Normandy Business School on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from

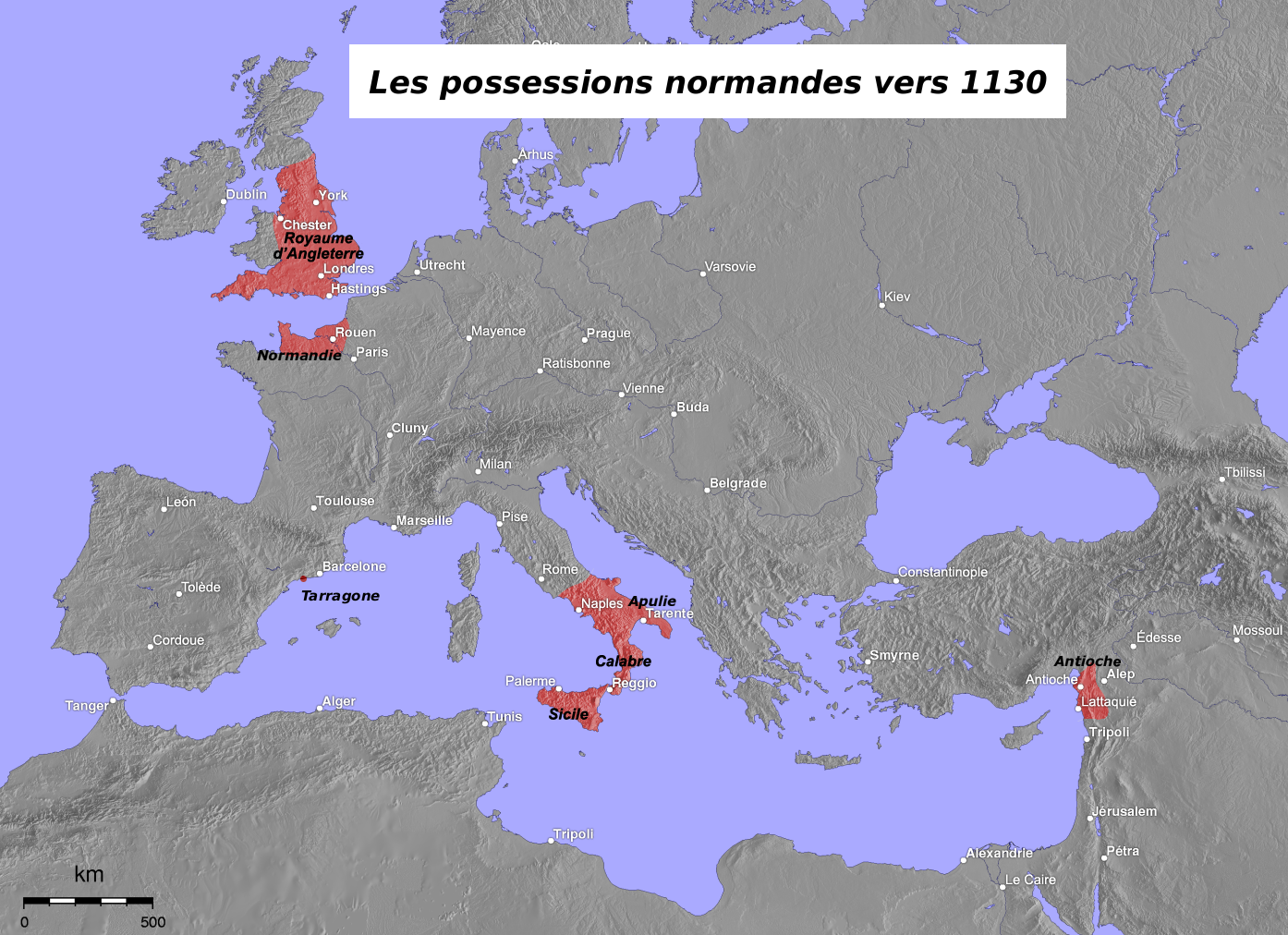

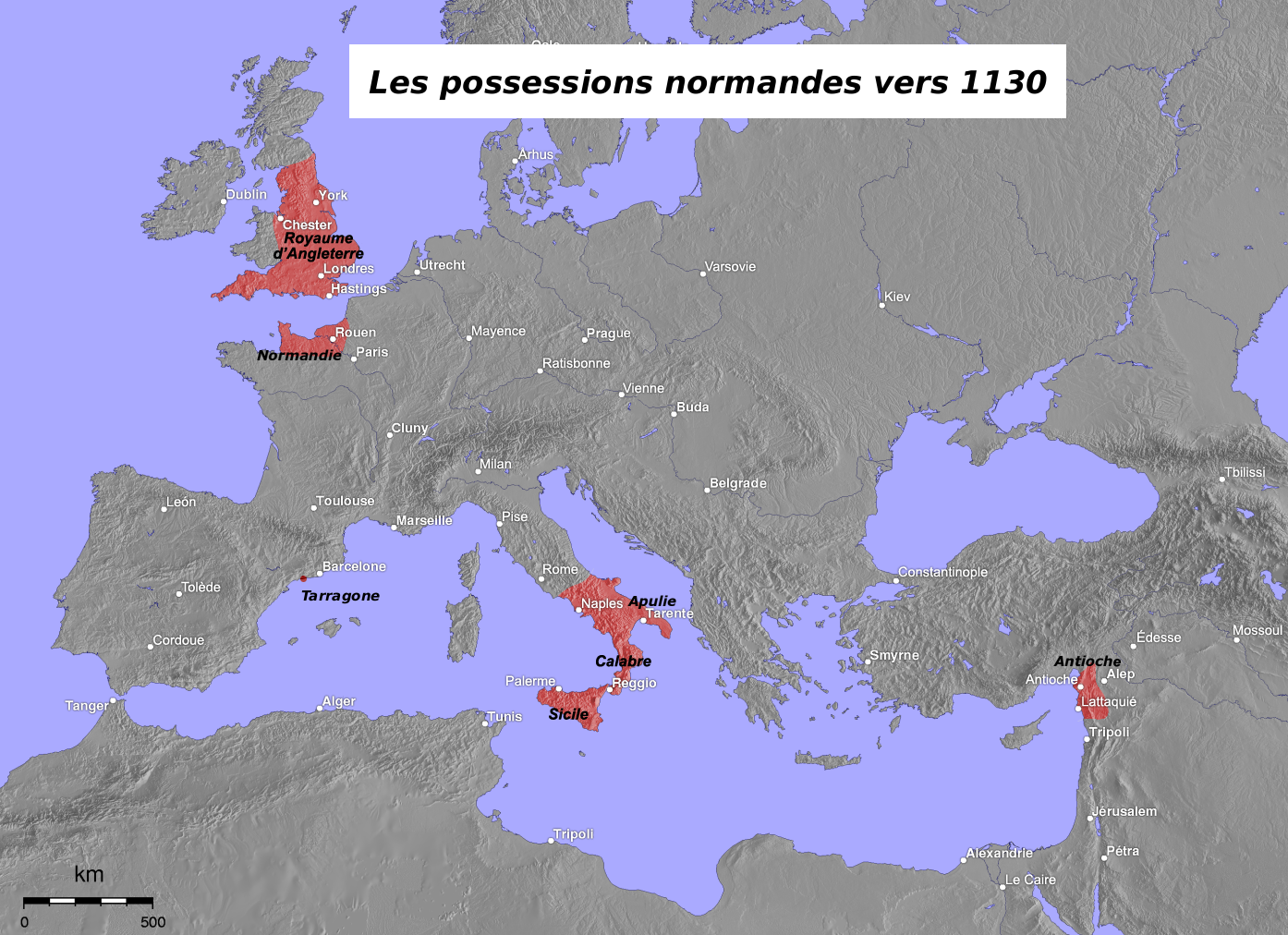

Aside from the conquest of England and the subsequent invasions of Wales and Ireland, the Normans expanded into other areas. Norman families, such as that of

Aside from the conquest of England and the subsequent invasions of Wales and Ireland, the Normans expanded into other areas. Norman families, such as that of

In 1204, during the reign of

In 1204, during the reign of

During the Second World War, following the

During the Second World War, following the

The historical Duchy of Normandy was a formerly independent duchy occupying the lower Seine area, the

The historical Duchy of Normandy was a formerly independent duchy occupying the lower Seine area, the

*

*

Rivers in Normandy include:

* the Seine and its tributaries:

** the Andelle

** the

Rivers in Normandy include:

* the Seine and its tributaries:

** the Andelle

** the

The main cities (population given from the 1999 census) are Rouen (518,316 in the metropolitan area), the capital since 2016 of the province and formerly of Upper Normandy; Caen (420,000 in the metropolitan area) and formerly the capital of Lower Normandy;

The main cities (population given from the 1999 census) are Rouen (518,316 in the metropolitan area), the capital since 2016 of the province and formerly of Upper Normandy; Caen (420,000 in the metropolitan area) and formerly the capital of Lower Normandy;

File:Flag of Normandie.svg, "Two-leopard" version, which is the main one.

File:Flag of Normandie (three-leopard version).svg, "Three-leopard" version

File:Flag of Normandy.svg,

Architecturally, Norman cathedrals, abbeys (such as the

Architecturally, Norman cathedrals, abbeys (such as the

Parts of Normandy consist of rolling countryside typified by pasture for dairy cattle and apple orchards. A wide range of dairy products are produced and exported. Norman cheeses include

Parts of Normandy consist of rolling countryside typified by pasture for dairy cattle and apple orchards. A wide range of dairy products are produced and exported. Norman cheeses include  Turbot and oysters from the Cotentin Peninsula are major delicacies throughout France. Normandy is the chief

Turbot and oysters from the Cotentin Peninsula are major delicacies throughout France. Normandy is the chief

The dukes of Normandy commissioned and inspired epic literature to record and legitimise their rule.

The dukes of Normandy commissioned and inspired epic literature to record and legitimise their rule.

Normandy has a rich tradition of painting and gave to France some of its most important artists.

In the 17th century some major French painters were Normans like Nicolas Poussin, born in Les Andelys and

Normandy has a rich tradition of painting and gave to France some of its most important artists.

In the 17th century some major French painters were Normans like Nicolas Poussin, born in Les Andelys and

Christian missionaries implanted

Christian missionaries implanted

File:MSM sunset 02.JPG, Mont Saint-Michel

File:Château Gaillard.jpg,

Normandie Héritage

Gallery of photos of Normandy

{{Authority control Former provinces of France Divided regions Geographical, historical and cultural regions of France Historical regions

Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intellig ...

, plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a result of the Norman c ...

.

Normandy comprises mainland Normandy (a part of France) and the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

(mostly the British Crown Dependencies). It covers . Its population is 3,499,280. The inhabitants of Normandy are known as Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

, and the region is the historic homeland of the Norman language. Large settlements include Rouen, Caen, Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

and Cherbourg.

The cultural region of Normandy is roughly similar to the historical Duchy of Normandy, which includes small areas now part of the departments of Mayenne

Mayenne () is a landlocked department in northwest France named after the river Mayenne. Mayenne is part of the administrative region of Pays de la Loire and is surrounded by the departments of Manche, Orne, Sarthe, Maine-et-Loire, and Ill ...

and Sarthe

Sarthe () is a department of the French region of Pays de la Loire, and the province of Maine, situated in the '' Grand-Ouest'' of the country. It is named after the river Sarthe, which flows from east of Le Mans to just north of Angers. It ha ...

. The Channel Islands (French: ''Îles Anglo-Normandes'') are also historically part of Normandy; they cover and comprise two bailiwicks: Guernsey and Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label= Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the l ...

, which are British Crown Dependencies.

Normandy's name comes from the settlement of the territory by Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

s ("Northmen

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the pre ...

") starting in the 9th century, and confirmed by treaty in the 10th century between King Charles III of France

Charles III (17 September 879 – 7 October 929), called the Simple or the Straightforward (from the Latin ''Carolus Simplex''), was the king of West Francia from 898 until 922 and the king of Lotharingia from 911 until 919–923. He was a mem ...

and the Viking ''jarl

Jarl is a rank of the nobility in Scandinavia. In Old Norse, it meant "chieftain", particularly a chieftain set to rule a territory in a king's stead. ''Jarl'' could also mean a sovereign prince. For example, the rulers of several of the petty k ...

'' Rollo

Rollo ( nrf, Rou, ''Rolloun''; non, Hrólfr; french: Rollon; died between 928 and 933) was a Viking who became the first ruler of Normandy, today a region in northern France. He emerged as the outstanding warrior among the Norsemen who had se ...

. For almost 150 years following the Norman conquest of England in 1066, Normandy and England were linked by having the same person reign as both Duke of Normandy and King of England.

History

Prehistory

Archaeological finds, such ascave paintings

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,000 y ...

, prove that humans were present in the region in prehistoric times. Normandy has also many megalithic monument

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

s.

Celtic period

Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

(also known as Belgae and Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They s ...

) have populated Normandy since at least the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

. When Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, ...

invaded Gaul (58–50 BC), there were nine different Celtic tribes living in this part of Gaul.

Romanisation

TheRomanisation

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

of this region partly included in the ''Gallia Celtica

Gallia Celtica, meaning "Celtic Gaul" in Latin, was a cultural region of Gaul inhabited by Celts, located in what is now France, Switzerland, Luxembourg and the west bank of the Rhine in Germany.

According to the Roman ethnography and Julius Ca ...

'' and in the ''Gallia Belgica

Gallia Belgica ("Belgic Gaul") was a province of the Roman Empire located in the north-eastern part of Roman Gaul, in what is today primarily northern France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, along with parts of the Netherlands and Germany.

In 50 BC, a ...

'' (the Seine being more or less the limit between them) was achieved by the usual methods: Roman roads

Roman roads ( la, viae Romanae ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Re ...

and a policy of urbanisation. Classicist

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

s mention many Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context ...

villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the fall of the Roman Republic, villas became s ...

s and archeology found their traces in the past 30 years. In the Late Roman Empire

The Later Roman Empire spans the period from 284 AD (Diocletian's proclamation as emperor) to 641 (death of Heraclius) in the history of the Roman Empire.

