Otto Klemperer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Otto Nossan Klemperer (14 May 18856 July 1973) was a 20th-century conductor and composer, originally based in Germany, and then the US, Hungary and finally Britain. His early career was in opera houses, but he was later better known as a concert-hall conductor.

A protégé of the composer Gustav Mahler, Klemperer was appointed to a succession of increasingly senior conductorships in opera houses in and around Germany. From 1929 to 1931 he was director of the Kroll Opera in Berlin, where he presented new works and avant-garde productions of classics. The rise of the

"Klemperer, Otto"

Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 17 July 2014 Kwast moved to Berlin, first to the

"Otto Klemperer, Conductor, Dead at 88"

, ''The New York Times'', 8 July 1973, p. 1

The conductor's biographer

The conductor's biographer

The orchestra's finances were perilous. Its founder and sponsor,

The orchestra's finances were perilous. Its founder and sponsor,

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

s caused him to leave Germany in 1933, and shortly afterwards he was appointed chief conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic

The Los Angeles Philharmonic, commonly referred to as the LA Phil, is an American orchestra based in Los Angeles, California. It has a regular season of concerts from October through June at the Walt Disney Concert Hall, and a summer season at th ...

, and guest-conducted other American orchestras, including the San Francisco Symphony

The San Francisco Symphony (SFS), founded in 1911, is an American orchestra based in San Francisco, California. Since 1980 the orchestra has been resident at the Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall in the city's Hayes Valley neighborhood. The San Fra ...

, the New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

and later the Pittsburgh Symphony

The ''Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra'' (''PSO'') is an American orchestra based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The orchestra's home is Heinz Hall, located in Pittsburgh's Cultural District.

History

The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra is an Americ ...

, which he reorganised as a permanent ensemble.

In the late 1930s Klemperer became ill with a brain tumour. An operation to remove it was successful, but left him lame and partly paralysed on his right side. Throughout his life he had bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of depression and periods of abnormally elevated mood that last from days to weeks each. If the elevated mood is severe or associated with ...

, and after the operation he went through an intense manic phase of the illness and then a long spell of severe depression. His career was severely disrupted and did not fully recover until the mid-1940s. He served as the musical director of the Hungarian State Opera in Budapest from 1947 to 1950.

Klemperer's later career centred on London. In 1951 he began an association with the Philharmonia Orchestra

The Philharmonia Orchestra is a British orchestra based in London. It was founded in 1945 by Walter Legge, a classical music record producer for EMI. Among the conductors who worked with the orchestra in its early years were Richard Strauss, ...

. By that time better known for his readings of the core German symphonic repertoire than for experimental modern music he gave concerts and made almost 200 recordings with the Philharmonia and its successor, the New Philharmonia, until his retirement in 1972. He became widely considered the most authoritative living interpreter of Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

, Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid- Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped wit ...

, Bruckner and other German symphonists, and also of Mahler. His approach to Mozart was less universally liked, being thought by some to be heavy.

Life and career

Early years

Otto Nossan Klemperer was born on 14 May 1885 in Breslau,Province of Silesia

The Province of Silesia (german: Provinz Schlesien; pl, Prowincja Śląska; szl, Prowincyjŏ Ślōnskŏ) was a province of Prussia from 1815 to 1919. The Silesia region was part of the Prussian realm since 1740 and established as an official p ...

, in what was then the Imperial German state of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

; the city is now Wrocław

Wrocław (; , . german: Breslau, , also known by other names) is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, roughly ...

, Poland. He was the second child and only son of Nathan Klemperer and his wife Ida, ''née'' Nathan. The family name had originally been Klopper, but was changed to Klemperer in 1787 in response to a decree by Emperor Joseph II

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 u ...

aimed at assimilating Jews into Christian society. Nathan Klemperer was originally from Josefov

Josefov (also Jewish Quarter; german: Josefstadt) is a town quarter and the smallest cadastral area of Prague, Czech Republic, formerly the Jewish ghetto of the town. It is surrounded by the Old Town. The quarter is often represented by the flag ...

, the ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

in the Bohemian city of Prague; Ida was Sephardi

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefar ...

, from Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

. Both parents were musical: Nathan sang and Ida played the piano.

When Klemperer was four the family moved from Breslau to Hamburg, where Nathan earned a modest living in various commercial posts and his wife gave piano lessons. It was decided quite early in Klemperer's life that he would become a professional musician, and when he was about five he started piano lessons with his mother. At the Hoch Conservatory

Dr. Hoch's Konservatorium – Musikakademie was founded in Frankfurt am Main on 22 September 1878. Through the generosity of Frankfurter Joseph Hoch, who bequeathed the Conservatory one million German gold marks in his testament, a school for ...

in Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on its ...

he studied the piano with James Kwast

James Kwast (23 November 185231 October 1927) was a Dutch-German pianist and renowned teacher of many other notable pianists. He was also a minor composer and editor.

Biography

Jacob James Kwast was born in Nijkerk, Netherlands, in 1852. Afte ...

and theory with Ivan Knorr.Heyworth, Peter and John Lucas"Klemperer, Otto"

Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, retrieved 17 July 2014 Kwast moved to Berlin, first to the

Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory The Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory (german: Klindworth-Scharwenka-Konservatorium) was a music institute in Berlin, established in 1893, which for decades (until 1960) was one of the most internationally renowned schools of music. It was formed f ...

and then to the Stern Conservatory The Stern Conservatory (''Stern'sches Konservatorium'') was a private music school in Berlin with many distinguished tutors and alumni. The school is now part of Berlin University of the Arts.

History

It was founded in 1850 as the ''Berliner Mu ...

. Klemperer followed him at each move, and later credited him with the whole basis of his musical development. Among Klemperer's other teachers was Hans Pfitzner

Hans Erich Pfitzner (5 May 1869 – 22 May 1949) was a German composer, conductor and polemicist who was a self-described anti-modernist. His best known work is the post-Romantic opera '' Palestrina'' (1917), loosely based on the life of the ...

, with whom he studied composition and conducting.

In 1905 Klemperer met Gustav Mahler at a rehearsal of the latter's Second Symphony in Berlin. Oscar Fried conducted, and Klemperer was given charge of the off-stage orchestra. He later made a piano arrangement of the symphony, which he played to the composer in 1907 when visiting Vienna. In the interim he made his public debut as a conductor in May 1906, taking over from Fried after the first night of the fifty-performance run of Max Reinhardt

Max Reinhardt (; born Maximilian Goldmann; 9 September 1873 – 30 October 1943) was an Austrian-born theatre and film director, intendant, and theatrical producer. With his innovative stage productions, he is regarded as one of the most promi ...

's production of ''Orpheus in the Underworld

''Orpheus in the Underworld'' and ''Orpheus in Hell'' are English names for (), a comic opera with music by Jacques Offenbach and words by Hector-Jonathan Crémieux, Hector Crémieux and Ludovic Halévy. It was first performed as a two-act "op� ...

'' at the New Theatre, Berlin.

Mahler wrote a short testimonial, recommending Klemperer, on a small card which Klemperer kept for the rest of his life. On the strength of it he was appointed chorus master and assistant conductor at the German Opera in Prague in 1907.

German opera houses

From Prague Klemperer moved to be assistant conductor at theHamburg State Opera

The Hamburg State Opera (in German: Staatsoper Hamburg) is a German opera company based in Hamburg. Its theatre is near the square of Gänsemarkt. Since 2015, the current ''Intendant'' of the company is Georges Delnon, and the current ''Genera ...

