Marchioness disaster on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

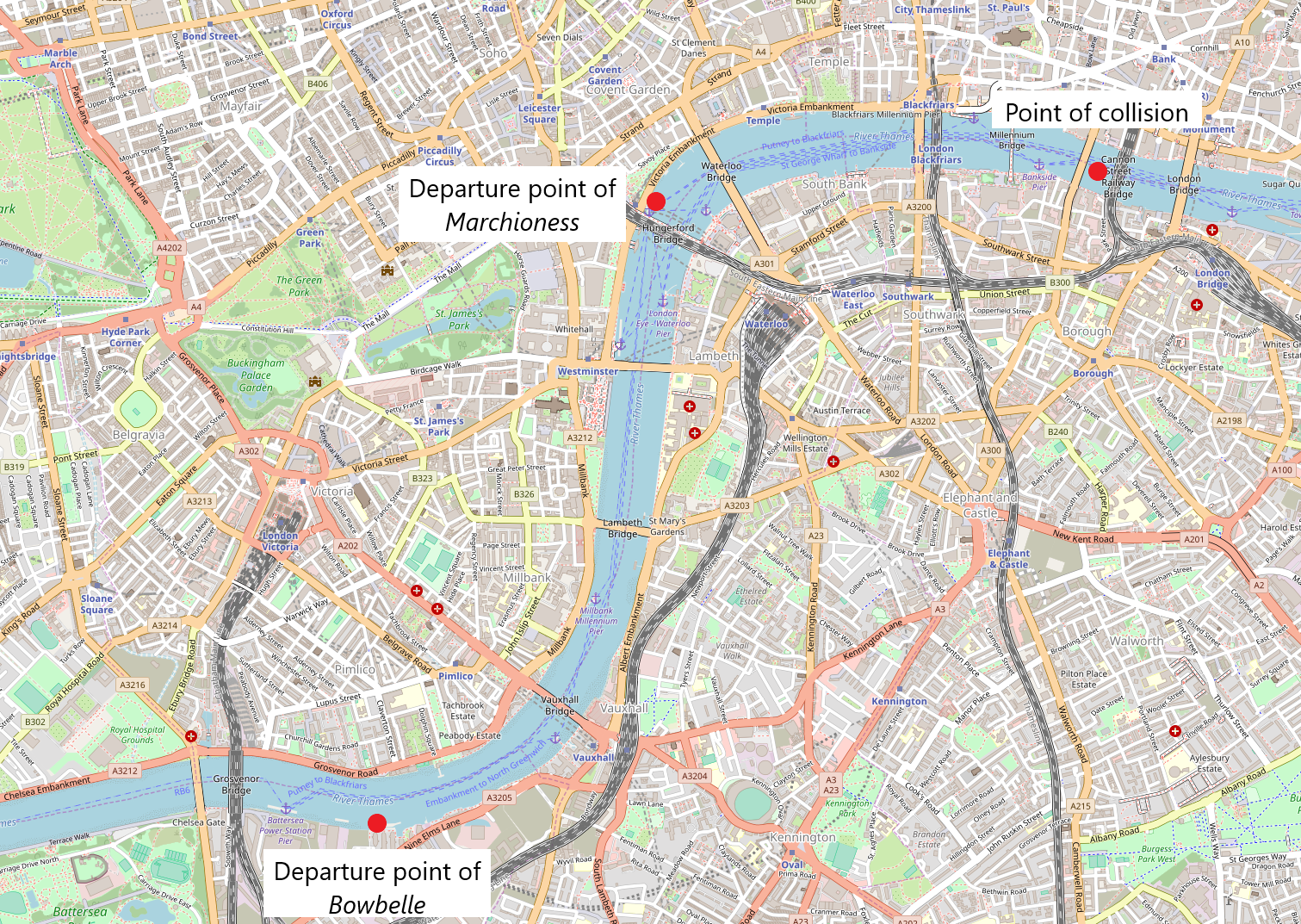

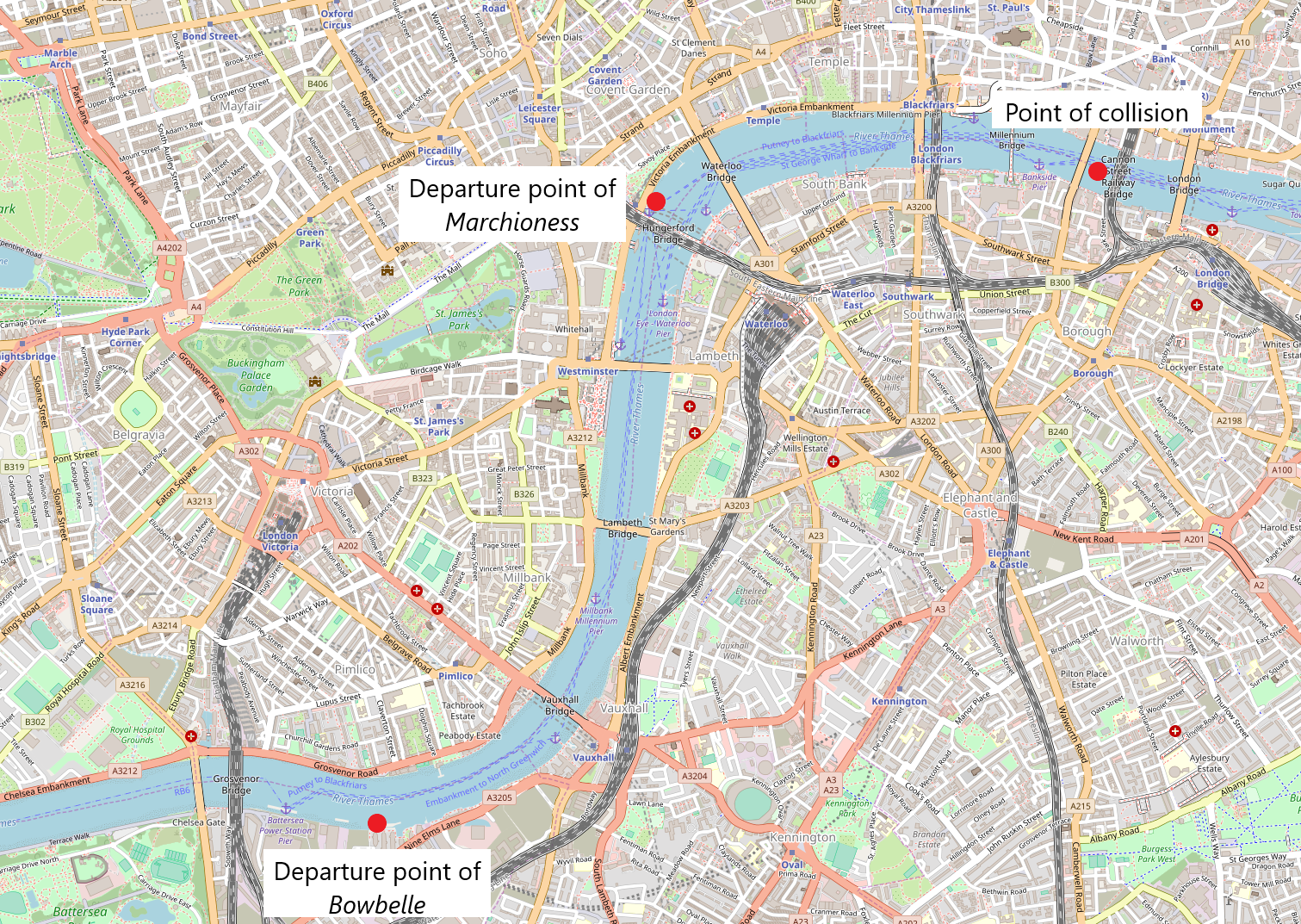

The ''Marchioness'' disaster was a collision between two vessels on the

The night of 19–20 August 1989 was a clear one; it was three days after the full moon and there was good visibility. There was a negligible wind. It was a

The night of 19–20 August 1989 was a clear one; it was three days after the full moon and there was good visibility. There was a negligible wind. It was a  After colliding with ''Marchioness'', ''Bowbelle'' hit one of the piers of Cannon Street Bridge, and radioed TNS at 1:48 am to correct the inaccurate reference to Battersea Bridge; at 1:49 am Henderson reported to TNS:

After colliding with ''Marchioness'', ''Bowbelle'' hit one of the piers of Cannon Street Bridge, and radioed TNS at 1:48 am to correct the inaccurate reference to Battersea Bridge; at 1:49 am Henderson reported to TNS:

The MAIB report considered that ''Marchioness'' had altered her course to port, which put her in line with ''Bowbelle''s path. The report concluded that:

The MAIB report considered that ''Marchioness'' had altered her course to port, which put her in line with ''Bowbelle''s path. The report concluded that:

Prescott accepted the recommendation and the public inquest took place in October and November 2000, with Clarke chairing proceedings; the report was published in March 2001. Clarke concluded that "The basic cause of the collision is clear. It was poor lookout on both vessels. Neither vessel saw the other in time to take action to avoid the collision." The underlying causes on why neither vessel saw the other were that Henderson did not ensure a proper lookout on ''Bowbelle''; that Blayney the lookout was not equipped with suitable radio equipment to inform his captain; that Faldo had not set up a lookout system on ''Marchioness'', nor did he keep a lookout aft himself. Focusing on Henderson, Clarke wrote "We cannot stress too strongly how much we deprecate Captain Henderson's conduct in drinking so much alcohol before returning to his vessel as master"; Clarke added "but we do not think that it is shown on the balance of probabilities that Captain Henderson would have acted differently if he had not consumed the alcohol or had the amount of sleep which he had". The captain was also criticised for his actions after the collision, when he did not broadcast a

Prescott accepted the recommendation and the public inquest took place in October and November 2000, with Clarke chairing proceedings; the report was published in March 2001. Clarke concluded that "The basic cause of the collision is clear. It was poor lookout on both vessels. Neither vessel saw the other in time to take action to avoid the collision." The underlying causes on why neither vessel saw the other were that Henderson did not ensure a proper lookout on ''Bowbelle''; that Blayney the lookout was not equipped with suitable radio equipment to inform his captain; that Faldo had not set up a lookout system on ''Marchioness'', nor did he keep a lookout aft himself. Focusing on Henderson, Clarke wrote "We cannot stress too strongly how much we deprecate Captain Henderson's conduct in drinking so much alcohol before returning to his vessel as master"; Clarke added "but we do not think that it is shown on the balance of probabilities that Captain Henderson would have acted differently if he had not consumed the alcohol or had the amount of sleep which he had". The captain was also criticised for his actions after the collision, when he did not broadcast a

