Montagu Stopford on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

/ref> In late October Stopford, by now a

/ref>Mead, p. 441

Mountbatten was not beaten and, upon returning to India, ordered Stopford to continue to train XXXIII Corps in amphibious operations, which it did so for the next months. In March 1944, however, the Japanese 15th Army, under

Mountbatten was not beaten and, upon returning to India, ordered Stopford to continue to train XXXIII Corps in amphibious operations, which it did so for the next months. In March 1944, however, the Japanese 15th Army, under  The initial defence of Kohima, therefore, was conducted by a far smaller force than was necessary. However, fighting in very grim conditions reminiscent of World War I, the force managed to hold on during a siege that lasted over two weeks, the British and Indian troops being boxed in on Garrison Hill. The distance between them and the Japanese was the length of the local District Commissioner's

The initial defence of Kohima, therefore, was conducted by a far smaller force than was necessary. However, fighting in very grim conditions reminiscent of World War I, the force managed to hold on during a siege that lasted over two weeks, the British and Indian troops being boxed in on Garrison Hill. The distance between them and the Japanese was the length of the local District Commissioner's  IV Corps had, at the same time, taken

IV Corps had, at the same time, taken  Confirmed in his rank of lieutenant general in April 1945, in late May Stopford's XXXIII Indian Corps HQ was redesignated as the new HQ British Twelfth Army. The Twelfth Army now took responsibility for finishing the final stages of the campaign in Burma, allowing the HQ Fourteenth Army to return to India, to plan for future operations, specifically the recapture of Malaya. The battle under Stopford's command would become known as the

Confirmed in his rank of lieutenant general in April 1945, in late May Stopford's XXXIII Indian Corps HQ was redesignated as the new HQ British Twelfth Army. The Twelfth Army now took responsibility for finishing the final stages of the campaign in Burma, allowing the HQ Fourteenth Army to return to India, to plan for future operations, specifically the recapture of Malaya. The battle under Stopford's command would become known as the

The Peerage.com

/ref> They had no children. His wife died on 4 October 1982.

, - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Stopford, Montagu 1892 births 1971 deaths Academics of the Staff College, Camberley British Army generals of World War II British Army personnel of World War I Commandants of the Staff College, Camberley Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Deputy Lieutenants of Oxfordshire Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Military personnel from London People educated at Wellington College, Berkshire People from Mayfair Recipients of the Military Cross Rifle Brigade officers British Army generals Montagu Burials in Oxfordshire

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Sir Montagu George North Stopford (16 November 1892 – 10 March 1971) was a senior British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," f ...

who fought during both World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. The latter he served in with distinction, commanding XXXIII Indian Corps in the Far East, where he served under Field Marshal Sir William Slim, and played a significant role in the Burma Campaign, specifically during the Battle of Kohima

The Battle of Kohima proved the turning point of the Japanese U-Go offensive into India in 1944 during the Second World War. The battle took place in three stages from 4 April to 22 June 1944 around the town of Kohima, now the capital city of N ...

in mid-1944.

Early life and First World War

Born on 16 November 1892 inHanover Square, London

Hanover Square is a green square in Mayfair, Westminster, south west of Oxford Circus where Oxford Street meets Regent Street. Six streets converge on the square which include Harewood Place with links to Oxford Street, Princes Street, Hanover ...

, Montagu Stopford was the son of Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

Sir Lionel Stopford, and the great-grandson of James Stopford, 3rd Earl of Courtown

James George Stopford, 3rd Earl of Courtown KP, PC (15 August 1765 – 15 June 1835), known as Viscount Stopford from 1770 to 1810, was an Anglo-Irish peer and Tory politician.

Courtown was the eldest son of James Stopford, 2nd Earl of Cou ...

. His mother was Mabel Georgina Emily, daughter of George Alexander Mackenzie. He was educated at Wellington College, Berkshire

Wellington College is a public school (English independent day and boarding school) in the village of Crowthorne, Berkshire, England. Wellington is a registered charity and currently educates roughly 1,200 pupils, between the ages of 13 a ...

and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC), founded in 1801 and established in 1802 at Great Marlow and High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, England, but moved in October 1812 to Sandhurst, Berkshire, was a British Army military academy for training infant ...

.Smart, p. 298 He was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort's Own)

The Rifle Brigade (The Prince Consort's Own) was an infantry rifle regiment of the British Army formed in January 1800 as the "Experimental Corps of Riflemen" to provide sharpshooters, scouts, and skirmishers. They were soon renamed the "Rifle ...

on 20 September 1911, His fellow graduates included Edward Williams, also of the Rifle Brigade, John Evetts, Eric Nares, and Kenneth Anderson, all of whom would, like Stopford himself, become general officers. He was posted to the 2nd Battalion of the regiment, then serving in Rawalpindi, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, until shortly after the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914.Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives/ref> In late October Stopford, by now a

lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

, arrived with his battalion in Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a populat ...

, having left India the month before. The battalion, now serving as part of the 25th Brigade of the 8th Division 8th Division, 8th Infantry Division or 8th Armored Division may refer to:

Infantry divisions

* 8th Division (Australia)

* 8th Canadian Infantry Division

* 8th Air Division (People's Republic of China)

* 8th Division (1st Formation) (People's Repu ...

, arrived on the Western Front in early November. After serving with his battalion throughout some of the most intense battles of 1915, including the Battle of Neuve Chapelle

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) took place in the First World War in the Artois region of France. The attack was intended to cause a rupture in the German lines, which would then be exploited with a rush to the Aubers Ridge a ...

, Stopford, promoted on 5 July 1915 to captain, became a General Staff Officer Grade 3 (GSO3) with the 56th (1st London) Division

The 56th (London) Infantry Division was a Territorial Army infantry division of the British Army, which served under several different titles and designations. The division served in the trenches of the Western Front during the First World War. ...

, a Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was a part-time volunteer component of the British Army, created in 1908 to augment British land forces without resorting to conscription. The new organisation consolidated the 19th-century Volunteer Force and yeomanry ...

