The persecution of Muslims has been recorded throughout the

history of Islam

The history of Islam concerns the political, social, economic, military, and cultural developments of the Islamic civilization. Most historians believe that Islam originated in Mecca and Medina at the start of the 7th century CE. Muslims ...

, beginning with its founding by

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

in the 7th century.

In the early days of

Islam in

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

,

pre-Islamic Arabia

Pre-Islamic Arabia ( ar, شبه الجزيرة العربية قبل الإسلام) refers to the Arabian Peninsula before the emergence of Islam in 610 CE.

Some of the settled communities developed into distinctive civilizations. Information ...

, the new

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abra ...

were often subjected to abuse and

persecution by the Meccans (also called

Mushrikun

''Shirk'' ( ar, شرك ''širk'') in Islam is the sin of idolatry or polytheism (''i.e.'', the deification or worship of anyone or anything besides Allah). Islam teaches that God does not share his divine attributes with any partner. Associatin ...

by Muslims), a

polytheistic Arab tribal confederation. In the contemporary period, Muslims have faced religious restrictions in some countries.

Various incidents of Islamophobia have also occurred, such as the

Christchurch mosque shootings

On 15 March 2019, two consecutive mass shootings occurred in a terrorist attack on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand. The attacks, carried out by a lone gunman who entered both mosques during Friday prayer, began at the Al Noor Mosq ...

. Some global conflicts have seen religiously and/or politically motivated belligerents persecute the Muslim population of a region. Notable examples of such persecution have occurred in the

Xinjiang conflict

The Xinjiang conflict ( zh, c=新疆冲突), also known as the East Turkistan conflict, Uyghur–Chinese conflict or Sino-East Turkistan conflict (as argued by the East Turkistan Government-in-Exile), is an ongoing ethnic geopolitical conf ...

in

China, the

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is one of the world's most enduring conflicts, beginning in the mid-20th century. Various attempts have been made to resolve the conflict as part of the Israeli–Palestinian peace process, alongside other eff ...

, the

Yugoslav Wars

The Yugoslav Wars were a series of separate but related Naimark (2003), p. xvii. ethnic conflicts, wars of independence, and insurgencies that took place in the SFR Yugoslavia from 1991 to 2001. The conflicts both led up to and resulted from ...

, and many other conflicts.

As part of the ongoing

Rohingya conflict in

Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

, the

Rohingya genocide

The Rohingya genocide is a series of ongoing persecutions and killings of the Muslim Rohingya people by the Burmese military. The genocide has consisted of two phases to date: the first was a military crackdown that occurred from October 2016 ...

has resulted in over 25,000 deaths , the displacement of over 700,000 refugees,

large-scale sexual violence committed against

Rohingya

The Rohingya people () are a stateless Indo-Aryan ethnic group who predominantly follow Islam and reside in Rakhine State, Myanmar (previously known as Burma). Before the Rohingya genocide in 2017, when over 740,000 fled to Bangladesh, a ...

women and girls, the burning of Rohingya homes and

mosques

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, i ...

, and many other

human rights violations.

The ongoing

Uyghur genocide

The Chinese government has committed a series of ongoing human rights abuses against Uyghurs and other ethnic and religious minorities in Xinjiang that is often characterized as genocide. Since 2014, the Chinese government, under t ...

in

Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

has led to the internment of more than one million Muslims (the majority of them being ethnic

Uyghurs

The Uyghurs; ; ; ; zh, s=, t=, p=Wéiwú'ěr, IPA: ( ), alternatively spelled Uighurs, Uygurs or Uigurs, are a Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central and East Asia. The Uyghur ...

) in

secret detention camps without any legal process. As a result, Muslim birth rates have plummeted in Xinjiang, falling by nearly 24 percent in 2019 alone, compared to just 4.2 percent in the rest of China.

Medieval

Early Islam

In the early days of Islam in

Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow val ...

, the new Muslims were often subjected to abuse and persecution by the

pagan Meccans (often called ''Mushrikin'': the unbelievers or

polytheist

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, t ...

s). Some were killed, such as

Sumayyah bint Khabbab, the seventh convert to Islam, who was allegedly tortured first by

Amr ibn Hishām

ʿAmr ibn Hishām al-Makhzūmī ( ar, عمرو بن هشام المخزومي), (570 – 13 March 624), also known as Abu Jahl (lit. 'Father of Ignorance'), was one of the Meccan polytheist pagan leaders from the Quraysh known for his opposition ...

.

Even the

Islamic prophet

Prophets in Islam ( ar, الأنبياء في الإسلام, translit=al-ʾAnbiyāʾ fī al-ʾIslām) are individuals in Islam who are believed to spread God's message on Earth and to serve as models of ideal human behaviour. Some prophets a ...

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

was subjected to such abuse; while he was praying near the

Kaaba

The Kaaba (, ), also spelled Ka'bah or Kabah, sometimes referred to as al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah ( ar, ٱلْكَعْبَة ٱلْمُشَرَّفَة, lit=Honored Ka'bah, links=no, translit=al-Kaʿbah al-Musharrafah), is a building at the c ...

,

Uqba ibn Abu Mu'ayt

Family Family lineage

‘Uqbah was the son of Abu Mu‘ayṭ ibn Abu ‘Amr ibn Umayyah ibn ‘Abd Shams and of Shayma bint Abd-al-Uzza from the Banu Amir. Abu Mu'ayt's mother was Kabsha bint Abd al-Manat from Banu Amir. Uqbah's aunt, Safiyya ...

threw the

entrails of a sacrificed camel over him. Abu Lahab's wife

Umm Jamil would regularly dump filth outside his door and placed thorns in the path to his house.

Accordingly, if free Muslims were attacked, slaves who converted were subjected to far worse. The master of the

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the Er ...

n

Bilal ibn Rabah (who would become the first

muezzin

The muezzin ( ar, مُؤَذِّن) is the person who proclaims the call to the daily prayer (ṣalāt) five times a day ( Fajr prayer, Zuhr prayer, Asr prayer, Maghrib prayer and Isha prayer) at a mosque. The muezzin plays an important ro ...

) would take him out into the desert in the boiling heat of midday and place a heavy rock on his chest, demanding that he forswear his religion and pray to the polytheists' gods and goddesses, until

Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as well as the first caliph of Islam. He is known with the honori ...

bought him and freed him.

Crusades

The

First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ...

was launched in 1095 by

Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II ( la, Urbanus II; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening th ...

, with the stated goal of regaining control of the sacred city of

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and the

Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Ho ...

from the Muslims, who had captured them from the

Byzantines in 638. The

Fatimid Caliph,

Al Hakim of Cairo, known as the "mad Caliph" destroyed the ancient and magnificent

Constantinian-Era Church of the Holy Sepulcher

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, hy, Սուրբ Հարության տաճար, la, Ecclesia Sancti Sepulchri, am, የቅዱስ መቃብር ቤተክርስቲያን, he, כנסיית הקבר, ar, كنيسة القيامة is a church i ...

in 1009, as well as

most other Christian churches and shrines in the Holy Land.

