Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a

viral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses in which fever and hemorrhage are caused by a viral infection. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families ''Filoviridae'', ''Flavi ...

in humans and other

primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

s, caused by

ebolavirus

The genus ''Ebolavirus'' (- or ; - or ) is a virological taxon included in the family ''Filoviridae'' (filament-shaped viruses), order ''Mononegavirales''. The members of this genus are called ebolaviruses, and encode their genome in the form ...

es.

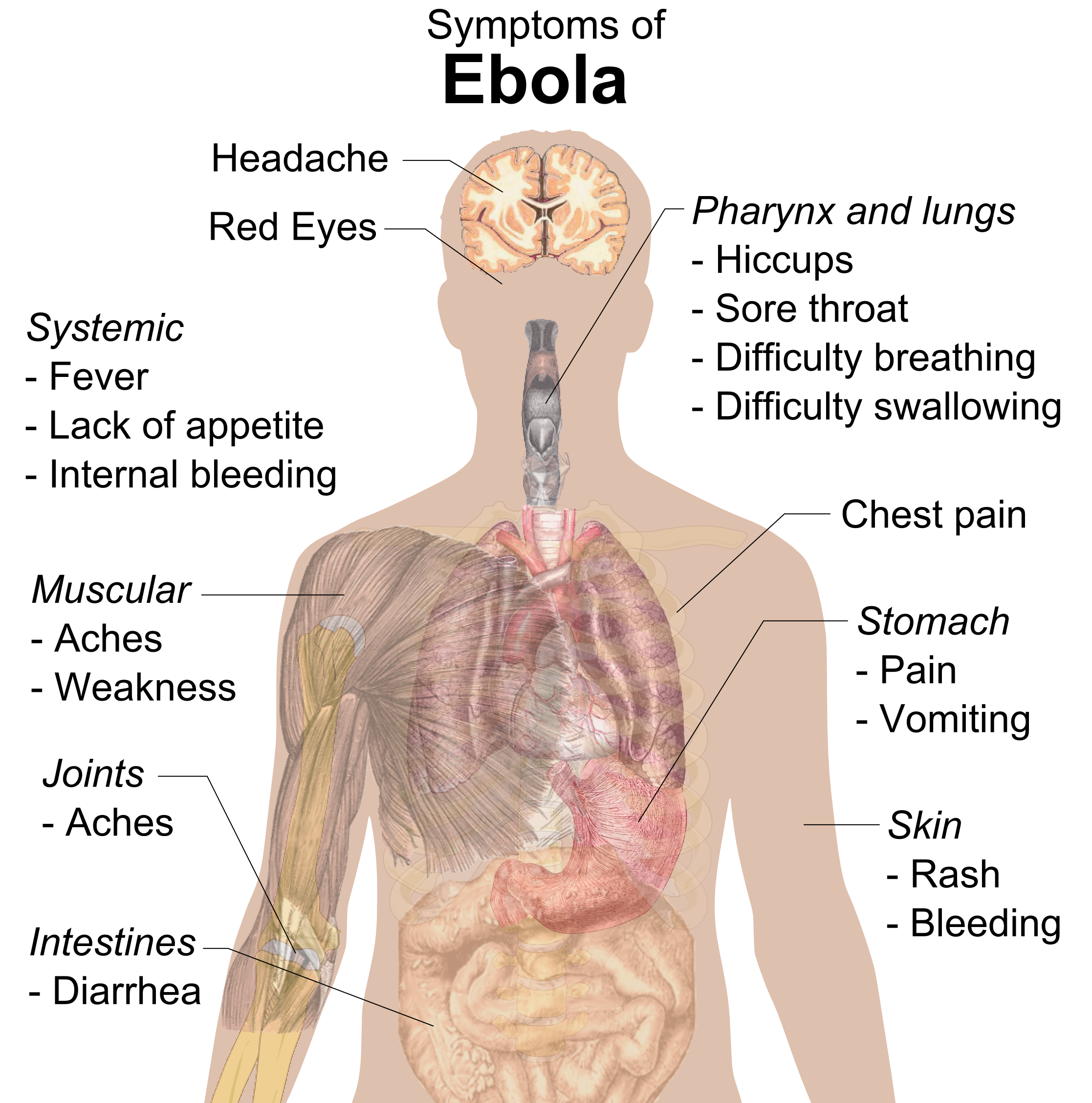

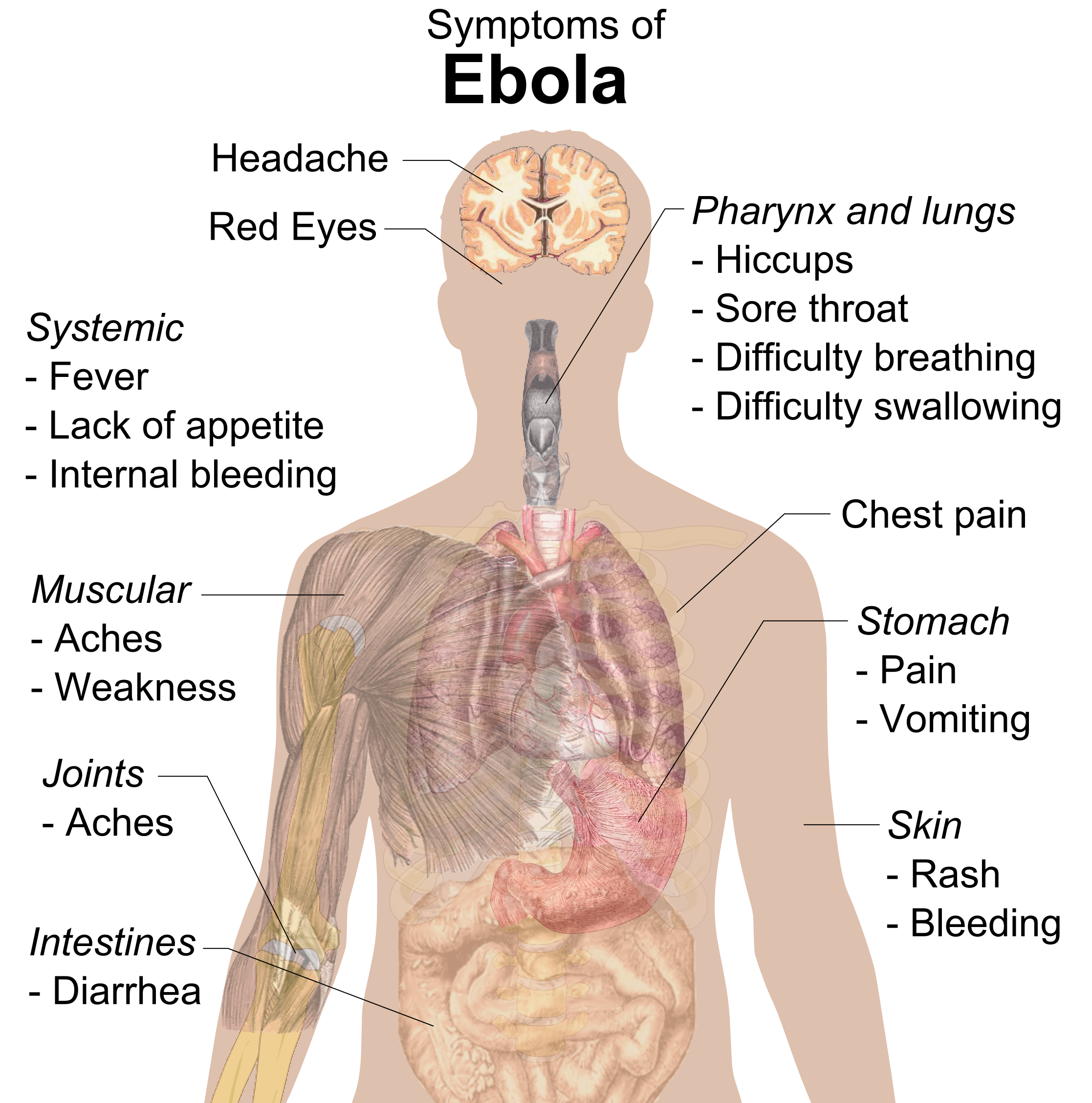

[ Symptoms typically start anywhere between two days and three weeks after becoming infected with the virus. The first symptoms are usually ]fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a body temperature, temperature above the human body temperature, normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, set point. There is not a single ...

, sore throat

Sore throat, also known as throat pain, is pain or irritation of the throat. Usually, causes of sore throat include

* viral infections

* group A streptococcal infection (GAS) bacterial infection

* pharyngitis (inflammation of the throat)

* tonsi ...

