Platypus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a

When the platypus was first encountered by Europeans in 1798, a

When the platypus was first encountered by Europeans in 1798, a

In

In  Weight varies considerably from , with males being larger than females. Males average in total length, while females average , with substantial variation in average size from one region to another. This pattern does not seem to follow any particular climatic rule and may be due to other environmental factors, such as predation and human encroachment.

The platypus has an average

Weight varies considerably from , with males being larger than females. Males average in total length, while females average , with substantial variation in average size from one region to another. This pattern does not seem to follow any particular climatic rule and may be due to other environmental factors, such as predation and human encroachment.

The platypus has an average

While both male and female platypuses are born with ankle spurs, only the spurs on the male's back ankles deliver venom,

composed largely of

While both male and female platypuses are born with ankle spurs, only the spurs on the male's back ankles deliver venom,

composed largely of

The platypus is semiaquatic, inhabiting small streams and rivers over an extensive range from the cold highlands of

The platypus is semiaquatic, inhabiting small streams and rivers over an extensive range from the cold highlands of

When the platypus was first encountered by European naturalists, they were divided over whether the female lays eggs. This was finally confirmed by

When the platypus was first encountered by European naturalists, they were divided over whether the female lays eggs. This was finally confirmed by

The oldest discovered fossil of the modern platypus dates back to about 100,000 years ago, during the

The oldest discovered fossil of the modern platypus dates back to about 100,000 years ago, during the  Because of the early divergence from the

Because of the early divergence from the

Much of the world was introduced to the platypus in 1939 when ''

Much of the world was introduced to the platypus in 1939 when ''

The platypus has been a subject in the

The platypus has been a subject in the

Biodiversity Heritage Library bibliography

for ''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''

Platypus facts

* View th

platypus genome

in

semiaquatic

In biology, semiaquatic can refer to various types of animals that spend part of their time in water, or plants that naturally grow partially submerged in water. Examples are given below.

Semiaquatic animals

Semiaquatic animals include:

* Verte ...

, egg-laying mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

to eastern Australia

The eastern states of Australia are the states adjoining the east continental coastline of Australia. These are the mainland states of Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, and the island state of Tasmania. The Australian Capital Territory ...

, including Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

. The platypus is the sole living representative or monotypic taxon

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unispe ...

of its family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

(Ornithorhynchidae

The Ornithorhynchidae are one of the two extant families in the order Monotremata, and contain the platypus and its extinct relatives. The other family is the Tachyglossidae, or echidnas. Within the Ornithorhynchidae are the genera '' Monotrem ...

) and genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

(''Ornithorhynchus''), though a number of related species appear in the fossil record.

Together with the four species of echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the family Tachyglossidae . The four extant species of echidnas and the platypus are the only living mammals that lay eggs and the ...

, it is one of the five extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

species of monotreme

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals (Eutheria), and marsupials (Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their brain ...

s, mammals that lay eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

instead of giving birth to live young. Like other monotremes, it senses prey through electrolocation

Electroreception and electrogenesis are the closely-related biological abilities to perceive electrical stimuli and to generate electric fields. Both are used to locate prey; stronger electric discharges are used in a few groups of fishes to stu ...

. It is one of the few species of venomous mammals

Venomous mammals are animals of the class Mammalia that produce venom, which they use to kill or disable prey, to defend themselves from predators or conspecifics or in agonistic encounters. Mammalian venoms form a heterogeneous group with diffe ...

, as the male platypus has a spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse or other animal to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids (commands) and to back ...

on the hind foot that delivers a venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a sti ...

, capable of causing severe pain to humans. The unusual appearance of this egg-laying, duck

Duck is the common name for numerous species of waterfowl in the family Anatidae. Ducks are generally smaller and shorter-necked than swans and geese, which are members of the same family. Divided among several subfamilies, they are a form t ...

-billed, beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers ar ...

-tailed, otter

Otters are carnivorous mammals in the subfamily Lutrinae. The 13 extant otter species are all semiaquatic, aquatic, or marine, with diets based on fish and invertebrates. Lutrinae is a branch of the Mustelidae family, which also includes wea ...

-footed mammal baffled European naturalists when they first encountered it, and the first scientists to examine a preserved platypus body (in 1799) judged it a fake, made of several animals sewn together.

The unique features of the platypus make it an important subject in the study of evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life fo ...

, and a recognisable and iconic symbol of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

. It is culturally significant to several Aboriginal peoples of Australia, who also used to hunt the animal for food. It has appeared as a mascot at national events and features on the reverse

Reverse or reversing may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Reverse'' (Eldritch album), 2001

* ''Reverse'' (2009 film), a Polish comedy-drama film

* ''Reverse'' (2019 film), an Iranian crime-drama film

* ''Reverse'' (Morandi album), 2005

* ''Reverse'' ...

of the Australian twenty-cent coin

The Australian twenty-cent coin (Quinter) of the Australian decimal currency system was issued with conversion to Decimalisation, decimal currency on 14 February 1966, replacing the Florin (Australian coin), florin which was worth two shillings, ...

, and the platypus is the animal emblem of the state of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. Until the early 20th century, humans hunted the platypus for its fur, but it is now protected throughout its range. Although captive-breeding programs have had only limited success, and the platypus is vulnerable to the effects of pollution, it is not under any immediate threat.

, the platypus is a legally protected species

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and invas ...

in all states where it occurs. It is listed as an endangered species

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inv ...

in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

and vulnerable in Victoria. The species is classified as a near-threatened species

A near-threatened species is a species which has been categorized as "Near Threatened" (NT) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as that may be vulnerable to endangerment in the near future, but it does not currently qualify fo ...

by the IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

, but a November 2020 report has recommended that it is upgraded to threatened species

Threatened species are any species (including animals, plants and fungi) which are vulnerable to endangerment in the near future. Species that are threatened are sometimes characterised by the population dynamics measure of ''critical depensa ...

under the federal ''EPBC Act

The ''Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999'' (Cth) is an Act of the Parliament of Australia that provides a framework for protection of the Australian environment, including its biodiversity and its natural and cultu ...

