New Forest Act 1964 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The New Forest is one of the largest remaining tracts of unenclosed

pasture

Pasture (from the Latin ''pastus'', past participle of ''pascere'', "to feed") is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep, or swine ...

land, heathland and forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

in Southern England

Southern England, or the South of England, also known as the South, is an area of England consisting of its southernmost part, with cultural, economic and political differences from the Midlands and the North. Officially, the area includes G ...

, covering southwest Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

and southeast Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

. It was proclaimed a royal forest by William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

, featuring in the Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

.

It is the home of the New Forest Commoners, whose ancient rights of common pasture are still recognised and exercised, enforced by official verderers

Verderers are forestry officials in England who deal with common land in certain former royal hunting areas which are the property of the Crown. The office was developed in the Middle Ages to administer forest law on behalf of the King. Verderers ...

and agisters. In the 18th century, the New Forest became a source of timber for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. It remains a habitat for many rare birds and mammals.

It is a biological and geological Site of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle of ...

. Several areas are Geological Conservation Review and Nature Conservation Review

''A Nature Conservation Review'' is a two-volume work by Derek Ratcliffe, published by Cambridge University Press in 1977. It set out to identify the most important places for nature conservation in Great Britain. It is often known by the initial ...

sites. It is a Special Area of Conservation, a Ramsar site

A Ramsar site is a wetland site designated to be of international importance under the Ramsar Convention,8 ha (O)

*** Permanent 8 ha (P)

*** Seasonal Intermittent < 8 ha(Ts)

**

Special Protection Area. Copythorne Common is managed by the

Following

Following

File:Death of William Rufus.JPG, Death of William Rufus

File:Rufus Stone.jpg, The Rufus Stone Memorial

File:NewForestIbsleyww2.jpg, WW2 remains at Ibsley

Forest laws were enacted to preserve the New Forest as a location for royal

Forest laws were enacted to preserve the New Forest as a location for royal

The New Forest National Park area covers , and the New Forest

The New Forest National Park area covers , and the New Forest

All three British native species of snake inhabit the Forest. The adder (''

All three British native species of snake inhabit the Forest. The adder (''

Commoners' cattle, ponies and donkeys roam throughout the open heath and much of the woodland, and it is largely their grazing that maintains the open character of the Forest. They are also frequently seen in the Forest villages, where home and shop owners must take care to keep them out of gardens and shops. The

Commoners' cattle, ponies and donkeys roam throughout the open heath and much of the woodland, and it is largely their grazing that maintains the open character of the Forest. They are also frequently seen in the Forest villages, where home and shop owners must take care to keep them out of gardens and shops. The

Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust is a Wildlife Trust with 27,000 members across the counties of Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, England.

The trust describes itself as the leading local wildlife conservation charity in Hampshire and th ...

, Kingston Great Common is a national nature reserve and New Forest Northern Commons is managed by the National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

.

The New Forest covers two parliamentary constituencies

An electoral district, also known as an election district, legislative district, voting district, constituency, riding, ward, division, or (election) precinct is a subdivision of a larger state (a country, administrative region

Administra ...

; New Forest East and New Forest West

New Forest West is a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament since 1997 by Desmond Swayne, a Conservative.

Constituency profile

This constituency covers the part of the New Forest which is not covered by New Fo ...

.

Prehistory

Like much of England, the site of the New Forest was oncedeciduous

In the fields of horticulture and Botany, the term ''deciduous'' () means "falling off at maturity" and "tending to fall off", in reference to trees and shrubs that seasonally shed leaves, usually in the autumn; to the shedding of petals, aft ...

woodland, recolonised by birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 30 ...

and eventually beech

Beech (''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia, and North America. Recent classifications recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera, ''Engleriana'' and ''Fagus''. The ''Engle ...

and oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

after the withdrawal of the ice sheets starting around 12,000 years ago. Some areas were cleared for cultivation from the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

onwards; the poor quality of the soil in the New Forest meant that the cleared areas turned into heathland "waste", which may have been used even then as grazing land for horses.

There was still a significant amount of woodland in this part of Britain, but this was gradually reduced, particularly towards the end of the Middle Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

around 250–100 BC, and most importantly the 12th and 13th centuries, and of this essentially all that remains today is the New Forest.

There are around 250 round barrow

A round barrow is a type of tumulus and is one of the most common types of archaeological monuments. Although concentrated in Europe, they are found in many parts of the world, probably because of their simple construction and universal purpose. ...

s within its boundaries, and scattered boiling mounds, and it also includes about 150 scheduled monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a nationally important archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorised change.

The various pieces of legislation that legally protect heritage assets from damage and d ...

s. One such barrow in particular may represent the only known inhumation

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

burial of the Early Iron Age and the only known Hallstatt culture

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western Europe, Western and Central European Archaeological culture, culture of Late Bronze Age Europe, Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe ...

burial in Britain; however, the acidity of the soil means that bone very rarely survives.

History

Following

Following Anglo-Saxon settlement

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain is the process which changed the language and culture of most of what became England from Romano-British to Germanic. The Germanic-speakers in Britain, themselves of diverse origins, eventually develope ...

in Britain, according to Florence of Worcester (d. 1118), the area became the site of the Jutish kingdom of ''Ytene''; this name was the genitive plural of ''Yt'' meaning "Jute", i.e. "of the Jutes". The Jutes were one of the early Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

tribal groups who colonised this area of southern Hampshire.

