Project Rover on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Project Rover was a United States project to develop a nuclear-thermal rocket that ran from 1955 to 1973 at the

Liquid hydrogen was theoretically the best possible propellant, but in the early 1950s it was expensive, and available only in small quantities. In 1952, the AEC and the

Liquid hydrogen was theoretically the best possible propellant, but in the early 1950s it was expensive, and available only in small quantities. In 1952, the AEC and the

By 1957, the Atlas missile project was proceeding well, and with smaller and lighter warheads becoming available, the need for a nuclear upper stage had all but disappeared. On 2 October 1957, the AEC proposed cutting Project Rover's budget, but the proposal was soon overtaken by events.

Two days later, the Soviet Union launched

By 1957, the Atlas missile project was proceeding well, and with smaller and lighter warheads becoming available, the need for a nuclear upper stage had all but disappeared. On 2 October 1957, the AEC proposed cutting Project Rover's budget, but the proposal was soon overtaken by events.

Two days later, the Soviet Union launched

Nuclear reactors for Project Rover were built at LASL Technical Area 18 (TA-18), also known as the Pajarito Site. Fuel and internal engine components were fabricated in the Sigma complex at Los Alamos. Testing of fuel elements and other materials science was done by the LASL N Division at TA-46 using various ovens and later a custom test reactor, the Nuclear Furnace. Staff from the LASL Test (J) and Chemical Metallurgy Baker (CMB) divisions also participated in Project Rover. Two reactors were built for each engine; one for

Nuclear reactors for Project Rover were built at LASL Technical Area 18 (TA-18), also known as the Pajarito Site. Fuel and internal engine components were fabricated in the Sigma complex at Los Alamos. Testing of fuel elements and other materials science was done by the LASL N Division at TA-46 using various ovens and later a custom test reactor, the Nuclear Furnace. Staff from the LASL Test (J) and Chemical Metallurgy Baker (CMB) divisions also participated in Project Rover. Two reactors were built for each engine; one for  When that ended, the workers had to come to grips with the difficulties of dealing with hydrogen, which could leak through microscopic holes too small to permit the passage of other fluids. On 7 November 1961, a minor accident caused a violent hydrogen release. The complex finally became operational in 1964. SNPO envisaged the construction of a 20,000 MW nuclear rocket engine, so construction supervisor, Keith Boyer had the

When that ended, the workers had to come to grips with the difficulties of dealing with hydrogen, which could leak through microscopic holes too small to permit the passage of other fluids. On 7 November 1961, a minor accident caused a violent hydrogen release. The complex finally became operational in 1964. SNPO envisaged the construction of a 20,000 MW nuclear rocket engine, so construction supervisor, Keith Boyer had the

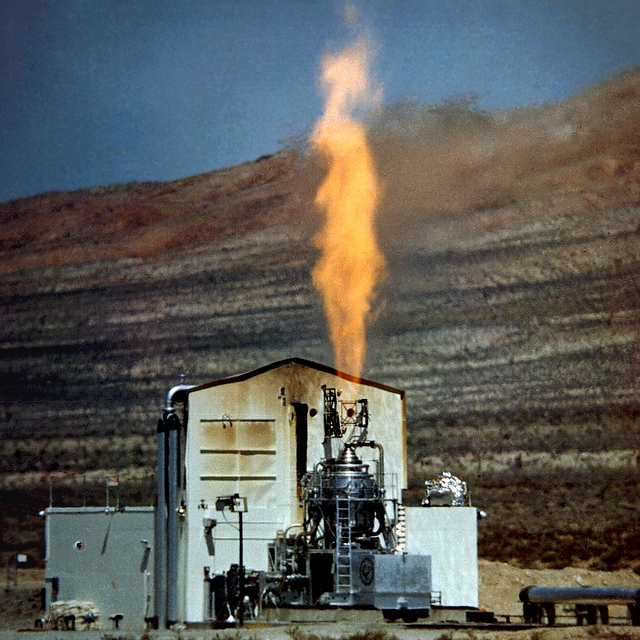

The first test of the Kiwi A, the first model of the Kiwi rocket engine, was conducted at Jackass Flats on 1 July 1959. Kiwi A had a cylindrical core high and in diameter. A central island contained heavy water that acted both as a coolant and as a moderator to reduce the amount of uranium oxide required. The control rods were located inside the island, which was surrounded by 960 graphite fuel plates loaded with uranium oxide fuel particles and a layer of 240 graphite plates. The core was surrounded by of graphite wool moderator and encased in an aluminum shell. Gaseous hydrogen was used as a propellant, at a flow rate of . Intended to produce 100 MW, the engine ran at 70 MW for 5 minutes. The core temperature was much higher than expected, up to , due to cracking of the graphite plates, which was enough to cause some of the fuel to melt.

A series of improvements were made for the next test on 8 July 1960 to create an engine known as Kiwi A Prime. The fuel elements were extruded into cylinders and coated with

The first test of the Kiwi A, the first model of the Kiwi rocket engine, was conducted at Jackass Flats on 1 July 1959. Kiwi A had a cylindrical core high and in diameter. A central island contained heavy water that acted both as a coolant and as a moderator to reduce the amount of uranium oxide required. The control rods were located inside the island, which was surrounded by 960 graphite fuel plates loaded with uranium oxide fuel particles and a layer of 240 graphite plates. The core was surrounded by of graphite wool moderator and encased in an aluminum shell. Gaseous hydrogen was used as a propellant, at a flow rate of . Intended to produce 100 MW, the engine ran at 70 MW for 5 minutes. The core temperature was much higher than expected, up to , due to cracking of the graphite plates, which was enough to cause some of the fuel to melt.

A series of improvements were made for the next test on 8 July 1960 to create an engine known as Kiwi A Prime. The fuel elements were extruded into cylinders and coated with

LASL's original objective had been a 10,000 MW nuclear rocket engine capable of launching into a orbit. This engine was codenamed Condor, after the large flying birds, in contrast to the small flightless Kiwi. However, in October 1958, NASA had studied putting a nuclear upper stage on a

LASL's original objective had been a 10,000 MW nuclear rocket engine capable of launching into a orbit. This engine was codenamed Condor, after the large flying birds, in contrast to the small flightless Kiwi. However, in October 1958, NASA had studied putting a nuclear upper stage on a  Kennedy visited Los Alamos on 7 December 1962 for a briefing on Project Rover. It was the first time a US president had visited a nuclear weapons laboratory. He brought with him a large entourage that included

Kennedy visited Los Alamos on 7 December 1962 for a briefing on Project Rover. It was the first time a US president had visited a nuclear weapons laboratory. He brought with him a large entourage that included

The next step in LASL's research program was to build a larger reactor. The size of the core determines how much hydrogen, which is necessary for cooling, can be pushed through it; and how much uranium fuel can be loaded into it. In 1960, LASL began planning a 4,000 MW reactor with an core as a successor to Kiwi. LASL decided to name it Phoebe, after the Greek Moon goddess. Another nuclear weapon project already had that name, though, so it was changed to Phoebus, an alternative name for Apollo. Phoebus ran into opposition from SNPO, which wanted a 20,000 MW reactor. LASL thought that the difficulties of building and testing such a large reactor were being taken too lightly; just to build the 4,000 MW design required a new nozzle and improved turbopump from Rocketdyne. A prolonged bureaucratic conflict ensued.

In March 1963, SNPO and the

The next step in LASL's research program was to build a larger reactor. The size of the core determines how much hydrogen, which is necessary for cooling, can be pushed through it; and how much uranium fuel can be loaded into it. In 1960, LASL began planning a 4,000 MW reactor with an core as a successor to Kiwi. LASL decided to name it Phoebe, after the Greek Moon goddess. Another nuclear weapon project already had that name, though, so it was changed to Phoebus, an alternative name for Apollo. Phoebus ran into opposition from SNPO, which wanted a 20,000 MW reactor. LASL thought that the difficulties of building and testing such a large reactor were being taken too lightly; just to build the 4,000 MW design required a new nozzle and improved turbopump from Rocketdyne. A prolonged bureaucratic conflict ensued.

