Mineralogist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mineralogy is a subject of

Mineralogy is a subject of

Early writing on mineralogy, especially on gemstones, comes from ancient

Early writing on mineralogy, especially on gemstones, comes from ancient

An initial step in identifying a mineral is to examine its physical properties, many of which can be measured on a hand sample. These can be classified into

An initial step in identifying a mineral is to examine its physical properties, many of which can be measured on a hand sample. These can be classified into

The crystal structure is the arrangement of atoms in a crystal. It is represented by a lattice of points which repeats a basic pattern, called a

The crystal structure is the arrangement of atoms in a crystal. It is represented by a lattice of points which repeats a basic pattern, called a

A few minerals are

A few minerals are

In addition to macroscopic properties such as colour or lustre, minerals have properties that require a polarizing microscope to observe.

In addition to macroscopic properties such as colour or lustre, minerals have properties that require a polarizing microscope to observe.

The Virtual Museum of the History of Mineralogy

American Federation of Mineral SocietiesFrench Society of Mineralogy and CrystallographyGeological Society of AmericaGerman Mineralogical SocietyInternational Mineralogical AssociationItalian Mineralogical and Petrological SocietyMineralogical Association of CanadaMineralogical Society of Great Britain and IrelandMineralogical Society of America

{{Authority control

Mineralogy is a subject of

Mineralogy is a subject of geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of the constituent particles to form symmetric patterns t ...

, and physical (including optical

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

) properties of mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. ...

s and mineralized artifact Artifact, or artefact, may refer to:

Science and technology

* Artifact (error), misleading or confusing alteration in data or observation, commonly in experimental science, resulting from flaws in technique or equipment

** Compression artifact, a ...

s. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, as well as their utilization.

History

Early writing on mineralogy, especially on gemstones, comes from ancient

Early writing on mineralogy, especially on gemstones, comes from ancient Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state ...

, the ancient Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were dir ...

world, ancient and medieval China, and Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominalization, nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cul ...

texts from ancient India

According to consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by ...

and the ancient Islamic world. Books on the subject included the ''Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' ( la, Naturalis historia) is a work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. ...

'' of Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

, which not only described many different minerals but also explained many of their properties, and Kitab al Jawahir (Book of Precious Stones) by Persian scientist Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of ...

. The German Renaissance

The German Renaissance, part of the Northern Renaissance, was a cultural and artistic movement that spread among German thinkers in the 15th and 16th centuries, which developed from the Italian Renaissance. Many areas of the arts and sciences ...

specialist Georgius Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Pawer or Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman ...

wrote works such as '' De re metallica'' (''On Metals'', 1556) and '' De Natura Fossilium'' (''On the Nature of Rocks'', 1546) which began the scientific approach to the subject. Systematic scientific studies of minerals and rocks developed in post-Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

Europe. The modern study of mineralogy was founded on the principles of crystallography

Crystallography is the experimental science of determining the arrangement of atoms in crystalline solids. Crystallography is a fundamental subject in the fields of materials science and solid-state physics (condensed matter physics). The wo ...

(the origins of geometric crystallography, itself, can be traced back to the mineralogy practiced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) and to the microscopic

The microscopic scale () is the scale of objects and events smaller than those that can easily be seen by the naked eye, requiring a lens or microscope to see them clearly. In physics, the microscopic scale is sometimes regarded as the scale be ...

study of rock sections with the invention of the microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisibl ...

in the 17th century.

Nicholas Steno first observed the law of constancy of interfacial angles (also known as the first law of crystallography) in quartz crystals in 1669. This was later generalized and established experimentally by Jean-Baptiste L. Romé de l'Islee in 1783. René Just Haüy, the "father of modern crystallography", showed that crystals are periodic and established that the orientations of crystal faces can be expressed in terms of rational numbers, as later encoded in the Miller indices. In 1814, Jöns Jacob Berzelius

Baron Jöns Jacob Berzelius (; by himself and his contemporaries named only Jacob Berzelius, 20 August 1779 – 7 August 1848) was a Swedish chemist. Berzelius is considered, along with Robert Boyle, John Dalton, and Antoine Lavoisier, to be ...

introduced a classification of minerals based on their chemistry rather than their crystal structure. William Nicol developed the Nicol prism

A Nicol prism is a type of polarizer, an optical device made from calcite crystal used to produce and analyse plane polarized light. It is made in such a way that it eliminates one of the rays by total internal reflection, i.e. the ordinary ...

, which polarizes light, in 1827–1828 while studying fossilized wood; Henry Clifton Sorby showed that thin sections of minerals could be identified by their optical properties using a polarizing microscope. James D. Dana published his first edition of ''A System of Mineralogy'' in 1837, and in a later edition introduced a chemical classification that is still the standard. X-ray diffraction was demonstrated by Max von Laue

Max Theodor Felix von Laue (; 9 October 1879 – 24 April 1960) was a German physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 for his discovery of the diffraction of X-rays by crystals.