English law provides no compensation for fatal accidents, other than for funeral expenses, unless financial dependency at the time of death can be proved. In most cases, the families of the ''Marchioness'' victims received little more than the cost of the funeral.

English law provides no compensation for fatal accidents, other than for funeral expenses, unless financial dependency at the time of death can be proved. In most cases, the families of the ''Marchioness'' victims received little more than the cost of the funeral.

After recommendations made in the Clarke report relating to the improvement of river safety, the government asked the

After recommendations made in the Clarke report relating to the improvement of river safety, the government asked the  In 2001 the

In 2001 the

Marchioness-Bowbelle Formal Investigation Website

In the UK Government Web Archive *

Marchioness Action Group

{{authority control Maritime incidents in 1989 Maritime incidents in England Shipwrecks of the River Thames History of the River Thames History of the City of London Port of London 1989 disasters in the United Kingdom 20th century in the London Borough of Southwark Transport disasters in London 1989 in London August 1989 events in the United Kingdom Little Ships of Dunkirk

River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

in London in the early hours of 20 August 1989, which resulted in the deaths of 51 people. The pleasure steamer ''Marchioness'' sank after being hit twice by the dredger

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing da ...

''Bowbelle'' at about 1:46 am, between Cannon Street railway bridge

Cannon Street station, also known as London Cannon Street, is a central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in Travelcard zone 1 located on Cannon Street in the City of London and managed by Network Rail. It is o ...

and Southwark Bridge.

''Marchioness'' had been hired for the evening for a birthday party and had about 130 people on board, four of whom were crew and bar staff. Both vessels were heading downstream, against the tide, ''Bowbelle'' travelling faster than the smaller vessel. Although the exact paths taken by the ships, and the precise series of events and their locations, are unknown, the subsequent inquiry considered it likely that ''Bowbelle'' struck ''Marchioness'' from the rear, causing the latter to turn to port, where she was hit again, then pushed along, turning over and being pushed under ''Bowbelle''s bow. It took thirty seconds for ''Marchioness'' to sink; 24 bodies were found within the ship when it was raised.

An investigation by the Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) blamed a lack of lookouts, but their report was criticised by the families of the victims, as the MAIB had not interviewed anyone on ''Marchioness'' or ''Bowbelle'', but relied on police interviews. The government refused to hold an inquiry, despite pressure from the families. Douglas Henderson, the captain of ''Bowbelle'', was charged with failing to have an effective lookout on the vessel, but two cases against him ended with a hung jury

A hung jury, also called a deadlocked jury, is a judicial jury that cannot agree upon a verdict after extended deliberation and is unable to reach the required unanimity or supermajority. Hung jury usually results in the case being tried again.

T ...

. A private prosecution for manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

against four directors of South Coast Shipping Company, the owners of ''Bowbelle'', and corporate manslaughter against the company was dismissed because of lack of evidence.

