pterodactylus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Pterodactylus'' (from Greek () meaning 'winged finger') is an extinct

The

The  In his first description of the Mannheim specimen, Collini did not conclude that it was a flying animal. In fact, Collini could not fathom what kind of animal it might have been, rejecting affinities with the birds or the bats. He speculated that it may have been a sea creature, not for any anatomical reason, but because he thought the ocean depths were more likely to have housed unknown types of animals. The idea that pterosaurs were aquatic animals persisted among a minority of scientists as late as 1830, when the German zoologist

In his first description of the Mannheim specimen, Collini did not conclude that it was a flying animal. In fact, Collini could not fathom what kind of animal it might have been, rejecting affinities with the birds or the bats. He speculated that it may have been a sea creature, not for any anatomical reason, but because he thought the ocean depths were more likely to have housed unknown types of animals. The idea that pterosaurs were aquatic animals persisted among a minority of scientists as late as 1830, when the German zoologist  The German/French scientist Johann Hermann was the one who first stated that ''Pterodactylus'' used its long fourth finger to support a wing membrane. Back in March 1800, Hermann alerted the prominent French scientist

The German/French scientist Johann Hermann was the one who first stated that ''Pterodactylus'' used its long fourth finger to support a wing membrane. Back in March 1800, Hermann alerted the prominent French scientist  Contrary to von Moll's report, the fossil was not missing; it was being studied by Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring, who gave a public lecture about it on December 27, 1810. In January 1811, von Sömmerring wrote a letter to Cuvier deploring the fact that he had only recently been informed of Cuvier's request for information. His lecture was published in 1812, and in it von Sömmerring named the species ''Ornithocephalus antiquus''. The animal was described as being both a bat, and a form in between mammals and birds, i.e. not intermediate in descent but in "affinity" or

Contrary to von Moll's report, the fossil was not missing; it was being studied by Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring, who gave a public lecture about it on December 27, 1810. In January 1811, von Sömmerring wrote a letter to Cuvier deploring the fact that he had only recently been informed of Cuvier's request for information. His lecture was published in 1812, and in it von Sömmerring named the species ''Ornithocephalus antiquus''. The animal was described as being both a bat, and a form in between mammals and birds, i.e. not intermediate in descent but in "affinity" or

''Pterodactylus'' is known from over 30 fossil specimens, and though most belong to juveniles, many preserve complete skeletons. ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' was a relatively small pterosaur, with an estimated adult wingspan of about , based on the only known adult specimen, which is represented by an isolated skull. Other "species" were once thought to have been smaller. However, these smaller specimens have been shown to represent juveniles of ''Pterodactylus'', as well as its contemporary relatives including ''Ctenochasma'', ''

''Pterodactylus'' is known from over 30 fossil specimens, and though most belong to juveniles, many preserve complete skeletons. ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' was a relatively small pterosaur, with an estimated adult wingspan of about , based on the only known adult specimen, which is represented by an isolated skull. Other "species" were once thought to have been smaller. However, these smaller specimens have been shown to represent juveniles of ''Pterodactylus'', as well as its contemporary relatives including ''Ctenochasma'', '' ''Pterodactylus'', like related pterosaurs, had a crest on its skull composed mainly of soft tissues. In adult ''Pterodactylus'', this crest extended between the back edge of the antorbital fenestra and the back of the skull. In at least one specimen, the crest had a short bony base, also seen in related pterosaurs like ''Germanodactylus''. Solid crests have only been found on large, fully adult specimens of ''Pterodactylus'', indicating that this was a display structure that became larger and more well developed as individuals reached maturity. In 2013, pterosaur researcher

''Pterodactylus'', like related pterosaurs, had a crest on its skull composed mainly of soft tissues. In adult ''Pterodactylus'', this crest extended between the back edge of the antorbital fenestra and the back of the skull. In at least one specimen, the crest had a short bony base, also seen in related pterosaurs like ''Germanodactylus''. Solid crests have only been found on large, fully adult specimens of ''Pterodactylus'', indicating that this was a display structure that became larger and more well developed as individuals reached maturity. In 2013, pterosaur researcher

Like other pterosaurs (most notably '' Rhamphorhynchus''), ''Pterodactylus'' specimens can vary considerably based on age or level of maturity. Both the proportions of the limb bones, size and shape of the skull, and size and number of teeth changed as the animals grew. Historically, this has led to various growth stages (including growth stages of related pterosaurs) being mistaken for new species of ''Pterodactylus''. Several detailed studies using various methods to measure growth curves among known specimens have suggested that there is actually only one valid species of ''Pterodactylus'', ''P. antiquus''.

