Polish Army in the United Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Polish Armed Forces in the West () refers to the

The Polish Armed Forces in the West () refers to the

Google Print, p.139

/ref> At the capitulation of France, General

Polish veterans to take pride of place in victory parade

, ''

THE VICTORY PARADE

Last accessed on 31 March 2007. Lynne Olson, Stanley Cloud, ''A Question of Honor: The Kosciuszko Squadron: Forgotten Heroes of World War II '', Knopf, 2003,

Excerpt (prologue)

. At first the British Government invited representatives of the newly recognised regime in Warsaw to march in the Parade, but the delegation from Poland never arrived, the reason never being adequately explained; pressure from Moscow is the most likely explanation. Bowing to press and public pressure, the British eventually invited Polish veterans of the RAF that then represented the Polish Air Force under British Command, to attend in their place. They, in turn, refused to attend in protest at similar invitations not being extended to the Polish Army and Navy. The only Polish representative at the parade was Colonel Józef Kuropieska, the military attaché of the Communist regime in Warsaw, who attended as a diplomatic courtesy. The formation was disbanded in 1947, many of its soldiers choosing to remain in exile rather than to return to communist-controlled Poland, where they were often seen by the Polish communists as "enemies of the state", influenced by the Western ideas, loyal to the Polish government in exile, and thus meeting with persecution and imprisonment (in extreme cases, death). Failure of allied Western governments to keep their promise to Poland, which now fell under the

The Polish Air Force fought in the Battle of France as one fighter squadron GC 1/145, several small units detached to French squadrons, and numerous flights of industry defence (approximately 130 pilots, who achieved 55 victories at a loss of 15 men).Wojsko Polskie we Francji

The Polish Air Force fought in the Battle of France as one fighter squadron GC 1/145, several small units detached to French squadrons, and numerous flights of industry defence (approximately 130 pilots, who achieved 55 victories at a loss of 15 men).Wojsko Polskie we Francji

Świat Polonii. Please note that various sources give estimates that can differ by few percent. From the very beginning of the war, the

/ref>Polish contribution to the Allied victory in World War 2 (1939-1945)

, PDF at the site of Polish Embassy (Canada) The Polish Air Force also fought in 1943 in

The Polish Air Force also fought in 1943 in

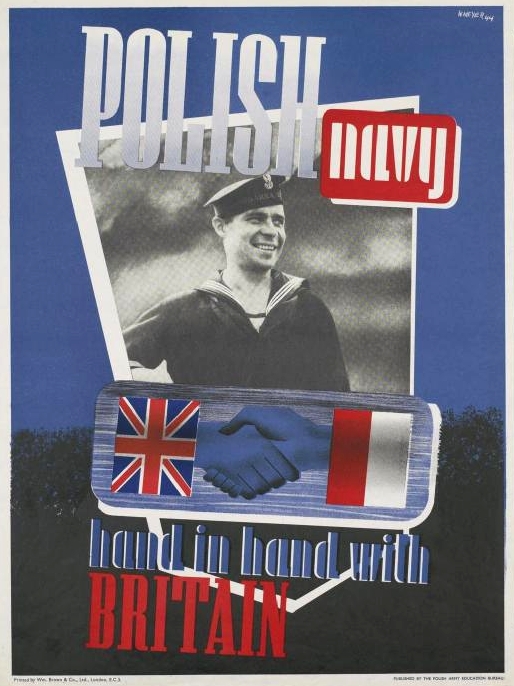

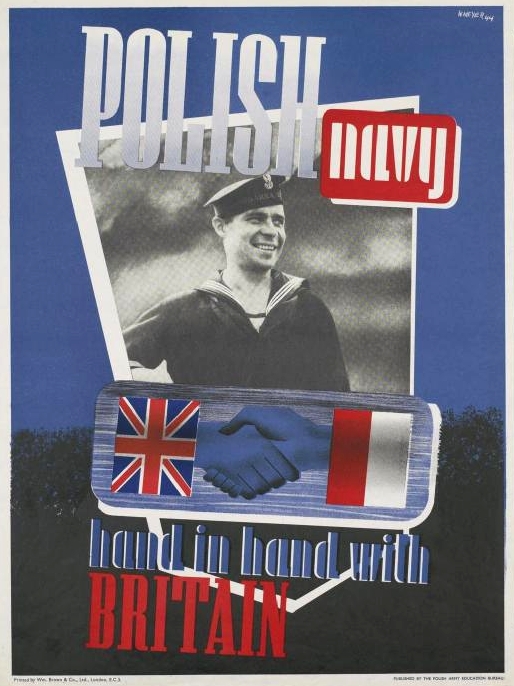

Just on the eve of war, three destroyers—representing most of the major Polish Navy ships—had been sent for safety to the British Isles ( Operation Peking). There they fought alongside the

Just on the eve of war, three destroyers—representing most of the major Polish Navy ships—had been sent for safety to the British Isles ( Operation Peking). There they fought alongside the

. Retrieved on 31 July 2007.

Retrieved on 31 July 2007. * Cruisers: ** ORP ''Dragon'' () ** ORP ''Conrad'' (''Danae'' class) * Destroyers: ** ORP ''Burza'' ("Storm") () ** ORP ''Grom'' ("Thunder") () – lost 1940 ** ORP ''Błyskawica'' ("Lightning") (''Grom'' class) ** ORP ''Garland'' ( G-class) ** ORP ''Orkan'' ( M-class), - torpedoed October 1943 ** OF ''Ouragan'' ("Hurricane", also known in some Polish sources as ''Huragan'') () - returned to Free French in 1941 ** ORP ''Piorun'' ("Thunderbolt") ( N-class) - 1940 onwards *

Lecture notes of prof Anna M. Cienciala. Last accessed on 21 December 2006.); while in the West supplies were gathered for the resistance, and elite commandos, the

Military contribution of Poland to World War II

Polish Ministry of Defence official page

Polish contribution to the Allied victory in World War 2 (1939-1945)

PDF at the site of Polish Embassy (Canada)

The Poles on the Fronts of WW2

Personnel of the Polish Air Force in Great Britain 1940-1947

Polish Exile Forces in the West in World War II

*

* Listen to Lynn Olsen & Stanley Cloud, authors of "A Question of Honor," speak about the "Kościuszko" Squadron and Polish contribution to World War I

here.

