false Prophet.

Other notable early critics of Islam included:

*

Abu Isa al-Warraq

Abu Isa al-Warraq, full name ''Abū ʿĪsā Muḥammad ibn Hārūn al-Warrāq'' ( ar, أبو عيسى محمد بن هارون الوراق, died 861-2 AD/247 AH), was a 9th-century Arab skeptic scholar and critic of Islam and religion in genera ...

, a 9th-century scholar and critic of Islam.

*

Ibn al-Rawandi

Abu al-Hasan Ahmad ibn Yahya ibn Ishaq al-Rawandi ( ar, أبو الحسن أحمد بن يحيى بن إسحاق الراوندي), commonly known as Ibn al-Rawandi ( ar, ابن الراوندي; 827–911 CEAl-Zandaqa Wal Zanadiqa, by Moham ...

, a 9th-century atheist, who repudiated Islam and criticised religion in general.

*

al-Ma'arri, an 11th-century Arab poet and critic of Islam and all other religions. Also known for his

veganism and

antinatalism.

[Reynold Alleyne Nicholson, 1962, ''A Literary History of the Arabs'', p. 319. Routledge]

*

Abu Bakr al-Razi, a Persian

physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

,

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

and

alchemist

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscience, protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in Chinese alchemy, C ...

who lived during the

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

. He criticized the concepts of

prophethood and

revelation in Islam.

Medieval world

Medieval Islamic world

In the early centuries of the Islamic

Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

,

Islamic law allowed citizens to freely express their views, including criticism of Islam and religious authorities, without fear of persecution.

Accordingly, there have been several notable critics and skeptics of Islam that arose from within the Islamic world itself. One eminent critic, living in the tenth and eleventh-century

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

was the blind poet

Al-Ma'arri. He became well known for a poetry that was affected by a "pervasive pessimism". He labeled religions in general as "noxious weeds" and said that Islam does not have a monopoly on truth. He had particular contempt for the ''

ulema

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

'', writing that:

In 1280, the

Jewish philosopher

Jewish philosophy () includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. Until modern ''Haskalah'' (Jewish Enlightenment) and Jewish emancipation, Jewish philosophy was preoccupied with attempts to reconcile ...

,

Ibn Kammuna, criticized Islam in his book ''Examination of the Three Faiths''. He reasoned that the

Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

was incompatible with the principles of justice, and that this undercut the notion of Muhammad being the perfect man: "there is no proof that Muhammad attained perfection and the ability to perfect others as claimed." The philosopher thus claimed that people converted to Islam from ulterior motives:

According to

Bernard Lewis, just as it is natural for a Muslim to assume that the converts to his religion are attracted by its truth, it is equally natural for the convert's former coreligionists to look for baser motives and

Ibn Kammuna's list seems to cover most of such nonreligious motives.

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

, one of the foremost 12th-century

rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

nical

arbiters and philosophers, sees the relation of Islam to Judaism as primarily theoretical. Maimonides has no quarrel with the strict monotheism of Islam, but finds fault with the practical politics of Muslim regimes. He also considered

Islamic ethics

Islamic ethics (أخلاق إسلامية) is the "philosophical reflection upon moral conduct" with a view to defining "good character" and attaining the "pleasure of God" (''raza-e Ilahi''). It is distinguished from "Islamic morality", which per ...

and politics to be inferior to their Jewish counterparts. Maimonides criticised what he perceived as the lack of virtue in the way Muslims rule their societies and relate to one another.

[The Mind of Maimonides](_blank)

by David Novak. Retrieved 29 April 2006. In his Epistle to Yemenite Jewry, he refers to Mohammad, as "''hameshuga''" – "that madman".

Apologetic writings, attributed to

Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa

Abū Muhammad ʿAbd Allāh Rūzbih ibn Dādūya ( ar, ابو محمد عبدالله روزبه ابن دادويه), born Rōzbih pūr-i Dādōē ( fa, روزبه پور دادویه), more commonly known as Ibn al-Muqaffaʿ ( ar, ابن الم� ...

, not only defended

Manichaeism

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian Empire, Parthian ...

against Islam, but also criticized the Islamic concept of God. Accordingly, the Quranic deity was disregarded as an unjust, tyrannic, irrational and malevolent ''

demon

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in media such as comics, video games, movies, ani ...

ic entity'', who "fights with humans and boasts about His victories" and "sitting on a throne, from which He descends". Such anthropomorphic descriptions of God were at odds with the Manichaean understanding of

Divinity

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.[divine](_blank) . Further, according to Manichaeism, it would be impossible that good and evil originate from the same source, therefore the Islamic deity could not be the true god.

Medieval Christianity

Early criticism came from Christian authors, many of whom viewed Islam as a Christian

heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

or a form of idolatry and often explained it in apocalyptic terms. Islamic salvation optimism and its carnality was criticized by Christian writers. Islam's sensual descriptions of paradise led many Christians to conclude that Islam was not a spiritual religion, but a material one. Although sensual pleasure was also present in early Christianity, as seen in the writings of

Irenaeus

Irenaeus (; grc-gre, Εἰρηναῖος ''Eirēnaios''; c. 130 – c. 202 AD) was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in the southern regions of present-day France and, more widely, for the dev ...

, the doctrines of the former

Manichaean

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian Empire, Parthian ...

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

led to broad repudiation of bodily pleasure in both life and the afterlife.

Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari

Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari ( fa, علی ابن سهل ربن طبری ) (c. 838 – c. 870 CE; also given as 810–855 or 808–864 also 783–858), was a Persian Muslim scholar, physician and psychologist, who produced one of t ...

defended the Quranic description of paradise by asserting that the Bible also implies such ideas, such as drinking wine in

Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew), or simply Matthew. It is most commonly abbreviated as "Matt." is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel's Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people and for ...

. During the

Fifth Crusade,

Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 J ...

declared that many men had been seduced by Muhammad for the pleasure of flesh.

Defamatory images of

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

, derived from early 7th century depictions of

Byzantine Church,

[Minou Reeves, P. J. Stewart ''Muhammad in Europe: A Thousand Years of Western Myth-Making'' NYU Press, 2003 p. 93–96] appear in the 14th-century

epic poem Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and ...

by

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

.

[G. Stone ''Dante's Pluralism and the Islamic Philosophy of Religion'' Springer, 12 May 2006 p. 132] Here, Muhammad appears in the eighth circle of hell, along with Ali. Dante does not blame Islam as a whole, but accuses Muhammad of

schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

, by establishing another religion after Christianity.

Some medieval ecclesiastical writers portrayed Muhammad as possessed by

Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as Devil in Christianity, the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an non-physical entity, entity in the Abrahamic religions ...

, a "precursor of the

Antichrist" or the Antichrist himself.

[Mohammed and Mohammedanism](_blank)

by Gabriel Oussani, ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 16 April 2006. The ''

Tultusceptru de libro domni Metobii

''Tultusceptru de libro domni Metobii'' is a short Latin biography of Muḥammad written in the 9th or 10th century in the Iberian Peninsula. It is a polemical text designed to show that Islam is a false religion and Muḥammad the unwitting dup ...

'', an Andalusian

manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printing, printed or repr ...

with unknown dating, shows how Muhammad (called Ozim, from

Hashim

Hashim ( ar, هاشم) is a common male Arabic given name.

Hashim may also refer to:

*Hashim Amir Ali

*Hashim (poet)

*Hashim Amla

*Hashim Thaçi

*Hashim Khan

* Hashim Qureshi

* Mir Hashim Ali Khan

*Hashim al-Atassi

*Hashim ibn Abd Manaf

*Hashim ib ...

) was tricked by

Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as Devil in Christianity, the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an non-physical entity, entity in the Abrahamic religions ...

into adulterating an originally pure divine revelation. The story argues God was concerned about the spiritual fate of the Arabs and wanted to correct their deviation from the faith. He then sends an angel to the monk Osius who orders him to preach to the Arabs. Osius however is in ill-health and orders a young monk, Ozim, to carry out the angel's orders instead. Ozim sets out to follow his orders, but gets stopped by an evil angel on the way. The ignorant Ozim believes him to be the same angel that spoke to Osius before. The evil angel modifies and corrupts the original message given to Ozim by Osius, and renames Ozim Muhammad. From this followed the erroneous teachings of Islam, according to the ''Tultusceptru''. According to the monk

Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom o ...

Muhammad was foretold in

Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

16:12, which describes

Ishmael

Ishmael ''Ismaḗl''; Classical/Qur'anic Arabic: إِسْمَٰعِيْل; Modern Standard Arabic: إِسْمَاعِيْل ''ʾIsmāʿīl''; la, Ismael was the first son of Abraham, the common patriarch of the Abrahamic religions; and is cons ...

as "a wild man" whose "hand will be against every man". Bede says about Muhammad: "Now how great is his hand against all and all hands against him; as they impose his authority upon the whole length of Africa and hold both the greater part of Asia and some of Europe, hating and opposing all."

In 1391 a dialogue was believed to have occurred between Byzantine Emperor

Manuel II Palaiologos

Manuel II Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( gr, Μανουὴλ Παλαιολόγος, Manouēl Palaiológos; 27 June 1350 – 21 July 1425) was Byzantine emperor from 1391 to 1425. Shortly before his death he was tonsured a monk and received the na ...

and a Persian scholar in which the Emperor stated:

Otherwise the

Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek language, Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the Eastern Orthodox Church, entire body of Orthodox (Chalced ...

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

Paul of Antioch accepts Muhammed as a prophet, but not that his mission was universal. Since the law of Christ is superior to the law of Islam, Muhammad was only ordered to the Arabs, whom a prophet was not sent yet.