(1910–1912), where Lotte Lehmann

Charlotte "Lotte" Lehmann (February 27, 1888 – August 26, 1976) was a German soprano who was especially associated with German repertory. She gave memorable performances in the operas of Richard Strauss, Richard Wagner, Ludwig van Beethove ...

and Elisabeth Schumann

Elisabeth Schumann (13 June 1888 – 23 April 1952) was a German soprano who sang in opera, operetta, oratorio, and lieder. She left a substantial legacy of recordings.

Career

Born in Merseburg, Schumann trained for a singing career in B ...

made their joint débuts under his direction."Dr Otto Klemperer", ''The Times'', 9 July 1973, p. 16 His first chief conductorship was at Barmen

Barmen is a former industrial metropolis of the region of Bergisches Land, Germany, which merged with four other towns in 1929 to form the city of Wuppertal.

Barmen, together with the neighbouring town of Elberfeld founded the first elect ...

(1912–1913), after which he moved to the much larger Strasbourg Opera

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label= Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the ...

(1914–1917) as deputy to Pfitzner. From 1917 to 1924 he was chief conductor of the Cologne Opera

The Cologne Opera (German: Oper der Stadt Köln or Oper Köln) refers both to the main opera house in Cologne, Germany and to its resident opera company. History of the company

From the mid 18th century, opera was performed in the city's court th ...

. During his Cologne years he married , a singer in the opera company, in 1919. She was a Christian; he converted from Judaism.Keene, pp. 790–791 He remained a practising Roman Catholic until 1967, when he left the faith.Heyworth (1985), p. 62 The couple had two children: Werner Werner may refer to:

People

* Werner (name), origin of the name and people with this name as surname and given name

Fictional characters

* Werner (comics), a German comic book character

* Werner Von Croy, a fictional character in the ''Tomb Rai ...

, who became an actor, and Lotte, who became her father's assistant and eventually carer.

In 1923 Klemperer turned down an invitation to succeed Leo Blech as musical director of the Berlin State Opera

The (), also known as the Berlin State Opera (german: Staatsoper Berlin), is a listed building on Unter den Linden boulevard in the historic center of Berlin, Germany. The opera house was built by order of Prussian king Frederick the Great from ...

because he did not believe he would given enough artistic authority over productions.Heyworth (1985), pp. 63–65 The following year he became conductor at the Wiesbaden Opera House (1924–1927), a smaller theatre than others in which he had worked, but one where he had the control he sought over stagings. In the same year he visited Russia, conducting there during a six-week stay. He returned there each year until 1936. In 1926 he made his American début, succeeding Eugene Goossens as guest conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra. In his eight-week engagement with the orchestra he gave Mahler's Ninth Symphony and Janáček's Sinfonietta their first performances in the US.Montgomery, Paul L"Otto Klemperer, Conductor, Dead at 88"

, ''The New York Times'', 8 July 1973, p. 1

Berlin

In 1927 the authorities in Berlin decided to establish a new opera company to complement the State Opera, highlighting new works and innovative productions. The company, officially Der Staatsoper am Platz der Republik, was better known as the Kroll Opera.Leo Kestenberg

Leo Kestenberg (27 November 1882 – 13 January 1962) was a German-Israeli classical pianist, music educator, and cultural politician. Working for the government in Prussia from 1918, he began a large-scale reform of music education (''Kesten ...

, the influential head of the Prussian Ministry of Culture, proposed Klemperer as its first director. Klemperer was offered a ten-year contract and accepted it on condition that he would be allowed to conduct orchestral concerts in the theatre, and that he could employ his chosen design and stage experts.Cook, p. 2

The conductor's biographer

The conductor's biographer Peter Heyworth

Peter Lawrence Frederick Heyworth (3 June 1921 – 2 October 1991) was an American-born British music critic and biographer. He wrote a two-volume biography of Otto Klemperer and was a prominent supporter of avant-garde music.

Life and career

Pet ...

describes Klemperer's tenure at the Kroll as "of crucial significance in his career and the development of opera in the first half of the 20th century". In both concert and operatic performances Klemperer introduced much new music. Asked later which were the most important of the operas he introduced there, he listed:

In Heyworth's view, the modern approach to production at the Kroll − contrasting with conventional representational settings and costumes − exemplified in "a drastically stylised production" of ''Der fliegende Holländer

' (''The Flying Dutchman''), WWV 63, is a German-language opera, with libretto and music by Richard Wagner. The central theme is redemption through love. Wagner conducted the premiere at the Königliches Hoftheater Dresden in 1843.

Wagner ...

'' in 1929 was "a decisive forerunner of Wieland Wagner

Wieland Wagner (5 January 1917 – 17 October 1966) was a German opera director, grandson of Richard Wagner. As co-director of the Bayreuth Festival when it re-opened after World War II, he was noted for innovative new stagings of the operas, depa ...

's innovations at Bayreuth". The production divided critical opinion, which ranged from "A new outrage to a German masterpiece ... grotesque" to "an unusual and magnificent performance ... a fresh wind has blown tinsel and cobwebs away".

In 1929 Klemperer made his British début, conducting the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

in the first London performance of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony. Not all the British music critics were convinced by the symphony, but the conductor was widely praised for "the power of a dominating personality", "masterful control" and as "a great orchestral commander". One leading critic called for the BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

to give Klemperer a long-term appointment in London.

The Kroll Opera closed in 1931, ostensibly because of a financial crisis, although in Klemperer's view the motives were political. He said that Heinz Tietjen

Heinz Tietjen (24 June 1881 – 30 November 1967) was a German conductor and music producer born in Tangier, Morocco.

Biography

Tietjen was born in Tangier, Morocco. At age twenty-three, he held the position of producer at the Opera House ...

, director of the State Opera, told him that it was not, as Klemperer supposed, anti-Semitism that had worked against him: "No, that is not so important. It's your whole political and artistic direction they don't like". Klemperer's contract obliged him to transfer to the main State Opera, where with such conductors as Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger, September 15, 1876February 17, 1962) was a German-born conductor, pianist and composer. Born in Berlin, he escaped Nazi Germany in 1933, was naturalised as a French citizen in 1938, and settled in the U ...

, Wilhelm Furtwängler

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Martin Wilhelm Furtwängler ( , , ; 25 January 188630 November 1954) was a German conductor and composer. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century. He was a major ...

and Leo Blech already established, there was little important work for him. He remained there until 1933, when the rise of the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

s caused him to leave for safety in Switzerland, joined by his wife and children.

Los Angeles

In exile from Germany, Klemperer found that conducting work was far from plentiful, although he secured some prestigious engagements in Vienna and at theSalzburg Festival

The Salzburg Festival (german: Salzburger Festspiele) is a prominent festival of music and drama established in 1920. It is held each summer (for five weeks starting in late July) in the Austrian town of Salzburg, the birthplace of Wolfgang Ama ...

. He was sounded out by an American visitor influential in music in the US about becoming conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic

The Los Angeles Philharmonic, commonly referred to as the LA Phil, is an American orchestra based in Los Angeles, California. It has a regular season of concerts from October through June at the Walt Disney Concert Hall, and a summer season at th ...

in succession to Artur Rodziński

Artur Rodziński (2 January 1892 – 27 November 1958) was a Poles, Polish-Americans, American conducting, conductor of orchestral music and opera. He began his career after World War I in Second Polish Republic, Poland, where he was discovered by ...

