Northern Virginia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Northern Virginia, locally referred to as NOVA or NoVA, comprises several counties and

The region is often spelled "northern Virginia", although according to the

The region is often spelled "northern Virginia", although according to the

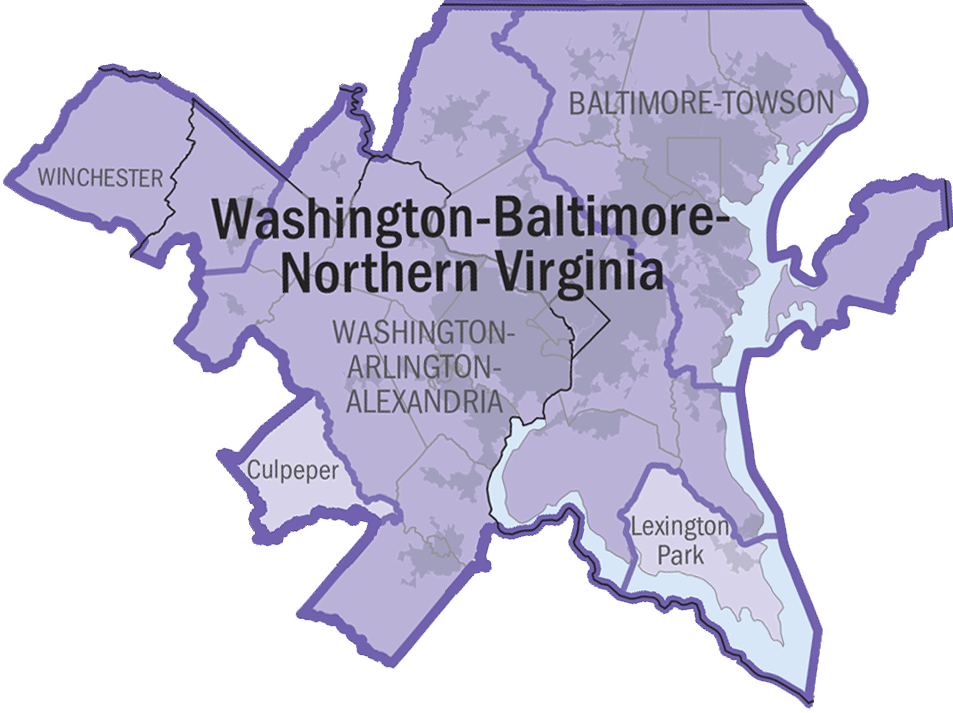

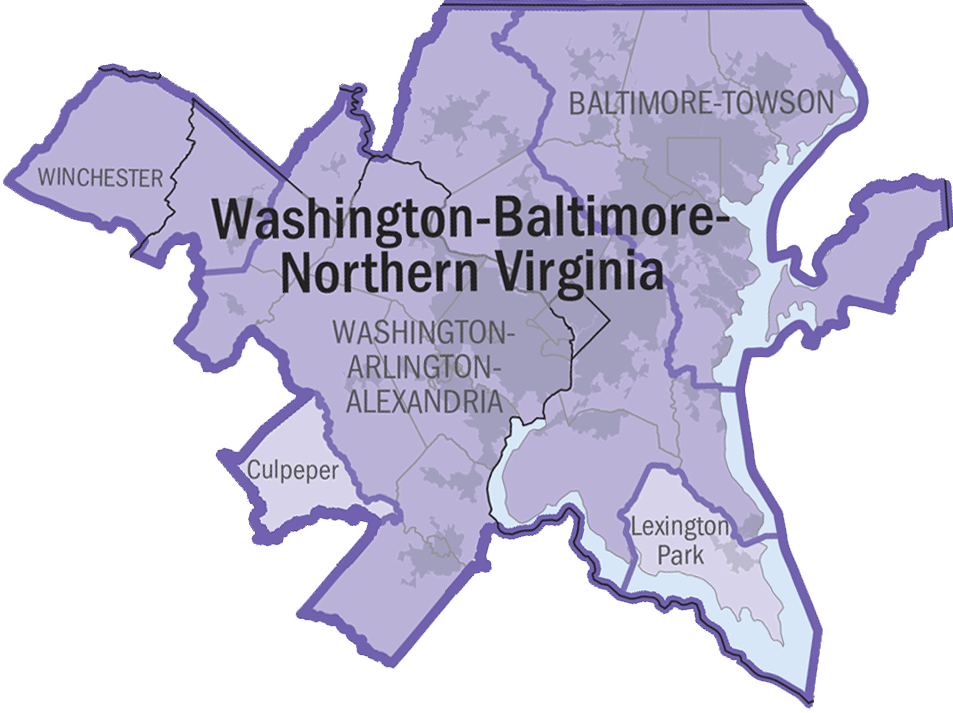

The most common definition of Northern Virginia includes the independent cities and counties on the Virginia side of the Washington-Baltimore-Arlington, DC-MD-VA-WV-PA Combined Statistical Area as defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget within the

The most common definition of Northern Virginia includes the independent cities and counties on the Virginia side of the Washington-Baltimore-Arlington, DC-MD-VA-WV-PA Combined Statistical Area as defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget within the

Historically, in the British

Historically, in the British

Following the American Revolutionary War, when the

Following the American Revolutionary War, when the  With barely separating the two capital cities, Northern Virginia found itself in the center of much of the conflict. The area was the site of many battles and saw great destruction and bloodshed. The

With barely separating the two capital cities, Northern Virginia found itself in the center of much of the conflict. The area was the site of many battles and saw great destruction and bloodshed. The

The Department of Defense's increasing reliance on information technology companies during the Cold War started the modern Northern Virginia economy and spurred urban development throughout the region. After the Cold War, prosperity continued to come as the region positioned itself as the "

The Department of Defense's increasing reliance on information technology companies during the Cold War started the modern Northern Virginia economy and spurred urban development throughout the region. After the Cold War, prosperity continued to come as the region positioned itself as the "

In 1988, the Tysons Galleria mall opened across Virginia Route 123 from Tysons Corner Center with high-end department stores Neiman Marcus and

In 1988, the Tysons Galleria mall opened across Virginia Route 123 from Tysons Corner Center with high-end department stores Neiman Marcus and

Crime in Virginia 2021

Report published by the Department of State Police, Northern Virginia had homicide rates below the State average: A 2009 report by the Northern Virginia Regional Gang Task Force suggests that anti-gang measures and crackdowns on illegal immigrants by local jurisdictions are driving gang members out of Northern Virginia and into more immigrant-friendly locales in Maryland, Washington, D.C., and the rest of Virginia. The violent crime rate in Northern Virginia fell 17 percent from 2003 to 2008. Fairfax County has the lowest crime rate in the Washington metropolitan area, and the lowest crime rate amongst the 50 largest jurisdictions of the United States. While the region has extremely low violent crime rates, it is an emerging hub for teen sex trafficking, with regional gangs finding it more profitable than selling drugs or weapons.