Denis the Carthusian

Denis the Carthusian (1402–1471), also known as Denys van Leeuwen, Denis Ryckel, Dionysius van Rijkel, Denys le Chartreux (or other combinations of these terms), was a Roman Catholic theologian and mystic.

Life

Denis was born in 1402 in that ...

wrote two treatises to refute Islam at the request of

Nicholas of Cusa

Nicholas of Cusa (1401 – 11 August 1464), also referred to as Nicholas of Kues and Nicolaus Cusanus (), was a German Catholic cardinal, philosopher, theologian, jurist, mathematician, and astronomer. One of the first German proponents of Renai ...

, ''Contra perfidiam Mahometi, et contra multa dicta Sarracenorum libri quattuor'' and ''Dialogus disputationis inter Christianum et Sarracenum de lege Christi et contra perfidiam Mahometi''.

Enlightenment Europe

David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment philo ...

was critical of traditional religion and scholars generally agree that Hume was both a

naturalist and a

sceptic, though he considered

monotheistic

Monotheism is the belief that there is only one deity, an all-supreme being that is universally referred to as God. Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford ...

religions to be more "comfortable to sound reason" than

polytheism

Polytheism is the belief in multiple deities, which are usually assembled into a pantheon of gods and goddesses, along with their own religious sects and rituals. Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, the ...

and found Islam to be more "ruthless" than Christianity. In ''

Of the Standard of Taste'', an essay by Hume, the Quran is described as an "absurd performance" of a "pretended prophet" who lacked "a just sentiment of morals". Attending to the narration, Hume says, "we shall soon find, that

uhammadbestows praise on such instances of treachery, inhumanity, cruelty, revenge, bigotry, as are utterly incompatible with civilized society. No steady rule of right seems there to be attended to; and every action is blamed or praised, so far as it is beneficial or hurtful to the true believers."

The commonly held view in Europe during the Enlightenment was that Islam, then synonymous with the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, was a bloody, ruthless and intolerant religion. In the European view, Islam lacked divine authority and regarded the sword as the route to heaven. Hume appears to represent this view in his reference to the "bloody principles" of Islam, though he also makes similar critical comments about the "bloody designs" characterizing the conflict between

Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and

Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

during the

Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

. Many contemporary works about Islam were available to influence Hume's opinions by authors such as

Isaac Barrow

Isaac Barrow (October 1630 – 4 May 1677) was an English Christian theologian and mathematician who is generally given credit for his early role in the development of infinitesimal calculus; in particular, for proof of the fundamental theorem ...

,

Humphrey Prideaux

Humphrey Prideaux (3 May 1648 – 1 November 1724) was a Cornish churchman and orientalist, Dean of Norwich from 1702. His sympathies inclined to Low Churchism in religion and to Whiggism in politics.

Life

The third son of Edmond Prideaux, he was ...

,

John Jackson John or Johnny Jackson may refer to:

Entertainment Art

* John Baptist Jackson (1701–1780), British artist

* John Jackson (painter) (1778–1831), British painter

* John Jackson (engraver) (1801–1848), English wood engraver

* John Richardson ...

,

Charles Wolseley,

Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius (; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de Groot () and Hugo de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, poet and playwright.

A teenage intellectual prodigy, he was born in Delft ...

,

Paul Rycaut,

Thomas Hyde,

Pierre Bayle, and

Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal ( , , ; ; 19 June 1623 – 19 August 1662) was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, philosopher, and Catholic Church, Catholic writer.

He was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen. Pa ...

. The writers of this period were also influenced by

George Sale

George Sale (1697–1736) was a British Orientalist scholar and practising solicitor, best known for his 1734 translation of the Quran into English. In 1748, after having read Sale's translation, Voltaire wrote his own essay "De l'Alcoran ...

who, in 1743, had translated the Quran into

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

.

Modern era

Western authors

In the early 20th century, the prevailing view among Europeans was that Islam was the root cause of Arab and

Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

"backwardness". They saw Islam as an obstacle to assimilation, a view that was expressed by a writer in colonial

French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

named

André Servier

André Servier was an historian who lived in French Algeria at the beginning of the 20th century.

Career

He was chief editor of La Dépêche de Constantine, a newspaper from the city of Constantine in northeastern Algeria.

Servier studied well th ...

. In his book, titled ''Islam and the Psychology of the Musulman'', Servier wrote that, "The only thing Arabs ever invented was their religion. And this religion is, precisely, the main obstacle between them and us." Servier describes Islam as a "religious nationalism in which every Muslim brain is steeped". According to Servier, the only reason this nationalism has not "been able to pose a threat to humanity" was that the "rigid dogma" of Islam had rendered the Arabs "incapable of fighting against the material forces placed at the disposal of Western civilization by science and progress".

The

Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

orientalist scholar Sir

William Muir

Sir William Muir (27 April 1819 – 11 July 1905) was a Scottish Orientalist, and colonial administrator, Principal of the University of Edinburgh and Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Provinces of British India.

Life

He was born at Gl ...

criticised Islam for what he perceived to be an inflexible nature, which he held responsible for stifling progress and impeding social advancement in Muslim countries. The following sentences are taken from the

Rede Lecture he delivered at

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

in 1881:

The

church historian Philip Schaff described Islam as spread by violence and fanaticism, and producing a variety of social ills in the regions it conquered.

[Schaff, P., & Schaff, D. S. (1910). ''History of the Christian church''. Third edition. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Volume 4, Chapter III, section 40 "Position of Mohammedanism in Church History"]

Schaff also described Islam as a derivative religion based on an amalgamation of "heathenism, Judaism and Christianity".

[Schaff, P., & Schaff, D. S. (1910). ''History of the Christian church''. Third edition. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Volume 4, Chapter III, section 45 "The Mohammedanism Religion"]

J. M. Neale criticized Islam in terms similar to those of Schaff, arguing that it was made up of a mixture of beliefs that provided something for everyone.

[ Neale, J. M. (1847). A History of the Holy Eastern Church: The Patriarchate of Alexandria. London: Joseph Masters. Volume II, Section I "Rise of Mahometanism" (p. 68)]

James Fitzjames Stephen

Sir James Fitzjames Stephen, 1st Baronet, KCSI (3 March 1829 – 11 March 1894) was an English lawyer, judge, writer, and philosopher. One of the most famous critics of John Stuart Mill, Stephen achieved prominence as a philosopher, law re ...

, describing what he understood to be the Islamic conception of the ideal society, wrote the following:

G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, ''Time'' observed: "Wh ...

criticized Islam as a derivative from Christianity. He described it as a heresy or parody of Christianity. In ''

The Everlasting Man

''The Everlasting Man'' is a Christian apologetics book written by G. K. Chesterton, published in 1925. It is, to some extent, a deliberate rebuttal of H. G. Wells' ''The Outline of History'', disputing Wells' portrayals of human life and civi ...

'' he says:

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

criticized what he alleged to be the effects Islam had on its believers, which he described as fanatical frenzy combined with fatalistic apathy, enslavement of women, and militant proselytizing.

[Winston S. Churchill, from The River War, first edition, Vol. II, pp. 248–50 (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1899)] In his 1899 book ''

The River War'' he says:

According to historian

Warren Dockter, Churchill wrote this during a time of a fundamentalist revolt in Sudan and this statement does not reflect his full view of Islam, which were "often paradoxical and complex". He could be critical but at times "romanticized" the Islamic world; he exhibited great "respect, understanding and magnanimity".

Churchill had a fascination of Islam and Islamic civilization.

Winston Churchill's future sister-in-law expressed concerns about his fascination by stating, "

ease don't become converted to Islam; I have noticed in your disposition a tendency to orientalism." According to historian Warren Dockter, however, he "never seriously considered converting".

He primarily admired its martial aspects, the "Ottoman Empire's history of territorial expansion and military acumen", to the extent that in 1897 he wished to fight for the Ottoman Empire. According to Dockter, this was largely for his "lust for glory".

[ Based on Churchill's letters, he seemed to regard Islam and Christianity as equals.]Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereign ...

quoted an unfavorable remark about Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

made at the end of the 14th century by Manuel II Palaiologos

Manuel II Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( gr, Μανουὴλ Παλαιολόγος, Manouēl Palaiológos; 27 June 1350 – 21 July 1425) was Byzantine emperor from 1391 to 1425. Shortly before his death he was tonsured a monk and received the na ...

, the Byzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

: As the English translation of the Pope's lecture was disseminated across the world, many Muslim politicians and religious leaders protested against what they saw as an insulting mischaracterization of Islam.Majlis-e-Shoora

The Parliament of Pakistan ( ur, , , "Pakistan Advisory Council" or "Pakistan Consultative Assembly") is the federal and supreme legislative body of Pakistan. It is a bicameral federal legislature that consists of the Senate as the upper ho ...

'' (Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

i parliament) unanimously called on the Pope to retract "this objectionable statement".

South Asian authors

The

The Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism.Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

philosopher Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda (; ; 12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born Narendranath Datta (), was an Indian Hindu monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic Ramakrishna. He was a key figure in the introd ...

commented on Islam:

Dayanand Saraswati calls the concept of Islam to be highly offensive, and doubted that there is any connection of Islam with God:

Pandit Lekh Ram regarded that Islam was grown through the violence and desire for wealth. He further asserted that Muslims deny the entire Islamic prescribed violence and atrocities, and will continue doing so. He wrote:

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, the moral leader of the 20th-century Indian independence movement, found the history of Muslims to be aggressive, while he claimed that Hindus have passed that stage of societal evolution:

Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

, the first Prime Minister of India

The prime minister of India (IAST: ) is the head of government of the Republic of India. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and their chosen Council of Ministers, despite the president of India being the nominal head of the ...