'', due to habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

and declining numbers in all states.

Taxonomy and naming

When the platypus was first encountered by Europeans in 1798, a

When the platypus was first encountered by Europeans in 1798, a pelt

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

and sketch were sent back to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

by Captain John Hunter, the second Governor of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. British scientists' initial hunch was that the attributes were a hoax. George Shaw George Shaw may refer to:

* George Shaw (biologist) (1751–1813), English botanist and zoologist

* George B. Shaw (1854–1894), U.S. Representative from Wisconsin

* George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950), Irish playwright

* George C. Shaw (1866–196 ...

, who produced the first description of the animal in the ''Naturalist's Miscellany'' in 1799, stated it was impossible not to entertain doubts as to its genuine nature, and Robert Knox

Robert Knox (4 September 1791 – 20 December 1862) was a Scottish anatomist and ethnologist best known for his involvement in the Burke and Hare murders. Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, Knox eventually partnered with anatomist and former teache ...

believed it might have been produced by some Asian taxidermist

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body via mounting (over an armature) or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word ''taxidermy'' describes the proce ...

. It was thought that somebody had sewn a duck's beak onto the body of a beaver-like animal. Shaw even took a pair of scissors to the dried skin to check for stitches.

The common name "platypus" literally means 'flat-foot', deriving from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

word (), from ( 'broad, wide, flat') and ( 'foot'). Shaw initially assigned the species the Linnaean name ''Platypus anatinus'' when he described it, but the genus term was quickly discovered to already be in use as the name of the wood-boring ambrosia beetle

Ambrosia beetles are beetles of the weevil subfamilies Scolytinae and Platypodinae ( Coleoptera, Curculionidae), which live in nutritional symbiosis with ambrosia fungi. The beetles excavate tunnels in dead, stressed, and healthy trees in wh ...

genus ''Platypus

The platypus (''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''), sometimes referred to as the duck-billed platypus, is a semiaquatic, egg-laying mammal Endemic (ecology), endemic to Eastern states of Australia, eastern Australia, including Tasmania. The platypu ...

''. It was independently described as ''Ornithorhynchus paradoxus'' by Johann Blumenbach

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (11 May 1752 – 22 January 1840) was a German physician, naturalist, physiologist, and anthropologist. He is considered to be a main founder of zoology and anthropology as comparative, scientific disciplines. He wa ...

in 1800 (from a specimen given to him by Sir Joseph Banks

Sir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, (19 June 1820) was an English naturalist, botanist, and patron of the natural sciences.

Banks made his name on the 1766 natural-history expedition to Newfoundland and Labrador. He took part in Captain James C ...

) and following the rules of priority of nomenclature, it was later officially recognised as ''Ornithorhynchus anatinus''.

There is no universally-agreed plural form of "platypus" in the English language. Scientists generally use "platypuses" or simply "platypus". Colloquially, the term "platypi" is also used for the plural, although this is a form of pseudo-Latin; going by the word's Greek roots the plural would be "platypodes". Early British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

settler

A settler is a person who has human migration, migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a ...

s called it by many names, such as "watermole", "duckbill", and "duckmole". Occasionally it is specifically called the "duck-billed platypus".

The scientific name ''Ornithorhynchus anatinus'' literally means 'duck-like bird-snout', deriving its genus name

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

from the Greek root ( ''ornith'' or ''órnīs'' 'bird') and the word ( 'snout', 'beak'). Its species name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

is derived from Latin ('duck-like') from 'duck'. The platypus is the sole living representative or monotypic taxon

In biology, a monotypic taxon is a taxonomic group (taxon) that contains only one immediately subordinate taxon. A monotypic species is one that does not include subspecies or smaller, infraspecific taxa. In the case of genera, the term "unispe ...

of its family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

(Ornithorhynchidae

The Ornithorhynchidae are one of the two extant families in the order Monotremata, and contain the platypus and its extinct relatives. The other family is the Tachyglossidae, or echidnas. Within the Ornithorhynchidae are the genera '' Monotrem ...

).

Description

In

In David Collins David Collins may refer to:

Persons

* David Collins (Hampshire cricketer), 18th-century cricketer

* David Collins (New Zealand cricketer) (1887–1967)

* David Collins (Scottish footballer) (1912–?)

* David Collins (Australian footballer) ( ...

's account of the new colony 1788–1801, he describes coming across "an amphibious animal, of the mole species". His account includes a drawing of the animal.

The body and the broad, flat tail of the platypus are covered with dense, brown, biofluorescent fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

that traps a layer of insulating air to keep the animal warm. The fur is waterproof, and the texture is akin to that of a mole

Mole (or Molé) may refer to:

Animals

* Mole (animal) or "true mole", mammals in the family Talpidae, found in Eurasia and North America

* Golden moles, southern African mammals in the family Chrysochloridae, similar to but unrelated to Talpida ...

. The platypus uses its tail for storage of fat reserves (an adaptation also found in animals such as the Tasmanian devil

The Tasmanian devil (''Sarcophilus harrisii'') (palawa kani: purinina) is a carnivorous marsupial of the family Dasyuridae. Until recently, it was only found on the island state of Tasmania, but it has been reintroduced to New South Wales in ...

). The webbing on the feet is more significant on the front feet and is folded back when walking on land. The elongated snout and lower jaw are covered in soft skin, forming the bill. The nostrils are located on the dorsal surface of the snout, while the eyes and ears are located in a groove set just back from it; this groove is closed when swimming. Platypuses have been heard to emit a low growl when disturbed and a range of other vocalisations have been reported in captive specimens.

Weight varies considerably from , with males being larger than females. Males average in total length, while females average , with substantial variation in average size from one region to another. This pattern does not seem to follow any particular climatic rule and may be due to other environmental factors, such as predation and human encroachment.

The platypus has an average

Weight varies considerably from , with males being larger than females. Males average in total length, while females average , with substantial variation in average size from one region to another. This pattern does not seem to follow any particular climatic rule and may be due to other environmental factors, such as predation and human encroachment.