This, in conjunction with the killing of Germanic pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem from Byzantium, raised the anger of Europe, and inspired Pope Urban II to call on all Catholic rulers,

knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

s, and

gentlemen

A gentleman (Old French: ''gentilz hom'', gentle + man) is any man of good and courteous conduct. Originally, ''gentleman'' was the lowest rank of the landed gentry of England, ranking below an esquire and above a yeoman; by definition, the ra ...

to recapture the Holy Land from Muslim rule.

It was also partly a response to the

Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest ( German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops (investiture) and abbots of monas ...

, which was the most significant

conflict between secular and religious powers in

medieval Europe

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. The controversy began as a dispute between the

Holy Roman Emperor and the

Gregorian Papacy and gave rise to the political concept of

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

as a union of all peoples and sovereigns under the direction of the pope; as both sides tried to marshal public opinion in their favour, people became personally engaged in a dramatic religious controversy. Also of great significance in launching the crusade were the string of victories by the Seljuk Turks, which saw the end of Arab rule in Jerusalem.

On 7 May 1099 the crusaders reached

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, which had been recaptured from the

Seljuks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

by the

Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muh ...

s of Egypt only a year before. On 15 July, the crusaders were able to end the siege by breaking down sections of the walls and entering the city. Over the course of that afternoon, evening, and next morning, the crusaders killed almost every inhabitant of Jerusalem, Muslims and Jews alike. Although many Muslims sought shelter atop the

Temple Mount

The Temple Mount ( hbo, הַר הַבַּיִת, translit=Har haBayīt, label=Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites an ...

inside the

Al-Aqsa Mosque, the crusaders spared few lives. According to the anonymous ''

Gesta Francorum'', in what some believe to be one of the most valuable contemporary sources of the First Crusade, "...the slaughter was so great that our men waded in blood up to their ankles...."

Tancred, Prince of Galilee

Tancred (1075 – December 5 or December 12, 1112) was an Italo- Norman leader of the First Crusade who later became Prince of Galilee and regent of the Principality of Antioch. Tancred came from the house of Hauteville and was the great-grands ...

claimed the

Temple quarter for himself and offered protection to some of the Muslims there, but he was unable to prevent their deaths at the hands of his fellow crusaders. According to Fulcher of Chartres: "Indeed, if you had been there you would have seen our feet coloured to our ankles with the blood of the slain. But what more shall I relate? None of them were left alive; neither women nor children were spared."

During the First Crusade and the massacre at Jerusalem, it has been reported that the Crusaders "

ircledthe screaming, flame-tortured humanity singing 'Christ We Adore Thee!' with their Crusader crosses held high". Muslims were indiscriminately killed, and Jews who had taken refuge in their Synagogue were killed when it was burnt down by the Crusaders.

Southern Italy

The island of

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

was conquered by the

Aghlabids

The Aghlabids ( ar, الأغالبة) were an Arab dynasty of emirs from the Najdi tribe of Banu Tamim, who ruled Ifriqiya and parts of Southern Italy, Sicily, and possibly Sardinia, nominally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliph, for about ...

in the 10th century after over a century of conflict, with the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

losing its final stronghold in 965. The

Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. T ...

conquered the last Arab Muslim stronghold by 1091. Subsequently, taxes were imposed on the Muslim minority called the ''jizya'' (locally spelled ''gisia'') which was a continuation of the

jizya

Jizya ( ar, جِزْيَة / ) is a per capita yearly taxation historically levied in the form of financial charge on dhimmis, that is, permanent non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The jizya tax has been understood in Isla ...

imposed on non-Muslims in Sicily, by Muslim rulers in the 11th century, before the Norman conquest. Another tax on levied them for a time was the ''augustale''. Muslim rebellion broke out during the reign of

Tancred

Tancred or Tankred is a masculine given name of Germanic origin that comes from ''thank-'' (thought) and ''-rath'' (counsel), meaning "well-thought advice". It was used in the High Middle Ages mainly by the Normans (see French Tancrède) and espec ...

as

King of Sicily. Lombard pogroms against Muslims started in the 1160s. Muslim and Christian communities in Sicily became increasingly geographically separated. The island's Muslim communities were mainly isolated beyond an internal frontier which divided the south-western half of the island from the Christian north-east. Sicilian Muslims, a subject population, were dependent on royal protection. When

King William the Good died in 1189, this royal protection was lifted, and the door was opened for widespread attacks against the island's Muslims. Toleration of Muslims ended with increasing Hohenstaufen control. Many oppressive measures, passed by

Frederick II, were introduced in order to please the Popes who could not tolerate Islam being practised in

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

: the result was in a rebellion of Sicily's Muslims. This triggered organized and systematic reprisals which marked the final chapter of Islam in Sicily. The rebellion abated, but direct papal pressure induced Frederick to mass transfer all his Muslim subjects deep into the Italian hinterland.

[A.Lowe: The Barrier and the bridge; p. 92.] In 1224,

Frederick II expelled all Muslims from the island transferring many to Lucera (''Lugêrah'', as it was known in Arabic) over the next two decades. In this controlled environment they could not challenge royal authority and they benefited the crown in taxes and military service. Their numbers eventually reached between 15,000 and 20,000, leading Lucera to be called ''Lucaera Saracenorum'' because it represented the last stronghold of Islamic presence in Italy. During peacetime, Muslims in Lucera were predominantly farmers. They grew

durum wheat,

barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley ...

,

legume

A legume () is a plant in the family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seed of such a plant. When used as a dry grain, the seed is also called a pulse. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consumption, for livestock fo ...

s, grapes, and other fruits. Muslims also kept bees for

honey

Honey is a sweet and viscous substance made by several bees, the best-known of which are honey bees. Honey is made and stored to nourish bee colonies. Bees produce honey by gathering and then refining the sugary secretions of plants (primar ...

. The

Muslim settlement of Lucera was destroyed by

Charles II of Naples

Charles II, also known as Charles the Lame (french: Charles le Boiteux; it, Carlo lo Zoppo; 1254 – 5 May 1309), was King of Naples, Count of Provence and Forcalquier (1285–1309), Prince of Achaea (1285–1289), and Count of Anjou and Main ...

with backing from the papacy. The Muslims were either massacred, forcibly converted, enslaved, or exiled. Their abandoned mosques were demolished, and churches were usually built in their place. The

Lucera Cathedral was built on the site of a mosque which was destroyed. The mosque was the last one still functioning in

medieval Italy

The history of Italy in the Middle Ages can be roughly defined as the time between the collapse of the Western Roman Empire and the Italian Renaissance. The term "Middle Ages" itself ultimately derives from the description of the period of "obsc ...

by that time. Some were exiled, with many finding asylum in

Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the ...

across the

Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

. Islam was no longer a major presence in the island by the 14th century.