In addition to his scientific endeavors with con ...

in 1912, and developed into a tool for analyzing the crystal structure of minerals by the father/son team of William Henry Bragg

Sir William Henry Bragg (2 July 1862 – 12 March 1942) was an English physicist, chemist, mathematician, and active sportsman who uniquelyThis is still a unique accomplishment, because no other parent-child combination has yet shared a Nobel ...

and William Lawrence Bragg

Sir William Lawrence Bragg, (31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971) was an Australian-born British physicist and X-ray crystallographer, discoverer (1912) of Bragg's law of X-ray diffraction, which is basic for the determination of crystal structu ...

.

More recently, driven by advances in experimental technique (such as neutron diffraction) and available computational power, the latter of which has enabled extremely accurate atomic-scale simulations of the behaviour of crystals, the science has branched out to consider more general problems in the fields of inorganic chemistry

Inorganic chemistry deals with synthesis and behavior of inorganic and organometallic compounds. This field covers chemical compounds that are not carbon-based, which are the subjects of organic chemistry. The distinction between the two disc ...

and solid-state physics. It, however, retains a focus on the crystal structures commonly encountered in rock-forming minerals (such as the perovskites, clay minerals

Clay minerals are hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates (e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4), sometimes with variable amounts of iron, magnesium, alkali metals, alkaline earths, and other cations found on or near some planetary surfaces.

Clay mineral ...

and framework silicates). In particular, the field has made great advances in the understanding of the relationship between the atomic-scale structure of minerals and their function; in nature, prominent examples would be accurate measurement and prediction of the elastic properties of minerals, which has led to new insight into seismological behaviour of rocks and depth-related discontinuities in seismograms of the Earth's mantle

Earth's mantle is a layer of silicate rock between the crust and the outer core. It has a mass of 4.01 × 1024 kg and thus makes up 67% of the mass of Earth. It has a thickness of making up about 84% of Earth's volume. It is predominantly so ...

. To this end, in their focus on the connection between atomic-scale phenomena and macroscopic properties, the ''mineral sciences'' (as they are now commonly known) display perhaps more of an overlap with materials science than any other discipline.

Physical properties

An initial step in identifying a mineral is to examine its physical properties, many of which can be measured on a hand sample. These can be classified into

An initial step in identifying a mineral is to examine its physical properties, many of which can be measured on a hand sample. These can be classified into density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematicall ...

(often given as specific gravity

Relative density, or specific gravity, is the ratio of the density (mass of a unit volume) of a substance to the density of a given reference material. Specific gravity for liquids is nearly always measured with respect to water (molecule), wa ...

); measures of mechanical cohesion (hardness

In materials science, hardness (antonym: softness) is a measure of the resistance to localized plastic deformation induced by either mechanical indentation or abrasion (mechanical), abrasion. In general, different materials differ in their hardn ...

, tenacity

Tenacity may refer to:

* Tenacity (psychology), having persistence in purpose

* Tenacity (mineralogy) a mineral's resistance to breaking or deformation

* Tenacity (herbicide), a brand name for a selective herbicide

* Tenacity (textile strength)

* ...

, cleavage, fracture, parting); macroscopic visual properties ( luster, color, streak, luminescence

Luminescence is spontaneous emission of light by a substance not resulting from heat; or "cold light".

It is thus a form of cold-body radiation. It can be caused by chemical reactions, electrical energy, subatomic motions or stress on a crysta ...

, diaphaneity); magnetic and electric properties; radioactivity and solubility in hydrogen chloride

The compound hydrogen chloride has the chemical formula and as such is a hydrogen halide. At room temperature, it is a colourless gas, which forms white fumes of hydrochloric acid upon contact with atmospheric water vapor. Hydrogen chloride g ...

().

''Hardness'' is determined by comparison with other minerals. In the Mohs scale

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness () is a qualitative ordinal scale, from 1 to 10, characterizing scratch resistance of various minerals through the ability of harder material to scratch softer material.

The scale was introduced in 1812 by the ...

, a standard set of minerals are numbered in order of increasing hardness from 1 (talc) to 10 (diamond). A harder mineral will scratch a softer, so an unknown mineral can be placed in this scale, by which minerals; it scratches and which scratch it. A few minerals such as calcite

Calcite is a carbonate mineral and the most stable polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scra ...

and kyanite have a hardness that depends significantly on direction. Hardness can also be measured on an absolute scale using a sclerometer; compared to the absolute scale, the Mohs scale is nonlinear.

''Tenacity'' refers to the way a mineral behaves, when it is broken, crushed, bent or torn. A mineral can be brittle

A material is brittle if, when subjected to stress, it fractures with little elastic deformation and without significant plastic deformation. Brittle materials absorb relatively little energy prior to fracture, even those of high strength. ...

, malleable

Ductility is a mechanical property commonly described as a material's amenability to drawing (e.g. into wire). In materials science, ductility is defined by the degree to which a material can sustain plastic deformation under tensile stres ...

, sectile, ductile

Ductility is a mechanical property commonly described as a material's amenability to drawing (e.g. into wire). In materials science, ductility is defined by the degree to which a material can sustain plastic deformation under tensile stres ...

, flexible or elastic. An important influence on tenacity is the type of chemical bond (''e.g.,'' ionic or metallic).

