Pakistani Inventions on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This article lists inventions and discoveries made by scientists with Pakistani nationality within Pakistan and outside the country, as well as those made in the territorial area of what is now Pakistan prior to the

*

* *

*

independence of Pakistan

The Pakistan Movement ( ur, , translit=Teḥrīk-e-Pākistān) was a political movement in the first half of the 20th century that aimed for the creation of Pakistan from the Muslim-majority areas of British India. It was connected to the per ...

in 1947.

Bronze Age

Indus Valley civilisation

*

*Proto-writing

Proto-writing consists of visible marks communicating limited information. Such systems emerged from earlier traditions of symbol systems in the early Neolithic, as early as the 7th millennium BC in Eastern Europe and China. They used ideograph ...

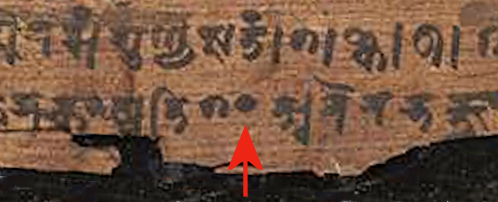

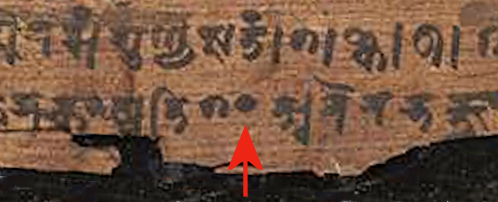

:Indus script

The Indus script, also known as the Harappan script, is a corpus of symbols produced by the Indus Valley Civilisation. Most inscriptions containing these symbols are extremely short, making it difficult to judge whether or not they constituted ...

was a Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

script developed along Indus river

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

, in modern day's Pakistan.

* Button

A button is a fastener that joins two pieces of fabric together by slipping through a loop or by sliding through a buttonhole.

In modern clothing and fashion design, buttons are commonly made of plastic but also may be made of metal, wood, o ...

, ornamental: Buttons—made from seashell

A seashell or sea shell, also known simply as a shell, is a hard, protective outer layer usually created by an animal or organism that lives in the sea. The shell is part of the body of the animal. Empty seashells are often found washe ...

—were used in the Indus Valley civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

for ornamental purposes by 2000 BCE.Hesse, Rayner W. & Hesse (Jr.), Rayner W. (2007). ''Jewelrymaking Through History: An Encyclopedia''. Greenwood Publishing Group. 35. . Some buttons were carved into geometric shapes and had holes pieced into them so that they could attached to clothing by using a thread. Ian McNeil (1990) holds that: "The button, in fact, was originally used more as an ornament than as a fastening, the earliest known being found at Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

. It is made of a curved shell and about 5000 years old."

* Plough, animal-drawn: The earliest archeological evidence of an animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the Kingdom (biology), biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals Heterotroph, consume organic material, Cellular respiration#Aerobic respiration, breathe oxygen, are Motilit ...

-drawn plough dates back to 2500 BCE in the Indus Valley Civilization in Pakistan.

* Stepwell

Stepwells (also known as vavs or baori) are wells or ponds with a long corridor of steps that descend to the water level. Stepwells played a significant role in defining subterranean architecture in western India from 7th to 19th century. So ...

: Earliest clear evidence of the origins of the stepwell is found in the Indus Valley Civilization's archaeological site at Mohenjodaro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Bhinmal

Bhinmal (previously Shrimal Nagar) is an ancient town in the Jalore District of Rajasthan, India. It is south of Jalore. Bhinmal was the capital of the Bhil king, then the capital of Gurjaradesa, comprising modern-day southern Rajasthan and n ...

(850-950 CE) were constructed.Livingston & Beach, page xxiii

* Bow Drill: Bow drills were used in Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh (; ur, ) is a Neolithic archaeological site (dated ) situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan in Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, Ka ...

between the 4th and 5th millennium BC. This bow drill—used to drill holes into lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color.

