Oskar Vogt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Oskar Vogt (6 April 1870, in

Oskar Vogt (6 April 1870, in

Femininity and Science: The Brain Researcher Cécile Vogt (1875-1962)

. Translation of: Weiblichkeit und Wissenschaft. In: Bleker, Johanna (ed.): Der Eintritt der Frauen in die Gelehrtenrepublik. Husum, 1998, 75-93. As a clinician, Vogt used

The contributions of the Vogts are of the first order as their work applies to several parts of the brain and had a considerable influence on international neurological sciences.

The contributions of the Vogts are of the first order as their work applies to several parts of the brain and had a considerable influence on international neurological sciences.

WhonameditWhonamedit? Cécile Vogt, (born Mugnier

WhonameditWhonamedit? Vogt-Vogt syndrom

Whonamedit

File:Hans Scheib - Büste Oskar Vogt.jpg, Bronze bust of Oskar Vogt located in the biomedical Berlin-Buch Campus at the former Institute for Brain Research.

File:Axel Schulz - Gedenktafel für Oskar und Cécile Vogt.jpg, Plaque for Oskar and Cécile Vogt on the building of the Institute for Brain Research in Berlin-Buch. The plaque was created in 1965 by sculptor Axel Schulz.

Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Vogt, Oskar 1870 births 1959 deaths People from Husum German neurologists Members of the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin German expatriates in the Soviet Union Max Planck Institute directors

Husum

Husum (, frr, Hüsem) is the capital of the ''Kreis'' (district) Nordfriesland in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. The town was the birthplace of the novelist Theodor Storm, who coined the epithet "the grey town by the sea". It is also the home of ...

– 30 July 1959, in Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic German, Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population o ...

) was a German physician and neurologist

Neurology (from el, νεῦρον (neûron), "string, nerve" and the suffix -logia, "study of") is the branch of medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of all categories of conditions and disease involving the brain, the spinal c ...

. He and his wife Cécile Vogt-Mugnier

Cécile Vogt-Mugnier (27 March 1875 – 4 May 1962) was a French neurologist from Haute-Savoie. She and her husband Oskar Vogt are known for their extensive cytoarchetectonic studies on the brain.

Professional life

Education and career

Vogt-M ...

are known for their extensive cytoarchetectonic studies on the brain

A brain is an organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as vision. It is the most complex organ in a v ...

.

Personal life

He was born inHusum

Husum (, frr, Hüsem) is the capital of the ''Kreis'' (district) Nordfriesland in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. The town was the birthplace of the novelist Theodor Storm, who coined the epithet "the grey town by the sea". It is also the home of ...

, Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sch ...

, Germany. Vogt studied medicine at Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

and Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, while the city itself has a popu ...

, obtaining his doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

from Jena in 1894.