In March 1963, SNPO and the  Phoebus 1A was tested on 25 June 1965, and run at full power (1,090 MW) for ten and a half minutes. Unfortunately, the intense radiation environment caused one of the capacitance gauges to produce erroneous readings. When confronted by one gauge that said that the hydrogen propellant tank was nearly empty, and another that said that it was quarter full, and unsure which was correct, the technicians in the control room chose to believe the one that said it was quarter full. This was the wrong choice; the tank was indeed nearly empty, and the propellant ran dry. Without liquid hydrogen to cool it, the engine, operating at , quickly overheated and exploded. About a fifth of the fuel was ejected; most of the rest melted.

The test area was left for six weeks to give highly radioactive fission products time to decay. A

Phoebus 1A was tested on 25 June 1965, and run at full power (1,090 MW) for ten and a half minutes. Unfortunately, the intense radiation environment caused one of the capacitance gauges to produce erroneous readings. When confronted by one gauge that said that the hydrogen propellant tank was nearly empty, and another that said that it was quarter full, and unsure which was correct, the technicians in the control room chose to believe the one that said it was quarter full. This was the wrong choice; the tank was indeed nearly empty, and the propellant ran dry. Without liquid hydrogen to cool it, the engine, operating at , quickly overheated and exploded. About a fifth of the fuel was ejected; most of the rest melted.

The test area was left for six weeks to give highly radioactive fission products time to decay. A

The Nuclear Furnace was a small reactor only a tenth of the size of Pewee that was intended to provide an inexpensive means of conducting tests. Originally it was to be used at Los Alamos, but the cost of creating a suitable test site was greater than that of using Test Cell C. It had a tiny core long and in diameter that held 49 hexagonal fuel elements. Of these, 47 were uranium carbide-zirconium carbide "composite" fuel cells and two contained a seven-element cluster of single-hole pure uranium-zirconium carbide fuel cells. Neither type had previously been tested in a nuclear rocket propulsion reactor. In all, this was about 5 kg of highly enriched (93%) uranium-235. To achieve criticality with so little fuel, the beryllium reflector was over thick. Each fuel cell had its own cooling and moderating water jacket. Gaseous hydrogen was used instead of liquid to save money. A

The Nuclear Furnace was a small reactor only a tenth of the size of Pewee that was intended to provide an inexpensive means of conducting tests. Originally it was to be used at Los Alamos, but the cost of creating a suitable test site was greater than that of using Test Cell C. It had a tiny core long and in diameter that held 49 hexagonal fuel elements. Of these, 47 were uranium carbide-zirconium carbide "composite" fuel cells and two contained a seven-element cluster of single-hole pure uranium-zirconium carbide fuel cells. Neither type had previously been tested in a nuclear rocket propulsion reactor. In all, this was about 5 kg of highly enriched (93%) uranium-235. To achieve criticality with so little fuel, the beryllium reflector was over thick. Each fuel cell had its own cooling and moderating water jacket. Gaseous hydrogen was used instead of liquid to save money. A

LASL started by immersing fuel elements in water. It then went on to conduct a simulated water entry test (SWET) during which a piston was used to force water into a reactor as fast as possible. To simulate an impact, a mock reactor was dropped onto concrete from a height of . It bounced in the air; the pressure vessel was dented and many fuel elements were cracked but calculations showed that it would neither go critical nor explode. However, RIFT involved NERVA sitting atop a Saturn V rocket high. To find out what would happen if the booster exploded on the launch pad, a mock reactor was slammed into a concrete wall using a

LASL started by immersing fuel elements in water. It then went on to conduct a simulated water entry test (SWET) during which a piston was used to force water into a reactor as fast as possible. To simulate an impact, a mock reactor was dropped onto concrete from a height of . It bounced in the air; the pressure vessel was dented and many fuel elements were cracked but calculations showed that it would neither go critical nor explode. However, RIFT involved NERVA sitting atop a Saturn V rocket high. To find out what would happen if the booster exploded on the launch pad, a mock reactor was slammed into a concrete wall using a  The explosion was relatively small, estimated as being the equivalent of of

The explosion was relatively small, estimated as being the equivalent of of

NERVA had many potential missions. NASA considered using

NERVA had many potential missions. NASA considered using

Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, in ...

(LASL). It began as a United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

project to develop a nuclear-powered upper stage

A multistage rocket or step rocket is a launch vehicle that uses two or more rocket ''stages'', each of which contains its own engines and propellant. A ''tandem'' or ''serial'' stage is mounted on top of another stage; a ''parallel'' stage is ...

for an intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

(ICBM). The project was transferred to NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

in 1958 after the Sputnik crisis

The Sputnik crisis was a period of public fear and anxiety in Western nations about the perceived technological gap between the United States and Soviet Union caused by the Soviets' launch of ''Sputnik 1'', the world's first artificial satelli ...

triggered the Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the tw ...

. It was managed by the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office The United States Space Nuclear Propulsion Office (SNPO) was created in 1961 in response to NASA Marshall Space Flight Center's desire to explore the use of nuclear thermal rockets created by Project Rover in NASA space exploration activities. B ...

(SNPO), a joint agency of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), and NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

. Project Rover became part of NASA's Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application (NERVA

Nerva (; originally Marcus Cocceius Nerva; 8 November 30 – 27 January 98) was Roman emperor from 96 to 98. Nerva became emperor when aged almost 66, after a lifetime of imperial service under Nero and the succeeding rulers of the Flavian dy ...

) project and henceforth dealt with the research into nuclear rocket reactor design, while NERVA involved the overall development and deployment of nuclear rocket engines, and the planning for space missions.

Nuclear reactors for Project Rover were built at LASL Technical Area 18 (TA-18), also known as the Pajarito Canyon Site. They were tested there at very low power and then shipped to Area 25 (known as Jackass Flats) at the AEC's Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of th ...

. Testing of fuel elements and other materials science was done by the LASL N-Division at TA-46 using various ovens and later a custom test reactor, the Nuclear Furnace. Project Rover resulted in the development of three reactor types: Kiwi (1955 to 1964), Phoebus (1964 to 1969), and Pewee (1969 to 1972). Kiwi and Phoebus were large reactors, while Pewee was much smaller, conforming to the smaller budget available after 1968.

The reactors were fueled by highly enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238U ...

, with liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen (LH2 or LH2) is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecular H2 form.

To exist as a liquid, H2 must be cooled below its critical point of 33 K. However, for it to be in a fully li ...

used as both a rocket propellant and reactor coolant. Nuclear graphite

Nuclear graphite is any grade of graphite, usually synthetic graphite, manufactured for use as a moderator or reflector within a nuclear reactor. Graphite is an important material for the construction of both historical and modern nuclear reacto ...

and beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element with the symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with other elements to form mi ...

were used as neutron moderator

In nuclear engineering, a neutron moderator is a medium that reduces the speed of fast neutrons, ideally without capturing any, leaving them as thermal neutrons with only minimal (thermal) kinetic energy. These thermal neutrons are immensely mo ...

s and neutron reflector

A neutron reflector is any material that reflects neutrons. This refers to elastic scattering rather than to a specular reflection. The material may be graphite, beryllium, steel, tungsten carbide, gold, or other materials. A neutron reflector ...

s. The engines were controlled by drums with graphite or beryllium on one side and boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the ''boron group'' it has th ...

(a nuclear poison

In applications such as nuclear reactors, a neutron poison (also called a neutron absorber or a nuclear poison) is a substance with a large neutron absorption cross-section. In such applications, absorbing neutrons is normally an undesirable eff ...

) on the other, and the energy level adjusted by rotating the drums. Because hydrogen also acts as a moderator, increasing the flow of propellant also increased reactor power without the need to adjust the drums. Project Rover tests demonstrated that nuclear rocket engines could be shut down and restarted many times without difficulty, and could be clustered if more thrust was desired. Their specific impulse

Specific impulse (usually abbreviated ) is a measure of how efficiently a reaction mass engine (a rocket using propellant or a jet engine using fuel) creates thrust. For engines whose reaction mass is only the fuel they carry, specific impulse i ...