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mines, ...

and carnelian

Carnelian (also spelled cornelian) is a brownish-red mineral commonly used as a semi-precious gemstone. Similar to carnelian is sard, which is generally harder and darker (the difference is not rigidly defined, and the two names are often use ...

—was made of green jasper.Kulke, Hermann & Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). ''A History of India''. Routledge. 22. . Similar drills were found in other parts of the Indus Valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

one millennium later.

*

*Public Baths

Public baths originated when most people in population centers did not have access to private bathing facilities. Though termed "public", they have often been restricted according to gender, religious affiliation, personal membership, and other cr ...

: The earliest public baths are found in the ruins in of the Indus Valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

. According to John Keay

John Stanley Melville Keay FRGS is a British historian, journalist, radio presenter and lecturer specialising in popular histories of India, the Far East and China, often with a particular focus on their colonisation and exploration by Europe ...

, the "Great Bath

The Great Bath is one of the best-known structures among the ruins of the Harappan Civilization excavated at Mohenjo-daro in Sindh, Pakistan.

" of Mohenjo Daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

was the size of 'a modest municipal swimming pool

A swimming pool, swimming bath, wading pool, paddling pool, or simply pool, is a structure designed to hold water to enable Human swimming, swimming or other leisure activities. Pools can be built into the ground (in-ground pools) or built ...

', complete with stairs leading down to the water at each one of its ends.Keay, John (2001), ''India: A History'', 13–14, Grove Press, .

*Grid Plan

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogona ...

: By 2600 BC, Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

, and other major cities of the Indus Valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

, were built with blocks divided by a grid of straight streets, running north–south and east–west. Each block was subdivided by small lanes.

*Gemstone

A gemstone (also called a fine gem, jewel, precious stone, or semiprecious stone) is a piece of mineral crystal which, in cut and polished form, is used to make jewelry or other adornments. However, certain rocks (such as lapis lazuli, opal, ...

s and Lapis Lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color.

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mines, ...

– Lapis lazuli artifacts, dated to 7570 BCE, have been found at Bhirrana

Bhirrana, also Bhirdana and Birhana, (Hindi: भिरड़ाना; IAST: Bhirḍāna) is an archaeological site, located in a small village in Fatehabad District, in the Indian state of Haryana. Bhirrana's earliest archaeological layers pr ...

, which is the oldest site of Indus Valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

.

*Flush Toilet

A flush toilet (also known as a flushing toilet, water closet (WC) – see also toilet names) is a toilet that disposes of human waste (principally urine and feces) by using the force of water to ''flush'' it through a drainpipe to another lo ...

: Mohenjo-Daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Drainage System: The

* Concept of Zero:A symbol for zero, a large dot likely to be the precursor of the still-current hollow symbol, is used throughout the Bakhshali manuscript, a practical manual on arithmetic for merchants, discovered in Northern Pakistan. In 2017, three samples from the manuscript were shown by

* Concept of Zero:A symbol for zero, a large dot likely to be the precursor of the still-current hollow symbol, is used throughout the Bakhshali manuscript, a practical manual on arithmetic for merchants, discovered in Northern Pakistan. In 2017, three samples from the manuscript were shown by

(2007),

in contrast to the later

Indus Valley civilisation

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900&n ...

had advanced sewerage

Sewerage (or sewage system) is the infrastructure that conveys sewage or surface runoff (stormwater, meltwater, rainwater) using sewers. It encompasses components such as receiving drainage, drains, manholes, pumping stations, storm overflows, a ...

and drainage systems. All houses in the major cities of Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

and Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';gravity sewer

A gravity sewer is a conduit utilizing the energy resulting from a difference in elevation to remove unwanted water. The term ''sewer'' implies removal of sewage or surface runoff rather than water intended for use;''Design and Construction of San ...

s, which lined the major streets.

*Tanning (leather)

Tanning is the process of treating Skinning, skins and Hide (skin), hides of animals to produce leather. A tannery is the place where the skins are processed.

