Partition Of The Ottoman Empire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The partition of the Ottoman Empire (30 October 19181 November 1922) was a geopolitical event that occurred after

During the Great War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer T. E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia), the establishment of a united Arab state covering a large area of the Arab Middle East in exchange for Arab support of the British during the war. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 encouraged Jewish ambitions for a national home. Lastly, the British promised via the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence that the Hashemite family would have lordship over most land in the region in return for their support in the Great

During the Great War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer T. E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia), the establishment of a united Arab state covering a large area of the Arab Middle East in exchange for Arab support of the British during the war. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 encouraged Jewish ambitions for a national home. Lastly, the British promised via the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence that the Hashemite family would have lordship over most land in the region in return for their support in the Great

The western Allies, particularly

The western Allies, particularly

In the later years of World War I, the Armenians in Russia established a provisional government in the south-west of the Russian Empire. Military conflicts between the Turks and Armenians both during and after the war eventually determined the borders of the state of

In the later years of World War I, the Armenians in Russia established a provisional government in the south-west of the Russian Empire. Military conflicts between the Turks and Armenians both during and after the war eventually determined the borders of the state of

Occupation during and after the War (Ottoman Empire)

in

* Smith, Leonard V.

Post-war Treaties (Ottoman Empire/ Middle East)

in

{{Turkish War of Independence History of Greece (1909–1924) Modern history of Turkey 20th century in Iraq Ottoman Syria Ottoman Greece Partition (politics) 20th century in Armenia Aftermath of World War I in Turkey Turkey–United Kingdom relations Ottoman Empire–United Kingdom relations 20th century in Syria Ottoman period in Armenia Iraq–Turkey relations Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire 1920s in Islam

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and the occupation of Constantinople by British, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

and Italian troops in November 1918. The partitioning was planned in several agreements made by the Allied Powers early in the course of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, notably the Sykes–Picot Agreement, after the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

had joined Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

to form the Ottoman–German Alliance. The huge conglomeration of territories and peoples that formerly comprised the Ottoman Empire was divided into several new states. The Ottoman Empire had been the leading Islamic state

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic term ...

in geopolitical

Geopolitics (from Greek γῆ ''gê'' "earth, land" and πολιτική ''politikḗ'' "politics") is the study of the effects of Earth's geography (human and physical) on politics and international relations. While geopolitics usually refers to ...

, cultural

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tylor ...

and ideological

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

terms. The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the war led to the domination of the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

by Western powers such as Britain and France, and saw the creation of the modern Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

and the Republic of Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

. Resistance to the influence of these powers came from the Turkish National Movement but did not become widespread in the other post-Ottoman states until the period of rapid decolonization after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

The sometimes-violent creation of protectorates in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

and Palestine, and the proposed division of Syria along communal lines, is thought to have been a part of the larger strategy of ensuring tension in the Middle East, thus necessitating the role of Western colonial powers (at that time Britain, France and Italy) as peace brokers and arms suppliers. The League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for adminis ...

granted the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, the British Mandate for Mesopotamia

The Mandate for Mesopotamia ( ar, الانتداب البريطاني على العراق) was a proposed League of Nations mandate to cover Ottoman Iraq (Mesopotamia). It would have been entrusted to the United Kingdom but was superseded by the ...

(later Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

) and the British Mandate for Palestine, later divided into Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 i ...

and the Emirate of Transjordan

The Emirate of Transjordan ( ar, إمارة شرق الأردن, Imārat Sharq al-Urdun, Emirate of East Jordan), officially known as the Amirate of Trans-Jordan, was a British protectorate established on 11 April 1921,

(1921–1946). The Ottoman Empire's possessions in the Arabian Peninsula became the Kingdom of Hejaz, which the Sultanate of Nejd (today Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

) was allowed to annex, and the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen. The Empire's possessions on the western shores of the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

were variously annexed by Saudi Arabia ( al-Ahsa and Qatif), or remained British protectorates (Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the no ...

, Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

, and Qatar

Qatar (, ; ar, قطر, Qaṭar ; local vernacular pronunciation: ), officially the State of Qatar,) is a country in Western Asia. It occupies the Qatar Peninsula on the northeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East; it ...

) and became the Arab States of the Persian Gulf.