, muscle pain

Myalgia (also called muscle pain and muscle ache in layman's terms) is the medical term for muscle pain. Myalgia is a symptom of many diseases. The most common cause of acute myalgia is the overuse of a muscle or group of muscles; another likel ...

, and headache

Headache is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of depression in those with severe headaches.

Headaches can occur as a result ...

s.[ These are usually followed by ]vomiting

Vomiting (also known as emesis and throwing up) is the involuntary, forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the Human nose, nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like Food-poisoning, foo ...

, diarrhoea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin wi ...

, rash

A rash is a change of the human skin which affects its color, appearance, or texture.

A rash may be localized in one part of the body, or affect all the skin. Rashes may cause the skin to change color, itch, become warm, bumpy, chapped, dry, cr ...

and decreased liver

The liver is a major Organ (anatomy), organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for ...

and kidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blood ...

function,[ at which point, some people begin to bleed both internally and externally.][ Death is often due to shock from fluid loss, and typically occurs between six and 16 days after the first symptoms appear.]body fluid

Body fluids, bodily fluids, or biofluids, sometimes body liquids, are liquids within the human body. In lean healthy adult men, the total body water is about 60% (60–67%) of the total Human body weight, body weight; it is usually slightly lower ...

s, such as blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the c ...

from infected humans or other animals,[ or from contact with items that have recently been contaminated with infected body fluids.][ There have been no documented cases, either in nature or under laboratory conditions, of the disease spreading through the air between humans or other ]primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

s.semen

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is an organic bodily fluid created to contain spermatozoa. It is secreted by the gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphroditic animals and can fertilize the female ovum. Semen i ...

or breast milk

Breast milk (sometimes spelled as breastmilk) or mother's milk is milk produced by mammary glands located in the breast of a human female. Breast milk is the primary source of nutrition for newborns, containing fat, protein, carbohydrates ( lacto ...

may continue to carry the virus for anywhere between several weeks to several months.Fruit bat

Megabats constitute the family Pteropodidae of the order Chiroptera (bats). They are also called fruit bats, Old World fruit bats, or—especially the genera ''Acerodon'' and ''Pteropus''—flying foxes. They are the only member of the sup ...

s are believed to be the normal carrier in nature; they are able to spread the virus without being affected by it.[ The symptoms of Ebola may resemble those of several other diseases, including ]malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

, meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, headache, and neck stiffness. Other symptoms include confusion or ...

and other viral hemorrhagic fevers.[ Diagnosis is confirmed by testing blood samples for the presence of viral ]RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

, viral antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

or the virus itself.[ including rapid detection, ]contact tracing

In public health, contact tracing is the process of identifying persons who may have been exposed to an infected person ("contacts") and subsequent collection of further data to assess transmission. By tracing the contacts of infected individua ...

of those exposed, quick access to laboratory services, care for those infected, and proper disposal of the dead through cremation

Cremation is a method of Disposal of human corpses, final disposition of a Cadaver, dead body through Combustion, burning.

Cremation may serve as a funeral or post-funeral rite and as an alternative to burial. In some countries, including India ...

or burial.[ Samples of body fluids and tissues from people with the disease should be handled with extreme caution.][ Prevention measures include wearing proper protective clothing and ]washing hands

Hand washing (or handwashing), also known as hand hygiene, is the act of cleaning one's hands with soap or handwash and water to remove viruses/bacteria/microorganisms, dirt, grease, or other harmful and unwanted substances stuck to the hand ...

when around a person with the disease,[ and limiting the spread of the disease from infected animals to humans – by wearing protective clothing while handling potentially infected ]bushmeat

Bushmeat is meat from wildlife species that are hunted for human consumption, most often referring to the meat of game in Africa. Bushmeat represents

a primary source of animal protein and a cash-earning commodity for inhabitants of humid tropi ...

, and by cooking bushmeat thoroughly before eating it.[ An ]Ebola vaccine

Ebola vaccines are vaccines either approved or in development to prevent Ebola. As of 2022, there are only vaccines against the Zaire ebolavirus. The first vaccine to be approved in the United States was rVSV-ZEBOV in December 2019. It had been ...

was approved in the United States in December 2019.atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab

Atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab, sold under the brand name Inmazeb, is a fixed-dose combination of three monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of '' Zaire ebolavirus'' (Ebola virus). It contains atoltivimab, maftivimab, and odesivimab-eb ...

and ansuvimab

Ansuvimab, sold under the brand name Ebanga, is a monoclonal antibody medication for the treatment of ''Zaire ebolavirus'' (Ebolavirus) infection.

The most common symptoms include fever, tachycardia (fast heart rate), diarrhea, vomiting, hypote ...

) are associated with improved outcomes.[ These include ]oral rehydration therapy

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is a type of fluid replacement used to prevent and treat dehydration, especially due to diarrhea. It involves drinking water with modest amounts of sugar and salts, specifically sodium and potassium. Oral rehydrati ...

(drinking slightly sweetened and salty water) or giving intravenous fluids

Intravenous therapy (abbreviated as IV therapy) is a medical technique that administers fluids, medications and nutrients directly into a person's vein. The intravenous route of administration is commonly used for rehydration or to provide nutrie ...

, and treating symptoms.[ In October 2020, Atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab (Inmazeb) was approved for medical use in the United States to treat the disease caused by ''Zaire ebolavirus''.]

History and name

The disease was first identified in 1976, in two simultaneous outbreaks: one in Nzara

Nzara is a town in Western Equatoria State. It lies to the northwest of Yambio by road, and is 25 km (15m) from the border with the DR Congo.

Nzara was industrial center of the Azande Scheme also known as, Equatoria Project Scheme during ...

(a town in South Sudan

South Sudan (; din, Paguot Thudän), officially the Republic of South Sudan ( din, Paankɔc Cuëny Thudän), is a landlocked country in East Africa. It is bordered by Ethiopia, Sudan, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the C ...

) and the other in Yambuku

Yambuku is a small village in Mongala Province in northern Democratic Republic of the Congo. It was the center of the first documented outbreak of Ebola virus disease, in 1976, with the World Health Organization identifying a man from Yambuku as ...

(the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

), a village near the Ebola River

The Ebola River ( or ), also commonly known by its indigenous name Legbala, is the headstream of the Mongala River, a tributary of the Congo River, in northern Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is roughly in length.

The name ''Ebola'' is a F ...

, from which the disease takes its name.Ebola outbreaks

This list of Ebola outbreaks records the known occurrences of Ebola virus disease, a highly infectious and acutely lethal Virus, viral disease that has afflicted humans and animals primarily in equatorial Africa. The pathogens responsible for ...

occur intermittently in tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

.[ Between 1976 and 2012, according to the ]World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

, there were 24 outbreaks of Ebola resulting in a total of 2,387 cases, and 1,590 deaths.

Signs and symptoms

Onset

The length of time between exposure to the virus and the development of symptoms (incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infectious disease, the i ...

) is between 2 and 21 days,influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

-like stage characterised by fatigue

Fatigue describes a state of tiredness that does not resolve with rest or sleep. In general usage, fatigue is synonymous with extreme tiredness or exhaustion that normally follows prolonged physical or mental activity. When it does not resolve ...

, fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a body temperature, temperature above the human body temperature, normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, set point. There is not a single ...

, weakness

Weakness is a symptom of a number of different conditions. The causes are many and can be divided into conditions that have true or perceived muscle weakness. True muscle weakness is a primary symptom of a variety of skeletal muscle diseases, i ...

, decreased appetite

Anorexia is a medical term for a loss of appetite. While the term in non-scientific publications is often used interchangeably with anorexia nervosa, many possible causes exist for a loss of appetite, some of which may be harmless, while others ...

, muscular pain, joint pain

Arthralgia (from Greek ''arthro-'', joint + ''-algos'', pain) literally means ''joint pain''. Specifically, arthralgia is a symptom of injury, infection, illness (in particular arthritis), or an allergic reaction to medication.

According to MeSH, ...

, headache, and sore throat.diarrhoea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin wi ...

, abdominal pain, and sometimes hiccups

A hiccup (scientific name ''singultus'', from a Latin word meaning "to catch one's breath while sobbing"; also spelled hiccough) is an involuntary contraction (myoclonic jerk) of the diaphragm that may repeat several times per minute. The hic ...

.dehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water, with an accompanying disruption of metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds free water intake, usually due to exercise, disease, or high environmental temperature. Mil ...