Tanning hide into leather involves a process which permanently alters the protein str ...

:Tanning was being carried out by the inhabitants of Mehrgarh

Mehrgarh (; ur, ) is a Neolithic archaeological site (dated ) situated on the Kacchi Plain of Balochistan in Pakistan. It is located near the Bolan Pass, to the west of the Indus River and between the modern-day Pakistani cities of Quetta, Ka ...

in Pakistan between 7000 and 3300 BCE.Possehl, Gregory L. (1996). ''Mehrgarh'' in ''Oxford Companion to Archaeology'', edited by Brian Fagan. Oxford University Press.

Ancient Age

* Concept of Zero:A symbol for zero, a large dot likely to be the precursor of the still-current hollow symbol, is used throughout the Bakhshali manuscript, a practical manual on arithmetic for merchants, discovered in Northern Pakistan. In 2017, three samples from the manuscript were shown by

* Concept of Zero:A symbol for zero, a large dot likely to be the precursor of the still-current hollow symbol, is used throughout the Bakhshali manuscript, a practical manual on arithmetic for merchants, discovered in Northern Pakistan. In 2017, three samples from the manuscript were shown by radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

to come from three different centuries: from AD 224–383, AD 680–779, and AD 885–993, making it South Asia's oldest recorded use of the zero symbol. It is not known how the birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 30 ...

bark fragments from different centuries forming the manuscript came to be packaged together.

*Kharosthi numerals

The Kharoṣṭhī script, also spelled Kharoshthi (Kharosthi: ), was an ancient Indo-Iranians, Indo-Iranian script used by various Aryan peoples in north-western regions of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely around present-day northern ...

:They were developed in what is now Northern Pakistan in 2nd century BCE, later evolving into Hindu–Arabic numeral system

The Hindu–Arabic numeral system or Indo-Arabic numeral system Audun HolmeGeometry: Our Cultural Heritage 2000 (also called the Hindu numeral system or Arabic numeral system) is a positional decimal numeral system, and is the most common syste ...

. It later gave rise to modern Arabic Numerals

Arabic numerals are the ten numerical digits: , , , , , , , , and . They are the most commonly used symbols to write Decimal, decimal numbers. They are also used for writing numbers in other systems such as octal, and for writing identifiers ...

.

*Formal grammar

In formal language theory, a grammar (when the context is not given, often called a formal grammar for clarity) describes how to form strings from a language's alphabet that are valid according to the language's syntax. A grammar does not describe ...

: In his treatise Astadhyayi, Panini gives formal production rules and definitions to describe the formal grammar of Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

.

* Morphological analysis: Panini, who lived during 5th century BCE in Gandhara

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Vall ...

developed methods of morphological analysis. Pāṇini's theory of morphological analysis was more advanced than any equivalent Western theory before the 20th century.

*Early Universities: Pakistan was the seat of ancient learning and some consider Taxila to be an early university or centre of higher education

Higher education is tertiary education leading to award of an academic degree. Higher education, also called post-secondary education, third-level or tertiary education, is an optional final stage of formal learning that occurs after completi ...

, others do not consider it a university in the modern sense Taxila(2007),

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

:in contrast to the later

Nalanda

Nalanda (, ) was a renowned ''mahavihara'' (Buddhist monastic university) in ancient Magadha (modern-day Bihar), India."Nalanda" (2007). ''Encarta''. Takshashila is described in some detail in later

* Discovery of

* Discovery of

* The

* The

* A boot sector

* A boot sector

applications: Can we invent more than herbal crack cream?