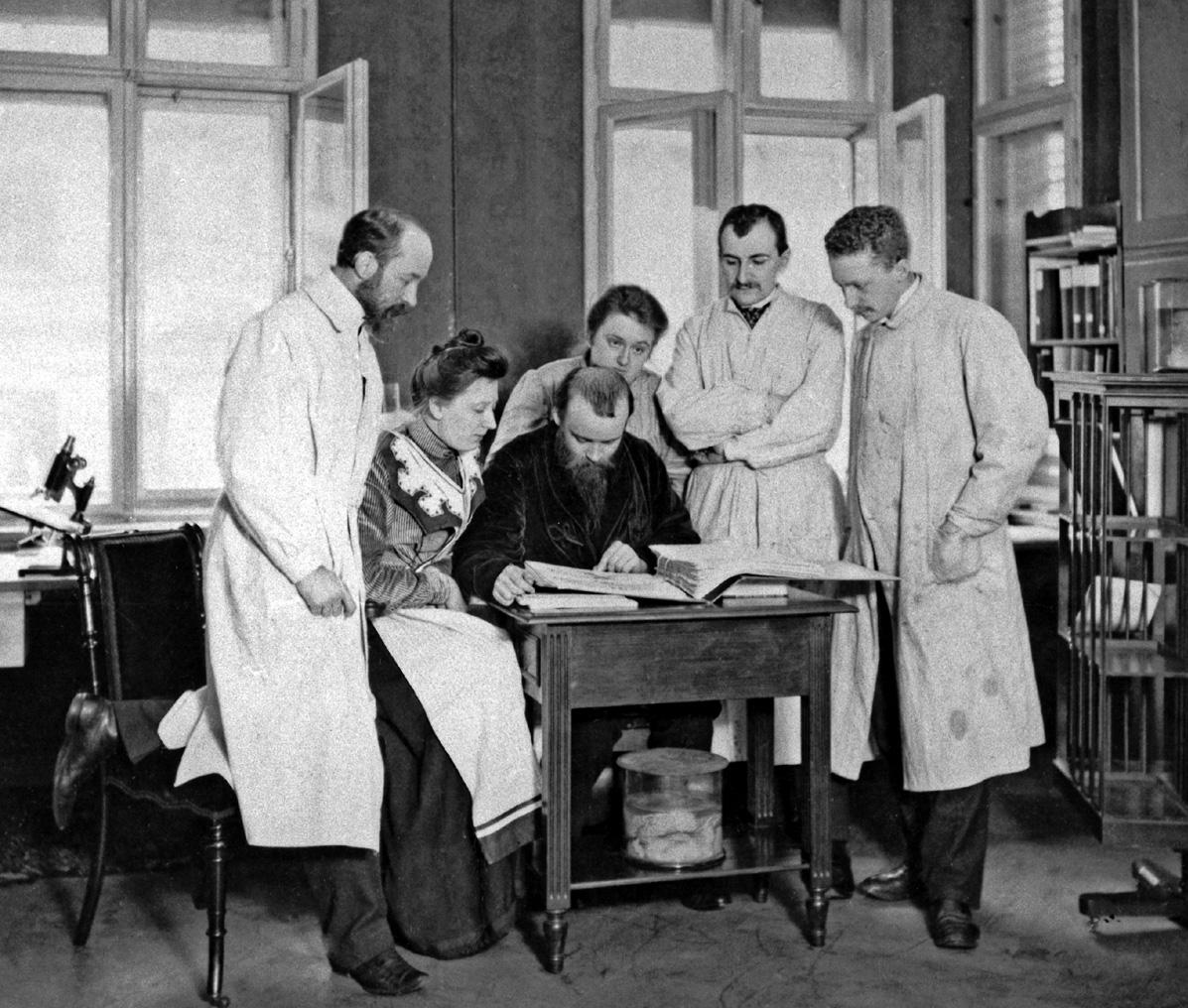

The Vogts met in 1897 in Paris, and eventually married in 1899. The Vogts were close to the Krupp

The Krupp family (see pronunciation), a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG (Friedrich Krup ...

family. Friedrich Alfred Krupp

Friedrich Alfred Krupp (17 February 1854 – 22 November 1902) was a German steel manufacturer and head of the company Krupp. He was the son of Alfred Krupp and inherited the family business when his father died in 1887. Whereas his father had ...

financially supported them, and in 1898, Oskar and Cécile founded a private research institute called the ''Neurologische Zentralstation'' (Neurological Center) in Berlin, which was formally associated with the Physiological Institute of the Charité

The Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin (Charité – Berlin University of Medicine) is one of Europe's largest university hospitals, affiliated with Humboldt University and Free University Berlin. With numerous Collaborative Research Cen ...

as the Neurobiological Laboratory of the Berlin University

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative o ...

in 1902. This institute served as the basis for the 1914 formation of the ''Kaiser Institut für Hirnforschung'' (Kaiser Wilhelm Institute

The Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science (German: ''Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften'') was a German scientific institution established in the German Empire in 1911. Its functions were taken over by ...

for Brain Research), of which Oskar was a director. There, he had students from many countries who went on to prominent careers including Jerzy Rose

Jerzy is the Polish version of the masculine given name George. The most common nickname for Jerzy is Jurek (), which may also be used as an official first name. Occasionally the nickname Jerzyk may be used, which means "swift" in Polish.

People

...

(mentor of Michael Merzenich

Michael Matthias Merzenich ( ; born 1942 in Lebanon, Oregon) is an American neuroscientist and professor emeritus at the University of California, San Francisco. He took the sensory cortex maps developed by his predecessors (Archie Tunturi, Clinto ...

), Valentino Braitenberg

Valentino Braitenberg (or ''Valentin von Braitenberg''; 18 June 1926 – 9 September 2011) was an Italian neuroscientist and cyberneticist. He was former director at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Tübingen, Germany.

His ...

(mentor of Christof Koch

Christof Koch ( ; born November 13, 1956) is a German-American neurophysiologist and computational neuroscientist best known for his work on the neural basis of consciousness. He is the president and chief scientist of the Allen Institute for B ...