Of the other measures of mechanical cohesion, ''cleavage'' is the tendency to break along certain crystallographic planes. It is described by the quality (''e.g.'', perfect or fair) and the orientation of the plane in crystallographic nomenclature.

''Parting'' is the tendency to break along planes of weakness due to pressure, twinning or exsolution. Where these two kinds of break do not occur, ''fracture'' is a less orderly form that may be ''conchoidal

Conchoidal fracture describes the way that brittle materials break or fracture when they do not follow any natural planes of separation. Mindat.org defines conchoidal fracture as follows: "a fracture with smooth, curved surfaces, typically slig ...

'' (having smooth curves resembling the interior of a shell), ''fibrous'', ''splintery'', ''hackly'' (jagged with sharp edges), or ''uneven''.

If the mineral is well crystallized, it will also have a distinctive crystal habit

In mineralogy, crystal habit is the characteristic external shape of an individual crystal or crystal group. The habit of a crystal is dependent on its crystallographic form and growth conditions, which generally creates irregularities due to l ...

(for example, hexagonal, columnar, botryoidal) that reflects the crystal structure

In crystallography, crystal structure is a description of the ordered arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules in a crystalline material. Ordered structures occur from the intrinsic nature of the constituent particles to form symmetric patterns t ...

or internal arrangement of atoms. It is also affected by crystal defects and twinning. Many crystals are polymorphic, having more than one possible crystal structure depending on factors such as pressure and temperature.

Crystal structure

The crystal structure is the arrangement of atoms in a crystal. It is represented by a lattice of points which repeats a basic pattern, called a

The crystal structure is the arrangement of atoms in a crystal. It is represented by a lattice of points which repeats a basic pattern, called a unit cell

In geometry, biology, mineralogy and solid state physics, a unit cell is a repeating unit formed by the vectors spanning the points of a lattice. Despite its suggestive name, the unit cell (unlike a unit vector, for example) does not necessari ...

, in three dimensions. The lattice can be characterized by its symmetries and by the dimensions of the unit cell. These dimensions are represented by three ''Miller indices

Miller indices form a notation system in crystallography for lattice planes in crystal (Bravais) lattices.

In particular, a family of lattice planes of a given (direct) Bravais lattice is determined by three integers ''h'', ''k'', and ''� ...

''. The lattice remains unchanged by certain symmetry operations about any given point in the lattice: reflection, rotation

Rotation, or spin, is the circular movement of an object around a '' central axis''. A two-dimensional rotating object has only one possible central axis and can rotate in either a clockwise or counterclockwise direction. A three-dimensional ...

, inversion

Inversion or inversions may refer to:

Arts

* , a French gay magazine (1924/1925)

* ''Inversion'' (artwork), a 2005 temporary sculpture in Houston, Texas

* Inversion (music), a term with various meanings in music theory and musical set theory

* ...

, and rotary inversion, a combination of rotation and reflection. Together, they make up a mathematical object called a '' crystallographic point group'' or ''crystal class''. There are 32 possible crystal classes. In addition, there are operations that displace all the points: translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

, screw axis, and glide plane. In combination with the point symmetries, they form 230 possible space group

In mathematics, physics and chemistry, a space group is the symmetry group of an object in space, usually in three dimensions. The elements of a space group (its symmetry operations) are the rigid transformations of an object that leave it ...

s.

