibility of a nuclear-powered bomber. Its d ...

), was modified to carry a , air-cooled nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

in the aft bomb bay, with a four-ton lead disc shield installed in the middle of the aircraft between the reactor and the cockpit. A number of large air intake and exhaust holes were installed in the sides and bottom of the aircraft's rear fuselage to cool the reactor in flight. On the ground, a crane would be used to remove the reactor from the aircraft. To protect the crew, the highly modified cockpit was encased in lead and rubber, with a leaded glass windshield

The windshield (North American English) or windscreen (Commonwealth English) of an aircraft, car, bus, motorbike, truck, train, boat or streetcar is the front window, which provides visibility while protecting occupants from the elements. ...

. The reactor was operational, but did not power the aircraft; its sole purpose was to investigate the effect of radiation on aircraft systems. Between 1955 and 1957, the NB-36H completed 47 test flights and 215 hours of flight time, during 89 of which the reactor was critical.

Other experiments involved providing the B-36 with its own fighter defense in the form of parasite aircraft carried partially or wholly in a bomb bay. One parasite aircraft was the diminutive McDonnell XF-85 Goblin

The McDonnell XF-85 Goblin is an American prototype fighter aircraft conceived during World War II by McDonnell Aircraft. It was intended to deploy from the bomb bay of the giant Convair B-36 bomber as a parasite fighter. The XF-85's intended ...

, which docked using a trapeze system. The concept was tested successfully using a B-29 carrier, but docking proved difficult even for experienced test pilots. Moreover, the XF-85 was seen as no match for contemporary foreign powers' newly developed interceptor aircraft in development and in service; consequently, the project was cancelled.

More successful was the FICON project

The FICON (Fighter Conveyor) program was conducted by the United States Air Force in the 1950s to test the feasibility of a Convair B-36 Peacemaker bomber carrying a Republic F-84 Thunderflash parasite fighter in its bomb bay. Earlier wingtip co ...

, involving a modified B-36 (called a GRB-36D "mothership") and the RF-84K, a fighter modified for reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops ( skirmishe ...

, in a bomb bay. The GRB-36D would ferry the RF-84K to the vicinity of the objective, whereupon the RF-84K would disconnect and begin its mission. Ten GRB-36Ds and 25 RF-84Ks were built and had limited service in 1955–1956.

Projects Tip Tow and Tom-Tom involved docking F-84s to the wingtips of B-29s and B-36s. The hope was that the increased aspect ratio of the combined aircraft would result in a greater range. Project Tip Tow was cancelled when an EF-84D and a specially modified test EB-29A crashed, killing everyone on both aircraft. This accident was attributed to the EF-84D flipping over onto the wing of the EB-29A. Project Tom-Tom, involving RF-84Fs and a GRB-36D from the FICON project (redesignated JRB-36F), continued for a few months after this crash, but was also cancelled due to the violent turbulence

In fluid dynamics, turbulence or turbulent flow is fluid motion characterized by chaotic changes in pressure and flow velocity. It is in contrast to a laminar flow, which occurs when a fluid flows in parallel layers, with no disruption between ...

induced by the wingtip vortices

Wingtip vortices are circular patterns of rotating air left behind a wing as it generates lift.Clancy, L.J., ''Aerodynamics'', section 5.14 One wingtip vortex trails from the tip of each wing. Wingtip vortices are sometimes named ''trailing ...

of the B-36.Lockett, Brian"Parasite Fighter Programs: Project Tom-Tom."

Goleta Air and Space Museum, air-and-space.com. Retrieved: 15 May 2010.

Strategic reconnaissance

One of the SAC's initial missions was to plan strategic aerial reconnaissance on a global scale. The first efforts were in photo-reconnaissance and mapping. Along with the photo-reconnaissance mission, a small

One of the SAC's initial missions was to plan strategic aerial reconnaissance on a global scale. The first efforts were in photo-reconnaissance and mapping. Along with the photo-reconnaissance mission, a small electronic intelligence

Signals intelligence (SIGINT) is intelligence-gathering by interception of '' signals'', whether communications between people (communications intelligence—abbreviated to COMINT) or from electronic signals not directly used in communication ...

cadre was operating. Weather reconnaissance was part of the effort, as was long-range detection, the search for Soviet atomic explosions. In the late 1940s, strategic intelligence on Soviet capabilities and intentions was scarce. Before the development of the Lockheed U-2