(TF) formation, on 10 June 1916. On 6 December 1916 he became the brigade major

A brigade major was the chief of staff of a brigade in the British Army. They most commonly held the rank of major, although the appointment was also held by captains, and was head of the brigade's "G - Operations and Intelligence" section dire ...

of the 56th Division's 167th (1st London) Brigade

The 167th (1st London) Brigade was an infantry formation of the British Territorial Army that saw active service in both the First and Second World Wars. It was the first Territorial formation to go overseas in 1914, garrisoned Malta, and then s ...

, a post which he held throughout 1917 until 25 March 1918. He ended the war with the substantive rank of major, and had been twice mentioned in dispatches and awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC ...

.

Between the wars

Remaining in the army during the difficult interwar period, spent mainly on regimental duties, Stopford served in theBritish Army of the Rhine

There have been two formations named British Army of the Rhine (BAOR). Both were originally occupation forces in Germany, one after the First World War and the other after the Second World War. Both formations had areas of responsibility located ...

(BAOR), as Commanding Officer (CO) of the 53rd Battalion, Rifle Brigade. He then returned to England, where he attended the Staff College, Camberley, from 1923 to 1924. His fellow students there included Gordon Macready, Dudley Johnson, Douglas Pratt, John Smyth, Roderic Petre, Arthur Percival

Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival, (26 December 1887 – 31 January 1966) was a senior British Army officer. He saw service in the First World War and built a successful military career during the interwar period but is most noted fo ...

, Frederick Pile

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Frederick Alfred Pile, 2nd Baronet, (14 September 1884 – 14 November 1976) was a senior British Army officer who served in both World Wars. In the Second World War he was General Officer Commanding An ...

, Henry Verschoyle-Campbell, Robert Stone, John Halsted, Balfour Hutchison, Colville Wemyss, Rowley Hill, Kenneth Loch, Michael Gambier-Parry

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major-General Michael Denman Gambier-Parry (21 August 1891 – 30 April 1976) was a senior British Army Officer (armed forces), officer who briefly commanded the 2nd Armoured Division (United Kingdom), 2nd Armoure ...

, Alastair MacDougall, Arthur Wakely, Edmond Schreiber, Robert Pargiter and Sydney Muspratt, along with Horace Robertson

Lieutenant General Sir Horace Clement Hugh Robertson, (29 October 1894 – 28 April 1960) was a senior officer in the Australian Army who served in the First World War, the Second World War and the Korean War. He was one of the first graduates ...

of the Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (CA), wh ...

, and Harry Crerar

General Henry Duncan Graham Crerar (28 April 1888 – 1 April 1965) was a senior officer of the Canadian Army who became the country's senior field commander in the Second World War as commander of the First Canadian Army in the campaign in N ...

and Georges Vanier

Georges-Philias Vanier (23 April 1888 – 5 March 1967) was a Canadian military officer and diplomat who served as governor general of Canada, the first Quebecer and second Canadian-born person to hold the position.

Vanier was born and ...

of the Canadian Army

The Canadian Army (french: Armée canadienne) is the command responsible for the operational readiness of the conventional ground forces of the Canadian Armed Forces. It maintains regular forces units at bases across Canada, and is also res ...

. Nearly all of these men were, like Stopford himself, destined to become general officers in the near future. In February 1926 Stopford became a General Staff Officer at the Small Arms School at Hythe, Kent. On 1 July 1929 he was promoted to brevet rank of major.

In February 1930 Stopford was made a brigade major with the 11th Infantry Brigade. In May 1932 he was made a GSO2 to the Inspector General of the King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from Britain's various possessions in East Africa from 1902 until independence in the 1960s. It performed both military and internal security functions within ...

. Promoted to permanent major in January 1933, he was a brevet lieutenant colonel two years later. In January 1938, towards the end of the interwar period, Stopford returned to the Staff College, Camberley, this time with the role of Senior Instructor, and was promoted to colonel on 25 July (with seniority backdating to 12 January). In this position he came into contact with numerous other members of the Directing Staff who were to achieve high rank in the war which was believed to be inevitable. They were John Swayne, Brian Horrocks

Lieutenant-General Sir Brian Gwynne Horrocks, (7 September 1895 – 4 January 1985) was a British Army officer, chiefly remembered as the commander of XXX Corps in Operation Market Garden and other operations during the Second World W ...

, Alexander Galloway, Charles Allfrey, Francis Festing

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

*Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

*Rural Mu ...

, Charles Keightley

General Sir Charles Frederic Keightley, (24 June 1901 – 17 June 1974) was a senior British Army officer who served during and following the Second World War. After serving with distinction during the Second World War – becoming, in 1944, th ...

, Charles Loewen and Cameron Nicholson

General Sir Cameron Gordon Graham Nicholson, (30 June 1898 – 7 July 1979) was a British Army officer who served as Adjutant-General to the Forces. He later served as Governor of the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

Military career

After being educated ...

, along with the Commandant, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Sir Ronald Adam.Generals.dk/ref>Mead, p. 441

World War II

France and Belgium

Stopford was still there by the outbreak ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

in September 1939. However, just over a month later he was selected to command the 17th Infantry Brigade, then being formed in Aldershot, Hampshire for service overseas, and was promoted to the temporary rank of brigadier

Brigadier is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several thousand soldiers. I ...

. Comprising three Regular Army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standin ...

battalions formerly scattered around the United Kingdom, the brigade was serving under Aldershot Command until being sent to France, arriving there on 19 October, as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). There the brigade served briefly under General Headquarters (GHQ) BEF before passing to the control of II Corps, whose General Officer Commanding (GOC), Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Sir Alan Brooke, had been one of Stopford's instructors at the Staff College, Camberley in the 1920s and thought highly of his capabilities. In December the brigade was transferred again, to the 4th Division under Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Dudley Johnson (who had been one of Stopford's fellow students at the Staff College), before, towards the end of the month, coming under the command of Major General Harold Franklyn

General Sir Harold Edmund Franklyn, (28 November 1885 − 31 March 1963) was a British Army officer who fought in both the First and the Second World Wars. He is most notable for his command of the 5th Infantry Division during the Battle of F ...