The Aghlabids also conquered the island of

Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

at the same time during their invasion of Sicily. Per the

Al-Himyari the island was reduced to an uninhabited ruin due to the conquest. The place was later converted into a settlement by Muslims. The Normans conquered it at the same time as Sicily. The Normans however did not interfere in the matters of Muslims of the island and gave them a tributary status. Their conquest however led to the

Christianization

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, cont ...

and

Latinization of the island. An annual fine on the Christian community for killing of a Muslim was also repealed in the 12th century, signifying the degradation of the protection given to the Muslims. Most of the Maltese Muslims were deported by 1271. All Maltese Muslims had converted to Christianity by the end of the 15th century and had to find ways to disguise their previous identities by Latinizing or adopting new surnames.

Mongol invasions

Genghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr /> Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent) Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin ...

, and the later

Yuan Emperors of China imposed restrictive decrees which forbade Islamic practices like

halal

''Halal'' (; ar, حلال, ) is an Arabic word that translates to "permissible" in English. In the Quran, the word ''halal'' is contrasted with '' haram'' (forbidden). This binary opposition was elaborated into a more complex classification k ...

butchering and forced Muslims to follow Mongol methods of butchering animals. As a result of these decrees, Muslims were forced to slaughter sheep in secret. Genghis Khan referred to Muslims as "slaves", and he also commanded them to follow the Mongol method of eating rather than the halal one.

Circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. Topic ...

was also forbidden. Toward the end of

their rule, the corruption of the Mongol court and the persecution of Muslims became so severe that Muslim generals joined

Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

in rebelling against the Mongols. The

Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang employed Muslim generals like

Lan Yu who rebelled against the Mongols and defeated them in combat. Some Muslim communities were named "kamsia", which, in

Hokkien

The Hokkien () variety of Chinese is a Southern Min language native to and originating from the Minnan region, where it is widely spoken in the south-eastern part of Fujian in southeastern mainland China. It is one of the national languages ...

Chinese, means "thank you"; many Hui Muslims claim that their communities were named "kamsia" because the Han Chinese appreciated the important role which they had played in assisting them to overthrow the Mongols. The Muslims in the

Semu class also revolted against the Yuan dynasty in the

Ispah Rebellion but the rebellion was crushed and the Muslims were massacred by the Yuan loyalist commander Chen Youding.

Following the brutal

Mongol invasion of Central Asia under

Genghis Khan

''Chinggis Khaan'' ͡ʃʰiŋɡɪs xaːŋbr /> Mongol script: ''Chinggis Qa(gh)an/ Chinggis Khagan''

, birth_name = Temüjin

, successor = Tolui (as regent) Ögedei Khan

, spouse =

, issue =

, house = Borjigin ...

, and the

sack of Baghdad which occurred in 1258, the

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe ...

's rule extended across most Muslim lands in

Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

. The

Abbasid caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

was destroyed and the

Islamic civilization suffered much devastation, especially in

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, and

Tengriism and Buddhism replaced it as the official religions of the empire.

[Brown, Daniel W. (2003), '' New Introduction to Islam'', Blackwell Publishing, pp. 185–87, ] However, the Mongols attacked people for goods and riches, not because of their religion. Later, many Mongol khans and rulers such as those of the

Oljeitu, the

Ilkhanid, and the

Golden Horde

The Golden Horde, self-designated as Ulug Ulus, 'Great State' in Turkic, was originally a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate established in the 13th century and originating as the northwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. With the fragment ...

became Muslims along with their subjects. The Mongols made no real effort to replace Islam with any other religion, they just had the desire to plunder goods from anyone who did not submit to their rule, which was characteristic of Mongol warfare. During the

Yuan Dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongols, Mongol-led Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Division of the M ...

which the Mongols founded in China, Muslim scientists were highly regarded and Muslim beliefs were also

respected. Regarding the Mongol attacks, the Muslim historian,

ibn al-Athir lamented:

I shrank from giving a recital of these events on the account of their magnitude and abhorrence. Even now I come reluctant to the task, for who would deem it a light thing to sing the death song of Islam and the Muslims or find it easy to tell this tale? O that my mother had not given me birth!

The detailed atrocities include:

* The

Grand Library of Baghdad, which contained countless precious historical documents and books on subjects that ranged from

medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

to

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, was destroyed. Survivors said that the waters of the

Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

ran black with ink from the enormous quantities of books that were flung into the river.

* Citizens attempted to flee, but they were intercepted by Mongol soldiers who killed them with abandon. Martin Sicker writes that close to 90,000 people may have died (Sicker 2000, p. 111). Other estimates go much higher.

Wassaf claims that the loss of life was several hundred thousand. Ian Frazier of ''

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issue ...

'' claims that estimates of the death toll range from 200,000 to one million.

* The Mongols looted and destroyed mosques, palaces, libraries, and hospitals. Grand buildings which had taken generations to build were burned to the ground.

* The caliph was captured and forced to watch as his citizens were murdered and his treasury was plundered. According to most accounts, the caliph was killed by trampling. The Mongols rolled the caliph up in a rug, and rode their horses over him, because they believed that the earth would be offended if it were ever touched by royal blood. All but one of his sons were killed, and the sole surviving son was sent to Mongolia.

*

Hulagu had to move his camp upwind from the city, due to the stench of decay that emanated from its ruins.

At the intervention of Hulagu's

Nestorian Christian wife,

Dokuz Khatun, the city's Christian inhabitants were spared. Hulagu offered the royal palace to the Nestorian

Catholicos

Catholicos, plural Catholicoi, is a title used for the head of certain churches in some Eastern Christian traditions. The title implies autocephaly and in some cases it is the title of the head of an autonomous church. The word comes from ancien ...

Mar Makikha, and he also ordered that a cathedral should be built for him. Ultimately, the seventh ruler of the Ilkhanate,

Mahmud Ghazan, converted from

Tengrism

Tengrism (also known as Tengriism, Tengerism, or Tengrianism) is an ethnic and old state Turko- Mongolic religion originating in the Eurasian steppes, based on folk shamanism, animism and generally centered around the titular sky god Tengri. ...

to Islam, and thus began the gradual decline of Tengrism and Buddhism in the region and its replacement by the renaissance of Islam. Later, three of the four principal Mongol khanates embraced Islam.

