Morgan Le Fay on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Morgan le Fay (, meaning 'Morgan the Fairy'), alternatively known as Morgan ''n''a, Morgain ''a/e Morg ''a''ne, Morgant ''e Morge ''i''n, and Morgue ''inamong other names and spellings ( cy, Morgên y Dylwythen Deg, kw, Morgen an Spyrys), is a powerful and ambiguous enchantress from the legend of King Arthur, in which most often she and he are siblings. Early appearances of Morgan in Arthurian literature do not elaborate her character beyond her role as a goddess, a

The earliest spelling of the name (found in

The earliest spelling of the name (found in

The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy

'' (Greenwood Press, 2000), pp. 32–45. derived from the continental

Morgan first appears by name in ''

Morgan first appears by name in '' In '' Jaufre'', an early

In '' Jaufre'', an early  The 12th-century French poet

The 12th-century French poet  The

The

Morgan's role was greatly expanded by the unknown authors of the early-13th-century

Morgan's role was greatly expanded by the unknown authors of the early-13th-century

In a popular tradition from later evolution of this narrative, Morgan is the youngest of the daughters of Igraine and

In a popular tradition from later evolution of this narrative, Morgan is the youngest of the daughters of Igraine and

Uther (or Arthur himself in the Post-Vulgate) betroths her to his ally, King

Uther (or Arthur himself in the Post-Vulgate) betroths her to his ally, King  In the Post-Vulgate, where Morgan's explicitly evil nature is stated and accented, she also works to destroy Arthur's rule and end his life, but the reasons for her initial hatred of him are never fully explained other than just an extreme antipathy towards the perfect goodness which he symbolises. The most famous and important of these machinations is introduced in the Post-Vulgate ''Suite'', where she arranges for her devoted lover

In the Post-Vulgate, where Morgan's explicitly evil nature is stated and accented, she also works to destroy Arthur's rule and end his life, but the reasons for her initial hatred of him are never fully explained other than just an extreme antipathy towards the perfect goodness which he symbolises. The most famous and important of these machinations is introduced in the Post-Vulgate ''Suite'', where she arranges for her devoted lover  Morgan also uses her skills in dealing with various of Arthur's