The Express Tribune {{DEFAULTSORT:Pakistani Inventions And Discoveries Lists of inventions or discoveries

Jātaka

The Jātakas (meaning "Birth Story", "related to a birth") are a voluminous body of literature native to India which mainly concern the previous births of Gautama Buddha in both human and animal form. According to Peter Skilling, this genre is ...

tales, written in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

around the 5th century CE. Generally, a student entered Taxila at the age of sixteen. The Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the ...

and the Eighteen Arts, which included skills such as archery

Archery is the sport, practice, or skill of using a bow to shoot arrows.Paterson ''Encyclopaedia of Archery'' p. 17 The word comes from the Latin ''arcus'', meaning bow. Historically, archery has been used for hunting and combat. In m ...

, hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

, and elephant

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae an ...

lore, were taught, in addition to its law school

A law school (also known as a law centre or college of law) is an institution specializing in legal education, usually involved as part of a process for becoming a lawyer within a given jurisdiction.

Law degrees Argentina

In Argentina, ...

, medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

, and school of military science

Military science is the study of military processes, institutions, and behavior, along with the study of warfare, and the theory and application of organized coercive force. It is mainly focused on theory, method, and practice of producing mil ...

.Radha Kumud Mookerji (2nd ed. 1951; reprint 1989). ''Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist'' (p. 478-489). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. .

Medieval Age

*Windpumps

A windpump is a type of windmill which is used for pumping water.

Windpumps were used to pump water since at least the 9th century in what is now Afghanistan, Iran and Pakistan. The use of wind pumps became widespread across the Muslim world an ...

: Windpumps were used to pump water since at least the 9th century in what are now Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, making its one of the earliest mentioned use.

Post-independence

Chemistry

* Development of the world's first workable plastic magnet at room temperature by organic chemist and polymer scientist Naveed Zaidi.Physics

electroweak interaction

In particle physics, the electroweak interaction or electroweak force is the unified description of two of the four known fundamental interactions of nature: electromagnetism and the weak interaction. Although these two forces appear very differe ...

by Abdus Salam

Mohammad Abdus Salam Salam adopted the forename "Mohammad" in 1974 in response to the anti-Ahmadiyya decrees in Pakistan, similarly he grew his beard. (; ; 29 January 192621 November 1996) was a Punjabi Pakistani theoretical physicist and a ...

, along with two Americans Sheldon Glashow

Sheldon Lee Glashow (, ; born December 5, 1932) is a Nobel Prize-winning American theoretical physicist. He is the Metcalf Professor of Mathematics and Physics at Boston University and Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics, Emeritus, at Harvard U ...

and Steven Weinberg

Steven Weinberg (; May 3, 1933 – July 23, 2021) was an American theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate in physics for his contributions with Abdus Salam and Sheldon Glashow to the unification of the weak force and electromagnetic interactio ...

. The discovery led them to receive the Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

.

*Abdus Salam

Mohammad Abdus Salam Salam adopted the forename "Mohammad" in 1974 in response to the anti-Ahmadiyya decrees in Pakistan, similarly he grew his beard. (; ; 29 January 192621 November 1996) was a Punjabi Pakistani theoretical physicist and a ...

who along with Steven Weinberg

Steven Weinberg (; May 3, 1933 – July 23, 2021) was an American theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate in physics for his contributions with Abdus Salam and Sheldon Glashow to the unification of the weak force and electromagnetic interactio ...

independently predicted the existence of a subatomic particle now called the Higgs boson

The Higgs boson, sometimes called the Higgs particle, is an elementary particle in the Standard Model of particle physics produced by the quantum excitation of the Higgs field,

one of the fields in particle physics theory. In the Stand ...

, Named after a British physicist who theorized that it endowed other particles with mass.

*The development of the Standard Model

The Standard Model of particle physics is the theory describing three of the four known fundamental forces (electromagnetism, electromagnetic, weak interaction, weak and strong interactions - excluding gravity) in the universe and classifying a ...

of particle physics by Sheldon Glashow

Sheldon Lee Glashow (, ; born December 5, 1932) is a Nobel Prize-winning American theoretical physicist. He is the Metcalf Professor of Mathematics and Physics at Boston University and Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics, Emeritus, at Harvard U ...