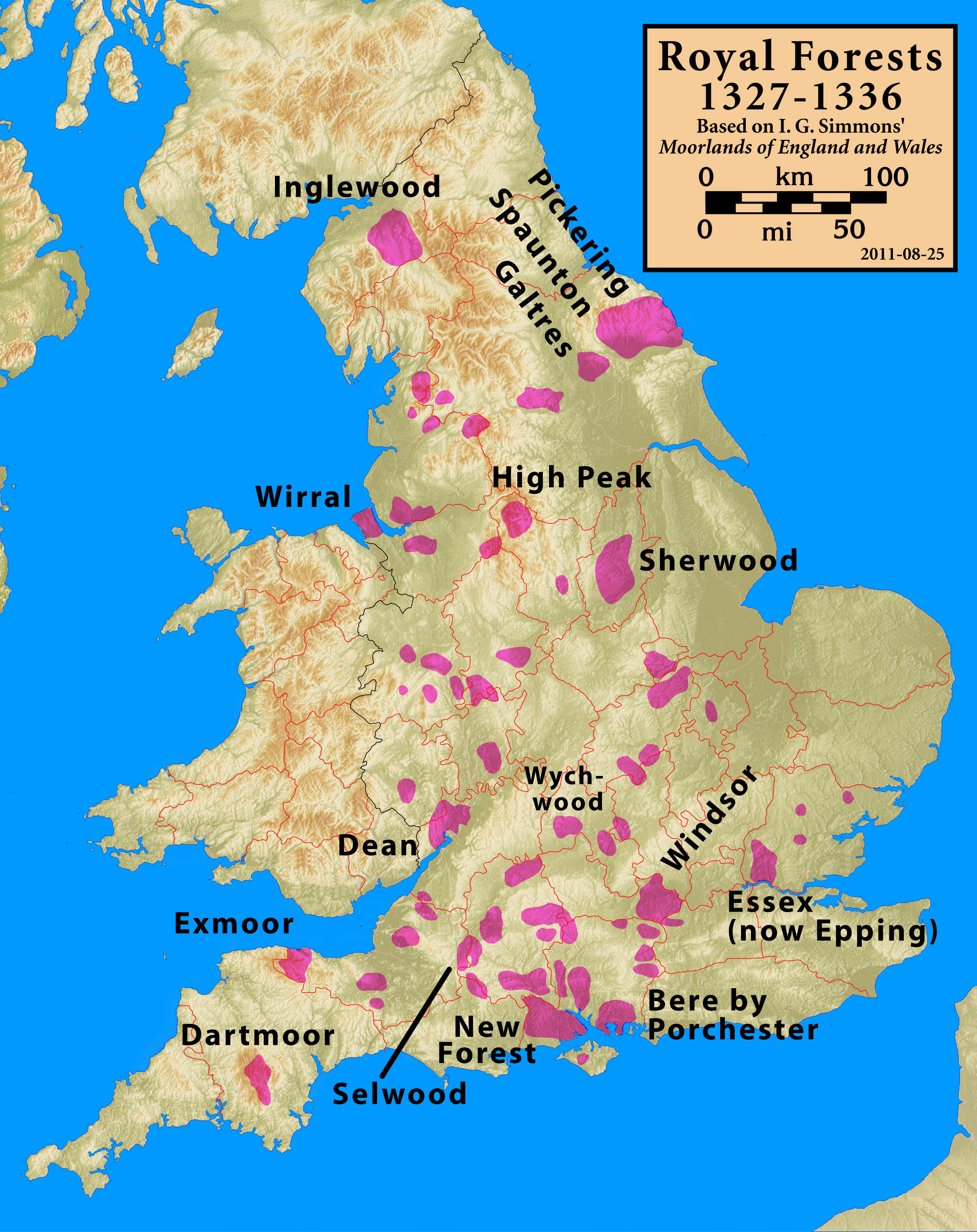

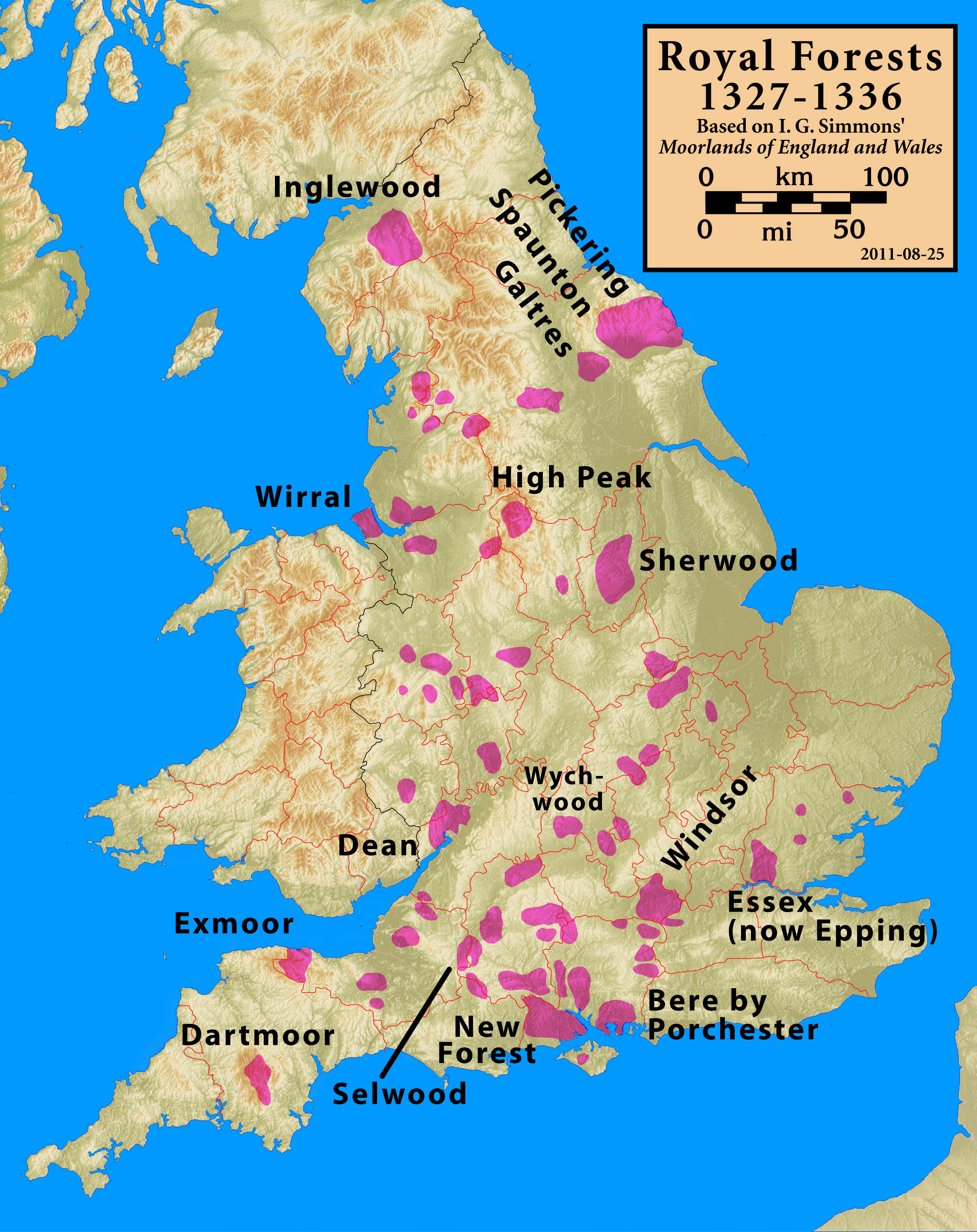

Following the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conque ...

, the New Forest was proclaimed a royal forest, in about 1079, by William the Conqueror

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first House of Normandy, Norman List of English monarchs#House of Norman ...

. It was used for royal hunts, mainly of deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the reindeer ...

. It was created at the expense of more than 20 small hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

s and isolated farmsteads; hence it was then 'new' as a single compact area.

The New Forest was first recorded as ''Nova Foresta'' in Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manusc ...

in 1086, where a section devoted to it is interpolated between lands of the king's thegns and the town of Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

; it is the only forest that the book describes in detail. Twelfth-century chroniclers alleged that William had created the forest by evicting the inhabitants of 36 parishes, reducing a flourishing district to a wasteland; however, this account is thought dubious by most historians, as the poor soil in much of the area is believed to have been incapable of supporting large-scale agriculture, and significant areas appear to have always been uninhabited.