(efficiency) was roughly double that of chemical rockets.

The nuclear rocket enjoyed strong political support from the influential chairman of the United States Congress Joint Committee on Atomic Energy The Joint Committee on Atomic Energy (JCAE) was a United States congressional committee that was tasked with exclusive jurisdiction over "all bills, resolutions, and other matters" related to civilian and military aspects of nuclear power from 1946 ...

, Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

Clinton P. Anderson

Clinton Presba Anderson (October 23, 1895 – November 11, 1975) was an American politician who represented New Mexico in the United States Senate from 1949 until 1973. A member of the United States Democratic Party, Democratic Party, he pr ...

from New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

(where LASL was located), and his allies, Senators Howard Cannon

Howard Walter Cannon (January 26, 1912 – March 5, 2002) was an American politician from Nevada. Elected to the first of four consecutive terms in 1958, he served in the United States Senate from 1959 to 1983. He was a member of the Democratic ...

from Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

and Margaret Chase Smith

Margaret Madeline Smith (née Chase; December 14, 1897 – May 29, 1995) was an American politician. A member of the Republican Party, she served as a U.S. representative (1940–1949) and a U.S. senator (1949–1973) from Maine. She was the firs ...

from Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

. This enabled it to survive multiple cancellation attempts that became ever more serious in the cost cutting that prevailed as the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

escalated and after the space race ended with the Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, an ...

Moon landing. Projects Rover and NERVA were canceled over their objection in January 1973, and none of the reactors ever flew.

Beginnings

Early concepts

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, some scientists at the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

's Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

, including Stan Ulam

Stanisław Marcin Ulam (; 13 April 1909 – 13 May 1984) was a Polish-American scientist in the fields of mathematics and nuclear physics. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapon ...

, Frederick Reines

Frederick Reines ( ; March 16, 1918 – August 26, 1998) was an American physicist. He was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize in Physics for his co-detection of the neutrino with Clyde Cowan in the neutrino experiment. He may be the only scientist in ...

and Frederic de Hoffmann Frederic de Hoffmann (July 8, 1924 in Vienna, Austria – October 4, 1989 in La Jolla) was a nuclear physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project. He came to the United States of America in 1941 and graduated from Harvard University in 1945 (he als ...

, speculated about the development of nuclear-powered rockets, and in 1947, Ulam and Cornelius Joseph "C. J." Everett wrote a paper in which they considered using atomic bombs as a means of rocket propulsion. This became the basis for Project Orion. In December 1945, Theodore von Karman

Theodore may refer to:

Places

* Theodore, Alabama, United States

* Theodore, Australian Capital Territory

* Theodore, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Banana, Australia

* Theodore, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Theodore Reservoir, a lake in Saskatche ...

and Hsue-Shen Tsien

Qian Xuesen, or Hsue-Shen Tsien (; 11 December 1911 – 31 October 2009), was a Chinese mathematician, cyberneticist, aerospace engineer, and physicist who made significant contributions to the field of aerodynamics and established engineering ...

wrote a report for the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

. While they agreed that it was not yet practical, Tsien speculated that nuclear-powered rockets might one day be powerful enough to launch satellites into orbit.

In 1947, North American Aviation's Aerophysics Laboratory published a large paper surveying many of the problems involved in using nuclear reactors to power airplanes and rockets. The study was specifically aimed at an aircraft with a range of and a payload of , and covered turbopump

A turbopump is a propellant pump with two main components: a rotodynamic pump and a driving gas turbine, usually both mounted on the same shaft, or sometimes geared together. They were initially developed in Germany in the early 1940s. The purpos ...

s, structure, tankage, aerodynamics

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dyn ...

and nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nu ...

design. They concluded that hydrogen was best as a propellant and that graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on large ...

would be the best neutron moderator

In nuclear engineering, a neutron moderator is a medium that reduces the speed of fast neutrons, ideally without capturing any, leaving them as thermal neutrons with only minimal (thermal) kinetic energy. These thermal neutrons are immensely mo ...

, but assumed an operating temperature

An operating temperature is the allowable temperature range of the local ambient environment at which an electrical or mechanical device operates. The device will operate effectively within a specified temperature range which varies based on the de ...

of , which was beyond the capabilities of available materials. The conclusion was that nuclear-powered rockets were not yet practical.

The public revelation of atomic energy Atomic energy or energy of atoms is energy carried by atoms. The term originated in 1903 when Ernest Rutherford began to speak of the possibility of atomic energy.Isaac Asimov, ''Atom: Journey Across the Sub-Atomic Cosmos'', New York:1992 Plume, ...

at the end of the war generated a great deal of speculation, and in the United Kingdom, Val Cleaver, the chief engineer of the rocket division at De Havilland

The de Havilland Aircraft Company Limited () was a British aviation manufacturer established in late 1920 by Geoffrey de Havilland at Stag Lane Aerodrome Edgware on the outskirts of north London. Operations were later moved to Hatfield in H ...

, and Leslie Shepard, a nuclear physicist

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, independently considered the problem of nuclear rocket propulsion. They became collaborators, and in a series of papers published in the ''Journal of the British Interplanetary Society

The ''Journal of the British Interplanetary Society'' (''JBIS'') is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal that was established in 1934. The journal covers research on astronautics and space science and technology, including spacecraft design, ...

'' in 1948 and 1949, they outlined the design of a nuclear-powered rocket with a solid-core graphite heat exchanger

A heat exchanger is a system used to transfer heat between a source and a working fluid. Heat exchangers are used in both cooling and heating processes. The fluids may be separated by a solid wall to prevent mixing or they may be in direct contac ...

. They reluctantly concluded that nuclear rockets were essential for deep space exploration, but not yet technically feasible.

Bussard report

In 1953,Robert W. Bussard

Robert W. Bussard (August 11, 1928 – October 6, 2007) was an American physicist who worked primarily in nuclear fusion energy research. He was the recipient of the Schreiber-Spence Achievement Award for STAIF-2004. He was also a fellow of th ...

, a physicist working on the Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft (NEPA) project at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) is a U.S. multiprogram science and technology national laboratory sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and administered, managed, and operated by UT–Battelle as a federally funded research and ...

, wrote a detailed study. He had read Cleaver and Shepard's work, that of Tsien, and a February 1952 report by engineers at Consolidated Vultee

Convair, previously Consolidated Vultee, was an American aircraft manufacturing company that later expanded into rockets and spacecraft. The company was formed in 1943 by the merger of Consolidated Aircraft and Vultee Aircraft. In 1953, it ...

. He used data and analyses from existing chemical rockets, along with specifications for existing components. His calculations were based on the state of the art of nuclear reactors. Most importantly, the paper surveyed several ranges and payload sizes; Consolidated's pessimistic conclusions had partly been the result of considering only a narrow range of possibilities.

The result, ''Nuclear Energy for Rocket Propulsion'', stated that the use of nuclear propulsion in rockets is not limited by considerations of combustion energy and thus low molecular weight propellants such as pure hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

may be used. While a conventional engine could produce an exhaust velocity of , a hydrogen-fueled nuclear engine could attain an exhaust velocity of under the same conditions. He proposed a graphite-moderated reactor due to graphite's ability to withstand high temperatures and concluded that the fuel elements would require protective cladding to withstand corrosion by the hydrogen propellant.

Bussard's study had little impact at first, mainly because only 29 copies were printed, and it was classified as Restricted Data

Restricted Data (RD) is a category of proscribed information, per National Industrial Security Program Operating Manual (NISPOM). Specifically, it is defined by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 as:

:''all data concerning (1) design, manufacture, or u ...

and therefore could only be read by someone with the required security clearance. In December 1953, it was published in Oak Ridge's ''Journal of Reactor Science and Technology''. While still classified, this gave it a wider circulation. Darol Froman

Darol Kenneth Froman (October 23, 1906 – September 11, 1997) was the Deputy Director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory from 1951 to 1962. He served as a group leader from 1943 to 1945, and a division head from 1945 to 1948. He was the sci ...