Evidence

Histories

In comparison with previous periods, studies on Later Roman history a ...

a new province was created and called ''Lugdunensis Secunda

Gallia Lugdunensis ( French: ''Gaule Lyonnaise'') was a province of the Roman Empire in what is now the modern country of France, part of the Celtic territory of Gaul formerly known as Celtica. It is named after its capital Lugdunum (today's Lyo ...

'', it sketched the later ecclesiastical province of Rouen, with the ''Metropolis civitas Rotomagensium''

(Rouen), ''Civitas Baiocassium'' (''Augustodorum'', Bayeux), ''Civitas Abrincatum'' (''Ingena'', Avranches), ''Civitas Ebroicorum'' (''Mediolanum'', Évreux), ''Civitas Saiorum'' (Sées), ''Civitas Lexoviorum'' (''Noviomagus'', Lisieux / Lieuvin) and ''Civitas Constantia'' (Coutances).

Germanic invasions and settlements

In the late 3rd century AD, Germanic raids devastated ″Lugdunensis Secunda″ as the modern area of Normandy was known as at the time. The Romans built a system of coastal defences known as Saxon Shore on both sides of the English channel. Coastal settlements were raided by Saxon pirates, that finally settled mainly in the Bessin region. Modern archeology reveals their presence in different Merovingian cemeteries excavated east of Caen. Christianity also began to enter the area during this period and Rouen already had a metropolitan bishop by the 4th century. The ecclesiastical province of Rouen was based on the frame of the Roman ''Lugdunensis Secunda'', whose limits corresponded almost exactly to the future duchy of Normandy. In 406,Germanic tribes

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and e ...

began invading from the east, followed by dispersed settlements mainly in pays de Bray

The Pays de Bray (, literally ''Land of Bray'') is a small (about 750 km²) natural region of France situated to the north-east of Rouen, straddling the French departments of the Seine-Maritime and the Oise (historically divided among the ...

, pays de Caux

The Pays de Caux (, , literally ''Land of Caux'') is an area in Normandy occupying the greater part of the French ''département'' of Seine Maritime in Normandy. It is a chalk plateau to the north of the Seine Estuary and extending to the cliffs o ...

and Vexin

Vexin () is an historical county of northwestern France. It covers a verdant plateau on the right bank (north) of the Seine running roughly east to west between Pontoise and Romilly-sur-Andelle (about 20 km from Rouen), and north to south ...

. As early as 487, the area between the River Somme and the River Loire

The Loire (, also ; ; oc, Léger, ; la, Liger) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône ...

came under the control of the Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages

* Francia, a post-Roman state in France and Germany

* East Francia, the successor state to Francia in Germany ...

lord Clovis.

Viking raids and foundation of the Norman state

Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and ...

started to raid along the river Seine during the middle of the 9th century. As early as 841, a Viking fleet appeared at the mouth of the Seine, the principal route by which they entered the kingdom. After attacking and destroying monasteries, including one at Jumièges

Jumièges () is a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region in north-western France.

Geography

A forestry and farming village situated in a meander of the river Seine, some west of Rouen, at the junction of the D 65 and th ...

, they took advantage of the power vacuum created by the disintegration of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

's empire to take northern France. The fiefdom of Normandy was created for the Viking leader ''Hrólfr'', known in Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functione ...

as ''Rollo''. Rollo had besieged Paris but in 911 entered vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

age to the king of the West Franks

In medieval history, West Francia (Medieval Latin: ) or the Kingdom of the West Franks () refers to the western part of the Frankish Empire established by Charlemagne. It represents the earliest stage of the Kingdom of France, lasting from about ...

, Charles the Simple

Charles III (17 September 879 – 7 October 929), called the Simple or the Straightforward (from the Latin ''Carolus Simplex''), was the king of West Francia from 898 until 922 and the king of Lotharingia from 911 until 919–923. He was a mem ...

, through the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte

The treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte (911) is the foundational document of the Duchy of Normandy, establishing Rollo, a Norse warlord and Viking leader, as the first Duke of Normandy in exchange for his loyalty to the king of West Francia, followi ...

. In exchange for his homage and fealty, Rollo legally gained the territory that he and his Viking allies had previously conquered. The name "Normandy" reflects Rollo's Viking (i.e. " Norseman") origins.

The descendants of ''Rollo'' and his followers created an aristocracy that step by step adopted the local Gallo-Romance language, intermarried with the area's native Gallo-Frankish inhabitants, and adopted Christianity. Nevertheless, the first generations of Scandinavian and Anglo-Scandinavian settlers brought slaves, mainly from the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

, and often turned the women into '' frilla'', a Scandinavian tradition which became known as ''more Danico

The phrase ''more danico'' is a Medieval Latin legal expression which may be translated as "according to Danish custom", i.e. under Medieval Scandinavian customary law.

It designates a type of traditional marriage practiced in northern Europe ...

'', medieval Latin meaning "Danish marriage". The first counts of Rouen and the dukes of Normandy had concubines too. While very little archeological excavations about the Vikings were done in Normandy, the Norman toponymy Placenames in Normandy have a variety of origins. Some belong to the common heritage of the Langue d'oïl extension zone in northern France and Belgium; this is called "Pre-Normanic". Others contain Old Norse and Old English male names and topony ...

retains a large Scandinavian and Anglo-Scandinavian heritage, due to a constant use of Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlemen ...

during four or five generations in certain parts of Normandy.

They then became the Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

– a Norman French-speaking mixture of Norsemen and indigenous Gallo-Franks.

Rollo's descendant William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

became king of England in 1066 after defeating Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson ( – 14 October 1066), also called Harold II, was the last crowned Anglo-Saxon English king. Harold reigned from 6 January 1066 until his death at the Battle of Hastings, fighting the Norman invaders led by William the ...

, the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings

The Heptarchy were the seven petty kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England that flourished from the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th century until they were consolidated in the 8th century into the four kingdoms of Mercia, Northumbria, Wes ...

, at the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings nrf, Batâle dé Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, the Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conque ...

, while retaining the fiefdom

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of f ...

of Normandy for himself and his descendants.

Norman expansion

Aside from the conquest of England and the subsequent invasions of Wales and Ireland, the Normans expanded into other areas. Norman families, such as that of

Aside from the conquest of England and the subsequent invasions of Wales and Ireland, the Normans expanded into other areas. Norman families, such as that of Tancred of Hauteville

Tancred of Hauteville (c. 980 – 1041) was an 11th-century Norman petty lord about whom little is known. He was a minor noble near Coutances in the Cotentin. Tancred is also known by the achievements of his twelve sons.

Various legends arose ...

, Rainulf Drengot Rainulf Drengot (also Ranulph, Ranulf, or Rannulf; died June 1045) was a Norman adventurer and mercenary in southern Italy. In 1030 he became the first count of Aversa. He was a member of the Drengot family.