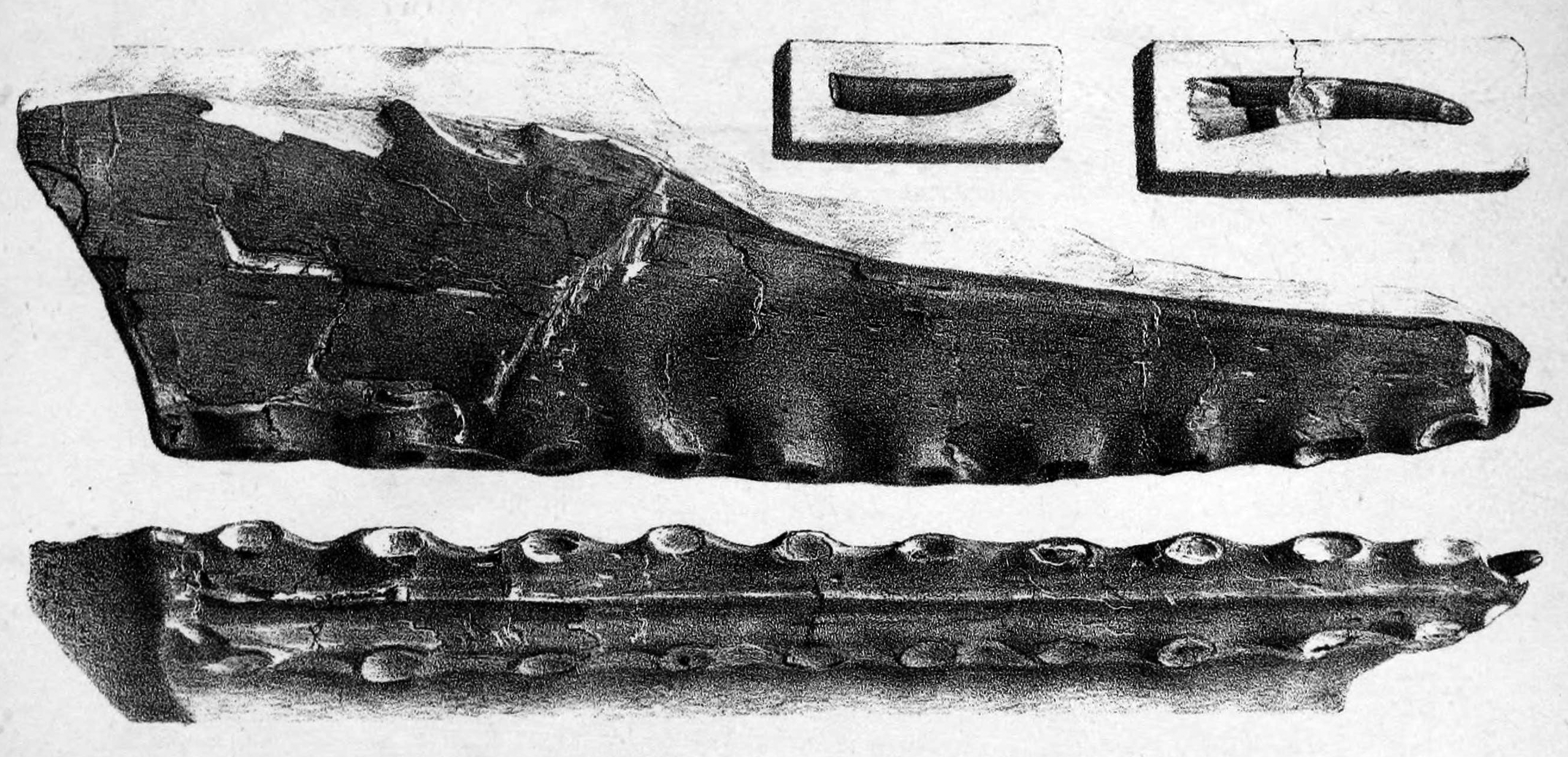

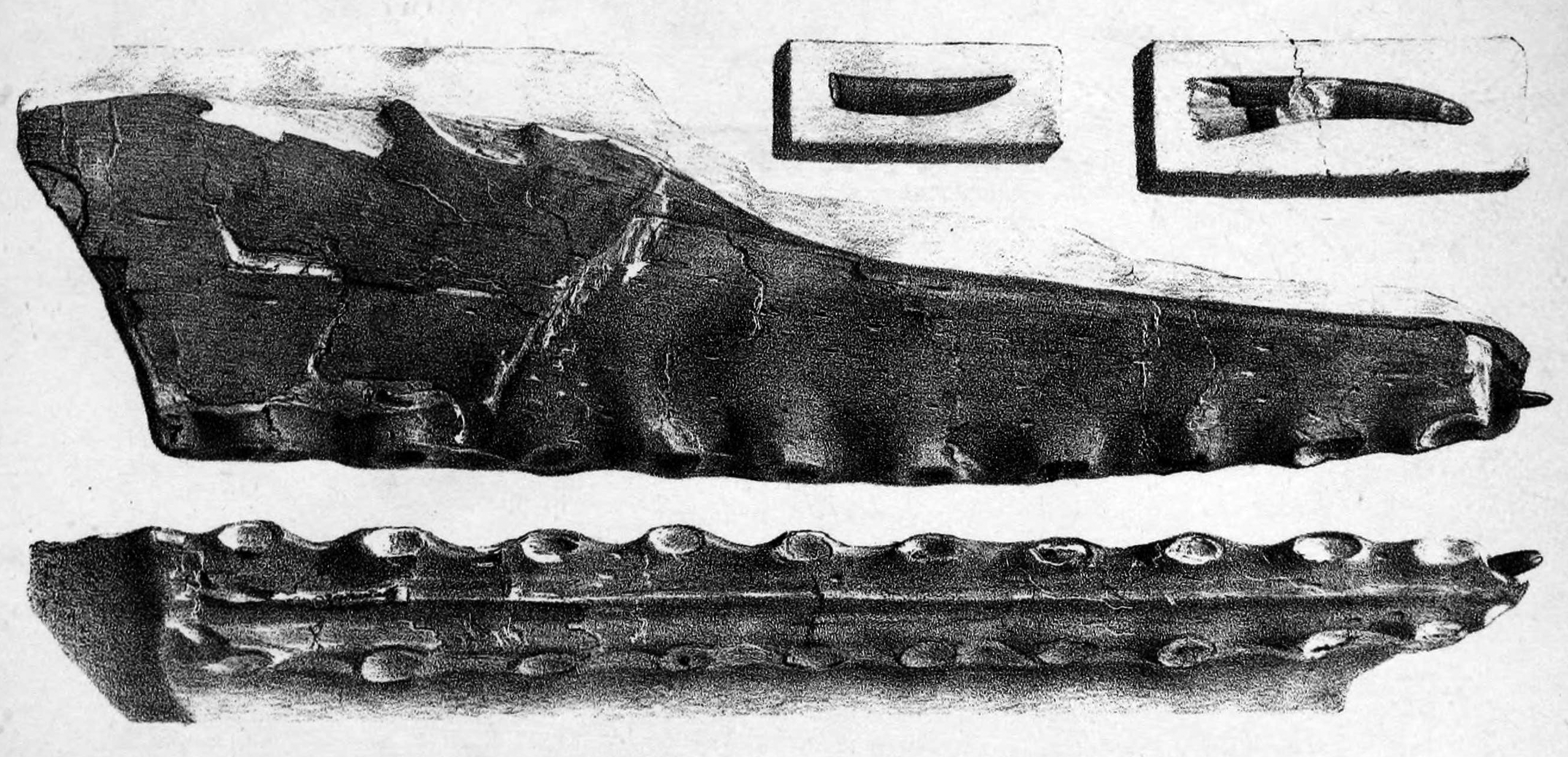

The youngest immature specimens of ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' (alternately interpreted as young specimens of the distinct species ''P. kochi'') have a small number of teeth, as few as 15 in some, and the teeth have a relatively broad base. The teeth of other ''P. antiquus'' specimens are both narrower and more numerous (up to 90 teeth are present in several specimens).

''Pterodactylus'' specimens can be divided into two distinct year classes. In the first year class, the skulls are only in length. The second year class is characterized by skulls of around long, but are still immature however. These first two size groups were once classified as juveniles and adults of the species ''P. kochi'', until further study showed that even the supposed "adults" were immature, and possibly belong to a distinct genus. A third year class is represented by specimens of the "traditional" ''P. antiquus'', as well as a few isolated, large specimens once assigned to ''P. kochi'' that overlap ''P. antiquus'' in size. However, all specimens in this third year class also show sign of immaturity. Fully mature ''Pterodactylus'' specimens remain unknown, or may have been mistakenly classified as a different genus.

Like other pterosaurs (most notably '' Rhamphorhynchus''), ''Pterodactylus'' specimens can vary considerably based on age or level of maturity. Both the proportions of the limb bones, size and shape of the skull, and size and number of teeth changed as the animals grew. Historically, this has led to various growth stages (including growth stages of related pterosaurs) being mistaken for new species of ''Pterodactylus''. Several detailed studies using various methods to measure growth curves among known specimens have suggested that there is actually only one valid species of ''Pterodactylus'', ''P. antiquus''.

The youngest immature specimens of ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' (alternately interpreted as young specimens of the distinct species ''P. kochi'') have a small number of teeth, as few as 15 in some, and the teeth have a relatively broad base. The teeth of other ''P. antiquus'' specimens are both narrower and more numerous (up to 90 teeth are present in several specimens).

''Pterodactylus'' specimens can be divided into two distinct year classes. In the first year class, the skulls are only in length. The second year class is characterized by skulls of around long, but are still immature however. These first two size groups were once classified as juveniles and adults of the species ''P. kochi'', until further study showed that even the supposed "adults" were immature, and possibly belong to a distinct genus. A third year class is represented by specimens of the "traditional" ''P. antiquus'', as well as a few isolated, large specimens once assigned to ''P. kochi'' that overlap ''P. antiquus'' in size. However, all specimens in this third year class also show sign of immaturity. Fully mature ''Pterodactylus'' specimens remain unknown, or may have been mistakenly classified as a different genus.

The distinct year classes of ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' specimens show that this species, like the contemporary ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'', likely bred seasonally and grew consistently during its lifetime. A new generation of 1st year class ''P. antiquus'' would have been produced seasonally, and reached 2nd-year size by the time the next generation hatched, creating distinct 'clumps' of similarly-sized and aged individuals in the fossil record. The smallest size class probably consisted of individuals that had just begun to fly and were less than one year old. The second year class represents individuals one to two years old, and the rare third year class is composed of specimens over two years old. This growth pattern is similar to modern

The distinct year classes of ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' specimens show that this species, like the contemporary ''Rhamphorhynchus muensteri'', likely bred seasonally and grew consistently during its lifetime. A new generation of 1st year class ''P. antiquus'' would have been produced seasonally, and reached 2nd-year size by the time the next generation hatched, creating distinct 'clumps' of similarly-sized and aged individuals in the fossil record. The smallest size class probably consisted of individuals that had just begun to fly and were less than one year old. The second year class represents individuals one to two years old, and the rare third year class is composed of specimens over two years old. This growth pattern is similar to modern

Specimens of ''Pterodactylus'' have been found mainly in the Solnhofen limestone (geologically known as the Altmühltal Formation) of

Specimens of ''Pterodactylus'' have been found mainly in the Solnhofen limestone (geologically known as the Altmühltal Formation) of

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

of pterosaur

Pterosaurs (; from Greek ''pteron'' and ''sauros'', meaning "wing lizard") is an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order, Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 to ...

s. It is thought to contain only a single species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

, ''Pterodactylus antiquus'', which was the first pterosaur to be named and identified as a flying reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates (lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalians ( ...

.

Fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

remains of ''Pterodactylus'' have primarily been found in the Solnhofen limestone of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, which dates from the Late Jurassic period (early Tithonian

In the geological timescale, the Tithonian is the latest age of the Late Jurassic Epoch and the uppermost stage of the Upper Jurassic Series. It spans the time between 152.1 ± 4 Ma and 145.0 ± 4 Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the K ...

stage), about 150.8 to 148.5 million years ago. More fragmentary remains of ''Pterodactylus'' have tentatively been identified from elsewhere in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

.

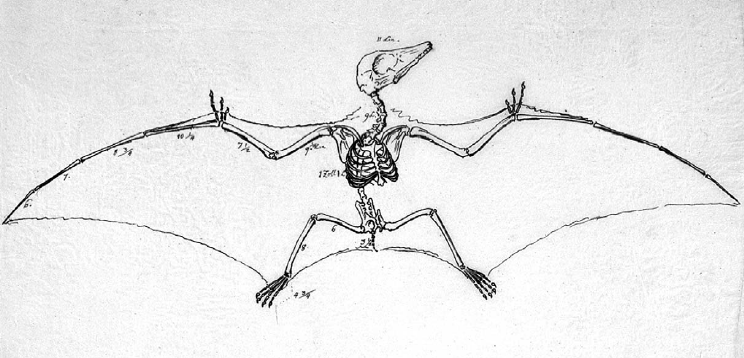

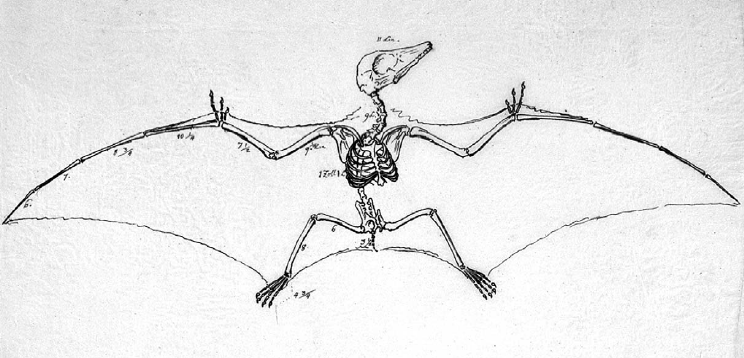

''Pterodactylus'' was a generalist carnivore that probably fed on a variety of invertebrates and vertebrates. Like all pterosaurs, ''Pterodactylus'' had wings formed by a skin and muscle membrane stretching from its elongated fourth finger to its hind limbs. It was supported internally by collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

fibres and externally by keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, ho ...

ous ridges. ''Pterodactylus'' was a small pterosaur compared to other famous genera such as ''Pteranodon

''Pteranodon'' (); from Ancient Greek (''pteron'', "wing") and (''anodon'', "toothless") is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with ''P. longiceps'' having a wingspan of . They lived during the late Cr ...