After the Ottoman government collapsed completely, its representatives signed the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920, which would have partitioned much of the territory of present-day Turkey among France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy. The Turkish War of Independence forced the Western European powers to return to the negotiating table before the treaty could be ratified. The Western Europeans and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey signed and ratified the new Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conf ...

in 1923, superseding the Treaty of Sèvres and agreeing on most of the territorial issues. One unresolved issue, the dispute between the Kingdom of Iraq

The Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq ( ar, المملكة العراقية الهاشمية, translit=al-Mamlakah al-ʿIrāqiyyah ʾal-Hāshimyyah) was a state located in the Middle East from 1932 to 1958.

It was founded on 23 August 1921 as the Kingdo ...

and the Republic of Turkey over the former province of Mosul, was later negotiated under the auspices of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

in 1926. The British and French partitioned Greater Syria

Syria ( Hieroglyphic Luwian: 𔒂𔒠 ''Sura/i''; gr, Συρία) or Sham ( ar, ٱلشَّام, ash-Shām) is the name of a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in Western Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. Other ...

between them in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. Other secret agreements were concluded with Italy and Russia. The Balfour Declaration encouraged the international Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in J ...

movement to push for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. While a part of the Triple Entente, Russia also had wartime agreements Agreement may refer to:

Agreements between people and organizations

* Gentlemen's agreement, not enforceable by law

* Trade agreement, between countries

* Consensus, a decision-making process

* Contract, enforceable in a court of law

** Meeting of ...

preventing it from participating in the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

. The Treaty of Sèvres formally acknowledged the new League of Nations mandates in the region, the independence of Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

, and British sovereignty over Cyprus.

Background

The Western powers had long believed that they would eventually become dominant in the area claimed by the weak central government of the Ottoman Empire. Britain anticipated a need to secure the area because of its strategic position on the route to Colonial India and perceived itself as locked in a struggle with Russia for imperial influence known asThe Great Game

The Great Game is the name for a set of political, diplomatic and military confrontations that occurred through most of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – involving the rivalry of the British Empire and the Russian Empi ...

. These powers disagreed over their contradictory post-war aims and made several dual and triple agreements.

French Mandates

Syria and Lebanon became a French protectorate (thinly disguised as aLeague of Nations Mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for adminis ...

). French control was met immediately with armed resistance, and, to combat Arab nationalism, France divided the Mandate area into Lebanon and four sub-states.

Mandate of Syria

Compared to the mandate of Lebanon, the situation in Syria was more chaotic. The Entities stated are the ones that are united. * Syrian Federation: Included State of Damascus, Alawite State, and State of Aleppo (including Sanjak of Alexandretta), which were the former territorial components of the briefly existing Arab Kingdom of Syria. * State of Syria (1925–1930): Successor to the Syrian Federation era (Not including the Alawite State). * First Syrian Republic: State of Syria (1925–1930) with the territories of Jabal Druze State and Alawite State incorporated ( Hatay State later merged with Turkey).Mandate of Lebanon

Greater Lebanon was the name of aterritory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

created by France. It was the precursor of modern Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

. It existed between 1 September 1920 and 23 May 1926. France carved its territory from the Levant

The Levant () is an approximation, approximate historical geography, historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology an ...

ine landmass (mandated by the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

) to create a "haven" for the Maronite Christian population. Maronites gained self-rule and secured their position in independent Lebanon in 1943.

French intervention on behalf of the Maronites had begun with the capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, agreements made during the 16th to the 19th centuries. In 1866, when Youssef Bey Karam led a Maronite uprising in Mount Lebanon, a French-led naval force arrived to help, making threats against the governor, Dawood Pasha, at the Sultan's Porte and later removing Karam to safety.

British Mandates

The British were awarded three mandated territories, with one of Sharif Hussein's sons,Faisal

Faisal, Faisel, Fayçal or Faysal ( ar, فيصل) is an Arabic given name.

Faisal, Fayçal or Faysal may also refer to:

People

* King Faisal (disambiguation)

** Faisal I of Iraq and Syria (1885–1933), leader during the Arab Revolt

** Faisal ...

, installed as King of Iraq

The king of Iraq ( ar, ملك العراق, ''Malik al-‘Irāq'') was Iraq's head of state and monarch from 1921 to 1958. He served as the head of the Iraqi monarchy—the Hashemite dynasty. The king was addressed as His Majesty (صاحب ال ...

and Transjordan providing a throne for another of Hussein's sons, Abdullah. Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 i ...

was placed under direct British administration, and the Jewish population was allowed to increase, initially under British protection. Most of the Arabian peninsula fell to another British ally, Ibn Saud, who created the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

in 1932.