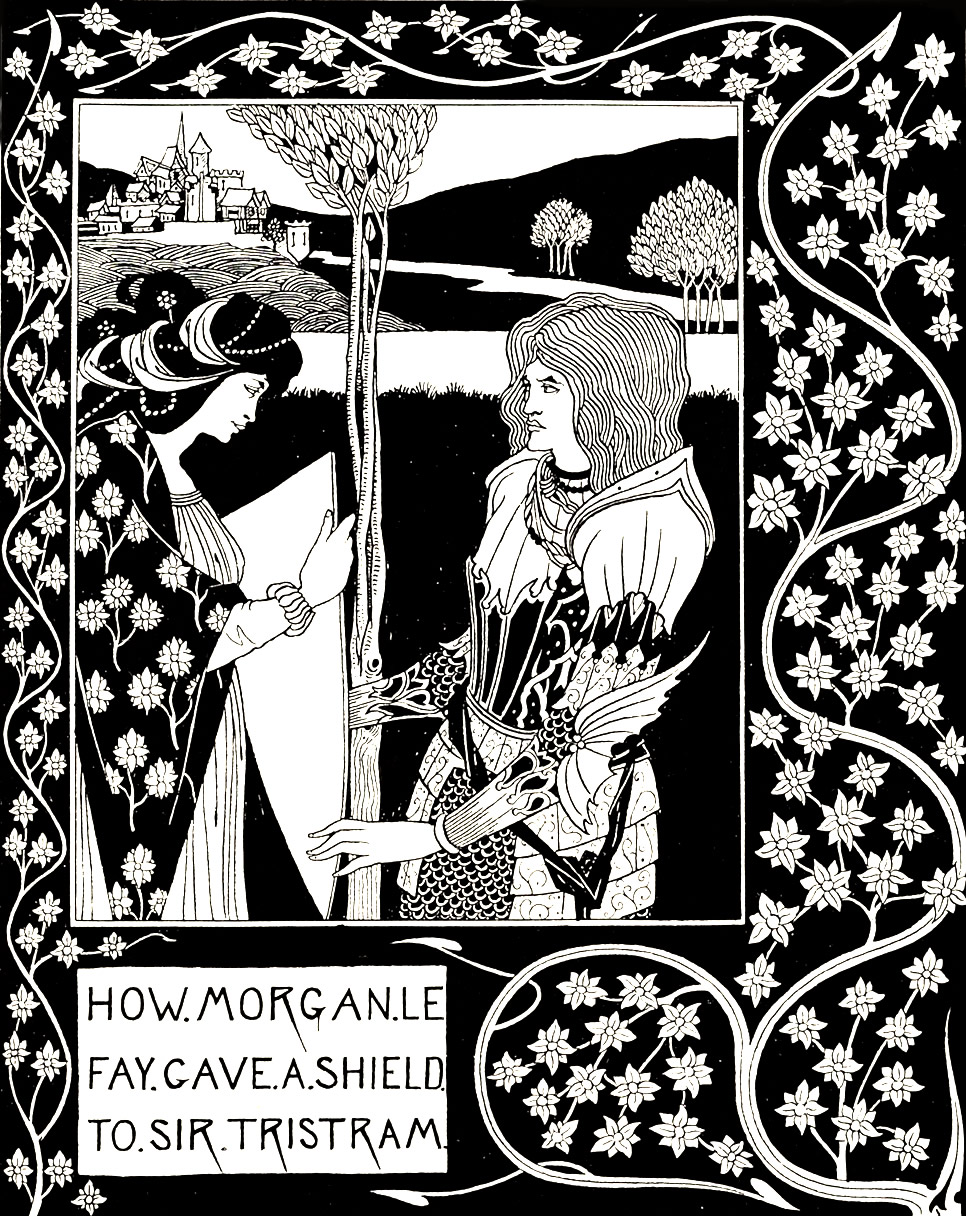

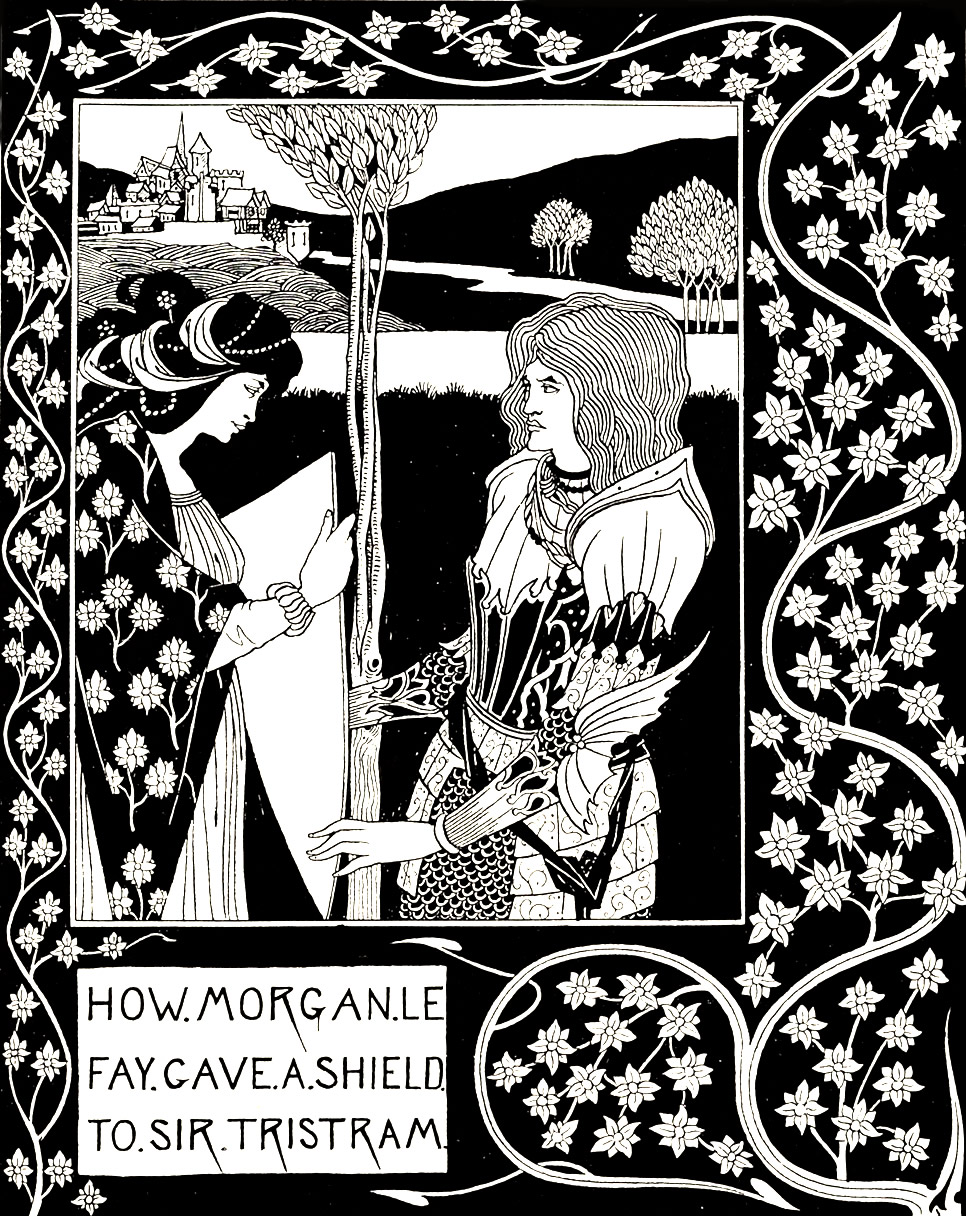

Morgan also uses her skills in dealing with various of Arthur's  Besides Lancelot, Morgan's fancied good knights include Tristan, but her interest in him turns into burning hatred of him and his true love Isolde after he kills her lover as introduced in the Prose ''Tristan'' (Morgan does not become their enemy in the Italian versions). Another is the rescued-but-abducted young Alexander the Orphan (Alisaunder le Orphelin), a cousin of Tristan and Mark's enemy from a later addition in the Prose ''Tristan'' as well as the ''Prophéties de Merlin'', whom she promises to heal but he vows to castrate himself rather than to pleasure her. Nevertheless, Alexander promises to defend her castle of Fair Guard (''Belle Garde''), where he has been held, for a year and a day, and then dutifully continues to guard it even after the castle gets burned down; this eventually leads to his death. In the Val sans Retour, Lancelot frees the 250 unfaithful knights entrapped by Morgan, including Morgan's own son Yvain and her former lover Guiomar whom she has turned to stone for his infidelity. (Of note, Guiomar, appearing there as Gaimar, is also Guinevere's early lover instead of her cousin in the German version ''Lancelot und Ginevra''.) Morgan then captures Lancelot himself under her spell using a magic ring and keeps him prisoner in the hope Guinevere would then go mad or die of sorrow. She also otherwise torments Guinevere, causing her great distress and making her miserable until the Lady of the Lake gives her a ring that protects her from Morgan's power. On one occasion, she lets the captive Lancelot go to rescue Gawain when he promises to come back (but also keeping him the company of "the most beautiful of her maidens" to do "whatever she could to entice him"), and he keeps his word and does return; she eventually releases him altogether after over a year, when his health falters and he is near death. It is said that Morgan concentrates on witchcraft to such degree that she goes to live in seclusion in the exile of far-away forests. She learns more spells than any other woman, gains an ability to transform herself into any animal, and people begin to call her Morgan the Goddess (''Morgain-la-déesse'', ''Morgue la dieuesse'').Larrington, ''King Arthur's Enchantresses'', p. 13. In the Post-Vulgate version of ''Queste del Saint Graal'', Lancelot has a vision of Hell where Morgan still will be able to control demons even in afterlife as they torture Guinevere. Later, after she hosts her nephews Gawain, Mordred and Gaheriet to heal them, Mordred spots the images of Lancelot's passionate love for Guinevere that Lancelot painted on her castle's walls while he was imprisoned there; Morgan shows them to Gawain and his brothers, encouraging them to take action in the name of loyalty to their king, but they do not do this. With same intent, when Tristan was to be Morgan's

Besides Lancelot, Morgan's fancied good knights include Tristan, but her interest in him turns into burning hatred of him and his true love Isolde after he kills her lover as introduced in the Prose ''Tristan'' (Morgan does not become their enemy in the Italian versions). Another is the rescued-but-abducted young Alexander the Orphan (Alisaunder le Orphelin), a cousin of Tristan and Mark's enemy from a later addition in the Prose ''Tristan'' as well as the ''Prophéties de Merlin'', whom she promises to heal but he vows to castrate himself rather than to pleasure her. Nevertheless, Alexander promises to defend her castle of Fair Guard (''Belle Garde''), where he has been held, for a year and a day, and then dutifully continues to guard it even after the castle gets burned down; this eventually leads to his death. In the Val sans Retour, Lancelot frees the 250 unfaithful knights entrapped by Morgan, including Morgan's own son Yvain and her former lover Guiomar whom she has turned to stone for his infidelity. (Of note, Guiomar, appearing there as Gaimar, is also Guinevere's early lover instead of her cousin in the German version ''Lancelot und Ginevra''.) Morgan then captures Lancelot himself under her spell using a magic ring and keeps him prisoner in the hope Guinevere would then go mad or die of sorrow. She also otherwise torments Guinevere, causing her great distress and making her miserable until the Lady of the Lake gives her a ring that protects her from Morgan's power. On one occasion, she lets the captive Lancelot go to rescue Gawain when he promises to come back (but also keeping him the company of "the most beautiful of her maidens" to do "whatever she could to entice him"), and he keeps his word and does return; she eventually releases him altogether after over a year, when his health falters and he is near death. It is said that Morgan concentrates on witchcraft to such degree that she goes to live in seclusion in the exile of far-away forests. She learns more spells than any other woman, gains an ability to transform herself into any animal, and people begin to call her Morgan the Goddess (''Morgain-la-déesse'', ''Morgue la dieuesse'').Larrington, ''King Arthur's Enchantresses'', p. 13. In the Post-Vulgate version of ''Queste del Saint Graal'', Lancelot has a vision of Hell where Morgan still will be able to control demons even in afterlife as they torture Guinevere. Later, after she hosts her nephews Gawain, Mordred and Gaheriet to heal them, Mordred spots the images of Lancelot's passionate love for Guinevere that Lancelot painted on her castle's walls while he was imprisoned there; Morgan shows them to Gawain and his brothers, encouraging them to take action in the name of loyalty to their king, but they do not do this. With same intent, when Tristan was to be Morgan's  In the Vulgate ''La Mort le Roi Artu'' (''The Death of King Arthur'', also known as just the ''Mort Artu''), Morgan ceases troubling Arthur and vanishes for a long time, and Arthur assumes her to be dead. But one day, he wanders into Morgan's remote castle while on a hunting trip, and they meet and instantly reconcile with each other. Morgan welcomes him warmly and the king, overjoyed with their reunion, allows her to return to Camelot, but she refuses and declares her plan to move to the Isle of Avalon, "where the women live who know all the world's magic," to live there with other sorceresses. However, disaster strikes when the sight of Lancelot's frescoes and Morgan's confession finally convinces Arthur about the truth to the rumours of the two's secret love affair (about which he has been already warned by his nephew Agravain). This leads to a great conflict between Arthur and Lancelot, which brings down the fellowship of the

In the Vulgate ''La Mort le Roi Artu'' (''The Death of King Arthur'', also known as just the ''Mort Artu''), Morgan ceases troubling Arthur and vanishes for a long time, and Arthur assumes her to be dead. But one day, he wanders into Morgan's remote castle while on a hunting trip, and they meet and instantly reconcile with each other. Morgan welcomes him warmly and the king, overjoyed with their reunion, allows her to return to Camelot, but she refuses and declares her plan to move to the Isle of Avalon, "where the women live who know all the world's magic," to live there with other sorceresses. However, disaster strikes when the sight of Lancelot's frescoes and Morgan's confession finally convinces Arthur about the truth to the rumours of the two's secret love affair (about which he has been already warned by his nephew Agravain). This leads to a great conflict between Arthur and Lancelot, which brings down the fellowship of the

Middle English writer

Middle English writer  In Malory's backstory, Morgan has studied astrology as well as ''nigremancie'' (which might actually mean

In Malory's backstory, Morgan has studied astrology as well as ''nigremancie'' (which might actually mean  In the English poem Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'', Morgan appears in Arthur's dream as Lady Fortune (that is, the goddess

In the English poem Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'', Morgan appears in Arthur's dream as Lady Fortune (that is, the goddess

Morgan further turns up frequently throughout the Western European literature of the High and

Morgan further turns up frequently throughout the Western European literature of the High and  In the legends of Charlemagne, she is associated with the Danish legendary hero and one of the Paladins,

In the legends of Charlemagne, she is associated with the Danish legendary hero and one of the Paladins,  The island of Avalon is often described as an otherworldly place ruled by Morgan in other later texts from all over Western Europe, especially these written in

The island of Avalon is often described as an otherworldly place ruled by Morgan in other later texts from all over Western Europe, especially these written in  Morgan le Fay, or Fata Morgana in Italian, has been in particular associated with

Morgan le Fay, or Fata Morgana in Italian, has been in particular associated with  During the

During the

Morgan le Fay

at The Camelot Project * {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan Le Fay Arthurian characters Fairy royalty Female characters in literature Female literary villains Fictional astronomers Fictional characters introduced in the 12th century Fictional characters who use magic Fictional characters with immortality Fictional Christian nuns Fictional giants Fictional goddesses Fictional kidnappers Fictional mathematicians Fictional prophets Fictional shapeshifters Fictional Welsh people Fictional witches King Arthur's family Literary archetypes by name Matter of France Merlin Mythological princesses Mythological queens People whose existence is disputed Supernatural legends Witchcraft in folklore and mythology

fay

A fairy (also fay, fae, fey, fair folk, or faerie) is a type of mythical being or legendary creature found in the folklore of multiple European cultures (including Celtic, Slavic, Germanic, English, and French folklore), a form of spirit, o ...