'' and ''Quetzalcoatlus

''Quetzalcoatlus'' is a genus of pterosaur known from the Late Cretaceous period of North America (Maastrichtian stage); its members were among the largest known flying animals of all time. ''Quetzalcoatlus'' is a member of the Azhdarchidae, ...

'', and it also lived earlier, during the Late Jurassic period, while both ''Pteranodon'' and ''Quetzalcoatlus'' lived during the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', the ...

. ''Pterodactylus'' lived alongside other small pterosaurs such as the well-known '' Rhamphorhynchus'', as well as other genera such as '' Scaphognathus'', '' Anurognathus'' and '' Ctenochasma''. ''Pterodactylus'' is classified as an early-branching member of the ctenochasmatid lineage, within the pterosaur clade Pterodactyloidea.

Discovery and history

The

The type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wiktionary:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to a ...

of the animal now known as ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' was the first pterosaur fossil ever to be identified. The first ''Pterodactylus'' specimen was described by the Italian scientist in 1784, based on a fossil skeleton that had been unearthed from the Solnhofen limestone of Bavaria. Collini was the curator of the , or nature cabinet of curiosities (a precursor to the modern concept of the natural history museum), in the palace of Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria

Charles Theodore (german: link=no, Karl Theodor; 11 December 1724 – 16 February 1799) reigned as Prince-elector and Count Palatine from 1742, as Duke of Jülich and Berg from 1742 and also as prince-elector and Duke of Bavaria from 1777 to his ...

at Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's 2 ...

. The specimen had been given to the collection by Count around 1780, having been recovered from a lithographic limestone

Lithographic limestone is hard limestone that is sufficiently fine-grained, homogeneous and defect free to be used for lithography.

Geologists use the term "lithographic texture" to refer to a grain size under 1/250 mm.

The term "sublithog ...

quarry in . The actual date of the specimen's discovery and entry into the collection is unknown however, and it was not mentioned in a catalogue of the collection taken in 1767, so it must have been acquired at some point between that date and its 1784 description by Collini. This makes it potentially the earliest documented pterosaur find; the "Pester Exemplar" of the genus '' Aurorazhdarcho'' was described in 1779 and possibly discovered earlier than the Mannheim specimen, but it was at first considered to be a fossilized crustacean, and it was not until 1856 that this species was properly described as a pterosaur by German paleontologist .

In his first description of the Mannheim specimen, Collini did not conclude that it was a flying animal. In fact, Collini could not fathom what kind of animal it might have been, rejecting affinities with the birds or the bats. He speculated that it may have been a sea creature, not for any anatomical reason, but because he thought the ocean depths were more likely to have housed unknown types of animals. The idea that pterosaurs were aquatic animals persisted among a minority of scientists as late as 1830, when the German zoologist

In his first description of the Mannheim specimen, Collini did not conclude that it was a flying animal. In fact, Collini could not fathom what kind of animal it might have been, rejecting affinities with the birds or the bats. He speculated that it may have been a sea creature, not for any anatomical reason, but because he thought the ocean depths were more likely to have housed unknown types of animals. The idea that pterosaurs were aquatic animals persisted among a minority of scientists as late as 1830, when the German zoologist Johann Georg Wagler

Johann Georg Wagler (28 March 1800 – 23 August 1832) was a German herpetologist and ornithologist.

Wagler was assistant to Johann Baptist von Spix, and gave lectures in zoology at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich after it was moved ...

published a text on "amphibians" which included an illustration of ''Pterodactylus'' using its wings as flippers. Wagler went so far as to classify ''Pterodactylus'', along with other aquatic vertebrates (namely plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared ...

s, ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

s, and monotreme

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals (Eutheria), and marsupials (Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their brain ...

s), in the class Gryphi, between birds and mammals.

The German/French scientist Johann Hermann was the one who first stated that ''Pterodactylus'' used its long fourth finger to support a wing membrane. Back in March 1800, Hermann alerted the prominent French scientist

The German/French scientist Johann Hermann was the one who first stated that ''Pterodactylus'' used its long fourth finger to support a wing membrane. Back in March 1800, Hermann alerted the prominent French scientist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

to the existence of Collini's fossil, believing that it had been captured by the occupying armies of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and sent to the French collections in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

(and perhaps to Cuvier himself) as war booty; at the time special French political commissars systematically seized art treasures and objects of scientific interest. Hermann sent Cuvier a letter containing his own interpretation of the specimen (though he had not examined it personally), which he believed to be a mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

, including the first known life restoration of a pterosaur. Hermann restored the animal with wing membranes extending from the long fourth finger to the ankle and a covering of fur (neither wing membranes nor fur had been preserved in the specimen). Hermann also added a membrane between the neck and wrist, as is the condition in bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and πτερόν''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most bi ...

s. Cuvier agreed with this interpretation, and at Hermann's suggestion, Cuvier became the first to publish these ideas in December 1800 in a very short description. However, contrary to Hermann, Cuvier was convinced the animal was a reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates (lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalians ( ...

. The specimen had not in fact been seized by the French. Rather, in 1802, following the death of Charles Theodore, it was brought to Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

, where Baron Johann Paul Carl von Moll had obtained a general exemption of confiscation for the Bavarian collections. Cuvier asked von Moll to study the fossil but was informed it could not be found. In 1809 Cuvier published a somewhat longer description, in which he named the animal ''Petro-Dactyle'', this was a typographical error however, and was later corrected by him to ''Ptéro-Dactyle''. He also refuted a hypothesis by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach that it would have been a shore bird. Cuvier remarked: "It is not possible to doubt that the long finger served to support a membrane that, by lengthening the anterior extremity of this animal, formed a good wing."

Contrary to von Moll's report, the fossil was not missing; it was being studied by Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring, who gave a public lecture about it on December 27, 1810. In January 1811, von Sömmerring wrote a letter to Cuvier deploring the fact that he had only recently been informed of Cuvier's request for information. His lecture was published in 1812, and in it von Sömmerring named the species ''Ornithocephalus antiquus''. The animal was described as being both a bat, and a form in between mammals and birds, i.e. not intermediate in descent but in "affinity" or

Contrary to von Moll's report, the fossil was not missing; it was being studied by Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring, who gave a public lecture about it on December 27, 1810. In January 1811, von Sömmerring wrote a letter to Cuvier deploring the fact that he had only recently been informed of Cuvier's request for information. His lecture was published in 1812, and in it von Sömmerring named the species ''Ornithocephalus antiquus''. The animal was described as being both a bat, and a form in between mammals and birds, i.e. not intermediate in descent but in "affinity" or archetype

The concept of an archetype (; ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main model that ot ...

. Cuvier disagreed, and the same year in his ''Ossemens fossiles'' provided a lengthy description in which he restated that the animal was a reptile. It was not until 1817 that a second specimen of ''Pterodactylus'' came to light, again from Solnhofen

Solnhofen is a municipality in the district of Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen in the region of Middle Franconia in the ' of Bavaria in Germany. It is in the Altmühl valley.

The local area is famous in geology and palaeontology for Solnhofen limest ...