, in his book ''Discovery of India'', describes Islam to have been a faith for military conquests. He wrote "Islam had become a more rigid faith suited more to military conquests rather than the conquests of the mind", and that Muslims brought nothing new to his country.

Other authors

Iranian writer

Iranian writer Sadegh Hedayat

Sadegh Hedayat ( fa, صادق هدایت ; 17 February 1903 – 9 April 1951) was an Iranian writer and translator. Best known for his novel '' The Blind Owl'', he was one of the earliest Iranian writers to adopt literary modernism in their care ...

regarded Islam as the corrupter of Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, he said:

Nobel prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

-winning novelist V. S. Naipaul stated that Islam requires its adherents to destroy everything which is not related to it. He described it as having a:

Nobel prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

-winning playwright Wole Soyinka

Akinwande Oluwole Babatunde Soyinka (Yoruba: ''Akínwándé Olúwọlé Babátúndé Ṣóyíinká''; born 13 July 1934), known as Wole Soyinka (), is a Nigerian playwright, novelist, poet, and essayist in the English language. He was awarded t ...

stated that Islam had a role in denigrating African spiritual traditions. He criticized attempts to whitewash what he sees as the destructive and coercive history of Islam on the continent:

Soyinka also regarded Islam as "superstition", and said that it does not belong to Africa. He stated that it is mainly spread with violence and force.

Tatar

The Tatars ()[Tatar]

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different Tengrist

Tengrism (also known as Tengriism, Tengerism, or Tengrianism) is an ethnic and old state Turko- Mongolic religion originating in the Eurasian steppes, based on folk shamanism, animism and generally centered around the titular sky god Tengri. ...

s criticize Islam as a semitic religion, which forced Turks to submission to an alien culture. Submission and humility, two significant components of Islamic spirituality, are disregarded as major failings of Islam, not as virtues. Further, since Islam mentions semitic history as if it were the history of all mankind, but disregards components of other cultures and spirituality, the international approach of Islam is seen as a threat. It additionally gives Imams an opportunity to march against their own people under the banner of international Islam.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

, founder of the Turkish Republic

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

, described Islam as the religion of the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

in his own work titled ''Vatandaş için Medeni Bilgiler'' by his own critical and nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

views:

Sami Aldeeb

Sami Awad Aldeeb Abu-Sahlieh (in Arabic language, Arabic: سامي عوض الذيب أبو ساحلية / ''Sāmy ʿwḍ ʾĀd-dyb ʾĀbw-Sāḥlyh'') (born 5 September 1949 in Zababdeh, near Jenin in the West Bank) is a Swiss Palestinian lawy ...

, Palestinian-born Swiss lawyer and author of many books and articles on Arab and Islamic law, expressed various positions critical of Islam, for example, he positioned himself for a ban on the erection of minarets in Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, since in his opinion the constitution allows prayer, but not shouting.