.shortness of breath

Shortness of breath (SOB), also medically known as dyspnea (in AmE) or dyspnoea (in BrE), is an uncomfortable feeling of not being able to breathe well enough. The American Thoracic Society defines it as "a subjective experience of breathing disc ...

and chest pain

Chest pain is pain or discomfort in the chest, typically the front of the chest. It may be described as sharp, dull, pressure, heaviness or squeezing. Associated symptoms may include pain in the shoulder, arm, upper abdomen, or jaw, along with n ...

may occur, along with swelling, headaches

Headache is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of depression in those with severe headaches.

Headaches can occur as a result of m ...

, and confusion

In medicine, confusion is the quality or state of being bewildered or unclear. The term "acute mental confusion" .[ In about half of the cases, the skin may develop a ]maculopapular rash

A maculopapular rash is a type of rash characterized by a flat, red area on the skin that is covered with small confluent bumps. It may only appear red in lighter-skinned people. The term "maculopapular" is a compound: ''macules'' are small, flat ...

, a flat red area covered with small bumps, five to seven days after symptoms begin.

Bleeding

In some cases, internal and external bleeding may occur.vomiting blood

Hematemesis is the vomiting of blood. It is always an important sign. It can be confused with hemoptysis (coughing up blood) or epistaxis (nosebleed), which are more common. The source is generally the upper gastrointestinal tract, typically abo ...

, coughing up of blood, or blood in stool

Blood in stool looks different depending on how early it enters the digestive tract—and thus how much digestive action it has been exposed to—and how much there is. The term can refer either to melena, with a black appearance, typically orig ...

. Bleeding into the skin may create petechia

A petechia () is a small red or purple spot (≤4 mm in diameter) that can appear on the skin, conjunctiva, retina, and Mucous membrane, mucous membranes which is caused by haemorrhage of capillaries. The word is derived from Italian , 'freckle,' ...

e, purpura

Purpura () is a condition of red or purple discolored spots on the skin that do not blanch on applying pressure. The spots are caused by bleeding underneath the skin secondary to platelet disorders, vascular disorders, coagulation disorders, ...

, ecchymoses

A bruise, also known as a contusion, is a type of hematoma of tissue, the most common cause being capillaries damaged by trauma, causing localized bleeding that extravasates into the surrounding interstitial tissues. Most bruises occur close e ...

or haematomas (especially around needle injection sites).gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organ (biology), organs of the digestive syste ...

.disseminated intravascular coagulation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a condition in which blood clots form throughout the body, blocking small blood vessels. Symptoms may include chest pain, shortness of breath, leg pain, problems speaking, or problems moving parts o ...

.

Recovery or death

Recovery may begin between seven and 14 days after first symptoms.[ Death, if it occurs, follows typically six to sixteen days from first symptoms and is often due to shock from fluid loss.][ In general, bleeding often indicates a worse outcome, and blood loss may result in death.]coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

near the end of life.[

Those who survive often have ongoing muscular and joint pain, liver inflammation, and decreased hearing, and may have continued tiredness, continued weakness, decreased appetite, and difficulty returning to pre-illness weight.]antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

against Ebola that last at least 10 years, but it is unclear whether they are immune to additional infections.

Cause

EVD in humans is caused by four of six viruses of the genus ''Ebolavirus

The genus ''Ebolavirus'' (- or ; - or ) is a virological taxon included in the family ''Filoviridae'' (filament-shaped viruses), order ''Mononegavirales''. The members of this genus are called ebolaviruses, and encode their genome in the form ...

''. The four are Bundibugyo virus

The species ''Bundibugyo ebolavirus'' ( ) is the taxonomic home of one virus, Bundibugyo virus (BDBV), that forms filamentous virions and is closely related to the infamous Ebola virus (EBOV). The virus causes severe disease in humans in the form ...

(BDBV), Sudan virus (SUDV), Taï Forest virus (TAFV) and one simply called Ebola virus

''Zaire ebolavirus'', more commonly known as Ebola virus (; EBOV), is one of six known species within the genus ''Ebolavirus''. Four of the six known ebolaviruses, including EBOV, cause a severe and often fatal hemorrhagic fever in humans and ot ...

(EBOV, formerly Zaire Ebola virus).Zaire ebolavirus

''Zaire ebolavirus'', more commonly known as Ebola virus (; EBOV), is one of six known species within the genus ''Ebolavirus''. Four of the six known ebolaviruses, including EBOV, cause a severe and often fatal hemorrhagic fever in humans and ot ...

'', is the most dangerous of the known EVD-causing viruses, and is responsible for the largest number of outbreaks.Reston virus

Reston virus (RESTV) is one of six known viruses within the genus ''Ebolavirus''. Reston virus causes Ebola virus disease in non-human primates; unlike the other five ebolaviruses, it is not known to cause disease in humans, but has caused asympt ...

(RESTV) and Bombali virus (BOMV), are not thought to cause disease in humans, but have caused disease in other primates.marburgvirus

The genus ''Marburgvirus'' is the taxonomic home of ''Marburg marburgvirus'', whose members are the two known marburgviruses, Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV). Both viruses cause Marburg virus disease in humans and nonhuman primate ...

es.