, a witch

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have u ...

, or a sorceress, generally benevolent and connected to Arthur as his magical saviour and protector. Her prominence increased as legends developed over time, as did her moral ambivalence, and in some texts there is an evolutionary transformation of her to an antagonist, particularly as portrayed in cyclical prose such as the ''Lancelot-Grail

The ''Lancelot-Grail'', also known as the Vulgate Cycle or the Pseudo-Map Cycle, is an early 13th-century French Arthurian literary cycle consisting of interconnected prose episodes of chivalric romance in Old French. The cycle of unknown aut ...

'' and the Post-Vulgate Cycle

The ''Post-Vulgate Cycle'', also known as the Post-Vulgate Arthuriad, the Post-Vulgate ''Roman du Graal'' (''Romance of the Grail'') or the Pseudo-Robert de Boron Cycle, is one of the major Old French prose cycles of Arthurian literature from the ...

. A significant aspect in many of Morgan's medieval and later iterations is the unpredictable duality of her nature, with potential for both good and evil.

Her character may have originated from Welsh mythology

Welsh mythology (Welsh language, Welsh: ''Mytholeg Cymru'') consists of both folk traditions developed in Wales, and traditions developed by the Celtic Britons elsewhere before the end of the first millennium. As in most of the predominantly oral ...

as well as from other ancient myths and historical figures. The earliest documented account, by Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

in ''Vita Merlini

''Vita Merlini'', or ''The Life of Merlin'', is a Latin poem in 1,529 hexameter lines written around the year 1150. Though doubts have in the past been raised about its authorship it is now widely believed to be by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It tel ...

'' (written ) refers to Morgan in conjunction with the Isle of Apples (Avalon

Avalon (; la, Insula Avallonis; cy, Ynys Afallon, Ynys Afallach; kw, Enys Avalow; literally meaning "the isle of fruit r appletrees"; also written ''Avallon'' or ''Avilion'' among various other spellings) is a mythical island featured in th ...

), to which Arthur was carried after having been fatally wounded at the Battle of Camlann

The Battle of Camlann ( cy, Gwaith Camlan or ''Brwydr Camlan'') is the legendary final battle of King Arthur, in which Arthur either died or was fatally wounded while fighting either with or against Mordred, who also perished. The original l ...

, as the leader of the nine magical sisters unrelated to Arthur. Therein, and in the early chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of High Medieval and Early Modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalr ...

s by Chrétien de Troyes

Chrétien de Troyes (Modern ; fro, Crestien de Troies ; 1160–1191) was a French poet and trouvère known for his writing on Arthurian subjects, and for first writing of Lancelot, Percival and the Holy Grail. Chrétien's works, including ...

and others, Morgan's chief role is that of a great healer. Several of numerous and often unnamed fairy-mistress and maiden-temptress characters found through the Arthurian romance genre may also be considered as appearances of Morgan in her different aspects.

Romance authors of the late 12th century establish her as Arthur's supernatural elder sister. In the early 13th-century, Robert de Boron

Robert de Boron (also spelled in the manuscripts "Roberz", "Borron", "Bouron", "Beron") was a French poet of the late 12th and early 13th centuries, notable as the reputed author of the poems and ''Merlin''. Although little is known of him apart ...

-derived Arthurian prose cycles – and the later works based on them in turn, including among them Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of '' Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of '' Le Morte d' ...

's influential '' Le Morte d'Arthur'' – Morgan is usually described as the youngest daughter of Arthur's mother, Igraine

In the Matter of Britain, Igraine () is the mother of King Arthur. Igraine is also known in Latin as Igerna, in Welsh as Eigr ( Middle Welsh Eigyr), in French as Ygraine (Old French Ygerne or Igerne), in '' Le Morte d'Arthur'' as Ygrayne—of ...

, and of her first husband, Gorlois

In Arthurian legend, Gorlois ( cy, Gwrlais) of Tintagel, Duke of Cornwall, is the first husband of Igraine, whose second husband is Uther Pendragon. Gorlois's name first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' (). A vas ...

. Arthur, son of Igraine and Uther, is thus Morgan's half-brother; the Queen of Orkney is one of Morgan's sisters and Mordred

Mordred or Modred (; Welsh: ''Medraut'' or ''Medrawt'') is a figure who is variously portrayed in the legend of King Arthur. The earliest known mention of a possibly historical Medraut is in the Welsh chronicle ''Annales Cambriae'', wherein h ...

's mother. Morgan unhappily marries Urien

Urien (; ), often referred to as Urien Rheged or Uriens, was a late 6th-century king of Rheged, an early British kingdom of the Hen Ogledd (today's northern England and southern Scotland) of the House of Rheged. His power and his victories, ...

, with whom she has a son, Yvain

Sir Ywain , also known as Yvain and Owain among other spellings (''Ewaine'', ''Ivain'', ''Ivan'', ''Iwain'', ''Iwein'', ''Uwain'', ''Uwaine'', etc.), is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend, wherein he is often the son of King Uri ...

. She becomes an apprentice of Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

, and a capricious and vindictive adversary of some knights of the Round Table

The Round Table ( cy, y Ford Gron; kw, an Moos Krenn; br, an Daol Grenn; la, Mensa Rotunda) is King Arthur's famed table in the Arthurian legend, around which he and his knights congregate. As its name suggests, it has no head, implying tha ...

, all the while harbouring a special hatred for Arthur's wife Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; cy, Gwenhwyfar ; br, Gwenivar, kw, Gwynnever), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First me ...

. In this tradition, she is also sexually active and even predatory, taking numerous lovers that may include Merlin and Accolon

Accolon is a character in Arthurian legends where he is a lover of Morgan le Fay who is killed by King Arthur in a duel during the plot involving the sword Excalibur. He appears in Arthurian prose romances since the Post-Vulgate Cycle, includ ...

, with an unrequited love for Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), also written as Launcelot and other variants (such as early German ''Lanzelet'', early French ''Lanselos'', early Welsh ''Lanslod Lak'', Italian ''Lancillotto'', Spanish ''Lanzarote del Lago' ...

. In some variants, including in the popular retelling by Malory, Morgan is the greatest enemy of Arthur, scheming to usurp his throne and indirectly becoming an instrument of his death; however, she eventually reconciles with Arthur, retaining her original role of taking him on his final journey to Avalon.

Many other medieval and Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

works feature continuations of her evolutionary tale from the aftermath of Camlann as she becomes the immortal queen of Avalon in both Arthurian and non-Arthurian stories, sometimes alongside Arthur. After a period of being largely absent from contemporary culture, Morgan's character again rose to prominence in the 20th and 21st centuries, appearing in a wide variety of roles and portrayals. Notably, her modern character is frequently being conflated with her sister's as mother of Arthur's son and nemesis Mordred, the status that Morgan herself has never had in medieval legend.

Etymology and origins

The earliest spelling of the name (found in

The earliest spelling of the name (found in Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

's ''Vita Merlini

''Vita Merlini'', or ''The Life of Merlin'', is a Latin poem in 1,529 hexameter lines written around the year 1150. Though doubts have in the past been raised about its authorship it is now widely believed to be by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It tel ...

'', written c. 1150) is ''Morgen'', which is likely derived from Old Welsh

Old Welsh ( cy, Hen Gymraeg) is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic a ...

or Old Breton

Breton (, ; or in Morbihan) is a Southwestern Brittonic language of the Celtic language family spoken in Brittany, part of modern-day France. It is the only Celtic language still widely in use on the European mainland, albeit as a member of th ...

''Morgen'', meaning 'sea-born' (from Common Brittonic

Common Brittonic ( cy, Brythoneg; kw, Brythonek; br, Predeneg), also known as British, Common Brythonic, or Proto-Brittonic, was a Celtic language spoken in Britain and Brittany.

It is a form of Insular Celtic, descended from Proto-Celtic, ...