's 5th Division In military terms, 5th Division may refer to:

Infantry divisions

* 5th Division (Australia)

*5th Division (People's Republic of China)

* 5th Division (Colombia)

*Finnish 5th Division (Continuation War)

* 5th Light Cavalry Division (France)

*5th Mo ...

. In addition to Stopford's 17th Brigade, the division had the 13th Brigade under Brigadier Miles Dempsey

General Sir Miles Christopher Dempsey, (15 December 1896 – 5 June 1969) was a senior British Army officer who served in both world wars. During the Second World War he commanded the Second Army in north west Europe. A highly professional an ...

and the 15th Brigade under Brigadier Horatio Berney-Ficklin

Major General Horatio Pettus Mackintosh Berney-Ficklin, (13 June 1892 – 17 February 1961) was a British Army officer who served in both the First and Second World Wars. During the latter, he commanded for just over three years – from July 1 ...

, and supporting divisional troops.

The next few months were spent in relative quiet, the brigade either training or helping in the construction of defensive positions in expectation of a repeat of the trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising military trenches, in which troops are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery. Trench warfare became ar ...

that had characterised so much of World War I. By 9 May 1940, the day before the German Army attacked in the West, Stopford's brigade, along with the rest of the 5th Division, was held in GHQ Reserve, the War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

's view being that it should return to the United Kingdom as a reserve. However, by 16 May the division (excluding the 15th Brigade, which had been removed for participation in operations in Norway) was on the River Senne

The Senne () or Zenne () is a small river that flows through Brussels, left tributary of the Dijle/Dyle.

Its source is in the village of Naast (Soignies), Naast near the municipality of Soignies. It is an indirect tributary of the Scheldt, ...

, where it first encountered the Germans, but was soon ordered to disengage and withdraw to the River Escaut

The Scheldt (french: Escaut ; nl, Schelde ) is a river that flows through northern France, western Belgium, and the southwestern part of the Netherlands, with its mouth at the North Sea. Its name is derived from an adjective corresponding to ...

. On 19 May the division was ordered to Arras, where a gap was emerging. Major General Franklyn, GOC of the 5th Division, was ordered to take command of Major General Giffard Martel's 50th Division 50th Division or 50th Infantry Division may refer to:

Infantry divisions:

* 50th Division (1st Formation)(People's Republic of China)

* 50th Infantry Division (German Empire)

* 50th Reserve Division (German Empire)

* 50th Infantry Division Regina, ...

and the 1st Army Tank Brigade, in addition to his own division, which was to be known as "Frankforce". On 21 May "Frankforce" was ordered by General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Lord Gort, Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the BEF, to attack across the Gernan line of advance. Stopford's 17th Brigade was held in reserve on Vimy Ridge

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was part of the Battle of Arras, in the Pas-de-Calais department of France, during the First World War. The main combatants were the four divisions of the Canadian Corps in the First Army, against three divisions of ...

for the operation, and, on 23 May, after Stopford himself noticed German infantry and tanks advancing on 17th Brigades' position. Although French support was promised it never materialised and the brigade, after heavy fighting, was ordered to retreat, withdrawing from their positions on the night of 23 May and the early hours of 24 May.

The 5th Division was then moved to the Ypres−Comines Canal, where another gap had been created on the BEF's left flank, due to the wholesale surrender of the Belgian Army

The Land Component ( nl, Landcomponent, french: Composante terre) is the land branch of the Belgian Armed Forces. The King of the Belgians is the commander in chief. The current chief of staff of the Land Component is Major-General Pierre Gérard. ...

.Mead, p. 442 Stopford's brigade came under a succession of very heavy attacks from 26 to 28 May, suffering very heavy losses as a result, but managing to retain its position. By the time the 17th Brigade fell back towards Dunkirk, from where it was evacuated to England on the night of 31 May/1 June, the brigade was reduced from a strength of over 2,500 officers and men, at the beginning of the campaign, to less than that of a single battalion, and Brigadier Dempsey's 13th Brigade was in a similarly depleted state.

Britain

A few weeks later Stopford, along with Dempsey, was awarded theDistinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, ty ...

(DSO) for his services in France and Belgium. Stopford remained with his brigade for the next seven months, in June moving to Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

with the rest of the division, now reunited with all three brigades and commanded from mid-July by Major General Horatio Berney-Ficklin, formerly the 15th Brigade commander, after Major General Franklyn was promoted to command VIII Corps 8th Corps, Eighth Corps, or VIII Corps may refer to:

* VIII Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VIII Army Corps (German Confederation)

* VIII Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Ar ...

, to reform after its severe casualties. Most of the rest of 1940 was spent in Scottish Command

Scottish Command or Army Headquarters Scotland (from 1972) is a command of the British Army.

History Early history

Great Britain was divided into military districts on the outbreak of war with France in 1793. The Scottish District was comman ...

and was devoted to training to repel a German invasion of Britain

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (german: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Battle o ...

, then, in the aftermath of Dunkirk, thought to be imminent, although in Scotland it was considered less likely, yet still a distinct possibility. By late October, with the threat of invasion now much receded, the division moved to North West England.

By now recognised as a potential senior commander, and in common with a number of other relatively junior officers who had fought in France, in late January 1941 he handed over command of the 17th Brigade, which he had now commanded for almost sixteen months, to Brigadier G. W. B. Tarleton and was made GOC of the 56th (London) Infantry Division

The 56th (London) Infantry Division was a Territorial Army infantry division of the British Army, which served under several different titles and designations. The division served in the trenches of the Western Front during the First World Wa ...

, in succession to Major General Claude Liardet

Major General Sir Claude Francis Liardet, (26 September 1881 – 5 March 1966) was an insurance broker, businessman and a long-serving artillery officer in Britain's part-time Territorial Army before becoming the first Commandant General of the ...

