Metaphysics is the branch of

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

that studies the fundamental nature of

reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent within a system, as opposed to that which is only imaginary. The term is also used to refer to the ontological status of things, indicating their existence. In physical terms, r ...

, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of

consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience and awareness of internal and external existence. However, the lack of definitions has led to millennia of analyses, explanations and debates by philosophers, theologians, linguisticians, and scien ...

and the relationship between

mind

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for all mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various m ...

and

matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic partic ...

, between

substance

Substance may refer to:

* Matter, anything that has mass and takes up space

Chemistry

* Chemical substance, a material with a definite chemical composition

* Drug substance

** Substance abuse, drug-related healthcare and social policy diagnosis ...

and

attribute

Attribute may refer to:

* Attribute (philosophy), an extrinsic property of an object

* Attribute (research), a characteristic of an object

* Grammatical modifier, in natural languages

* Attribute (computing), a specification that defines a prope ...

, and between

potentiality and actuality

In philosophy, potentiality and actuality are a pair of closely connected principles which Aristotle used to analyze motion, causality, ethics, and physiology in his ''Physics'', ''Metaphysics'', ''Nicomachean Ethics'', and ''De Anima''.

The c ...

. The word "metaphysics" comes from two Greek words that, together, literally mean "after or behind or among

he study of

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

the natural". It has been suggested that the term might have been coined by a first century CE editor who assembled various small selections of

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

's works into the treatise we now know by the name

''Metaphysics'' (μετὰ τὰ φυσικά, ''meta ta physika'', 'after the

''Physics'' ', another of Aristotle's works).

Metaphysics studies questions related to what it is for something to exist and what types of existence there are. Metaphysics seeks to answer, in an abstract and fully general manner, the questions of:

* What

* What it is

Topics of metaphysical investigation include

existence

Existence is the ability of an entity to interact with reality. In philosophy, it refers to the ontology, ontological Property (philosophy), property of being.

Etymology

The term ''existence'' comes from Old French ''existence'', from Medieval ...

,

objects

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an ...

and their

properties

Property is the ownership of land, resources, improvements or other tangible objects, or intellectual property.

Property may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Property (mathematics)

Philosophy and science

* Property (philosophy), in philosophy and ...

,

space

Space is the boundless three-dimensional extent in which objects and events have relative position and direction. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions, although modern physicists usually consider ...

and

time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

,

cause and effect

Causality (also referred to as causation, or cause and effect) is influence by which one event, process, state, or object (''a'' ''cause'') contributes to the production of another event, process, state, or object (an ''effect'') where the cau ...

, and

possibility

Possibility is the condition or fact of being possible. Latin origins of the word hint at ability.

Possibility may refer to:

* Probability, the measure of the likelihood that an event will occur

* Epistemic possibility, a topic in philosophy an ...

. Metaphysics is considered one of the four main branches of philosophy, along with

epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

,

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

, and

ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

.

Etymology

The word "metaphysics" derives from the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

words

μετά (''

metá'', "after") and

φυσικά (''physiká'', "physics"). It was first used as the title for several of

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

's works, because they were usually anthologized after the works on

physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

in complete editions. The prefix ''meta-'' ("after") indicates that these works come "after" the chapters on physics. However, Aristotle himself did not call the subject of these books metaphysics: he referred to it as "first philosophy" ( el, πρώτη φιλοσοφία; la, philosophia prima). The editor of Aristotle's works,

Andronicus of Rhodes

Andronicoos of Rhodes ( grc, Ἀνδρόνικος ὁ Ῥόδιος, translit=Andrónikos ho Rhódios; la, Andronicus Rhodius; ) was a Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher from Rhodes who was also the scholarch (head) of the Peripatetic school. He ...

, is thought to have placed the books on first philosophy right after another work, ''Physics'', and called them (''tà metà tà physikà biblía'') or "the books

hat come

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

after the

ooks onphysics".

However, once the name was given, the commentators sought to find other reasons for its appropriateness. For instance,

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

understood it to refer to the chronological or pedagogical order among our philosophical studies, so that the "metaphysical sciences" would mean "those that we study after having mastered the sciences that deal with the physical world".

The term was misread by other medieval commentators, who thought it meant "the science of what is beyond the physical". Following this tradition, the prefix ''meta-'' has more recently been prefixed to the names of sciences to designate higher sciences dealing with ulterior and more fundamental problems: hence

metamathematics

Metamathematics is the study of mathematics itself using mathematical methods. This study produces metatheories, which are mathematical theories about other mathematical theories. Emphasis on metamathematics (and perhaps the creation of the ter ...

,

metaphysiology, etc.

A person who creates or develops metaphysical theories is called a ''metaphysician''.

Common parlance also uses the word ''metaphysics'' for a different referent from that of those already mentioned, namely for beliefs in arbitrary non-physical or

magical entities. For example, "metaphysical healing" to refer to healing by means of remedies that are magical rather than scientific. This usage stemmed from the various historical schools of speculative metaphysics which operated by postulating all manner of physical, mental and spiritual entities as bases for particular metaphysical systems. Metaphysics as a subject does not preclude beliefs in such magical entities but neither does it promote them. Rather, it is the subject which provides the vocabulary and logic with which such beliefs might be analyzed and studied, for example to search for inconsistencies both within themselves and with other accepted systems such as

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

.

Epistemological foundation

Metaphysical study is conducted using

deduction from that which is known ''

a priori

("from the earlier") and ("from the later") are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by their reliance on empirical evidence or experience. knowledge is independent from current ex ...

''. Like

foundational mathematics

Foundations of mathematics is the study of the philosophical and logical and/or algorithmic basis of mathematics, or, in a broader sense, the mathematical investigation of what underlies the philosophical theories concerning the nature of mathe ...