), Korbinian Brodmann

Korbinian Brodmann (17 November 1868 – 22 August 1918) was a German neurologist who became famous for mapping the cerebral cortex and defining 52 distinct regions, known as Brodmann areas, based on their cytoarchitectonic (histological) chara ...

, Rafael Lorente de Nó Rafael Lorente de Nó (April 8, 1902 – April 2, 1990) was a Spanish neuroscientist who advanced the scientific understanding of the nervous system with his seminal research.

He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

The National Acad ...

and Harald Brockhaus

Harald or Haraldr is the Old Norse form of the given name Harold. It may refer to:

Medieval Kings of Denmark

* Harald Bluetooth

Harald "Bluetooth" Gormsson ( non, Haraldr Blátǫnn Gormsson; da, Harald Blåtand Gormsen, died c. 985/86) was ...

. This institute gave rise to the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research

The Max Planck Institute for Brain Research is located in Frankfurt, Germany. It was founded as Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research in Berlin 1914, moved to Frankfurt-Niederrad in 1962 and more recently in a new building in Frankfurt-Rie ...

in 1945.Helga Satzinger �Femininity and Science: The Brain Researcher Cécile Vogt (1875-1962)

. Translation of: Weiblichkeit und Wissenschaft. In: Bleker, Johanna (ed.): Der Eintritt der Frauen in die Gelehrtenrepublik. Husum, 1998, 75-93. As a clinician, Vogt used

hypnotism

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI), reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.In 2015, the American Psychologica ...

(Stuckrade-Barre and Danek 2004) until 1903 and wrote papers on the topic. In particular, Vogt had an intense interest for localizing the origins of "genius" or traits in the brain.

Family

Vogt married the French neurologistCécile Vogt-Mugnier

Cécile Vogt-Mugnier (27 March 1875 – 4 May 1962) was a French neurologist from Haute-Savoie. She and her husband Oskar Vogt are known for their extensive cytoarchetectonic studies on the brain.

Professional life

Education and career

Vogt-M ...

. They met in Paris in 1897 while he was there working with Joseph Jules Dejerine

Joseph Jules Dejerine (3 August 1849 – 26 February 1917), was a French neurologist.

Biography

Joseph Jules Dejerine was born to French parents in Geneva, Switzerland, where his father was a carriage proprietor. During the Franco-Prussian War ...

and his wife, Augusta Marie Dejerine-Klumke

Augusta may refer to:

Places Australia

* Augusta, Western Australia

Brasil

* Rua Augusta (São Paulo)

Canada

* Augusta, Ontario

* North Augusta, Ontario

* Augusta Street (Hamilton, Ontario)

France

* Augusta Suessionum ("Augusta of the Sue ...

, who collaborated with him. Because of their similar scholarly interests, the Vogts collaborated for a long period, usually with Cécile as the primary author.

The Vogts had two daughters, both accomplished scientists in their own right:

* Marthe Vogt

Marthe Louise Vogt (September 8, 1903 – September 9, 2003) was a German scientist recognized as one of the leading neuroscientists of the twentieth century. She is mainly remembered for her important contributions to the understanding of t ...

(1903–2003) was a neuropharmacologist who became a Fellow of the Royal Society and a professor at Cambridge.

* Marguerite Vogt

Marguerite Vogt (13 February 1913 – 6 July 2007) was a cancer biologist and virologist. She was most noted for her research on polio and cancer at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies.

Early life

Vogt was born in Germany in 1913. The you ...

(1913–2007) started as a developmental geneticist working in Drosophila

''Drosophila'' () is a genus of flies, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or (less frequently) pomace flies, vinegar flies, or wine flies, a reference to the characteristic of many species ...

, then moved to the US in 1950. She developed methods to culture poliovirus

A poliovirus, the causative agent of polio (also known as poliomyelitis), is a serotype of the species ''Enterovirus C'', in the family of ''Picornaviridae''. There are three poliovirus serotypes: types 1, 2, and 3.

Poliovirus is composed of an ...

with Renato Dulbecco

Renato Dulbecco ( , ; February 22, 1914 – February 19, 2012) was an Italian–American virologist who won the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on oncoviruses, which are viruses that can cause cancer when they infect anima ...

. She was a faculty member at The Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is a scientific research institute located in the La Jolla community of San Diego, California, U.S. The independent, non-profit institute was founded in 1960 by Jonas Salk, the developer of the polio vacci ...

where she worked on viral transformation and cellular immortalization of cancer cells.

Politics

Vogt was a socialist, involved with the factions led by Mme Fessard who knew him personally, and with the guesdist element of the French socialist party (Jules Guesde

Jules Bazile, known as Jules Guesde (; 11 November 1845 – 28 July 1922) was a French socialist journalist and politician.