A formal inquiry in 2000 concluded that "The basic cause of the collision is clear. It was poor lookout on both vessels. Neither vessel saw the other in time to take action to avoid the collision." Criticism was also aimed at the owners of both ships, as well as the Department of Transport and the Port of London Authority

The Port of London Authority (PLA) is a self-funding public trust established on 31 March 1909 in accordance with the Port of London Act 1908 to govern the Port of London. Its responsibility extends over the Tideway of the River Thames and its ...

. The collision and the subsequent reports led to increased safety measures on the Thames, and four new lifeboat stations were installed on the river.

Background

''Marchioness''

The pleasure boat ''Marchioness'' was built in 1923 by the Salter Brothers of Oxford forJoseph Mears

Joseph Theophilus "JT" Mears (1871 – October 1935), was an English businessman, most notable for co-founding Chelsea Football Club.

He was born in 1871 in Hammersmith, London, the elder son of Joseph Mears, a builder.

In 1896, Mears and his br ...

, a businessman whose interests included running pleasure launches on the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

. She was long and at the beam, and measured 46.19 gross tons. She spent most of her life on the Thames, including when she was requisitioned during the Second World War by the Thames Hospital Emergency Service, when she was stationed in Dagenham

Dagenham () is a town in East London, England, within the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham. Dagenham is centred east of Charing Cross.

It was historically a rural parish in the Becontree Hundred of Essex, stretching from Hainault Fore ...

. Her service included being one of the little ships that aided in the 1940 Dunkirk evacuation

The Dunkirk evacuation, codenamed Operation Dynamo and also known as the Miracle of Dunkirk, or just Dunkirk, was the evacuation of more than 338,000 Allies of World War II, Allied soldiers during the World War II, Second World War from the bea ...

. ''Marchioness'' was sold to Thames Launches in 1945, when Mears's company was wound up. She was purchased by Tidal Cruises Ltd in 1978 and the upper works were rebuilt to form an upper and lower saloon. The new upper saloon obstructed the vision from the wheelhouse, and there was, the later inquiry established, a lack of easily accessible emergency exits, particularly from the lower decks. ''Marchioness'' had seven life rafts—each of which could support twenty people—and seven lifebuoys—each of which could support two people. Registered in London, she was licensed to carry 165 passengers. From the early 1970s there was an increase in the number of boats for evening or night-time parties and discos, and ''Marchioness'' was part of this market.

''Marchioness'' carried a crew of two: her captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

was Stephen Faldo; the mate was Andrew McGowan. On the night of her sinking, she also carried two members of bar staff. Faldo and McGowan had a business partnership, Top Bar Enterprises, which provided the bar staff and drink for the party. Faldo was 29 at the time of the sinking. He had begun working on the Thames at the age of 17 and had earned his full waterman's river licence in June 1984. He began work at Tidal Cruises in 1986 and became the permanent captain of ''Marchioness'' in 1987. He had forgotten to renew his riverman's licence in the run-up to the night of the collision, and was technically not entitled to skipper the vessel that night. A later inquiry considered the lack of licence was "a minor point because he was undoubtedly qualified to do so and could have renewed his licence by paying 50 pence". McGowan, age 21, became an apprentice to a waterman in June 1986. By February 1988 he had completed courses at the Port of London Authority

The Port of London Authority (PLA) is a self-funding public trust established on 31 March 1909 in accordance with the Port of London Act 1908 to govern the Port of London. Its responsibility extends over the Tideway of the River Thames and its ...

for chartwork and seamanship, and obtained his apprentice licence in May 1988; he joined ''Marchioness'' as a crew member around the same time.

''Bowbelle''

Theaggregate

Aggregate or aggregates may refer to:

Computing and mathematics

* collection of objects that are bound together by a root entity, otherwise known as an aggregate root. The aggregate root guarantees the consistency of changes being made within the ...

dredger

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing da ...

''Bowbelle'' was launched in 1964 by the Ailsa Shipbuilding Company of Troon

Troon is a town in South Ayrshire, situated on the west coast of Ayrshire in Scotland, about north of Ayr and northwest of Glasgow Prestwick Airport.

Troon has a port with freight services and a yacht marina. Up until January 2016, P&O ope ...

, Scotland. She was long and at the beam; her deadweight tonnage

Deadweight tonnage (also known as deadweight; abbreviated to DWT, D.W.T., d.w.t., or dwt) or tons deadweight (DWT) is a measure of how much weight a ship can carry. It is the sum of the weights of cargo, fuel, fresh water, ballast water, pro ...

was and she measured 1,474.72 gross tons. ''Bowbelle'' was one of six "Bow" ships owned by East Coast Aggregates Limited; they were managed by South Coast Shipping Company Limited. East Coast Aggregates Limited (ECA) was part of the larger RMC Group, a concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wid ...

products company. ''Bowbelle'' had a crew of nine: a master, two mates, three engineers, two able seamen

An able seaman (AB) is a seaman and member of the deck department of a merchant ship with more than two years' experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty". An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination ...

and a cook. The ship's captain, Douglas Henderson, aged 31, undertook a Deep Sea apprenticeship until 1978 and joined ECA in November 1987, when he became second mate on ''Bowsprite''. In May 1989 he became the master of ''Bowbelle''.

Vessels from ECA, including ''Bowbelle'', had previously been involved in accidents on the Thames. In July 1981 there was a collision between ''Bowtrader'' and the passenger launch ''Pride of Greenwich''; three months later ''Bowtrader'' was involved in a collision with ''Hurlingham'', another pleasure cruiser owned by Tidal Cruises. ''Bowbelle'' collided with Cannon Street railway bridge

Cannon Street station, also known as London Cannon Street, is a central London railway terminus and connected London Underground station in Travelcard zone 1 located on Cannon Street in the City of London and managed by Network Rail. It is o ...

in May 1982 and, the following month, was nearly in a collision with a passenger boat.

At the time of the collision with ''Marchioness'', ''Bowbelle'' was carrying aggregate and was trimmed down at the stern; this, along with the dredging equipment, limited the forward vision from the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually someth ...

. On 19 August 1989 Henderson visited several public houses over a period of three and a half hours and drank six pints (3.4 L; 120 imp fl oz) of lager. He returned to the ship at 6:00 pm for food and a short sleep; one of the ship's company, Terence Blayney, who acted as the forward lookout that night, was with Henderson, and drank seven pints over the same period.

Jonathan Phang and Antonio de Vasconcellos

''Marchioness'' was hired for a party for the night of 19–20 August 1989. It was organised byJonathan Phang

Jonathan Phang is a British food writer and chef, best known for his television appearances.

Early life

Phang was born in London. His father was from China and his mother from Guyana. He began his career as a fashion agent, working with mod ...

, a photographic agent, to celebrate the 26th birthday of Antonio de Vasconcellos, who worked in a merchant bank

A merchant bank is historically a bank dealing in commercial loans and investment. In modern British usage it is the same as an investment bank. Merchant banks were the first modern banks and evolved from medieval merchants who traded in commodi ...