(which is sometimes considered a special case of metaphysics applied to the existence of number), it tries to give a coherent account of the structure of the world, capable of explaining our everyday and scientific perception of the world, and being free from contradictions. In mathematics, there are many different ways to define numbers; similarly, in metaphysics, there are many different ways to define objects, properties, concepts, and other entities that are claimed to make up the world. While metaphysics may, as a special case, study the entities postulated by fundamental science such as atoms and superstrings, its core topic is the set of categories such as object, property and causality which those scientific theories assume. For example: claiming that "electrons have charge" is espousing a scientific theory; while exploring what it means for electrons to be (or at least, to be perceived as) "objects", charge to be a "property", and for both to exist in a topological entity called "space," is the task of metaphysics.

There are two broad stances about what is "the world" studied by metaphysics. According to

metaphysical realism

Philosophical realism is usually not treated as a position of its own but as a stance towards other subject matters. Realism about a certain kind of thing (like numbers or morality) is the thesis that this kind of thing has ''mind-independent exi ...

, the objects studied by metaphysics exist independently of any observer so that the subject is the most fundamental of all sciences.

, on the other hand, assumes that the objects studied by metaphysics exist inside the mind of an observer, so the subject becomes a form of

introspection

Introspection is the examination of one's own conscious thoughts and feelings. In psychology, the process of introspection relies on the observation of one's mental state, while in a spiritual context it may refer to the examination of one's s ...

and

conceptual analysis

Philosophical analysis is any of various techniques, typically used by philosophers in the analytic tradition, in order to "break down" (i.e. analyze) philosophical issues. Arguably the most prominent of these techniques is the analysis of concepts ...

.

This position is of more recent origin. Some philosophers, notably

Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemolo ...

, discuss both of these "worlds" and what can be inferred about each one. Some, such as the

logical positivists

Logical positivism, later called logical empiricism, and both of which together are also known as neopositivism, is a movement in Western philosophy whose central thesis was the verification principle (also known as the verifiability criterion o ...

, and many scientists, reject the metaphysical realism as meaningless and unverifiable. Others reply that this criticism also applies to any type of knowledge, including hard science, which claims to describe anything other than the contents of human perception, and thus that the world of perception ''is'' the objective world in some sense. Metaphysics itself usually assumes that some stance has been taken on these questions and that it may proceed independently of the choice—the question of which stance to take belongs instead to another branch of philosophy,

epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

.

Central questions

Ontology (being)

''Ontology'' is the branch of

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

that studies concepts such as

existence

Existence is the ability of an entity to interact with reality. In philosophy, it refers to the ontology, ontological Property (philosophy), property of being.

Etymology

The term ''existence'' comes from Old French ''existence'', from Medieval ...

,

being

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

,

becoming, and

reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of all that is real or existent within a system, as opposed to that which is only imaginary. The term is also used to refer to the ontological status of things, indicating their existence. In physical terms, r ...

. It includes the questions of how entities are grouped into

basic categories and which of these entities exist on the most fundamental level. Ontology is sometimes referred to as the ''science of being''. It has been characterized as ''general metaphysics'' in contrast to ''special metaphysics'', which is concerned with more particular aspects of being. Ontologists often try to determine what the ''categories'' or ''highest kinds'' are and how they form a ''system of categories'' that provides an encompassing classification of all entities. Commonly proposed categories include

substances,

properties

Property is the ownership of land, resources, improvements or other tangible objects, or intellectual property.

Property may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Property (mathematics)

Philosophy and science

* Property (philosophy), in philosophy and ...

,

relations,

states of affairs In philosophy, a state of affairs (german: Sachverhalt), also known as a situation, is a way the actual world must be in order to make some given ''proposition'' about the actual world true; in other words, a state of affairs is a ''truth-maker'', w ...

and

events

Event may refer to:

Gatherings of people

* Ceremony, an event of ritual significance, performed on a special occasion

* Convention (meeting), a gathering of individuals engaged in some common interest

* Event management, the organization of eve ...

. These categories are characterized by fundamental ontological concepts, like ''particularity'' and ''universality'', ''abstractness'' and ''concreteness'' or ''possibility'' and ''necessity''. Of special interest is the concept of ''ontological dependence'', which determines whether the entities of a category exist on the ''most fundamental level''. Disagreements within ontology are often about whether entities belonging to a certain category exist and, if so, how they are related to other entities.

Identity and change

Identity

Identity may refer to:

* Identity document

* Identity (philosophy)

* Identity (social science)

* Identity (mathematics)

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Identity'' (1987 film), an Iranian film

* ''Identity'' (2003 film), ...

is a fundamental metaphysical concern. Metaphysicians investigating identity are tasked with the question of what, exactly, it means for something to be identical to itself, or – more controversially – to something else. Issues of identity arise in the context of

time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

: what does it mean for something to be itself across two moments in time? How do we account for this? Another question of identity arises when we ask what our criteria ought to be for determining identity, and how the reality of identity interfaces with linguistic expressions.

The metaphysical positions one takes on identity have far-reaching implications on issues such as the

mind–body problem

The mind–body problem is a philosophical debate concerning the relationship between thought and consciousness in the human mind, and the brain as part of the physical body. The debate goes beyond addressing the mere question of how mind and bo ...

,

personal identity

Personal identity is the unique numerical identity of a person over time. Discussions regarding personal identity typically aim to determine the necessary and sufficient conditions under which a person at one time and a person at another time can ...

,

ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

, and

law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

.

A few ancient Greeks took extreme positions on the nature of change.

Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; grc-gre, Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia.

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Elea, from a wealthy and illustrious family. His dates a ...

denied change altogether, while

Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἡράκλειτος , "Glory of Hera"; ) was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Persian Empire.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrote ...

argued that change was ubiquitous: "No man ever steps in the same river twice."

Identity, sometimes called

numerical identity

In philosophy, identity (from , "sameness") is the relation each thing bears only to itself. The notion of identity gives rise to many philosophical problems, including the identity of indiscernibles (if ''x'' and ''y'' share all their propertie ...