Mandate for Mesopotamia

Mosul was allocated to France under the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement and was subsequently given to Britain under the 1918 Clemenceau–Lloyd George Agreement. Great Britain and Turkey disputed control of the former Ottoman province ofMosul

Mosul ( ar, الموصل, al-Mawṣil, ku, مووسڵ, translit=Mûsil, Turkish: ''Musul'', syr, ܡܘܨܠ, Māwṣil) is a major city in northern Iraq, serving as the capital of Nineveh Governorate. The city is considered the second large ...

in the 1920s. Under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conf ...

Mosul fell under the British Mandate of Mesopotamia, but the new Turkish republic claimed the province as part of its historic heartland. A three-person League of Nations committee went to the region in 1924 to study the case and in 1925 recommended the region remain connected to Iraq, and that the UK should hold the mandate for another 25 years, to assure the autonomous rights of the Kurdish population. Turkey rejected this decision. Nonetheless, Britain, Iraq and Turkey made a treaty on 5 June 1926, that mostly followed the decision of the League Council. Mosul stayed under British Mandate of Mesopotamia until Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

was granted independence in 1932 by the urging of King Faisal, though the British retained military bases and transit rights for their forces in the country.

Mandate for Palestine

During the Great War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer T. E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia), the establishment of a united Arab state covering a large area of the Arab Middle East in exchange for Arab support of the British during the war. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 encouraged Jewish ambitions for a national home. Lastly, the British promised via the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence that the Hashemite family would have lordship over most land in the region in return for their support in the Great

During the Great War, Britain produced three contrasting, but feasibly compatible, statements regarding their ambitions for Palestine. Britain had supported, through British intelligence officer T. E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia), the establishment of a united Arab state covering a large area of the Arab Middle East in exchange for Arab support of the British during the war. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 encouraged Jewish ambitions for a national home. Lastly, the British promised via the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence that the Hashemite family would have lordship over most land in the region in return for their support in the Great Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

.

The Arab Revolt, which was in part orchestrated by Lawrence, resulted in British forces under General Edmund Allenby

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, (23 April 1861 – 14 May 1936) was a senior British Army officer and Imperial Governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in the First World War, in which he led ...

defeating the Ottoman forces in 1917 in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign and occupying Palestine and Syria. The land was administered by the British for the remainder of the war.

The United Kingdom was granted control of Palestine by the Versailles Peace Conference which established the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

in 1919. Herbert Samuel, a former Postmaster General in the British cabinet who was instrumental in drafting the Balfour Declaration, was appointed the first High Commissioner in Palestine. In 1920 at the San Remo conference, in Italy, the League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for adminis ...

over Palestine was assigned to Britain. In 1923 Britain transferred a part of the Golan Heights to the French Mandate of Syria

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

, in exchange for the Metula

Metula ( he, מְטֻלָּה) is a town in the Northern District of Israel. Metula is located next to the northern border with Lebanon. In it had a population of . Metula is the northernmost town in Israel.

History Bronze and Iron Age

Metula ...

region.

Independence movements

When the Ottomans departed, the Arabs proclaimed an independent state in Damascus, but were too weak, militarily and economically, to resist the European powers for long, and Britain and France soon re-established control. During the 1920s and 1930s Iraq, Syria and Egypt moved towards independence, although the British and French did not formally depart the region until after World War II. But in Palestine, the conflicting forces of Arab nationalism and Zionism created a situation from which the British could neither resolve nor extricate themselves from. The rise to power ofNazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

in Germany created a new urgency in the Zionist quest to create a Jewish state in Palestine, leading to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Arabian Peninsula

On the Arabian Peninsula, the Arabs were able to establish several independent states. In 1916Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca

Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi ( ar, الحسين بن علي الهاشمي, al-Ḥusayn bin ‘Alī al-Hāshimī; 1 May 18544 June 1931) was an Arab leader from the Banu Hashim clan who was the Sharif and Emir of Mecca from 1908 and, after procla ...

, established the Kingdom of Hejaz, while the Emirate of Riyadh was transformed into the Sultanate of Nejd. In 1926 the Kingdom of Nejd and Hejaz was formed, which in 1932 became the kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

. The Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen became independent in 1918, while the Arab States of the Persian Gulf became ''de facto'' British protectorates, with some internal autonomy.