. The pair were good friends and business partners in a photographic agency. Phang paid £695 to hire the boat from 1:00 am to 6:00 am, with extra for the hire of the disco, food and drinks. Many of those at the party were also in their twenties; some were former students and others worked in fashion, journalism, modelling and finance. The plan was for ''Marchioness'' to go downriver from the Embankment Pier near Charing Cross railway station

Charing Cross railway station (also known as London Charing Cross) is a central London railway terminus between the Strand and Hungerford Bridge in the City of Westminster. It is the terminus of the South Eastern Main Line to Dover via Ashfo ...

to Tower Bridge

Tower Bridge is a Grade I listed combined bascule and suspension bridge in London, built between 1886 and 1894, designed by Horace Jones and engineered by John Wolfe Barry with the help of Henry Marc Brunel. It crosses the River Thames clos ...

, then back to Charing Cross to land some of the passengers. ''Marchioness'' would then travel down to Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

before returning again to Charing Cross, arriving back at 5:45 am.

20 August 1989

0:00 am – 7:00 am

The night of 19–20 August 1989 was a clear one; it was three days after the full moon and there was good visibility. There was a negligible wind. It was a

The night of 19–20 August 1989 was a clear one; it was three days after the full moon and there was good visibility. There was a negligible wind. It was a spring tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tabl ...

, recorded as one of the highest of the year and the river was at half-tide at the time of the collision; it was running upriver at a rate of three knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot may also refer to:

Places

* Knot, Nancowry, a village in India

Archaeology

* Knot of Isis (tyet), symbol of welfare/life.

* Minoan snake goddess figurines#Sacral knot

Arts, entertainme ...

. There are several versions of the paths taken by the vessels in the approach to Southwark Bridge and beyond, and no agreement on the point when the two ships collided. Much of the evidence gathered in later investigations was inconsistent and any descriptions of the actions of the ships are based on average speeds and likely positions.

At 1:12 am ''Bowbelle'' left her berth at the Nine Elms

Nine Elms is an area of south-west London, England, within the London Borough of Wandsworth. It lies on the River Thames, with Battersea to the west, South Lambeth to the south and Vauxhall to the east.

The area was formerly mainly industrial ...

pier near Battersea Power Station

Battersea Power Station is a decommissioned Grade II* listed coal-fired power station, located on the south bank of the River Thames, in Nine Elms, Battersea, in the London Borough of Wandsworth. It was built by the London Power Company (LPC) ...

and radioed her move by VHF radio to Thames Navigation Service (TNS), based in Woolwich

Woolwich () is a district in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was maintained throu ...

. She reported passing Vauxhall Bridge

Vauxhall Bridge is a Grade II* listed steel and granite deck arch bridge in central London. It crosses the River Thames in a southeast–northwest direction between Vauxhall on the south bank and Pimlico on the north bank. Opened in 1906, it ...

at 1:20 am and Waterloo Bridge

Waterloo Bridge () is a road and foot traffic bridge crossing the River Thames in London, between Blackfriars Bridge and Hungerford Bridge and Golden Jubilee Bridges. Its name commemorates the victory of the British, Dutch and Prussians at the ...

at 1:35 am. In accordance with the usual procedure, TNS radioed all river traffic at 1:15 am and 1:45 am, advising them of ''Bowbelle''s downstream passage. ''Bowbelle''s average speed was about over the ground.

''Marchioness'' was supposed to leave Embankment Pier at 1:00 am, but was delayed until 1:25 am. No count was made of the number of passengers, but the accepted number on board is either 130 or 131. Faldo was in the wheelhouse, where he stayed until the collision. Heading downriver, just before Blackfriars Bridge

Blackfriars Bridge is a road and foot traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, between Waterloo Bridge and Blackfriars Railway Bridge, carrying the A201 road. The north end is in the City of London near the Inns of Court and Temple Chu ...

, ''Marchioness'' passed her sister pleasure cruiser ''Hurlingham''—which was also hosting a disco that night, and was also heading in the same direction. ''Marchioness''s average speed was about over the ground. She passed through the central arch of Blackfriars Bridge; at this point she was about in front of ''Bowbelle''. At some point after Blackfriars Bridge, ''Bowbelle'' overtook ''Hurlingham'' and steered for the central arch of Southwark Bridge. ''Marchioness'' also went through the central arch, but probably towards the southern side.

When ''Bowbelle'' was within of ''Marchioness'', the smaller vessel was affected by the forces of interaction—the water being pushed ahead of the large ship. At about 1:46 am, just after ''Marchioness'' passed under Southwark Bridge, she was hit twice by ''Bowbelle''s bow. The first impact was from ''Marchioness''s stern, which had the effect of turning the smaller vessel to port. The second impact was from the stern, and caused the pleasure boat to pivot round the bow of ''Bowbelle'', and turn it on its side, probably to an angle of 120°. The upper superstructure of ''Marchioness'' was ripped off by ''Bowbelle''s anchor. The lower saloon was quickly flooded and the lights went out. The weight and momentum of ''Bowbelle'' pushed ''Marchioness'' underwater and she sank, stern first, within 30 seconds of being hit. McGowan had been thrown from the boat into the water, but climbed back on board to tie open the port side door, which led to the dance floor, to allow several people to escape. One eyewitness to the crash, Keith Fawkes-Underwood, who viewed the incident from the south bank of the Thames, reported:

The barge collided with the pleasure boat hitting it in about its centre then mounted it, pushing it under the water like a toy boat. Within a matter of about 20 seconds the pleasure boat had totally disappeared underneath the water.Of the 130 people on board ''Marchioness'', 79 survived and 51 died. The dead included de Vasconcellos and Faldo. No-one on ''Bowbelle'' was injured. ''Marchioness'' sank so quickly that most people were unable to locate or use the life rafts, buoys or jackets. Survival of those on ''Marchioness'' depended partly on their location within the vessel. There were 41 people known to have been on the forward deck and wheelhouse, of whom 9 died and 32 survived, a survival rate of 78%. Of the 13 people known to have been in the lower saloon, 9 died and 4 survived (a 31% survival rate). One of those from the lower saloon who survived was Iain Philpott, who said in his statement to the police:

I remember turning around to head towards the windows to escape the boat, the water started coming in the boat through the window, I knew at this point the boat was going to go down. Within a matter of seconds the general lights went out, everything was in darkness ... I was then thrown forward by a wall of water, the whole boat filled with water instantly ... When I surfaced I was some distance away from the Marchioness which was partly submerged.''Hurlingham'' was between 45 and 60 metres (150–200 feet) away from the collision, and those on board were in the best position to be eyewitnesses. George Williams, the vessel's captain, put out a call on VHF radio to the Thames Division of the

Metropolitan Police Service

The Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), formerly and still commonly known as the Metropolitan Police (and informally as the Met Police, the Met, Scotland Yard, or the Yard), is the territorial police force responsible for law enforcement and ...