, the Deputy Director of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, in ...

(LASL), and Herbert York

Herbert Frank York (24 November 1921 – 19 May 2009) was an American nuclear physicist of Mohawk origin.http://www.edge.org/conversation/nsa-the-decision-problem. The Decision Problem He held numerous research and administrative positions a ...

, the director of the University of California Radiation Laboratory at Livermore, were interested, and established committees to investigate nuclear rocket propulsion. Froman brought Bussard out to Los Alamos to assist for one week per month.

Approval

Robert Bussard's study also attracted the attention ofJohn von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

, and he formed an ''ad hoc'' committee on Nuclear Propulsion of Missiles. Mark Mills, the assistant director at Livermore was its chairman, and its other members were Norris Bradbury

Norris Edwin Bradbury (May 30, 1909 – August 20, 1997), was an American physicist who served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years from 1945 to 1970. He succeeded Robert Oppenheimer, who personally chose Bradbury ...

from LASL; Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care fo ...

and Herbert York from Livermore; Abe Silverstein

Abraham "Abe" Silverstein

NASA.gov. Retrieved September 17, 2009. (September 15, 1908June 1, 2001) was an American engine ...

, the associate director of the NASA.gov. Retrieved September 17, 2009. (September 15, 1908June 1, 2001) was an American engine ...

National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a United States federal agency founded on March 3, 1915, to undertake, promote, and institutionalize aeronautical research. On October 1, 1958, the agency was dissolved and its assets ...

(NACA) Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory

NASA John H. Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field is a NASA center within the cities of Brook Park and Cleveland between Cleveland Hopkins International Airport and the Rocky River Reservation of Cleveland Metroparks, with a subsidiary facilit ...

; and Allen F. Donovan from Ramo-Wooldridge.

After hearing input on various designs, the Mills committee recommended that development proceed, with the aim of producing a nuclear upper stage for an intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

(ICBM). York created a new division at Livermore, and Bradbury created a new one called N Division at Los Alamos under the leadership of Raemer Schreiber

Raemer Edgar Schreiber (November 11, 1910 – December 24, 1998) was an American physicist from McMinnville, Oregon who served Los Alamos National Laboratory during World War II, participating in the development of the atomic bomb. He saw the fi ...

, to pursue it. In March 1956, the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project

The Armed Forces Special Weapons Project (AFSWP) was a United States military agency responsible for those aspects of nuclear weapons remaining under military control after the Manhattan Project was succeeded by the Atomic Energy Commission on ...

(AFSWP) recommended allocating $100 million ($ million in ) to the nuclear rocket engine project over three years for the two laboratories to conduct feasibility studies and construction of test facilities.

Eger V. Murphree and Herbert Loper at the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) were more cautious. The Atlas missile

The SM-65 Atlas was the first operational intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) developed by the United States and the first member of the Atlas rocket family. It was built for the U.S. Air Force by the Convair Division of General Dyna ...

program was proceeding well, and if successful would have sufficient range to hit targets in most of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. At the same time, nuclear warheads were becoming smaller, lighter and more powerful. The case for a new technology that promised heavier payloads over longer distances seemed weak. However, the nuclear rocket had acquired a powerful political patron in Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

Clinton P. Anderson

Clinton Presba Anderson (October 23, 1895 – November 11, 1975) was an American politician who represented New Mexico in the United States Senate from 1949 until 1973. A member of the United States Democratic Party, Democratic Party, he pr ...

from New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

(where LASL was located), the deputy chairman of the United States Congress Joint Committee on Atomic Energy The Joint Committee on Atomic Energy (JCAE) was a United States congressional committee that was tasked with exclusive jurisdiction over "all bills, resolutions, and other matters" related to civilian and military aspects of nuclear power from 1946 ...

(JCAE), who was close to von Neumann, Bradbury and Ulam. He managed to secure funding.

All work on the nuclear rocket was consolidated at Los Alamos, where it was given the codename Project Rover; Livermore was assigned responsibility for development of the nuclear ramjet

A ramjet, or athodyd (aero thermodynamic duct), is a form of airbreathing jet engine that uses the forward motion of the engine to produce thrust. Since it produces no thrust when stationary (no ram air) ramjet-powered vehicles require an ass ...

, which was codenamed Project Pluto

Project Pluto was a United States government program to develop nuclear-powered ramjet engines for use in cruise missiles. Two experimental engines were tested at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) in 1961 and 1964 respectively.

On 1 January 1957, th ...

. Project Rover was directed by an active duty

Active duty, in contrast to reserve duty, is a full-time occupation as part of a military force. In the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth of Nations, the equivalent term is active service.

India

The Indian Armed Forces are considered to be one ...

USAF officer on secondment

Secondment is the assignment of a member of one organisation to another organisation for a temporary period.

Job rotation

The employee typically retains their salary and other employment rights from their primary organization but they work close ...

to the AEC, Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

Harold R. Schmidt. He was answerable to another seconded USAF officer, Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Jack L. Armstrong, who was also in charge of Pluto and the Systems for Nuclear Auxiliary Power

The Systems Nuclear Auxiliary POWER (SNAP) program was a program of experimental radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) and space nuclear reactors flown during the 1960s by NASA.

Odd-numbered SNAPs: radioisotope thermoelectric generators ...

(SNAP) projects.

Design concepts

In principle, the design of anuclear thermal rocket

A nuclear thermal rocket (NTR) is a type of thermal rocket where the heat from a nuclear reaction, often nuclear fission, replaces the chemical energy of the propellants in a chemical rocket. In an NTR, a working fluid, usually liquid hydro ...

engine is quite simple: a turbopump would force hydrogen through a nuclear reactor, where it would be heated by the reactor to very high temperatures and then exhausted through a rocket nozzle

A rocket engine nozzle is a propelling nozzle (usually of the de Laval type) used in a rocket engine to expand and accelerate combustion products to high supersonic velocities.

Simply: propellants pressurized by either pumps or high pressure u ...

to produce thrust. Complicating factors were immediately apparent. The first was that a means had to be found of controlling reactor temperature and power output. The second was that a means had to be devised to hold the propellant. The only practical way to store hydrogen was in liquid form, and this required a temperature below . The third was that the hydrogen would be heated to a temperature of around , and materials would be required that could withstand such temperatures and resist corrosion by hydrogen.

Liquid hydrogen was theoretically the best possible propellant, but in the early 1950s it was expensive, and available only in small quantities. In 1952, the AEC and the

Liquid hydrogen was theoretically the best possible propellant, but in the early 1950s it was expensive, and available only in small quantities. In 1952, the AEC and the National Bureau of Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sci ...

had opened a plant near Boulder, Colorado

Boulder is a home rule city that is the county seat and most populous municipality of Boulder County, Colorado, United States. The city population was 108,250 at the 2020 United States census, making it the 12th most populous city in Color ...

, to produce liquid hydrogen for the thermonuclear weapons

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

program. Before settling on liquid hydrogen, LASL considered other propellants such as methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on Eart ...

() and ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

(). Ammonia, used in the tests conducted from 1955 to 1957, was inexpensive, easy to obtain, liquid at , and easy to pump and handle. It was, however, much heavier than liquid hydrogen, reducing the engine's impulse

Impulse or Impulsive may refer to:

Science

* Impulse (physics), in mechanics, the change of momentum of an object; the integral of a force with respect to time

* Impulse noise (disambiguation)

* Specific impulse, the change in momentum per uni ...

; it was also found to be even more corrosive, and had undesirable neutronic properties.

For the fuel, they considered plutonium-239

Plutonium-239 (239Pu or Pu-239) is an isotope of plutonium. Plutonium-239 is the primary fissile isotope used for the production of nuclear weapons, although uranium-235 is also used for that purpose. Plutonium-239 is also one of the three main ...

, uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exis ...

and uranium-233

Uranium-233 (233U or U-233) is a fissile Isotopes of uranium, isotope of uranium that is bred from thorium-232 as part of the thorium fuel cycle. Uranium-233 was investigated for use in nuclear weapons and as a Nuclear fuel, reactor fuel. It ha ...