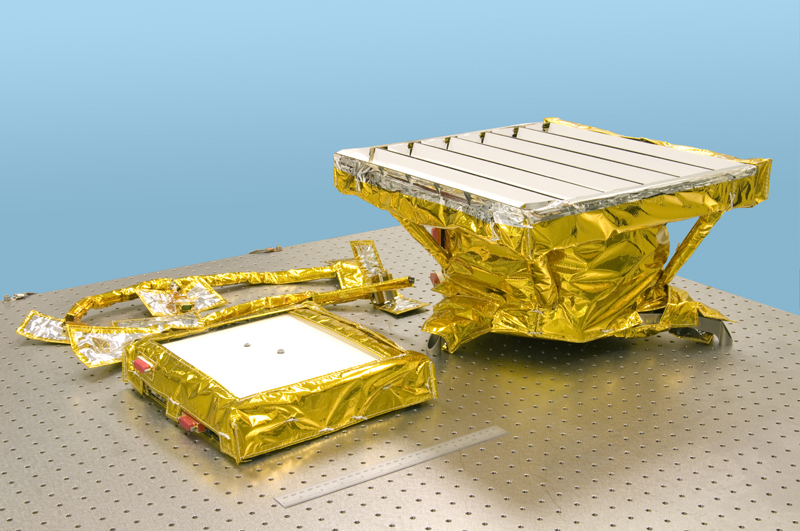

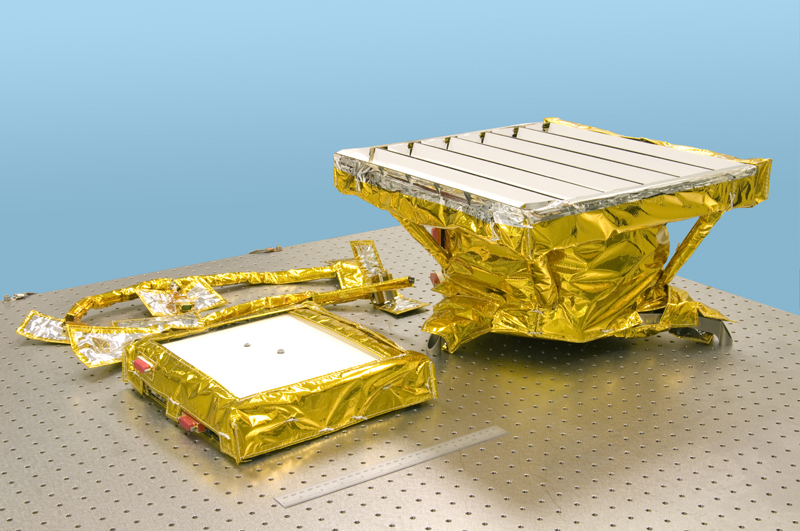

Most geology departments have X-ray

X-rays (or rarely, ''X-radiation'') are a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. In many languages, it is referred to as Röntgen radiation, after the German scientist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, who discovered it in 1895 and named it ' ...

powder diffraction

Powder diffraction is a scientific technique using X-ray, neutron, or electron diffraction on powder or microcrystalline samples for structural characterization of materials. An instrument dedicated to performing such powder measurements is cal ...

equipment to analyze the crystal structures of minerals. X-rays have wavelengths that are the same order of magnitude as the distances between atoms. Diffraction, the constructive and destructive interference between waves scattered at different atoms, leads to distinctive patterns of high and low intensity that depend on the geometry of the crystal. In a sample that is ground to a powder, the X-rays sample a random distribution of all crystal orientations. Powder diffraction can distinguish between minerals that may appear the same in a hand sample, for example quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica ( silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical ...

and its polymorphs tridymite

Tridymite is a high-temperature polymorph of silica and usually occurs as minute tabular white or colorless pseudo-hexagonal crystals, or scales, in cavities in felsic volcanic rocks. Its chemical formula is Si O2. Tridymite was first described ...

and cristobalite

Cristobalite is a mineral polymorph of silica that is formed at very high temperatures. It has the same chemical formula as quartz, SiO2, but a distinct crystal structure. Both quartz and cristobalite are polymorphs with all the members of the q ...

.

Isomorphous minerals of different compositions have similar powder diffraction patterns, the main difference being in spacing and intensity of lines. For example, the (halite

Halite (), commonly known as rock salt, is a type of salt, the mineral (natural) form of sodium chloride ( Na Cl). Halite forms isometric crystals. The mineral is typically colorless or white, but may also be light blue, dark blue, purple, ...

) crystal structure is space group ''Fm3m''; this structure is shared by sylvite

Sylvite, or sylvine, is potassium chloride (KCl) in natural mineral form. It forms crystals in the isometric system very similar to normal rock salt, halite ( NaCl). The two are, in fact, isomorphous. Sylvite is colorless to white with shades of ...

(), periclase (), bunsenite

Bunsenite is the naturally occurring form of nickel(II) oxide, NiO. It occurs as rare dark green crystal coatings. It crystallizes in the cubic crystal system and occurs as well formed cubic, octahedral and dodecahedral crystals. It is a member of ...

(), galena

Galena, also called lead glance, is the natural mineral form of lead(II) sulfide (PbS). It is the most important ore of lead and an important source of silver.

Galena is one of the most abundant and widely distributed sulfide minerals. It cry ...

(), alabandite (), chlorargyrite (), and osbornite ().

Chemical elements

A few minerals are

A few minerals are chemical element

A chemical element is a species of atoms that have a given number of protons in their nuclei, including the pure substance consisting only of that species. Unlike chemical compounds, chemical elements cannot be broken down into simpler sub ...

s, including sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish ...

, silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

, and gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

, but the vast majority are compounds. The classical method for identifying composition is '' wet chemical analysis'', which involves dissolving a mineral in an acid such as hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid. It is a component of the gastric acid in the dig ...

(HCl). The elements in solution are then identified using colorimetry

Colorimetry is "the science and technology used to quantify and describe physically the human color perception".

It is similar to spectrophotometry, but is distinguished by its interest in reducing spectra to the physical correlates of color ...

, volumetric analysis or gravimetric analysis

Gravimetric analysis describes a set of methods used in analytical chemistry

Analytical chemistry studies and uses instruments and methods to separate, identify, and quantify matter. In practice, separation, identification or quantificati ...

.

Since 1960, most chemistry analysis is done using instruments. One of these, atomic absorption spectroscopy

Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and atomic emission spectroscopy (AES) is a spectroanalytical procedure for the quantitative determination of chemical elemlight) by free atoms in the gaseous state. Atomic absorption spectroscopy is based o ...

, is similar to wet chemistry in that the sample must still be dissolved, but it is much faster and cheaper. The solution is vaporized and its absorption spectrum is measured in the visible and ultraviolet range. Other techniques are X-ray fluorescence

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) is the emission of characteristic "secondary" (or fluorescent) X-rays from a material that has been excited by being bombarded with high-energy X-rays or gamma rays. The phenomenon is widely used for elemental analysis ...