, based in Wapping

Wapping () is a district in East London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Wapping's position, on the north bank of the River Thames, has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through its riverside public houses and steps, ...

: "Woolwich Police, Wapping Police, Wapping Police, Emergency, pleasure boat is sunk, Cannon Street Railway Bridge, all emergency aid please". The call was also picked up by the TNS, who misheard the location as Battersea Bridge; Thames Division only heard part of the call, so TNS informed them that the police should be in attendance at Battersea Bridge.

After colliding with ''Marchioness'', ''Bowbelle'' hit one of the piers of Cannon Street Bridge, and radioed TNS at 1:48 am to correct the inaccurate reference to Battersea Bridge; at 1:49 am Henderson reported to TNS:

After colliding with ''Marchioness'', ''Bowbelle'' hit one of the piers of Cannon Street Bridge, and radioed TNS at 1:48 am to correct the inaccurate reference to Battersea Bridge; at 1:49 am Henderson reported to TNS:

I have to get underway now and proceed out through bridges. I believe I have struck a pleasure craft. It has sunk. I am getting clear of the bridges now. I was distracted by flashing lights from another pleasure craft. My vessel was proceeding outward bound just approaching Cannon Street bridge and, well, I just lost steerage, um and I don't know after that, I can't really say anything else sir. Over.Transcript of radio transmission from ''Bowbelle'', 1:49 am, quoted inAfter the radio transmission, ''Bowbelle'' travelled downstream to

Gallions Reach

Gallions Reach is a stretch of the River Thames between Woolwich and Thamesmead. The area is named for the Galyons, a 14th-century family who owned property along this stretch of the river,Hidden London http://hidden-london.com/gazetteer/ga ...

, where she dropped anchor. Her crew did not deploy the ship's lifebuoys, flotation devices or lifeboat and she did not take part in the attempts to rescue survivors. All ships in the area were instructed to go to the area to assist with the rescue. ''Hurlingham'' was already on the scene, and the passengers and crew threw lifebuoys and buoyancy aids to those in the water. Many of those from ''Marchioness'' were swept into driftwood collection cages, and ''Hurlingham'' picked up several survivors—the passengers climbing out onto the cages to help people out of the water. The vessel then dropped all passengers and 28 survivors at the nearby Waterloo Police Pier (now Tower Lifeboat Station) before it took members of the emergency service

Emergency services and rescue services are organizations that ensure public safety and health by addressing and resolving different emergencies. Some of these agencies exist solely for addressing certain types of emergencies, while others deal wit ...

s back out to the collision site. Waterloo Police Pier was used as the landing point for all casualties and the first responder

A first responder is a person with specialized training who is among the first to arrive and provide assistance or incident resolution at the scene of an emergency, such as an accident, disaster, medical emergency, structure fire, crime, or terr ...

s from the emergency services set up a treatment and processing point there. Police launches rescued more than half the survivors from the river; some reached the river bank themselves.

Less than half an hour after ''Marchioness'' was hit, a major incident was declared with an incident room at New Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard (officially New Scotland Yard) is the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, the territorial police force responsible for policing Greater London's 32 boroughs, but not the City of London, the square mile that forms London' ...

. The police's body recovery team were also deployed, and the first body arrived at Wapping Police Station—where the Thames Division were based—at 6:50 am. The station acted as a holding area for bodies before they were taken to the mortuary in Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

.

7:00 am – 0:00 am

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

, the Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, returned home early from her holiday in Austria to be briefed by Michael Portillo

Michael Denzil Xavier Portillo (; born 26 May 1953) is a British journalist, broadcaster and former politician. His broadcast series include railway documentaries such as ''Great British Railway Journeys'' and '' Great Continental Railway Journ ...

, the Minister of State

Minister of State is a title borne by politicians in certain countries governed under a parliamentary system. In some countries a Minister of State is a Junior Minister of government, who is assigned to assist a specific Cabinet Minister. In o ...

for Transport

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land (rail and road), water, cable, pipeline, an ...

. His senior in the department, the Secretary of State for Transport

The Secretary of State for Transport, also referred to as the transport secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the policies of the Department for Transport. The incumbent i ...

Cecil Parkinson

Cecil Edward Parkinson, Baron Parkinson, (1 September 1931 – 22 January 2016) was a British Conservative Party politician and cabinet minister. A chartered accountant by training, he entered Parliament in November 1970, and was appointed a ...

, also returned home early in response. Portillo announced that an investigation would be made by the Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB), but that no decision had yet been made as to whether to hold a public inquiry. Within 24 hours of the collision, the decision was made that there would be no public inquiry, and that the MAIB investigation would be sufficient.

A Port of London

The Port of London is that part of the River Thames in England lying between Teddington Lock and the defined boundary (since 1968, a line drawn from Foulness Point in Essex via Gunfleet Old Lighthouse to Warden Point in Kent) with the North Sea ...

(PLA) hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore oil exploration/offshore oil drilling and related activities. Strong emphasis is placed ...

or located the wreckage of ''Marchioness'' and, during the late afternoon of 20 August, work began on lifting the vessel. The bodies of 24 party-goers were found on board, 12 of them in the lower saloon. The wreckage was moored against the north bank of the Thames.

While the lifting operation was progressing, police arrested and interviewed Henderson and Kenneth Noble, ''Bowbelle''s second mate who was at the wheel for the collision. Both men were breathalysed

A breathalyzer or breathalyser (a portmanteau of ''breath'' and ''analyzer/analyser'') is a device for estimating blood alcohol content (BAC), or to detect viruses or diseases from a breath sample.

The name is a genericized trademark of the Br ...

; the police announced soon afterwards that alcohol was not a cause of the collision.

Inquests and inquiries

1989 to 1997

On the day following the collisionPaul Knapman

Paul Knapman DL was Her Majesty's coroner for Westminster (and Inner West London), from 1980 to 2011 (and Deputy Coroner from 1975 to 1980). His responsibility for investigating sudden deaths as an independent judicial officer saw him preside ...

, the coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into Manner of death, the manner or cause of death, and to investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within th ...

for the City of Westminster

The City of Westminster is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and London boroughs, borough in Inner London. It is the site of the United Kingdom's Houses of Parliament and much of the British government. It occupies a large area of cent ...

, opened and adjourned the inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a coro ...

into the deaths. In the days after the collision, bodies were still being found and recovered from the water. To help with the identification process, Knapman opted to use several methods, including dental records, identification of personal items and clothing descriptions from descriptions provided by the families, and fingerprints. As part of their approach, Knapman decided that:

With those bodies which were not recovered from the ''Marchioness'' and which would be likely to surface only when putrification and bloating meant that they would float, the following would apply:During the

post-mortem examination

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any dis ...

s, 25 pairs of hands were removed; no written records were kept of the removal. No guidelines were issued over which hands should be removed and no individual was given responsibility for making the decision. The majority were identified through other means—visual identification of the face, or through identification of clothing or personal items, and only four of the victims were identified through their fingerprints. Families of the victims later complained that they were not told in a timely fashion that bodies had been recovered, that some were denied access to view the bodies of their relatives, and were not told of the processes that would be used—including that the hands would be removed. One family was shown the body of the wrong person, then given the right body, but without the hands; these were sent on later with apologies, and a request not to tell other parents about the need to remove them as this was a 'one-off' mistake.