Guesde was the inspiration for a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter ...

was at the far left wing of this party). He was never a Communist, although he did interact with the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

on a number of occasions. They sent him several researchers, including N. V. Timofeev-Resovskij

Nikolaj Vladimirovich Timofeev-Resovskij (also Timofeyeff-Ressovsky; russian: Николай Владимирович Тимофеев-Ресовский; – 28 March 1981) was a Soviet biologist. He conducted research in radiation genetic ...

(whom Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repress ...

met in the Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

). He helped to establish the brain institute in Moscow.

Vogt was opposed to the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

. Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach

Gustav Georg Friedrich Maria Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach (born Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach; 7 August 1870 – 16 January 1950) was a German foreign service official who became chairman of the board of Friedrich Krupp AG, a heavy industry con ...

helped fund a small hospital in Schwarzwald near Neustadt when Vogt was dismissed in 1936 from his position with the Kaiser Wilhelm Brain Research Institute.

Institutes and journals

Vogt was the editor of the prominent ''Journal für Psychologie und Neurologie'' published in German, French and English which made many of the most important contributions between the twoWorld Wars

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

. This later became ''The Journal für Hirnforschung''.

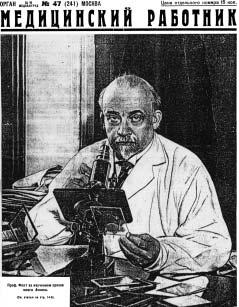

Lenin's brain

Vogt had a longstanding interest in localizing functions in the brain. In 1924, Vogt was one of the neurologists asked to consult onLenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

’s illness and was given his brain for histological study after Lenin's death. He found that Lenin's brain showed a great number of "giant cells", which Vogt saw as a sign of superior mental function. "The giant cells" were cortical pyramidal cell

Pyramidal cells, or pyramidal neurons, are a type of multipolar neuron found in areas of the brain including the cerebral cortex, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. Pyramidal neurons are the primary excitation units of the mammalian prefrontal cor ...

s of unusual size. There were also particularities in layer 3

In the seven-layer OSI model of computer networking, the network layer is layer 3. The network layer is responsible for packet forwarding including routing through intermediate routers.

Functions

The network layer provides the means of transfe ...

.

In 1925 Vogt accepted an invitation to Moscow where he was assigned the establishment of an institute for brain research under the auspices of the health ministry in Moscow. Vogt got one slice of the 30,953 slices of 20 micrometer thick of the brain, and took it home to Berlin for research purposes.Paul Gregory, ''Lenin's Brain'' (Hoover Institution Press, 2008), hfdst 3, pp. 24-35 https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/Lenins_Brain_Paul_Gregory_24.pdf Therefore, contrary to claims of two Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

neurologists, L. Van Bogaert and A. Dewulf, the Soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

did not have to carry out a military operation specifically to retrieve the brain before the Americans

Americans are the Citizenship of the United States, citizens and United States nationality law, nationals of the United States, United States of America.; ; Although direct citizens and nationals make up the majority of Americans, many Multi ...

obtained it. It was, for a time, put on display in the Lenin Mausoleum

Lenin's Mausoleum (from 1953 to 1961 Lenin's & Stalin's Mausoleum) ( rus, links=no, Мавзолей Ленина, r=Mavzoley Lenina, p=məvzɐˈlʲej ˈlʲenʲɪnə), also known as Lenin's Tomb, situated on Red Square in the centre of Moscow, is ...

. The brain is still in the Moscow's Institute.

Contributions

Cortex

An interest in the correlation betweenanatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

and psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries betwe ...

drew the Vogts to study the cortex. The Vogts imposed the distinction between iso-

ISO is the most common abbreviation for the International Organization for Standardization.

ISO or Iso may also refer to: Business and finance

* Iso (supermarket), a chain of Danish supermarkets incorporated into the SuperBest chain in 2007

* Iso ...

and allocortex

The allocortex or heterogenetic cortex, and neocortex are the two types of cerebral cortex in the brain. The allocortex is the much smaller area of cortex taking up just 10 %, the neocortex takes up the remaining 90 %. It is characterized by havi ...

. Based on their cytoarchitectonic studies, they promoted a six-layer pattern (there were 5 for Meynert and 7 for Cajal).