, who was leaving to take over the Cleveland Orchestra

The Cleveland Orchestra, based in Cleveland, is one of the five American orchestras informally referred to as the " Big Five". Founded in 1918 by the pianist and impresario Adella Prentiss Hughes, the orchestra plays most of its concerts at Seve ...

. The Los Angeles orchestra was not then regarded as among the finest American ensembles, and the salary was less than Klemperer would have liked, but he accepted and sailed to the US in 1935.

The orchestra's finances were perilous. Its founder and sponsor,

The orchestra's finances were perilous. Its founder and sponsor, William Andrews Clark

William Andrews Clark Sr. (January 8, 1839March 2, 1925) was an American politician and entrepreneur, involved with mining, banking, and railroads.

Biography

Clark was born in Connellsville, Pennsylvania. He moved with his family to Iowa in 1 ...

, had lost a substantial proportion of his fortune in the Great Depression. Despite box-office constraints, Klemperer successfully introduced unfamiliar works including Mahler's ''Das Lied von der Erde

''Das Lied von der Erde'' ("The Song of the Earth") is an orchestral song cycle for two voices and orchestra written by Gustav Mahler between 1908 and 1909. Described as a symphony when published, it comprises six songs for two singers who alt ...

'' and Second Symphony, Bruckner's Fourth and Seventh Symphonies, and works by Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (6 April 1971) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor, later of French (from 1934) and American (from 1945) citizenship. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential composers of the ...

.Heyworth (1985), pp. 89–91 He programmed music from ''Gurrelieder

' is a large cantata for five vocal soloists, narrator, chorus and large orchestra, composed by Arnold Schoenberg, on poems by the Danish novelist Jens Peter Jacobsen (translated from Danish to German by ). The title means "songs of Gurre", ref ...

'' by his fellow exile and Los Angeles neighbour Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (, ; ; 13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian-American composer, music theorist, teacher, writer, and painter. He is widely considered one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. He was as ...

, although the composer complained that Klemperer did not perform his works more often. Klemperer insisted that the local public was not ready for such advanced music; Schoenberg did not bear a grudge and, as Klemperer always aspired to compose as well as to conduct, Schoenberg gave him composition lessons. Klemperer considered him "the greatest living teacher of composition, although ... he never mentioned the twelve-tone

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and (in British usage) twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer, who published his "law ...

system".Keller, p. 56 The musicologist Hans Keller

Hans (Heinrich) Keller (11 March 19196 November 1985) was an Austrian-born British musician and writer, who made significant contributions to musicology and music criticism, as well as being a commentator on such disparate fields as psychoan ...

nevertheless found "tonal varieties of the Schoenbergian method" used "penetratingly" in Klemperer's compositions.

In 1935, at Arthur Judson

Arthur Leon Judson (February 17, 1881 – January 28, 1975) was an artists' manager who also managed the New York Philharmonic and Philadelphia Orchestra and was also the founder of CBS. He co-founded the Handel Society of New York with entrepre ...

's invitation, Klemperer conducted the New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

for four weeks. The orchestra's chief conductor, Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (; ; March 25, 1867January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orche ...

, was in Europe and Klemperer took charge of the opening concerts of the season. The New York concertgoing public was deeply conservative but despite Judson's warning that programming Mahler would be highly damaging at the box-office, Klemperer insisted on giving the Second Symphony. The notices praised the conducting – Virgil Thomson

Virgil Thomson (November 25, 1896 – September 30, 1989) was an American composer and critic. He was instrumental in the development of the "American Sound" in classical music. He has been described as a modernist, a neoromantic, a neoclassi ...

wrote that the performance was the best he had heard since Mahler conducted the work in New York in 1906 – but the ticket sales were as poor as Judson had predicted, and the orchestra had a deficit of $5,000 from the concert. When Toscanini resigned from the orchestra the following year, Klemperer hoped to be considered as his successor, but realised that "after this affair of the Mahler symphony I wouldn't be engaged again".Heyworth (1985), p. 97 Nonetheless, when the little-known John Barbirolli

Sir John Barbirolli ( Giovanni Battista Barbirolli; 2 December 189929 July 1970) was a British conductor and cellist. He is remembered above all as conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, which he helped save from dissolution in 19 ...

was announced as Toscanini's successor, Klemperer wrote a vehement letter to Judson protesting at being passed over.

Having returned to Los Angeles, Klemperer conducted the orchestra's concerts there and in out-of-town venues such as San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, Santa Barbara, Fresno

Fresno () is a major city in the San Joaquin Valley of California, United States. It is the county seat of Fresno County and the largest city in the greater Central Valley region. It covers about and had a population of 542,107 in 2020, maki ...

and Claremont Claremont may refer to:

Places Australia

*Claremont, Ipswich, a heritage-listed house in Queensland

* Claremont, Tasmania, a suburb of Hobart

* Claremont, Western Australia, a suburb of Perth

** Claremont Football Club, West Australian Footba ...

. He and the orchestra worked with leading soloists, including Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel (17 April 1882 – 15 August 1951) was an Austrian-American classical pianist, composer and pedagogue. Schnabel was known for his intellectual seriousness as a musician, avoiding pure technical bravura. Among the 20th centu ...

, Emanuel Feuermann

Emanuel Feuermann (November 22, 1902 – May 25, 1942) was an internationally celebrated cellist in the first half of the 20th century.

Life

Feuermann was born in 1902 in Kolomyja, Galicia, Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Kolomyia, Ukraine) to ...

, Joseph Szigeti

Szigeti József, ; 5 September 189219 February 1973) was a Hungarian violinist.

Born into a musical family, he spent his early childhood in a small town in Transylvania. He quickly proved himself to be a child prodigy on the violin, and moved t ...

, Bronisław Huberman and Lotte Lehmann. Pierre Monteux

Pierre Benjamin Monteux (; 4 April 18751 July 1964) was a French (later American) conducting, conductor. After violin and viola studies, and a decade as an orchestral player and occasional conductor, he began to receive regular conducting enga ...

was conductor of the San Francisco Symphony

The San Francisco Symphony (SFS), founded in 1911, is an American orchestra based in San Francisco, California. Since 1980 the orchestra has been resident at the Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall in the city's Hayes Valley neighborhood. The San Fra ...

and he and Klemperer guest-conducted each other's orchestras. After a concert under Klemperer in 1936 ''The San Francisco Chronicle

The ''San Francisco Chronicle'' is a newspaper serving primarily the San Francisco Bay Area of Northern California. It was founded in 1865 as ''The Daily Dramatic Chronicle'' by teenage brothers Charles de Young and Michael H. de Young. The pap ...

s music critic hailed him as one of the world's greatest conductors, along with Furtwängler, Walter and Toscanini.

1938 to 1945

The governing board of thePittsburgh Symphony

The ''Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra'' (''PSO'') is an American orchestra based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The orchestra's home is Heinz Hall, located in Pittsburgh's Cultural District.