{{Authority control Military units and formations established in 1939 Military units and formations disestablished in 1947 Military units and formations of Poland in World War II Armies in exile during World War II

The Polish Armed Forces in the West () refers to the

The Polish Armed Forces in the West () refers to the Polish military

The Armed Forces of the Republic of Poland ( pl, Siły Zbrojne Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, abbreviated ''SZ RP''; popularly called ''Wojsko Polskie'' in Poland, abbreviated ''WP''—roughly, the "Polish Military") are the national armed forces of ...

formations formed to fight alongside the Western Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and its allies during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Polish forces were also raised within Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

territories; these were the Polish Armed Forces in the East

The Polish Armed Forces in the East ( pl, Polskie Siły Zbrojne na Wschodzie), also called Polish Army in the USSR, were the Polish Armed Forces, Polish military forces established in the Soviet Union during World War II.

Two armies were formed ...

.

The formations, loyal to the Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

, were first formed in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

and its Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

territories following the defeat and occupation of Poland by Germany and the Soviet Union in September 1939. After the fall of France in June 1940, the formations were recreated in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. Making a large contribution to the war effort, the Polish Armed Forces in the West was composed of army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, air

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing f ...

and naval forces. The Poles soon became shock troops

Shock troops or assault troops are formations created to lead an attack. They are often better trained and equipped than other infantry, and expected to take heavy casualties even in successful operations.

"Shock troop" is a calque, a loose tra ...

in Allied service, most notably in the Battle of Monte Cassino during the Italian Campaign, where the Polish flag was raised on the ruined abbey on 18 May 1944, as well as in the Battle of Bologna

The Battle of Bologna was fought in Bologna, Italy from 9–21 April 1945 during the Second World War, as part of the Spring 1945 offensive in Italy. The Allied forces were victorious, with the Polish II Corps and supporting Allied units capturi ...

and the Battle of Ancona

The Battle of Ancona was a battle involving forces from Poland serving as part of the British Army against German forces that took place from 16 June–18 July 1944 during the Italian campaign in World War II. The battle was the result of an All ...

(both also in Italy), and Hill 262

Battle of Hill 262, or the Mont Ormel ridge (elevation ), is an area of high ground above the village of Coudehard in Normandy that was the location of a bloody engagement in the final stages of the Battle of Falaise in the Normandy Campaign du ...

in France in 1944. The Polish Armed Forces in the West were disbanded after the war, in 1947, with many former servicemen forced to remain in exile.

General history

After Poland's defeat in September–October 1939, thePolish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

quickly organized in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

a new fighting force originally of about 80,000 men. Their units were subordinate to the French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed Force ...

. In early 1940, a Polish Independent Highland Brigade

The Polish Independent Highland Brigade () was a Polish military unit created in France in 1939, after the fall of Poland, as part of the Polish Army in France. It had approximately 5,000 soldiers trained in mountain warfare and was commanded ...

took part in the Battles of Narvik

The Battles of Narvik were fought from 9 April to 8 June 1940, as a naval battle in the Ofotfjord and as a land battle in the mountains surrounding the north Norwegian town of Narvik, as part of the Norwegian Campaign of the Second World War.

...

in Norway. A Polish Independent Carpathian Brigade

Polish Independent Carpathian Brigade ( Polish ''Samodzielna Brygada Strzelców Karpackich'', SBSK) was a Polish military unit formed in 1940 in French Syria composed of Polish soldiers exiled after the invasion of Poland in 1939 as part of the ...

was formed in the French Mandate of Syria, to which many Polish troops had escaped from Poland. The Polish Air Force in France comprised 86 aircraft in four squadrons; one-and-a-half of the squadrons were fully operational, while the rest were in various stages of training. Two Polish divisions (First Grenadier Division

The 1st Grenadier Division (; ) was a Polish infantry formation raised in France during the Phoney War. The division was created as a part of the Polish Army in France (1939–40), Polish Army in France following the Invasion of Poland. The divisi ...

, and Second Infantry Fusiliers Division

The 2nd Rifle Division ( pl, 2 Dywizja Strzelców Pieszych, french: 2e Division des Chasseurs or ''2e Division d'Infanterie Polonaise'') was a Polish Army unit, part of the recreated Polish Army in France in 1940.

The division (numbering 15,830 s ...

) took part in the defence of France, while a Polish motorized brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

B ...

and two infantry divisions were being formed. James Dunnigan, Albert Nofi

Albert A. Nofi (born January 6, 1944), is an American military historian, defense analyst, and designer of board and computer wargaming systems.

Early life

A native of Brooklyn, he attended New York City public schools, graduating from the Boys' ...

; ''Dirty Little Secrets of World War II: Military Information No One Told You About the Greatest, Most Terrible War in History'', HarperCollins, 1996, Google Print, p.139

/ref> At the capitulation of France, General

Władysław Sikorski

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (; 20 May 18814 July 1943) was a Polish military and political leader.

Prior to the First World War, Sikorski established and participated in several underground organizations that promoted the cause for Polish i ...

(the Polish commander-in-chief and prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

) was able to evacuate many Polish troops—probably over 20,000—to the United Kingdom.

The Polish Navy had been the first to regroup off the shores of the United Kingdom. Polish ships and sailors had been sent to Britain in mid-1939 by General Sikorski, and a Polish-British Naval agreement was signed in November of the same year. Under this agreement, Polish sailors were permitted to don Polish uniforms, and their commanding officers were Polish; however, the ships used were of British manufacture. By 1940, the sailors had already impressed Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, who remarked that he had "rarely seen a finer body of men".

After being evacuated after the defeat of France, Polish fliers had an important role in the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. At first, the Polish pilots were overlooked, despite being numerous (close to 8,500 by mid-1940). Despite having flown for years, most of them were posted either to RAF bomber squadrons or the RAF Volunteer Reserve

The Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) was established in 1936 to support the preparedness of the U.K. Royal Air Force in the event of another war. The Air Ministry intended it to form a supplement to the Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAuxAF) ...