, is the relation that a thing bears to itself, and which no thing bears to anything other than itself (cf.

sameness

In philosophy, identity (from , "sameness") is the relation each thing bears only to itself. The notion of identity gives rise to many philosophical problems, including the identity of indiscernibles (if ''x'' and ''y'' share all their propertie ...

).

A modern philosopher who made a lasting impact on the philosophy of identity was

Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathema ...

, whose ''law of the indiscernibility of identicals'' is still widely accepted today. It states that if some object ''x'' is identical to some object ''y'', then any property that ''x'' has, ''y'' will have as well.

Put formally, it states

:

However, it does seem that objects can change over time. Two rival theories to account for the relationship between change and identity are ''

perdurantism

Perdurantism or perdurance theory is a philosophical theory of persistence and identity.[Temporal parts ...](_blank)

'', which treats objects as a series of object-stages, and ''

endurantism

Endurantism or endurance theory is a philosophical theory of persistence and identity. According to the endurantist view, material objects are persisting three-dimensional individuals wholly present at every moment of their existence, which goes ...

'', which maintains that the organism—the same object—is present at every stage in its history.

By appealing to

intrinsic and extrinsic properties

In science and engineering, an intrinsic property is a Property (philosophy), property of a specified subject that exists itself or within the subject. An extrinsic property is not essential or inherent to the subject that is being characteri ...

, endurantism finds a way to harmonize identity with change. Endurantists believe that objects persist by being strictly numerically identical over time.

However, if Leibniz's law of the indiscernibility of identicals is used to define numerical identity here, it seems that objects must be completely unchanged in order to persist. Discriminating between intrinsic properties and extrinsic properties, endurantists state that numerical identity means that, if some object ''x'' is identical to some object ''y'', then any ''intrinsic'' property that ''x'' has, ''y'' will have as well. Thus, if an object persists, ''intrinsic'' properties of it are unchanged, but ''extrinsic'' properties can change over time. Besides the object itself, environments and other objects can change over time; properties that relate to other objects would change even if this object does not change.

Perdurantism can harmonize identity with change in another way. In

four-dimensionalism

In philosophy, four-dimensionalism (also known as the doctrine of temporal parts) is the ontological position that an object's persistence through time is like its extension through space. Thus, an object that exists in time has temporal parts i ...

, a version of perdurantism, what persists is a four-dimensional object which does not change although three-dimensional slices of the object may differ.

Space and time

Objects appear to us in space and time, while abstract entities such as classes, properties, and relations do not. How do space and time serve this function as a ground for objects? Are space and time entities themselves, of some form? Must they exist prior to objects? How exactly can they be defined? How is time related to change; must there always be something changing in order for time to exist?

Causality

Classical philosophy recognized a number of causes, including

teleological

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

final causes. In

special relativity

In physics, the special theory of relativity, or special relativity for short, is a scientific theory regarding the relationship between space and time. In Albert Einstein's original treatment, the theory is based on two postulates:

# The laws o ...

and

quantum field theory

In theoretical physics, quantum field theory (QFT) is a theoretical framework that combines classical field theory, special relativity, and quantum mechanics. QFT is used in particle physics to construct physical models of subatomic particles and ...

the notions of space, time and causality become tangled together, with temporal orders of causations becoming dependent on who is observing them. The laws of physics are symmetrical in time, so could equally well be used to describe time as running backwards. Why then do we perceive it as flowing in one direction, the

arrow of time

The arrow of time, also called time's arrow, is the concept positing the "one-way direction" or " asymmetry" of time. It was developed in 1927 by the British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington, and is an unsolved general physics question. This ...

, and as containing causation flowing in the same direction?

For that matter, can an effect precede its cause? This was the title of a 1954 paper by

Michael Dummett

Sir Michael Anthony Eardley Dummett (27 June 1925 – 27 December 2011) was an English academic described as "among the most significant British philosophers of the last century and a leading campaigner for racial tolerance and equality." He wa ...

, which sparked a discussion that continues today. Earlier, in 1947,

C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Oxford University (Magdalen College, 1925–1954) and Cambridge Univers ...

had argued that one can meaningfully pray concerning the outcome of, e.g., a medical test while recognizing that the outcome is determined by past events: "My free act contributes to the cosmic shape." Likewise, some interpretations of

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, ...

, dating to 1945, involve backward-in-time causal influences.

Causality

Causality (also referred to as causation, or cause and effect) is influence by which one event, process, state, or object (''a'' ''cause'') contributes to the production of another event, process, state, or object (an ''effect'') where the cau ...

is linked by many philosophers to the concept of

counterfactuals

Counterfactual conditionals (also ''subjunctive'' or ''X-marked'') are conditional sentences which discuss what would have been true under different circumstances, e.g. "If Peter believed in ghosts, he would be afraid to be here." Counterfactual ...

. To say that A caused B means that if A had not happened then B would not have happened. This view was advanced by

David Lewis in his 1973 paper "Causation". His subsequent papers further develop his theory of causation.

Causality is usually required as a foundation for

philosophy of science

Philosophy of science is a branch of philosophy concerned with the foundations, methods, and implications of science. The central questions of this study concern what qualifies as science, the reliability of scientific theories, and the ultim ...

if science aims to understand causes and effects and make predictions about them.

Necessity and possibility

Metaphysicians investigate questions about the ways the world could have been.

David Lewis, in ''

On the Plurality of Worlds

''On the Plurality of Worlds'' (1986) is a book by the philosopher David Lewis that defends the thesis of modal realism. "The thesis states that the world we are part of is but one of a plurality of worlds," as he writes in the preface, "an ...

'', endorsed a view called concrete

modal realism

Modal realism is the view propounded by philosopher David Lewis that all possible worlds are real in the same way as is the actual world: they are "of a kind with this world of ours." It is based on the following tenets: possible worlds exist; p ...

, according to which facts about how things could have been are made true by other

concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wi ...

worlds in which things are different. Other philosophers, including

Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathem ...

, have dealt with the idea of possible worlds as well. A necessary fact is true across all

possible world

A possible world is a complete and consistent way the world is or could have been. Possible worlds are widely used as a formal device in logic, philosophy, and linguistics in order to provide a semantics for intensional logic, intensional and mod ...

s. A possible fact is true in some possible world, even if not in the actual world. For example, it is possible that cats could have had two tails, or that any particular apple could have not existed. By contrast, certain propositions seem necessarily true, such as

analytic proposition

Generally speaking, analytic (from el, ἀναλυτικός, ''analytikos'') refers to the "having the ability to analyze" or "division into elements or principles".

Analytic or analytical can also have the following meanings:

Chemistry

* A ...

s, e.g., "All bachelors are unmarried." The view that any

analytic truth

Logical truth is one of the most fundamental concepts in logic. Broadly speaking, a logical truth is a statement which is true regardless of the truth or falsity of its constituent propositions. In other words, a logical truth is a statement whic ...

is necessary is not universally held among philosophers. A less controversial view is that self-identity is necessary, as it seems fundamentally incoherent to claim that any ''x'' is not identical to itself; this is known as the

law of identity

In logic, the law of identity states that each thing is identical with itself. It is the first of the historical three laws of thought, along with the law of noncontradiction, and the law of excluded middle. However, few systems of logic are bui ...

, a putative "first principle". Similarly, Aristotle describes the

principle of non-contradiction

In logic, the law of non-contradiction (LNC) (also known as the law of contradiction, principle of non-contradiction (PNC), or the principle of contradiction) states that contradictory propositions cannot both be true in the same sense at the sa ...

:

:It is impossible that the same quality should both belong and not belong to the same thing ... This is the most certain of all principles ... Wherefore they who demonstrate refer to this as an ultimate opinion. For it is by nature the source of all the other axioms.

Peripheral questions

Metaphysical cosmology and cosmogony

Metaphysical cosmology is the branch of metaphysics that deals with the

world

In its most general sense, the term "world" refers to the totality of entities, to the whole of reality or to everything that is. The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the worl ...

as the totality of all

phenomena

A phenomenon ( : phenomena) is an observable event. The term came into its modern philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be directly observed. Kant was heavily influenced by Gottfried W ...

in

space

Space is the boundless three-dimensional extent in which objects and events have relative position and direction. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions, although modern physicists usually consider ...

and

time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

. Historically, it formed a major part of the subject alongside

ontology

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

, though its role is more peripheral in contemporary philosophy. It has had a broad scope, and in many cases was founded in religion. The ancient Greeks drew no distinction between this use and their model for the cosmos. However, in modern times it addresses questions about the

Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acc ...

which are beyond the scope of the physical sciences. It is distinguished from religious cosmology in that it approaches these questions using philosophical methods (e.g.

dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

s).

Cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony refers to the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used i ...

deals specifically with the origin of the universe. Modern metaphysical cosmology and cosmogony try to address questions such as:

* What is the origin of the Universe? What is its first cause? Is its existence necessary? (see

monism

Monism attributes oneness or singleness (Greek: μόνος) to a concept e.g., existence. Various kinds of monism can be distinguished:

* Priority monism states that all existing things go back to a source that is distinct from them; e.g., i ...

,

pantheism

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ex ...

,

emanationism

Emanationism is an idea in the cosmology or cosmogony of certain religious or philosophical systems. Emanation, from the Latin ''emanare'' meaning "to flow from" or "to pour forth or out of", is the mode by which all things are derived from the ...

and

creationism

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 't ...

)

* What are the ultimate material components of the Universe? (see

mechanism

Mechanism may refer to:

*Mechanism (engineering), rigid bodies connected by joints in order to accomplish a desired force and/or motion transmission

*Mechanism (biology), explaining how a feature is created

*Mechanism (philosophy), a theory that a ...

,

dynamism,

hylomorphism

Hylomorphism (also hylemorphism) is a philosophical theory developed by Aristotle, which conceives every physical entity or being (''ousia'') as a compound of matter (potency) and immaterial form (act), with the generic form as immanently real w ...

,

atomism

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atoms ...

)

* What is the ultimate reason for the existence of the Universe? Does the cosmos have a purpose? (see

teleology

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

)

Mind and matter

Accounting for the existence of

mind

The mind is the set of faculties responsible for all mental phenomena. Often the term is also identified with the phenomena themselves. These faculties include thought, imagination, memory, will, and sensation. They are responsible for various m ...

in a world largely composed of

matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic partic ...

is a metaphysical problem which is so large and important as to have become a specialized subject of study in its own right,

philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addre ...

.

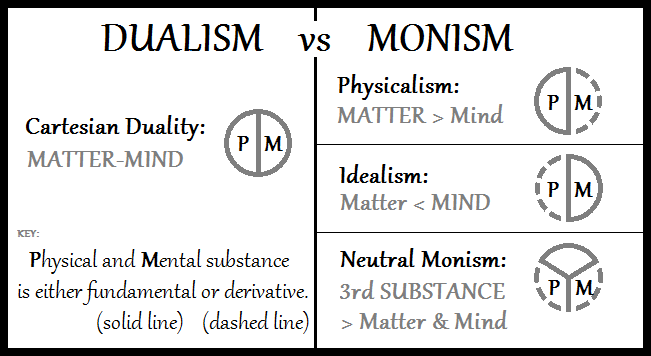

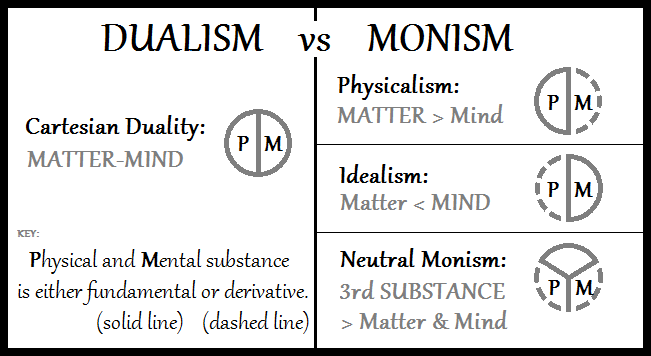

Substance dualism

Substance may refer to:

* Matter, anything that has mass and takes up space

Chemistry

* Chemical substance, a material with a definite chemical composition

* Drug substance

** Substance abuse, drug-related healthcare and social policy diagnosis o ...

is a classical theory in which mind and body are essentially different, with the mind having some of the attributes traditionally assigned to the

soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun ''soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest attes ...

, and which creates an immediate conceptual puzzle about how the two interact. This form of substance dualism differs from the dualism of some eastern philosophical traditions (like Nyāya), which also posit a soul; for the soul, under their view, is ontologically distinct from the mind.

Idealism

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely connected to ide ...

postulates that material objects do not exist unless perceived and only as perceptions. Adherents of

panpsychism

In the philosophy of mind, panpsychism () is the view that the mind or a mindlike aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality. It is also described as a theory that "the mind is a fundamental feature of the world which exists thro ...

, a kind of

property dualism

Property dualism describes a category of positions in the philosophy of mind which hold that, although the world is composed of just one kind of substance— the physical kind—there exist two distinct kinds of properties: physical properties ...

, hold that everything ''has'' a mental aspect, but not that everything exists ''in'' a mind.

Neutral monism

Neutral monism is an umbrella term for a class of metaphysical theories in the philosophy of mind. These theories reject the dichotomy of mind and matter, believing the fundamental nature of reality to be neither mental nor physical; in other words ...

postulates that existence consists of a single substance that in itself is neither mental nor physical, but is capable of mental and physical aspects or attributesthus it implies a

dual-aspect theory. For the last century, the dominant theories have been science-inspired including

materialistic monism,

type identity theory,

token identity theory,

functionalism,

reductive physicalism

In philosophy, physicalism is the metaphysical thesis that "everything is physical", that there is "nothing over and above" the physical, or that everything supervenes on the physical. Physicalism is a form of ontological monism—a "one substa ...

,

nonreductive physicalism

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addre ...

,

eliminative materialism

Eliminative materialism (also called eliminativism) is a materialist position in the philosophy of mind. It is the idea that majority of the mental states in folk psychology do not exist. Some supporters of eliminativism argue that no coheren ...

,

anomalous monism Anomalous monism is a philosophical thesis about the mind–body relationship. It was first proposed by Donald Davidson in his 1970 paper "Mental Events". The theory is twofold and states that mental events are identical with physical events, and ...

,

property dualism

Property dualism describes a category of positions in the philosophy of mind which hold that, although the world is composed of just one kind of substance— the physical kind—there exist two distinct kinds of properties: physical properties ...

,

epiphenomenalism

Epiphenomenalism is a position on the mind–body problem which holds that physical and Biochemistry, biochemical events within the human body (Sensory nervous system, sense organs, Neurotransmission, neural impulses, and muscle contractions, for e ...

and

emergentism

In philosophy, emergentism is the belief in emergence, particularly as it involves consciousness and the philosophy of mind. A property of a system is said to be emergent if it is a new outcome of some other properties of the system and their int ...

.

Determinism and free will

Determinism is the

philosophical

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

proposition

In logic and linguistics, a proposition is the meaning of a declarative sentence. In philosophy, " meaning" is understood to be a non-linguistic entity which is shared by all sentences with the same meaning. Equivalently, a proposition is the no ...

that every event, including human cognition, decision and action, is

causally determined by an unbroken chain of prior occurrences. It holds that nothing happens that has not already been determined. The principal consequence of the deterministic claim is that it poses a challenge to the existence of free will.

The problem of free will is the problem of whether rational agents exercise control over their own actions and decisions. Addressing this problem requires understanding the relation between freedom and causation, and determining whether the laws of nature are causally deterministic. Some philosophers, known as

incompatibilists, view determinism and free will as

mutually exclusive

In logic and probability theory, two events (or propositions) are mutually exclusive or disjoint if they cannot both occur at the same time. A clear example is the set of outcomes of a single coin toss, which can result in either heads or tails ...

. If they believe in determinism, they will therefore believe free will to be an illusion, a position known as ''hard determinism''. Proponents range from

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

to

Ted Honderich

Ted Honderich (born 30 January 1933) is a Canadian-born British professor of philosophy, who was Grote Professor Emeritus of the Philosophy of Mind and Logic, University College London.

Biography

Honderich was born Edgar Dawn Ross Honderich on ...

.

Henri Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopherHenri Bergson. 2014. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 August 2014, from https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/61856/Henri-Bergson defended free will in his dissertation ''

Time and Free Will

''Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness'' (French: ''Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience'') is Henri Bergson's doctoral thesis, first published in 1889. The essay deals with the problem of free will, w ...

'' from 1889.

Others, labeled

compatibilists (or "soft determinists"), believe that the two ideas can be reconciled coherently. Adherents of this view include

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influent ...

and many modern philosophers such as

John Martin Fischer

John Martin Fischer (born December 26, 1952) is an American philosopher. He is Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Riverside and a leading contributor to the philosophy of free will and moral responsibility.

E ...

, Gary Watson,

Harry Frankfurt

Harry Gordon Frankfurt (born May 29, 1929) is an American philosopher. He is professor emeritus of philosophy at Princeton University, where he taught from 1990 until 2002. Frankfurt has also taught at Yale University, Rockefeller University, and ...

, and the like.