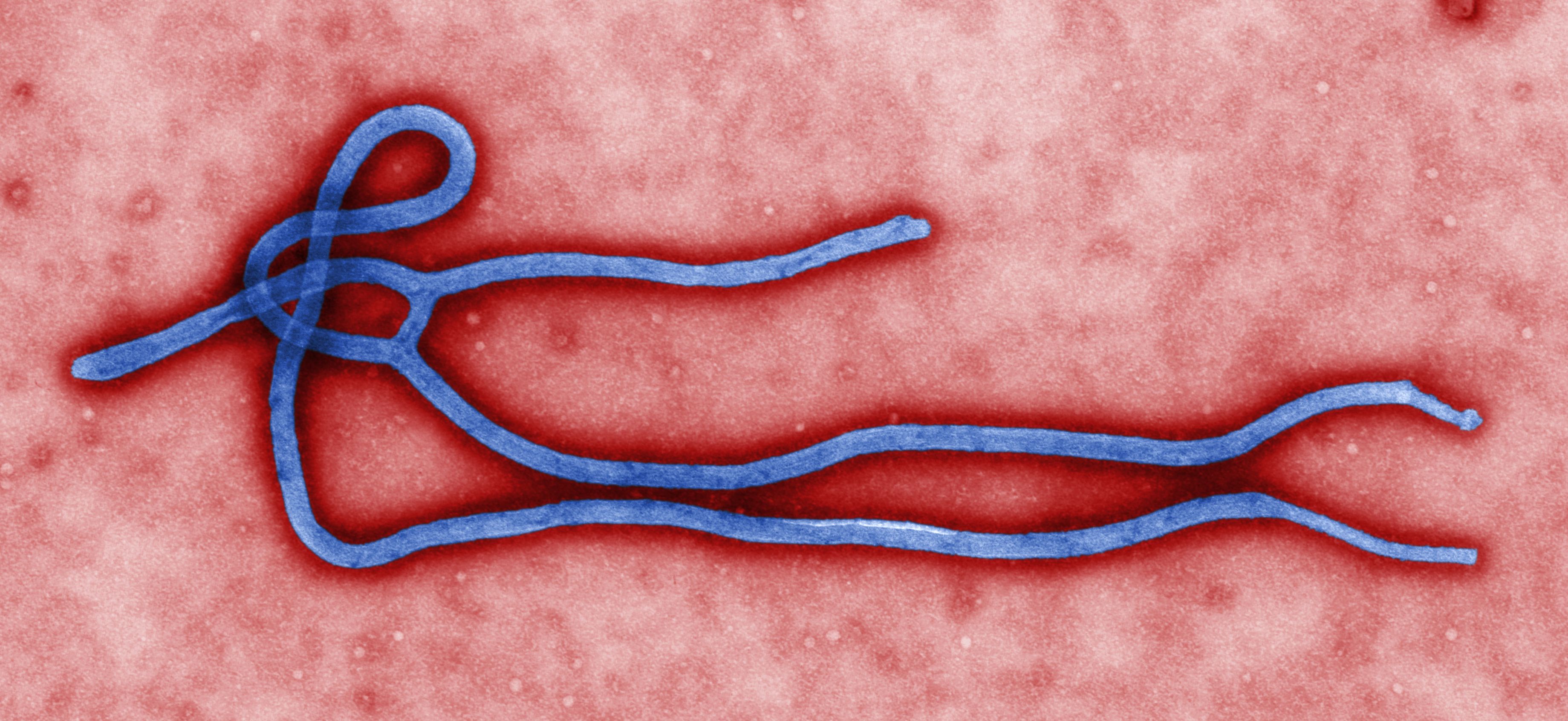

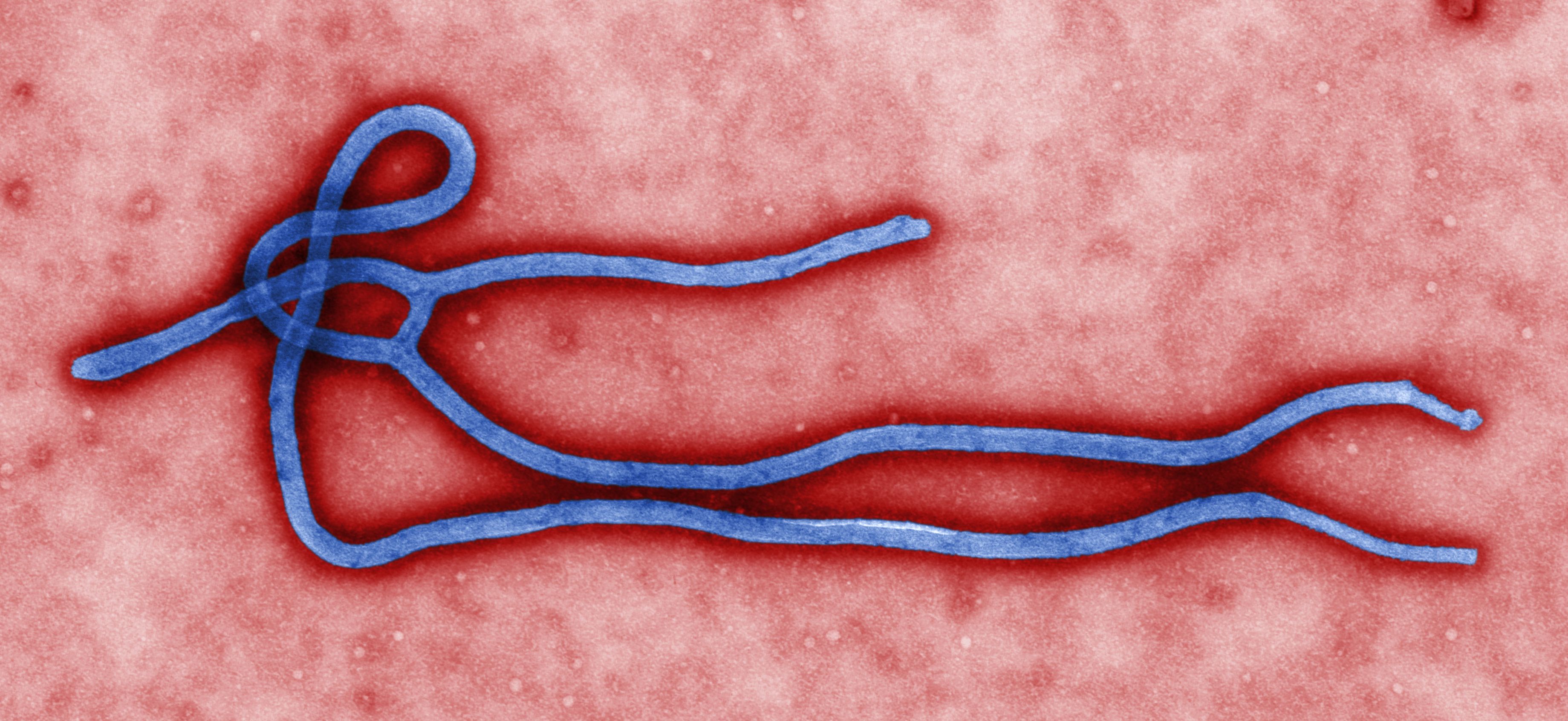

Virology

Ebolaviruses contain single-stranded, non-infectious

Ebolaviruses contain single-stranded, non-infectious RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

s.gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s including 3'-UTR-''NP''-''VP35''-''VP40''-''GP''-''VP30''-''VP24''-''L''- 5'-UTR.sequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is calle ...

and the number and location of gene overlaps. As with all filovirus

''Filoviridae'' () is a family of single-stranded negative-sense RNA viruses in the order ''Mononegavirales''. Two members of the family that are commonly known are Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Both viruses, and some of their lesser known rel ...

es, ebolavirus virions are filamentous particles that may appear in the shape of a shepherd's crook, of a "U" or of a "6," and they may be coiled, toroid or branched.life cycle

Life cycle, life-cycle, or lifecycle may refer to:

Science and academia

*Biological life cycle, the sequence of life stages that an organism undergoes from birth to reproduction ending with the production of the offspring

*Life-cycle hypothesis, ...

is thought to begin with a virion attaching to specific cell-surface receptors

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

such as C-type lectin

A C-type lectin (CLEC) is a type of carbohydrate-binding protein known as a lectin. The C-type designation is from their requirement for calcium for binding. Proteins that contain C-type lectin domains have a diverse range of functions including ...

s, DC-SIGN

DC-SIGN (Dendritic Cell-Specific Intercellular adhesion molecule-3-Grabbing Non-integrin) also known as CD209 ( Cluster of Differentiation 209) is a protein which in humans is encoded by the ''CD209'' gene.

DC-SIGN is a C-type lectin receptor pr ...

, or integrin

Integrins are transmembrane receptors that facilitate cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion. Upon ligand binding, integrins activate signal transduction pathways that mediate cellular signals such as regulation of the cell cycle, ...

s, which is followed by fusion of the viral envelope with cellular membranes.endosome

Endosomes are a collection of intracellular sorting organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are parts of endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi network. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membrane can ...

s and lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle found in many animal cells. They are spherical vesicles that contain hydrolytic enzymes that can break down many kinds of biomolecules. A lysosome has a specific composition, of both its membrane prot ...

s where the viral envelope glycoprotein GP is cleaved.nucleocapsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

.RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

, encoded by the ''L'' gene, partially uncoats the nucleocapsid and transcribes the genes into positive-strand mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

s, which are then translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

into structural and nonstructural proteins. The most abundant protein produced is the nucleoprotein, whose concentration in the host cell determines when L switches from gene transcription to genome replication. Replication of the viral genome results in full-length, positive-strand antigenomes that are, in turn, transcribed into genome copies of negative-strand virus progeny.cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

. Virions bud

In botany, a bud is an undeveloped or embryonic shoot and normally occurs in the axil of a leaf or at the tip of a stem. Once formed, a bud may remain for some time in a dormant condition, or it may form a shoot immediately. Buds may be spec ...

off from the cell, gaining their envelopes from the cellular membrane from which they bud. The mature progeny particles then infect other cells to repeat the cycle. The genetics of the Ebola virus are difficult to study because of EBOV's virulent characteristics.

Transmission

It is believed that between people, Ebola disease spreads only by direct contact with the blood or other

It is believed that between people, Ebola disease spreads only by direct contact with the blood or other body fluid

Body fluids, bodily fluids, or biofluids, sometimes body liquids, are liquids within the human body. In lean healthy adult men, the total body water is about 60% (60–67%) of the total Human body weight, body weight; it is usually slightly lower ...

s of a person who has developed symptoms of the disease.semen

Semen, also known as seminal fluid, is an organic bodily fluid created to contain spermatozoa. It is secreted by the gonads (sexual glands) and other sexual organs of male or hermaphroditic animals and can fertilize the female ovum. Semen i ...

.[ The WHO states that only people who are very sick are able to spread Ebola disease in ]saliva

Saliva (commonly referred to as spit) is an extracellular fluid produced and secreted by salivary glands in the mouth. In humans, saliva is around 99% water, plus electrolytes, mucus, white blood cells, epithelial cells (from which DNA can be ...

, and the virus has not been reported to be transmitted through sweat. Most people spread the virus through blood, feces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

and vomit. Entry points for the virus include the nose, mouth, eyes, open wounds, cuts and abrasions.droplets

A drop or droplet is a small column of liquid, bounded completely or almost completely by free surfaces. A drop may form when liquid accumulates at the lower end of a tube or other surface boundary, producing a hanging drop called a pendant d ...

; however, this is believed to occur only when a person is very sick.[ Contact with surfaces or objects contaminated by the virus, particularly needles and syringes, may also transmit the infection.][

The Ebola virus may be able to persist for more than three months in the semen after recovery, which could lead to infections via ]sexual intercourse

Sexual intercourse (or coitus or copulation) is a sexual activity typically involving the insertion and thrusting of the penis into the vagina for sexual pleasure or reproduction.Sexual intercourse most commonly means penile–vaginal penetrat ...