The platypus has an average body temperature

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

of about rather than the typical of placental mammals

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

. Research suggests this has been a gradual adaptation to harsh environmental conditions on the part of the small number of surviving monotreme species rather than a historical characteristic of monotremes.

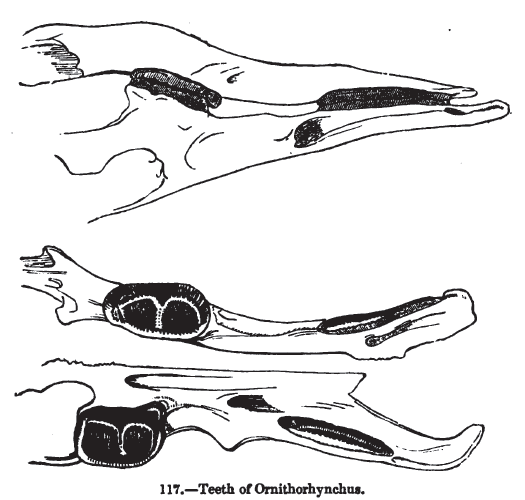

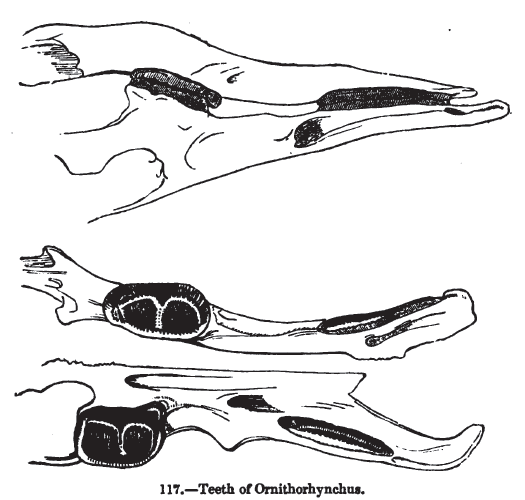

Modern platypus young have three teeth in each of the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The t ...

e (one premolar and two molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone to ...

) and dentaries

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

(three molars), which they lose before or just after leaving the breeding burrow; adults have heavily keratinised pads called ceratodontes in their place, which they use to grind food. The first upper and third lower cheek teeth of platypus nestlings are small, each having one principal cusp, while the other teeth have two main cusps. The platypus jaw

The jaw is any opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term ''jaws'' is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serv ...

is constructed differently from that of other mammals, and the jaw-opening muscle is different. As in all true mammals, the tiny bones that conduct sound in the middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles, which transfer the vibrations of the eardrum into waves in the ...

are fully incorporated into the skull, rather than lying in the jaw as in pre mammalian synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

s. However, the external opening of the ear still lies at the base of the jaw. The platypus has extra bones in the shoulder girdle, including an interclavicle

An interclavicle is a bone which, in most tetrapods, is located between the clavicles. Therian mammals ( marsupials and placentals) are the only tetrapods which never have an interclavicle, although some members of other groups also lack one. In th ...

, which is not found in other mammals. As in many other aquatic and semiaquatic vertebrates

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

, the bones show osteosclerosis

Osteosclerosis is a disorder that is characterized by abnormal hardening of bone and an elevation in bone density. It may predominantly affect the medullary portion and/or cortex of bone. Plain radiographs are a valuable tool for detecting and ...

, increasing their density to provide ballast. It has a reptilian gait, with the legs on the sides of the body, rather than underneath. When on land, it engages in knuckle-walking

Knuckle-walking is a form of quadrupedal walking in which the forelimbs hold the fingers in a partially flexed posture that allows body weight to press down on the ground through the knuckles. Gorillas, bonobos, and chimpanzees use this style o ...

on its front feet, to protect the webbing between the toes.

Venom

defensin

Defensins are small cysteine-rich cationic proteins across cellular life, including vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, ...

-like protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s (DLPs), three of which are unique to the platypus. The DLPs are produced by the immune system of the platypus. The function of defensins is to cause lysis

Lysis ( ) is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ''lysate''. In molecular bio ...

in pathogenic bacteria and viruses, but in platypuses they also are formed into venom for defence. Although powerful enough to kill smaller animals such as dogs, the venom is not lethal to humans, but the pain is so excruciating that the victim may be incapacitated. Oedema

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels tight, the area ma ...

rapidly develops around the wound and gradually spreads throughout the affected limb. Information obtained from case histories

''Case Histories'' (2004) is a detective novel by British author Kate Atkinson and is set in Cambridge, England. It introduces Jackson Brodie, a former police inspector and now private investigator. The plot revolves around three seemingly unc ...

and anecdotal evidence indicates the pain develops into a long-lasting hyperalgesia

Hyperalgesia ( or ; 'hyper' from Greek ὑπέρ (huper, “over”), '-algesia' from Greek algos, ἄλγος (pain)) is an abnormally increased sensitivity to pain, which may be caused by damage to nociceptors or peripheral nerves and can ...

(a heightened sensitivity to pain) that persists for days or even months. Venom is produced in the crural glands of the male, which are kidney-shaped alveolar gland

Alveolar glands, also called saccular glands are glands with a saclike secretory portion, in conrast with tubular glands. They typically have an enlarged lumen (cavity), hence the name: they have a shape similar to alveoli, the very small air ...

s connected by a thin-walled duct to a calcaneus

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel) or heel bone is a bone of the tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other animals, it is the point of the hock.

S ...

spur on each hind limb. The female platypus, in common with echidnas, has rudimentary spur buds that do not develop (dropping off before the end of their first year) and lack functional crural glands.

The venom appears to have a different function from those produced by non-mammalian species; its effects are not life-threatening to humans, but nevertheless powerful enough to seriously impair the victim. Since only males produce venom and production rises during the breeding season, it may be used as an offensive weapon to assert dominance during this period.

Similar spurs are found on many archaic mammal groups, indicating that this is an ancient characteristic for mammals as a whole, and not exclusive to the platypus or other monotremes.