, soon receiving a promotion to the acting major general. A first line Territorial Army (TA) formation, formerly the 1st London Division, the 56th Division − comprising the 167th, 168th and 169th Infantry Brigades and supporting divisional troops − was serving in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, the most vulnerable part of the country to invasion, as one of three divisions in XII Corps 12th Corps, Twelfth Corps, or XII Corps may refer to:

* 12th Army Corps (France)

* XII Corps (Grande Armée), a corps of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* XII (1st Royal Saxon) Corps, a unit of the Imperial German Army

* XII ...

, then commanded by Lieutenant General Andrew Thorne until April when he was replaced by Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery. The two other divisions in XII Corps were the 43rd (Wessex) and 44th (Home Counties) Divisions, commanded respectively by Major Generals Charles Allfrey (from late February) and Brian Horrocks (from late June), both of whom were known to Stopford, having been fellow instructors at the Staff College, Camberley before the war. Thanks to his predecessor, Major General Liardet, a TA officer who had been GOC for well over three years, the division, which had not seen action in France, was relatively well trained and reasonably well-equipped and, with the arrival of Montgomery as the new corps commander, large-scale exercises

Exercise is a body activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness.

It is performed for various reasons, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardiovascular system, hone athletic s ...

became common, getting progressively more difficult each week. Montgomery, already well known for his tendency to dismiss senior officers who failed to live up to his standards, appears to have formed a high opinion of Stopford, as the latter was not sacked, and may well have secured for him his next appointment, as Commandant

Commandant ( or ) is a title often given to the officer in charge of a military (or other uniformed service) training establishment or academy. This usage is common in English-speaking nations. In some countries it may be a military or police ran ...

of the Staff College, Camberley, handing over command of the 56th Division to Major General Eric Miles

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major-General Eric Grant Miles Order of the Bath, CB Distinguished Service Order, DSO Military Cross, MC (11 August 1891 – 3 November 1977) was a senior British Army Officer (armed forces), officer who saw activ ...

in early October.

Stopford took over as Commandant from Major General Robert Collins, who ironically had been one of his instructors there when he was attending as a student in the 1920s. The course at the Staff College, Camberley (and also the Staff College, Quetta

( ''romanized'': Pir Sho Biyamooz Saadi)English: Grow old, learning Saadi

ur, سیکھتے ہوئے عمر رسیدہ ہو جاؤ، سعدی

, established = (as the ''Army Staff College'' in Deolali, British India)

, closed ...

in India for Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

officers) had, before the war, lasted almost two years and the intention was to teach the students to not only be excellent staff officers but, essentially, to prepare them to be the generals of the future. The outbreak of war, and the necessity to provide large numbers of competent and qualified staff officers in the quickest time possible, had resulted in the course being considerably reduced from nearly two years to five months, and the pre-war competitive entrance exam was abolished. Stopford, promoted to temporary major general in January 1942, was there for just over a year, where many important lessons were learnt from the fighting in North Africa, until, in November 1942 Stopford handed over to Major General Sir Alan Cunningham.

Stopford's next posting was to XII Corps, this time as its GOC, with a promotion to the acting rank of lieutenant general. Taking over from Lieutenant General James Gammell, who had briefly been a fellow brigade commander in the 5th Division shortly after Dunkirk, XII Corps was still serving in Kent, although the emphasis was now slowly changing from being on the defensive to taking the offensive. The corps, then comprising Major General William Ramsden's 3rd (replaced by Major General William Bradshaw's 59th Division in late March), Major General Ivor Thomas's 43rd (Wessex) and Major General Robert Ross's 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division

The 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division was an infantry division of the British Army that fought in both the First and Second World Wars. Originally raised in 1908 as the Welsh Division, part of the Territorial Force (TF), the division saw service in ...

s, along with several independent brigades, had been selected for participation in Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy. Throughout 1943 the corps, aided by its Brigadier General Staff (BGS), Dudley Ward, participated in several large-scale exercises, most notably in Exercise SPARTAN in March. Made a temporary lieutenant general in early November, Stopford handed over XII Corps to Lieutenant General Neil Ritchie

General Sir Neil Methuen Ritchie, (29 July 1897 – 11 December 1983) was a British Army officer who saw service during both the world wars. He is most notable during the Second World War for commanding the British Eighth Army in the North Af ...

later in the month.

Burma and India

Stopford was sent toIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

to become GOC of XXXIII Indian Corps, in succession to Lieutenant General Philip Christison

General Sir Alexander Frank Philip Christison, 4th Baronet, (17 November 1893 – 21 December 1993) was a British Army officer who served with distinction during the world wars. After service as a junior officer on the Western Front in the Fir ...

, who was posted to XV Corps 15th Corps, Fifteenth Corps, or XV Corps may refer to:

*XV Corps (British India)

* XV Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army prior to and during World War I

* 15th Army Corps (Russian Empire), a unit in World War I

*XV Royal Bav ...

as its GOC. Formed the previous year, the corps had so far not seen action against the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

, being initially held in reserve. Stopford's arrival, however, coincided with a new role conceived for his corps, which then consisted of only Major General John Grover's British 2nd Infantry Division. At the Cairo Conference

The Cairo Conference (codenamed Sextant) also known as the First Cairo Conference, was one of the 14 summit meetings during World War II that occurred on November 22–26, 1943. The Conference was held in Cairo, Egypt, between the United Kingdo ...

, which was held shortly after Stopford's arrival in India, U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

promised Generalissimo

''Generalissimo'' ( ) is a military rank of the highest degree, superior to field marshal and other five-star ranks in the states where they are used.

Usage

The word (), an Italian term, is the absolute superlative of ('general') thus me ...

Chiang Kai-shek of the Republic of China that the Allies would launch an amphibious operation

Amphibious warfare is a type of Offensive (military), offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the opera ...

across the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line betwee ...