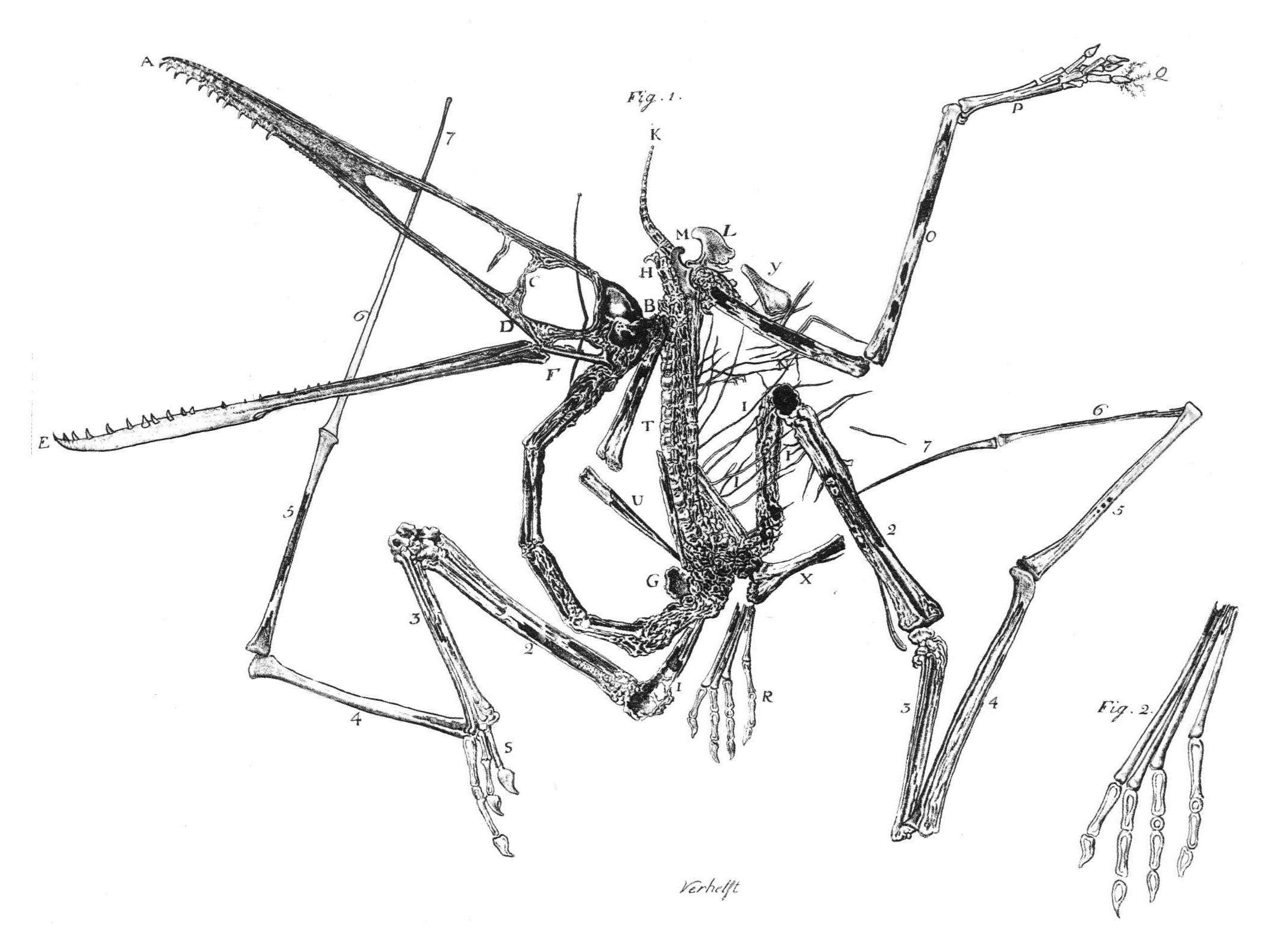

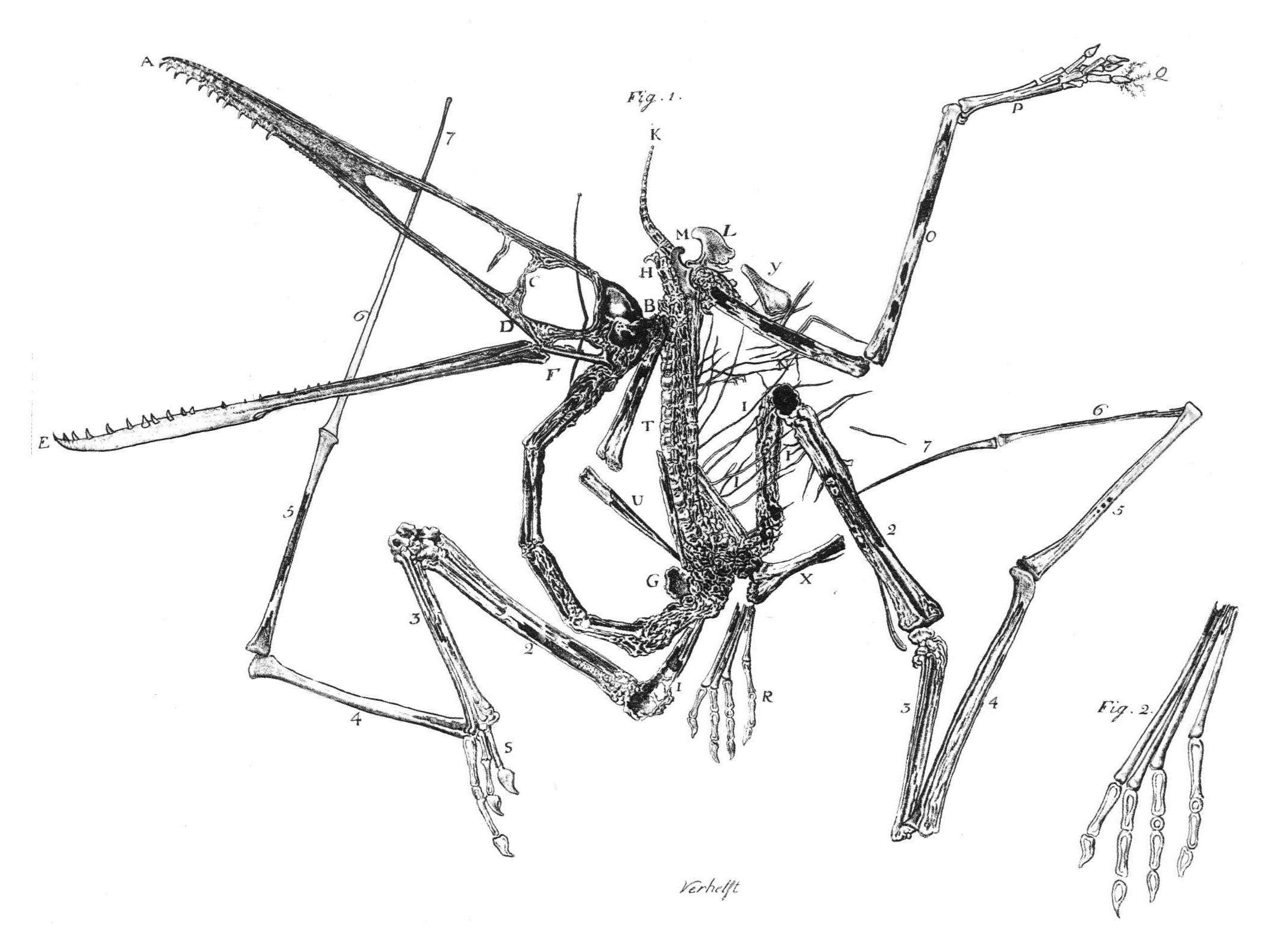

. This tiny specimen was that year described by von Sömmerring as '' Ornithocephalus brevirostris'', named for its short snout, now understood to be a juvenile character (this specimen is now thought to represent a juvenile specimen of a different genus, probably '' Ctenochasma''). He provided a restoration of the skeleton, the first one published for any pterosaur. This restoration was very inaccurate, von Sömmerring mistaking the long metacarpals for the bones of the lower arm, the lower arm for the humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

, this upper arm for the breast bone

The sternum or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels from injury. Shap ...

and this sternum again for the shoulder blade

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either ...

s. Sömmerring did not change his opinion that these forms were bats and this "bat model" for interpreting pterosaurs would remain influential long after a consensus had been reached around 1860 that they were reptiles. The standard assumptions were that pterosaurs were quadrupedal, clumsy on the ground, furred, warmblooded and had a wing membrane reaching the ankle. Some of these elements have been confirmed, some refuted by modern research, while others remain disputed.

In 1815, the generic name ''Ptéro-Dactyle'' was latinized to ''Pterodactylus'' by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque

Constantine Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz (; October 22, 1783September 18, 1840) was a French 19th-century polymath born near Constantinople in the Ottoman Empire and self-educated in France. He traveled as a young man in the United States, ultimat ...

. Unaware of Rafinesque's publication however, Cuvier himself in 1819 latinized the name ''Ptéro-Dactyle'' again to ''Pterodactylus'', but the specific name he then gave, ''longirostris'', has to give precedence to von Sömmerring's ''antiquus''. In 1888, English naturalist Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was an English naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history.

Biography

Richard Lydekker was born at Tavistock Square in London. His father was Gerard Wolfe Lydekker, ...

designated ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' as the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

of ''Pterodactylus'', and considered ''Ornithocephalus antiquus'' a synonym. He also designated specimen BSP AS.I.739 as the holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

of the genus.

Description

''Pterodactylus'' is known from over 30 fossil specimens, and though most belong to juveniles, many preserve complete skeletons. ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' was a relatively small pterosaur, with an estimated adult wingspan of about , based on the only known adult specimen, which is represented by an isolated skull. Other "species" were once thought to have been smaller. However, these smaller specimens have been shown to represent juveniles of ''Pterodactylus'', as well as its contemporary relatives including ''Ctenochasma'', ''

''Pterodactylus'' is known from over 30 fossil specimens, and though most belong to juveniles, many preserve complete skeletons. ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' was a relatively small pterosaur, with an estimated adult wingspan of about , based on the only known adult specimen, which is represented by an isolated skull. Other "species" were once thought to have been smaller. However, these smaller specimens have been shown to represent juveniles of ''Pterodactylus'', as well as its contemporary relatives including ''Ctenochasma'', ''Germanodactylus

''Germanodactylus'' ("German finger") is a genus of germanodactylid pterodactyloid pterosaur from Upper Jurassic-age rocks of Germany, including the Solnhofen Limestone. Its specimens were long thought to pertain to '' Pterodactylus''. The hea ...