''*Mori-genā'', the masculine form of which, ''*Mori-genos'', survived in Middle Welsh

Middle Welsh ( cy, Cymraeg Canol, wlm, Kymraec) is the label attached to the Welsh language of the 12th to 15th centuries, of which much more remains than for any earlier period. This form of Welsh developed directly from Old Welsh ( cy, Hen ...

as ''Moryen'' or ''Morien''; a cognate form in Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writte ...

is '' Muirgen'', the name of a Celtic Christian shapeshifting female saint who was associated with the sea). The name is not to be confused with the unrelated Modern Welsh

The history of the Welsh language (Welsh: ''Hanes yr iaith Gymraeg'') spans over 1400 years, encompassing the stages of the language known as Primitive Welsh, Old Welsh, Middle Welsh, and Modern Welsh.

Origins

Welsh evolved from British, the ...

masculine name Morgan Morgan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Morgan (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Morgan le Fay, a powerful witch in Arthurian legend

* Morgan (surname), a surname of Welsh origin

* Morgan (singer), ...

(spelled ''Morcant'' in the Old Welsh period). As her epithet "le Fay" (invented in the 15th century by Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of '' Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of '' Le Morte d' ...

from the earlier French ''la fée'' 'the fairy

A fairy (also fay, fae, fey, fair folk, or faerie) is a type of mythical being or legendary creature found in the folklore of multiple European cultures (including Celtic, Slavic, Germanic, English, and French folklore), a form of spiri ...

'; Malory would also use the form "le Fey" alternatively with "le Fay") and some traits indicate, the figure of Morgan appears to have been a remnant of supernatural

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin (above, beyond, or outside of) + (nature) Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings si ...

females from Celtic mythology

Celtic mythology is the body of myths belonging to the Celtic peoples.Cunliffe, Barry, (1997) ''The Ancient Celts''. Oxford, Oxford University Press , pp. 183 (religion), 202, 204–8. Like other Iron Age Europeans, Celtic peoples followed ...

, and her main name could be connected to the myths of Morgens Morgens, morgans, or mari-morgans are Welsh and Breton water spirits that drown men.

Etymology

The name may derive from Mori-genos or Mori-gena, meaning "sea-born. The name has also been rendered as Muri-gena or Murigen.

The name may also be cog ...

(also known as Mari-Morgans or just Morgans), the Welsh and Breton fairy water spirits

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a s ...

related to the legend of Princess Dahut (Ahes). While many later works make Morgan specifically human, she retains her magical powers, and sometimes, also her otherworld

The concept of an otherworld in historical Indo-European religion is reconstructed in comparative mythology. Its name is a calque of ''orbis alius'' (Latin for "other Earth/world"), a term used by Lucan in his description of the Celtic Otherwor ...

ly if not divine attributes. In fact, she is often referred to as either a Fairy Queen

In folklore and literature, the Fairy Queen or Queen of the Fairies is a female ruler of the fairies, sometimes but not always paired with a king. Depending on the work, she may be named or unnamed; Titania and Mab are two frequently used name ...

or outright a goddess

A goddess is a female deity. In many known cultures, goddesses are often linked with literal or metaphorical pregnancy or imagined feminine roles associated with how women and girls are perceived or expected to behave. This includes themes of s ...

(''dea'', ''déesse'', ''gotinne'') by authors.

Geoffrey's description of Morgen and her sisters in the ''Vita Merlini'' closely resembles the story of the nine Gaulish

Gaulish was an ancient Celtic language spoken in parts of Continental Europe before and during the period of the Roman Empire. In the narrow sense, Gaulish was the language of the Celts of Gaul (now France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switzerl ...

priestesses of the isle of Sena (now Île de Sein

The Île de Sein is a Brittany, Breton island in the Atlantic Ocean, off Finistère, eight kilometres from the Pointe du Raz (''raz'' meaning "water current"), from which it is separated by the Raz de Sein. Its Breton language, Breton name is ...

) called ''Gallisenae'' (or ''Gallizenae''), as described by the geographer Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela, who wrote around AD 43, was the earliest Roman geographer. He was born in Tingentera (now Algeciras) and died AD 45.

His short work (''De situ orbis libri III.'') remained in use nearly to the year 1500. It occupies less ...

during the first century, strongly suggesting that Pomponius' ''Description of the World'' (''De situ orbis'') was one of Geoffrey's prime sources. Further inspiration for her character likely came from Welsh folklore Welsh folklore is the collective term for the folklore of the Welsh people. It encompasses topics related to Welsh mythology, but also include the nation's folk tales, customs, and oral tradition.

Welsh folklore is related to Irish folklore and Sc ...

and medieval Irish literature and hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies migh ...

. Speculatively, beginning with Lucy Allen Paton in 1904, Morgan has been connected with the Irish shapeshifting and multifaced goddess of strife known as the Morrígan

The Morrígan or Mórrígan, also known as Morrígu, is a figure from Irish mythology. The name is Mór-Ríoghain in Modern Irish, and it has been translated as "great queen" or "phantom queen".

The Morrígan is mainly associated with war and ...

('Great Queen'). Proponents of this have included Roger Sherman Loomis

Roger Sherman Loomis (1887–1966) was an American scholar and one of the foremost authorities on medieval and Arthurian literature. Loomis is perhaps best known for showing the roots of Arthurian legend, in particular the Holy Grail, in native ...

, who doubted the Muirgen connection. Possible influence by elements of the classical Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of ...

sorceresses or goddesses such as Circe

Circe (; grc, , ) is an enchantress and a minor goddess in ancient Greek mythology and religion. She is either a daughter of the Titan Helios and the Oceanid nymph Perse or the goddess Hecate and Aeëtes. Circe was renowned for her vast kno ...

and especially Medea

In Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the ...

(who, similar to Morgan, are often alternately benevolent and malicious), and other magical women from the Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths native to the island of Ireland. It was originally passed down orally in the prehistoric era, being part of ancient Celtic religion. Many myths were later written down in the early medieval era by ...

such as the mother of hero Fráech

Fráech (Fróech, Fraích, Fraoch) is a Connacht hero (and half-divine as the son of goddess Bébinn) in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology. He is the nephew of Boann, goddess of the river Boyne, and son of Idath of the men of Connaught and ...

, as well as historical figure of Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

, have been also suggested. A chiefly Greek construction is a relatively new origin theory by Carolyne Larrington. One of the proposed candidates for the historical Arthur, Artuir mac Áedán, was recorded as having a sister named Maithgen (daughter of king Áedán mac Gabráin

Áedán mac Gabráin (pronounced in Old Irish; ga, Aodhán mac Gabhráin, lang), also written as Aedan, was a king of Dál Riata from 574 until c. 609 AD. The kingdom of Dál Riata was situated in modern Argyll and Bute, Scotland, and pa ...

, a 6th-century king of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaelic kingdom that encompassed the western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel. At its height in the 6th and 7th centuries, it covered what is ...

), whose name also appears as that of a prophetic druid

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. Wh ...

in the Irish legend of Saint Brigid of Kildare

Saint Brigid of Kildare or Brigid of Ireland ( ga, Naomh Bríd; la, Brigida; 525) is the patroness saint (or 'mother saint') of Ireland, and one of its three national saints along with Patrick and Columba. According to medieval Irish hagiogr ...

.

Morgan has also been often linked with the supernatural mother Modron

Modron ("mother") is a figure in Welsh tradition, known as the mother of the hero Mabon ap Modron. Both characters may have derived from earlier divine figures, in her case the Gaulish goddess Matrona. She may have been a prototype for Morgan le ...

,Charlotte Spivack, Roberta Lynne Staples. "Morgan le Fay: Goddess or Witch?". The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy

'' (Greenwood Press, 2000), pp. 32–45. derived from the continental

mother goddess

A mother goddess is a goddess who represents a personified deification of motherhood, fertility, creation, destruction, or the earth goddess who embodies the bounty of the earth or nature. When equated with the earth or the natural world, ...

figure of Dea Matrona

In Celtic mythology, Dea Matrona ("divine mother goddess") was the goddess who gives her name to the river Marne (ancient ''Matrŏna'') in Gaul.

The Gaulish theonym ''Mātr-on-ā'' signifies "great mother" and the goddess of the Marne has been i ...

and featured in medieval Welsh literature

Medieval Welsh literature is the literature written in the Welsh language during the Middle Ages. This includes material starting from the 5th century AD, when Welsh was in the process of becoming distinct from Common Brittonic, and continuing ...

. Modron appears in Welsh Triad 70 ("Three Blessed Womb-Burdens of the Island of Britain") – in which her children by Urien

Urien (; ), often referred to as Urien Rheged or Uriens, was a late 6th-century king of Rheged, an early British kingdom of the Hen Ogledd (today's northern England and southern Scotland) of the House of Rheged. His power and his victories, ...

are named Owain mab Urien

Owain mab Urien (Middle Welsh Owein) (died c. 595) was the son of Urien, king of Rheged c. 590, and fought with his father against the Angles of Bernicia. The historical figure of Owain became incorporated into the Arthurian cycle of legends ...