History

The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra is an Americ ...

approached Klemperer in early 1938, seeking his help in reconstituting the orchestra – an ''ad hoc'' group since 1927 – as a permanent ensemble. He held auditions in Pittsburgh and, more fruitfully, in New York, and after three weeks of intensive rehearsal the orchestra was ready for the opening concerts of the season, which he conducted. The results were highly successful, and he was offered a large salary to remain as the orchestra's chief conductor. He was contractually committed to Los Angeles, but contemplated taking on the direction of both orchestras. He decided against it and Fritz Reiner

Frederick Martin "Fritz" Reiner (December 19, 1888 – November 15, 1963) was a prominent conductor of opera and symphonic music in the twentieth century. Hungarian born and trained, he emigrated to the United States in 1922, where he rose to ...

was appointed as conductor in Pittsburgh.

In 1939 Klemperer began to suffer from serious balance problems. A potentially fatal brain tumour was diagnosed and he travelled to Boston for an operation to remove it. The operation was successful, but left him lame and partly paralysed on his right side. He had long had bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of depression and periods of abnormally elevated mood that last from days to weeks each. If the elevated mood is severe or associated with ...

(in the parlance of the time he was "manic depressive") and after the operation he went through an intense manic phase of the illness, which lasted for nearly three years and was followed by a long spell of severe depression.Heyworth (1985), pp. 99–100 In 1941, after he walked out of a mental sanatorium in Rye, New York

Rye is a coastal suburb of New York City in Westchester County, New York, United States. It is separate from the Rye (town), New York, Town of Rye, which has more land area than the city. The City of Rye, formerly the Village of Rye, was part o ...

, the local police put out an alarm, describing him as "dangerous and insane". He was found two days later in Morristown, New Jersey

Morristown () is a town and the county seat of Morris County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. The board of the Los Angeles orchestra terminated his contract, and his subsequent appearances were few, and seldom with prestigious ensembles. As her father struggled to support the family, Lotte worked in a factory to bring in some money.

By 1946 Klemperer had recovered his health enough to return to Europe for a conducting tour. His first concert was in Stockholm, where he met the music scholar Aládar Tóth, husband of the pianist Annie Fischer; Tóth was soon to be an important influence on his career.Heyworth (1985), pp. 100–101 On another tour in 1947 Klemperer conducted ''

By 1946 Klemperer had recovered his health enough to return to Europe for a conducting tour. His first concert was in Stockholm, where he met the music scholar Aládar Tóth, husband of the pianist Annie Fischer; Tóth was soon to be an important influence on his career.Heyworth (1985), pp. 100–101 On another tour in 1947 Klemperer conducted ''

From the mid-1950s, Klemperer's domestic base was in Zurich and his musical base in London, where his career became associated with the Philharmonia. It was widely regarded as the best orchestra in Britain in the 1950s: ''

From the mid-1950s, Klemperer's domestic base was in Zurich and his musical base in London, where his career became associated with the Philharmonia. It was widely regarded as the best orchestra in Britain in the 1950s: ''

"Klemperer the Composer"

''Tempo'', Volume 59, Issue 232, April 2005 , pp. 56–58 His compositional ideas changed after he heard Debussy's opera '' Pelléas et Mélisande'' in Prague in 1908. He later viewed the music he composed after that as his first mature works. He continued to write songs, both orchestral and with piano – there were about 100 in all – and in about 1915 he wrote two operas, ''Wehen'' (meaning "labour pains") and ''Das Ziel'' (The Goal). Neither was publicly staged, although the composer conducted a private concert performance of ''Das Ziel'' in Berlin in 1931. The "Merry Waltz" from the latter is the best-known of his compositions. Of his nine string quartets, eight survive. EMI recorded the Seventh in 1970. In 1919 he composed a

Although he did not enjoy recording, Klemperer's discography is extensive. His first recording was an acoustic set of the slow movement of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony, made for

Although he did not enjoy recording, Klemperer's discography is extensive. His first recording was an acoustic set of the slow movement of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony, made for

''Who's Who and Who Was Who'', Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007 The first movement from Klemperer's 1959 Philharmonia recording of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony was selected by

"Semyon Bychkov discusses Mahler 2"

Royal Academy of Music. Retrieved 23 December 2022

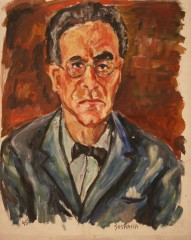

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110614075959/http://www.geh.org/ar/strip88/htmlsrc/m197701881650B_ful.html#topofimage portrait of Otto Klemperer and Johanna Geislerby

Post-war

By 1946 Klemperer had recovered his health enough to return to Europe for a conducting tour. His first concert was in Stockholm, where he met the music scholar Aládar Tóth, husband of the pianist Annie Fischer; Tóth was soon to be an important influence on his career.Heyworth (1985), pp. 100–101 On another tour in 1947 Klemperer conducted ''

By 1946 Klemperer had recovered his health enough to return to Europe for a conducting tour. His first concert was in Stockholm, where he met the music scholar Aládar Tóth, husband of the pianist Annie Fischer; Tóth was soon to be an important influence on his career.Heyworth (1985), pp. 100–101 On another tour in 1947 Klemperer conducted ''The Marriage of Figaro

''The Marriage of Figaro'' ( it, Le nozze di Figaro, links=no, ), K. 492, is a ''commedia per musica'' ( opera buffa) in four acts composed in 1786 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, with an Italian libretto written by Lorenzo Da Ponte. It pre ...

'' at the Salzburg Festival and ''Don Giovanni

''Don Giovanni'' (; K. 527; Vienna (1788) title: , literally ''The Rake Punished, or Don Giovanni'') is an opera in two acts with music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an Italian libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. Its subject is a centuries-old Spani ...

'' in Vienna. While he was in Salzburg, Tóth, who had been appointed director of the Hungarian State Opera in Budapest, invited him to become the company's musical director. Klemperer accepted, and served from 1947 to 1950. In Budapest he conducted the major Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

operas and ''Fidelio

''Fidelio'' (; ), originally titled ' (''Leonore, or The Triumph of Marital Love''), Op. 72, is Ludwig van Beethoven's only opera. The German libretto was originally prepared by Joseph Sonnleithner from the French of Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, w ...

'', ''Tannhäuser

Tannhäuser (; gmh, Tanhûser), often stylized, "The Tannhäuser," was a German Minnesinger and traveling poet. Historically, his biography, including the dates he lived, is obscure beyond the poetry, which suggests he lived between 1245 and ...

'', ''Lohengrin

Lohengrin () is a character in German Arthurian literature. The son of Parzival (Percival), he is a knight of the Holy Grail sent in a boat pulled by swans to rescue a maiden who can never ask his identity. His story, which first appears in Wolf ...

'' and '' Die Meistersinger'', as well as works from the Italian repertory, and many concerts.

Klemperer made his first post-war appearance in London in March 1948, conducting the Philharmonia Orchestra

The Philharmonia Orchestra is a British orchestra based in London. It was founded in 1945 by Walter Legge, a classical music record producer for EMI. Among the conductors who worked with the orchestra in its early years were Richard Strauss, ...

, the orchestra with which he was later most closely associated. He conducted Bach's Third Orchestral Suite from the harpsichord

A harpsichord ( it, clavicembalo; french: clavecin; german: Cembalo; es, clavecín; pt, cravo; nl, klavecimbel; pl, klawesyn) is a musical instrument played by means of a musical keyboard, keyboard. This activates a row of levers that turn a ...

, Stravinsky's Symphony in Three Movements

The Symphony in Three Movements is a work by Russian expatriate composer Igor Stravinsky. Stravinsky wrote the symphony from 1942–45 on commission by the Philharmonic Symphony Society of New York. It was premièred by the New York Philharmon ...

and Beethoven's ''Eroica'' Symphony.