. Plutonium was rejected because while it forms compounds easily, they could not reach temperatures as high as those of uranium. Uranium-233 was seriously considered, as compared to uranium-235 it is slightly lighter, has a higher number of neutrons per fission event, and a high probability of fission. It therefore held the prospect of saving some weight in fuel, but its radioactive properties make it more difficult to handle, and in any case it was not readily available. Highly enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238U ...

was therefore chosen.

For structural materials in the reactor, the choice came down to graphite or metals. Of the metals, tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isolat ...

emerged as the frontrunner, but it was expensive, hard to fabricate, and had undesirable neutronic properties. To get around its neutronic properties, it was proposed to use tungsten-184, which does not absorb neutrons. Graphite was chosen as it is cheap, gets stronger at temperatures up to , and sublimes rather than melts at .

To control the reactor, the core was surrounded by control drums coated with graphite or beryllium

Beryllium is a chemical element with the symbol Be and atomic number 4. It is a steel-gray, strong, lightweight and brittle alkaline earth metal. It is a divalent element that occurs naturally only in combination with other elements to form mi ...

(a neutron moderator) on one side and boron

Boron is a chemical element with the symbol B and atomic number 5. In its crystalline form it is a brittle, dark, lustrous metalloid; in its amorphous form it is a brown powder. As the lightest element of the ''boron group'' it has th ...

(a neutron poison

In applications such as nuclear reactors, a neutron poison (also called a neutron absorber or a nuclear poison) is a substance with a large neutron absorption cross-section. In such applications, absorbing neutrons is normally an undesirable eff ...

) on the other. The reactor's power output could be controlled by rotating the drums. To increase thrust, it is sufficient to increase the flow of propellant. Hydrogen, whether in pure form or in a compound like ammonia, is an efficient nuclear moderator, and increasing the flow also increases the rate of reactions in the core. This increased reaction rate offsets the cooling provided by the hydrogen. As the hydrogen heats up, it expands, so there is less in the core to remove heat, and the temperature will level off. These opposing effects stabilize the reactivity and a nuclear rocket engine is therefore naturally very stable, and the thrust is easily controlled by varying the hydrogen flow without changing the control drums.

LASL produced a series of design concepts, each with its own codename: Uncle Tom, Uncle Tung, Bloodhound and Shish. By 1955, it had settled on a 1,500 megawatt

The watt (symbol: W) is the unit of Power (physics), power or radiant flux in the International System of Units, International System of Units (SI), equal to 1 joule per second or 1 kg⋅m2⋅s−3. It is used to quantification (science), ...

(MW) design called Old Black Joe. In 1956, this became the basis of a 2,700 MW design intended to be the upper stage of an ICBM.

Transfer to NASA

By 1957, the Atlas missile project was proceeding well, and with smaller and lighter warheads becoming available, the need for a nuclear upper stage had all but disappeared. On 2 October 1957, the AEC proposed cutting Project Rover's budget, but the proposal was soon overtaken by events.

Two days later, the Soviet Union launched

By 1957, the Atlas missile project was proceeding well, and with smaller and lighter warheads becoming available, the need for a nuclear upper stage had all but disappeared. On 2 October 1957, the AEC proposed cutting Project Rover's budget, but the proposal was soon overtaken by events.

Two days later, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

, the first artificial satellite. This fired fears and imaginations around the world and demonstrated that the Soviet Union had the capability to deliver nuclear weapons over intercontinental distances, and undermined American notions of military, economic and technological superiority. This precipitated the Sputnik crisis

The Sputnik crisis was a period of public fear and anxiety in Western nations about the perceived technological gap between the United States and Soviet Union caused by the Soviets' launch of ''Sputnik 1'', the world's first artificial satelli ...

, and triggered the Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the tw ...

, a new area of competition in the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. Anderson wanted to give responsibility for the US space program to the AEC, but US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

responded by creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding th ...

(NASA), which absorbed NACA.

Donald A. Quarles

Donald Aubrey Quarles (July 30, 1894 – May 8, 1959) was a Telecommunications engineering, communications engineer, senior level executive with Bell Telephone Laboratories and Western Electric, and a top official in the United States Department ...

, the Deputy Secretary of Defense

The deputy secretary of defense (acronym: DepSecDef) is a statutory office () and the second-highest-ranking official in the Department of Defense of the United States of America.

The deputy secretary is the principal civilian deputy to the se ...

, met with T. Keith Glennan

Thomas Keith Glennan (September 8, 1905 – April 11, 1995) was the first Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, serving from August 19, 1958 to January 20, 1961.

Early career

Born in Enderlin, North Dakota, the so ...

, the new administrator of NASA, and Hugh Dryden

Hugh Latimer Dryden (July 2, 1898 – December 2, 1965) was an American Aeronautics, aeronautical scientist and civil servant. He served as NASA Deputy Administrator from August 19, 1958, until his death.

Biography Early life and education

Dryden ...

, his deputy on 20 August 1958, the day after they were sworn into office at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

, and Rover was the first item on the agenda. Quarles was eager to transfer Rover to NASA, as the project no longer had a military purpose. Silverstein, whom Glennan had brought to Washington, D.C., to organize NASA's spaceflight program, had long had an interest in nuclear rocket technology. He was the first senior NACA official to show interest in rocket research, had initiated investigation into the use of hydrogen as a rocket propellant, was involved in the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion

The Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) program and the preceding Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft (NEPA) project worked to develop a nuclear propulsion system for aircraft. The United States Army Air Forces initiated Project NEPA on ...

(ANP) project, built NASA's Plum Brook Reactor

The Plum Brook Reactor was a NASA 60 megawatt water-cooled and moderated research nuclear reactor, located in Sandusky, Ohio, 50 mi west of the NASA Glenn Research Center (at that time the NASA Lewis Research Center) in Cleveland, of which i ...

, and had created a nuclear rocket propulsion group at Lewis under Harold Finger.

Responsibility for the non-nuclear components of Project Rover was officially transferred from the United States Air Force (USAF) to NASA on 1 October 1958, the day NASA officially became operational and assumed responsibility for the US civilian space program. Project Rover became a joint NASA-AEC project. Silverstein appointed Finger from Lewis to oversee the nuclear rocket development. On 29 August 1960, NASA created the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office The United States Space Nuclear Propulsion Office (SNPO) was created in 1961 in response to NASA Marshall Space Flight Center's desire to explore the use of nuclear thermal rockets created by Project Rover in NASA space exploration activities. B ...

(SNPO) to oversee the nuclear rocket project. Finger was appointed as its manager, with Milton Klein from AEC as his deputy.

A formal "Agreement Between NASA and AEC on Management of Nuclear Rocket Engine Contracts" was signed by NASA Deputy Administrator Robert Seamans

Robert Channing Seamans Jr. (October 30, 1918 – June 28, 2008) was an MIT professor who served as NASA Deputy Administrator and 9th United States Secretary of the Air Force.

Birth and education

He was born in Salem, Massachusetts, to Pauline ...

and AEC General Manager Alvin Luedecke

Alvin Roubal Luedecke (10 October 1910 – 9 August 1998) was a United States Army Air Forces general during World War II. He commanded the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project after the war. After retiring from the Air Force in 1958, he was Gene ...

on 1 February 1961. This was followed by an "Inter-Agency Agreement on the Program for the Development of Space Nuclear Rocket Propulsion (Project Rover)", which they signed on 28 July 1961. SNPO also assumed responsibility for SNAP, with Armstrong becoming assistant to the director of the Reactor Development Division at AEC, and Lieutenant Colonel G. M. Anderson, formerly the SNAP project officer in the disbanded Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion Office (ANPO), became chief of the SNAP Branch in the new division.

On 25 May 1961, President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

addressed a joint session of Congress

A joint session of the United States Congress is a gathering of members of the two chambers of the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States: the Senate and the House of Representatives. Joint sessions can be held on a ...

. "First," he announced, "I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth." He then went on to say: "Secondly, an additional 23 million dollars, together with 7 million dollars already available, will accelerate development of the Rover nuclear rocket. This gives promise of someday providing a means for even more exciting and ambitious exploration of space, perhaps beyond the Moon, perhaps to the very end of the Solar System itself."