Early life and arrival in Italy

When ...

and Guimond de Moulins Guimond is a surname. Guimont is the original French spelling. Notable people with the surname include:

* Arthé Guimond (1931–2013), Canadian Roman Catholic bishop

* Claude Guimond (born 1963), Canadian politician

*Colette Guimond (born 1961), C ...

played important parts in the conquest of southern Italy and the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

.

The Drengot lineage, de Hauteville's sons William Iron Arm

William I of Hauteville (before 1010 – 1046), known as William Iron Arm,Guillaume Bras-de-fer in French, Guglielmo Braccio di Ferro in Italian and Gugghiermu Vrazzu di Ferru in Sicilian. was a Norman adventurer who was the founder of the ...

, Drogo, and Humphrey

Humphrey is both a masculine given name and a surname. An earlier form, not attested since Medieval times, was Hunfrid.

Notable people with the name include:

People with the given name Medieval period

:''Ordered chronologically''

*Hunfrid of P ...

, Robert Guiscard and Roger the Great Count progressively claimed territories in southern Italy until founding the Kingdom of Sicily in 1130. They also carved out a place for themselves and their descendants in the Crusader states of Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and the Holy Land.

The 14th-century explorer Jean de Béthencourt

Jean de Béthencourt () (1362–1425) was a French explorer who in 1402 led an expedition to the Canary Islands, landing first on the north side of Lanzarote. From there he conquered for Castile the islands of Fuerteventura (1405) and El ...

established a kingdom

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

in the Canary Islands in 1404. He received the title King of the Canary Islands from Pope Innocent VII but recognized Henry III of Castile

Henry III of Castile (4 October 1379 – 25 December 1406), called the Suffering due to his ill health (, ), was the son of John I and Eleanor of Aragon. He succeeded his father as King of Castile in 1390.

Birth and education

Henry was bor ...

as his overlord, who had provided him with military and financial aid during the conquest.

13th to 17th centuries

In 1204, during the reign of

In 1204, during the reign of John of England

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin Emp ...

, mainland Normandy was taken from the English kingdom by the King of France Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

, that ended with this conquest some 293 years of relative Norman independence from the French crown. Insular Normandy (the Channel Islands) remained, however, under control of the king of England and still attached to the ecclesiastical province of Rouen. In 1259, Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry a ...

recognized the legality of French possession of mainland Normandy under the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

. His successors, however, often fought to regain control of their ancient fiefdom.

The ''Charte aux Normands'' granted by Louis X of France

Louis X (4 October 1289 – 5 June 1316), known as the Quarrelsome (french: le Hutin), was King of France from 1314 and King of Navarre as Louis I from 1305 until his death. He emancipated serfs who could buy their freedom and readmitted Jews in ...

in 1315 (and later re-confirmed in 1339) – like the analogous Magna Carta granted in England in the aftermath of 1204 – guaranteed the liberties and privileges of the province of Normandy.

French Normandy was devastated by the civil wars and conflicts against the English power during the Hundred Years' War. Between 1419 and 1450 strong English forces occupied Normandy, except the Mont-Saint-Michel

Mont-Saint-Michel (; Norman: ''Mont Saint Miché''; ) is a tidal island and mainland commune in Normandy, France.

The island lies approximately off the country's north-western coast, at the mouth of the Couesnon River near Avranches and i ...

, and made of Rouen, the seat of their power in France. It explains why Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc (french: link=yes, Jeanne d'Arc, translit= �an daʁk} ; 1412 – 30 May 1431) is a patron saint of France, honored as a defender of the French nation for her role in the siege of Orléans and her insistence on the coronat ...

was burnt in Rouen, but not in Paris. Normandy lost three-quarters of its population during the war. Afterwards, prosperity returned to Normandy until the Wars of Religion

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to wh ...

. When many Norman towns ( Alençon, Rouen, Caen, Coutances

Coutances () is a commune in the Manche department in Normandy in north-western France.

History

Capital of the Unelli, a Gaulish tribe, the town was given the name of ''Constantia'' in 298 during the reign of Roman emperor Constantius Chloru ...

, Bayeux) joined the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

, battles ensued throughout the province. In the Channel Islands, a period of Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

following the Reformation was suppressed when Anglicanism was imposed following the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

.

Samuel de Champlain left the port of Honfleur

Honfleur () is a commune in the Calvados department in northwestern France. It is located on the southern bank of the estuary of the Seine across from le Havre and very close to the exit of the Pont de Normandie. The people that inhabit Honf ...

in 1604 and founded Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

. Four years later, he founded the City of Québec. From then onwards, Normans engaged in a policy of expansion in North America. They continued the exploration of the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

: René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle travelled in the area of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lak ...

, then on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

. Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

and his brother Lemoyne de Bienville founded Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, Biloxi

Biloxi ( ; ) is a city in and one of two county seats of Harrison County, Mississippi, United States (the other being the adjacent city of Gulfport). The 2010 United States Census recorded the population as 44,054 and in 2019 the estimated popu ...

, Mobile and New Orleans. Territories located between Québec and the Mississippi Delta were opened up to establish Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

and Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

. Colonists from Normandy were among the most active in New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

, comprising Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

, Canada, and Louisiana.

Honfleur and Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

were two of the principal slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

ports of France.

Modern history

Although agriculture remained important, industries such as weaving, metallurgy, sugar refining, ceramics, and shipbuilding were introduced and developed. In the 1780s, the economic crisis and the crisis of the ''Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for ...

'' struck Normandy as well as other parts of the nation, leading to the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

. Bad harvests, technical progress and the effects of the Eden Agreement signed in 1786 affected employment and the economy of the province. Normans laboured under a heavy fiscal burden.

In 1790 the five departments of Normandy replaced the former province.

13 July 1793, the Norman Charlotte Corday assassinated Marat

Marat may refer to:

People

*Marat (given name)

*Marat (surname)

**Jean-Paul Marat (1743-1793), French political theorist, physician and scientist

Arts, entertainment, and media

*''Marat/Sade'', a 1963 play by Peter Weiss

* ''Marat/Sade'' (fil ...

.

The Normans reacted little to the many political upheavals which characterized the 19th century. Overall they warily accepted the changes of régime (First French Empire

The First French Empire, officially the French Republic, then the French Empire (; Latin: ) after 1809, also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental E ...

, Bourbon Restoration, July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (french: Monarchie de Juillet), officially the Kingdom of France (french: Royaume de France), was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 26 July 1830, with the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 23 F ...

, French Second Republic

The French Second Republic (french: Deuxième République Française or ), officially the French Republic (), was the republican government of France that existed between 1848 and 1852. It was established in February 1848, with the February Re ...

, Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930 ...

, French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 19 ...

).

Following the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Prussia ...

and the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

(1792–1815) there was an economic revival that included the mechanization of textile manufacturing and the introduction of the first trains.

With seaside tourism in the 19th century came the advent of the first beach resorts.

During the Second World War, following the

During the Second World War, following the armistice of 22 June 1940

The Armistice of 22 June 1940 was signed at 18:36 near Compiègne, France, by officials of Nazi Germany and the Third French Republic. It did not come into effect until after midnight on 25 June.

Signatories for Germany included Wilhelm Keitel ...

