Nobel Week Dialogue on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind."

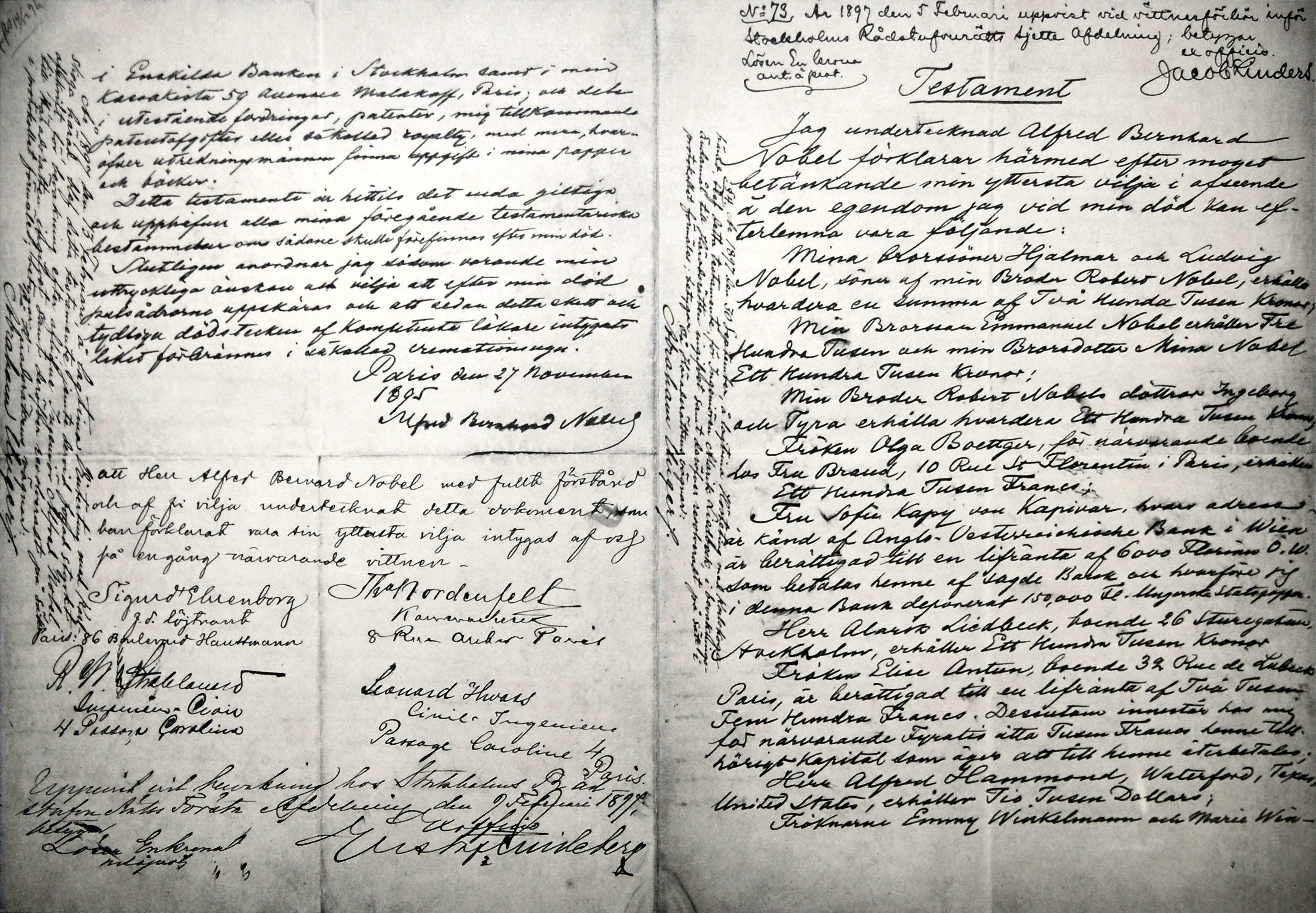

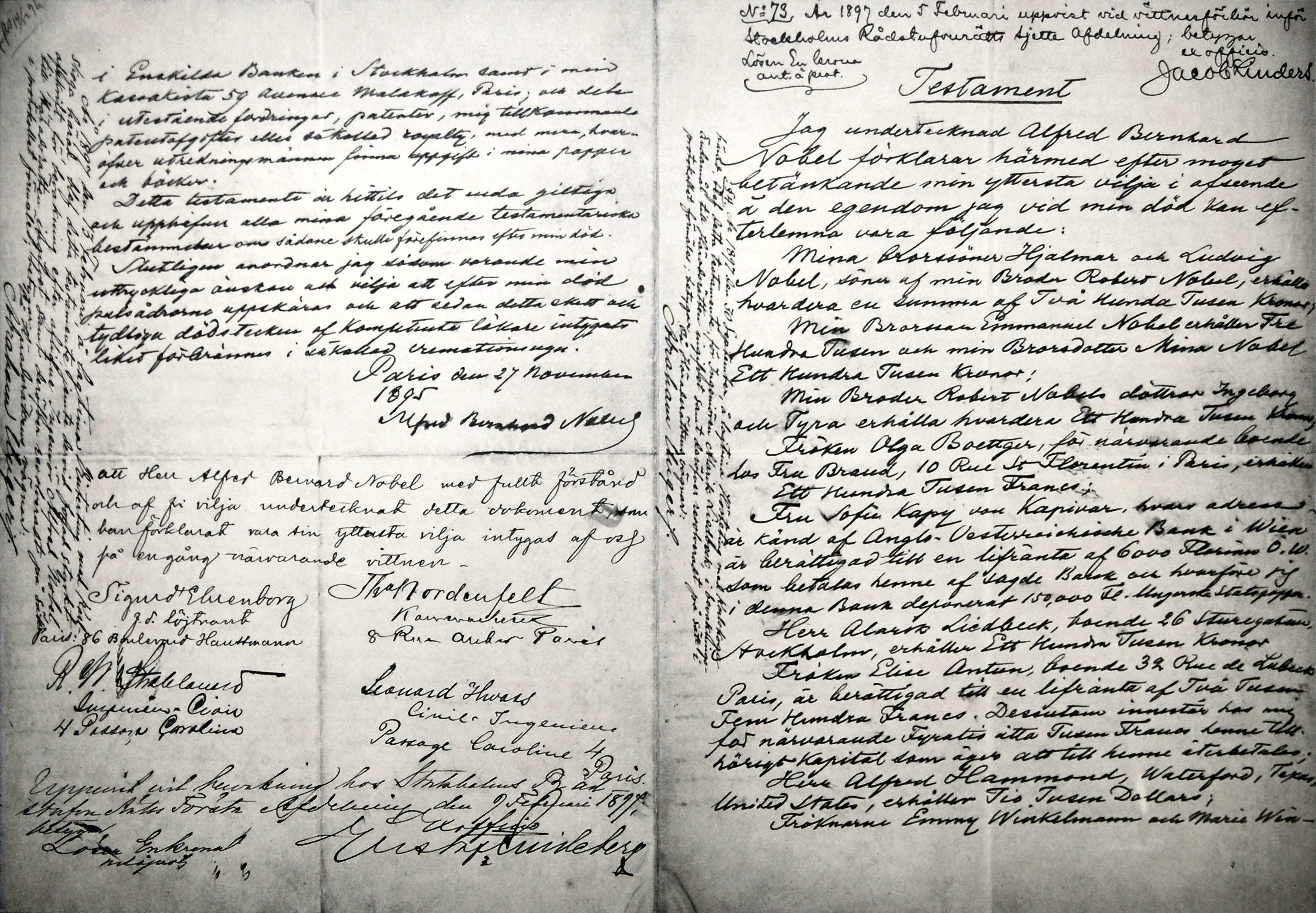

According to his will and testament read in Stockholm on 30 December 1896, a foundation established by Alfred Nobel would reward those who serve humanity. The Nobel Prize was funded by Alfred Nobel's personal fortune. According to the official sources, Alfred Nobel bequeathed most of his fortune to the Nobel Foundation that now forms the economic base of the Nobel Prize.

The Nobel Foundation was founded as a private organization on 29 June 1900. Its function is to manage the finances and administration of the Nobel Prizes. Levinovitz, p. 14 In accordance with Nobel's will, the primary task of the foundation is to manage the fortune Nobel left.

According to his will and testament read in Stockholm on 30 December 1896, a foundation established by Alfred Nobel would reward those who serve humanity. The Nobel Prize was funded by Alfred Nobel's personal fortune. According to the official sources, Alfred Nobel bequeathed most of his fortune to the Nobel Foundation that now forms the economic base of the Nobel Prize.

The Nobel Foundation was founded as a private organization on 29 June 1900. Its function is to manage the finances and administration of the Nobel Prizes. Levinovitz, p. 14 In accordance with Nobel's will, the primary task of the foundation is to manage the fortune Nobel left.