. Roosevelt's intention was to convince the Chinese to keep as many of their forces in northern Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

as possible. British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

preferred an amphibious assault on Sumatra (codenamed Operation Culverin), at the northern tip of the island, but there were too few resources available for such an operation. As a result, Churchill considered Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the newly appointed Supreme Allied Commander of South East Asia Command

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allied operations in the South-East Asian Theatre during the Second World War.

History Organisation

The initial supreme commander of the theatre was General Sir A ...

(SEAC), could instead plan to capture the Andaman Islands (codenamed Operation Buccaneer

Operation Buccaneer is an "ongoing international copyright piracy investigation and prosecution" undertaken by the United States federal government. It was part of a crackdown divided into three parts: Operation Bandwidth, Operation Buccaneer and ...

). In December the Allied leaders returned to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the Capital city, capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, List of ...

, both Mountbatten and Stopford meeting them there, the former presenting his views personally to both Roosevelt and Churchill. Despite his best efforts it was decided to cancel the latter operation, due to a lack of resources, both in manpower and landing craft.

Mountbatten was not beaten and, upon returning to India, ordered Stopford to continue to train XXXIII Corps in amphibious operations, which it did so for the next months. In March 1944, however, the Japanese 15th Army, under

Mountbatten was not beaten and, upon returning to India, ordered Stopford to continue to train XXXIII Corps in amphibious operations, which it did so for the next months. In March 1944, however, the Japanese 15th Army, under Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Renya Mutaguchi

was a Japanese military officer, lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II and field commander of the IJA forces during the Battle of Imphal.

Biography

Mutaguchi was a native of Saga Prefecture. He graduated from the ...

, launched an offensive at the centre of the Allied front at Imphal

Imphal ( Meitei pronunciation: /im.pʰal/; English pronunciation: ) is the capital city of the Indian state of Manipur. The metropolitan centre of the city contains the ruins of Kangla Palace (also known as Kangla Fort), the royal seat of the f ...

. Lieutenant General William Slim

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, GOC of the Fourteenth Army (which Stopford's XXXIII Corps was serving under), and Lieutenant General Geoffry Scoones

General Sir Geoffry Allen Percival Scoones, (also spelt Geoffrey; 25 January 1893 – 19 September 1975) was a senior officer in the Indian Army during the Second World War.

Early life and education

Scoones was born in Karachi, British India, ...

, GOC British IV Corps, had both predicted a move like this by the Japanese, and Scoones, whose IV Corps was holding the sector, withdrew his corps into a more defensible sector.Mead, p. 443 The Fourteenth Army's GOC had failed to estimate the arrival of the Japanese 31st Division

The was an infantry division of the Imperial Japanese Army. Its call sign was the . The 31st Division was raised during World War II in Bangkok, Thailand, on March 22, 1943, out of Kawaguchi Detachment and parts of the 13th, 40th and 116th di ...

under Lieutenant General Kōtoku Satō

was a lieutenant general in the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II.

Biography Early career

Satō was born in Yamagata prefecture and attended military preparatory school in Sendai. He graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1913 ...

, which headed for Kohima

Kohima (; Angami Naga: ''Kewhira'' ()), is the capital of the Northeastern Indian state of Nagaland. With a resident population of almost 100,000, it is the second largest city in the state. Originally known as ''Kewhira'', Kohima was founded ...

, 80 miles north of Imphal. If Satõ's 31st Division were able to take the small town of Kohima, they would be almost unopposed and be able to march into Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

, thereby cutting land communications to Ledo, at the Indian end of the Ledo Road

The Ledo Road (from Ledo, Assam, India to Kunming, Yunnan, China) was an overland connection between India and China, built during World War II to enable the Western Allies to deliver supplies to China and aid the war effort against Japan ...

, then in the process of being built to China.

The British first received reports that the Japanese were aiming for Kohima from the local Naga people

Nagas are various ethnic groups native to northeastern India and northwestern Myanmar. The groups have similar cultures and traditions, and form the majority of population in the Indian states of Nagaland and Manipur and Naga Self-Administere ...

, and from V Force

V Force was a reconnaissance, intelligence-gathering and guerrilla organisation established by the British against Japanese forces during the Burma Campaign in World War II.

Establishment and organisation

In April 1942, when the Japanese drove t ...

patrols, in the third week of March. The 1st Battalion, Assam Regiment

The Assam Regiment is an infantry regiment of the Indian Army. The regiment consists of 25 battalions: 15 regular battalions, 3 Rashtriya Rifles battalions, 5 Territorial Army battalions (including 2 ecological battalions). It recruits exclusiv ...

moved west to Jessami

Jessami is a village in Ukhrul district, Manipur, India. Jessami is a border village in the extreme north of Manipur State and borders with Meluri, a border village of Nagaland State. Being nearer to Nagaland, the town used to get electricity fr ...

to intercept them. On 28 March fighting began and continued for another two days, gaining valuable time. The battalion, only very recently raised, fighting against a numerically superior force, was forced to withdraw to Kohima. At the same time Colonel Hugh Richards had arrived to take command of the garrison at Kohima, which was severely outnumbered. Lieutenant General Slim, GOC Fourteenth Army, made a decision for the 161st Indian Brigade, detached from Major General Harold Briggs's 5th Indian Division, to be flown into Dimapur

Dimapur () is the largest city in the Indian state of Nagaland. As of 2011, the municipality had a population of 122,834. The city is the main gateway and commercial centre of Nagaland. Located near the border with Assam along the banks of the ...

, and to move into Kohima, arriving there on 29 March, after receiving reports on the Japanese strength. Slim also placed Major General R. P. L. Ranking, GOC 202nd Lines of Communication Area (202 LoC), in temporary command of the area.

Realising that Lieutenant General Scoones, GOC British IV Corps, would be unable to control the Kohima battle, Slim asked his superior, General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Sir George Giffard, commanding the 11th Army Group

The 11th Army Group was the main British Army force in Southeast Asia during the Second World War. Although a nominally British formation, it also included large numbers of troops and formations from the British Indian Army and from British Africa ...