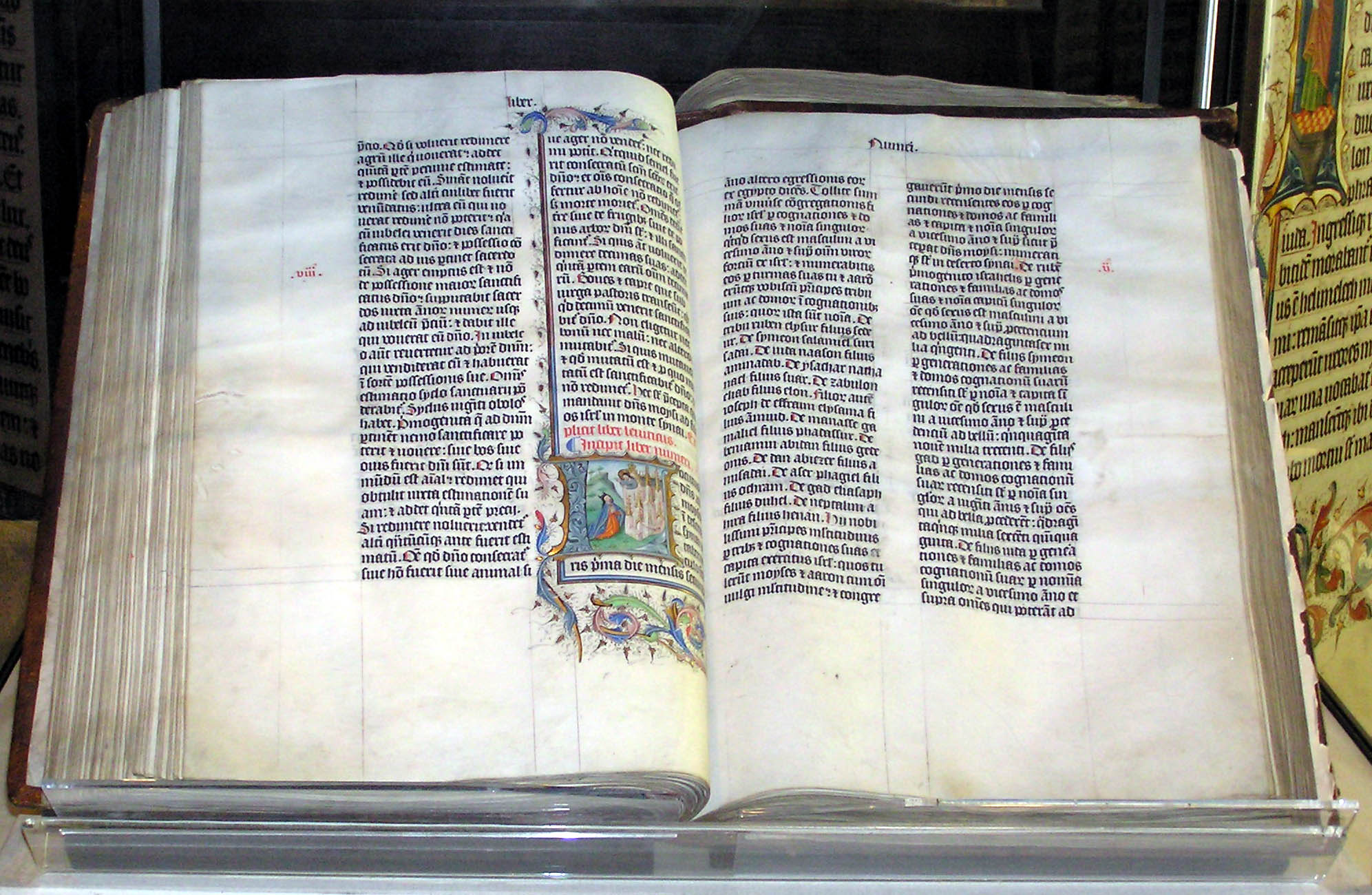

Scripture

Criticism of the Quran

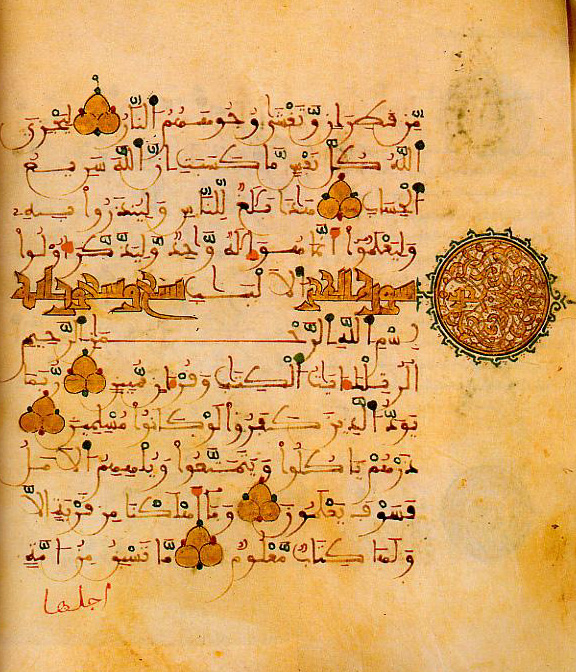

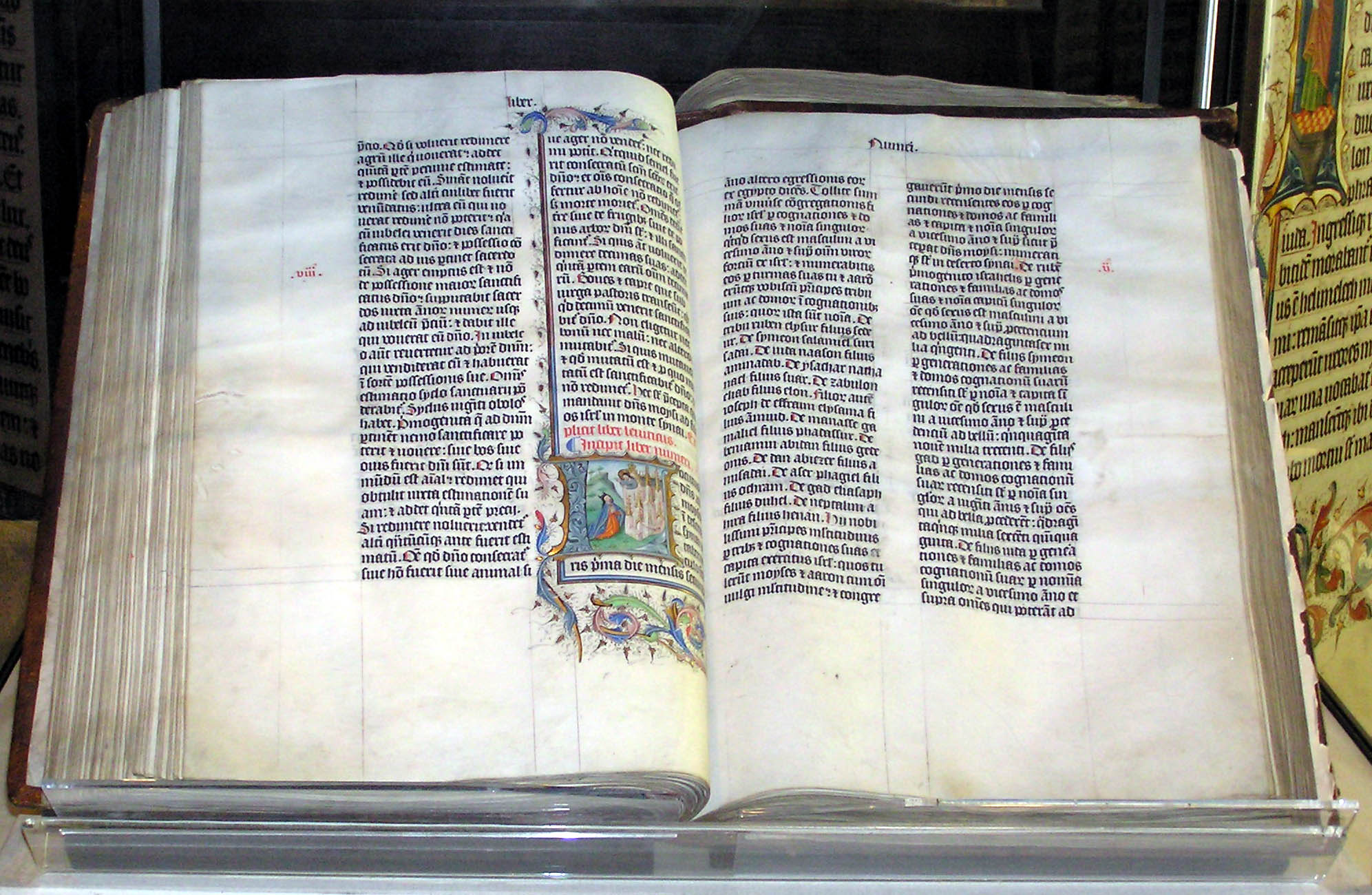

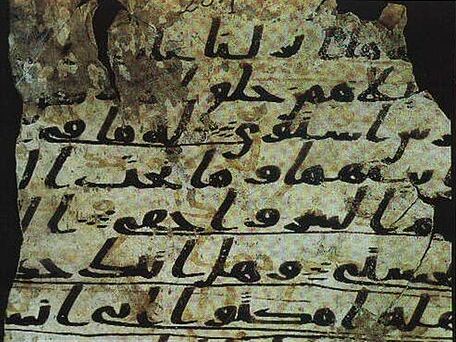

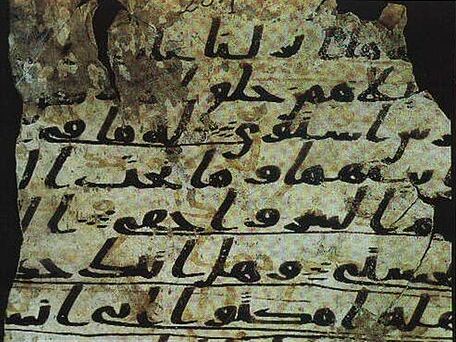

Originality of Quranic manuscripts. According to traditional Islamic scholarship, all of the Quran was written down by Muhammad's companions while he was alive (during 610–632 CE), but it was primarily an orally related document. The written compilation of the whole Quran in its definite form as we have it now was not completed until many years after the death of Muhammad. John Wansbrough, Patricia Crone and

Originality of Quranic manuscripts. According to traditional Islamic scholarship, all of the Quran was written down by Muhammad's companions while he was alive (during 610–632 CE), but it was primarily an orally related document. The written compilation of the whole Quran in its definite form as we have it now was not completed until many years after the death of Muhammad. John Wansbrough, Patricia Crone and Yehuda D. Nevo

Yehuda D. Nevo (1932 – 12 February 1992) was a Middle Eastern archeologist living in Israel. He died after a long battle with cancer in 1992.

Research

Nevo discovered Kufic inscriptions in the Negev desert in Israel, four hundred of which ...

argue that all the primary sources which exist are from 150 to 300 years after the events which they describe, and thus are chronologically far removed from those events.

Imperfections in the Quran. Critics reject the idea that the Quran is miraculously perfect and impossible to imitate as asserted in the Quran itself. The 1901–1906 ''Jewish Encyclopedia

''The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day'' is an English-language encyclopedia containing over 15,000 articles on th ...

'', for example, writes: "The language of the Koran is held by the Mohammedans to be a peerless model of perfection. Critics, however, argue that peculiarities can be found in the text. For example, critics note that a sentence in which something is said concerning Allah is sometimes followed immediately by another in which Allah is the speaker (examples of this are suras xvi. 81, xxvii. 61, xxxi. 9, and xliii. 10). Many peculiarities in the positions of words are due to the necessities of rhyme ( lxix. 31, lxxiv. 3), while the use of many rare words and new forms may be traced to the same cause (comp. especially xix. 8, 9, 11, 16)."["Koran"](_blank)

From the ''Jewish Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

Judaism and the Quran. According to the ''Jewish Encyclopedia'', "The dependence of Mohammed upon his Jewish teachers or upon what he heard of the Jewish Haggadah and Jewish practices is now generally conceded."redaction

Redaction is a form of editing in which multiple sources of texts are combined and altered slightly to make a single document. Often this is a method of collecting a series of writings on a similar theme and creating a definitive and coherent wo ...

in part of other sacred scriptures, in particular the Judaeo-Christian scriptures.[Wansbrough, John (1978). ''The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History''.] Herbert Berg writes that "Despite John Wansbrough's very cautious and careful inclusion of qualifications such as "conjectural," and "tentative and emphatically provisional", his work is condemned by some. Some of this negative reaction is undoubtedly due to its radicalness... Wansbrough's work has been embraced wholeheartedly by few and has been employed in a piecemeal fashion by many. Many praise his insights and methods, if not all of his conclusions." Early jurists and theologians of Islam mentioned some Jewish influence but they also say where it is seen and recognized as such, it is perceived as a debasement or a dilution of the authentic message. Bernard Lewis describes this as "something like what in Christian history was called a Judaizing heresy." According to Moshe Sharon, the story of Muhammad having Jewish teachers is a legend developed in the 10th century CE. Philip Schaff described the Quran as having "many passages of poetic beauty, religious fervor, and wise counsel, but mixed with absurdities, bombast, unmeaning images, low sensuality."[Schaff, P., & Schaff, D. S. (1910). History of the Christian church. Third edition. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Volume 4, Chapter III, section 44 "The Koran, And The Bible"]

Mohammed and God as speakers. According to Ibn Warraq, the Iranian rationalist Ali Dashti

Ali Dashti ( fa, علی دشتی, pronounced ; 31 March 1897 – January 16, 1982) was an Iranian rationalist of the twentieth century. Dashti was also an Iranian senator.

Life

Born into a Persian family in Dashti in Bushehr Province, Ira ...

criticized the Quran on the basis that for some passages, "the speaker cannot have been God."Al-Fatiha

Al-Fatiha (alternatively transliterated Al-Fātiḥa or Al-Fātiḥah; ar, ألْفَاتِحَة, ; ), is the first ''surah'' (chapter) of the Quran. It consists of 7 '' ayah'' (verses) which are a prayer for guidance and mercy. Al-Fatiha i ...

as an example of a passage which is "clearly addressed to God, in the form of a prayer."Ibn Masud

Abdullah ibn Masūd, or Abdullah ibn Masood, or Abdullah Ben Messaoud ( ar, عبد الله بن مسعود, ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʽūd; c.594-c.653), was a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad who he is regarded the greatest mufassir of Qu ...

, rejected Surah Fatihah as being part of the Quran; these kind of disagreements are, in fact, common among the companions of Muhammad who could not decide which surahs were part of the Quran and which not.Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

when he was tricked by Satan (in an incident known as the "Story of the Cranes", later referred to as the "Satanic Verses

The Satanic Verses are words of "satanic suggestion" which the Islamic prophet Muhammad is alleged to have mistaken for divine revelation. The verses praise the three pagan Meccan goddesses: al-Lāt, al-'Uzzá, and Manāt and can be read in ear ...

"). These verses were then retracted at angel Gabriel's behest.Apology of al-Kindy

''Apology of al-Kindi'' (also spelled al-Kindy) is a medieval theological polemic making a case for Christianity and drawing attention to alleged flaws in Islam. The word "apology" is a translation of the Arabic word ', and it is used in the se ...

'' Abd al-Masih ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (not to be confused with the famed philosopher al-Kindi) claimed that the narratives in the Quran were "all jumbled together and intermingled" and that this was "an evidence that many different hands have been at work therein, and caused discrepancies, adding or cutting out whatever they liked or disliked".