Iberian Peninsula

Arabs relying largely on

Berbers conquered the Iberian Peninsula starting in 711, subduing the whole

Visigothic Kingdom

The Visigothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of the Goths ( la, Regnum Gothorum), was a kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic successor states to ...

by 725. The triumphant

Umayyads got conditional capitulations probably in most of the towns, so that they could get a compromise with the native population. This was not always so. For example, Mérida, Cordova, Toledo, or Narbonne were conquered by storm or after laying siege on them. The arrangement reached with the locals was based on respecting the laws and traditions used in each place, so that the ''Goths'' (a legal concept, not an ethnic one, i.e. the communities ruled by the ''

Forum Iudicum'') continued to be ruled on new conditions by their own tribunals and laws. The Gothic Church remained in place and collaborated with the new masters.

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mus ...

or Muslim ruled Iberian peninsula, was conquered by northern Christian kingdoms in 1492, as a result of their expansion taking place especially after the definite collapse of the

Caliphate of Cordova

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

in 1031.

The coming of the Crusades (starting with the

massacre of Barbastro) and similarly entrenched positions on the northern African

Almoravids

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

, who took over al-Andalus as of 1086, added to the difficult coexistence between communities, including Muslims in Christian ruled territory, or the

Mozarabic rite Christians (quite different from those of the northern kingdoms), and further minority groups. The Almohads, a fanatic north African sect who later occupied al-Andalus, were the only Iberian Muslim rulers to demand conversion, exile, or death from the Christians and Jews.

During the expansion south of the northern Christian kingdoms, depending on the local capitulations, local Muslims were allowed to remain (

Mudéjar

Mudéjar ( , also , , ca, mudèjar , ; from ar, مدجن, mudajjan, subjugated; tamed; domesticated) refers to the group of Muslims who remained in Iberia in the late medieval period despite the Christian reconquest. It is also a term for ...

s) with extreme restrictions, while some were forcefully converted to the Christian faith. After the

conquest of Granada

The Granada War ( es, Guerra de Granada) was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1491 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It ...

, all the Spanish Muslims were under Christian rule. The new acquired population spoke Arabic or

Mozarabic

Mozarabic, also called Andalusi Romance, refers to the medieval Romance varieties spoken in the Iberian Peninsula in territories controlled by the Islamic Emirate of Córdoba and its successors. They were the common tongue for the majority of ...

, and the campaigns to convert them were unsuccessful. Legislation was gradually introduced to remove Islam, culminating with the Muslims being forced to convert to Catholicism by the

Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition ( es, Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición), commonly known as the Spanish Inquisition ( es, Inquisición española), was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Cathol ...

. They were known as

Morisco

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open ...

s and considered

New Christians. Further laws were introduced, as on 25 May 1566, stipulating that they 'had to abandon the use of Arabic, change their costumes, that their doors must remain open every Friday, and other feast days, and that their baths, public and private, to be torn down.' The reason doors were to be left open so as to determine whether they secretly observed any Islamic festivals. King

Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal fro ...

ordered the destruction of all public baths on the grounds of them being relics of infidelity, notorious for their use by Muslims performing their purification rites. The possession of books or papers in Arabic was near concrete proof of disobedience with severe reprisals and penalties. On 1 January 1568, Christian priests were ordered to take all Morisco children between the ages of three and fifteen, and place them in schools, where they were forced to learn Castillian and Christian doctrine. All these laws and measures required force to be implemented, and from much earlier.

Between 1609 and 1614 the Moriscos were expelled from Spain. They were to depart 'under the pain of death and confiscation, without trial or sentence ... to take with them no money, bullion, jewels, or bills of exchange ... just what they could carry.'

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The

Lipka Tatars

The Lipka Tatars (Lipka – refers to '' Lithuania'', also known as Lithuanian Tatars; later also – Polish Tatars, Polish-Lithuanian Tatars, ''Lipkowie'', ''Lipcani'', ''Muślimi'', ''Lietuvos totoriai'') are a Turkic ethnic group who origin ...

, also known as Polish Tatars or Lithuanian Tatars, were a community of Tatar Muslims who migrated into the

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Lit ...

and became

Polonized.

The

Counter-Reformation of the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ...

led to persecution of Muslims,

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

, and

Orthodox Christians. The ways the Muslims were persecuted included banning the repair of old mosques and preventing new ones from being constructed, banning

serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develo ...

of Christians under Muslims, banning marriage of Christian females to Muslims, putting limitations on property ownership among Tatars and the

Polish–Ottoman Wars

Polish–Ottoman Wars can refer to one of the several conflicts between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire:

* Crusade of Varna (1443-1444)

* Polish–Ottoman War (1485–1503)

* Jan Olbracht's Moldavian expedition of 149 ...

fed into the discriminatory atmosphere against them and led to anti-Islamic writings and attacks.

Sikh Khalsa and Sikh Empire

Following the

Sikh

Sikhs ( or ; pa, ਸਿੱਖ, ' ) are people who adhere to Sikhism (Sikhi), a monotheistic religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Guru Nanak. The term ' ...

occupation of

Samana in 1709, the Sikh army participated in a massacre of the city's residents. Ten thousand unarmed Muslim men and women were slain.

Following the

Siege of Sirhind,

Banda Singh Bahadur ordered that all men, women, and children should be executed.

All of the residents of

Sirhind, regardless of whether they were men, women, or children were burned alive or slain.

In December 1757, Sikhs pillaged the Doab and the city of

Jullunder

Jalandhar is the third most-populous city in the Indian state of Punjab and the largest city in Doaba region. Jalandhar lies alongside the Grand Trunk Road and is a well-connected rail and road junction. Jalandhar is northwest of the state ...

.

During this pillaging, "Children were put to the sword, women were dragged out and forcibly converted to

Sikhism

Sikhism (), also known as Sikhi ( pa, ਸਿੱਖੀ ', , from pa, ਸਿੱਖ, lit=disciple', 'seeker', or 'learner, translit= Sikh, label=none),''Sikhism'' (commonly known as ''Sikhī'') originated from the word ''Sikh'', which comes fr ...

", and Mosques were defiled with pigs' blood.

The body of Nassir Ali was dug out by Sikhs and flesh was thrust into it.

Sikh forces commanded by

Ranjit Singh

Ranjit Singh (13 November 1780 – 27 June 1839), popularly known as Sher-e-Punjab or "Lion of Punjab", was the first Maharaja of the Sikh Empire, which ruled the northwest Indian subcontinent in the early half of the 19th century. He ...

captured Peshawar and pillaged the city, cutting down the trees for which the city was famous, burning the palace of

Bala Hissar and defiling the city's

mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a Place of worship, place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers (sujud) ...

s.

Misr Diwan Chand became the first Hindu governor of Kashmir under Singh and enacted dozens of anti-Muslim laws. He raised the tax levels of Muslim subjects, demolished the Jamia Masjid of

Srinagar and prohibited cow slaughter. The punishment for cow slaughter was the death penalty without any exception.