, for Stopford and his HQ XXXIII Corps to be flown out from India. Stopford, establishing his HQ on 3 April at Jorhat

Jorhat ( ) is one of the important cities and a growing urban centre in the state of Assam in India.

Etymology

Jorhat ("jor" means twin and "hat" means market) means two hats or mandis - "Masorhaat" and "Sowkihat" which existed on the opposite ...

, took over from Major General Ranking, and began to assess the situation. He outlined the priorities as being, in the following order, Dimapur, the Ledo Road and Kohima, and ordered the 161st Indian Brigade to defend the Nichugard Pass, thereby safeguarding Dimapur but leaving Kohima uncovered. However, the priorities were changed, following a consultation with the Fourteenth Army GOC, and Kohima was now made the first priority, and the 161st Indian Brigade was ordered to return. Only a battalion, the 4th Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment

The Queen's Own Royal West Kent Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army based in the county of Kent in existence from 1881 to 1961. The regiment was created on 1 July 1881 as part of the Childers Reforms, originally as the Queen' ...

(4th Royal West Kents), and a single company of the 4th Battalion, 7th Rajput Regiment

7 (seven) is the natural number following 6 and preceding 8. It is the only prime number preceding a cube.

As an early prime number in the series of positive integers, the number seven has greatly symbolic associations in religion, mythology, s ...

managed to reinforce the Kohima garrison, which consisted of a significant number of non-combat troops, before the town was surrounded. The remainder of the 161st Indian Brigade was cut off at Jotsoma, a few miles back from the road to Dimapur.

The initial defence of Kohima, therefore, was conducted by a far smaller force than was necessary. However, fighting in very grim conditions reminiscent of World War I, the force managed to hold on during a siege that lasted over two weeks, the British and Indian troops being boxed in on Garrison Hill. The distance between them and the Japanese was the length of the local District Commissioner's

The initial defence of Kohima, therefore, was conducted by a far smaller force than was necessary. However, fighting in very grim conditions reminiscent of World War I, the force managed to hold on during a siege that lasted over two weeks, the British and Indian troops being boxed in on Garrison Hill. The distance between them and the Japanese was the length of the local District Commissioner's tennis court

A tennis court is the venue where the sport of tennis is played. It is a firm rectangular surface with a low net stretched across the centre. The same surface can be used to play both Types of tennis match, doubles and singles matches. A variet ...

. Three Indian mountain batteries at Jotsoma were initially the only outside support. However, Major General Grover's British 2nd Division broke the road block between Jotsoma and Dimapur, thus enabling the 161st Indian Brigade to relieve the defenders of Kohima on 18 April.

Stopford's objective was now to drive the Japanese away from Kohima, the British 2nd Division being the main initial tool for the job, although significant reinforcements were on the way. These consisted of the 23rd Brigade, which had been intended to join the Chindits

The Chindits, officially as Long Range Penetration Groups, were special operations units of the British and Indian armies which saw action in 1943–1944 during the Burma Campaign of World War II.

The British Army Brigadier Orde Wingate form ...

, and the 21st Indian Division, temporarily created under the command of Major General Cameron Nicholson

General Sir Cameron Gordon Graham Nicholson, (30 June 1898 – 7 July 1979) was a British Army officer who served as Adjutant-General to the Forces. He later served as Governor of the Royal Hospital Chelsea.

Military career

After being educated ...

, who Stopford knew as a fellow instructor at the Staff College before the war, to take command of other units who had been brought up from India. The 6th Brigade of the British 2nd Division relieved the 161st Indian Brigade and continued to hold Garrison Hill against a succession of Japanese assaults. The division's 4th Brigade undertook a right hook flanking movement to come in from the south, against the Aradura Spur, while the 5th Brigade began a left hook from the north. Both brigade assaults did not meet with the expected success. The 33rd Indian Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Frederick Loftus-Tottenham, part of Major General Frank Messervy's 7th Indian Division, arrived from the Arakan and, assisted by the 6th Brigade, cleared the enemy from Kohima Ridge.Mead, p. 444 However, the fighting was relentless as the Japanese remained in two strong defensive preparations, on the Aradura Ridge and around Naga Village. The British 2nd Division, which by now had suffered very heavy casualties, pushed them off Aradura Ridge in early June, the 7th Indian Division pushing them out of Naga Village around the same time. The Japanese retreated to the Chindwin River and, on 22 June, Stopford's XXXIII Corps finally made contact with Lieutenant General Scoones's British IV Corps.

The battle over, Stopford made the decision to sack Major General Grover, GOC of the British 2nd Division, and to replace him with Major General Cameron Nicholson. During the Kohima fighting Stopford had begun to lose confidence in Grover, believing him to be too slow and cautious, as well as apparently having handled Indian units under his command rather unsatisfactorily, and, after consulting with Lieutenant General Slim, had him sacked, which did not initially go down well with the division which, after its heavy losses, spent the next few months recuperating. Stopford's XXXIII Corps continued to clear the Japanese from the country to the west of the Chindwin River and north of Ukhrul, on 31 July taking over from the IV Corps which returned to India to rest. During the end of the summer and in the early stages of autumn the pursuit of the retreating Japanese continued and the 5th Indian Division, now commanded by Major General Geoffrey Evans, along with the Lushai Brigade (both of which now formed part of Stopford's XXXIII Corps), pursued the Japanese towards Tiddim

Tedim (, , ( Zo: ''Tedim Khawpi'', pronounced ; is a town in and the administrative seat of Tedim Township, Chin State, in the north-western part of Burma. It is the second largest town in Chin State. The town's four major boroughs (''vengte'') ...

and into the Chin Hills

The Chin Hills are a range of mountains in Chin State, northwestern Burma (Myanmar), that extends northward into India's Manipur state.

Geography

The highest peak in the Chin Hills is Khonu Msung, or Mount Victoria, in southern Chin State, whic ...

. At the same time the 11th (East Africa) Division

The 11th (East Africa) Infantry Division was a British Empire colonial unit formed in February 1943 during the Second World War.

