In the

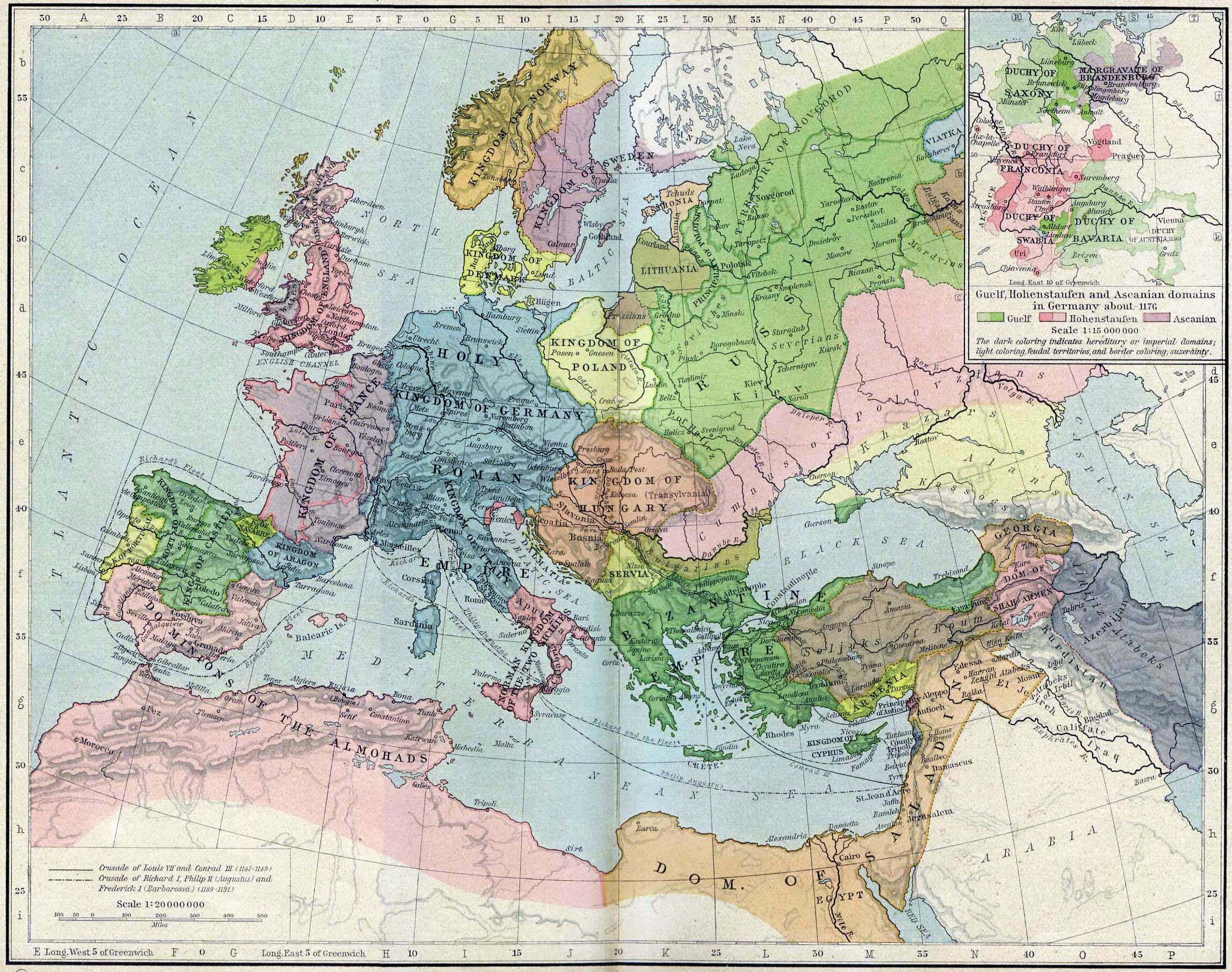

history of Europe

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD 500), the Middle Ages (AD 500 to AD 1500), and the modern era (since AD 1500).

The first early ...

, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the

post-classical period of

global history

World history may refer to:

* Human history, the history of human beings

* History of Earth, the history of planet Earth

* World history (field), a field of historical study that takes a global perspective

* ''World History'' (album), a 1998 albu ...

. It began with the

fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Ancient Rome, Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rul ...

and transitioned into the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

and the

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafarin ...

. The Middle Ages is the middle period of the three traditional divisions of Western history:

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, the medieval period, and the

modern period

The term modern period or modern era (sometimes also called modern history or modern times) is the period of history that succeeds the Middle Ages (which ended approximately 1500 AD). This terminology is a historical periodization that is applie ...

. The medieval period is itself subdivided into the

Early

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Early ...

,

High

High may refer to:

Science and technology

* Height

* High (atmospheric), a high-pressure area

* High (computability), a quality of a Turing degree, in computability theory

* High (tectonics), in geology an area where relative tectonic uplift ...

, and

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the Periodization, period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Eur ...

.

Population decline

A population decline (also sometimes called underpopulation, depopulation, or population collapse) in humans is a reduction in a human population size. Over the long term, stretching from prehistory to the present, Earth's total human population ...

,

counterurbanisation

Counterurbanization, or deurbanization, is a demographic and social process whereby people move from urban areas to rural areas. It is, like suburbanization, inversely related to urbanization. It first occurred as a reaction to inner-city depriva ...

, the collapse of centralized authority, invasions, and mass migrations of

tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English language, English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in p ...

s, which had begun in

late antiquity

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in English ha ...

, continued into the Early Middle Ages. The large-scale movements of the

Migration Period

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

, including various

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

, formed new kingdoms in what remained of the Western Roman Empire. In the 7th century,

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and the Middle East—most recently part of the

Eastern Roman (or Byzantine) Empire—came under the rule of the

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

, an Islamic empire, after conquest by

Muhammad's successors. Although there were substantial changes in society and political structures, the break with classical antiquity was not complete. The still-sizeable Byzantine Empire,

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

's direct continuation, survived in the Eastern Mediterranean and remained a major power. Secular law was advanced greatly by the ''

Code of Justinian

The Code of Justinian ( la, Codex Justinianus, or ) is one part of the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'', the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I, who was Eastern Roman emperor in Constantinople. Two other units, t ...

''. In the West, most kingdoms incorporated extant Roman institutions, while new bishoprics and monasteries were founded as Christianity expanded in Europe. The

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, under the

Carolingian dynasty

The Carolingian dynasty (; known variously as the Carlovingians, Carolingus, Carolings, Karolinger or Karlings) was a Frankish noble family named after Charlemagne, grandson of mayor Charles Martel and a descendant of the Arnulfing and Pippin ...

, briefly established the

Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lom ...

during the later 8th and early 9th centuries. It covered much of Western Europe but later succumbed to the pressures of internal civil wars combined with external invasions:

Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

from the north,

Magyars

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Uralic ...

from the east, and

Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

s from the south.