Anatolia

The Russians, British, Italians, French,Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, Albania, Greeks in Italy, ...

, Assyrians

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

and Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ...

ns all made claims to Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The r ...

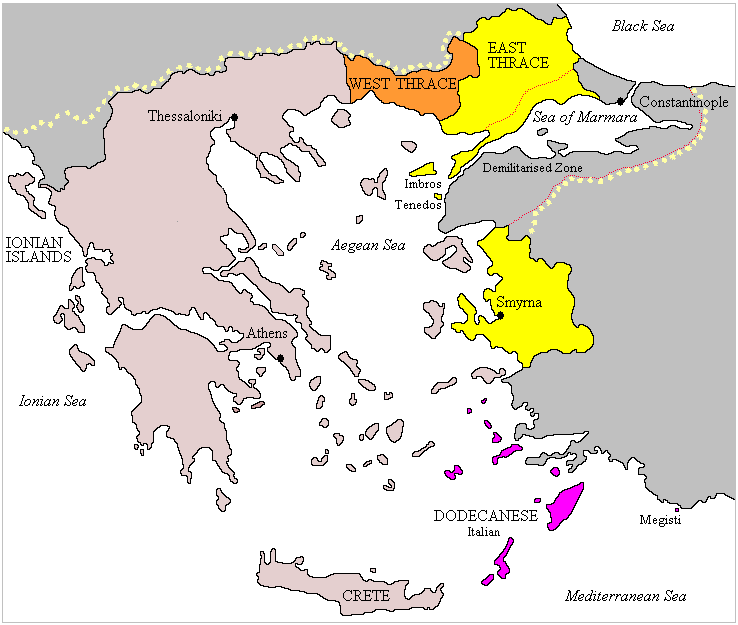

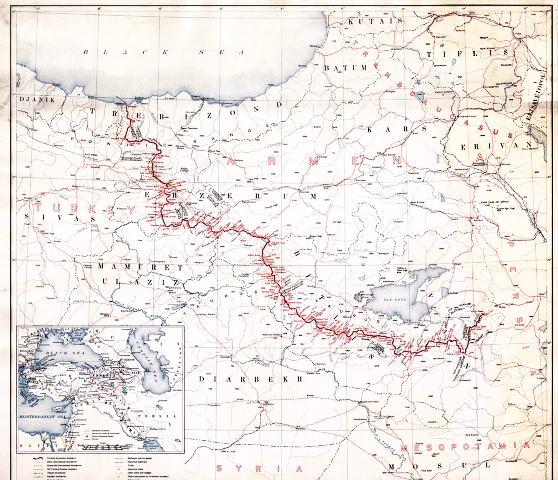

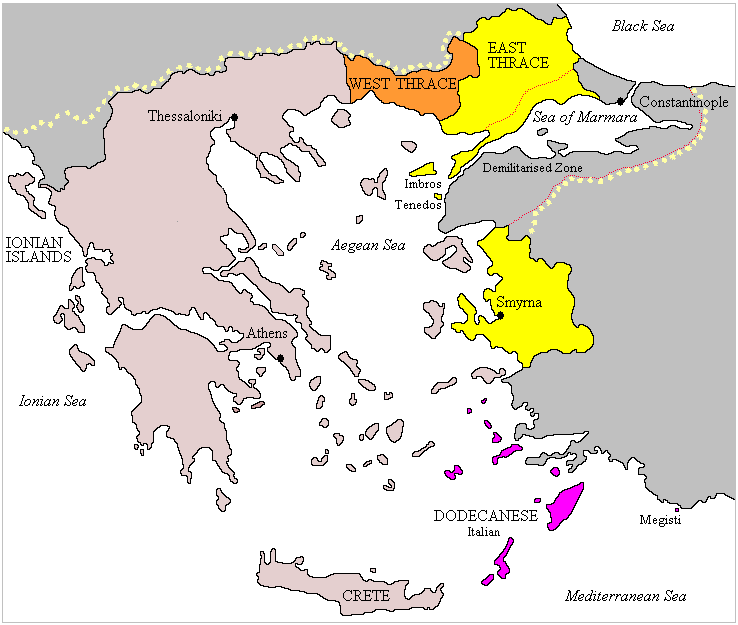

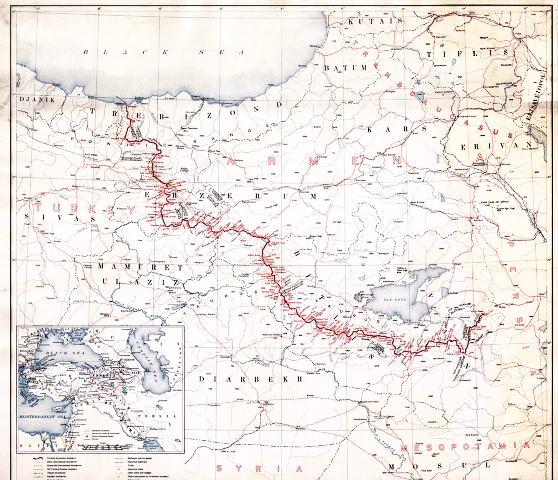

, based on a collection of wartime promises, military actions, secret agreements, and treaties. According to the Treaty of Sèvres, all but the Assyrians would have had their wishes honoured. Armenia was to be given a significant portion of the east, known as Wilsonian Armenia

Wilsonian Armenia () refers to the unimplemented boundary configuration of the First Republic of Armenia in the Treaty of Sèvres, as drawn by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson's Department of State. The Treaty of Sèvres was a peace treaty that ha ...

, extending as far down as the Lake Van

Lake Van ( tr, Van Gölü; hy, Վանա լիճ, translit=Vana lič̣; ku, Gola Wanê) is the largest lake in Turkey. It lies in the far east of Turkey, in the provinces of Van and Bitlis in the Armenian highlands. It is a saline soda lake, ...

area and as far west as Mush, Greece was to be given Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

and the area around it (and likely would have gained Constantinople and all of Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, which was administered as internationally controlled and demilitarized territory), Italy was to be given control over the south-central and western coast of Anatolia around Antalya

Antalya () is the fifth-most populous city in Turkey as well as the capital of Antalya Province. Located on Anatolia's southwest coast bordered by the Taurus Mountains, Antalya is the largest Turkish city on the Mediterranean coast outside the Ae ...

, France to be given the area of Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian language, Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from th ...

, and Britain to be given all the area south of Armenia. The Treaty of Lausanne, by contrast, forfeited all arrangements and territorial annexations.

Russia