. This was due to lack of understanding in the face of Polish defeat by the Germans, as well as language barriers and British commanders' opinion of Polish attitudes. On 11 June 1940, the Polish Government in Exile signed an agreement with the British Government to form a Polish Air Force in the UK, and in July 1940 the RAF announced that it would form two Polish fighter squadrons equipped with British planes: 302 "Poznański" Squadron and 303 "Kościuszko" Squadron. The squadrons were composed of Polish pilots and ground crews, although their flight commanders and commanding officers were British. Once given the opportunity to fly, it did not take long for their British counterparts to appreciate the tenacity of the Poles. Even Air Officer Commanding Hugh Dowding

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, 1st Baron Dowding, (24 April 1882 – 15 February 1970) was an officer in the Royal Air Force. He was Air Officer Commanding RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain and is generally c ...

, who had been one of the first to voice his doubt of the Poles, said: "I must confess that I had been a little doubtful of the effect which their experience in their own countries and in France might have had upon the Polish and Czech pilots, but my doubts were laid to rest, because all three squadrons swung into the fight with a dash and enthusiasm which is beyond praise. They were inspired by a burning hatred for the Germans which made them very deadly opponents." Dowding later stated further that "had it not been for the magnificent ork ofthe Polish squadrons and their unsurpassed gallantry, I hesitate to say that the outcome of the Battle would have been the same."

As for ground troops, some Polish ground units regrouped in southern Scotland. These units, as Polish I Corps, comprised the 1st Independent Rifle Brigade, the 10th Motorised Cavalry Brigade (as infantry) and cadre brigades (largely manned by surplus officers at battalion strength) and took over responsibility in October 1940 for the defence of the counties of Fife and Angus; this included reinforcing coastal defences that had already been started. I Corps was under the direct command of Scottish Command

Scottish Command or Army Headquarters Scotland (from 1972) is a command of the British Army.

History Early history

Great Britain was divided into military districts on the outbreak of war with France in 1793. The Scottish District was comman ...

of the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

. Whilst in this area, the Corps was reorganised and expanded. The opportunity to form another Polish army came in 1941, following an agreement between the Polish government in exile and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in ...

releasing Polish soldiers, civilians and citizens from imprisonment. From these, a 75,000-strong army was formed in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

under General Władysław Anders

)

, birth_name = Władysław Albert Anders

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Krośniewice-Błonie, Warsaw Governorate, Congress Poland, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = London, England, United Kingdom

, serviceyear ...

and informally known as "Anders' Army

Anders' Army was the informal yet common name of the Polish Armed Forces in the East in the 1941–42 period, in recognition of its commander Władysław Anders. The army was created in the Soviet Union but, in March 1942, based on an understand ...

". This army, successively gathered in Bouzoulouk, Samarkand, was later ferried from Krasnovodsk across the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia ...

to the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

(Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

) where Polish II Corps

The Polish II Corps ( pl, Drugi Korpus Wojska Polskiego), 1943–1947, was a major tactical and operational unit of the Polish Armed Forces in the West during World War II. It was commanded by Lieutenant General Władysław Anders and fought wit ...

was formed from it and other units in 1943.

By March 1944, the Polish Armed Forces in the West, fighting under British command, numbered 165,000 at the end of that year, including about 20,000 personnel in the Polish Air Force and 3,000 in the Polish Navy. By the end of the Second World War, they were 195,000 strong, and by July 1945 had increased to 228,000, most of the newcomers being released prisoners-of-war and ex- labor camp inmates.

The Polish Armed Forces in the West fought in most Allied operations against Nazi Germany in the Mediterranean and Middle East and European theatres: the North African Campaign, the Italian Campaign (with the Battle of Monte Cassino being one of the most notable), the Western European Campaign (from Dieppe Raid and D-Day through Battle of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

and latter operations, especially Operation Market Garden).

After the German Instrument of Surrender

The German Instrument of Surrender (german: Bedingungslose Kapitulation der Wehrmacht, lit=Unconditional Capitulation of the " Wehrmacht"; russian: Акт о капитуляции Германии, Akt o kapitulyatsii Germanii, lit=Act of capi ...

, Polish troops took part in occupation duties in the Western Allied Occupation Zones in Germany. A Polish town was created: it was first named Lwow, then Maczkow.

Polish troops were factored into the British 1945 top secret contingency plan

A contingency plan, also known colloquially as Plan B, is a plan devised for an outcome other than in the usual (expected) plan. It is often used for risk management for an exceptional risk that, though unlikely, would have catastrophic conseque ...

, Operation Unthinkable

Operation Unthinkable was the name given to two related possible future war plans by the British Chiefs of Staff Committee against the Soviet Union in 1945. The plans were never implemented. The creation of the plans was ordered by British Prime ...

, which considered a possible attack on the Soviet Union in order to enforce an independent Poland.

Denouncement

By 1945, there was growinganti-Polish sentiment

Polonophobia, also referred to as anti-Polonism, ( pl, Antypolonizm), and anti-Polish sentiment are terms for negative attitudes, prejudices, and actions against Poles as an ethnic group, Poland as their country, and their culture. These incl ...

in Britain, particularly among the trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

—which feared competition for jobs from Polish immigrants—and from Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–194 ...

. At the same time, there was British and American concern about a police state

A police state describes a state where its government institutions exercise an extreme level of control over civil society and liberties. There is typically little or no distinction between the law and the exercise of political power by the ...

being built in Poland.