Once the Nobel Foundation and its guidelines were in place, the

Once the Nobel Foundation and its guidelines were in place, the

In 1968, Sweden's central bank

In 1968, Sweden's central bank

The interval between the award and the accomplishment it recognises varies from discipline to discipline. The Literature Prize is typically awarded to recognise a cumulative lifetime body of work rather than a single achievement. The Peace Prize can also be awarded for a lifetime body of work. For example, 2008 laureate

The interval between the award and the accomplishment it recognises varies from discipline to discipline. The Literature Prize is typically awarded to recognise a cumulative lifetime body of work rather than a single achievement. The Peace Prize can also be awarded for a lifetime body of work. For example, 2008 laureate

was caused by awarding the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize to

After the award ceremony in Sweden, a banquet is held in the Blue Hall at the

After the award ceremony in Sweden, a banquet is held in the Blue Hall at the

"Source: Photo by Eric Arnold. Ava Helen and All medals made before 1980 were struck in 23 carat gold. Since then, they have been struck in 18 carat

All medals made before 1980 were struck in 23 carat gold. Since then, they have been struck in 18 carat

Among other criticisms, the Nobel Committees have been accused of having a political agenda, and of omitting more deserving candidates. They have also been accused of

Among other criticisms, the Nobel Committees have been accused of having a political agenda, and of omitting more deserving candidates. They have also been accused of

Although

Although  The Literature Prize also has controversial omissions.

The Literature Prize also has controversial omissions.

In terms of the most prestigious awards in

In terms of the most prestigious awards in

Five people have received two Nobel Prizes.

Five people have received two Nobel Prizes.

Two laureates have voluntarily declined the Nobel Prize. In 1964,

Two laureates have voluntarily declined the Nobel Prize. In 1964,

Nobel Prizes by universities and institutes

{{Authority control Academic awards Alfred Nobel Articles containing video clips Awards established in 1895 International awards Science and technology in Sweden Science and technology awards Swedish science and technology awards Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences 1895 establishments in Sweden

Alfred Nobel

Alfred Bernhard Nobel ( , ; 21 October 1833 – 10 December 1896) was a Swedish chemist, engineer, inventor, businessman, and philanthropist. He is best known for having bequeathed his fortune to establish the Nobel Prize, though he also ...

was a Swedish chemist, engineer, and industrialist most famously known for the invention of dynamite. He died in 1896. In his will, he bequeathed all of his "remaining realisable assets" to be used to establish five prizes which became known as "Nobel Prizes." Nobel Prizes were first awarded in 1901.

Nobel Prizes are awarded in the fields of Physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, according ...

, Literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to inclu ...

, and Peace

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

(Nobel characterized the Peace Prize as "to the person who has done the most or best to advance fellowship among nations, the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and the establishment and promotion of peace congresses"). In 1968, Sveriges Riksbank

Sveriges Riksbank, or simply the ''Riksbank'', is the central bank of Sweden. It is the world's oldest central bank and the fourth oldest bank in operation.

Etymology

The first part of the word ''riksbank'', ''riks'', stems from the Swedish ...

(Sweden's central bank) funded the establishment of the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, to also be administered by the Nobel Foundation. Nobel Prizes are widely regarded as the most prestigious awards available in their respective fields. Shalev, p. 8

The prize ceremonies take place annually. Each recipient (known as a "laureate

In English, the word laureate has come to signify eminence or association with literary awards or military glory. It is also used for recipients of the Nobel Prize, the Gandhi Peace Award, the Student Peace Prize, and for former music direct ...

") receives a gold medal, a diploma

A diploma is a document awarded by an educational institution (such as a college or university) testifying the recipient has graduated by successfully completing their courses of studies. Historically, it has also referred to a charter or offici ...

, and a monetary award. In 2021, the Nobel Prize monetary award is 10,000,000 SEK. A prize may not be shared among more than three individuals, although the Nobel Peace Prize can be awarded to organizations of more than three people. Although Nobel Prizes are not awarded posthumously, if a person is awarded a prize and dies before receiving it, the prize is presented.