.[ Virus persistence in semen for over a year has been recorded in a national screening programme. Ebola may also occur in the breast milk of women after recovery, and it is not known when it is safe to breastfeed again.][ The virus was also found in the eye of one patient in 2014, two months after it was cleared from his blood. Otherwise, people who have recovered are not infectious.][

The potential for widespread infections in countries with medical systems capable of observing correct medical isolation procedures is considered low.]embalming

Embalming is the art and science of preserving human remains by treating them (in its modern form with chemicals) to forestall decomposition. This is usually done to make the deceased suitable for public or private viewing as part of the funeral ...

are at risk.[ Of the cases of Ebola infections in Guinea during the 2014 outbreak, 69% are believed to have been contracted via unprotected (or unsuitably protected) contact with infected corpses during certain Guinean burial rituals.][ This risk is particularly common in parts of Africa where the disease mostly occurs and health systems function poorly. There has been transmission in hospitals in some African countries that reuse hypodermic needles. Some health-care centres caring for people with the disease do not have running water.][ and airborne transmission has only been demonstrated in very strict laboratory conditions, and then only from pigs to ]primates

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

, but not from primates to primates.[ Other possible methods of transmission are being studied.]

Initial case

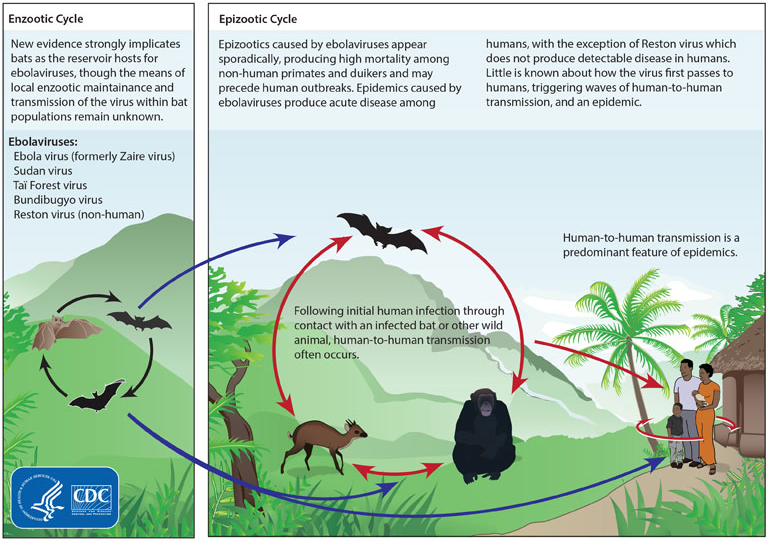

Although it is not entirely clear how Ebola initially spreads from animals to humans, the spread is believed to involve direct contact with an infected wild animal or fruit bat.

Although it is not entirely clear how Ebola initially spreads from animals to humans, the spread is believed to involve direct contact with an infected wild animal or fruit bat.[ Besides bats, other wild animals that are sometimes infected with EBOV include several species of monkeys such as ]baboon

Baboons are primates comprising the genus ''Papio'', one of the 23 genera of Old World monkeys. There are six species of baboon: the hamadryas baboon, the Guinea baboon, the olive baboon, the yellow baboon, the Kinda baboon and the chacma ba ...

s, great apes

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the east ...

(chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (''Pan troglodytes''), also known as simply the chimp, is a species of great ape native to the forest and savannah of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed subspecies. When its close relative th ...

s and gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or fi ...

s), and duikers

A duiker is a small to medium-sized brown antelope native to sub-Saharan Africa, found in heavily wooded areas. The 22 extant species, including three sometimes considered to be subspecies of the other species, form the subfamily Cephalophinae ...

(a species of antelope

The term antelope is used to refer to many species of even-toed ruminant that are indigenous to various regions in Africa and Eurasia.

Antelope comprise a wastebasket taxon defined as any of numerous Old World grazing and browsing hoofed mammals ...

).[ Fruit production, animal behavior and other factors may trigger outbreaks among animal populations.]

Reservoir

The natural reservoir

In infectious disease ecology and epidemiology, a natural reservoir, also known as a disease reservoir or a reservoir of infection, is the population of organisms or the specific environment in which an infectious pathogen naturally lives and rep ...

for Ebola has yet to be confirmed; however, bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and πτερόν''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most bi ...

s are considered to be the most likely candidate.Hypsignathus monstrosus

The hammer-headed bat ('), also known as hammer-headed fruit bat and big-lipped bat, is a megabat widely distributed in West and Central Africa. It is the only member of the genus ''Hypsignathus'', which is part of the tribe Epomophorini along w ...

'', ''Epomops franqueti

Franquet's epauletted fruit bat (''Epomops franqueti'') is a species of megabat in the family Pteropodidae, and is one of three different species of epauletted bats. Franquet's epauletted fruit bat has a range of habitats, varying from Subsaharan ...

'' and ''Myonycteris torquata

''Myonycteris'' (collared bat) is a genus of bat in the family Pteropodidae.

It contains the following species:Simmons, 2005, p. 328

Genus ''Myonycteris''

* São Tomé collared fruit bat, ''Myonycteris brachycephala''

* East African little col ...

'') were found to possibly carry the virus without getting sick. , whether other animals are involved in its spread is not known.arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a Segmentation (biology), segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and Arth ...

s, rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are na ...

s, and birds have also been considered possible viral reservoirs.Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

and the Republic of the Congo

The Republic of the Congo (french: République du Congo, ln, Republíki ya Kongó), also known as Congo-Brazzaville, the Congo Republic or simply either Congo or the Congo, is a country located in the western coast of Central Africa to the w ...

, immunoglobulin G (IgG) immune defense molecules indicative of Ebola infection were found in three bat species; at various periods of study, between 2.2 and 22.6% of bats were found to contain both RNA sequences and IgG molecules indicating Ebola infection. Antibodies against Zaire and Reston viruses have been found in fruit bats in Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

, suggesting that these bats are also potential hosts of the virus and that the filoviruses are present in Asia.arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a Segmentation (biology), segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and Arth ...

s sampled from regions of EBOV outbreaks, no Ebola virus was detected apart from some genetic traces found in six rodents (belonging to the species '' Mus setulosus'' and ''Praomys

''Praomys'' is a genus of rodent in the family Muridae endemic to Sub-Saharan Africa. It contains the following species:

* '' Praomys coetzeei''

* Dalton's mouse, ''Praomys daltoni''

* De Graaff's soft-furred mouse, ''Praomys degraaffi''

* Deroo ...

'') and one shrew

Shrews (family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to different fa ...

('' Sylvisorex ollula'') collected from the Central African Republic

The Central African Republic (CAR; ; , RCA; , or , ) is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the southeast, the DR Congo to the south, the Republic of th ...

.Deforestation

Deforestation or forest clearance is the removal of a forest or stand of trees from land that is then converted to non-forest use. Deforestation can involve conversion of forest land to farms, ranches, or urban use. The most concentrated d ...

has been mentioned as a possible contributor to recent outbreaks, including the West African Ebola virus epidemic

The 2013–2016 epidemic of Ebola virus disease, centered in Western Africa, was the most widespread outbreak of the disease in history. It caused major loss of life and socioeconomic disruption in the region, mainly in Guinea, Liberia and S ...

. Index cases of EVD have often been close to recently deforested lands.

Pathophysiology

Like other

Like other filoviruses

''Filoviridae'' () is a family of single-stranded negative-sense RNA viruses in the order ''Mononegavirales''. Two members of the family that are commonly known are Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Both viruses, and some of their lesser known re ...

, EBOV replicates very efficiently in many cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

, producing large amounts of virus in monocyte

Monocytes are a type of leukocyte or white blood cell. They are the largest type of leukocyte in blood and can differentiate into macrophages and conventional dendritic cells. As a part of the vertebrate innate immune system monocytes also inf ...

s, macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer cel ...

s, dendritic cell

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells (also known as ''accessory cells'') of the mammalian immune system. Their main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system. ...

s and other cells including liver cells

A hepatocyte is a cell of the main parenchymal tissue of the liver. Hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver's mass.

These cells are involved in:

* Protein synthesis

* Protein storage

* Transformation of carbohydrates

* Synthesis of cholesterol, bi ...

, fibroblast

A fibroblast is a type of cell (biology), biological cell that synthesizes the extracellular matrix and collagen, produces the structural framework (Stroma (tissue), stroma) for animal Tissue (biology), tissues, and plays a critical role in wound ...

s, and adrenal gland cells.endothelial cells

The endothelium is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the vessel ...

(cells lining the inside of blood vessels), liver cells, and several types of immune cells such as macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells are the main targets of attack.lymph node

A lymph node, or lymph gland, is a kidney-shaped organ of the lymphatic system and the adaptive immune system. A large number of lymph nodes are linked throughout the body by the lymphatic vessels. They are major sites of lymphocytes that inclu ...

s where further reproduction of the virus takes place.lymphatic system

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system, and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphatic or lymphoid o ...

and spread throughout the body.programmed cell death

Programmed cell death (PCD; sometimes referred to as cellular suicide) is the death of a cell as a result of events inside of a cell, such as apoptosis or autophagy. PCD is carried out in a biological process, which usually confers advantage durin ...