Formation

In 1943, the 11th (East Africa) Division was formed primarily of troops from British East Africa. The divi ...

under Major General Charles Fowkes (also under XXXIII Corps) cleared the Kabaw Valley

The Kabaw Valley also known as Kubo valley is a highland valley in Myanmar's western Sagaing division, close to the border with India's Manipur. The valley is located between Heerok or Yoma ranges of mountains, which constitute the present day bo ...

, later establishing a bridgehead

In military strategy, a bridgehead (or bridge-head) is the strategically important area of ground around the end of a bridge or other place of possible crossing over a body of water which at time of conflict is sought to be defended or taken over ...

across the Chindwin River.

On 3 December the 80th Indian Infantry Brigade, part of Major General Douglas Gracey

General Sir Douglas David Gracey & Bar (3 September 1894 – 5 June 1964) was a British Indian Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars. He also fought in French Indochina and was the second Commander-in-Chief of the P ...

's 20th Indian Division (which joined XXXIII Corps in July), crossed the Chindwin River at Mawlaik

Mawlaik ( my, မော်လိုက် ; shn, မေႃႇလဵၵ်) is a town in Mawlaik District, Sagaing Region in north-west Myanmar, along the Chindwin River.

Etymology

" Mawlaik" derives from the Shan language

The Shan language ...

, and turned south. The day afterwards the 19th Indian Division under Major General Thomas Rees crossed the river further north at Sittaung, heading eastwards. The corps, spearheaded by Major General Gracey's 20th Indian Division, with the British 2nd Division following up behind, crossed, on 18 December, the longest Bailey bridge

A Bailey bridge is a type of portable, pre-fabricated, truss bridge. It was developed in 1940–1941 by the British for military use during the Second World War and saw extensive use by British, Canadian and American military engineering units. ...

in the world near Kalewa

Kalewa is a town at the confluence of the Chindwin River and the Myittha River in Kale District, Sagaing Region of north-western Myanmar. It is the administrative seat of Kalewa Township.

Climate

Kalewa has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen ...

. The Fourteenth Army commander's intention was to deceive the Japanese into believing that Stopford's XXXIII Indian Corps was their main threat. Slim, knowing that the Japanese were planning to withdraw behind the Irrawaddy River, wished to surprise them, with XXXIII Corps being seen as the main threat, while British IV Corps, now commanded by Lieutenant General Frank Messervy in place of Scoones, approached stealthily through the Chin Hills with the intention of crossing the Irrawaddy in the south and west.

On 15 December 1944 he and his fellow corps commanders, Christison and Scoones, were knighted and invested as Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Lord Wavell, the Viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, at a ceremony at Imphal in front of Scottish, Gurkha and Punjab regiments. Lieutenant General Slim, GOC of the Fourteenth Army, was knighted and invested as a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as o ...

at the same occasion.Smart, p. 299

Stopford executed his superiors' order to the letter as, in mid-January 1945, Major General Rees's 19th Indian Division established two bridgeheads across the river, north of the city of Mandalay, and in late February the division moved towards the city. Major General Gracey's 20th Indian Division reached the river in late January, crossing in mid-February, while Major General Nicholson's British 2nd Division formed a bridgehead on 25 February. The two divisions began to expand their bridgeheads but the 19th Indian Division won the race to capture Mandalay, which fell on 20 March.

IV Corps had, at the same time, taken

IV Corps had, at the same time, taken Meiktila

Meiktila (; ) is a city in central Burma on the banks of Meiktila Lake in the Mandalay Region at the junctions of the Bagan-Taunggyi, Yangon-Mandalay and Meiktila-Myingyan highways. Because of its strategic position, Meiktila is home to Myanmar Ai ...

, holding it off against several determined Japanese counterattacks. This meant the end for any hopes the Japanese may still have had about retaining hold of Burma. In early May Lieutenant General Slim declared his intention of capturing Rangoon before the arrival of the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal osci ...

. Lieutenant General Messervy's IV Corps took the Railway Valley towards Toungoo

Taungoo (, ''Tauñngu myoú''; ; also spelled Toungoo) is a district-level city in the Bago Region of Myanmar, 220 km from Yangon, towards the north-eastern end of the division, with mountain ranges to the east and west. The main industry ...

, and Stopford's XXXIII Indian Corps, with the 7th and 20th Indian Divisions now under command, advanced on both sides of the Irrawaddy. Rangoon fell in early May, by which time XXXIII Corps had cleared the river south of Prome.