'', '' Aurorazhdarcho'', '' Gnathosaurus'', and hypothetically '' Aerodactylus'' if this genus is truly valid.

The skulls of adult ''Pterodactylus'' were long and thin, with about 90 narrow and conical teeth. The teeth extended back from the tips of both jaws, and became smaller farther away from the jaw tips, this was unlike the ones seen in most relatives, where teeth were absent in the upper jaw tip, and were relatively uniform in size. The teeth of ''Pterodactylus'' also extended farther back into the jaw compared to close relatives, and some were present below the front of the ''nasoantorbital fenestra'', which is the largest opening in the skull. Another autapomorphy

In phylogenetics, an autapomorphy is a distinctive feature, known as a derived trait, that is unique to a given taxon. That is, it is found only in one taxon, but not found in any others or outgroup taxa, not even those most closely related to t ...

that ''Pterodactylus'' has is that the skull and jaws were straight, which are unlike the upwardly curved jaws seen in the related ctenochasmatids.

''Pterodactylus'', like related pterosaurs, had a crest on its skull composed mainly of soft tissues. In adult ''Pterodactylus'', this crest extended between the back edge of the antorbital fenestra and the back of the skull. In at least one specimen, the crest had a short bony base, also seen in related pterosaurs like ''Germanodactylus''. Solid crests have only been found on large, fully adult specimens of ''Pterodactylus'', indicating that this was a display structure that became larger and more well developed as individuals reached maturity. In 2013, pterosaur researcher

''Pterodactylus'', like related pterosaurs, had a crest on its skull composed mainly of soft tissues. In adult ''Pterodactylus'', this crest extended between the back edge of the antorbital fenestra and the back of the skull. In at least one specimen, the crest had a short bony base, also seen in related pterosaurs like ''Germanodactylus''. Solid crests have only been found on large, fully adult specimens of ''Pterodactylus'', indicating that this was a display structure that became larger and more well developed as individuals reached maturity. In 2013, pterosaur researcher S. Christopher Bennett

S is the nineteenth letter of the English alphabet.

S may also refer to:

History

* an Anglo-Saxon charter's number in Peter Sawyer's, catalogue Language and linguistics

* Long s (ſ), a form of the lower-case letter s formerly used where "s ...

noted that other authors claimed that the soft tissue crest of ''Pterodactylus'' extended backward behind the skull; Bennett himself, however, didn't find any evidence for the crest extending past the back of the skull. Two specimens of ''P. antiquus'' (the holotype specimen BSP AS I 739 and the incomplete skull BMMS 7, the largest known skull of ''P. antiquus'') have a low bony crest on their skulls; in BMMS 7 it is 47.5 mm long (1.87 inches, more or less 24% of the estimated total length of its skull) and has a maximum height of 0.9 mm (0.035 inches) above the orbit. Several specimens previously referred to ''P. antiquus'' preserved evidence of the soft tissue extensions of these crests, including an "occipital lappet", a flexible, tab-like structure extending from the back of the skull. Most of these specimens have been reclassified in the related species ''Aerodactylus scolopaciceps'', which may however be nothing more than a junior synonym. Even if ''Aerodactylus'' were valid, at least one specimen with these features is still considered to belong to ''Pterodactylus'', BSP 1929 I 18, which has an occipital lappet similar to the proposed ''Aerodactylus'' definition, and also possesses a small triangular soft tissue crest with the peak of the crest positioned above the eyes.

Paleobiology

Life history

Growth and breeding seasons

crocodilia

Crocodilia (or Crocodylia, both ) is an order of mostly large, predatory, semiaquatic reptiles, known as crocodilians. They first appeared 95 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous period ( Cenomanian stage) and are the closest living ...

ns, rather than the rapid growth of modern bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

s.

Daily activity patterns

Comparisons between the scleral rings of ''Pterodactylus antiquus'' and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been diurnal. This may also indicate niche partitioning with contemporary pterosaurs inferred to benocturnal

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

, such as ''Ctenochasma'' and ''Rhamphorhynchus''.

Diet

Based on the shape, size, and arrangement of its teeth, ''Pterodactylus'' has long been recognized as a carnivore specializing in small animals. A 2020 study of pterosaur tooth wear supported the hypothesis that ''Pterodactylus'' preyed mainly on invertebrates and had a generalist feeding strategy, indicated by a relatively high bite force.Bestwick, J., Unwin, D.M., Butler, R.J. et al. Dietary diversity and evolution of the earliest flying vertebrates revealed by dental microwear texture analysis. Nat Commun 11, 5293 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19022-2Paleoecology

Specimens of ''Pterodactylus'' have been found mainly in the Solnhofen limestone (geologically known as the Altmühltal Formation) of

Specimens of ''Pterodactylus'' have been found mainly in the Solnhofen limestone (geologically known as the Altmühltal Formation) of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. The main composition of this formation is fine-grained limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

that originated mainly from the nearby towns Solnhofen

Solnhofen is a municipality in the district of Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen in the region of Middle Franconia in the ' of Bavaria in Germany. It is in the Altmühl valley.

The local area is famous in geology and palaeontology for Solnhofen limest ...

and Eichstätt, which is formed by mud silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel when ...

deposits. The Solnhofen Limestone is a diverse Lagerstätte

A Lagerstätte (, from ''Lager'' 'storage, lair' '' Stätte'' 'place'; plural ''Lagerstätten'') is a sedimentary deposit that exhibits extraordinary fossils with exceptional preservation—sometimes including preserved soft tissues. These for ...

that contains a wide range of different creatures, including highly detailed fossilized imprints of soft bodied organisms such as jellyfish

Jellyfish and sea jellies are the informal common names given to the medusa-phase of certain gelatinous members of the subphylum Medusozoa, a major part of the phylum Cnidaria. Jellyfish are mainly free-swimming marine animals with umbrella- ...

es. Abundant specimens of pterosaurs similar to ''Pterodactylus'' were also found within the formation, these include the rhamphorhynchids ''Rhamphorhynchus'' and '' Scaphognathus'', several gallodactylids such as ''Aerodactylus'', '' Ardeadactylus'', ''Aurorazhdarcho'' and '' Cycnorhamphus'', the ctenochasmatids ''Ctenochasma'' and ''Gnathosaurus'', the anurognathid '' Anurognathus'', the germanodactylid ''Germanodactylus'', as well as the basal euctenochasmatian '' Diopecephalus''. Fossil remains of the dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s ''Archaeopteryx

''Archaeopteryx'' (; ), sometimes referred to by its German name, "" ( ''Primeval Bird''), is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The name derives from the ancient Greek (''archaīos''), meaning "ancient", and (''ptéryx''), meaning "feather" ...

'' and '' Compsognathus'' were also found within the limestone, these specimens were related to early evolution of feathers, since they were some of the only ones that had them during the Jurassic period. Various lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

remains were also found alongside those of ''Pterodactylus'', with several specimens assigned to ''Ardeosaurus

''Ardeosaurus'' is an extinct genus of basal lizards, known from fossils found in the Late Jurassic Solnhofen Plattenkalk of Bavaria, southern Germany. It was originally thought to have been a species of ''Homeosaurus''.

''Ardeosaurus'' was ...

'', ''Bavarisaurus

''Bavarisaurus'' ('Bavarian lizard') is an extinct genus of basal squamate found in the Solnhofen limestone near Bavaria, Germany.Eichstaettisaurus''.

Initial classifications for ''Pterodactylus'' started when paleontologist Hermann von Meyer used the name Pterodactyli to contain ''Pterodactylus'' and other pterosaurs known at the time. This was emended to the

Initial classifications for ''Pterodactylus'' started when paleontologist Hermann von Meyer used the name Pterodactyli to contain ''Pterodactylus'' and other pterosaurs known at the time. This was emended to the

Numerous species have been assigned to ''Pterodactylus'' in the years since its discovery. In the first half of the 19th century any new pterosaur species would be named ''Pterodactylus'', which thus became a " wastebasket taxon". Even after clearly different forms had later been given their own generic name, new species would be created from the very productive sites, throughout Europe and North America, often based on only slightly different material.

The earliest reassignments of pterosaur species to ''Pterodactylus'' started in 1825, with the description of ''Rhamphorhynchus''; fossil collector Georg Graf zu Münster alerted the German paleontologist Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring about several distinct fossil specimens, Sömmerring thought that they belonged to an ancient bird. Further fossil preparations had uncovered teeth, to which Graf zu Münster created a skull cast. He later sent the cast to Professor Georg August Goldfuss, who recognized it as a pterosaur, specifically a species of ''Pterodactylus''. At the time however, most paleontologists incorrectly consider the genus ''Ornithocephalus'' () to be the valid name for ''Pterodactylus'', and therefore the specimen found was named as ''Ornithocephalus Münsteri'', which was first mentioned by Graf zu Münster himself. Another specimen was found and described by Graf zu Münster in 1839, he assigned this specimen to a new separate species called ''Ornithocephalus longicaudus''; the

Numerous species have been assigned to ''Pterodactylus'' in the years since its discovery. In the first half of the 19th century any new pterosaur species would be named ''Pterodactylus'', which thus became a " wastebasket taxon". Even after clearly different forms had later been given their own generic name, new species would be created from the very productive sites, throughout Europe and North America, often based on only slightly different material.