Test site

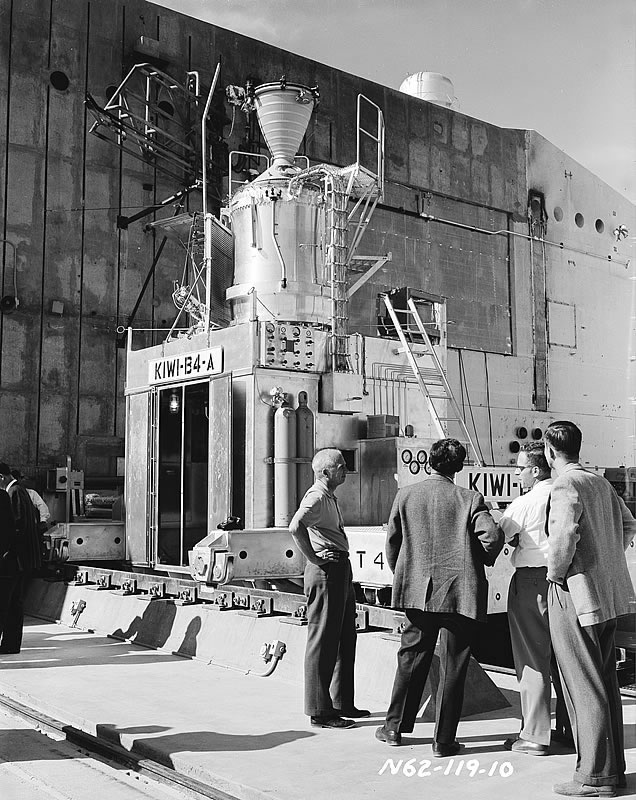

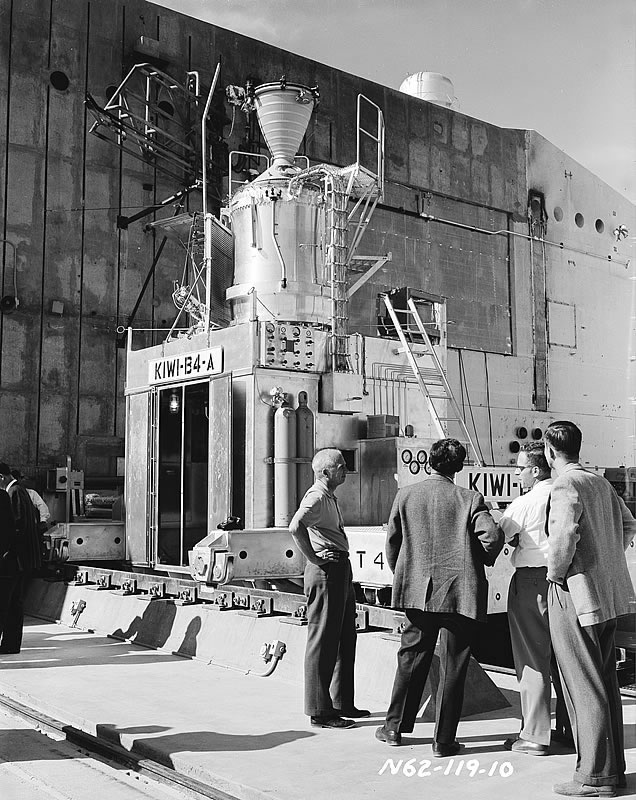

Nuclear reactors for Project Rover were built at LASL Technical Area 18 (TA-18), also known as the Pajarito Site. Fuel and internal engine components were fabricated in the Sigma complex at Los Alamos. Testing of fuel elements and other materials science was done by the LASL N Division at TA-46 using various ovens and later a custom test reactor, the Nuclear Furnace. Staff from the LASL Test (J) and Chemical Metallurgy Baker (CMB) divisions also participated in Project Rover. Two reactors were built for each engine; one for

Nuclear reactors for Project Rover were built at LASL Technical Area 18 (TA-18), also known as the Pajarito Site. Fuel and internal engine components were fabricated in the Sigma complex at Los Alamos. Testing of fuel elements and other materials science was done by the LASL N Division at TA-46 using various ovens and later a custom test reactor, the Nuclear Furnace. Staff from the LASL Test (J) and Chemical Metallurgy Baker (CMB) divisions also participated in Project Rover. Two reactors were built for each engine; one for zero power critical {{Unreferenced, date=August 2009

Zero power critical is a condition of nuclear fission reactors that is useful for characterizing the reactor core. A reactor is in the zero power critical state if it is sustaining a stable fission chain reaction ...

experiments at Los Alamos and another used for full-power testing. The reactors were tested at very low power before being shipped to the test site.