In March 1915, Foreign Minister of the Russian Empire, Sergey Sazonov, told British and French Ambassadors George Buchanan and Maurice Paléologue that a lasting postwar settlement demanded Russian possession of "the city ofConstantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

, the western shore of the Bosporus, Sea of Marmara, and Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

, as well as southern Thrace up to the Enos-Media line", and "a part of the Asiatic coast between the Bosporus, the Sakarya River

The Sakarya (Sakara River, tr, Sakarya Irmağı; gr, Σαγγάριος, translit=Sangarios; Latin: ''Sangarius'') is the third longest river in Turkey. It runs through the region known in ancient times as Phrygia. It was considered one of th ...

, and a point to be determined on the shore of the Bay of İzmit

İzmit () is a district and the central district of Kocaeli province, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental ...

."''Armenia on the Road to Independence'', 1967, p. 59 The Constantinople Agreement was made public by the Russian newspaper ''Izvestiya

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in 1917, it was a Newspaper of record#Newspapers of record by reputation, newspaper of record in the Soviet Union until ...

'' in November 1917, to gain the support of the Armenian public for the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

. However, said revolution effectively ended Russian plans.

United Kingdom

The British seeking control over thestraits of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the B ...

led to the Occupation of Constantinople, with French assistance, from 13 November 1918 to 23 September 1923. After the Turkish War of Independence and the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, the troops left the city.

Italy

Under the 1917 Agreement of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne between France, Italy, and the United Kingdom, Italy was to receive all southwestern Anatolia except theAdana

Adana (; ; ) is a major city in southern Turkey. It is situated on the Seyhan River, inland from the Mediterranean Sea. The administrative seat of Adana province, it has a population of 2.26 million.

Adana lies in the heart of Cilicia, ...

region, including İzmir

İzmir ( , ; ), also spelled Izmir, is a metropolitan city in the western extremity of Anatolia, capital of the province of the same name. It is the third most populous city in Turkey, after Istanbul and Ankara and the second largest urban aggl ...