In March 1945, ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' reported on Polish "Surplus Heroes", stating that Bevin

promised Anders that those of his soldiers who did not want to return to the new Poland could find asylum in the British Empire. Argentina and Brazil were also reported ready to offer them homes. But Britain thought the best solution would be for them to return to Poland, and Britain was circulating an appeal through the Polish Army containing the Polish Government's pledge to treat the soldier exiles fairly. Anders argued that he could not advise the soldiers to return to Poland unless the Polish Government promised elections this spring. Bevin, too, wanted immediate Polish elections, but both men knew that the chances were becoming slimmer. In Poland the split between the Communist-Socialist groups and shrewd Stanislaw Mikolajczyk's Polish Peasant Party was deepening. Security Police raids on Peasant Party headquarters were reported last week. If efforts to smash the Mikolajczyk forces failed, then the Communist-Socialist groups would fight for a late fall election, when the popularity of the Polish Peasant Party, sure winner of an election now, might have waned. Nevertheless, Bevin argued that, elections or no, the Poles in Anders' army should go home.In January 1946, Bevin protested against killings by the Polish provisional government, which defended its actions saying it was fighting terrorists loyal to Anders and funded by the British. In February 1946, ''Time'' reported "Britain's Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin told a tense House of Commons last week that terror had become an instrument of national policy in the new Poland. Many members of Vice Premier Stanislaw Mikolajczyk's Polish Peasant Party who opposed the Communist-dominated Warsaw Government had been murdered. "Circumstances in many cases appear to point to the complicity of the Polish Security Police. ... I regard it as imperative that the Polish Provisional Government should put an immediate stop to these crimes in order that free and unfettered elections may be held as soon as possible, in accordance with the Crimea decision. ... I am looking forward to the end of these police states ...", while the Polish government blamed Anders and his British backers for the bloodshed there. It is often said that the Polish Armed Forces in the West were not invited to the London Victory Parade of 1946.Kwan Yuk Pan

Polish veterans to take pride of place in victory parade

, ''

Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and published digitally that focuses on business and economic current affairs. Based in London, England, the paper is owned by a Japanese holding company, Ni ...

'', 5 July 2005. Last accessed on 31 March 2006.Rudolf FalkowskiTHE VICTORY PARADE

Last accessed on 31 March 2007. Lynne Olson, Stanley Cloud, ''A Question of Honor: The Kosciuszko Squadron: Forgotten Heroes of World War II '', Knopf, 2003,

Excerpt (prologue)

. At first the British Government invited representatives of the newly recognised regime in Warsaw to march in the Parade, but the delegation from Poland never arrived, the reason never being adequately explained; pressure from Moscow is the most likely explanation. Bowing to press and public pressure, the British eventually invited Polish veterans of the RAF that then represented the Polish Air Force under British Command, to attend in their place. They, in turn, refused to attend in protest at similar invitations not being extended to the Polish Army and Navy. The only Polish representative at the parade was Colonel Józef Kuropieska, the military attaché of the Communist regime in Warsaw, who attended as a diplomatic courtesy. The formation was disbanded in 1947, many of its soldiers choosing to remain in exile rather than to return to communist-controlled Poland, where they were often seen by the Polish communists as "enemies of the state", influenced by the Western ideas, loyal to the Polish government in exile, and thus meeting with persecution and imprisonment (in extreme cases, death). Failure of allied Western governments to keep their promise to Poland, which now fell under the

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

sphere of influence, became known as the "Western betrayal

Western betrayal is the view that the United Kingdom, France, and sometimes the United States failed to meet their legal, diplomatic, military, and moral obligations with respect to the Czechoslovak and Polish states during the prelude to and ...

." The number of Polish ex-soldiers unwilling to return to communist Poland was so high that a special organization was formed by the British government to assist settling them in the United Kingdom: the Polish Resettlement Corps

The Polish Resettlement Corps (PRC; pl, Polski Korpus Przysposobienia i Rozmieszczenia) was an organisation formed by the British Government in 1946 as a holding unit for members of the Polish Armed Forces who had been serving with the British Arm ...

(Polski Korpus Przysposobienia i Rozmieszczenia); 114,000 Polish soldiers went through that organization. Since many Poles had been stationed in the United Kingdom and served alongside British units in the war, the Polish Resettlement Act 1947 permitted all of them to settle in the United Kingdom after the war, multiplying the size of the Polish minority in the UK. Diana M. Henderson, ''The Lion and the Eagle: Polish Second World War Veterans in Scotland'', Cualann Press, 2001, Many also joined the Polish Canadian

Polish Canadians ( pl, Polonia w Kanadzie, french: Canadiens Polonais) are citizens of Canada with Polish ancestry, and Poles who immigrated to Canada from abroad. At the 2016 Census, there were 1,106,585 Canadians who claimed full or partial ...

and Polish Australian communities. After the United States Congress passed a 1948 law, amended in 1950, which allowed the immigration of Polish soldiers who were demobilized in Great Britain, a number of them moved to the U.S. where, in 1952, they organized the association Polish Veterans of World War II.

History by formation

Army

The Polish Army in France, which began to be organized soon after the fall of Poland in 1939, was composed of about 85,000 men. Four Polish divisions (First Grenadier Division

The 1st Grenadier Division (; ) was a Polish infantry formation raised in France during the Phoney War. The division was created as a part of the Polish Army in France (1939–40), Polish Army in France following the Invasion of Poland. The divisi ...

, Second Infantry Fusiliers Division

The 2nd Rifle Division ( pl, 2 Dywizja Strzelców Pieszych, french: 2e Division des Chasseurs or ''2e Division d'Infanterie Polonaise'') was a Polish Army unit, part of the recreated Polish Army in France in 1940.

The division (numbering 15,830 s ...

, 3rd and 4th infantry divisions), a Polish motorized brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

B ...

( 10th Brigade of Armored Cavalry, ''10éme Brigade de cavalerie blindée'') and infantry brigade (Polish Independent Highland Brigade

The Polish Independent Highland Brigade () was a Polish military unit created in France in 1939, after the fall of Poland, as part of the Polish Army in France. It had approximately 5,000 soldiers trained in mountain warfare and was commanded ...

) were organized in mainland France. Polish Independent Highland Brigade

The Polish Independent Highland Brigade () was a Polish military unit created in France in 1939, after the fall of Poland, as part of the Polish Army in France. It had approximately 5,000 soldiers trained in mountain warfare and was commanded ...

took part in the Battles of Narvik

The Battles of Narvik were fought from 9 April to 8 June 1940, as a naval battle in the Ofotfjord and as a land battle in the mountains surrounding the north Norwegian town of Narvik, as part of the Norwegian Campaign of the Second World War.