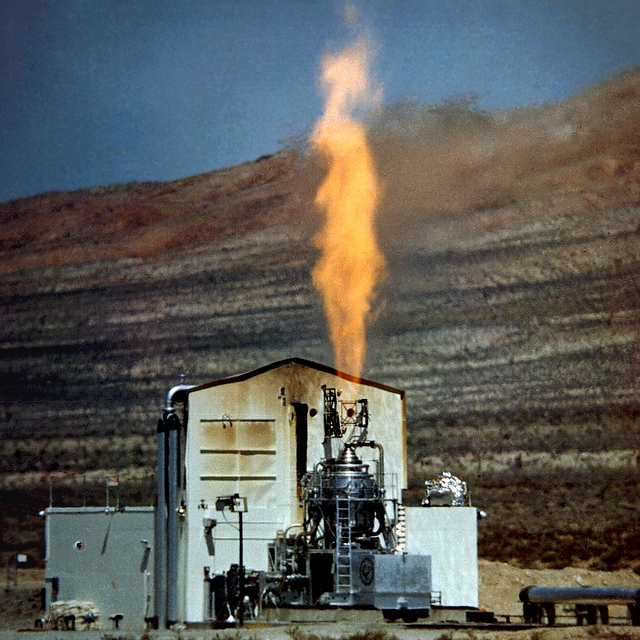

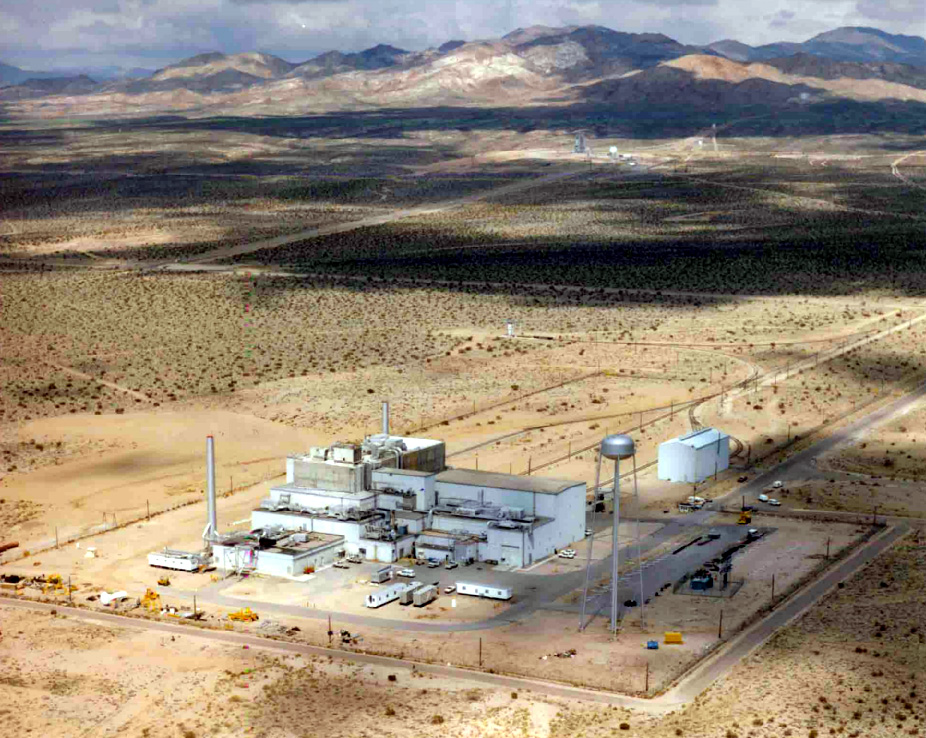

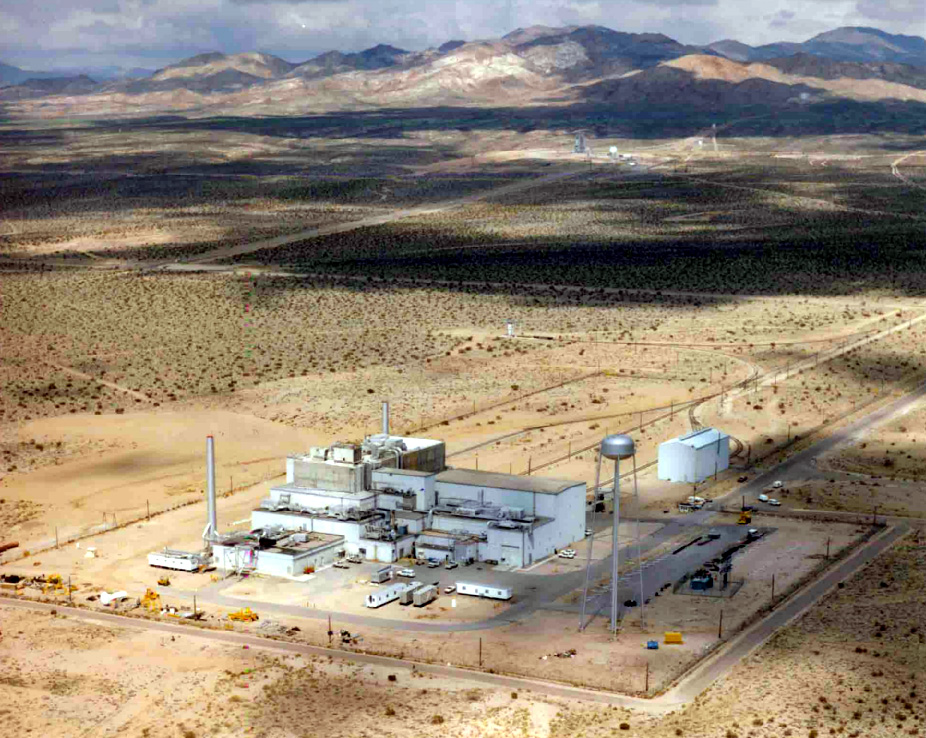

In 1956, the AEC allocated of an area known as Jackass Flats in Area 25 of the Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of th ...

for use by Project Rover. Work commenced on test facilities there in mid-1957. All materials and supplies had to be brought in from Las Vegas

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vegas ...

. Test Cell A consisted of a farm of hydrogen gas bottles and a concrete wall thick to protect the electronic instrumentation from radiation from the reactor. The control room

A control room or operations room is a central space where a large physical facility or physically dispersed service can be monitored and controlled. It is often part of a larger command center.

Overview

A control room's purpose is produc ...

was located away. The plastic coating on the control cables was chewed by burrowing rodents and had to be replaced. The reactor was test-fired with its exhaust plume in the air so that any radioactive fission products

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the release ...

picked up from the core could be safely dispersed.

The reactor maintenance and disassembly building (R-MAD) was in most respects a typical hot cell

Shielded nuclear radiation containment chambers are commonly referred to as hot cells. The word "hot" refers to radioactivity.

Hot cells are used in both the nuclear-energy and the nuclear-medicines industries.

They are required to protect ind ...

used by the nuclear industry, with thick concrete walls, lead glass

Lead glass, commonly called crystal, is a variety of glass in which lead replaces the calcium content of a typical potash glass. Lead glass contains typically 18–40% (by weight) lead(II) oxide (PbO), while modern lead crystal, historically als ...

viewing windows, and remote manipulation arms. It was exceptional only for its size: long, and high. This allowed the engine to be moved in and out on a railroad car. The "Jackass and Western Railroad", as it was light-heartedly described, was said to be the world's shortest and slowest railroad. There were two locomotives: the electric L-1, which was remotely controlled, and the diesel-electric L-2, which was manually controlled, with radiation shielding around the cab.

Test Cell C was supposed to be completed in 1960, but NASA and AEC did not request funds for additional construction that year; Anderson provided them anyway. Then there were construction delays, forcing him to personally intervene. In August 1961, the Soviet Union ended the nuclear test moratorium that had been in place since November 1958, so Kennedy resumed US testing in September. With a second crash program at the Nevada Test site, labor became scarce, and there was a strike.

When that ended, the workers had to come to grips with the difficulties of dealing with hydrogen, which could leak through microscopic holes too small to permit the passage of other fluids. On 7 November 1961, a minor accident caused a violent hydrogen release. The complex finally became operational in 1964. SNPO envisaged the construction of a 20,000 MW nuclear rocket engine, so construction supervisor, Keith Boyer had the

When that ended, the workers had to come to grips with the difficulties of dealing with hydrogen, which could leak through microscopic holes too small to permit the passage of other fluids. On 7 November 1961, a minor accident caused a violent hydrogen release. The complex finally became operational in 1964. SNPO envisaged the construction of a 20,000 MW nuclear rocket engine, so construction supervisor, Keith Boyer had the Chicago Bridge & Iron Company

CB&I is a large engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) company with its administrative headquarters in The Woodlands, Texas. CB&I specializes in projects for oil and gas companies. CB&I employs more than 32,000 people worldwide. In May ...

construct two gigantic cryogenic storage dewar

A cryogenic storage dewar (named after James Dewar) is a specialised type of vacuum flask used for storing cryogens (such as liquid nitrogen or liquid helium), whose boiling points are much lower than room temperature. Cryogenic storage dew ...

s. An engine maintenance and disassembly building (E-MAD) was added. It was larger than a football field, with thick concrete walls and shield bays where engines could be assembled and disassembled. There was also an engine test stand (ETS-1); two more were planned.

There was also a radioactive material storage facility (RMSF). This was a site roughly equidistant from the E-MAD, Test Cell "C", and ETS-1. It was enclosed by a cyclone wire fence with quartz perimeter lighting. The single-track railroad that connected facilities carried one branch through a single main gate into the storage area, which then separated into seven spurs. Two spurs led into bunkers. The facility was used to store a wide variety of radioactively contaminated items.

In February 1962, NASA announced the establishment of the Nuclear Rocket Development Station (NRDS) at Jackass Flats, and in June an SNPO branch was established at Las Vegas (SNPO-N) to manage it. Construction workers were housed in Mercury, Nevada

Mercury is a closed village in Nye County, Nevada, United States, north of U.S. Route 95 at a point northwest of Las Vegas. It is situated within the Nevada National Security Site and was constructed by the Atomic Energy Commission to hou ...

. Later thirty trailers were brought to Jackass Flats to create a village named "Boyerville" after the supervisor, Keith Boyer.

Kiwi

The first phase of Project Rover, Kiwi, was named after the flightless bird of the same name from New Zealand, as the Kiwi rocket engines were not intended to fly either. Their function was to verify the design and test the behavior of the materials used. The Kiwi program developed a series of non-flyable test nuclear engines, with the primary focus on improving the technology of hydrogen-cooled reactors. Between 1959 and 1964, a total of eight reactors were built and tested. Kiwi was considered to have served as aproof of concept

Proof of concept (POC or PoC), also known as proof of principle, is a realization of a certain method or idea in order to demonstrate its feasibility, or a demonstration in principle with the aim of verifying that some concept or theory has prac ...

for nuclear rocket engines.