, continental Normandy was part of the German occupied zone of France. The Channel Islands were occupied by German forces between 30 June 1940 and 9 May 1945. The town of Dieppe

Dieppe (; Norman: ''Dgieppe'') is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to N ...

was the site of the unsuccessful Dieppe Raid by Canadian and British armed forces.

The Allies, in this case involving Britain, the United States, Canada and Free France

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

, coordinated a massive build-up of troops and supplies to support a large-scale invasion of Normandy in the D-Day landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

on 6 June 1944 under the code name Operation Overlord. The Germans were dug into fortified emplacements above the beaches. Caen, Cherbourg, Carentan

Carentan () is a small rural town near the north-eastern base of the French Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy in north-western France, with a population of about 6,000. It is a former commune in the Manche department. On 1 January 2016, it was mer ...

, Falaise

Falaise may refer to:

Places

* Falaise, Ardennes, France

* Falaise, Calvados, France

** The Falaise pocket was the site of a battle in the Second World War

* La Falaise, in the Yvelines ''département'', France

* The Falaise escarpment in Quebe ...

and other Norman towns endured many casualties in the Battle of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

, which continued until the closing of the so-called Falaise gap between Chambois and Mont Ormel. The liberation of Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

followed. This was a significant turning point in the war and led to the restoration of the French Republic.

The remainder of Normandy was liberated only on 9 May 1945 at the end of the war, when the Channel Island occupation effectively ended.

Geography

Pays de Caux

The Pays de Caux (, , literally ''Land of Caux'') is an area in Normandy occupying the greater part of the French ''département'' of Seine Maritime in Normandy. It is a chalk plateau to the north of the Seine Estuary and extending to the cliffs o ...

and the region to the west through the Pays d'Auge

The Pays d'Auge (, literally ''Land of Auge'') is an area in Normandy, straddling the ''départements'' of Calvados and Orne (plus a small part of the territory of Eure). The chief town is Lisieux.

Geography

Generally it consists of the basin o ...

as far as the Cotentin Peninsula

The Cotentin Peninsula (, ; nrf, Cotentîn ), also known as the Cherbourg Peninsula, is a peninsula in Normandy that forms part of the northwest coast of France. It extends north-westward into the English Channel, towards Great Britain. To its w ...

and Channel Islands.

Western Normandy belongs to the Armorican Massif

The Armorican Massif (french: Massif armoricain, ) is a geologic massif that covers a large area in the northwest of France, including Brittany, the western part of Normandy and the Pays de la Loire. It is important because it is connected to Dov ...

, while most of the region lies in the Paris Basin

The Paris Basin is one of the major geological regions of France. It developed since the Triassic over remnant uplands of the Variscan orogeny (Hercynian orogeny). The sedimentary basin, no longer a single drainage basin, is a large sag in th ...

. France's oldest rocks are exposed in Jobourg, on the Cotentin

The Cotentin Peninsula (, ; nrf, Cotentîn ), also known as the Cherbourg Peninsula, is a peninsula in Normandy that forms part of the northwest coast of France. It extends north-westward into the English Channel, towards Great Britain. To its w ...

peninsula. The region is bounded to the north and west by the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. There are granite cliffs in the west and limestone cliffs in the east. There are also long stretches of beach in the centre of the region. The ''bocage

Bocage (, ) is a terrain of mixed woodland and pasture characteristic of parts of Northern France, Southern England, Ireland, the Netherlands and Northern Germany, in regions where pastoral farming is the dominant land use.

''Bocage'' may als ...

'' typical of the western areas caused problems for the invading forces in the Battle of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

. A notable feature of the landscape is created by the meander

A meander is one of a series of regular sinuous curves in the channel of a river or other watercourse. It is produced as a watercourse erodes the sediments of an outer, concave bank ( cut bank) and deposits sediments on an inner, convex ba ...

s of the Seine as it approaches its estuary.

The highest point is the Signal d'Écouves (417 m), in the Armorican Massif.

Normandy is sparsely forested: 12.8% of the territory is wooded, compared to a French average of 23.6%, although the proportion varies between the departments. Eure has the most cover, at 21%, while Manche has the least, at 4%, a characteristic shared with the Channel Islands.

Sub-regions

Mainland Normandy

*Avranchin

Avranchin is an area in Normandy, France corresponding to the territory of the Abrincatui, a tribe of Celts from whom the city of Avranches, the main town of the Avranchin, takes its name.

In 867, by the Treaty of Compiègne, Charles the Bald gave ...

* Bessin

* Bauptois

* Bocage virois

* Campagne d'Alençon

* Campagne d'Argentan

* Campagne de Caen

* Campagne de Falaise

* Campagne du Neubourg

* Campagne de Saint-André (or d’Évreux)

* Cotentin

The Cotentin Peninsula (, ; nrf, Cotentîn ), also known as the Cherbourg Peninsula, is a peninsula in Normandy that forms part of the northwest coast of France. It extends north-westward into the English Channel, towards Great Britain. To its w ...

* Perche

* Domfrontais or Passais

* Hiémois

Exmes is a former commune in the Orne department in north-western France. On 1 January 2017, it was merged into the new commune Gouffern en Auge.Lieuvin

The Lieuvin () is a plateau region in the western part of the Eure ''département'' in Normandy, France.

The plateau consists of typical Norman ''bocage'' and is bounded by the Seine estuary to the north, the Risle valley to the east, the Char ...

* Mortain

Mortain () is a former commune in the Manche department in Normandy in north-western France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune of Mortain-Bocage.

Geography

Mortain is situated on a rocky hill rising above the gorge of the ...

ais

* Pays d'Auge

The Pays d'Auge (, literally ''Land of Auge'') is an area in Normandy, straddling the ''départements'' of Calvados and Orne (plus a small part of the territory of Eure). The chief town is Lisieux.

Geography

Generally it consists of the basin o ...

, central Normandy, is characterized by excellent agricultural land.

* Pays de Bray

The Pays de Bray (, literally ''Land of Bray'') is a small (about 750 km²) natural region of France situated to the north-east of Rouen, straddling the French departments of the Seine-Maritime and the Oise (historically divided among the ...

* Pays de Caux

The Pays de Caux (, , literally ''Land of Caux'') is an area in Normandy occupying the greater part of the French ''département'' of Seine Maritime in Normandy. It is a chalk plateau to the north of the Seine Estuary and extending to the cliffs o ...

* Pays d'Houlme

* Pays de Madrie, area between the Seine and the Eure.

* Pays d'Ouche

The Pays d'Ouche (, literally ''Land of Ouche'') is an historical and geographical region in Normandy. It extends from the southwest of Évreux up to Bernay and Beaumont-le-Roger as a northern limit, and down to L'Aigle and to Gacé in the south. ...

* Roumois

The Roumois () is a region in the northwestern part of the Eure ''département'' in Normandy, France. It is a plateau situated southwest of Rouen. Its northern boundary is the Seine downstream of Elbeuf, its western boundary is the Risle valley. T ...

et Marais-Vernier

Marais-Vernier () is a commune in the Eure department in Normandy in northern France. It is situated near the left bank of the Seine, at the edge of a wetland (the ''Marais Vernier'') formed by an old branch of the Seine. The wetland was cut off ...