The earliest reassignments of pterosaur species to ''Pterodactylus'' started in 1825, with the description of ''Rhamphorhynchus''; fossil collector Georg Graf zu Münster alerted the German paleontologist Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring about several distinct fossil specimens, Sömmerring thought that they belonged to an ancient bird. Further fossil preparations had uncovered teeth, to which Graf zu Münster created a skull cast. He later sent the cast to Professor Georg August Goldfuss, who recognized it as a pterosaur, specifically a species of ''Pterodactylus''. At the time however, most paleontologists incorrectly consider the genus ''Ornithocephalus'' () to be the valid name for ''Pterodactylus'', and therefore the specimen found was named as ''Ornithocephalus Münsteri'', which was first mentioned by Graf zu Münster himself. Another specimen was found and described by Graf zu Münster in 1839, he assigned this specimen to a new separate species called ''Ornithocephalus longicaudus''; the  Beginning in 1846, many pterosaur specimens were found near the village of

Beginning in 1846, many pterosaur specimens were found near the village of  Assigning new pterosaur species to ''Pterodactylus'' was not only common in Europe, but also in North America; paleontologists such as

Assigning new pterosaur species to ''Pterodactylus'' was not only common in Europe, but also in North America; paleontologists such as

The only well-known and well-supported species left by the first decades of the 21st century were ''P. antiquus'' and ''P. kochi''. However, most studies between 1995 and 2010 found little reason to separate even these two species, and treated them as synonymous. More recent studies of pterosaur relationships have found anurognathids and pterodactyloids to be sister groups, which would limit the more inclusive group

The only well-known and well-supported species left by the first decades of the 21st century were ''P. antiquus'' and ''P. kochi''. However, most studies between 1995 and 2010 found little reason to separate even these two species, and treated them as synonymous. More recent studies of pterosaur relationships have found anurognathids and pterodactyloids to be sister groups, which would limit the more inclusive group

''Pterodactylus'' is regarded as one of the most iconic prehistoric creatures, with multiple appearances in books, movies, as well as television series and several videogames. The informal name "pterodactyl" is sometimes used to refer to any kind of animal belonging to the order Pterosauria, though most of the times to ''Pterodactylus'', as it's the most well-known member of the group. The popular aspect of ''Pterodactylus'' consists of an elongated head crest, and potentially large wings. Studies of ''Pterodactylus'' however, conclude that it may even lack a bony cranial crest, though several analysis have proven that ''Pterodactylus'' may in fact have a crest made up of soft tissue instead of bone.

''Pterodactylus'' is the star character of the 2005

''Pterodactylus'' is regarded as one of the most iconic prehistoric creatures, with multiple appearances in books, movies, as well as television series and several videogames. The informal name "pterodactyl" is sometimes used to refer to any kind of animal belonging to the order Pterosauria, though most of the times to ''Pterodactylus'', as it's the most well-known member of the group. The popular aspect of ''Pterodactylus'' consists of an elongated head crest, and potentially large wings. Studies of ''Pterodactylus'' however, conclude that it may even lack a bony cranial crest, though several analysis have proven that ''Pterodactylus'' may in fact have a crest made up of soft tissue instead of bone.

''Pterodactylus'' is the star character of the 2005

Crocodylomorph

Crocodylomorpha is a group of pseudosuchian archosaurs that includes the crocodilians and their extinct relatives. They were the only members of Pseudosuchia to survive the end-Triassic extinction.

During Mesozoic and early Cenozoic times, cro ...

specimens were widely distributed within the fossil site, most were assigned to the metriorhynchid

Metriorhynchidae is an extinct family of specialized, aquatic metriorhynchoid crocodyliforms from the Middle Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous period (Bajocian to early Aptian) of Europe, North America and South America. The name Metriorhynchidae ...

genera ''Cricosaurus

''Cricosaurus'' is an extinct genus of marine crocodyliforms of the Late Jurassic. belonging to the family Metriorhynchidae. The genus was established by Johann Andreas Wagner in 1858 for three skulls from the Tithonian (Late Jurassic) of German ...

'', '' Dakosaurus'', ''Geosaurus

''Geosaurus'' is an extinct genus of marine crocodyliform within the family Metriorhynchidae, that lived during the Late Jurassic and the Early Cretaceous. ''Geosaurus'' was a carnivore that spent much, if not all, its life out at sea. No ''Geosa ...

'' and ''Rhacheosaurus

''Rhacheosaurus'' is an extinct genus of marine crocodyliform belonging to the family Metriorhynchidae. The genus was established by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer in 1831 for skeletal remains from the Tithonian (Late Jurassic) of Germany. ...

''. These genera are colloquially called as marine or sea crocodiles due to their similar built. The turtle genera '' Eurysternum'' and '' Paleomedusa'' were also found within the formation. Fossils of the ichthyosaur

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, altho ...

''Aegirosaurus

''Aegirosaurus'' is an extinct genus of platypterygiine ophthalmosaurid ichthyosaurs known from the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous of Europe. It was originally named as a species of ''Ichthyosaurus''.

Discovery and species

Originally describe ...

'' also appeared to be present in the site, as well as fish remains, with many specimens assigned to ray-finned fish

Actinopterygii (; ), members of which are known as ray-finned fishes, is a class of bony fish. They comprise over 50% of living vertebrate species.

The ray-finned fishes are so called because their fins are webs of skin supported by bony or hor ...

es such as the halecomorph

Halecomorphi is a taxon of ray-finned bony fish in the clade Neopterygii. The sole living Halecomorph is the bowfin (''Amia calva''), but the group contains many extinct species in several families (including Amiidae, Caturidae, Liodesmidae, Sin ...

s '' Lepidotes'', ''Propterus

''Propterus'' is an extinct genus of prehistoric ray-finned fish of the Solnhofen Plattenkalk.

See also

* Prehistoric fish

The evolution of fish began about 530 million years ago during the Cambrian explosion. It was during this time t ...

'', ''Gyrodus

''Gyrodus'' (from el, γύρος , 'curved' and el, ὀδούς 'tooth') is an extinct genus of pycnodontiform ray-finned fish that lived from the late Triassic (Rhaetian) to the middle Cretaceous (Cenomanian).

Distribution

Fossils of ''Gy ...

'', ''Mesturus

Mesturus is an extinct genus of ray-finned fish from the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Pe ...

'', ''Proscinetes

''Proscinetes'' is an extinct genus of prehistoric ray-finned fish from the Jurassic.

See also

* Prehistoric fish

* List of prehistoric bony fish

A ''list'' is any set of items in a row. List or lists may also refer to:

People

* List ( ...

'', ''Caturus

''Caturus'' (from el, κατω , 'down' and el, οὐρά 'tail') is an extinct genus of fishes in the family Caturidae in the order Amiiformes, related to modern bowfin. Fossils of this genus range from 200 to 109 mya. It has been suggested ...

'', '' Ophiopsis'' and '' Ophiopsiella'', the pachycormids ''Asthenocormus

''Asthenocormus'' is an extinct genus of pachycormiform ray-finned fish. A member of the edentulous suspension feeding clade within the Pachycormiformes, fossils have been found in the Upper Jurassic plattenkalks of Bavaria, Germany.'

See ...

'', ''Hypsocormus

''Hypsocormus'' (from el, ῠ̔́ψος , 'height' and el, κορμός 'timber log') is an extinct genus of pachycormid fish from the Middle to Late Jurassic of Europe. Fossils have been found in Germany, France and the UK.

The type specie ...

'' and ''Orthocormus

''Orthocormus'' is an extinct genus of prehistoric pachycormiform bony fish. It is known from three species found in Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) aged plattenkalk deposits in Bavaria, Germany. The species "'' Hypsocormus" tenuirostris'' Woodwar ...

'', as well as the aspidorhynchid ''Aspidorhynchus

''Aspidorhynchus'' (from el, ᾰ̓σπίς 'shield' and el, ῥύγχος 'snout') is an extinct genus of ray-finned fish from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Fossils have been found in Europe and Antarctica.

''Aspidorhynchus'' was a ...

'', and the ichthyodectid

Ichthyodectiformes is an extinct order of marine stem-teleost ray-finned fish. The order is named after the genus ''Ichthyodectes'', established by Edward Drinker Cope in 1870. Ichthyodectiforms are usually considered to be some of the closest re ...

''Thrissops

''Thrissops'' (from el, θρῐ́ξ , 'hair' and el, ὄψις 'look') is an extinct genus of stem-teleost fish from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods. Its fossils are known from the Solnhofen Limestone, as well as the Kimmeridge Clay.

''T ...

''.

Classification

Initial classifications for ''Pterodactylus'' started when paleontologist Hermann von Meyer used the name Pterodactyli to contain ''Pterodactylus'' and other pterosaurs known at the time. This was emended to the

Initial classifications for ''Pterodactylus'' started when paleontologist Hermann von Meyer used the name Pterodactyli to contain ''Pterodactylus'' and other pterosaurs known at the time. This was emended to the family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

Pterodactylidae

Pterodactylidae is a controversial group of pterosaurs. During the 2000s and 2010s, several competing definitions for the various Jurassic pterodactyloid groups were proposed. Pereda-Suberbiola ''et al.'' (2012) used Fabien Knoll's (2000) defini ...

by Prince Charles Lucien Bonaparte

Charles Lucien Jules Laurent Bonaparte, 2nd Prince of Canino and Musignano (24 May 1803 – 29 July 1857), was a French naturalist and ornithologist. Lucien and his wife had twelve children, including Cardinal Lucien Bonaparte.