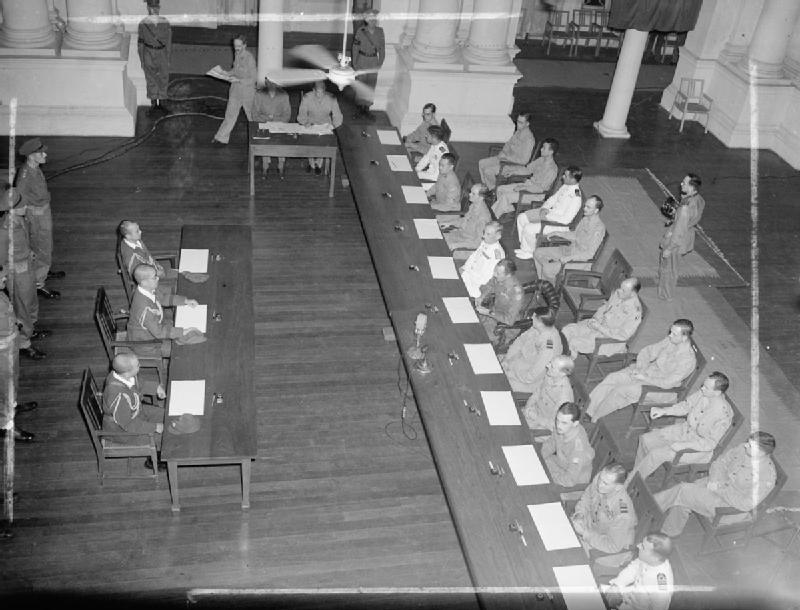

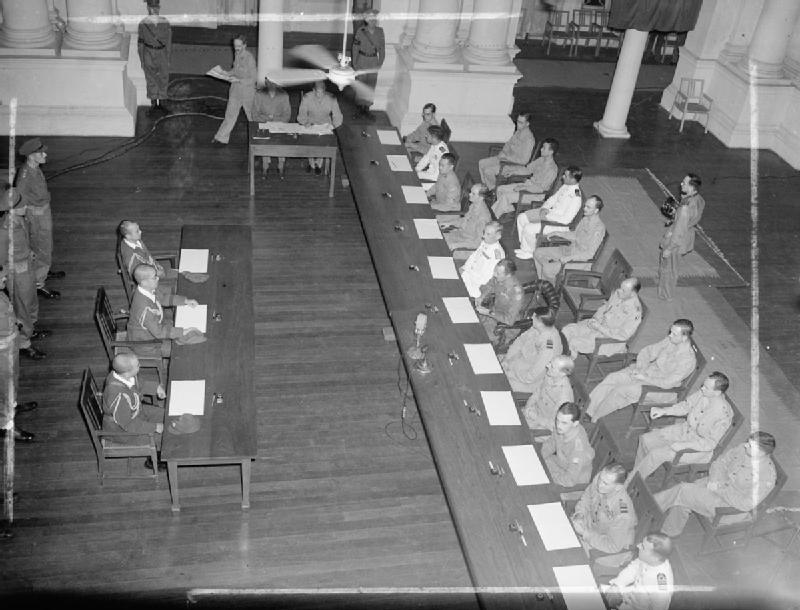

Confirmed in his rank of lieutenant general in April 1945, in late May Stopford's XXXIII Indian Corps HQ was redesignated as the new HQ British Twelfth Army. The Twelfth Army now took responsibility for finishing the final stages of the campaign in Burma, allowing the HQ Fourteenth Army to return to India, to plan for future operations, specifically the recapture of Malaya. The battle under Stopford's command would become known as the

Confirmed in his rank of lieutenant general in April 1945, in late May Stopford's XXXIII Indian Corps HQ was redesignated as the new HQ British Twelfth Army. The Twelfth Army now took responsibility for finishing the final stages of the campaign in Burma, allowing the HQ Fourteenth Army to return to India, to plan for future operations, specifically the recapture of Malaya. The battle under Stopford's command would become known as the Battle of the Sittang Bend

The Battle of the Sittang Bend and the Japanese Breakout across Pegu Yomas were linked Japanese military operations during the Burma Campaign, which took place nearly at the end of World War II. Surviving elements of the Imperial Japanese Army ...

. The remaining Japanese in the Irrawaddy Valley, numbering roughly 30,000 troops, attempted to cross the Pegu Yoma Hills and the Sittang River

The Sittaung River ( my, စစ်တောင်းမြစ် ; formerly, the Sittang or Sittounghttps://unstats.un.org/unsd/geoinfo/UNGEGN/docs/8th-uncsgn-docs/inf/8th_UNCSGN_econf.94_INF.75.pdf ) is a river in south central Myanmar in Bago ...

, into the supposed safety of the Karen Hills

The Karen Hills, () also known as Kayah-Karen Mountains, are one of the main hill ranges in eastern Burma. They are located at the SW corner of Shan State and in Kayah State, a mountainous region where the only relatively flat area is Loikaw, t ...

, bordering Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

.Mead, p. 445 Given Lieutenant General Messervy's IV Corps, with three divisions under command, the Twelfth Army inflicted severe losses upon the Japanese troops, a significant number of whom were suffering from starvation or otherwise ill. As it turned out, this was to be the last major land action fought by the Western Allies during World War II as, in mid-August, the Japanese surrendered in Tokyo. Stopford gave orders for all offensive operations to cease, and soon began negotiations with the Japanese, which culminated in their surrender at Rangoon in mid-September. The following month, at another ceremony, General Heitarō Kimura

was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army. He was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to death by hanging.

Biography

Kimura was born in Saitama prefecture, north of Tokyo, but was raised in Hiroshima prefecture, which he considered to be h ...

, commander of the Japanese Burma Area Army, handed over to Stopford his sword.

Postwar

After the war Stopford served as commander of Burma Command (renamed from Twelfth Army) from 1945 to 1946, as C-in-C Allied Land Forces in the Dutch East Indies in 1946 and as C-in-C SEAC from 1946 to 1947 before becoming General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) of Northern Command in England from 1947 to 1949. He retired from the British Army in 1949, with the rank of full general, having been promoted to that rank in October 1946. He was also appointed Colonel-in-Chief of the Rifle Brigade. After the war Stopford was further made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in 1947 and a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1948. He was Colonel Commandant of the Rifle Brigade from 1951 to 1958, and Chairman of the Army Cadet Force Association from 1951 to 1961, later becoming vice president from 1961. In 1962 he held the honorary post of Deputy Lieutenant of Oxfordshire and lived at Rock Hill House inChipping Norton

Chipping Norton is a market town and civil parish in the Cotswold Hills in the West Oxfordshire district of Oxfordshire, England, about south-west of Banbury and north-west of Oxford. The 2011 Census recorded the civil parish population as ...

. He married Dorothy Deare, daughter of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Foulkes Deare, on 12 April 1921./ref> They had no children. His wife died on 4 October 1982.

References

Bibliography

* * * Williams, David. ''The Black Cats at War: The Story of the 56th (London) Division T.A., 1939–1945'' .External links

, - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Stopford, Montagu 1892 births 1971 deaths Academics of the Staff College, Camberley British Army generals of World War II British Army personnel of World War I Commandants of the Staff College, Camberley Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Deputy Lieutenants of Oxfordshire Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Knights Commander of the Order of the British Empire Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Military personnel from London People educated at Wellington College, Berkshire People from Mayfair Recipients of the Military Cross Rifle Brigade officers British Army generals Montagu Burials in Oxfordshire