* Suisse Normande (Norman Switzerland

Norman Switzerland (french: Suisse Normande) is a part of Normandy, France, in the border region of the departments Calvados and Orne. Its name comes from its rugged and verdant relief resembling the Swiss Alps, with gorges carved by the river Or ...

), in the south, presents hillier terrain.

* Val de Saire

The Val de Saire (or Vale of the River Saire) is an area situated in the north of the Cotentin Peninsula, to the east of Cherbourg in the French region of Lower Normandy. To the south lies the Plain. It is named after the river Saire, which flo ...

*

* Vexin normand

Vexin () is an historical county of northwestern France. It covers a verdant plateau on the right bank (north) of the Seine running roughly east to west between Pontoise and Romilly-sur-Andelle (about 20 km from Rouen), and north to sout ...

Insular Normandy (Channel Islands)

* The bailiwick ofJersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label= Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the l ...

* The bailiwick of Guernsey (Fr. ''Bailliage de Guernesey'')

The Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

are considered culturally and historically a part of Normandy. However, they are British Crown Dependencies, and are not part of the modern French administrative region of Normandy,

Although the British surrendered claims to mainland Normandy, France, and other French possessions in 1801, the monarch of the United Kingdom retains the title Duke of Normandy in respect to the Channel Islands. The Channel Islands (except for Chausey

Chausey () is a group of small islands, islets and rocks off the coast of Normandy, in the English Channel. It lies from Granville and forms a ''quartier'' of the Granville commune in the Manche ''département''. Chausey forms part of the Chan ...

) remain Crown Dependencies of the British Crown in the present era. Thus the Loyal Toast

A loyal toast is a salute given to the sovereign monarch or head of state of the country in which a formal gathering is being given, or by expatriates of that country, whether or not the particular head of state is present. It is usually a mat ...

in the Channel Islands is ''Le Roi, notre Duc'' ("The King, our Duke"). The British monarch is understood to ''not'' be the Duke with regards to mainland Normandy described herein, by virtue of the Treaty of Paris of 1259, the surrender of French possessions in 1801, and the belief that the rights of succession to that title are subject to Salic Law which excludes inheritance through female heirs.

Rivers

Rivers in Normandy include:

* the Seine and its tributaries:

** the Andelle

** the

Rivers in Normandy include:

* the Seine and its tributaries:

** the Andelle

** the Epte

The Epte () is a river in Seine-Maritime and Eure, in Normandy, France. It is a right tributary of the Seine, long. The river rises in Seine-Maritime in the Pays de Bray, near Forges-les-Eaux. The river empties into the Seine not far from Give ...

** the Eure

** the Risle

The Risle (; less common: ''Rille'') is a long river in Normandy, left tributary of the Seine.

The river begins in the Orne department west of L'Aigle, crosses the western part of the department of Eure flowing from south to north and out into ...

** the Robec

The Robec (Old Norse ''raudh'', red and ''bekkr'', stream) is a small river in Seine-Maritime, Normandy, France. Its length is 8.9 km. The river begins near Fontaine-sous-Préaux, then it flows through Darnétal and ends in the Aubette in ...

And many coastal rivers:

* the Bresle

* the Couesnon

The Couesnon (; br, Kouenon) is a river running from the ''département'' of Mayenne in north-western France, forming an estuary at Mont Saint-Michel. It is long, and its drainage basin is . Its final stretch forms the border between the histor ...

, which traditionally marks the boundary between the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany ( br, Dugelezh Breizh, ; french: Duché de Bretagne) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of Europe, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean t ...

and the Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a result of the Norman c ...

* the Dives

* the Orne

Orne (; nrf, Ôrne or ) is a département in the northwest of France, named after the river Orne. It had a population of 279,942 in 2019.Sée

The Sée is a 79 km long river in the Manche department, Normandy, France, beginning near Sourdeval. It empties into the bay of Mont Saint-Michel (part of the English Channel) in Avranches, close to the mouth of the Sélune

The Sélune is ...

* the Sélune

The Sélune is an 85 km long river in the Manche department, Normandy, France, beginning near Saint-Cyr-du-Bailleul. It empties into the bay of Mont Saint-Michel (part of the English Channel) near Avranches, close to the mouth of the Sée ...

* the Touques

* the Veules, the shortest French coastal river

* the Vire

Vire () is a town and a former commune in the Calvados department in the Normandy region in northwestern France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune of Vire Normandie.

Geography

The town is located on the river Vire. Much of i ...

Politics

Mainland Normandy

The modern region ofNormandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

was created by the territorial reform of French Regions in 2014 by the merger of Lower Normandy

Lower Normandy (french: Basse-Normandie, ; nrf, Basse-Normaundie) is a former administrative region of France. On 1 January 2016, Lower and Upper Normandy merged becoming one region called Normandy.

Geography

The region included three departme ...

, and Upper Normandy

Upper Normandy (french: Haute-Normandie, ; nrf, Ĥâote-Normaundie) is a former administrative region of France. On 1 January 2016, Upper and Lower Normandy merged becoming one region called Normandy.

History

It was created in 1956 from two d ...

. The new region took effect on 1 January 2016, after the regional elections in December 2015.

The Regional Council has 102 members who are elected under a system of proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to a type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to geographical (e.g. states, regions) and political divis ...

. The executive consists of a president and vice-presidents. Hervé Morin

Hervé Morin (born 17 August 1961) is a French politician of the Centrists who has been serving as the first President of the Regional Council of Normandy since January 2016. Under President Nicolas Sarkozy, he was the Minister of Defence.

Po ...

from the Centre party was elected president of the council in January 2016.

Channel Islands

The Channel Islands are not part of French territory, but are instead British Crown Dependencies. They are self-governing, each having its own parliament, government and legal system. The head of state of both territories isCharles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person t ...

and each have an appointed Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-com ...

.

The Bailiwick of Guernsey comprises three separate jurisdictions: Guernsey, Alderney and Sark

Sark (french: link=no, Sercq, ; Sercquiais: or ) is a part of the Channel Islands in the southwestern English Channel, off the coast of Normandy, France. It is a royal fief, which forms part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, with its own set of ...

. Administratively, Herm forms part of Guernsey.

Economy

Much of Normandy is predominantly agricultural in character, with cattle breeding the most important sector (although in decline from the peak levels of the 1970s and 1980s). The ''bocage

Bocage (, ) is a terrain of mixed woodland and pasture characteristic of parts of Northern France, Southern England, Ireland, the Netherlands and Northern Germany, in regions where pastoral farming is the dominant land use.

''Bocage'' may als ...

'' is a patchwork of small fields with high hedges, typical of western areas. Areas near the Seine (the former Upper Normandy

Upper Normandy (french: Haute-Normandie, ; nrf, Ĥâote-Normaundie) is a former administrative region of France. On 1 January 2016, Upper and Lower Normandy merged becoming one region called Normandy.

History

It was created in 1956 from two d ...

region) contain a higher concentration of industry. Normandy is a significant cider-producing region, and also produces calvados

Calvados (, , ) is a brandy from Normandy in France, made from apples or pears, or from apples with pears.