In 1950 Klemperer left the Budapest post, frustrated by the political interference of the communist regime. He held no permanent conductorship for the next nine years. In the early 1950s he freelanced in Argentina, Australia, Austria, Britain, Canada, France, Germany and elsewhere.Heyworth (1985), p. 103 In London in 1951 he conducted two Philharmonia concerts at the new Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,700-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge, in the London Borough of Lambeth. It is a Grade I l ...

, eliciting high praise from reviewers. The music critic of ''The Times'' wrote:

After this, Klemperer's seemingly resurgent career received another severe set-back. At Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

airport later in 1951 he slipped on ice and fell, breaking his hip. He was hospitalised for eight months. Then for a year he and his family were, as he put it, virtually prisoners in the US because of new legislation. He had taken American citizenship in 1940 and held an American passport since then; under the new law the authorities refused to renew his and his family's passports. With the help of an accomplished lawyer, Klemperer secured temporary six-month passports in 1954. He moved with his wife and daughter to Switzerland, settled in Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Zürich () i ...

, and obtained German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

citizenship and passports.

London

From the mid-1950s, Klemperer's domestic base was in Zurich and his musical base in London, where his career became associated with the Philharmonia. It was widely regarded as the best orchestra in Britain in the 1950s: ''

From the mid-1950s, Klemperer's domestic base was in Zurich and his musical base in London, where his career became associated with the Philharmonia. It was widely regarded as the best orchestra in Britain in the 1950s: ''Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians

''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' is an encyclopedic dictionary of music and musicians. Along with the German-language ''Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart'', it is one of the largest reference works on the history and theor ...

'' described it as "an elite whose virtuosity transformed British concert life", and ''The Times'' called it "the Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated ...

of British orchestras". Its founder and proprietor, Walter Legge

Harry Walter Legge (1 June 1906 – 22 March 1979) was an English classical music record producer, most especially associated with EMI. His recordings include many sets later regarded as classics and reissued by EMI as "Great Recordings of the ...

, engaged a range of prominent conductors for his concerts. By the early 1950s the most closely identified with the orchestra was Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan (; born Heribert Ritter von Karajan; 5 April 1908 – 16 July 1989) was an Austrian conductor. He was principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic for 34 years. During the Nazi era, he debuted at the Salzburg Festival, wi ...

, but he was clearly the heir apparent to the ailing Furtwängler as chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic

The Berlin Philharmonic (german: Berliner Philharmoniker, links=no, italic=no) is a German orchestra based in Berlin. It is one of the most popular, acclaimed and well-respected orchestras in the world.

History

The Berlin Philharmonic was fo ...

and the Salzburg Festival; anticipating that Karajan would become unavailable to the Philharmonia, Legge built up a relationship with Klemperer, who was admired by the players, the critics and the public.

Legge was a senior producer for Columbia

Columbia may refer to:

* Columbia (personification), the historical female national personification of the United States, and a poetic name for America

Places North America Natural features

* Columbia Plateau, a geologic and geographic region in ...

, part of the EMI recording group. As Columbia paid for the rehearsals for recordings, Legge's concerts tended to feature works he had recorded immediately beforehand, so that the orchestra was fully rehearsed at no cost to him. This suited Klemperer, who though he disliked making recordings enjoyed the luxury of "hav ngtime to prepare a work properly".

According to the critic William Mann William Mann may refer to:

*William Mann (astronomer) (1817–1873), English astronomer active in the Cape Colony

*William Mann (MP), English politician in the House of Commons, 1621–1625

*William Mann (settler) (1610–1650), original settler of ...

, Klemperer's repertory by now was:

In 1957 Legge launched the Philharmonia Chorus, which made its debut in Beethoven's Choral Symphony

A choral symphony is a musical composition for orchestra, choir, and sometimes solo vocalists that, in its internal workings and overall musical architecture, adheres broadly to symphonic musical form. The term "choral symphony" in this conte ...

conducted by Klemperer. In ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper Sunday editions, published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group, Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. ...

'' Heyworth wrote that with "what promises to be our best choir ndour best orchestra and a great conductor", Legge had given London "a Beethoven cycle that any city in the world, be it Vienna or New York, would envy".

Wieland Wagner invited Klemperer to conduct ''Tristan und Isolde

''Tristan und Isolde'' (''Tristan and Isolde''), WWV 90, is an opera in three acts by Richard Wagner to a German libretto by the composer, based largely on the 12th-century romance Tristan and Iseult by Gottfried von Strassburg. It was compos ...

'' at the 1959 Holland Festival

The Holland Festival () is the oldest and largest performing arts festival in the Netherlands. It takes place every June in Amsterdam. It comprises theatre, music, opera and modern dance. In recent years, multimedia, visual arts, film and archit ...

, and they agreed to collaborate on ''Die Meistersinger'' at Bayreuth, but neither plan was realised, because Klemperer suffered a further physical setback: in October 1958 while smoking in bed he set his bedclothes alight. His burns were life-threatening, and his recovery slow. It was not for nearly a year, until September 1959, that he recovered his health enough to conduct again. On Klemperer's return to the Philharmonia, Legge stood before the orchestra and appointed him conductor for life – the Philharmonia's first principal conductor. Klemperer's concerts in the 1960s included more works from outside the core German repertory, including Bartók's Divertimento

''Divertimento'' (; from the Italian '' divertire'' "to amuse") is a musical genre, with most of its examples from the 18th century. The mood of the '' divertimento'' is most often lighthearted (as a result of being played at social functions) and ...

, and symphonies by Berlioz, Dvořák, Mahler and Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most pop ...

.

Klemperer returned to opera in 1961, making his Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

début in ''Fidelio'' for which he directed the staging as well as the music. He had to a considerable extent moved away from the experimental stagings of the Kroll years, and the 1961 ''Fidelio'' was described as "traditional, unfussy, grandly conceived, and profoundly revealing", musically of "deep serenity". Klemperer directed and conducted another ''Fidelio'' in Zurich the following year, at the opera house

An opera house is a theater (structure), theatre building used for performances of opera. It usually includes a Stage (theatre), stage, an orchestra pit, audience seating, and backstage facilities for costumes and building sets.

While some venu ...

, only a few hundred yards from his home. He battled with entrenched interests in the Zurich orchestra to secure the best players, but he succeeded and the performances were well received. At Covent Garden he later directed and conducted two more new productions: ''Die Zauberflöte

''The Magic Flute'' (German: , ), K. 620, is an opera in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to a German libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder. The work is in the form of a '' Singspiel'', a popular form during the time it was written that inc ...

'' (1962), and ''Lohengrin'' (1963), neither of which was as well received as ''Fidelio''.