.white blood cell

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cell (biology), cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and de ...

s, such as lymphocyte

A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell (leukocyte) in the immune system of most vertebrates. Lymphocytes include natural killer cells (which function in cell-mediated, cytotoxic innate immunity), T cells (for cell-mediated, cytotoxic ad ...

s, also undergo programmed cell death leading to an abnormally low concentration of lymphocytes in the blood.blood vessel

The blood vessels are the components of the circulatory system that transport blood throughout the human body. These vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to the tissues of the body. They also take waste and carbon dioxide away ...

injury can be attributed to EBOV glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glycos ...

s. This damage occurs due to the synthesis of Ebola virus glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glycos ...

(GP), which reduces the availability of specific integrin

Integrins are transmembrane receptors that facilitate cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion. Upon ligand binding, integrins activate signal transduction pathways that mediate cellular signals such as regulation of the cell cycle, ...

s responsible for cell adhesion to the intercellular structure and causes liver damage, leading to improper clotting. The widespread bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

that occurs in affected people causes swelling and shock due to loss of blood volume.coagulation cascade

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

due to excessive tissue factor

Tissue factor, also called platelet tissue factor, factor III, or CD142, is a protein encoded by the ''F3'' gene, present in subendothelial tissue and leukocytes. Its role in the clotting process is the initiation of thrombin formation from the ...

production by macrophages and monocytes.glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glycos ...

, small soluble glycoprotein (sGP or GP) is synthesised. EBOV replication overwhelms protein synthesis of infected cells and the host immune defences. The GP forms a trimeric complex, which tethers the virus to the endothelial cells. The sGP forms a dimeric protein that interferes with the signalling of neutrophils

Neutrophils (also known as neutrocytes or heterophils) are the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. They form an essential part of the innate immune system, with their functions varying in ...

, another type of white blood cell. This enables the virus to evade the immune system by inhibiting early steps of neutrophil activation.

Immune system evasion

Filoviral infection also interferes with proper functioning of the innate immune system

The innate, or nonspecific, immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies (the other being the adaptive immune system) in vertebrates. The innate immune system is an older evolutionary defense strategy, relatively speaking, and is the ...

.interferon-alpha

The type-I interferons (IFN) are cytokines which play essential roles in inflammation, immunoregulation, tumor cells recognition, and T-cell responses. In the human genome, a cluster of thirteen functional IFN genes is located at the 9p21.3 cyto ...

, interferon-beta

The type-I interferons (IFN) are cytokines which play essential roles in inflammation, immunoregulation, tumor cells recognition, and T-cell responses. In the human genome, a cluster of thirteen functional IFN genes is located at the 9p21.3 cyto ...

, and interferon gamma

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) is a dimerized soluble cytokine that is the only member of the type II class of interferons. The existence of this interferon, which early in its history was known as immune interferon, was described by E. F. Wheelock ...

.cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells (intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

(such as RIG-I

RIG-I (retinoic acid-inducible gene I) is a cytosolic pattern recognition receptor (PRR) responsible for the type-1 interferon (IFN1) response. RIG-I is an essential molecule in the innate immune system for recognizing cells that have been infect ...

and MDA5

MDA5 (melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5) is a RIG-I-like receptor dsRNA helicase

Helicases are a class of enzymes thought to be vital to all organisms. Their main function is to unpack an organism's genetic material. Helicases are m ...

) or outside of the cytosol (such as Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), TLR7

Toll-like receptor 7, also known as TLR7, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TLR7'' gene. Orthologs are found in mammals and birds. It is a member of the toll-like receptor (TLR) family and detects single stranded RNA.

Function

T ...

, TLR8

Toll-like receptor 8 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TLR8'' gene. TLR8 has also been designated as CD288 (cluster of differentiation 288). It is a member of the toll-like receptor (TLR) family.

Function

TLR8 seems to function d ...

and TLR9

Toll-like receptor 9 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TLR9'' gene. TLR9 has also been designated as CD289 (cluster of differentiation 289). It is a member of the toll-like receptor (TLR) family. TLR9 is an important receptor expresse ...

) recognise infectious molecules associated with the virus.IFNAR1

Interferon-alpha/beta receptor alpha chain is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''IFNAR1'' gene.

Function

The protein encoded by this gene is a type I membrane protein that forms one of the two chains of a receptor for type I interfer ...

and IFNAR2

Interferon-alpha/beta receptor beta chain is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''IFNAR2'' gene.

Function

The protein encoded by this gene is a type I membrane protein that forms one of the two chains of a receptor for interferons alp ...

receptors expressed on the surface of a neighbouring cell.STAT1

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) is a transcription factor which in humans is encoded by the ''STAT1'' gene. It is a member of the STAT protein family.

Function

All STAT molecules are phosphorylated by receptor associa ...

and STAT2

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''STAT2'' gene. It is a member of the STAT protein family. This protein is critical to the biological response of type I interferons (IFNs). STAT2 se ...

are activated and move to the cell's nucleus.

Diagnosis

When EVD is suspected, travel, work history, and exposure to wildlife are important factors with respect to further diagnostic efforts.

Laboratory testing

Possible non-specific laboratory indicators of EVD include a low platelet count

Thrombocytopenia is a condition characterized by abnormally low levels of platelets, also known as thrombocytes, in the blood. It is the most common coagulation disorder among intensive care patients and is seen in a fifth of medical patients and ...

; an initially decreased white blood cell count followed by an increased white blood cell count; elevated levels of the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase

Alanine transaminase (ALT) is a transaminase enzyme (). It is also called alanine aminotransferase (ALT or ALAT) and was formerly called serum glutamate-pyruvate transaminase or serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) and was first character ...

(ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase

Aspartate transaminase (AST) or aspartate aminotransferase, also known as AspAT/ASAT/AAT or (serum) glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT, SGOT), is a pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent transaminase enzyme () that was first described by Arthur ...

(AST); and abnormalities in blood clotting often consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a condition in which blood clots form throughout the body, blocking small blood vessels. Symptoms may include chest pain, shortness of breath, leg pain, problems speaking, or problems moving parts o ...

(DIC) such as a prolonged prothrombin time

The prothrombin time (PT) – along with its derived measures of prothrombin ratio (PR) and international normalized ratio (INR) – is an assay for evaluating the ''extrinsic'' pathway and common pathway of coagulation. This blood test is als ...

, partial thromboplastin time

The partial thromboplastin time (PTT), also known as the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT or APTT), is a blood test that characterizes coagulation of the blood. A historical name for this measure is the kaolin-cephalin clotting time ( ...

, and bleeding time

Bleeding time is a medical test done on someone to assess their platelets function. It involves making a patient bleed, then timing how long it takes for them to stop bleeding using a stopwatch or other suitable devices.

The term template bleedin ...

.electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

.RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

or proteins, or detecting antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

against the virus in a person's blood.[ Isolating the virus by ]cell culture

Cell culture or tissue culture is the process by which cells are grown under controlled conditions, generally outside of their natural environment. The term "tissue culture" was coined by American pathologist Montrose Thomas Burrows. This te ...

, detecting the viral RNA by polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) t ...

(PCR)enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay uses a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence ...

(ELISA) are methods best used in the early stages of the disease and also for detecting the virus in human remains.[ Detecting antibodies against the virus is most reliable in the later stages of the disease and in those who recover.]IgG antibodies

Immunoglobulin G (Ig G) is a type of antibody. Representing approximately 75% of serum antibodies in humans, IgG is the most common type of antibody found in blood circulation. IgG molecules are created and released by plasma B cells. Each IgG ...

can be detected six to 18 days after symptom onset.real-time PCR

A real-time polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR, or qPCR) is a laboratory technique of molecular biology based on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). It monitors the amplification of a targeted DNA molecule during the PCR (i.e., in real ...

and ELISA.[ It is able to confirm Ebola in 92% of those affected and rule it out in 85% of those not affected.]

Differential diagnosis

Early symptoms of EVD may be similar to those of other diseases common in Africa, including malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

and dengue fever

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus. Symptoms typically begin three to fourteen days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characterist ...

.Marburg virus disease

Marburg virus disease (MVD; formerly Marburg hemorrhagic fever) is a viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and primates caused by either of the two Marburgviruses: Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV). Its clinical symptoms are very similar t ...