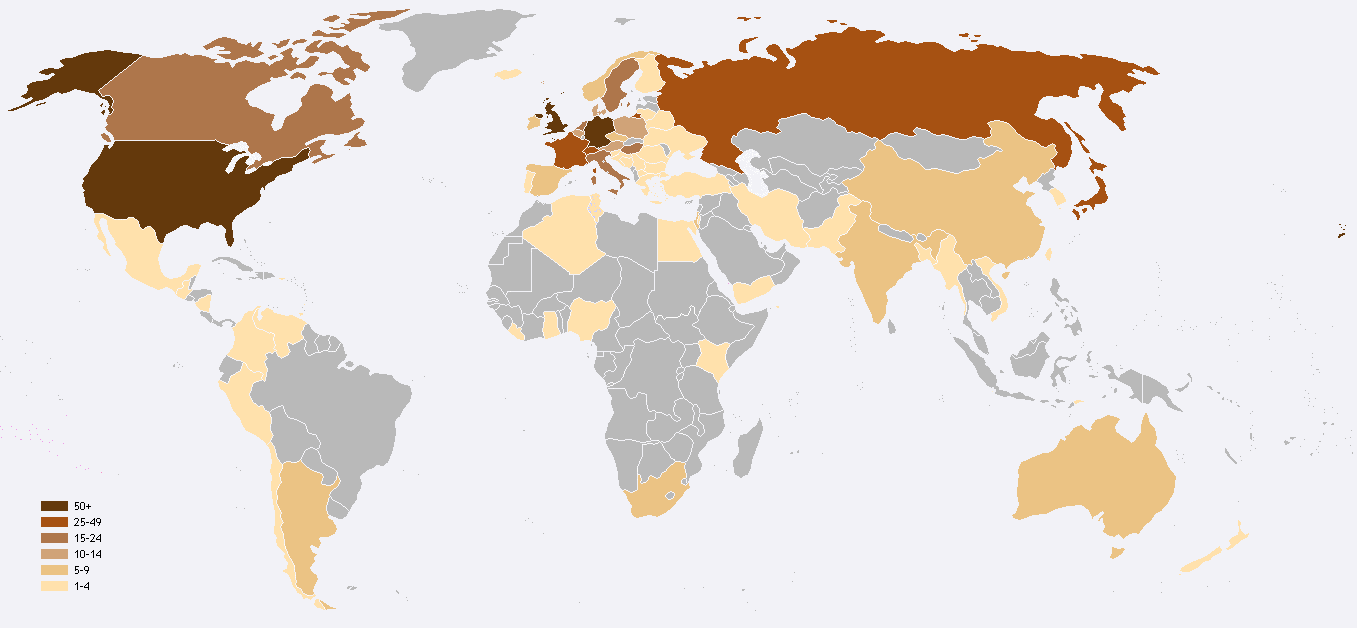

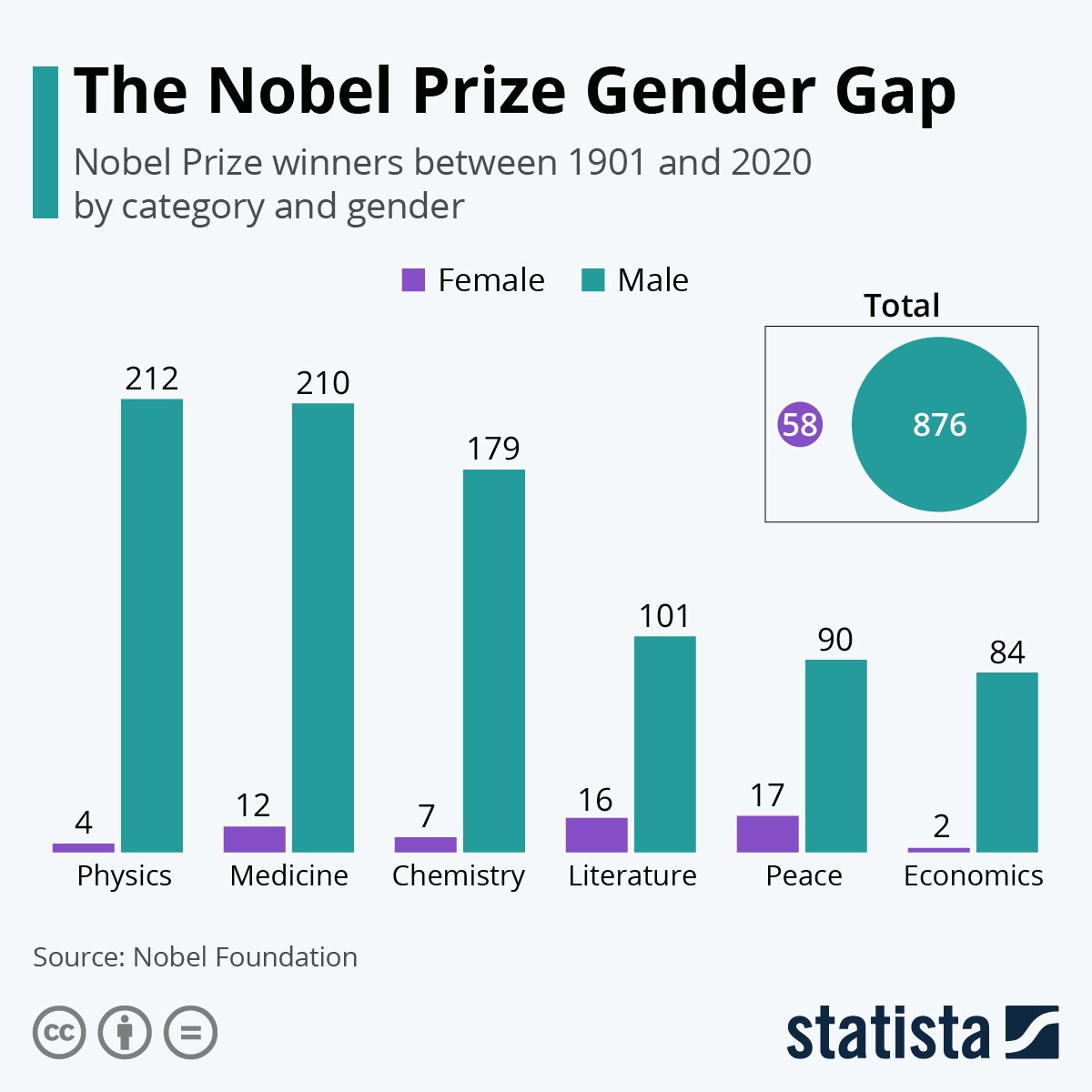

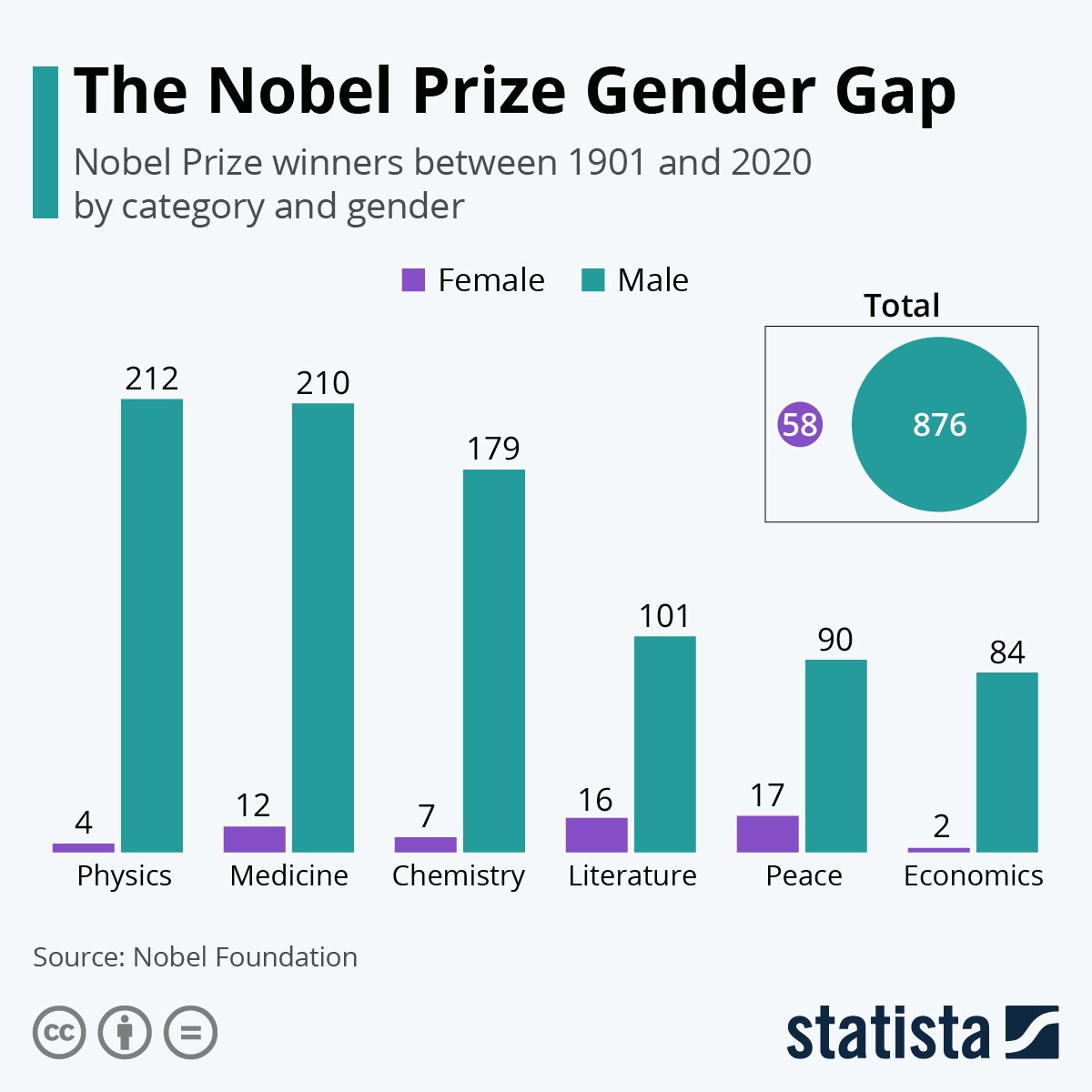

The Nobel Prizes, beginning in 1901, and the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, beginning in 1969, have been awarded 609 times to 975 people and 25 organizations. Five individuals and two organisations have received more than one Nobel Prize.

History

Alfred Nobel

Alfred Bernhard Nobel ( , ; 21 October 1833 – 10 December 1896) was a Swedish chemist, engineer, inventor, businessman, and philanthropist. He is best known for having bequeathed his fortune to establish the Nobel Prize, though he also ...

() was born on 21 October 1833 in Stockholm, Sweden, into a family of engineers. Levinovitz, p. 5 He was a chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe ...

, engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

, and inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an id ...

. In 1894, Nobel purchased the Bofors

AB Bofors ( , , ) is a former Swedish arms manufacturer which today is part of the British arms concern BAE Systems. The name has been associated with the iron industry and artillery manufacturing for more than 350 years.

History

Located ...

iron and steel mill, which he made into a major armaments

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

manufacturer

Manufacturing is the creation or production of goods with the help of equipment, labor, machines, tools, and chemical or biological processing or formulation. It is the essence of secondary sector of the economy. The term may refer to a ...

. Nobel also invented ballistite

Ballistite is a smokeless propellant made from two high explosives, nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. It was developed and patented by Alfred Nobel in the late 19th century.

Military adoption

Alfred Nobel patented https://www.nobelprize.org/a ...

. This invention was a precursor to many smokeless military explosives, especially the British smokeless powder cordite

Cordite is a family of smokeless propellants developed and produced in the United Kingdom since 1889 to replace black powder as a military propellant. Like modern gunpowder, cordite is classified as a low explosive because of its slow burn ...

. As a consequence of his patent claims, Nobel was eventually involved in a patent infringement lawsuit

-

A lawsuit is a proceeding by a party or parties against another in the civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used in reference to a civil actio ...

over cordite. Nobel amassed a fortune during his lifetime, with most of his wealth coming from his 355 inventions, of which dynamite is the most famous. Levinovitz, p. 11

In 1888, Nobel was astonished to read his own obituary, titled "The merchant of death is dead", in a French newspaper. It was Alfred's brother Ludvig

Ludvig is a Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers t ...

who had died; the obituary was eight years premature. The article disconcerted Nobel and made him apprehensive about how he would be remembered. This inspired him to change his will. On 10 December 1896, Alfred Nobel died in his villa in San Remo, Italy, from a cerebral haemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as cerebral bleed, intraparenchymal bleed, and hemorrhagic stroke, or haemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into the tissues of the brain, into its ventricles, or into both. It is one kind of bleed ...

. He was 63 years old. Sohlman, p. 13

Nobel wrote several wills during his lifetime. He composed the last over a year before he died, signing it at the Swedish–Norwegian Club in Paris on 27 November 1895. Sohlman, p. 7 To widespread astonishment, Nobel's last will specified that his fortune be used to create a series of prizes for those who confer the "greatest benefit on mankind" in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

, chemistry, physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemic ...

or medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

, literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to inclu ...

, and peace

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

. Nobel bequeathed 94% of his total assets, 31 million SEK (c. US$186 million, €150 million in 2008), to establish the five Nobel Prizes. Abrams, p. 7 Owing to skepticism surrounding the will, it was not approved by the Storting

The Storting ( no, Stortinget ) (lit. the Great Thing) is the supreme legislature of Norway, established in 1814 by the Constitution of Norway. It is located in Oslo. The unicameral parliament has 169 members and is elected every four years ...

in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

until 26 April 1897. Levinovitz, pp. 13–25 The executors

An executor is someone who is responsible for executing, or following through on, an assigned task or duty. The feminine form, executrix, may sometimes be used.

Overview

An executor is a legal term referring to a person named by the maker of a ...

of the will, Ragnar Sohlman Ragnar Sohlman (February 26, 1870 – July 9, 1948) was a Swedish chemical engineer, manager, civil servant, and creator of the Nobel Foundation.

Biography

Ragnar Sohlman was born in Stockholm to August Sohlman, a well-known newspaper man, ...

and Rudolf Lilljequist, formed the Nobel Foundation to take care of the fortune and to organise the awarding of prizes. Abrams, pp. 7–8

Nobel's instructions named a Norwegian Nobel Committee

The Norwegian Nobel Committee ( no, Den norske Nobelkomité) selects the recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize each year on behalf of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel's estate, based on instructions of Nobel's will.