Electrolocation

Monotremes

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals (Eutheria), and marsupials ( Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their br ...

are the only mammals (apart from at least one species of dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

-- the Guiana Dolphin) known to have a sense of electroreception

Electroreception and electrogenesis are the closely-related biological abilities to perceive electrical stimuli and to generate electric fields. Both are used to locate prey; stronger electric discharges are used in a few groups of fishes to stu ...

: they locate their prey in part by detecting electric fields generated by muscular contractions. The platypus's electroreception is the most sensitive of any monotreme.

The electroreceptor

Electroreception and electrogenesis are the closely-related biological abilities to perceive electrical stimuli and to generate electric fields. Both are used to locate prey; stronger electric discharges are used in a few groups of fishes to stu ...

s are located in rostrocaudal rows in the skin of the bill, while mechanoreceptor

A mechanoreceptor, also called mechanoceptor, is a sensory receptor that responds to mechanical pressure or distortion. Mechanoreceptors are innervated by sensory neurons that convert mechanical pressure into electrical signals that, in animals, ...

s (which detect touch) are uniformly distributed across the bill. The electrosensory area of the cerebral cortex

The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. The cerebral cortex mostly consists of the six-layered neocortex, with just 10% consisting of ...

is contained within the tactile somatosensory

In physiology, the somatosensory system is the network of neural structures in the brain and body that produce the perception of touch (haptic perception), as well as temperature (thermoception), body position (proprioception), and pain. It i ...

area, and some cortical cells receive input from both electroreceptors and mechanoreceptors, suggesting a close association between the tactile and electric senses. Both electroreceptors and mechanoreceptors in the bill dominate the somatotopic map

Somatotopy is the point-for-point correspondence of an area of the body to a specific point on the central nervous system. Typically, the area of the body corresponds to a point on the primary somatosensory cortex ( postcentral gyrus). This cortex ...

of the platypus brain, in the same way human hands dominate the Penfield homunculus map.

The platypus can determine the direction of an electric source, perhaps by comparing differences in signal strength

In telecommunications, particularly in radio frequency engineering, signal strength refers to the transmitter power output as received by a reference antenna at a distance from the transmitting antenna. High-powered transmissions, such as those us ...

across the sheet of electroreceptors. This would explain the characteristic side-to-side motion of the animal's head while hunting. The cortical convergence of electrosensory and tactile inputs suggests a mechanism that determines the distance of prey that, when they move, emit both electrical signals and mechanical pressure pulses. The platypus uses the difference between arrival times of the two signals to sense distance.

Feeding by neither sight nor smell, the platypus closes its eyes, ears, and nose each time it dives. Rather, when it digs in the bottom of streams with its bill, its electroreceptors detect tiny electric currents generated by muscular contractions of its prey, so enabling it to distinguish between animate and inanimate objects, which continuously stimulate its mechanoreceptors. Experiments have shown the platypus will even react to an "artificial shrimp" if a small electric current is passed through it.

Monotreme electrolocation probably evolved in order to allow the animals to forage in murky waters, and may be tied to their tooth loss.Masakazu Asahara; Masahiro Koizumi; Thomas E. Macrini; Suzanne J. Hand; Michael Archer (2016). "Comparative cranial morphology in living and extinct platypuses: Feeding behavior, electroreception, and loss of teeth". Science Advances. 2 (10): e1601329. . The extinct ''Obdurodon

''Obdurodon'' is a genus of extinct platypus-like Australian monotreme which lived from the Late Oligocene to the Late Miocene. Three species have been described in the genus, the type species ''Obdurodon insignis'', plus ''Obdurodon dicksoni'' ...

'' was electroreceptive, but unlike the modern platypus it foraged pelagically (near the ocean surface).

Eyes

In recent studies it has been suggested that the eyes of the platypus are more similar to those ofPacific hagfish

The Pacific hagfish (''Eptatretus stoutii'') is a species of hagfish. It lives in the mesopelagic to abyssal zone, abyssal Pacific ocean, near the ocean floor. It is a Agnatha, jawless fish and has a body plan that resembles early Paleozoic Era, ...

or Northern Hemisphere lamprey

Lampreys (sometimes inaccurately called lamprey eels) are an ancient extant lineage of jawless fish of the order Petromyzontiformes , placed in the superclass Cyclostomata. The adult lamprey may be characterized by a toothed, funnel-like s ...

s than to those of most tetrapods. The eyes also contain double cones, which most mammals do not have.

Although the platypus's eyes are small and not used under water, several features indicate that vision played an important role in its ancestors. The cornea

The cornea is the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber. Along with the anterior chamber and lens, the cornea refracts light, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the eye's total optical power ...

l surface and the adjacent surface of the lens is flat while the posterior surface of the lens is steeply curved, similar to the eyes of other aquatic mammals such as otters and sea-lions. A temporal (ear side) concentration of retinal ganglion cell

A retinal ganglion cell (RGC) is a type of neuron located near the inner surface (the ganglion cell layer) of the retina of the human eye, eye. It receives visual information from photoreceptor cell, photoreceptors via two intermediate neuron typ ...

s, important for binocular vision, indicates a role in predation

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

, while the accompanying visual acuity is insufficient for such activities. Furthermore, this limited acuity is matched by a low cortical magnification Cortical magnification describes how many neurons in an area of the visual cortex are 'responsible' for processing a stimulus of a given size, as a function of visual field location. In the center of the visual field, corresponding to the center of ...

, a small lateral geniculate nucleus

In neuroanatomy, the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN; also called the lateral geniculate body or lateral geniculate complex) is a structure in the thalamus and a key component of the mammalian visual pathway. It is a small, ovoid, ventral projec ...

and a large optic tectum

In neuroanatomy, the superior colliculus () is a structure lying on the roof of the mammalian midbrain. In non-mammalian vertebrates, the homologous structure is known as the optic tectum, or optic lobe. The adjective form ''tectal'' is commonly ...

, suggesting that the visual midbrain plays a more important role than the visual cortex

The visual cortex of the brain is the area of the cerebral cortex that processes visual information. It is located in the occipital lobe. Sensory input originating from the eyes travels through the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus and ...