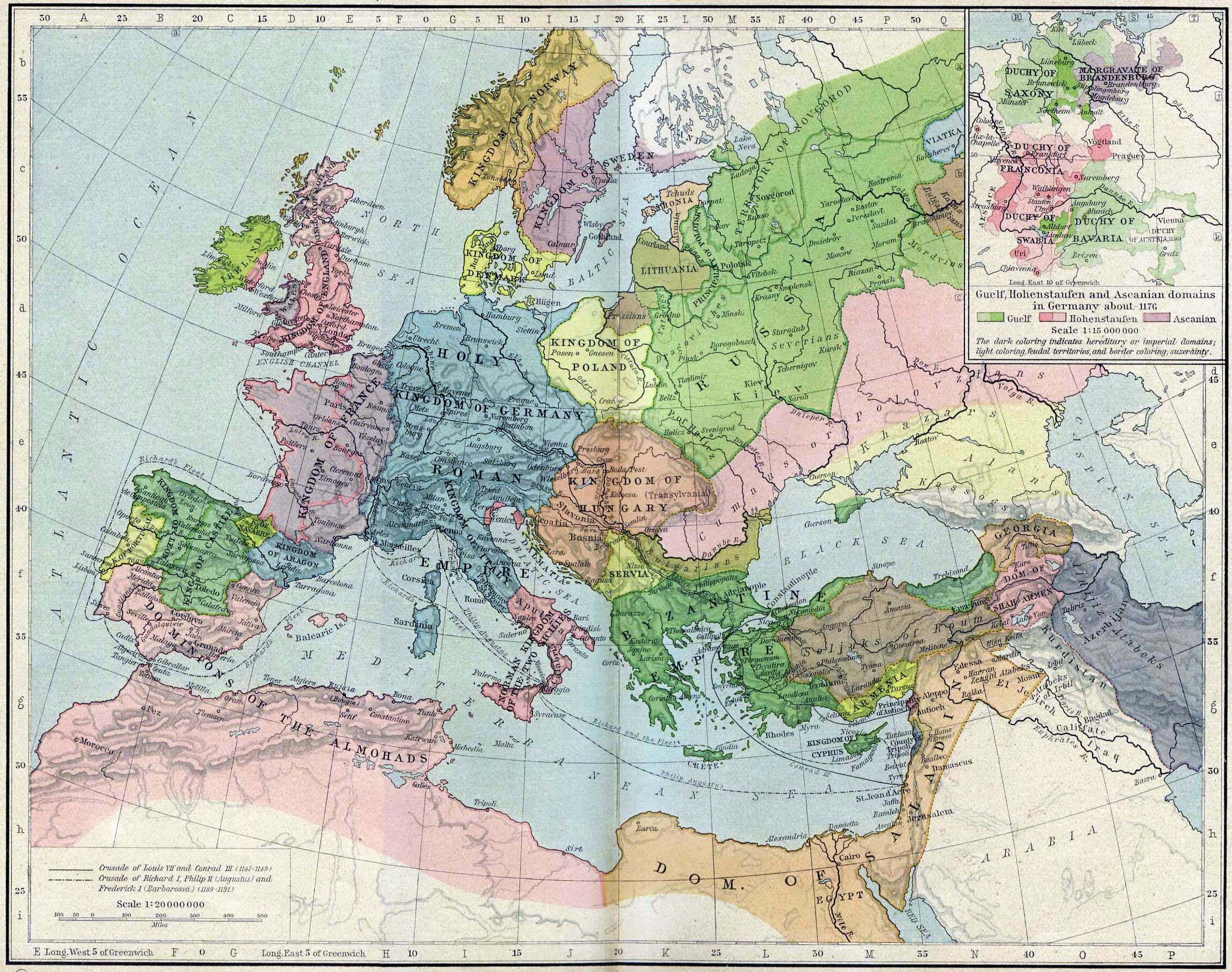

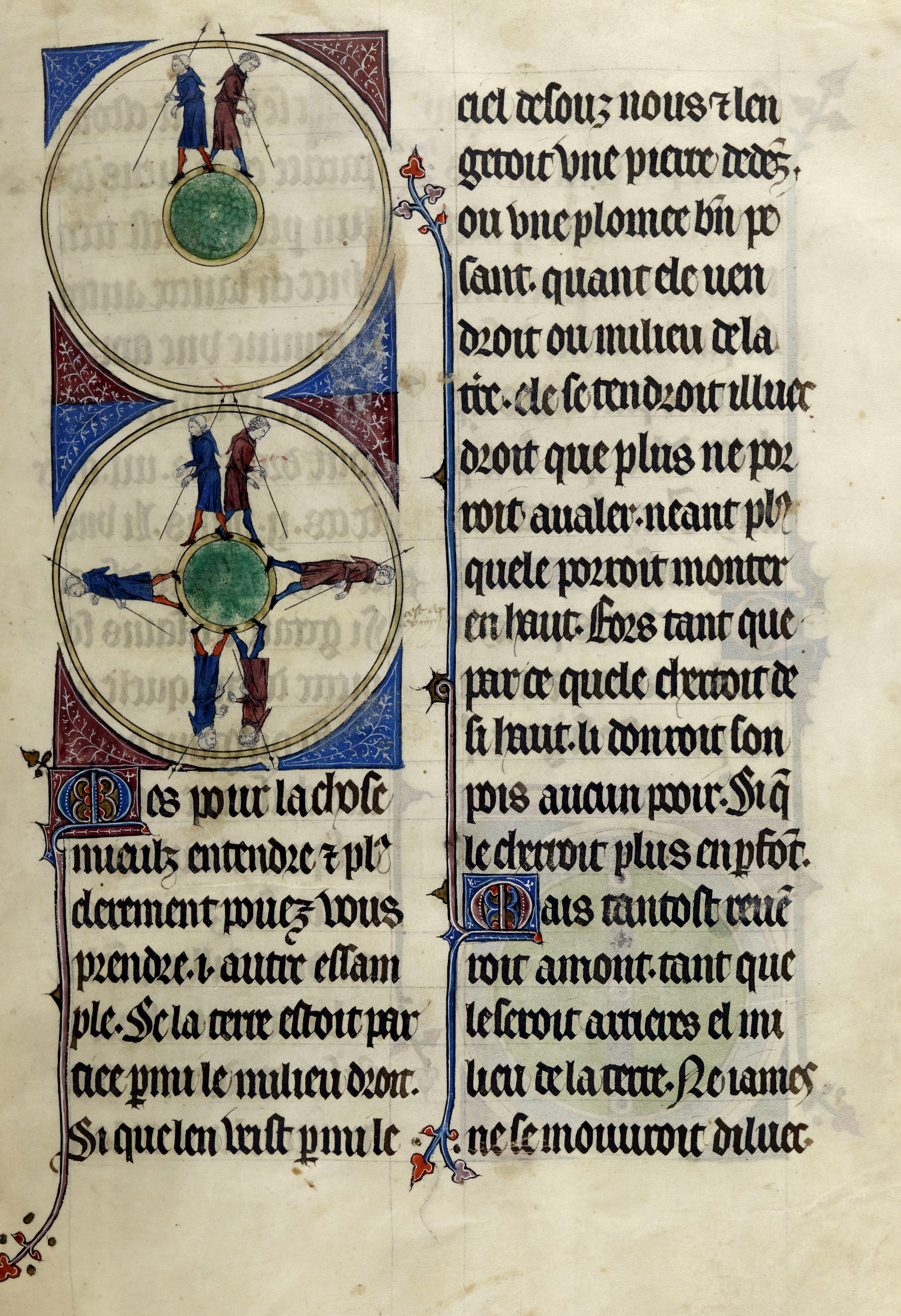

During the High Middle Ages, which began after 1000, the population of Europe increased greatly as technological and

agricultural innovations allowed trade to flourish and the

Medieval Warm Period

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP), also known as the Medieval Climate Optimum or the Medieval Climatic Anomaly, was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region that lasted from to . Proxy (climate), Climate proxy records show peak warmth oc ...

climate change allowed crop yields to increase.

Manorialism

Manorialism, also known as the manor system or manorial system, was the method of land ownership (or "tenure") in parts of Europe, notably France and later England, during the Middle Ages. Its defining features included a large, sometimes forti ...

, the organisation of

peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

s into villages that owed rent and labour services to the

nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

, and

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

, the political structure whereby

knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

s and lower-status nobles owed military service to their

overlord

An overlord in the English feudal system was a lord of a manor who had subinfeudated a particular manor, estate or fee, to a tenant. The tenant thenceforth owed to the overlord one of a variety of services, usually military service or serje ...

s in return for the right to rent from lands and manors, were two of the ways society was organised in the High Middle Ages. This period also saw the formal division of the

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and

Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pag ...

churches, with the

East–West Schism of 1054. The

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

, which began in 1095, were military attempts by Western European Christians to regain control of the

Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

from

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s, and also contributed to the expansion of Latin Christendom in the

Baltic region

The terms Baltic Sea Region, Baltic Rim countries (or simply the Baltic Rim), and the Baltic Sea countries/states refer to slightly different combinations of countries in the general area surrounding the Baltic Sea, mainly in Northern Europe. ...

and the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

. Kings became the heads of centralised

nation states

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may in ...