Two of William's sons died in the forest: Prince Richard Prince Richard may refer to:

* Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York (1473–)

* Prince Richard von Metternich (1829–1895), from the German House of Metternich

* Prince Richard of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg (1934–2017), from the German House of ...

sometime between 1069 and 1075, and King William II (William Rufus) in 1100. Though many claim the latter is due to an inaccurate arrow shot from his hunting companion, ocal folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

asserted that this was punishment for the crimes committed by William when he created his New Forest; 17th-century writer Richard Blome provides detail:

In this County antshireis New-Forest, formerly called Ytene, being about 30 miles in compass; in which said tract William the Conqueror (for the making of the said Forest a harbour for Wild-beasts for his Game) caused 36 Parish Churches, with all the Houses thereto belonging, to be pulled down, and the poor Inhabitants left succourless of house or home. But this wicked act did not long go unpunished, for his Sons felt the smart thereof; Richard being blasted with a pestilent Air; Rufus shot through with an Arrow; and Henry his Grand-child, by Robert his eldest son, as he pursued his Game, was hanged among the boughs, and so dyed. This Forest at present affordeth great variety of Game, where his Majesty oft-times withdraws himself for his divertisement.The reputed spot of Rufus's death is marked with a stone known as the

Rufus Stone

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

.

John White, Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' (except dur ...

, said of the forest:

From God and Saint King Rufus did Churches take, From Citizens town-court, and mercate place, From Farmer lands: New Forrest for to make, In Beaulew tract, where whiles the King in chase Pursues the hart, just vengeance comes apace, And King pursues. Tirrell him seing not, Unwares him flew with dint of arrow shot.The

common

Common may refer to:

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Common, common land area in Cambridge, Massachusetts

* Clapham Common, originally com ...

rights were confirmed by statute in 1698. The New Forest became a source of timber for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, and plantations were created in the 18th century for this purpose. In the Great Storm of 1703, about 4000 oak trees were lost.

The naval plantations encroached on the rights of the Commoners, but the Forest gained new protection under the New Forest Act 1877, which confirmed the historic rights of the Commoners and entrenched that the total of enclosures was henceforth not to exceed at any time. It also reconstituted the Court of Verderers as representatives of the Commoners (rather than the Crown).

, roughly 90% of the New Forest is still owned by the Crown. The Crown lands have been managed by Forestry England

Forestry England is a division of the Forestry Commission, responsible for managing and promoting publicly owned forests in England. It was formed as Forest Enterprise in 1996, before devolving to Forest Enterprise England on 31 March 2003 and ...

since 1923 and most of the Crown lands now fall inside the new National Park.

Felling of broadleaved trees, and their replacement by conifer

Conifers are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single ...

s, began during the First World War to meet the wartime demand for wood. Further encroachments were made during the Second World War. This process is today being reversed in places, with some plantations being returned to heathland or broadleaved woodland. Rhododendron

''Rhododendron'' (; from Ancient Greek ''rhódon'' "rose" and ''déndron'' "tree") is a very large genus of about 1,024 species of woody plants in the heath family (Ericaceae). They can be either evergreen or deciduous. Most species are nati ...

remains a problem.

During the Second World War, an area of the forest, Ashley Range, was used as a bombing range. During 1941–1945, the Beaulieu, Hampshire Estate of Lord Montagu in the New Forest was the site of group B finishing schools for agents operated by the Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a secret British World War II organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing secret organisations. Its pu ...

(SOE) between 1941 and 1945. (One of the trainers was Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963 he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring which had divulged British secr ...

who was later found to be part of a spy ring passing information to the Soviets.) In 2005, a special exhibition was mounted at the Estate, with a video showing photographs from that era as well as voice recordings of former SOE trainers and agents.

Further New Forest Acts followed in 1949, 1964 and 1970. The New Forest became a Site of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle of ...

in 1971, and was granted special status as the New Forest Heritage Area in 1985, with additional planning controls added in 1992. The New Forest was proposed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

in June 1999, but UNESCO did not take up the nomination. It became a National Park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

in March 2005, transferring a wide variety of planning and control decisions to the New Forest National Park Authority, who work alongside the local authorities, land owners and crown estates in managing the New Forest.

Common rights

Forest laws were enacted to preserve the New Forest as a location for royal

Forest laws were enacted to preserve the New Forest as a location for royal deer hunting

Deer hunting is hunting for deer for meat and sport, an activity which dates back tens of thousands of years. Venison, the name for deer meat, is a nutritious and natural food source of animal protein that can be obtained through deer hunting. ...

, and interference with the king's deer and its forage was punished. However, the inhabitants of the area ('' commoners'') had pre-existing ''rights of common'': to turn horses and cattle (but only rarely sheep) out into the Forest to graze (''common pasture''), to gather fuel wood (''estovers

In English law, an estover is an allowance made to a person out of an estate, or other thing, for his or her support. The word estover can also mean specifically an allowance of wood that a tenant is allowed to take from the commons, for life o ...

''), to cut peat for fuel (''turbary

Turbary is the ancient right to cut turf, or peat, for fuel on a particular area of bog. The word may also be used to describe the associated piece of bog or peatland and, by extension, the material extracted from the turbary. Turbary rights, whic ...

''), to dig clay (''marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part o ...

''), and to turn out pigs between September and November to eat fallen acorn

The acorn, or oaknut, is the nut of the oaks and their close relatives (genera ''Quercus'' and '' Lithocarpus'', in the family Fagaceae). It usually contains one seed (occasionally

two seeds), enclosed in a tough, leathery shell, and borne ...

s and beechnuts (''pannage

Pannage (also referred to as ''Eichelmast'' or ''Eckerich'' in Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Austria, Slovenia and Croatia) is the practice of releasing livestock-domestic pig, pigs in a forest, so that they can feed on falle ...

'' or ''mast''). There were also licences granted to gather bracken

Bracken (''Pteridium'') is a genus of large, coarse ferns in the family Dennstaedtiaceae. Ferns (Pteridophyta) are vascular plants that have alternating generations, large plants that produce spores and small plants that produce sex cells (eggs ...

after Michaelmas Day

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christianity, Christian festival observed in some Western liturgical year, liturgica ...

(29 September) as litter for animals (''fern'').

Along with grazing, pannage is still an important part of the Forest's ecology. Pigs can eat acorns without problem, but for ponies and cattle, large quantities of acorns can be poisonous. Pannage always lasts at least 60 days, but the start date varies according to the weather – and when the acorns fall. The verderers

Verderers are forestry officials in England who deal with common land in certain former royal hunting areas which are the property of the Crown. The office was developed in the Middle Ages to administer forest law on behalf of the King. Verderers ...

decide when pannage will start each year. At other times the pigs must be taken in and kept on the owner's land, with the exception that pregnant sows, known as ''privileged sows'', are always allowed out providing they are not a nuisance and return to the Commoner's holding at night (they must not be "''levant'' and ''couchant''" in the Forest, that is, they may not consecutively feed ''and'' sleep there). This last is an established practice rather than a formal right.

The principle of levancy and couchancy applies generally to the right of pasture. Commoners must have backup land, outside the Forest, to accommodate these depastured animals when necessary, for example during a foot-and-mouth disease

Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) or hoof-and-mouth disease (HMD) is an infectious and sometimes fatal viral disease that affects cloven-hoofed animals, including domestic and wild bovids. The virus causes a high fever lasting two to six days, followe ...

epidemic.