Former Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell described Northern Virginia as "the economic engine of the state" during a January 2010 Northern Virginia Technology Council address.

the Northern Virginia office submarkets contain of office space, 33 percent more than those in Washington, D.C., and 55 percent more than those in its Maryland suburbs. of office space is under construction in Northern Virginia. 60 percent of the construction is occurring in the Dulles Corridor submarket.

In September 2008 the unemployment rate in Northern Virginia was 3.2 percent, about half the national average, and the lowest of any metropolitan area if ranked. While the U.S. as a whole had negative job growth from September 2007 to September 2008, Northern Virginia gained 12,800 jobs, representing half of Virginia's new jobs. As of July 2010 the unemployment rate of the region 5.2 percent, down from 5.3 percent in the previous month. In the mid-2000s Fairfax County was one of few places in the nation that attracted more creative-class workers than it created.

Former Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell described Northern Virginia as "the economic engine of the state" during a January 2010 Northern Virginia Technology Council address.

the Northern Virginia office submarkets contain of office space, 33 percent more than those in Washington, D.C., and 55 percent more than those in its Maryland suburbs. of office space is under construction in Northern Virginia. 60 percent of the construction is occurring in the Dulles Corridor submarket.

In September 2008 the unemployment rate in Northern Virginia was 3.2 percent, about half the national average, and the lowest of any metropolitan area if ranked. While the U.S. as a whole had negative job growth from September 2007 to September 2008, Northern Virginia gained 12,800 jobs, representing half of Virginia's new jobs. As of July 2010 the unemployment rate of the region 5.2 percent, down from 5.3 percent in the previous month. In the mid-2000s Fairfax County was one of few places in the nation that attracted more creative-class workers than it created.

Northern Virginia is the busiest

Northern Virginia is the busiest

The federal government is a major employer in Northern Virginia, which is home to numerous government agencies; these include the

The federal government is a major employer in Northern Virginia, which is home to numerous government agencies; these include the

Additionally, Verisign, the manager of the

Additionally, Verisign, the manager of the

The region's large shopping malls, such as Potomac Mills and Tysons Corner Center, attract many visitors, as do the region's Civil War battlefields, which include the sites of both the First and Second Battle of Bull Run in Manassas and the

The region's large shopping malls, such as Potomac Mills and Tysons Corner Center, attract many visitors, as do the region's Civil War battlefields, which include the sites of both the First and Second Battle of Bull Run in Manassas and the

The period following World War II saw substantial growth of Virginia's suburban areas, notably in the regions of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and

The period following World War II saw substantial growth of Virginia's suburban areas, notably in the regions of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and

In the 21st century, Northern Virginia is becoming increasingly known for favoring candidates of the

In the 21st century, Northern Virginia is becoming increasingly known for favoring candidates of the

Tysons Corner Center ("Tysons I") is one of the largest malls in the country and is a hub for shopping in the area. Tysons Galleria ("Tysons II"), its counterpart across Route 123, carries more high-end stores.

Tysons Corner Center ("Tysons I") is one of the largest malls in the country and is a hub for shopping in the area. Tysons Galleria ("Tysons II"), its counterpart across Route 123, carries more high-end stores.

The area has two major airports, Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and Washington Dulles International Airport. While flights from the older National Airport (a hub for

The area has two major airports, Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport and Washington Dulles International Airport. While flights from the older National Airport (a hub for

Fairfax County's public school system includes the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, an award-winning

Fairfax County's public school system includes the Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, an award-winning

D.C. Dotcom

''

Where is Northern Virginia?

''Bacon's Rebellion'' (2003)

''

The Federal Job Machine

''

Will Northern Virginia Become the 51st State?

'' The Washingtonian'' (2008)

The Corporate Intelligence Community: A Photo Exclusive

'' Tim Shorrock'' (2010)

''

Northern Virginia Regional Commission

Northern Virginia Transportation Authority

{{coord, display=title, 38.837392, -77.4473128 Northern Virginia, Regions of Virginia Washington metropolitan area Proposed states and territories of the United States

independent cities

An independent city or independent town is a city or town that does not form part of another general-purpose local government entity (such as a province).

Historical precursors

In the Holy Roman Empire, and to a degree in its successor states ...

in the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with " republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from th ...

of Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

. It is a widespread region radiating westward and southward from Washington, D.C. With 3,197,076 people according to the 2020 Census (37.04 percent of Virginia's total population), it is the most populous region of Virginia and the Washington metropolitan area.

Communities in the region form the Virginia portion of the Washington metropolitan area and the larger Washington–Baltimore metropolitan area. Northern Virginia has a significantly larger job base than either Washington or the Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

portion of its suburbs, and is the highest-income region of Virginia, having several of the highest-income counties in the nation, including 3 of the richest 10 counties by median household income according to the 2019 American Community Survey.

Northern Virginia's transportation infrastructure includes major airports Ronald Reagan Washington National and Washington Dulles International, several lines of the Washington Metro

The Washington Metro (or simply Metro), formally the Metrorail,Google Books search/preview

subway system, the Virginia Railway Express suburban commuter rail system, transit bus

Transit may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Transit'' (1979 film), a 1979 Israeli film

* ''Transit'' (2005 film), a film produced by MTV and Staying-Alive about four people in countries in the world

* ''Transit'' (2006 film), a 2006 ...

services, bicycle sharing and bicycle lanes and trails, and an extensive network of Interstate highway

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. T ...

s and expressways.

Notable features of the region include the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metonym ...

, headquarters of the United States Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD or DOD) is an executive branch department of the federal government charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government directly related to national secur ...

, the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

, the United States Patent and Trademark Office, and the many companies which serve them and the rest of the U.S. federal government. The area's tourist attractions include various memorials, museums, and Colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 a ...

and Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

–era sites including Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, Manassas National Battlefield Park

Manassas National Battlefield Park is a unit of the National Park Service located in Prince William County, Virginia, north of Manassas that preserves the site of two major American Civil War battles: the First Battle of Bull Run, also called t ...

, Mount Vernon Estate

Mount Vernon is an American landmark and former plantation of Founding Father, commander of the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War, and the first president of the United States George Washington and his wife, Martha. The estate is on t ...

, the National Museum of the Marine Corps, the Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum, United States Marine Corps War Memorial. Other attractions include portions of the Appalachian Trail

The Appalachian Trail (also called the A.T.), is a hiking trail in the Eastern United States, extending almost between Springer Mountain in Georgia and Mount Katahdin in Maine, and passing through 14 states.Gailey, Chris (2006)"Appalachian ...