Life and career

...

in 1838. However, this group has more recently been given several competing definitions.

Beginning in 2014, researchers Steven Vidovic and David Martill constructed an analysis in which several pterosaurs traditionally thought of as archaeopterodactyloids closely related to the ctenochasmatoid

Ctenochasmatoidea is a group of early pterosaurs within the suborder Pterodactyloidea. Their remains are usually found in what were once coastal or lake environments. They generally had long wings, long necks, and highly specialized teeth.

Evolu ...

s may have been more closely related to the more advanced dsungaripteroids, or in some cases, fall outside both groups. Their conclusion was published in 2017, in which they placed ''Pterodactylus'' as a basal member of the suborder Pterodactyloidea.

As illustrated below, the results of a different topology

In mathematics, topology (from the Greek language, Greek words , and ) is concerned with the properties of a mathematical object, geometric object that are preserved under Continuous function, continuous Deformation theory, deformations, such ...

are based on a phylogenetic analysis made by Longrich, Martill, and Andres in 2018. Unlike the previous results above, they placed ''Pterodactylus'' within the clade Euctenochasmatia, resulting in a more derived position.

Formerly assigned species

Numerous species have been assigned to ''Pterodactylus'' in the years since its discovery. In the first half of the 19th century any new pterosaur species would be named ''Pterodactylus'', which thus became a " wastebasket taxon". Even after clearly different forms had later been given their own generic name, new species would be created from the very productive sites, throughout Europe and North America, often based on only slightly different material.

The earliest reassignments of pterosaur species to ''Pterodactylus'' started in 1825, with the description of ''Rhamphorhynchus''; fossil collector Georg Graf zu Münster alerted the German paleontologist Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring about several distinct fossil specimens, Sömmerring thought that they belonged to an ancient bird. Further fossil preparations had uncovered teeth, to which Graf zu Münster created a skull cast. He later sent the cast to Professor Georg August Goldfuss, who recognized it as a pterosaur, specifically a species of ''Pterodactylus''. At the time however, most paleontologists incorrectly consider the genus ''Ornithocephalus'' () to be the valid name for ''Pterodactylus'', and therefore the specimen found was named as ''Ornithocephalus Münsteri'', which was first mentioned by Graf zu Münster himself. Another specimen was found and described by Graf zu Münster in 1839, he assigned this specimen to a new separate species called ''Ornithocephalus longicaudus''; the

Numerous species have been assigned to ''Pterodactylus'' in the years since its discovery. In the first half of the 19th century any new pterosaur species would be named ''Pterodactylus'', which thus became a " wastebasket taxon". Even after clearly different forms had later been given their own generic name, new species would be created from the very productive sites, throughout Europe and North America, often based on only slightly different material.

The earliest reassignments of pterosaur species to ''Pterodactylus'' started in 1825, with the description of ''Rhamphorhynchus''; fossil collector Georg Graf zu Münster alerted the German paleontologist Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring about several distinct fossil specimens, Sömmerring thought that they belonged to an ancient bird. Further fossil preparations had uncovered teeth, to which Graf zu Münster created a skull cast. He later sent the cast to Professor Georg August Goldfuss, who recognized it as a pterosaur, specifically a species of ''Pterodactylus''. At the time however, most paleontologists incorrectly consider the genus ''Ornithocephalus'' () to be the valid name for ''Pterodactylus'', and therefore the specimen found was named as ''Ornithocephalus Münsteri'', which was first mentioned by Graf zu Münster himself. Another specimen was found and described by Graf zu Münster in 1839, he assigned this specimen to a new separate species called ''Ornithocephalus longicaudus''; the specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

means 'long tail', in reference to the animal's tail size. German paleontologist Hermann von Meyer in 1845 officially emended that the genus ''Pterodactylus'' had priority over ''Ornithocephalus'', so he reassigned the species ''O. münsteri'' and ''O. longicaudus'' into ''Pterodactylus münsteri'' and ''Pterodactylus longicaudus''. In 1846, von Meyer created the new species ''Pterodactylus gemmingi'' based on long-tailed remains; the specific name honors the fossil collector Carl Eming von Gemming. Later, in 1847, von Meyer finally erected the generic name ''Rhamphorhynchus'' () due to the distinctively long tails seen in the specimens found, which are much longer than those seen in ''Pterodactylus''. He assigned the species ''P. longicaudus'' as the type species of ''Rhamphorhynchus'', which resulted in a new combination called ''Rhamphorhynchus longicaudus''. The species ''R. münsteri'' was later changed to ''R. muensteri'' by Lydekker in 1888, due to the ICZN

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its publisher, the I ...

rule that prohibits non-standard Latin characters, such as ''ü'', in scientific names.

Beginning in 1846, many pterosaur specimens were found near the village of

Beginning in 1846, many pterosaur specimens were found near the village of Burham

Burham is a village and civil parish in the borough of Tonbridge and Malling in Kent, England. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 1,251, decreasing to 1,195 at the 2011 Census. The village is near the Medway towns.

The histor ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

by British paleontologists James Scott Bowerbank

James Scott Bowerbank (14 July 1797 – 8 March 1877) was a British naturalist and palaeontologist.

Biography

Bowerbank was born in Bishopsgate, London, and succeeded in conjunction with his brother to his father's distillery, in which he was ...

and Sir Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

. Bowerbank had assigned fossil remains to two new species; the first was named in 1846 as ''Pterodactylus giganteus''; the specific name means 'the gigantic one' in Latin, in reference to the large size of the remains, and the second species was named in 1851 as ''Pterodactylus cuvieri'', in honor of the French scientist Georges Cuvier. Later in 1851, Owen named and described new pterosaur specimens that have been found yet again in England. He assigned these specimens to a new species called ''Pterodactylus compressirostris''.Owen, R. (1851). Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Cretaceous Formations. ''The Palaeontographical Society'' 5(11):1–118. In 1914 however, paleontologist Reginald Hooley

Reginald Walter Hooley (5 September 1865 – 5 May 1923) was a businessman and amateur paleontologist, collecting on the Isle of Wight. He is probably best remembered for describing the dinosaur ''Iguanodon atherfieldensis'', now ''Mantellisaurus ...

redescribed ''P. compressirostris'', to which he erected the genus ''Lonchodectes

''Lonchodectes'' (meaning "lance biter") was a genus of lonchodectid pterosaur from several formations dating to the Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of England, mostly in the area around Kent. The species belonging to it had been assigned to ''Orni ...

'' (), and therefore made ''P. compressirostris'' the type species, and created the new combination ''L. compressirostris''. In a 2013 review, ''P. giganteus'' and ''P. cuvieri'' were reassigned to new genera; ''P. giganteus'' was reassigned to a genus called '' Lonchodraco'' ('lance dragon'), which resulted in a new combination called ''L. giganteus'', and ''P. cuvieri'' was reassigned to the new genus ''Cimoliopterus

''Cimoliopterus'' is a genus of pterosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous in what is now England and the United States. The first known specimen, consisting of the front part of a snout including part of a crest, was discovered in the G ...

'' ('chalk wing'), creating ''C. cuvieri''. Back in 1859, Owen had found remains the front part of a snout in the Cambridge Greensand, and assigned it into the species ''Pterodactylus segwickii''; in honor of Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did on W ...

, a British geologist. This species however, was reassigned to the genus ''Camposipterus

''Camposipterus'' is a genus of pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of England. Fossil remains of ''Camposipterus'' dated back to the Early Cretaceous, about 112 million years ago.

Discovery and naming

In 1869, Harry Govier Seel ...

'' in 2013, therefore creating the new combination ''Camposipterus segwickii''. Later, in 1861, Owen had uncovered multiple distinctively looking fossil remains yet again in the Cambridge Greensand, these were assigned to a new species named ''Pterodactylus simus'', though the British paleontologist Harry Govier Seeley had created a separate generic name called '' Ornithocheirus'', and reassigned ''P. simus'' as the type species, which created the combination ''Ornithocheirus simus''. Between the years 1869 and 1870, Seeley had reassigned many pterosaur species into ''Ornithocheirus'', while also creating several new species. Many of these species however, are now reclassified to other genera, or considered . In 1874, further specimens were found in England, again by Owen, these ones were assigned to a new species called ''Pterodactylus sagittirostris'', this species however, was reassigned to the genus ''Lonchodectes'' in 1914 by Hooley, which resulted in an ''L. sagittirostris''. This conclusion was revised by Rigal ''et al.'' in 2017, who disagreed with Hooley's reassignment, and therefore created the genus ''Serradraco

''Serradraco'' is a genus of Early Cretaceous pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Valanginian aged Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation in England. Named by Rigal ''et al.'' in 2018 with the description of a second specimen, it contains a single species, ...

'', which afterwards resulted in a new combination called ''S. sagittirostris''.