, as in some rodents. These features suggest that the platypus has adapted to an aquatic and nocturnal lifestyle, developing its electrosensory system at the cost of its visual system; an evolutionary process paralleled by the small number of electroreceptors in the short-beaked echidna

The short-beaked echidna (''Tachyglossus aculeatus''), also called the short-nosed echidna, is one of four living species of echidna and the only member of the genus ''Tachyglossus''. It is covered in fur and spines and has a distinctive snou ...

, which dwells in dry environments, whilst the long-beaked echidna

The long-beaked echidnas (genus ''Zaglossus'') make up one of the two extant genera of echidnas, spiny monotremes that live in New Guinea; the other being the short-beaked echidna. There are three living species and one extinct species in this ge ...

, which lives in moist environments, is intermediate between the other two monotremes.

Biofluorescence

In 2020, research in biofluorescence revealed that the platypus glows a bluish-green color when exposed toblack light

A blacklight, also called a UV-A light, Wood's lamp, or ultraviolet light, is a lamp that emits long-wave (UV-A) ultraviolet light and very little visible light. One type of lamp has a violet filter material, either on the bulb or in a separat ...

.

Distribution, ecology, and behaviour

The platypus is semiaquatic, inhabiting small streams and rivers over an extensive range from the cold highlands of

The platypus is semiaquatic, inhabiting small streams and rivers over an extensive range from the cold highlands of Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

and the Australian Alps

The Australian Alps is a mountain range in southeast Australia. It comprises an interim Australian bioregion,

to the tropical rainforest

Tropical rainforests are rainforests that occur in areas of tropical rainforest climate in which there is no dry season – all months have an average precipitation of at least 60 mm – and may also be referred to as ''lowland equatori ...

s of coastal Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

as far north as the base of the Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large peninsula located in Far North Queensland, Australia. It is the largest unspoiled wilderness in northern Australia.Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth’s last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupación ...

.

Inland, its distribution is not well known. It was considered extinct on the South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

n mainland, with the last sighting recorded at Renmark in 1975, until some years after John Wamsley

Dr John Wamsley (born 1938) is an Australian environmentalist. He was the Prime Minister's Environmentalist of the Year for 2003. Wamsley is known for his attempt to set up a network of wildlife sanctuaries across Australia.

Wamsley was born ...

had created Warrawong Sanctuary (see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

) in the 1980s, setting a platypus breeding program there, and it had subsequently closed. In 2017 there were some unconfirmed sightings downstream, outside the sanctuary, and in October 2020 a nesting platypus was filmed inside the recently reopened sanctuary. There is a population on Kangaroo Island

Kangaroo Island, also known as Karta Pintingga (literally 'Island of the Dead' in the language of the Kaurna people), is Australia's third-largest island, after Tasmania and Melville Island. It lies in the state of South Australia, southwest ...

introduced in the 1920s, which was said to stand at 150 individuals in the Rocky River region of Flinders Chase National Park

Flinders Chase National Park (formerly Flinders Chase) is a protected area in the Australian state of South Australia located at the west end of Kangaroo Island about west-south west of the state capital of Adelaide and west of the municipal ...

before the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season

The 201920 Australian bushfire season (Black Summer), was a period of bushfires in many parts of Australia, which, due to its unusual intensity, size, duration, and uncontrollable dimension, is considered a megafire. The Australian National ...

, in which large portions of the island burnt, decimating all wildlife. However, with the SA Department for Environment and Water recovery teams working hard to reinstate their habitat, there had been a number of sightings reported by April 2020.

The platypus is no longer found in the main part of the Murray-Darling Basin, possibly due to the declining water quality

Water quality refers to the chemical, physical, and biological characteristics of water based on the standards of its usage. It is most frequently used by reference to a set of standards against which compliance, generally achieved through tr ...

brought about by extensive land clearing and irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

schemes. Along the coastal river systems, its distribution is unpredictable; it appears to be absent from some relatively healthy rivers, and yet maintains a presence in others, for example, the lower Maribyrnong, that are quite degraded.

In captivity, platypuses have survived to 17 years of age, and wild specimens have been recaptured when 11 years old. Mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of de ...

s for adults in the wild appear to be low. Natural predators include snake

Snakes are elongated, Limbless vertebrate, limbless, carnivore, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other Squamata, squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping Scale (zoology), scales. Ma ...

s, water rats, goanna

A goanna is any one of several species of lizards of the genus '' Varanus'' found in Australia and Southeast Asia.

Around 70 species of ''Varanus'' are known, 25 of which are found in Australia. This varied group of carnivorous reptiles ranges ...

s, hawk

Hawks are bird of prey, birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are widely distributed and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

* The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks and others. Th ...

s, owl

Owls are birds from the order Strigiformes (), which includes over 200 species of mostly solitary and nocturnal birds of prey typified by an upright stance, a large, broad head, binocular vision, binaural hearing, sharp talons, and feathers a ...

s, and eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just ...

s. Low platypus numbers in northern Australia are possibly due to predation by crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to inclu ...

s. The introduction of red fox

The red fox (''Vulpes vulpes'') is the largest of the true foxes and one of the most widely distributed members of the Order (biology), order Carnivora, being present across the entire Northern Hemisphere including most of North America, Europe ...

es in 1845 for hunting may have had some impact on its numbers on the mainland. The platypus is generally regarded as nocturnal

Nocturnality is an animal behavior characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatures generally have highly developed sens ...

and crepuscular

In zoology, a crepuscular animal is one that is active primarily during the twilight period, being matutinal, vespertine, or both. This is distinguished from diurnal and nocturnal behavior, where an animal is active during the hours of daylig ...

, but individuals are also active during the day, particularly when the sky is overcast. Its habitat bridges river

A river is a natural flowing watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, sea, lake or another river. In some cases, a river flows into the ground and becomes dry at the end of its course without reaching another body of wate ...

s and the riparian zone

A riparian zone or riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream. Riparian is also the proper nomenclature for one of the terrestrial biomes of the Earth. Plant habitats and communities along the river margins and banks ar ...

for both a food supply of prey species, and banks where it can dig resting and nesting burrows. It may have a range of up to , with a male's home range overlapping those of three or four females.

