nuclear ordnance on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from

There are two basic types of nuclear weapons: those that derive the majority of their energy from nuclear fission reactions alone, and those that use fission reactions to begin nuclear fusion reactions that produce a large amount of the total energy output.

There are two basic types of nuclear weapons: those that derive the majority of their energy from nuclear fission reactions alone, and those that use fission reactions to begin nuclear fusion reactions that produce a large amount of the total energy output.

All existing nuclear weapons derive some of their explosive energy from nuclear fission reactions. Weapons whose explosive output is exclusively from fission reactions are commonly referred to as atomic bombs or atom bombs (abbreviated as A-bombs). This has long been noted as something of a

All existing nuclear weapons derive some of their explosive energy from nuclear fission reactions. Weapons whose explosive output is exclusively from fission reactions are commonly referred to as atomic bombs or atom bombs (abbreviated as A-bombs). This has long been noted as something of a

Swords of Armageddon: U.S. Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945

" (CD-ROM & download available). PDF. 2,600 pages, Sunnyvale, California, Chuklea Publications, 1995, 2007. (2nd Ed.) All fission reactions generate

The other basic type of nuclear weapon produces a large proportion of its energy in nuclear fusion reactions. Such fusion weapons are generally referred to as thermonuclear weapons or more colloquially as hydrogen bombs (abbreviated as H-bombs), as they rely on fusion reactions between isotopes of

The other basic type of nuclear weapon produces a large proportion of its energy in nuclear fusion reactions. Such fusion weapons are generally referred to as thermonuclear weapons or more colloquially as hydrogen bombs (abbreviated as H-bombs), as they rely on fusion reactions between isotopes of  Fusion reactions do not create fission products, and thus contribute far less to the creation of nuclear fallout than fission reactions, but because all

Fusion reactions do not create fission products, and thus contribute far less to the creation of nuclear fallout than fission reactions, but because all

The system used to deliver a nuclear weapon to its target is an important factor affecting both nuclear weapon design and

The system used to deliver a nuclear weapon to its target is an important factor affecting both nuclear weapon design and  Preferable from a strategic point of view is a nuclear weapon mounted on a

Preferable from a strategic point of view is a nuclear weapon mounted on a

Different forms of nuclear weapons delivery (see above) allow for different types of nuclear strategies. The goals of any strategy are generally to make it difficult for an enemy to launch a pre-emptive strike against the weapon system and difficult to defend against the delivery of the weapon during a potential conflict. This can mean keeping weapon locations hidden, such as deploying them on

Different forms of nuclear weapons delivery (see above) allow for different types of nuclear strategies. The goals of any strategy are generally to make it difficult for an enemy to launch a pre-emptive strike against the weapon system and difficult to defend against the delivery of the weapon during a potential conflict. This can mean keeping weapon locations hidden, such as deploying them on

"The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Better,"

''Adelphi Papers'', no. 171 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1981). Interest in proliferation and the stability-instability paradox that it generates continues to this day, with ongoing debate about indigenous Japanese and

Islam, Terror and the Second Nuclear Age

," ''New York Times Magazine'' (October 29, 2006). Since 1996, the United States has had a policy of allowing the targeting of its nuclear weapons at terrorists armed with

Because they are weapons of mass destruction, the proliferation and possible use of nuclear weapons are important issues in international relations and diplomacy. In most countries, the use of nuclear force can only be authorized by the

Because they are weapons of mass destruction, the proliferation and possible use of nuclear weapons are important issues in international relations and diplomacy. In most countries, the use of nuclear force can only be authorized by the  In 1957, the

In 1957, the

Status of Signature and Ratification

". Accessed May 27, 2010. Of the "Annex 2" states whose ratification of the CTBT is required before it enters into force, China, Egypt, Iran, Israel, and the United States have signed but not ratified the Treaty. India, North Korea, and Pakistan have not signed the Treaty. Additional treaties and agreements have governed nuclear weapons stockpiles between the countries with the two largest stockpiles, the United States and the Soviet Union, and later between the United States and Russia. These include treaties such as In 1996, the

In 1996, the

Nuclear disarmament refers to both the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons and to the end state of a nuclear-free world, in which nuclear weapons are eliminated.

Beginning with the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty and continuing through the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, there have been many treaties to limit or reduce nuclear weapons testing and stockpiles. The 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty has as one of its explicit conditions that all signatories must "pursue negotiations in good faith" towards the long-term goal of "complete disarmament". The nuclear-weapon states have largely treated that aspect of the agreement as "decorative" and without force.

Only one country—South Africa—has ever fully renounced nuclear weapons they had independently developed. The former Soviet republics of

Nuclear disarmament refers to both the act of reducing or eliminating nuclear weapons and to the end state of a nuclear-free world, in which nuclear weapons are eliminated.

Beginning with the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty and continuing through the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, there have been many treaties to limit or reduce nuclear weapons testing and stockpiles. The 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty has as one of its explicit conditions that all signatories must "pursue negotiations in good faith" towards the long-term goal of "complete disarmament". The nuclear-weapon states have largely treated that aspect of the agreement as "decorative" and without force.

Only one country—South Africa—has ever fully renounced nuclear weapons they had independently developed. The former Soviet republics of  In January 1986, Soviet leader

In January 1986, Soviet leader

Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the

Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the

Over 500 atmospheric nuclear weapons tests were conducted at various sites around the world from 1945 to 1980. Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when the Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test at the

Over 500 atmospheric nuclear weapons tests were conducted at various sites around the world from 1945 to 1980. Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when the Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test at the

Some scientists estimate that a nuclear war with 100 Hiroshima-size nuclear explosions on cities could cost the lives of tens of millions of people from long-term climatic effects alone. The climatology hypothesis is that ''if'' each city firestorms, a great deal of soot could be thrown up into the atmosphere which could blanket the earth, cutting out sunlight for years on end, causing the disruption of food chains, in what is termed a

Some scientists estimate that a nuclear war with 100 Hiroshima-size nuclear explosions on cities could cost the lives of tens of millions of people from long-term climatic effects alone. The climatology hypothesis is that ''if'' each city firestorms, a great deal of soot could be thrown up into the atmosphere which could blanket the earth, cutting out sunlight for years on end, causing the disruption of food chains, in what is termed a

The Effects of Nuclear Weapons (third edition).

' Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1977

Available online (PDF).

*

'. Departments of the Army, Navy, and Air Force: Washington, D.C., 1996 * Hansen, Chuck. ''U.S. Nuclear Weapons: The Secret History.'' Arlington, TX: Aerofax, 1988 * Hansen, Chuck,

Swords of Armageddon: U.S. nuclear weapons development since 1945

(CD-ROM & download available). PDF. 2,600 pages, Sunnyvale, California, Chucklea Publications, 1995, 2007. (2nd Ed.) * Holloway, David. ''Stalin and the Bomb''. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994. * The Manhattan Engineer District,

The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

(1946) * Jean-Hugues Oppel, ''Réveillez le président'', Éditions Payot et rivages, 2007 (). The book is a fiction about the

Atomic Energy for Military Purposes.

' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1945. (

The Effects of Nuclear War

'. Office of Technology Assessment, May 1979. * Rhodes, Richard. ''Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb''. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995. * Rhodes, Richard. ''

Nuclear Weapon Archive from Carey Sublette

is a reliable source of information and has links to other sources and an informativ

* Th

Federation of American Scientists

provide solid information on weapons of mass destruction, includin

nuclear weapons

and thei

Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

– contains many resources related to nuclear weapons, including a historical and technical overview and searchable bibliography of web and print resources. * Video archive o

US, Soviet, UK, Chinese and French Nuclear Weapon Testing

a

sonicbomb.com

The National Museum of Nuclear Science & History (United States)

– located in Albuquerque, New Mexico; a Smithsonian Affiliate Museum

The Manhattan Project: Making the Atomic Bomb

at AtomicArchive.com

Los Alamos National Laboratory: History

(U.S. nuclear history)

''Race for the Superbomb''

PBS website on the history of the H-bomb

Recordings of recollections of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The Woodrow Wilson Center's Nuclear Proliferation International History Project

or NPIHP is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews and other empirical sources.

NUKEMAP3D

– a 3D nuclear weapons effects simulator powered by Google Maps. {{Authority control Weapons and ammunition introduced in 1945 American inventions Articles containing video clips Bombs Nuclear bombs

nuclear reaction

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, a nuclear reaction is a process in which two atomic nucleus, nuclei, or a nucleus and an external subatomic particle, collide to produce one or more new nuclides. Thus, a nuclear reaction must cause a t ...

s, either fission

Fission, a splitting of something into two or more parts, may refer to:

* Fission (biology), the division of a single entity into two or more parts and the regeneration of those parts into separate entities resembling the original

* Nuclear fissio ...

(fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

), producing a nuclear explosion

A nuclear explosion is an explosion that occurs as a result of the rapid release of energy from a high-speed nuclear reaction. The driving reaction may be nuclear fission or nuclear fusion or a multi-stage cascading combination of the two, t ...

. Both bomb types release large quantities of energy from relatively small amounts of matter.

The first test of a fission ("atomic") bomb released an amount of energy approximately equal to . The first thermonuclear ("hydrogen") bomb test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film), ...

released energy approximately equal to . Nuclear bombs have had yields between 10 tons TNT (the W54

The W54 (also known as the Mark 54 or B54) was a tactical nuclear warhead developed by the United States in the late 1950s. The weapon is notable for being the smallest nuclear weapon in both weight and yield to have entered US service. It was ...

) and 50 megatons for the Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei Sa ...

(see TNT equivalent). A thermonuclear weapon weighing as little as can release energy equal to more than .

A nuclear device no larger than a conventional bomb can devastate an entire city by blast, fire, and radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

. Since they are weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natura ...

, the proliferation of nuclear weapons

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

is a focus of international relations

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such as ...

policy. Nuclear weapons have been deployed twice in war, by the United States against the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