Five members are appointed by ...

to award the Peace Prize

This list of peace prizes is an index to articles on notable prizes awarded for contributions towards achieving or maintaining peace. The list is organized by region and country of the sponsoring organization, but many of the prizes are open to pe ...

, the members of whom were appointed shortly after the will was approved in April 1897. Soon thereafter, the other prize-awarding organizations were designated. These were Karolinska Institute

The Karolinska Institute (KI; sv, Karolinska Institutet; sometimes known as the (Royal) Caroline Institute in English) is a research-led medical university in Solna within the Stockholm urban area of Sweden. The Karolinska Institute is consis ...

on 7 June, the Swedish Academy on 9 June, and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences on 11 June. Crawford, p. 1 The Nobel Foundation reached an agreement on guidelines for how the prizes should be awarded; and, in 1900, the Nobel Foundation's newly created statutes were promulgated by King Oscar II

Oscar II (Oscar Fredrik; 21 January 1829 – 8 December 1907) was King of Sweden from 1872 until his death in 1907 and King of Norway from 1872 to 1905.

Oscar was the son of King Oscar I and Queen Josephine. He inherited the Swedish and Norweg ...

. In 1905, the personal union between Sweden and Norway was dissolved.

Nobel Foundation

Formation of Foundation

According to his will and testament read in Stockholm on 30 December 1896, a foundation established by Alfred Nobel would reward those who serve humanity. The Nobel Prize was funded by Alfred Nobel's personal fortune. According to the official sources, Alfred Nobel bequeathed most of his fortune to the Nobel Foundation that now forms the economic base of the Nobel Prize.

The Nobel Foundation was founded as a private organization on 29 June 1900. Its function is to manage the finances and administration of the Nobel Prizes. Levinovitz, p. 14 In accordance with Nobel's will, the primary task of the foundation is to manage the fortune Nobel left.

According to his will and testament read in Stockholm on 30 December 1896, a foundation established by Alfred Nobel would reward those who serve humanity. The Nobel Prize was funded by Alfred Nobel's personal fortune. According to the official sources, Alfred Nobel bequeathed most of his fortune to the Nobel Foundation that now forms the economic base of the Nobel Prize.

The Nobel Foundation was founded as a private organization on 29 June 1900. Its function is to manage the finances and administration of the Nobel Prizes. Levinovitz, p. 14 In accordance with Nobel's will, the primary task of the foundation is to manage the fortune Nobel left. Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, h ...

and Ludvig Nobel

Ludvig Immanuel Nobel ( ; russian: Лю́двиг Эммануи́лович Нобе́ль, Ljúdvig Emmanuílovich Nobél’; sv, Ludvig Emmanuel Nobel ; 27 July 1831 – 12 April 1888) was a Swedish-Russian engineer, a noted businessman and a ...

were involved in the oil business in Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

, and according to Swedish historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

E. Bargengren, who accessed the Nobel family

The Nobel family ( , ) is a prominent Swedish and Russian family closely related to the history both of Sweden and of Russia in the 19th and 20th centuries. Its legacy includes its outstanding contributions to philanthropy and to the developme ...

archive

An archive is an accumulation of historical records or materials – in any medium – or the physical facility in which they are located.

Archives contain primary source documents that have accumulated over the course of an individual ...

, it was this "decision to allow withdrawal of Alfred's money from Baku that became the decisive factor that enabled the Nobel Prizes to be established". Another important task of the Nobel Foundation is to market the prizes internationally and to oversee informal administration related to the prizes. The foundation is not involved in the process of selecting the Nobel laureates

The Nobel Prizes ( sv, Nobelpriset, no, Nobelprisen) are awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Swedish Academy, the Karolinska Institutet, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee to individuals and organizations who make ...

. Levinovitz, p. 15Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 16 In many ways, the Nobel Foundation is similar to an investment company

An investment company is a financial institution principally engaged in holding, managing and investing securities. These companies in the United States are regulated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and must be registered under t ...

, in that it invests Nobel's money to create a solid funding base for the prizes and the administrative activities. The Nobel Foundation is exempt from all taxes in Sweden (since 1946) and from investment taxes in the United States (since 1953). Levinovitz, pp. 17–18 Since the 1980s, the foundation's investments have become more profitable and as of 31 December 2007, the assets controlled by the Nobel Foundation amounted to 3.628 billion Swedish ''kronor'' (c. US$560 million). Levinovitz, pp. 15–17

According to the statutes, the foundation consists of a board of five Swedish or Norwegian citizens, with its seat in Stockholm. The Chairman of the Board is appointed by the Swedish King in Council

The King-in-Council or the Queen-in-Council, depending on the gender of the reigning monarch, is a constitutional term in a number of states. In a general sense, it would mean the monarch exercising executive authority, usually in the form of ap ...

, with the other four members appointed by the trustee

Trustee (or the holding of a trusteeship) is a legal term which, in its broadest sense, is a synonym for anyone in a position of trust and so can refer to any individual who holds property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility to ...

s of the prize-awarding institutions. An Executive Director

Executive director is commonly the title of the chief executive officer of a non-profit organization, government agency or international organization.

The title is widely used in North American and European not-for-profit organizations, thoug ...

is chosen from among the board members, a deputy director is appointed by the King in Council, and two deputies

A legislator (also known as a deputy or lawmaker) is a person who writes and passes laws, especially someone who is a member of a legislature. Legislators are often elected by the people of the state. Legislatures may be supra-national (for e ...

are appointed by the trustees

Trustee (or the holding of a trusteeship) is a legal term which, in its broadest sense, is a synonym for anyone in a position of trust and so can refer to any individual who holds property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility to ...

. However, since 1995, all the members of the board have been chosen by the trustees, and the executive director and the deputy director appointed by the board itself. As well as the board, the Nobel Foundation is made up of the prize-awarding institutions (the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institute, the Swedish Academy, and the Norwegian Nobel Committee

The Norwegian Nobel Committee ( no, Den norske Nobelkomité) selects the recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize each year on behalf of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel's estate, based on instructions of Nobel's will.

Five members are appointed by ...

), the trustees of these institutions, and audit

An audit is an "independent examination of financial information of any entity, whether profit oriented or not, irrespective of its size or legal form when such an examination is conducted with a view to express an opinion thereon.” Auditing ...

ors.

Foundation capital and cost

The capital of the Nobel Foundation today is invested 50% inshares

In financial markets, a share is a unit of equity ownership in the capital stock of a corporation, and can refer to units of mutual funds, limited partnerships, and real estate investment trusts. Share capital refers to all of the shares of an ...

, 20% bonds and 30% other investments

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing i ...

(e.g. hedge funds

A hedge fund is a pooled investment fund that trades in relatively liquid assets and is able to make extensive use of more complex trading, portfolio-construction, and risk management techniques in an attempt to improve performance, such as ...

or real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more genera ...

). The distribution can vary by 10 percent. At the beginning of 2008, 64% of the funds were invested mainly in American and European stocks, 20% in bonds, plus 12% in real estate and hedge funds.

In 2011, the total annual cost was approximately 120 million kronor, with 50 million kronor as the prize money. Further costs to pay institutions and persons engaged in giving the prizes were 27.4 million kronor. The events during the Nobel week in Stockholm and Oslo cost 20.2 million kronor. The administration, Nobel symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

, and similar items had costs of 22.4 million kronor. The cost of the Economic Sciences

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyze ...

prize of 16.5 Million kronor is paid by the Sveriges Riksbank

Sveriges Riksbank, or simply the ''Riksbank'', is the central bank of Sweden. It is the world's oldest central bank and the fourth oldest bank in operation.

Etymology

The first part of the word ''riksbank'', ''riks'', stems from the Swedish ...

.

Inaugural Nobel prizes

Once the Nobel Foundation and its guidelines were in place, the

Once the Nobel Foundation and its guidelines were in place, the Nobel Committee

A Nobel Committee is a working body responsible for most of the work involved in selecting Nobel Prize laureates. There are five Nobel Committees, one for each Nobel Prize.

Four of these committees (for prizes in physics, chemistry, physiolo ...

s began collecting nominations for the inaugural prizes. Subsequently, they sent a list of preliminary candidates to the prize-awarding institutions.

The Nobel Committee's Physics Prize shortlist cited Wilhelm Röntgen

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (; ; 27 March 184510 February 1923) was a German mechanical engineer and physicist, who, on 8 November 1895, produced and detected electromagnetic radiation in a wavelength range known as X-rays or Röntgen rays, an achie ...

's discovery of X-ray

X-rays (or rarely, ''X-radiation'') are a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. In many languages, it is referred to as Röntgen radiation, after the German scientist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, who discovered it in 1895 and named it ' ...

s and Philipp Lenard

Philipp Eduard Anton von Lenard (; hu, Lénárd Fülöp Eduárd Antal; 7 June 1862 – 20 May 1947) was a Hungarian-born German physicist and the winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1905 for his work on cathode rays and the discovery of m ...