Incompatibilists who accept free will but reject determinism are called

libertarians

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and Minarchism, minimize the ...

, a term not to be confused with the political sense.

Robert Kane and

Alvin Plantinga

Alvin Carl Plantinga (born November 15, 1932) is an American analytic philosopher who works primarily in the fields of philosophy of religion, epistemology (particularly on issues involving epistemic justification), and logic.

From 1963 to 1982, ...

are modern defenders of this theory.

Natural and social kinds

The earliest type of classification of social construction traces back to

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

in his dialogue

Phaedrus Phaedrus may refer to:

People

* Phaedrus (Athenian) (c. 444 BC – 393 BC), an Athenian aristocrat depicted in Plato's dialogues

* Phaedrus (fabulist) (c. 15 BC – c. AD 50), a Roman fabulist

* Phaedrus the Epicurean (138 BC – c. 70 BC), an Epic ...

where he claims that the biological classification system seems to carve nature at the joints. In contrast, later philosophers such as

Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault (, ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, writer, political activist, and literary critic. Foucault's theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how ...

and

Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo (; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator, as well as a key figure in Spanish-language and international literature. His best-known bo ...

have challenged the capacity of natural and social classification. In his essay

The Analytical Language of John Wilkins

"The Analytical Language of John Wilkins" (Spanish: "El idioma analítico de John Wilkins") is a short essay by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, first printed in ''La Nación'' on 8 February 1942 and subsequently published in ''Otras Inquisici ...

, Borges makes us imagine a certain encyclopedia where the animals are divided into (a) those that belong to the emperor; (b) embalmed ones; (c) those that are trained; ... and so forth, in order to bring forward the ambiguity of natural and social kinds. According to metaphysics author Alyssa Ney: "The reason all this is interesting is that there seems to be a metaphysical difference between the Borgesian system and Plato's". The difference is not obvious but one classification attempts to carve entities up according to objective distinction while the other does not. According to

Quine this notion is closely related to the notion of similarity. The

philosopher of social science Jason Josephson Storm

Jason Ānanda Josephson Storm (''né'' Josephson) is an American academic, philosopher, social scientist, and author. He is currently Professor and Chair in the Department of Religion and Chair in Science and Technology Studies at Williams Colle ...

has attempted to provide a more precise definition of social kinds, arguing that social kinds may still be

real

Real may refer to:

Currencies

* Brazilian real (R$)

* Central American Republic real

* Mexican real

* Portuguese real

* Spanish real

* Spanish colonial real

Music Albums

* ''Real'' (L'Arc-en-Ciel album) (2000)

* ''Real'' (Bright album) (2010)

...

insofar as they are determined by empricially observable causal processes and that many cases of what appear to be natural kinds — including biological natural kinds and the category of "natural kind" itself — are in fact social kinds; such a view would mitigate the need to prioritize natural kinds above social kinds for much scientific practice.

Number

There are different ways to set up the notion of number in metaphysics theories.

Platonist

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and school of thought, philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western though ...

theories postulate number as a fundamental category itself. Others consider it to be a property of an entity called a "group" comprising other entities; or to be a relation held between several groups of entities, such as "the number four is the set of all sets of four things". Many of the debates around

universals

In metaphysics, a universal is what particular things have in common, namely characteristics or qualities. In other words, universals are repeatable or recurrent entities that can be instantiated or exemplified by many particular things. For exa ...

are applied to the study of number, and are of particular importance due to its status as a foundation for the

philosophy of mathematics

The philosophy of mathematics is the branch of philosophy that studies the assumptions, foundations, and implications of mathematics. It aims to understand the nature and methods of mathematics, and find out the place of mathematics in people's ...

and for

mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

itself.

Applied metaphysics

Although metaphysics as a philosophical enterprise is highly hypothetical, it also has practical application in most other branches of philosophy, science, and now also information technology. Such areas generally assume some basic ontology (such as a system of objects, properties, classes, and space-time) as well as other metaphysical stances on topics such as causality and agency, then build their own particular theories upon these.

In

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

, for example, some theories are based on the ontological assumption of objects with properties (such as electrons having charge) while others may reject objects completely (such as quantum field theories, where spread-out "electronness" becomes property of space-time rather than an object).

"Social" branches of philosophy such as

philosophy of morality

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

,

aesthetics

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed thr ...

and

philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known texts concerning ph ...

(which in turn give rise to practical subjects such as ethics, politics, law, and art) all require metaphysical foundations, which may be considered as branches or applications of metaphysics. For example, they may postulate the existence of basic entities such as value, beauty, and God. Then they use these postulates to make their own arguments about consequences resulting from them. When philosophers in these subjects make their foundations they are doing applied metaphysics, and may draw upon its core topics and methods to guide them, including ontology and other core and peripheral topics. As in science, the foundations chosen will in turn depend on the underlying ontology used, so philosophers in these subjects may have to dig right down to the ontological layer of metaphysics to find what is possible for their theories.

Systems engineering

Systems engineering is an interdisciplinary field of engineering and engineering management that focuses on how to design, integrate, and manage complex systems over their enterprise life cycle, life cycles. At its core, systems engineering util ...

is essentially based on metaphysics, although without acknowledging it. This is because systems-engineering is primarily concerned with identifying what would be of interest in a prospective new system. Investigating the nature of the situation aka

ontology

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

and surveying the possibilities in measuring, evaluating, specifying, planning, implementing, integrating, testing and using it aka

epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Episte ...

.

Relation to other disciplines

Science

Prior to the modern

history of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Meso ...

, scientific questions were addressed as a part of

natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

. Originally, the term "science" ( la, scientia) simply meant "knowledge". The

scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific m ...

, however, transformed natural philosophy into an

empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

activity deriving from

experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into Causality, cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome oc ...