On 24 August ''Marchioness'' was taken from her mooring near Southwark Bridge, and towed downstream to Greenwich, where she was broken up.

The MAIB issued an interim report towards the end of August, with recommendations as to increasing safety on the Thames. These included a requirement that vessels over had to have a forward lookout in contact with the bridge by radio, and tighter controls on the passage of vessels along the upper Thames. Their investigation continued with a reconstruction of the events on the night of 16–17 September; ''Bowbelle'' took part, and a PLA launch was used as a stand-in for ''Marchioness''. This was later criticised by Brian Toft, a disaster and risk-management expert commissioned by the Marchioness Action Group (MAG), as being unsatisfactory. Toft identified that there were several problems, including no second pleasure cruiser, no fare-paying passengers and no disco lights or music included in the re-enactment.

In October 1989 the companies behind ''Bowbelle'' and ''Marchioness'' agreed to pay up to £6 million in compensation to the families of the victims, without either company admitting any liability for the crash. The sum offered was under a calderbank condition that the offer stood to be withdrawn if a judge awarded a lower amount. A week later a report was compiled for Allan Green

Allan Lamar Green (born September 20, 1979) is an American professional boxer. He is a former NABO super middleweight champion, and has challenged for world titles at both super middleweight and light heavyweight.

Amateur career

Green had a ...

, the Director of Public Prosecutions

The Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) is the office or official charged with the prosecution of criminal offences in several criminal jurisdictions around the world. The title is used mainly in jurisdictions that are or have been members o ...

(DPP), which recommended that criminal charges should not be brought against Henderson.

That December, Knapman met the DPP to discuss the progress of the inquests. Green agreed that the first part of the inquest should go ahead—dealing with the causes of death—irrespective of the other investigations of the police and the possibility of later criminal charges. A second part of the inquest—establishing the responsibility of the crash and making safety recommendations—would be discussed at a later stage. When Knapman re-opened the inquest on 23 April 1990, he was critical of the DPP for taking eight months to decide on whether to bring criminal charges against anyone, which meant that a full inquest could not take place in case it prejudiced any future trial. The inquest was, in effect, a series of what the legal scholar Hazel Hartley calls "mini inquests", one each for each of the 51 bodies.

On 26 April the DPP stepped in to stop the inquest, stating that charges would now be brought against Henderson. Because of his decision to stop the inquest, the information on how the collision occurred, who was to blame or what could be done to ensure it could not be repeated, was not considered. Henderson was charged under the Merchant Shipping Act 1988

The Merchant Shipping Act 1988 c.12 was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom. It aimed to prevent foreign fishing fleets from fishing in British territorial waters. In the Factortame case, its provisions in Parts I and II, Registration of ...

for failing to have an effective lookout on the vessel. The case against him opened on 4 April 1991 at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

and ran to 14 April. The jury failed to reach a decision; the DPP decided that a retrial would be in the public interest. This took place between 17 and 31 July the same year; it again ended with a hung jury.

At the end of July 1991 Ivor , the husband of one of the victims, began a private prosecution for manslaughter

Manslaughter is a common law legal term for homicide considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is sometimes said to have first been made by the ancient Athenian lawmaker Draco in the 7th ce ...

against four directors of South Coast Shipping Company, the owners of ''Bowbelle'', and corporate manslaughter

Corporate manslaughter is a crime in several jurisdictions, including England and Wales and Hong Kong. It enables a corporation to be punished and censured for culpable conduct that leads to a person's death. This extends beyond any compensation t ...

against the South Coast Shipping Company. Two weeks later the Transport Secretary, Malcolm Rifkind

Sir Malcolm Leslie Rifkind (born 21 June 1946) is a British politician who served in the cabinets of Margaret Thatcher and John Major from 1986 to 1997, and most recently as chair of the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament from 2 ...

, took the decision to publish the MAIB Report, repeating that because an appropriate body had undertaken an investigation, there was no requirement to have a public inquiry. Families of the victims were angry with the move, pointing out that Rifkind had delayed publication of the report on the basis that publication could prejudice the case against Henderson, but that the publication could now jeopardise private prosecution. The DPP demanded that hand over the papers for the case, stating he would take it over, then drop it; refused to comply, stating that it was out of the remit of the DPP, and that it was for a magistrates' court to decide if the case was adequate. The DPP withdrew and allowed case to proceed. The case was dismissed after the magistrate stated that there was insufficient evidence.

The MAIB report considered that ''Marchioness'' had altered her course to port, which put her in line with ''Bowbelle''s path. The report concluded that:

The MAIB report considered that ''Marchioness'' had altered her course to port, which put her in line with ''Bowbelle''s path. The report concluded that:

18.3 ... no one in either vessel was aware of the other's presence until very shortly before the collision. No one on the bridge of BOWBELLE was aware of MARCHIONESS until the collision occurred. 18.4 The principal contributory factors were that:The families of the victims criticised the MAIB report. They pointed out that the investigation had not directly interviewed anyone on ''Marchioness'' or ''Bowbelle'', but relied on the police interviews; they stated that there were errors in methodology, approach and fact within the report. Toft provided a critique of the MAIB's work and concluded that:

The inconsistencies, contradictions, confusions, conjecture, erroneous conclusions, missing and inappropriate recommendations as well as epistemological, ontological and methodological problems, created by the then current maritime safety culture ... raises serious doubts as to the objectivity of the investigation, the validity of the findings, the judgement of the Department of Transport in holding an inquiry of this type, and as a result whether or not all the appropriate lessons were uncovered during the MAIB's inquiry into this tragedy.The report was handed to Rifkind, who again declined to open a public inquiry, but commissioned a private one—the Hayes Report, published in July 1992—that looked at health and safety on the Thames, rather than the sinking of ''Marchioness''. In 1992 the families of the victims became aware that the hands had been removed from many of the bodies. In March that year an account in ''

The Mail on Sunday

''The Mail on Sunday'' is a British conservative newspaper, published in a tabloid format. It is the biggest-selling Sunday newspaper in the UK and was launched in 1982 by Lord Rothermere. Its sister paper, the '' Daily Mail'', was first pu ...