, Crimean–Congo haemorrhagic fever, and Lassa fever

Lassa fever, also known as Lassa hemorrhagic fever (LHF), is a type of viral hemorrhagic fever caused by the Lassa virus. Many of those infected by the virus do not develop symptoms. When symptoms occur they typically include fever, weakness, h ...

.differential diagnosis

In healthcare, a differential diagnosis (abbreviated DDx) is a method of analysis of a patient's history and physical examination to arrive at the correct diagnosis. It involves distinguishing a particular disease or condition from others that p ...

is extensive and requires consideration of many other infectious diseases such as typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

, shigellosis

Shigellosis is an infection of the intestines caused by ''Shigella'' bacteria. Symptoms generally start one to two days after exposure and include diarrhea, fever, abdominal pain, and feeling the need to pass stools even when the bowels are emp ...

, rickettsial diseases, cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

, borreliosis

Lyme disease, also known as Lyme borreliosis, is a vector-borne disease caused by the ''Borrelia'' bacterium, which is spread by ticks in the genus ''Ixodes''. The most common sign of infection is an expanding red rash, known as erythema migran ...

, EHEC enteritis, leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a blood infection caused by the bacteria ''Leptospira''. Signs and symptoms can range from none to mild (headaches, muscle pains, and fevers) to severe ( bleeding in the lungs or meningitis). Weil's disease, the acute, severe ...

, scrub typhus

Scrub typhus or bush typhus is a form of typhus caused by the intracellular parasite ''Orientia tsutsugamushi'', a Gram-negative α-proteobacterium of family Rickettsiaceae first isolated and identified in 1930 in Japan.[plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...]

, Q fever

Q fever or query fever is a disease caused by infection with ''Coxiella burnetii'', a bacterium that affects humans and other animals. This organism is uncommon, but may be found in cattle, sheep, goats, and other domestic mammals, including ...

, candidiasis

Candidiasis is a fungal infection due to any type of '' Candida'' (a type of yeast). When it affects the mouth, in some countries it is commonly called thrush. Signs and symptoms include white patches on the tongue or other areas of the mouth ...

, histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is a fungal infection caused by ''Histoplasma capsulatum''. Symptoms of this infection vary greatly, but the disease affects primarily the lungs. Occasionally, other organs are affected; called disseminated histoplasmosis, it can ...

, trypanosomiasis

Trypanosomiasis or trypanosomosis is the name of several diseases in vertebrates caused by parasitic protozoan trypanosomes of the genus ''Trypanosoma''. In humans this includes African trypanosomiasis and Chagas disease. A number of other diseas ...

, visceral

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a wide array of clinical manifestations caused by parasites of the trypanosome genus ''Leishmania''. It is generally spread through the bite of phlebotomine sandflies, ''Phlebotomus'' and ''Lutzomyia'', and occurs most freq ...

, measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, and viral hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is liver inflammation due to a viral infection. It may present in acute form as a recent infection with relatively rapid onset, or in chronic form.

The most common causes of viral hepatitis are the five unrelated hepatotropic v ...

among others.

Non-infectious diseases that may result in symptoms similar to those of EVD include acute promyelocytic leukaemia

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML, APL) is a subtype of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a cancer of the white blood cells. In APL, there is an abnormal accumulation of immature granulocytes called promyelocytes. The disease is characterized by a ...

, haemolytic uraemic syndrome

Hemolysis or haemolysis (), also known by several other names, is the rupturing ( lysis) of red blood cells (erythrocytes) and the release of their contents (cytoplasm) into surrounding fluid (e.g. blood plasma). Hemolysis may occur in vivo ...

, snake envenomation

A snakebite is an injury caused by the bite of a snake, especially a venomous snake. A common sign of a bite from a venomous snake is the presence of two puncture wounds from the animal's fangs. Sometimes venom injection from the bite may occu ...

, clotting factor

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

deficiencies/platelet disorders, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a blood disorder that results in blood clots forming in small blood vessels throughout the body. This results in a low platelet count, low red blood cells due to their breakdown, and often kidney, h ...

, hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler–Weber–Rendu disease and Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome, is a rare autosomal dominant genetic disorder that leads to abnormal blood vessel formation in the skin, mucous membranes, ...

, Kawasaki disease

Kawasaki disease is a syndrome of unknown cause that results in a fever and mainly affects children under 5 years of age. It is a form of vasculitis, where blood vessels become inflamed throughout the body. The fever typically lasts for more tha ...

, and warfarin

Warfarin, sold under the brand name Coumadin among others, is a medication that is used as an anticoagulant (blood thinner). It is commonly used to prevent blood clots such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, and to prevent strok ...

poisoning.

Prevention

Vaccines

An Ebola vaccine

Ebola vaccines are vaccines either approved or in development to prevent Ebola. As of 2022, there are only vaccines against the Zaire ebolavirus. The first vaccine to be approved in the United States was rVSV-ZEBOV in December 2019. It had been ...

, rVSV-ZEBOV

Recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–Zaire Ebola virus (rVSV-ZEBOV), also known as Ebola Zaire vaccine live and sold under the brand name Ervebo, is an Ebola vaccine for adults that prevents Ebola caused by the Zaire ebolavirus. When used ...

, was approved in the United States in December 2019.[ It was studied in Guinea between 2014 and 2016.][ More than 100,000 people have been vaccinated against Ebola .

]