, unlike the rest of philosophy. By the end of the 18th century, it had begun to be called "science" to distinguish it from other branches of philosophy. Science and philosophy have been considered separated disciplines ever since. Thereafter, metaphysics denoted philosophical enquiry of a non-empirical character into the nature of existence.

[Peter Gay, ''The Enlightenment'', vol. 1 (''The Rise of Modern Paganism''), Chapter 3, Section II, pp. 132–141.]

Metaphysics continues asking "why" where science leaves off. For example, any theory of fundamental physics is based on some set of

axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or f ...

s, which may postulate the existence of entities such as atoms, particles, forces, charges, mass, or fields. Stating such postulates is considered to be the "end" of a science theory. Metaphysics takes these postulates and explores what they mean as human concepts. For example, do all theories of physics require the existence of space and time, objects, and properties? Or can they be expressed using only objects, or only properties? Do the objects have to retain their identity over time or can they change? If they change, then are they still the same object? Can theories be reformulated by converting properties or predicates (such as "red") into entities (such as redness or redness fields) or processes ('there is some redding happening over there' appears in some human languages in place of the use of properties). Is the distinction between objects and properties fundamental to the physical world or to our perception of it?

Much recent work has been devoted to analyzing the role of metaphysics in scientific theorizing.

Alexandre Koyré

Alexandre Koyré (, ; born Alexandr Vladimirovich (or Volfovich) Koyra (russian: Александр Владимирович (Вольфович) Койра); 29 August 1892 – 28 April 1964), also anglicized as Alexander Koyre, was a Fren ...

led this movement, declaring in his book ''Metaphysics and Measurement'', "It is not by following experiment, but by outstripping experiment, that the scientific mind makes progress." That metaphysical propositions can influence scientific theorizing is

John Watkins' most lasting contribution to philosophy. Since 1957 "he showed the ways in which some un-testable and hence, according to

Popperian

Sir Karl Raimund Popper (28 July 1902 – 17 September 1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. One of the 20th century's most influential philosophers of science, Popper is known for his rejection of the cl ...

ideas, non-empirical propositions can nevertheless be influential in the development of properly testable and hence scientific theories. These profound results in applied elementary logic...represented an important corrective to positivist teachings about the meaninglessness of metaphysics and of normative claims".

Imre Lakatos

Imre Lakatos (, ; hu, Lakatos Imre ; 9 November 1922 – 2 February 1974) was a Hungarian philosopher of mathematics and science, known for his thesis of the fallibility of mathematics and its "methodology of proofs and refutations" in its pr ...

maintained that all scientific theories have a metaphysical "hard core" essential for the generation of hypotheses and theoretical assumptions. Thus, according to Lakatos, "scientific changes are connected with vast cataclysmic metaphysical revolutions."

An example from biology of Lakatos' thesis:

David Hull has argued that changes in the ontological status of the species concept have been central in the development of biological thought from

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

through

Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in nat ...

,

Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolog ...

, and

Darwin. Darwin's ignorance of metaphysics made it more difficult for him to respond to his critics because he could not readily grasp the ways in which their underlying metaphysical views differed from his own.

In physics, new metaphysical ideas have arisen in connection with

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, ...

, where subatomic particles arguably do not have the same sort of individuality as the particulars with which philosophy has traditionally been concerned. Also, adherence to a deterministic metaphysics in the face of the challenge posed by the quantum-mechanical

uncertainty principle

In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle (also known as Heisenberg's uncertainty principle) is any of a variety of mathematical inequalities asserting a fundamental limit to the accuracy with which the values for certain pairs of physic ...

led physicists such as Albert Einstein to propose

alternative theories that retained determinism.

A.N. Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He is best known as the defining figure of the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which today has found applica ...

is famous for creating a

process philosophy

Process philosophy, also ontology of becoming, or processism, is an approach to philosophy that identifies processes, changes, or shifting relationships as the only true elements of the ordinary, everyday real world. In opposition to the classic ...

metaphysics inspired by electromagnetism and special relativity.

In chemistry,

Gilbert Newton Lewis

Gilbert Newton Lewis (October 23 or October 25, 1875 – March 23, 1946) was an American physical chemist and a Dean of the College of Chemistry at University of California, Berkeley. Lewis was best known for his discovery of the covalent bond a ...

addressed the nature of motion, arguing that an electron should not be said to move when it has none of the properties of motion.

Katherine Hawley notes that the metaphysics even of a widely accepted scientific theory may be challenged if it can be argued that the metaphysical presuppositions of the theory make no contribution to its predictive success.

Theology

There is a relationship between theological doctrines and philosophical reflection in the philosophy of a religion (such as

Christian philosophy

Christian philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Christians, or in relation to the religion of Christianity.

Christian philosophy emerged with the aim of reconciling science and faith, starting from natural rational explanations wit ...

); philosophical reflections are strictly rational. On this way of seeing the two disciplines, if at least one of the premises of an argument is derived from revelation, the argument falls in the domain of theology; otherwise it falls into philosophy's domain.

Rejections of metaphysics

Meta-metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that is concerned with the foundations of metaphysics. A number of individuals have suggested that much or all of metaphysics should be rejected, a meta-metaphysical position known as metaphysical deflationism or ontological deflationism.

In the 16th century,

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

rejected

scholastic metaphysics, and argued strongly for what is now called

empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

, being seen later as the father of modern empirical science. In the 18th century, David Hume took a strong position, arguing that all genuine knowledge involves either mathematics or matters of fact and that metaphysics, which goes beyond these, is worthless. He concluded his ''

Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding'' (1748) with the statement:

If we take in our hand any volume ook

Ook, OoK or OOK may refer to:

* Ook Chung (born 1963), Korean-Canadian writer from Quebec

* On-off keying, in radio technology

* Toksook Bay Airport (IATA code OOK), in Alaska

* Ook!, an esoteric programming language based on Brainfuck

* Ook, th ...

of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, ''Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number?'' No. ''Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence?'' No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.