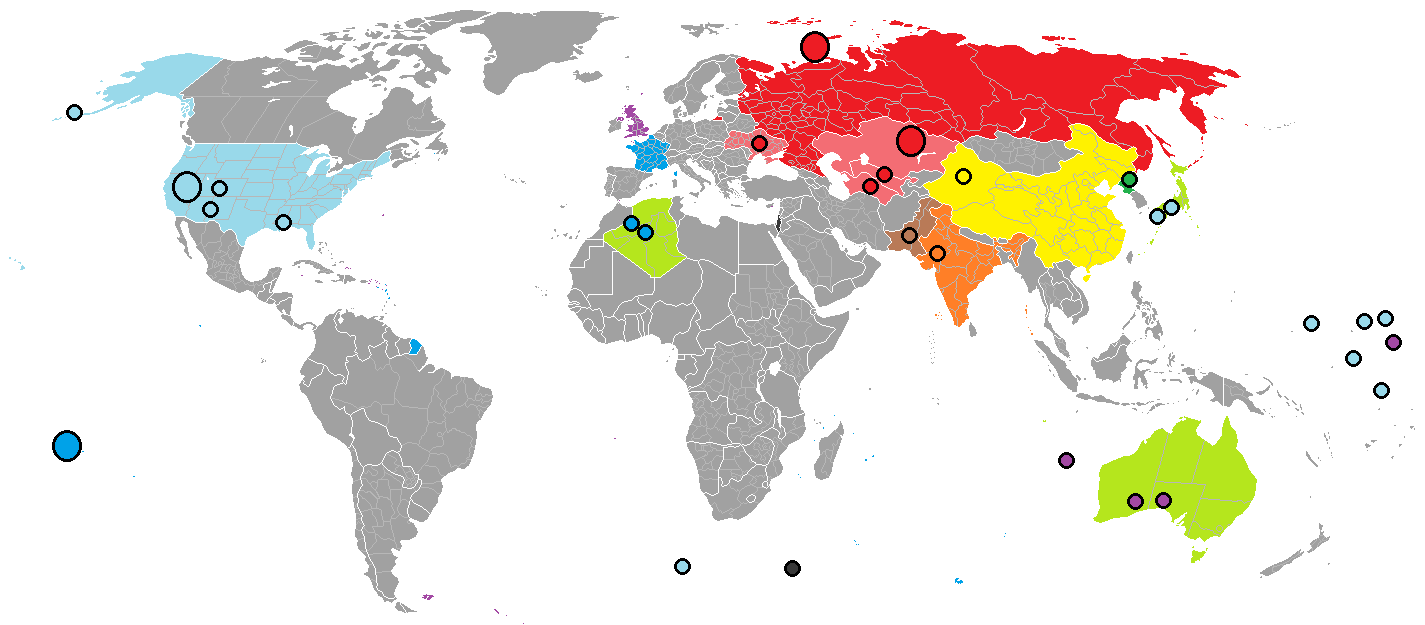

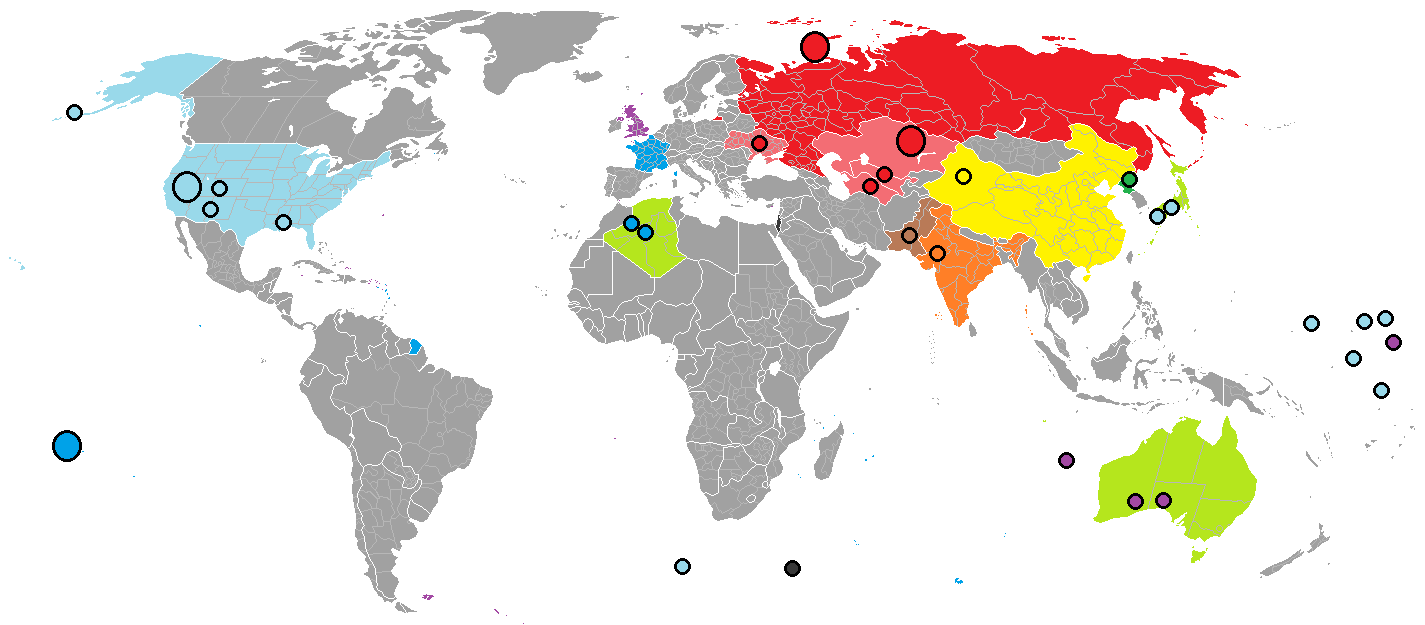

Testing and deployment

Nuclear weapons have only twice been used in war, both times by theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

against Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

near the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. On August 6, 1945, the U.S. Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

detonated a uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

gun-type fission bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

; three days later, on August 9, the U.S. Army Air Forces detonated a plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

implosion-type fission bomb nicknamed "Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

" over the Japanese city of Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

. These bombings caused injuries that resulted in the deaths of approximately 200,000 civilians

Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not "combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant, b ...

and military personnel

Military personnel are members of the state's armed forces. Their roles, pay, and obligations differ according to their military branch (army, navy, marines, air force, space force, and coast guard), rank (officer, non-commissioned officer, or e ...

. The ethics of these bombings and their role in Japan's surrender are subjects of debate.

Since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

, nuclear weapons have been detonated over 2,000 times for testing

An examination (exam or evaluation) or test is an educational assessment intended to measure a test-taker's knowledge, skill, aptitude, physical fitness, or classification in many other topics (e.g., beliefs). A test may be administered verba ...

and demonstration. Only a few nations possess such weapons or are suspected of seeking them. The only countries known to have detonated nuclear weapons—and acknowledge possessing them—are (chronologically by date of first test) the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

(succeeded as a nuclear power by Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

), the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, and North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

. Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

is believed to possess nuclear weapons, though, in a policy of deliberate ambiguity

A policy of deliberate ambiguity (also known as a policy of strategic ambiguity, ''strategic uncertainty'') is the practice by a government of being intentionally ambiguous on certain aspects of its foreign policy. It may be useful if the country ...

, it does not acknowledge having them. Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

are nuclear weapons sharing

Nuclear sharing is a concept in NATO's policy of nuclear deterrence, which allows member countries without nuclear weapons of their own to participate in the planning for the use of nuclear weapons by NATO. In particular, it provides for the arm ...

states. South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

is the only country to have independently developed and then renounced and dismantled its nuclear weapons.

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation ...

aims to reduce the spread of nuclear weapons, but its effectiveness has been questioned. Modernisation of weapons continues to this day.

Types

There are two basic types of nuclear weapons: those that derive the majority of their energy from nuclear fission reactions alone, and those that use fission reactions to begin nuclear fusion reactions that produce a large amount of the total energy output.

There are two basic types of nuclear weapons: those that derive the majority of their energy from nuclear fission reactions alone, and those that use fission reactions to begin nuclear fusion reactions that produce a large amount of the total energy output.

Fission weapons

misnomer

A misnomer is a name that is incorrectly or unsuitably applied. Misnomers often arise because something was named long before its correct nature was known, or because an earlier form of something has been replaced by a later form to which the name ...