History In France

Apple orchards and brewers are mentioned as far back as the 8th century by Charlemagne. The first known record of Nor ...

, a distilled cider or apple brandy

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus domestica''). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus ''Malus''. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancestor, ' ...

. Other activities of economic importance are dairy produce, flax (60% of production in France), horse breeding (including two French national stud farms), fishing, seafood, and tourism. The region contains three French nuclear power station

A nuclear power plant (NPP) is a thermal power station in which the heat source is a nuclear reactor. As is typical of thermal power stations, heat is used to generate steam that drives a steam turbine connected to a generator that produces ele ...

s.

There is also easy access to and from the UK using the ports of Cherbourg, Caen (Ouistreham

Ouistreham () is a commune in the Calvados department in Normandy region in northwestern France.

Ouistreham is a small port with fishing boats, leisure craft and a ferry harbour. It serves as the port of the city of Caen. The town borders the ...

), Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

and Dieppe

Dieppe (; Norman: ''Dgieppe'') is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to N ...

. Jersey and Guernsey are often considered to be tax havens, due to having large financial services sectors and low tax rates.

Demographics

In January 2006 the population of French Normandy (including the part of Perche which lies inside theOrne

Orne (; nrf, Ôrne or ) is a département in the northwest of France, named after the river Orne. It had a population of 279,942 in 2019.département

In the administrative divisions of France, the department (french: département, ) is one of the three levels of government under the national level (" territorial collectivities"), between the administrative regions and the communes. Ninety ...

'' but excluding the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

) was estimated at 3,260,000 with an average population density of 109 inhabitants per km2, just under the French national average, but rising to 147 for Upper Normandy

Upper Normandy (french: Haute-Normandie, ; nrf, Ĥâote-Normaundie) is a former administrative region of France. On 1 January 2016, Upper and Lower Normandy merged becoming one region called Normandy.

History

It was created in 1956 from two d ...

. The population of the Channel Islands is estimated around 174,000 (2021).

Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

(296,773 in the metropolitan area); and Cherbourg (117,855 in the metropolitan area).

Culture

Flag

The traditional provincial flag of Normandy, ''gules, two leopards passant or'', is used in the region and its predecessors. The three-leopard version (known in the Norman language as ''les treis cats'', "the three cats") is used by some associations and individuals, especially those who support cultural links with the Channel Islands and England. Jersey and Guernsey use three leopards in their national symbols. The leopards represents the strength and courage Normandy has towards the neighbouring provinces. The unofficial anthem of the region is the song " Ma Normandie".Nordic Cross

A Nordic cross flag is a flag bearing the design of the Nordic or Scandinavian cross, a cross symbol in a rectangular field, with the centre of the cross shifted towards the hoist.

All independent Nordic countries have adopted such flags in t ...

version

File:Flag of Sark.svg, "Two-leopard" flag of Sark

Sark (french: link=no, Sercq, ; Sercquiais: or ) is a part of the Channel Islands in the southwestern English Channel, off the coast of Normandy, France. It is a royal fief, which forms part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, with its own set of ...

File:Arms of William the Conqueror (1066-1087).svg, Coat of arms of the Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a result of the Norman c ...

File:Coat of arms of Guernsey.svg, Coat of arms of Guernsey

The coat of arms of Guernsey is the official symbol of the Channel Island of Guernsey. It is very similar to the arms of Normandy, Jersey and England.

Seal of Guernsey

The Seal of Guernsey closely follows the Coat of Arms, it originates from 12 ...

File:Jersey arms on Piquet House in St Helier.jpg, Coat of arms of Jersey

The coat of arms of Jersey is the heraldic device consisting of a shield charged with three gold leopards on a red field. Utilised unofficially before the 20th century, its status as the coat of arms of the Bailiwick of Jersey was formalized i ...

Language

The Norman language, including its insular variations Jèrriais andGuernésiais

Guernésiais, also known as ''Dgèrnésiais'', Guernsey French, and Guernsey Norman French, is the variety of the Norman language spoken in Guernsey. It is sometimes known on the island simply as "patois". As one of the langues d'oïl, it has it ...

, is a regional language

*

A regional language is a language spoken in a region of a sovereign state, whether it be a small area, a federated state or province or some wider area.

Internationally, for the purposes of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Lan ...

, spoken by a minority of the population on the continent and the islands, with a concentration in the Cotentin Peninsula

The Cotentin Peninsula (, ; nrf, Cotentîn ), also known as the Cherbourg Peninsula, is a peninsula in Normandy that forms part of the northwest coast of France. It extends north-westward into the English Channel, towards Great Britain. To its w ...

in the far west (the Cotentinais

Cotentinais is the dialect of the Norman language spoken in the Cotentin Peninsula of France. It is one of the strongest dialects of the language on the mainland.

Dialects

Due to the relative lack of standardisation of Norman, there are five ...

dialect), and in the Pays de Caux

The Pays de Caux (, , literally ''Land of Caux'') is an area in Normandy occupying the greater part of the French ''département'' of Seine Maritime in Normandy. It is a chalk plateau to the north of the Seine Estuary and extending to the cliffs o ...

in the East (the Cauchois dialect

Cauchois (Norman: ) is one of the eastern dialects of the Norman language that is spoken in and takes its name from the Pays de Caux region of the Seine-Maritime départment.

Status

The Pays de Caux is one of the remaining strongholds of the Nor ...

).

Many words and place names demonstrate the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th c ...

and Norse ( Anglo-Scandinavian) influence in this Oïl language; for example, words : ''mauve'' (seagull), ''fifotte'' (starfish), ''hâ'' (catshark), ''mucre'' (humid, wet), ''(é)griller'' (slide, slip), ''fale'' (throat), etc. place-names : ''-bec'' (stream), ''-fleur'' (river), ''-hou

''-hou'' or ''hou'' is a place-name element found commonly in the Norman toponymy of the Channel Islands and continental Normandy.

Etymology and signification

Its etymology and meaning are disputed, but most specialists think it comes from Sax ...

'' (island), ''-tot'' (homestead), ''-dal'' / ''-dalle'' (valley), ''Hogue'' / ''Hougue'' (hill, mound), ''-lon'' / ''-londe'' (grove, wood), ''-vy'' / ''-vic'' (bay, cove), ''-mare'' (pond), ''-beuf'' (booth, cabin), etc. French is the only official language

An official language is a language given supreme status in a particular country, state, or other jurisdiction. Typically the term "official language" does not refer to the language used by a people or country, but by its government (e.g. judiciary, ...

in continental Normandy and English is also an official language in the Channel Islands.

Architecture

Architecturally, Norman cathedrals, abbeys (such as the

Architecturally, Norman cathedrals, abbeys (such as the Abbey of Bec

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christians, Christian monks and nuns ...

) and castles characterise the former duchy in a way that mirrors the similar pattern of Norman architecture

The term Norman architecture is used to categorise styles of Romanesque architecture developed by the Normans in the various lands under their dominion or influence in the 11th and 12th centuries. In particular the term is traditionally used f ...

in England following the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Con ...

of 1066.