Later years

During the early 1960s Legge became disenchanted with the orchestral music scene. His freedom to programme what he pleased was hampered by new committees at the Festival Hall and EMI, and his orchestra was less in demand in the studios. In March 1964, with no advance warning to the orchestra, he issued a press statement announcing that "after the fulfilment of its present commitments the activities of the Philharmonia Orchestra will be suspended for an indefinite period." Klemperer said that Legge had not warned him beforehand of the announcement, although Legge later maintained that he had done so. With Klemperer's strong support the players refused to be disbanded and formed themselves into a self-governing ensemble as the New Philharmonia Orchestra (NPO). They elected him as their president. He remained in the position until his retirement eight years later. In his later years Klemperer returned to the Jewish faith, and was a strong supporter of the state of Israel. He visited his younger sister, who lived there, and while in Jerusalem in 1970 he accepted the offer of Israeli citizenship, though continuing to retain his German citizenship and permanent Swiss residency. As Klemperer aged, his concentration and control of the orchestra declined. At one recording session he dozed off while conducting, and he found his hearing and eyesight under strain from concentrating for the length of a concert. One of his players toldAndré Previn

André George Previn (; born Andreas Ludwig Priwin; April 6, 1929 – February 28, 2019) was a German-American pianist, composer, and conductor. His career had three major genres: Hollywood films, jazz, and classical music. In each he achieve ...

, "Sadly, he got a bit deaf and shaky. You'd be thinking 'poor old Klemperer', then suddenly the veil of infirmity would drop and he'd be wonderfully vigorous again.Previn, p. 159 Klemperer continued to conduct and record with the New Philharmonia until the last concert of his career – which took place at the Festival Hall on 26 September 1971 – and his final recording session two days later. The programme for the concert was Beethoven's ''King Stephen'' overture, and Fourth Piano Concerto, with Daniel Adni as soloist, and Brahms's Third Symphony. The recording, with the orchestra's wind players, was of Mozart's Serenade No. 11 in E flat, K. 375.

The following January, after flying from Zurich to London to conduct Bruckner's Seventh Symphony, Klemperer announced the day before the concert that he could no longer cope with the strain of public performances."Klemperer stands down", ''The Times'', 21 January 1971, p. 8 He hoped to be able to go on making recordings, as he felt he might be able to manage the shorter spans of recording takes, and intended to conduct Mozart's ''Die Entführung aus dem Serail

' () ( K. 384; ''The Abduction from the Seraglio''; also known as ') is a singspiel in three acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The German libretto is by Gottlieb Stephanie, based on Christoph Friedrich Bretzner's ''Belmont und Constanze, oder D ...

'' and Bach's ''St John Passion

The ''Passio secundum Joannem'' or ''St John Passion'' (german: Johannes-Passion, link=no), BWV 245, is a Passion or oratorio by Johann Sebastian Bach, the older of the surviving Passions by Bach. It was written during his first year as dire ...

'' for EMI, but neither plan came to fruition.

Heyworth writes about the conductor's last years:

Klemperer retired to his home in Zurich, where he died in his sleep on 6 July 1973. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery at Friesenberg, Zurich, four days later.

Compositions

Klemperer said, "I am mainly a conductor who also composes. Naturally, I would be glad to be remembered as a conductor and as a composer". German conductors of his generation began their careers when it was rare for a conductor not to compose: composition was seen as part of the traditional training of akapellmeister

(, also , ) from German ''Kapelle'' (chapel) and ''Meister'' (master)'','' literally "master of the chapel choir" designates the leader of an ensemble of musicians. Originally used to refer to somebody in charge of music in a chapel, the term ha ...

. He began composing at an early age, and started writing songs in his mid-teens.Walton, Chris"Klemperer the Composer"

''Tempo'', Volume 59, Issue 232, April 2005 , pp. 56–58 His compositional ideas changed after he heard Debussy's opera '' Pelléas et Mélisande'' in Prague in 1908. He later viewed the music he composed after that as his first mature works. He continued to write songs, both orchestral and with piano – there were about 100 in all – and in about 1915 he wrote two operas, ''Wehen'' (meaning "labour pains") and ''Das Ziel'' (The Goal). Neither was publicly staged, although the composer conducted a private concert performance of ''Das Ziel'' in Berlin in 1931. The "Merry Waltz" from the latter is the best-known of his compositions. Of his nine string quartets, eight survive. EMI recorded the Seventh in 1970. In 1919 he composed a

Missa Sacra

Mass is the main Eucharistic liturgical service in many forms of Western Christianity. The term ''Mass'' is commonly used in the Catholic Church, in the Western Rite Orthodox, in Old Catholic, and in Independent Catholic churches. The term is ...

for soloists, chorus and orchestra, and also a setting of Psalm 23

Psalm 23 is the 23rd psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "The Lord is my shepherd". In Latin, it is known by the incipit, "". The Book of Psalms is part of the third section of the Hebrew Bible, and a b ...

.

Klemperer gave the premiere of his First Symphony with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam in 1961, and that of the final version of his Second with the New Philharmonia in 1969, recording it for EMI a few weeks later. He wrote a total of six symphonies. Harold Schonberg, music critic of ''The New York Times'', said that the First Symphony, with its incorporation of the ''Marseillaise

"La Marseillaise" is the national anthem of France. The song was written in 1792 by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle in Strasbourg after the declaration of war by France against Austria, and was originally titled "Chant de guerre pour l'Armée du R ...

'' in the second movement, "sounded like Charles Ives in one of his wilder moments". When the recording of the Second Symphony was issued in 1970, the critic Edward Greenfield

Edward Harry Greenfield OBE (3 July 1928 – 1 July 2015) was an English music critic and broadcaster.

Early life

Edward Greenfield was born in Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex. His father, Percy Greenfield, was a manager in a labour exchange, while his ...

wrote, "There is a gritty quality about much of Klemperer's fast music ithsharp-edged unison passages ... but give Klemperer a slow tempo and he will melt with amazing rapidity ... the slow movement is astonishingly sweet, with one passage – clarinet over pizzicato strings – recalling the world of Lehár or even Viennese café music". The critic Meirion Bowen wrote of the same work that it was "the product of an outstanding conductor musing on the works of composers he has championed throughout his career".

Recordings

Although he did not enjoy recording, Klemperer's discography is extensive. His first recording was an acoustic set of the slow movement of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony, made for

Although he did not enjoy recording, Klemperer's discography is extensive. His first recording was an acoustic set of the slow movement of Bruckner's Eighth Symphony, made for Polydor

Polydor Records Ltd. is a German-British record label that operates as part of Universal Music Group. It has a close relationship with Universal's Interscope Geffen A&M Records label, which distributes Polydor's releases in the United States. ...

in 1924 with the Orchestra of the Staatskapelle, Berlin. His early recordings include Beethoven symphonies and less characteristic repertoire including the first recording of Ravel's ''Alborada del gracioso

''Alborada del gracioso'' ("The Jester's Aubade", or other translations: see below) is a short orchestral piece by Maurice Ravel first performed in 1919. It is an orchestrated version of one of the five movements of his piano suite ''Miroirs'', ...

'', and "Nuages" and "Fêtes" from Debussy's '' Nocturnes'' (1926). Then, in between recordings of mostly German classics – including works by Brahms, Bruckner, Mendelssohn, Schubert, Richard Strauss and Wagner – he ventured into the light French repertoire with the overtures to '' Fra Diavolo'' and ''La belle Hélène

''La belle Hélène'' (, ''The Beautiful Helen'') is an opéra bouffe in three acts, with music by Jacques Offenbach and words by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy. The piece parodies the story of Helen's elopement with Paris, which set off the ...

'' (1929).