, Great Falls Park, Old Town Alexandria

Old Town Alexandria is one of the original settlements of the city of Alexandria, Virginia and is located just minutes from Washington, D.C. Old Town is situated in the eastern and southeastern area of Alexandria along the Potomac River. Old T ...

, Prince William Forest Park, and portions of Shenandoah National Park.

Etymology

The region is often spelled "northern Virginia", although according to the

The region is often spelled "northern Virginia", although according to the USGS

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

Correspondence Handbook the 'n' in Northern Virginia should be capitalized since it is a place name rather than a direction or general area; e.g. Eastern United States vs. western Massachusetts

Western Massachusetts, known colloquially as “Western Mass,” is a region in Massachusetts, one of the six U.S. states that make up the New England region of the United States. Western Massachusetts has diverse topography; 22 colleges and u ...

.

The name "Northern Virginia" does not seem to have been used in the early history of the area. According to Johnston, some early documents and land grants refer to the "Northern Neck of Virginia" (see Northern Neck Proprietary), and they describe an area which began on the east at the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

and includes a territory that extended west, including all the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock

Rappahannock may refer to:

Education

*Rappahannock Academy & Military Institute (1813–1873), a school in Caroline County, Virginia

*Rappahannock Community College, a two-year college located in Glenns and Warsaw, Virginia

*Rappahannock County ...

rivers, with a western boundary called the Fairfax line. The Fairfax line, surveyed in 1746, ran from the first spring of the Potomac (still marked today by the Fairfax Stone) to the first spring of the Rappahannock, at the head of the Conway River. The Northern Neck was composed of , and was larger in area than five of the modern U.S. states.

Early development of the northern portion of Virginia was in the easternmost area of that early land grant, which encompasses the modern counties of Lancaster, Northumberland

Northumberland () is a ceremonial counties of England, county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Ab ...

, Richmond, and Westmoreland. At some point, these eastern counties came to be called separately simply "the Northern Neck", and, for the remaining area west of them, the term was no longer used. (By some definitions, King George County is also included in the Northern Neck, which is now considered a separate region from Northern Virginia.The Official Guide of Virginia's Northern Neck (2007), Northern Neck Tourism Council)

One of the most prominent early mentions of "Northern Virginia" (sans the word ''Neck'') as a title was the naming of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most o ...

during the American Civil War (1861–1865).

Definition

The most common definition of Northern Virginia includes the independent cities and counties on the Virginia side of the Washington-Baltimore-Arlington, DC-MD-VA-WV-PA Combined Statistical Area as defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget within the

The most common definition of Northern Virginia includes the independent cities and counties on the Virginia side of the Washington-Baltimore-Arlington, DC-MD-VA-WV-PA Combined Statistical Area as defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget within the Executive Office of the President of the United States

The Executive Office of the President (EOP) comprises the offices and agencies that support the work of the president at the center of the executive branch of the United States federal government. The EOP consists of several offices and age ...

.

Most narrowly defined, Northern Virginia consists of the counties of Arlington, Fairfax

Fairfax may refer to:

Places United States

* Fairfax, California

* Fairfax Avenue, a major thoroughfare in Los Angeles, California

* Fairfax District, Los Angeles, California, centered on Fairfax Avenue

* Fairfax, Georgia

* Fairfax, Indiana

* Fa ...

, Loudoun, Prince William, and Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in ...

as well as the independent cities of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, Fairfax

Fairfax may refer to:

Places United States

* Fairfax, California

* Fairfax Avenue, a major thoroughfare in Los Angeles, California

* Fairfax District, Los Angeles, California, centered on Fairfax Avenue

* Fairfax, Georgia

* Fairfax, Indiana

* Fa ...

, Falls Church, Fredericksburg, Manassas, and Manassas Park.

Businesses, governments and non-profit agencies may define the area considered "Northern Virginia" differently for various purposes. Many communities beyond the areas closest to Washington, DC also have close economic ties, as well as important functional ones, to Northern Virginia, especially regarding roads, railroads, airports, and other transportation.

History

Colonial period

Historically, in the British

Historically, in the British Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colonial empire, English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertG ...

first permanently settled at Jamestown in 1607, the area now generally regarded as "Northern Virginia" was within a larger area defined by a land grant from King Charles II of England on September 18, 1649, while the monarch was in exile in France during the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians ("Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of Kingdom of England, England's governanc ...

. Eight of his loyal supporters were named, among them Thomas Culpeper.

On February 25, 1673, a new charter was given to Thomas Lord Culpeper and Henry Earl of Arlington. Lord Culpeper was named the Royal Governor of Virginia from 1677 to 1683. Culpeper County was later named for him when it was formed in 1749; however, history does not seem to record him as one of the better of Virginia's colonial governors. Although he became governor of Virginia in July 1677, he did not come to Virginia until 1679, and even then seemed more interested in maintaining his land in the "Northern Neck of Virginia" than governing. He soon returned to England. In 1682 rioting in the colony forced him to return, but by the time he arrived, the riots were already quelled. After apparently misappropriating £9,500 from the treasury of the colony, he returned to England and the King was forced to dismiss him. During this tumultuous time, Culpeper's erratic behavior meant that he had to rely increasingly on his cousin and Virginia agent, Col. Nicholas Spencer. Spencer succeeded Culpeper as acting Governor upon Lord Culpeper's departure from the colony. For many years, Lord Culpeper's descendants allowed men in Virginia (primarily Robert "King" Carter) to manage the properties.

Legal claim to the land was finally established by Lord Culpeper's grandson, Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron, who became well known in the colony as "Lord Fairfax", in a survey authorized by Governor William Gooch in 1736. The lands of Lord Fairfax (and Northern Virginia) were defined as that between the Rappahannock

Rappahannock may refer to:

Education

*Rappahannock Academy & Military Institute (1813–1873), a school in Caroline County, Virginia

*Rappahannock Community College, a two-year college located in Glenns and Warsaw, Virginia

*Rappahannock County ...

and Potomac rivers, and were officially called the "Northern Neck". In 1746 a back line was surveyed and established between the headwaters of the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers, defining the west end of the grants. According to documents held by the Handley Regional Library of the Winchester– Frederick County Historical Society, the grants contained . They included the 22 modern counties of Northumberland, Lancaster, Westmoreland, Stafford, King George, Prince William, Fairfax, Loudoun, Fauquier, Rappahannock, Culpeper, Madison, Clarke, Warren, Page, Shenandoah, and Frederick counties in Virginia, and Hardy, Hampshire, Morgan, Berkeley, and Jefferson counties in West Virginia.