, reducing crime and violence but making the ideal of a unified

Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

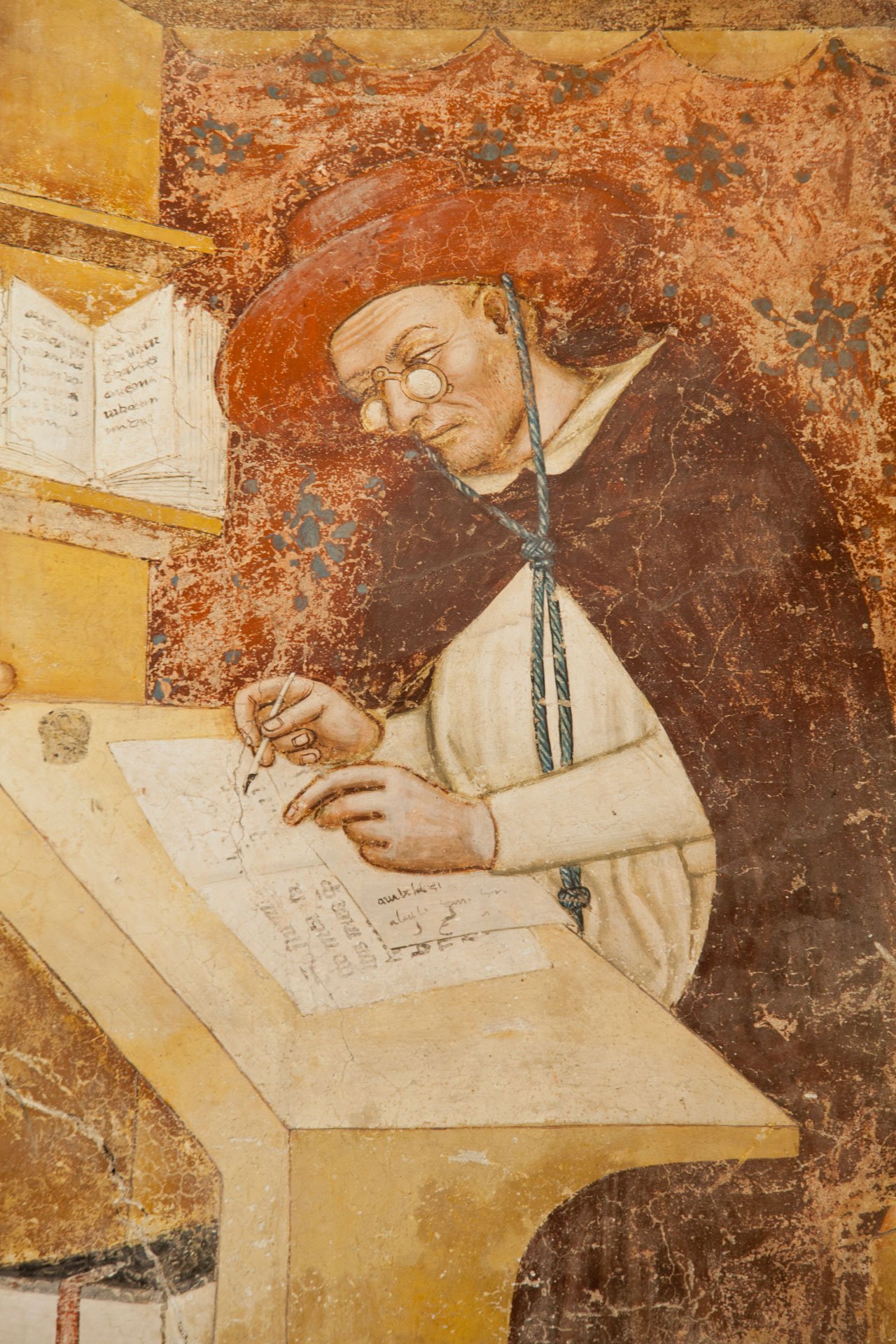

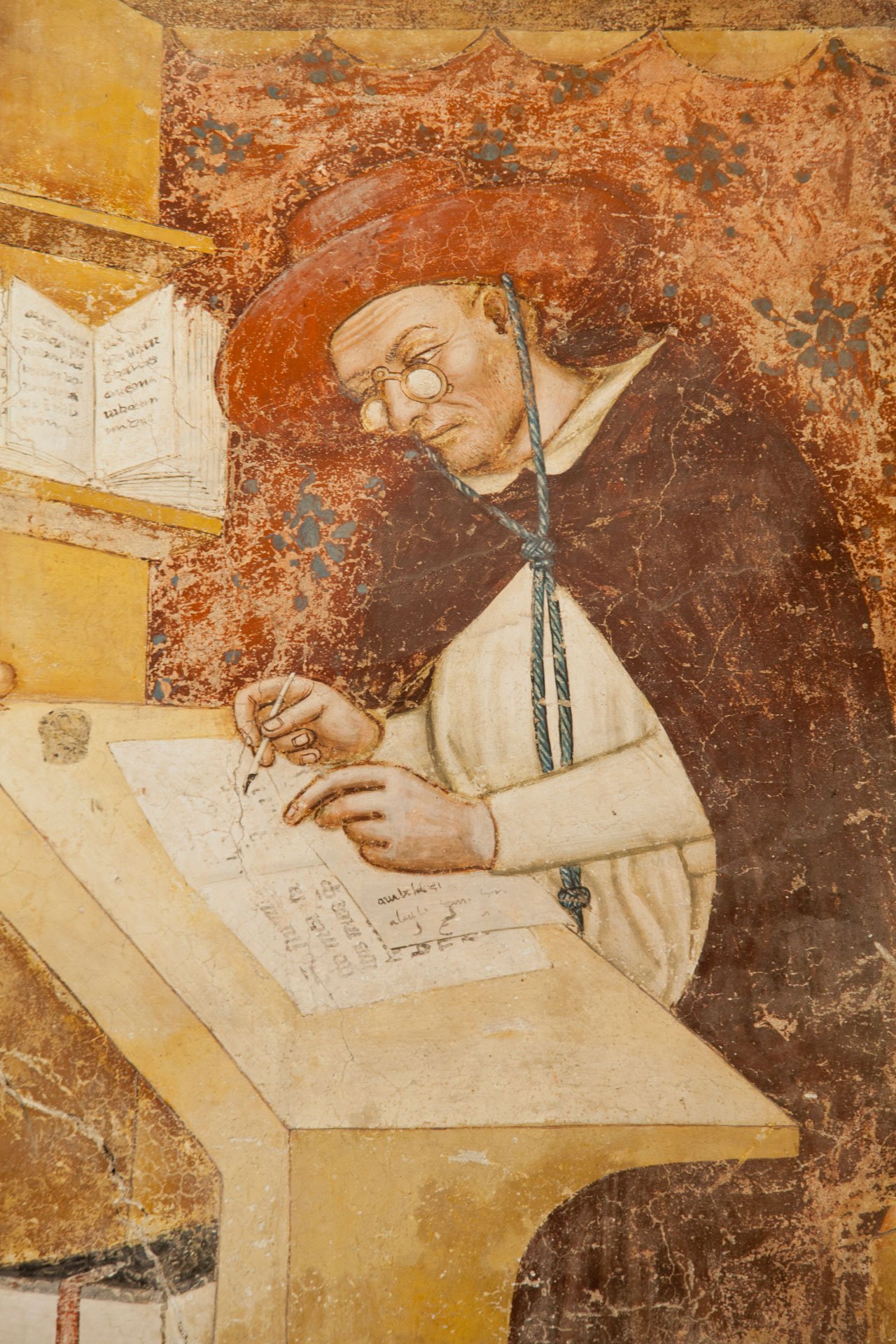

more distant. In the West, intellectual life was marked by

scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

, a philosophy that emphasised joining faith to reason, and by the founding of

universities

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, t ...

. The theology of

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

, the paintings of

Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto ( , ) and Latinised as Giottus, was an Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the Gothic/Proto-Renaissance period. Giot ...

, the poetry of

Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: '' ...

and

Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

, the travels of

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

, and the

Gothic architecture

Gothic architecture (or pointed architecture) is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It e ...

of cathedrals such as

Chartres

Chartres () is the prefecture of the Eure-et-Loir department in the Centre-Val de Loire region in France. It is located about southwest of Paris. At the 2019 census, there were 170,763 inhabitants in the metropolitan area of Chartres (as d ...

mark the end of this period.