, as their energy comes from the nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

of the atom, just as it does with fusion weapons.

In fission weapons, a mass of fissile material

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be ty ...

( enriched uranium or plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibi ...

) is forced into supercriticality

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fissio ...

—allowing an exponential growth

Exponential growth is a process that increases quantity over time. It occurs when the instantaneous rate of change (that is, the derivative) of a quantity with respect to time is proportional to the quantity itself. Described as a function, a q ...

of nuclear chain reaction

In nuclear physics, a nuclear chain reaction occurs when one single nuclear reaction causes an average of one or more subsequent nuclear reactions, thus leading to the possibility of a self-propagating series of these reactions. The specific nu ...

s—either by shooting one piece of sub-critical material into another (the "gun" method) or by compression of a sub-critical sphere or cylinder of fissile material using chemically fueled explosive lenses. The latter approach, the "implosion" method, is more sophisticated and more efficient (smaller, less massive, and requiring less of the expensive fissile fuel) than the former.

A major challenge in all nuclear weapon designs is to ensure that a significant fraction of the fuel is consumed before the weapon destroys itself. The amount of energy released by fission bombs can range from the equivalent of just under a ton to upwards of 500,000 tons (500 kilotons) of TNT ().Hansen, Chuck. ''U.S. Nuclear Weapons: The Secret History.'' San Antonio, TX: Aerofax, 1988; and the more-updated Hansen, Chuck,Swords of Armageddon: U.S. Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945

" (CD-ROM & download available). PDF. 2,600 pages, Sunnyvale, California, Chuklea Publications, 1995, 2007. (2nd Ed.) All fission reactions generate

fission products

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the release ...

, the remains of the split atomic nuclei. Many fission products are either highly radioactive

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is consid ...

(but short-lived) or moderately radioactive (but long-lived), and as such, they are a serious form of radioactive contamination. Fission products are the principal radioactive component of nuclear fallout. Another source of radioactivity is the burst of free neutrons produced by the weapon. When they collide with other nuclei in the surrounding material, the neutrons transmute those nuclei into other isotopes, altering their stability and making them radioactive.

The most commonly used fissile materials for nuclear weapons applications have been uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exis ...

and plutonium-239. Less commonly used has been uranium-233. Neptunium-237 and some isotopes of americium

Americium is a synthetic radioactive chemical element with the symbol Am and atomic number 95. It is a transuranic member of the actinide series, in the periodic table located under the lanthanide element europium, and thus by analogy was na ...

may be usable for nuclear explosives as well, but it is not clear that this has ever been implemented, and their plausible use in nuclear weapons is a matter of dispute.

Fusion weapons

hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

(deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

and tritium). All such weapons derive a significant portion of their energy from fission reactions used to "trigger" fusion reactions, and fusion reactions can themselves trigger additional fission reactions.

Only six countries—United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, United Kingdom, China, France, and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

—have conducted thermonuclear weapon tests. Whether India has detonated a "true" multi-staged thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

is controversial. North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

claims to have tested a fusion weapon , though this claim is disputed. Thermonuclear weapons are considered much more difficult to successfully design and execute than primitive fission weapons. Almost all of the nuclear weapons deployed today use the thermonuclear design because it is more efficient.

Thermonuclear bombs work by using the energy of a fission bomb to compress and heat fusion fuel. In the Teller-Ulam design, which accounts for all multi-megaton yield hydrogen bombs, this is accomplished by placing a fission bomb and fusion fuel ( tritium, deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol or deuterium, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two Stable isotope ratio, stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being Hydrogen atom, protium, or hydrogen-1). The atomic nucleus, nucleus of a deuterium ato ...

, or lithium deuteride

Lithium hydride is an inorganic compound with the formula Li H. This alkali metal hydride is a colorless solid, although commercial samples are grey. Characteristic of a salt-like (ionic) hydride, it has a high melting point, and it is not solub ...

) in proximity within a special, radiation-reflecting container. When the fission bomb is detonated, gamma ray

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or \gamma), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically ...

s and X-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

s emitted first compress the fusion fuel, then heat it to thermonuclear temperatures. The ensuing fusion reaction creates enormous numbers of high-speed neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

s, which can then induce fission in materials not normally prone to it, such as depleted uranium

Depleted uranium (DU; also referred to in the past as Q-metal, depletalloy or D-38) is uranium with a lower content of the fissile isotope than natural uranium.: "Depleted uranium possesses only 60% of the radioactivity of natural uranium, hav ...

. Each of these components is known as a "stage", with the fission bomb as the "primary" and the fusion capsule as the "secondary". In large, megaton-range hydrogen bombs, about half of the yield comes from the final fissioning of depleted uranium.

Virtually all thermonuclear weapons deployed today use the "two-stage" design described above, but it is possible to add additional fusion stages—each stage igniting a larger amount of fusion fuel in the next stage. This technique can be used to construct thermonuclear weapons of arbitrarily large yield. This is in contrast to fission bombs, which are limited in their explosive power due to criticality danger (premature nuclear chain reaction caused by too-large amounts of pre-assembled fissile fuel). The largest nuclear weapon ever detonated, the Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei Sa ...

of the USSR, which released an energy equivalent of over , was a three-stage weapon. Most thermonuclear weapons are considerably smaller than this, due to practical constraints from missile warhead space and weight requirements.

Fusion reactions do not create fission products, and thus contribute far less to the creation of nuclear fallout than fission reactions, but because all

Fusion reactions do not create fission products, and thus contribute far less to the creation of nuclear fallout than fission reactions, but because all thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

s contain at least one fission

Fission, a splitting of something into two or more parts, may refer to:

* Fission (biology), the division of a single entity into two or more parts and the regeneration of those parts into separate entities resembling the original

* Nuclear fissio ...

stage, and many high-yield thermonuclear devices have a final fission stage, thermonuclear weapons can generate at least as much nuclear fallout as fission-only weapons. Furthermore, high yield thermonuclear explosions (most dangerously ground bursts) have the force to lift radioactive debris upwards past the tropopause into the stratosphere

The stratosphere () is the second layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is an atmospheric layer composed of stratified temperature layers, with the warm layers of air ...