(son) and Morfydd (daughter) – and a later folktale have recorded more fully in the manuscript Peniarth 147. A fictionalised version of the historical king Urien is usually Morgan le Fay's husband in the variations of Arthurian legend informed by continental romances

Romance (from Vulgar Latin , "in the Roman language", i.e., "Latin") may refer to:

Common meanings

* Romance (love), emotional attraction towards another person and the courtship behaviors undertaken to express the feelings

* Romance languages, ...

, wherein their son is named Yvain

Sir Ywain , also known as Yvain and Owain among other spellings (''Ewaine'', ''Ivain'', ''Ivan'', ''Iwain'', ''Iwein'', ''Uwain'', ''Uwaine'', etc.), is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend, wherein he is often the son of King Uri ...

. Furthermore, the historical Urien had a treacherous ally named Morcant Bulc who plotted to assassinate him, much as Morgan attempts to kill Urien. Additionally, Modron is called "daughter of Afallach Afallach (Old Welsh Aballac) is a man's name found in several medieval Welsh genealogies, where he is made the son of Beli Mawr. According to a medieval Welsh triad, Afallach was the father of the goddess Modron. The Welsh redactions of Geoffrey ...

", a Welsh ancestor figure also known as Avallach or Avalloc, whose name can also be interpreted as a noun meaning 'a place of apples'; in the tale of Owain and Morfydd's conception in Peniarth 147, Modron is called the "daughter of the King of Annwn

Annwn, Annwfn, or Annwfyn (in Middle Welsh, ''Annwvn'', ''Annwyn'', ''Annwyfn'', ''Annwvyn'', or ''Annwfyn'') is the Otherworld in Welsh mythology. Ruled by Arawn (or, in Arthurian literature, by Gwyn ap Nudd), it was essentially a world ...

", a Celtic Otherworld

In Celtic mythology, the Otherworld is the realm of the deities and possibly also the dead. In Gaelic and Brittonic myth it is usually a supernatural realm of everlasting youth, beauty, health, abundance and joy.Koch, John T. ''Celtic Culture ...

. This evokes Avalon

Avalon (; la, Insula Avallonis; cy, Ynys Afallon, Ynys Afallach; kw, Enys Avalow; literally meaning "the isle of fruit r appletrees"; also written ''Avallon'' or ''Avilion'' among various other spellings) is a mythical island featured in th ...

, the marvelous "Isle of Apples" with which Morgan has been associated since her earliest appearances, and the Irish legend of the otherworldly woman Niamh including the motif of apple in connection to Avalon-like Otherworld isle of Tír na nÓg

In Irish mythology Tír na nÓg (; "Land of the Young") or Tír na hÓige ("Land of Youth") is one of the names for the Celtic Otherworld, or perhaps for a part of it. Tír na nÓg is best known from the tale of Oisín and Niamh.

Other Old Ir ...

("Land of Youth").

According to Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales ( la, Giraldus Cambrensis; cy, Gerallt Gymro; french: Gerald de Barri; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taugh ...

in '' De instructione principis'', a noblewoman and close relative of King Arthur named Morganis carried the dead Arthur to her island of Avalon (identified by him as Glastonbury

Glastonbury (, ) is a town and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated at a dry point on the low-lying Somerset Levels, south of Bristol. The town, which is in the Mendip district, had a population of 8,932 in the 2011 census. Glastonb ...

), where he was buried. Writing in the early 13th century in ''Speculum ecclesiae'', Gerald also claimed that "as a result, the fanciful Britons

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs m ...

and their bards invented the legend that some kind of a fantastic goddess (''dea quaedam phantastica'') had removed Arthur's body to the Isle of Avalon, so that she might cure his wounds there," for the purpose of enabling the possibility of King Arthur's messianic return

King Arthur's messianic return is a mythological motif in the legend of King Arthur, which claims that he will one day return in the role of a messiah to save his people. It is an example of the king asleep in mountain motif. King Arthur was ...

. In his encyclopaedic work, '' Otia Imperialia'', written around the same time and with similar derision for this belief, Gervase of Tilbury

Gervase of Tilbury ( la, Gervasius Tilberiensis; 1150–1220) was an English canon lawyer, statesman and cleric. He enjoyed the favour of Henry II of England and later of Henry's grandson, Emperor Otto IV, for whom he wrote his best known work, ...

calls that mythical enchantress Morganda Fatata (Morganda the Fairy). Morgan retains this role as Arthur's otherworldly healer in much of later tradition.

Medieval and Renaissance literature

Geoffrey, Chrétien and other early authors

Morgan first appears by name in ''

Morgan first appears by name in ''Vita Merlini

''Vita Merlini'', or ''The Life of Merlin'', is a Latin poem in 1,529 hexameter lines written around the year 1150. Though doubts have in the past been raised about its authorship it is now widely believed to be by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It tel ...

'', written by Norman-Welsh cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiograph ...

. Purportedly an account of the life of Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

, it elaborates some episodes from Geoffrey's more famous earlier work, ''Historia Regum Britanniae

''Historia regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), originally called ''De gestis Britonum'' (''On the Deeds of the Britons''), is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. ...

'' (1136). In ''Historia'', Geoffrey relates how King Arthur, gravely wounded by Mordred

Mordred or Modred (; Welsh: ''Medraut'' or ''Medrawt'') is a figure who is variously portrayed in the legend of King Arthur. The earliest known mention of a possibly historical Medraut is in the Welsh chronicle ''Annales Cambriae'', wherein h ...

at the Battle of Camlann

The Battle of Camlann ( cy, Gwaith Camlan or ''Brwydr Camlan'') is the legendary final battle of King Arthur, in which Arthur either died or was fatally wounded while fighting either with or against Mordred, who also perished. The original l ...

, is taken off to the blessed Isle of Apple Trees (Latin ''Insula Pomorum''), Avalon

Avalon (; la, Insula Avallonis; cy, Ynys Afallon, Ynys Afallach; kw, Enys Avalow; literally meaning "the isle of fruit r appletrees"; also written ''Avallon'' or ''Avilion'' among various other spellings) is a mythical island featured in th ...

, to be healed; Avalon (''Ynys Afallach'' in the Welsh versions of ''Historia'') is also mentioned as the place where Arthur's sword Excalibur

Excalibur () is the legendary sword of King Arthur, sometimes also attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. It was associated with the Arthurian legend very early on. Excalibur and the Sword in t ...

was forged. (Geoffrey's Arthur does have a sister, whose name is Anna, but the possibility of her being a predecessor to Morgan is unknown.) In ''Vita Merlini'', Geoffrey describes this island in more detail and names ''Morgen'' as the chief of the nine magical queen sisters who dwell there, ruling in their own right. Morgen agrees to take Arthur, delivered to her by Taliesin

Taliesin ( , ; 6th century AD) was an early Brittonic poet of Sub-Roman Britain whose work has possibly survived in a Middle Welsh manuscript, the ''Book of Taliesin''. Taliesin was a renowned bard who is believed to have sung at the courts ...

to have him revived. She and her sisters are capable of shapeshifting

In mythology, folklore and speculative fiction, shape-shifting is the ability to physically transform oneself through an inherently superhuman ability, divine intervention, demonic manipulation, sorcery, spells or having inherited the ...

and flying, and (at least seemingly) use their powers only for good. Morgen is also said to be a learned mathematician and to have taught it and astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

to her fellow nymph

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ty ...

(''nymphae'') sisters, whose names are listed as Moronoe, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Tyronoe, Thiten and Thiton.

In the making of this arguably Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jews, Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Jose ...

-type character and her sisters, Geoffrey might have been influenced by the first-century Roman cartographer Pomponius Mela

Pomponius Mela, who wrote around AD 43, was the earliest Roman geographer. He was born in Tingentera (now Algeciras) and died AD 45.

His short work (''De situ orbis libri III.'') remained in use nearly to the year 1500. It occupies less ...

, who has described an oracle at the Île de Sein

The Île de Sein is a Brittany, Breton island in the Atlantic Ocean, off Finistère, eight kilometres from the Pointe du Raz (''raz'' meaning "water current"), from which it is separated by the Raz de Sein. Its Breton language, Breton name is ...

off the coast of Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period o ...

and its nine virgin priestesses believed by the continental Celtic Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They s ...

to have the power to cure disease and perform various other awesome magic, such as controlling the sea through incantations, foretelling the future, and changing themselves into any animal. According to a theory postulated by R. S. Loomis

Roger Sherman Loomis (1887–1966) was an American scholar and one of the foremost authorities on medieval and Arthurian literature. Loomis is perhaps best known for showing the roots of Arthurian legend, in particular the Holy Grail, in native Ce ...

, Geoffrey was not the original inventor of Morgan's character, which had already existed in Breton folklore in the hypothetical unrecorded oral stories that featured her as Arthur's fairy saviour, or even also his fairy godmother

In fairy tales, a fairy godmother () is a fairy with magical powers who acts as a mentor or parent to someone, in the role that an actual godparent was expected to play in many societies. In Perrault's ''Cinderella'', he concludes the tale with ...