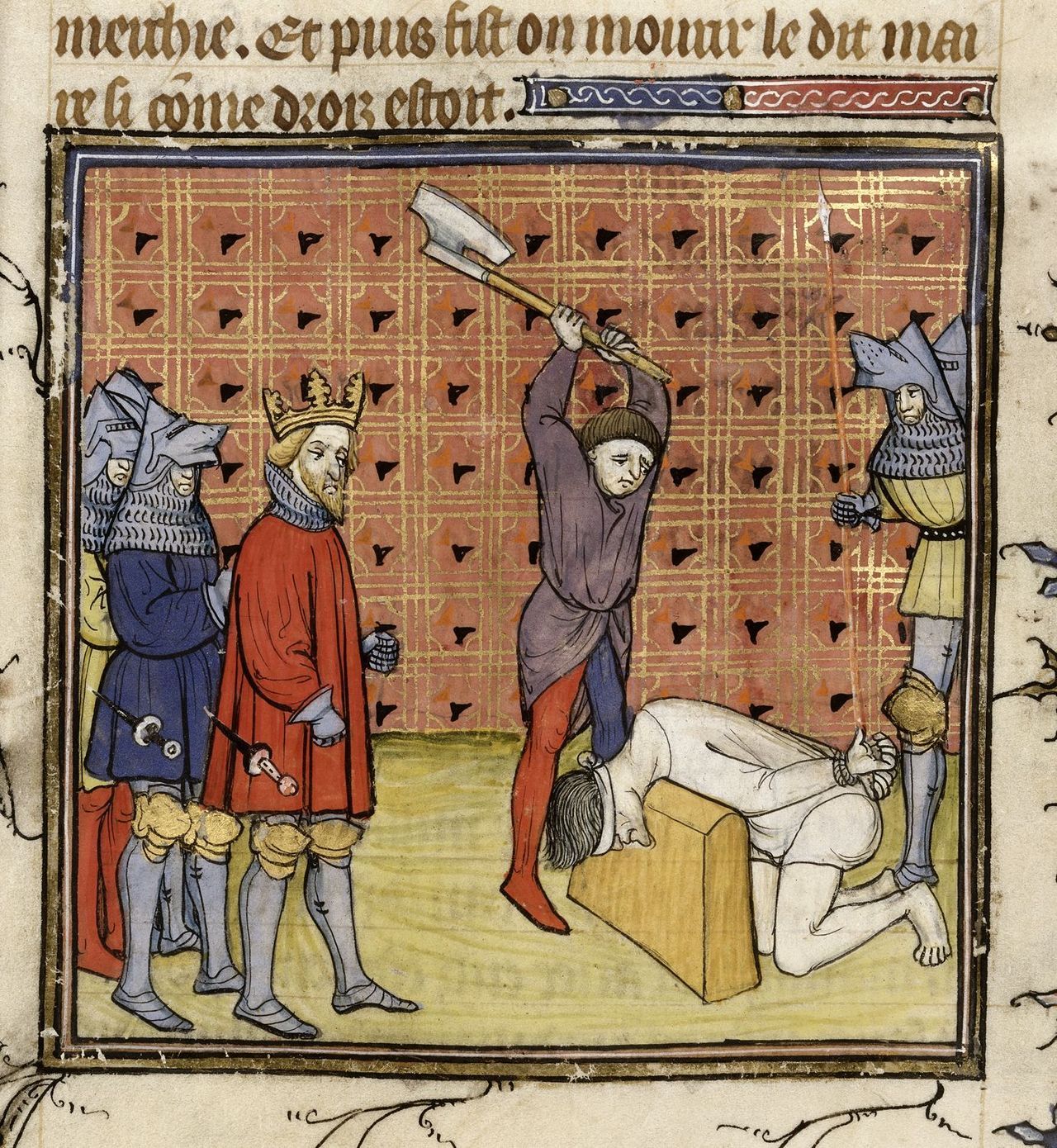

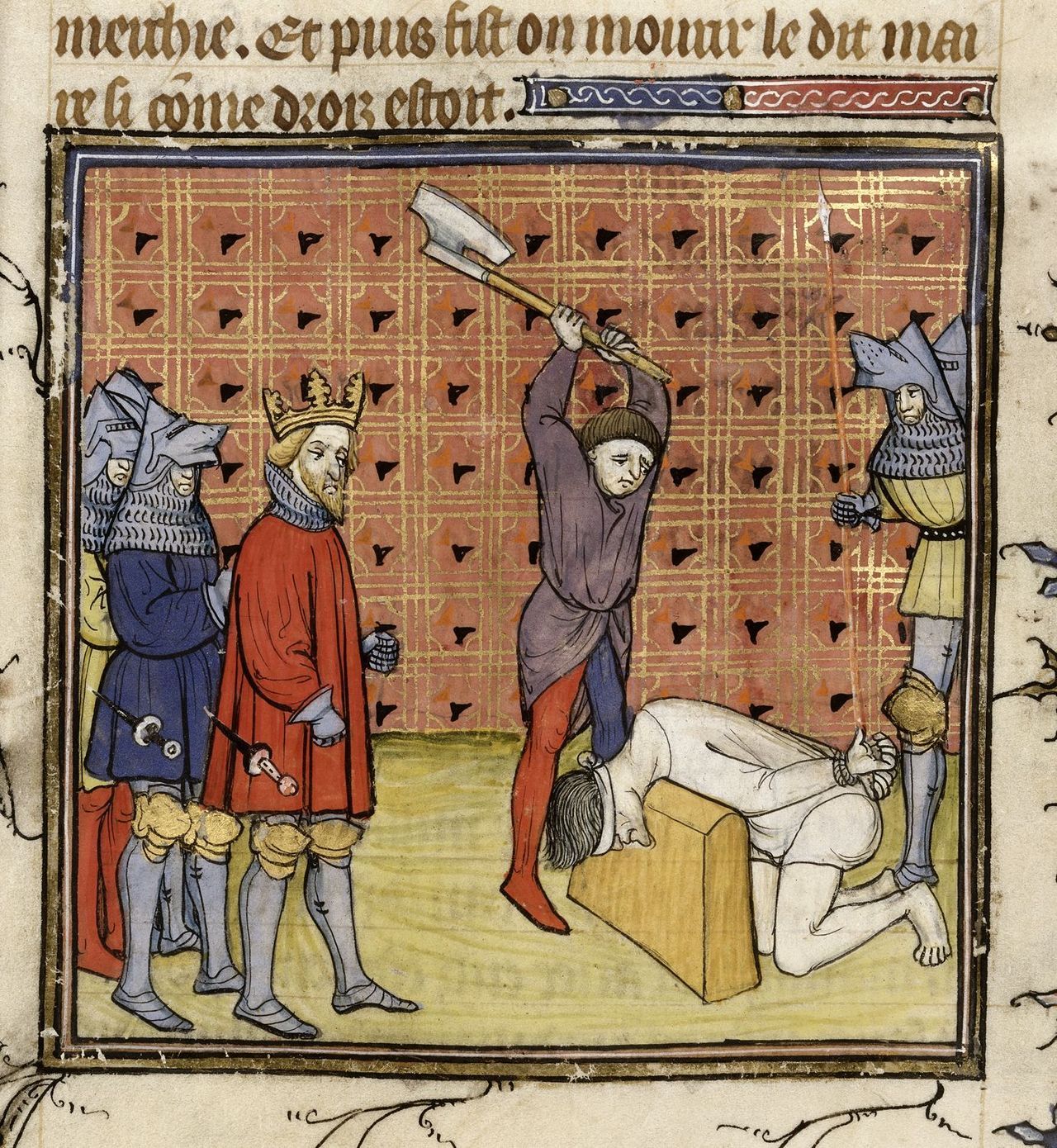

The Late Middle Ages was marked by difficulties and calamities including famine, plague, and war, which significantly diminished the population of Europe; between 1347 and 1350, the

Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

killed about a third of Europeans. Controversy,

heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

, and the

Western Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Vatican Standoff, the Great Occidental Schism, or the Schism of 1378 (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon bo ...

within the Catholic Church paralleled the interstate conflict, civil strife, and

peasant revolts

This is a chronological list of conflicts in which peasants played a significant role.

Background

The history of peasant wars spans over two thousand years. A variety of factors fueled the emergence of the peasant revolt phenomenon, including:

...

that occurred in the kingdoms. Cultural and technological developments transformed European society, concluding the Late Middle Ages and beginning the

early modern period.

Terminology and periodisation

The Middle Ages is one of the three major periods in the most enduring scheme for analysing

European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD 500), the Middle Ages (AD 500 to AD 1500), and the modern era (since AD 1500).

The first early ...

:

Antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

, the Middle Ages and the

Modern Period

The term modern period or modern era (sometimes also called modern history or modern times) is the period of history that succeeds the Middle Ages (which ended approximately 1500 AD). This terminology is a historical periodization that is applie ...

.

[Power ''Central Middle Ages'' p. 3] A similar term first appears in Latin in 1469 as or "middle season". In early usage, there were many variants, including , or "middle age", first recorded in 1604, and , or "middle centuries", first recorded in 1625.

[Murray "Should the Middle Ages Be Abolished?" ''Essays in Medieval Studies'' p. 4] The adjective "medieval" (or sometimes "mediaeval"

[Flexner (ed.) ''Random House Dictionary'' p. 1194] or "mediæval"), meaning pertaining to the Middle Ages, derives from .