, where the calm non-turbulent winds permit the debris to travel great distances from the burst, eventually settling and unpredictably contaminating areas far removed from the target of the explosion.

Other types

There are other types of nuclear weapons as well. For example, a boosted fission weapon is a fission bomb that increases its explosive yield through a small number of fusion reactions, but it is not a fusion bomb. In the boosted bomb, the neutrons produced by the fusion reactions serve primarily to increase the efficiency of the fission bomb. There are two types of boosted fission bomb: internally boosted, in which a deuterium-tritium mixture is injected into the bomb core, and externally boosted, in which concentric shells of lithium-deuteride and depleted uranium are layered on the outside of the fission bomb core. The external method of boosting enabled theUSSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

to field the first partially-thermonuclear weapons, but it is now obsolete because it demands a spherical bomb geometry, which was adequate during the 1950s arms race when bomber aircraft were the only available delivery vehicles.

The detonation of any nuclear weapon is accompanied by a blast of neutron radiation. Surrounding a nuclear weapon with suitable materials (such as cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with the symbol Co and atomic number 27. As with nickel, cobalt is found in the Earth's crust only in a chemically combined form, save for small deposits found in alloys of natural meteoric iron. The free element, pr ...

or gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

) creates a weapon known as a salted bomb

A salted bomb is a nuclear weapon designed to function as a radiological weapon, producing enhanced quantities of radioactive fallout, rendering a large area uninhabitable. The term is derived both from the means of their manufacture, which invol ...

. This device can produce exceptionally large quantities of long-lived radioactive contamination. It has been conjectured that such a device could serve as a "doomsday weapon" because such a large quantity of radioactivities with half-lives of decades, lifted into the stratosphere where winds would distribute it around the globe, would make all life on the planet extinct.

In connection with the Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), derisively nicknamed the "''Star Wars'' program", was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic strategic nuclear weapons (intercontinental ballistic ...

, research into the nuclear pumped laser was conducted under the DOD program Project Excalibur

Project Excalibur was a Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) Cold Warera research program to develop an X-ray laser system as a ballistic missile defense (BMD) for the United States. The concept involved packing large numbers of expendab ...

but this did not result in a working weapon. The concept involves the tapping of the energy of an exploding nuclear bomb to power a single-shot laser that is directed at a distant target.

During the Starfish Prime

Starfish Prime was a high-altitude nuclear test conducted by the United States, a joint effort of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and the Defense Atomic Support Agency. It was launched from Johnston Atoll on July 9, 1962, and was the larges ...

high-altitude nuclear test in 1962, an unexpected effect was produced which is called a nuclear electromagnetic pulse

A nuclear electromagnetic pulse (nuclear EMP or NEMP) is a burst of electromagnetic radiation created by a nuclear explosion. The resulting rapidly varying electric and magnetic fields may couple with electrical and electronic systems to produce ...

. This is an intense flash of electromagnetic energy produced by a rain of high-energy electrons which in turn are produced by a nuclear bomb's gamma rays. This flash of energy can permanently destroy or disrupt electronic equipment if insufficiently shielded. It has been proposed to use this effect to disable an enemy's military and civilian infrastructure as an adjunct to other nuclear or conventional military operations. By itself it could as well be useful to terrorists for crippling a nation's economic electronics-based infrastructure. Because the effect is most effectively produced by high altitude nuclear detonations (by military weapons delivered by air, though ground bursts also produce EMP effects over a localized area), it can produce damage to electronics over a wide, even continental, geographical area.

Research has been done into the possibility of pure fusion bombs: nuclear weapons that consist of fusion reactions without requiring a fission bomb to initiate them. Such a device might provide a simpler path to thermonuclear weapons than one that required the development of fission weapons first, and pure fusion weapons would create significantly less nuclear fallout than other thermonuclear weapons because they would not disperse fission products. In 1998, the United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United Stat ...

divulged that the United States had, "...made a substantial investment" in the past to develop pure fusion weapons, but that, "The U.S. does not have and is not developing a pure fusion weapon", and that, "No credible design for a pure fusion weapon resulted from the DOE investment".

Nuclear isomers

A nuclear isomer is a metastable state of an atomic nucleus, in which one or more nucleons (protons or neutrons) occupy higher energy levels than in the ground state of the same nucleus. "Metastable" describes nuclei whose excited states have ha ...

provide a possible pathway to fissionless fusion bombs. These are naturally occurring isotopes

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers (mass numbers) ...

(178m2Hf being a prominent example) which exist in an elevated energy state. Mechanisms to release this energy as bursts of gamma radiation (as in the hafnium controversy The hafnium controversy is a debate over the possibility of 'triggering' rapid energy releases, via gamma ray emission, from a nuclear isomer of hafnium, 178m2Hf. The energy release is potentially 5 orders of magnitude (100,000 times) more energetic ...

) have been proposed as possible triggers for conventional thermonuclear reactions.

Antimatter, which consists of particles resembling ordinary matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic partic ...

particles in most of their properties but having opposite electric charge

Electric charge is the physical property of matter that causes charged matter to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be ''positive'' or ''negative'' (commonly carried by protons and electrons respe ...

, has been considered as a trigger mechanism for nuclear weapons. A major obstacle is the difficulty of producing antimatter in large enough quantities, and there is no evidence that it is feasible beyond the military domain. However, the U.S. Air Force funded studies of the physics of antimatter in the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, and began considering its possible use in weapons, not just as a trigger, but as the explosive itself. A fourth generation nuclear weapon design is related to, and relies upon, the same principle as antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion

Antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion (also antiproton-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion) is a variation of nuclear pulse propulsion based upon the injection of antimatter into a mass of nuclear fuel to initiate a nuclear chain reaction f ...

.

Most variation in nuclear weapon design is for the purpose of achieving different yields for different situations, and in manipulating design elements to attempt to minimize weapon size, radiation hardness

Radiation hardening is the process of making electronic components and circuits resistant to damage or malfunction caused by high levels of ionizing radiation (particle radiation and high-energy electromagnetic radiation), especially for environ ...

or requirements for special materials, especially fissile fuel or tritium.