'', "Cover up!", was published; when Knapman met the two journalists to deny the accusation of a cover-up, he advised them not to base reports on what Margaret Lockwood-Croft, the mother of one of the victims, said: he described her as "unhinged". He also showed them photographs of the victims, without discussing the matter with the families. In July, Knapman informed the families that the inquests—suspended since April 1990 because of the case against Henderson—would not be recommenced. The families tried to apply for a judicial review

Judicial review is a process under which executive, legislative and administrative actions are subject to review by the judiciary. A court with authority for judicial review may invalidate laws, acts and governmental actions that are incompat ...

on the basis that "the use of the word 'unhinged' and reference to a number of 'mentally unwell' relatives betrayed an attitude of hostility, however unconscious, towards ... members of the Marchioness Action Group". Initially turned down by High Court, the Court of Appeal

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of t ...

then found in favour of the group to allow an appeal. In June 1994 Knapman and his assistant were stood down and replaced by another coroner, John Burton. He was initially dismissive of the concerns of the MAG, accused their solicitor of trying to mislead the Court of Appeal and indicated that he was inclined not to grant any further inquests. Burton was told that another judicial review would be applied for if he refused to hold the inquests, and he subsequently announced that they would go ahead.

The resumed inquest took place in March and April 1995. When questioned about the MAIB report, Captain James de Coverley—one of the report's authors—withdrew the suggestion that ''Marchioness'' had steered to port in the last moments before the crash, saying it had never been his intention that the text could be understood that way. In summing up, Burton instructed the coroner's jury that a verdict of unlawful killing

In English law, unlawful killing is a verdict that can be returned by an inquest in England and Wales when someone has been killed by one or more unknown persons. The verdict means that the killing was done without lawful excuse and in breach of ...

could not be applied to anyone who had already been cleared by a court. The jury retired for four hours and returned a verdict of unlawful killing. Burton asked them "Did you understand my Direction?", although the decision stood.

1997 to 2001

Following the 1997 election, which brought the Labour Party to power, the MAG petitionedJohn Prescott

John Leslie Prescott, Baron Prescott (born 31 May 1938) is a British politician who served as Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and as First Secretary of State from 2001 to 2007. A member of the Labour Party, he w ...

, the Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions

The Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions was a United Kingdom Cabinet position created in 1997, with responsibility for the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR). The position and department ...

and Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to that of a vice president, ...

, to open an inquest. In August 1999 he instructed Lord Justice Clarke to undertake a non-statutory inquiry into safety on the Thames. Clarke reported in February 2000, concluding:

I was asked to advise My answer to that question is yes.

Prescott accepted the recommendation and the public inquest took place in October and November 2000, with Clarke chairing proceedings; the report was published in March 2001. Clarke concluded that "The basic cause of the collision is clear. It was poor lookout on both vessels. Neither vessel saw the other in time to take action to avoid the collision." The underlying causes on why neither vessel saw the other were that Henderson did not ensure a proper lookout on ''Bowbelle''; that Blayney the lookout was not equipped with suitable radio equipment to inform his captain; that Faldo had not set up a lookout system on ''Marchioness'', nor did he keep a lookout aft himself. Focusing on Henderson, Clarke wrote "We cannot stress too strongly how much we deprecate Captain Henderson's conduct in drinking so much alcohol before returning to his vessel as master"; Clarke added "but we do not think that it is shown on the balance of probabilities that Captain Henderson would have acted differently if he had not consumed the alcohol or had the amount of sleep which he had". The captain was also criticised for his actions after the collision, when he did not broadcast a

Prescott accepted the recommendation and the public inquest took place in October and November 2000, with Clarke chairing proceedings; the report was published in March 2001. Clarke concluded that "The basic cause of the collision is clear. It was poor lookout on both vessels. Neither vessel saw the other in time to take action to avoid the collision." The underlying causes on why neither vessel saw the other were that Henderson did not ensure a proper lookout on ''Bowbelle''; that Blayney the lookout was not equipped with suitable radio equipment to inform his captain; that Faldo had not set up a lookout system on ''Marchioness'', nor did he keep a lookout aft himself. Focusing on Henderson, Clarke wrote "We cannot stress too strongly how much we deprecate Captain Henderson's conduct in drinking so much alcohol before returning to his vessel as master"; Clarke added "but we do not think that it is shown on the balance of probabilities that Captain Henderson would have acted differently if he had not consumed the alcohol or had the amount of sleep which he had". The captain was also criticised for his actions after the collision, when he did not broadcast a mayday

Mayday is an emergency procedure word used internationally as a distress signal in voice-procedure radio communications.

It is used to signal a life-threatening emergency primarily by aviators and mariners, but in some countries local organiza ...

call and did not deploy either the lifebuoys or life raft, in contravention of section 422 of the Merchant Shipping Act 1894. Clarke also found that the owners and managers of the vessels held some blame. For ''Bowbelle'', the owners "must bear their share of responsibility for the collision for failing properly to instruct their masters and crews and for failing thereafter to monitor them"; the owners of ''Marchioness'' gave no instructions about all-round lookouts; and failed to adequately instruct, supervise or monitor their boats' captains.

Clarke also allotted blame to the Department of Transport, who, he said, were "well aware of the problems posed by the limited visibility from the steering positions on both types of vessel" yet failed to deal with the problem. The PLA also failed to act in this regard, and should have issued instructions for the placement of lookouts on such vessels. Clarke found that because no individual's actions could be ascertained as the single cause of the collision, a manslaughter charge would be bound to fail.

Compensation

English law provides no compensation for fatal accidents, other than for funeral expenses, unless financial dependency at the time of death can be proved. In most cases, the families of the ''Marchioness'' victims received little more than the cost of the funeral.

English law provides no compensation for fatal accidents, other than for funeral expenses, unless financial dependency at the time of death can be proved. In most cases, the families of the ''Marchioness'' victims received little more than the cost of the funeral. Louise Christian

Louise Hilda Christian (born 22 May 1952, Oxford) is a British human rights solicitor. She is the daughter of Jack and Maureen Christian.

Christian was admitted to the Law Society as a solicitor on 16 January 1978. In 1985,The ''Telegraph'' ar ...

, the human rights solicitor who acted for the families of the victims, wrote that "When young unmarried people die in circumstances of gross negligence as here, death comes cheap and the boat owners and their insurance companies suffer little in the way of financial penalties".

Civil claims for compensation were brought on behalf of the victims' families; the amounts received ranged between £3,000 and £190,000. Eileen Dallaglio, the mother of Francesca Dallaglio, one of the victims, reported that she had been awarded £45,000. After the costs of having to go to the Court of Appeal to obtain damages, and the bills for the memorial and funeral service, she was left with £312.14. According to Irwin Mitchell

Irwin Mitchell is a full service law firm in the United Kingdom, established in Sheffield in 1912. The firm offers legal and wealth management services from its 17 offices, and employs more than 2,500 people.

In 2018 the company was ranked 21st ...

, the solicitors who represented the families, the amounts were "modest" because many of those killed were young, without dependants and had no established careers. Under the Fatal Accidents Act 1976

The Fatal Accidents Act 1976 (c 30) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, that allows relatives of people killed by the wrongdoing of others to recover damages.