The platypus is an excellent swimmer and spends much of its time in the water foraging for food. It has a very characteristic swimming style and no external ears. Uniquely among mammals, it propels itself when swimming by an alternate rowing motion of the front feet; although all four feet of the platypus are webbed, the hind feet (which are held against the body) do not assist in propulsion, but are used for steering in combination with the tail. The species is endothermic

In thermochemistry, an endothermic process () is any thermodynamic process with an increase in the enthalpy (or internal energy ) of the system.Oxtoby, D. W; Gillis, H.P., Butler, L. J. (2015).''Principle of Modern Chemistry'', Brooks Cole. p. ...

, maintaining its body temperature at about 32°C (90°F), lower than most mammals, even while foraging for hours in water below 5°C (41°F).

Dives normally last around 30 seconds, but can last longer, although few exceed the estimated aerobic limit of 40 seconds. Recovery at the surface between dives commonly takes from 10 to 20 seconds.

When not in the water, the platypus retires to a short, straight resting burrow of oval cross-section, nearly always in the riverbank not far above water level, and often hidden under a protective tangle of roots.

The average sleep time of a platypus is said to be as long as 14 hours per day, possibly because it eats crustaceans

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

, which provide a high level of calories.

Diet

The platypus is acarnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

: it feeds on annelid

The annelids (Annelida , from Latin ', "little ring"), also known as the segmented worms, are a large phylum, with over 22,000 extant species including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to various ecol ...

worms, insect larvae, freshwater shrimp

Shrimp are crustaceans (a form of shellfish) with elongated bodies and a primarily swimming mode of locomotion – most commonly Caridea and Dendrobranchiata of the decapod order, although some crustaceans outside of this order are refer ...

, and freshwater yabby

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the clade Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. In some locations, they are also known as crawfish, craydids, crawdaddies, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mountain lobsters, rock lobsters, m ...

(crayfish

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the clade Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. In some locations, they are also known as crawfish, craydids, crawdaddies, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mountain lobsters, rock lobsters, mu ...

) that it digs out of the riverbed with its snout or catches while swimming. It uses cheek-pouches to carry prey to the surface, where it is eaten. The platypus needs to eat about 20% of its own weight each day, which requires it to spend an average of 12 hours daily looking for food.

Reproduction

William Hay Caldwell

William Hay Caldwell (1859 – 28 August 1941) was a Scottish zoologist. Attending Cambridge University, he was the first recipient of a studentship founded in honour of his supervisor Francis Maitland Balfour, who died in a climbing accident in ...

's team in 1884.

The species exhibits a single breeding season

Seasonal breeders are animal species that successfully mate only during certain times of the year. These times of year allow for the optimization of survival of young due to factors such as ambient temperature, food and water availability, and cha ...

; mating occurs between June and October, with some local variation taking place between different populations across its range. Historical observation, mark-and-recapture studies, and preliminary investigations of population genetics indicate the possibility of both resident and transient members of populations, and suggest a polygynous

Polygyny (; from Neoclassical Greek πολυγυνία (); ) is the most common and accepted form of polygamy around the world, entailing the marriage of a man with several women.

Incidence

Polygyny is more widespread in Africa than in any ...

mating system. Females are thought likely to become sexually mature in their second year, with breeding confirmed still to take place in animals over nine years old.

Outside the mating season, the platypus lives in a simple ground burrow, the entrance of which is about above the water level. After mating, the female constructs a deeper, more elaborate burrow up to long and blocked at intervals with plugs (which may act as a safeguard against rising waters or predators, or as a method of regulating humidity and temperature). The male takes no part in caring for his young, and retreats to his year-long burrow. The female softens the ground in the burrow with dead, folded, wet leaves, and she fills the nest at the end of the tunnel with fallen leaves and reeds for bedding material. This material is dragged to the nest by tucking it underneath her curled tail.

The female platypus has a pair of ovaries

The ovary is an organ in the female reproductive system that produces an ovum. When released, this travels down the fallopian tube into the uterus, where it may become fertilized by a sperm. There is an ovary () found on each side of the body. T ...

, but only the left one is functional. The platypus's genes are a possible evolutionary link between the mammalian XY and bird/reptile ZW sex-determination systems because one of the platypus's five X chromosomes contains the DMRT1

Doublesex and mab-3 related transcription factor 1, also known as DMRT1, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the ''DMRT1'' gene.

Function

DMRT1 is a dose sensitive transcription factor protein that regulates Sertoli cells and germ cells ...

gene, which birds possess on their Z chromosome. It lays one to three (usually two) small, leathery eggs (similar to those of reptiles), about in diameter and slightly rounder than bird eggs. The eggs develop ''in utero

''In Utero'' is the third and final studio album by American rock band Nirvana. It was released on September 21, 1993, by DGC Records. After breaking into the mainstream with their second album, ''Nevermind'' (1991), Nirvana hired Steve Albini t ...

'' for about 28 days, with only about 10 days of external incubation (in contrast to a chicken egg, which spends about one day in tract and 21 days externally). After laying her eggs, the female curls around them. The incubation period is divided into three phases. In the first phase, the embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

has no functional organs and relies on the yolk sac

The yolk sac is a membranous sac attached to an embryo, formed by cells of the hypoblast layer of the bilaminar embryonic disc. This is alternatively called the umbilical vesicle by the Terminologia Embryologica (TE), though ''yolk sac'' is far ...

for sustenance. The yolk is absorbed by the developing young. During the second phase, the digits develop, and in the last phase, the egg tooth

An egg tooth is a temporary, sharp projection present on the bill or snout of an oviparous animal at hatching. It allows the hatchling to penetrate the eggshell from inside and break free. Birds, reptiles, and monotremes possess egg teeth as h ...

appears.