Tactical nuclear weapons

Some nuclear weapons are designed for special purposes; most of these are for non-strategic (decisively war-winning) purposes and are referred to as tactical nuclear weapons. The neutron bomb purportedly conceived by Sam Cohen is a thermonuclear weapon that yields a relatively small explosion but a relatively large amount of neutronradiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

. Such a weapon could, according to tacticians, be used to cause massive biological casualties while leaving inanimate infrastructure mostly intact and creating minimal fallout. Because high energy neutrons are capable of penetrating dense matter, such as tank armor, neutron warheads were procured in the 1980s (though not deployed in Europe, as intended, over the objections of NATO allies) for use as tactical payloads for US Army artillery shells (200 mm W79 and 155 mm W82

The W82 (also known as the XM785 shell) was a low-yield tactical nuclear warhead developed by the United States and designed to be used in a 155 mm artillery shell. It was conceived as a more flexible replacement for the W48, the previous gene ...

) and short range missile

A short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) is a ballistic missile with a range of about or less. In past and potential regional conflicts, these missiles have been and would be used because of the short distances between some countries and their relat ...

forces. Soviet authorities announced similar intentions for neutron warhead deployment in Europe; indeed claimed to have originally invented the neutron bomb, but their deployment on USSR tactical nuclear forces is unverifiable.

A type of nuclear explosive most suitable for use by ground special forces was the Special Atomic Demolition Munition

The Special Atomic Demolition Munition (SADM), also known as the XM129 and XM159 Atomic Demolition Charges, and the B54 bomb was a nuclear man-portable atomic demolition munition (ADM) system fielded by the US military from the 1960s to 1980s ...

, or SADM, sometimes popularly known as a suitcase nuke

A suitcase nuclear device (also suitcase nuke, suitcase bomb, backpack nuke, snuke, mini-nuke, and pocket nuke) is a tactical nuclear weapon that is portable enough that it could use a suitcase as its delivery method.

Both the United States and ...

. This is a nuclear bomb that is man-portable, or at least truck-portable, and though of a relatively small yield (one or two kilotons) is sufficient to destroy important tactical targets such as bridges, dams, tunnels, important military or commercial installations, etc. either behind enemy lines or pre-emptively on friendly territory soon to be overtaken by invading enemy forces. These weapons require plutonium fuel and are particularly "dirty". Obviously they also demand especially stringent security precautions in their storage and deployment.

Small "tactical" nuclear weapons were deployed for use as antiaircraft weapons. Examples include the USAF AIR-2 Genie, the AIM-26 Falcon

The AIM-26 Falcon was a larger, more powerful version of the AIM-4 Falcon air-to-air missile built by Hughes. It is the only guided American air-to-air missile with a nuclear warhead to be produced; the unguided AIR-2 Genie rocket was also nuclea ...

and US Army Nike Hercules

The Nike Hercules, initially designated SAM-A-25 and later MIM-14, was a surface-to-air missile (SAM) used by U.S. and NATO armed forces for medium- and high-altitude long-range air defense. It was normally armed with the W31 nuclear warhead, bu ...

. Missile interceptors such as the Sprint

Sprint may refer to:

Aerospace

*Spring WS202 Sprint, a Canadian aircraft design

*Sprint (missile), an anti-ballistic missile

Automotive and motorcycle

*Alfa Romeo Sprint, automobile produced by Alfa Romeo between 1976 and 1989

*Chevrolet Sprint, ...

and the Spartan also used small nuclear warheads (optimized to produce neutron or X-ray flux) but were for use against enemy strategic warheads.

Other small, or tactical, nuclear weapons were deployed by naval forces for use primarily as antisubmarine weapons. These included nuclear depth bombs or nuclear armed torpedoes. Nuclear mines for use on land or at sea are also possibilities.

Weapons delivery

The system used to deliver a nuclear weapon to its target is an important factor affecting both nuclear weapon design and

The system used to deliver a nuclear weapon to its target is an important factor affecting both nuclear weapon design and nuclear strategy

Nuclear strategy involves the development of doctrines and strategies for the production and use of nuclear weapons.

As a sub-branch of military strategy, nuclear strategy attempts to match nuclear weapons as means to political ends. In additi ...

. The design, development, and maintenance of delivery systems are among the most expensive parts of a nuclear weapons program; they account, for example, for 57% of the financial resources spent by the United States on nuclear weapons projects since 1940.

The simplest method for delivering a nuclear weapon is a gravity bomb dropped from aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines ...

; this was the method used by the United States against Japan. This method places few restrictions on the size of the weapon. It does, however, limit attack range, response time to an impending attack, and the number of weapons that a country can field at the same time. With miniaturization, nuclear bombs can be delivered by both strategic bomber

A strategic bomber is a medium- to long-range penetration bomber aircraft designed to drop large amounts of air-to-ground weaponry onto a distant target for the purposes of debilitating the enemy's capacity to wage war. Unlike tactical bombers, ...

s and tactical fighter-bomber

A fighter-bomber is a fighter aircraft that has been modified, or used primarily, as a light bomber or attack aircraft. It differs from bomber and attack aircraft primarily in its origins, as a fighter that has been adapted into other roles, wh ...

s. This method is the primary means of nuclear weapons delivery; the majority of U.S. nuclear warheads, for example, are free-fall gravity bombs, namely the B61.

Preferable from a strategic point of view is a nuclear weapon mounted on a

Preferable from a strategic point of view is a nuclear weapon mounted on a missile

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket i ...

, which can use a ballistic

Ballistics may refer to:

Science

* Ballistics, the science that deals with the motion, behavior, and effects of projectiles

** Forensic ballistics, the science of analyzing firearm usage in crimes

** Internal ballistics, the study of the proce ...

trajectory to deliver the warhead over the horizon. Although even short-range missiles allow for a faster and less vulnerable attack, the development of long-range intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

s (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missile

A submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is a ballistic missile capable of being launched from submarines. Modern variants usually deliver multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), each of which carries a nuclear warhead ...

s (SLBMs) has given some nations the ability to plausibly deliver missiles anywhere on the globe with a high likelihood of success.