. However, in 1919 the Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greeks, Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberati ...

obtained the permission of the Paris Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

to occupy İzmir, overriding the provisions of the agreement.

France

Under the secret Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916, the French obtainedHatay

Hatay Province ( tr, Hatay ili, ) is the southernmost province of Turkey. It is situated almost entirely outside Anatolia, along the eastern coast of the Levantine Sea. The province borders Syria to its south and east, the Turkish province o ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

and Syria and expressed a desire for the part of South-Eastern Anatolia. The 1917 Agreement of St. Jean-de-Maurienne between France, Italy and the United Kingdom allotted France the Adana region.

The French army, along with the British, occupied parts of Anatolia from 1919 to 1921 in the Franco-Turkish War, including coal mines, railways, the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, ...

ports of Zonguldak, Karadeniz Ereğli and Constantinople, Uzunköprü in Eastern Thrace and the region of Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian language, Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from th ...

. France eventually withdrew from all these areas, after the Armistice of Mudanya, the Treaty of Ankara Treaty of Ankara may refer to:

*Treaty of Ankara (1921)

*Treaty of Ankara (1926)

The Treaty of Ankara (1926), also known as The Frontier Treaty of 1926 ( tr, Ankara Anlaşması), was signed 5 June 1926 in Ankara by Turkey, United Kingdom and M ...

and the Treaty of Lausanne.

Greece

The western Allies, particularly

The western Allies, particularly British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern ...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

, promised Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

territorial gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

if Greece entered the war on the Allied side. The promised territories included eastern Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

, the islands of Imbros ( Gökçeada) and Tenedos ( Bozcaada), and parts of western Anatolia around the city of İzmir.

In May 1917, after the exile of Constantine I of Greece

Constantine I ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Αʹ, ''Konstantínos I''; – 11 January 1923) was King of Greece from 18 March 1913 to 11 June 1917 and from 19 December 1920 to 27 September 1922. He was commander-in-chief of the Hellenic Ar ...

, Greek prime minister Eleuthérios Venizélos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation move ...

returned to Athens and allied with the Entente. Greek military forces (though divided between supporters of the monarchy and supporters of Venizélos) began to take part in military operations against the Bulgarian army on the border. That same year, İzmir was promised to Italy under the Agreement of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne between France, Italy and the United Kingdom.

At the 1918 Paris Peace Conference, based on the wartime promises, Venizélos lobbied hard for an expanded Hellas (the Megali Idea) that would include the small Greek-speaking community in far Southern Albania, the Orthodox Greek-speaking community in Thrace (including Constantinople) and the Orthodox community in Asia Minor. In 1919, despite Italian opposition, he obtained the permission of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 for Greece to occupy İzmir.

South West Caucasian Republic

The South West Caucasian Republic was an entity established on Russian territory in 1918, after the withdrawal of Ottoman troops to the pre-World War I border as a result of theArmistice of Mudros

Concluded on 30 October 1918 and taking effect at noon the next day, the Armistice of Mudros ( tr, Mondros Mütarekesi) ended hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies of World War I. It was signed by ...

. It had a nominally independent provisional government headed by Fakhr al-Din Pirioghlu

Fakhr, also Fakhar or Faḵr ( ar, فخر), may be a given name or a surname. It literally means "pride", "honor", "glory" in Arabic. It may also be a part of a given name such as Fakhr al-Din, "pride of the faith". Notable people with the name i ...

and based in Kars

Kars (; ku, Qers; ) is a city in northeast Turkey and the capital of Kars Province. Its population is 73,836 in 2011. Kars was in the ancient region known as ''Chorzene'', (in Greek Χορζηνή) in classical historiography ( Strabo), part of ...

.

After fighting broke out between it and both Georgia and Armenia, British High Commissioner Admiral Somerset Arthur Gough-Calthorpe occupied Kars on 19 April 1919, abolishing its parliament and arresting 30 members of its government. He placed Kars province under Armenian rule.

Armenia

In the later years of World War I, the Armenians in Russia established a provisional government in the south-west of the Russian Empire. Military conflicts between the Turks and Armenians both during and after the war eventually determined the borders of the state of

In the later years of World War I, the Armenians in Russia established a provisional government in the south-west of the Russian Empire. Military conflicts between the Turks and Armenians both during and after the war eventually determined the borders of the state of Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ...

.