Lord Fairfax was a lifelong bachelor, and became one of the more well-known persons of the late colonial era. In 1742 the new county formed from Prince William County was named Fairfax County in his honor, one of numerous place names in Northern Virginia and West Virginia's Eastern Panhandle which were named after him. Lord Fairfax established his residence first at his brother's home at "Belvoir" (now on the grounds of Fort Belvoir

Fort Belvoir is a United States Army installation and a census-designated place (CDP) in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. It was developed on the site of the former Belvoir plantation, seat of the prominent Fairfax family for whom Fa ...

in Fairfax County).

Not long thereafter, he built a hunting lodge near the Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a Physiographic regions of the world, physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States, and extends 550 miles southwest from southern Pennsy ...

he named "Greenway Court", which was located near White Post in Clarke County, and moved there. Around 1748 Lord Fairfax met a youth of 16 named George Washington, and, impressed with his energy and talents, employed him to survey his lands lying west of the Blue Ridge.

Lord Fairfax stayed neutral during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

. Just a few weeks after the surrender of British troops under General Cornwallis at Yorktown, he died at his home at Greenway Court on December 9, 1781, at the age of 90. He was entombed on the east side of Christ Church in Winchester. While his plans for a large house at Greenway Court never materialized, and his stone lodge is now gone, a small limestone structure he had built still exists on the site.

Statehood, Civil War

thirteen colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

formed the United States of America, war hero and Virginian George Washington was the choice to become its first president. Washington had been a surveyor and developer of canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface fl ...

s for transportation earlier in the 18th century. He was also a great proponent of the bustling port city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, which was located on the Potomac River below the fall line, not far from his plantation at Mount Vernon in Fairfax County.

With his guidance, a new federal city (now known as the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan ...

) was laid out straddling the Potomac River upon a square of territory which was ceded to the federal government by the new states of Maryland and Virginia. Alexandria was located at the eastern edge south of the river. On the outskirts on the northern side of the river, another port city, Georgetown, was located.

However, as the federal city grew, land in the portion contributed by Maryland proved best suited and adequate for early development, and the impracticality of being on both sides of the Potomac River became clearer. Not really part of the functioning federal city, many citizens of Alexandria were frustrated by the laws of the District government and lack of voting input. Slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

also arose as an issue. To mitigate these issues, and as part of a "deal" regarding abolishment of slave trading in the District, in 1846, the U.S. Congress passed a bill retroceding to Virginia the area south of the Potomac River, which was known as Alexandria County. That area now forms all of Arlington County (which was renamed from Alexandria County in 1922) and a portion of the independent city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

.

Slavery, states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and ...

, and economic issues increasingly divided the northern and southern states during the first half of the 19th century, eventually leading to the American Civil War from 1861 to 1865. Although Maryland was a slave state, it remained with the Union, while Virginia seceded and joined the newly formed Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confede ...

, with its new capital established at Richmond.

The Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point ...

has never issued a firm opinion on whether the retrocession of the Virginia portion of the District of Columbia was constitutional. In the 1875 case of ''Phillips v. Payne

''Phillips v. Payne'', 92 U.S. 105 (1875), was a United States Supreme Court case that ruled that since 1847, pursuant to the act of Congress of the preceding year, the State of Virginia has been in de facto possession of the County of Alexandria, ...

'', the Supreme Court held that Virginia had ''de facto'' jurisdiction over the area returned by Congress in 1847, and dismissed the tax case brought by the plaintiff. The court, however, did not rule on the core constitutional matter of the retrocession. Writing the majority opinion, Justice Noah Swayne stated only that:

The plaintiff in error is estopped from raising the point which he seeks to have decided. He cannot, under the circumstances, vicariously raise a question, nor force upon the parties to the compact an issue which neither of them desires to make.

Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most o ...

was the primary army for the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confede ...

in the east. Owing to the region's proximity to Washington, D.C., and the Potomac River, the armies of both sides frequently occupied and traversed Northern Virginia. As a result, several battles were fought in the area.

In addition, Northern Virginia was the operating area of the famed Confederate partisan, John Singleton Mosby

John Singleton Mosby (December 6, 1833 – May 30, 1916), also known by his nickname "Gray Ghost", was a Confederate army cavalry battalion commander in the American Civil War. His command, the 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, known as Mosb ...

, and several small skirmishes were fought throughout the region between his Rangers and Federal forces occupying Northern Virginia.

Well after the war, the conflict remained popular among the region's residents, and many area schools, roads, and parks were named for Confederate generals and statesmen, for example Jefferson Davis Highway and Washington-Lee High School.

Virginia split during the American Civil War, as was foreshadowed by the April 17, 1861, Virginia Secession Convention. Fifty counties in the western, mountainous, portion of the state, who were, for the most part, against secession in 1861, would break away from the Confederacy in 1863 and enter the Union as a new state, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

. Unlike the eastern part of the state, West Virginia did not have fertile lands tilled by slaves and was geographically separated from the state government in Richmond by the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. The ...

. During this process, a provisional government of Virginia was headquartered in Alexandria, which was under Union control during the war. Notably, Arlington, Clarke, Fairfax, Frederick, Loudoun, Shenandoah, and Warren Counties voted in favor of Virginia remaining in the Union in 1861 but did not eventually break away from the state.

As a result of the formation of West Virginia, part of Lord Fairfax's colonial land grant which defined Northern Virginia was ceded in the establishment of that state in 1863. Now known as the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia, the area includes Berkeley County and Jefferson County, West Virginia

Jefferson County is located in the Shenandoah Valley in the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. It is the easternmost county of the U.S. state of West Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 57,701. Its county seat is Charles T ...

.

20th century and beyond

The Department of Defense's increasing reliance on information technology companies during the Cold War started the modern Northern Virginia economy and spurred urban development throughout the region. After the Cold War, prosperity continued to come as the region positioned itself as the "

The Department of Defense's increasing reliance on information technology companies during the Cold War started the modern Northern Virginia economy and spurred urban development throughout the region. After the Cold War, prosperity continued to come as the region positioned itself as the "Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is a region in Northern California that serves as a global center for high technology and innovation. Located in the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area, it corresponds roughly to the geographical areas San Mateo Count ...

" of the Eastern United States. The Internet was first commercialized in Northern Virginia, having been home to the first Internet service provider

An Internet service provider (ISP) is an organization that provides services for accessing, using, or participating in the Internet. ISPs can be organized in various forms, such as commercial, community-owned, non-profit, or otherwise privatel ...

s.

The first major interconnection point of the Internet, MAE-East, was established in the 1990s at Ashburn after Virginia-area network provider operators thought to connect their networks together while drinking beer. This infrastructure legacy is ongoing, as data center operators continue to expand near these facilities.

History was made in early 2001 when local Internet company America Online

AOL (stylized as Aol., formerly a company known as AOL Inc. and originally known as America Online) is an American web portal and online service provider based in New York City. It is a brand marketed by the current incarnation of Yahoo (2017� ...

bought Time Warner, the world's largest traditional media company, near the end of the dot-com bubble days. After the bubble burst, Northern Virginia office vacancy rates went from 2 percent in 2000 to 20 percent in 2002. After 2002, vacancy rates fell below 10 percent due to increased defense spending after the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerc ...

, and the Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bord ...

and Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

wars causing the government's continued and increasing reliance on private defense contractors.

Regional organizations

Northern Virginia Regional Commission

Northern Virginia is an area within the Commonwealth of Virginia and is part of the Washington DC metropolitan area. The Northern Virginia Regional Commission(NVRC) is a regional government that represents a regional council of thirteen member Northern Virginia local governments. These local governments include the counties of Arlington,Fairfax

Fairfax may refer to:

Places United States

* Fairfax, California

* Fairfax Avenue, a major thoroughfare in Los Angeles, California

* Fairfax District, Los Angeles, California, centered on Fairfax Avenue

* Fairfax, Georgia

* Fairfax, Indiana

* Fa ...

, Loudoun, and Prince William. The local governments include the incorporated cities of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, Fairfax

Fairfax may refer to:

Places United States

* Fairfax, California

* Fairfax Avenue, a major thoroughfare in Los Angeles, California

* Fairfax District, Los Angeles, California, centered on Fairfax Avenue

* Fairfax, Georgia

* Fairfax, Indiana

* Fa ...

, Falls Church, Manassas, and Manassas Park. The local governments also include the incorporated towns of Dumfries, Herndon, Leesburg, and Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. NVRC's chief roles and functions have focused on providing information, performing professional and technical services for its members, and serving as a mechanism for regional coordination regarding the environment, transportation, affordable housing, community planning, military, and human services. Programs and projects address a wide array of local government interests.

According to Virginia's Regional Cooperation Act, NVRC is a political subdivision (a government agency) within the Commonwealth. The region is technically referred to as Virginia's planning district #8. The commission was established pursuant to Articles 1 and 2, Chapter 34, of the Acts of the Virginia General Assembly of 1968, subsequently revised and re-enacted as the Regional Cooperation Act under Title 15.2, Chapter 42 of the Code of Virginia, hereinafter called the "Act", and by resolutions of the governing bodies of its constituent member governmental subdivision. Any incorporated county, city or town in Northern Virginia may become a member of NVRC, provided the jurisdiction has a population of more than 3,500 and adopts and executes NVRC's Charter Agreement.

Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments

Northern Virginia constitutes a considerable portion of the population and number of jurisdictions that comprise the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments (MWCOG). Founded in 1957, MWCOG is a regional organization of 22 Washington-area local governments, as well as area members of theMaryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; ...

and Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

state legislatures, the U.S. Senate, and the U.S. House of Representatives. MWCOG provides a forum for discussion and the development of regional responses to issues regarding the environment, transportation, public safety, homeland security, affordable housing, community planning, and economic development.

The National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board, a component of MWCOG, is the federally designated metropolitan planning organization A metropolitan planning organization (MPO) is a federally mandated and federally funded transportation policy-making organization in the United States that is made up of representatives from local government and governmental transportation authorit ...

for the metropolitan Washington area, including Northern Virginia.

Demographics

there were 3,197,076 people in Northern Virginia; approximately 37 percent of the state's population. These population counts include all counties within Virginia that are part of the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area or the Washington-Baltimore-Arlington, DC-MD-VA-WV-PA Combined Statistical Area as defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budgethttps://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/metro-micro/about/omb-bulletins.html , OMB Bulletin No. 18-04, Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas within theExecutive Office of the President of the United States

The Executive Office of the President (EOP) comprises the offices and agencies that support the work of the president at the center of the executive branch of the United States federal government. The EOP consists of several offices and age ...

.

Of the 3,159,639 people in Northern Virginia in the 2019 estimates, 2,776,960 lived in "central" counties, or those counties and equivalent entities as delineated by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget as forming part of the urban core of the Washington Metropolitan Statistical Area. These counties include Arlington, Fairfax

Fairfax may refer to:

Places United States

* Fairfax, California

* Fairfax Avenue, a major thoroughfare in Los Angeles, California

* Fairfax District, Los Angeles, California, centered on Fairfax Avenue

* Fairfax, Georgia

* Fairfax, Indiana

* Fa ...

, Fauquier, Loudoun, Prince William, Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in ...

and the independent cities

An independent city or independent town is a city or town that does not form part of another general-purpose local government entity (such as a province).

Historical precursors

In the Holy Roman Empire, and to a degree in its successor states ...

of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

, Fairfax

Fairfax may refer to:

Places United States

* Fairfax, California

* Fairfax Avenue, a major thoroughfare in Los Angeles, California

* Fairfax District, Los Angeles, California, centered on Fairfax Avenue

* Fairfax, Georgia

* Fairfax, Indiana

* Fa ...

, Falls Church, Manassas, Manassas Park and Fredericksburg

An additional 390,679 people lived in counties of the Washington Metropolitan Statistical Area or the Baltimore-Washington Combined Statistical Area not considered "central." These counties, largely considered exurban or undergoing suburban change, include Clarke, Culpeper, Frederick, Madison, Rappahannock

Rappahannock may refer to:

Education

*Rappahannock Academy & Military Institute (1813–1873), a school in Caroline County, Virginia

*Rappahannock Community College, a two-year college located in Glenns and Warsaw, Virginia

*Rappahannock County ...

, Spotsylvania, Warren, and the independent city of Winchester.

In addition, there are counties outside of the Washington Metropolitan Area that under more broad definitions are referred to as being part of Northern Virginia. The University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United States, with College admission ...

Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service categorizes King George County as part of Northern Virginia, though the county was removed from the Washington Metropolitan Area in 2003. King George County and Orange County also include areas, such as Lake of the Woods, where the cross-commuting interchange with the Washington Metropolitan Area is high enough to merit inclusion in the Metropolitan Area, although more far-flung parts of these counties still cause the county-wide commuter interchange to fall below the threshold for inclusion in the Washington Metropolitan Area or Washington-Baltimore Combined Statistical Area. The demographic figures above do not include population counts for these two counties.

Racial and ethnic composition

The 2020 U.S. Census resulted in the following racial and ethnic composition for Northern Virginia: Northern Virginia as a whole is 51.2% White, 17.4% Hispanic, 16.3% Asian, 14.1% Black, and 2.4% Other.Background

Northern Virginia is home to people from diverse backgrounds, with significant numbers of Korean Americans, Vietnamese Americans, Bangladeshi Americans, Chinese Americans, Filipino Americans, Russian Americans,Arab Americans

Arab Americans ( ar, عَرَبٌ أَمْرِيكِا or ) are Americans of Arab ancestry. Arab Americans trace ancestry to any of the various waves of immigrants of the countries comprising the Arab World.

According to the Arab American Inst ...

, Palestinian Americans, Uzbek Americans, Afghan Americans, Ethiopian Americans, Indian Americans, Iranian Americans, Thai Americans, and Pakistani Americans

Pakistani Americans ( ur, ) are Americans who originate from Pakistan. The term may also refer to people who also hold a dual Pakistani and U.S. citizenship. Educational attainment level and household income are much higher in the Pakistani-Am ...

. Annandale, Chantilly, and Fairfax City have very large Korean American communities. Falls Church has a large Vietnamese American community. Northern Virginia is also home to a small Tibetan American community as well.

There is a sizable Hispanic

The term ''Hispanic'' ( es, hispano) refers to people, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or Hispanidad.

The term commonly applies to countries with a cultural and historical link to Spain and to viceroyalties for ...

population, primarily consisting of Salvadorans

Salvadorans (Spanish: ''Salvadoreños''), also known as Salvadorians (alternate spelling: Salvadoreans), are citizens of El Salvador, a country in Central America. Most Salvadorans live in El Salvador, although there is also a significant Salvado ...

, Peruvians, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Bolivians, Mexicans

Mexicans ( es, mexicanos) are the citizens of the United Mexican States.

The most spoken language by Mexicans is Spanish, but some may also speak languages from 68 different Indigenous linguistic groups and other languages brought to Mexi ...

, and Colombians

Colombians ( es, Colombianos) are people identified with the country of Colombia. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Colombians, several (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the sour ...

. Arlington is the center of the largest Bolivian community in North America (mostly immigrants from Cochabamba). Many of these immigrants work in transportation-related fields, small businesses, hospitality/restaurants, vending, gardening, construction, and cleaning.

Of those born in the U.S. and living in Northern Virginia's four largest counties, their place of birth by census region is 60.5 percent from the South, 21.0 percent from the Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

, 11.5 percent from the Midwest, and 7.0 percent from the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

. 33.7 percent were born in Virginia, which is categorized as part of the Southern United States along with neighboring Maryland and Washington, D.C., by the Census Bureau.

Educational attainment

The core Northern Virginia jurisdictions of Alexandria, Arlington, Fairfax, Loudoun, and Prince William comprising a total population of 1,973,513 is highly educated, with 55.5 percent of its population 25 years or older holding a bachelor's degree or higher. This is comparable toSeattle

Seattle ( ) is a port, seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the county seat, seat of King County, Washington, King County, Washington (state), Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in bo ...

, the most educated large city in the U.S., with 53.4 percent of residents having at least a bachelor's degree. The number of graduate/professional degree holders in Arlington is relatively high at 34.3 percent, nearly quadruple the rate of the U.S. population as a whole.

Affluence

The region is known in Virginia and theWashington, D.C., area

The Washington metropolitan area, also commonly referred to as the National Capital Region, is the metropolitan area centered on Washington, D.C. The metropolitan area includes all of Washington, D.C. and parts of the states of Maryland, Vir ...

for its relative affluence. Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in ...

, one of the core counties in Northern Virginia, is one of the seven counties in America where black households make more than white households. Stafford County actually topped the list with African-Americans in Stafford County making the highest amount on the list. Of the large cities or counties in the nation that have a median household income in excess of $100,000, the top two are in Northern Virginia, and these counties have over half of the region's population. However, considering that Northern Virginia has one of the highest costs of living in the nation, the actual purchasing power of these households is considerably less than in other less "affluent" areas. According to Nielsen Claritas, Loudoun County and Arlington County have the highest concentration of 25- to 34-year-olds with incomes of $100,000+ in the nation. In 1988, the Tysons Galleria mall opened across Virginia Route 123 from Tysons Corner Center with high-end department stores Neiman Marcus and

In 1988, the Tysons Galleria mall opened across Virginia Route 123 from Tysons Corner Center with high-end department stores Neiman Marcus and Saks 5th Avenue

Saks Fifth Avenue (originally Saks & Company; colloquially Saks) is an American luxury department store chain headquartered in New York City and founded by Andrew Saks. The original store opened in the F Street shopping district of Washington, ...

, hoping to become the Washington area's upscale shopping destination. The mall had trouble with sales and attracting high-end boutiques well into the 1990s and faced competition from Fairfax Square, which opened nearby in 1990 with the largest Tiffany & Co. boutique outside of New York City.Potts, M. (1989) "The Swanky Side of Fairfax Square" ''The Washington Post'' The Galleria was able to attract high-end stores after a 1997 renovation, and in 2002 ''National Geographic'' described it as "the Rodeo Drive of the East Coast." In 2008 luxury home service Sotheby's International Realty – which had three offices in Virginia serving the rest of the state, and two in the District of Columbia serving the Washington metropolitan area – opened a new office in McLean

MacLean, also spelt Maclean and McLean, is a Gaelic surname Mac Gille Eathain, or, Mac Giolla Eóin in Irish Gaelic), Eóin being a Gaelic form of Johannes (John). The clan surname is an Anglicisation of the Scottish Gaelic "Mac Gille Eathain" ...

to sell more high-end real estate in Northern Virginia.

Crime

According to thCrime in Virginia 2021

Report published by the Department of State Police, Northern Virginia had homicide rates below the State average: A 2009 report by the Northern Virginia Regional Gang Task Force suggests that anti-gang measures and crackdowns on illegal immigrants by local jurisdictions are driving gang members out of Northern Virginia and into more immigrant-friendly locales in Maryland, Washington, D.C., and the rest of Virginia. The violent crime rate in Northern Virginia fell 17 percent from 2003 to 2008. Fairfax County has the lowest crime rate in the Washington metropolitan area, and the lowest crime rate amongst the 50 largest jurisdictions of the United States. While the region has extremely low violent crime rates, it is an emerging hub for teen sex trafficking, with regional gangs finding it more profitable than selling drugs or weapons.

Economy

Former Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell described Northern Virginia as "the economic engine of the state" during a January 2010 Northern Virginia Technology Council address.

the Northern Virginia office submarkets contain of office space, 33 percent more than those in Washington, D.C., and 55 percent more than those in its Maryland suburbs. of office space is under construction in Northern Virginia. 60 percent of the construction is occurring in the Dulles Corridor submarket.

In September 2008 the unemployment rate in Northern Virginia was 3.2 percent, about half the national average, and the lowest of any metropolitan area if ranked. While the U.S. as a whole had negative job growth from September 2007 to September 2008, Northern Virginia gained 12,800 jobs, representing half of Virginia's new jobs. As of July 2010 the unemployment rate of the region 5.2 percent, down from 5.3 percent in the previous month. In the mid-2000s Fairfax County was one of few places in the nation that attracted more creative-class workers than it created.

Former Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell described Northern Virginia as "the economic engine of the state" during a January 2010 Northern Virginia Technology Council address.

the Northern Virginia office submarkets contain of office space, 33 percent more than those in Washington, D.C., and 55 percent more than those in its Maryland suburbs. of office space is under construction in Northern Virginia. 60 percent of the construction is occurring in the Dulles Corridor submarket.

In September 2008 the unemployment rate in Northern Virginia was 3.2 percent, about half the national average, and the lowest of any metropolitan area if ranked. While the U.S. as a whole had negative job growth from September 2007 to September 2008, Northern Virginia gained 12,800 jobs, representing half of Virginia's new jobs. As of July 2010 the unemployment rate of the region 5.2 percent, down from 5.3 percent in the previous month. In the mid-2000s Fairfax County was one of few places in the nation that attracted more creative-class workers than it created.

Internet

Northern Virginia is the busiest

Northern Virginia is the busiest Internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a ''internetworking, network of networks'' that consists ...

intersection in the nation, with up to 70 percent of all Internet traffic flowing through Loudoun County data centers every day. It is the largest data center market in the world by capacity, with nearly double that of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, as well as the world's fastest growing market in 2018. Loudoun County expects to have of data center space by 2021. By 2012 Dominion Energy expects that 10 percent of all electricity it sends to Northern Virginia will be used by the region's data centers alone. Accenture estimates that 70 percent of Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud servers are located in their Northern Virginia zone. A 2015–16 estimate by Greenpeace

Greenpeace is an independent global campaigning network, founded in Canada in 1971 by Irving Stowe and Dorothy Stowe, immigrant environmental activists from the United States. Greenpeace states its goal is to "ensure the ability of the Earth ...

puts Amazon's current and upcoming power capacity in Northern Virginia at over 1 gigawatt

The watt (symbol: W) is the unit of power or radiant flux in the International System of Units (SI), equal to 1 joule per second or 1 kg⋅m2⋅s−3. It is used to quantify the rate of energy transfer. The watt is named after James Wa ...

.

Federal government

The federal government is a major employer in Northern Virginia, which is home to numerous government agencies; these include the

The federal government is a major employer in Northern Virginia, which is home to numerous government agencies; these include the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

headquarters and the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metonym ...

(headquarters of the Department of Defense), as well as Fort Myer

Fort Myer is the previous name used for a U.S. Army post next to Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, and across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. Founded during the American Civil War as Fort Cass and Fort Whippl ...

, Fort Belvoir

Fort Belvoir is a United States Army installation and a census-designated place (CDP) in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. It was developed on the site of the former Belvoir plantation, seat of the prominent Fairfax family for whom Fa ...

, Marine Corps Base Quantico, FBI Academy, DEA Academy, Naval Criminal Investigative Service

The United States Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) is the primary law enforcement agency of the U.S. Department of the Navy. Its primary function is to investigate criminal activities involving the Navy and Marine Corps, though its ...

, the United States Patent and Trademark Office, and the United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

.

Government contracting is an important part of the region's economy. Arlington alone is home to over 600 federal contractors, and has the highest weekly wages of any major jurisdiction in the Washington metropolitan area.

The following government agencies have either 10,000+ employees or a $10+ billion budget:

*Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

(CIA)

*Defense Logistics Agency

The Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) is a combat support agency in the United States Department of Defense (DoD), with more than 26,000 civilian and military personnel throughout the world. Located in 48 states and 28 countries, DLA provides su ...

* Department of Defense (DOD)

*Drug Enforcement Administration

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA; ) is a Federal law enforcement in the United States, United States federal law enforcement agency under the U.S. Department of Justice tasked with combating drug trafficking and distribution within th ...

(DEA)

*National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) is a combat support agency within the United States Department of Defense whose primary mission is collecting, analyzing, and distributing geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) in support of natio ...

(NGA)

*National Reconnaissance Office

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) is a member of the United States Intelligence Community and an agency of the United States Department of Defense which designs, builds, launches, and operates the reconnaissance satellites of the U.S. ...

(NRO)

* Transportation Security Administration (TSA)

* United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)

*United States Fish & Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is an agency within the United States Department of the Interior dedicated to the management of fish, wildlife, and natural habitats. The mission of the agency is "working with othe ...

Other well-known agencies include:

*Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is a research and development agency of the United States Department of Defense responsible for the development of emerging technologies for use by the military.

Originally known as the Adv ...

(DARPA)

* National Science Foundation (NSF)

* Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI)

Notable companies

Additionally, Verisign, the manager of the

Additionally, Verisign, the manager of the .com

The domain name .com is a top-level domain (TLD) in the Domain Name System (DNS) of the Internet. Added at the beginning of 1985, its name is derived from the word ''commercial'', indicating its original intended purpose for domains registere ...

and .net top-level domains is based in the region.

Major companies formerly headquartered in the region include AOL, Mobil

Mobil is a petroleum brand owned and operated by American oil and gas corporation ExxonMobil. The brand was formerly owned and operated by an oil and gas corporation of the same name, which itself merged with Exxon to form ExxonMobil in 1999.

...

, Nextel/Sprint

Sprint may refer to:

Aerospace

*Spring WS202 Sprint, a Canadian aircraft design

*Sprint (missile), an anti-ballistic missile

Automotive and motorcycle

*Alfa Romeo Sprint, automobile produced by Alfa Romeo between 1976 and 1989

*Chevrolet Sprint, ...

, PSINet, Sallie Mae, MCI Communications, Transurban, and UUNET.

Attractions

The region's large shopping malls, such as Potomac Mills and Tysons Corner Center, attract many visitors, as do the region's Civil War battlefields, which include the sites of both the First and Second Battle of Bull Run in Manassas and the

The region's large shopping malls, such as Potomac Mills and Tysons Corner Center, attract many visitors, as do the region's Civil War battlefields, which include the sites of both the First and Second Battle of Bull Run in Manassas and the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Bur ...

in Fredericksburg. Old Town Alexandria

Old Town Alexandria is one of the original settlements of the city of Alexandria, Virginia and is located just minutes from Washington, D.C. Old Town is situated in the eastern and southeastern area of Alexandria along the Potomac River. Old T ...

is known for its historic churches, townhouses, restaurants, gift shops, artist studios, and cruise boats. The waterfront and outdoor recreational amenities such as biking and running trails (the Washington and Old Dominion Rail Trail leads all the way from Alexandria to the foothills of the Blue Ridge; the Mount Vernon Trail and trails along various stream beds are also popular), whitewater and sea kayaking, and rock climbing areas are focused along the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands of West Virginia, Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Datas ...

, but are also found at other locations in the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area. Scenic Great Falls Park and historic Mount Vernon (which opened a new visitor center in 2006) are especially noteworthy. The Government Island park and quarry in Stafford County has views of the Potomac River, and Aquia Creek and also is where the building materials for the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest, Washington, D.C., NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. preside ...

, and United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the Legislature, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is form ...

are from. Also in Stafford County are historic places such as George Washington's boyhood home Ferry Farm

Ferry Farm, also known as the George Washington Boyhood Home Site or the Ferry Farm Site, is the farm and home where George Washington spent much of his childhood. The site is located in Stafford County, Virginia, along the northern bank of the Ra ...

, Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

headquarters and plantation Chatham Manor

Chatham Manor is a Georgian-style mansion home completed in 1771 by farmer and statesman William Fitzhugh, after about three years of construction, on the Rappahannock River in Stafford County, Virginia, opposite Fredericksburg. It was for mor ...

, and artist Gari Melchers Home & Studio.

Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

is located in the area, as is the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, an annex of the National Air and Space Museum that contains exhibits that cannot be housed at the main museum in Washington due to space constraints. Many concerts and other live shows are held at the Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, a setting which has attracted many famous productions over the years.

Politics

Background

From the mid-1880s until the mid-1960s Virginia politics were dominated by Conservative Democrats. After World War I, under the leadership of Harry Flood Byrd, who became Governor of Virginia and later aU.S. senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

, this group became known as the Byrd Organization. With a power base in a network of the constitutional officers of most of Virginia's counties, they controlled Virginia's state government. The Byrd Organization largely followed conservative and anti-debt principles espoused by Byrd, who had grown up in a rural setting during the fiscally stressed era following Reconstruction. Although a member of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

and an initial supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Senator Byrd became a bitter opponent of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

and related national policies, particularly those involving fiscal and social issues. He became Virginia's senior senator after the death of Senator Carter Glass

Carter Glass (January 4, 1858 – May 28, 1946) was an American newspaper publisher and Democratic politician from Lynchburg, Virginia. He represented Virginia in both houses of Congress and served as the United States Secretary of the Trea ...

of Lynchburg in 1946.

The period following World War II saw substantial growth of Virginia's suburban areas, notably in the regions of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and

The period following World War II saw substantial growth of Virginia's suburban areas, notably in the regions of Northern Virginia, Richmond, and Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

. The population became more diverse. People of the emerging middle class were increasingly less willing to accept the rural focus of the General Assembly, nor Byrd's extreme positions on public debt and social issues. The latter was nowhere more graphically illustrated than with Byrd's violent opposition to racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation). In addition to desegregation, integration includes goals such as leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportun ...

of the state's public schools

Public school may refer to:

*State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

*Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England and ...

. His leadership in the failed policy of Massive Resistance to racial desegregation of the public schools and efforts to circumvent related rulings of the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point ...

ultimately caused closure of some public schools in the state and alienated many middle class voters. The Byrd Organization had never been strong in Virginia's independent cities, and beginning in the 1960s, city and suburban factions increasingly supported efforts to make broad changes in Virginia. In this climate, the Republican Party of Virginia

The Republican Party of Virginia (RPV) is the Virginia chapter of the Republican Party. It is based at the Richard D. Obenshain Center in Richmond.

History

The party was established in 1854 by opponents of slavery and secession in the commonwe ...

began making inroads.

Rulings by both state and federal courts that "Massive Resistance" was unconstitutional and a move to compliance with the court orders in early 1959 by Governor J. Lindsay Almond, and the General Assembly could be described as marking the Byrd Organization's "last stand", although the remnants of the Organization continued to wield power for a few years longer.

When Senator Byrd resigned in 1965 he was replaced by his son Harry F. Byrd Jr. in the U.S. Senate. However, the heyday of the Byrd Organization was clearly in the past, ending 80 years of domination of Virginia politics by the Conservative Democrats with the election of a Republican governor, Linwood Holton, in 1969 for the first time in the 20th century, succeeding a longtime member of the Byrd Organization, Democrat Mills E. Godwin

Mills Edwin Godwin Jr. (November 19, 1914January 30, 1999) was an American politician who was the 60th and 62nd governor of Virginia for two non-consecutive terms, from 1966 to 1970 and from 1974 to 1978.

In his first term, he was a member of ...

. To the amazement of many observers, Godwin changed parties and was elected again as governor in 1973, but as a Republican.

During the last quarter of the 20th century, Virginia's Republicans gained ground against the Democrats. Republican John Warner from Northern Virginia gained one of the seats in the U.S. Senate in 1978. After longtime state senator L. Douglas Wilder

Lawrence Douglas Wilder (born January 17, 1931) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the 66th Governor of Virginia from 1990 to 1994. He was the first African American to serve as governor of a U.S. state since the Reconstruction ...

became governor in 1989, the first African American to become a governor in the United States, Republicans subsequently gained control of the Governor's mansion after the 1993 election. Republicans finally gained control of the General Assembly in the 1999 elections.

For a number of years, the recurring Republican theme was to reduce waste in state government and taxes. However, this seemed to reach a peak during the administration of Jim Gilmore

James Stuart Gilmore III (born October 6, 1949) is an American politician, diplomat, statesman, and former attorney who was the 68th Governor of Virginia from 1998 to 2002 and Chairman of the Republican National Committee in 2001.

A native V ...

, with a move to repeal an unpopular car tax accompanied by a failure to provide promised replacement funds to the counties, cities and towns. Subsequently, two Democrats were elected consecutively as governor, and control in the General Assembly shifted back to a more bipartisan balance of power. As governor, both Mark Warner

Mark Robert Warner (born December 15, 1954) is an American businessman and politician serving as the senior United States senator from Virginia, a seat he has held since 2009. A member of the Democratic Party, Warner served as the 69th govern ...

and Tim Kaine were confronted with stabilizing state economics and dealing with a deteriorating transportation funding situation partially caused by the state's failure to index state fuel taxes to inflation, with a "cents per gallon" tax rate unchanged since the administration of Democratic Governor Gerald Baliles

Gerald Lee Baliles (July 8, 1940 – October 29, 2019) was a Virginia lawyer and Democratic politician whose career spanned great social and technological changes in his native state. The 65th Governor of Virginia (from 1986 to 1990), the na ...

in 1986.

21st-century politics

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

at both the state and national level. Fairfax County supported John Kerry