Shah Shujah Durrani

''Padshah Sultan'' Shah Shuja Durrani (Pashto/Dari: ; November 1785 – 5 April 1842) was ruler of the Durrani Empire from 1803 to 1809. He then ruled from 1839 until his death in 1842. Son of Timur Shah Durrani, Shuja Shah was of the Sadduza ...

, the grandson of

Ahmad Shah Durrani

Ahmad Shāh Durrānī ( ps, احمد شاه دراني; prs, احمد شاه درانی), also known as Ahmad Shāh Abdālī (), was the founder of the Durrani Empire and is regarded as the founder of the modern Afghanistan. In July 1747, Ahm ...

, wanted to implement similar anti-cow slaughter policies in the

Emirate of Afghanistan

The Emirate of Afghanistan also referred to as the Emirate of Kabul (until 1855) ) was an emirate between Central Asia and South Asia that is now today's Afghanistan and some parts of today's Pakistan (before 1893). The emirate emerged from t ...

and with help from Singh and the

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sout ...

regained the Afghan throne and imposed a ban on cow slaughter in Kabul.

Sayyid Ahmed Barelvi declared war against Maharaja Ranjit Singh and recruited many Muslims from madrassas. However the Yousufzai and Muhammadzai Khawaneen did not like his egalitarian ideals and betrayed Sayyid Ahmed Shahid and his army at the battle of Balakot and supported the Sikh Army in the Battle of Balakote in 1831, and Barelvi's head was severed by the Sikh General

Hari Singh Nalwa.

Muslims still revered Sayyid Ahmed, however he was defeated and killed in the battle by Sikh Army which was commanded by

Hari Singh Nalwa and

Gulab Singh

Gulab Singh Jamwal (1792–1857) was the founder of Dogra dynasty and the first Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, the largest princely state under the British Raj, which was created after the defeat of the Sikh Empire i ...

. Raja Aggar Khan of

Rajouri

Rajouri or Rajauri (; Pahari: 𑠤𑠬𑠑𑠶𑠤𑠮, راجوری; sa, राजपुर, ) is a city in Rajouri district in the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir, India. It is located about from Srinagar and from Jammu city on t ...

was defeated, humiliated by the Sikh Army commander Gulab Singh and was brought to Lahore where he was beheaded by Gulab Singh of Jammu. Raja Sultan Khan of

Bhimber also met the same fate when he was defeated and captured by the Dogra ruler Gulab Singh and brought to

Jammu

Jammu is the winter capital of the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. It is the headquarters and the largest city in Jammu district of the union territory. Lying on the banks of the river Tawi, the city of Jammu, with an area of ...

where he was imprisoned. Raja Sultan Khan later died in prison.

Modern era

Asia Minor

Armenians and Greek armies attacked many Muslims (both

Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

and

Kurdish) were killed by

Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

and

Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora ...

in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire (including Bayburt, Bitlis, Erzincan, Erzurum, Kars, and Muş).

On 14 May 1919, the Greek army landed in

Izmir (

Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

), which marked the beginning of the

Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, ota, گرب جابهاسی, Garb Cebhesi) in Turkey, and the Asia Minor Campaign ( el, Μικρασιατική Εκστρατεία, Mikrasiatikí Ekstrateía) or the Asia Minor Catastrophe ( el, Μικ ...

. During the war, the Greek side committed a number of atrocities in western provinces (such as Izmir, Manisa, and Uşak),

[U.S. Vice-Consul James Loder Park ''to Secretary of State, ]Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

, 11 April 1923.'' US archives US767.68116/34 the local Muslim population was subjected to massacre, ravaging and rape. Johannes Kolmodin was a Swedish orientalist in Izmir. He wrote in his letters that the Greek army had burned 250 Turkish villages.

Azerbaijan

In 1905 and 1918, thousands of Muslims in Azerbaijan were massacred by Armenian

Dashnaks and

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

.

During the

first Karabakh war in the 1990s, thousands of

Azerbaijani

Azerbaijani may refer to:

* Something of, or related to Azerbaijan

* Azerbaijanis

* Azerbaijani language

See also

* Azerbaijan (disambiguation)

* Azeri (disambiguation)

* Azerbaijani cuisine

* Culture of Azerbaijan

The culture of Azerbaijan ...

Muslims were massacred and their towns depopulated by Armenian forces. Hundreds of civilians were subject to massacre such as in

Khojaly and Karadaghly settlements.

Bulgaria

Half a million Muslims succeeded in reaching Ottoman controlled lands and 672,215 of them were reported to have remained after the war. Approximately a quarter of a million of them perished as a result of massacres, cold, disease, and other harsh conditions.

According to Aubaret, the French Consul in

Ruse in 1876, in the

Danube Vilayet which also included Northern Dobruja in today's Romania, as well as a substantial portion of territory in today's southern Serbia, there were 1,120,000 Muslims and 1,233,500 non-Muslims of whom 1,150,000 were Bulgarian. Between 1876 and 1878, through massacres, epidemics, hunger, and war, a large portion of the Turkish population vanished.

Cambodia

The

Cham Muslims experienced serious purges in which as much as half of their community's entire population was exterminated by authoritarian communists in Cambodia during the 1970s as part of the

Cambodian genocide. About half a million Muslims were killed. According to Cham sources, 132 mosques were destroyed by the

Khmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 197 ...

regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan J ...

. Only 20 of the 113 most prominent Cham clerics in Cambodia survived the rule of the Khmer Rouge.