Administration for Western Armenia

In April 1915, Russia supported the establishment of the Armenian provisional government under Russian-Armenian GovernorAram Manukian

Aram Manukian, reformed spelling: Արամ Մանուկյան, and he is also referred to as simply Aram. (19 March 187929 January 1919), was an Armenian revolutionary, statesman, and a leading member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation ...

, leader of the resistance in the Defense of Van. The Armenian national liberation movement hoped that Armenia could be liberated from the Ottoman regime in exchange for helping the Russian army. However, the Tsarist regime had a secret wartime agreement with the other members of the Triple Entente about the eventual fate of several Anatolian territories, named the Sykes–Picot Agreement. These plans were made public by the Armenian revolutionaries in 1917 to gain the support of the Armenian public.

In the meantime, the provisional government was becoming more stable as more Armenians were moving into its territory. In 1917, 150,000 Armenians relocated to the provinces of Erzurum

Erzurum (; ) is a List of cities in Turkey, city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses t ...

, Bitlis, Muş and Van

A van is a type of road vehicle used for transporting goods or people. Depending on the type of van, it can be bigger or smaller than a pickup truck and SUV, and bigger than a common car. There is some varying in the scope of the word across th ...

. And Armen Garo (known as Karekin Pastirmaciyan) and other Armenian leaders asked for the Armenian regulars in the European theatre to be transferred to the Caucasian front.

The Russian revolution left the front in eastern Turkey in a state of flux. In December 1917, a truce was signed by representatives of the Ottoman Empire and the Transcaucasian Commissariat. However, the Ottoman Empire began to reinforce its Third Army on the eastern front. Fighting began in mid-February 1918. Armenians, under heavy pressure from the Ottoman army and Kurdish irregulars, were forced to withdraw from Erzincan to Erzurum

Erzurum (; ) is a List of cities in Turkey, city in eastern Anatolia, Turkey. It is the largest city and capital of Erzurum Province and is 1,900 meters (6,233 feet) above sea level. Erzurum had a population of 367,250 in 2010.

The city uses t ...

and then to Kars

Kars (; ku, Qers; ) is a city in northeast Turkey and the capital of Kars Province. Its population is 73,836 in 2011. Kars was in the ancient region known as ''Chorzene'', (in Greek Χορζηνή) in classical historiography ( Strabo), part of ...

, eventually evacuating even Kars on 25 April. As a response to the Ottoman advances, the Transcaucasian Commissariat evolved into the short-lived Transcaucasian Federation; its disintegration resulted in Armenians forming the Democratic Republic of Armenia on 30 May 1918. The Treaty of Batum, signed on 4 June, reduced the Armenian republic to an area of only 11,000 km2.

Wilsonian Armenia

At theParis Peace Conference, 1919

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, the Armenian Diaspora and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenia ...

argued that Historical Armenia, the region which had remained outside the control of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

from 1915 to 1918, should be part of the Democratic Republic of Armenia. Arguing from the principles in Woodrow Wilson's "Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace ter ...

" speech, the Armenian Diaspora

The Armenian diaspora refers to the communities of Armenians outside Armenia and other locations where Armenians are considered an indigenous population. Since antiquity, Armenians have established communities in many regions throughout the world. ...

argued Armenia had "the ability to control the region", based on the Armenian control established after the Russian Revolution. The Armenians also argued that the dominant population of the region was becoming more Armenian as Turkish inhabitants were moving to the western provinces. Boghos Nubar, the president of the Armenian National Delegation, added: "In the Caucasus, where, without mentioning the 150,000 Armenians in the Imperial Russian Army, more than 40,000 of their volunteers contributed to the liberation of a portion of the Armenian vilayets, and where, under the command of their leaders, Antranik and Nazerbekoff, they, alone among the peoples of the Caucasus, offered resistance to the Turkish armies, from the beginning of the Bolshevist withdrawal right up to the signing of an armistice."

President Wilson accepted the Armenian arguments for drawing the frontier and wrote: "The world expects of them (the Armenians), that they give every encouragement and help within their power to those Turkish refugees who may desire to return to their former homes in the districts of Trebizond, Erzerum, Van

A van is a type of road vehicle used for transporting goods or people. Depending on the type of van, it can be bigger or smaller than a pickup truck and SUV, and bigger than a common car. There is some varying in the scope of the word across th ...

and Bitlis remembering that these peoples, too, have suffered greatly."President Wilson's Acceptance letter for drawing the frontier given to the Paris Peace Conference, Washington, 22 November 1920. The conference agreed with his suggestion that the Democratic Republic of Armenia should expand into present-day eastern Turkey.