* The companions of Muhammad could not agree on which surahs were part of the Quran and which not. Two of the most famous companions being Ibn Masud

Abdullah ibn Masūd, or Abdullah ibn Masood, or Abdullah Ben Messaoud ( ar, عبد الله بن مسعود, ʿAbd Allāh ibn Masʽūd; c.594-c.653), was a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad who he is regarded the greatest mufassir of Qu ...

and Ubay ibn Ka'b

Ubayy ibn Ka'b ( ar, أُبَيّ ٱبْن كَعْب, ') (died 649), also known as Abu Mundhir, was a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a person of high esteem in the early Muslim community.

Biography

Ubayy was born in Medina (th ...

.

Pre-existing sources

Critics point to various pre-existing sources to argue against the traditional narrative of revelation from God. Some scholars have calculated that one third of the Quran has pre-Islamic Christian origins. Aside from the Bible, the Quran relies on several

Critics point to various pre-existing sources to argue against the traditional narrative of revelation from God. Some scholars have calculated that one third of the Quran has pre-Islamic Christian origins. Aside from the Bible, the Quran relies on several Apocrypha

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

l and legendary sources, like the Protoevangelium of James,[Leirvik 2010, pp. 33–34.] Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew,

Criticism of the Hadith

Hadith are Muslim traditions relating to the ''Sunnah'' (words and deeds) of Muhammad. They are drawn from the writings of scholars writing between 844 and 874 CE, more than 200 years after the death of Mohammed in 632 CE. Within Islam, different schools and sects have different opinions on the proper selection and use of Hadith. The four schools of Sunni Islam all consider Hadith second only to the Quran, although they differ on how much freedom of interpretation should be allowed to legal scholars. Shi'i scholars disagree with Sunni scholars as to which Hadith should be considered reliable. The Shi'as accept the Sunnah of Ali and the Imams as authoritative in addition to the Sunnah of Muhammad, and as a consequence they maintain their own, different, collections of Hadith.

It has been suggested that there exists around the Hadith three major sources of corruption: political conflicts, sectarian prejudice, and the desire to translate the underlying meaning, rather than the original words verbatim.[Brown, Daniel W. "Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought", 1999. pp. 113, 134]

Muslim critics of the hadith, Quranism, Quranists, reject the authority of hadith on theological grounds, pointing to verses in the Quran itself: "''Nothing have We omitted from the Book''", declaring that all necessary instruction can be found within the Quran, without reference to the Hadith. They claim that following the Hadith has led to people straying from the original purpose of God's revelation to Muhammad, adherence to the Quran alone. Ghulam Ahmed Pervez (1903–1985) was a noted critic of the Hadith and believed that the Quran alone was all that was necessary to discern God's will and our obligations. A fatwa, ruling, signed by more than a thousand orthodox clerics, denounced him as a 'kafir', a non-believer. His seminal work, ''Maqam-e Hadith'' argued that the Hadith were composed of "the garbled words of previous centuries", but suggests that he is not against the ''idea'' of collected sayings of the Prophet, only that he would consider any hadith that goes against the teachings of Quran to have been falsely attributed to the Prophet. The 1986 Malaysian book "Hadith: A Re-evaluation" by Kassim Ahmad was met with controversy and some scholars declared him an apostate from Islam for suggesting that "the hadith are sectarian, anti-science, anti-reason and anti-women."[Latif, Abu Ruqayyah Farasat]

The Quraniyun of the Twentieth Century

Masters Assertion, September 2006[Ahmad, Kassim. "Hadith: A Re-evaluation", 1986. English translation 1997]

John Esposito notes that "Modern Western scholarship has seriously questioned the historicity and authenticity of the ''hadith''", maintaining that "the bulk of traditions attributed to the Prophet Muhammad were actually written much later." He mentions Joseph Schacht, considered the father of the revisionist movement, as one scholar who argues this, claiming that Schacht "found no evidence of legal traditions before 722," from which Schacht concluded that "the Sunna of the Prophet is not the words and deeds of the Prophet, but apocryphal material" dating from later. Other scholars, however, such as Wilferd Madelung, have argued that "wholesale rejection as late fiction is unjustified".

Orthodox Muslims do not deny the existence of false hadith, but believe that through the scholars' work, these false hadith have been largely eliminated.

Lack of secondary evidence

The traditional view of Islam has also been criticised for the lack of supporting evidence consistent with that view, such as the lack of archaeological evidence, and discrepancies with non-Muslim literary sources. In the 1970s, what has been described as a "wave of sceptical scholars" challenged a great deal of the received wisdom in Islamic studies.

The traditional view of Islam has also been criticised for the lack of supporting evidence consistent with that view, such as the lack of archaeological evidence, and discrepancies with non-Muslim literary sources. In the 1970s, what has been described as a "wave of sceptical scholars" challenged a great deal of the received wisdom in Islamic studies.[Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998] They argued that the Islamic historical tradition had been greatly corrupted in transmission. They tried to correct or reconstruct the early history of Islam from other, presumably more reliable, sources such as coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic sources. The oldest of this group was John Wansbrough (1928–2002). Wansbrough's works were widely noted, but perhaps not widely read.