Background

The Fatal Accidents Act 1846 had allowed claims for damages ...

, damages were only paid to certain categories of people, and were based on the economic loss

Economic loss is a term of art which refers to financial loss and damage suffered by a person which is seen only on a balance sheet and not as physical injury to person or property. There is a fundamental distinction between pure economic loss and ...

to the victim.

Aftermath

After recommendations made in the Clarke report relating to the improvement of river safety, the government asked the

After recommendations made in the Clarke report relating to the improvement of river safety, the government asked the Maritime and Coastguard Agency

The Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) is an executive agency of the United Kingdom that responsible for implementing British and international maritime law and safety policy. It works to prevent the loss of lives at sea and to prevent marine ...

(MCA), the PLA and the Royal National Lifeboat Institution

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) is the largest charity that saves lives at sea around the coasts of the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, the Channel Islands, and the Isle of Man, as well as on some inland waterways. It i ...

(RNLI) to work together to set up a dedicated search and rescue

Search and rescue (SAR) is the search for and provision of aid to people who are in distress or imminent danger. The general field of search and rescue includes many specialty sub-fields, typically determined by the type of terrain the search ...

service for the Thames. In January 2001 the RNLI agreed to set up four lifeboat stations—at Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Ro ...

, Tower

A tower is a tall Nonbuilding structure, structure, taller than it is wide, often by a significant factor. Towers are distinguished from guyed mast, masts by their lack of guy-wires and are therefore, along with tall buildings, self-supporting ...

, Chiswick

Chiswick ( ) is a district of west London, England. It contains Hogarth's House, the former residence of the 18th-century English artist William Hogarth; Chiswick House, a neo-Palladian villa regarded as one of the finest in England; and Full ...

and Teddington

Teddington is a suburb in south-west London in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. In 2021, Teddington was named as the best place to live in London by ''The Sunday Times''. Historically in Middlesex, Teddington is situated on a long m ...

—which were opened in January the following year.

Following the report, Prescott ordered the MCA to conduct a competency review into the actions and behaviour of Henderson. This took place in December 2001. The MCA picked up on something that had been raised during the Clarke inquiry: that Henderson had forged certificates and testimonials of his service from 1985–1986. They stated that they "deplored" the forgeries, which Henderson had used to gain his Master's Licence. The MCA concluded that he should be allowed to keep his master's certificate as he met all the service and medical fitness requirements; they stated that the agency "accepted that events which occurred in 1986 have no practical relevance on his current fitness".

In 2001 the

In 2001 the Royal Humane Society

The Royal Humane Society is a British charity which promotes lifesaving intervention. It was founded in England in 1774 as the ''Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned'', for the purpose of rendering first aid in cases of near dro ...

made nineteen bravery awards to people involved in rescuing the victims of the collision, many of whom were passengers on ''Hurlingham''. Eight policemen on duty that night were given the Metropolitan Police Commissioner's High Commendation.

Following the Clarke report and a subsequent review of emergency planning procedures, the government introduced the Civil Contingencies Act 2004

The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (c. 36) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that makes provision about civil contingencies. It also replaces former Civil Defence and Emergency Powers legislation of the 20th century.

Background to ...

that provided a coherent framework and guidance for emergency planning and response. Clarke's recommendations to examine the coroner system were a major factor in the overhaul of the system that resulted in the Coroners and Justice Act 2009.

The events surrounding the sinking of ''Marchioness'' have been examined or depicted on television several times, including a documentary on Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network operated by the state-owned enterprise, state-owned Channel Four Television Corporation. It began its transmission on 2 November 1982 and was established to provide a four ...

's '' Dispatches'' in December 1994, a drama-documentary in the BBC Two

BBC Two is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network owned and operated by the BBC. It covers a wide range of subject matter, with a remit "to broadcast programmes of depth and substance" in contrast to the more mainstream an ...

series ''Disaster'' in March 1999 and a 2009 documentary focusing on Jonathan Phang. A drama about the events surrounding the disaster was scheduled for broadcast on ITV

ITV or iTV may refer to:

ITV

*Independent Television (ITV), a British television network, consisting of:

** ITV (TV network), a free-to-air national commercial television network covering the United Kingdom, the Isle of Man, and the Channel Islan ...

in late 2007. Some of the victims' families requested that the programme should not be broadcast, although some thought it positive that it was going to be shown. Speaking at the Edinburgh International Television Festival

The Edinburgh International Television Festival is an annual media event held in the United Kingdom each August which brings together delegates from the television and digital world to debate the major issues facing the industry.

The Festival ...

that August, the former ITV Director of Drama Nick Elliot confirmed that the drama would not be shown "in its present form"; it has since been shown on French television.

In September 1989 a black granite memorial stone was uncovered in the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

of Southwark Cathedral

Southwark Cathedral ( ) or The Cathedral and Collegiate Church of St Saviour and St Mary Overie, Southwark, London, lies on the south bank of the River Thames close to London Bridge. It is the mother church of the Anglican Diocese of Southwark. ...

, about from the site of the collision. The stone lists the names and ages of those who died. Memorial services have been held at the cathedral on anniversaries of the sinking.

''Bowbelle'' was sold in 1992 to Sealsands Maritime, operating out of Kingstown

Kingstown is the capital, chief port, and main commercial centre of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. With a population of 12,909 (2012), Kingstown is the most populous settlement in the country. It is the island's agricultural industry centre ...

, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines () is an island country in the Caribbean. It is located in the southeast Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles, which lie in the West Indies at the southern end of the eastern border of the Caribbean Sea wh ...

; she was renamed ''Billo''. Four years later she was sold to Antonio Pereira & Filhos of Funchal

Funchal () is the largest city, the municipal seat and the capital of Portugal's Madeira, Autonomous Region of Madeira, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean. The city has a population of 105,795, making it the sixth largest city in Portugal. Because of ...

, Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

, who named the vessel ''Bom Rei''. She broke in two and sank off Madeira the same year with the loss of one crew member.

See also

* List of disasters in Great Britain and Ireland by death toll *2021 Baltic Sea incident

On 13 December 2021, one person was killed in an incident in the Baltic Sea off the coast of Sweden. Two vessels collided of which one capsized. Two people have been detained.

Events

The Danish motor hopper cargo vessel MV ''Karin Høj'' collid ...

Notes and references

Notes

References

Sources

Books

* * * * * * * *Reports

* * * * * * * * * *Journals

* * * * *News articles

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Internet

* * * * * *External links

Marchioness-Bowbelle Formal Investigation Website

In the UK Government Web Archive *

Marchioness Action Group

{{authority control Maritime incidents in 1989 Maritime incidents in England Shipwrecks of the River Thames History of the River Thames History of the City of London Port of London 1989 disasters in the United Kingdom 20th century in the London Borough of Southwark Transport disasters in London 1989 in London August 1989 events in the United Kingdom Little Ships of Dunkirk