[

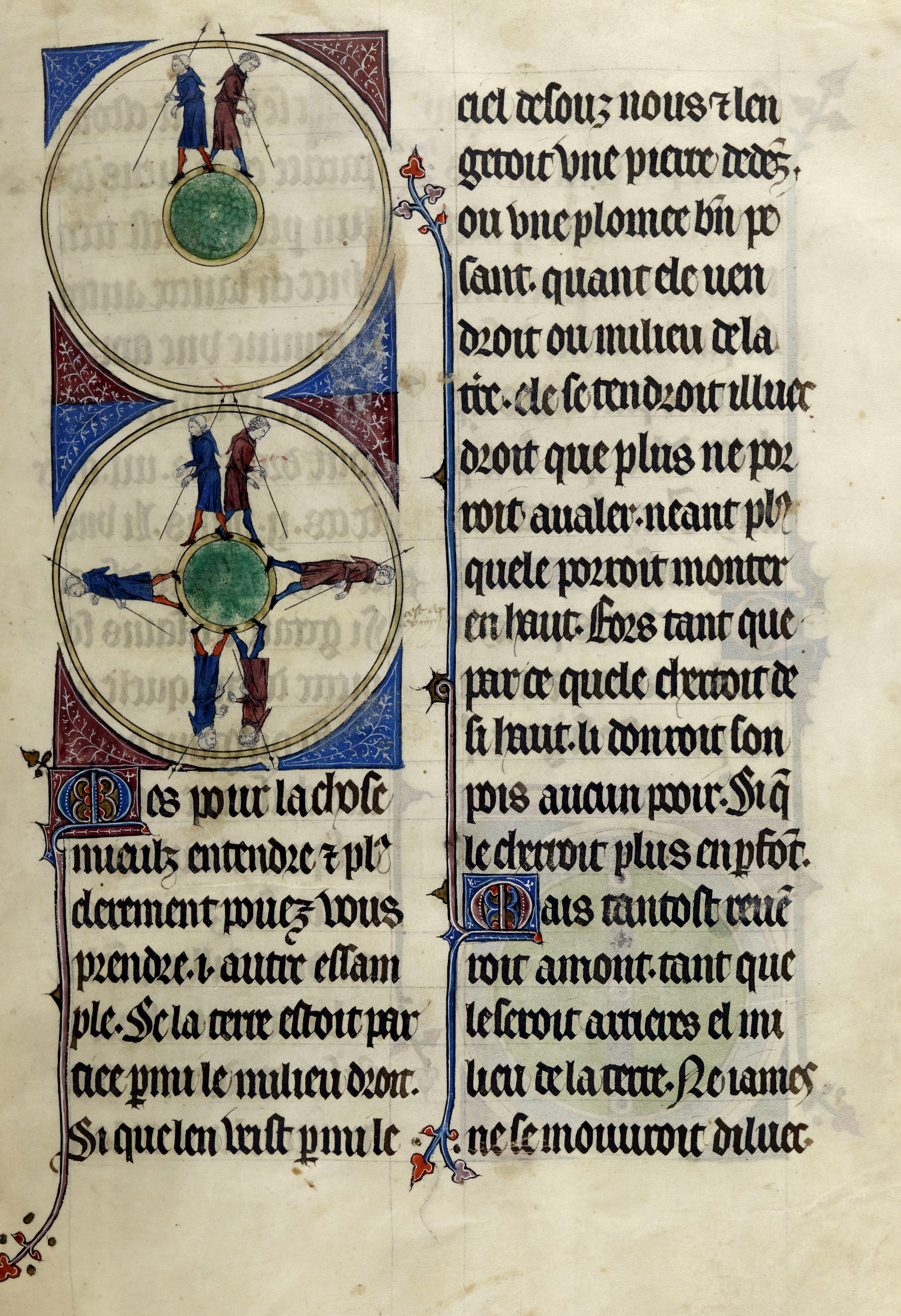

Medieval writers divided history into periods such as the "]Six Ages

The Six Ages of the World (Latin: ''sex aetates mundi''), also rarely Seven Ages of the World (Latin: ''septem aetates mundi''), is a Christian historical periodization first written about by Augustine of Hippo ''circa'' AD 400.

It is bas ...

" or the "Four Empires

The four kingdoms of Daniel are four kingdoms which, according to the Book of Daniel, precede the " end-times" and the "Kingdom of God".

The four kingdoms

Historical background

The Book of Daniel originated from a collection of legends cir ...

", and considered their time to be the last before the end of the world. The concept of living in a "middle age" was alien to them, and they referred to themselves as "", or "we modern people". In their concept, their age began when Christ had brought light to mankind, and contrasted the light of their age with the spiritual darkness of previous periods. The Italian humanist and poet Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited w ...

(d. 1374) was the first to revise the metaphor. He was convinced that a period of decline had begun when emperors of non-Italian origin assumed power in the Roman Empire, and described it as an age of "darkness". His concept was further developed by humanists like Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was somet ...

(d. 1375) and Filippo Villani

Filippo Villani (fl. end of the 14th and the beginning of the 15th century) was a chronicler of Florence. Son of the chronicler Matteo Villani, he extended the original '' Nuova Cronica'' of his uncle Giovanni Villani down to 1364.

Career

Filipp ...

who emphasized the "rebirth" of culture in their age after a long period of cultural darkness. Leonardo Bruni

Leonardo Bruni (or Leonardo Aretino; c. 1370 – March 9, 1444) was an Italian humanist, historian and statesman, often recognized as the most important humanist historian of the early Renaissance. He has been called the first modern historian. H ...

was the first historian to use tripartite periodisation

In historiography, periodization is the process or study of categorizing the past into discrete, quantified, and named blocks of time for the purpose of study or analysis.Adam Rabinowitz. It's about time: historical periodization and Linked Ancie ...

in his ''History of the Florentine People'' (1442), with a middle period "between the fall of the Roman Empire and the revival of city life sometime in late eleventh and twelfth centuries".[Hankins ''Introduction to History of the Florentine people by Leonardo Bruni'' pp. xvii–xviii] Tripartite periodisation became standard after the 17th-century German historian Christoph Cellarius

Christoph (Keller) Cellarius (22 November 1638 – 4 June 1707) was a German classical scholar from Schmalkalden who held positions in Weimar and Halle. Although the Ancient-Medieval-Modern division of history was used earlier by Italian Rena ...

divided history into three periods: ancient, medieval, and modern.[

The most commonly given starting point for the Middle Ages is around 500, with the date of 476—the year the last Western Roman Emperor was deposed—first used by Bruni.][ Later starting dates are sometimes used in the outer parts of Europe. For Europe as a whole, 1500 is often considered to be the end of the Middle Ages, but there is no universally agreed upon end date. Depending on the context, events such as the ]conquest of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

by the Turks in 1453, Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

's first voyage to the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

in 1492, or the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

in 1517 are sometimes used.[ English historians often use the ]Battle of Bosworth Field

The Battle of Bosworth or Bosworth Field was the last significant battle of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the houses of Lancaster and York that extended across England in the latter half of the 15th century. Fought on 22 Augu ...

in 1485 to mark the end of the period. For Spain, dates commonly used are the death of King Ferdinand II in 1516, the death of Queen Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la Católica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as List of Aragonese royal consorts, Queen consort ...

in 1504, or the conquest of Granada

The Granada War ( es, Guerra de Granada) was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1491 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It e ...

in 1492.

Historians from Romance-speaking

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language fam ...

countries tend to divide the Middle Ages into two parts: an earlier "High" and later "Low" period. English-speaking historians, following their German counterparts, generally subdivide the Middle Ages into three intervals: "Early", "High", and "Late".[ In the 19th century, the entire Middle Ages were often referred to as the " Dark Ages", but with the adoption of these subdivisions, use of this term was restricted to the Early Middle Ages in the early 20th century.][Mommsen "Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages'" ''Speculum'' p. 226]

Later Roman Empire

The Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

reached its greatest territorial extent during the 2nd century AD; the following two centuries witnessed the slow decline of Roman control over its outlying territories. Runaway inflation, external pressure on the frontiers, and outbreaks of plague combined to create the Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis (AD 235–284), was a period in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed. The crisis ended due to the military victories of Aurelian and with the ascensi ...

, with emperors coming to the throne only to be rapidly replaced by new usurpers. Military expenses increased steadily during the 3rd century, mainly in response to the war with the newly established Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

.[Heather ''Fall of the Roman Empire'' p. 111] The army doubled in size, and cavalry and smaller units replaced the Roman legion

The Roman legion ( la, legiō, ) was the largest military unit of the Roman army, composed of 5,200 infantry and 300 equites (cavalry) in the period of the Roman Republic (509 BC–27 BC) and of 5,600 infantry and 200 auxilia in the period of ...

as the main tactical unit.[Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' pp. 24–25] The need for revenue led to increased taxes and a decline in numbers of the curial, or landowning, class, and decreasing numbers of them willing to shoulder the burdens of holding office in their native towns.[ More bureaucrats were needed in the central administration to deal with the needs of the army, which led to complaints from civilians that there were more tax-collectors in the empire than tax-payers.][

The Emperor ]Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

(r. 284–305) split the empire into separately administered eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and western halves in 286. This system, which eventually encompassed two senior

Senior (shortened as Sr.) means "the elder" in Latin and is often used as a suffix for the elder of two or more people in the same family with the same given name, usually a parent or grandparent. It may also refer to:

* Senior (name), a surname ...

and two junior co-emperors (hence known as the Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the '' augusti'', and their juniors colleagues and designated successors, the '' caesares' ...

) stabilised the imperial government for about two decades. Diocletian's further reforms strengthened the governmental bureaucracy, reformed taxation, and strengthened the army, which bought the empire time but did not resolve the problems it was facing: excessive taxation, a declining birthrate, and pressures on its frontiers, among others. In 330, after a period of civil war, Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

(r. 306–337) refounded the city of Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

as the newly renamed eastern capital, Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. For much of the 4th century, Roman society stabilised in a new form that differed from the earlier classical period, with a widening gulf between the rich and poor, and a decline in the vitality of the smaller towns. Another change was the Christianisation

Christianization (American and British English spelling differences#-ise.2C -ize .28-isation.2C -ization.29, or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of ...