From the Los Angeles years there is only one purpose-made studio recording but several transcriptions of live radio broadcasts, ranging from symphonies by Beethoven, Bruckner and Dvořák to excerpts from operas by Gounod, Massenet, Puccini and Verdi. Similarly, there are no commercial studio recordings from Klemperer's time in Budapest, but live performances in the opera house or on air were recorded and have been issued on CD, including complete sets of ''Lohengrin'', ''Fidelio'', ''The Magic Flute'', ''The Tales of Hoffmann

''The Tales of Hoffmann'' (French: ) is an by Jacques Offenbach. The French libretto was written by Jules Barbier, based on three short stories by E. T. A. Hoffmann, who is the protagonist of the story. It was Offenbach's final work; he died i ...

'', ''Die Meistersinger'' and ''Così fan tutte

(''All Women Do It, or The School for Lovers''), K. 588, is an opera buffa in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. It was first performed on 26 January 1790 at the Burgtheater in Vienna, Austria. The libretto was written by Lorenzo Da Ponte ...

'', all sung in Hungarian.

For the Vox label Klemperer recorded several sets in Vienna in 1951, including Beethoven's Missa solemnis

{{Audio, De-Missa solemnis.ogg, Missa solemnis is Latin for Solemn Mass, and is a genre of musical settings of the Mass Ordinary, which are festively scored and render the Latin text extensively, opposed to the more modest Missa brevis. In Frenc ...

praised by Legge as "grave and powerful". During the 1950s many live broadcasts conducted by Klemperer were recorded, and later published on CD, with orchestras including the Bavarian Radio Symphony, Concertgebouw

The Royal Concertgebouw ( nl, Koninklijk Concertgebouw, ) is a concert hall in Amsterdam, Netherlands. The Dutch term "concertgebouw" translates into English as "concert building". Its superb acoustics place it among the finest concert halls ...

, Cologne Radio Symphony, RIAS Symphony, Berlin and the Vienna Symphony

The Vienna Symphony (Vienna Symphony Orchestra, german: Wiener Symphoniker) is an Austrian orchestra based in Vienna. Its primary concert venue is the Vienna Konzerthaus. In Vienna, the orchestra also performs at the Musikverein and at the Thea ...

.

In October 1954 Klemperer made the first of his many recordings with the Philharmonia: Mozart's ''Jupiter'' Symphony. ("Extremely impressive ... epic", commented ''The Gramophone

''Gramophone'' is a magazine published monthly in London, devoted to classical music, particularly to reviews of recordings. It was founded in 1923 by the Scottish author Compton Mackenzie who continued to edit the magazine until 1961. It was ...

'', "carried through unfalteringly to the end.") Between then and 1972 he conducted the orchestra, and its successor, the New Philharmonia, in recordings of nearly two hundred different works. With the original Philharmonia they included more Mozart symphonies, complete symphony cycles of Beethoven and Brahms, symphonies by Berlioz, Mendelssohn, Schubert, Schumann, Bruckner, Dvořák, Tchaikovsky and Mahler, and other orchestral works by, among others, Bach, Johann Strauss

Johann Baptist Strauss II (25 October 1825 – 3 June 1899), also known as Johann Strauss Jr., the Younger or the Son (german: links=no, Sohn), was an Austrian composer of light music, particularly dance music and operettas. He composed ov ...

, Richard Strauss, Stravinsky, Wagner and Weill."Discography", Heyworth (1996, Vol 2), pp. 405−439

From the choral repertoire he and the Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra recorded Bach's ''St Matthew Passion

The ''St Matthew Passion'' (german: Matthäus-Passion, links=-no), BWV 244, is a '' Passion'', a sacred oratorio written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1727 for solo voices, double choir and double orchestra, with libretto by Picander. It sets ...

'', Handel's ''Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

'' and Brahms's '' German Requiem''. His complete opera recordings with the Philharmonia were ''Fidelio'' and ''The Magic Flute''. Solo singers in these recordings included Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (28 May 1925 – 18 May 2012) was a German lyric baritone and conductor of classical music, one of the most famous Lieder (art song) performers of the post-war period, best known as a singer of Franz Schubert's Lieder, ...

, Gottlob Frick, Christa Ludwig

Christa Ludwig (16 March 1928 – 24 April 2021) was a German mezzo-soprano and occasional dramatic soprano, distinguished for her performances of opera, lieder, oratorio, and other major religious works like masses, passions, and solos in sym ...

, Peter Pears

Sir Peter Neville Luard Pears ( ; 22 June 19103 April 1986) was an English tenor. His career was closely associated with the composer Benjamin Britten, his personal and professional partner for nearly forty years.

Pears' musical career started ...

, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

Dame Olga Maria Elisabeth Friederike Schwarzkopf, (9 December 19153 August 2006) was a German-born Austro-British soprano. She was among the foremost singers of lieder, and is renowned for her performances of Viennese operetta, as well as the op ...

and Jon Vickers

Jonathan Stewart Vickers, (October 29, 1926 – July 10, 2015), known professionally as Jon Vickers, was a Canadian heldentenor.

Born in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, he was the sixth in a family of eight children. In 1950, he was awarded a sc ...

.

After the players reconstituted themselves as the New Philharmonia in 1964 Klemperer worked extensively with them in the studios, recording eight symphonies by Haydn, three by Schumann, four by Bruckner and two by Mahler. A complete Beethoven piano concerto cycle featured Daniel Barenboim

Daniel Barenboim (; in he, דניאל בארנבוים, born 15 November 1942) is an Argentine-born classical pianist and conductor based in Berlin. He has been since 1992 General Music Director of the Berlin State Opera and "Staatskapellmeist ...

as soloist. The major choral recordings were of Beethoven's Missa solemnis and Bach's B minor Mass. Reviewing the former, Alec Robertson wrote that it "must take its place on the heights among the greatest recordings of our time". The Bach set divided critical opinion: Robertson called it "a spiritual experience ... a glorious achivement"; the '' Stereo Record Guide'', though conceding "the majesty of Klemperer's conception", found it "disappointing ... with plodding tempi". There were four complete operas: ''Così fan tutte'', ''Don Giovanni'', ''Der fliegende Holländer'' and ''The Marriage of Figaro''. Soloists included, among the women, Janet Baker

Dame Janet Abbott Baker (born 21 August 1933) is an English mezzo-soprano best known as an opera, concert, and lieder singer.Blyth, Alan, "Baker, Dame Janet (Abbott)" in Sadie, Stanley, ed.; John Tyrell; exec. ed. (2001). ''New Grove Dictionar ...

, Teresa Berganza

Teresa Berganza Vargas OAXS (16 March 1933 – 13 May 2022) was a Spanish mezzo-soprano. She is most closely associated with roles such as Rossini's Rosina and La Cenerentola, and later Bizet's Carmen, admired for her technical virtuosity, ...

, Mirella Freni

Mirella Freni, OMRI (, born Mirella Fregni, 27 February 1935 – 9 February 2020) was an Italian operatic soprano who had a career of 50 years and appeared at major international opera houses. She received international attention at the ...

, Anja Silja

Anja Silja Regina Langwagen (, born 17 April 1940) is a German soprano singer.

Biography

Born in Berlin, Silja began her operatic career at a very early age, with her grandfather, Egon Friedrich Maria Anders van Rijn, as her voice teacher. Sh ...

and Elisabeth Söderström, and among the men, Theo Adam

Theo Adam (1 August 1926 – 10 January 2019) was a German operatic bass-baritone and bass singer who had an international career in opera, concert and recital from 1949. He was a member of the Staatsoper Dresden for his entire career, and sang ...

, Gabriel Bacquier, Geraint Evans

Sir Geraint Llewellyn Evans (16 February 1922 – 19 September 1992) was a Welsh bass-baritone noted for operatic roles including Figaro in ''Le nozze di Figaro'', Papageno in ''Die Zauberflöte'', and the title role in ''Wozzeck''. Evans was esp ...

, Nicolai Gedda

Harry Gustaf Nikolai Gädda, known professionally as Nicolai Gedda (11 July 1925 – 8 January 2017), was a Swedish operatic tenor. Debuting in 1951, Gedda had a long and successful career in opera until the age of 77 in June 2003, when he made h ...

and Nicolai Ghiaurov.

Honours, reputation and legacy

Honours

In 1933 Klemperer was presented with theGoethe Medal

The Goethe Medal, also known as the Goethe-Medaille, is a yearly prize given by the Goethe-Institut honoring non-Germans "who have performed outstanding service for the German language and for international cultural relations". It is an offici ...

by President Hindenburg in Berlin. He was awarded the Leipzig Orchestral Nikisch Prize in 1966, and held honorary degrees from Occidental College

Occidental College (informally Oxy) is a private liberal arts college in Los Angeles, California. Founded in 1887 as a coeducational college by clergy and members of the Presbyterian Church, it became non-sectarian in 1910. It is one of the oldes ...

and the University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a Normal school, teachers colle ...

. In 1971 he was appointed an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is the oldest conservatoire in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the first Duke ...

in London. From Germany he held the Grand Medal of Merit with Star (1958) and the Order of Merit (1967)."Klemperer, Otto"''Who's Who and Who Was Who'', Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007 The first movement from Klemperer's 1959 Philharmonia recording of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony was selected by

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedi ...

for inclusion on the Voyager Golden Record

The Voyager Golden Records are two phonograph records that were included aboard both Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. The records contain sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth, and are intended fo ...

, sent into space on the Voyager space craft. The record contained sounds and images selected as examples of the diversity of life and culture on Earth.

Reputation

''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

s music critic Joseph McLellan Joseph Duncan McLellan, known as Joe, (1929-2005) was ''The Washington Posts music critic for more than three decades as well as a chess and book reviewer.

Joe was born in Quincy, Massachusetts, on March 27, 1929, and grew up in Somerville, Mass ...

wrote when Klemperer died, "An age of giants has ended ... They are all gone: Toscanini, Walter, Furtwängler, Beecham, Szell, Reiner, and, now Klemperer". ''The Times'' said that in Britain he had been revered as the greatest of living conductors. In the view of ''Grove's Dictionary'', following Toscanini’s retirement in April 1954 and Furtwängler’s death seven months later, Klemperer was "generally accepted as the most authoritative interpreter of the central Austro-German repertory".

It was as a Beethoven conductor that Klemperer became most celebrated. A Philharmonia player said, "It's as though Beethoven himself were standing there"."As though Beethoven himself were standing there", ''Saturday Review'', 14 October 1961, p. 89 and the orchestra's first horn, Alan Civil

Alan Civil OBE (13 June 1929 – 19 March 1989) was a British horn player.

Civil began to play the horn at a young age, and joined the famous Royal Artillery Band and Orchestra at Woolwich, while still in his teens. He studied the instrument ...

, said, "It took a Klemperer to throw fresh light on Beethoven, and I found his Beethoven cycles marvellous. I mean, I don’t want to play Beethoven with any other conductor". '' The Record Guide'' said of the 1951 recording of the ''Missa solemnis'', "it is seldom that we hear in the concert hall a performance so clear, so fervent and so musical as that which Klemperer has achieved ... iththe impression of sublimity achieved by this splendid performance". Of his contemporaneous recording of the Fifth Symphony, the same writers called it "a really individual reading", preferable to those of Toscanini, Walter or Erich Kleiber

Erich Kleiber (5 August 1890 – 27 January 1956) was an Austrian, later Argentine, conductor, known for his interpretations of the classics and as an advocate of new music.

Kleiber was born in Vienna, and after studying at the Prague Conservat ...

: "Klemperer treats the work as if he had just discovered its greatness, illuminating every page with a ceaseless care for detail". William Mann wrote of the 1962 recording of ''Fidelio'', "the performance is so stunning that after it operagoers may almost despair of hearing a ''Fidelio'' that will not prove a disappointment".

Many musicians disagreed with his way of conducting Mozart. Sir Neville Cardus of ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide ...

'' observed, "It was not for him the gallant Mozart presented by Sir Thomas Beecham; far from it. Klemperer's Mozart was made of sterner stuff". Mann complained that the conductor's direction of ''Le nozze di Figaro'' was "didactic, humourless, tortoise-like", though his colleague Stanley Sadie

Stanley John Sadie (; 30 October 1930 – 21 March 2005) was an influential and prolific British musicology, musicologist, music critic, and editor. He was editor of the sixth edition of the ''Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians'' (1980), whi ...

found "Klemperer's leisured, cool, almost dispassionate view of the opera is not without its attractiveness. ... The deliberation and the poise are not what we are used to in ''Figaro'', and they say something about it which is worth hearing". It was not only in Mozart that Klemperer's tempi attracted adverse comment: a frequent criticism in his later years was that his tempi were slow. The EMI producer Suvi Raj Grubb Suvi Raj Grubb (7 October 191722 December 1999) was a South-Indian record producer who worked for EMI during the mid-20th Century, initially as assistant to Walter Legge, succeeding Legge on his resignation from EMI in 1964. He was accounted one ...

wrote:

Cardus expressed regret that Klemperer had too rarely been allowed to programme Bruckner, "whose symphonies he encompassed with a grip and a vision which saw the end of a large musical shape in the beginning".Cardus, Neville. "The Interpreter", ''The Guardian'', 9 July 1973, p. 8 Cardus added:

Legacy

In 1973 Lotte Klemperer presented theRoyal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is the oldest conservatoire in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the first Duke ...

with a collection of her father's books and marked-up scores, together with a portrait and some of his batons. This is now known as the Otto Klemperer Collection. One of the academy's two named professorships in conducting is the Klemperer Chair (currently, at 2022, held by Semyon Bychkov).Royal Academy of Music. Retrieved 23 December 2022

Notes, references and sources

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

** ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110614075959/http://www.geh.org/ar/strip88/htmlsrc/m197701881650B_ful.html#topofimage portrait of Otto Klemperer and Johanna Geislerby

Nickolas Muray

Nickolas Muray (born Miklós Mandl; 15 February 1892 – 2 November 1965) was a Hungarian-born American photographer and Olympic saber fencer.

Early and personal life

Muray was born in Szeged, Hungary, and was Jewish. His father Samu Mandl was ...

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Klemperer, Otto

1885 births

1973 deaths

American people of Czech-Jewish descent

American male conductors (music)

20th-century American conductors (music)

Berlin University of the Arts alumni

German male classical composers

German classical composers

Knights Commander of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

German conductors (music)

German male conductors (music)

Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United States

Jewish classical musicians

Jewish classical composers

Naturalized citizens of Israel

Musicians from Wrocław

People from the Province of Silesia

People with bipolar disorder

Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

Honorary Members of the Royal Academy of Music

Hoch Conservatory alumni

American male classical composers

American classical composers

20th-century American composers

20th-century American male musicians

Music Academy of the West founders

Naturalized citizens of the United States

American people of Sephardic-Jewish descent

American people of Bohemian descent

American people of German-Jewish descent

Prussian emigrants to the United States

19th-century Prussian people