...

in early 1940; after the German invasion of France

France has been invaded on numerous occasions, by foreign powers or rival French governments; there have also been unimplemented invasion plans.

* the 1746 War of the Austrian Succession, Austria-Italian forces supported by the British navy attemp ...

, all Polish units were pressed into formation although, due to inefficient French logistics and policies, all Polish units were missing much equipment and supplies—particularly the 3rd and 4th divisions, which were still in the middle of organization. In French-mandated Syria, a Polish Independent Carpathian Brigade

Polish Independent Carpathian Brigade ( Polish ''Samodzielna Brygada Strzelców Karpackich'', SBSK) was a Polish military unit formed in 1940 in French Syria composed of Polish soldiers exiled after the invasion of Poland in 1939 as part of the ...

was formed to which about 4,000 Polish troops had escaped, mostly through Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

and would later fight in the North African Campaign.

After the fall of France (during which about 6,000 Polish soldiers died fighting), about 13,000 Polish personnel had been interned in Switzerland. Nevertheless, Polish commander-in-chief and prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

General Władysław Sikorski

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (; 20 May 18814 July 1943) was a Polish military and political leader.

Prior to the First World War, Sikorski established and participated in several underground organizations that promoted the cause for Polish i ...

was able to evacuate many Polish troops to the United Kingdom (estimates range from 20,000 to 35,000). The Polish I Corps was formed from these soldiers. It comprised the Polish 1st Armoured Division

The Polish 1st Armoured Division (Polish ''1 Dywizja Pancerna'') was an armoured division of the Polish Armed Forces in the West during World War II. Created in February 1942 at Duns in Scotland, it was commanded by Major General Stanisław Macze ...

(which later became attached to the First Canadian Army) and the Polish Independent Parachute Brigade, and other formations, such as the 4th Infantry Division, and the 16th Independent Armoured Brigade

, image =

, caption =

, dates =1941-1943?

, country =

, allegiance =Poland

, branch =Armour

, type =

, role =

, size =

, command_structure =I Corps in the West (Poland)1st Armoured Division (Poland)

, garrison =

, garrison_label =

, ...

. It was commanded by Gen. Stanisław Maczek and Marian Kukiel

Marian Włodzimierz Kukiel (pseudonyms: ''Marek Kąkol'', ''Stach Zawierucha''; 15 May 1885 in Dąbrowa Tarnowska – 15 August 1973 in London) was a Polish major general, historian, social and political activist.

One of the founders of Zwi� ...

. Despite its name, it never reached corps strength and was not used as a tactical unit until after the war, when it took part in the occupation of Germany as part of the Allied forces stationed around the port of Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsh ...

. Prior to that date, its two main units fought separately and were grouped together mostly for logistical reasons. In August 1942, the British Commandos formed No. 6 troop which was integrated into No.10 (Inter-Allied) Commando attached to the 1st Special Service Brigade

The 1st Special Service Brigade was a commando brigade of the British Army. Formed during the Second World War, it consisted of elements of the British Army (including British Commandos) and the Royal Marines. The brigade's component units saw a ...

. No. 6 (Polish) Troop was under the command of Captain Smrokowski and comprised seven officers and 84 men, who were recruited from a variety of different sources. Some were former Polish civilians. Some were Polish Army soldiers taken prisoner after the 1939 German invasion of Poland and forcibly conscripted into the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

, who had then deserted whenever they had the chance. Some came from the 13,000 Polish personnel who were interned by the Swiss government, but who managed to escape Swiss custody and make their way to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

via the British consulates in Switzerland.

In 1941, following an agreement between the Polish government in exile and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, the Soviets released Polish citizens, from whom a 75,000-strong army was formed in the Soviet Union under General Władysław Anders

)

, birth_name = Władysław Albert Anders

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Krośniewice-Błonie, Warsaw Governorate, Congress Poland, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = London, England, United Kingdom

, serviceyear ...

(Anders' Army

Anders' Army was the informal yet common name of the Polish Armed Forces in the East in the 1941–42 period, in recognition of its commander Władysław Anders. The army was created in the Soviet Union but, in March 1942, based on an understand ...

). This army, successively gathered in Bouzoulouk, Samarkand, was later ferried from Krasnovodsk to the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

(Iran) through the Caspian Sea (in March and August 1942). The Polish units later formed the Polish II Corps

The Polish II Corps ( pl, Drugi Korpus Wojska Polskiego), 1943–1947, was a major tactical and operational unit of the Polish Armed Forces in the West during World War II. It was commanded by Lieutenant General Władysław Anders and fought wit ...

. It was composed of Polish 3rd Carpathian Infantry Division, Polish 5th Kresowa Infantry Division, Polish 2nd Armoured Brigade and other units.

Air force

The Polish Air Force fought in the Battle of France as one fighter squadron GC 1/145, several small units detached to French squadrons, and numerous flights of industry defence (approximately 130 pilots, who achieved 55 victories at a loss of 15 men).Wojsko Polskie we Francji

The Polish Air Force fought in the Battle of France as one fighter squadron GC 1/145, several small units detached to French squadrons, and numerous flights of industry defence (approximately 130 pilots, who achieved 55 victories at a loss of 15 men).Wojsko Polskie we FrancjiŚwiat Polonii. Please note that various sources give estimates that can differ by few percent. From the very beginning of the war, the

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

(RAF) had welcomed foreign pilots to supplement the dwindling pool of British pilots. On 11 June 1940, the Polish government in exile signed an agreement with the British government to form a Polish army and Polish air force in the United Kingdom. The first two (of an eventual ten) Polish fighter squadrons went into action in August 1940. Four Polish squadrons eventually took part in the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

(300

__NOTOC__

Year 300 ( CCC) was a leap year starting on Monday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Constantius and Valerius (or, less frequently, year 1053 ''Ab ...

and 301

__NOTOC__

Year 301 ( CCCI) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Postumius and Nepotianus (or, less frequently, year 1054 ...