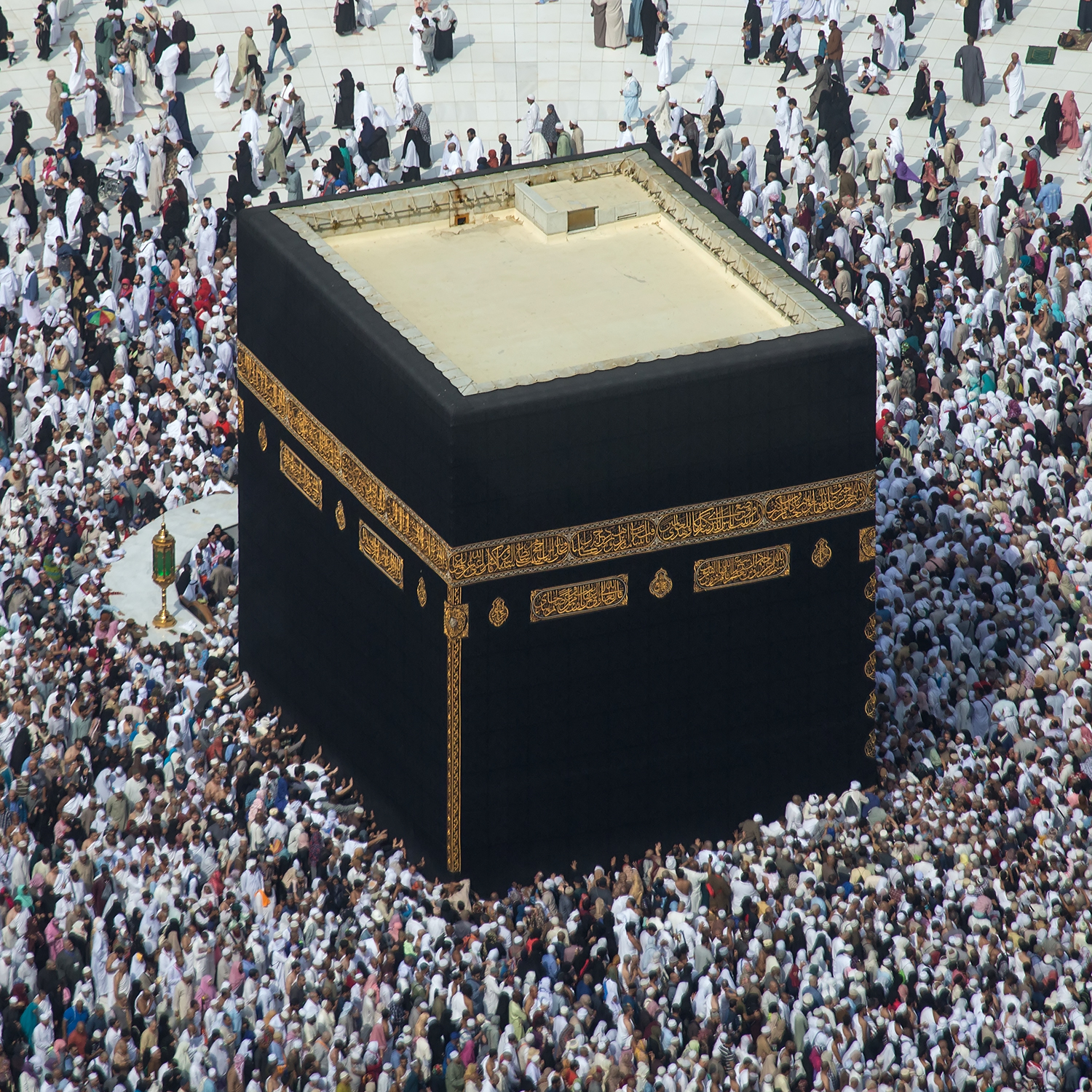

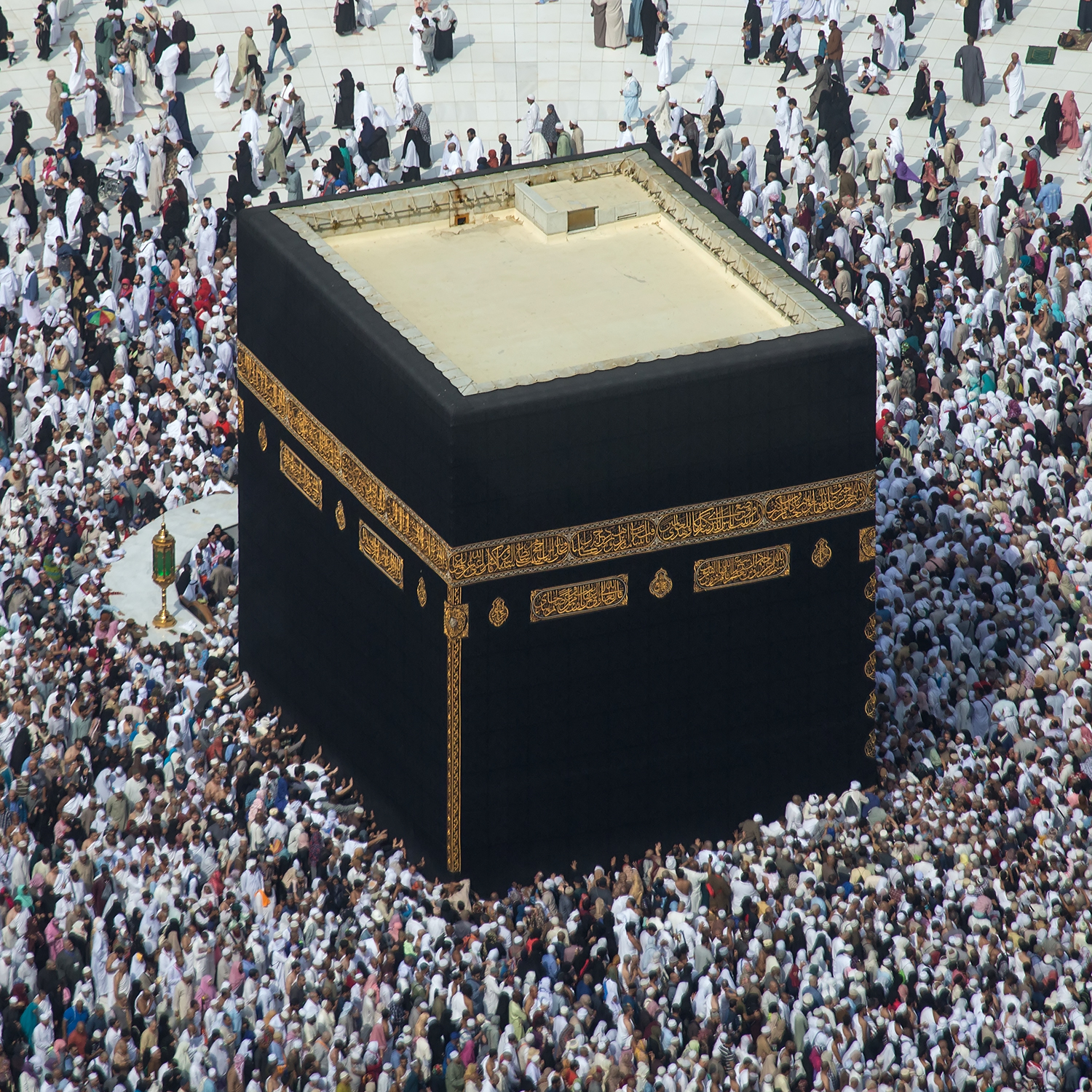

Kaaba

The Kaaba is the most sacred site in Islam. Criticism has centered on the origins of the Kaaba. In her book, ''Islam: A Short History'', Karen Armstrong asserts that the ''Kaaba'' was officially dedicated to Hubal, a Nabatean deity, and contained 360 idols that probably represented the days of the year. Imoti contends that there were numerous such ''Kaaba'' sanctuaries in Arabia at one time, but this was the only one built of stone. The others also allegedly had counterparts of the Black Stone. There was a "red stone", the deity of the south Arabian city of Ghaiman, and the "white stone" in the ''Kaaba'' of al-Abalat (near the city of Tabalah, Saudi Arabia, Tabala, south of Mecca). Grunebaum in ''Classical Islam'' points out that the experience of divinity of that period was often associated with stone Fetishism, fetishes, mountains, special rock formations, or "trees of strange growth".

According to Sarwar, about 400 years before the birth of Muhammad, a man named "Amr bin Lahyo bin Harath bin Amr ul-Qais bin Thalaba bin Azd bin Khalan bin Babalyun bin Saba", who was descended from Qahtan and was the king of Hijaz had placed a Hubal idol onto the roof of the Kaaba. This idol was one of the chief deities of the ruling tribe Quraysh. The idol was made of red agate and shaped like a human, but with the right hand broken off and replaced with a golden hand. When the idol was moved inside the Kaaba, it had seven arrows in front of it, which were used for divination. According to the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', "before the rise of Islam it was revered as a sacred sanctuary and was a site of pilgrimage." Many Muslim and academic historians stress the power and importance of the pre-Islamic Mecca. They depict it as a city grown rich on the proceeds of the spice trade. Patricia Crone believes that this is an exaggeration and that Mecca may only have been an outpost trading with nomads for leather, cloth, and camel butter. Crone argues that if Mecca had been a well-known center of trade, it would have been mentioned by later authors such as Procopius, Nonnosus, or the Syrian church chroniclers writing in Syriac. The town is absent, however, from any geographies or histories written in the three centuries before the rise of Islam.

The Kaaba is the most sacred site in Islam. Criticism has centered on the origins of the Kaaba. In her book, ''Islam: A Short History'', Karen Armstrong asserts that the ''Kaaba'' was officially dedicated to Hubal, a Nabatean deity, and contained 360 idols that probably represented the days of the year. Imoti contends that there were numerous such ''Kaaba'' sanctuaries in Arabia at one time, but this was the only one built of stone. The others also allegedly had counterparts of the Black Stone. There was a "red stone", the deity of the south Arabian city of Ghaiman, and the "white stone" in the ''Kaaba'' of al-Abalat (near the city of Tabalah, Saudi Arabia, Tabala, south of Mecca). Grunebaum in ''Classical Islam'' points out that the experience of divinity of that period was often associated with stone Fetishism, fetishes, mountains, special rock formations, or "trees of strange growth".

According to Sarwar, about 400 years before the birth of Muhammad, a man named "Amr bin Lahyo bin Harath bin Amr ul-Qais bin Thalaba bin Azd bin Khalan bin Babalyun bin Saba", who was descended from Qahtan and was the king of Hijaz had placed a Hubal idol onto the roof of the Kaaba. This idol was one of the chief deities of the ruling tribe Quraysh. The idol was made of red agate and shaped like a human, but with the right hand broken off and replaced with a golden hand. When the idol was moved inside the Kaaba, it had seven arrows in front of it, which were used for divination. According to the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', "before the rise of Islam it was revered as a sacred sanctuary and was a site of pilgrimage." Many Muslim and academic historians stress the power and importance of the pre-Islamic Mecca. They depict it as a city grown rich on the proceeds of the spice trade. Patricia Crone believes that this is an exaggeration and that Mecca may only have been an outpost trading with nomads for leather, cloth, and camel butter. Crone argues that if Mecca had been a well-known center of trade, it would have been mentioned by later authors such as Procopius, Nonnosus, or the Syrian church chroniclers writing in Syriac. The town is absent, however, from any geographies or histories written in the three centuries before the rise of Islam.

Ethics

Muhammad

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

is considered one of the prophets in Islam and as a model for followers. Critics such as Sigismund Koelle and former Muslim Ibn Warraq see some of Muhammad's actions as immoral.[Uri Rubin, The Assassination of Kaʿb b. al-Ashraf, Oriens, Vol. 32. (1990), pp. 65–71.]

Muhammad called upon his followers to kill Ka'b. Muhammad ibn Maslama offered his services, collecting four others. By pretending to have turned against Muhammad, Muhammad ibn Maslama and the others enticed Ka'b out of his fortress on a moonlit night,

Age of Muhammad's wife Aisha

According to scriptural Sunni's Hadith sources, Aisha was six or seven years old when she was married to Muhammad and nine when the marriage was consummated.[, , , , , , , , , ][ Six hundred years after Muhammad, Ibn Khallikan recorded that she was nine years old at marriage, and twelve at consummation. Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi, born about 150 years after Muhammad's death, cited Hisham ibn Urwah as saying that she was nine years old at marriage, and twelve at consummation,][Karen Armstrong, ''Muhammad: Prophet for Our Time'', HarperPress, 2006, p. 167 ]

Ethics in the Quran

According to some critics, the morality of the Quran appears to be a moral regression when judged by the standards of the moral traditions of Judaism and Christianity it says that it builds upon. The ''Catholic Encyclopedia'', for example, states that "the ethics of Islam are far inferior to those of Judaism and even more inferior to those of the New Testament" and "that in the ethics of Islam there is a great deal to admire and to approve, is beyond dispute; but of originality or superiority, there is none."

* Critics stated that the Quran 4:34 allows Muslim men to discipline their wives by striking them. There is however confusion amongst translations of Quran with the original Arabic term "wadribuhunna" being translated as "to go away from them", "beat", "strike lightly" and "separate". The film ''Submission (2004 film), Submission'', which rose to fame after the murder of its director Theo van Gogh (film director), Theo van Gogh, critiqued this and similar verses of the Quran by displaying them painted on the bodies of abused Muslim women.

According to some critics, the morality of the Quran appears to be a moral regression when judged by the standards of the moral traditions of Judaism and Christianity it says that it builds upon. The ''Catholic Encyclopedia'', for example, states that "the ethics of Islam are far inferior to those of Judaism and even more inferior to those of the New Testament" and "that in the ethics of Islam there is a great deal to admire and to approve, is beyond dispute; but of originality or superiority, there is none."

* Critics stated that the Quran 4:34 allows Muslim men to discipline their wives by striking them. There is however confusion amongst translations of Quran with the original Arabic term "wadribuhunna" being translated as "to go away from them", "beat", "strike lightly" and "separate". The film ''Submission (2004 film), Submission'', which rose to fame after the murder of its director Theo van Gogh (film director), Theo van Gogh, critiqued this and similar verses of the Quran by displaying them painted on the bodies of abused Muslim women.[Sam Harri]

Who Are the Moderate Muslims?