, or conversion of the empire to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

. The process was stimulated by the 3rd-century crisis, accelerated by the conversion of Constantine the Great, and by the end of the century Christianity emerged as the empire's dominant religion. Debates about Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. Such study concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theology, theologian ...

, customs and ethics intensified. Mainstream Christianity developed under imperial patronage, and those who persisted with theological views condemned at the Church leaders' general assemblies known as ecumenical councils

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote ar ...

had to endure official persecution. Heretic views could survive by popular support, or through intensive proselytizing activities. Examples include the uncompromisingly Monophysite

Monophysitism ( or ) or monophysism () is a Christological term derived from the Greek (, "alone, solitary") and (, a word that has many meanings but in this context means "nature"). It is defined as "a doctrine that in the person of the incarn ...

Syrians and Egyptians, and the spread of Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

among the Germanic peoples. Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

remained a tolerated religion although legislation limited the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

' rights, hindering conversion of Christians to Judaism.

Civil war between rival emperors became common in the middle of the 4th century, diverting soldiers from the empire's frontier forces and allowing invaders

''InVader'' is the fourth album by Finnish glam metal band Reckless Love, released on 4 March 2016 through Spinefarm Records.

Track listing

All songs written by Olli Herman, Pepe Reckless, and Ikka Wirtanen, unless otherwise noted.

Reception

Wr ...

to encroach. Although the movements of peoples during this period are usually described as "invasions", they were not just military expeditions but migrations of entire peoples into the empire.[Brown, ''World of Late Antiquity'', pp. 122–124] In 376, the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

, fleeing from the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

, received permission from Emperor Valens

Valens ( grc-gre, Ουάλης, Ouálēs; 328 – 9 August 378) was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of ...

(r. 364–378) to settle in Roman territory in the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

. The settlement did not go smoothly, and when Roman officials mishandled the situation, the Goths began to raid and plunder. Valens, attempting to put down the disorder, was killed fighting the Goths at the Battle of Adrianople

The Battle of Adrianople (9 August 378), sometimes known as the Battle of Hadrianopolis, was fought between an Eastern Roman army led by the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens and Gothic rebels (largely Thervings as well as Greutungs, non-Gothic Ala ...

on 9 August 378. In 401, the Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

, a Gothic group, invaded the Western Roman Empire and, although briefly forced back from Italy, in 410 sacked the city of Rome. In 406 the Alans

The Alans (Latin: ''Alani'') were an ancient and medieval Iranian nomadic pastoral people of the North Caucasus – generally regarded as part of the Sarmatians, and possibly related to the Massagetae. Modern historians have connected the Al ...

, Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, and Suevi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own names ...

crossed into Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

; over the next three years they spread across Gaul and in 409 crossed the Pyrenees Mountains

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to C ...

into modern-day Spain. The Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, Alemanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pres ...

, and the Burgundians

The Burgundians ( la, Burgundes, Burgundiōnes, Burgundī; on, Burgundar; ang, Burgendas; grc-gre, Βούργουνδοι) were an early Germanic tribe or group of tribes. They appeared in the middle Rhine region, near the Roman Empire, and ...

all ended up in Gaul while the Angles

The Angles ( ang, Ængle, ; la, Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who settled in Great Britain in the post-Roman period. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England. Their name is the root of the name ' ...

, Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

, and Jutes

The Jutes (), Iuti, or Iutæ ( da, Jyder, non, Jótar, ang, Ēotas) were one of the Germanic tribes who settled in Great Britain after the departure of the Romans. According to Bede, they were one of the three most powerful Germanic nations ...

settled in Britain,[Cunliffe ''Europe Between the Oceans'' p. 417] and the Vandals went on to cross the strait of Gibraltar after which they conquered the province of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. The Hunnic king Attila

Attila (, ; ), frequently called Attila the Hun, was the ruler of the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European traditio ...

(r. 434–453) led invasions into the Balkans in 442 and 447, Gaul in 451, and Italy in 452. The Hunnic threat remained until Attila's death in 453, when the Hunnic confederation he led fell apart.

When dealing with the migrations, the eastern and western elites applied different methods. The Eastern Romans combined the deployment of armed forces with gifts and grants of offices to the tribal leaders. The Western aristocrats failed to support the army but refused to pay tribute to prevent invasions by the tribes.[ These invasions completely changed the political and demographic nature of the western section of the empire.][ By the end of the 5th century it was divided into smaller political units, ruled by the tribes that had invaded in the early part of the century. The emperors of the 5th century were often controlled by military strongmen such as ]Stilicho

Flavius Stilicho (; c. 359 – 22 August 408) was a military commander in the Roman army who, for a time, became the most powerful man in the Western Roman Empire. He was of Vandal origins and married to Serena, the niece of emperor Theodosius ...

(d. 408), Aetius (d. 454), Aspar

Flavius Ardabur Aspar (Greek: Άσπαρ, fl. 400471) was an Eastern Roman patrician and ''magister militum'' ("master of soldiers") of Alanic-Gothic descent. As the general of a Germanic army in Roman service, Aspar exerted great influence on ...

(d. 471), Ricimer

Flavius Ricimer ( , ; – 18/19 August 472) was a Romanized Germanic general who effectively ruled the remaining territory of the Western Roman Empire from 461 until his death in 472, with a brief interlude in which he contested power with An ...

(d. 472), or Gundobad

Gundobad ( la, Flavius Gundobadus; french: Gondebaud, Gondovald; 452 – 516 AD) was King of Burgundy, King of the Burgundians (473 – 516), succeeding his father Gundioc of Burgundy. Previous to this, he had been a Patrician (ancient Rome), ...

(d. 516), who were partly or fully of non-Roman ancestry. The deposition of the last emperor of the west, Romulus Augustulus

Romulus Augustus ( 465 – after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne by his father, the ''magister militum'' Orestes, and, at that time, ...

, in 476 has traditionally marked the end of the Western Roman Empire.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' p. 86] The Eastern Roman Empire, often referred to as the Byzantine Empire after the fall of its western counterpart, had little ability to assert control over the lost western territories. The Byzantine emperors

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

maintained a claim over the territory, but while none of the new kings in the west dared to elevate himself to the position of emperor of the west, Byzantine control of most of the Western Empire could not be sustained.

Early Middle Ages

New realms

In the post-Roman world ethnic identities were flexible, often determined by loyalty to a successful military leader or by religion instead of ancestry or language. Ethnic markers quickly changed—by around 500, Arianism, originally a genuine Roman heresy, was associated with Germanic peoples, and the Goths rarely used their Germanic language outside their churches. The fusion of Roman culture with the customs of the invading tribes is well documented. Popular assemblies that allowed free male tribal members more say in political matters than had been common in the Roman state developed into legislative and judicial bodies.

In the post-Roman world ethnic identities were flexible, often determined by loyalty to a successful military leader or by religion instead of ancestry or language. Ethnic markers quickly changed—by around 500, Arianism, originally a genuine Roman heresy, was associated with Germanic peoples, and the Goths rarely used their Germanic language outside their churches. The fusion of Roman culture with the customs of the invading tribes is well documented. Popular assemblies that allowed free male tribal members more say in political matters than had been common in the Roman state developed into legislative and judicial bodies.[Wickham, ''Inheritance of Rome'', pp. 98–101] Material artefacts left by the Romans and the invaders are often similar, and tribal items were often modelled on Roman objects.[Collins, ''Early Medieval Europe'', p. 100] Much of the scholarly and written culture of the new kingdoms was also based on Roman intellectual traditions.[Collins, ''Early Medieval Europe'', pp. 96–97] An important difference was the gradual loss of tax revenue by the new polities. Many of the new political entities no longer supported their armies through taxes, instead relying on granting them land or rents. This meant there was less need for large tax revenues and so the taxation systems decayed.[Wickham, ''Inheritance of Rome'', pp. 102–103]

Among the new peoples filling the political void left by Roman centralised government, the first Germanic groups now collectively known as

Among the new peoples filling the political void left by Roman centralised government, the first Germanic groups now collectively known as Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

settled in Britain before the middle of the 5th century. The local culture had little impact on their way of life, but the linguistic assimilation of masses of the local Celtic Britons

The Britons ( *''Pritanī'', la, Britanni), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were people of Celtic language and culture who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age and into the Middle Ages, at which point th ...

to the newcomers is evident. By around 600, new political centres emerged, some local leaders accumulated considerable wealth, and a number of small kingdoms were formed. From among these realms, the kingdoms of Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

, Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ye ...

, Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

, and East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

emerged as dominant powers by the end of the 7th century. Smaller kingdoms in present-day Wales and Scotland were still under the control of the native Britons and Picts

The Picts were a group of peoples who lived in what is now northern and eastern Scotland (north of the Firth of Forth) during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and what their culture was like can be inferred from ea ...

.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 156–159] Ireland was divided into even smaller political units, usually known as tribal kingdoms, under the control of kings. There were perhaps as many as 150 local kings in Ireland, of varying importance.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 164–165]

The Ostrogoths

The Ostrogoths ( la, Ostrogothi, Austrogothi) were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the larg ...

, a Gothic tribe moved to Italy from the Balkans in the late 5th century under Theoderic the Great

Theodoric (or Theoderic) the Great (454 – 30 August 526), also called Theodoric the Amal ( got, , *Þiudareiks; Greek: , romanized: ; Latin: ), was king of the Ostrogoths (471–526), and ruler of the independent Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy b ...

(r. 493–526). He set up a kingdom

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

marked by its co-operation between the Italians and the Ostrogoths, at least until the last years of his reign. Power struggles between Romanized and traditionalist Ostrogothic groups followed his death, providing the opportunity for the Byzantines to reconquer Italy in the middle of 6th century.[James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 82–94] The Burgundians settled in Gaul, and after an earlier realm was destroyed by the Huns in 436, formed a new kingdom in the 440s. Between today's Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

and Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of t ...

, it grew to become the realm of Burgundy

Burgundy (; french: link=no, Bourgogne ) is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. The c ...

in the late 5th and early 6th centuries.[James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 77–78] Elsewhere in Gaul, the Franks and Celtic Britons

The Britons ( *''Pritanī'', la, Britanni), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were people of Celtic language and culture who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age and into the Middle Ages, at which point th ...

set up stable polities. Francia

Francia, also called the Kingdom of the Franks ( la, Regnum Francorum), Frankish Kingdom, Frankland or Frankish Empire ( la, Imperium Francorum), was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks dur ...

was centred in northern Gaul, and the first king of whom much is known is Childeric I

Childeric I (; french: Childéric; la, Childericus; reconstructed Frankish: ''*Hildirīk''; – 481 AD) was a Frankish leader in the northern part of imperial Roman Gaul and a member of the Merovingian dynasty, described as a king (Latin ''rex ...

(d. 481). Under Childeric's son Clovis I

Clovis ( la, Chlodovechus; reconstructed Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first king of the Franks to unite all of the Frankish tribes under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a single kin ...

(r. 509–511), the founder of the Merovingian dynasty

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

, the Frankish kingdom expanded and converted to Christianity.[James ''Europe's Barbarians'' pp. 79–81] Unlike other Germanic peoples, the Franks accepted Catholicism which facilitated their cooperation with the native Gallo-Roman

Gallo-Roman culture was a consequence of the Romanization of Gauls under the rule of the Roman Empire. It was characterized by the Gaulish adoption or adaptation of Roman culture, language, morals and way of life in a uniquely Gaulish context ...

aristocracy. Britons fleeing from – modern-day Great Britain – settled in what is now Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

.[

Other monarchies were established by the Visigoths in the ]Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

, the Suebi

The Suebi (or Suebians, also spelled Suevi, Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples originally from the Elbe river region in what is now Germany and the Czech Republic. In the early Roman era they included many peoples with their own names ...

in northwestern Iberia, and the Vandals in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

.[ The ]Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 and ...

settled in Pannonia

Pannonia (, ) was a province of the Roman Empire bounded on the north and east by the Danube, coterminous westward with Noricum and upper Italy, and southward with Dalmatia and upper Moesia. Pannonia was located in the territory that is now wes ...

, but the influx of the nomadic Avars from the Asian steppes to Central Europe forced them to move on to Northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative regions ...

in 568. Here they conquered the lands once held by the Ostrogoths from the Byzantines, and established a new kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

composed of town-based duchies.[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 196–208] By the end of the 6th century, the Avars conquered most Slavic, Turkic and Germanic tribes in the lowlands along the Lower and Middle Danube, and they were routinely able to force the Eastern emperors to pay tribute.[Curta ''Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages'' pp. 51–59] Around 670, another steppe people, the Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as nomad ...

settled at the Danube Delta

The Danube Delta ( ro, Delta Dunării, ; uk, Дельта Дунаю, Deľta Dunaju, ) is the second largest river delta in Europe, after the Volga Delta, and is the best preserved on the continent. The greater part of the Danube Delta lies in Ro ...

. In 681, they defeated

Defeated may refer to:

*Defeated (Breaking Benjamin song), "Defeated" (Breaking Benjamin song)

*Defeated (Anastacia song), "Defeated" (Anastacia song)

*"Defeated", a song by Snoop Dogg from the album ''Bible of Love''

*Defeated, Tennessee, an unin ...

a Byzantine imperial army, and established a new empire on the Lower Danube, subjugating the local Slavic tribes.[Curta ''Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages'' pp. 71–77]

During the invasions, some regions received a larger influx of new peoples than others. In Gaul for instance, the invaders settled much more extensively in the north-east than in the south-west. Slavs settled in Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

and the Balkan Peninsula. The settlement of peoples was accompanied by changes in languages. Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, the literary language of the Western Roman Empire, was gradually replaced by vernacular languages

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

which evolved from Latin, but were distinct from it, collectively known as Romance languages

The Romance languages, sometimes referred to as Latin languages or Neo-Latin languages, are the various modern languages that evolved from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic languages in the Indo-European language fam ...

. These changes from Latin to the new languages took many centuries. Greek remained the language of the Byzantine Empire, but the migrations of the Slavs expanded the area of Slavic languages

The Slavic languages, also known as the Slavonic languages, are Indo-European languages spoken primarily by the Slavic peoples and their descendants. They are thought to descend from a proto-language called Proto-Slavic, spoken during the Ear ...

in Eastern Europe.[Davies ''Europe'' pp. 235–238]

Byzantine survival

As Western Europe witnessed the formation of new kingdoms, the Eastern Roman Empire remained intact and experienced an economic revival that lasted into the early 7th century. There were fewer invasions of the eastern section of the empire; most occurred in the Balkans. Peace with the Sasanian Empire, the traditional enemy of Rome, lasted throughout most of the 5th century. The Eastern Empire was marked by closer relations between the political state and Christian Church, with doctrinal matters assuming an importance in Eastern politics that they did not have in Western Europe. Legal developments included the codification of

As Western Europe witnessed the formation of new kingdoms, the Eastern Roman Empire remained intact and experienced an economic revival that lasted into the early 7th century. There were fewer invasions of the eastern section of the empire; most occurred in the Balkans. Peace with the Sasanian Empire, the traditional enemy of Rome, lasted throughout most of the 5th century. The Eastern Empire was marked by closer relations between the political state and Christian Church, with doctrinal matters assuming an importance in Eastern politics that they did not have in Western Europe. Legal developments included the codification of Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor J ...

; the first effort—the ''Codex Theodosianus

The ''Codex Theodosianus'' (Eng. Theodosian Code) was a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Emperor Theodosius II and his co-emperor Valentinian III on 26 March 429 a ...

''—was completed in 438.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 81–83] Under Emperor Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

(r. 527–565), a more comprehensive compilation took place—the ''Corpus Juris Civilis

The ''Corpus Juris'' (or ''Iuris'') ''Civilis'' ("Body of Civil Law") is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. It is also sometimes referred ...

''.[Backman, ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'', pp. 130–131]

Justinian almost lost his throne during the Nika riots

The Nika riots ( el, Στάσις τοῦ Νίκα, translit=Stásis toû Níka), Nika revolt or Nika sedition took place against Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in Constantinople over the course of a week in 532 AD. They are often regarded as the ...

, a popular revolt of elementary force that destroyed half of Constantinople in 532. After crushing the revolt, he reinforced the autocratic elements of the imperial government and mobilized his troops against the heretic western realms. The general Belisarius

Belisarius (; el, Βελισάριος; The exact date of his birth is unknown. – 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under the emperor Justinian I. He was instrumental in the reconquest of much of the Mediterranean terri ...