Bomber Squadrons; 302 and 303

__NOTOC__

Year 303 ( CCCIII) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. It was known in the Roman Empire as the Year of the Consulship of Diocletian and Maximian (or, less frequently, y ...

fighter squadrons), with 89 Polish pilots. Together with more than 50 Poles fighting in British squadrons, about 145 Polish pilots defended British skies. Polish pilots were among the most experienced in the battle, most of them having already fought in the 1939 September Campaign in Poland and the 1940 Battle of France. Additionally, prewar Poland had set a very high standard of pilot training. No. 303 Squadron, named after the Polish-American hero, General Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ( be, Andréj Tadévuš Banavientúra Kasciúška, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish military engineer, statesman, and military leader who ...

, achieved the highest number of kills (126) of all fighter squadrons engaged in the Battle of Britain, even though it only joined the combat on 30 August 1940. These Polish pilots, representing about 5% of total Allied pilots in the Battle, were responsible for 12% of total victories (203) in the Battle and achieved the highest number of kills of any Allied squadron.The Poles in the Battle of Britain/ref>Polish contribution to the Allied victory in World War 2 (1939-1945)

, PDF at the site of Polish Embassy (Canada)

The Polish Air Force also fought in 1943 in

The Polish Air Force also fought in 1943 in Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

(the Polish Fighting Team

The Polish Fighting Team (PFT) ( pl, Polski Zespół Myśliwski), also known as "Skalski's Circus" ( pl, Cyrk Skalskiego), was a Polish unit which fought alongside the British Commonwealth Desert Air Force in the North African Campaign of Wor ...

, known as " Skalski's Circus") and in raids on Germany (1940–45). In the second half of 1941 and early 1942, Polish bomber squadrons were the sixth part of forces available to RAF Bomber Command (later they suffered heavy losses, with little possibility of replenishment). Polish aircrew losses serving with Bomber Command 1940-45 were 929 killed; total Polish aircrew losses were 1,803 killed. Ultimately eight Polish fighter squadrons were formed within the RAF and had claimed 621 Axis aircraft destroyed by May 1945. By the end of the war, around 19,400 Poles were serving in the RAF.

Polish squadrons in the United Kingdom:

* No. 300 "Masovia" Polish Bomber Squadron (''Ziemi Mazowieckiej'')

* No. 301 "Pomerania" Polish Bomber Squadron (''Ziemi Pomorskiej'') 1940 to 1943 when 301 Bomber Squadron merged with 300 Sqn.

* No. 301 "Pomerania and Defenders of Warsaw" Polish Transport "Special Duties" Squadron (''Ziemi Pomorskiej im Obrońców Warszawy'') 1944 to 1946.

* No. 302 "City of Poznan" Polish Fighter Squadron (''Poznański'')

* No. 303 "Kościuszko" Polish Fighter Squadron (''Warszawski imienia Tadeusza Kościuszki'')

* No. 304 "Silesia" Polish Bomber Squadron (''Ziemi Śląskiej imienia Ksiecia Józefa Poniatowskiego'')

* No. 305 "Greater Poland" Polish Bomber Squadron (''Ziemi Wielkopolskiej imienia Marszałka Józefa Piłsudskiego'')

* No. 306 "City of Toruń" Polish Fighter Squadron (''Toruński'')

* No. 307 "City of Lwów" Polish Fighter Squadron (''Lwowskich Puchaczy'')

* No. 308 "City of Kraków" Polish Fighter Squadron (''Krakowski'')

* No. 309 "Czerwień" Polish Fighter-Reconnaissance Squadron (''Ziemi Czerwieńskiej'')

* No. 315 "City of Dęblin" Polish Fighter Squadron (''Dębliński'')

* No. 316 "City of Warsaw" Polish Fighter Squadron (''Warszawski'')

* No. 317 "City of Wilno" Polish Fighter Squadron (''Wileński'')

* No. 318 "City of Gdańsk" Polish Fighter-Reconnaissance Squadron (''Gdański'')

* No. 663 Polish Artillery Observation Squadron

No. 663 Squadron RAF ('' pl, 663 Polski Szwadron Powietrznych Punktów Obserwacyjnych'') was an Air Observation Post (AOP) unit of the Royal Air Force (RAF), manned with Polish Army personnel, which was officially formed in Italy on 14 August 194 ...

* No. 145 Fighter Squadron Polish Fighting Team

The Polish Fighting Team (PFT) ( pl, Polski Zespół Myśliwski), also known as "Skalski's Circus" ( pl, Cyrk Skalskiego), was a Polish unit which fought alongside the British Commonwealth Desert Air Force in the North African Campaign of Wor ...

(''Skalski's Circus'')

Navy

Just on the eve of war, three destroyers—representing most of the major Polish Navy ships—had been sent for safety to the British Isles ( Operation Peking). There they fought alongside the

Just on the eve of war, three destroyers—representing most of the major Polish Navy ships—had been sent for safety to the British Isles ( Operation Peking). There they fought alongside the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

(RN). At various stages of the war, the Polish Navy comprised two cruisers and a large number of smaller ships; most were RN ships loaned to take advantage of availability of Polish crews at a time when the Royal Navy had insufficient manpower to crew all its ships. The Polish Navy fought with great distinction alongside the other Allied navies in many important and successful operations, including those conducted against the German battleship, . With their 26 ships (2 cruisers, 9 destroyers, 5 submarines and 11 torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s), the Polish Navy sailed a total of 1.2 million nautical miles during the war, escorted 787 convoys, conducted 1,162 patrols and combat operations, sank 12 enemy ships (including 5 submarines) and 41 merchant vessels, damaged 24 more (including 8 submarines) and shot down 20 aircraft. The number of seamen who lost their lives in action was 450 out of over 4,000.86 years of the Polish Navy. Retrieved on 31 July 2007.