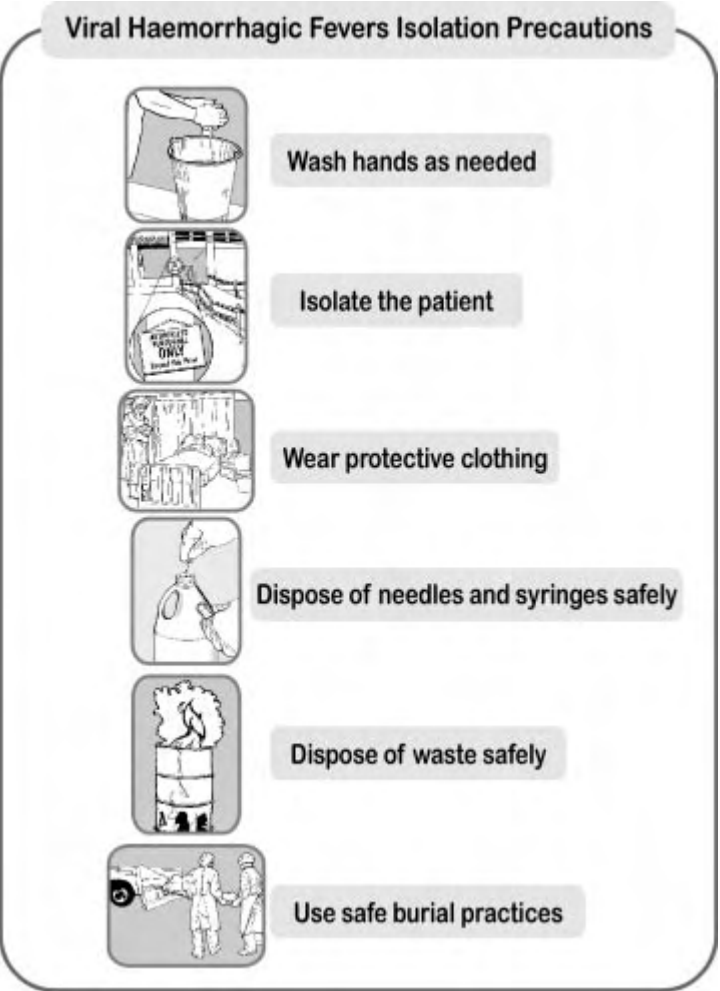

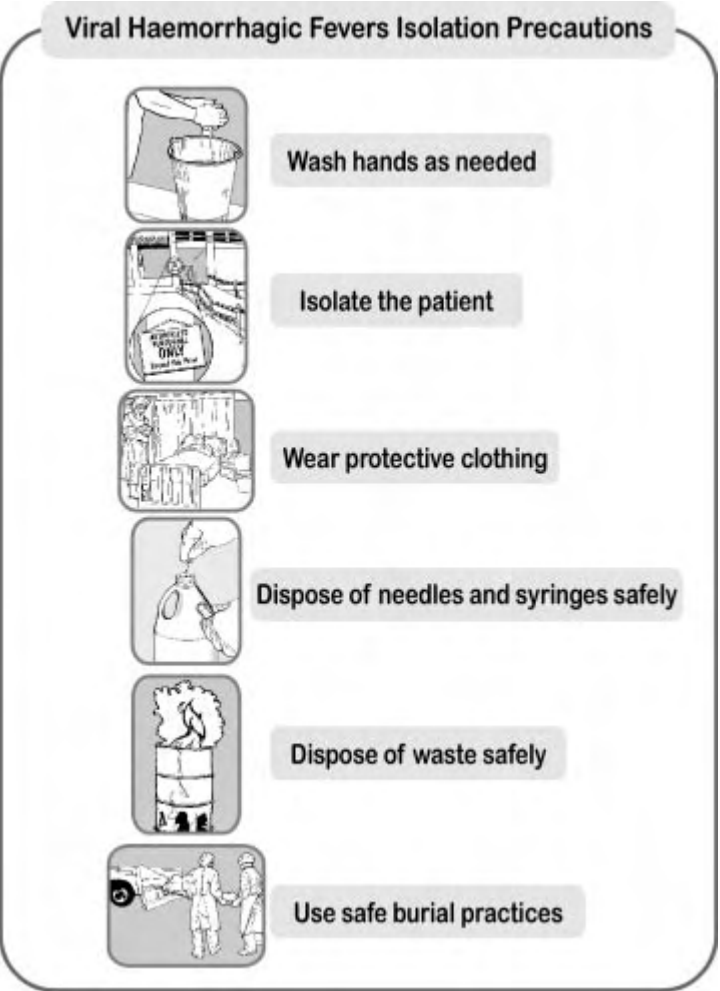

Infection control

Community awareness of the benefits on survival chances of admitting cases early is important for the infected and infection control

Community awareness of the benefits on survival chances of admitting cases early is important for the infected and infection control

Caregivers

People who care for those infected with Ebola should wear protective clothing including masks, gloves, gowns and goggles.

People who care for those infected with Ebola should wear protective clothing including masks, gloves, gowns and goggles.[ The U.S. ]Centers for Disease Control

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency, under the Department of Health and Human Services, and is headquartered in Atlanta, Georgi ...

(CDC) recommend that the protective gear leaves no skin exposed.[ These measures are also recommended for those who may handle objects contaminated by an infected person's body fluids.][ In 2014, the CDC began recommending that medical personnel receive training on the proper suit-up and removal of ]personal protective equipment

Personal protective equipment (PPE) is protective clothing, helmets, goggles, or other garments or equipment designed to protect the wearer's body from injury or infection. The hazards addressed by protective equipment include physical, elec ...

(PPE); in addition, a designated person, appropriately trained in biosafety, should be watching each step of these procedures to ensure they are done correctly.

Patients and household members

The infected person should be in barrier-isolation from other people.[ All equipment, medical waste, patient waste and surfaces that may have come into contact with body fluids need to be ]disinfected

A disinfectant is a chemical substance or compound used to inactivate or destroy microorganisms on inert surfaces. Disinfection does not necessarily kill all microorganisms, especially resistant bacterial spores; it is less effective than st ...

.Doctors Without Borders

Doctor or The Doctor may refer to:

Personal titles

* Doctor (title), the holder of an accredited academic degree

* A medical practitioner, including:

** Physician

** Surgeon

** Dentist

** Veterinary physician

** Optometrist

*Other roles

** ...

.

Disinfection

Ebolaviruses can be eliminated with heat (heating for 30 to 60 minutes at 60 °C or boiling for five minutes). To disinfect

A disinfectant is a chemical substance or compound used to inactivate or destroy microorganisms on inert surfaces. Disinfection does not necessarily kill all microorganisms, especially resistant bacterial spores; it is less effective than ste ...

surfaces, some lipid solvents such as some alcohol-based products, detergents, sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or calcium hypochlorite

Calcium hypochlorite is an inorganic compound with formula Ca(OCl)2. It is the main active ingredient of commercial products called bleaching powder, chlorine powder, or chlorinated lime, used for water treatment and as a bleaching agent. Thi ...

(bleaching powder), and other suitable disinfectants may be used at appropriate concentrations.

General population

Education of the general public about the risk factors for Ebola infection and of the protective measures individuals may take to prevent infection is recommended by the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

.[ These measures include avoiding direct contact with infected people and regular ]hand washing

Hand washing (or handwashing), also known as hand hygiene, is the act of cleaning one's hands with soap, soap or handwash and water to remove viruses/bacteria/microorganisms, dirt, grease, or other harmful and unwanted substances stuck to the ...

using soap and water.

Bushmeat

Bushmeat

Bushmeat is meat from wildlife species that are hunted for human consumption, most often referring to the meat of game in Africa. Bushmeat represents

a primary source of animal protein and a cash-earning commodity for inhabitants of humid tropi ...

, an important source of protein in the diet of some Africans, should be handled and prepared with appropriate protective clothing and thoroughly cooked before consumption.[ Some research suggests that an outbreak of Ebola disease in the wild animals used for consumption may result in a corresponding human outbreak. Since 2003, such animal outbreaks have been monitored to predict and prevent Ebola outbreaks in humans.]

Corpses, burial

If a person with Ebola disease dies, direct contact with the body should be avoided.

Transport, travel, contact

Transportation crews are instructed to follow a certain isolation procedure, should anyone exhibit symptoms resembling EVD.[ In October 2014, the CDC defined four risk levels used to determine the level of 21-day monitoring for symptoms and restrictions on public activities.][

* having been in a country with widespread Ebola disease transmission and having no known exposure (low risk); or having been in that country more than 21 days ago (no risk)

* encounter with a person showing symptoms; but not within three feet of the person with Ebola without wearing PPE; and no direct contact with body fluids

* having had brief skin contact with a person showing symptoms of Ebola disease when the person was believed to be not very contagious (low risk)

* in countries without widespread Ebola disease transmission: direct contact with a person showing symptoms of the disease while wearing PPE (low risk)

* contact with a person with Ebola disease before the person was showing symptoms (no risk).

The CDC recommends monitoring for the symptoms of Ebola disease for those both at "low risk" and at higher risk.][

]

Laboratory

In laboratories where diagnostic testing is carried out, biosafety level 4-equivalent containment is required.[

]

Isolation

Isolation refers to separating those who are sick from those who are not. Quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been ...

refers to separating those who may have been exposed to a disease until they either show signs of the disease or are no longer at risk. Quarantine, also known as enforced isolation, is usually effective in decreasing spread.

Contact tracing

Contact tracing

In public health, contact tracing is the process of identifying persons who may have been exposed to an infected person ("contacts") and subsequent collection of further data to assess transmission. By tracing the contacts of infected individua ...

is considered important to contain an outbreak. It involves finding everyone who had close contact with infected individuals and monitoring them for signs of illness for 21 days. If any of these contacts comes down with the disease, they should be isolated, tested and treated. Then the process is repeated, tracing the contacts' contacts.

Management

two treatments (atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab

Atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab, sold under the brand name Inmazeb, is a fixed-dose combination of three monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of '' Zaire ebolavirus'' (Ebola virus). It contains atoltivimab, maftivimab, and odesivimab-eb ...

and ansuvimab

Ansuvimab, sold under the brand name Ebanga, is a monoclonal antibody medication for the treatment of ''Zaire ebolavirus'' (Ebolavirus) infection.

The most common symptoms include fever, tachycardia (fast heart rate), diarrhea, vomiting, hypote ...

) are associated with improved outcomes.[ The U.S. ]Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respon ...

(FDA) advises people to be careful of advertisements making unverified or fraudulent claims of benefits supposedly gained from various anti-Ebola products.Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respon ...

(FDA) approved atoltivimab/maftivimab/odesivimab with an indication for the treatment of infection caused by ''Zaire ebolavirus''.[ ]

Standard support

Treatment is primarily supportive in nature.

Treatment is primarily supportive in nature.[ Rehydration may be via the ]oral

The word oral may refer to:

Relating to the mouth

* Relating to the mouth, the first portion of the alimentary canal that primarily receives food and liquid

**Oral administration of medicines

** Oral examination (also known as an oral exam or oral ...

or intravenous

Intravenous therapy (abbreviated as IV therapy) is a medical technique that administers fluids, medications and nutrients directly into a person's vein. The intravenous route of administration is commonly used for rehydration or to provide nutrie ...

route.[ These measures may include ]pain management

Pain management is an aspect of medicine and health care involving relief of pain (pain relief, analgesia, pain control) in various dimensions, from acute and simple to chronic and challenging. Most physicians and other health professionals pr ...

, and treatment for nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. While not painful, it can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the ...

, fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a body temperature, temperature above the human body temperature, normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, set point. There is not a single ...

, and anxiety

Anxiety is an emotion which is characterized by an unpleasant state of inner turmoil and includes feelings of dread over anticipated events. Anxiety is different than fear in that the former is defined as the anticipation of a future threat wh ...

.[ The ]World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

(WHO) recommends avoiding aspirin

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat inc ...

or ibuprofen