, electron microprobe

An electron microprobe (EMP), also known as an electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA) or electron micro probe analyzer (EMPA), is an analytical tool used to non-destructively determine the chemical composition of small volumes of solid materials. It ...

analysis atom probe tomography and optical emission spectrography.

Optical

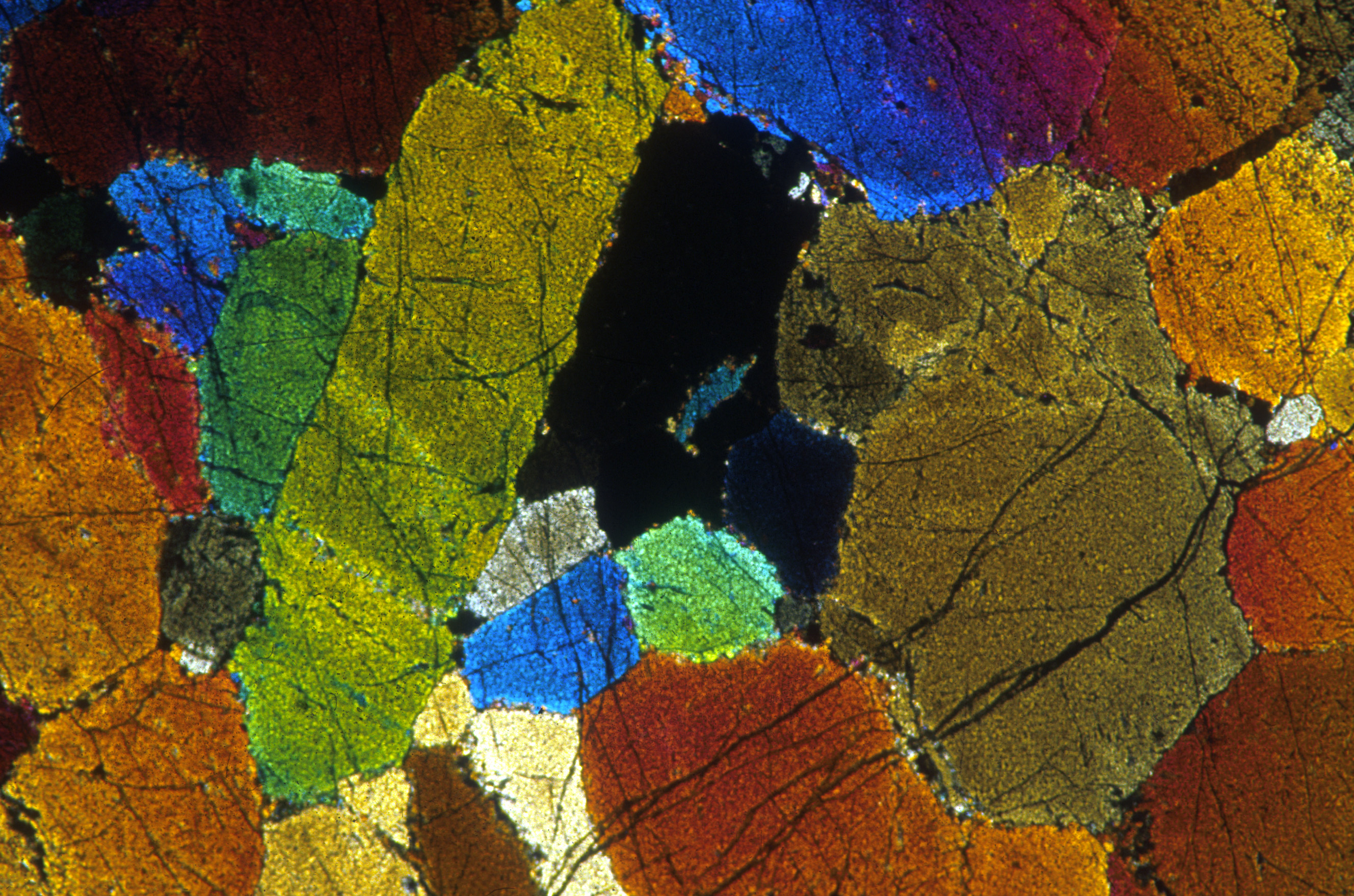

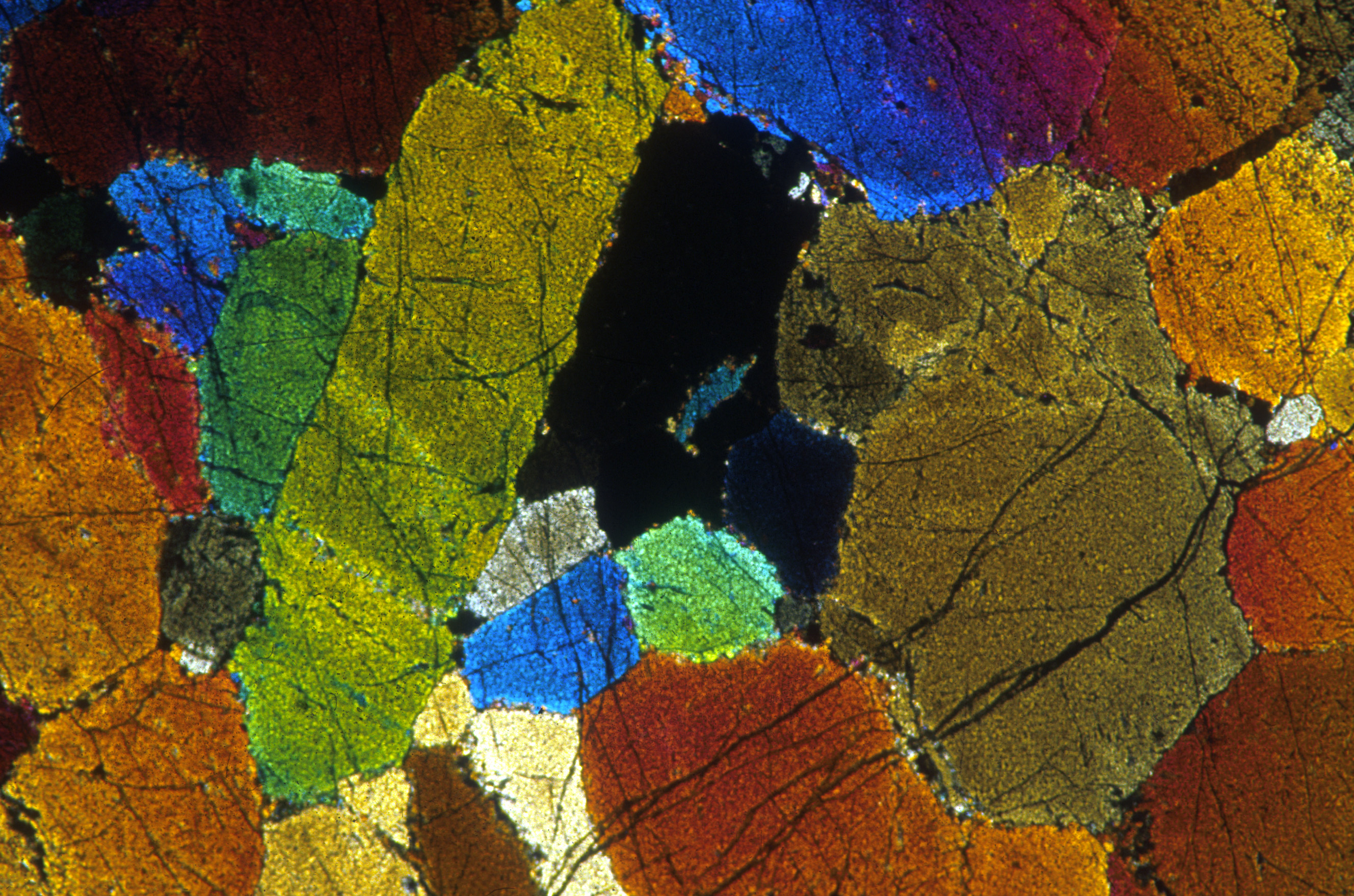

In addition to macroscopic properties such as colour or lustre, minerals have properties that require a polarizing microscope to observe.

In addition to macroscopic properties such as colour or lustre, minerals have properties that require a polarizing microscope to observe.

Transmitted light

When light passes from air or avacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or " void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often di ...

into a transparent crystal, some of it is reflected Reflection or reflexion may refer to:

Science and technology

* Reflection (physics), a common wave phenomenon

** Specular reflection, reflection from a smooth surface

*** Mirror image, a reflection in a mirror or in water

** Signal reflection, in ...

at the surface and some refracted. The latter is a bending of the light path that occurs because the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant that is important in many areas of physics. The speed of light is exactly equal to ). According to the special theory of relativity, is the upper limit fo ...

changes as it goes into the crystal; Snell's law

Snell's law (also known as Snell–Descartes law and ibn-Sahl law and the law of refraction) is a formula used to describe the relationship between the angles of incidence and refraction, when referring to light or other waves passing through ...

relates the bending angle

In Euclidean geometry, an angle is the figure formed by two rays, called the '' sides'' of the angle, sharing a common endpoint, called the '' vertex'' of the angle.

Angles formed by two rays lie in the plane that contains the rays. Angles ...

to the Refractive index

In optics, the refractive index (or refraction index) of an optical medium is a dimensionless number that gives the indication of the light bending ability of that medium.

The refractive index determines how much the path of light is bent, o ...

, the ratio of speed in a vacuum to speed in the crystal. Crystals whose point symmetry group falls in the cubic system

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties of ...

are ''isotropic'': the index does not depend on direction. All other crystals are ''anisotropic'': light passing through them is broken up into two plane polarized rays that travel at different speeds and refract at different angles.

A polarizing microscope is similar to an ordinary microscope, but it has two plane-polarized filters, a (''polarizer

A polarizer or polariser is an optical filter that lets light waves of a specific polarization pass through while blocking light waves of other polarizations. It can filter a beam of light of undefined or mixed polarization into a beam of well ...

'') below the sample and an analyzer above it, polarized perpendicular to each other. Light passes successively through the polarizer, the sample and the analyzer. If there is no sample, the analyzer blocks all the light from the polarizer. However, an anisotropic sample will generally change the polarization so some of the light can pass through. Thin sections and powders can be used as samples.

When an isotropic crystal is viewed, it appears dark because it does not change the polarization of the light. However, when it is immersed in a calibrated liquid with a lower index of refraction and the microscope is thrown out of focus, a bright line called a '' Becke line'' appears around the perimeter of the crystal. By observing the presence or absence of such lines in liquids with different indices, the index of the crystal can be estimated, usually to within .

Systematic

Systematic mineralogy is the identification and classification of minerals by their properties. Historically, mineralogy was heavily concerned withtaxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

of the rock-forming minerals. In 1959, the International Mineralogical Association

Founded in 1958, the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) is an international group of 40 national societies. The goal is to promote the science of mineralogy and to standardize the nomenclature of the 5000 plus known mineral species. Th ...

formed the Commission of New Minerals and Mineral Names to rationalize the nomenclature and regulate the introduction of new names. In July 2006, it was merged with the Commission on Classification of Minerals to form the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature, and Classification. There are over 6,000 named and unnamed minerals, and about 100 are discovered each year. The ''Manual of Mineralogy'' places minerals in the following classes: native elements, sulfides

Sulfide ( British English also sulphide) is an inorganic anion of sulfur with the chemical formula S2− or a compound containing one or more S2− ions. Solutions of sulfide salts are corrosive. ''Sulfide'' also refers to chemical compounds ...

, sulfosalts

Sulfosalt minerals are sulfide minerals with the general formula , where

*A represents a metal such as copper, lead, silver, iron, and rarely mercury, zinc, vanadium

*B usually represents semi-metal such as arsenic, antimony, bismuth, a ...

, oxides and hydroxides, halides, carbonates, nitrates and borates, sulfates, chromates, molybdates and tungstates, phosphates, arsenates and vanadates, and silicates.

Formation environments

The environments of mineral formation and growth are highly varied, ranging from slow crystallization at the high temperatures and pressures ofigneous

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma o ...

melts deep within the Earth's crust to the low temperature precipitation from a saline brine at the Earth's surface.

Various possible methods of formation include:

*sublimation

Sublimation or sublimate may refer to:

* ''Sublimation'' (album), by Canvas Solaris, 2004

* Sublimation (phase transition), directly from the solid to the gas phase

* Sublimation (psychology), a mature type of defense mechanism

* Sublimate of mer ...

from volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates ...

gases

*deposition from aqueous solution

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, or sodium chloride (NaCl), in water would ...

s and hydrothermal

Hydrothermal circulation in its most general sense is the circulation of hot water (Ancient Greek ὕδωρ, ''water'',Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with th ...

brine

Brine is a high-concentration Solution (chemistry), solution of salt (NaCl) in water (H2O). In diverse contexts, ''brine'' may refer to the salt solutions ranging from about 3.5% (a typical concentration of seawater, on the lower end of that of ...

s

*crystallization from an igneous

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma o ...

magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natura ...

or lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock ( magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a fracture in the crust, on land or ...

*recrystallization due to metamorphic

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock ( protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, cau ...

processes and metasomatism

Metasomatism (from the Greek μετά ''metá'' "change" and σῶμα ''sôma'' "body") is the chemical alteration of a rock by hydrothermal and other fluids. It is the replacement of one rock by another of different mineralogical and chemical c ...

*crystallization during diagenesis

Diagenesis () is the process that describes physical and chemical changes in sediments first caused by water-rock interactions, microbial activity, and compaction after their deposition. Increased pressure and temperature only start to play ...

of sediments

*formation by oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a ...

and weathering

Weathering is the deterioration of rocks, soils and minerals as well as wood and artificial materials through contact with water, atmospheric gases, and biological organisms. Weathering occurs '' in situ'' (on site, with little or no movemen ...

of rocks exposed to the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. ...

or within the soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former ...

environment.

Biomineralogy

Biomineralogy is a cross-over field between mineralogy,paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fos ...

and biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditar ...

. It is the study of how plants and animals stabilize minerals under biological control, and the sequencing of mineral replacement of those minerals after deposition. It uses techniques from chemical mineralogy, especially isotopic studies, to determine such things as growth forms in living plants and animals as well as things like the original mineral content of fossils.

A new approach to mineralogy called mineral evolution

Mineral evolution is a recent hypothesis that provides historical context to mineralogy. It postulates that mineralogy on planets and moons becomes increasingly complex as a result of changes in the physical, chemical and biological environment. ...

explores the co-evolution of the geosphere and biosphere, including the role of minerals in the origin of life and processes as mineral-catalyzed organic synthesis and the selective adsorption of organic molecules on mineral surfaces.

Mineral ecology

In 2011, several researchers began to develop a Mineral Evolution Database. This database integrates thecrowd-sourced

Crowdsourcing involves a large group of dispersed participants contributing or producing goods or services—including ideas, votes, micro-tasks, and finances—for payment or as volunteers. Contemporary crowdsourcing often involves digita ...

site Mindat.org

Mindat.org is a non-commercial online database, claiming to be the largest mineral database and mineralogy, mineralogical reference website on the Internet. It is used by professional mineralogists, geologists, and amateur mineral collecting, mi ...