's work on cathode ray

Cathode rays or electron beam (e-beam) are streams of electrons observed in discharge tubes. If an evacuated glass tube is equipped with two electrodes and a voltage is applied, glass behind the positive electrode is observed to glow, due to el ...

s. The Academy of Sciences selected Röntgen for the prize.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 134Leroy

Leroy or Le Roy may refer to:

People

* Leroy (name), a given name and surname

* Leroy (musician), American musician

* Leroy (sailor), French sailor

Places United States

* Leroy, Alabama

* Le Roy, Illinois

* Le Roy, Iowa

* Le Roy, Kansas

* Le R ...

, pp. 117–118 In the last decades of the 19th century, many chemists had made significant contributions. Thus, with the Chemistry Prize, the academy "was chiefly faced with merely deciding the order in which these scientists should be awarded the prize". Levinovitz, p. 77 The academy received 20 nominations, eleven of them for Jacobus van 't Hoff. Crawford, p. 118 Van 't Hoff was awarded the prize for his contributions in chemical thermodynamics

Chemical thermodynamics is the study of the interrelation of heat and work with chemical reactions or with physical changes of state within the confines of the laws of thermodynamics. Chemical thermodynamics involves not only laboratory measureme ...

. Levinovitz, p. 81Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 205

The Swedish Academy chose the poet Sully Prudhomme

René François Armand "Sully" Prudhomme (; 16 March 1839 – 6 September 1907) was a French poet and essayist. He was the first winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1901.

Born in Paris, Prudhomme originally studied to be an engineer, bu ...

for the first Nobel Prize in Literature. A group including 42 Swedish writers, artists, and literary critics protested against this decision, having expected Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

to be awarded. Levinovitz, p. 144 Some, including Burton Feldman, have criticised this prize because they consider Prudhomme a mediocre poet. Feldman's explanation is that most of the academy members preferred Victorian literature

Victorian literature refers to English literature during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901). The 19th century is considered by some to be the Golden Age of English Literature, especially for British novels. It was in the Victorian era tha ...

and thus selected a Victorian poet.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 69 The first Physiology or Medicine Prize went to the German physiologist and microbiologist Emil von Behring

Emil von Behring (; Emil Adolf von Behring), born Emil Adolf Behring (15 March 1854 – 31 March 1917), was a German physiologist who received the 1901 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, the first one awarded in that field, for his discovery ...

. During the 1890s, von Behring developed an antitoxin

An antitoxin is an antibody with the ability to neutralize a specific toxin. Antitoxins are produced by certain animals, plants, and bacteria in response to toxin exposure. Although they are most effective in neutralizing toxins, they can also ...

to treat diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

, which until then was causing thousands of deaths each year.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, pp. 242–244Leroy

Leroy or Le Roy may refer to:

People

* Leroy (name), a given name and surname

* Leroy (musician), American musician

* Leroy (sailor), French sailor

Places United States

* Leroy, Alabama

* Le Roy, Illinois

* Le Roy, Iowa

* Le Roy, Kansas

* Le R ...

, p. 233

The first Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

went to the Swiss Jean Henri Dunant

Henry Dunant (born Jean-Henri Dunant; 8 May 182830 October 1910), also known as Henri Dunant, was a Swiss humanitarian, businessman, and social activist. He was the visionary, promoter, and co-founder of the Red Cross. In 1901, he received the ...

for his role in founding the International Red Cross Movement and initiating the Geneva Convention, and jointly given to French pacifist Frédéric Passy

Frédéric Passy (20 May 182212 June 1912) was a French economist and pacifist who was a founding member of several peace societies and the Inter-Parliamentary Union. He was also an author and politician, sitting in the Chamber of Deputies f ...

, founder of the Peace League and active with Dunant in the Alliance for Order and Civilization.

Second World War

In 1938 and 1939,Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

's Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

forbade three laureates from Germany (Richard Kuhn

Richard Johann Kuhn (; 3 December 1900 – 1 August 1967) was an Austrian-German biochemist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1938 "for his work on carotenoids and vitamins".

Biography

Early life

Kuhn was born in Vienna, Austria ...

, Adolf Friedrich Johann Butenandt, and Gerhard Domagk

Gerhard Johannes Paul Domagk (; 30 October 1895 – 24 April 1964) was a German pathologist and bacteriologist. He is credited with the discovery of sulfonamidochrysoidine (KL730) as an antibiotic for which he received the 1939 Nobel Prize in P ...

) from accepting their prizes. Levinovitz, p. 23 They were all later able to receive the diploma and medal. Wilhelm, p. 85 Even though Sweden was officially neutral during the Second World War, the prizes were awarded irregularly. In 1939, the Peace Prize was not awarded. No prize was awarded in any category from 1940 to 1942, due to the occupation of Norway by Germany

The occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany during the Second World War began on 9 April 1940 after Operation Weserübung. Conventional armed resistance to the German invasion ended on 10 June 1940, and Nazi Germany controlled Norway until t ...

. In the subsequent year, all prizes were awarded except those for literature and peace.

During the occupation of Norway, three members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee fled into exile. The remaining members escaped persecution from the Germans when the Nobel Foundation stated that the committee building in Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

was Swedish property. Thus it was a safe haven from the German military, which was not at war with Sweden. Abrams, p. 23 These members kept the work of the committee going, but did not award any prizes. In 1944, the Nobel Foundation, together with the three members in exile, made sure that nominations were submitted for the Peace Prize and that the prize could be awarded once again.

Prize in Economic Sciences

Sveriges Riksbank

Sveriges Riksbank, or simply the ''Riksbank'', is the central bank of Sweden. It is the world's oldest central bank and the fourth oldest bank in operation.

Etymology

The first part of the word ''riksbank'', ''riks'', stems from the Swedish ...

celebrated its 300th anniversary by donating a large sum of money to the Nobel Foundation to be used to set up a prize in honour of Alfred Nobel. The following year, the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel ( sv, Sveriges riksbanks pris i ekonomisk vetenskap till Alfred Nobels minne), is an economics award administered ...

was awarded for the first time. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences became responsible for selecting laureates. The first laureates for the Economics Prize were Jan Tinbergen

Jan Tinbergen (; ; 12 April 19039 June 1994) was a Dutch economist who was awarded the first Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1969, which he shared with Ragnar Frisch for having developed and applied dynamic models for the analysis ...

and Ragnar Frisch

Ragnar Anton Kittil Frisch (3 March 1895 – 31 January 1973) was an influential Norwegian economist known for being one of the major contributors to establishing economics as a quantitative and statistically informed science in the early 20th c ...

"for having developed and applied dynamic models for the analysis of economic processes".Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 343 Levinovitz, p. 207 The board of the Nobel Foundation decided that after this addition, it would allow no further new prizes. Levinovitz, p. 20

Award process

The award process is similar for all of the Nobel Prizes, the main difference being who can make nominations for each of them.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, pp. 16–17

Nominations

Nomination forms are sent by the Nobel Committee to about 3,000 individuals, usually in September the year before the prizes are awarded. These individuals are generally prominent academics working in a relevant area. Regarding the Peace Prize, inquiries are also sent to governments, former Peace Prize laureates, and current or former members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. The deadline for the return of the nomination forms is 31 January of the year of the award. Levinovitz, p. 26 The Nobel Committee nominates about 300 potential laureates from these forms and additional names. Abrams, p. 15 The nominees are not publicly named, nor are they told that they are being considered for the prize. All nomination records for a prize are sealed for 50 years from the awarding of the prize.Selection

The Nobel Committee then prepares a report reflecting the advice of experts in the relevant fields. This, along with the list of preliminary candidates, is submitted to the prize-awarding institutions.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 52 There are four awarding institutions for the six prizes awarded:

* Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences – Chemistry; Physics; Economics

*Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute

The Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute is a body at Karolinska Institute which awards the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. It is headquartered in the Nobel Forum on the grounds of the Karolinska Institute campus. Originally the Nobel ...

– Physiology / Medicine

*Swedish Academy

The Swedish Academy ( sv, Svenska Akademien), founded in 1786 by King Gustav III, is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. Its 18 members, who are elected for life, comprise the highest Swedish language authority. Outside Scandinavia, it is b ...

– Literature

*Norwegian Nobel Committee

The Norwegian Nobel Committee ( no, Den norske Nobelkomité) selects the recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize each year on behalf of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel's estate, based on instructions of Nobel's will.

Five members are appointed by ...

– Peace

The institutions meet to choose the laureate or laureates in each field by a majority vote. Their decision, which cannot be appealed, is announced immediately after the vote. Levinovitz, pp. 25–28 A maximum of three laureates and two different works may be selected per award. Except for the Peace Prize, which can be awarded to institutions, the awards can only be given to individuals. Abrams, p. 8

Posthumous nominations

Although posthumous nominations are not presently permitted, individuals who died in the months between their nomination and the decision of the prize committee were originally eligible to receive the prize. This has occurred twice: the 1931 Literature Prize awarded toErik Axel Karlfeldt

Erik Axel Karlfeldt (20 July 1864 – 8 April 1931) was a Swedish poet whose highly symbolist poetry masquerading as regionalism was popular and won him the 1931 Nobel Prize in Literature posthumously after he had been nominated by Nathan Söder ...