Domestic architecture in upper Normandy is typified by half-timbered buildings that also recall vernacular English architecture, although the farm enclosures of the more harshly landscaped Pays de Caux are a more idiosyncratic response to socio-economic and climatic imperatives. Much urban architectural heritage was destroyed during the Battle of Normandy in 1944 – post-war urban reconstruction, such as in Le Havre and Saint-Lô, could be said to demonstrate both the virtues and vices of modernist

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

and brutalist trends of the 1950s and 1960s. Le Havre, the city rebuilt by Auguste Perret

Auguste Perret (12 February 1874 – 25 February 1954) was a French architect and a pioneer of the architectural use of reinforced concrete. His major works include the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, the first Art Deco building in Paris; the C ...

, was added to Unesco's World Heritage List in 2005.

Vernacular architecture

Vernacular architecture is building done outside any academic tradition, and without professional guidance. This category encompasses a wide range and variety of building types, with differing methods of construction, from around the world, bo ...

in lower Normandy takes its form from granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies under ...

, the predominant local building material. The Channel Islands also share this influence – Chausey

Chausey () is a group of small islands, islets and rocks off the coast of Normandy, in the English Channel. It lies from Granville and forms a ''quartier'' of the Granville commune in the Manche ''département''. Chausey forms part of the Chan ...

was for many years a source of quarried granite, including that used for the construction of Mont Saint-Michel.

The south part of Bagnoles-de-l'Orne

Bagnoles-de-l'Orne is a former commune in the Orne department in northwestern France. On 1 January 2000, Tessé-la-Madeleine and Bagnoles-de-l'Orne merged becoming one town called Bagnoles-de-l'Orne, however, it adopted the former Insee code of T ...

is filled with bourgeois villas in '' Belle Époque'' style with polychrome façades, bow windows and unique roofing. This area, built between 1886 and 1914, has an authentic “Bagnolese” style and is typical of high-society country vacation of the time. The Chapel of Saint Germanus (''Chapelle Saint-Germain'') at Querqueville

Querqueville () is a former commune in the Manche department in north-western France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune of Cherbourg-en-Cotentin.trefoil

A trefoil () is a graphic form composed of the outline of three overlapping rings, used in architecture and Christian symbolism, among other areas. The term is also applied to other symbols with a threefold shape. A similar shape with four ring ...

floorplan incorporates elements of one of the earliest surviving places of Christian worship in the Cotentin – perhaps second only to the Gallo-Roman baptistry at Port-Bail. It is dedicated to Germanus of Normandy.

Gastronomy

Parts of Normandy consist of rolling countryside typified by pasture for dairy cattle and apple orchards. A wide range of dairy products are produced and exported. Norman cheeses include

Parts of Normandy consist of rolling countryside typified by pasture for dairy cattle and apple orchards. A wide range of dairy products are produced and exported. Norman cheeses include Camembert

Camembert (, also , ) is a moist, soft, creamy, surface-ripened cow's milk cheese. It was first made in the late 18th century in Camembert, Normandy, in northwest France. It is sometimes compared in look and taste to brie cheese, albeit wi ...

, Livarot, Pont l'Évêque, Brillat-Savarin, Neufchâtel, Petit Suisse

''Petit-suisse'' (meaning "little Swiss cheese") is a French cheese from the Normandy region.

Production and use

''Petit-suisse'' is a ''fromage frais'', an unripened, unsalted, smooth, and creamy cheese with a texture closer to a very thic ...

and Boursin. Normandy butter and Normandy cream are lavishly used in gastronomic specialties. Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label= Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the l ...

and Guernsey cattle

The Guernsey is a breed of dairy cattle from the island of Guernsey in the Channel Islands. It is fawn or red and white in colour, and is hardy and docile. Its milk is rich in flavour, high in fat and protein, and has a golden-yellow tinge du ...

are famous cattle breeds worldwide, especially to North America.

Turbot and oysters from the Cotentin Peninsula are major delicacies throughout France. Normandy is the chief

Turbot and oysters from the Cotentin Peninsula are major delicacies throughout France. Normandy is the chief oyster

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but not ...

-cultivating, scallop-exporting, and mussel-raising region in France.

Normandy is a major cider-producing region (very little wine is produced). Perry

Perry, also known as pear cider, is an alcoholic beverage made from fermented pears, traditionally the perry pear. It has been common for centuries in England, particularly in Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire. It is also mad ...

is also produced, but in less significant quantities. Apple brandy, of which the most famous variety is calvados

Calvados (, , ) is a brandy from Normandy in France, made from apples or pears, or from apples with pears.

History In France

Apple orchards and brewers are mentioned as far back as the 8th century by Charlemagne. The first known record of Nor ...

, is also popular. The mealtime ''trou normand'', or "Norman hole", is a pause between meal courses in which diners partake of a glassful of calvados in order to improve the appetite and make room for the next course, and this is still observed in many homes and restaurants. ''Pommeau

Pommeau is an alcoholic drink made in north-western France by mixing apple juice with apple brandy: Calvados in Normandy () or lambig in Brittany ().

Considered a mistelle, it is generally consumed as an apéritif, or as an accompaniment to mel ...

'' is an '' apéritif'' produced by blending unfermented cider and apple brandy. Another aperitif is the '' kir normand'', a measure of crème de cassis

Crème de cassis () (also known as Cassis liqueur) is a sweet, dark red liqueur made from blackcurrants.

Several cocktails are made with crème de cassis, including the popular wine cocktail, kir.

It may also be served as an after-dinner liq ...

topped up with cider. ''Bénédictine

Bénédictine () is a herbal liqueur produced in France. It was developed by wine merchant Alexandre Le Grand in the 19th century, and is reputedly flavored with twenty-seven flowers, berries, herbs, roots, and spices.

A drier version, B&B, ...

'' is produced in Fécamp

Fécamp () is a commune in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region in north-western France.

Geography

Fécamp is situated in the valley of the river Valmont, at the heart of the Pays de Caux, on the Alabaster Coast. It is aroun ...

.

Other regional specialities include '' tripes à la mode de Caen'', '' andouilles'' and ''andouillettes'', salade cauchoise

Salade cauchoise () is a traditional potato and celery salad of the cuisine of the Pays de Caux, Normandy, France. Other ingredients sometimes used include diced ham, diced gruyere and walnut kernels. It seasoned with a Norman cider vinegar and ...

, salt meadow (''pré salé'') lamb, seafood (mussels, scallops, lobsters, mackerel...), and '' teurgoule'' (spiced rice pudding).

Normandy dishes include duckling ''à la rouennaise'', sautéed chicken ''yvetois'', and goose ''en daube''. Rabbit is cooked with morels, or ''à la havraise'' (stuffed with truffled pigs' trotters). Other dishes are sheep's trotters ''à la rouennaise'', casseroled veal, larded calf's liver braised with carrots, and veal (or turkey) in cream and mushrooms.

Normandy is also noted for its pastries. Normandy turns out ''douillons'' (pears baked in pastry), ''craquelins'', ''roulettes'' in Rouen, ''fouaces'' in Caen, ''fallues'' in Lisieux