Thalamus

Oskar made several presentations of his view of thethalamus

The thalamus (from Greek θάλαμος, "chamber") is a large mass of gray matter located in the dorsal part of the diencephalon (a division of the forebrain). Nerve fibers project out of the thalamus to the cerebral cortex in all directions, ...

in Paris. Oskar and Cécile further referred to the work of Constantin von Monakow

Constantin von Monakow (4 November 1853 – 19 October 1930) was a Russian-Swiss neuropathologist who was a native of Bobretsovo in the Vologda Governorate.

He studied at the University of Zurich while working as an assistant at the Burghölzli I ...

in a series on the anatomy of mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

. This was not a seminal work.

The main contribution of the Vogts was ''La myelocytoarchitecture du thalamus du cercopithèque'' from Cécile alone (1909). The great contribution of Cécile has been that the partition of the lateral region ( lateral mass) should rely on the territories (the spaces occupied) of the main afferents. She distinguished from back to front the lemnical radiation and a particular nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

, in front of it the cerebellar (prelemniscal) radiation with another nucleus and more anteriorly the "lenticular" radiation. This system still describes the subdivision of the thalamus (Percheron, 1977, Percheron et al. 1996). Her paper was followed by ''Die cytoarchitechtonik des Zwishenhirns de Cercothipiteken'' from Friedmann (1911) traducing in cytoarchitectonic terms, her partition.

A paper published in common in 1941 (Thalamus studien I to III), devoted to the human thalamus, represented an important step in partitioning and naming thalamic parts. The anatomy of the thalamus from Hassler (one of their students) was published in 1959, the year of the death of Oskar. It is not known whether the master accepted the excessive partition and unnecessary complication of this work; it was an atlas dedicated to stereotacticans. The paper of 1941 was much simpler.

Basal ganglia

The Vogts greatly contributed to the analysis of what is known today as thebasal ganglia

The basal ganglia (BG), or basal nuclei, are a group of subcortical nuclei, of varied origin, in the brains of vertebrates. In humans, and some primates, there are some differences, mainly in the division of the globus pallidus into an extern ...

system. Their main interest was on the striatum

The striatum, or corpus striatum (also called the striate nucleus), is a nucleus (a cluster of neurons) in the subcortical basal ganglia of the forebrain. The striatum is a critical component of the motor and reward systems; receives glutamate ...

, that after Foix and Nicolesco they proposed (1941) to name so. This was including the caudate nucleus

The caudate nucleus is one of the structures that make up the corpus striatum, which is a component of the basal ganglia in the human brain. While the caudate nucleus has long been associated with motor processes due to its role in Parkinson's di ...

, the putamen

The putamen (; from Latin, meaning "nutshell") is a round structure located at the base of the forebrain (telencephalon). The putamen and caudate nucleus together form the dorsal striatum. It is also one of the structures that compose the basal n ...

and the fundus.

Eponym

The Vogt-Vogt syndrome is an extrapyramidal disturbance with double sidedathetosis

Athetosis is a symptom characterized by slow, involuntary, convoluted, writhing movements of the fingers, hands, toes, and feet and in some cases, arms, legs, neck and tongue. Movements typical of athetosis are sometimes called ''athetoid'' moveme ...

occurring in early childhood.Whonamedit? Oskar VogWhonameditWhonamedit? Cécile Vogt, (born Mugnier

WhonameditWhonamedit? Vogt-Vogt syndrom

Whonamedit

Gallery

Awards

* 1950 — National Award East Germany, GRDReferences

* *Schiffer, Davide, "Il Prof Vogt e i suoi celebri studi sul cervello di Lenin" (https://www.policlinicodimonza.it/prof-vogt-i-suoi-celebri-studi-sul-cervello-lenin) *Spengler, Tilman (1991), ''Lenins Hirn'', Reinbek, Rowohlt. Translated as ''Lenin's Brain'', Farrar, Straus, Giroux books, 1993 (Romanticized history). *Stukrade-Barre, S and Danek, A. (2004), "Oskar Vogt (1870–1959), hypnotist and brain researcher, husband of Cecile (1875–1962)", in: ''Nerven arzt'' 75, pp. 1038–1041 (in German) *Horst-Peter Wolff (2009), ''Cécile und Oskar Vogt. Eine illustrierte Biographie'' Fürstenberg / Havel 2009 lagenfurter Beiträge zur Technikdiskussion, Heft 128(https://ubdocs.aau.at/open/voll/tewi/AC08125853.pdf)External links

*Biography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Vogt, Oskar 1870 births 1959 deaths People from Husum German neurologists Members of the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin German expatriates in the Soviet Union Max Planck Institute directors