, and the 1961 Peace Prize awarded to UN Secretary General

The secretary-general of the United Nations (UNSG or SG) is the chief administrative officer of the United Nations and head of the United Nations Secretariat, one of the six principal organs of the United Nations.

The role of the secretary-ge ...

Dag Hammarskjöld

Dag Hjalmar Agne Carl Hammarskjöld ( , ; 29 July 1905 – 18 September 1961) was a Swedish economist and diplomat who served as the second Secretary-General of the United Nations from April 1953 until his death in a plane crash in September 196 ...

. Since 1974, laureates must be thought alive at the time of the October announcement. There has been one laureate, William Vickrey

William Spencer Vickrey (21 June 1914 – 11 October 1996) was a Canadian-American professor of economics and Nobel Laureate. Vickrey was awarded the 1996 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with James Mirrlees for their research into the e ...

, who in 1996 died after the prize (in Economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analy ...

) was announced but before it could be presented. Abrams, p. 9 On 3 October 2011, the laureates for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine ( sv, Nobelpriset i fysiologi eller medicin) is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute, Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or ...

were announced; however, the committee was not aware that one of the laureates, Ralph M. Steinman, had died three days earlier. The committee was debating about Steinman's prize, since the rule is that the prize is not awarded posthumously. The committee later decided that as the decision to award Steinman the prize "was made in good faith", it would remain unchanged.

Recognition time lag

Nobel's will provided for prizes to be awarded in recognition of discoveries made "during the preceding year". Early on, the awards usually recognised recent discoveries. However, some of those early discoveries were later discredited. For example,Johannes Fibiger

Johannes Andreas Grib Fibiger (23 April 1867 – 30 January 1928) was a Danish physician and professor of anatomical pathology at the University of Copenhagen. He was the recipient of the 1926 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine "for his disco ...

was awarded the 1926 Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, according ...

for his purported discovery of a parasite that caused cancer. Levinovitz, p. 125 To avoid repeating this embarrassment, the awards increasingly recognised scientific discoveries that had withstood the test of time. Abrams, p. 25 According to Ralf Pettersson, former chairman of the Nobel Prize Committee for Physiology or Medicine, "the criterion 'the previous year' is interpreted by the Nobel Assembly as the year when the full impact of the discovery has become evident."

The interval between the award and the accomplishment it recognises varies from discipline to discipline. The Literature Prize is typically awarded to recognise a cumulative lifetime body of work rather than a single achievement. The Peace Prize can also be awarded for a lifetime body of work. For example, 2008 laureate

The interval between the award and the accomplishment it recognises varies from discipline to discipline. The Literature Prize is typically awarded to recognise a cumulative lifetime body of work rather than a single achievement. The Peace Prize can also be awarded for a lifetime body of work. For example, 2008 laureate Martti Ahtisaari

Martti Oiva Kalevi Ahtisaari (; born 23 June 1937) is a Finnish politician, the tenth president of Finland (1994–2000), a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and a United Nations diplomat and mediator noted for his international peace work.

Ahtisaa ...

was awarded for his work to resolve international conflicts. However, they can also be awarded for specific recent events. For instance, Kofi Annan

Kofi Atta Annan (; 8 April 193818 August 2018) was a Ghanaian diplomat who served as the seventh secretary-general of the United Nations from 1997 to 2006. Annan and the UN were the co-recipients of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize. He was the found ...

was awarded the 2001 Peace Prize just four years after becoming the Secretary-General of the United Nations. Abrams, p. 330 Similarly Yasser Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, محمد ياسر عبد الرحمن عبد الرؤوف عرفات القدوة الحسيني, Mu ...

, Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin (; he, יִצְחָק רַבִּין, ; 1 March 1922 – 4 November 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the fifth Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974–77, and from 1992 until ...

, and Shimon Peres

Shimon Peres (; he, שמעון פרס ; born Szymon Perski; 2 August 1923 – 28 September 2016) was an Israeli politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Israel from 1984 to 1986 and from 1995 to 1996 and as the ninth president of ...

received the 1994 award, about a year after they successfully concluded the Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords are a pair of agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): the Oslo I Accord, signed in Washington, D.C., in 1993;

. Abrams, p. 27 The most recent controverswas caused by awarding the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize to

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

in his first year as US president.

Awards for physics, chemistry, and medicine are typically awarded once the achievement has been widely accepted. Sometimes, this takes decades – for example, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (; ) (19 October 1910 – 21 August 1995) was an Indian-American theoretical physicist who spent his professional life in the United States. He shared the 1983 Nobel Prize for Physics with William A. Fowler for ".. ...

shared the 1983 Physics Prize for his 1930s work on stellar structure and evolution. Not all scientists live long enough for their work to be recognised. Some discoveries can never be considered for a prize if their impact is realised after the discoverers have died.

Award ceremonies

Except for the Peace Prize, the Nobel Prizes are presented in Stockholm, Sweden, at the annual Prize Award Ceremony on 10 December, the anniversary of Nobel's death. The recipients' lectures are normally held in the days prior to the award ceremony. The Peace Prize and its recipients' lectures are presented at the annual Prize Award Ceremony in Oslo, Norway, usually on 10 December. The award ceremonies and the associated banquets are typically major international events. The Prizes awarded in Sweden's ceremonies are held at theStockholm Concert Hall

The Stockholm Concert Hall ( sv, Stockholms konserthus) is the main hall for orchestral music in Stockholm, Sweden.

With a design by Ivar Tengbom chosen in competition, inaugurated in 1926, the Hall is home to the Royal Stockholm Philharmoni ...

, with the Nobel banquet following immediately at Stockholm City Hall

Stockholm City Hall ( sv, Stockholms stadshus, ''Stadshuset'' locally) is the seat of Stockholm Municipality in Stockholm, Sweden. It stands on the eastern tip of Kungsholmen island, next to Riddarfjärden's northern shore and facing the isla ...

. The Nobel Peace Prize ceremony has been held at the Norwegian Nobel Institute

The Norwegian Nobel Institute ( no, Det Norske Nobelinstitutt) is located in Oslo, Norway. The institute is located at Henrik Ibsen Street 51 in the center of the city. It is situated just by the side of the Royal Palace.

History

The institute ...

(1905–1946), at the auditorium

An auditorium is a room built to enable an audience to hear and watch performances. For movie theatres, the number of auditoria (or auditoriums) is expressed as the number of screens. Auditoria can be found in entertainment venues, communit ...

of the University of Oslo

The University of Oslo ( no, Universitetet i Oslo; la, Universitas Osloensis) is a public research university located in Oslo, Norway. It is the highest ranked and oldest university in Norway. It is consistently ranked among the top univers ...

(1947–1989), and at Oslo City Hall

Oslo City Hall ( no, Oslo rådhus) is a municipal building in Oslo, the capital of Norway. It houses the city council, the city's administration and various other municipal organisations. The building as it stands today was constructed between ...

(1990–present). Levinovitz, pp. 21–23

The highlight of the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony in Stockholm occurs when each Nobel laureate steps forward to receive the prize from the hands of the King of Sweden

The monarchy of Sweden is the monarchical head of state of Sweden,See the #IOG, Instrument of Government, Chapter 1, Article 5. which is a constitutional monarchy, constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system.Parliamentary ...

. In Oslo, the chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee presents the Nobel Peace Prize in the presence of the King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty kingd ...

and the Norwegian royal family. At first, King Oscar II

Oscar II (Oscar Fredrik; 21 January 1829 – 8 December 1907) was King of Sweden from 1872 until his death in 1907 and King of Norway from 1872 to 1905.

Oscar was the son of King Oscar I and Queen Josephine. He inherited the Swedish and Norwe ...

did not approve of awarding grand prizes to foreigners. It is said that he changed his mind once his attention had been drawn to the publicity value of the prizes for Sweden.

Nobel Banquet

After the award ceremony in Sweden, a banquet is held in the Blue Hall at the

After the award ceremony in Sweden, a banquet is held in the Blue Hall at the Stockholm City Hall

Stockholm City Hall ( sv, Stockholms stadshus, ''Stadshuset'' locally) is the seat of Stockholm Municipality in Stockholm, Sweden. It stands on the eastern tip of Kungsholmen island, next to Riddarfjärden's northern shore and facing the isla ...

, which is attended by the Swedish Royal Family

The Swedish royal family ( sv, Svenska kungafamiljen) since 1818 has consisted of members of the Swedish Royal House of Bernadotte, closely related to the King of Sweden. Today those who are recognized by the government are entitled to royal tit ...

and around 1,300 guests. The Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

banquet is held in Norway at the Oslo Grand Hotel after the award ceremony. Apart from the laureate, guests include the president of the Storting

The Storting ( no, Stortinget ) (lit. the Great Thing) is the supreme legislature of Norway, established in 1814 by the Constitution of Norway. It is located in Oslo. The unicameral parliament has 169 members and is elected every four years ...

, on occasion the Swedish prime minister, and, since 2006, the King and Queen of Norway. In total, about 250 guests attend.