Most mammal zygotes go through holoblastic

In embryology, cleavage is the division of cells in the early development of the embryo, following fertilization. The zygotes of many species undergo rapid cell cycles with no significant overall growth, producing a cluster of cells the same size ...

cleavage, meaning that, following fertilization, the ovum is split due to cell divisions into multiple, divisible daughter cells. This is in comparison to the more ancestral process of meroblastic

In embryology, cleavage is the division of cells in the early development of the embryo, following fertilization. The zygotes of many species undergo rapid cell cycles with no significant overall growth, producing a cluster of cells the same siz ...

cleavage, present in monotremes

Monotremes () are prototherian mammals of the order Monotremata. They are one of the three groups of living mammals, along with placentals (Eutheria), and marsupials ( Metatheria). Monotremes are typified by structural differences in their br ...

like the platypus and in non-mammals like reptiles and birds. In meroblastic cleavage, the ovum does not split completely. This causes the cells at the edge of the yolk to be cytoplasmically continuous with the egg's cytoplasm. This allows the yolk, which contains the embryo, to exchange waste and nutrients with the cytoplasm.

There is no official term for platypus young, but the term "platypup" sees unofficial use, as does "puggle". Newly hatched platypuses are vulnerable, blind, and hairless, and are fed by the mother's milk. Although possessing mammary gland

A mammary gland is an exocrine gland in humans and other mammals that produces milk to feed young offspring. Mammals get their name from the Latin word ''mamma'', "breast". The mammary glands are arranged in organs such as the breasts in primat ...

s, the platypus lacks teats. Instead, milk is released through pores in the skin. The milk pools in grooves on her abdomen, allowing the young to lap it up. After they hatch, the offspring are suckled for three to four months. During incubation and weaning, the mother initially leaves the burrow only for short periods, to forage. When doing so, she creates a number of thin soil plugs along the length of the burrow, possibly to protect the young from predators; pushing past these on her return forces water from her fur and allows the burrow to remain dry. After about five weeks, the mother begins to spend more time away from her young, and at around four months, the young emerge from the burrow. A platypus is born with teeth, but these drop out at a very early age, leaving the horny plates it uses to grind food.

Evolution

The platypus and other monotremes were very poorly understood, and some of the 19th century myths that grew up around themfor example, that the monotremes were "inferior" or quasireptilianstill endure. In 1947,William King Gregory

William King Gregory (May 19, 1876 – December 29, 1970) was an American zoologist, renowned as a primatologist, paleontologist, and functional and comparative anatomist. He was an expert on mammalian dentition, and a leading contributor t ...

theorised that placental mammals and marsupials may have diverged earlier, and a subsequent branching divided the monotremes and marsupials, but later research and fossil discoveries have suggested this is incorrect. In fact, modern monotremes are the survivors of an early branching of the mammal tree, and a later branching is thought to have led to the marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in a po ...

and placental groups. Molecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleoti ...

and fossil dating suggest platypuses split from echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the family Tachyglossidae . The four extant species of echidnas and the platypus are the only living mammals that lay eggs and the ...

s around 19–48million years ago.

The oldest discovered fossil of the modern platypus dates back to about 100,000 years ago, during the

The oldest discovered fossil of the modern platypus dates back to about 100,000 years ago, during the Quaternary

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million years ...

period. The extinct monotremes ''Teinolophos

''Teinolophos'' is a prehistoric species of monotreme, or egg-laying mammal, from the Teinolophidae. It is known from four specimens, each consisting of a partial lower jawbone collected from the Wonthaggi Formation at Flat Rocks, Victoria, Aus ...

'' and ''Steropodon

''Steropodon'' is a genus of prehistoric monotreme, or egg-laying mammal. It contains a single species, ''Steropodon galmani'', that lived about 105 to 93.3 million years ago (mya) in the Early to Late Cretaceous period. It is one of the oldest m ...

'' were once thought to be closely related to the modern platypus, but are now considered more basal taxa. The fossilised ''Steropodon'' was discovered in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

and is composed of an opalised lower jawbone with three molar teeth (whereas the adult contemporary platypus is toothless). The molar teeth were initially thought to be tribosphenic, which would have supported a variation of Gregory's theory, but later research has suggested, while they have three cusps, they evolved under a separate process. The fossil is thought to be about 110million years old, making it the oldest mammal fossil found in Australia. Unlike the modern platypus (and echidna

Echidnas (), sometimes known as spiny anteaters, are quill-covered monotremes (egg-laying mammals) belonging to the family Tachyglossidae . The four extant species of echidnas and the platypus are the only living mammals that lay eggs and the ...

s), ''Teinolophos'' lacked a beak.

'' Monotrematum sudamericanum'', another fossil relative of the platypus, has been found in Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, indicating monotremes were present in the supercontinent of Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final stages ...

when the continents of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

and Australia were joined via Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest contine ...

(until about 167million years ago). A fossilised tooth of a giant platypus species, ''Obdurodon tharalkooschild

''Obdurodon'' is a genus of extinct platypus-like Australian monotreme which lived from the Late Oligocene to the Late Miocene. Three species have been described in the genus, the type species ''Obdurodon insignis'', plus ''Obdurodon dicksoni'' ...

'', was dated 5–15million years ago. Judging by the tooth, the animal measured 1.3 metres long, making it the largest platypus on record.

Because of the early divergence from the

Because of the early divergence from the therian mammals

Theria (; Greek: , wild beast) is a subclass of mammals amongst the Theriiformes. Theria includes the eutherians (including the placental mammals) and the metatherians (including the marsupials) but excludes the egg-laying monotremes.

...

and the low numbers of extant monotreme species, the platypus is a frequent subject of research in evolutionary biology. In 2004, research

Research is "creativity, creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge". It involves the collection, organization and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular att ...

ers at the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

discovered the platypus has ten sex chromosome

A sex chromosome (also referred to as an allosome, heterotypical chromosome, gonosome, heterochromosome, or idiochromosome) is a chromosome that differs from an ordinary autosome in form, size, and behavior. The human sex chromosomes, a typical ...

s, compared with two (XY) in most other mammals. These ten chromosomes form five unique pairs of XY in males and XX in females, i.e. males are XYXYXYXYXY. One of the X chromosomes of the platypus has great homology to the bird Z chromosome. The platypus genome also has both reptilian and mammalian genes associated with egg fertilisation. Though the platypus lacks the mammalian sex-determining gene SRY, a study found that the mechanism of sex determination is the AMH gene on the oldest Y chromosome

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes (allosomes) in therian mammals, including humans, and many other animals. The other is the X chromosome. Y is normally the sex-determining chromosome in many species, since it is the presence or abse ...