Retrieved on 31 July 2007. * Cruisers: ** ORP ''Dragon'' () ** ORP ''Conrad'' (''Danae'' class) * Destroyers: ** ORP ''Burza'' ("Storm") () ** ORP ''Grom'' ("Thunder") () – lost 1940 ** ORP ''Błyskawica'' ("Lightning") (''Grom'' class) ** ORP ''Garland'' ( G-class) ** ORP ''Orkan'' ( M-class), - torpedoed October 1943 ** OF ''Ouragan'' ("Hurricane", also known in some Polish sources as ''Huragan'') () - returned to Free French in 1941 ** ORP ''Piorun'' ("Thunderbolt") ( N-class) - 1940 onwards *

Escort destroyer

An escort destroyer with United States Navy hull classification symbol DDE was a destroyer (DD) modified for and assigned to a fleet escort role after World War II. These destroyers retained their original hull numbers. Later, in March 1950, t ...

s

** ORP ''Krakowiak'' ("Cracovian") ( Hunt-class escort) - 1941 onwards

** ORP ''Kujawiak'' ("Kujawian") (Hunt class) - sunk 1942

** ORP ''Ślązak'' ("Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

n") (Hunt class) - 1942 onwards

* Submarines:

** ORP ''Orzeł'' ("Eagle") () – lost 1940

** ORP ''Jastrząb'' ("Hawk") ( American S-class) – lost 1942

** ORP ''Wilk'' ("Wolf") ()

** ORP ''Dzik'' ("Boar") ( British U-class)

** ORP ''Sokół'' ("Falcon") (British U-class) - 1941 onwards

As well as the above, there were a number of minor ships, transports, merchant-marine auxiliary vessels, and patrol boats.

Intelligence and resistance

The Polish intelligence structure remained mostly intact following the fall of Poland in 1939 and continued to report to the Polish Government in Exile. Known as the 'Second Department', it cooperated with the other Allies in everyEurope

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

an country and operated one of the largest intelligence networks in Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. Many Poles also served in other Allied intelligence services, including the celebrated Krystyna Skarbek

Maria Krystyna Janina Skarbek, (, ; 1 May 1908 – 15 June 1952), also known as Christine Granville, was a Polish agent of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) during the Second World War. She became celebrated for her daring exploi ...

(" Christine Granville") in the United Kingdom's Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British World War II organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing secret organisations. Its pu ...

. Forty-three percent of all the reports received by the British secret services from continental Europe in 1939-45 came from Polish sources.

The majority of Polish resistance (particularly the dominant Armia Krajowa organization) were also loyal to the government in exile with the Government Delegate's Office at Home

The Government Delegation for Poland ( pl, Delegatura Rządu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na Kraj) was an agency of the Polish Government in Exile during World War II. It was the highest authority of the Polish Secret State in occupied Poland and was ...

being the highest authority of the Polish Secret State

The Polish Underground State ( pl, Polskie Państwo Podziemne, also known as the Polish Secret State) was a single political and military entity formed by the union of resistance organizations in occupied Poland that were loyal to the Gover ...

. Although military actions of the Polish resistance operating in Poland and its armed forces operating in the West are not commonly grouped together, several important links existed between them, in addition to the common chain of command

A command hierarchy is a group of people who carry out orders based on others' authority within the group. It can be viewed as part of a power structure, in which it is usually seen as the most vulnerable and also the most powerful part.

Milit ...

. Resistance gathered and passed vital intelligence to the West (for example on Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as con ...

and about the V-1 flying bomb and the V-2 rocketEastern Europe in World War II: October 1939-May 1945Lecture notes of prof Anna M. Cienciala. Last accessed on 21 December 2006.); while in the West supplies were gathered for the resistance, and elite commandos, the

Cichociemni

''Cichociemni'' (; the "Silent Unseen") were elite special-operations paratroopers of the Polish Army in exile, created in Great Britain during World War II to operate in occupied Poland (''Cichociemni Spadochroniarze Armii Krajowej''). Kazimi ...

, were trained. The Polish government also wanted to use the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade

The 1st (Polish) Independent Parachute Brigade was a parachute infantry brigade of the Polish Armed Forces in the West under the command of Major General Stanisław Sosabowski, created in September 1941 during the Second World War and based in ...

in Poland, particularly during Operation Tempest

file:Akcja_burza_1944.png, 210px, right

Operation Tempest ( pl, akcja „Burza”, sometimes referred to in English as "Operation Storm") was a series of uprisings conducted during World War II against occupying German forces by the Polish Home ...

, but the request was denied by the Allies.

See also

*Polish Armed Forces in the East

The Polish Armed Forces in the East ( pl, Polskie Siły Zbrojne na Wschodzie), also called Polish Army in the USSR, were the Polish Armed Forces, Polish military forces established in the Soviet Union during World War II.

Two armies were formed ...

* Polish contribution to World War II

In World War Two, the Polish armed forces were the fourth largest Allied forces in Europe, after those of the Soviet Union, United States, and Britain. Poles made substantial contributions to the Allied effort throughout the war, fighting on lan ...

* Polish Armed Forces (Second Polish Republic)

Polish Armed Forces ( pl, Wojsko Polskie) were the armed forces of the Second Polish Republic from 1919 until the demise of independent Poland at the onset of Second World War in September 1939.

History

The outbreak of First World War meant that a ...

* Armia Ludowa

People's Army ( Polish: ''Armia Ludowa'' , abbriv.: AL) was a communist Soviet-backed partisan force set up by the communist Polish Workers' Party ('PR) during World War II. It was created on the order of the Polish State National Council on 1 ...

* Gwardia Ludowa

Gwardia Ludowa (; People's Guard) or GL was a communist underground armed organization created by the communist Polish Workers' Party in German occupied Poland, with sponsorship from the Soviet Union. Formed in early 1942, within a short time Gw ...

* First Polish Army (1944–1945)

The Polish First Army ( pl, Pierwsza Armia Wojska Polskiego, 1 AWP for short, also known as Berling's Army) was an army unit of the Polish Armed Forces in the East. It was formed in the Soviet Union in 1944, from the previously existing Polish I ...

* Polish People's Army

The Polish People's Army ( pl, Ludowe Wojsko Polskie , LWP) constituted the second formation of the Polish Armed Forces in the East in 1943–1945, and in 1945–1989 the armed forces of the Polish communist state ( from 1952, the Polish Pe ...