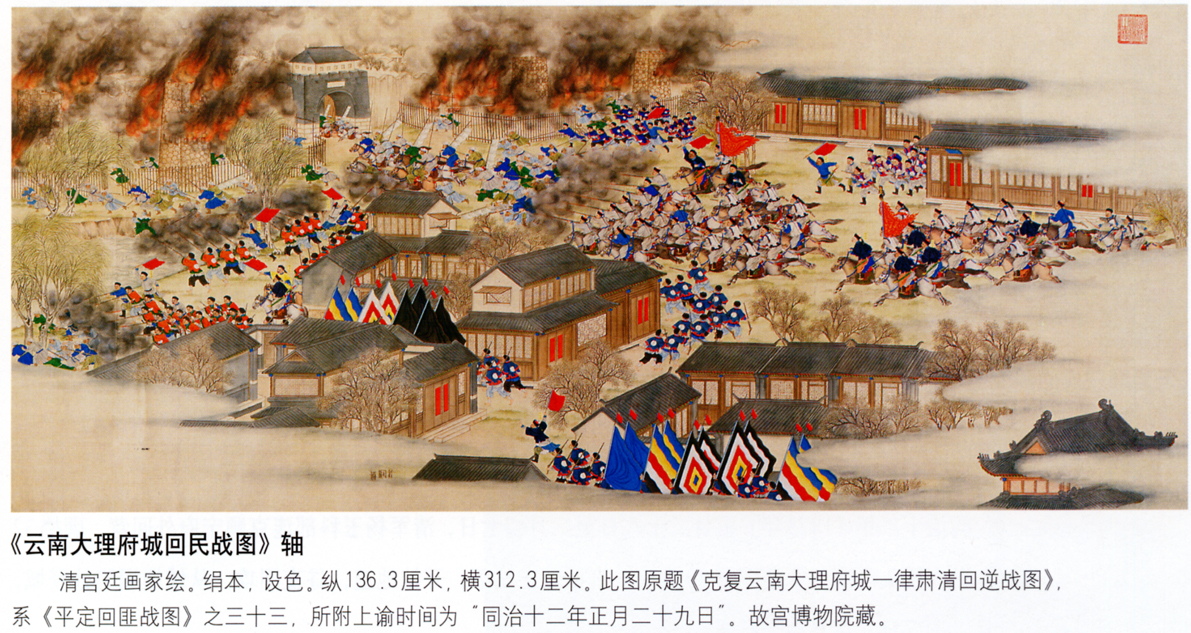

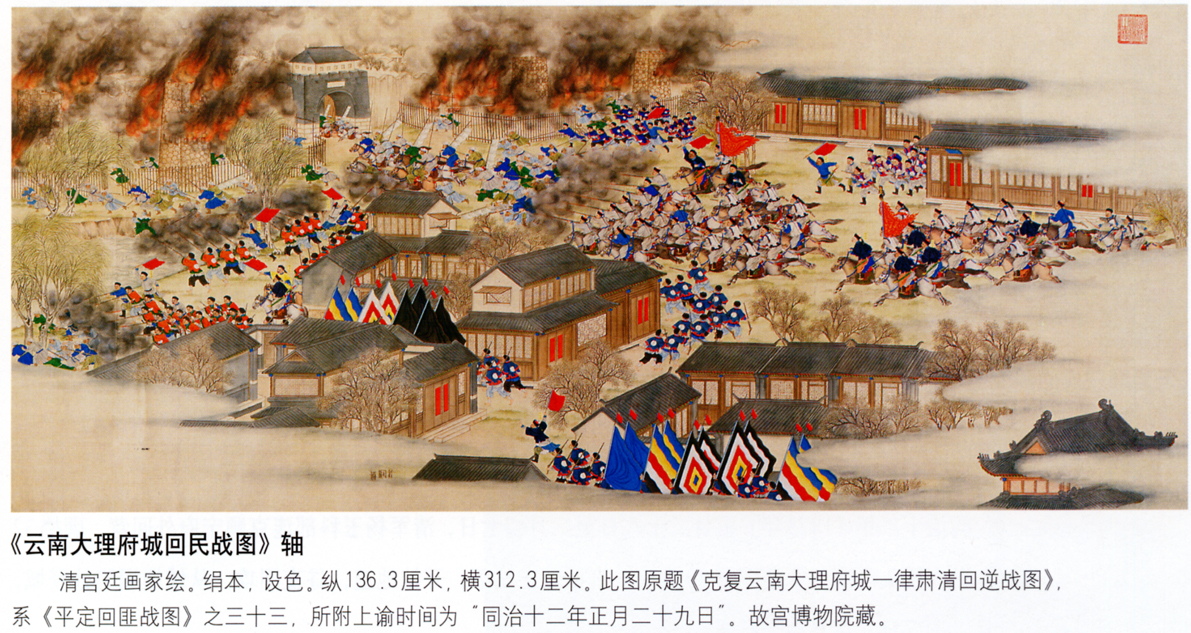

China

The Dungan revolt erupted due to infighting between Muslim Sufi sects, the Khafiya and the Jahariyya, and the

Gedimu. When the rebellion failed, mass-immigration of the

Dungan people

Dungan, Xiao'erjing: ; zh, s=东干族, t=東干族, p=Dōnggān zú, w=Tung1kan1-tsu2, , Xiao'erjing: ; russian: Дунгане, ''Dungane''; ky, Дуңгандар, ''Duñgandar'', دۇنغاندار; kk, Дүңгендер, ''Düñgend ...

into

Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. T ...

,

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental coun ...

, and

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the ea ...

ensued. Before the war, the population of Shaanxi province totalled approximately 13 million inhabitants, at least 1,750,000 of whom were Dungan (Hui). After the war, the population dropped to 7 million; at least 150,000 fled. But once-flourishing Chinese Muslim communities fell 93% in the revolt in Shaanxi province. Between 1648 and 1878, around twelve million

Hui and Han Chinese were killed in ten unsuccessful uprisings.

The

Ush Rebellion in 1765 by

Uyghur Muslims against the

Manchus

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) an ...

of the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

occurred after Uyghur women were gang raped by the servants and son of Manchu official Su-cheng. It was said that ''Ush Muslims had long wanted to sleep on

ucheng and son'shides and eat their flesh.'' because of the rape of Uyghur Muslim women for months by the Manchu official Sucheng and his son. The Manchu Emperor ordered that the Uyghur rebel town be massacred, the Qing forces enslaved all the Uyghur children and women and slaughtered the Uyghur men. Manchu soldiers and Manchu officials regularly having sex with or raping Uyghur women caused massive hatred and anger by Uyghur Muslims to Manchu rule. The

invasion by Jahangir Khoja was preceded by another Manchu official, Binjing who raped a Muslim daughter of the Kokan aqsaqal from 1818 to 1820. The Qing sought to cover up the rape of Uyghur women by Manchus to prevent anger against their rule from spreading among the Uyghurs.

The Manchu official Shuxing'a started an anti-Muslim massacre which led to the

Panthay Rebellion. Shuxing'a developed a deep hatred of Muslims after an incident where he was stripped naked and nearly lynched by a mob of Muslims. He ordered several Hui Muslim rebels to be slowly sliced to death.

The revolts were harshly suppressed by the Manchu government in a manner that amounts to genocide. Approximately a million people in the

Panthay Rebellion were killed,

[Gernet, Jacques. A History of Chinese Civilization. 2. New York: Cambridge

University Press, 1996. ] and several million in the Dungan revolt

[ as a " washing off the Muslims"(洗回 (xi Hui)) policy had been long advocated by officials in the ]Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) and Q ...

government. Many Muslim generals like Ma Zhanao, Ma Anliang, Ma Qianling, Dong Fuxiang, Ma Haiyan, and Ma Julung helped the Qing dynasty defeat the rebel Muslims, and were rewarded, and their followers were spared from the genocide. The Han Chinese Qing general Zuo Zongtang even relocated the Han from the suburbs Hezhou when the Muslims there surrendered as a reward so that Hezhou (now Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture) is still heavily Muslim to this day and is the most important city for Hui Muslims in China. The Muslims were granted amnesty and allowed to live as long as they stayed outside the city. Some of the Muslims who fought, like General Dong, did not do it because they were Muslim, rather, like many other generals, they gathered bands of followers and fought at will. Zuo Zongtang generally massacred New Teaching Jahriyya rebels, even if they surrendered, but spared Old Teaching Khafiya and Sunni Gedimu rebels. Ma Hualong belonged to the New Teaching school of thought, and Zuo executed him, while Hui generals belonging to the Old Teaching clique such as Ma Qianling, Ma Zhan'ao, and Ma Anliang were granted amnesty and even promoted in the Qing military. Moreover, an army of Han Chinese rebels led by Dong Fuxiang surrendered and joined Zuo Zongtang.