. A draft version of the platypus genome sequence was published in ''Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

'' on 8May 2008, revealing both reptilian and mammalian elements, as well as two genes found previously only in birds, amphibians, and fish. More than 80% of the platypus's genes are common to the other mammals whose genomes have been sequenced. An updated genome, the most complete on record, was published in 2021, together with the genome of the short-beaked echidna

The short-beaked echidna (''Tachyglossus aculeatus''), also called the short-nosed echidna, is one of four living species of echidna and the only member of the genus ''Tachyglossus''. It is covered in fur and spines and has a distinctive snou ...

.

Conservation

Status and threats

Except for its loss from the state of South Australia, the platypus occupies the same general distribution as it did prior toEuropean settlement of Australia

European, or Europeans, or Europeneans, may refer to:

In general

* ''European'', an adjective referring to something of, from, or related to Europe

** Ethnic groups in Europe

** Demographics of Europe

** European cuisine, the cuisines of Europe ...

. However, local changes and fragmentation of distribution due to human modification of its habitat are documented. Its historical abundance is unknown and its current abundance difficult to gauge, but it is assumed to have declined in numbers, although as of 1998 was still being considered as common over most of its current range. The species was extensively hunted for its fur until the early years of the 20th century and, although protected throughout Australia since 1905, until about 1950 it was still at risk of drowning in the nets of inland fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life; or more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a. fishing ground). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farms, both ...

.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

recategorised its status as "near threatened" in 2016. The species is protected by law, but the only state in which it is listed as endangered is South Australia, under the ''National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972

Protected areas of South Australia consists of protected areas located within South Australia and its immediate onshore waters and which are managed by South Australian Government agencies. As of March 2018, South Australia contains 359 sepa ...

''. In 2020 it has been recommended to be listed as a vulnerable species in Victoria under the state's ''Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988

The ''Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988'', also known as the ''FFG Act'', is an act of the Victorian Government designed to protect species, genetic material and habitats, to prevent extinction and allow maximum genetic diversity within the Au ...

''.

Habitat destruction

The platypus is not considered to be in immediate danger of extinction, because conservation measures have been successful, but it could be adversely affected by habitat disruption caused bydam

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use ...

s, irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

, pollution

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into the natural environment that cause adverse change. Pollution can take the form of any substance (solid, liquid, or gas) or energy (such as radioactivity, heat, sound, or light). Pollutants, the ...

, netting, and trapping. Reduction of watercourse flows and water levels through excessive droughts and extraction of water for industrial, agricultural, and domestic supplies are also considered a threat. The IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

lists the platypus on its Red List

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, also known as the IUCN Red List or Red Data Book, founded in 1964, is the world's most comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status of biologi ...

as "Near Threatened

A near-threatened species is a species which has been categorized as "Near Threatened" (NT) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as that may be vulnerable to endangerment in the near future, but it does not currently qualify fo ...

" as assessed in 2016, when it was estimated that numbers had reduced by about 30 percent on average since European settlement. The animal is listed as endangered in South Australia, but it is not covered at all under the federal ''EPBC Act

The ''Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999'' (Cth) is an Act of the Parliament of Australia that provides a framework for protection of the Australian environment, including its biodiversity and its natural and cultu ...

''.

Researchers have worried for years that declines have been greater than assumed. In January 2020, researchers from the University of New South Wales

The University of New South Wales (UNSW), also known as UNSW Sydney, is a public research university based in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It is one of the founding members of Group of Eight, a coalition of Australian research-intensive ...

presented evidence that the platypus is at risk of extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

, due to a combination of extraction of water resource

Water resources are natural resources of water that are potentially useful for humans, for example as a source of drinking water supply or irrigation water. 97% of the water on the Earth is salt water and only three percent is fresh water; slightl ...

s, land clearing

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated d ...

, climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

and severe drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

. The study predicted that, considering current threats, the animals' abundance would decline by 47%–66% and metapopulation

A metapopulation consists of a group of spatially separated populations of the same species which interact at some level. The term metapopulation was coined by Richard Levins in 1969 to describe a model of population dynamics of insect pests in ...

occupancy by 22%–32% over 50 years, causing "extinction of local populations across about 40% of the range". Under projections of climate change projections to 2070, reduced habitat due to drought would lead to 51–73% reduced abundance and 36–56% reduced metapopulation occupancy within 50 years respectively. These predictions suggested that the species would fall under the "Vulnerable" classification. The authors stressed the need for national conservation efforts, which might include conducting more surveys, tracking trends, reduction of threats and improvement of river management to ensure healthy platypus habitat. Co-author Gilad Bino is concerned that the estimates of the 2016 baseline numbers could be wrong, and numbers may have been reduced by as much as half already.

A November 2020 report by scientists from the University of New South Wales

The University of New South Wales (UNSW), also known as UNSW Sydney, is a public research university based in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It is one of the founding members of Group of Eight, a coalition of Australian research-intensive ...

, funded by a research grant from the Australian Conservation Foundation

The Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) is Australia's national environmental organisation, launched in 1965 in response to a proposal by the World Wide Fund for Nature for a more co-ordinated approach to sustainability.

One high-profil ...

in collaboration with the World Wildlife Fund Australia and the Humane Society International Australia

Humane Society International Australia (HSIA) is the Australian branch of Humane Society International (HSI), an offshoot of the international animal protection organisation, The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS).

History

Humane So ...

revealed that that platypus habitat in Australia had shrunk by 22 per cent in the previous 30 years, and recommended that the platypus should be listed as a threatened species under the ''EPBC Act''. Declines in population had been greatest in NSW, in particular in the Murray-Darling Basin.

Disease

Platypuses generally suffer from fewdisease