Kiwi A

The first test of the Kiwi A, the first model of the Kiwi rocket engine, was conducted at Jackass Flats on 1 July 1959. Kiwi A had a cylindrical core high and in diameter. A central island contained heavy water that acted both as a coolant and as a moderator to reduce the amount of uranium oxide required. The control rods were located inside the island, which was surrounded by 960 graphite fuel plates loaded with uranium oxide fuel particles and a layer of 240 graphite plates. The core was surrounded by of graphite wool moderator and encased in an aluminum shell. Gaseous hydrogen was used as a propellant, at a flow rate of . Intended to produce 100 MW, the engine ran at 70 MW for 5 minutes. The core temperature was much higher than expected, up to , due to cracking of the graphite plates, which was enough to cause some of the fuel to melt.

A series of improvements were made for the next test on 8 July 1960 to create an engine known as Kiwi A Prime. The fuel elements were extruded into cylinders and coated with

The first test of the Kiwi A, the first model of the Kiwi rocket engine, was conducted at Jackass Flats on 1 July 1959. Kiwi A had a cylindrical core high and in diameter. A central island contained heavy water that acted both as a coolant and as a moderator to reduce the amount of uranium oxide required. The control rods were located inside the island, which was surrounded by 960 graphite fuel plates loaded with uranium oxide fuel particles and a layer of 240 graphite plates. The core was surrounded by of graphite wool moderator and encased in an aluminum shell. Gaseous hydrogen was used as a propellant, at a flow rate of . Intended to produce 100 MW, the engine ran at 70 MW for 5 minutes. The core temperature was much higher than expected, up to , due to cracking of the graphite plates, which was enough to cause some of the fuel to melt.

A series of improvements were made for the next test on 8 July 1960 to create an engine known as Kiwi A Prime. The fuel elements were extruded into cylinders and coated with niobium carbide

Niobium carbide ( Nb C and Nb2C) is an extremely hard refractory ceramic material, commercially used in tool bits for cutting tools. It is usually processed by sintering and is a frequent additive as grain growth inhibitor in cemented carbides. It ...

() to resist corrosion. Six were stacked end-to-end and then placed in the seven holes in the graphite modules to create long fuel modules. This time the reactor attained 88 MW for 307 seconds, with an average core exit gas temperature of 2,178 K. The test was marred by three core module failures, but the majority suffered little or no damage. The test was observed by Anderson and delegates to the 1960 Democratic National Convention

The 1960 Democratic National Convention was held in Los Angeles, California, on July 11–15, 1960. It nominated Senator John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts for president and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas for vice president.

In ...

. At the convention, Anderson added support for nuclear rockets to the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

platform.

The third and final test of the Kiwi A series was conducted on 19 October 1960. The Kiwi A3 engine used long cylindrical fuel elements in niobium carbide liners. The test plan called for the engine to be run at 50 MW (half power) for 106 seconds, and then at 92 MW for 250 seconds. The 50 MW power level was achieved with a propellant flow of , but exit gas temperature was 1,861 K, which was over 300 K higher than expected. After 159 seconds, the power was increased to 90 MW. To stabilize the exit gas temperature at 2,173 K, the fuel rate was increased to . It was later discovered that the neutronic power measuring system was incorrectly calibrated, and the engine was actually run at an average of 112.5 MW for 259 seconds, well above its design capacity. Despite this, the core suffered less damage than in the Kiwi A Prime test.

Kiwi A was considered a success as a proof of concept for nuclear rocket engines. It demonstrated that hydrogen could be heated in a nuclear reactor to the temperatures required for space propulsion, and that the reactor could be controlled. Finger went ahead and called for bids from industry for the development of NASA's Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application (NERVA

Nerva (; originally Marcus Cocceius Nerva; 8 November 30 – 27 January 98) was Roman emperor from 96 to 98. Nerva became emperor when aged almost 66, after a lifetime of imperial service under Nero and the succeeding rulers of the Flavian dy ...

) based upon the Kiwi engine design. Rover henceforth became part of NERVA; while Rover dealt with the research into nuclear rocket reactor design, NERVA involved the development and deployment of nuclear rocket engines, and the planning of space missions.

Kiwi B

LASL's original objective had been a 10,000 MW nuclear rocket engine capable of launching into a orbit. This engine was codenamed Condor, after the large flying birds, in contrast to the small flightless Kiwi. However, in October 1958, NASA had studied putting a nuclear upper stage on a

LASL's original objective had been a 10,000 MW nuclear rocket engine capable of launching into a orbit. This engine was codenamed Condor, after the large flying birds, in contrast to the small flightless Kiwi. However, in October 1958, NASA had studied putting a nuclear upper stage on a Titan I

The Martin Marietta SM-68A/HGM-25A Titan I was the United States' first multistage intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), in use from 1959 until 1962. Though the SM-68A was operational for only three years, it spawned numerous follow-on mod ...

missile, and concluded that in this configuration a 1,000 MW reactor upper stage could put into orbit. This configuration was used in studies of Nova

A nova (plural novae or novas) is a transient astronomical event that causes the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently "new" star (hence the name "nova", which is Latin for "new") that slowly fades over weeks or months. Causes of the dramati ...

, and became the goal of Project Rover. LASL planned to conduct two tests with Kiwi B, an intermediate 1,000 MW design, in 1961 and 1962, followed by two tests of Kiwi C, a prototype engine, in 1963, and have a reactor in-flight test (RIFT) of a production engine in 1964.

For Kiwi B, LASL made several design changes to get the required higher performance. The central core was eliminated, the number of coolant holes in each hexagonal fuel element was increased from four to seven, and the graphite reflector was replaced with a thick beryllium one. Although beryllium was more expensive, more difficult to fabricate, and highly toxic, it was also much lighter, resulting in a saving of . Due to the delay in getting Test Cell C ready, some features intended for Kiwi C were also incorporated in Kiwi B2. These included a nozzle cooled by liquid hydrogen instead of water, a new Rocketdyne

Rocketdyne was an American rocket engine design and production company headquartered in Canoga Park, California, Canoga Park, in the western San Fernando Valley of suburban Los Angeles, California, Los Angeles, in southern California.

The Rocke ...

turbopump, and a bootstrap start, in which the reactor was started up under its own power only.

The test of Kiwi B1A, the last test to use gaseous hydrogen instead of liquid, was initially scheduled for 7 November 1961. On the morning of the test, a leaking valve resulted in a violent hydrogen explosion that blew out the walls of the shed and injured several workers; many suffered ruptured eardrums, and one fractured a heel bone. The reactor was undamaged, but there was extensive damage to the test car and the instrumentation, resulting in the test being postponed for a month. A second attempt on 6 December was aborted when it was discovered that many of the diagnostic thermocouple

A thermocouple, also known as a "thermoelectrical thermometer", is an electrical device consisting of two dissimilar electrical conductors forming an electrical junction. A thermocouple produces a temperature-dependent voltage as a result of the ...

s had been installed backward. Finally, on 7 December, the test got under way. It was intended to run the engine at 270 MW for 300 seconds, but the test was scram

A scram or SCRAM is an emergency shutdown of a nuclear reactor effected by immediately terminating the fission reaction. It is also the name that is given to the manually operated kill switch that initiates the shutdown. In commercial reactor ...

med after only 36 seconds at 225 MW because hydrogen fires started to appear. All the thermocouples performed correctly, so a great deal of useful data was obtained. The average hydrogen mass flow during the full power portion of the experiment was .

LASL next intended to test Kiwi B2, but structural flaws were found that required a redesign. Attention then switched to B4, a more radical design, but when they tried to put the fuel clusters into the core, the clusters were found to have too many neutrons, and it was feared that the reactor might unexpectedly start up. The problem was traced to absorption of water from the normally dry New Mexico air during storage. It was corrected by adding more neutron poison. After this, fuel elements were stored in an inert atmosphere. N Division then decided to test with the backup B1 engine, B1B, despite grave doubts about it based on the results of the B1A test, in order to obtain more data on the performance and behavior of liquid hydrogen. On startup on 1 September 1962, the core shook, but reached 880 MW. Flashes of light around the nozzle indicated that fuel pellets were being ejected; it was later determined that eleven had been. Rather than shut down, the testers rotated the drums to compensate, and were able to continue running at full power for a few minutes before a sensor blew and started a fire, and the engine was shut down. Most but not all of the test objectives were met.