Zuo Zongtang generally massacred New Teaching Jahriyya rebels, even if they surrendered, but spared Old Teaching Khafiya and Sunni Gedimu rebels. Ma Hualong belonged to the New Teaching school of thought, and Zuo executed him, while Hui generals belonging to the Old Teaching clique such as Ma Qianling, Ma Zhan'ao, and Ma Anliang were granted amnesty and even promoted in the Qing military. Moreover, an army of Han Chinese rebels led by Dong Fuxiang surrendered and joined Zuo Zongtang.Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated go ...

, mosques along with other religious buildings were often defaced, destroyed, or closed and copies of the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

were destroyed and cemeteries by the Red Guards

Red Guards () were a mass student-led paramilitary social movement mobilized and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 through 1967, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes According to a Red Guard le ...

. During that time, the government also constantly accused Muslims and other religious groups of holding "superstitious beliefs" and promoting " anti-socialist trends". The government began to relax its policies toward Muslims in 1978, and supported worship and rituals. Today, Islam is experiencing a modest revival and there are now many mosques in China. There has been an upsurge in Islamic expression and many nationwide Islamic associations have been organized to co-ordinate inter-ethnic activities among Muslims.

However, restrictions have been imposed on Uyghur Islamic practices because the Chinese government has attempted to link Islamic beliefs with terrorist activities since 2001. Numerous events have led the Chinese government to crack down on most displays of Islamic piety among Uyghurs, including the wearing of veils and long beards. The Ghulja Incident and the July 2009 Ürümqi riots were both caused by abusive treatment of Uyghur Muslims within Chinese society, and they resulted in even more extreme government crackdowns. While Hui Muslims are seen as being relatively docile, Uyghurs are stereotyped as Islamists

Islamism (also often called political Islam or Islamic fundamentalism) is a political ideology which posits that modern State (polity), states and Administrative division, regions should be reconstituted in constitutional, Economics, econom ...

and punished more severely for crimes than Hui are. In 1989, China's government banned a book which was titled ''Xing Fengsu'' ("Sexual Customs") and placed its authors under arrest after Uyghurs and Hui Muslims protested against its publication in Lanzhou and Beijing because it insulted Islam.[Beijing Review, Volume 32 1989](_blank)

p. 13.[ Gladney 1991, p. 2.][Schein 2000](_blank)

p. 154.[Gladney 2004](_blank)

p. 66.[Bulag 2010](_blank)

p. 104.[Gladney 2005](_blank)

p. 257.[Gladney 2013](_blank)

p. 144.[Sautman 2000](_blank)

p. 79.[Gladney 1996](_blank)

p. 341.[Lipman 1996](_blank)

p. 299. Hui Muslims who vandalized property during the protests against the book's publication were not punished but Uyghur protestors were imprisoned.[Gladney 2004](_blank)

p. 232.

Fascist Italy

The pacification of Libya resulted in mass deaths of the indigenous people in

The pacification of Libya resulted in mass deaths of the indigenous people in Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

– one-quarter of Cyrenaica's population of 225,000 people died during the conflict in Italian Libya between Italian military forces and indigenous rebels associated with the Senussi Order that lasted from 1923 until 1932, when the principal Senussi leader, Omar Mukhtar, was captured and executed. Italy committed major war crimes during the conflict; including the use of chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

s, episodes of refusing to take prisoners of war and instead executing surrendering combatants, and mass executions of civilians. Italian authorities committed ethnic cleansing by forcibly expelling 100,000 Bedouin Cyrenaicans, half the population of Cyrenaica, from their settlements that were slated to be given to Italian settlers.

French Algeria

Some governments and scholars have called the French conquest of Algeria

The French invasion of Algeria (; ) took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Deylik of Algiers, and the French consul escalated into a blockade, following which the July Monarchy of France i ...

a genocide. Ben Kiernan

Benedict F. "Ben" Kiernan (born 1953) is an Australian-born American academic and historian who is the Whitney Griswold Professor Emeritus of History, Professor of International and Area Studies and Director of the Genocide Studies Program at Yal ...

, an Australian expert on the Cambodian genocide, wrote in '' Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur'' on the French conquest of Algeria:

By 1875, the French conquest was complete. The war had killed approximately 825,000 indigenous Algerians since 1830. A long shadow of genocidal hatred persisted, provoking a French author to protest in 1882 that in Algeria, "we hear it repeated every day that we must expel the native and if necessary destroy him." As a French statistical journal urged five years later, "the system of extermination must give way to a policy of penetration."

French Algeria became the prototype for a pattern of French colonial rule which has been described as "quasi-apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

". Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A neph ...

oversaw an 1865 decree that allowed Arab and Berber Algerians to request French citizenship – but only if they "renounced their Muslim religion and culture": by 1913, only 1,557 Muslims had been granted French citizenship. Despite periodic attempts at partial reform, the situation of the ''Code de l'indigénat

In communications and information processing, code is a system of rules to convert information—such as a letter, word, sound, image, or gesture—into another form, sometimes shortened or secret, for communication through a communication c ...

'' persisted until the French Fourth Republic

The French Fourth Republic (french: Quatrième république française) was the republican government of France from 27 October 1946 to 4 October 1958, governed by the fourth republican constitution. It was in many ways a revival of the Third Re ...

, which began in 1946, but although Muslim Algerians were accorded the rights of citizenship, the system of discrimination was maintained in more informal ways. This "internal system of apartheid" met with considerable resistance from the Muslims affected by it, and is cited as one of the causes of the 1954 insurrection.Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was ...

, Turkey accused France of committing genocide against 15% of Algeria's population.

Imperial Japan

Imperial Japanese forces slaughtered, raped, and tortured Rohingya Muslims in a massacre in 1942 and expelled hundreds of thousands of Rohingya into Bengal in British India. The Japanese committed countless acts of rape, murder, and torture against thousands of Rohingyas. During this period, some 220,000 Rohingyas are believed to have crossed the border into Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

, then part of British India, to escape the violence. Defeated, 40,000 Rohingyas eventually fled to Chittagong after repeated massacres by the Burmese and Japanese forces.