(her earliest shared supernatural ability being able to traverse on or under water). Such stories being told by wandering storytellers (as credited by Gerald of Wales) would then influence various authors writing independently from each other, especially since ''Vita Merlini'' was a relatively little-known text. Geoffrey's description of Morgan is notably very similar to that in Benoît de Sainte-Maure

Benoît de Sainte-Maure (; died 1173) was a 12th-century French poet, most probably from Sainte-Maure-de-Touraine near Tours, France. The Plantagenets' administrative center was located in Chinon, west of Tours.

''Le Roman de Troie''

His 40 ...

's epic poem ''Roman de Troie

(''The Romance of Troy'') by Benoît de Sainte-Maure, probably written between 1155 and 1160,Roberto Antonelli "The Birth of Criseyde - An Exemplary Triangle: 'Classical' Troilus and the Question of Love at the Anglo-Norman Court" in Boitani, P. ...

'' (c. 1155–1160), a story of the ancient Trojan War

In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. The war is one of the most important events in Greek mythology and ha ...

in which Morgan herself makes an unexplained appearance in this second known text featuring her. As Orvan the Fairy (''Orva la fée'', likely a corruption of a spelling such as ''*Morgua'' in the original-text),Schöning, Udo, ''Thebenroman - Eneasroman - Trojaroman: Studien zur Rezeption der Antike in der französischen Literatur des 12. Jahrhunderts'', Walter de Gruyter, 1991, p. 209. there she first lustfully loves the Trojan hero Hector

In Greek mythology, Hector (; grc, Ἕκτωρ, Hektōr, label=none, ) is a character in Homer's Iliad. He was a Trojan prince and the greatest warrior for Troy during the Trojan War. Hector led the Trojans and their allies in the defense o ...

and gifts him a wonderful horse, but then pursues him with hate after he rejects her. The abrupt way in which she is used suggests Benoît did expect his aristocratic audience to have been already familiar with her character. Of note, another such ancient-times appearance can be found in the much later ''Perceforest

''Perceforest'' or ''Le Roman de Perceforest'' is an anonymous prose chivalric romance, written in French around 1340, with lyrical interludes of poetry, that describes a fictional origin of Great Britain and provides an original genesis of the Art ...

'' (1330s), within the fourth book which is set in Britain during Julius Caesar's invasions, where the fairy Morgane lives in the isle of Zeeland and has learned her magic from Zephir. Here, she has a daughter named Morganette and an adoptive son named Passelion, who in turn have a son named Morgan, described as an ancestor of the Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake (french: Dame du Lac, Demoiselle du Lac, cy, Arglwyddes y Llyn, kw, Arloedhes an Lynn, br, Itron al Lenn, it, Dama del Lago) is a name or a title used by several either fairy or fairy-like but human enchantresses in the ...

.

In '' Jaufre'', an early

In '' Jaufre'', an early Occitan language

Occitan (; oc, occitan, link=no ), also known as ''lenga d'òc'' (; french: langue d'oc) by its native speakers, and sometimes also referred to as ''Provençal'', is a Romance language spoken in Southern France, Monaco, Italy's Occitan Valle ...

Arthurian romance dated c. 1180, Morgan seems to appear, without being named other than introducing herself as the "Fairy of Gibel", Gibel is the Arabic name of Mount Etna

Mount Etna, or simply Etna ( it, Etna or ; scn, Muncibbeḍḍu or ; la, Aetna; grc, Αἴτνα and ), is an active stratovolcano on the east coast of Sicily, Italy, in the Metropolitan City of Catania, between the cities of Messina a ...

in Sicily (''fada de Gibel'', the mount Gibel being a version of the Avalon motif as in later works), as the ruler of an underground kingdom who takes the protagonist knight Jaufre ( Griflet) through a fountain to gift him her magic ring

A magic ring is a mythical, folkloric or fictional piece of jewelry, usually a finger ring, that is purported to have supernatural properties or powers. It appears frequently in fantasy and fairy tales. Magic rings are found in the folklore of ...

of protection. In the romance poem ''Lanzelet

''Lanzelet'' is a medieval romance written by Ulrich von Zatzikhoven after 1194. It is the first treatment of the Lancelot tradition in German, and contains the earliest known account of the hero's childhood with the Lady of the Lake-like figu ...

'', written by the end of the 12th century by Ulrich von Zatzikhoven, the infant Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), also written as Launcelot and other variants (such as early German ''Lanzelet'', early French ''Lanselos'', early Welsh ''Lanslod Lak'', Italian ''Lancillotto'', Spanish ''Lanzarote del Lago' ...

is spirited away by a water fairy (''merfeine'' in Old High German

Old High German (OHG; german: Althochdeutsch (Ahd.)) is the earliest stage of the German language, conventionally covering the period from around 750 to 1050.

There is no standardised or supra-regional form of German at this period, and Old High ...

) and raised in her paradise island country of Meidelant (' Land of Maidens'). Ulrich's unnamed fairy queen

In folklore and literature, the Fairy Queen or Queen of the Fairies is a female ruler of the fairies, sometimes but not always paired with a king. Depending on the work, she may be named or unnamed; Titania and Mab are two frequently used name ...

character might be also related to Geoffrey's Morgen, as well as to the early Breton oral tradition of Morgan's figure, especially as her son there is named Mabuz, similar to the name of Modron's son Mabon ap Modron

Mabon ap Modron is a prominent figure from Welsh literature and mythology, the son of Modron and a member of Arthur's war band. Both he and his mother were likely deities in origin, descending from a divine mother–son pair. He is often equat ...

. In Layamon

Layamon or Laghamon (, ; ) – spelled Laȝamon or Laȝamonn in his time, occasionally written Lawman – was an English poet of the late 12th/early 13th century and author of the ''Brut'', a notable work that was the first to present the legend ...

's Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English ...

poem ''The Chronicle of Britain'' (c. 1215), Arthur was taken to Avalon by two women to be healed there by its most beautiful elfen () queen named Argante or Argane; it is possible her name had been originally ''Margan(te)'' before it was changed in manuscript transmission.

The 12th-century French poet

The 12th-century French poet Chrétien de Troyes

Chrétien de Troyes (Modern ; fro, Crestien de Troies ; 1160–1191) was a French poet and trouvère known for his writing on Arthurian subjects, and for first writing of Lancelot, Percival and the Holy Grail. Chrétien's works, including ...

already mentions her in his first romance, ''Erec and Enide

, original_title_lang = fro

, translator =

, written = c. 1170

, country =

, language = Old French

, subject = Arthurian legend

, genre = Chivalric romance

, form ...

'', completed around 1170. In it, a love of Morgan (Morgue) is Guigomar (Guingomar, Guinguemar), the Lord of the Isle of Avalon and a nephew of King Arthur, a character derivative of Guigemar "Guigemar" is a Breton lai, a type of narrative poem, written by Marie de France during the 12th century. The poem belongs to the collection known as ''The Lais of Marie de France''. Like the other lais in the collection, ''Guigemar'' is written in ...

from the Breton lai

A Breton lai, also known as a narrative lay or simply a lay, is a form of medieval French and English romance literature. Lais are short (typically 600–1000 lines), rhymed tales of love and chivalry, often involving supernatural and fairy-worl ...

''Guigemar "Guigemar" is a Breton lai, a type of narrative poem, written by Marie de France during the 12th century. The poem belongs to the collection known as ''The Lais of Marie de France''. Like the other lais in the collection, ''Guigemar'' is written in ...

''.Pérez, ''The Myth of Morgan la Fey'', p. 95. Guingamor's own lai by Marie de France

Marie de France (fl. 1160 to 1215) was a poet, possibly born in what is now France, who lived in England during the late 12th century. She lived and wrote at an unknown court, but she and her work were almost certainly known at the royal court o ...

links him to the beautiful magical entity known only as the "fairy mistress", who was later identified by Thomas Chestre's ''Sir Launfal

''Sir Launfal'' is a 1045-line Middle English romance or Breton lay written by Thomas Chestre dating from the late 14th century. It is based primarily on the 538-line Middle English poem ''Sir Landevale'', which in turn was based on Marie de Fran ...

'' as ''Dame Tryamour'', the daughter of the King of the Celtic Otherworld

In Celtic mythology, the Otherworld is the realm of the deities and possibly also the dead. In Gaelic and Brittonic myth it is usually a supernatural realm of everlasting youth, beauty, health, abundance and joy.Koch, John T. ''Celtic Culture ...

who shares many characteristics with Chrétien's Morgan. It was noted that even Chrétien' earliest mention of Morgan already shows an enmity between her and Queen Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; cy, Gwenhwyfar ; br, Gwenivar, kw, Gwynnever), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First me ...