(d. 565) conquered North Africa from the Vandals, and attacked the Ostrogoths, but the Italian campaign was interrupted due to an unexpected Sasanian invasion from the east. For the movement of troops from the Balkan provinces left the region virtually unprotected, the neighboring Slavic and Turkic tribes intensified their plundering raids across the Danube. Between 541 and 543, a deadly outbreak of plague decimated the empire's population, and the epidemic swept through the Mediterranean several times during the following decades. Justinian was to apply new methods to counterbalance its negative effects. He covered the lack of military personnel by developing an extensive system of border forts. To reduce fiscal deficit, he nationalized the silk industry and ceased to finance the maintenance of public roads. In a decade, he resumed expansionism, completing the conquest of the Ostrogothic kingdom, and seizing much of southern Spain from the Visigoths.[Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' pp. 150–156]

Justinian's reconquests and excessive building program have been criticised by historians for bringing his realm to the brink of bankruptcy, but many of the difficulties faced by Justinian's successors were probably due to other factors, including the epidemic. An additional problem to face the empire came as a result of the massive expansion of the Avars and their Slav allies. They conquered the Balkans and Greece with the exception of a few coastal cities before their assault on Constantinople was repulsed in 626.[Brown "Transformation of the Roman Mediterranean" ''Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe'' pp. 8–10] In the east, border defences collapsed during a new war with the Sasanian Empire and the Persians seized large chunks of the empire, including Egypt, Syria, and much of Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. A Persian army approached Constantinople to join the Avars and Slavs during the siege but a Byzantine fleet prevented them from crossing the Bosporus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern T ...

in 626. Two years later, Emperor Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was List of Byzantine emperors, Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the Exa ...

(r. 610–641) launched an unexpected counterattack against the heart of the Sassanian Empire bypassing the Persian army in the mountainous regions of Anatolia. He triumphed and the empire recovered all of its lost territories in the east in a new peace treaty.[Collins ''Early Medieval Europe'' pp. 140–143]

Western society

In Western Europe, some of the older Roman elite families died out while others became more involved with ecclesiastical than secular affairs. Values attached to Latin scholarship and education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Va ...

mostly disappeared, and while literacy remained important, it became a practical skill rather than a sign of elite status. In the 4th century, Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

(d. 420) dreamed that God rebuked him for spending more time reading Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

than the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

. By the 6th century, Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours (30 November 538 – 17 November 594 AD) was a Gallo-Roman historian and Bishop of Tours, which made him a leading prelate of the area that had been previously referred to as Gaul by the Romans. He was born Georgius Florenti ...

(d. 594) had a similar dream, but instead of being chastised for reading Cicero, he was chastised for learning shorthand

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing as compared to longhand, a more common method of writing a language. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography, from the Greek ''ste ...

.[Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' pp. 174–175] By the late 6th century, the principal means of religious instruction in the Church had become music and art rather than the book.[Brown ''World of Late Antiquity'' p. 181] Most intellectual efforts went towards imitating classical scholarship, but some original works were created, along with now-lost oral compositions. The writings of Sidonius Apollinaris

Gaius Sollius Modestus Apollinaris Sidonius, better known as Sidonius Apollinaris (5 November of an unknown year, 430 – 481/490 AD), was a poet, diplomat, and bishop. Sidonius is "the single most important surviving author from 5th-century Gaul ...

(d. 489), Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' w ...

(d. ), and Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

(d. ) were typical of the age.[Brown "Transformation of the Roman Mediterranean" ''Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe'' pp. 45–49]

Changes also took place among laymen, as aristocratic culture focused on great feasts held in halls rather than on literary pursuits. Clothing for the elites was richly embellished with jewels and gold. Lords and kings supported entourages of fighters who formed the backbone of the military forces. Family ties within the elites were important, as were the virtues of loyalty, courage, and honour. These ties led to the prevalence of the feud in aristocratic society, examples of which included those related by Gregory of Tours that took place in Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

Gaul. Most feuds seem to have ended quickly with the payment of some sort of compensation.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 189–193]

Women took part in aristocratic society mainly in their roles as wives and mothers of men, with the role of mother of a ruler being especially prominent in Merovingian Gaul. In Anglo-Saxon society the lack of many child rulers meant a lesser role for women as queen mothers, but this was compensated for by the increased role played by abbess

An abbess (Latin: ''abbatissa''), also known as a mother superior, is the female superior of a community of Catholic nuns in an abbey.

Description

In the Catholic Church (both the Latin Church and Eastern Catholic), Eastern Orthodox, Coptic ...

es of monasteries. In contrast, in medieval Italy women were always considered under the protection and control of a male relative.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 195–199] Women's influence on politics was particularly fragile, and early medieval authors tended to depict powerful women in a bad light. Examples include the Arian queen Goiswintha

Goiswintha or Goisuintha was Visigothic Queen consort of Hispania and Septimania. She was the wife of two Kings, Athanagild and Liuvigild. From her first marriage, she was the mother of two daughters — Brunhilda and Galswintha — who were marri ...

(d. 589), a vehement but unsuccessful opponent of the Visigoth's conversion to Catholicism, and the Frankish queen Brunhilda of Austrasia

Brunhilda (c. 543–613) was queen consort of Austrasia, part of Francia, by marriage to the Merovingian king Sigebert I of Austrasia, and regent for her son, grandson and great-grandson.

In her long and complicated career she ruled the eastern ...

(d. 613) who was torn to pieces by horses after her enemies captured her at the age of 70.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 116, 195–197] Women usually died at considerably younger age than men, primarily due to infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose is the prevention of reso ...

and complacations at childbirth. Infanticide was not an unusual practice in times of famine, and daughters fell victim to it more frequently than their brothers who could potentially do harder works. The disparity between the numbers of marriageable women and grown men led to the detailed regulation of legal institutions protecting women's interests, including the , or "morning gift", a compensation for the loss of virginity.[Backman, ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'', p. 120] Early medieval laws acknowledged a man's right to have long-term sexual relationships with women other than his wife, such as concubines

Concubinage is an interpersonal and sexual relationship between a man and a woman in which the couple does not want, or cannot enter into a full marriage. Concubinage and marriage are often regarded as similar but mutually exclusive.

Concubin ...

and those who were bound to him by a special contract known as , but women were expected to remain faithful to their life partners. Clerics censured sexual unions outside marriage, and monogamy

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time (serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., polyga ...

became also the norm of secular law in the 9th century.[Bitel, ''Women in Early Medieval Europe'', p. 180–182]

Peasant society is much less documented than the nobility. Most of the surviving information available to historians comes from

Peasant society is much less documented than the nobility. Most of the surviving information available to historians comes from archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

; few detailed written records documenting peasant life remain from before the 9th century. Most of the descriptions of the lower classes come from either law codes or writers from the upper classes.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' p. 204] Landholding

In real estate, a landed property or landed estate is a property that generates income for the owner (typically a member of the gentry) without the owner having to do the actual work of the estate.

In medieval Western Europe, there were two compet ...

patterns were not uniform; some areas had greatly fragmented landholding patterns, but in other areas large contiguous blocks of land were the norm. These differences allowed for a wide variety of peasant societies, some dominated by aristocratic landholders and others having a great deal of autonomy.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 205–210] Land settlement also varied greatly. Some peasants lived in large settlements that numbered as many as 700 inhabitants. Others lived in small groups of a few families and still others lived on isolated farms spread over the countryside. There were also areas where the pattern was a mix of two or more of those systems.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' pp. 211–212] Legislation made a clear distinction between free and unfree, but there was no sharp break between the legal status of the free peasant and the aristocrat, and it was possible for a free peasant's family to rise into the aristocracy over several generations through military service.[Wickham ''Inheritance of Rome'' p. 215] Demand for slaves was covered through warring and raids. Initially, the Franks' expansion and conflicts between the Anglo-Saxon realms supplied the slave market with prisoners of war and captives. After the Anglo-Saxons' conversion to Christianity, slave hunters mainly targeted the pagan Slav tribes—hence the English word "slave" from , the Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned ...

term for Slavs. Christian ethics brought about significant changes in the position of slaves in the 7th and 8th centuries. They were no more regarded as their lords' property, and their right to a decent treatment was enacted.[Backman, ''Worlds of Medieval Europe'', pp. 119–120]

Roman city life and culture changed greatly in the early Middle Ages. Although Italian cities remained inhabited, they contracted significantly in size. Rome, for instance, shrank from a population of hundreds of thousands to around 30,000 by the end of the 6th century. Roman temple

Ancient Roman temples were among the most important buildings in Roman culture, and some of the richest buildings in Roman architecture, though only a few survive in any sort of complete state. Today they remain "the most obvious symbol of Ro ...

s were converted into Christian churches

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym for ...

and city walls remained in use.[Brown "Transformation of the Roman Mediterranean" ''Oxford Illustrated History of Medieval Europe'' pp. 24–26] In Northern Europe, cities also shrank, while civic monuments and other public buildings were raided for building materials. The establishment of new kingdoms often meant some growth for the towns chosen as capitals.[Gies and Gies ''Life in a Medieval City'' pp. 3–4] The Jewish communities survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire in Spain, southern Gaul and Italy. The Visigothic kings made concentrated efforts to convert the Hispanic Jews

The history of the Jews in Latin America began with conversos who joined the Spanish and Portuguese expeditions to the continents. The Alhambra Decree of 1492 led to the mass conversion of Spain's Jews to Catholicism and the expulsion of those ...