/ref> Jizya is a tax for "protection" paid by non-Muslims to a Muslim ruler, for the exemption from military service for non-Muslims, and for the permission to practice a non-Muslim faith with some communal autonomy in a Muslim state.[Anver M. Emon, Religious Pluralism and Islamic Law: Dhimmis and Others in the Empire of Law, Oxford University Press, , pp. 99–109.]

online

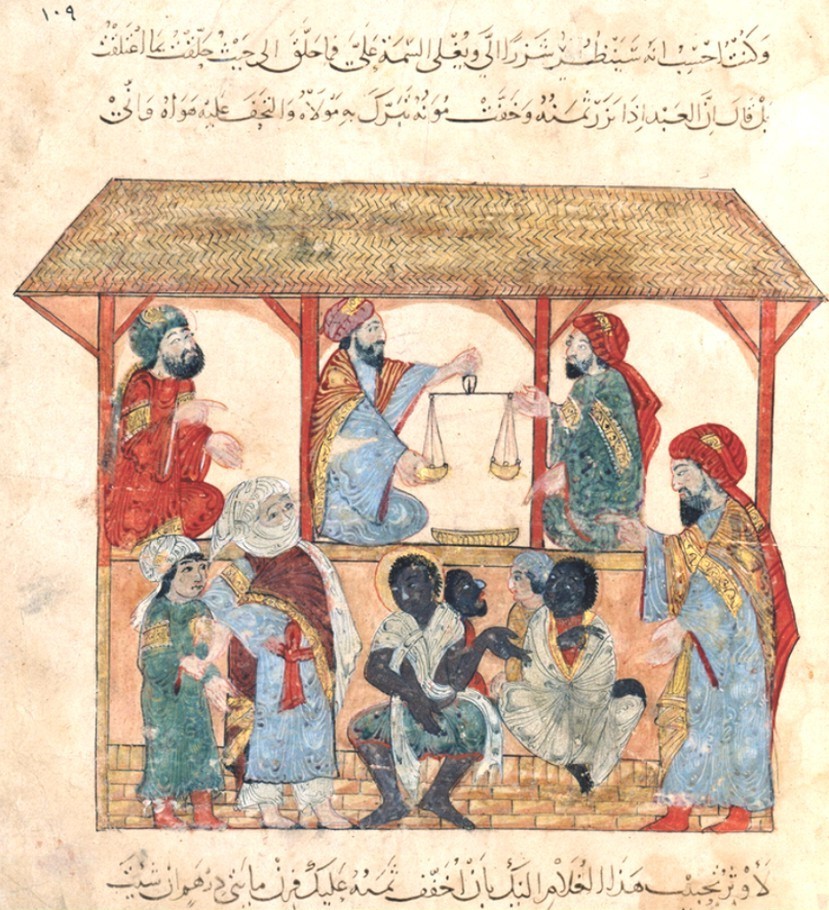

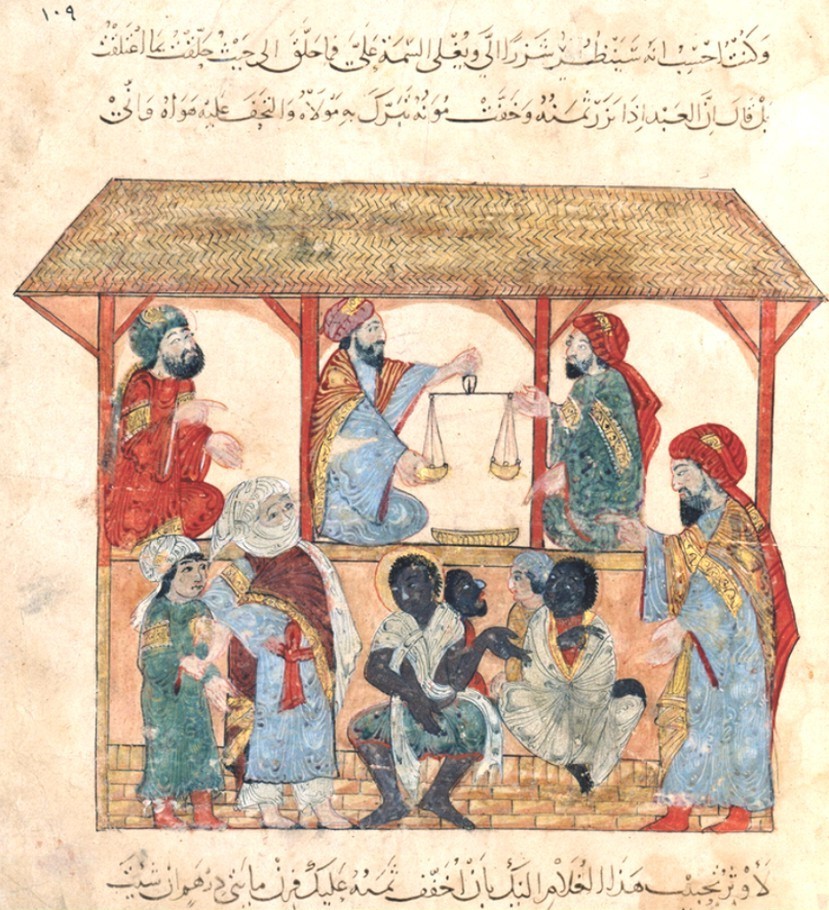

Views on slavery

Bernard Lewis writes: "In one of the sad paradoxes of human history, it was the humanitarian reforms brought by Islam that resulted in a vast development of the History of slavery, slave trade inside, and still more outside, the Islamic empire." He notes that the Islamic injunctions against the enslavement of Muslims led to massive importation of slaves from the outside. According to Patrick Manning (professor), Patrick Manning, Islam by recognizing and codifying the slavery seems to have done more to protect and expand slavery than the reverse.

According to Brockopp, on the other hand, the idea of using alms for the manumission of slaves appears to be unique to the Quran, assuming the traditional interpretation of verses and . Similarly, the practice of freeing slaves in atonement for certain sins appears to be introduced by the Quran (but compare Exod 21:26-7).

Bernard Lewis writes: "In one of the sad paradoxes of human history, it was the humanitarian reforms brought by Islam that resulted in a vast development of the History of slavery, slave trade inside, and still more outside, the Islamic empire." He notes that the Islamic injunctions against the enslavement of Muslims led to massive importation of slaves from the outside. According to Patrick Manning (professor), Patrick Manning, Islam by recognizing and codifying the slavery seems to have done more to protect and expand slavery than the reverse.

According to Brockopp, on the other hand, the idea of using alms for the manumission of slaves appears to be unique to the Quran, assuming the traditional interpretation of verses and . Similarly, the practice of freeing slaves in atonement for certain sins appears to be introduced by the Quran (but compare Exod 21:26-7).[John L Esposito (1998) p. 79][Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, ''Slaves and Slavery'']

Critics argue unlike Western societies which in their opposition to slavery spawned anti-slavery movements whose numbers and enthusiasm often grew out of church groups, no such grass-roots organizations ever developed in Muslim societies. In Muslim politics the state unquestioningly accepted the teachings of Islam and applied them as law. Islam, by sanctioning slavery, also extended legitimacy to the traffic in slaves.

According to Maurice Middleberg, however, "Surat al-Balad, Sura 90 in the Quran states that the righteous path involves 'the freeing of slaves. Murray Gordon characterizes Muhammad's approach to slavery as reformist rather than revolutionary. He did not set out to abolish slavery, but rather to improve the conditions of slaves by urging his followers to treat their slaves humanely and free them as a way of expiating one's sins which some modern Muslim authors have interpreted as indication that Muhammad envisioned a gradual abolition of slavery.

Critics say it was only in the early 20th century (post World War I) that slavery gradually became outlawed and suppressed in Muslim lands, largely due to pressure exerted by Western nations such as UK, Britain and France.[

The issue of slavery in the Islamic world in modern times is controversial. Critics argue there is hard evidence of its existence and destructive effects. Others maintain slavery in central Islamic lands has been virtually extinct since mid-twentieth century, and that reports from Sudan and Somalia showing practice of slavery is in border areas as a result of continuing war and not Islamic belief. In recent years, according to some scholars, there has been a "worrying trend" of "reopening" of the issue of slavery by some conservative Salafi Islamic scholars after its "closing" earlier in the 20th century when Majority Muslim countries, Muslim countries banned slavery and "most Muslim scholars" found the practice "inconsistent with Qur'anic morality".

Shaykh Fadhlalla Haeri of Karbala expressed the view in 1993 that the enforcement of servitude can occur but is restricted to war captives and those born of slaves.

In a 2014 issue of their digital magazine ''Dabiq (magazine), Dabiq'', the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant explicitly claimed religious justification for enslaving Yazidis, Yazidi women.

]

Apostasy

According to sharia, Islamic law,

According to sharia, Islamic law, apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that i ...

is identified by a list of actions such as conversion to another religion, denying the existence of God of Islam, God, rejecting the Prophets of Islam, prophets, mocking God or the prophets, idol worship, rejecting the sharia, or permitting behavior that is forbidden by the sharia, such as Zina, adultery or the eating of forbidden foods or drinking of alcoholic beverages.[Asma Afsaruddin (2013), ''Striving in the Path of God: Jihad and Martyrdom in Islamic Thought'', p. 242. Oxford University Press. .] Wael Hallaq states that "[in] a culture whose lynchpin is religion, religious principles and religious morality, apostasy is in some way equivalent to high treason in the modern nation-state".