, and although Morgan is represented only in a benign role by Chrétien, she resides in a mysterious place known as the Vale Perilous (which some later authors would say she has created as a place of punishment for unfaithful knights). She is later mentioned in the same poem when Arthur provides the wounded hero Erec

The Knights of the Round Table ( cy, Marchogion y Ford Gron, kw, Marghekyon an Moos Krenn, br, Marc'hegien an Daol Grenn) are the knights of the fellowship of King Arthur in the literary cycle of the Matter of Britain. First appearing in li ...

with a healing balm made by his sister Morgan. This episode affirms her early role as a healer, in addition to being one of the first instances of Morgan presented as Arthur's sister; healing is Morgan's chief ability, but Chrétien also hints at her potential to harm.

Chrétien again refers to Morgan as a great healer in his later romance ''Yvain, the Knight of the Lion

, original_title_lang = fro

, translator =

, written = between 1178 and 1181

, country =

, language = Old French

, subject = Arthurian legend

, genre = Chivalric romance

, fo ...

'', in an episode in which the Lady of Norison restores the maddened hero Yvain

Sir Ywain , also known as Yvain and Owain among other spellings (''Ewaine'', ''Ivain'', ''Ivan'', ''Iwain'', ''Iwein'', ''Uwain'', ''Uwaine'', etc.), is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend, wherein he is often the son of King Uri ...

to his senses with a magical potion provided by Morgan the Wise (''Morgue la sage''). Morgan the Wise is female in Chrétien's original, as well as in the Norse version '' Ivens saga'', but male in the English '' Ywain and Gawain''. While the fairy Modron is mother of Owain mab Urien

Owain mab Urien (Middle Welsh Owein) (died c. 595) was the son of Urien, king of Rheged c. 590, and fought with his father against the Angles of Bernicia. The historical figure of Owain became incorporated into the Arthurian cycle of legends ...

in the Welsh myth, and Morgan would be assigned this role in the later literature, this first continental association between Yvain (the romances' version of Owain) and Morgan does not imply they are son and mother. The earliest mention of Morgan as Yvain's mother is found in ''Tyolet ''Tyolet'' is an anonymous Breton lai that takes place in the realm of King Arthur. It tells the tale of a naïve young knight who wins the hand of a maiden after a magical adventure.

Composition and manuscripts

The actual date of composition is ...

'', an early 13th-century Breton lai.

The

The Middle Welsh

Middle Welsh ( cy, Cymraeg Canol, wlm, Kymraec) is the label attached to the Welsh language of the 12th to 15th centuries, of which much more remains than for any earlier period. This form of Welsh developed directly from Old Welsh ( cy, Hen ...

Arthurian tale ''Geraint son of Erbin

''Geraint son of Erbin'' (Middle Welsh ''Geraint uab Erbin'') is a medieval Welsh poem celebrating the hero Geraint and his deeds at the Battle of Llongborth. The poem consists of three-line ''englyn'' stanzas and exists in several versions all in ...

'', either based on Chrétien's ''Erec and Enide'' or derived from a common source, mentions King Arthur's chief physician named Morgan Tud. It is believed that this character, though considered a male in ''Gereint'', may be derived from Morgan le Fay, though this has been a matter of debate among Arthurian scholars since the 19th century (the epithet Tud may be a Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

or Breton cognate or borrowing of Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic ( sga, Goídelc, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ga, Sean-Ghaeilge; gd, Seann-Ghàidhlig; gv, Shenn Yernish or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive writte ...

''tuath'', 'north, left', 'sinister, wicked', also 'fairy (fay), elf'). There, Morgan is called to treat Edern ap Nudd

Edern ap Nudd ( la, Hiderus; Old french: Yder or ') was a knight of the Round Table in Arthur's court in early Arthurian tradition. As the son of Nudd (the ''Nu'', ''Nut'' or ''Nuc'' of Old French, Arthurian romance

), he is the brother of G ...

, Knight of the Sparrowhawk, following the latter's defeat at the hands of his adversary Geraint

Geraint () is a character from Welsh folklore and Arthurian legend, a valiant warrior possibly related to the historical Geraint, an early 8th-century king of Dumnonia. It is also the name of a 6th-century Dumnonian saint king from Briton h ...

, and is later called on by Arthur to treat Geraint himself. In the German version of ''Erec'', the 12th-century knight and poet Hartmann von Aue

Hartmann von Aue, also known as Hartmann von Ouwe, (born ''c.'' 1160–70, died ''c.'' 1210–20) was a German knight and poet. With his works including '' Erec'', '' Iwein'', '' Gregorius'', and '' Der arme Heinrich'', he introduced the Arthur ...

has Erec healed by Guinevere with a special plaster that was given to Arthur by the king's sister, the goddess (''gotinne'') Feimurgân (''Fâmurgân'', Fairy Murgan):

In writing that, Hartmann might have not been influenced by Chrétien, but rather by an earlier oral tradition from the stories of Breton bards. Hartmann also separated Arthur's sister (that is Feimurgân) from the fairy mistress of the lord of Avalon (Chrétien's Guigomar), who in his version is named Marguel. In the anonymous First Continuation of Chrétien's ''Perceval, the Story of the Grail

''Perceval, the Story of the Grail'' (french: Perceval ou le Conte du Graal) is the unfinished fifth verse romance by Chrétien de Troyes, written by him in Old French in the late 12th century. Later authors added 54,000 more lines in what are kn ...

'', the fairy lover of its variant of Guigomar (here as Guingamuer) is named Brangepart, and the two have a son Brangemuer who became the king of an otherworldly isle "where no mortal lived". In the 13th-century romance ''Parzival

''Parzival'' is a medieval romance by the knight-poet Wolfram von Eschenbach in Middle High German. The poem, commonly dated to the first quarter of the 13th century, centers on the Arthurian hero Parzival (Percival in English) and his long qu ...

'', another German knight-poet Wolfram von Eschenbach

Wolfram von Eschenbach (; – ) was a German knight, poet and composer, regarded as one of the greatest epic poets of medieval German literature. As a Minnesinger, he also wrote lyric poetry.

Life

Little is known of Wolfram's life. There ...

inverted Hartmann's Fâmurgân's name to create that of Arthur's fairy ancestor named Terdelaschoye de Feimurgân, the wife of Mazadân, where the part "Terdelaschoye" comes from ''Terre de la Joie'', or Land of Joy; the text also mentions the mountain of Fâmorgân. Jean Markale Jean Markale (May 23, 1928 in Paris – November 23, 2008) was the pen name of Jean Bertrand, a French writer, poet, radio show host, lecturer and high school French teacher who lived in Brittany. As a former specialist in Celtic studies at the So ...

further identified a Morganian figure in Wolfram's ambiguous character of Cundrie the Sorceress (later

Later may refer to:

* Future, the time after the present

Television

* ''Later'' (talk show), a 1988–2001 American talk show

* '' Later... with Jools Holland'', a British music programme since 1992

* '' The Life and Times of Eddie Roberts'', or ...

better known as Kundry) through her plot function as mistress of illusions in an enchanted fairy garden.

Speculatively, Loomis and John Matthews further identified other perceived avatars of Morgan as the "Besieged Lady" archetype in various early works associated with the Castle of Maidens motif, often appearing as (usually unnamed) wife of King Lot

King Lot , also spelled Loth or Lott (Lleu or Llew in Welsh), is a British monarch in Arthurian legend. He was introduced in Geoffrey of Monmouth's influential chronicle '' Historia Regum Britanniae'' that portrayed him as King Arthur's brot ...

and mother of Gawain

Gawain (), also known in many other forms and spellings, is a character in Arthurian legend, in which he is King Arthur's nephew and a Knight of the Round Table. The prototype of Gawain is mentioned under the name Gwalchmei in the earlies ...

. These characters include the Queen of Meidenlant in ''Diu Crône

''Diu Crône'' ( en, The Crown) is a Middle High German poem of about 30,000 lines treating of King Arthur and the Matter of Britain, dating from around the 1220s and attributed to the epic poet Heinrich von dem Türlin. Little is known of the ...

'', the lady of Castellum Puellarum in '' De Ortu Waluuanii'', and the nameless heroine of the Breton lai '' Doon'', among others, including some in later works (such as with Lady Lufamore of Maydenlande in '' Sir Perceval of Galles''). Loomis also linked her to the eponymous seductress evil queen from ''The Queen of Scotland

The Queen of Scotland (Child ballad 301, Roud number 3878) is a folk song.

Synopsis

The Queen of Scotland tries to lure Troy Muir to her bed. When she fails, she directs him to lift a stone in her garden, and a hungry snake emerges. A woman c ...

'', a 19th-century ballad "containing Arthurian material dating back to the year 1200."

A recently discovered moralistic manuscript written in Anglo-Norman French

Anglo-Norman, also known as Anglo-Norman French ( nrf, Anglo-Normaund) (French: ), was a dialect of Old Norman French that was used in England and, to a lesser extent, elsewhere in Great Britain and Ireland during the Anglo-Norman period.

When ...

is the only known instance of medieval Arthurian literature presented as being composed by Morgan herself. This late 12th-century text is purportedly addressed to her court official and tells of the story of a knight called Piers the Fierce; it is likely that the author's motive was to draw a satirical moral from the downfall of the English knight Piers Gaveston, 1st Earl of Cornwall

Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall (c. 1284 – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househ ...

. Morgayne is titled in it as "empress of the wilderness, queen of the damsels, lady of the isles, and governor of the waves of the great sea." Morgan (''Morganis'') is also mentioned in the ''Draco Normannicus The ''Draco Normannicus'' is a chronicle written circa 1167-1169 by Étienne de Rouen (Stephen of Rouen), a Norman Benedictine monk from Bec-Hellouin. Considered Étienne's principal work, it survives in the Vatican Library. The manuscript was ini ...

'', a 12th-century (c. 1167–1169) Latin chronicle by Étienne de Rouen Étienne de Rouen (died ), also Stephen of Rouen and la, Stephanus de Rouen, italic=no, was a Norman Benedictine monk of Bec Abbey of the twelfth century, and a chronicler and poet.

The dukes of Normandy commissioned and inspired epic literature ...

, which contains a fictitious letter addressed by King Arthur to Henry II of England

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin king ...

, written for political propaganda purpose of having 'Arthur' criticise King Henry for invading the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany ( br, Dugelezh Breizh, ; french: Duché de Bretagne) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of Europe, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean t ...

. Notably, it is one of the first known texts that made her a sister to Arthur, as she is in the works of Chrétien and many others after him. As described by Étienne,

French prose cycles

Morgan's role was greatly expanded by the unknown authors of the early-13th-century

Morgan's role was greatly expanded by the unknown authors of the early-13th-century Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligi ...

romances of the Vulgate Cycle

The ''Lancelot-Grail'', also known as the Vulgate Cycle or the Pseudo-Map Cycle, is an early 13th-century French Arthurian literary cycle consisting of interconnected prose episodes of chivalric romance in Old French. The cycle of unknown authors ...

(also known as the Lancelot-Grail

The ''Lancelot-Grail'', also known as the Vulgate Cycle or the Pseudo-Map Cycle, is an early 13th-century French Arthurian literary cycle consisting of interconnected prose episodes of chivalric romance in Old French. The cycle of unknown aut ...

cycle) and especially its subsequent rewrite, the Prose ''Tristan''-influenced Post-Vulgate Cycle

The ''Post-Vulgate Cycle'', also known as the Post-Vulgate Arthuriad, the Post-Vulgate ''Roman du Graal'' (''Romance of the Grail'') or the Pseudo-Robert de Boron Cycle, is one of the major Old French prose cycles of Arthurian literature from the ...

. These works are believed to be at least influenced by the Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Sain ...

religious order, which might explain the texts' demonisation of pagan motifs and increasingly anti-sex attitude. Integrating her fully into the Arthurian world, they also portray Morgan's ways and deeds as being much more sinister and aggressive than they are in Geoffrey or Chrétien, showing her undergoing a series of transformations in the process of becoming a chaotic counter-heroine. Beginning as an erratic ally of Arthur and a notorious temptress opposed to his wife and some of his knights (especially Lancelot) in the original stories of the Vulgate Cycle, Morgan's figure eventually often turns into an ambitious and depraved nemesis of King Arthur himself in the Post-Vulgate. Her common image is now a malicious and cruel sorceress, the source of many intrigues at the royal court of Arthur and elsewhere. In some of the later works, she is also subversively working to take over Arthur's throne through her mostly harmful magic and scheming, including manipulating men. Most of the time, Morgan's magic arts correspond with these of Merlin's and the Lady of the Lake's, featuring shapeshifting, illusion, and sleeping spells (Richard Kieckhefer

Richard Kieckhefer (born 1946) is an American medievalist, religious historian, scholar of church architecture, and author. He is Professor of History and John Evans Professor of Religious Studies at Northwestern University.

Education

After an ...

connected it with Norse magic). Although she is usually depicted in medieval romances as beautiful and seductive, the medieval archetype of the loathly lady

The loathly lady ( cy, dynes gas, Motif D732 in Stith Thompson's motif index), is a tale type commonly used in medieval literature, most famously in Geoffrey Chaucer's '' The Wife of Bath's Tale''. The motif is that of a woman who appears una ...

is used frequently, as Morgan can be in a contradictory fashion described as both beautiful and ugly even within the same narration.

Family and upbringing

This version of Morgan (usually named ''Morgane'' or ''Morgain'') first appears in the few surviving verses of the Old French poem ''Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

'', which later served as the original source for the Vulgate Cycle and consequently also the Post-Vulgate Cycle. It was written c. 1200 by the French knight-poet Robert de Boron

Robert de Boron (also spelled in the manuscripts "Roberz", "Borron", "Bouron", "Beron") was a French poet of the late 12th and early 13th centuries, notable as the reputed author of the poems and ''Merlin''. Although little is known of him apart ...

, who described her as an illegitimate daughter of Lady Igraine

In the Matter of Britain, Igraine () is the mother of King Arthur. Igraine is also known in Latin as Igerna, in Welsh as Eigr ( Middle Welsh Eigyr), in French as Ygraine (Old French Ygerne or Igerne), in '' Le Morte d'Arthur'' as Ygrayne—of ...

with an initially unnamed Duke of Tintagel

Tintagel () or Trevena ( kw, Tre war Venydh, meaning ''Village on a Mountain'') is a civil parish and village situated on the Atlantic coast of Cornwall, England. The village and nearby Tintagel Castle are associated with the legends surroundi ...

, after whose death she is adopted by King Neutres of Garlot.Larrington, ''King Arthur's Enchantresses'', p. 41. ''Merlin'' is the first known work linking Morgan to Igraine and mentioning her learning sorcery after having been sent away for an education. The reader is informed that Morgan was given her moniker 'la fée' (the fairy) due to her great knowledge. A 14th-century massive prequel to the Arthurian legend, ''Perceforest'', also implies that Arthur's sister was later named after its ''fée'' character Morgane from several centuries earlier.

In a popular tradition from later evolution of this narrative, Morgan is the youngest of the daughters of Igraine and

In a popular tradition from later evolution of this narrative, Morgan is the youngest of the daughters of Igraine and Gorlois

In Arthurian legend, Gorlois ( cy, Gwrlais) of Tintagel, Duke of Cornwall, is the first husband of Igraine, whose second husband is Uther Pendragon. Gorlois's name first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' (). A vas ...

, the Duke of Cornwall

Duke of Cornwall is a title in the Peerage of England, traditionally held by the eldest son of the reigning British monarch, previously the English monarch. The duchy of Cornwall was the first duchy created in England and was established by a ...

. In the poem's prose version and its continuations, she has at least two elder sisters (various manuscripts list up to five daughters and some do not mention Morgan being a bastard child): Elaine of Garlot and the Queen of Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) nort ...

sometimes known as Morgause

The Queen of Orkney, today best known as Morgause and also known as Morgawse and other spellings and names, is a character in later Arthurian traditions. In some versions of the legend, including the seminal text ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', she is ...

, the latter of whom is the mother of Arthur's knights Gawain, Agravain

Sir Agravain () is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend, whose first known appearance is in the works of Chrétien de Troyes. He is the second eldest son of King Lot of Orkney with one of King Arthur's sisters known as Anna or Morg ...

, Gaheris

Gaheris (Old French: ''Gaheriet'', ''Gaheriés'', ''Guerrehes'') is a knight of the Round Table in the chivalric romance tradition of Arthurian legend. A nephew of King Arthur, Gaheris is the third son of Arthur's sister or half-sister Morgaus ...

and Gareth

Sir Gareth (; Old French: ''Guerehet'', ''Guerrehet'') is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend. He is the youngest son of King Lot and Queen Morgause, King Arthur's half-sister, thus making him Arthur's nephew, as well as brother ...

by King Lot, and the traitor Mordred by Arthur (in some romances the wife of King Lot is called Morcades, a name that R. S. Loomis argued was another name of Morgan). At a young age, Morgan is sent to a convent

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglic ...

after Arthur's father Uther Pendragon

Uther Pendragon ( Brittonic) (; cy, Ythyr Ben Dragwn, Uthyr Pendragon, Uthyr Bendragon), also known as King Uther, was a legendary King of the Britons in sub-Roman Britain (c. 6th century). Uther was also the father of King Arthur.

A few ...

, aided by the half-demon Merlin, kills Gorlois and rapes and marries her mother, who later gives him a son, Arthur (which makes him Morgan's younger half-brother). There, Morgan masters the seven arts