More advanced systems, such as multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle

A multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) is an exoatmospheric ballistic missile payload containing several warheads, each capable of being aimed to hit a different target. The concept is almost invariably associated with in ...

s (MIRVs), can launch multiple warheads at different targets from one missile, reducing the chance of a successful missile defense

Missile defense is a system, weapon, or technology involved in the detection, tracking, interception, and also the destruction of attacking missiles. Conceived as a defense against nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), ...

. Today, missiles are most common among systems designed for delivery of nuclear weapons. Making a warhead small enough to fit onto a missile, though, can be difficult.

Tactical weapons

A tactical nuclear weapon (TNW) or non-strategic nuclear weapon (NSNW) is a nuclear weapon that is designed to be used on a battlefield in military situations, mostly with friendly forces in proximity and perhaps even on contested friendly territo ...

have involved the most variety of delivery types, including not only gravity bombs and missiles but also artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

shells, land mines, and nuclear depth charge

A nuclear depth bomb is the nuclear equivalent of the conventional depth charge, and can be used in anti-submarine warfare for attacking submerged submarines. The Royal Navy, Soviet Navy, and United States Navy had nuclear depth bombs in their ...

s and torpedoes

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

for anti-submarine warfare

Anti-submarine warfare (ASW, or in older form A/S) is a branch of underwater warfare that uses surface warships, aircraft, submarines, or other platforms, to find, track, and deter, damage, or destroy enemy submarines. Such operations are t ...

. An atomic mortar has been tested by the United States. Small, two-man portable tactical weapons (somewhat misleadingly referred to as suitcase bomb

A suitcase nuclear device (also suitcase nuke, suitcase bomb, backpack nuke, snuke, mini-nuke, and pocket nuke) is a tactical nuclear weapon that is portable enough that it could use a suitcase as its delivery method.

Both the United States and ...

s), such as the Special Atomic Demolition Munition

The Special Atomic Demolition Munition (SADM), also known as the XM129 and XM159 Atomic Demolition Charges, and the B54 bomb was a nuclear man-portable atomic demolition munition (ADM) system fielded by the US military from the 1960s to 1980s ...

, have been developed, although the difficulty of combining sufficient yield with portability limits their military utility.

Nuclear strategy

Nuclear warfare strategy is a set of policies that deal with preventing or fighting a nuclear war. The policy of trying to prevent an attack by a nuclear weapon from another country by threatening nuclear retaliation is known as the strategy ofnuclear deterrence

Deterrence theory refers to the scholarship and practice of how threats or limited force by one party can convince another party to refrain from initiating some other course of action. The topic gained increased prominence as a military strategy ...

. The goal in deterrence is to always maintain a second strike capability (the ability of a country to respond to a nuclear attack with one of its own) and potentially to strive for first strike First strike most commonly refers to:

* Pre-emptive nuclear strike

* Pre-emptive war

First strike may also refer to:

* ''First Strike'' (1996 film), also known as ''Jackie Chan's First Strike'' or ''Police Story 4: First Strike'', an action movie ...

status (the ability to destroy an enemy's nuclear forces before they could retaliate). During the Cold War, policy and military theorists considered the sorts of policies that might prevent a nuclear attack, and they developed game theory

Game theory is the study of mathematical models of strategic interactions among rational agents. Myerson, Roger B. (1991). ''Game Theory: Analysis of Conflict,'' Harvard University Press, p.&nbs1 Chapter-preview links, ppvii–xi It has appli ...

models that could lead to stable deterrence conditions.

Different forms of nuclear weapons delivery (see above) allow for different types of nuclear strategies. The goals of any strategy are generally to make it difficult for an enemy to launch a pre-emptive strike against the weapon system and difficult to defend against the delivery of the weapon during a potential conflict. This can mean keeping weapon locations hidden, such as deploying them on

Different forms of nuclear weapons delivery (see above) allow for different types of nuclear strategies. The goals of any strategy are generally to make it difficult for an enemy to launch a pre-emptive strike against the weapon system and difficult to defend against the delivery of the weapon during a potential conflict. This can mean keeping weapon locations hidden, such as deploying them on submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s or land mobile transporter erector launcher

A transporter erector launcher (TEL) is a missile vehicle with an integrated tractor unit that can carry, elevate to firing position and launch one or more missiles.

History

Such vehicles exist for both surface-to-air missiles and surface-to-su ...

s whose locations are difficult to track, or it can mean protecting weapons by burying them in hardened missile silo bunkers. Other components of nuclear strategies included using missile defenses to destroy the missiles before they land, or implementing civil defense

Civil defense ( en, region=gb, civil defence) or civil protection is an effort to protect the citizens of a state (generally non-combatants) from man-made and natural disasters. It uses the principles of emergency operations: prevention, miti ...

measures using early-warning systems to evacuate citizens to safe areas before an attack.

Weapons designed to threaten large populations or to deter attacks are known as '' strategic weapons.'' Nuclear weapons for use on a battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

field in military situations are called ''tactical weapons

A tactical nuclear weapon (TNW) or non-strategic nuclear weapon (NSNW) is a nuclear weapon that is designed to be used on a battlefield in military situations, mostly with friendly forces in proximity and perhaps even on contested friendly territo ...

.''

Critics of nuclear war strategy often suggest that a nuclear war between two nations would result in mutual annihilation. From this point of view, the significance of nuclear weapons is to deter war because any nuclear war would escalate out of mutual distrust and fear, resulting in mutually assured destruction. This threat of national, if not global, destruction has been a strong motivation for anti-nuclear weapons activism.

Critics from the peace movement and within the military establishment have questioned the usefulness of such weapons in the current military climate. According to an advisory opinion

An advisory opinion is an opinion issued by a court or a commission like an election commission that does not have the effect of adjudicating a specific legal case, but merely advises on the constitutionality or interpretation of a law. Some cou ...

issued by the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

in 1996, the use of (or threat of use of) such weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, but the court did not reach an opinion as to whether or not the threat or use would be lawful in specific extreme circumstances such as if the survival of the state were at stake.