Japanese forces also carried out massacres, torture, and atrocities on Muslim Moro people

The Moro people or Bangsamoro people are the 13 Muslim-majority ethnolinguistic Austronesian groups of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan, native to the region known as the Bangsamoro (lit. ''Moro nation'' or ''Moro country''). As Muslim-majority e ...

in Mindanao

Mindanao ( ) ( Jawi: مينداناو) is the second-largest island in the Philippines, after Luzon, and seventh-most populous island in the world. Located in the southern region of the archipelago, the island is part of an island group of t ...

, and Sulu

Sulu (), officially the Province of Sulu ( Tausūg: ''Wilāya sin Lupa' Sūg''; tl, Lalawigan ng Sulu), is a province of the Philippines in the Sulu Archipelago and part of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM).

Its capi ...

. A former Japanese Imperial Navy medic, Akira Makino (November 1922 – May 2007) was a former medic in the Imperial Japanese Navy who, in 2006, became the first Japanese ex-soldier to admit to the experiments conducted on human beings in the Philippines during World War II.

Early life

Maki ...

, admitted to carrying out dissections on Moro civilians while they were still alive.

Panglong, a Chinese Muslim town in British Burma, was entirely destroyed by the Japanese invaders in the Japanese invasion of Burma. The Hui Muslim Ma Guanggui became the leader of the Hui Panglong self-defense guard created by Su who was sent by the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

government of the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northea ...

to fight against the Japanese invasion of Panglong in 1942. The Japanese destroyed Panglong, burning it and driving out the over 200 Hui households out as refugees. Yunnan and Kokang received Hui refugees from Panglong driven out by the Japanese. One of Ma Guanggui's nephews was Ma Yeye, a son of Ma Guanghua and he narrated the history of Panglang including the Japanese attack. An account of the Japanese attack on the Hui in Panglong was written and published in 1998 by a Hui from Panglong called "Panglong Booklet". The Japanese attack in Burma caused the Hui Mu family to seek refuge in Panglong but they were driven out again to Yunnan from Panglong when the Japanese attacked Panglong.

The Hui Muslim county of Dachang was subjected to slaughter by the Japanese.

During the

The Hui Muslim county of Dachang was subjected to slaughter by the Japanese.

During the Second Sino-Japanese war

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Thea ...

the Japanese followed what has been referred to as a "killing policy" and destroyed many mosques. According to Wan Lei, "Statistics showed that the Japanese destroyed 220 mosques and killed countless Hui people by April 1941." After the Rape of Nanking

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China (1912–49), Republic of ...

mosques in Nanjing were found to be filled with dead bodies. They also followed a policy of economic oppression which involved the destruction of mosques and Hui communities and made many Hui jobless and homeless. Another policy was one of deliberate humiliation. This included soldiers smearing mosques with pork fat, forcing Hui to butcher pigs to feed the soldiers, and forcing girls to supposedly train as geishas and singers but in fact made them serve as sex slaves. Hui cemeteries were destroyed for military reasons. Many Hui fought in the war against Japan.

Middle East

Lebanon

The Sabra and Shatila massacre was the slaughter of between 762 and 3,500 civilians, mostly Palestinians

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

and Lebanese Shiites, by a Lebanese Christian militia in the Sabra neighbourhood and the adjacent Shatila refugee camp in Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, Lebanon from approximately 6:00 pm 16 September to 8:00 am 18 September 1982.

Myanmar

Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

has a Buddhist majority. The Muslim minority in Myanmar mostly consists of the Rohingya people and the descendants of Muslim immigrants from India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

(including the modern-day nations of Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million pe ...

) and China (the ancestors of Chinese Muslims in Myanmar came from Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked province in the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the ...

province), as well as the descendants of earlier Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

and Persian settlers. Indian Muslims were brought to Burma by the British in order to aid them in clerical work and business. After independence, many Muslims retained their previous positions and achieved prominence in business and politics.

At first, the Buddhist persecution of Muslims arose for religious reasons, and it occurred during the reign of King Bayinnaung

, image = File:Bayinnaung.JPG

, caption = Statue of Bayinnaung in front of the National Museum of Myanmar

, reign = 30 April 1550 – 10 October 1581

, coronation = 11 January 1551 at Toun ...

, 1550–1589 AD. He also disallowed the Eid al-Adha

Eid al-Adha () is the second and the larger of the two main holidays celebrated in Islam (the other being Eid al-Fitr). It honours the willingness of Ibrahim (Abraham) to sacrifice his son Ismail (Ishmael) as an act of obedience to Allah's co ...

, the religious sacrifice of cattle, regarding the killing of animals in the name of religion as a cruel custom. Halal food was also forbidden by King Alaungpaya in the 18th century.

When General

When General Ne Win

Ne Win ( my, နေဝင်း ; 10 July 1910, or 14 or 24 May 1911 – 5 December 2002) was a Burmese politician and military commander who served as Prime Minister of Burma from 1958 to 1960 and 1962 to 1974, and also President of Burma ...

swept to power on a wave of nationalism in 1962, the status of Muslims changed for the worse. Muslims were expelled from the army and rapidly marginalized.Rakhine State

Rakhine State (; , , ; formerly known as Arakan State) is a state in Myanmar (Burma). Situated on the western coast, it is bordered by Chin State to the north, Magway Region, Bago Region and Ayeyarwady Region to the east, the Bay of Ben ...

– an estimated 90,000 people were displaced as a result of the riots.

Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

's pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi

Aung San Suu Kyi (; ; born 19 June 1945) is a Burmese politician, diplomat, author, and a 1991 Nobel Peace Prize laureate who served as State Counsellor of Myanmar (equivalent to a prime minister) and Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Myanm ...

was accused of failing to protect Myanmar's Rohingya Muslims during the 2016–17 persecution. State crime experts from Queen Mary University of London

Queen Mary University of London (QMUL, or informally QM, and previously Queen Mary and Westfield College) is a public university, public research university in Mile End, East London, England. It is a member institution of the federal University of ...

warned that Suu Kyi is "legitimising genocide" in Myanmar.

Some buddhist leaders in Myanmar such as Ashin Wirathu promote violence against Muslims.

Nazi Germany

Nazi ideology's racial theories

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism ( racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies can be more ...

considered ethnic groups which were associated with Islam to be " racially inferior", particularly Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

.

During the Invasion of France, thousands of Muslims, both Arabs and sub-Saharan Africans, who were serving in French colonial units were captured by the Germans. Massacres of these men were widespread, the most notable of these massacres was committed against Moroccans by Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with volunteers and conscripts from both occupied and unoccupied lands.

The grew from th ...

troops during the fighting which occurred around Cambrai, the Moroccans were killed in mass after they were driven from the outskirts of the city and surrendered. In Erquinvillers, another major massacre was committed against captured Muslim Senegalese troops by Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previou ...

and Waffen SS troops.

During Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

, the Einsatzgruppen