Thirty-three years after Hume's ''Enquiry'' appeared, Immanuel Kant published his ''

Critique of Pure Reason''. Although he followed Hume in rejecting much of previous metaphysics, he argued that there was still room for some

synthetic Synthetic things are composed of multiple parts, often with the implication that they are artificial. In particular, 'synthetic' may refer to:

Science

* Synthetic chemical or compound, produced by the process of chemical synthesis

* Synthetic o ...

''

a priori

("from the earlier") and ("from the later") are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by their reliance on empirical evidence or experience. knowledge is independent from current ex ...

'' knowledge, concerned with matters of fact yet obtainable independent of experience. These included fundamental structures of space, time, and causality. He also argued for the freedom of the will and the existence of "things in themselves", the ultimate (but unknowable) objects of experience.

Wittgenstein introduced the concept that metaphysics could be influenced by theories of aesthetics, via

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

, vis. a world composed of "atomical facts".

In the 1930s,

A.J. Ayer

Sir Alfred Jules "Freddie" Ayer (; 29 October 1910 – 27 June 1989), usually cited as A. J. Ayer, was an English philosopher known for his promotion of logical positivism, particularly in his books ''Language, Truth, and Logic'' (1936) an ...

and

Rudolf Carnap

Rudolf Carnap (; ; 18 May 1891 – 14 September 1970) was a German-language philosopher who was active in Europe before 1935 and in the United States thereafter. He was a major member of the Vienna Circle and an advocate of logical positivism. He ...

endorsed Hume's position; Carnap quoted the passage above. They argued that metaphysical statements are neither true nor false but meaningless since, according to their

verifiability theory of meaning

Verificationism, also known as the verification principle or the verifiability criterion of meaning, is the philosophical doctrine which maintains that only statements that are empirically verifiable (i.e. verifiable through the senses) are cogniti ...

, a statement is meaningful only if there can be empirical evidence for or against it. Thus, while Ayer rejected the monism of Spinoza, he avoided a commitment to

pluralism

Pluralism denotes a diversity of views or stands rather than a single approach or method.

Pluralism or pluralist may refer to:

Politics and law

* Pluralism (political philosophy), the acknowledgement of a diversity of political systems

* Plur ...

, the contrary position, by holding both views to be without

meaning. Carnap took a similar line with the controversy over the reality of the external world. While the logical positivism movement is now considered dead (with Ayer, a major proponent, admitting in a 1979 TV interview that "nearly all of it was false"),

[Oswald Hanfling, Ch. 5 "Logical positivism", in Stuart G Shanker, ''Philosophy of Science, Logic and Mathematics in the Twentieth Century'' (London: ]Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law, and ...

, 1996), pp

193–194

it has continued to influence philosophy development.

Arguing against such rejections, the Scholastic philosopher

Edward Feser

Edward C. Feser (; born April 16, 1968) is an American Catholic philosopher. He is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Pasadena City College in Pasadena, California.

Education

Feser holds a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Californi ...

held that Hume's critique of metaphysics, and specifically

Hume's fork

Hume's fork, in epistemology, is a tenet elaborating upon British empiricist philosopher David Hume's emphatic, 1730s division between "relations of ideas" versus "matters of fact."Antony Flew, ''A Dictionary of Philosophy'', rev 2nd edn (New York ...

, is "notoriously self-refuting". Feser argues that Hume's fork itself is not a conceptual truth and is not empirically testable.

Some living philosophers, such as

Amie Thomasson

Amie Lynn Thomasson (born July 4, 1968) is an American philosopher, currently Professor of Philosophy at Dartmouth College. Thomasson specializes in metaphysics, philosophy of mind, phenomenology and the philosophy of art. She is the author of '' ...

, have argued that many metaphysical questions can be dissolved just by looking at the way words are used; others, such as

Ted Sider

TED may refer to:

Economics and finance

* TED spread between U.S. Treasuries and Eurodollar

Education

* ''Türk Eğitim Derneği'', the Turkish Education Association

** TED Ankara College Foundation Schools, Turkey

** Transvaal Education Depa ...

, have argued that metaphysical questions are substantive, and that progress can be made toward answering them by comparing theories according to a range of theoretical virtues inspired by the sciences, such as simplicity and explanatory power.

History and schools of metaphysics

Pre-history

Cognitive archeology

Cognitive archaeology is a theoretical perspective in archaeology that focuses on the ancient mind. It is divided into two main groups: evolutionary cognitive archaeology (ECA), which seeks to understand human cognitive evolution from the material ...

such as analysis of cave paintings and other pre-historic art and customs suggests that a form of

perennial philosophy

The perennial philosophy ( la, philosophia perennis), also referred to as perennialism and perennial wisdom, is a perspective in philosophy and spirituality that views all of the world's religious traditions as sharing a single, metaphysical trut ...

or

Shamanic

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritu ...

metaphysics may stretch back to the birth of

behavioral modernity

Behavioral modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits that distinguishes current ''Homo sapiens'' from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterized by ...

, all around the world. Similar beliefs are found in present-day "stone age" cultures such as Australian

aboriginals. Perennial philosophy postulates the existence of a spirit or concept world alongside the day-to-day world, and interactions between these worlds during dreaming and ritual, or on special days or at special places. It has been argued that perennial philosophy formed the basis for

Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at le ...

, with Plato articulating, rather than creating, much older widespread beliefs.

Bronze Age

Bronze Age cultures such as

ancient Mesopotamia

The history of Mesopotamia ranges from the earliest human occupation in the Paleolithic period up to Late antiquity. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing i ...

and

ancient Egypt (along with similarly structured but chronologically later cultures such as

Mayans

The Maya peoples () are an ethnolinguistic group of indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. The ancient Maya civilization was formed by members of this group, and today's Maya are generally descended from people who lived within that historical reg ...

and

Aztecs