Another deterrence

Deterrence may refer to:

* Deterrence theory, a theory of war, especially regarding nuclear weapons

* Deterrence (penology), a theory of justice

* Deterrence (psychology), a psychological theory

* ''Deterrence'' (film), a 1999 drama starring Kev ...

position is that nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

can be desirable. In this case, it is argued that, unlike conventional weapons, nuclear weapons deter all-out war between states, and they succeeded in doing this during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

between the U.S. and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Gen. Pierre Marie Gallois

Pierre Marie Gallois (29 June 1911 – 24 August 2010) was a French air force brigadier general and Geopolitics, geopolitician. He was instrumental in the constitution of the France and nuclear weapons, French nuclear arsenal, and is conside ...

of France, an adviser to Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

, argued in books like ''The Balance of Terror: Strategy for the Nuclear Age'' (1961) that mere possession of a nuclear arsenal was enough to ensure deterrence, and thus concluded that the spread of nuclear weapons could increase international stability. Some prominent neo-realist scholars, such as Kenneth Waltz

Kenneth Neal Waltz (; June 8, 1924 – May 12, 2013) was an American political scientist who was a member of the faculty at both the University of California, Berkeley and Columbia University and one of the most prominent scholars in the field of ...

and John Mearsheimer

John Joseph Mearsheimer (; born December 14, 1947) is an American political scientist and international relations scholar, who belongs to the realist school of thought. He is the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor at the Univers ...

, have argued, along the lines of Gallois, that some forms of nuclear proliferation would decrease the likelihood of total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-combata ...

, especially in troubled regions of the world where there exists a single nuclear-weapon state. Aside from the public opinion that opposes proliferation in any form, there are two schools of thought on the matter: those, like Mearsheimer, who favored selective proliferation, and Waltz, who was somewhat more non- interventionist.Kenneth Waltz"The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Better,"

''Adelphi Papers'', no. 171 (London: International Institute for Strategic Studies, 1981). Interest in proliferation and the stability-instability paradox that it generates continues to this day, with ongoing debate about indigenous Japanese and

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

n nuclear deterrent against North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

.

The threat of potentially suicidal terrorists possessing nuclear weapons (a form of nuclear terrorism) complicates the decision process. The prospect of mutually assured destruction might not deter an enemy who expects to die in the confrontation. Further, if the initial act is from a stateless terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

instead of a sovereign nation, there might not be a nation or specific target to retaliate against. It has been argued, especially after the September 11, 2001, attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerc ...

, that this complication calls for a new nuclear strategy, one that is distinct from that which gave relative stability during the Cold War.See, for example: Feldman, Noah.Islam, Terror and the Second Nuclear Age

," ''New York Times Magazine'' (October 29, 2006). Since 1996, the United States has had a policy of allowing the targeting of its nuclear weapons at terrorists armed with

weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natura ...

.

Robert Gallucci

Robert L. Gallucci (born February 11, 1946) is an American academic and diplomat, who formerly worked as president of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. He previously served as dean of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service ...

argues that although traditional deterrence is not an effective approach toward terrorist groups bent on causing a nuclear catastrophe, Gallucci believes that "the United States should instead consider a policy of expanded deterrence, which focuses not solely on the would-be nuclear terrorists but on those states that may deliberately transfer or inadvertently leak nuclear weapons and materials to them. By threatening retaliation against those states, the United States may be able to deter that which it cannot physically prevent.".

Graham Allison

Graham Tillett Allison Jr. (born March 23, 1940) is an American political scientist and the Douglas Dillon Professor of Government at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He is renowned for his contribution in the late ...

makes a similar case, arguing that the key to expanded deterrence is coming up with ways of tracing nuclear material to the country that forged the fissile material. "After a nuclear bomb detonates, nuclear forensics Nuclear forensics is the investigation of nuclear materials to find evidence for the source, the trafficking, and the enrichment of the material. The material can be recovered from various sources including dust from the vicinity of a nuclear facili ...

cops would collect debris samples and send them to a laboratory for radiological analysis. By identifying unique attributes of the fissile material, including its impurities and contaminants, one could trace the path back to its origin." The process is analogous to identifying a criminal by fingerprints. "The goal would be twofold: first, to deter leaders of nuclear states from selling weapons to terrorists by holding them accountable for any use of their weapons; second, to give leaders every incentive to tightly secure their nuclear weapons and materials."

According to the Pentagon's June 2019 "Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations

The Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations was a U.S. Department of Defense document publicly discovered in 2005 on the circumstances under which commanders of U.S. forces could request the use of nuclear weapons. The document was a draft being revi ...

" of the Joint Chiefs of Staffs website Publication, "Integration of nuclear weapons employment with conventional and special operations forces is essential to the success of any mission or operation."

Governance, control, and law

head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a gro ...

or head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

. Despite controls and regulations governing nuclear weapons, there is an inherent danger of "accidents, mistakes, false alarms, blackmail, theft, and sabotage".

In the late 1940s, lack of mutual trust prevented the United States and the Soviet Union from making progress on arms control agreements. The Russell–Einstein Manifesto was issued in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

on July 9, 1955, by Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

in the midst of the Cold War. It highlighted the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and called for world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflict. The signatories included eleven pre-eminent intellectuals and scientists, including Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, who signed it just days before his death on April 18, 1955. A few days after the release, philanthropist Cyrus S. Eaton

Cyrus Stephen Eaton Sr. (December 27, 1883 – May 9, 1979) was a Canadian-American investment banker, businessman and philanthropist, with a career that spanned seventy years.

For decades Eaton was one of the most powerful financiers in the ...

offered to sponsor a conference—called for in the manifesto—in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Eaton's birthplace. This conference was to be the first of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, held in July 1957.

By the 1960s, steps were taken to limit both the proliferation of nuclear weapons to other countries and the environmental effects of nuclear testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detonations are affected by ...

. The Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (1963) restricted all nuclear testing to underground nuclear testing, to prevent contamination from nuclear fallout, whereas the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation ...

(1968) attempted to place restrictions on the types of activities signatories could participate in, with the goal of allowing the transference of non-military nuclear technology

Nuclear technology is technology that involves the nuclear reactions of atomic nuclei. Among the notable nuclear technologies are nuclear reactors, nuclear medicine and nuclear weapons. It is also used, among other things, in smoke detectors an ...

to member countries without fear of proliferation.

International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 1957 ...

(IAEA) was established under the mandate of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...