Assigning new pterosaur species to ''Pterodactylus'' was not only common in Europe, but also in North America; paleontologists such as

Assigning new pterosaur species to ''Pterodactylus'' was not only common in Europe, but also in North America; paleontologists such as Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of Paleontology in Yale College and President of the National Academy of Sciences. He was one of the preeminent scientists in the field of paleontology. Among h ...

in 1871 for example, described several toothless pterosaur specimens, which were accompanied by teeth that belonged to the fish ''Xiphactinus

''Xiphactinus'' (from Latin and Greek for " sword-ray") is an extinct genus of large (Shimada, Kenshu, and Michael J. Everhart. "Shark-bitten Xiphactinus audax (Teleostei: Ichthyodectiformes) from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of Kansas. ...

'', which Marsh assumed that these teeth belonged to the pterosaur specimens he found, since all pterosaurs discovered at the time had teeth. He then assigned these specimens to a new species called ''"Pterodactylus oweni"'', but this was changed to ''Pterodactylus occidentalis'' because ''"P. oweni"'' was found to have been preoccupied

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linn ...

by a pterosaur species described with the same name back in 1864 by Seeley. In 1872, American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist, and ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope distinguished himself as a child prodigy interested ...

also found various pterosaur specimens in North America, he assigned these to two new species known as ''Ornithochirus umbrosus'' and ''Ornithochirus harpyia'', Cope attempted to assign the specimens he found to the genus ''Ornithocheirus'', but misspelled forgetting the 'e'. In 1875 however, Cope reassigned the species ''O. umbrosus'' and ''O. harpyia'' into ''Pterodactylus umbrosus'' and ''Pterodactylus harpyia'', though these species had been considered ever since. Paleontologist Samuel Wendell Williston unearthed the first skull of the pterosaur, and found that the animal was toothless, this made Marsh create the genus ''Pteranodon

''Pteranodon'' (); from Ancient Greek (''pteron'', "wing") and (''anodon'', "toothless") is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with ''P. longiceps'' having a wingspan of . They lived during the late Cr ...

'' (lit. 'toothless wing'), and therefore reassigned all the American pterosaur species, including the ones that he named, from ''Pterodactylus'' to ''Pteranodon''.

Later, in the 1980s, subsequent revisions by Peter Wellnhofer had reduced the number of recognized species to about half a dozen. Many species assigned to ''Pterodactylus'' had been based on juvenile specimens, and subsequently been recognized as immature individuals of other species or genera. By the 1990s it was understood that this was even true for part of the remaining species. ''P. elegans'', for example, was found by numerous studies to be an immature ''Ctenochasma''. Another species of ''Pterodactylus'' originally based on small, immature specimens was ''P. micronyx''. However, it has been difficult to determine exactly of what genus and species ''P. micronyx'' might be the juvenile form. Stéphane Jouve, Christopher Bennett and others had once suggested that it probably belonged either to ''Gnathosaurus subulatus

''Gnathosaurus'' (meaning "jawed lizard") is a genus of ctenochasmatid pterosaur containing two species: ''G. subulatus'', named in 1833 from the Solnhofen Limestone of Germany, and ''G. macrurus'', known from the Purbeck Limestone of the UK. I ...

'' or one of the species belonging to ''Ctenochasma'', though after additional research Bennett assigned it to the genus ''Aurorazhdarcho''. Another species with a complex history is ''P. longicollum'', named by von Meyer in 1854, based on a large specimen with a long neck and fewer teeth. Many researchers, including David Unwin, have found ''P. longicollum'' to be distinct from ''P. kochi'' and ''P. antiquus''. Unwin found ''P. longicollum'' to be closer to ''Germanodactylus'' and therefore requiring a new genus name. It has sometimes been placed in the genus ''Diopecephalus'' because Harry Govier Seeley based this genus partly on the ''P. longicollum'' material. However, it was shown by Bennett that the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wiktionary:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to a ...

later designated for ''Diopecephalus'' was a fossil belonging to ''P. kochi'', and no longer thought to be separate from ''Pterodactylus''. ''Diopecephalus'' is therefore a synonym of ''Pterodactylus'', and as such is unavailable for use as a new genus for ''"P." longicollum''. ''"P." longicollum'' was eventually made the type species of a separate genus ''Ardeadactylus''.

Controversial species

The only well-known and well-supported species left by the first decades of the 21st century were ''P. antiquus'' and ''P. kochi''. However, most studies between 1995 and 2010 found little reason to separate even these two species, and treated them as synonymous. More recent studies of pterosaur relationships have found anurognathids and pterodactyloids to be sister groups, which would limit the more inclusive group

The only well-known and well-supported species left by the first decades of the 21st century were ''P. antiquus'' and ''P. kochi''. However, most studies between 1995 and 2010 found little reason to separate even these two species, and treated them as synonymous. More recent studies of pterosaur relationships have found anurognathids and pterodactyloids to be sister groups, which would limit the more inclusive group Caelidracones

The Caelidracones is a group of pterosaurs.

The clade Caelidracones was defined in 2003 by David Unwin as the group consisting of the last common ancestor of ''Anurognathus ammoni'' and '' Quetzalcoatlus northropi'', and all its descendants.

...

to just two clades. In 1996, Bennett suggested that the differences between specimens of ''P. kochi'' and ''P. antiquus'' could be explained by differences in age, with ''P. kochi'' (including specimens alternately classified in the species ''P. scolopaciceps'') representing an immature growth stage of ''P. antiquus''. In a 2004 paper, Jouve used a different method of analysis and recovered the same result, showing that the "distinctive" features of ''P. kochi'' were age-related, and using mathematical comparison to show that the two forms are different growth stages of the same species. An additional review of the specimens published in 2013 demonstrated that some of the supposed differences between ''P. kochi'' and ''P. antiquus'' were due to measurement errors, further supporting their synonymy.

By the 2010s, a large body of research had been developed based on the idea that ''P. kochi'' and ''P. scolopaciceps'' were early growth stages of ''P. antiquus''. However, in 2014, two scientists began publishing research that challenged this paradigm. Steven Vidovic and David Martill concluded that differences between specimens of ''P. kochi'', ''P. scolopaciceps'', and ''P. antiquus'', such as different lengths of neck vertebrae, thinner or thicker teeth, more rounded skulls, and how far the teeth extended back in the jaws, were significant enough to separate them into three distinct species. Vidovic and Martill also performed a phylogenetic analysis which treated all relevant specimens as distinct units, and found that the ''P. kochi'' type specimen did not form a natural group with that of ''P. antiquus''. They concluded that the genus ''Diopecephalus'' could be returned to use to distinguish ''"P". kochi'' from ''P. antiquus''. They named the new genus '' Aerodactylus'' for ''P. scolopaciceps'' as well. So, what Bennett considered early growth stages of one species, Vidovic and Martill considered representatives of new species.

In 2017, Bennett challenged this hypothesis, he claimed that while Vidovic and Martill had identified real differences between these three groups of specimens, they had not provided any rationale that the differences were enough to distinguish them as species, rather than just individual variation, growth changes, or simply due to crushing and distortion during the fossilization process. Bennett pointed in particular to the data used to distinguish ''Aerodactylus'', which was so different from the data for related species, it might be due to an unnatural assemblage of specimens. As a result, Bennett continued to consider ''Diopecephalus'' and ''Aerodactylus'' simply as year-classes of immature ''Pterodactylus antiquus''.

List of species

During its over-200-year history, the various species of ''Pterodactylus'' have gone through a number of changes in classification and thus have acquired a large number of synonyms. Additionally, a number of species assigned to ''Pterodactylus'' are based on poor remains that have proven difficult to assign to one species or another and are therefore considered (). The following list includes names that were used to identify new pterosaur species that now have been reclassified, or until recently thought to be pertaining to ''Pterodactylus'' proper, and names based on other material that has as yet not been assigned to other genera. This list also includes species that are ('naked names'), which are species that were not published formally. Species that are ('forgotten names') are the ones that have been disused, and species that are ('rejected names') are the ones that have been rejected because a more preferable name had been accepted instead.Cultural significance

''Pterodactylus'' is regarded as one of the most iconic prehistoric creatures, with multiple appearances in books, movies, as well as television series and several videogames. The informal name "pterodactyl" is sometimes used to refer to any kind of animal belonging to the order Pterosauria, though most of the times to ''Pterodactylus'', as it's the most well-known member of the group. The popular aspect of ''Pterodactylus'' consists of an elongated head crest, and potentially large wings. Studies of ''Pterodactylus'' however, conclude that it may even lack a bony cranial crest, though several analysis have proven that ''Pterodactylus'' may in fact have a crest made up of soft tissue instead of bone.

''Pterodactylus'' is the star character of the 2005

''Pterodactylus'' is regarded as one of the most iconic prehistoric creatures, with multiple appearances in books, movies, as well as television series and several videogames. The informal name "pterodactyl" is sometimes used to refer to any kind of animal belonging to the order Pterosauria, though most of the times to ''Pterodactylus'', as it's the most well-known member of the group. The popular aspect of ''Pterodactylus'' consists of an elongated head crest, and potentially large wings. Studies of ''Pterodactylus'' however, conclude that it may even lack a bony cranial crest, though several analysis have proven that ''Pterodactylus'' may in fact have a crest made up of soft tissue instead of bone.

''Pterodactylus'' is the star character of the 2005 horror film

Horror is a film genre that seeks to elicit fear or disgust in its audience for entertainment purposes.

Horror films often explore dark subject matter and may deal with transgressive topics or themes. Broad elements include monsters, apoca ...