, which has over 690,000 mineral-locality pairs, with the official IMA list of approved minerals and age data from geological publications.

This database makes it possible to apply statistics to answer new questions, an approach that has been called ''mineral ecology''. One such question is how much of mineral evolution is deterministic and how much the result of chance. Some factors are deterministic, such as the chemical nature of a mineral and conditions for its stability

Stability may refer to:

Mathematics

* Stability theory, the study of the stability of solutions to differential equations and dynamical systems

** Asymptotic stability

** Linear stability

** Lyapunov stability

** Orbital stability

** Structural st ...

; but mineralogy can also be affected by the processes that determine a planet's composition. In a 2015 paper, Robert Hazen and others analyzed the number of minerals involving each element as a function of its abundance. They found that Earth, with over 4800 known minerals and 72 elements, has a power law

In statistics, a power law is a functional relationship between two quantities, where a relative change in one quantity results in a proportional relative change in the other quantity, independent of the initial size of those quantities: one qua ...

relationship. The Moon, with only 63 minerals and 24 elements (based on a much smaller sample) has essentially the same relationship. This implies that, given the chemical composition of the planet, one could predict the more common minerals. However, the distribution has a long tail

In statistics and business, a long tail of some distributions of numbers is the portion of the distribution having many occurrences far from the "head" or central part of the distribution. The distribution could involve popularities, random ...

, with 34% of the minerals having been found at only one or two locations. The model predicts that thousands more mineral species may await discovery or have formed and then been lost to erosion, burial or other processes. This implies a role of chance in the formation of rare minerals occur.

In another use of big data sets, network theory

Network theory is the study of graphs as a representation of either symmetric relations or asymmetric relations between discrete objects. In computer science and network science, network theory is a part of graph theory: a network can be de ...

was applied to a dataset of carbon minerals, revealing new patterns in their diversity and distribution. The analysis can show which minerals tend to coexist and what conditions (geological, physical, chemical and biological) are associated with them. This information can be used to predict where to look for new deposits and even new mineral species.

Uses

Minerals are essential to various needs within human society, such as minerals used as ores for essential components of metal products used in variouscommodities

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

The price of a co ...

and machinery

A machine is a physical system using power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromolecul ...

, essential components to building materials such as limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms wh ...

, marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorpho ...

, granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies und ...

, gravel

Gravel is a loose aggregation of rock fragments. Gravel occurs naturally throughout the world as a result of sedimentary and erosive geologic processes; it is also produced in large quantities commercially as crushed stone.

Gravel is classif ...

, glass

Glass is a non-Crystallinity, crystalline, often transparency and translucency, transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most ...

, plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "r ...

, cement

A cement is a binder, a chemical substance used for construction that sets, hardens, and adheres to other materials to bind them together. Cement is seldom used on its own, but rather to bind sand and gravel (aggregate) together. Cement m ...

, etc. Minerals are also used in fertilizer

A fertilizer (American English) or fertiliser (British English; see spelling differences) is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from ...

s to enrich the growth of agricultural

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peopl ...

crops.

Collecting

Mineral collecting is also a recreational study and collectionhobby

A hobby is considered to be a regular activity that is done for enjoyment, typically during one's leisure time. Hobbies include collecting themed items and objects, engaging in creative and artistic pursuits, playing sports, or pursuing ...

, with clubs and societies representing the field. Museums, such as the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History Hall of Geology, Gems, and Minerals, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County is the largest natural and historical museum in the western United States. Its collections include nearly 35 million specimens and artifacts and cover 4.5 billion years of history. This large coll ...

, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History

The Carnegie Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as CMNH) is a natural history museum in the Oakland neighborhood of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was founded by Pittsburgh-based industrialist Andrew Carnegie in 1896.

Housing some 22 million ...

, the Natural History Museum, London

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum ...

, and the private Mim Mineral Museum in Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

, have popular collections of mineral specimens on permanent display.

See also

*List of minerals

This is a list of minerals for which there are articles on Wikipedia.

Minerals are distinguished by various chemical and physical properties. Differences in chemical composition and crystal structure distinguish the various ''species''. Within a m ...

* List of minerals recognized by the International Mineralogical Association

Mineralogy is an active science in which minerals are discovered or recognised on a regular basis. Use of old mineral names is also discontinued, for example when a name is no longer considered valid. Therefore, a list of recognised mineral specie ...

* List of mineralogists

* List of publications in mineralogy

* Mineral collecting

* Mineral physics

Mineral physics is the science of materials that compose the interior of planets, particularly the Earth. It overlaps with petrophysics, which focuses on whole-rock properties. It provides information that allows interpretation of surface measurem ...

* Metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sci ...

* Petrology

Petrology () is the branch of geology that studies rocks and the conditions under which they form. Petrology has three subdivisions: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary petrology. Igneous and metamorphic petrology are commonly taught together ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *External links

The Virtual Museum of the History of Mineralogy

Associations

American Federation of Mineral Societies

{{Authority control