Islamic law

Bernard Lewis summarizes:

The four Sunni Islam, Sunni schools of Fiqh, Islamic jurisprudence, as well as Shia Islam, Shi'a scholars, agree on the difference of punishment between male and female. A sane adult male apostate may be executed. A female apostate may be put to death, according to the majority view, or imprisoned until she repents, according to others.

The

Bernard Lewis summarizes:

The four Sunni Islam, Sunni schools of Fiqh, Islamic jurisprudence, as well as Shia Islam, Shi'a scholars, agree on the difference of punishment between male and female. A sane adult male apostate may be executed. A female apostate may be put to death, according to the majority view, or imprisoned until she repents, according to others.

The Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

threatens apostates with punishment in the next world only, the historian W. Heffening states, the traditions however contain the element of death penalty. Muslim scholar Shafi'i interprets verse Quran 2:217 as adducing the main evidence for the death penalty in Quran. The historian Wael Hallaq states the later addition of death penalty "reflects a later reality and does not stand in accord with the deeds of the Prophet." He further states that "nothing in the law governing apostate and apostasy derives from the letter of the holy text."

William Montgomery Watt, in response to a question about Western views of the Islamic Law as being cruel, states that "In Islamic teaching, such penalties may have been suitable for the age in which Muhammad lived. However, as societies have since progressed and become more peaceful and ordered, they are not suitable any longer."

Some contemporary Islamic jurists from both the Sunni and Shia denominations together with Quran only Muslims have argued or issued fatwas that state that either the changing of religion is not punishable or is only punishable under restricted circumstances. For example, Grand Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri argues that no Quranic verse prescribes an earthly penalty for apostasy and adds that it is not improbable that the punishment was prescribed by Muhammad at early Islam due to political conspiracies against Islam and Muslims and not only because of changing the belief or expressing it. Montazeri defines different types of apostasy. He does not hold that a reversion of belief because of investigation and research is punishable by death but prescribes capital punishment for a desertion of Islam out of malice and enmity towards the Muslim.

According to Yohanan Friedmann, an Israeli Islamic Studies scholar, a Muslim may stress tolerant elements of Islam (by for instance adopting the broadest interpretation of Quran 2:256 ("No compulsion is there in religion...") or the humanist approach attributed to Ibrahim al-Nakha'i), without necessarily denying the existence of other ideas in the Medieval Islamic tradition but rather discussing them in their historical context (by for example arguing that "civilizations comparable with the Islamic one, such as the Sassanids and the Byzantines, also punished apostasy with death. Similarly neither Judaism nor Christianity treated apostasy and apostates with any particular kindness").[Yohanan Friedmann, ''Tolerance and Coercion in Islam'', Cambridge University Press, p. 5] Friedmann continues:

Human rights conventions

Some widely held interpretations of Islam are inconsistent with Human Rights conventions that recognize the right to change religion. In particular article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

states:

To implement this, Article 18 (2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states:

The right for Muslims to change their religion is not afforded by the Judicial system of Iran, Iranian Shari'ah law, which specifically forbids it. In 1981, the Iranian representative to the United Nations, Said Rajaie-Khorassani, articulated the position of his country regarding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, by saying that the UDHR was "a secularism, secular understanding of the Judeo-Christian tradition", which could not be implemented by Muslims without trespassing the Islamic law. As a matter of law, on the basis of its obligations as a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ICCPR, Iran is obliged to uphold the right of individuals to practice the religion of their choice and to change religions, including converting from Islam. The prosecution of converts from Islam on the basis of religious edicts that identify apostasy as an offense punishable by death is clearly at variance with this obligation.

Some widely held interpretations of Islam are inconsistent with Human Rights conventions that recognize the right to change religion. In particular article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

states:

To implement this, Article 18 (2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states:

The right for Muslims to change their religion is not afforded by the Judicial system of Iran, Iranian Shari'ah law, which specifically forbids it. In 1981, the Iranian representative to the United Nations, Said Rajaie-Khorassani, articulated the position of his country regarding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, by saying that the UDHR was "a secularism, secular understanding of the Judeo-Christian tradition", which could not be implemented by Muslims without trespassing the Islamic law. As a matter of law, on the basis of its obligations as a state party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, ICCPR, Iran is obliged to uphold the right of individuals to practice the religion of their choice and to change religions, including converting from Islam. The prosecution of converts from Islam on the basis of religious edicts that identify apostasy as an offense punishable by death is clearly at variance with this obligation.[''Sharia as traditionally understood runs counter to the ideas expressed in Article 18']

Religious freedom under Islam

By Henrik Ertner Rasmussen, General Secretary, Danish European Mission Muslim countries such as Sudan and Saudi Arabia, have the death penalty for Apostasy in Islam, apostasy from Islam. These countries have criticized the Universal Declaration of Human Rights for its perceived failure to take into account the cultural and religious context of non-Western world, Western countries. In 1990, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation published a separate Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam compliant with Shari'ah. Although granting many of the rights in the UN declaration, it does not grant Muslims the right to convert to other religions, and restricts freedom of speech to those expressions of it that are not in contravention of the Islamic law.

Abul Ala Maududi, the founder of Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan, Jamaat-e-Islami, wrote a book called Human Rights in Islam (book), Human Rights in Islam, in which he argues that respect for human rights has always been enshrined in Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

law (indeed that the roots of these rights are to be found in Islamic doctrine) and criticizes Western notions that there is an inherent contradiction between the two. Western scholars have, for the most part, rejected Maududi's analysis.[Bielefeldt (2000), p. 104.]

Islam and Violence

The

The September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercia ...

on the United States, and various other acts of Islamic terrorism over the 21st century, have resulted in many non-Muslims' indictment of Islam as a violent religion. In particular, the Quran's teachings on matters of war and peace have become topics of heated discussion in recent years. On the one hand, some critics claim that certain verses of the Quran sanction military action against unbelievers as a whole both during the lifetime of Muhammad and after. The Quran says, "Fight in the name of your religion with those who fight against you."[Sohail H. Hashmi, David Miller, ''Boundaries and Justice: diverse ethical perspectives'', Princeton University Press, p. 197][Ali, Maulana Muhammad]

The Religion of Islam

(6th Edition), Ch V "Jihad" p. 414 "When shall war cease". Published by ''Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam, The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement''[The Qur'anic Commandments Regarding War/Jihad](_blank)

An English rendering of an Urdu article appearing in Basharat-e-Ahmadiyya Vol. I, pp. 228–32, by Dr. Basharat Ahmad; published by the Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement for the Propagation of Islam[David Samuel Margoliouth, Margoliouth, D. S. (1905). Mohammed and the Rise of Islam (Third Edition., pp. 362–63). New York; London: G. P. Putnam's Sons; The Knickerbocker Press.] According to Margoliouth, earlier Caravan raids, attacks on the Meccans and the Jewish tribes of Medina (e.g., the invasion of Banu Qurayza) could be at least plausibly be ascribed to wrongs done to Muhammad or the Islamic community.[Veccia Vaglieri, L. "Khaybar", Encyclopaedia of Islam]

Shibli Numani also sees Khaybar's actions during the Battle of the Trench, and draws particular attention to Banu Nadir's leader Huyayy ibn Akhtab, who had gone to the Banu Qurayza during the battle to instigate them to attack Muhammad.[Nomani (1979), vol. II, pg. 156]

''Jihad'', an List of Islamic terms in Arabic, Islamic term, is a religious duty of Muslims. In Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

, the word ''jihād'' translates as a noun meaning "struggle". ''Jihad'' appears 41 times in the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

and frequently in the idiomatic expression "striving for the sake of God ''(al-jihad fi sabil Allah)''".[, ''Jihad'', p. 571][, ''Jihad'', p. 419] Jihad is an important religious duty for several sects in Islam. A minority among the Sunni Islam, Sunni scholars sometimes refer to this duty as the sixth Five Pillars of Islam, pillar of Islam, though it occupies no such official status.[John Esposito(2005), ''Islam: The Straight Path,'' p. 93] In Twelver Shi'a Islam, however, Jihad is one of the 10 Practices of the Religion. The Quran calls repeatedly for jihad, or holy struggle, resistance, against unbelievers, including, at times, Jews and Christians.Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 Common Era, CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Muhammad in Islam, Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet Divine inspiration, di ...

onward, the word jihad was used in a primarily military sense.

The Quran: (8:12): "...cast terror in their hearts and strike upon their necks."[''Warrant for terror: fatwās of radical Islam and the duty of jihād'', p. 68, Shmuel Bar, 2006] The phrase that they have been "commanded to terrorize the disbelievers" has been cited in motivation of Jihadi terror. One Jihadi cleric has said:

Another aim and objective of jihad is to drive terror in the hearts of the [infidels]. To terrorize them. Did you know that we were commanded in the Qur'an with terrorism? ...Allah said, and prepare for them to the best of your ability with power, and with horses of war. To drive terror in the hearts of my enemies, Allah's enemies, and your enemies. And other enemies which you don't know, only Allah knows them... So we were commanded to drive terror into the hearts of the [infidels], to prepare for them with the best of our abilities with power. Then the Prophet said, nay, the power is your ability to shoot. The power which you are commanded with here, is your ability to shoot. Another aim and objective of jihad is to kill the [infidels], to lessen the population of the [infidels]... it is not right for a Prophet to have captives until he makes the Earth warm with blood... so, you should always seek to lessen the population of the [infidels].