Nobel lecture

According to the statutes of the Nobel Foundation, each laureate is required to give a public lecture on a subject related to the topic of their prize. The Nobel lecture as a rhetorical genre took decades to reach its current format. These lectures normally occur during Nobel Week (the week leading up to the award ceremony and banquet, which begins with the laureates arriving in Stockholm and normally ends with the Nobel banquet), but this is not mandatory. The laureate is only obliged to give the lecture within six months of receiving the prize, but some have happened even later. For example, US PresidentTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

received the Peace Prize in 1906 but gave his lecture in 1910, after his term in office. Abrams, pp. 18–19 The lectures are organized by the same association which selected the laureates.

Prizes

Medals

The Nobel Foundation announced on 30 May 2012 that it had awarded the contract for the production of the five (Swedish) Nobel Prize medals to Svenska Medalj AB. Between 1902 and 2010, the Nobel Prize medals were minted by Myntverket (the Swedish Mint), Sweden's oldest company, which ceased operations in 2011 after 107 years. In 2011, the Mint of Norway, located in Kongsberg, made the medals. The Nobel Prize medals are registered trademarks of the Nobel Foundation. Each medal features an image of Alfred Nobel in left profile on theobverse

Obverse and its opposite, reverse, refer to the two flat faces of coins and some other two-sided objects, including paper money, flags, seals, medals, drawings, old master prints and other works of art, and printed fabrics. In this usage, ...

. The medals for physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, and literature have identical obverses, showing the image of Alfred Nobel and the years of his birth and death. Nobel's portrait also appears on the obverse of the Peace Prize medal and the medal for the Economics Prize, but with a slightly different design. For instance, the laureate's name is engraved on the rim of the Economics medal.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 2 The image on the reverse of a medal varies according to the institution awarding the prize. The reverse sides of the medals for chemistry and physics share the same design."Nobel Prize for Chemistry. Front and back images of the medal. 1954""Source: Photo by Eric Arnold. Ava Helen and

Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific top ...

Papers. Honors and Awards, 1954h2.1", "All Documents and Media: Pictures and Illustrations", ''Linus Pauling and The Nature of the Chemical Bond: A Documentary History'', the Valley Library

The Valley Library is the primary library of Oregon State University and is located at the school's main campus in Corvallis in the U.S. state of Oregon. Established in 1887, the library was placed in its own building for the first time in 1918, ...

, Oregon State University

Oregon State University (OSU) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant, research university in Corvallis, Oregon. OSU offers more than 200 undergraduate-degree programs along with a variety of graduate and doctoral degree ...

. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

green gold

Electrum is a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver, with trace amounts of copper and other metals. Its color ranges from pale to bright yellow, depending on the proportions of gold and silver. It has been produced artificially, and ...

plated with 24 carat gold. The weight of each medal varies with the value of gold, but averages about for each medal. The diameter is and the thickness varies between and . Because of the high value of their gold content and tendency to be on public display, Nobel medals are subject to medal theft. During World War II, the medals of German scientists Max von Laue

Max Theodor Felix von Laue (; 9 October 1879 – 24 April 1960) was a German physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 for his discovery of the diffraction of X-rays by crystals.

In addition to his scientific endeavors with con ...

and James Franck

James Franck (; 26 August 1882 – 21 May 1964) was a German physicist who won the 1925 Nobel Prize for Physics with Gustav Hertz "for their discovery of the laws governing the impact of an electron upon an atom". He completed his doctorate i ...

were sent to Copenhagen for safekeeping. When Germany invaded Denmark, Hungarian chemist (and Nobel laureate himself) George de Hevesy

George Charles de Hevesy (born György Bischitz; hu, Hevesy György Károly; german: Georg Karl von Hevesy; 1 August 1885 – 5 July 1966) was a Hungarian radiochemist and Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate, recognized in 1943 for his key rol ...

dissolved them in aqua regia (nitro-hydrochloric acid), to prevent confiscation by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and to prevent legal problems for the holders. After the war, the gold was recovered from solution, and the medals re-cast.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 397

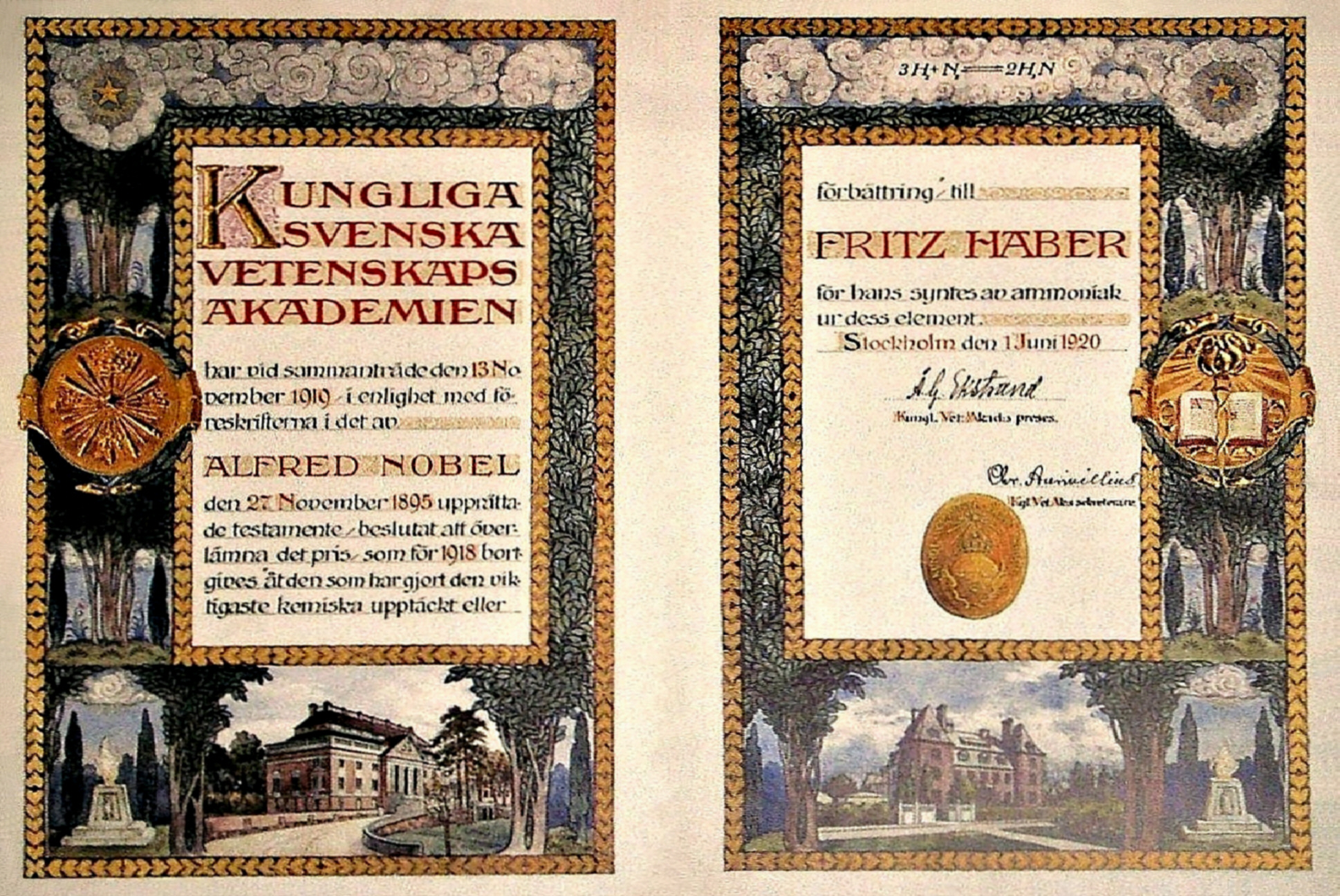

Diplomas

Nobel laureates receive a diploma directly from the hands of the King of Sweden, or in the case of the peace prize, the chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. Each diploma is uniquely designed by the prize-awarding institutions for the laureates that receive them. The diploma contains a picture and text in Swedish which states the name of the laureate and normally a citation of why they received the prize. None of the Nobel Peace Prize laureates has ever had a citation on their diplomas. Abrams, p. 18Award money

The laureates are given a sum of money when they receive their prizes, in the form of a document confirming the amount awarded. The amount of prize money depends upon how much money the Nobel Foundation can award each year. The purse has increased since the 1980s, when the prize money was 880,000 SEK per prize (c. 2.6 million SEK altogether, US$350,000 today). In 2009, the monetary award was 10 million SEK (US$1.4 million). In June 2012, it was lowered to 8 million SEK. If two laureates share the prize in a category, the award grant is divided equally between the recipients. If there are three, the awarding committee has the option of dividing the grant equally, or awarding one-half to one recipient and one-quarter to each of the others. Abrams, pp. 8–10 It is common for recipients to donate prize money to benefit scientific, cultural, or humanitarian causes.Controversies and criticisms

Controversial recipients

Among other criticisms, the Nobel Committees have been accused of having a political agenda, and of omitting more deserving candidates. They have also been accused of

Among other criticisms, the Nobel Committees have been accused of having a political agenda, and of omitting more deserving candidates. They have also been accused of Eurocentrism

Eurocentrism (also Eurocentricity or Western-centrism)

is a worldview that is centered on Western civilization or a biased view that favors it over non-Western civilizations. The exact scope of Eurocentrism varies from the entire Western worl ...