's discovery in 1960 of a way to combine the electromagnetic

In physics, electromagnetism is an interaction that occurs between particles with electric charge. It is the second-strongest of the four fundamental interactions, after the strong force, and it is the dominant force in the interactions of a ...

and weak interaction

In nuclear physics and particle physics, the weak interaction, which is also often called the weak force or weak nuclear force, is one of the four known fundamental interactions, with the others being electromagnetism, the strong interaction, ...

s. In 1967 Steven Weinberg

Steven Weinberg (; May 3, 1933 – July 23, 2021) was an American theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate in physics for his contributions with Abdus Salam and Sheldon Glashow to the unification of the weak force and electromagnetic interactio ...

and Abdus Salam

Mohammad Abdus Salam Salam adopted the forename "Mohammad" in 1974 in response to the anti-Ahmadiyya decrees in Pakistan, similarly he grew his beard. (; ; 29 January 192621 November 1996) was a Punjabi Pakistani theoretical physicist and a ...

incorporated the Higgs mechanism

In the Standard Model of particle physics, the Higgs mechanism is essential to explain the generation mechanism of the property "mass" for gauge bosons. Without the Higgs mechanism, all bosons (one of the two classes of particles, the other bein ...

into Glashow's electroweak theory

In particle physics, the electroweak interaction or electroweak force is the unified description of two of the four known fundamental interactions of nature: electromagnetism and the weak interaction. Although these two forces appear very differe ...

, giving it its modern form.

Medicine

* The

* The Ommaya reservoir

An Ommaya reservoir is an intraventricular catheter system that can be used for the aspiration of cerebrospinal fluid or for the delivery of drugs (e.g. chemotherapy) into the cerebrospinal fluid. It consists of a catheter in one lateral ventricle ...

- a system for the delivery of drugs (e.g. chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated to chemo and sometimes CTX or CTx) is a type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) as part of a standardized chemotherapy regimen. Chemotherap ...

) into the cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless body fluid found within the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates.

CSF is produced by specialised ependymal cells in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the bra ...

for treatment of patients with brain tumours

A brain tumor occurs when abnormal cells form within the brain. There are two main types of tumors: malignant tumors and benign (non-cancerous) tumors. These can be further classified as primary tumors, which start within the brain, and secondar ...

- was developed by Ayub K. Ommaya

Ayub Khan Ommaya MD, ScD (hc), FRCS, FACS (1930 - 2008) was a Pakistani American neurosurgeon and the inventor of the Ommaya reservoir. The reservoir is used to provide chemotherapy directly to the tumor site for brain tumors. Ommaya was also a ...

, a Pakistani neurosurgeon

Neurosurgery or neurological surgery, known in common parlance as brain surgery, is the medical specialty concerned with the surgical treatment of disorders which affect any portion of the nervous system including the brain, spinal cord and peri ...

.

*A non-invasive

A medical procedure is defined as ''non-invasive'' when no break in the skin is created and there is no contact with the mucosa, or skin break, or internal body cavity beyond a natural or artificial body orifice. For example, deep palpation and p ...

technology for monitoring intracranial pressure (ICP) - developed by Faisal Kashif.

Computing

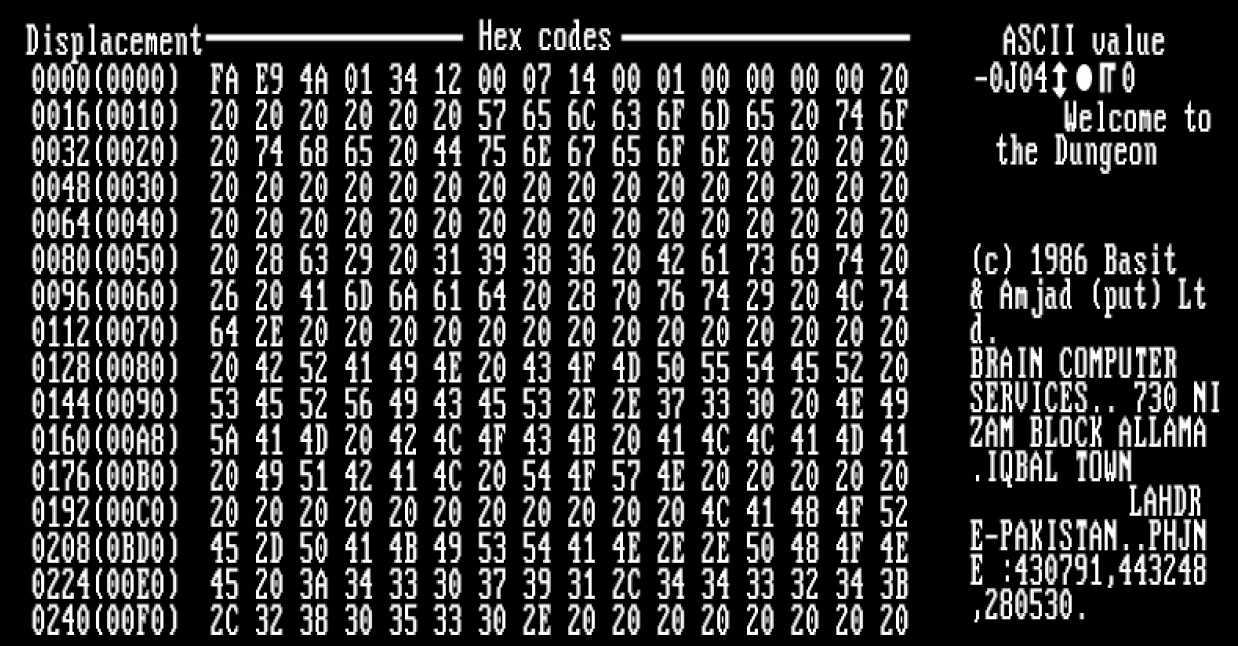

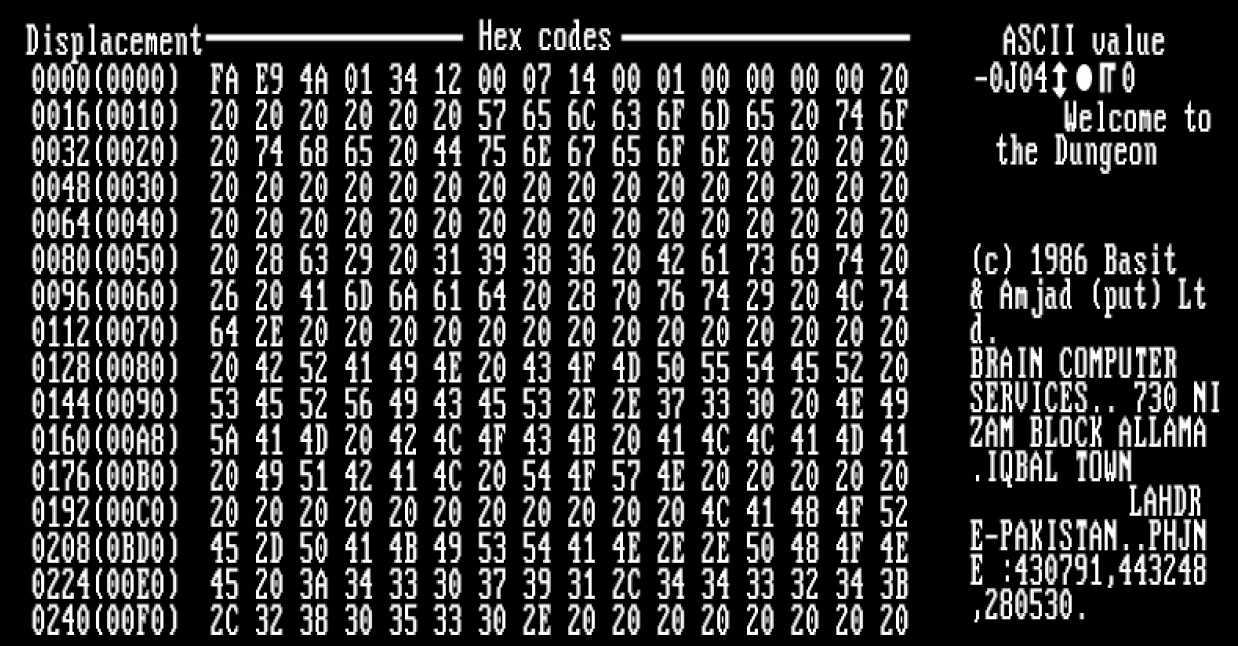

* A boot sector

* A boot sector computer virus

A computer virus is a type of computer program that, when executed, replicates itself by modifying other computer programs and inserting its own code. If this replication succeeds, the affected areas are then said to be "infected" with a compu ...

dubbed (c)Brain, one of the first computer viruses in history, was created in 1986 by the Farooq Alvi Brothers in Lahore, Pakistan, reportedly to deter unauthorized copying of the software they had written.

* Neurochip

A neurochip is an integrated circuit chip (such as a microprocessor) that is designed for interaction with neuronal cells.

Formation

It is made of silicon that is doped in such a way that it contains EOSFETs (electrolyte- oxide-semiconductor ...

by Pakistani-Canadian inventor Naweed Syed

Naweed I. Syed is a Pakistani-born Canadian neuro-scientist. He is the first scientist to connect brain cells to a silicon chip, creating the world's first neurochip.

Syed has travelled worldwide giving lectures and presentations about the huma ...

.

Music

* The Sagar veena, astring instrument

String instruments, stringed instruments, or chordophones are musical instruments that produce sound from vibrating strings when a performer plays or sounds the strings in some manner.

Musicians play some string instruments by plucking the ...

designed for use in classical music

Classical music generally refers to the art music of the Western world, considered to be distinct from Western folk music or popular music traditions. It is sometimes distinguished as Western classical music, as the term "classical music" also ...

, was developed entirely in Pakistan over the last 40 years at the Sanjannagar Institute in Lahore

Lahore ( ; pnb, ; ur, ) is the second most populous city in Pakistan after Karachi and 26th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 13 million. It is the capital of the province of Punjab where it is the largest city. ...

by Raza Kazim.

Economics

* TheHuman Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, whi ...

was devised by Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq

Mahbub ul Haq ( ur, ; ) was a Pakistani economist, international development theorist, and politician who served as the Minister of Finance of Pakistan from 10 April 1985 to 28 January 1986, and again from June to December 1988 as a caretak ...

in 1990 and had the explicit purpose "to shift the focus of development economics from national income accounting to people centered policies".Haq, Mahbub ul. 1995. Reflections on Human Development. New York: Oxford University Press.

See also

* :Pakistani inventors *Science and technology in Pakistan

Science and technology is a growing field in Pakistan and has played an important role in the country's development since its founding. Pakistan has a large pool of scientists, engineers, doctors, and technicians assuming an active role in ...

* List of inventions and discoveries of the Indus Valley Civilization

This list of inventions and discoveries of the Indus Valley Civilisation lists the technological and civilisational achievements of the Indus Valley Civilisation, an ancient civilisation which flourished in the Bronze Age around the general regi ...

covers the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

culture that flourished from 3300 to 1300 BCE in what is now Pakistan

* List of Indian inventions and discoveries

This list of Indian inventions and discoveries details the inventions, scientific discoveries and contributions of India, including the ancient, classical and post-classical nations in the subcontinent historically referred to as India and th ...

covers inventions made in the Indian subcontinent between the decline of the IVC and the formation of Pakistan

References

External links

applications: Can we invent more than herbal crack cream?

The Express Tribune {{DEFAULTSORT:Pakistani Inventions And Discoveries Lists of inventions or discoveries

Inventions

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an i ...

Inventions and discoveries