Commons rights are attached to particular plots of land (or in the case of turbary, to particular hearth

A hearth () is the place in a home where a fire is or was traditionally kept for home heating and for cooking, usually constituted by at least a horizontal hearthstone and often enclosed to varying degrees by any combination of reredos (a lo ...

s), and different land has different rights – and some of this land is some distance from the Forest itself. Rights to graze ponies and cattle are not for a fixed number of animals, as is often the case on other commons. Instead a "marking fee" is paid for each animal each year by the owner. The marked animal's tail is trimmed by the local agister (verderers' official), with each of the four or five forest agisters using a different trimming pattern. Ponies are branded with the owner's brand mark; cattle may be branded, or nowadays may have the brand mark on an ear tag. Grazing of Commoners' ponies and cattle is an essential part of the management of the forest, helping to maintain the heathland, bog, grassland and wood-pasture habitats and their associated wildlife.

Recently this ancient practice has come under pressure as benefitting houses pass to owners with no interest in commoning. Existing families with a new generation heavily rely on inheritance of, rather than mostly the expensive purchase of, a benefitting house with paddock or farm.

The Verderers and Commoners' Defence Association has fought back against these allied economic threats. The EU Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) helped some Commoners significantly. Commoners marking animals for grazing can claim about £200 per cow per year, and about £160 for a pony, and if participating in the stewardship scheme, more. With 10 cattle and 40 ponies, a Commoner qualifying for both schemes would receive over £8,000 a year, and more if they put out pigs: net of marking fees, feed and veterinary costs this part-time level of involvement across a family is calculated to give annual income in the thousands of pounds in most years. Whether those subsidies will survive Brexit

Brexit (; a portmanteau of "British exit") was the withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU) at 23:00 GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February 2020 CET).The UK also left the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC or ...

is unclear. The BPS payment is based on the number of animals marked for the Forest, whether or not these are actually turned out. The livestock actually grazing the Forest are therefore considerably fewer than those marked.

Geography

The New Forest National Park area covers , and the New Forest

The New Forest National Park area covers , and the New Forest SSSI

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle of ...

covers almost , making it the largest contiguous area of unsown vegetation in lowland Britain. It includes roughly:

* of broadleaved woodland

* of heathland and grassland

* of wet heathland

* of tree plantations (''woodland inclosures'') established since the 18th century, including planted by Forestry England since the 1920s.

The New Forest has also been classed as National Character Area No. 131 by Natural England. The NCA covers an area of and is bounded by the Dorset Heaths

The Dorset Heaths form an important area of heathland within the Poole Basin in southern England. Much of the area is protected.

Extent

According to Natural England, who have designated the Dorset Heaths as National Character Area 135, th ...

and Dorset Downs

The Dorset Downs are an area of chalk downland in the centre of the county Dorset in south west England. The downs are the most western part of a larger chalk formation which also includes (from west to east) Cranborne Chase, Salisbury Plain, Ham ...

to the west, the West Wiltshire Downs

The West Wiltshire Downs is an area of downland in the west of the county of Wiltshire, England.

The West Wiltshire Downs are geologically the same unit as Salisbury Plain to the north and Cranborne Chase to the south.

The West Wiltshire Downs a ...

to the north and the South Hampshire Lowlands

The South Hampshire Lowlands form a natural landscape in south, central England within the county of Hampshire.

The UK Government's advisors on the natural environment, Natural England, have named the South Hampshire Lowlands as one of their Nat ...

and South Coast Plain

The South Coast Plain is a natural region in England running along the central south coast in the counties of East Sussex, East and West Sussex and Hampshire.

It has been designated as National Character Area No. 126 by Natural England. The NCA h ...

to the east.

The New Forest is drained to the south by three rivers, Lymington River

The Lymington River drains part of the New Forest in Hampshire in southern England. Numerous headwaters to the west of Lyndhurst give rise to the river, including Highland Water, Bratley Water and Fletchers Water. From Brockenhurst the river r ...

, Beaulieu River and Avon Water, and to the west by the Latchmore Brook

The Latchmore Brook is a significant stream in the New Forest, Hampshire, England. It rises from the elevated gravel plateaus in the north of the Forest, north of Fritham, and drains into the River Avon north of Ibsley.

The stream's catchment ...

, Dockens Water, Linford Brook and other streams.

The highest point in the New Forest is Pipers Wait, near Nomansland. Its summit is above sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as ''orthometric heights''.

The comb ...

.

The Geology of the New Forest consists mainly of sedimentary rock, in the centre of a sedimentary basin known as the Hampshire Basin.

Wildlife

The ecological value of the New Forest is enhanced by the relatively large areas of lowland habitats, lost elsewhere, which have survived. There are several kinds of important lowland habitat includingvalley bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; a ...

s, alder carr, wet heaths, dry heaths and deciduous woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

. The area contains a profusion of rare wildlife, including the New Forest cicada ''Cicadetta montana

''Cicadetta montana'' (also known as the New Forest cicada) is a species of '' Cicadetta'' found throughout Europe and in parts of Asia.

It is regarded as endangered over large parts of Europe, and has vanished from several areas in Western Eu ...

'', the only cicada native to Great Britain, although the last unconfirmed sighting was in 2000. The wet heaths are important for rare plants, such as marsh gentian (''Gentiana pneumonanthe

''Gentiana pneumonanthe'', the marsh gentian, is a species of the genus ''Gentiana

''Gentiana'' is a genus of flowering plants belonging to the gentian family (Gentianaceae), the tribe Gentianeae, and the monophyletic subtribe Gentianinae. ...

'') and marsh clubmoss (''Lycopodiella inundata

''Lycopodiella inundata'' is a species of club moss known by the common names inundated club moss, marsh clubmoss and northern bog club moss. It has a circumpolar and circumboreal distribution, occurring throughout the northern Northern Hemisphe ...

'') and other important species include the wild gladiolus (''Gladiolus illyricus

''Gladiolus illyricus'', the wild gladiolus, is a tall gladiolus plant that grows up to tall found in western and southern Europe, particularly around the Mediterranean region.

In Britain a small population is known in the New Forest

The ...

'').

Several species of sundew are found, as well as many unusual insect species, including the southern damselfly ('' Coenagrion mercuriale''), large marsh grasshopper ('' Stethophyma grossum'') and the mole cricket ('' Gryllotalpa gryllotalpa''), all rare in Britain. In 2009, 500 adult southern damselflies were captured and released in the Venn Ottery nature reserve in Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

, which is owned and managed by the Devon Wildlife Trust. The Forest is an important stronghold for a rich variety of fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

, and although these have been heavily gathered in the past, there are control measures now in place to manage this.

Birds

Specialist heathland birds are widespread, including Dartford warbler (''Curruca undata''), woodlark (''Lullula arborea''),northern lapwing

The northern lapwing (''Vanellus vanellus''), also known as the peewit or pewit, tuit or tew-it, green plover, or (in Ireland and Britain) pyewipe or just lapwing, is a bird in the lapwing subfamily. It is common through temperate Eurosiberia. ...

(''Vanellus vanellus''), Eurasian curlew

The Eurasian curlew or common curlew (''Numenius arquata'') is a very large wader in the family Scolopacidae. It is one of the most widespread of the curlews, breeding across temperate Europe and Asia. In Europe, this species is often referred t ...

(''Numenius arquata''), European nightjar (''Caprimulgus europaeus''), Eurasian hobby

The Eurasian hobby (''Falco subbuteo'') or just hobby, is a small, slim falcon. It belongs to a rather close-knit group of similar falcons often considered a subgenus '' Hypotriorchis''.

Taxonomy and systematics

The first formal description of ...

(''Falco subbuteo''), European stonechat

The European stonechat (''Saxicola rubicola'') is a small passerine bird that was formerly classed as a subspecies of the common stonechat. Long considered a member of the thrush family, Turdidae, genetic evidence has placed it and its relativ ...

(''Saxicola rubecola''), common redstart

The common redstart (''Phoenicurus phoenicurus''), or often simply redstart, is a small passerine bird in the genus ''Phoenicurus''. Like its relatives, it was formerly classed as a member of the thrush family, (Turdidae), but is now known to be ...

(''Phoenicurus phoenicurus'') and tree pipit (''Anthus sylvestris''). As in much of Britain common snipe (''Gallinago gallinago'') and meadow pipit (''Anthus trivialis'') are common as wintering birds, but in the Forest they still also breed in many of the bogs and heaths respectively.

Woodland birds include wood warbler (''Phylloscopus sibilatrix''), stock dove

The stock dove (''Columba oenas'') is a species of bird in the family Columbidae, the doves and pigeons. It is widely distributed in the western Palearctic.

Taxonomy

The stock dove was first formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Li ...

(''Columba oenas''), European honey buzzard

The European honey buzzard (''Pernis apivorus''), also known as the pern or common pern, is a bird of prey in the family Accipitridae.

Etymology

Despite its English name, this species is more closely related to kites of the genera '' Leptodon'' a ...

(''Pernis apivorus'') and northern goshawk

The northern goshawk (; ''Accipiter gentilis'') is a species of medium-large bird of prey, raptor in the Family (biology), family Accipitridae, a family which also includes other extant diurnal raptors, such as eagles, buzzards and harrier (bird) ...

(''Accipiter gentilis''). Common buzzard

The common buzzard (''Buteo buteo'') is a medium-to-large bird of prey which has a large range. A member of the genus ''Buteo'', it is a member of the family Accipitridae. The species lives in most of Europe and extends its breeding range across ...

(''Buteo buteo'') is very common and common raven

The common raven (''Corvus corax'') is a large all-black passerine bird. It is the most widely distributed of all corvids, found across the Northern Hemisphere. It is a raven known by many names at the subspecies level; there are at least e ...

(''Corvus corax'') is spreading. Birds seen more rarely include red kite (''Milvus milvus''), wintering great grey shrike (''Lanius exubitor'') and hen harrier

The hen harrier (''Circus cyaneus'') is a bird of prey. It breeds in Eurasia. The term "hen harrier" refers to its former habit of preying on free-ranging fowl.

It migrates to more southerly areas in winter. Eurasian birds move to southern Eur ...

(''Circus cyaneus'') and migrating ring ouzel (''Turdus torquatus'') and northern wheatear (''Oenanthe oenanthe'').

Reptiles and amphibians

All three British native species of snake inhabit the Forest. The adder (''

All three British native species of snake inhabit the Forest. The adder (''Vipera berus

''Vipera berus'', the common European adderMallow D, Ludwig D, Nilson G. (2003). ''True Vipers: Natural History and Toxinology of Old World Vipers''. Malabar, Florida: Krieger Publishing Company. . or common European viper,Stidworthy J. (1974). ...

'') is the most common, being found on open heath and grassland. The grass snake (''Natrix natrix'') prefers the damper environment of the valley mires. The rare smooth snake (''Coronella austriaca

The smooth snake (''Coronella austriaca'')Street D (1979). ''The Reptiles of Northern and Central Europe''. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd. 268 pp. . is a species of non-venomous snake in the family Colubridae. The species is found in northern and ce ...

'') occurs on sandy hillsides with heather and gorse

''Ulex'' (commonly known as gorse, furze, or whin) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Fabaceae. The genus comprises about 20 species of thorny evergreen shrubs in the subfamily Faboideae of the pea family Fabaceae. The species are n ...

. It was mainly adders which were caught by Brusher Mills

Harry 'Brusher' Mills (19 March 1840 – 1 July 1905) was a hermit, resident in the New Forest in Hampshire, England, who made his living as a snake-catcher. He became a local celebrity and an attraction for visitors to the New Forest.

Life

...

(1840–1905), the "New Forest Snake Catcher". He caught many thousands in his lifetime, sending some to London Zoo

London Zoo, also known as ZSL London Zoo or London Zoological Gardens is the world's oldest scientific zoo. It was opened in London on 27 April 1828, and was originally intended to be used as a collection for science, scientific study. In 1831 o ...

as food for their animals. A pub

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and was ...

in Brockenhurst is named ''The Snakecatcher'' in his memory. All British snakes are now legally protected, and so the New Forest snakes are no longer caught.

A programme to reintroduce the sand lizard (''Lacerta agilis'') started in 1989 and the great crested newt (''Triturus cristatus'') already breeds in many locations.

Sand lizards in a captive breeding and reintroduction programme together with adders, grass snakes, smooth snakes, frogs and toads can be seen at The New Forest Reptile Centre A reptile centre (or reptile center) is typically a facility devoted to keeping living reptiles, educating the public about reptiles, and serving as a control centre for collecting reptiles that turn up in populated areas. Most are public-access, r ...

about two miles east of Lyndhurst. The centre was established in 1969 by Derek Thomson MBE Mbe may refer to:

* Mbé, a town in the Republic of the Congo

* Mbe Mountains Community Forest, in Nigeria

* Mbe language, a language of Nigeria

* Mbe' language, language of Cameroon

* ''mbe'', ISO 639 code for the extinct Molala language

Molal ...

, a Forestry England keeper, who was also involved in establishing the deer viewing platform at nearby Bolderwood.

Ponies, cattle, donkeys, pigs

Commoners' cattle, ponies and donkeys roam throughout the open heath and much of the woodland, and it is largely their grazing that maintains the open character of the Forest. They are also frequently seen in the Forest villages, where home and shop owners must take care to keep them out of gardens and shops. The

Commoners' cattle, ponies and donkeys roam throughout the open heath and much of the woodland, and it is largely their grazing that maintains the open character of the Forest. They are also frequently seen in the Forest villages, where home and shop owners must take care to keep them out of gardens and shops. The New Forest pony

The New Forest pony is one of the recognised mountain and moorland or native pony breeds of the British Isles. Height varies from around ; ponies of all heights should be strong, workmanlike, and of a good riding type. They are valued for hardi ...

is one of the indigenous horse breeds of the British Isles, and is one of the New Forest's most famous attractions – most of the Forest ponies are of this breed, but there are also some Shetlands

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the ...

and their crossbreed

A crossbreed is an organism with purebred parents of two different breeds, varieties, or populations. ''Crossbreeding'', sometimes called "designer crossbreeding", is the process of breeding such an organism, While crossbreeding is used to main ...

s.

Cattle are of various breeds, most commonly Galloways and their crossbreeds, but also various other hardy types such as Highlands, Herefords, Dexters, Kerries and British white

The British White is a naturally polled British cattle breed, white with black or red points, used mainly for beef. It has a confirmed history dating back to the 17th century.

Characteristics

The British White has shortish white hair, and h ...

s. The pigs used for pannage

Pannage (also referred to as ''Eichelmast'' or ''Eckerich'' in Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Austria, Slovenia and Croatia) is the practice of releasing livestock-domestic pig, pigs in a forest, so that they can feed on falle ...

, during the autumn months, are now of various breeds, but the New Forest was the original home of the Wessex Saddleback

The Wessex Saddleback or Wessex Pig is a breed of domestic pig originating in the West Country of England, (Wessex), especially in Wiltshire and the New Forest area of Hampshire. It is black, with white forequarters. In Britain it was amalgamated ...

, now extinct in Britain.

Deer

Numerous deer live in the Forest; they are usually rather shy and tend to stay out of sight when people are around, but are surprisingly bold at night, even when a car drives past. Fallow deer (''Dama dama'') are the most common, followed byroe deer

The roe deer (''Capreolus capreolus''), also known as the roe, western roe deer, or European roe, is a species of deer. The male of the species is sometimes referred to as a roebuck. The roe is a small deer, reddish and grey-brown, and well-adapt ...

(''Capreolus capreolus'') and red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or hart, and a female is called a hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, and parts of wes ...

(''Cervus elaphus''). There are also smaller populations of the introduced sika deer (''Cervus nippon'') and muntjac

Muntjacs ( ), also known as the barking deer or rib-faced deer, (URL is Google Books) are small deer of the genus ''Muntiacus'' native to South Asia and Southeast Asia. Muntjacs are thought to have begun appearing 15–35 million years ago, ...

(''Muntiacus reevesii'').

Other mammals

Thered squirrel

The red squirrel (''Sciurus vulgaris'') is a species of tree squirrel in the genus ''Sciurus'' common throughout Europe and Asia. The red squirrel is an arboreal, primarily herbivorous rodent.

In Great Britain, Ireland, and in Italy numbers ...

(''Sciurus vulgaris'') survived in the Forest until the 1970s – longer than most places in lowland Britain (though it still occurs on The Isle of Wight and the nearby Brownsea Island). It is now fully supplanted in the Forest by the introduced North American grey squirrel (''Sciurus carolinensis''). The European polecat

The European polecat (''Mustela putorius''), also known as the common polecat, black polecat, or forest polecat, is a species of mustelid native to western Eurasia and North Africa. It is of a generally dark brown colour, with a pale underbelly ...

(''Mustela putorius'') has recolonised the western edge of the Forest in recent years. European otter

The Eurasian otter (''Lutra lutra''), also known as the European otter, Eurasian river otter, common otter, and Old World otter, is a semiaquatic mammal native to Eurasia. The most widely distributed member of the otter subfamily (Lutrinae) of th ...

(''Lutra lutra'') occurs along watercourses, as well as the introduced American mink (''Neogale vison'').

Conservation measures

The New Forest is designated as aSite of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle of ...

(SSSI), an EU Special Area of Conservation (SAC), a Special Protection Area for birds (SPA), and a Ramsar Site

A Ramsar site is a wetland site designated to be of international importance under the Ramsar Convention,8 ha (O)

*** Permanent 8 ha (P)

*** Seasonal Intermittent < 8 ha(Ts)

**

Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP).

Consultations on the possible designation of a

Consultations on the possible designation of a

* Bolderwood

*

* Bolderwood

*

The Official New Forest Tourism Website , Information on visiting the National ParkNew Forest National Park AuthorityNew Forest , Forestry EnglandNew Forest Gateway – Film, TV, Picture Resource / Historical Book Publications OnlineSAC designation including extensive technical description of habitats and species

*Designation as a national park:

(

New Forest National Park becomes a reality

(

The New Forest National Park

( Countryside Agency press release, 1 March 2005)

New Forest National Park Inquiry

from the

Maps of the boundary

* {{SSSIs Wilts biological 1079 establishments in England English royal forests Forests and woodlands of Hampshire Forests and woodlands of Wiltshire Heathland Sites of Special Scientific Interest National parks in England Nature Conservation Review sites New Forest District Parks and open spaces in Hampshire Parks and open spaces in Wiltshire Protected areas established in 2005 Ramsar sites in England Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Hampshire Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Wiltshire South East England Special Areas of Conservation in England Woodland Sites of Special Scientific Interest Natural regions of England William the Conqueror

Settlements

The New Forest itself gives its name to theNew Forest district

New Forest is a local government district in Hampshire, England. Its council is based in Lyndhurst. The district covers most of the New Forest National Park, from which it takes its name.

The district was created on 1 April 1974, under the Loca ...

of Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

, and the National Park area, of which it forms the core.

The Forest itself is dominated by four larger 'defined' villages, Sway

Sway may refer to:

Places

* Sway, Hampshire, a village and civil parish in the New Forest in England

** Sway railway station, serving the village

People

* Sway (British musician) (born 1983), British hip hop/grime singer

* Sway Calloway (born 1 ...

, Brockenhurst, Lyndhurst and Ashurst, with several smaller villages such as Burley, Beaulieu, Godshill

Godshill is a village and civil parish on the Isle of Wight, England, with a population of 1,459 at the 2011 Census. It lies between Newport and Ventnor in the southeast of the island.

History

Godshill is one of the ancient parishes that exis ...

, Fritham

Fritham is a small village in Hampshire, England. It lies in the north of the New Forest, near the Wiltshire border. It is in the civil parish of Bramshaw.

History

The name Fritham may be derived from Old English meaning a cultivated plot (''ham ...

, Nomansland, and Minstead also lying within or immediately adjacent. Outside of the National Park Area in New Forest District, several clusters of larger towns frame the area – Totton and the Waterside settlements ( Marchwood, Dibden

Dibden is a small village in Hampshire, England, which dates from the Middle Ages. It is dominated by the nearby settlements of Hythe and Dibden Purlieu. It is in the civil parish of Hythe and Dibden. It lies on the eastern edge of the New Fo ...

, Hythe

Hythe, from Anglo-Saxon ''hȳð'', may refer to a landing-place, port or haven, either as an element in a toponym, such as Rotherhithe in London, or to:

Places Australia

* Hythe, Tasmania

Canada

*Hythe, Alberta, a village in Canada

England

* T ...

, Fawley) to the East, Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon River / ...

, New Milton

New Milton is a market town in southwest Hampshire, England. To the north is in the New Forest and to the south the coast at Barton-on-Sea. The town is equidistant between Lymington and Christchurch, 6 miles (10 km) away.

History

Ne ...

, Milford on Sea, and Lymington to the South, and Fordingbridge and Ringwood to the West.

New Forest National Park

National Park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

in the New Forest were commenced by the Countryside Agency in 1999. An order to create the park was made by the Agency on 24 January 2002 and submitted to the Secretary of State for confirmation in February 2002. Following objections from seven local authorities and others, a public inquiry

A tribunal of inquiry is an official review of events or actions ordered by a government body. In many common law countries, such as the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, Australia and Canada, such a public inquiry differs from a royal ...

was held from 8 October 2002 to 10 April 2003, and concluded by endorsing the proposal with some detailed changes to the boundary of the area to be designated.

On 28 June 2004, Rural Affairs Minister Alun Michael

Alun Edward Michael (born 22 August 1943) is a Welsh Labour politician serving as South Wales Police and Crime Commissioner since 2012. He served as Secretary of State for Wales from 1998 to 1999 and then as the first First Secretary of Wales ...

confirmed the government's intention to designate the area as a National Park, with further detailed boundary adjustments. The area was formally designated as such on 1 March 2005. A national park authority

A national park authority is a special term used in Great Britain for legal bodies charged with maintaining a national park of which, as of October 2021, there are ten in England, three in Wales and two in Scotland. The powers and duties of all suc ...

for the New Forest was established on 1 April 2005 and assumed its full statutory powers on 1 April 2006.

Forestry England

Forestry England is a division of the Forestry Commission, responsible for managing and promoting publicly owned forests in England. It was formed as Forest Enterprise in 1996, before devolving to Forest Enterprise England on 31 March 2003 and ...

retain their powers to manage the Crown land within the Park. The Verderers under the New Forest Acts also retain their responsibilities, and the park authority is expected to co-operate with these bodies, the local authorities, English Nature and other interested parties.

The designated area of the National Park covers and includes many existing SSSI

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle of ...

s. It has a population of about 38,000 (it excludes most of the 170,256 people who live in the New Forest local government district). As well as most of the New Forest district

New Forest is a local government district in Hampshire, England. Its council is based in Lyndhurst. The district covers most of the New Forest National Park, from which it takes its name.

The district was created on 1 April 1974, under the Loca ...

of Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

, it takes in the South Hampshire Coast

The South Hampshire Coast was an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in Hampshire, England, UK that was subsumed into the New Forest National Park when it was established on 1 April 2005. It lies between the New Forest and the west shore o ...

Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, a small corner of Test Valley district around the village of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

and part of Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

south-east of Redlynch.

However, the area covered by the Park does not include all the areas initially proposed: it excludes most of the valley of the River Avon to the west of the Forest and Dibden Bay

Dibden Bay is a biological Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) between Marchwood and Hythe in Hampshire.

Most of this site was formed by deposition of material dredged from Southampton Water. It has been designated an SSSI because it has ...

to the east. Two challenges were made to the designation order, by Meyrick Estate Management Ltd in relation to the inclusion of Hinton Admiral Park, and by RWE

RWE AG is a German multinational energy company headquartered in Essen. It generates and trades electricity in Asia-Pacific, Europe and the United States. The company is Europe's most climate threatening Company, the world's number two in offsh ...

NPower Plc in relation to the inclusion of Fawley Power Station. The second challenge was settled out of court, with the power station being excluded. The High Court upheld the first challenge; but an appeal against the decision was then heard by the Court of Appeal

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of t ...

in Autumn 2006. The final ruling, published on 15 February 2007, found in favour of the challenge by Meyrick Estate Management Ltd, and the land at Hinton Admiral Park is therefore excluded from the New Forest National Park. The total area of land initially proposed for inclusion but ultimately left out of the Park is around .

Visitor attractions and places

* Bolderwood

*

* Bolderwood

*Bucklers Hard

Buckler's Hard is a hamlet on the banks of the Beaulieu River in the English county of Hampshire. With its Georgian cottages running down to the river, Buckler's Hard is part of the Beaulieu Estate. The hamlet is some south of the village of ...

* Beaulieu

* Exbury Gardens

* Hythe Pier

* Lymington

*New Forest Show

The New Forest and Hampshire County Show, or more commonly known as the New Forest Show, is an annual agricultural show event held for three days at the end of July in New Park, near Brockenhurst in Hampshire, southern England, UK. The first N ...

*New Forest Tour

The New Forest Tour is an open-top bus service in the New Forest, running three circular routes around various towns, attractions and villages in the protected forest. It is run by morebus and Bluestar in partnership with Hampshire County Counci ...

* New Forest Wildlife Park

Politics

The New Forest is represented by twoMembers of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

; in New Forest East and New Forest West

New Forest West is a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the UK Parliament since 1997 by Desmond Swayne, a Conservative.

Constituency profile

This constituency covers the part of the New Forest which is not covered by New Fo ...

.

Cultural references

There is an allusion to the foundation of the New Forest in an end-rhyming poem found in thePeterborough Chronicle

The ''Peterborough Chronicle'' (also called the Laud manuscript and the E manuscript) is a version of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicles'' originally maintained by the monks of Peterborough Abbey in Cambridgeshire. It contains unique information abo ...

's entry for 1087, ''The Rime of King William

"The Rime of King William" is an Old English poem that tells the death of William the Conqueror. The Rime was a part of the only entry for the year of 1087 (though improperly dated 1086) in the "Peterborough Chronicle/Laud Manuscript." In this e ...

''.

The Forest forms a backdrop to numerous books. '' The Children of the New Forest'' is a children's novel published in 1847 by Frederick Marryat, set in the time of the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the working ...

's ''A New Forest Ballad'' (1847) mentions several New Forest locations, including Ocknell Plain, Bradley ratley

Ratley is a village in the civil parish of Ratley and Upton, Stratford-on-Avon District, Warwickshire, England. The population of the civil parish in 2011 was 327. It is on the northwest side of the Edge Hill escarpment about above sea level. T ...

Water, Burley Walk and Lyndhurst churchyard. Edward Rutherfurd

Edward Rutherfurd is a pen name for Francis Edward Wintle (born in 1948). He is best known as a writer of epic historical novels that span long periods of history but are set in particular places. His debut novel, '' Sarum'', set the pattern f ...

's work of historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

, '' The Forest'' is based in the New Forest in the period from 1099 to 2000. The Forest is also a setting of the ''Warriors'' novel series, in which the 'Forest Territories' was initially based on New Forest.

The New Forest and southeast England, around the 12th century, is a prominent setting in Ken Follett

Kenneth Martin Follett, (born 5 June 1949) is a British author of thrillers and historical novels who has sold more than 160 million copies of his works.

Many of his books have achieved high ranking on best seller lists. For example, in the ...

's novel ''The Pillars of the Earth

''The Pillars of the Earth'' is a historical novel by British author Ken Follett published in 1989 about the building of a cathedral in the fictional town of Kingsbridge, England. Set in the 12th century, the novel covers the time between the ...

''. It is also a prominent setting in Elizabeth George's novel ''This Body of Death''. Oberon, Titania and the other Shakespearean fairies live in a rapidly diminishing Sherwood Forest whittled away by urban development in the fantasy novel A Midsummer's Nightmare by Garry Kilworth. On Midsummer's Eve, a most auspicious day, the fairies embark on the long journey to the New Forest in Hampshire where the fairies' magic will be restored to its former glory.

Notable residents

*Eric Ashby

Eric Ashby, Baron Ashby, FRS (24 August 1904 – 22 October 1992) was a British botanist and educator.

Born in Leytonstone in Essex, he was educated at the City of London School and the Royal College of Science, where he graduated with a ...

(1918–2003), naturalist and wildlife cameraman

*Alice Bentinck

Alice Yvonne Bentinck (born 23 July 1986) is a British entrepreneur. Along with Matt Clifford, she is the co-founder of Entrepreneur First, a London-based company builder and startup accelerator. Based in London and Singapore, EF funds ambitiou ...

(born 1986), co-founder and COO

COO or coo may refer to:

Business

* Certificate of origin, used in international trade

* Chief operating officer or chief operations officer, high-ranking corporate official

* Concept of operations, used in Systems Engineering Management Process

...

of Entrepreneur First

Entrepreneur First is an international talent investor, which supports individuals in building technology companies. Founded in 2011 by Matt Clifford and Alice Bentinck, the company has offices in Toronto, London, Berlin, Paris, Singapore, and ...

, London

*William Arnold Bromfield

William Arnold Bromfield (1801–1851), was an English botanist.

Bromfield was born at Boldre, in the New Forest, Hampshire, in 1801, his father, the Rev. John Arnold Bromfield, dying in the same year. He received his early training under Dr. K ...

(1801–1851), English botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

* Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1869–1930), author

*Harry Warner Farnall

Harry Warner Farnall (18 December 1838 – 5 June 1891) was a New Zealand politician, emigration agent and labour reformer. He was a Member of Parliament from Auckland.

He was born in Burley Park, Hampshire, England, on 18 December 1838.

He ...

(1838–1891), New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

politician

* Gerald Gardner (1884–1964), founder of Gardnerian Wicca

*Steff Gaulter

Steff Gaulter (born 1976 in Sway, Hampshire) is an English weather forecaster for Al Jazeera English.

Gaulter won a place at University of Cambridge in 1994 where she was awarded an MA in Physics, gaining the University's top marks for the fin ...

(born 1976), weather forecaster

*Pam Gems

Pam Gems (1 August 1925 – 13 May 2011) was an English playwright. The author of numerous original plays, as well as of adaptations of works by European playwrights of the past, Gems is best known for the 1978 musical play '' Piaf''.

Personal ...

(1925–2011), English playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

*Arthur Sumner Gibson

Arthur Sumner Gibson (14 July 1844 – 23 January 1927) was a rugby union international who represented England in 1871 in the first international match.

Early life

Gibson was born at Fawley, near Southampton on 14 July 1844 and baptised the ...

(1844–1927), rugby union

Rugby union, commonly known simply as rugby, is a close-contact team sport that originated at Rugby School in the first half of the 19th century. One of the two codes of rugby football, it is based on running with the ball in hand. In its m ...

international

*Edgar Gibson

Edgar Charles Sumner Gibson (23 January 1848, Fawley, Hampshire, England - 8 March 1924, Fareham) was the 31st Bishop of Gloucester. He was born into a clerical family. His father was a clergyman and his son Theodore Sumner Gibson was a long serv ...

(1848–1924), 31st Bishop of Gloucester

* Clifford Hall (1902–1982), English cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

er

* Frederick Harold (1888–1964), English cricketer

* Gerry Hill (1913–2006), English cricketer

*Ralph Hollins

J. R. W. (Ralph) Hollins (born 1931) is a naturalist, born at Martin in the English county of Hampshire.

Hollins became active in Hampshire Wildlife Trust and Hampshire Ornithological Society during the 1980s, serving on committees of both organi ...

(born 1931), naturalist

*Mark Kermode

Mark James Patrick Kermode (, ; ; born 2 July 1963) is an English film critic, musician, radio presenter, television presenter and podcaster. He is the chief film critic for ''The Observer'', contributes to the magazine ''Sight & Sound'', prese ...

(born 1963), film critic

Film criticism is the analysis and evaluation of films and the film medium. In general, film criticism can be divided into two categories: journalistic criticism that appears regularly in newspapers, magazines and other popular mass-media outlets ...

and musician

A musician is a person who composes, conducts, or performs music. According to the United States Employment Service, "musician" is a general term used to designate one who follows music as a profession. Musicians include songwriters who wri ...

*Sybil Leek

Sybil Leek (''née'' Fawcett; 22 February 1917 – 26 October 1982) was an English witch, astrologer, occult author and self-proclaimed psychic. She wrote many books on occult and esoteric subjects, and was dubbed "Britain's most famous witch ...

(1917–1982), witch, author, astrologer

*Sir Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

(1797–1875), Victorian geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

and polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

*Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during t ...

(1820–1910), nurse

* Chris Packham (born 1961), naturalist and broadcaster

References

Further reading

The following out-of-copyright books can be read online or downloaded: * * * Extracts from the above texts have been brought together by the New Forest author and cultural historianIan McKay

Ian John McKay, VC (7 May 1953 – 12 June 1982) was a British Army soldier and a posthumous recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

Bor ...

in his anthologies:

*

*

These anthologies also include writings by William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restrain foreign ...

, Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

, William Gilpin, William Howitt

William Howitt (18 December 1792 – 3 March 1879), was a prolific English writer on history and other subjects. Howitt Primary Community School in Heanor, Derbyshire, is named after him and his wife.

Biography

Howitt was born at Heanor, Derbysh ...

, W. H. Hudson

William Henry Hudson (4 August 1841 – 18 August 1922) – known in Argentina as Guillermo Enrique Hudson – was an English Argentines, Anglo-Argentine author, natural history, naturalist and ornithology, ornithologist.

Life

Hudson was the ...

, and Heywood Sumner.

*

External links

The Official New Forest Tourism Website , Information on visiting the National Park

*Designation as a national park:

(

DEFRA DEFRA may refer to:

* Deficit Reduction Act of 1984, United States law

* Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, United Kingdom government department

{{Disambiguation ...

press release, 28 June 2004)

New Forest National Park becomes a reality

(

DEFRA DEFRA may refer to:

* Deficit Reduction Act of 1984, United States law

* Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, United Kingdom government department

{{Disambiguation ...

press release, 24 February 2004)

The New Forest National Park

( Countryside Agency press release, 1 March 2005)

New Forest National Park Inquiry

from the

Planning Inspectorate

The Planning Inspectorate for England (sometimes referred to as PINS) is an executive agency of the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities of the United Kingdom Government with responsibility for making decisions and providing reco ...

Maps of the boundary

* {{SSSIs Wilts biological 1079 establishments in England English royal forests Forests and woodlands of Hampshire Forests and woodlands of Wiltshire Heathland Sites of Special Scientific Interest National parks in England Nature Conservation Review sites New Forest District Parks and open spaces in Hampshire Parks and open spaces in Wiltshire Protected areas established in 2005 Ramsar sites in England Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Hampshire Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Wiltshire South East England Special Areas of Conservation in England Woodland Sites of Special Scientific Interest Natural regions of England William the Conqueror