, especially for the Literature Prize. Abrams, p. xivFeldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 65

;Peace Prize

Among the most criticised Nobel Peace Prizes was the one awarded to Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the preside ...

and Lê Đức Thọ

Lê Đức Thọ (; 14 October 1911 – 13 October 1990), born Phan Đình Khải in Nam Dinh Province, was a Vietnamese revolutionary, general, diplomat, and politician. He was the first Asian to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, jointly with ...

. This led to the resignation of two Norwegian Nobel Committee members. Kissinger and Thọ were awarded the prize for negotiating a ceasefire between North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

and the United States in January 1973. However, when the award was announced, both sides were still engaging in hostilities. Abrams, p. 219 Critics sympathetic to the North announced that Kissinger was not a peace-maker but the opposite, responsible for widening the war. Those hostile to the North and what they considered its deceptive practices during negotiations were deprived of a chance to criticise Lê Đức Thọ, as he declined the award.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, p. 315 Abrams, p. 315 The satirist and musician Tom Lehrer

Thomas Andrew Lehrer (; born April 9, 1928) is an American former musician, singer-songwriter, satirist, and mathematician, having lectured on mathematics and musical theater. He is best known for the pithy and humorous songs that he recorded i ...

has remarked that "political satire became obsolete when Henry Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize."

Yasser Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, محمد ياسر عبد الرحمن عبد الرؤوف عرفات القدوة الحسيني, Mu ...

, Shimon Peres

Shimon Peres (; he, שמעון פרס ; born Szymon Perski; 2 August 1923 – 28 September 2016) was an Israeli politician who served as the eighth prime minister of Israel from 1984 to 1986 and from 1995 to 1996 and as the ninth president of ...

, and Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin (; he, יִצְחָק רַבִּין, ; 1 March 1922 – 4 November 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the fifth Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974–77, and from 1992 until ...

received the Peace Prize in 1994 for their efforts in making peace between Israel and Palestine. Levinovitz, p. 183 Immediately after the award was announced, one of the five Norwegian Nobel Committee members denounced Arafat as a terrorist and resigned.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, pp. 15–16 Additional misgivings about Arafat were widely expressed in various newspapers. Abrams, pp. 302–306

Another controversial Peace Prize was that awarded to Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

in 2009. Nominations had closed only eleven days after Obama took office as President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

, but the actual evaluation occurred over the next eight months. Obama himself stated that he did not feel deserving of the award, or worthy of the company in which it would place him. Past Peace Prize laureates were divided, some saying that Obama deserved the award, and others saying he had not secured the achievements to yet merit such an accolade. Obama's award, along with the previous Peace Prizes for Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 19 ...

and Al Gore, also prompted accusations of a liberal bias.

;Literature Prize

The award of the 2004 Literature Prize to Elfriede Jelinek

Elfriede Jelinek (; born 20 October 1946) is an Austrian playwright and novelist. She is one of the most decorated authors writing in German today and was awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Literature for her "musical flow of voices and counter-vo ...

drew a protest from a member of the Swedish Academy, Knut Ahnlund. Ahnlund resigned, alleging that the selection of Jelinek had caused "irreparable damage to all progressive forces, it has also confused the general view of literature as an art". He alleged that Jelinek's works were "a mass of text shovelled together without artistic structure". The 2009 Literature Prize to Herta Müller

Herta Müller (; born 17 August 1953) is a Romanian-born German novelist, poet, essayist and recipient of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature. Born in Nițchidorf (german: Nitzkydorf, link=no), Timiș County in Romania, her native language is ...

also generated criticism. According to ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'', many US literary critics and professors were ignorant of her work. This made those critics feel the prizes were too Eurocentric. The 2019 Literature Prize to Peter Handke

Peter Handke (; born 6 December 1942) is an Austrian novelist, playwright, translator, poet, film director, and screenwriter. He was awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize in Literature "for an influential work that with linguistic ingenuity has explored ...

received heavy criticisms from various authors, such as Salman Rushdie

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie (; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British-American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern and W ...

and Hari Kunzru

Hari Mohan Nath Kunzru (born 1969) is a British novelist and journalist. He is the author of the novels ''The Impressionist'', ''Transmission'', ''My Revolutions'', '' Gods Without Men'', ''White Tears''David Robinson"Interview: Hari Kunzru, au ...

, and was condemned by the governments of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of south and southeast Europe, located in the Balkans. Bosnia and ...

, Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Eur ...

, and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

, due to his history of Bosnian genocide denial

Bosnian genocide denial is an act of denying that the systematic Bosnian genocide against the Bosniak Muslim population of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as planned and perpetrated in line with official and academic narratives defined and expressed by ...

ism and his support for Slobodan Milošević

Slobodan Milošević (, ; 20 August 1941 – 11 March 2006) was a Yugoslav and Serbian politician who was the president of Serbia within Yugoslavia from 1989 to 1997 (originally the Socialist Republic of Serbia, a constituent republic of ...

.

;Science prizes

In 1949, the neurologist António Egas Moniz

António Caetano de Abreu Freire Egas Moniz (29 November 1874 – 13 December 1955), known as Egas Moniz (), was a Portuguese neurologist and the developer of cerebral angiography. He is regarded as one of the founders of modern psychosurgery, h ...

received the Physiology or Medicine Prize for his development of the prefrontal leucotomy. The previous year, Dr. Walter Freeman had developed a version of the procedure which was faster and easier to carry out. Due in part to the publicity surrounding the original procedure, Freeman's procedure was prescribed without due consideration or regard for modern medical ethics

Medical ethics is an applied branch of ethics which analyzes the practice of clinical medicine and related scientific research. Medical ethics is based on a set of values that professionals can refer to in the case of any confusion or conflict. T ...

. Endorsed by such influential publications as ''The New England Journal of Medicine

''The New England Journal of Medicine'' (''NEJM'') is a weekly medical journal published by the Massachusetts Medical Society. It is among the most prestigious peer-reviewed medical journals as well as the oldest continuously published one.

Hist ...

'', leucotomy or "lobotomy" became so popular that about 5,000 lobotomies were performed in the United States in the three years immediately following Moniz's receipt of the Prize.Feldman

Feldman is a German and Ashkenazi Jewish surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Academics

* Arthur Feldman (born 1949), American cardiologist

* David B. Feldman, American psychologist

* David Feldman (historian), American historian

* ...

, pp. 286–289

Overlooked achievements

Although

Although Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure ...

, an icon of nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

in the 20th century, was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

five times, in 1937, 1938, 1939, 1947, and a few days before he was assassinated on 30 January 1948, he was never awarded the prize. Levinovitz, pp. 181–186

In 1948, the year of Gandhi's death, the Norwegian Nobel Committee decided to make no award that year on the grounds that "there was no suitable living candidate". Abrams, pp. 147–148

In 1989, this omission was publicly regretted, when the 14th Dalai Lama

The 14th Dalai Lama (spiritual name Jetsun Jamphel Ngawang Lobsang Yeshe Tenzin Gyatso, known as Tenzin Gyatso (Tibetan: བསྟན་འཛིན་རྒྱ་མཚོ་, Wylie: ''bsTan-'dzin rgya-mtsho''); né Lhamo Thondup), known as ...

was awarded the Peace Prize, the chairman of the committee said that it was "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi".

Geir Lundestad

Geir Lundestad (born January 17, 1945) is a Norwegian historian, who until 2014 served as the director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute when Olav Njølstad took over. In this capacity, he also served as the secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Commit ...

, 2006 Secretary of Norwegian Nobel Committee, said,

Other high-profile individuals with widely recognised contributions to peace have been overlooked. In 2009, an article in ''Foreign Policy

A state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterally or through ...

'' magazine identified seven people who "never won the prize, but should have". The list consisted of Gandhi, Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

, Václav Havel

Václav Havel (; 5 October 193618 December 2011) was a Czech statesman, author, poet, playwright, and former dissident. Havel served as the last president of Czechoslovakia from 1989 until the dissolution of Czechoslovakia in 1992 and the ...

, Ken Saro-Wiwa

Kenule Beeson "Ken" Saro-Wiwa (10 October 1941 – 10 November 1995) was a Nigerian writer, television producer, and environmental activist. Ken Saro-Wiwa was a member of the Ogoni people, an ethnic minority in Nigeria whose homeland, Ogonila ...

, Sari Nusseibeh

Sari Nusseibeh ( ar, سري نسيبة) (born in 1949) is a Palestinian professor of philosophy and former president of the Al-Quds University in Jerusalem. Until December 2002, he was the representative of the Palestinian National Authority in ...

, Corazon Aquino

Maria Corazon "Cory" Sumulong Cojuangco-Aquino (; ; January 25, 1933 – August 1, 2009) was a Filipina politician who served as the 11th president of the Philippines from 1986 to 1992. She was the most prominent figure of the 1986 People ...

, and Liu Xiaobo

Liu Xiaobo (; 28 December 1955 – 13 July 2017) was a Chinese writer, literary critic, human rights activist, philosopher and Nobel Peace Prize laureate who called for political reforms and was involved in campaigns to end communist on ...

. Liu Xiaobo would go on to win the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize