Modulating subject on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

In

A tonal answer is usually called for when the subject begins with a prominent dominant note, or where there is a prominent dominant note very close to the beginning of the subject. To prevent an undermining of the music's sense of key, this note is transposed up a fourth to the tonic rather than up a fifth to the

A tonal answer is usually called for when the subject begins with a prominent dominant note, or where there is a prominent dominant note very close to the beginning of the subject. To prevent an undermining of the music's sense of key, this note is transposed up a fourth to the tonic rather than up a fifth to the  The countersubject is written in invertible counterpoint at the octave or fifteenth. The distinction is made between the use of free counterpoint and regular countersubjects accompanying the fugue subject/answer, because in order for a countersubject to be heard accompanying the subject in more than one instance, it must be capable of sounding correctly above or below the subject, and must be conceived, therefore, in invertible (double) counterpoint.

In tonal music, invertible contrapuntal lines must be written according to certain rules because several intervallic combinations, while acceptable in one particular orientation, are no longer permissible when inverted. For example, when the note "G" sounds in one voice above the note "C" in lower voice, the interval of a fifth is formed, which is considered

The countersubject is written in invertible counterpoint at the octave or fifteenth. The distinction is made between the use of free counterpoint and regular countersubjects accompanying the fugue subject/answer, because in order for a countersubject to be heard accompanying the subject in more than one instance, it must be capable of sounding correctly above or below the subject, and must be conceived, therefore, in invertible (double) counterpoint.

In tonal music, invertible contrapuntal lines must be written according to certain rules because several intervallic combinations, while acceptable in one particular orientation, are no longer permissible when inverted. For example, when the note "G" sounds in one voice above the note "C" in lower voice, the interval of a fifth is formed, which is considered

Only one entry of the subject must be heard in its completion in a ''stretto''. However, a ''stretto'' in which the subject/answer is heard in completion in all voices is known as ''stretto maestrale'' or ''grand stretto''. ''Strettos'' may also occur by inversion, augmentation and diminution. A fugue in which the opening exposition takes place in ''stretto'' form is known as a ''close fugue'' or ''stretto fugue'' (see for example, the ''Gratias agimus tibi'' and ' choruses from J.S. Bach's

Only one entry of the subject must be heard in its completion in a ''stretto''. However, a ''stretto'' in which the subject/answer is heard in completion in all voices is known as ''stretto maestrale'' or ''grand stretto''. ''Strettos'' may also occur by inversion, augmentation and diminution. A fugue in which the opening exposition takes place in ''stretto'' form is known as a ''close fugue'' or ''stretto fugue'' (see for example, the ''Gratias agimus tibi'' and ' choruses from J.S. Bach's

In

In music

Music is generally defined as the The arts, art of arranging sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Exact definition of music, definitions of mu ...

, a fugue () is a contrapuntal

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tra ...

compositional technique

Musical composition can refer to an original piece or work of music, either vocal or instrumental, the structure of a musical piece or to the process of creating or writing a new piece of music. People who create new compositions are called c ...

in two or more voices, built on a subject (a musical theme) that is introduced at the beginning in imitation

Imitation (from Latin ''imitatio'', "a copying, imitation") is a behavior whereby an individual observes and replicates another's behavior. Imitation is also a form of that leads to the "development of traditions, and ultimately our culture. ...

(repetition at different pitches) and which recurs frequently in the course of the composition. It is not to be confused with a ''fuguing tune

The fuguing tune (often fuging tune) is a variety of Anglo-American vernacular choral music. It first flourished in the mid-18th century and continues to be composed today.

Description

Fuguing tunes are sacred music, specifically, Protestant hymn ...

'', which is a style of song popularized by and mostly limited to early American

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Early ...

(i.e. shape note

Shape notes are a musical notation designed to facilitate congregational and social singing. The notation, introduced in late 18th century England, became a popular teaching device in American singing schools. Shapes were added to the notehe ...

or "Sacred Harp

Sacred Harp singing is a tradition of sacred choral music that originated in New England and was later perpetuated and carried on in the American South. The name is derived from ''The Sacred Harp'', a ubiquitous and historically important tun ...

") music and West Gallery music

__NOTOC__

West gallery music, also known as Georgian psalmody, refers to the sacred music (metrical psalms, with a few hymns and anthems) sung and played in English parish churches, as well as nonconformist chapels, from 1700 to around 1850. In ...

. A fugue usually has three main sections: an exposition

Exposition (also the French for exhibition) may refer to:

*Universal exposition or World's Fair

*Expository writing

**Exposition (narrative)

*Exposition (music)

*Trade fair

* ''Exposition'' (album), the debut album by the band Wax on Radio

*Exposi ...

, a development and a final entry that contains the return of the subject in the fugue's tonic key. Some fugues have a recapitulation.

In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, the term was widely used to denote any works in canonic style; by the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

, it had come to denote specifically imitative works. Since the 17th century, the term ''fugue'' has described what is commonly regarded as the most fully developed procedure of imitative counterpoint.

Most fugues open with a short main theme, the subject, which then sounds successively in each voice

The human voice consists of sound made by a human being using the vocal tract, including talking, singing, laughing, crying, screaming, shouting, humming or yelling. The human voice frequency is specifically a part of human sound production ...

(after the first voice is finished stating the subject, a second voice repeats the subject at a different pitch, and other voices repeat in the same way); when each voice has completed the subject, the ''exposition'' is complete. This is often followed by a connecting passage, or ''episode'', developed from previously heard material; further "entries" of the subject then are heard in related keys. Episodes (if applicable) and entries are usually alternated until the "final entry" of the subject, by which point the music has returned to the opening key, or tonic, which is often followed by closing material, the coda

Coda or CODA may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* Movie coda, a post-credits scene

* ''Coda'' (1987 film), an Australian horror film about a serial killer, made for television

*''Coda'', a 2017 American experimental film from Na ...

."Fugue", ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music'', fourth edition, ed. Michael Kennedy (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

, 1996). In this sense, a fugue is a style of composition, rather than a fixed structure.

The form evolved during the 18th century from several earlier types of contrapuntal compositions, such as imitative ricercar

A ricercar ( , ) or ricercare ( , ) is a type of late Renaissance and mostly early Baroque instrumental composition. The term ''ricercar'' derives from the Italian verb which means 'to search out; to seek'; many ricercars serve a preludial funct ...

s, capriccios, canzonas, and fantasias. The famous fugue composer Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wo ...

(1685–1750) shaped his own works after those of Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck ( ; April or May, 1562 – 16 October 1621) was a Dutch composer, organist, and pedagogue whose work straddled the end of the Renaissance and beginning of the Baroque eras. He was among the first major keyboard compo ...

(1562-1621), Johann Jakob Froberger

Johann Jakob Froberger (baptized 19 May 1616 – 7 May 1667) was a German Baroque composer, keyboard virtuoso, and organist. Among the most famous composers of the era, he was influential in developing the musical form of the suite of dances in ...

(1616–1667), Johann Pachelbel

Johann Pachelbel (baptised – buried 9 March 1706; also Bachelbel) was a German composer, organist, and teacher who brought the south German organ schools to their peak. He composed a large body of sacred and secular music, and his contrib ...

(1653–1706), Girolamo Frescobaldi

Girolamo Alessandro Frescobaldi (; also Gerolamo, Girolimo, and Geronimo Alissandro; September 15831 March 1643) was an Italian composer and virtuoso keyboard player. Born in the Duchy of Ferrara, he was one of the most important composers of ...

(1583–1643), Dieterich Buxtehude

Dieterich Buxtehude (; ; born Diderik Hansen Buxtehude; c. 1637 – 9 May 1707) was a Danish organist and composer of the Baroque period, whose works are typical of the North German organ school. As a composer who worked in various vocal ...

(c. 1637–1707) and others. With the decline of sophisticated styles at the end of the baroque period

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

, the fugue's central role waned, eventually giving way as sonata form

Sonata form (also ''sonata-allegro form'' or ''first movement form'') is a musical structure generally consisting of three main sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation. It has been used widely since the middle of the 18th c ...

and the symphony orchestra

An orchestra (; ) is a large instrumental ensemble typical of classical music, which combines instruments from different families.

There are typically four main sections of instruments:

* bowed string instruments, such as the violin, viola, ...

rose to a dominant position. Nevertheless, composers continued to write and study fugues for various purposes; they appear in the works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

(1756–1791) and Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

(1770–1827), as well as modern composers such as Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975).

Etymology

The English term ''fugue'' originated in the 16th century and is derived from the French word ''fugue'' or the Italian ''fuga''. This in turn comes from Latin, also ''fuga'', which is itself related to both ''fugere'' ("to flee") and ''fugare'' ("to chase"). The adjectival form is ''fugal''. Variants include ''fughetta'' (literally, "a small fugue") and ''fugato'' (a passage in fugal style within another work that is not a fugue).Musical outline

A fugue begins with the ''exposition

Exposition (also the French for exhibition) may refer to:

*Universal exposition or World's Fair

*Expository writing

**Exposition (narrative)

*Exposition (music)

*Trade fair

* ''Exposition'' (album), the debut album by the band Wax on Radio

*Exposi ...

'' and is written according to certain predefined rules; in later portions the composer has more freedom, though a logical key structure is usually followed. Further entries of the subject will occur throughout the fugue, repeating the accompanying material at the same time. The various entries may or may not be separated by ''episodes''.

What follows is a chart displaying a fairly typical fugal outline, and an explanation of the processes involved in creating this structure.

::S = subject; A = answer; CS = countersubject; T = tonic; D = dominant

Exposition

A fugue begins with the exposition of its subject in one of the voices alone in the tonic key. G. M. Tucker and Andrew V. Jones, "Fugue", in ''The Oxford Companion to Music'', ed. Alison Latham (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002). After the statement of the subject, a second voice enters and states the subject with the subject transposed to another key (usually the dominant or subdominant), which is known as the ''answer''. To make the music run smoothly, it may also have to be altered slightly. When the answer is an exact copy of the subject to the new key, with identical intervals to the first statement, it is classified as a ''real answer''; if the intervals are altered to maintain the key it is a ''tonal answer''. A tonal answer is usually called for when the subject begins with a prominent dominant note, or where there is a prominent dominant note very close to the beginning of the subject. To prevent an undermining of the music's sense of key, this note is transposed up a fourth to the tonic rather than up a fifth to the

A tonal answer is usually called for when the subject begins with a prominent dominant note, or where there is a prominent dominant note very close to the beginning of the subject. To prevent an undermining of the music's sense of key, this note is transposed up a fourth to the tonic rather than up a fifth to the supertonic

In music, the supertonic is the second degree () of a diatonic scale, one whole step above the tonic. In the movable do solfège system, the supertonic note is sung as ''re''.

The triad built on the supertonic note is called the supertonic cho ...

. Answers in the subdominant are also employed for the same reason.

While the answer is being stated, the voice in which the subject was previously heard continues with new material. If this new material is reused in later statements of the subject, it is called a ''countersubject

In music, a subject is the material, usually a recognizable melody, upon which part or all of a composition is based. In forms other than the fugue, this may be known as the theme.

Characteristics

A subject may be perceivable as a complete mu ...

''; if this accompanying material is only heard once, it is simply referred to as ''free counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tra ...

''.

The countersubject is written in invertible counterpoint at the octave or fifteenth. The distinction is made between the use of free counterpoint and regular countersubjects accompanying the fugue subject/answer, because in order for a countersubject to be heard accompanying the subject in more than one instance, it must be capable of sounding correctly above or below the subject, and must be conceived, therefore, in invertible (double) counterpoint.

In tonal music, invertible contrapuntal lines must be written according to certain rules because several intervallic combinations, while acceptable in one particular orientation, are no longer permissible when inverted. For example, when the note "G" sounds in one voice above the note "C" in lower voice, the interval of a fifth is formed, which is considered

The countersubject is written in invertible counterpoint at the octave or fifteenth. The distinction is made between the use of free counterpoint and regular countersubjects accompanying the fugue subject/answer, because in order for a countersubject to be heard accompanying the subject in more than one instance, it must be capable of sounding correctly above or below the subject, and must be conceived, therefore, in invertible (double) counterpoint.

In tonal music, invertible contrapuntal lines must be written according to certain rules because several intervallic combinations, while acceptable in one particular orientation, are no longer permissible when inverted. For example, when the note "G" sounds in one voice above the note "C" in lower voice, the interval of a fifth is formed, which is considered consonant

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract. Examples are and pronounced with the lips; and pronounced with the front of the tongue; and pronounced ...

and entirely acceptable. When this interval is inverted ("C" in the upper voice above "G" in the lower), it forms a fourth, considered a dissonance in tonal contrapuntal practice, and requires special treatment, or preparation and resolution, if it is to be used. The countersubject, if sounding at the same time as the answer, is transposed to the pitch of the answer. Each voice then responds with its own subject or answer, and further countersubjects or free counterpoint may be heard.

When a tonal answer is used, it is customary for the exposition to alternate subjects (S) with answers (A), however, in some fugues this order is occasionally varied: e.g., see the SAAS arrangement of Fugue No. 1 in C Major, BWV 846, from J.S. Bach's '' Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1''. A brief codetta is often heard connecting the various statements of the subject and answer. This allows the music to run smoothly. The codetta, just as the other parts of the exposition, can be used throughout the rest of the fugue.

The first answer must occur as soon after the initial statement of the subject as possible; therefore the first codetta is often extremely short, or not needed. In the above example, this is the case: the subject finishes on the quarter note

A quarter note (American) or crotchet ( ) (British) is a musical note played for one quarter of the duration of a whole note (or semibreve). Quarter notes are notated with a filled-in oval note head and a straight, flagless stem. The stem ...

(or crotchet) B of the third beat of the second bar which harmonizes the opening G of the answer. The later codettas may be considerably longer, and often serve to (a) develop the material heard so far in the subject/answer and countersubject and possibly introduce ideas heard in the second countersubject or free counterpoint that follows (b) delay, and therefore heighten the impact of the reentry of the subject in another voice as well as modulating back to the tonic.

The exposition usually concludes when all voices have given a statement of the subject or answer. In some fugues, the exposition will end with a redundant entry, or an extra presentation of the theme. Furthermore, in some fugues the entry of one of the voices may be reserved until later, for example in the pedals of an organ fugue (see J.S. Bach's Fugue in C major for Organ, BWV 547).

Episode

Further entries of the subject follow this initial exposition, either immediately (as for example in Fugue No. 1 in C major, BWV 846 of the ''Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time, ''clavier'', meaning keyboard, referred to a variety of ins ...

'') or separated by episodes. Episodic material is always modulatory and is usually based upon some element heard in the exposition. Each episode has the primary function of transitioning for the next entry of the subject in a new key, and may also provide release from the strictness of form employed in the exposition, and middle-entries. André Gedalge states that the episode of the fugue is generally based on a series of imitations of the subject that have been fragmented.

Development

Further entries of the subject, or middle entries, occur throughout the fugue. They must state the subject or answer at least once in its entirety, and may also be heard in combination with the countersubject(s) from the exposition, new countersubjects, free counterpoint, or any of these in combination. It is uncommon for the subject to enter alone in a single voice in the middle entries as in the exposition; rather, it is usually heard with at least one of the countersubjects and/or other free contrapuntal accompaniments. Middle entries tend to occur at pitches other than the initial. As shown in the typical structure above, these are oftenclosely related key

In music, a closely related key (or close key) is one sharing many common tones with an original key, as opposed to a distantly related key (or distant key). In music harmony, there are six of them: five share all, or all except one, pitches w ...

s such as the relative dominant and subdominant, although the key structure of fugues varies greatly. In the fugues of J.S. Bach, the first middle entry occurs most often in the relative major

In music, relative keys are the major and minor scales that have the same key signatures ( enharmonically equivalent), meaning that they share all the same notes but are arranged in a different order of whole steps and half steps. A pair of maj ...

or minor of the work's overall key, and is followed by an entry in the dominant of the relative major or minor when the fugue's subject requires a tonal answer. In the fugues of earlier composers (notably, Buxtehude

Buxtehude (), officially the Hanseatic City of Buxtehude (german: Hansestadt Buxtehude, nds, Hansestadt Buxthu ()), is a town on the Este River in Northern Germany, belonging to the district of Stade in Lower Saxony. It is part of the Hamburg ...

and Pachelbel

Johann Pachelbel (baptised – buried 9 March 1706; also Bachelbel) was a German composer, organist, and teacher who brought the south German organ schools to their peak. He composed a large body of sacred and secular music, and his contri ...

), middle entries in keys other than the tonic and dominant tend to be the exception, and non-modulation the norm. One of the famous examples of such non-modulating fugue occurs in Buxtehude's Praeludium (Fugue and Chaconne) in C, BuxWV 137.

When there is no entrance of the subject and answer material, the composer can develop the subject by altering the subject. This is called an ''episode'', often by ''inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

'', although the term is sometimes used synonymously with middle entry and may also describe the exposition of completely new subjects, as in a double fugue for example (see below). In any of the entries within a fugue, the subject may be altered, by inversion, retrograde (a less common form where the entire subject is heard back-to-front) and diminution

In Western music and music theory, diminution (from Medieval Latin ''diminutio'', alteration of Latin ''deminutio'', decrease) has four distinct meanings. Diminution may be a form of embellishment in which a long note is divided into a series ...

(the reduction of the subject's rhythmic values by a certain factor), augmentation (the increase of the subject's rhythmic values by a certain factor) or any combination of them.

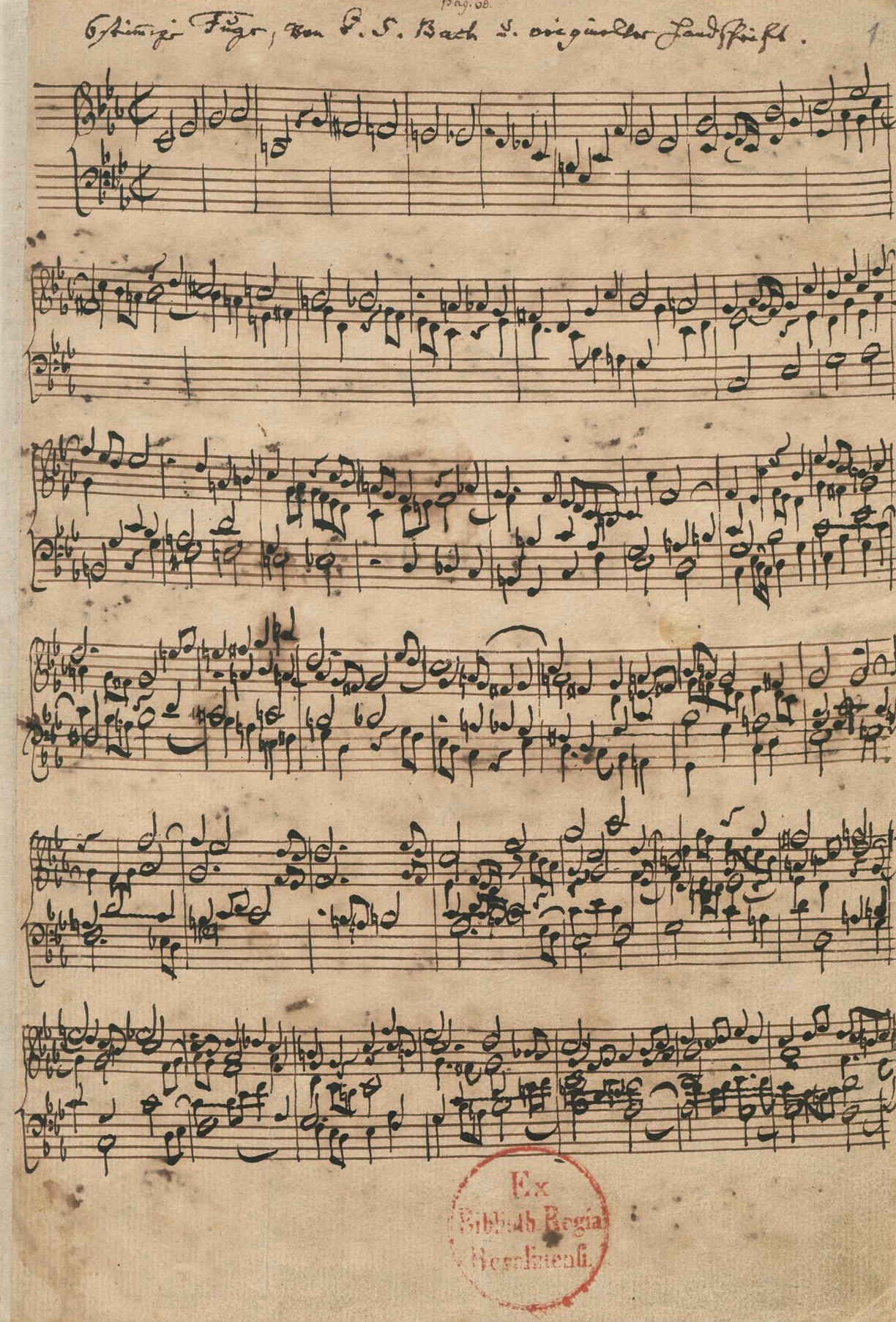

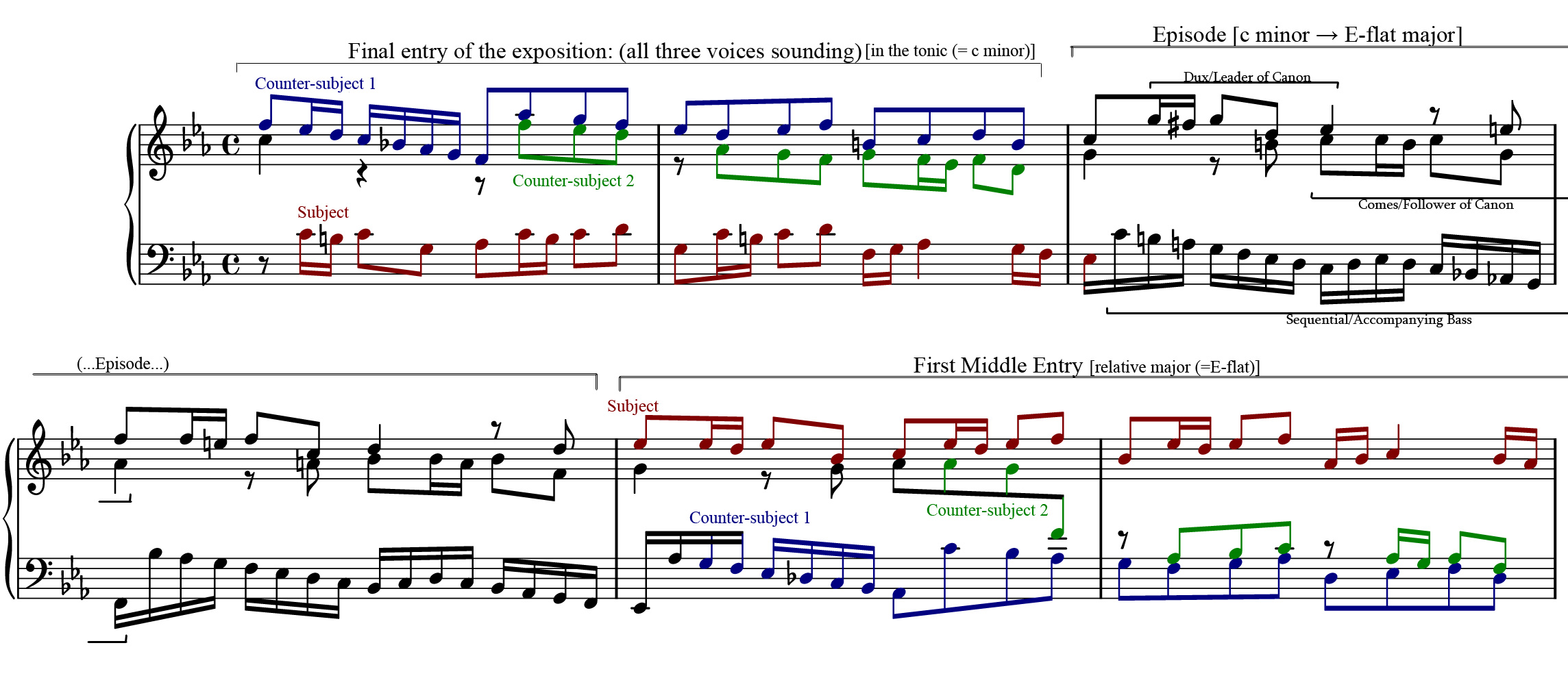

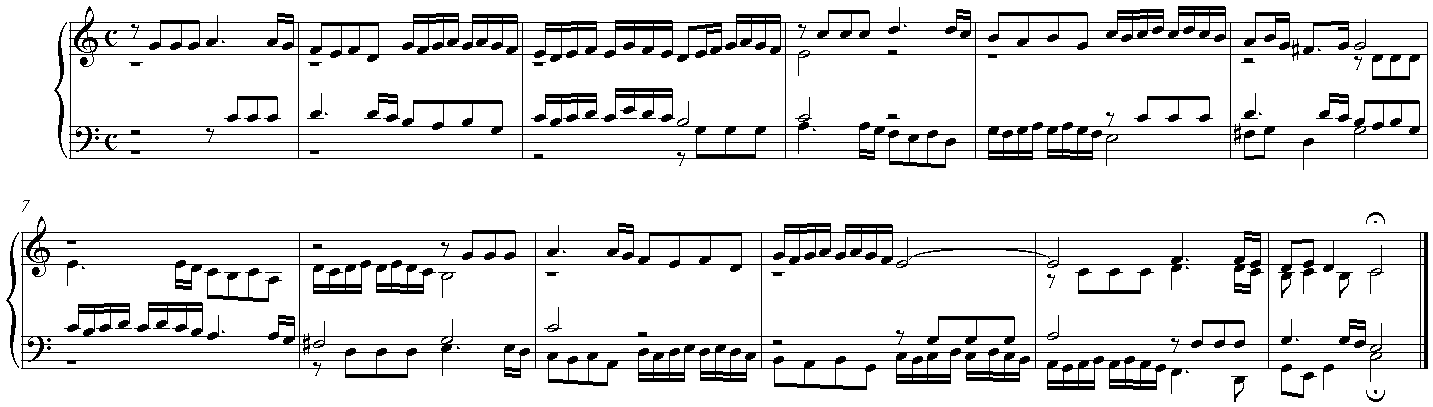

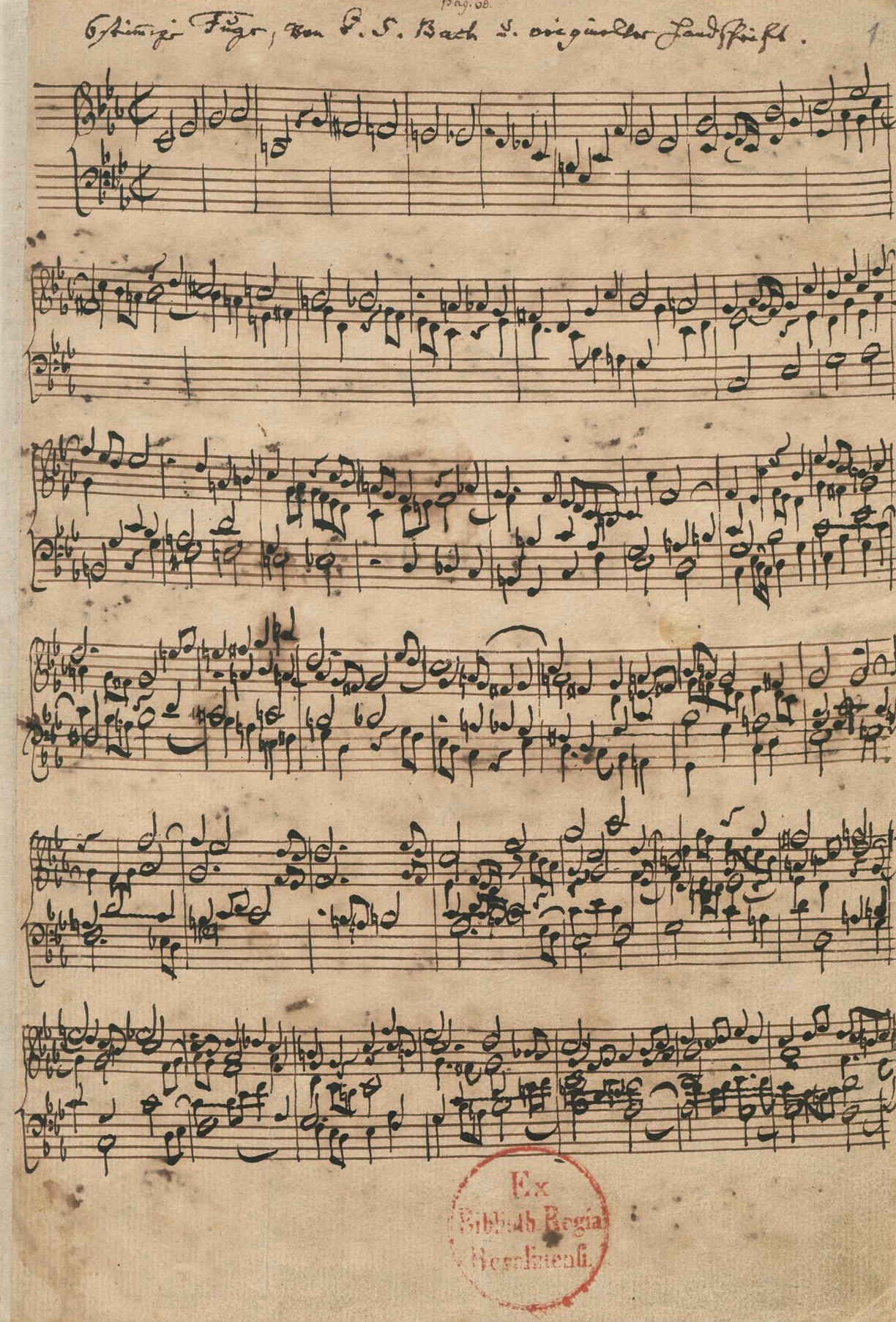

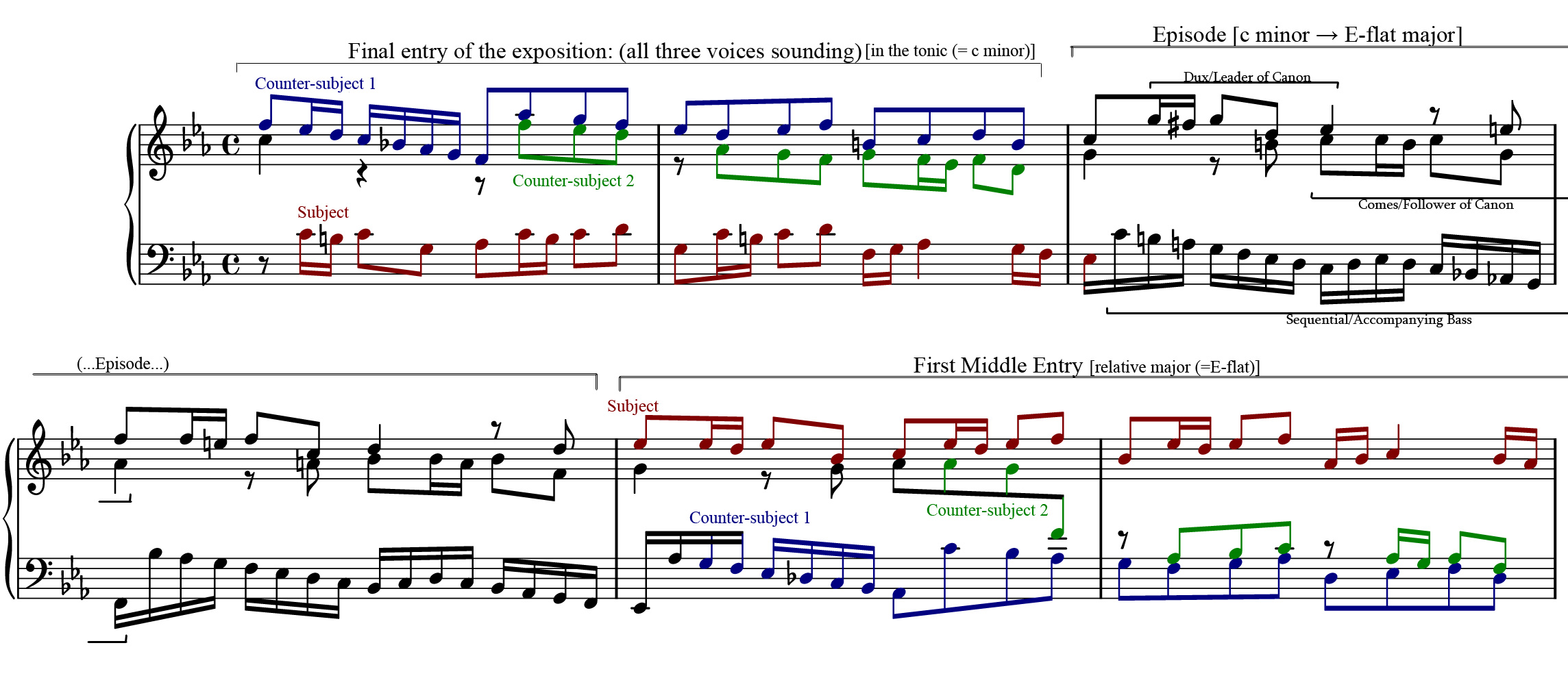

Example and analysis

The excerpt below, bars 7–12 of J.S. Bach's Fugue No. 2 in C minor, BWV 847, from the ''Well-Tempered Clavier'', Book 1 illustrates the application of most of the characteristics described above. The fugue is for keyboard and in three voices, with regular countersubjects. This excerpt opens at last entry of the exposition: the subject is sounding in the bass, the first countersubject in the treble, while the middle-voice is stating a second version of the second countersubject, which concludes with the characteristic rhythm of the subject, and is always used together with the first version of the second countersubject. Following this an episode modulates from the tonic to the relative major by means ofsequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is called ...

, in the form of an accompanied canon at the fourth. Arrival in E major is marked by a quasi perfect cadence across the bar line, from the last quarter note beat of the first bar to the first beat of the second bar in the second system, and the first middle entry. Here, Bach has altered the second countersubject to accommodate the change of mode.

False entries

At any point in the fugue there may be "false entries" of the subject, which include the start of the subject but are not completed. False entries are often abbreviated to the head of the subject, and anticipate the "true" entry of the subject, heightening the impact of the subject proper.

Counter-exposition

The counter-exposition is a second exposition. However, there are only two entries, and the entries occur in reverse order. The counter-exposition in a fugue is separated from the exposition by an episode and is in the same key as the original exposition.Stretto

Sometimes counter-expositions or the middle entries take place in ''stretto

In music, the Italian term ''stretto'' (plural: ''stretti'') has two distinct meanings:

# In a fugue, ''stretto'' (german: Engführung) is the imitation of the subject in close succession, so that the answer enters before the subject is complete ...

,'' whereby one voice responds with the subject/answer before the first voice has completed its entry of the subject/answer, usually increasing the intensity of the music.

Only one entry of the subject must be heard in its completion in a ''stretto''. However, a ''stretto'' in which the subject/answer is heard in completion in all voices is known as ''stretto maestrale'' or ''grand stretto''. ''Strettos'' may also occur by inversion, augmentation and diminution. A fugue in which the opening exposition takes place in ''stretto'' form is known as a ''close fugue'' or ''stretto fugue'' (see for example, the ''Gratias agimus tibi'' and ' choruses from J.S. Bach's

Only one entry of the subject must be heard in its completion in a ''stretto''. However, a ''stretto'' in which the subject/answer is heard in completion in all voices is known as ''stretto maestrale'' or ''grand stretto''. ''Strettos'' may also occur by inversion, augmentation and diminution. A fugue in which the opening exposition takes place in ''stretto'' form is known as a ''close fugue'' or ''stretto fugue'' (see for example, the ''Gratias agimus tibi'' and ' choruses from J.S. Bach's Mass in B Minor

The Mass in B minor (), BWV 232, is an extended setting of the Mass ordinary by Johann Sebastian Bach. The composition was completed in 1749, the year before the composer's death, and was to a large extent based on earlier work, such as a Sanct ...

).

Final entries and coda

The closing section of a fugue often includes one or two counter-expositions, and possibly a stretto, in the tonic; sometimes over a tonic or dominant pedal note. Any material that follows the final entry of the subject is considered to be the finalcoda

Coda or CODA may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* Movie coda, a post-credits scene

* ''Coda'' (1987 film), an Australian horror film about a serial killer, made for television

*''Coda'', a 2017 American experimental film from Na ...

and is normally cadential

In Western musical theory, a cadence (Latin ''cadentia'', "a falling") is the end of a phrase in which the melody or harmony creates a sense of full or partial resolution, especially in music of the 16th century onwards. Don Michael Randel (19 ...

.

Types

Simple fugue

A simple fugue has only one subject, and does not utilize invertible counterpoint.Double (triple, quadruple) fugue

A double fugue has two subjects that are often developed simultaneously. Similarly, a triple fugue has three subjects. There are two kinds of double (triple) fugue: (a) a fugue in which the second (third) subject is (are) presented simultaneously with the subject in the exposition (e.g. as inKyrie Eleison

Kyrie, a transliteration of Greek , vocative case of ('' Kyrios''), is a common name of an important prayer of Christian liturgy, also called the Kyrie eleison ( ; ).

In the Bible

The prayer, "Kyrie, eleison," "Lord, have mercy" derives f ...

of Mozart's Requiem in D minor

The Requiem in D minor, K. 626, is a requiem mass by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791). Mozart composed part of the Requiem in Vienna in late 1791, but it was unfinished at his death on 5 December the same year. A completed version dat ...

or the fugue of Bach's Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582

''Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor'' (BWV 582) is an organ piece by Johann Sebastian Bach. Presumably composed early in Bach's career, it is one of his most important and well-known works, and an important influence on 19th and 20th century pas ...

), and (b) a fugue in which all subjects have their own expositions at some point, and they are not combined until later (see for example, the three-subject Fugue No. 14 in F minor from Bach's ''Well-Tempered Clavier'' Book 2, or more famously, Bach's "St. Anne" Fugue in E major, BWV 552, a triple fugue for organ.)

Counter-fugue

A counter-fugue is a fugue in which the first answer is presented as the subject ininversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

(upside down), and the inverted subject continues to feature prominently throughout the fugue. Examples include ''Contrapunctus V'' through ''Contrapunctus VII'', from Bach's ''The Art of Fugue

''The Art of Fugue'', or ''The Art of the Fugue'' (german: Die Kunst der Fuge, links=no), BWV 1080, is an incomplete musical work of unspecified instrumentation by Johann Sebastian Bach. Written in the last decade of his life, ''The Art of F ...

''.

Permutation fugue

Permutation fugue describes a type of composition (or technique of composition) in which elements of fugue and strict canon are combined. Each voice enters in succession with the subject, each entry alternating between tonic and dominant, and each voice, having stated the initial subject, continues by stating two or more themes (or countersubjects), which must be conceived in correct invertible counterpoint. (In other words, the subject and countersubjects must be capable of being played both above and below all the other themes without creating any unacceptable dissonances.) Each voice takes this pattern and states all the subjects/themes in the same order (and repeats the material when all the themes have been stated, sometimes after a rest). There is usually very little non-structural/thematic material. During the course of a permutation fugue, it is quite uncommon, actually, for every single possible voice-combination (or "permutation") of the themes to be heard. This limitation exists in consequence of sheer proportionality: the more voices in a fugue, the greater the number of possible permutations. In consequence, composers exercise editorial judgment as to the most musical of permutations and processes leading thereto. One example of permutation fugue can be seen in the eighth and final chorus of J.S. Bach's cantata, ''Himmelskönig, sei willkommen'', BWV 182. Permutation fugues differ from conventional fugue in that there are no connecting episodes, nor statement of the themes in related keys. So for example, the fugue of Bach'sPassacaglia and Fugue in C minor, BWV 582

''Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor'' (BWV 582) is an organ piece by Johann Sebastian Bach. Presumably composed early in Bach's career, it is one of his most important and well-known works, and an important influence on 19th and 20th century pas ...

is not purely a permutation fugue, as it does have episodes between permutation expositions. Invertible counterpoint is essential to permutation fugues but is not found in simple fugues.

Fughetta

A fughetta is a short fugue that has the same characteristics as a fugue. Often the contrapuntal writing is not strict, and the setting less formal. See for example, variation 24 ofBeethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classic ...

's ''Diabelli Variations'' Op. 120.

History

Middle Ages and Renaissance

The term ''fuga'' was used as far back as theMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, but was initially used to refer to any kind of imitative counterpoint, including canons, which are now thought of as distinct from fugues. Prior to the 16th century, fugue was originally a genre. It was not until the 16th century that fugal technique as it is understood today began to be seen in pieces, both instrumental and vocal. Fugal writing is found in works such as fantasias, ricercar

A ricercar ( , ) or ricercare ( , ) is a type of late Renaissance and mostly early Baroque instrumental composition. The term ''ricercar'' derives from the Italian verb which means 'to search out; to seek'; many ricercars serve a preludial funct ...

es and canzonas.

"Fugue" as a theoretical term first occurred in 1330 when Jacobus of Liege wrote about the ''fuga'' in his ''Speculum musicae''. The fugue arose from the technique of "imitation", where the same musical material was repeated starting on a different note.

Gioseffo Zarlino

Gioseffo Zarlino (31 January or 22 March 1517 – 4 February 1590) was an Italian music theorist and composer of the Renaissance. He made a large contribution to the theory of counterpoint as well as to musical tuning.

Life and career

Zarlino w ...

, a composer, author, and theorist in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

, was one of the first to distinguish between the two types of imitative counterpoint: fugues and canons (which he called imitations). Originally, this was to aid improvisation

Improvisation is the activity of making or doing something not planned beforehand, using whatever can be found. Improvisation in the performing arts is a very spontaneous performance without specific or scripted preparation. The skills of impr ...

, but by the 1550s, it was considered a technique of composition. The composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina ( – 2 February 1594) was an Italian composer of late Renaissance music. The central representative of the Roman School, with Orlande de Lassus and Tomás Luis de Victoria, Palestrina is considered the leading ...

(1525?–1594) wrote masses using modal counterpoint and imitation, and fugal writing became the basis for writing motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to Marga ...

s as well. Palestrina's imitative motets differed from fugues in that each phrase of the text had a different subject which was introduced and worked out separately, whereas a fugue continued working with the same subject or subjects throughout the entire length of the piece.

Baroque era

It was in theBaroque period

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

that the writing of fugues became central to composition, in part as a demonstration of compositional expertise. Fugues were incorporated into a variety of musical forms. Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck ( ; April or May, 1562 – 16 October 1621) was a Dutch composer, organist, and pedagogue whose work straddled the end of the Renaissance and beginning of the Baroque eras. He was among the first major keyboard compo ...

, Girolamo Frescobaldi

Girolamo Alessandro Frescobaldi (; also Gerolamo, Girolimo, and Geronimo Alissandro; September 15831 March 1643) was an Italian composer and virtuoso keyboard player. Born in the Duchy of Ferrara, he was one of the most important composers of ...

, Johann Jakob Froberger

Johann Jakob Froberger (baptized 19 May 1616 – 7 May 1667) was a German Baroque composer, keyboard virtuoso, and organist. Among the most famous composers of the era, he was influential in developing the musical form of the suite of dances in ...

and Dieterich Buxtehude

Dieterich Buxtehude (; ; born Diderik Hansen Buxtehude; c. 1637 – 9 May 1707) was a Danish organist and composer of the Baroque period, whose works are typical of the North German organ school. As a composer who worked in various vocal ...

all wrote fugues, and George Frideric Handel included them in many of his oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

s. Keyboard suites from this time often conclude with a fugal gigue

The gigue (; ) or giga () is a lively baroque dance originating from the English jig. It was imported into France in the mid-17th centuryBellingham, Jane"gigue."''The Oxford Companion to Music''. Ed. Alison Latham. Oxford Music Online. 6 July 2 ...

. Domenico Scarlatti

Giuseppe Domenico Scarlatti, also known as Domingo or Doménico Scarlatti (26 October 1685-23 July 1757), was an Italian composer. He is classified primarily as a Baroque composer chronologically, although his music was influential in the devel ...

has only a few fugues among his corpus of over 500 harpsichord sonatas. The French overture

The French overture is a musical form widely used in the Baroque music, Baroque period. Its basic formal division is into two parts, which are usually enclosed by double bars and repeat signs. They are complementary in style (slow in dotted rhythm ...

featured a quick fugal section after a slow introduction. The second movement of a sonata da chiesa

Sonata da chiesa (Italian: "church sonata") is a 17th-century genre of musical composition for one or more melody instruments and is regarded an antecedent of later forms of 18th century instrumental music. It generally comprises four movements, t ...

, as written by Arcangelo Corelli

Arcangelo Corelli (, also , , ; 17 February 1653 – 8 January 1713) was an Italian composer and violinist of the Baroque era. His music was key in the development of the modern genres of sonata and concerto, in establishing the preeminence o ...

and others, was usually fugal.

The Baroque period also saw a rise in the importance of music theory. Some fugues during the Baroque period were pieces designed to teach contrapuntal technique to students. The most influential text was Johann Joseph Fux's ''Gradus Ad Parnassum

The Latin phrase ''gradus ad Parnassum'' means "steps to Parnassus". It is sometimes shortened to ''gradus''. The name ''Parnassus'' was used to denote the loftiest part of a mountain range in central Greece, a few kilometres north of Delphi, of wh ...

'' ("Steps to Parnassus

Mount Parnassus (; el, Παρνασσός, ''Parnassós'') is a mountain range of central Greece that is and historically has been especially valuable to the Greek nation and the earlier Greek city-states for many reasons. In peace, it offers ...

"), which appeared in 1725. This work laid out the terms of "species" of counterpoint, and offered a series of exercises to learn fugue writing. Fux's work was largely based on the practice of Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; grc, Πραίνεστος, ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Pre ...

's modal fugues. Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

studied from this book, and it remained influential into the nineteenth century. Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have le ...

, for example, taught counterpoint from his own summary of Fux and thought of it as the basis for formal structure.

Bach's most famous fugues are those for the harpsichord in ''The Well-Tempered Clavier

''The Well-Tempered Clavier'', BWV 846–893, consists of two sets of preludes and fugues in all 24 major and minor keys for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach. In the composer's time, ''clavier'', meaning keyboard, referred to a variety of ins ...

'', which many composers and theorists look at as the greatest model of fugue. ''The Well-Tempered Clavier'' comprises two volumes written in different times of Bach's life, each comprising 24 prelude and fugue pairs, one for each major and minor key. Bach is also known for his organ fugues, which are usually preceded by a prelude or toccata

Toccata (from Italian ''toccare'', literally, "to touch", with "toccata" being the action of touching) is a virtuoso piece of music typically for a keyboard or plucked string instrument featuring fast-moving, lightly fingered or otherwise vi ...

. ''The Art of Fugue'', BWV 1080, is a collection of fugues (and four canons) on a single theme that is gradually transformed as the cycle progresses. Bach also wrote smaller single fugues and put fugal sections or movements into many of his more general works. J.S. Bach's influence extended forward through his son C.P.E. Bach and through the theorist Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1718–1795) whose ''Abhandlung von der Fuge'' ("Treatise on the fugue", 1753) was largely based on J.S. Bach's work.

Classical era

During theClassical era

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, the fugue was no longer a central or even fully natural mode of musical composition. Nevertheless, both Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn ( , ; 31 March 173231 May 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the string quartet and piano trio. His contributions to musical form have le ...

and Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 17565 December 1791), baptised as Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart, was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical period. Despite his short life, his rapid pace of composition r ...

had periods of their careers in which they in some sense "rediscovered" fugal writing and used it frequently in their work.

Haydn

Joseph Haydn was the leader of fugal composition and technique in the Classical era. Haydn's most famous fugues can be found in his "Sun" Quartets (op. 20, 1772), of which three have fugal finales. This was a practice that Haydn repeated only once later in his quartet-writing career, with the finale of his String Quartet, Op. 50 No. 4 (1787). Some of the earliest examples of Haydn's use of counterpoint, however, are in three symphonies ( No. 3, No. 13, and No. 40) that date from 1762 to 1763. The earliest fugues, in both the symphonies and in the Baryton trios, exhibit the influence of Joseph Fux's treatise on counterpoint, ''Gradus ad Parnassum'' (1725), which Haydn studied carefully. Haydn's second fugal period occurred after he heard, and was greatly inspired by, theoratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is mus ...

s of Handel during his visits to London (1791–1793, 1794–1795). Haydn then studied Handel's techniques and incorporated Handelian fugal writing into the choruses of his mature oratorios '' The Creation'' and '' The Seasons,'' as well as several of his later symphonies, including No. 88, No. 95, and No. 101; and the late string quartets, Opus 71 no. 3 and (especially) Opus 76 no. 6.

Mozart

The young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart studied counterpoint with Padre Martini in Bologna. Under the employment of Archbishop Colloredo, and the musical influence of his predecessors and colleagues such asJohann Ernst Eberlin

Johann Ernst Eberlin (27 March 1702 – 19 June 1762) was a German composer and organist whose works bridge the baroque and classical eras. He was a prolific composer, chiefly of church organ and choral music. Marpurg claims he wrote as much ...

, Anton Cajetan Adlgasser, Michael Haydn

Johann Michael Haydn (; 14 September 173710 August 1806) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period, the younger brother of Joseph Haydn.

Life

Michael Haydn was born in 1737 in the Austrian village of Rohrau, near the Hungarian border ...

, and his own father, Leopold Mozart

Johann Georg Leopold Mozart (November 14, 1719 – May 28, 1787) was a German composer, violinist and theorist. He is best known today as the father and teacher of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and for his violin textbook '' Versuch einer gründliche ...

at the Salzburg Cathedral, the young Mozart composed ambitious fugues and contrapuntal passages in Catholic choral works such as Mass in C minor, K. 139 "Waisenhaus" (1768), Mass in C major, K. 66 "Dominicus" (1769),