Georgia

After the fall of the Russian Empire, Georgia became an independent republic and sought to maintain control of Batumi as well as Ardahan, Artvin, and Oltu, the areas with Muslim Georgian elements, which had been acquired by Russia from the Ottomans in 1878. The Ottoman forces occupied the disputed territories by June 1918, forcing Georgia to sign the Treaty of Batum. After the demise of the Ottoman power, Georgia regained Ardahan and Artvin from local Muslim militias in 1919 and Batum from the British administration of that maritime city in 1920. It claimed but never attempted to control Oltu, which was also contested by Armenia. Soviet Russia and Turkey launched a near-simultaneous attack on Georgia in February–March 1921, leading to new territorial rearrangements finalized in the Treaty of Kars, by which Batumi remained within the borders of now- Soviet Georgia, while Ardahan and Artvin were recognized as parts of Turkey.Republic of Turkey

Between 1918 and 1923, Turkish resistance movements led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk forced the Greeks and Armenians out of Anatolia, while the Italians never established a presence. The Turkish revolutionaries also suppressed Kurdish attempts to become independent in the 1920s. After the Turkish resistance gained control over Anatolia, there was no hope of meeting the conditions of the Treaty of Sèvres. Before joining theSoviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, the Democratic Republic of Armenia signed the Treaty of Alexandropol

The Treaty of Alexandropol ( hy, Ալեքսանդրապոլի պայմանագիր; tr, Gümrü Anlaşması) was a peace treaty between the First Republic of Armenia and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. The treaty ended the Turkish-Armenian ...

, on 3 December 1920, agreeing to the current border between the two countries, though the Armenian government had already collapsed due to a concurrent Soviet invasion on 2 December. Afterwards Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ...

became an integral part of the Soviet Union. This border was ratified again with the Treaty of Moscow (1921), in which the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

ceded the already Turkish-occupied provinces of Kars

Kars (; ku, Qers; ) is a city in northeast Turkey and the capital of Kars Province. Its population is 73,836 in 2011. Kars was in the ancient region known as ''Chorzene'', (in Greek Χορζηνή) in classical historiography ( Strabo), part of ...

, Iğdır

Iğdır (Turkish ; ku, Îdir or ; hy, Իգդիր, Igdir, also ) is the capital of Iğdır Province in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Turkey.

History

Iğdır went by the Armenian name of Tsolakert during the Middle Ages. s.v. "Igdir," Armen ...

, Ardahan, and Artvin to Turkey in exchange for the Adjara region with its capital city of Batumi.

Turkey and the newly formed Soviet Union, along with the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic,; russian: Армянская Советская Социалистическая Республика, translit=Armyanskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika) also commonly referred to as Soviet A ...

and Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (Georgian SSR; ka, საქართველოს საბჭოთა სოციალისტური რესპუბლიკა, tr; russian: Грузинская Советская Соц� ...

, ratified the Treaty of Kars on 11 September 1922, establishing the north-eastern border of Turkey and bringing peace to the region, despite none of them being internationally recognized at the time. Finally, the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conf ...

, signed in 1923, formally ended all hostilities and led to the creation of the modern Turkish Republic.

See also

* Abolition of the Ottoman sultanate * Dissolution of the Ottoman EmpireNotes

Bibliography

* Fromkin, David. '' A Peace to End All Peace: Creating the Modern Middle East''. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1989. * Quilliam, Neil. ''Syria and the New World Order''. Reading, UK: Ithaca Press (Garnet), 1999.External links

*Criss, Nur BilgeOccupation during and after the War (Ottoman Empire)

in

* Smith, Leonard V.

Post-war Treaties (Ottoman Empire/ Middle East)

in

{{Turkish War of Independence History of Greece (1909–1924) Modern history of Turkey 20th century in Iraq Ottoman Syria Ottoman Greece Partition (politics) 20th century in Armenia Aftermath of World War I in Turkey Turkey–United Kingdom relations Ottoman Empire–United Kingdom relations 20th century in Syria Ottoman period in Armenia Iraq–Turkey relations Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire 1920s in Islam