* Polish Combatants' Association (United States)

* Western betrayal

Western betrayal is the view that the United Kingdom, France, and sometimes the United States failed to meet their legal, diplomatic, military, and moral obligations with respect to the Czechoslovak and Polish states during the prelude to and ...

* Polish British

British Poles, alternatively known as Polish British people or Polish Britons, are ethnic Poles who are citizens of the United Kingdom. The term includes people born in the UK who are of Polish descent and Polish-born people who reside in the UK ...

* Civilian Labor Group

* Sikorski's tourists

* Bataliony Chłopskie

Bataliony Chłopskie (BCh, Polish ''Peasants' Battalions'') was a Polish World War II resistance movement, guerrilla and partisan organisation. The organisation was created in mid-1940 by the agrarian political party People's Party and by 19 ...

References

Bibliography

* Clare Mulley, ''The Spy Who Loved: The Secrets and Lives of Christine Granville, Britain's First Special Agent of World War II'', London, Macmillan, 2012, . *Michael Alfred Peszke

Michael Alfred Peszke (19 December 1932 – 17 May 2015) was a Polish-American psychiatrist and historian of the Polish Armed Forces in World War II.

Life

Peszke was born in Dęblin, Poland, in 1932. After the outbreak of World War II and the Naz ...

, ''Battle for Warsaw, 1939-1944'', Boulder, Colorado, East European Monographs, distributed by Columbia University Press, 1995, 325 pp., .

* Michael Alfred Peszke

Michael Alfred Peszke (19 December 1932 – 17 May 2015) was a Polish-American psychiatrist and historian of the Polish Armed Forces in World War II.

Life

Peszke was born in Dęblin, Poland, in 1932. After the outbreak of World War II and the Naz ...

, ''Poland's Navy, 1918-1945'', New York, Hippocrene Books, 1999, 222 pp., .

* Michael Alfred Peszke

Michael Alfred Peszke (19 December 1932 – 17 May 2015) was a Polish-American psychiatrist and historian of the Polish Armed Forces in World War II.

Life

Peszke was born in Dęblin, Poland, in 1932. After the outbreak of World War II and the Naz ...

, ''The Polish Underground Army, the Western Allies, and the Failure of Strategic Unity in World War II'', foreword by Piotr S. Wandycz, Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2005, 244 pp., .

* Michael Alfred Peszke

Michael Alfred Peszke (19 December 1932 – 17 May 2015) was a Polish-American psychiatrist and historian of the Polish Armed Forces in World War II.

Life

Peszke was born in Dęblin, Poland, in 1932. After the outbreak of World War II and the Naz ...

, "The Demise of the Polish Armed Forces in the West, 1945–1947," ''The Polish Review

''The Polish Review'' is an English-language academic journal published quarterly in New York City by the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America. ''The Polish Review'' was established in 1956.

Editors-in-chief

The following persons hav ...

'', vol. LV, no. 2, 2010, pp. 231–39.

* Michael Alfred Peszke

Michael Alfred Peszke (19 December 1932 – 17 May 2015) was a Polish-American psychiatrist and historian of the Polish Armed Forces in World War II.

Life

Peszke was born in Dęblin, Poland, in 1932. After the outbreak of World War II and the Naz ...

, review of Arkady Fiedler

Arkady Fiedler (28 November 1894 in Poznań – 7 March 1985 in Puszczykowo) was a Poles, Polish writer, journalist and adventurer.

Life

He studied philosophy and natural science at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków and later in Poznań and ...

, ''303 Squadron: The Legendary Battle of Britain Squadron'', translated by Jarek Garliński, Los Angeles, Aquila Polonica, 2010, , in ''The Polish Review

''The Polish Review'' is an English-language academic journal published quarterly in New York City by the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America. ''The Polish Review'' was established in 1956.

Editors-in-chief

The following persons hav ...

'', vol. LV, no. 4, 2010, pp. 467–68. Unique Identifier: 709924806.

* Michael Alfred Peszke

Michael Alfred Peszke (19 December 1932 – 17 May 2015) was a Polish-American psychiatrist and historian of the Polish Armed Forces in World War II.

Life

Peszke was born in Dęblin, Poland, in 1932. After the outbreak of World War II and the Naz ...

, "The British-Polish Agreement of August 1940: Its Antecedents, Significance and Consequences," ''Journal of Slavic Military Studies

''The Journal of Slavic Military Studies'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes articles relating to military affairs of Central and Eastern European Slavic nations, including their history and geopolitics, as well as boo ...

'' (print: ; online: ), Taylor & Francis Group

Taylor & Francis Group is an international company originating in England that publishes books and academic journals. Its parts include Taylor & Francis, Routledge, F1000 (publisher), F1000 Research or Dovepress. It is a division of Informa ...

, no. 24, 2011, pp. 648–58.

* Michael Alfred Peszke

Michael Alfred Peszke (19 December 1932 – 17 May 2015) was a Polish-American psychiatrist and historian of the Polish Armed Forces in World War II.

Life

Peszke was born in Dęblin, Poland, in 1932. After the outbreak of World War II and the Naz ...

, ''The Armed Forces of Poland in the West, 1939–46: Strategic Concepts, Planning, Limited Success but No Victory!'', Helion Studies in Military History, no. 13, Solihull

Solihull (, or ) is a market town and the administrative centre of the wider Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in West Midlands County, England. The town had a population of 126,577 at the 2021 Census. Solihull is situated on the River Blyth ...

, England, Helion & Company, Ltd, 2013, .

External links

Military contribution of Poland to World War II

Polish Ministry of Defence official page

Polish contribution to the Allied victory in World War 2 (1939-1945)

PDF at the site of Polish Embassy (Canada)

The Poles on the Fronts of WW2

Personnel of the Polish Air Force in Great Britain 1940-1947

Polish Exile Forces in the West in World War II

*

* Listen to Lynn Olsen & Stanley Cloud, authors of "A Question of Honor," speak about the "Kościuszko" Squadron and Polish contribution to World War I

here.

{{Authority control Military units and formations established in 1939 Military units and formations disestablished in 1947 Military units and formations of Poland in World War II Armies in exile during World War II